- 1Indian Institute of Management Udaipur, Udaipur, India

- 2Cherry Creek High School, Greenwood Village, CO, United States

Introduction: While tracking is a powerful determinant of educational inequality, scholarship pays little attention to tracking-related experiences. Tracking-related experiences of students reveal their challenges and coping mechanisms. Consequently, one learns the fundamentals of the agency. This study focuses on tracking the experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA. Between educational and economic success and discrimination, Asian Indians constitute an interesting population to study tracking.

Methods: Data are derived from 177 in-depth interviews with participants from four sample points. And they are analyzed qualitatively using the grounded theory method.

Results: Tracking-related experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students are characterized by a challenge that reflects discrimination featuring the Indian identity.

Discussion: This study extends the theories on educational inequality and racial microaggression.

Introduction

Theories of educational inequality document: (a) tracking as key to the understanding of educational inequality, and (b) the role that economic, social, and cultural backgrounds play in the disparity in educational achievements (Callahan, 2005; Domina et al., 2019). Informing numerous research in past four decades, the theories of primary and secondary effects (Boudon, 1974) and social reproduction (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977) dominate this field of study. Boudon (1974) theorizes that students from higher socio-economic backgrounds enter tracks because they perform better academically than those from lower socio-economic backgrounds (primary effect). Even when academic performance is same, the former group is more likely to enter a track to meet familial expectations (secondary effect). Empirical studies on this theory primarily highlight a logic of rational choice (Erikson and Rudolphi, 2010; Jackson et al., 2012; Morgan, 2012; Schindler and Lörz, 2012; Chmielewski et al., 2013; Jackson, 2013a,b; Crosnoe and Muller, 2014) overlooking the subjective aspects of tracking (Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb, 2010; Kroneberg and Kalter, 2012; Boone and Van Houtte, 2013).

Capturing the subjective aspects of tracking, social reproduction theory (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977) presents tracking as embedded in familial socialization where it is used as a tool to maintain familial status across generations. Accordingly, empirical studies show how economic, social, and cultural capitals play a crucial role in tracking (LeTendre et al., 2003; Kroneberg and Kalter, 2012; Jackson and Jonsson, 2013; Jackson, 2013b; Esser, 2016a,b). A major limitation of this scholarship is its exclusive focus on track selection and educational attainment (Barg, 2013; Lehmann, 2013). Therefore, what remains underexplored is tracking-related experiences. Academic and policy research is yet to learn about the challenges of tracking journeys and how students cope with those challenges to pursue education (Lareau et al., 2016). Besides enhancing clarity on educational inequality, this line of research would also facilitate the understanding of agency (Yonezawa et al., 2002; Carter, 2006). The purpose of this study is to explore tracking-related experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA.

Although Asian Indians in the USA are educationally and economically successful, they are subjected to various forms of inequality (Chakravorty et al., 2017). Situations are worse for second generations who consider the USA as their homeland (Badrinathan et al., 2021). Further, they feel pressured to balance their Indian and American ideologies (Clifford, 1994). While families teach them to value academic accomplishments, they learn the importance of free will from schools (Choi and Thomas, 2009; Kim et al., 2012). Deriving data from 177 in-depth interviews, followed by qualitative analyses, this study reveals the underlying mechanisms that threaten second-generation Asian Indian students in their tracking journeys. In doing so, it builds upon theories of educational inequality and racial microaggression. The remainder of the paper is organized into four sections: (a) review of literature and context, (b) methodology, (c) findings, and (d) discussion.

Review of literature and context

Tracking

Tracking typifies what academic fields students select in their educational journeys. It is a liminal point that determines students’ educational and eventually career achievements (Nikolai and West, 2013). Studies show that educational and socioeconomic inequalities that germinate from tracking also restrict intergenerational mobility (Hanushek and Wößmann, 2006; Dupriez et al., 2008; Pfeffer, 2008; Buchmann and Park, 2009; Van de Werfhorst and Mijs, 2010; Montt, 2011). A combination of factors like demographics, curricula, teachers, and school infrastructure explain such inequality (Brunello and Checchi, 2007). The influence of family and socio-cultural backgrounds also make a difference on students’ early track choices (Bauer and Riphahn, 2006; Jackson and Jonsson, 2013).

Influence of family and socio-cultural backgrounds

Boudon’s (1974) theorization on the distinction between the primary and secondary effects of familial and social backgrounds on tracking influences many empirical studies on social inequality (Erikson and Rudolphi, 2010; Jackson et al., 2012; Morgan, 2012; Schindler and Lörz, 2012; Chmielewski et al., 2013; Jackson, 2013a,b; Crosnoe and Muller, 2014). Boudon (1974) proposes that differential educational attainments in the form of social inequality perpetuates in two forms: (a) differential achievements of individuals from different social backgrounds – the “primary effect,” and (b) variation in decisions to select tracks, irrespective of academic attainments, by individuals from different social backgrounds – the “secondary effect.”

Whereas ethnicity, cultural expectations, and familial socialization shape the primary effects of educational inequality, secondary effects stem from composite differences in educational choices among members of various social groups (Jackson, 2013a,b). A logic of rational choice guides these educational decisions (Jackson, 2013b) when individuals estimate the costs and benefits of prospective success (Erikson and Jonsson, 1996; Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997). This estimation includes maintaining familial status by excluding any chance of downward social mobility (Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997). Using Boudon’s (1974) conceptual paradigm, Dumont et al. (2019) suggest two factors that explain why students from higher socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to enter tracks than their less privileged counterparts: (a) the former group earns higher grades than the latter, and (b) when performance is similar, the former group still chooses academic tracks following their parent’s advice who estimate a greater benefit in academic tracks. However, Boudon’s (1974) theory provide only a partial understanding of educational inequality because it omits several experiential strands of track selection (Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb, 2010; Kroneberg and Kalter, 2012; Boone and Van Houtte, 2013).

Experiential strands of track selection

Social reproduction theory (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977) explains how students’ track selections are guided by their families and social circles (Jackson and Jonsson, 2013; Jackson, 2013b) – that Bourdieu (1980, 1984) calls “habitus.” Individuals with similar habitus would (a) behave in the same way – as they undergo similar socialization processes and (b) take decisions and actions in a way that would maintain the characteristics of the habitus – a phenomenon known as “social reproduction” (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977; Bourdieu, 1980, 1984). For example, in the USA, parents from privileged backgrounds do not necessarily make “rational choices” while influencing track selection. Rather, tracking is practiced in these families for generations (Domina et al., 2019). Another example is the Wisconsin status attainment model (Sewell et al., 1969, 1970, 2003) suggesting that educational success of students is primarily influenced by parental aspirations, familial aspirations, and those of significant others. These aspirations also reflect familial and social status of individuals (Singh et al., 1995; Suizzo and Stapleton, 2007). That is, economic, cultural, and social capitals are key to understanding educational inequality (LeTendre et al., 2003; Kroneberg and Kalter, 2012).

Esser (2016a,b) combines social reproduction theory (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977) with Boudon’s (1974) theorization to propose the concept of “tertiary effect.” The author posits that economic, cultural, and social capitals are also transmitted by schools and teachers via stereotypical expectations from specific groups of students leading to self-fulfilling prophecies. These phenomena are manifested through teacher-student and teacher-parent interactions, teachers’ evaluations, and teachers’ recommendations (Singh et al., 1995; Suizzo and Stapleton, 2007). Sometimes teachers’ attitudes and actions are so biased by students’ backgrounds that their academic performance becomes irrelevant (Suizzo and Stapleton, 2007; Esser, 2016a,b). For example, Mayer et al. (2018) examine how teachers systematically structure school environment favoring high-track students over the low-track ones. The teachers do so by setting higher expectations and offering greater support to high-track students.

Tracking: empirical studies

Confirming the theory of primary effect (Boudon, 1974), studies across countries show that students from more privileged backgrounds are more likely to enter coveted tracks compared to less privileged students (Kelly, 2008; Jaeger, 2009; Barg, 2013; Boone and Van Houtte, 2013; Jackson, 2013a). The effects of social backgrounds on tracking surface when students’ performance is controlled for – supporting Boudon’s (1974) secondary effect (Kelly, 2008; Jackson, 2013a). Secondary effect is also supported by large-scale survey data like Stocké’s (2007) study on social class position and evidence from non-compulsory education like Breen et al.’s (2014) study on risk aversion and time discounting preferences. However, these results present social background as a homogenous variable without explicating what specific aspects of social backgrounds make the difference in academic track selections (Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb, 2010; Glaesser and Cooper, 2011; Umansky, 2016).

To identify nuances of social backgrounds, the trend of research on educational inequality shifted from quantitative to mixed and qualitative methodologies. In alignment with social reproduction theory (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977), mixed-method studies (Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb, 2010; Boone and Van Houtte, 2013) suggest that students from more privileged backgrounds fulfil the expectations of their “college-going habitus” (social circles). That is, they seek admissions in colleges where they thought they would go since their childhood. Characteristics of parents also emerge as a major predictor of children’s academic tracking in many qualitative studies. Investigations in middle and high schools (Baker and Stevenson, 1986; Useem, 1991, 1992) find that parents with college education are more involved with children’s education. They maintain greater contact with teachers and other school personnel, and encourage their children to enter an advanced track as compared to parents without any college education (Baker and Stevenson, 1986; Useem, 1991, 1992). Lareau (1987) and Lareau et al. (2016) posit that parental characteristics are reflections of their economic, cultural, and social capitals [also Bourdieu’s (1980, 1984) notion]. Parents from all socio-economic backgrounds are supportive of their children’s academic success. Nonetheless, parents with higher socio-economic status have access to resources and ancillary support – which facilitates academic success of students (Lareau, 1987; Lareau et al., 2016). Esser’s (2016a,b) concept of tertiary effect is also reinforced when the influence of teachers and schools on track placement is reported (Haussling, 2010). Next, we present empirical studies on how students perceive their educational experiences in the context of educational inequality.

Students’ perceptions of educational experience

Underpinning the importance of cognitive skills Bowles and Gintis (2002) suggest that students from privileged backgrounds view their school curriculum vis-à-vis their future educational and job prospects differently than students from less privileged backgrounds. Students also believe that teachers’ attitudes and control mechanisms vary by their social backgrounds (Anyon, 1980; Wilcox, 1982). With regards to social class, Lareau and Weininger (2003) observe that students with middle-class parents see themselves as more assertive, outgoing, and industrious than students from working class families. The former group believes they have better conversational skills [a necessary component of educational success (Streib, 2011; Calarco, 2014)] than the latter (Lareau, 2003). According to research on noncognitive skills, students assert that their behavioral skills are shaped by their social backgrounds (Duckworth and Seligman, 2005; Jennings and DiPrete, 2010).

Although cognitive and non-cognitive skills are essential for educational attainments, “one of the most significant problems in higher education is the low rate of college completion among low-income, minority, and first-generation college students” (Golann, 2018, p. 106). Apart from academic and financial challenges, many working-class students find it hard to adapt to college environments. This is because colleges are less structured than schools, and students are expected to navigate their ways independently (Agliata and Renk, 2008; Kim and Torquati, 2019). Canney and Byrne (2006) call this trait of adaptation the “social skill” that impacts students’ interactional processes, reproducing educational inequality. Evidently, current studies focus exclusively on what socio-economic factors impact educational inequality. There is very little clarity on how students actually experience tracking (Barg, 2013; Lehmann, 2013). Explorations of tracking-related experiences are important to gain a holistic understanding of challenges that students face and their coping mechanisms (Lareau et al., 2016). In the process, the fundamentals of agency are determined (Yonezawa et al., 2002; Carter, 2006). In this study, we address this gap and explore tracking-related experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA.

The context: second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA

Since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 allowing free-flowing immigration to the United States, the Asian Indian community has come a long way. Among 4.2 million Indians who reside in the USA, today, 1.2 million are second-generation (Badrinathan et al., 2021). The community’s growing size, academic, and economic success rapidly increase its visibility (Chakravorty et al., 2017). It is often referred to as the “model minority” (Ng et al., 2007). However, this image often disguises the extent of inequality that Asian Indians experience in America (Chakravorty et al., 2017).

At this backdrop, situation of the second-generation is unique. They consider the USA as their homeland yet they must constantly balance familial traditions (such as valuing the importance of tracking) vis-à-vis American ideologies of independent thinking, mostly learned in schools (Clifford, 1994; Choi and Thomas, 2009; Kim et al., 2012; Badrinathan et al., 2021). Scholarship on education of Asian Americans focuses essentially on marginalization, illustrating predicaments of Asian students who are considered as vulnerable as students from other marginalized groups (Chang et al., 2010; Byun and Park, 2012; Gündemir et al., 2019). Unfortunately, this literature stacks all Asian groups as one disregarding specific cultural and ethnic differences (Purkayastha, 2005). Because a deeper insight into inequality is possible via ethnicity-focused research (Chakravorty et al., 2017), in this study, we explore educational inequality via tracking-related experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA.

Methodology

Sample and data collection

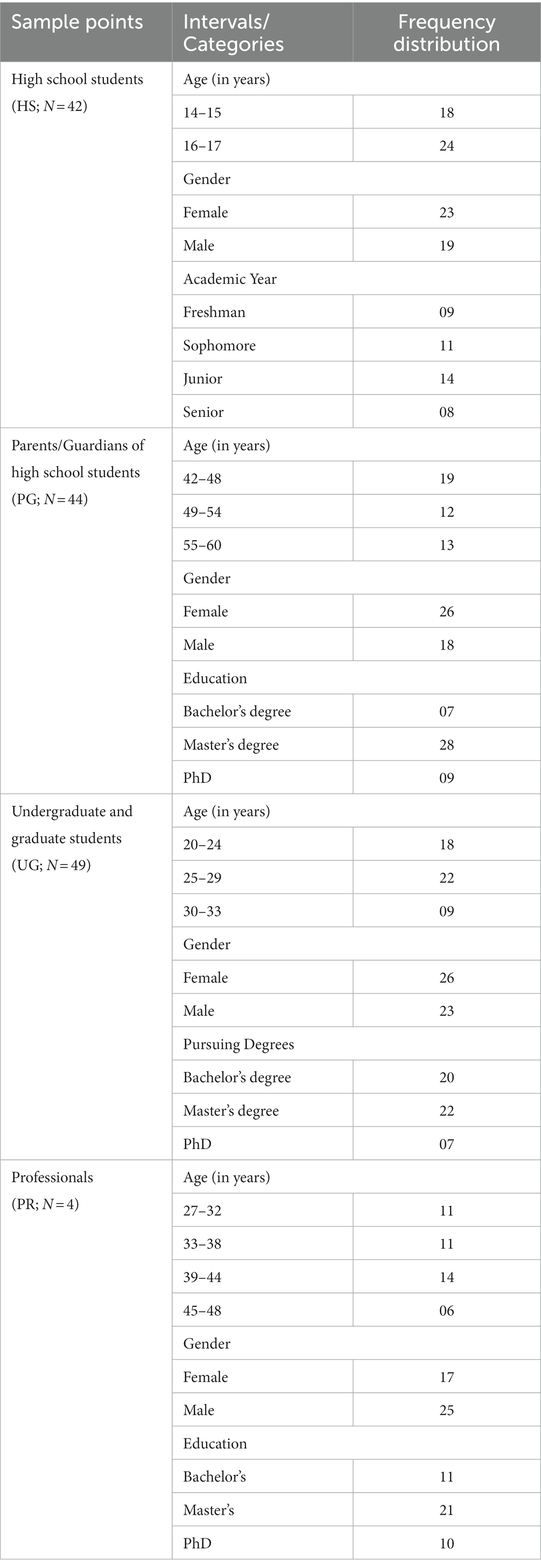

Data were derived from 177 semi-structured in-depth interviews with: (a) second-generation Asian Indian high school students (HS; N = 42), (b) parents/guardians of second-generation Asian Indian high school students (PG; N = 44), (c) second-generation Asian Indian undergraduate and graduate students (UG; N = 49), and (d) second-generation Asian Indian professionals (PR; N = 42). To obtain varied viewpoints, we did not interview the parents/guardians of high school students in sample point (a). Retaining focus on the research objective (Hesse-Biber and Leavy, 2011; Billups, 2019), tracking-related experiences of the second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA, questions primarily revolved around four themes: (a) perceptions about tracking while experiencing tracking, (b) challenges encountered during tracking, (c) coping mechanisms, and (d) support and inspiration facilitating coping.

The social world is structured by individuals whose agency is impacted by how they surmise the context (Giddens, 1984). Meaning only a context-specific study of academic experiences is more likely to reveal the underlying inequalities holistically (Carter, 2006). Experiences of students vary from public to private schools (Cohen-Zada and Sander, 2008; Dills and Mulholland, 2010) and experiences of Asian Indians in the USA also vary by religion (Badrinathan et al., 2021). Thus, we interviewed individuals (and their parents/guardians) who went to public schools and identified Hinduism as their religion. Using purposive sampling technique that promotes the selection of most informative individuals (DeFeo, 2013), we recruited our participants by means of personal contacts, social media platforms, and snowballing. Interviews, conducted virtually, ranged from 90 to 200 min. We stopped collecting data after the data reached theoretical saturation (Charmaz, 2006).

Interviews often create unequal power relations (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000; Alvesson, 2003), when presence of interviewers may restrict the participants from speaking freely (Czarniawska, 2004). The first author and three post-doctoral researchers conducted the interviews. All of them are Indians with Master’s and PhD degrees from US universities and were Asian Indians in the US for at least 10 years. The most vulnerable group was the high school students. We interviewed them in presence of both parents/guardians. Each participant was contacted before formal interviews by specific interviewers. Purpose of that informal 20 to 30 min long conversation was: (a) to re-brief the participant about the study, (b) to remind (the consent form was signed already) about the voluntary nature of participation, and (c) to remind that participants could terminate the interview if there was any inconvenience. An interviewer-participant rapport was established during those informal conversations allowing the participants to feel comfortable during the formal interviews. Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. We sent each transcribed interview to the respective participant for approval and used only the approved version of the data for analyses. Being conscious of the enormity of interviews, the research team met at least once a week to assure that it remained focused on the research objective and there w no drift in the data collection process as the project moved forward.

Data analyses

At the onset of data collection, we were astounded by the intense emotions and feelings of despondency that our participants expressed. Also, we were perplexed by the extent of their perseverance and enthusiasm. For example, one of the high school students commented, “There is too much pressure in tracking. I feel so stressed out and frustrated that sometimes I want the world to collapse.” But just after 22 min the participant said, “I am amazed I survived middle school. That’s something. If I could do that, I can also deal with high school. I actually feel excited about my studies” (HS17). To comprehend the dynamics of these conflicting views on tracking-related experiences, we used the grounded theory method of data analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2006). In the field of education, this method is particularly useful for analyzing situated processes and facilitates the examination of complex phenomena through its ability to produce a distinct account of individual actions in each context (Golann, 2018). It also provides an understanding of the roles that individuals play given their situations, connecting findings with practice (Corley, 2015). Additionally, it is a method recommended when an area or population of study is underexplored (Walsh et al., 2015).

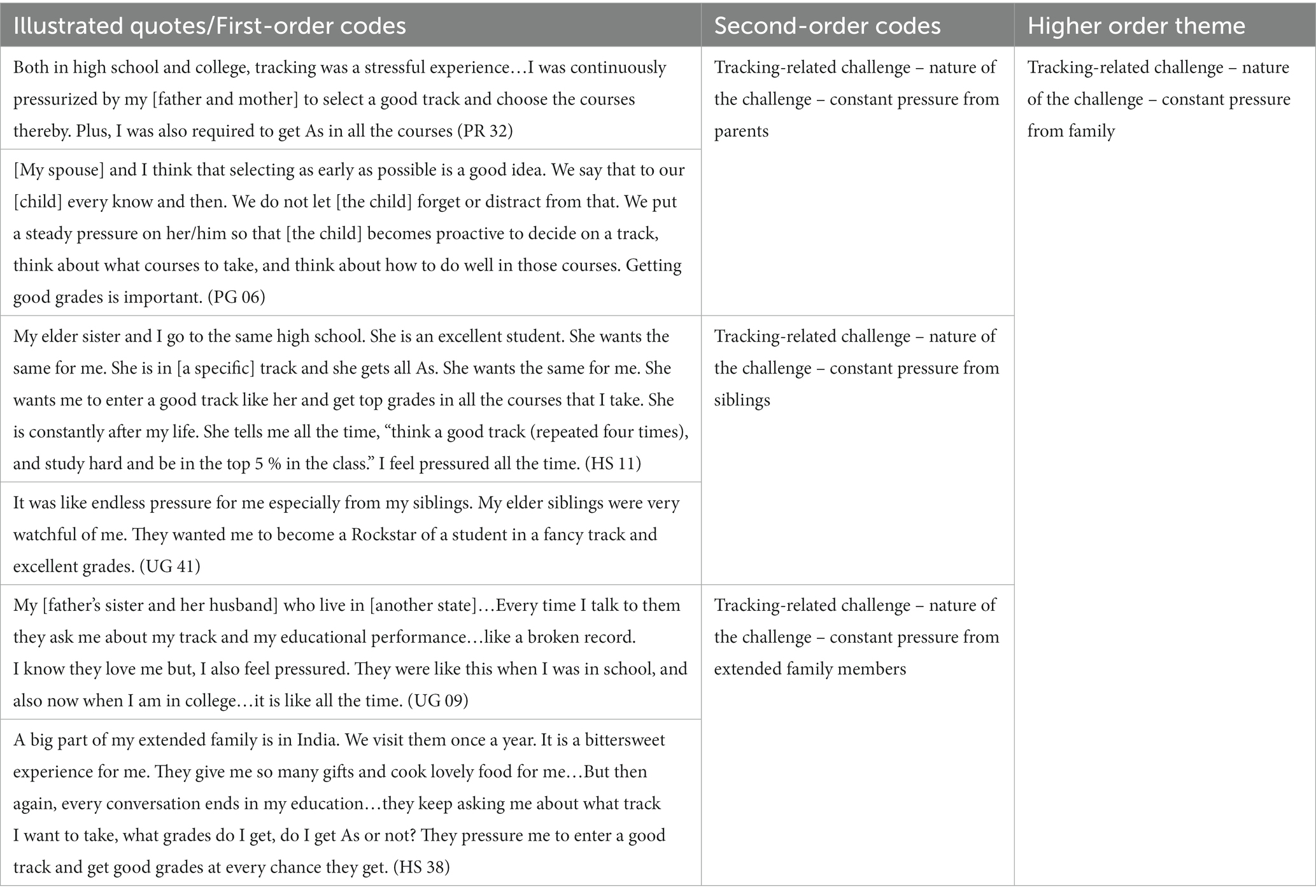

In accordance with grounded theory method we analyzed the data concurrently with data collection, in two separate yet overlapping steps (Charmaz, 2006; Miles et al., 2019). In step one, we identified the first and second-order codes. Because the second author was an apprentice the authors worked as a group. The author duo and post-doctoral researchers worked separately in this step. We read each interview carefully going back and forth between the data and the literature on tracking, educational inequality, and marginalization. For every datum, we noted each statement with similar expressions (first-order codes) and condensed those into a high-order theme (second-order codes). After listing the codes for each interview, the research team met at least three times to finalize the codes based on rationale obtained from the literature. Disagreements were resolved with further discussion and consensus. To stay close to the data, we used descriptions and terminologies of the participants (Charmaz, 2006, 2014; Miles et al., 2019). For example, statements on tracking-related experiences were peppered with expressions of challenge which were organized as the first order code “nature of challenge.” Further, within families this challenge was characterized by constant pressure from three distinct sources – parents, siblings, and extended family members. We second-order coded them as “tracking related challenge-nature of challenge- constant pressure from parents,” “tracking related challenge-nature of challenge- constant pressure from siblings,” and “tracking related challenge-nature of challenge- constant pressure from extended family members.” After assessing the reliability of our coding scheme (the percentage of inter-coder agreement varied from 0.84 to 0.91 – considerably higher than Cohen’s (1960) suggestion of the minimum of 0.70) and attesting that the findings represented the data accurately, we analyzed the next interviews. We repeated this step upon further data collection, receiving feedback from our project mentors (two second-generation Asian Indian social science professors in the US), and consulting the literature. We maintained a detailed record of our interpretations of every datum in the forms of tables, flow charts, rough sketches, and other visual representations to determine relationships among the emerged codes.

In step two, authors and post-doctoral researchers worked together to develop higher order themes (see Table 1 for an example of the coding scheme). We also actively engaged in understanding the relationships among them. To do so, we visited and revisited the literature to ensure that our meaning-makings were theoretically grounded. We found out how students perceived their tracking-related experiences in terms of challenges, consequences of those challenges, and coping processes. Reliability in this stage was determined with the help of member checks (Gioia et al., 2012). We randomly selected 25 participants from each sample point to present our findings and interpretations. The participants approved the findings and agreed with our data interpretations (see Table 2 for profile of the participants).

Findings

Our research objective was to explore tracking-related experiences of the second-generation Asian-Indian students in the USA. Data analyses reveal that this experience is characterized by a challenge from two sources, family and school.

Tracking-related challenge

Tracking-related challenge includes a “constant pressure” to select a track and get good grades. Within the families, academic pressure was experienced from parents, siblings, and extended family members.

No conversation with my parents is ever complete without some discussion on tracking and good grades. Say you are talking about the weather – suddenly [the father] will start talking about atmosphere and nature studies. He always pushes me to find a stream and excel in it … It’s like I am under a constant pressure to think about tracking and getting As (HS31).

My younger [sibling] was a straight A science student, so there was this constant comparison … B was considered a taboo in my family. If I got a B, [the sibling] would always point out that I was falling short of the familial standard because I will not get a good track (PR10).

Our family in India comprises very accomplished academically. They want the same for our [child]. Whenever we visit them, they always ask my [child] about [her/his] academic track and grades. [The child] feels a constant pressure to do well (PG22).

Students experience similar challenge in schools.

Since [Asian-Indians] are good students, my teachers and classmates put very high expectations on me. They often tell me, “We know you will get a good track and do great. You are a good student.” I am always in a state of anxiety and distress that no matter what, I must get an A+ and enter a good track. As if I have no other option. It is such a pressure (HS05).

The constant pressure of track selection and good grades is aggravated in schools when the Indian identity becomes prominent. Our data suggest that the analogy of Asian Indians with “a strong academic record” create a sense of discrimination.

My middle school and high school teachers told a lot, “Oh you are an Indian. Then you will have a strong academic record and you will get into a good track.” Well, it seemed rather derogatory. It was discrimination because those comments instantly separated me from other children in my class (UG33).

During my undergrad days there was this stereotype that [the Asian Indians] are the nerds and geeks who always aspire to be great scholars in great tracks … and nothing else … it was a bad feeling. I felt left out and discriminated. I had very few friends (PR16).

Resonating with theories on educational inequality (Boudon, 1974; Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977), findings of this study show the influence of cultural background on tracking. Yet, unlike previous studies, our data present: (a) this influence as a challenge in the form of a constant pressure than as a positive resource and, (b) the Indian identity as key to understanding of cultural background. Further, the pressure in school, underpinning the salience of Indian identity, reflects a sense of discrimination, that creates a sense of disconnect among students.

Consequence of tracking-related challenge: sense of disconnect

The students in this study experience discrimination in the form of disconnect from their schools and the country.

I felt that there was no connection between me and my high school or university. It was a feeling that my classmates did not like me because I was an Indian … in a good track … good in studies … it was like an invisible force of hatred. I did not feel like a part of my school or university (PR19).

[The spouse] and I believe that [the child] feels disconnected from her/his studies. In school she/he is often singled out as “that Indian high achiever.” [The child] feels lonely and depressed and not a part of the school community (PG24).

It all starts with tracking, getting good grades and being an Indian. When you excel in studies, people don’t like you. They will not make it apparent, but you will understand from their attitudes that they don’t like you … It is a subtle and invisible thing. For me it started in school, I also felt left out in college and now in university…so, when I go to the outside world, I don’t feel a part of it either. Though I see this country as my home, I feel I don’t belong here (UG26).

The “subtle and invisible” process through which social inequality is perpetuated is called microaggression (Pierce, 1970). In the context of education, microaggression refers to the interpersonal forms of inequality that are practiced systemically against members of marginalized groups (Sue et al., 2007a,b, 2008). Our data show that second-generation Asian Indian students experience microaggression in the form of isolation and disconnect. The purpose of focusing on tracking-related experience was also to identify the coping mechanisms of students. This understanding is important because students in this study lack a sense of belonging with their educational communities.

Coping mechanisms

When students feel disconnected, they decide not to let go but to engage in an active conversation. The younger (high school) students reach out to their parents.

Sometimes I feel that I will let it go and not do anything but then I decide against it. I decide to talk to someone. I am taught in school and by my parents…I must not leave any doubt unresolved. So, I talk to my parents when I feel lonely and secluded in school. They tell me that people are not bad. Sometimes they do things even without being aware of what they are doing … If I want [the parents] are willing to go and talk to the teachers. But I do not want that. I fear that it will single me out even more. [The parents] also tell me that once I enter a good track, get my degree, get a good job, these bad experiences will be over. I stick to that hope (HS40).

Students learn to leave no “doubt unresolved.” However, the experience of microaggression prevent them from allowing their parents to talk to school personnel. Instead, they prefer to dwell in the hope of a better future by finding excellence.

My parents told me all the time … if I go to a good grad school in a good track, everything will be alright … since students are older and more matured in grad school. That did not happen. My classmates still tease me as the Indian high achiever. I am still left out. It is a very depressing and stressful feeling. But still, I talk to people about it. I talk to my classmates, my teachers, my counselor – whoever is approachable. Bottling things up will not help. People need to know that things are going wrong. I think that is the best way of coping (UG21).

I entered a very good track. I graduated with both my Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees being among the top five percent in my class. But still, in many job interviews I had to hear that “Oh you are an Indian! No wonder your grades are so high.” As if I did not work hard at all. As if Indians are born with good tracks and good grades … I felt sad, frustrated, and sometimes severely insulted … My children often come to me and share when they feel lonely in school. In spite of what I went through I give them hope that things will improve if they focus on their studies, you know … good track, good grades. I don’t believe that I give them a false hope. I truly believe that the world will become a better place. It will take some time, a lot of awareness, and a lot of conversation. But yes, you have to have the courage to talk things out. That’s how you cope and that’s how you spread the awareness (PR35).

Our data revealed that the “courage to talk things out” is fundamental in understanding how students deal with their tracking-related challenges – constant pressure and microaggression. This courage represent an element of strength and self-motivation to improve the situation and believe that the “world will become a better place” – an idea that falls under the purview of agency (Kao and Thompson, 2003). Indeed, the most pressing question in the context of educational experiences (and inequality) is how individuals realize their agency to traverse through adversities (Yonezawa et al., 2002; Carter, 2006).

Source of agency

When tracking leads to pressure and microaggression, students practice their agency via active conversation. In the process, they derive strength and inspirations from their family members.

My father and my mother motivate me to fight this. They sacrifice a lot for me. They don’t have any “me time.”… Their jobs are very demanding. But still, they are always there for me … attending to all my needs … specially educational and emotional. If despite their hardships they can make me happy, I can also fight my challenges and make them happy. They give me a lot of strength and courage (HS26).

My elder [sibling] was my role model. We lost our mother when we were very young. She/he became my [parent] since then. Our father was a very busy doctor … You can say that [the elder sibling] brought me up. She/he was a very hardworking and accomplished student. She/he always helped me with my studies and made sure that my grades were intact. She/he was my big inspiration. She/he could relate to my academic pressures, my feeling of loneliness in school, my mental and emotional ups and downs. She/he encouraged me to open up and share my feelings (PR04).

I am a single parent. I hold two jobs. No matter how busy or tired I am, I always help my children the best way I can. I teach them that they can overcome every challenge with hard work, perseverance, and open conversation. They say that they get a lot of strength and inspiration from me. When they are overwhelmed out of study load … loneliness and depression in school, they come and talk to me … I always encourage a free conversation. You see I think that’s why Indian parents are so serious about education … it helps you to talk to others and spread awareness. Education is the biggest weapon to fight discrimination. I know my children feel better after a good and healthy conversation … they also acknowledge and appreciate that (PG37).

Interestingly, students in this study find agency in one of the sources (family) that also create the tracking-related challenge of “constant pressure” for them.

Discussion

We explore tracking-related experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA. Our findings suggest that students experience tracking as a challenge. It is a constant pressure to enter a track and get good grades. In schools, this pressure also associates with a sense of discrimination highlighting the Indian identity and leading to microaggression. Consequently, students feel disconnected with their educational communities and the country. Because they “truly believe that the world will become a better place” (PR 35), they cope and practice agency by engaging in open conversations with others. In the process they derive strength and inspiration from their family members.

Implications in relation to the existing literature: theories on educational inequality

Our results support the theories on educational inequality. We find that students are concurrently pressured to get good grades and select a track – indicating that educational achievement might explain track selection. Our data also presents the Indian identity as a major determinant of pressure and aligns with Boudon’s (1974) categorizations of primary and secondary effects. This study extends Boudon’s (1974) concept by showing that primary and secondary effects are not mutually exclusive for second-generation Asian-Indian students in the USA. Rather, those are overlapping in nature. This study also contributes to Boudon’s (1974) paradigm by presenting a novel explanation of the logic of rational choice. One of the limitations of Boudon’s (1974) theorization is that it provides a partial understanding of the logic of rational choice (Kroneberg and Kalter, 2012; Boone and Van Houtte, 2013). Building a promising career, maintaining familial status, and preventing downward social mobility constitute the major components of this logic (Erikson and Jonsson, 1996; Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997; Dumont et al., 2019). The narratives of our participants, however, offer a different meaning to this logic. Selecting a track and getting good grades is used as a tool to encounter the perceived discrimination that Asian Indians experience in the USA. Our participants believe that “education is the biggest weapon to fight discrimination” (PG37).

Empirical studies on educational inequality pay specific attention to the aspects of socio-cultural environment that impact tracking. For instance, applying the ideas of social reproduction theory (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977) and the concept of socio-cultural “habitus” (Bourdieu, 1980, 1984) in the field of educational inequality, Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb (2010) propose the notion of “college-going habitus.” The authors pinpoint the importance of college-going (and track-selecting) traditions of families that automatically socialize students to select a track. Likewise, scholars identify the roles that parents’ education (Baker and Stevenson, 1986; Useem, 1991, 1992), parents’ socio-economic capital (Lareau, 1987; Lareau et al., 2016), and teachers’ perceptions (Haussling, 2010) play when students select a track. Our data shows that the socialization process of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA is dominated by a facet of ‘Indian-ness’ where being Indian is equated with educational excellence. Here, it is the Indian identity that primarily characterizes the students’ cultural and social capital in schools. Consequently, this study builds upon the social reproduction theory (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977) and Bourdieu’s (1980, 1984) idea on socio-cultural “habitus” by detecting another aspect of the socio-cultural environment that impacts tracking – the ethnic identity.

According to our data, the effect of the Indian identity (its analogy with educational excellence) is prevalent in schools and manifested via schoolteachers’ and schoolmates’ attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, this study also advances Esser’s (2016a,b) theorization on tertiary effect. Students in this study are reminded of their Indian identity in schools by their teachers and friends. Mention of the Indian identity in schools is also in relation to the Asian Indian students’ educational attainments. There is a common belief that Asian Indian students enter a good track and get good grades. This assumption, in turn, urges Asian Indians to select a track and excel in studies.

An exclusive focus on socio-economic background and educational inequality often diverts attention away from tracking-related experiences (Barg, 2013; Lehmann, 2013). Exploration of tracking experiences not only reveals how students perceive inequality (Lareau et al., 2016), but also enables researchers to tap into agency (Carter, 2006). We address this concern by delving into the experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA. We find that when focus is shifted to tracking-related experiences, the influence of cultural capital is perceived as a challenge in the form of constant pressure and not as a positive asset. Moreover, this challenge represents a sense of discrimination underpinning the salience of Indian identity.

Implications in relation to the existing literature: theory of racial microaggression

Critical race theory explains the ways in which racial/ethnic inequality is perpetuated in the USA through an examination of various institutional, structural, and systemic processes (Feagin, 2006; Bracey, 2015; Golash-Boza, 2016). Theory of racial microaggression is a branch of the critical race theory that focuses on the practices and processes of inequality that are not quite visible (Pierce, 1970; Sue et al., 2007a,b, 2008). Microaggression includes microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations. Microassaults are conscious and intentional behaviors and actions to demean others. Microinsults refer to unconscious yet derogatory remarks toward members of marginalized groups. And microinvalidations indicate the acts of ignoring the people of color (Sue et al., 2007a,b).

The grounded theory method of data analyses revealed the mechanisms of racial microaggression that deplete the sense of belonging of second-generation Asian Indian students in the US. Usually students from minority groups experience microinsults when members of the dominant groups perceive them as intellectually inferior (Lewis et al., 2019). This study is one of the first to present that the contrary perception also leads to microaggression. Being perceived as good students was not rewarding for Asian Indians. This is because, “when you excel in studies, people do not like you. They will not make it apparent, but you will understand it from their attitudes that they do not like you” (UG26). As a result, students feel left out and socially secluded and lose their sense of belonging in their educational communities. This mechanism of ethnic microaggression has a far reaching and debilitating impact since Asian Indians also feel disconnected from the country – which may influence their mental and emotional well-being negatively. Indeed, the perceptions of the dominant group often hurt and discourage members of minority groups who feel hesitant to assimilate since they experience a constant disconnect from their surroundings (Hughey et al., 2015; Delgado and Stefancic, 2017).

Our study shows that focusing on tracking-related experiences reveals a great deal about how students cope with their challenges and where they derive their agencies from. Whereas it is important to have various initiatives in schools and colleges to make sure that minority students gain a strong sense of belonging (Moore and Bell, 2011), our data show that the second-generation Asian Indians cope by engaging in open conversations. They believe that sharing their concerns will “spread the awareness” (PR35) of what is wrong. And this awareness is vital in improving social relations because “people are not bad, sometimes they do things even without being aware of what they are doing” (HS40). In the process, the second-generation Asian Indian students derive their courage and strength from their family members. Notably, they derive their agencies from the same source that is also responsible for creating the tracking-related constant pressure for them. This is where Boudon (1974) and Bourdieu’s (1980, 1984) theorizations on the importance of familial backgrounds serve useful.

Families act as support systems that encourage individuals to aspire for a better future (Boudon, 1974; Bourdieu, 1980, 1984). Our study shows that this support often takes the form of coercion so that students fulfill their familial expectations. However, families do not engage in microaggression. Rather, “they sacrifice a lot for [the students]” (HS26) and inspire them to cope with their challenges. This study, therefore, contributes to the theory of racial microaggression that focuses on students’ experiences by (a) paying attention to the tracking-related experiences, (b) presenting the coping mechanisms of the students in response to microaggression, (c) highlighting the formation of agency, and (d) complementing it with the theories of educational inequality (Boudon, 1974; Bourdieu, 1980, 1984).

Study limitations

First, education of the parents could have influenced the findings of this study. All parents interviewed had at least one college degree. Second, teachers, counselors, academic advisors, and schoolmates play important roles in students’ tracking journeys. We did not include them in our sample as our data were already quite extensive. Third, the nature of school (public) and religion showed hardly any effect on tracking experiences. Nonetheless, these factors might influence students’ educational experiences in other ways. This study could also benefit by collecting data from parents-offspring dyads by establishing direct correlations of viewpoints. Fourth, our findings, based on a segment of a specific population, do not have the potential to be generalized. And fifth, while qualitative studies enhance in-depth understanding of a phenomenon, mixed-method studies strengthen research by allowing researchers to support their qualitative data with the quantitative ones (Grodsky and Riegle-Crumb, 2010; Boone and Van Houtte, 2013).

Implications for practice

A focus on tracking-specific experience and use of grounded theory technique uncover the existence of microaggression in tracking journeys of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA. This study is a part of the research that continues to show how microaggression deteriorates physical, mental, and emotional well-being of marginalized sections in the USA (Sue et al., 2007a,b, 2008; Lewis et al., 2019). Asian-Indian students suffer from a sense of disconnect from their educational communities and the country that they consider their homeland. On a bright side, our results also reveal the power of open communication that aids coping and fosters agency. Academic institutions could use this idea to eliminate microaggression and promote a healthy learning environment. Our findings inform two approaches to tackle microaggression. First, a reactionary approach where institutions could encourage students by spreading the awareness about the details of microaggression, and the importance of not to tolerate microaggression. Accordingly, the institutes should nurture an ecosystem where students would feel safe and free to seek support via engaging in open conversations. Second, a prevention approach where institutes could develop a culture of empathy encouraging students to express themselves. Yet, they would also learn to value different opinions believing that difference is not necessarily a path to conflict. And open conversations could be the fundamental of such a cultural landscape.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the research team copyrights the primary data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to DB, ZGluYS5iYW5lcmplZUBpaW11LmFjLmlu.

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board Committee of the Indian Institute of Management Udaipur approved the studies involving humans. The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the adult participants and the minor participants’ parents/legal guardians.

Author contributions

DB conceived and designed the analyses, collected the data, performed the analyses, and wrote parts of the manuscript. AB conceived the research problem, suggested the population, performed data analyses, and wrote parts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agliata, A. K., and Renk, K. (2008). College students’ adjustment: the role of parents-college student expectation discrepancies and communication reciprocity. J. Youth Adolesc. 37, 967–982. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9200-8

Alvesson, M. (2003). Beyond neopositivists, romantics, and localists: a reflexive approach to interviews in organizational research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 28, 13–33. doi: 10.5465/amr.2003.8925191

Anyon, J. (1980). Social class and the hidden curriculum of work. J. Educ. 162, 67–92. doi: 10.1177/002205748016200106

Badrinathan, S., Kapur, D., Kay, J., and Vaishnav, M. (2021). Social realities of Indian Americans: Results from the 2020 Indian American attitudes survey,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Vaishnav_etal_IAASpt3_Final.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2021).

Baker, D. P., and Stevenson, D. L. (1986). Mothers’ strategies for children’s school achievement: managing the transition to high school. Sociol. Educ. 59, 156–166. doi: 10.2307/2112340

Barg, K. (2013). The influence of students’ social background and parental involvement on teachers’ school track choices: reasons and consequences. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 29, 565–579. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr104

Bauer, P., and Riphahn, R. T. (2006). Timing of school tracking as a determinant of intergenerational transmission of education. Econ. Lett. 91, 90–97.

Billups, F. D. (2019). Qualitative data collection tools: Design, development, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Boone, S., and Van Houtte, M. (2013). In search of the mechanisms conducive to class differentials in educational choice: a mixed method research. Sociol. Rev. 61, 549–572. doi: 10.1111/1467-954X.12031

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity, and social inequality: Changing prospects in Western society. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J.-C.. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bowles, S., and Gintis, H. (2002). Schooling in capitalist America revisited. Sociol. Educ. 75, 1–18. doi: 10.2307/3090251

Bracey, G. E. II (2015). Toward a critical race theory of state. Crit. Sociol. 41, 553–572. doi: 10.1177/0896920513504600

Breen, R., and Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: towards a formal rational action theory. Ration. Soc. 9, 275–305. doi: 10.1177/104346397009003002

Breen, R., Van de Werfhorst, H., and Jaeger, M. M. (2014). Deciding under doubt: a theory of risk aversion, time discounting preferences, and educational decision-making. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 30, 258–270. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcu039

Brunello, G., and Checchi, D. (2007). Does school tracking affect equality of opportunity? New Int. Evid. Econ. Policy 22, 781–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0327.2007.00189.x

Buchmann, C., and Park, H. (2009). Stratification and the formation of expectations in highly differentiated educational systems. Res. Soc. Stratificat. Mobility 27, 245–267. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2009.10.003

Byun, S.-Y., and Park, H. (2012). The academic success of east Asian American youth: the role of shadow education. Sociol. Educ. 85, 40–60. doi: 10.1177/0038040711417009

Calarco, J. M. (2014). The inconsistent curriculum: cultural tool kits and student interpretations of ambiguous expectations. Soc. Psychol. Q. 77, 185–209. doi: 10.1177/0190272514521438

Callahan, R. M. (2005). Tracking and high school English learners: limiting opportunity to learn. Am. Educ. Res. J. 42, 305–328. doi: 10.3102/00028312042002305

Canney, C., and Byrne, A. (2006). Evaluating circle time as a support to social skills development reflections on a journey in school-based research. British J. Spec. Educ. 33, 19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2006.00407.x

Carter, P. L. (2006). Straddling boundaries: identity, culture, and school. Sociol. Educ. 79, 304–328. doi: 10.1177/003804070607900402

Chakravorty, S., Kapur, D., and Singh, N. (2017). The other one percent: Indians in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chang, E. S., Heckhausen, J., Greenberger, E., and Chen, C. (2010). Shared agency with parents for educational goals: ethnic differences and implications for college adjustment. J. Youth Adolesc. 39, 1293–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9488-7

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Grounded theory in global perspective: reviews by international researchers. Qual. Inq. 20, 1074–1084. doi: 10.1177/1077800414545235

Chmielewski, A. K., Dumont, H., and Trautwein, U. (2013). Tracking effects depend on tracking type: an international comparison of students’ mathematics self-concept. Am. Educ. Res. J. 50, 925–957. doi: 10.3102/0002831213489843

Choi, J. B., and Thomas, M. (2009). Predictive factors of acculturation attitudes and social support among Asian immigrants in the USA. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 18, 76–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2008.00567.x

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104

Cohen-Zada, D., and Sander, W. (2008). Religion, religiosity and private school choice: implications for estimating the effectiveness of private schools. J. Urban Econ. 64, 85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2007.08.005

Corley, K. G. (2015). A commentary on “what grounded theory is…”: engaging a phenomenon from the perspective of those living it. Organ. Res. Methods 18, 600–605. doi: 10.1177/1094428115574747

Crosnoe, R., and Muller, C. (2014). Family socioeconomic status, peers, and the path to college. Soc. Probl. 61, 602–624. doi: 10.1525/sp.2014.12255

DeFeo, D. J. (2013). Toward a model of purposeful participant inclusion: examining deselection as a participant risk. Qual. Res. J. 13, 253–264. doi: 10.1108/QRJ-01-2013-0007

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory: an introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Dills, A. K., and Mulholland, S. E. (2010). A comparative look at private and public schools class size determinants. Educ. Econ. 18, 435–454. doi: 10.1080/09645290903546397

Domina, T., McEachin, A., Hanselman, P., Agarwal, P., Hwang, N., and Lewis, R. W. (2019). Beyond tracking and detracking: the dimensions of organizational differentiation in schools. Sociol. Educ. 92, 293–322. doi: 10.1177/0038040719851879

Duckworth, A. L., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychol. Sci. 16, 939–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x

Dumont, H., Klinge, D., and Maaz, K. (2019). The many (subtle) ways parents game the system: mixed-method evidence on the transition into secondary-school tracks in Germany. Sociol. Educ. 92, 199–228. doi: 10.1177/0038040719838223

Dupriez, V., Dumay, X., and Vause, A. (2008). How do school systems manage pupils’ heterogeneity? Comp. Educ. Rev. 52, 245–273. doi: 10.1086/528764

Erikson, R., and Jonsson, J. O. (1996). Explaining class inequality in education: The Swedish test case. In Can education be equalized? The Swedish case in comparative perspective westview eds. R. Erikson and J. O. Jonsson. 1–63.

Erikson, R., and Rudolphi, F. (2010). Change in social selection to upper secondary school: primary and secondary effects in Sweden. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 26, 291–305. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcp022

Esser, H. (2016a). “The model of ability tracking: theoretical expectations and empirical findings on how educational systems impact on educational success and inequality” in Models of secondary education and social inequality. eds. H.-P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, J. Skopek, and M. Triventi (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 25–41.

Esser, H. (2016b). “Sorting and (much) more: prior ability, school effects and the impact of ability tracking on educational inequalities in achievement” in In education systems and inequalities. eds. A. Hadjar and C. Gross (Bristol: Policy Press), 95–114.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., and Hamilton, A. L. (2012). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 16, 15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151

Glaesser, J., and Cooper, B. (2011). Selectivity and flexibility in the German secondary school system: a configurational analysis of recent data from the German socio-economic panel. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 27, 570–585. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcq026

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Golann, J. W. (2018). Conformers, adaptors, imitators, and rejecters: how no-excuses teachers' cultural toolkits shape their responses to control. Sociol. Educ. 91, 28–45. doi: 10.1177/0038040717743721

Golash-Boza, T. (2016). A critical and comprehensive sociological theory of race and racism. Sociol. Race Ethnicity 2, 129–141. doi: 10.1177/2332649216632242

Grodsky, E., and Riegle-Crumb, C. (2010). Those who choose and those who don’t: social background and college orientation. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 627, 14–35. doi: 10.1177/0002716209348732

Gündemir, S., Carton, A. M., and Homan, A. C. (2019). The impact of organizational performance on the emergence of Asian American leaders. J. Appl. Psychol. 104, 107–122. doi: 10.1037/apl0000347

Hanushek, E. A., and Wößmann, L. (2006). Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries. Econ. J. 116, C63–C76. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x

Haussling, R. (2010). Allocation to social positions in class: interactions and relationships in first grade school classes and their consequences. Curr. Sociol. 58, 119–138. doi: 10.1177/0011392109349286

Hesse-Biber, S. N., and Leavy, P. L. (2011). The practice of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hughey, M. W., Embrick, D. G., and Doane, A. (2015). Paving the way for future race research: exploring the racial mechanisms within a color-blind, racialized social system. Am. Behav. Sci. 59, 1347–1357. doi: 10.1177/0002764215591033

Jackson, M. (2013a) in Determined to succeed? Performance versus choice in educational attainment. ed. M. Jackson (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press)

Jackson, M. (2013b). “How is inequality of educational opportunity generated? The case for primary and secondary effects” in Determined to succeed? Studies in social inequality. ed. M. Jackson (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press), 1–33.

Jackson, M., and Jonsson, J. O. (2013). “Why does inequality of educational opportunity vary across countries? Primary and secondary effects in comparative context” in Determined to succeed? Studies in social inequality. ed. M. Jackson (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press), 306–337.

Jackson, M., Jonsson, J. O., and Rudolphi, F. (2012). Ethnic inequality in choice-driven education systems: a longitudinal study of performance and choice in England and Sweden. Sociol. Educ. 85, 158–178. doi: 10.1177/0038040711427311

Jaeger, M. M. (2009). Equal access but unequal outcomes: cultural capital and educational choice in a meritocratic society. Soc. Forces 87, 1943–1971. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0192

Jennings, J. L., and DiPrete, T. A. (2010). Teacher effects on social and behavioral skills in early elementary school. Sociol. Educ. 83, 135–159. doi: 10.1177/0038040710368011

Kao, G., and Thompson, J. S. (2003). Racial and ethnic stratification in educational achievement and attainment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 29, 417–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100019

Kelly, S. P. (2008). “Social class and tracking within school. Pp. 210-224” in The way class works. ed. L. Weiss (London: Routledge), 210–224.

Kim, J., Chatterjee, S., and Cho, S. H. (2012). Asset ownership of new Asian immigrants in the United States. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 33, 215–226. doi: 10.1007/s10834-012-9317-0

Kim, J. H., and Torquati, J. (2019). Financial socialization of college students: domain-general and domain-specific perspectives. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 40, 226–236. doi: 10.1007/s10834-018-9590-7

Kroneberg, C., and Kalter, F. (2012). Rational choice theory and empirical research: methodological and theoretical contributions in Europe. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 38, 73–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145441

Lareau, A. (1987). Social class differences in family – school relationships: the importance of cultural capital. Sociol. Educ. 60, 73–85. doi: 10.2307/2112583

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Lareau, A., Evans, S. A., and Yee, A. (2016). The rules of the game and the uncertain transmission of advantage: middle-class parents’ search for an urban kindergarten. Sociol. Educ. 89, 279–299. doi: 10.1177/0038040716669568

Lareau, A., and Weininger, E. B. (2003). Cultural capital in educational research: a critical assessment. Theory Soc. 32, 567–606. doi: 10.1023/B:RYSO.0000004951.04408.b0

Lehmann, W. (2013). Habitus transformation and hidden injuries: successful working-class university students. Sociol. Educ. 87, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/0038040713498777

LeTendre, G. K., Hofer, B. K., and Shimizu, H. (2003). What is tracking? Cultural expectations in the United States, Germany, and Japan. Am. Educ. Res. J. 40, 43–89. doi: 10.3102/00028312040001043

Lewis, J. A., Mendenhall, R., Ojiemwen, A., Thomas, M., Riopelle, C., Harwood, S. A., et al. (2019). Racial microaggressions and sense of belonging at a historically white university. Am. Behav. Sci. 65, 1049–1071. doi: 10.1177/0002764219859613

Mayer, A., Lechasseur, K., and Donaldson, M. (2018). The structure of tracking: instructional practices of teachers leading low-and high-track classes. Am. J. Educ. 124, 445–477. doi: 10.1086/698453

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Montt, G. (2011). Cross-national differences in educational achievement inequality. Sociol. Educ. 84, 49–68. doi: 10.1177/0038040710392717

Moore, W. L., and Bell, J. M. (2011). Maneuvers of whiteness: “diversity” as a mechanism of retrenchment in the affirmative action discourse. Crit. Sociol. 37, 597–613. doi: 10.1177/0896920510380066

Morgan, S. L. (2012). Models of college entry in the United States and the challenges of estimating primary and secondary effects. Sociol. Methods Res. 41, 17–56. doi: 10.1177/0049124112440797

Ng, J., Lee, S. S., and Pak, Y. K. (2007). Contesting the model minority and perpetual foreigner stereotypes: a critical review of literature on Asian Americans in education. Rev. Res. Educ. 31, 95–130. doi: 10.3102/0091732X07300046095

Nikolai, R., and West, A. (2013). “School type and inequality” in Contemporary debates in the sociology of education. eds. R. Brooks, M. McCormack, and K. Bhopal (London: Palgrave MacMillan), 57–75.

Pfeffer, F. T. (2008). Persistent inequality in educational attainment and its institutional context. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 24, 543–565. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcn026

Pierce, C. (1970). “Offensive Mechanisms” in The black seventies. ed. F. Barbour (Brooklyn, NY: Porter Sargent), 265–282.

Purkayastha, B. (2005). Negotiating ethnicity: Second-generation south Asian Americans traverse in a transnational world. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Schindler, S., and Lörz, M. (2012). Mechanisms of social inequality development: primary and secondary effects in the transition to tertiary education between 1976 and 2005. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 28, 647–660. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr032

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., and Ohlendorf, G. O. (1970). The educational and early occupational status attainment process: replication and revision. Am. Sociol. Rev. 35, 1014–1027. doi: 10.2307/2093379

Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., and Portes, A. (1969). The educational and early occupational attainment process. Am. Sociol. Rev. 34, 82–92. doi: 10.2307/2092789

Sewell, W. H., Hauser, R. M., Springer, K. W., and Hauser, T. S. (2003). As we age: a review of the Wisconsin longitudinal study, 1957-2001. Res. Soc. Stratificat. Mobil. 20, 3–111. doi: 10.1016/S0276-5624(03)20001-9

Singh, K., Bickley, P. G., Trivette, P., Keith, T. Z., Keith, P. B., and Anderson, E. (1995). The effects of four components of parental involvement on eighth-grade student achievement: structural analysis of NELS-88 data. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 24, 299–317. doi: 10.1080/02796015.1995.12085769

Stocké, V. (2007). Explaining educational decision and effects of families’ social class position: an empirical test of the Breen Goldthorpe model of educational attainment. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 23, 505–519. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcm014

Streib, J. (2011). Class reproduction by four year olds. Qual. Sociol. 34, 337–152. doi: 10.1007/s11133-011-9193-1

Sue, D. W., Bucceri, J. M., Lin, A. I., Nadal, K. L., and Torino, G. C. (2007a). Racial microaggressions and the Asian American experience. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 13, 72–81. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.72

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., and Holder, A. M. B. (2008). Racial microaggressions in the life experience of black Americans. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 39, 329–336. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.329

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., et al. (2007b). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am. Psychol. 62, 271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Suizzo, M.-A., and Stapleton, L. M. (2007). Home-based parental involvement in young children’s education: examining the effects of maternal education across U.S. ethnic groups. Educ. Psychol. 27, 533–556. doi: 10.1080/01443410601159936

Umansky, I. M. (2016). Leveled and exclusionary tracking: English learners’ access to academic content in middle school. Am. Educ. Res. J. 53, 1792–1833. doi: 10.3102/0002831216675404

Useem, E. L. (1991). Student selection into course sequences in mathematics: the impact of parental involvement and school policies. J. Res. Adolesc. 1, 231–250. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0103_3

Useem, E. L. (1992). Middle schools and math groups: parents’ involvement in children’s placement. Sociol. Educ. 65, 263–279. doi: 10.2307/2112770

Van de Werfhorst, H. G., and Mijs, J. J. B. (2010). Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: a comparative perspective. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 36, 407–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102538

Walsh, I., Holton, J. A., Bailyn, L., Fernandez, W., Levina, N., and Glaser, B. (2015). What grounded theory is…a critically reflective conversation among scholars. Organ. Res. Methods 18, 581–599. doi: 10.1177/1094428114565028

Wilcox, K. (1982). “Differential socialization in the classroom: implications for equal opportunity” in Doing the ethnography of schooling: educational anthropology in action. ed. G. Spindler (Austin, TX: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston), 268–309.

Keywords: tracking, educational inequality, Asian Indians, microaggression, qualitative methods

Citation: Banerjee D and Bhattacharya AD (2023) Tracking-related experiences of second-generation Asian Indian students in the USA. Front. Educ. 8:1183462. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1183462

Edited by:

Anabel Corral-Granados, NTNU, NorwayReviewed by:

Antonio Martín-Ezpeleta, University of Valencia, SpainYolanda Echegoyen-Sanz, University of Valencia, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Banerjee and Bhattacharya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dina Banerjee, ZGluYS5iYW5lcmplZUBpaW11LmFjLmlu

Dina Banerjee

Dina Banerjee Akshaj Dev Bhattacharya2

Akshaj Dev Bhattacharya2