- Business School Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

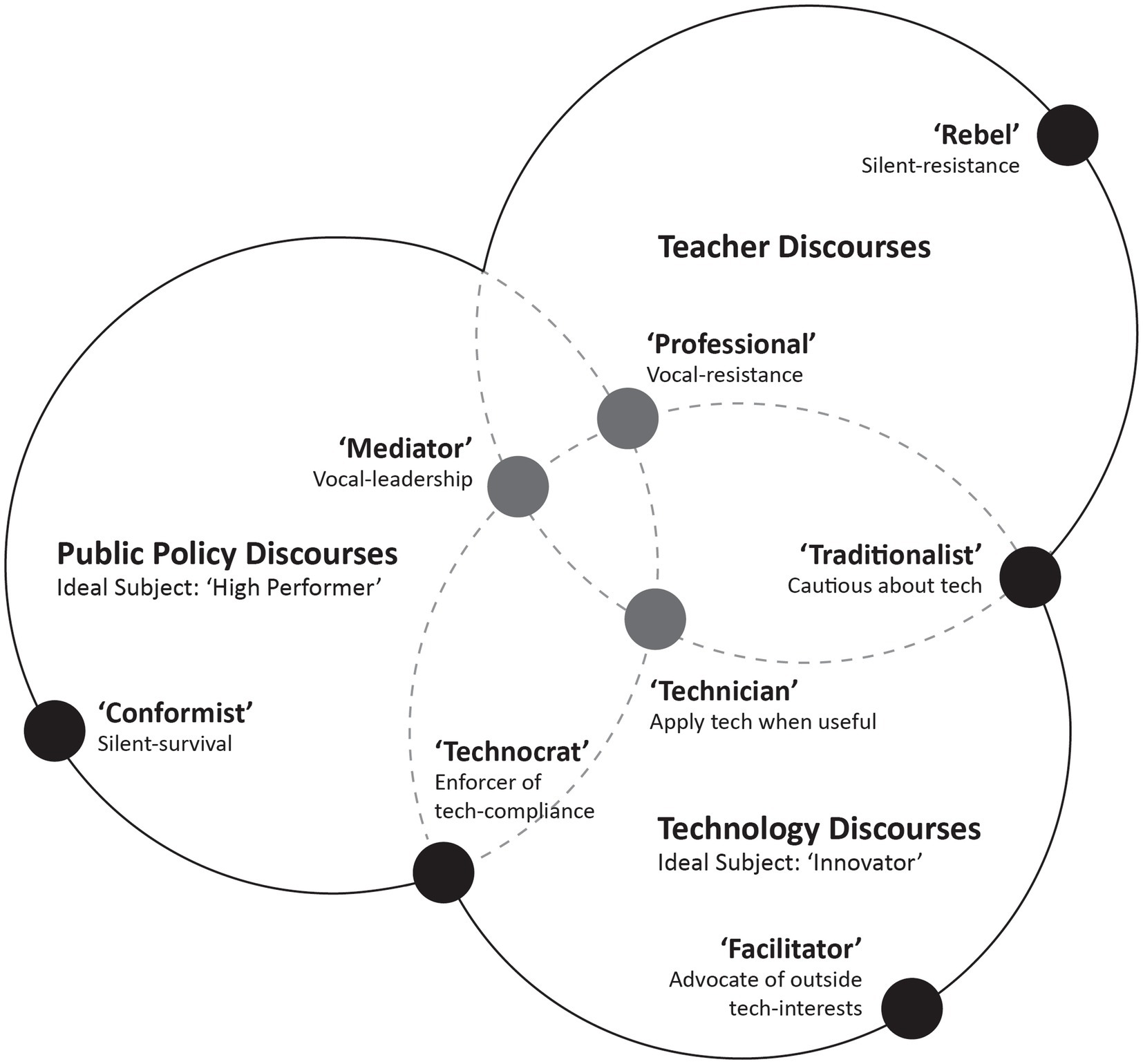

This Foucauldian case study examines how dominant discourses in education operate to subtly constitute teachers as normalized subjects by producing knowledge and inducing techniques of power. The retellings of high school teachers are examined to demonstrate how they reconcile their own personal experiences and professional ethics with the static ideal images projected by competing political discourses. It is found in the localized context of a single American high school that public policy, technology, and teacher discourses represent teachers in certain ways and compel them to self-regulate themselves such that they internalize and reify imposed norms. However, teachers resist and alter these discourses to produce other possibilities for the critical teacher subject positions they actually occupy. A model is proposed to illustrate how different representations of the teacher-subject emerge from the collision, distribution, and legitimatization of these discourses. This study brings into view the ways teachers powerfully question and resist the constraints placed upon their conduct and draw on their personal relationships with each other to constitute their own professional identities.

1. Introduction

This study advances the findings of Rose (2022) that uncovered how public policy, technology, and teacher discourses in education compete to shape the norms that conduct the conduct of teachers. Foucault’s concepts on techniques of power are used to characterize how the three aforementioned discourses discipline teachers to instill social cohesion and constitute them as normalized subjects.

Foucault (1980a) theorized that various forms of knowledge and power that manifest as modern technology individualize the subject on whom and through whom they operate (p. 98). Technology is situated and validated in a “field of power” that is located in the micropractices of individuals and “made up of the bits and pieces” of discourses that are “desperate sets of tools or methods” through which “limitations operate” on individuals (Foucault and Sheridan, 1977, p. 26). From this perspective, technology creates a disciplinary apparatus used to define and enforce normalcy through boundaries, rules, procedures, and sanctions. He defined the strategies and tools that reinforce normalcy and govern human beings within society as “techniques of power,” which is the human dressage or management that regulate and discipline the conduct of individuals to accomplish programmatic goals (Foucault and Kritzman, 1988a, p. 104).

The objectives of the present study are threefold. First, examine how discourses apply techniques of power to discipline high school teachers and compel them to self-regulate themselves such that they internalize and reify the norms that reinforce certain ideal subject positions. Second, describe how the high school teachers resist public policy and technology discourses either openly or by finding certain spaces left free in which to exercise agency and autonomy without directly challenging the rationality of the dominant discourse. Finally, show how the high school teachers modify discourses with their own knowledge to transform power relations and allow for alternative and unexpected constitutions of the teacher subject potions based on ideas of ethics, professionalism, and care for others.

The issue of resistance was central to Foucault’s views on power relations. He defines the process of discourse formation as “a space of multiple dissensions; a set of different oppositions” (Foucault and Sheridan, 1977, p. 155). In his view, resistance is not a reaction to powerlessness, but instead the assumption of power used in the interest of forming contradictory discourses (Foucault, 1980b). Opposing power involves “detaching the power of truth from the forms of hegemony, social, economic, and cultural, within which it operates at the present time” (Foucault, 1980a, p. 131). Rose (1999) expands on this idea: “government through freedom multiplies the points at which a citizens play their part in the processes that govern them. And, in doing so, it also multiplies the points at which citizens are able to refuse, contest, and challenge those demands placed upon them” (p. xxiii). In short, dominant discourses shape individuals, but individuals also push back to transform discourses.

Techniques of power induce compliance not through intimidation, but by instilling within teachers an acceptance of certain values and norms to remake teachers into compliant subjects so that they self-regulate their thoughts and actions and do not rebel. It is believed that technology functions in schools as a “perpetual eye” on teachers that imposes “a normalizing process, or a disciplining, through which they lose the opportunity, capacity, and will to deviate” (Gilliom, 2008, p. 130). From a Foucauldian perspective, teachers resist these disciplinary techniques of power through counter strategies that center on deconstructing dominant discourses and exposing the irrational politics of truth behind them. By exposing fictions in the dominant discourse, teachers disrupt them and develop counter-discourses based on an opposing set of values, morals, and principles that are no longer faithful to the regime of truth, but rather to teachers’ sense of professional ethics (Rose, 2022). It follows that teachers produce power through a network of relations, localized truths, and shared understandings that allow them to diverge from, confront, and disrupt dominant discourses. In this way, teacher discourses sanction resistance to governing and surveillance techniques that teachers associate with administrative practices aimed at controlling them and maintaining their compliance with imposed rules, norms, and measures of performance.

2. Materials and methods

The present study examines the told stories of a group of high school administrators and teachers to understand their interactions with public policy, technology, and teacher discourses. It paints a unique and in-depth picture of how these three discourses mediate the practices, values, and realities of those who are affected. Its purpose is to uncover how discourses produce subjectivity by deconstructing both the techniques of power that discipline various aspects of the teacher-self within the situated context of one high school in the southern region of the United States.

Creswell (2007) views case studies as a methodology that involves an “in-depth understanding of a single case or an issue using a case as a specific illustration” (p. 97). For the present study, the case study method was melded with Foucauldian discourse analysis to uncover the contextual conditions that are believed to be relevant to the phenomenon under study in the real-life context in which it occurs. The setting and case for this study is a small city high school (grades 9–12) in the southern region of the United State with about 1,300 students and 90 teachers and staff.

The multiple phases of this study’s theoretical framework blended Foucault’s analytical method with qualitative inquiry research techniques that emphasizes description, reflection, and interpretation. The hybrid approach employed was exploratory and descriptive. Stories from research participants about their work shed light on how participants saw their situation. As described in the previous study (Rose, 2022), data collection comprised interviews with fourteen of the high school’s administrators and teachers with diverse backgrounds, experience levels, and perspectives along with follow-up interviews, classroom observations and document collection. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. After each interview, changes were made to questions and the interview protocol. What was learned in early interviews influenced the protocol for succeeding interviews. Subsequent interviews focused on gaining more insight into what previous interviewees had shared.

For this study, Gore’s (1995) and Bandeen’s (2009) models are drawn on to serves as conceptual frameworks for defining primary constructs and interpreting data. Gore’s (1995) typology of Foucault’s major techniques of power serves as the conceptual framework for data analysis, and it is used to deductively identify themes for mapping power relations within the localized context of the case study. Gore’s model normalizes and operationalizes Foucault’s circulating techniques of power into a tidy typology of eight power tools: Surveillance, Distribution, Totalization, Individuation, Classification, Exclusion, Normalization, and Regulation. This applied framework makes Foucault’s ideas more relevant to narrative in education research and to the analysis of lived realities and experiences.

Bandeen’s (2009) qualitative study of elementary school teachers is used to conceptualize the different subject positions that are afforded teachers. Bandeen’s grounded model proposes four possible teacher subject positions that surface from the collision between public policy and teacher discourses: (1) “silent-survival” (non-adherence to teacher norms; adherence to policy norms), (2) “vocal-leadership” (adherence to teacher norms; adherence to policy norms), (3) “silent-resistant” (adherence to teacher norms; non-adherence to policy norms), and (4) “vocal-resistance” (non-adherence to teacher norms; non-adherence to policy norms) (p. 190). The present study advances Bandeen’s model by adding a third discourse, technology, as first presented in Rose (2022). This discourse represents its own unique set of truths and aims to define education from a different perspective that teachers generally oppose.

3. Results

3.1. Power tools of public policy discourses

According to Foucault and Sheridan (1977), discipline operates through distribution by separating the objects of power in space by classification or rank. Distribution by classification identifies individuals by their function and rank, and this separates individuals in relation to others. The “art of distribution” makes possible the “supervision of each individual and the simultaneous work of all,” which turns the space of the school into a “machine for supervising, hierarchizing, and rewarding” (Foucault and Sheridan, 1977, p. 145). Distribution tactics like grouping or connecting permit the effects of totalization, and distribution tactics such as isolation and enclosing operate to support the individualization of subjects.

The very architecture of a school operates to distribute teachers into organized and isolated spaces that allow for the easy observation and managing of their activities. For example, the layouts of the classrooms in Kim’s wing of the main building at the high school enables the inconspicuous observation of teachers by school administrators and their peers. All the classrooms are identically arranged, however, classrooms on opposite sides of the hall are the mirror image of each other. Regardless of which side of the hallway a classroom is located, the teacher’s smart board is always immediately adjacent to the entrance of the room, students’ desks are in the center facing the front of the classroom, and the teacher’s desk is opposite the entrance positioned up against the far wall. This has the effect of creating repetitiveness in the physical space in which teachers work with which that both teachers and students become very familiar.

Sitting at her desk, Kim can look out the open door of her classroom, through the open door of the classroom across the hall, to see another teacher sitting at her desk looking back. The arrangement of classrooms provides teachers with a view of each other, and it also enables passerby’s to easily peer into in every classroom with an open door to see what is going on. Anyone walking down the hall in a direction leaving the central courtyard, can see the students sitting at their desks and teachers giving their presentations. When they reach the end of the hall and turn around to walk back towards the courtyard, they can see what is displayed on the smart boards in every classroom.

As described above, the panoptic qualities of school’s architecture are evident in the arrangement of the classrooms. If an administrator or a department head wanted to assess whether Kim and her colleagues were all conducting the same learning activity as specified by their department’s common curriculum map, they could take an unassuming stroll down the hall to check. Teachers never know when someone of authority might use the architecture of the school to observe them unannounced. Sometimes, they may not even be aware that are being observed by someone outside the classroom. This makes the supervision of teachers invisible, which creates the sense that observation is constant – like living in fishbowl – and this leads to them to behaving as if they are being watched all the time.

In describing Foucault’s metaphor of a panopticon, Harland (1995) notes the effects of this power technique: “the exercise of continuous surveillance…means that those concerned also come to anticipate the response…to their actions past, present, and future and therefore come to discipline themselves” (p. 101). He also quotes Foucault and Sheridan’s (1977) observation that Distribution techniques “arrange things so that the surveillance is permanent in its effects even if it is discontinuous in action” (p. 201). Because teachers do not know when they are being observed, they adjust their behavior perpetually. As Kourtney says: “I have gotten used to it now, you feel like they are watching you all the time.”

In addition to distributing teachers in physical space to make them observable to authorities, Bandeen (2009) notes that distribution “isolates teachers from one another – teachers are essentially trapped as going to the bathroom or walking down the hall for food would mean that students are left unsupervised” (p. 109). Ella also comments that she does not have time to do anything else besides supervise her students even when she is present in her classroom: “It is not like you can turn them loose. Even when they are working on their own, I cannot sit here and look up fun activities or alternate ways of teaching because I am constantly having to monitor what they are doing.”

Teachers are classified by the classes they teach, and pursuant to these classifications they are assigned workloads and regimented schedules that limit their opportunities to interact with each other. For example, Kourtney says that her free time is taken up by extracurricular activities that teachers are expected to do: “Not only are you teaching, but you are also coaching something. You do not just come in here and teach, I do fifty-thousand other things that I do not get paid for.” And, Halle explains that because planning blocks are scattered throughout the day, teachers never have the opportunity to talk: “Everybody’s planning block is different. You may be teaching algebra and never see the other algebra teachers.”

Resulting from their classification and rank, teachers are isolated from each other. Leah confirms the severe isolation that can occur: “I have been very isolated here. I do not need validation from others, and I do not mind eating lunch by myself, but just some days I would like to speak to someone over the age of 14.” Luke also describes how his rank among all teachers as belonging to a specific department isolates his group from the rest of the school: “We are very isolated on this hall. I do not know anyone else besides who is on this hall.” Kim reiterates how the distribution in teachers in the space of their individual classrooms produces an overall sense of separation: “We are all really in our classrooms all year. I can count on one hand how many times we are all in one place talking about something during a year.”

The isolating effects of distribution techniques characterize the physical or contextual ways in which a network of common standards, performative systems and quantitative measures trap teachers within the four walls of their classrooms and automates their work. Distribution is imposed through rigid time schedules, pacing guides, curriculum maps and other prescriptive procedures produced by these systems. Teachers are always playing catch-up with the strenuous and stressful expectations imposed by time schedules and their students, which leaves them no time to intermingle and form relationships. For example, Kourtney characterizes the demands placed on her by students: “The kids are demanding, and they think you should answer them immediately and you do not have anything else going on in your life.” Their overwhelming schedules operates in the favor of public policy discourses because it forces teachers make use of the ‘shortcuts’ to instruction that are readily available. Ella gives an example:

Most of the time we are teaching what we have at our fingertips because we do not have time to pull in other things. We teach what the book is, which is sad, but when you have to spend so much time on other things, then you are just going off the textbook even though I know I am teaching other people’s beliefs about how it should be taught and what should be taught.

The distribution of teachers in time compels them to follow public policy and give up their power to performative systems. It erases what they would normally do to personalize their instruction and replaces it with predetermined pedagogy that as Ella says above represents “other people’s beliefs” and not the way they would choose to teach if they had adequate time to prepare.

Isolated from seeing what others are doing, teachers are left feeling fully responsible for their students’ outcomes and become highly committed to improving their scores, which reinforces the power of accountability systems. Leah is an example of a teacher who is very much concerned about demonstrating her performance, as she says: “I am trying to do my job, trying not to complain, and not to make waves because I like my job. I want to keep it.” She describes her first year as “sink or swim” with “professional deadlines” that were “very difficult to meet.” Even though she says her first year of teaching was “horrible” and her first evaluation was a “nightmare,” she believes she is “seeing improvement from last year in terms of teaching and management.” She is determined to make herself into a high performer.

Teachers like Leah are more susceptible to rationales of policy discourse. They willingly check their own scores to see their distribution relative to other teachers in their department, school and nation who are also measured by the same common assessment technology. The data makes teachers responsible for their assigned rank and for taking steps to improve themselves within the confines of their classification (classroom) without actually knowing if how they teach is any different from their peers due to their isolation. The data regulates what teachers can do and thus what they can become – their subjectivity – without the need of physical boundaries.

Production and quantitative measure produce data that distributes teachers by rank based on criteria favored by public policy. Teachers are ranked against all other teachers based on their ‘quality’ as represented by the statistics that are attributed to their work. In the same way that the data may represent the learning difficulties of individual students, administrators use the data to pinpoint trends or markers that signify ‘low’ performing teachers and then determine what they need to do to improve, which may include redistributing them in some way to subject them to other disciplining techniques. Novice teachers are paired with veteran mentors on their first day on the job and Mary reveals that sometimes struggling teachers are relocated near high performing teachers with the intent of connecting with a new role model.

Conversely, teachers who are ranked as high performers by the data are held up as ‘ideal’ models of compliance with policy’s expectations, and for this reason they may also be redistributed in relation to others. Halle, an administrator, uses the test scores to determine which teachers “you want explaining to the other teachers what they did.” Sometimes, the “better” teachers (often veteran with seniority) get the more advanced AP classes with “easy going” high performing kids and the “worse” teachers (often the newest and youngest) are relegated to teaching the entry-level classes with a more “taxing” general population of students, thus reifying their rank within the school socially, geographically, and hierarchically. For example, the high school administrators privileged the flipped classroom model when they commended the success of Noah’s use of the approach. Noah says that his modeling of best practices and achieving improved test scores was awarded when he was “given honors classes” to teach.

At the high school, distribution circulates teachers “in a network of relations” (Foucault and Sheridan, 1977, p. 146). It categorizes teachers by the classes they teach and ranks them within their classification relative to others (p. 145). According to their category and rank, teachers are isolated in the geographic ‘space’ within the school and by rigid time schedules that burden them with demanding assignments and responsibilities. These systems and associated accountability technology isolate and trap teachers in their classrooms throughout the workday. Performance statistics are also used to separate high performing compliant teachers from low performing noncompliant teachers, which can lead to further refinements of their physical distribution and subjects the other disciplinary techniques of power like surveillance that produce self-regulating teacher-subjects.

The distribution techniques discussed above arrange teachers in space and time to enable their observation, supervision, and examination. In Gore’s (1995) research, surveillance in schools is defined as “supervising, closely observing, watching, threatening to watch or expecting to be watched” (p. 169). Under the ‘norms’ of policy discourses, teachers are supervised to determine if they are behaving in ways that reflect performative models. As Bandeen (2009) notes: “surveillance elicits a performance to enact a semblance of compliance” with accountability goals (p. 105). Watching is closely linked to judging, correcting and praising teachers’ conduct during which “teacher bodies become aligned with intuitional purposes” (Bandeen, 2009, p. 105).

At the high school, teachers are subject to both scheduled and unannounced classroom observations by administrators that are either formal evaluative visits lasting the entire span of a class or are brief 5- to 15 min check-in calls called “walkthroughs.” Kim summarizes the observation schedule: “Your first year, they visit twice per semester – one time announced and one time unannounced. Your second and third year, they come twice a year. Once you are tenured, they come once every other year.” Leah, a new teacher, discloses how many times she was observed over her first year: “Out of 180 days and having the kids 90 min a day, I have been observed twice for a full class and once for 15 min at the beginning of a class.” John confirms that administrators will stay “bell-to-bell” during an official observation and that he undergoes extra observations from outside district-level administrators due to the nature of the type of class he teaches. Leah also mentions that as a new teacher she is subject to additional “peer observations” from her mentor and department head.

Based on the comments above, it appears that how much and how often a teacher is directly observed is contingent on their classification and rank and on how an individual administrator decides to apply surveillance tools. During an observation, administrators are looking for visible evidence that teachers are complying with the rules and expectations of the institution. Jane agrees that through classroom observations: “The administration knows who is doing what they are supposed to and who is not.” Kim believes she knows what administrators want to see when they visit her class:

I have my agenda on the board every day. I have my state standards posted. All those things are stuff you have to do as a teacher. When the administrators come do walkthroughs; this is what they are looking for. They are looking to see that you have your word wall, that you are doing the vocab, and if you have a plan and you’re following the standards and stuff like that. That is the accountability part of it.

Luke describes an observation as a “walkthrough where they come into the classroom, sits there, and takes notes for my evaluation.” He continues by noting the administrators are watching for certain signifiers that represent performance standards: “Administrators like to see some sort of bell ringers. They are looking for certain specific things – basically did they see ‘x’, ‘y’, and ‘z’ or did they not see ‘x’, ‘y’, or ‘z’ – like did the teacher use essential questions.” Kourtney adds some of the other criteria that administers assess during an observation:

They have this form they fill out and they are looking for you to have your common standards, integrate your technology, literacy standards, and you are differentiating your instruction for the kids that need it. They are just basically checking off a list that you are doing everything you need to. When I know I have an announced observation, then I will plan. If you have an announced observation and you want do not do well on it – that is when you want to put on your best show.

As Kim aptly points out above, through direct observations, administrators are gathering evidence about whether teachers are complying with public policy. And, through their knowledge of the criteria of surveillance, teachers can counter the scrutiny of school administrators and others by displaying behaviors that give the appearance of at least minimal conformity – what Kourtney refers to as a ‘show’ of professionalism. During observations, teachers behave as if they are being studied. In Kourtney’s earlier comment, she surmises that if a teacher understands the criteria, they can pass the examination by putting on a “show.” Rachel also compares her routine during an observation to a performance: “For the announced, what you do in a class does take planning and you need it to put on a dog-and-pony show.” Noah reveals that he thinks the essential questions are ridiculous, so he has developed an alternative solution: “To make an essential question, what I do is just put a question mark at the end of the objective. The way I game the system is to write it on the board. It will make them checkmark the box when they come in with that walkthrough form.” John describes in detail how he adjusts his lecture format when an administrator is watching:

I will pull up the pacing guide and I will say to the class: “Okay, today class we are going to cover this…” Next, I will pull my screen up and say: “In the course syllabus this will be standard number 5.” An administrator sitting there will see that and I will state it, and I also have it up visually so they can see it. Also, if you look up on my board, right there, are my essential questions.

What administrators see during an observation, even an unannounced observation, reflects what a teacher has planned ahead of time to visibly display as evidence of his or her compliance. Surveillance tools compel teachers to prepare a script for every class that they can pull out and “lay on administrators” to produce the appearance of meeting standards. On inspection, teachers must appear to administrators to have transformed themselves to become more like the ideal image of what a teacher is presumed to be like as measured by a series of checkboxes on a form. The checkboxes or criteria represent certain irrefutable values and principles privileged by public policy.

The procedures of standardize curriculum combine with surveillance techniques to create a technological apparatus of systematic, continuous, and pervasive normalization, which eliminates the stress of getting caught doing anything ‘wrong’ because teachers are nearly always doing what is ‘right’. Some teachers appear to be at least partially educated to a ‘regime of truth’ and normalized such as they have become agents of their own subjectification under public policy discourses. For example, after a classroom observation, a teacher is given a copy of the official observation form that shows which criteria he or she has met of failed to meet.

Mary, an administrator, explains what the checkboxes on the form represent: “If you have a lot of checkmarks then you are doing a lot of the things they are looking for.” The observation systematically reduces teaching to a set of checkboxes that represent only what can been seen by an outside observer and allows for individualization and totalization of teachers based on predetermined, yet continuously shifting criteria defined by public policy discourses and based on overly simplified behaviorist notions of the human condition. With the surveillance tool, teachers are individually inspected or diagnosed as missing certain absolute qualities of performance and they are ranked or categorized relative to all teachers based on the total number of checkmarks they receive. Kourtney takes issue with the ‘short form’ surveillance tool when nothing is checked, and the form is returned to her blank and without any explanation:

They will come through the room and the way they come in is very authoritative – no smile, no nothing, like they are in charge. After the walkthrough, they will put a blank form in the box, and it is a slap in the face. I think it is done on purpose because it is like they are saying: “I did not see anything that I think is worth of checking.” It is perceived as a bad thing, and it hurts your feelings. You start second guessing yourself and having evil thoughts. You get mad and go run your mouth to someone else about it. It is a strange thing to do. Why come in if you cannot write something down to give feedback?

For Foucault, surveillance strategies were more about influencing an individual’s psychology rather than trying to directly control what they do or make decisions for a person. Surveillance “does not liberate man of his own being, it compels him to face the task of producing himself” (Foucault, 1984, p. 42). In Kourtney’s comment above, the blank observation form caused her to “second guess” herself and have “evil thoughts.” It was a “slap in a face” to how she sees herself, which triggers her to appeal for more explicit “feedback” so that she can know what she is doing wrong. The effect of the blank form compels Kourtney to privately self-examine her own identity.

Through Surveillance tools, administrators at the high school continuously confront teachers with imbued impartial ‘truths’ about themselves to compel them to confess their faults and self-correct their conduct. Halle says that administrators at the high school never tell teachers exactly what to do. Instead, the evaluation of teachers at the high school resembles a kind of counseling session. Mary, an administrator, describes the ritual of the debriefing session from an administrator’s viewpoint:

We meet with the teachers one-on-one during which their observations are read to them about what they did. Then, we have a conversation about of what is happening and how can they improve.

Mary sees her role as kind of helpful coach who aids teachers in their career. During the confessional debriefing session that Mary describes above, teachers are compelled to validate the ‘truth’ rendered by the observation and take responsibility for correcting their mistakes or deficits by speaking to how they are going to change themselves. Surveillance takes on the form of self-inspection or self-analysis. Foucault believed that “self-examination is tied to powerful systems of external control: sciences and pseudosciences, religious and moral doctrines” that underscore public discourses and are supported by a “cultural desire to know the truth about oneself,” which “prompts the telling of truth; in confession after confession to oneself and to others, this mise en discourse has placed the individual in a network of relations of power with those who claim to be able to extract the truth of these confessions through their possession of the keys to interpretation” (Dreyfus and Rabinow, 1984, p. 174). The effect of an examination is not to oppress or silence teachers, but rather it is to create a connection or a relationship between school administrators and teachers – to make them visible and to define them in certain ways as individuals so that they can be talked about in an objective fashion, and they readily talk about the ‘truth’ of themselves in terms of their performance, professionalism, and pursuit of a career in education.

The ultimate example of confessional ‘truth’ telling comes at the end of school year when a teacher ‘sits-down’ with the principal for about 15 min to go over his or her official evaluation documents in typical bureaucratic form. Kim gives her take on the meeting:

They judged us on if we are meeting set of teacher standards like ethics or our repertoire. There is a list of things that they check ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on how you are doing these things and we get a copy. Then we talk about with the principal and hear if he feels we can improve on anything. We set goals at the beginning of the year and then another at the end of the year.

Based on Kim’s comment above, a teacher’s final yearly appraisal focuses on objectives in which the expertise of the ultimate authority in the school is used to counsel teachers to help maximize their productivity and avoid their early exit from the field. The evaluation is based on a participatory activity of mutually constructing a set of goals that a teacher will use to remake his or herself into a ‘better’ individual. By becoming complicit in their surveillance, teachers are at the same time disciplined and liberated – by accepting responsibility for changing themselves, they become their own supervisors and deflect the gaze of the authority. Leah recalls how she had a “tough time” during her first-year evaluation:

It was horrible. The principal did not come right and tell me I suck as a teacher, but he did say that there is a lot of work to be done and these are the two main areas I would focus on next year. He basically told me: “We are not going to fire you and the only way we will fire you is if you just refuse to do what we are asking you to do.”

Like a doctor kindly sharing the good news with his seriously ill patient that he has found a cure, the principal informs Leah that she still has a chance at a life as a teacher and she will overcome her challenges. Leah responds with a renewed determination to prove her worth, and she takes comfort in knowing administers are available to “nurture” her through the process of becoming a professional teacher. Leah has agreed to work under constant self-surveillance, reinforcing what Foucault and Sheridan (1977) referred to as a circular relation between ‘truth’ of the need for performance that defines what is ‘right’ and the power of disciplining practice through self-regulation: “Knowledge, once used to regulate the conduct of others, entails constraint, regulation and the disciplining of practice. Thus, there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time, power relations” (p. 27).

In a neoliberal paradigm of organizational management, individuals are free, but they must be self-critical and self-regulate and they require leadership, objectives, values and programs to develop their skills. In discussing the “technologies of the self” that individuals use to transform their selves, Foucault (1988b) described these practices of self-development as: “…permitting individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being” (p. 18). The practice of ‘instructional audits’ at the high school is another such tool in which administrators help teachers into a new way of being. Halle describes the audit process: “Every few weeks we sit down with all the teachers. We have a printout of their grade book, so if one teachers class average is a 61 and their test score is a 79 and they all teach the same subject, we want to know what is happening, why are we having that.” Leah verifies Halle’s characterization of the audit process:

We use a curriculum map, which are our standards, and we write down what activities we use to teach those standards and the dates we teach those standards. We have turn them in at the beginning of the semester. They are supposed to be audits we are supposed to have with the administration and guidance about at-risk students, people who are failing and to make sure we are still on par with the curriculum map we turned.

Both Halle and Leah describe the audit process as kind of accountability in which teachers are measured by statistics and they must explain themselves. In this sense, audits appear to be another top-down form of surveillance like classrooms observations, but from Halle’s point of view, teachers should be self-disciplined so that administrators do not need to step in to correct problems. She believes that when teachers take responsibility for managing themselves according to the expectations and goals of the institution, they are liberated from her supervision. Kourtney confirms that she feels free if she stays within the limits set for her: “I have complete freedom as long as I am meeting the standards, I have to turn in my lesson plans every week – they are checked by two different people and the principal. So, they know what I am doing.”

In the modern school where teachers are ‘free’ subjects, surveillance manifests as the management practices of coaching, guiding, advising, training, and collaborating. Together, these disciplinary techniques “serve as an intermediary between” administrators and teachers; “…linking them together, extending them, and above all…it assures an infinitesimal distribution of the powers relations” (Foucault, 1984, p. 153). The official classroom observation procedure is a pretext for a sit-down conversation or counseling session with teachers. Surveillance culminates in teachers self-regulating their own behavior to achieve collective education goals that are continuously reiterated by public policy discourses as statistics that report on common standards, learning outcomes, and key performance indicators.

3.2. High performer and conformist teacher-subject positions

The previous section identifies the techniques of power applied by public policy discourses to regulate what governmentality ascribes as the right mode of work and restrict the space in which teachers can operate. Statistics perpetually sort, rank, and classify teachers to exert pressure on them to self-discipline themselves. It was shown how distribution techniques facilitate the direct surveillance of teachers through unannounced walk-throughs, classroom observations, instructional audits and other forms of overt and covert data collection. Teachers were then confronted with data produced by surveillance during debriefing sessions with an individual presented as a friendly coach, counselor, advisor, or authority figure. During these sessions teachers are gently compelled to confess their faults and accept responsibility for self-regulating themselves into acceptable modes of thinking, speaking, and behaving.

Management of an institution like a school is a “calculated or rational activity… that seeks to shape conduct by working through [the] desires, aspirations, interests and beliefs [of individuals], for definite but shifting ends” (Dean, 1999, p. 11). From the public policy perspective, the ‘ends’ are preparing students with cutting-edge skills to be successful in the workforce and to meet wider economic interests. The ‘means’ are management practices based on performative models forged in the private sector that focus on common standards, outcome measures, and performative schemes. These common standards attempt to regulate what teachers can teach (curricula) and how they teach (pedagogy) (Rose, 2022). What is shown through the analysis of the teacher retellings is a romanticized narrative that denotes an ideal subject position, which is aligned with public policy discourses I call the ‘high achiever’ subject; someone that does not just adopt public policy reforms; he or she defends public policy goals and takes the initiative to see them accomplished without the need to be pressured into it by school administrators.

The high achiever subject is someone who looks to outcome statistics for validation of a job well done and thinks competition among teachers is productive; is self-critical, strives for excellence and continuously looks for ways to add value to themselves; prioritizes teaching from prearranged curricula over their own personal teaching style; dutifully documents their own work to make their activities visible to administrators and parents to ensure ‘fairness’ and transparency; and has a boundless positive attitude about and the will to try new teaching practices, technology and the latest trends. The high achiever is absorbed by public policy discourses and has no issue with limiting teacher freedom for the sake of improving outcomes.

The discursive statements of the high school teachers who have assumed the high achiever subject position reinforce the positive rationales that compose public policy discourses. As the title implies, the ideal subject is someone who sees himself or herself as an agent, supporter or follower of progress – his or her primary mission is to contribute to a successful school however it is defined. A high achiever is someone who needs to succeed and wants the recognition as a ‘top-performing teacher’. Typically, teachers who assume this subject position are new to their jobs and are thus vulnerable. They are concerned about being seen favorably by administrators and producing positive measures of their performance. Or, they are veteran teachers who are working towards graduate degrees in Educational Leadership and intend to eventually advance to administrative positions, and are thus modeling a managerial attitude.

The high achiever subject is a static and essential archetype that is legitimized by public policy discourses but is rarely fully grasped by teachers because it is counter to teacher discourses. Public policy discourses construct an ideal subject position that is mainly an impractical representation of a perfect teacher rather than an authentic account of a possible teacher subject. As such, the representation is an idealized subject that is in turn used in discourses as a porotype for what they should be, when teachers are faced with critical reviews of their conduct. Teachers are confronted with this improbable ideal, but what actually emerges are disrupted subject positions. Bandeen (2009) terms one of these alternative possibilities as ‘silent-survival’, and the analysis of the retellings of the high school teachers in the present study confirms that this reframing of the compliant teacher subject is more true-to-life. I rename this subject position as the ‘conformist’ teacher subject. Conformists believe that voicing their concerns is futile. The conformist adjusts to the demands of public policy discourses by succumbing – someone who drifts with the tide.

The conformist subject position is indicated by a “willingness to be a ‘team player’ for the support and endorsement of new policy” and “avoiding any discourses associated with negativity” (Bandeen, 2009, p. 115). Teachers may complain amongst themselves, but they show self-restraint and as Kim says, “they will just do it for the most part.” Teachers operating in conformist mode will not vocalize their opposition to policy reforms – they want to stay, as Kourtney says, “under the radar” and “not stand out.” Teachers become disillusioned by a recurring cycle of policy changes, and as a result disengage and do the minimum of what is expected in order to keep their jobs (Rose, 2022). The conformist subject is someone who grudgingly aligns themselves with new policy goals and has learned to “cope with policy discourses through silence” (Bandeen, 2009, p. 116). The ideal model for teacher compliance projected by public policy discourses contrast with a real one that emerges. The high achiever teacher is a vocal advocate for public policy reform, whereas the conformist subject is a begrudging follower.

3.3. Power tools of technology discourses

In Gore’s (1995) typology of Foucault’s major techniques of power, she defines individualization as: “Giving individual character to oneself or another” (p. 178). In contrast, totalization is the “specification of collectivities [and] giving collective character” (Gore, 1995, p. 179). Teachers are assigned individual character as belonging to certain classifications of groups based on how they measure up to collective or prescriptive ideal of what a teacher should be.

The totalizing effects to technology discourses can be seen in teachers’ individual narratives. For example, David, an administrator, says: “Students are digital natives compared to 20 years ago when I started teaching.” In his observation, he is applying collective character to students based on a principle spread by wider technology discourses. This illustrates how some teachers have internalized the knowledge or ‘truths’ that support technology discourses as a result of totalizing tactics – totalizing knowledge which they also apply to themselves and other teachers, not just students.

Some aspects of what it means to be a good or bad teacher are derived from wider technology discourses and are enacted through the relationships that teachers have with others in the context of their work. Administrators are compelled to measure teachers based on certain mandated technology competency standards, and they also totalize and individualize teachers based on technology discourses. For example, Mary, an administrator, attempts to totalize teachers by saying that “most teachers” do not use the technology that is freely available to them. Next, she individualizes teachers by attributing certain traits to this “non-user” group such as they may be reluctant to use or uncomfortable with technology:

I find that teachers do not use a lot of technology in the classroom, which is kind of surprising because they have a lot. I do not know if it is because they have taught for so long without technology that they choose not to use it because they feel like their teaching is good without it or if they are not comfortable with how to use the technology. I almost never ever see kids using technology in the classroom.

In her interview, Mary praises Noah as demonstrating the ideal way to use innovative technology to which all teachers should aspire. Noah’s belief in the value of standardized curricula and student-centered learning is supported by the aforementioned “net-generation” social imperative. In the following quote from Noah, he uses the rhetoric of technology discourses to, like Mary, paint a totalizing and individualizing image of other teachers by applying a hypothesis for why they are not matching his example:

I think people will have to let go of the traditional view of education and move toward what is best for students if that means not having as much control and not doing the same PowerPoint for another 5 or 10 years to have all the attention on them. We have to get away from that because the generation has changed and therefore culture has changed. If you are not teaching with culturally appropriate methods, then you are not serving so to speak.

In Noah’s comments above, he refers to the problem of doing the same things for “five or ten years” and Mary says, “they have taught for so long without technology that they choose not to.” These comments imply that they think age or experience is a factor correlated with technology competence. Later, Noah reveals how he believes his young age and the young age of one of his colleagues is a determining factor of their mutual success: “We’re both pretty young and pretty forward thinking.” Similarly, Kim believes that being young helps and she portrays one of senior teachers as being a barrier to fully implementing a new digital curriculum in her department:

Until now everyone has done their own thing, and this is a new concept of meeting together and discussing how you are going to teach together. But, he does not sit down with us. He may think he does not have anyone to meet with or collaborate with because he is the only one who teachers his class.

However, she says this issue is about to resolve itself: “He is retiring, so he is moving out, and we will have a younger faculty in the department, especially now with him retiring.”

As revealed above, the practice of measuring teachers according to ‘objective’ levels of technology competence, enthusiasm and use, facilitates both totalizing and individualizing power techniques. In this process the conduct and character of teachers is normed against an exceptional local group of technology leaders in their school, official technology standards for teachers and schools, and the common rhetorical points of view supporting technology discourses in the public realm.

The image of the ideal technology-astute teacher is inscribed in the official texts of state’s policy in the form of technology competency standards. Teachers are required to demonstrate how they participate in “ongoing, intensive, high-quality professional development that addresses the integration of 21st Century technologies into the curriculum and instruction to create new learning environments” and how they “achieve acceptable performance on standards- based performance profiles of technology user skills” (State Department of Education, 2015, p. 79). Schools measure teachers by their amount of involvement in professional development on technology topics, level of technology competency, positive attitudes towards technology, and use of technology in the classroom. Sometimes, this combination of criteria is referred to as technology self-efficacy, which is the idea that teachers believe in and take responsibility for their technology capabilities – actively seeking out professional development opportunities to improve their technology skills and then choosing to dutifully demonstrate their technology abilities in the classroom.

The all too familiar language that labels teachers as ‘techno-natives’ or ‘techno-immigrants’ is common rhetorical chorus in technology discourse (Prensky, 2001), but the connotations they carry is a source of agonism among teachers. Teachers who do not willingly hand over their classes to technology are seen as not being savvy enough to keep up with the future. Linked to the assumptions about performance is that older teachers are to blame for resisting the radicalization of education through technology.

Individualizing teachers by relating their age to their level of technology competence seems to have had an impact on the more experienced teachers in the localized context of the high school. Susan’s story is sort of the reverse of Noah, Rachel, John and other members on techno cutting edge. In their normalized view, she represents the typical “old” teacher that is holding education back. In introducing herself to me, Susan says that she has been teaching for 40 years and “if you ask any of the students here, they will tell you immediately that I am the old one who will not let them use a computer.” Susan describes herself as “very old fashioned,” which “has a place” in her class because she believes that students must learn how to do things “by themselves because that is the way I know they will know.” She is aware that she has been isolated by individualizing power tactics because of her differing views and conduct, but does not seem too concerned:

I realize I am in the minority with this view, but I want my students to know the subject. That is my basic goal. They can confirm with all the wonderful technology tools that they have available now. That is fine with me, but they must know the subject. You miss the whole point when you do not see the patterns and see how things work together, and if you are just typing everything into a computer, then you will never see that.

The stories provided above reveal how the power tools of totalization and individualization subject teachers to the knowledge and ‘ideals’ of technology discourses – tactics that compare and characterize all teachers as not being techno-savvy relative to a minority of young hot shots who are. Bandeen (2009) believes that “through Foucauldian power tools of totalization and individuation, teachers learn that by acting in certain ways they will either be recognized (calcified) or be erased (excluded) through the reassignments of value” (p. 112). Under the current regime of truth supported by technology discourses, a subgroup of the high school teachers is recognized as representing progress, most other teachers are engaging in the process of recasting themselves according to shifting technology and performance expectations, and small number of teachers who are labeled as ‘oldies’ are being pushed to retire, excluded, marginalized, and slowly erased.

3.4. Innovator and technician teacher-subject positions

For Foucault, discourses privilege or marginalize particular beliefs, values or actions by referencing the value of imbued ‘truths’ as a body of knowledge (Dreyfus and Rabinow, 1984, p. 187). Technology discourses establish the knowledge of subjects within their situated context. This knowledge is internalized by individuals and becomes a part of their identity. The aim of the previous section was to demonstrate how teachers have assumed different aspects of what technology discourses present as the ideal subject that I call the ‘innovator’ teacher subject.

Through the retellings of the high school teachers, it was revealed how technology discourses operate to characterize the innovator teacher by circulating the credos that present a picture of the ideal teacher. This subject position is presented as someone who is convinced that technology is the key to advancing education and solving society’s ills; feels responsible for teaching about technology in their class to spread technology literacy; willingly maintains their own technology competence by seeking out professional development opportunities; freely transforms their pedagogical practices to conform with technology-driven modes of learning, sees their role as that of a technology-enabled coach that takes a backseat to student self-directed learning; and is distinguished by their cutting-edge use of an online learning management systems (Rose, 2022). Ultimately, an innovator teacher is someone who readily relinquishes their power to technology-driven learning environments – he or she steps out of the way and lets technology take over for the good of students.

The snapshot of the ideal subject defined above is sketched within the limits set by technology discourses. This narrative embodies the imputed possibilities of technology is accepted without much criticism and questioning from teachers. Possibly, this verifies that the techniques and practices of technology discourses that are describe in the previous section are very productive at regulating and normalizing the high school teachers. The school is purposefully constructing a positive school culture around technology. Teachers are enmeshed in an environment of cutting-edge technology that they are expected to leverage to enhance instruction. The high school employs an instructional technology coordinator to manage technology initiatives and coach teachers on how to integrate technology into the classroom. It has changed the curriculum to emphasize technology skills and employs four business-tech teachers. Finally, the high school’s teachers understand that the qualities of the innovator teacher are encoded into official public policy texts that show up on their evaluation forms at the end of every school year.

It is also described in the previous section how teachers are totalized and individualized based on what technology discourses construct as what it means to be normal. Teachers are measured against official technology competency standards and are observed for behavioral evidence of a positive attitude towards technology. Those teachers who do not measure up to the standards are diagnosed for their individual faults and are pressured to change themselves through coaching, training, and exclusion. The example of a select group of techno-savvy youngsters is held up for teachers to admire as a way to make the promises of technology discourses appear genuine in the local context. It is through these totalizing and individualizing tactics that the high school teachers come to conduct themselves and ultimately transforms themselves into the innovator teacher subject.

The snapshot of the innovator teacher represents how one possible subject position has coalesced and become available to teachers, but it is not the only option teachers have. Other counter-narratives can represent teachers in different ways. A few younger teachers from the digital generation are ecstatic about the self-directed learning possibilities of technology, but for most teachers at the high school, the notion of giving up their authority over the teaching process to a computer is a prospect that they are reluctant to accept. The language teachers use to describe technology is generally passive or conditional as well as positive. Their applied view of technology as neutral necessitates a detached position where technology itself is not as important as how it is used – the technology changes from year-to-year but teaching practices and class content are irreplaceable (Rose, 2022). From this perspective, technology tools are useful to some teachers because they make instruction more engaging, interactive, and entertaining, but they are not revolutionary.

The above depiction of the way teachers align themselves with technology discourses represents an alternative subject position that I call the ‘technician’ teacher subject. This subject is someone who is more practical and less animated about the possibilities of technology. The technician attempts to fit technology into their work, not rearrange their work around technology. They also believe that technology should empower relationships and interactions among teachers and students, not replace them with automated computer-mediated learning.

In the process of governing themselves, teachers choose to reinforce or reform power relations. Foucault and Blasius (1993) explains that “governing people is not a way to force people to do what the governor wants; it is always a versatile equilibrium, with complementarity and conflicts between techniques…through which the subject is constructed or modified by himself” (p. 203). Teachers are not entirely produced by technology discourses – they have other experiences and influences of competing rationalities defined by other discourses to reflect on. The reality of individual subjects is contingent upon complex social relationships that play a part in influencing whether a teacher accepts some of the demands of the ideal innovator teacher subject position.

3.5. Power tools of teacher discourses

In mapping teacher discourses, it is not the aim of this article to validate the goals of teacher discourses as being more ‘right’ than the rationales produced by public policy or technology discourses. Teacher discourses are not merely reactive to public policy discourses – they work to condition teachers through complex relations to certain group norms that are equally regulating and normalizing, but in different ways and for different ends. Bandeen (2009) theorizes that teacher discourses apply classification and exclusion techniques of power within their social relations (p. 80). She posits that “as teachers create groups, they determine who is respected while also excluding others to create shifting patterns of informal memberships” (Bandeen, 2009, p. 80).

Gore (1995) defines classification as “differentiating groups or individuals from one another, classifying them, classifying oneself” (p. 174). Classification is the way teachers individualize and totalize others and themselves according to the social group to which they belong. In teacher discourses, group membership is indicated by loyalty, bonds, and empathy that create a sense of solidarity. Groups normalize teachers into the ‘better’ ways of doing things from the perspective of teacher discourses. Sometimes groups can be cliquish or elitist, meaning that they exclude and divide teachers. Gore (1995) explains that exclusion is sort of the “reverse side” of normalization – it is “a technique for tracing the limits that will define difference, defining boundaries, setting zones” that label some behaviors as ‘wrong’ and construct some individuals as ‘others’ (p. 173).

Many the high school teachers understand their group memberships as an inherent aspect of their jobs. For example, Kim hypothesizes: “Initially, if you like each other as people, just like normal – it is just natural that we all get together to talk about school and our classes and things.” David makes s similar observation: “People meet and get together simply because of shared values.” Kourtney reiterates that “teachers will have a group of people they will naturally gravitate to,” and she expounds further: “I am going to hang out with people who are more like me because I would not want to say something to someone else because you do not want to hear what they have to say.” Kourtney feels that she can speak freely around her like-minded friends when she has something negative to say. Her social group allows her to take a resistant position on issues, to be pessimistic and to defend herself. In other words, her social group supports her activism.

Kim adds to her earlier comment that it is through groups that “things will get spread around.” Echoing Kim’s experience, other high school teachers also note that groups facilitate sharing knowledge. For example, Kourtney comments on the sense of comradery that exists: “The collaboration that we have is amazing – you could go to anyone here and they will help you. We are all really good friends.” Jane gives a specific example of how teachers support each other: “All the time, I will type an assignment out, the I will share it with my colleagues and ask them to tell me how I can tweak it.” Similarly, Luke says: “At this school, there is a lot of collaboration. Not only within my department, but with other fields. We share how we get stuff done.” By working collaboratively, teachers come to agree on which tools or practices are better than others, and sometimes what they settle on as the right course of action does not always match what public policy discourses anticipate. Teachers are influenced by many factors that become intertwined with their views about public policy like their own interest in doing, as Jane says, “what is best for the students.”

School administrators often arrange social groups by assigning teachers to committees during which teachers are asked to take on leadership roles. For example, John talks about how he has assumed the responsibility to “head up” a new class that many teachers in his department will be delivering next year as part of a statewide initiative. After teaching the class himself for the first time, John plans to “compile all of my information and teachers will take it next year to use it.” John is acting on behalf of public policy discourses to leverage his social relations in support of a new program. In the context of the school, teachers serve as proxies for the agendas of public policy, technology, and teacher discourses.

Many the high school teachers mention that outside of their informal group of friends, other professional groups are convened for them by administrators to achieve collaborative goals. For example, teachers meet as a group at regular intervals throughout the school year to conduct instructional audits for the purpose of coordinating their instruction around a shared curriculum map. As Kim says, teachers meet to ensure everyone is “doing the same thing.” Public policy discourses attempt to turn group relations to their advantage by formalizing and structuring teacher groups in order to limit “possible fields of actions” (Foucault, 1984, p. 221).

At the high school, collaboration is required. Hargreaves (1994) contends that collaboration is a controlling technique: “In contrived collegiality, collaboration among teachers is compulsory, not voluntary; bounded and fixed in time and space; implementation- rather than development-oriented; and meant to be predictable rather than unpredictable in its outcome” (p. 208). In these formal meetings, relations among teachers who would not normally associate with each other are imposed. As Jane explains, for teachers to “get on the same page” administrators and department heads have to get them to “play nicely with one another and put personalities aside. Teachers are people too and like in society, not all lawyers see eye to eye.” Jane suggests that these relationships are not natural – they force teachers who do not like each other to work together. Likewise, Kourtney reveals: “There are some people I have to collaborate with who I like more than others, but we have to be professional.” It is difficult for teachers to avoid or refuse to participate in these group debriefing sessions without feeling isolated socially by their colleagues.

Administrators and teachers in leadership roles attempt to force collegiality and collaboration among department groups to consolidate power. Luke observes how the widespread collaboration that is often initially labeled by teachers as supportive is actually controlling:

At my previous school, I was pretty much left up to my own devices – we were basically able to do what we wanted to do, but here it is more of a controlled environment. Administrators are more intertwined and proactive – a lot more observation and more hands on. It is a close-knit community, and everyone is a lot more involved.

Luke suggests that pervasiveness of what he positively characterizes as a caring, involved, and “close-knit” community that operates to improve teachers has another side. He believes that social control is needed “because there are always a few teachers in every group that are a problem. The controlling does not affect the teachers that are doing what they are supposed to be doing.” The collaborative atmosphere at the high school subtly maintains and sometimes pushes the boundaries in which teachers freely operate, but it is also coercive in the way it can separate certain teachers.

Social relations can isolate and exclude teachers by subjecting them to group norms. For example, Ella reflects on how her department group attempts to impose their prescribed methods on her work:

The school system is pushing for instruction to be more systematic and coordinated. Our department tries for it to be that way. When I joined the school in January of last year, a lot of the lesson plans for one of my classes was already created. When I got here, it was like: “Here you go – this is what you teach.” I am the rogue who does not teach like everyone else because I have my own way and projects that I enjoy doing. Sometimes, I feel like I should be doing what they are doing rather than being the odd one out.

Ella feels isolated because she is not complying with the methods that her colleagues predetermined are correct. For doing things differently, she is seen by others, and she identified herself as an uncooperative “rogue” and she feels guilty about it.

When social groups begin to negatively differentiate, classify, rank and exclude others, the high school teachers often refer to them as “cliques.” Leah, characterizes her colleagues as “acting just like high school students with their gossiping and cliques.” She offers a quick review of the different cliques at the school:

The most exclusive group is the coaches. You have the group that I would consider to be the popular girls. Next, you have your science clique. Then you have those of us that are the ‘weird’ teachers and I consider myself to be in this group. We are people who are kind of socially awkward, who do not have a lot of good conversation. Some of the teachers in this group see the other groups as being mean.

Luke confirms that the coaches and the popular girl groups are the most exclusive and he has “no desire to be a part of them.” Instead, he says that he is “definitely belongs to the nerdy clique” and suggests that there is another group of “younger teachers” that he “hangs out with especially outside of work.” Kourtney identifies herself as belonging to the “popular girl” group, but she also has another group of close friends with “laid back” personalities and teaching styles from outside her department. Like Luke and Leah, Kourtney is not friends with coaches and avoids the “enforcer types” who are act like the “hall monitors” from when she was in high school. She says these teachers “take their jobs too seriously, are sticklers for rules and write kids up for everything.” She is also resentful towards some teachers who she characterizes as “super serious and hyper critical” and are always saying to her: “I would not have done it that way.” As evidenced above, teachers individualize and totalize others and themselves through membership with different groups, which has the effect of reifying the complex order of things, but also leads to conflict. Their told stories reveal a certain micropolitics that constructs local school culture.

As indicated by the comments above, teachers’ relations a very personal and emotional – they have close friends who they love and enemies who they hate. Depending on which groups a teacher belongs to, their attitudes towards conformity and rebelliousness shift. As Leah astutely observes: “Some people gripe inside their own groups, but people in other groups are very vocal and will not hesitate to take a complaint to the top.” The complexity of relations in the school causes resistance and conflict to play out in unpredictable ways. Frequently, teachers are encouraged to stay silent by their peers. For example, Kourtney explains that “typically, when you see people speak up you wish they would shut up. I feel like they complain about things that are not going to change. I feel like they need to pick their battles.” She illustrates her point:

Because of AYP, we had to go through RTI training to improve reading scores. We were all told we had to start teaching reading skills every day in our classes and doing these reading quizzes. I remember this one guy who stood up and said: “I am not going to do that. I have enough to do already.” They just went round and round, and by the end he had to do it. All of us had to sit there and listen to it. That is a typical thing. Why did he bother saying anything in the first place? Where if you have somebody who stands up and says, “I understand what these organizers are having us do, and if you need help come see me.” So, you are going to like people like that who are leaders more than people who are just complaining.

In her comment above, Kourtney characterizes the teacher’s open protests as futile and wasting everyone else’s time. When a teacher is vocal in his or her opposition, this violates the norms that teachers impose on themselves to remain silent and avoid calling attention to themselves. Outward expressions of opposition are generally discouraged. As Ella says, “Sometimes directives are just not open to suggestions. So, other teachers tell me to be quiet and not to rock the boat.”

Teacher and public policy discourses intertwine to socially isolate and exclude both entrenched older teachers who resist change and overly obedient younger teachers who threaten the status quo within a department. For example, Ella, Kourtney, and Kim talk about different “bad” teachers in their departments who are allowed to operate outside the boundaries set for everyone else. Kim talks negatively about a teacher who does not want to participate in the new collaborative model that has been instituted in her department: “He is the only teacher who is still doing it the old way.” Likewise, Ella is frustrated that one of her colleagues will not use a new textbook that in her view is clearly better:

There is one teacher that does not use the new textbook that goes with the exam, but last semester I had more students that passed the exam than she did. She has been teaching for twenty years and is not going to give in. She is going to teach to what she thinks they need to know rather than what is on the certification exam.

Finally, Kourtney believes her rival “gets away with whatever he wants because he has been here forever.” She is expressing her frustration: “Students will skip my class and go to his class because he is not making it available any other time [and] if grades are due on a certain day, he is like: ‘I cannot do that, but I will get them to you when I can.’” Teachers come to resent members of their group who appear to operate according to a different set of rules than everyone else, and they attempt to exclude them by labeling them as the ‘other’.

Sometimes, teachers will withdraw from their department groups to avoid the surveillance of teacher discourses. For example, Leah has an uncooperative rival as well who she characterizes as “very much a lecturer, multiple choice test kind of person who is not going to change anything.” She feels compelled to distance herself from this person and her the other veteran colleagues in her department who are pushing her to compromise her ethics by using shortcuts to instruction. As she says: “I am trying to do deeper learning rather than telling them what they need to know for the test.” She is defending herself against the negative influence of her tenured colleagues who she labels as “having no teaching philosophy” and are only doing the minimum of what “they need to do not get fired.” Basically, she labels most of her colleagues as belonging to the coaches’ group and explains that therefore they do not care about teaching – because they primarily focused on their sport. Her colleagues turn to lectures and multiple-choice tests because it allows them to teach faster, which gives them more time for coaching. Despite her objections, Leah is slowly conceding to the “easy way of teaching” because she does not “want to be known as the troublemaker.” After putting up a good fight in her first year, she confesses that in her second year she is “turning” to the shortcuts. Disappointed in herself, she concedes: “in all honesty, it is just easier.”

3.6. Professional, mediator, and rebel teacher-subject positions

From Foucault’s view, resistance is a struggle to be free from the process of subjectification. He wrote: “Maybe the target nowadays is not to discover what we are but to refuse what we are” (Foucault, 1984, p. 216). Teacher discourses disrupt and challenge public policy and technology discourses and offer teachers options to adopt divergent subject positions. Teacher discourses are more than just a reaction to public policy discourses, they present alternative understandings of relationship between how teachers are expected to serve public policy and technology interests and the possibility for them to create other modes of being.

In this process of interpreting public policy and technology, teachers can modify the official knowledge and implant their own values and principles into that apparatus, thus changing the goals of education. Ideally for teachers, education is based on their personal relationships with students – to adjust education to students’ needs and create learning environments where they are encouraged to seek, discover, and explore knowledge. Teachers find satisfaction in knowing they have made a difference in the lives of students, and they see their professional role as that of a life coach, mentor, or role model who truly cares about students (Rose, 2022). These passionate views stand in opposition to the absolute rationales of public policy and technology discourses. They are the relational ‘truths’ that teachers circulate to reshape power relations.

Teachers reinterpret the directions of public policy through their own experiences, beliefs, and relations with other teachers, which produces teaching practices that are different from what is expected. From teacher discourses emerges a snapshot of a subject position that is characterized by an outward opposition to public policy and technology and a loyalty to the learner- and teacher-centered principles of the ‘professional’. Bandeen (2009) terms this subject position as ‘vocal-resistance’. The professional teacher-subject is typically a veteran tenured teacher who is not afraid to outwardly question public policy and passionately defends his or her power to determine instructional practices in the classroom. Bandeen (2009) describes teachers who assume this subject position as those who possess a “sense of obligation for doing the job well” through their “unique instructional methods” that reflect their personal style of teaching (p. 164).

However, the vocally resistant professional is a subject position that most teachers are not comfortable occupying for long. The continuous barrage of public policy dictates and technology expectations usually overwhelm teachers and have the effect of marginalizing their professional views and silencing their oppositional speech. To avoid being targeted by public policy and technology discourses, teachers take practical steps analogous to what Goffman (1961) calls “secondary adjustments,” which allows teachers to give the superficial appearance of compliance with public policy directives as they work in unauthorized ways (p. 54). Teachers put on a show for administrators when they are being watched, but behind the closed door of their classroom, they continue to apply their own style of instruction.