- Department of Curriculum Studies and Studies in Applied Linguistics, Faculty of Education, Western University, London, ON, Canada

This study examines the purposes and methods of classroom-based assessment (CBA) used by English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in secondary schools in Jordan. The study data was collected through an online questionnaire that surveyed 54 participants and follow-up semi-structured interviews with three teachers. The questionnaire data were analyzed in SPSS using descriptive statistics, while the interviews were transcribed and coded for recurrent themes. The data showed that teachers use assessment to achieve various goals, including those related to students’ performance, instruction, and administration. The study also found that teachers employed a range of assessment methods of which teacher-made tests was the most common. Additionally, teachers’ choices of assessment methods were found to be influenced by factors such as the National Exam (Tawjihi), students’ proficiency level, as well as their own knowledge of assessment. These findings have implications for prompting awareness among EFL stakeholders in Jordan about the vital role of CBA and the necessity to improve teacher training and professional development programs in order to enhance teachers’ assessment knowledge and practices.

1. Introduction

Research in the areas of second language instruction in the Middle Eastern context has mainly focused on student or teacher perspectives on different aspects of language and pedagogy (see, for example, Alghazo, 2015; Zidan et al., 2018; Clymer et al., 2020; Alghazo et al., 2021). However, the study of classroom-based assessment (CBA) has not been given due attention in that context. Indeed, CBA has traditionally been a means of evaluating students’ learning and documenting their achievements. In the literature, assessment has been divided into two categories: summative assessment, which is conducted at the end of the learning process (i.e., end of instructional unit or end of a course), and formative assessment, which is implemented throughout the learning process (Brown and Abeywickrama, 2018). In recent years, there has been a greater emphasis on formative assessment (Irons and Elkington, 2021) which is intended to inform teachers’ decisions about how to proceed in order to achieve student learning goals (Black and Wiliam, 2009) and support students’ self-awareness, autonomy, and goal setting (Fox, 2014; Yan and Carless, 2022). This shift is in line with a global trend toward a more balanced approach to assessment that includes both summative and formative assessment (Cheng, 2011). This has led to a change in the role of teachers, from evaluators of students’ learning achievements to facilitators of learning (Black and Wiliam, 2009; Cheng and Fox, 2017).

In the literature, the available research on English as a Second Language (ESL) or English as a Foreign Language (EFL) assessment practices is considerably less extensive than the vast collection of studies on language testing practices (Cheng et al., 2008). In several ESL/EFL contexts, investigations looked into teachers’ assessment practices (e.g., Cheng et al., 2008; Troudi et al., 2009; Saefurrohman and Balinas, 2016; Wang, 2017). Nevertheless, this has not reached to numerous ESL/EFL contexts. For example, in the context of Jordan, there were only a few studies about EFL teachers’ classroom assessment practices—the types of questions used in designing English language tests (Omari, 2018), and implementation of some assessment types such as self-assessment (Baniabdelrahman, 2010) and portfolio-based assessment (Obeiah and Bataineh, 2016).

In the context of public secondary schools in Jordan, to the best of our knowledge, it appears that no study has yet explored EFL teachers’ assessment practices. Thus, this study aims to investigate EFL teachers’ classroom assessment practices, including the purposes and methods of CBA in the context of public secondary schools in Jordan. It also aims to identify the factors that influence teachers’ choices with regards to assessing students in the four language skills, building on the previous work of Swaie (2019). The questions driving this research were as follows:

1. For what purposes do EFL teachers use CBA?

2. What methods do EFL teachers use to assess students in reading, writing, listening, and speaking? What influences their choices of assessment?

1.1. Context of the study

In the Jordanian education system, once students finish their primary education (i.e., Grade 1 to 10), they can choose to pursue a two-year program in either academics or vocational training, which is known as the secondary stage and consists of Grades 11 and 12 (Al-Hassan, 2019). This program concludes with the General Secondary Education Certificate Examination, also known as Tawjihi. The Tawjihi is a crucial examination for students who wish to attend a university in Jordan as it determines the subjects they can study in post-secondary education. In addition, the examination holds great significance for individuals seeking employment in various public or private sectors in Jordan as it can be used as a criterion for selection in the hiring process. Due to its significance in both short-term and long-term career prospects, Tawjihi is considered a high-stakes examination.

The curriculum in Jordan includes a mandatory English subject as a foreign language for all public and private schools, from first grade to twelfth grade, with a range of four to six classes per week, each lasting 45 min (Alhabahba et al., 2016; Algazo, 2020). In addition, English is a commonly taught language in universities and colleges and is used as the medium of instruction for certain fields of study such as medicine and engineering (Tahaineh and Daana, 2013; Algazo, 2023). Despite the widespread teaching of English in Jordanian schools, universities, and colleges, Jordanian students are mostly weak in the English language and lack proficiency in English language skills (Alhabahba et al., 2016).

To become an English language teacher in the Jordanian Education system, the Ministry of Education requires a minimum of a Bachelor’s degree (i.e., BA) in English or English language and literature. However, many graduates of these programs lack training in teaching methodologies which compromises their readiness as teachers. To address this, the Ministry of Education has launched various programs such as the New Teacher Induction Course, a four-week training program for all new public-school teachers, and a nine-month program in partnership with a non-profit organization to better equip pre-service teachers with the knowledge and skills needed to teach professionally in public schools. However, these programs are general and intended for all teachers of all disciplines. There are no teacher training courses or workshops dedicated solely to English language teachers to prepare them before entering their teaching careers in schools. Moreover, there are no training courses dedicated to training English language teachers on how to evaluate their students’ performance in the subject.

1.2. Classroom-based assessment

In the literature of language teaching and learning, there has been recently more focus on CBA in both ESL and EFL contexts. CBA refers to the process in which teachers and/or learners evaluate the work of individual or groups of learners, and use the insights gained for teaching, learning, feedback, reporting, management, or socialization purposes (Hill and McNamara, 2012). This includes the procedures, techniques, and strategies that teachers use to evaluate students’ achievement at a specific point in time, known as Summative Assessment or Assessment of Learning (McMillan, 2015) and those used to improve teaching and learning throughout the learning process, known as Formative assessment or Assessment for Learning (Black and Wiliam, 2009).

1.3. Teachers’ assessment practices

During the assessment process, teachers frequently gather, interpret, and evaluate evidence of student learning, and then use the outcomes to make decisions and take action (Brown and Abeywickrama, 2018). These decisions may be influenced or constrained by several factors at different levels (Priestley et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2020). At the broader level, research on the EFL contexts found that high-stakes examinations create pressure on schools and teachers in a way that leads to plan instruction and assessment to enhance students’ achievements on such examinations (Gu, 2014; Fulmer et al., 2015; Tan and Deneen, 2015).

Furthermore, school policies can have a profound influence on classroom assessment practices. For example, Yan et al. (2021) found that EFL Chinese teachers did not fully implement formative assessment that supports students learning because school policy puts great emphasis on using tests and scores to assess students. At the classroom level, assessment decisions can depend on the purpose of assessments and students’ needs (Brookhart, 2004). Research has shown that teachers in EFL contexts such as China often use standardized tests as the essential method of assessment to train students for the College English Test. As an example, Cheng et al. (2008) found that standardized tests were commonly used for this purpose. Further research (e.g., Andrews et al., 2002; Cheng, 2004; Qi, 2005) has shown that teachers in Hong Kong and China usually use assessment formats similar to those used in external testing, particularly during the end of the term.

Another factor that may impact teachers’ decision-making of assessment is teachers’ experience and knowledge of assessment. Teachers’ assessment knowledge and practices can be varied according to the length of their teaching experience (Crusan et al., 2016). For example, Cheng et al. (2004, 2008) noted that ESL/EFL teachers with more experience and training in assessment were less reliant on published materials (e.g., published textbooks) when designing their assessments. On the other hand, teachers with less experience and limited knowledge about assessment tend to rely on traditional methods, such as tests and quizzes, and disregard alternative methods like self-and peer-assessment (Vogt and Tsagari, 2014). Moreover, teachers who have not received proper assessment training in their pre-service or ongoing training programs usually utilize summative methods such as paper-and-pencil tests more than formative or other alternative methods (Vogt and Tsagari, 2014). Other studies (e.g., Campbell and Collins, 2007; Lam, 2015; DeLuca and Johnson, 2017; Coombe et al., 2020) also found that pre-and in-service EFL teachers often lack the skills and knowledge required to carry out assessments effectively in their classes, whether such assessments are summative or formative.

Investigating teachers’ practices can assist in enhancing pre-service and professional development programs, providing teachers with the required knowledge and abilities to conduct classroom assessment efficiently (Weigle, 2007; Crusan, 2010; Malone, 2013; Koh et al., 2018). Therefore, in keeping with the rising interest in researching ESL/EFL teachers’ CBA practices and responding to the shortage of assessment studies in the context of Jordan, this study explored EFL teachers’ CBA practices in Jordanian secondary schools and relevant influences on their assessment decisions.

2. Methodology

The study adopted a two-stage mixed methods design (Creswell and Creswell, 2018) that includes questionnaires and interviews in order to investigate the research questions. First, a closed-ended online questionnaire was utilized to collect data on participants’ assessment practices. The results from this stage were then employed to develop the interview questions for the subsequent stage in order to gain a deeper understanding of the results.

2.1. Online questionnaire

The Qualtrics-designed online questionnaire was composed of three sections: (1) Demographic information (gender, age, educational qualifications, total years of teaching experience, grade(s) taught, and assessment knowledge), (2) Assessment purposes and their frequency of use on a scale of 1 (Never, 0%) to 5 (Always, 100%), and (3) Methods used to assess students’ language skills (i.e., reading, writing, listening & speaking) and their frequency of use on a scale of 1 (Never, 0%) to 5 (Always, 100%). These sections were adopted from Cheng et al. (2004) study with some modifications, such as the inclusion of the 5-point scale for frequency of assessment methods use.

2.2. Online interviews

All interviews were semi-structured and conducted via online audio calls recorded for later transcription and analysis, each lasting between 30 to 60 min. The interview questions were developed based on questionnaire results. The questions aimed to elicit further explanations for teachers’ responses (e.g., clarifying confusing, contradictory, and unusual responses) and their assessment practices (e.g., what types of method they frequently use and why they chose certain types over others).

2.3. Participants

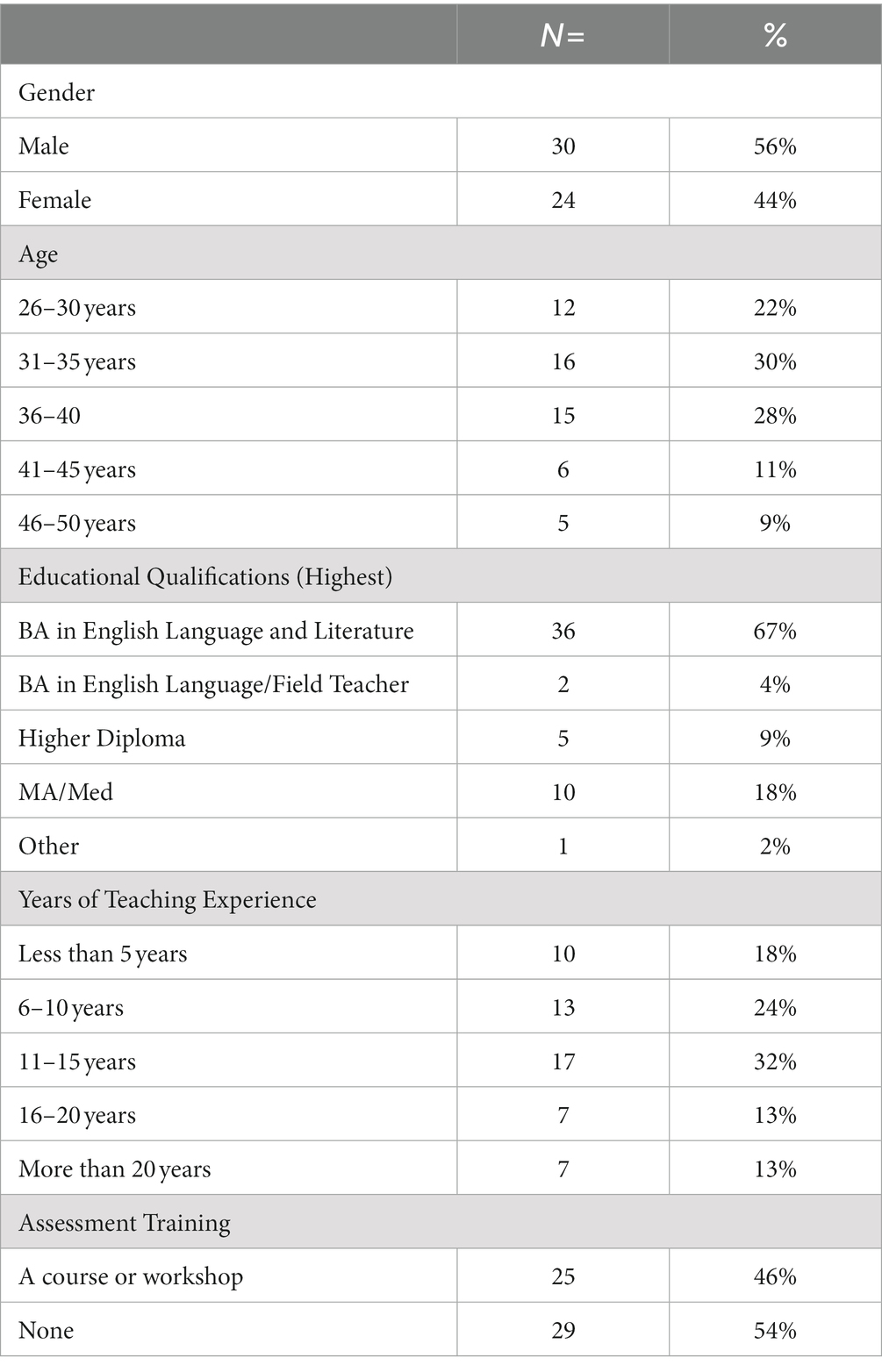

The participants were recruited online; a recruitment poster was shared on two Facebook groups for EFL teachers in Jordan. A total of 58 teachers from different public secondary schools across three regions in Jordan showed their interest to participate in completing the questionnaire, while three of them participated further in follow-up interviews. The demographic information of the participants is displayed in Tables 1, 2.

All questionnaire respondents hold a BA in English Language and Literature, which is the minimal qualification needed to be eligible to teach EFL in the schools of Jordan. In addition, 15 of the respondents, who constitute 28% of the study participants, hold an additional degree; Master’s degrees and/or diplomas. Most participants have at least 11 years of teaching experience. The average weekly teaching load of the participants is 14 classes, with an average of 30 students in each class.

The participants of the interview stage come from different public secondary schools across different areas in Jordan. All of them hold BA and MA degrees and their teaching experience ranges from 3 to 6 years. Only Teacher 2 received training on formative assessment via an online course whereas the other teachers did not receive any assessment training.

2.4. Data analysis

Questionnaire data was analyzed in SPSS (Version 25) using descriptive statistics to summarize data trends. Interviews were transcribed and coded for recurrent themes. The analysis of the interviews provided explanations for teachers’ frequent use of certain types of assessment methods and considerations that influence their assessment choices.

3. Results

The questionnaire and the follow-up interviews served as the foundation for the following study results. While the questionnaire data gives a broad picture of the participants’ thoughts, the in-depth interviews offer specific insights into the participants’ experiences and ideas.

3.1. Purposes of CBA use

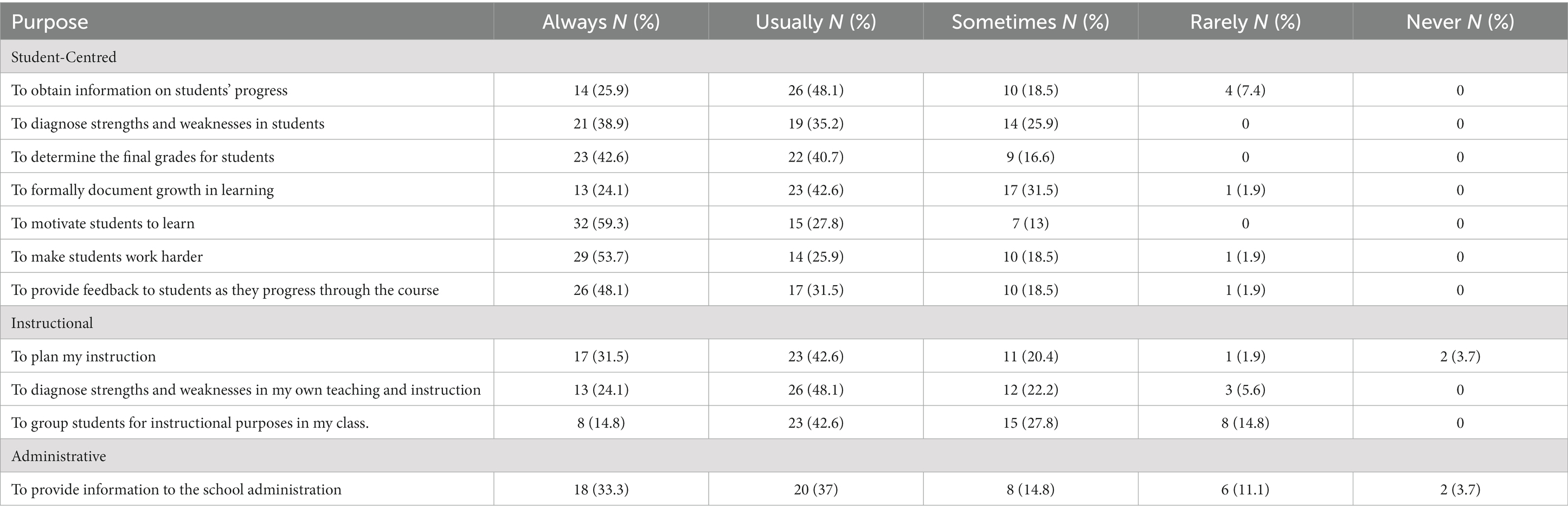

The questionnaire results show that teachers use classroom assessment for several purposes, grouped into three categories according to Cheng et al. (2004). These categories were: student-centered, instruction-related, and administration-related as shown in Table 3.

Among the three categories, the most frequently used purposes were student-centered. More than 80% of teachers reported that they always or usually use assessment to motivate students to learn (87%), determine final grades for students (83%), make students work harder and provide feedback to students as they progress through the course (80%).

With respect to instruction-related purposes, the most frequently reported instructional purpose, as indicated by “always and “usually” responses, was plan my instruction (74%), followed by diagnose strengths and weaknesses in my teaching and instruction (72%). The least frequently reported purpose was group students for instructional purposes in my class (57%).

With regards to administrative purposes, 70% of teachers reported that they most frequently use assessment to provide information to the school administration, yet 15% of teachers reported they rarely or never used assessment for this purpose.

The analysis of the interviews corroborated the results of the questionnaire. Teachers claimed they used assessment mainly for purposes related to their students. For example, Teacher 1 said, “the main goal of assessment is to assess the knowledge that students have got, at what level they are, and [to know] what their achievements in this course and if they achieved the goals that we wanted them to achieve.” In addition, Teacher 2 stated that assessment motivates students to learn; She said, “it [assessment] is not just about keeping records of their [the students’] achievements but also helping them and motivating them to improve and go forward.” Teachers emphasized that assessment as a tool for encouraging student growth and development in addition to recording student accomplishment.

Furthermore, all three teachers agreed that assessment can be utilized to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their teaching methods, leading to better instructional planning. For instance, Teacher 3 said “assessment can help teachers to improve their students’ learning as well as their own teaching methods.” Teacher 2 said, “Also, to check if there is any need to use other teaching strategies to get the outcomes of the course.” Moreover, Teacher 1 highlighted the use of assessment for instructional planning while discussing the implementation of diagnostic tests: “So I know where I should start with them [students]. After that, I should write a remedial plan for weak students and a developmental plan for good students.” According to the teachers, assessment can be used not only for evaluating their student progress, but also for evaluating and improving their own teaching methods and lesson planning.

The interviews also revealed another purpose for assessment which was not listed in the questionnaire, that is preparing students for the National Exam (Tawjihi). For instance, Teacher 1 stated that the main purpose of assessment in her perspective is “to see if they [students] are ready to pass the Tawjihi exam.” The teachers, in interviews, emphasized that Tawjihi is a primary goal of assessment, and teachers often use assessments to evaluate their students in a similar format to the Tawjihi exam in order to better prepare them for the exam.

3.2. Assessment methods

The study examined ways teachers used to assess their students’ English language skills in reading, writing, listening and speaking. The data collected through the questionnaire showed that teachers employ a range of methods to evaluate students’ proficiency in the four language skills. These methods were categorized into three groups based on Cheng et al. (2004) classification: teacher-made assessment methods, which are designed and administered by teachers, student-conducted assessment methods, which require student participation, and standardized testing.

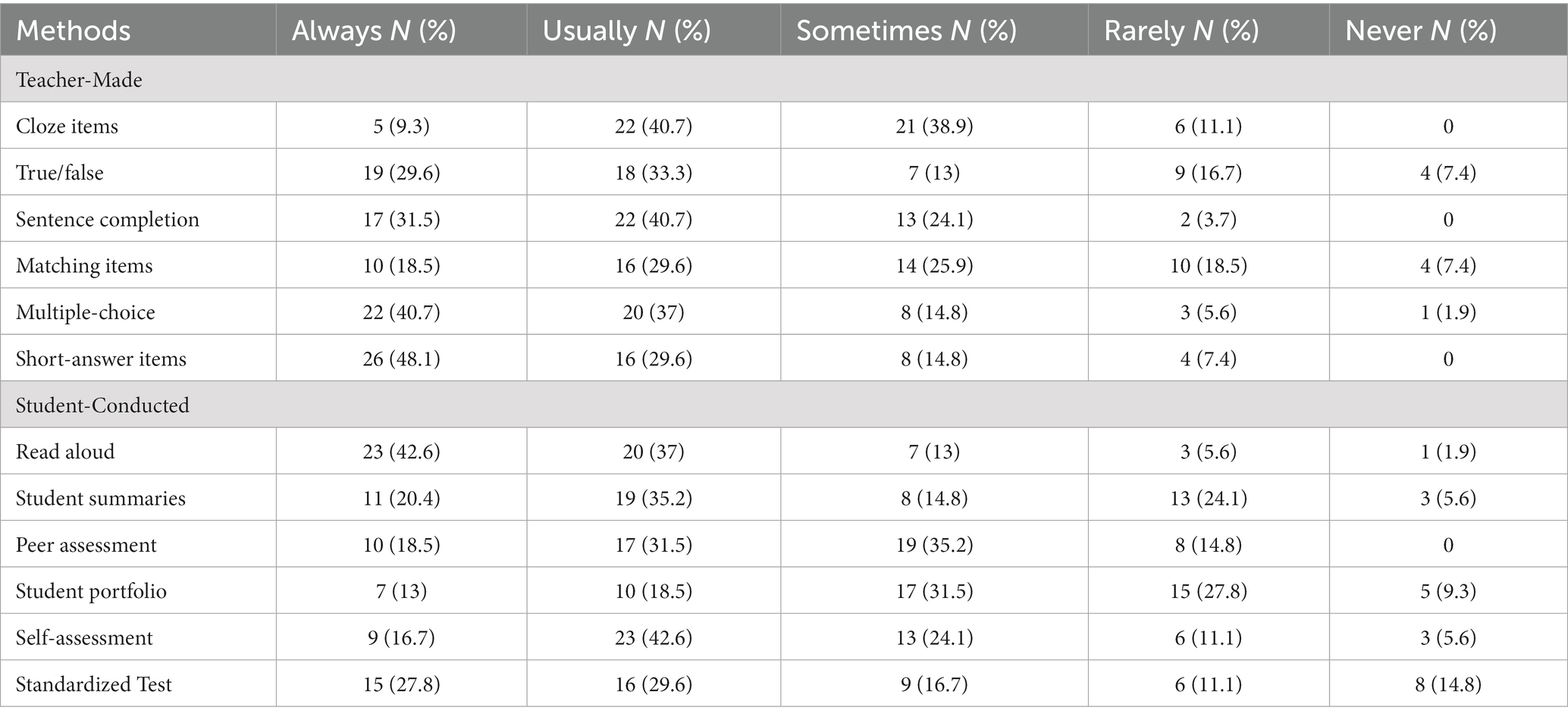

3.2.1. Reading assessment

The data of the questionnaire suggest that teachers use a range of strategies to evaluate abilities of students in reading, as seen in Table 4, with different frequencies across all three categories. The most frequently used method, as indicated by “always” and usually” reported by 80%, was read aloud of teachers while the least frequent method was student-portfolio, as only 32% reported using it frequently. Moreover, teacher-made assessment methods were used more frequently than student-conducted assessment methods. This is evident in the 78% of teachers who reported using multiple choice and short-answer items more frequently (i.e., always and usually) than other types of questions in reading tests.

The interviews data confirmed that reading aloud is commonly used by teachers to assess students in reading. For example, Teacher 2 said, “I let them read aloud to check their pronunciation and understanding.” In addition, teachers confirmed that multiple choice items and short-answer items are used frequently in the tests. For instance, Teacher 1 said “I use multiple choice items most of the time because they are very common in the National Exam [Tawjihi].” According to the teachers, reading aloud, multiple choice, and short-answer items are frequently used by teachers in order to evaluate students’ reading abilities. The former is used to verify students’ pronunciation and understanding, while the latter are preferred because they are more common in Tawjihi.

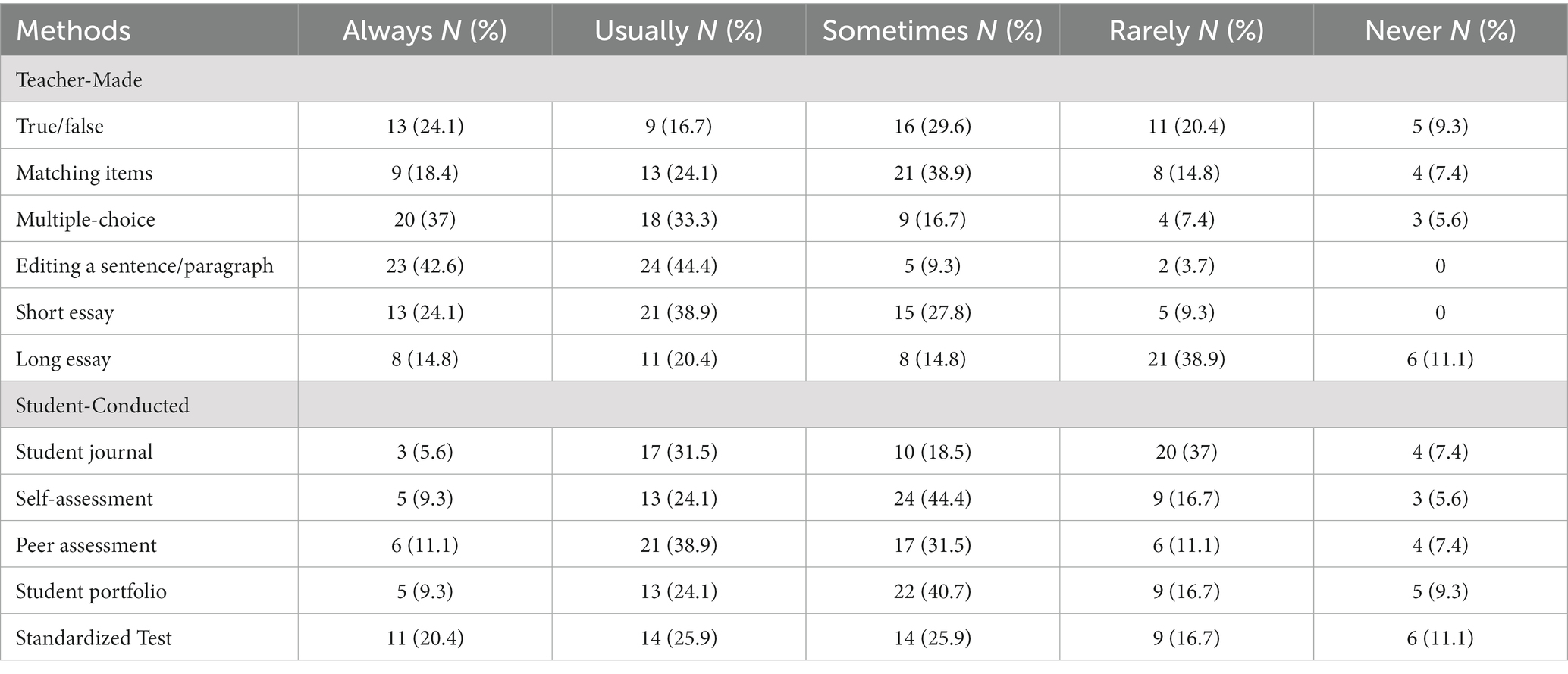

3.2.2. Writing assessment

The questionnaire results showed that teachers used a variety of assessments to evaluate their students’ writing abilities. The most used method for evaluating students’ writing was editing a sentence or paragraph, with 87% of teachers reported that they always or usually using it. On the other hand, the least frequently used methods were self-assessment and student portfolios, with only 33% of teachers reported that they use these methods frequently. Similar to reading assessment results, the data showed that teacher-made assessment methods were used more frequently than student-conducted assessment methods. Beside editing a sentence or a paragraph, the other commonly used methods were multiple-choice (70%) and short essay (63%) (Table 5).

The interview data supported these results. All three teachers reported that they rely on methods of editing a paragraph or writing an essay frequently to evaluate students’ writing. For instance, Teacher 3 said “I always include this question [editing a paragraph] in the test for Grade 11 and 12 because it is a common question in the National Exam.” Similarly, Teacher 1 said “I think for writing, the only method I use […] maybe not only me but also most English teachers, is giving the students a topic and ask them to write a short essay about it.” The participating teachers emphasized that they frequently employ editing a paragraph or drafting an essay to assess the abilities of their students in writing.

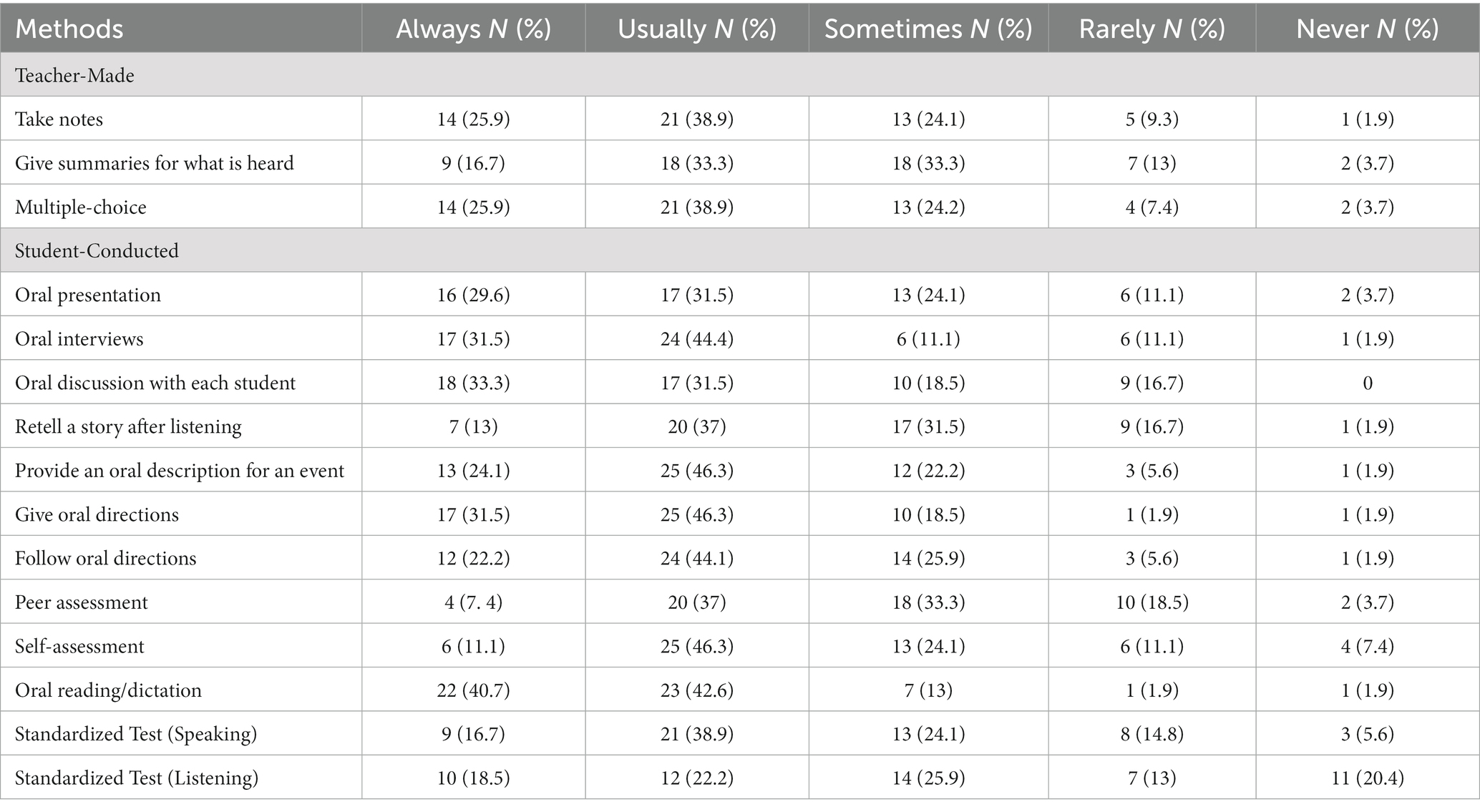

3.2.3. Listening and speaking assessment

The results of the questionnaire data, as shown in Table 6, demonstrate that oral/reading dictation (83%), giving oral directions (78%), and oral interviews (76%) were the most used methods, whereas standardized listening tests (41%) were the least used by teachers. Unlike reading and writing assessments, teacher-made assessment methods were employed less frequently than student-conducted assessment methods. This finding is not surprising, as evaluating listening and speaking typically requires more students’ involvement while using non-written material. With regards to tests, 65% of teachers responded that they always or usually use take notes and multiple-choice items in their listening and speaking tests.

The interviews data confirmed some of these findings and contradicted others. Teachers confirmed that they frequently use taking notes and multiple-choice items in their listening tests. For example, Teacher 3 said “I ask them to write some notes, main points, or anything they feel that it is important such as numbers, dates, and famous names.” However, none of the interviewees acknowledged utilizing oral reading or dictation to evaluate their students’ skills listening and/or speaking, despite the fact that the questionnaire indicated this was the method teachers used the most frequently.

The interviews data also revealed a different type of questions used by teachers that was not listed in the questionnaire, which is fill in-the-blank. For example, Teacher 2 said “For Grades 11 and 12 listening is more about fill in the blank.” The data collected from the interviews and the questionnaire confirm a de-prioritization of listening and speaking skills in Grades 11 and 12, and a mismatch, among questionnaire respondents and interviewees, in the methods used for assessing these skills.

3.3. Factors affecting teachers’ assessment choices

The interview data showed that teachers’ choices of assessment methods may be influenced by some factors including, the Tawjihi exam, proficiency level of students, and teachers’ assessment knowledge.

3.3.1. The Tawjihi exam

The data revealed that the Tawjihi exam has a significant impact on the way instruction is delivered, as well as the methods used for assessment. This is exemplified in the tendency of teachers to design tests similar to what students in Grade 12 will encounter on the Tawjihi exam. All the interviewees informed that they use assessment formats similar to the Tawjihi exam in order to prepare their students for the English Tawjihi exam. For instant, Teacher 1 said, “We usually follow the same format of the Tawjihi. We try to make the students familiar with the types of questions in the Tawjihi so they can achieve good marks.” Likewise, Teacher 3 stated that she consistently includes an editing a paragraph task, which is common on the Tawjihi exam, in her writing tests for both Grade 11 and 12 students. The influence of Tawjihi also extends to textbook usage, as teachers are restricted to using only the required textbook because the exam is based on the material provided in the textbook. For example, Teacher 3 said:

As a teacher […] you have to finish the material by the end of the semester, you cannot skip anything. We [teachers] feel that we are restricted to the curriculum and the textbook, and we cannot go beyond that because we will find many challenges from the school, parents, and students themselves.

The findings show that the Tawjihi exam has a significant impact on instructional and assessment methods. To help students prepare for the exam, teachers typically match their exams with the Tawjihi exam’s framework. Teachers are also feeling that they are constrained by the curriculum and required textbook as a result of the impact of Tawjihi exam.

3.3.2. Proficiency level of students

The data of interviews suggest that teachers consider the level of language proficiency of the students in developing assessment tasks or tests. Teacher 2, for example, contended that she typically adapts her instruction and selects assessment tools that are appropriate for her students’ level of proficiency. She said, “in writing classes…I just try to help my students by making it easier for them…I do this because my students are weak especially in writing.” The teachers emphasized that they take the students’ competency level into account while developing assessment activities.

3.3.3. Assessment knowledge

The interview data indicates that how teachers develop and implement their assessment methods can be related to their knowledge and training level on classroom assessment. The interviewees informed that even though they had completed the New Teacher Induction Course, they still lacked the necessary knowledge to conduct classroom assessments because the course had insufficient material on the topic. For example, Teacher 2 said:

I have never attended any course in assessment. It is just the short course I attended at the beginning of my teaching in public schools. There were topics on teaching English in general, how to manage the classroom and a little information about assessment.

According to the teachers in interviews, there are no programs available for teachers in order to equip them with the necessary knowledge and skills about designing and utilizing the assessment methods.

4. Discussion

The results based on the questionnaire and interviews data demonstrated that most Jordanian EFL teachers use assessment in their classes in order to accomplish several purposes, both formative (e.g., planning instruction) and summative (e.g., determining final grades). This suggests that teachers seem to be aware of the various purposes that can be used for assessing language in the classroom. This awareness may be attributed to their teaching experience and knowledge of assessment methods as more than half of teachers have at least 11 years of teaching experience and have attended courses or workshops on assessment. This supports previous research in the literature that found experienced and well-informed teachers on assessment tend to employ more assessment purposes than less experienced or less assessment-knowledgeable teachers (Cheng et al., 2004).

The study also found that teachers primarily use assessment for student-centered purposes, such as determining final grades, obtaining information on students’ progress, and motivating students to learn and work harder. While some of these purposes can support effective teaching (e.g., Obtain information on students’ progress), most teachers reported utilizing assessment to support student learning (e.g., Motivate students to learn). This indicates that many teachers perceive that assessment should be used primarily to evaluate students’ learning. Moreover, the data of questionnaire revealed a high percentage of positive responses to instructional-related purposes, indicating a trend in teachers’ responses. However, it was unforeseen to find some teachers responding “Rarely” or “Never” to these purposes, which may suggest an absence of formative assessment in their classroom practice especially that those are core formative purposes. In relation to employing assessment to get students ready for the Tawjihi exam, this was predictable because in contexts where students are required to take high-stakes tests, teachers often tend to focus their instruction to prepare their students for the test (Shohamy, 2006; Cheng, 2008).

Turning to the methods, the results showed that teachers primarily employed Teacher-made assessment methods to evaluate their students in reading, writing, listening and speaking. This was more common than using Student-conducted methods or Standardized tests, particularly in reading (e.g., short answer and multiple-choice items) and writing (e.g., editing a paragraph). This trend may be attributed to the effect of the Tawjihi exam and the necessary to get students ready for this high-stakes examination since these types of questions are frequently found in the Tawjihi format, as informed by the interviewees. This emphasize on the format of high-stakes examinations has also been observed in other EFL contexts (e.g., Andrews et al., 2002; Qi, 2004). This can also be attributed to the fact that students in Jordan seem to be exam-oriented (Alhabahba et al., 2016) which makes them more concerned about passing the exam than learning to acquire knowledge and develop their English skills. Another reason for utilizing tests more often than methods that require students’ participation in assessment (e.g., self and peer assessment) could be the low proficiency level of students which lead teachers to choose methods that suit their students’ limited proficiency. This may explain the frequent use of editing a sentence/paragraph and multiple-choice items to assess writing compared to other methods such as short and long essays. This is in line with the findings of Cheng et al. (2008) who noted that due to the low English competence of students, EFL teachers in China often used translation tasks in assessment.

With respect to listening and speaking assessment, the study’s results revealed a discrepancy between what participants responded in the questionnaire and what they reported in the interviews. The questionnaire data showed that teachers frequently used methods such as oral/reading dictation and oral interviews to assess students in listening and speaking. However, in the interviews, all participants stated that they hardly focus on listening and speaking in their instruction or assessment because these two skills are not evaluated in the Tawjihi exam. Whatever the case, it appears that what the teachers proposed in the interviews are more accurate than what they stated on the questionnaire because this practice of teaching-to-the-test has been noted in previous research on the impact of large-scale and high-stakes examination in ESL/EFL contexts, where teachers incline to focus only on teaching the skills and exam-relevant material. (Manjarrés, 2005; Azadi and Gholami, 2013). The discrepancy could be explained by the fact that many of questionnaire respondents probably teach classes other than Grades 11 and 12, so it is reasonable to assume that many of the inconsistent responses were made by confused respondents who teach classes other than Grades 11 and 12.

The study also revealed that peer assessment or self-assessment were among the methods that were less frequently used by teachers to assess students’ four skills (i.e., reading, writing, listening & speaking). This probably attributes that EFL teachers in Jordanian secondary schools are not fully aware of the importance of such assessment methods because of the lack of assessment knowledge and training. It is also possible that students are not willing to participate in assessing their selves or peers because they only care about their teachers ‘assessment or they may be unfamiliar of this type of assessment as teachers stated in the interviews. This suggests that Jordanian students appeared to be less involved in assessment process to the extent that enable them to take responsibility over their learning. In the literature, students’ involvement in self and peer assessment is key principles in assessment for learning or formative assessment which believed to have potential to enhance and better support students’ learning (Black and Wiliam, 1998; Stiggins, 2002).

Regarding the factors that influence teachers’ choices of assessment, the interview results showed that teachers tend to follow the format of the Tawjihi in their tests, indicating the strong influence of this high-stakes exam on their assessment practices. This is consistent with previous research on the impact of high-stakes tests, which found that teachers are more likely to align their tests with external assessment formats (Cheng, 2004; Qi, 2004). In addition, this influence extends to instruction as teachers focus more on material and skills tested in the exam and neglect other skills such as listening and speaking. This may be due to the pressure on teachers to adhere to external testing material and format, and a lack of concern from students for what is not included in the exam. This may reflect a testing culture among students, who prioritize good grades in the language course over actual language learning (Abdo and Breen, 2010).

In addition, the proficiency level of students in English and their individual learning needs can significantly impact the design of assessment tools used by teachers in the classroom. Because of students’ poor proficiency level, teachers admitted that they frequently select assessment methods that seem to be easier for students and avoid other methods. In the literature, it was found that students’ language proficiency appeared to take priority when teachers choose how to evaluate their students (Wang et al., 2020). This is probably related to the assumption of some teachers that assessment should be used in a manner that does not elicit negative emotions in students. This perspective was also noted in Chang (2005) which found that many teachers hold the belief that assessments should be implemented in a manner that promotes and supports students’ learning while avoiding the creation of negative emotions.

The study suggests that assessment knowledge and training can influence how teachers conduct assessment in their language classrooms. Most teachers, in this study, seemed to have insufficient assessment knowledge especially with regards to formative assessment’s purposes and methods. This probably signifies a shortage of assessment training in teacher education and professional development programs. This concurs with earlier research in EFL settings that discovered that teacher programs may not equip teachers with adequate knowledge and instruction to skillfully carry out assessments in their classrooms, as the majority of the teachers’ training programs tend to focus on curriculum and teaching strategies in general (Inbar-Lourie, 2008; Coombe et al., 2012).

5. Conclusion

This study explored the assessment practices of EFL teachers in secondary schools of Jordan. Results showed that teachers use range of methods for different purposes and at different frequencies in their classrooms. Factors such as the National Exam (Tawjihi) and students’ proficiency levels significantly influenced teachers’ choice of assessment methods. The study also found that the most used method was teacher-made tests that resembled the Tawjihi exam format, particularly in reading and writing. However, these tests may not accurately assess students’ language abilities because they do not evaluate all language skills, such as listening and speaking.

The findings of this study may contribute to increasing awareness among ESL/EFL teachers and other stakeholders, including educational policymakers, regarding the significant role of assessment in the language classroom. Moreover, this study highlights the lack of teacher education programs that adequately address the need for training and development in assessing students’ language skills. It emphasizes the necessity of professional development programs for both pre-service and in-service teachers to equip them with the necessary knowledge and skills to conduct assessments effectively.

On the other hand, the findings of the study were based on self-reported data in which what teachers report about themselves might not correspond with what they actually do in the classroom. Therefore, further research using classroom observation is recommended in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of teachers’ assessment practices in the context of secondary schools in Jordan.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found online via the following link: https://curve.carleton.ca/e61926cb-de7e-44a0-956b-6fd4729a41b5.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Carleton University Research Ethics Board-A (CUREB-A). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. MA contributed to the study design, provided feedback on the data analysis, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdo, I., and Breen, G. (2010). Teaching EFL to Jordanian students: new strategies for enhancing English acquisition in a distinct middle eastern student population. Creat. Educ. 1, 39–50. doi: 10.4236/ce.2010.11007

Algazo, M. (2020). Functions of L1 use in EFL classes: students’ observations. Int. J. Linguist. 12, 140–149. doi: 10.5296/ijl.v12i6.17859

Algazo, M. (2023). Functions of L1 use in the L2 classes: Jordanian EFL teachers’ perspectives. World J. Engl. Lang. 13, 1–8. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v13n1p1

Alghazo, S. M. (2015). The role of curriculum design and teaching materials in pronunciation learning. Res. Lang. 13, 316–333. doi: 10.1515/rela-2015-0028

Alghazo, S. M., Zidan, M. N., and Clymer, E. (2021). Forms of native-speakerism in the language learning practices of EFL students. Int. J. Interdiscip. Educ. Stud. 16, 57–77. doi: 10.18848/2327-011X/CGP/v16i01/57-77

Alhabahba, M. M., Pandian, A., and Mahfoodh, O. H. A. (2016). English language education in Jordan: some recent trends and challenges. Cogent Educ. 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1156809

Al-Hassan, S. (2019). “Education and parenting in Jordan” in School systems, parent behavior, and academic achievement. eds. E. Sorbring and J. E. Lansford (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 55–65.

Andrews, S., Fullilove, J., and Wong, Y. (2002). Targeting washback—a case-study. System 30, 207–223. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00005-2

Azadi, G., and Gholami, R. (2013). Feedback on washback of EFL tests on ELT in L2 classroom. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 3, 1335–1341. doi: 10.4304/tpls.3.8.1335-1341

Baniabdelrahman, A. A. (2010). The effect of the use of self-assessment on EFL students’ performance in reading comprehension in English. TESL-EJ: teaching English as a second or foreign. Language 14, 1–22.

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 21, 5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Brookhart, M. S. (2004). Classroom assessment: tensions and intersections in theory and practice. Teach. Coll. Rec. 106, 429–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00346.x

Brown, H. D., and Abeywickrama, P. (2018). Language assessment: principles and classroom practices. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Campbell, C., and Collins, V. L. (2007). Identifying essential topics in general and special education introductory assessment textbooks. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 26, 9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00084.x

Chang, C. W. (2005). Oral language assessment: Teachers' practices and beliefs in Taiwan collegiate EFL classrooms with special reference to nightingale university Doctoral dissertation, University of Exeter.

Cheng, L. (2004). “The washback effect of a public examination change on teachers’ perceptions toward their classroom teaching” in Washback in language testing: Research contexts and methods. eds. L. Cheng, Y. Watanabe, and A. Curtis (Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 147–170.

Cheng, L. (2008). “Washback, impact and consequences” in Encyclopedia of language and education: Language testing and assessment. eds. E. Shohamy and N. H. Hornberger, vol. 7. 2nd ed (Chester: Springer Science Business Media), 349–364.

Cheng, L. (2011). “Supporting student learning: assessment of learning and assessment for learning” in Classroom-based language assessment. eds. D. Tsagari and I. Csépes (Frankfurt: Peter Lang), 191–303.

Cheng, L., and Fox, J. D. (2017). Assessment in the language classroom: Teachers supporting student learning London, England: Palgrave.

Cheng, L., Rogers, T., and Hu, H. (2004). ESL/EFL instructors’ classroom assessment practices: purposes, methods and procedures. Lang. Test. 21, 360–389. doi: 10.1191/0265532204lt288oa

Cheng, L., Rogers, T., and Wang, X. (2008). Assessment purposes and procedures in ESL/EFL classrooms. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 9–32. doi: 10.1080/02602930601122555

Clymer, E., Alghazo, S. M., Naimi, T., and Zidan, M. N. (2020). CALL, native-speakerism/culturism, and neoliberalism. Interchange: a quarterly review of. Education 51, 209–237. doi: 10.1007/s10780-019-09379-9

Coombe, C., Troudi, S., and Al-Hamly, M. (2012). “Foreign and second language teacher assessment literacy: issues, challenges, and recommendations” in The Cambridge guide to second and foreign language assessment. eds. C. Coombe, P. Davidson, B. O’Sullivan, and S. Stoynoff (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press), 20–29.

Coombe, C., Vafadar, H., and Mohebbi, H. (2020). Language assessment literacy: what do we need to learn, unlearn, and relearn? Lang. Test. Asia 10, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40468-020-00101-6

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE.

Crusan, D. (2010). Assessment in the second language writing classroom. Ann Arbor, Michigan:University of Michigan Press.

Crusan, D., Plakans, L., and Gebril, A. (2016). Writing assessment literacy: surveying second language teachers’ knowledge, beliefs, and practices. Assess. Writ. 28, 43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2016.03.001

DeLuca, C., and Johnson, S. (2017). Developing assessment capable teachers in this age of accountability. Assess. Educ. 24, 121–126. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2017.1297010

Fox, J. (2014). Portfolio based language assessment (PBLA) in Canadian immigrant language training: have we got it wrong? Contact 40, 68–83.

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C., and Tan, K. H. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers’ assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Gu, P. Y. (2014). The unbearable lightness of the curriculum: what drives the assessment practices of a teacher of English as a foreign language in a Chinese secondary school? Assess. Educ. 21, 286–305. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.836076

Hill, K., and McNamara, T. (2012). Developing a comprehensive, empirically based research framework for classroom-based assessment. Lang. Test. 29, 395–420. doi: 10.1177/0265532211428317

Inbar-Lourie, O. (2008). Constructing a language assessment knowledge base: a focus on language assessment courses. Lang. Test. 25, 385–402. doi: 10.1177/0265532208090158

Irons, A., and Elkington, S. (2021). Enhancing learning through formative assessment and feedback. Milton Park, England: Routledge.

Koh, K., Burke, L. E. C., Luke, A., Gong, W., and Tan, C. (2018). Developing the assessment literacy of teachers in Chinese language classrooms: a focus on assessment task design. Lang. Teach. Res. 22, 264–288. doi: 10.1177/1362168816684366

Lam, R. (2015). Language assessment training in Hong Kong: implications for language assessment literacy. Lang. Test. 32, 169–197. doi: 10.1177/0265532214554321

Malone, M. E. (2013). The essentials of assessment literacy: contrasts between testers and users. Lang. Test. 30, 329–344. doi: 10.1177/0265532213480129

Manjarrés, N. B. (2005). Washback of the foreign language test of the state examinations in Colombia: a case study. Arizona Working Papers in SLAT, 12, 1–19.

McMillan, J. H. (2015). “Classroom assessment” in International encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. ed. J. D. Wright, vol. 3. 2nd ed (Oxford: Elsevier), 819–824.

Obeiah, S. F., and Bataineh, R. F. (2016). The effect of portfolio-based assessment on Jordanian EFL learners’ writing performance. Bellaterra J. Teach. Learn. Lang. Liter. 9, 32–46. doi: 10.5565/rev/jtl3.629

Omari, H. A. (2018). Analysis of the types of classroom questions which Jordanian English language teachers ask. Mod. Appl. Sci. 12, 1–12. doi: 10.5539/mas.v12n4p1

Priestley, M., Priestley, M. R., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. London, England: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Qi, L. (2004). “Has a high-stakes test produced the intended changes?” in Washback in language testing: Research contexts and methods. eds. L. Cheng, Y. Watanabe, and A. Curtis (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 171–190.

Qi, L. (2005). Stakeholders’ conflicting aims undermine the washback function of a high-stakes test. Lang. Test. 22, 142–173. doi: 10.1191/0265532205lt300oa

Saefurrohman, P. D., and Balinas, E. S. (2016). English teachers classroom assessment practices. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 5, 82–92. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v5i1.4526

Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Milton Park, England: Routledge.

Stiggins, R. J. (2002). Assessment crisis: the absence of assessment FOR learning. Phi Delta Kappan 83, 758–765. doi: 10.1177/003172170208301010

Swaie, M. T. A. (2019). An investigation of Jordanian English as a foreign language (EFL) Teachers' perceptions of and practices in classroom assessment. MA thesis, Ottawa, ON: Carleton University. Retrieved from https://curve.carleton.ca/e61926cb-de7e-44a0-956b-6fd4729a41b5

Tahaineh, Y., and Daana, H. (2013). Jordanian undergraduates’ motivations and attitudes towards learning English in EFL context. Int. Rev. Soc. Sci. Human. 4, 159–180.

Tan, K. H. K., and Deneen, C. C. (2015). Aligning and sustaining meritocracy, curriculum and assessment validity in Singapore. Assess. Matt. 8, 31–52. doi: 10.18296/am.0003

Troudi, S., Coombe, C., and Al-Hamly, M. (2009). EFL teachers' views of English language assessment in higher education in the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. TESOL Q. 43, 546–555. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00252.x

Vogt, K., and Tsagari, D. (2014). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers: findings of a European study. Lang. Assess. Q. 11, 374–402. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2014.960046

Wang, X. (2017). A Chinese EFL teacher's classroom assessment practices. Lang. Assess. Q. 14, 312–327. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2017.1393819

Wang, L., Lee, I., and Park, M. (2020). Chinese university EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices of classroom writing assessment. Stud. Educ. Eval. 66, 100890–100811. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100890

Weigle, S. C. (2007). Teaching writing teachers about assessment. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 16, 194–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.004

Yan, Z., and Carless, D. (2022). Self-assessment is about more than self: the enabling role of feedback literacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 1116–1128. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.2001431

Yan, Q., Zhang, L. J., and Cheng, X. (2021). Implementing classroom-based assessment for young EFL learners in the Chinese context: a case study. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 30, 541–552. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00602-9

Keywords: language assessment, EFL teachers’ practices, classroom-based assessment, classroom assessment methods, assessment purposes

Citation: Swaie M and Algazo M (2023) Assessment purposes and methods used by EFL teachers in secondary schools in Jordan. Front. Educ. 8:1192754. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1192754

Edited by:

Aldo Bazán-Ramírez, Universidad Nacional José María Arguedas, PeruReviewed by:

Mauricio Ortega González, Autonomous University of Baja California, MexicoNéstor Miguel Velarde Corrales, National Pedagogic University, Mexico

Copyright © 2023 Swaie and Algazo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Malak Swaie, bXN3YWllQHV3by5jYQ==

Malak Swaie

Malak Swaie Muath Algazo

Muath Algazo