95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 31 October 2023

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1179865

This article is part of the Research Topic Educational Approaches for Promoting Neurodivergent Health, Well-Being, and Thriving Across the Life Course View all 9 articles

Hilary Nelson1

Hilary Nelson1 Danielle Switalsky1

Danielle Switalsky1 Jill Ciesielski1

Jill Ciesielski1 Heather M. Brown2

Heather M. Brown2 Jackie Ryan2

Jackie Ryan2 Margot Stothers2

Margot Stothers2 Emily Coombs1

Emily Coombs1 Alessandra Crerear3

Alessandra Crerear3 Christina Devlin3

Christina Devlin3 Chris Bendevis3

Chris Bendevis3 Tommias Ksiazek3

Tommias Ksiazek3 Patrick Dwyer4

Patrick Dwyer4 Chelsea Hack1

Chelsea Hack1 Tara Connolly5

Tara Connolly5 David B. Nicholas1

David B. Nicholas1 Briano DiRezze6*

Briano DiRezze6*Given the demand to better address the principles of equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in higher education, research into both barriers and promising practices to support autistic students on post-secondary campuses has advanced significantly in the last decade. The objective of this scoping review is to identify, map, and characterize literature that enumerates and describes supports for autistic post-secondary students. This scoping review was limited to peer-reviewed research published between January 2012 and May 2022, in these databases: Web of Science, PsycINFO, Medline, EMBASE, ERIC, Social Work Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, and EMCARE. The review aligns to Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews and includes consultation with an expert panel made up of the Autistic Community Partners–four autistic individuals with postsecondary experience who acted as co-researchers. Literature on creating accessible campuses were mapped in three ways: (1) through the four domains of the PASS Taxonomy; (2) ten support categories characterizing types of supports, and (3) nine emergent themes, based on autistic experiences on support and campus navigation, were inductively and iteratively coded throughout process. This review summarizes both areas that have been researched and under-studied areas in the literature that act as contributors or challenges for autistic students on postsecondary campuses. It was also the first scoping review, to our knowledge, to integrate lived experience within the methods and results analysis to describe the current state of the evidence on post-secondary campuses. Mapping the literature in known and emerging categories indicated that broad categories of support are experienced variably by autistic students. Findings provide multiple avenues for future research.

There is growing recognition of the need for equitable access to post-secondary (PS) education and inclusive campuses for autistic students. Increasing enrollment rates of autistic students have been noted by PS institutions (Shattuck et al., 2012; Barnhill, 2016) and are anticipated to grow (Kuder and Accardo, 2018). While exact enrollment rates are unknown and dependent on disclosure, it is estimated that up to 2 % of PS populations may be autistic based on known prevalence rates (Ward and Webster, 2018; White et al., 2019). On campuses, there are many areas where autistic students may benefit from supports to create equitable access and benefit from PS education. Despite growing admittance of autistic students to PS institutions and a sense of academic preparedness (Flegenheimer and Scherf, 2022), Newman et al. (2011) indicated lower completion rates for autistic students (38.8%) in comparison to general PS population (52%) in the United States. A more recent study in the Netherlands, examining predictors of academic success, found that while completion and dropout rates of autistic and control students did not significantly differ, autistic students are slower to accumulate degree credits (Bakker et al., 2022). Particularly in the last decade, there has been increased literature identifying challenges and strategies to supporting autistic students on PS campuses, as well as noting the limited implementation of autism-specific supports in PS institutions.

Most existing scoping and systematic literature reviews have focused on studies examining supports for or experiences of autistic PS students within a specific context or scope (Gelbar et al., 2014; Dallas et al., 2015; Anderson et al., 2017; Kuder and Accardo, 2018; Anderson A. H. et al., 2019; Widman and Lopez-Reyna, 2020; Cox et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021). Gelbar et al. (2014) focused on the firsthand experiences of autistic students in the United States. Widman and Lopez-Reyna (2020) reviewed 21 studies focusing on supports for autistic students on PS campuses in the United States, through which they developed a classification for autism supports. Ames et al. (2022) mapped the availability of autism-specific supports on Canadian PS campuses. Kuder and Accardo (2018) [8 included studies] and Anderson A. H. et al. (2019) [24 included studies] conducted international systematic reviews examining studies addressing outcomes of programs and interventions that support autistic PS students. In a systematic review of 24 studies, Davis et al. (2021) examined academic and non-academic supports for autistic PS students through first-hand descriptions by autistic students, prioritizing autistic lived experiences on an international scale. Where international literature was considered, the vast majority of articles come from the United States, with limited studies originating from Australia, United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Israel and Japan where noted (Anderson et al., 2017; Anderson A. H. et al., 2019; Cox et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021). These reviews reported in the literature provide a significant foundation from which to begin to understand the experiences of autistic students on PS campuses. However, their foci and aims are inconsistent; to our knowledge, only Cox et al. (2021) endeavored to review a wide range of autism postsecondary literature, and they only examined studies published before 2015. Given the rapid growth of subsequent research on autistic people’s postsecondary experiences, a broader sense of the international literature on autism supports in post-secondary education is currently missing.

Due to the expansive scope of considerations impacting autistic lived experience and structuring meaningful change on campus, as well as the need to examine the international literature, a scoping review was conducted to capture the literature holistically. This approach is ideal for mapping the existing peer-reviewed international literature to integrate autistic perspectives on supports to help frame future efforts to build capacity on PS campuses. Although there are differences in PS institutions across countries, examining innovative approaches to equity and access on campuses internationally can offer guidance by identifying best practices globally to improve the success of autistic PS students.

This scoping review aimed to map the current international peer-reviewed literature exploring post-secondary supports for autistic PS students and identify existing contributors and challenges of these supports on PS campuses. A secondary objective was to integrate the perspectives of autistic students into mapping post-secondary supports. This review of the literature sought to holistically explore factors impacting autistic students’ experiences on PS campuses. To support these objectives, two research questions were proposed.

1. Within the international peer-reviewed literature, what are the existing aims and approaches to supporting autistic post-secondary students, as well as the contributors and challenges to their implementation?

2. From the perspective of autistic post-secondary students, what are the emerging areas of support on post-secondary campuses to map and explore novel areas of need for current and future research?

This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2022). This review incorporates the optional involvement of an expert panel in scoping review methodologies (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010; Scott et al., 2019; Pollock et al., 2022) and was completed in consultation with the ‘Autistic Community Partners’ (ACP), an expert panel of self-advocates. The ACP comprised 4 autistic adults with lived experience in PS education (AC, CD, CB, and TK), in addition to autistic members of the research team (HB, JR, MS, EC, and PD). These partners reviewed and approved the methodology and research directions. The purpose of this consultation was to integrate lived autistic experiences in PS into the development of the research aims and methodology. The role of the ACP and incorporation of ACP feedback have been noted throughout the paper; in particular, in methodology design and process sections.

The scoping review process has been recorded based on the suggested methods from the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018). For clarity, the methodology design and process are detailed below to overview the search strategy, eligibility criteria for articles, the process of study selection, and steps of mapping and extracting data from the selected studies.

Initial development of the search strategy was an iterative process completed in consultation with a Health Sciences librarian. A preliminary search on the topic was conducted to identify articles of relevance, which were subsequently used to inform the development of keywords and index terms to create a search strategy. The complete search strategy was adapted for each information source and a search was completed on May 27, 2022, in the following databases: Web of Science (Clarivate), APA PsycINFO (Ovid), Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), ERIC (EBSCO), Social Work Abstracts (EBSCO), Social Services Abstracts (ProQuest) and Emcare (Ovid). All studies published internationally in English between January 1, 2012, and May 26, 2022, were included to generate an understanding of current literature and emerging trends within the autism and PS fields. Due to continually increasing knowledge on neurodiversity, literature published before this 10-year period was determined to likely not reflect current best practices or adequately inform the direction of future research and was excluded from this review. The full search strategy is included in Appendix 1.

All literature addressing supports for autistic students at PS institutions was considered in this review. Due to the variability of terms used, defining key terminology was prudent for structuring eligibility criteria for inclusion. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used.

Literature denotes peer-reviewed publications of all types of original research using a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method design. Accordingly, reviews, abstracts, editorials, letters, commentaries, theses, conference proceedings and gray literature were excluded. Single subject designs were included. PS institutions were broadly defined to account for language variations used for PS education internationally, such as universities, colleges, tertiary institutions, and higher education. Vocational or trade colleges, polytechnic institutes and non-matriculating programs were excluded from this review. The term autistic individual encompasses persons who identify on the autism spectrum, which includes many potential identifiers such as autistic, ASD, Asperger’s, or identified through use of umbrella search terms, such as neurodivergent. A PS student is identified as an individual who has completed secondary school and is enrolled in higher-level education or, if reported retrospectively, had been enrolled.

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, 2022), and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening and full-text reviews were undertaken by two independent reviewers (HN and DS). A 5% (n = 22) sample of titles and abstracts were double-screened by both reviewers using the agreed upon inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Discrepancies were resolved through consensus, and in cases of conflict, additional discussion with a third independent reviewer yielded resolution (BDR). Once consensus between reviewers was reached, the remainder (n = 5,487) of the titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (HN, DS). Full-text reviews (n = 550) were conducted independently by two reviewers (HN, DS), with discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (BDR).

Basic demographic data were collected on each article to capture potentially relevant contextual details or trends. Noted information included the year of publication, disclosed funding information and country of origin. Data collected about the study included design and sample size, as well as whether participants had a formal diagnosis for autistic participants, the autistic voice was present within the research team (or participants only), and inclusion of demographic details on participants (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender distribution and age range).

Building from developed classifications for categorizing literature and consultation with the ACP, a data coding framework was developed. Each study in the review were classified in three different ways: the four PASS domains; 10 support categories characterizing types of supports; and nine emergent themes. Further detail on the process of development, and final coding framework is described below.

The PASS taxonomy developed by Dukes et al. (2017), was designed to organize literature addressing PS education for students with disabilities to identify the focus of the research being conducted. The four PASS domains are (1) program and institutional-focused support (e.g., the development or change of policies or infrastructural design), (2) faculty and staff-focused support, (3) student-focused support, and (4) concept and systems development (e.g., work informing or trialing supports) (Dukes et al., 2017).

Widman and Lopez-Reyna (2020) classified eight main types of supports typically offered to autistic PS students in PS institutions, namely: (1) social learning (e.g., relationship building), (2) functional life skills/residential skills (e.g., day-to-day management), (3) academic, (4) emotional learning (e.g., coping and mental health), (5) vocational training, (6) communication development (e.g., general communication strategies), (7) transition needs, and parent/family involvement. After review and consultation with the ACP, the category of parent and family involvement was expanded to capture any mention of (8) support external to the PS campus. Based on the ACP’s identification of (9) financial supports, and (10) sexual health and education supports as support types that were indicated to be important, these two categories were added for coding for a total of 10 Support Categories. Further feedback provided by the ACP on the Support Categories emphasized the importance of capturing the experiential and potentially consistent or possibly opposing insights of individual autistic students. As a result, the categories were further coded in a binary way, describing supports from the studies as having characteristics as a contributor of support (or beneficial support) and/or challenges (or barriers) to support to capture the range of experiences and outcomes as described in the literature.

Based on initial feedback by the ACP identifying elements informing autistic experiences on post-secondary campuses that were not captured by the Support Categories, an ‘other’ category was introduced to capture emergent themes underlying campus experiences and navigation of supports during our initial classification of the studies according to the PASS domains and the Support Categories. Examples of elements suggested by the ACP included challenges relating to obtaining diagnosis, the impact that negative or uninformed attitudes had on student experiences, and the impact of having multiple identities (intersectionality).

After initial coding, we reviewed the notes from the ‘other’ category to identify emerging themes, or similar concepts, reoccurring as contributors or challenges for Autistic post-secondary students across types of support categories. Building from the themes identified in the initial review, we then manually cross-referenced the emergent themes against all coding undertaken in Support Categories to identify any similar or distinguishing concepts for consistency. All emergent themes were cross-referenced against the original text before inclusion Finally, the themes were organized and characterized into a final list of nine additional themes which we described as: (1) interpersonal; (2) individualized, (3) sensory environments, (4) attitudinal, (5) service navigation, (6) diagnosis, (7) disclosure, (8) identity management, and (9) intersectionality. These will be addressed in greater detail in the results.

The data mapping and extraction of each phase of our classification framework was trialed by two graduate-level research assistants (HN and DS) on 10 studies to optimize consistency and identification of relevant data. Subsequently, all included studies were screened independently and coded by three reviewers (HN, DS, and JC), all completing their Master’s degrees.

The search yielded a total of 8,518 articles which were uploaded to Covidence for screening. Duplicates were removed (n = 2,659), and 5,498 studies underwent title and abstract screening. Of those, 4,898 were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria The remaining 556 articles were assessed for eligibility through full-text review, and a further 400 studies were excluded (see Figure 1). Reasons for exclusion included: featuring the wrong setting (i.e., vocational or community college) or population (i.e., neurodiversity other than autism or high school students), and ineligible sources such as dissertations and conference proceedings. In total, 156 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review. A summary of the inclusion process can be seen in Figure 1: PRISMA-SCR Chart.

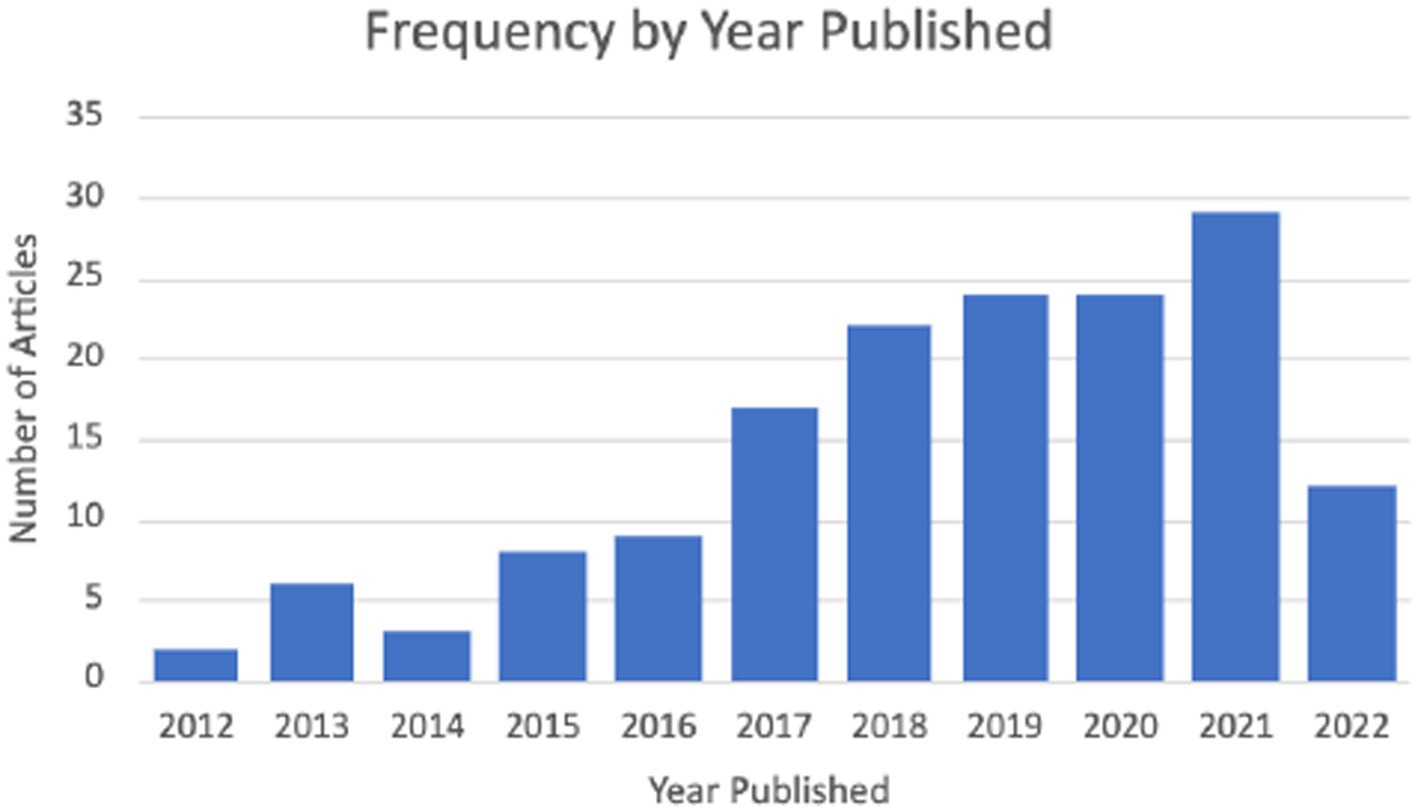

Basic demographic data were collected on each article to represent the country of published data and the year of publication. The characteristics of included studies were summarized. Over half (58%) of included studies were from the United States (n = 90). Articles from the United Kingdom (n = 19), Australia (n = 12), Canada (n = 8) and including multiple countries (n = 13), made up another significant portion of the sample. Several other countries were represented in 3 or fewer studies, such as the Netherlands and Israel (n = 3), Sweden and Belgium (n = 2), and Ireland, Norway, Nigeria, and Slovenia (each with n = 1); see Figure 2. A frequency count of the publication date of selected studies (2012–2022) indicates an upwards trend in articles focusing on autistic students on PS campuses, see Figure 3. Notably, the count for articles published in 2022 is inclusive up to May 26, 2022.

Figure 3. Year of publication of included studies* (*2022 statistics only capture from Jan 2022–May 2022).

To explore research trends in the literature, we used the four PASS domains (Dukes et al., 2017) to classify every study in our review according to the categories of institutional assistance that each study explored in relation to supporting autistic PS students. First, the majority of articles (n = 114; 73.0%) explored institutional supports offered to autistic students themselves (PASS Domain 3). In comparison, one-quarter of the studies (n = 40, 25.6%) examined institutional supports aimed at faculty, family, and/or peers to improve the experiences of Autistic PS students (PASS Domain 2). Of these, 50% of the studies explored institutional supports directed at faculty and staff members (n = 20), 30% directed at peers (n = 12), and 12.5% toward families (n = 5). Only 20 studies (13.8%) included any focus on the development or change of policies to better support Autistic PS students from the institution-level structural perspective (PASS Domain 1), while 44 studies (28.2%) included a focus on the development of concepts and/or included a type of intervention related to supports provided (PASS Domain 4). It is also important to note that many of the studies (n = 55, 35.2%) fell under more than one PASS domain. Table 1 summarizes the types of institutional supports given to autistic PS students for each of the PASS domains.

While inclusion of autistic perspectives is present in literature (n = 114), the most prevalent representation is limited to study participation only (n = 96, 84.2%) rather than involvement in research leadership or consultation roles. However, 11 studies used co-design and consultation with autistic individuals, including five articles that use participatory research processes. Additionally, seven articles included self-identified autistic authors or members of the research team.

In articles using autistic participants as their study population (n = 114), only 97 articles (85%) reported the gender breakdown of their sample. Out of the 97 articles, 48 studies had populations that were more than 50% male and only 23 studies (24%) were inclusive of gender diversity by reporting that the sample included gender identities other than men or women. Of articles identifying autistic participants, only 51 articles reported the racial or ethnic breakdown of their sample. Table 2 summarizes the findings regarding inclusion of autistic population in the research design of studies included in our review.

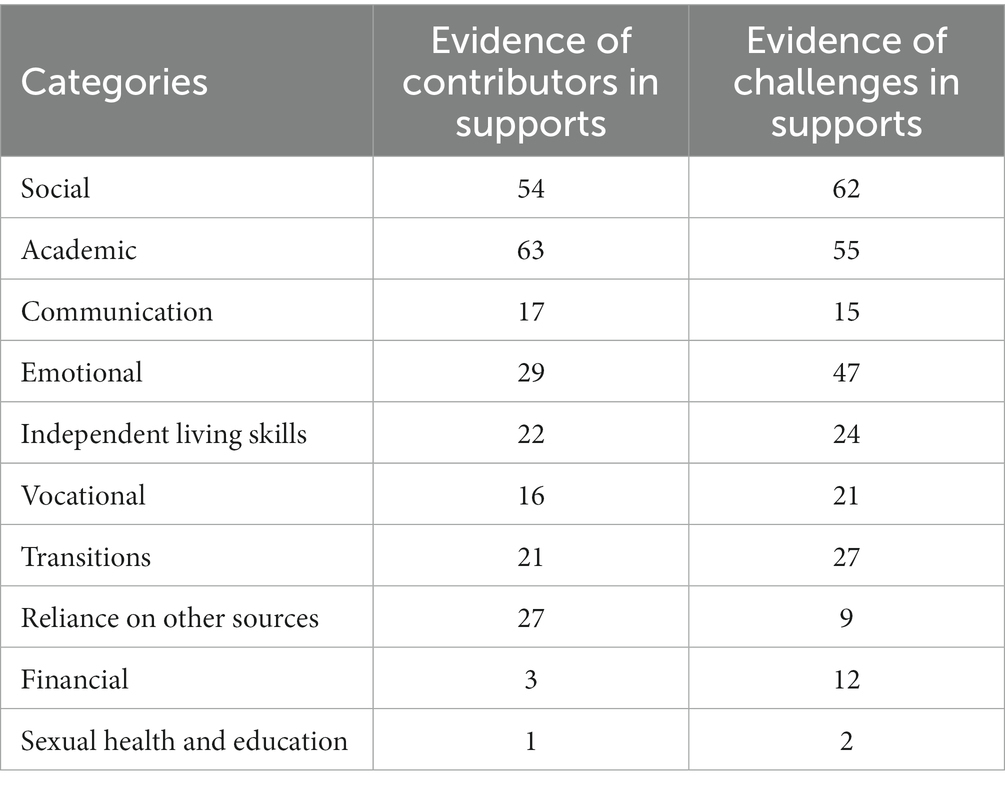

Consultation with the ACP confirmed the eight categories suggested by Widman and Lopez-Reyna (2020) and suggested an additional two for a total of 10 categories for types of support. For each category, frequency counts were reported for studies identifying contributors versus challenges with PS supports (see Table 3). Studies may have identified both contributors and challenges for a single category or may not have addressed that particular category explicitly. Due to an ecological understanding of supports, studies were counted by the primary focus of the article (e.g., social, coping or self-advocacy discussed for the purpose of providing academic support would be counted as academic). Articles may be counted in multiple categories of support if there was more than one stated purpose. Categorization was designed to highlight the primary purposes or objective underlying provided supports.

Table 3. Frequency of types of support categories in included studies as contributors or challenges for support on PS campus.

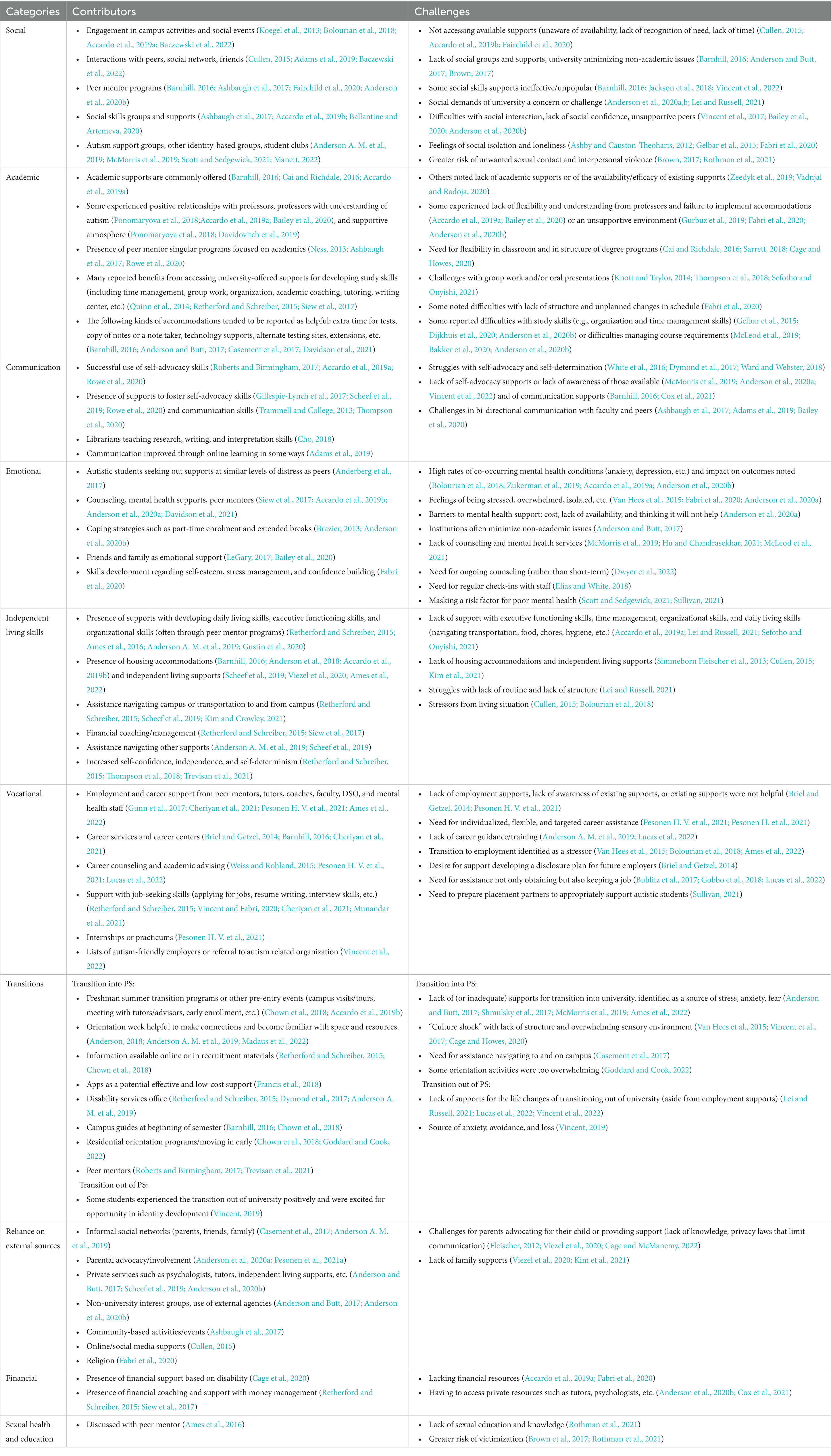

Details provided on supports were classified as contributors or challenges based on the presence of supports available on PS campuses and by the outcomes of the supports as identified in the literature by autistic individuals. The frequency count indicates the number of articles addressing the type of support, and does not indicate if an article identified multiple contributors or challenges pertaining to that support category. The most common characteristics and findings for the contributors and challenges of each support category, with example articles included for reference, are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Categories of support types for included studies based on focus of support as a contributor and/or challenge for autistics on PS campus.

Due to the ecological nature of autism supports, it is recognized that there a lack of clear division between all categories of support. This necessitated a secondary analysis of contributors and challenges in implementing supports (see Emergent Themes). The frequency counts for support categories are included to provide a broad overview of investigation foci and characterization in the literature.

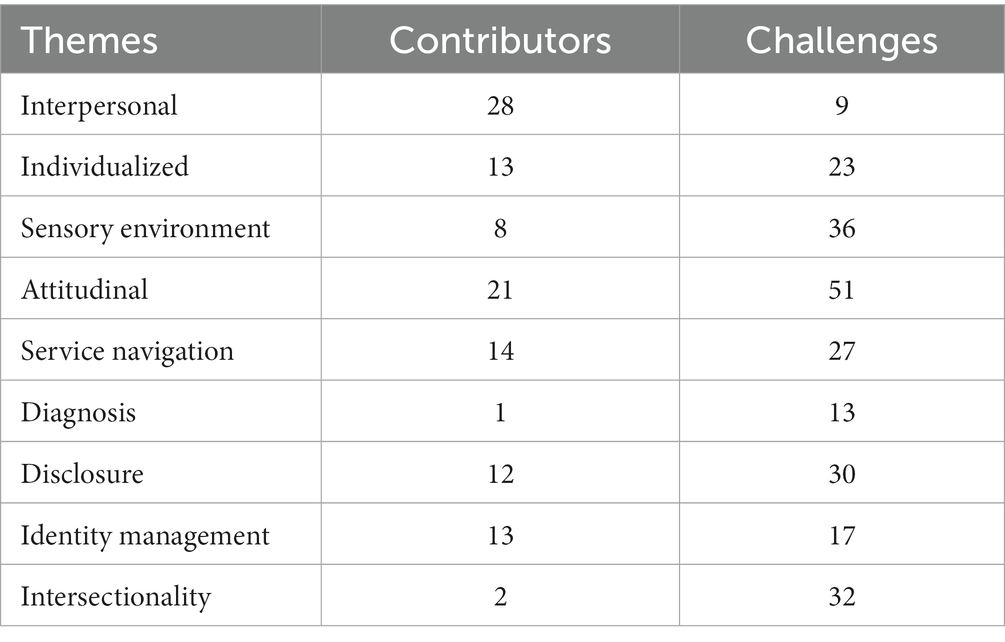

Nine emerging themes discussing the role and impact of the following on autistic students were identified, namely: interpersonal connections, individualized supports, the sensory environment, attitudinal impacts, factors impacting service navigation of available supports, diagnosis requirements, disclosure decisions, role of identity management, and the impact of intersectionality. The distinction between the support categories and the support themes is a respective focus on the purpose of supports versus factors influencing the effectiveness of supports. The themes are a secondary analysis of the contributors and challenges identified across the categories of support. A frequency count was also conducted for these themes (see Table 5), following the same process as with the other categories. The emergent areas of support themes are summarized in Table 6, and capture factors that, from perspectives of autistic PS students available in the literature, can become contributors or challenges when navigating campus supports.

Table 5. Frequencies of emergent areas of support themes in included studies as contributors or challenges for support on PS campus.

This scoping review summarizes the breadth of research conducted on supports for and the experiences of autistic students on PS: campuses. As evident in the results of the 156 international studies identified in this review, approaches to supporting autistic students were categorized into 10 categories of support, and where provided support must be integrative and respect the individuality of autistic students. While the presence of supports indicates progress on PS campuses, 9 emerging areas of focus were identified from the autistic perspectives in this work.

The literature highlights where the research has been focused relative to the 10 identified support categories. Our elicitation of the experiences of autistic PS students amplifies where supports/lack of supports have contributed to success or challenge. The social and academic categories had the greatest number of studies focused on support contributors, while those with the lowest frequency of support contributors were communication, vocational, financial, and sexual health. Support categories with the greatest noted challenges were social and academic. In contrast, those with the lowest frequency of studies reporting challenges were communication, reliance on other sources, and financial and sexual health. The low representation of studies addressing financial supports and sexual health in the literature is noteworthy, particularly due to the identification of these as areas of importance by autistic members of our expert panel. Most of the categories had a higher frequency count of challenge (negative) than contributor (positive) indicators, except academic, communication, and reliance on other sources.

Academic accommodations, typically accessed through offices for students with disabilities, have been the most frequently studied form of supports for autistic students (Brown, 2017; Ames et al., 2022). Unsurprisingly, this was the category with the highest frequency count for contributory indicators. Likewise, it is possible that communication supports were cited less frequently as a challenge due to the lower emphasis placed on a need for communication supports in the literature. A low frequency of communication supports, despite common needs among autistic students, aligns with previous reviews (Widman and Lopez-Reyna, 2020; Pennington et al., 2021). Concerning reliance on other sources, the presence of supports outside the university, while often positive for the individual student, can indicate a lack of resources available within the university that is not explicitly stated within articles. For example, some students reported accessing private services (e.g., psychologist, tutor) outside of the university (Anderson and Butt, 2017; Scheef et al., 2019; Anderson et al., 2020b).

Significant overlaps between broad categories of supports were identified in this review. When this occurred, studies were categorized based on which support outcome was stated to be primary. Byrne (2022) identified a significant overlap between social, academic, and communication supports in connection with transitioning to employment. The interconnectivity between categories of support challenges the demarcation of types of support and rather suggests the need for both a granular and holistic perspective that recognizes the integrative nature of PS education and the PS ecosystem. The disproportionate representation of challenges to, over contributors to support, amplifies the ongoing call for proactive and effective supports for autistic students on PS campuses.

While demarcating categories of supports is useful to map where the research focus is being directed in the literature and identify where student support needs are not being examined, underlying those categories are connecting themes that highlight autistic students’ experiences of PS education. The nine emerging areas of focus identified from this work were interpersonal connections, individualized supports, the sensory environment, attitudinal impacts, factors impacting the navigation of available services and supports, diagnosis requirements, disclosure decisions, identity development and management, and the impact of intersectionality. It is suggested that these themes are useful to integrate into existing support categories for autistic students on PS campuses to drive research and services on campuses. This review contributes to the findings of previous synthesis-type reviews by connecting the narratives about autistic students’ experiences navigating PS education generally and in connection to supports (Gelbar et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2017; Cashin, 2018; Kuder and Accardo, 2018; Anderson A. H. et al., 2019; Clouder et al., 2020; Nachman, 2020; Widman and Lopez-Reyna, 2020; Cox et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Duerksen et al., 2021; Kuder et al., 2021; Pennington et al., 2021). This holistic perspective leads to the ability to summarize the interconnections between the known complexities to highlight knowledge gaps and situate where further research can advocate for systemic changes to improve the PS experiences of autistic students.

The availability of supports and services, and process required for accessing, is identified as a key and persisting challenge to the efficacy of supports from the perspective of autistic students. These barriers are present at every stage of the process from obtaining and ‘proving’ a diagnosis, disclosing identity, and navigating the existing services. The complications represented within this process only pertain to existent supports, and do not fully capture additional complications arising from the absence of appropriate supports. These nine emerging themes from this scoping review highlight key areas to further study and implement innovative ways to address these needs.

The process of accessing services is complicated by barriers to accessing an autism diagnosis, consistent with many studies that demonstrate that students can be unaware of their autism and/or unable to access the formal diagnosis necessary for support services due to cost or time delay (Accardo et al., 2019a,b; Cage et al., 2020; Viezel et al., 2020). Disclosure as a barrier to support has been noted previously (Anderson A. H. et al., 2019; Anderson A. M. et al., 2019; Zeedyk et al., 2019; Cox et al., 2020; Fabri et al., 2020), with several articles noting that self-disclosure was an essential first step to accessing supports and accommodations in PS institutions (Nuske et al., 2019; Von Below et al., 2021). Disclosure is inherently interconnected with navigating personal identity and the surrounding attitudinal environment to assess such disclosure’s potential risks and benefits (Clouder et al., 2020). While the disclosure is technically a choice, the current reliance on disclosure to access formal or informal supports means that, for many students, that choice becomes illusory as there is little viable option beyond disclosure (Van Hees et al., 2015; Clouder et al., 2020).

While disclosure occurs at the individual level, it is done within the relational and environmental context. Fear of stigmatization is commonly reported in studies, where autistic students may hide or not disclose their identity to others on campus due to fear of negative reactions (Casement et al., 2017; MacLeod et al., 2018; Sarrett, 2018; Frost et al., 2019; Goddard and Cook, 2022). Casagrande et al. (2020) identify a need for initatives to improve the campus climate to increase a sense of belonging for autistic students. Additionally, the attitudinal environment has been identified as a key aspect for support efficacy, with positive attitudes leading to successful supports (Austin and Peña, 2017) and negative attitudes, misinformation or lack of knowledge leading to the breakdown of supports (Ashby and Causton-Theoharis, 2012; Hassenfeldt et al., 2019; Bailey et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2020b). Some emergent research has focused on how to destigmatize autism within the broader PS campus through preliminary initiatives focused on university faculty, staff and peers (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2015; Cai and Richdale, 2016; Davidovitch et al., 2019; Anderson, 2021; Bolourian et al., 2021; Dickter and Burk, 2021; Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2021; White et al., 2021), with varying results. A common thread in the literature is a need for greater understanding and acceptance of autism in the PS campus environment generally and in connection to its direct impact of the efficacy of supports.

Service navigation generally is a noted challenge, with studies pointing to issues with communication transparency on available services (Accardo et al., 2019b; Viezel et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2020b; Ames et al., 2022), siloed or rigid services (Nuske et al., 2019; Kuder et al., 2021), and the requisite of sufficient and/or trained staffing to meet needs (Fleischer, 2012; Glennon, 2016; Cox et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021). One example approach toward addressing the challenge of identifying and navigating existent supports is to utilize an intermediary assigned to each individual student as a ‘coordinator’ to act as support in navigating services (McMorris et al., 2019; Thompson et al., 2019; Dwyer et al., 2022) with some studies implementing this recommendation (Madaus et al., 2022). Formal and informal collaborative relationships with autistic students and between services have been identified as having a bridging effect to better support students in navigating services (Knott and Taylor, 2014; Hamilton et al., 2016; Casement et al., 2017; Cho, 2018; Thompson et al., 2018, 2020; Hu and Chandrasekhar, 2021).

There has been an increasing recognition in the literature of the need for individualized supports (Cashin, 2018; Kuder and Accardo, 2018; Anderson A. H. et al., 2019; Clouder et al., 2020; Nachman, 2020; Duerksen et al., 2021), and this review adds to that call. This need for individualized supports encompasses both the need to consider the individual and the need for autism-specific supports (Nachman, 2020). The process of individualizing supports is recognized to be challenging due to the diversity of autistic individuals, and the necessary recognition that supports can have opposing outcomes based on individual needs and preferences (Kuder and Accardo, 2018; Anderson A. M. et al., 2019). Underlying the call for individualized supports is the need for greater flexibility in the design, availability, and provision of supports. Early strategies and suggestions on individualizing supports highlight the important role of interpersonal connections. Beyond individualization, universal design that supports diversities on campus could significantly contribute to less stigmatizing and impeding challenges for students.

Interpersonal connection was noted as having the capacity to meet socioemotional and academic needs (Duerksen et al., 2021), and to facilitate navigation of disconnected services (Clouder et al., 2020). Often, a positive and collaborative interpersonal connection was highlighted in the literature as a successful strategy to encourage both formal and informal supports to better meet students’ individual needs (Ness, 2013; Ames et al., 2016; Austin and Peña, 2017; LeGary, 2017; Roberts and Birmingham, 2017; Cho, 2018; Everhart and Escobar, 2018; Lucas and James, 2018; Thompson et al., 2018, 2020; Anderson A. M. et al., 2019; Pionke et al., 2019; Accardo et al., 2019a; Bailey et al., 2020; Anderson, 2021; Cox et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; Lucas et al., 2022). Over time, positive quality of contact helps to engender a sense of trust to build a generative and helpful relationship (Everhart and Escobar, 2018; Pionke et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021; Kim, 2022). On the other hand, a history of negative interactions and an absence of positive interpersonal relationships yields a sense of distrust, which contributes to the personal choice of whether to disclose one’s diagnosis, the potential breakdown of services (Kim et al., 2021), and students falling through the cracks (Cox et al., 2021).

Peer mentoring programs seek to optimize the benefits of an interpersonal connection, and outcomes underline the importance of genuine connection (Ness, 2013; Roberts and Birmingham, 2017; Lucas and James, 2018; Thompson et al., 2018, 2020; Todd et al., 2019). Programs have had success with matching students through shared interests (Thompson et al., 2018) or shared experiences (Lucas and James, 2018; Todd et al., 2019), and yet, as highlighted by Anderson A. H. et al. (2019), there can be diametrically opposing outcomes based on individual preference and sense of connection. The literature points to the need for caution in terms of interpersonal connections without sufficient infrastructure for resources as connection alone is not a substitute for adequate supports (Thompson et al., 2021).

The literature points to two primary areas where there are persisting gaps in types of supports for autistic students: sensory environment accommodations (Ashby and Causton-Theoharis, 2012; Knott and Taylor, 2014; Van Hees et al., 2015; Barnhill, 2016; Cai and Richdale, 2016; Yager, 2016; Brown et al., 2017; Casement et al., 2017; Vincent et al., 2017; Thompson et al., 2018, 2019; Ward and Webster, 2018; Gurbuz et al., 2019; Cage et al., 2020; Grabsch et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; Scott and Sedgewick, 2021; Sullivan, 2021; Dwyer et al., 2022; Goddard and Cook, 2022) and financial supports (Accardo et al., 2019a; Fabri et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2020b; Cox et al., 2021). The identification of these two areas is not unique to this review. Previous reviews have identified the need for sensory accommodations that implicate changes to the physical environment (Anderson A. H. et al., 2019), the need for access to funding generally (Clouder et al., 2020) and flexible funding arrangements (Cashin, 2018). Both types of supports indicate a general lack of infrastructural consideration given to the unique needs of autistic students regarding the energy, resources and time commitments required to successfully navigate and access the benefits of PS education that is more readily afforded to other students. The struggle of navigating a space not designed to be inclusive of their needs means that many autistic students may struggle to feel a sense of belonging on PS campuses.

Understanding differential individual experiences on PS campuses is key to identifying how to facilitate individualized services and foster interpersonal connections. The foregoing categories rely on situating autistic students as individuals within PS campus environments. However, autistic individuals themselves are still underrepresented in the literature (Nachman, 2020; Cox et al., 2021), both as producers of knowledge and exploring the unique experiences of navigating barriers. Intersectionality, and the impact of multiple, intersectional identities outside of co-occurring mental health concerns, remain conspicuously under-discussed and under-addressed. Dwyer et al. (2022) recommends a need to integrate consideration of the intersectional identities of autistic students to support students adequately. Of the 34 times that intersectional considerations were mentioned in the literature, only three articles briefly and explicitly identify the impact of other marginalized identities, such as LGTBQ+ (Miller et al., 2020), race (Frost et al., 2019) and gender (Sturm and Kasari, 2019), on autistic students’ PS experiences. This represents a persistent gap where intersectional autistic identities need to be further explored.

Autistic students are actively engaging in identity management to navigate their environments and sense of self, with implications on identity acceptance or rejection, disclosure, and general well-being (MacLeod et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2020b; Cox et al., 2021). Identity management can be both a positive and damaging process, which should be accounted for in exploring autistic experiences. Positive expressions of identity management ground many individual-focused intervention strategies, such as empowerment, strengths-based approaches and self-advocacy (Anderson et al., 2018, 2020b; Accardo et al., 2019a; Budy, 2021). However, negative expressions of identity management often escalate co-occurring mental health concerns (Anderson A. M. et al., 2019; Lei and Russell, 2021) and can act as a barrier to accessing supports, whether due to fear of being bullied, othered or singled out (Casement et al., 2017; Cox et al., 2017; DeNigris et al., 2018; Goddard and Cook, 2022), or a desire to ‘prove oneself’ (Anderson et al., 2018). The role of identity management, as an internal process, points to the importance of actively including autistic voices to articulate unspoken factors contributing to autistic experiences.

This work collectively identifies multiple instances of autistic student exclusion, with deleterious impacts of a lack of support and imposed harm due to overt and covert action and inaction on PS campuses. This critical situation warrants immediate remedial and proactive action. While there has been focus in the literature on increasing inclusivity in the representation of voices in the literature, there remains an under-representation of autistic perspectives in this dialog. A strategy used in the literature to center autistic perspectives that is increasing in popularity is the use of participatory research processes (Fabri et al., 2016; Vincent et al., 2017; Hotez et al., 2018; Searle et al., 2019; Peña et al., 2020; Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2021). This review identified a few studies in the literature driven by self-identified autistic authors and an area that should receive more research attention. Examining these priorities on PS campuses must go beyond rhetoric and be demonstrated through policy and practice change.

The included articles, while drawn from an international context, were limited to English publications due to the language capacity of the research team. Relevant international literature may have been excluded due to this constraint; our search and results did elicit a study outside of western societies. Given the iterative coding process for the emerging themes, we acknowledge that the themes developed and emerged throughout the data extraction process, as opposed to undergoing a solely inductive approach to thematizing as would happen in a traditional secondary review. For this reason, the themes generated in this review were considered emerging and will be a starting point for future research to examine further, as well as to explore additional concepts that might not have been captured previously within autistic post-secondary student supports. Moreover, current gaps and the urgency for proactive action, informed our design, and we believe strongly advance this work in a way that a conventional discrete scoping review could not have done.

This scoping review offered a broad, international perspective encompassing supports and experiences of autistic PS students to capture the scope of the available literature. Results highlight the integrated nature of PS campuses that impacts student experiences and the efficacy of supports. As noted, a particular strength of this scoping review is its inclusion of an expert panel using autistic lived experiences (the ACP) into the methodology. This approach offered insight to align research interpretation with the perspective of lived experiences that enforces commitment to participatory action principles and to amplify the voices of autistic individuals in the literature and our communities. While the use of an expert panel incorporating autistic experiences has been utilized before in a scoping review (Scott et al., 2019), to our knowledge, this is the first scoping review addressing supports for and/or the experiences of PS autistic students to incorporate this step. This paper and its findings are not merely a review, but a resultant call to action in redressing barriers and creating PS environments that optimize student experience, nurture career development, and ensure best learning outcomes.

HN, DS, JC, HB, JR, MS, EC, AC, CD, CB, TK, PD, CH, TC, DN, and BD all made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work through development work on the project, and/or contributions to the coding framework developed for this scoping review. HN, DS, and JC all provided contributions to drafting the work, while HB, JR, MS, EC, PD, DN, and BD all made substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content. BD, HB, and DN all provided approval for publication of the content. BD agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We received financial support for this project from the Mitacs Accelerate Program (#IT28382), the Sinneave Family Foundation, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#892-2021-1084).

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of Laura Banfield for her guidance in developing the search strategy and Serena Lai for her contributions in preparing the manuscript for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1179865/full#supplementary-material

Accardo, A. L., Bean, K., Cook, B., Gillies, A., Edgington, R., Kuder, S. J., et al. (2019a). College access, success and equity for students on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 4877–4890. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04205-8

Accardo, A. L., Kuder, S. J., and Woodruff, J. (2019b). Accommodations and support services preferred by college students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 23, 574–583. doi: 10.1177/1362361318760490

Adams, D., Simpson, K., Davies, L., Campbell, C., and Macdonald, L. (2019). Online learning for university students on the autism spectrum: a systematic review and questionnaire study. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 35, 111–131. doi: 10.14742/ajet.5483

Ames, M. E., Coombs, C. E. M., Duerksen, K. N., Vincent, J., and McMorris, C. A. (2022). Canadian mapping of autism-specific supports for postsecondary students. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 90:101899. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101899

Ames, M. E., McMorris, C. A., Alli, L. N., and Bebko, J. M. (2016). Overview and evaluation of a mentorship program for university students with ASD. Focus Autism Dev. Disabil. 31, 27–36. doi: 10.1177/1088357615583465

Anderberg, E., Cox, J., Tass, E. S. N., Erekson, D. M., Gabrielsen, T. P., Warren, J. S., et al. (2017). Sticking with it: psychotherapy outcomes for adults with autism spectrum disorder in a university counseling center setting. Autism Res. 10, 2048–2055. doi: 10.1002/aur.1843

Anderson, A. (2018). Autism and the academic library: a study of online communication. C&RL 79, 645–658. doi: 10.5860/crl.79.5.645

Anderson, A. (2021). From mutual awareness to collaboration: academic libraries and autism support programs. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 53, 103–115. doi: 10.1177/0961000620918628

Anderson, C., and Butt, C. (2017). Young adults on the autism spectrum at college: successes and stumbling blocks. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 3029–3039. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3218-x

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., and Jennifer, S. (2018). Perspectives of university students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 651–665. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3257-3

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., and Jennifer, S. (2020b). Perspectives of former students with ASD from Australia and New Zealand on their university experience. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 2886–2901. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04386-7

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., and Stephenson, J. (2020a). An on-line survey of university students with autism spectrum disorder in Australia and New Zealand: characteristics, support satisfaction, and advocacy. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 440–454. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04259-8

Anderson, A. M., Cox, B. E., Edelstein, J., and Andring, A. W. (2019). Support systems for college students with autism spectrum disorder. Coll. Stud. Aff. J. 37, 14–27. doi: 10.1353/csj.2019.0001

Anderson, A., Stephenson, J., and Carter, M. (2017). A systematic literature review of the experiences and supports of students with autism spectrum disorder in post-secondary education. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 39, 33–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.04.002

Anderson, A. H., Stephenson, J., Carter, M., and Carlon, S. (2019). A systematic literature review of empirical research on postsecondary students with autism Spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 1531–1558. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3840-2

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Ashbaugh, K., Koegel, R., and Koegel, L. (2017). Increasing social integration for college students with autism spectrum disorder. Behav. Dev. Bull. 22, 183–196. doi: 10.1037/bdb0000057

Ashby, C., and Causton-Theoharis, J. (2012). "moving quietly through the door of opportunity": perspectives of college students who type to communicate. Equity Excell. Educ. 45, 261–282. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2012.666939

Austin, K. S., and Peña, E. V. (2017). Exceptional faculty members who responsively teach students with autism spectrum disorders. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 30, 17–32.

Baczewski, L., Kasari, C., Pizzano, M., and Sturm, A. (2022). Adjustment across the first college year: a matched comparison of autistic, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and neurotypical students. Autism Adulthood 4, 1–11. doi: 10.1089/aut.2021.0012

Bailey, K., Frost, K., Casagrande, K., and Ingersoll, B. (2020). The relationship between social experience and subjective well-being in autistic college students: a mixed methods study. Autism 24, 1081–1092. doi: 10.1177/1362361319892457

Bakker, T. C., Krabbendam, L., Bhulai, S., and Begeer, S. (2020). First-year progression and retention of autistic students in higher education: a propensity score-weighted population study. Autism Adulthood 2, 307–316. doi: 10.1089/aut.2019.0053

Bakker, T., Krabbendam, L., Bhulai, S., Meeter, M., and Begeer, S. (2022). Study progression and degree completion of autistic students in higher education: a longitudinal study. High. Educ. 2022:809. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00809-1

Ballantine, J., and Artemeva, N. (2020). Autistic university students’ accounts of interactions with nonautistic and autistic individuals: a rhetorical genre studies perspective. Rev. Da Anpoll 51, 29–43. doi: 10.18309/anp.v51i2.1406

Barnhill, G. P. (2016). Supporting students with Asperger syndrome on college campuses: current practices. Focus Autism Dev. Disabil. 31, 3–15. doi: 10.1177/1088357614523121

Bellon-Harn, M. L., Smith, D. J., Dockens, A. L., Manchaiah, V., and Azios, J. H. (2018). Quantity, quality, and readability of online information for college students with ASD seeking student support services. Read. Improv. 55, 7–14.

Bolourian, Y., Zeedyk, S. M., and Blacher, J. (2018). Autism and the university experience: narratives from students with neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 3330–3343. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3599-5

Bolourian, Y., Zeedyk, S. M., and Blacher, J. (2021). Autism goes to college: a workshop for residential life advisors. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 34, 191–200.

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kim, S. Y., and Miele, D. B. (2019). College students’ evaluations and reasoning about exclusion of students with autism and learning disability: context and goals may matter more than contact. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 307–323. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3769-5

Brazier, J. (2013). Having autism as a student at Briarcliffe College. Res. Teach. Dev. Educ. 29, 40–44.

Briel, L. W., and Getzel, E. E. (2014). In their own words: the career planning experiences of college students with ASD. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 40, 195–202. doi: 10.3233/JVR-140684

Brown, K. R. (2017). Accommodations and support services for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a national survey of disability resource providers. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 30, 141–156.

Brown, K. R., Peña, E. V., and Rankin, S. (2017). Unwanted sexual contact: students with autism and other disabilities at greater risk. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 771–776. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0059

Bublitz, D. J., Fitzgerald, K., Alarcon, M., D’Onofrio, J., and Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2017). Verbal behaviors during employment interviews of college students with and without ASD. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 47, 79–92. doi: 10.3233/JVR-170884

Budy, B. (2021). Embracing neurodiversity by increasing learner agency in nonmajor chemistry classes. J. Chem. Educ. 98, 3784–3793. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00247

Byrne, J. P. (2022). Perceiving the social unknown: how the hidden curriculum affects the learning of autistic students in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 59, 142–149. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2020.1850320

Cage, E., De Andres, M., and Mahoney, P. (2020). Understanding the factors that affect university completion for autistic people. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 72:101519. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101519

Cage, E., and Howes, J. (2020). Dropping out and moving on: a qualitative study of autistic people’s experiences of university. Autism 24, 1664–1675. doi: 10.1177/1362361320918750

Cage, E., and McManemy, E. (2022). Burnt out and dropping out: a comparison of the experiences of autistic and non-autistic students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:792945. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.792945

Cai, R., and Richdale, A. (2016). Educational experiences and needs of higher education students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 31–41. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2535-1

Casagrande, K., Frost, K., Bailey, K., and Ingersoll, B. (2020). Positive predictors of life satisfaction for autistic college students and their neurotypical peers. Adult Adulthood 2, 163–170. doi: 10.1089/aut.2019.0050

Casement, S., Carpio de los Pinos, C., and Forrester-Jones, R. (2017). Experiences of university life for students with Asperger’s syndrome: a comparative study between Spain and England. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 21, 73–89. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1184328

Cashin, A. (2018). The transition from university completion to employment for students with autism Spectrum disorder. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 39, 1043–1046. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1401188

Chandrasekhar, T. (2020). Supporting the needs of college students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 68, 936–939. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1686003

Cheriyan, C., Shevchuk-Hill, S., Riccio, A., Vincent, J., Kapp, S., Cage, E., et al. (2021). Exploring the career motivations, strengths, and challenges of autistic and non-autistic university students: insights from a participatory study. Front. Psychol. 12:719827. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719827

Chiang, E. S. (2020). Disability cultural centers: how colleges can move beyond access to inclusion. Disabil. Soc. 35, 1183–1188. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2019.1679536

Cho, J. (2018). Building bridges: librarians and autism spectrum disorder. Ref. Serv. Rev. 46, 325–339. doi: 10.1108/RSR-04-2018-0045

Chown, N., Baker-Rogers, J., Hughes, L., Cossburn, K., and Bryne, P. (2018). The 'high achievers' project: an assessment of the support for students with autism attending. J. Furth. High. Educ. 42, 837–854. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1323191

Clouder, L., Karakus, M., Cinotti, A., Ferreyra, M. V., Fierros, G. A., and Rojo, P. (2020). Neurodiversity in higher education: a narrative synthesis. High. Educ. 80, 757–778. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00513-6

Cox, B. E., Edelstein, J., Brogdon, B., and Roy, A. (2021). Navigating challenges to facilitate success for college students with autism. J. High. Educ. 92, 252–278. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2020.1798203

Cox, B. E., Nachman, B. R., Thompson, K., Dawson, S., Edelstein, J. A., and Breeden, C. (2020). An exploration of actionable insights regarding college students with autism: a review of the literature. Rev. High. Educ. 43, 935–966. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2020.0026

Cox, B. E., Thompson, K., Anderson, A., Mintz, A., Locks, T., Morgan, L., et al. (2017). College experiences for students with autism spectrum disorder: personal identity, public disclosure, and institutional support. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 71–87. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0004

Cullen, J. A. (2015). The needs of college students with autism spectrum disorders and Asperger’s syndrome. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 28, 89–101.

Dallas, B. K., Ramisch, J. L., and McGowan, B. (2015). Students with autism Spectrum disorder and the role of family in postsecondary settings: a systematic review of the literature. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 28, 135–147.

Davidovitch, N., Ponomaryova, A., Guterman, H., and Yair, S. (2019). The test of accessibility of higher education in Israel: instructors’ attitudes toward high-functioning autistic spectrum students. Int. J. High. Educ. 8, 49–67. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v8n2p49

Davidson, D., DiClemente, C., and Hilvert, E. (2021). Experiences and insights of college students with autism spectrum disorder: an exploratory assessment to inform interventions. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 71, 10–13. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1876708

Davis, M. T., Watts, G. W., and López, E. J. (2021). A systematic review of firsthand experiences and supports for students with autism spectrum disorder in higher education. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 84:101769. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101769

DeNigris, D., Brooks, P. J., Obeid, R., Alarcon, M., Shane-Simpson, C., and Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2018). Bullying and identity development: insights from autistic and non-autistic college students. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 666–678. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3383-y

Dickter, C., and Burk, J. (2021). The effects of contact and labeling on attitudes towards individuals with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 3929–3936. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04840-6

Dijkhuis, R., de Sonneville, L., Ziermans, T., Staal, W., and Swaab, H. (2020). Autism symptoms, executive functioning and academic progress in higher education students. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 1353–1363. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04267-8

Duerksen, K., Besney, R., Ames, M., and McMorris, C. A. (2021). Supporting autistic adults in postsecondary settings: a systematic review of peer mentorship programs. Autism Adulthood 3, 85–99. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0054

Dukes, L. L., Madau, J. W., Fagella-Luby, M., Lombardi, A., and Gelbar, N. (2017). PASSing college: a taxonomy for students with disabilities in postsecondary education. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 30, 111–122.

Dwyer, P., Mineo, E., Mifsud, K., Lindholm, C., Gurba, A., and Waisman, T. C. (2022). Building neurodiversity-inclusive postsecondary campuses: recommendations for leaders in higher education. Autism Adulthood 2022:42. doi: 10.1089/aut.2021.0042

Dymond, S., Meadan, H., and Pickens, J. (2017). Postsecondary education and students with autism spectrum disorders: experiences of parents and university personnel. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 29, 809–825. doi: 10.1007/s10882-017-9558-9

Elias, R., and White, S. (2018). Autism goes to college: understanding the needs of a student population on the rise. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 732–746. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3075-7

Everhart, N., and Anderson, A. (2020). Academic librarians' support of autistic college students: a quasi-experimental study. J. Acad. Librariansh. 46:102225. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102225

Everhart, N., and Escobar, K. (2018). Conceptualizing the information seeking of college students on the autism spectrum through participant viewpoint ethnography. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 40, 269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2018.09.009

Fabri, M., Andrews, P., and Pukki, H. (2016). Using design thinking to engage autistic students in participatory design of an online toolkit to help with transition into higher education. J. Assist. Technol. 10, 102–114. doi: 10.1108/JAT-02-2016-0008

Fabri, M., Fenton, G., Andrews, P., and Beaton, M. (2020). Experiences of higher education students on the autism spectrum: stories of low mood and high resilience. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 69, 1411–1429. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2020.1767764

Fairchild, L., Powell, M., Gadke, D., Spencer, J., and Stratton, K. (2020). Increasing social engagement among college students with autism. Adv. Autism 6, 83–93. doi: 10.1108/AIA-09-2019-0030

Fernandes, P., Haley, M., Eagan, K., Shattuck, P., and Kuo, A. (2021). Health needs and college readiness in autistic students: the freshman survey results. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 3506–3513. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04814-8

Flegenheimer, C., and Scherf, K. S. (2022). College as a developmental context for emerging adulthood in autism: a systematic review of what we know and where we go next. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 2075–2097. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05088-4

Fleischer, A. (2012). Support to students with Asperger syndrome in higher education--the perspectives of three relatives and three coordinators. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 35, 54–56. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32834f4d3b

Francis, G., Duke, J., Kliethermes, A., Demetro, K., and Graff, H. (2018). Apps to support a successful transition to college for students with ASD. Teach. Except. Child. 51, 111–124. doi: 10.1177/0040059918802768

Frost, K., Bailey, K., and Ingersoll, B. (2019). “I just want them to see me as...Me”: identity, community, and disclosure practices among college students on the autism spectrum. Autism Adulthood 1, 268–275. doi: 10.1089/aut.2018.0057

Gelbar, N., Shefyck, A., and Reichow, B. (2015). A comprehensive survey of current and former college students with autism spectrum disorders. Yale J. Biol. Med. 88, 45–68.

Gelbar, N. W., Smith, I., and Reichow, B. (2014). Systematic review of articles describing experience and supports of individuals with autism enrolled in college and university programs. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2593–2601. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2135-5

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Bisson, J., Saade, S., Obeid, R., Kofner, B. J., Harrison, A., et al. (2021). If you want to develop an effective autism training, ask autistic students to help you. Autism 26, 1082–1094. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.20108.74888

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Brooks, P., Someki, F., Obeid, R., Shane-Simpson, C., Kapp, S. K., et al. (2015). Changing college students' conceptions of autism: an online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J. Autism Child. Schizophr. 45, 2553–2566. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2422-9

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Bublitz, D., Donachie, A., Wong, V., D’Onofrio, J. P., and D’Onofrio, J. (2017). "for a long time our voices have been hushed": using student perspectives to develop supports for neurodiverse college students. Front. Psychol. 8:544. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00544

Glennon, T. (2016). Survey of college personnel: preparedness to serve students with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 70, 1–6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.017921

Gobbo, K., Shmulsky, S., and Bower, M. (2018). Strategies for teaching stem subjects to college students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 47, 12–17. doi: 10.2505/4/jcst18_047_06_12

Goddard, H., and Cook, A. (2022). "I spent most of freshers in my room"-a qualitative study of the social experiences of university students on the autistic spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 2701–2716. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05125-2

Grabsch, D., Melton, H., and Gilson, C. (2021). Understanding the expectations of students with autism to increase satisfaction with the on-campus living experience. J. Coll. Univ. Stud. Hous. 47, 24–43.

Gunn, S., Tyra, S., and Kraft, B. L. (2017). Application of coaching and behavioral skills training during a preschool practicum with a college student with autism spectrum disorder. Clin. Case Stud. 16, 275–294. doi: 10.1177/1534650117692673

Gurbuz, E., Hanley, M., and Riby, D. (2019). University students with autism: the social and academic experiences of university in the UK. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 617–631. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3741-4

Gustin, L., Funk, H., Reiboldt, W., Parker, E., Smith, N., and Blaine, R. (2020). Gaining independence: cooking classes tailored for college students with autism. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 33, 395–403.

Hamilton, J., Stevens, G., and Girdler, S. (2016). Becoming a mentor: the impact of training and the experience of mentoring university students on the autism spectrum. PLoS One 11:e0153204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153204

Harn, M., Azios, J., Azios, M., and Smith, D. (2019). The lived experience of college students with autism spectrum disorder: a phenomenological study. Coll. Stud. J. 53, 450–464.

Hassenfeldt, T. A., Factor, R. S., Strege, M. V., and Scarpa, A. (2019). How do graduate teaching sssistants perceive and understand their autistic college students? Autism Adulthood 1, 227–231. doi: 10.1089/aut.2018.0039

Hotez, E., Shane-Simpson, C., Obeid, R., DeNigris, D., Siller, M., Costikas, C., et al. (2018). Designing a summer transition program for incoming and current college students on the autism spectrum: a participatory approach. Front. Psychol. 9:46. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00046

Hu, Q., and Chandrasekhar, T. (2021). Meeting the mental health needs of college students with ASD: a survey of university and college counseling center directors. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 341–345. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04530-3

Jackson, S. L. J., Hart, L., Brown, J. T., and Volkmar, F. R. (2018). Brief report: self-reported academic, social, and mental health experiences of post-secondary students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 643–650. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3315-x

Kim, S. Y. (2022). College disability service office staff members’ autism attitudes and knowledge. Remedial Spec. Educ. 43, 15–26. doi: 10.1177/0741932521999460

Kim, S. Y., and Crowley, S. (2021). Understanding perceptions and experiences of autistic undergraduate students toward disability support offices of their higher education institutions. Res. Dev. Disabil. 113:103956. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103956

Kim, S. Y., Crowley, S., and Bottema-Beutel, K. (2021). Autistic undergraduate students’ transition and adjustment to higher education institutions. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 89:101883. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101883

Kingsbury, C. G., Sibert, E. C., Killingback, Z., and Atchison, C. L. (2020). “Nothing about us without us:” the perspectives of autistic geoscientists on inclusive instructional practices in geoscience education. J. Geosci. Educ. 68, 302–310. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2020.1768017

Knott, F., and Taylor, A. (2014). Life at university with Asperger syndrome: a comparison of student and staff perspectives. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 18, 411–426. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.781236

Koegel, L. K., Ashbaugh, K., Koegel, R. L., Detar, W. J., and Regester, A. (2013). Increasing socialization in adults with asperger’s. Psychol. Sch. 50, 899–909. doi: 10.1002/pits.21715

Kuder, S. J., and Accardo, A. (2018). What works for College students with autism Spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 722–731. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3434-4

Kuder, S. J., Accardo, A. L., and Bomgardner, E. M. (2021). Mental health and university students on the autism spectrum: a literature review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 8, 421–435. doi: 10.1007/s40489-020-00222-x

Lang, N. P., and Persico, L. P. (2019). Challenges and approaches for creating inclusive field courses for students with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Geosci. Educ. 67, 345–350. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2019.1625996

LeGary, R. A. (2017). College students with autism spectrum disorder: perceptions of social supports that buffer college-related stress and facilitate academic success. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 30, 251–268.

Lei, J., and Russell, A. (2021). Understanding the role of self-determination in shaping university experiences for autistic and typically developing students in the United Kingdom. Autism 25, 1262–1278. doi: 10.1177/1362361320984897

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., and O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lizotte, M. (2018). I am a college graduate: postsecondary experiences as described by adults with autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 6, 179–191. doi: 10.18488/journal.61.2018.64.179.191

Lucas, R., Cage, E., and James, A. (2022). Supporting effective transitions from university to post-graduation for autistic students. Front. Psychol. 12:768429. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.768429

Lucas, R., and James, A. (2018). An evaluation of specialist mentoring for university students with autism spectrum disorders and mental health conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 694–707. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3303-1

MacLeod, A., Allan, J., Lewis, A., and Robertson, C. (2018). ‘Here I come again’: the cost of success for higher education students diagnosed with autism. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 22, 683–697. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1396502

MacLeod, A., Lewis, A., and Robertson, C. (2013). ‘Why should I be like bloody rain man?!’: Navigating the autistic identity. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 40, 41–49. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12015

Madaus, J., Cascio, A., Delgado, J., Gelbar, N., Reis, S., and Tarconish, E. (2022). Improving the transition to college for twice-exceptional students with ASD: perspectives from college service providers. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 46, 40–51. doi: 10.1177/21651434221091230

Manett, J. (2022). The social association for students with autism: principles and practices of a social group for university students with ASD. Soc. Work Groups 45, 157–171. doi: 10.1080/01609513.2021.1994511

Masterson-Algar, A., Jennings, B., and Odenwelder, M. (2020). How to run together: on study abroad and the ASD experience. Frontiers 32, 104–118. doi: 10.36366/frontiers.v32i1.436

Matthews, N. L., Ly, A. R., and Goldberg, W. A. (2015). College students’ perceptions of peers with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 90–99. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2195-6

McLeod, J. D., Hawbaker, A., and Meanwell, E. (2021). The health of college students on the autism spectrum as compared to their neurotypical peers. Autism 25, 719–730. doi: 10.1177/1362361320926070

McLeod, J. D., Meanwell, E., and Hawbaker, A. (2019). The experiences of college students on the autism spectrum: a comparison to their neurotypical peers. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 2320–2336. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03910-8

McMorris, C. A., Baraskewich, J., Ames, M. A., Shaikh, K. T., Ncube, B. L., and Bebko, J. M. (2019). Mental health issues in post-secondary students with autism spectrum disorder: experiences in accessing services. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 17, 585–595. doi: 10.1007/s11469-018-9988-3

Miller, R. A., Nachman, B. R., and Wynn, R. D. (2020). “I feel like they are all interconnected”: understanding the identity management narratives of autistic LGBTQ college students. Coll. Stud. Aff. J. 38, 1–15. doi: 10.1353/csj.2020.0000

Munandar, V. D., Bross, L. A., Zimmerman, K. N., and Morningstar, M. E. (2021). Video-based intervention to improve storytelling ability in job interviews for college students with autism. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 44, 203–215. doi: 10.1177/2165143420961853

Nachman, B. R. (2020). Enhancing transition programming for college students with autism: a systematic literature review. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 33, 81–95.

Nachman, B. R., McDermott, C. T., and Cox, B. E. (2022). Brief report: autism-specific college support programs: differences across geography and institutional type. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 863–870. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-04958-1

Ncube, B. L., Shaikh, K. T., Ames, M. E., McMorris, C. A., and Bebko, J. M. (2019). Social support in postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 17, 573–584. doi: 10.1007/s11469-018-9972-y

Ness, B. M. (2013). Supporting self-regulated learning for college students with Asperger syndrome: exploring the "strategies for college learning" model. Mentor. Tutoring 21, 356–377. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2013.855865

Newman, L., Wagner, M., Knokey, A.M., Marder, C., Nagle, K., Shaver, D., et al. (2011). The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school: a report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). NCSER 2011–3005. In National Center for Special Education Research. National Center for Special Education Research.

Nuske, A., Rillotta, F., Bellon, M., and Richdale, A. (2019). Transition to higher education for students with autism: a systematic literature review. J. Divers. High. Educ. 12, 280–295. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000108

Peña, E., Gassner, D., and Brown, K. (2020). Autistic-centered program development and assessment practices. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 33, 233–240.

Pennington, R. C., Bross, L. A., Mazzotti, V. L., Spooner, F., and Harris, R. (2021). A review of developing communication skills for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities on college campuses. Behav. Modif. 45, 272–296. doi: 10.1177/0145445520976650

Pesonen, H. V., Waltz, M., Fabri, M., Lahdelma, M., and Syurina, E. V. (2021). Students and graduates with autism: perceptions of support when preparing for transition from university to work. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 531–546. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1769982

Pesonen, H., Waltz, M., Fabri, M., Syurina, E., Krückels, S., Algner, M., et al. (2021). Stakeholders’ views on effective employment support strategies for autistic university students and graduates entering the world of work. Adv. Autism 7, 16–27. doi: 10.1108/AIA-10-2019-0035

Petcu, S. D., Zhang, D., and Li, Y.-F. (2021). Students with autism spectrum disorders and their first-year college experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:11822. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211822

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Khalil, H., Larsen, P., Marnie, C., et al. (2022). Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid. Synth. 20, 953–968. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-21-00242

Pionke, J. J., Knight-Davis, S., and Brantley, J. S. (2019). Library involvement in an autism support program: a case study. Coll. Undergrad. Lib. 26, 221–233. doi: 10.1080/10691316.2019.1668896

Pollock, D., Alexander, L., Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Khalil, H., Godfrey, C. M., et al. (2022). Moving from consultation to co-creation with knowledge users in scoping reviews: guidance from the JBI scoping review methodology group. JBI Evid. Synth. 20, 969–979. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-21-00416

Ponomaryova, E., Guterman, H. G., Davidovitch, N., and Shapira, Y. (2018). Should lecturers be willing to teach high-functioning autistic students: what do they need to know? High. Educ. Stud. 8:35. doi: 10.5539/hes.v8n4p35

Quinn, S., Gleeson, C. I., and Nolan, C. (2014). An occupational therapy support service for university students with Asperger’s syndrome (AS). Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 30, 109–125. doi: 10.1080/0164212X.2014.910155

Rando, H., Huber, M., and Oswald, G. (2016). An academic coaching model intervention for college students on the autism spectrum. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 29, 257–262.

Retherford, K., and Schreiber, L. (2015). Camp campus: College preparation for adolescents and young adults with high-functioning autism, asperger syndrome, and other social communication disorders. Top. Lang. Disord. 35, 362–385. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000070

Ribu, K. (2018). Research-based educational support of undergraduate students with autism spectrum disorders. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 47, 1038–1050. doi: 10.1177/0040059914553207

Roberts, N., and Birmingham, E. (2017). Mentoring university students with ASD: a mentee-centered approach. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 1038–1050. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2997-9

Rothman, E., Heller, S., and Graham Holmes, L. (2021). Sexual, physical, and emotional aggression, experienced by autistic vs. non-autistic U.S. college students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2021, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1996373

Rowe, T., Tyler, C., and DuBose, H. (2020). Supporting students with ASD on campus: what students may need to be successful. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 33, 97–101.

Sarrett, J. C. (2018). Autism and accommodations in higher education: insights from the autism community. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 679–693. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3353-4