94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 15 June 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1177519

Introduction: A community cannot avoid the frustrating problem of antisocial behavior, which consists of actions that violate traditions or standards. To deal with the antisocial behavior and aggression in children, a variety of techniques and interventions have been proposed and applied throughout the world. Teachers can overcome antisocial behavior in educational institutions through professional development programs. In Pakistan, there are few studies that focus on teachers’ professional development in behavior management, which should be investigated.

Methods: A qualitative research study examined teacher professional development courses aimed at improving classroom management skills and controlling antisocial behaviors by collecting information from instructors. This approach was taken because this study aims to identify teacher educators’ experiences related to antisocial and aggression control training in the school setting. In addition, the limitations and challenges associated with such development programs are revealed through semi-structured interviews.

Results: Researchers reported major challenges related to such trainings include resistance and unwillingness of school authorities and teachers to participate in such trainings, as well as lack of resources and finances.

Discussion: To ensure that teacher training is effective and leads to the development of teacher skills and improvement of student behavior, researchers recommend implementing evidence-based intervention programs with ongoing monitoring by a trained teacher specialist. It is also recommended that curricula be standardized and in-service training results be empirically verified.

Antisocial behavior is characterized by actions that go against traditions, rules, or standards, and this disruptive behavior poses an inevitable challenge for society (Siddiqui et al., 2018). Aggressive behaviors are antisocial behaviors aimed at harming a person or animal or damaging physical property. In addition, numerous studies have shown that a steady increase in aggressive behavior in children increases the likelihood that they will become delinquent (Thomas et al., 2015), leading to high rates of juvenile delinquency, and the consequences can be irreversible if not intervened early (Loeber, 2003). In addition to these behaviors, if they continue to increase, they lead to other problematic behaviors such as injury-related, risk-taking safety problems (Thuen and Bendixen, 1996), low social skills, development of narcissism and self-esteem problems (Bushman and Baumeister, 1998), short temper (Vassallo et al., 2002), poor academic performance (Luiselli et al., 2005), disrespectful behavior (Hastings and Bham, 2003), and expulsion from school (Hemphill et al., 2007). A persistent behavior problem in childhood also negatively affects adult well-being, employment, and marriage (McGee et al., 2011). A variety of techniques and interventions have been proposed and applied worldwide for dealing with antisocial behavior. A literature review presents detailed studies and interventions to improve and modify behavior problems and behavior-related problems in children. These interventions include three different aspects: interventions in which children are counseled and trained (Sukhodolsky et al., 2016), interventions in which parenting skills are improved through management training (Webster-Stratton and Hammond, 1997; Sukhodolsky et al., 2016), and school-based mediations in which teachers are trained to modify behavior (Humphrey et al., 2016). A mixed approach has been observed in some studies, where combinations of training for different target groups (parents and children, teachers and children) have been observed together and empirically tested (Mushtaq, 2015).

Teacher professional development programs are based on the premise that teachers are the key stakeholders who can change the school environment by using their skills to reduce antisocial behaviors (Strohmeier et al., 2012). Teacher-directed interventions to control behavior problems have been discussed in the literature, but programs have shown conflicting results (van Verseveld et al., 2019). Teacher-led intervention programs are considered practical and successful, especially in low- to middle-income countries such as Pakistan, because of their low cost compared to programs delivered by external psychologists (Rajaraman et al., 2015). According to a literature review, professional development for teachers in general can be a successful attempt to address behaviors that impede or disrupt student learning, and teachers need necessary skills to deal with challenging behaviors and antisocial behavior problems (McKenna et al., 2015; Shinde et al., 2018). Some of the replicated or translated versions of training from developed countries have been adapted and applied in Pakistan (Mushtaq, 2015). Despite this, there is a lack of extensive literature in conjunction with the empirical research. Researchers are working to fill this gap, and the information provided by participants is analyzed and discussed. Despite evidence from various studies, such as those conducted by Naveed et al. (2020), Saleem et al. (2021), and Siddiqui et al. (2023), indicating that antisocial behavior is a common occurrence among students in Pakistani educational institutions, the country’s education system remains primarily focused on achieving superior grades and overlooks the various challenges faced by students (Ahmed et al., 2022). While most teachers have a general understanding of how to handle aggressive behavior, there is still a lack of expertise in this area (Hakim and Shah, 2017). Therefore, it is recommended that cost-effective, research-based professional development programs be developed for teachers to address these issues and create a conducive learning environment in schools (Siddiqui and Schultze-Krumbholz, 2023).

This study evaluates the status of professional development courses for teachers in Pakistan. These courses specifically aim to develop classroom management skills, solve behavioral problems among students, and intervene to control these behaviors. In addition, the limitations and challenges associated with such training courses are revealed through semi-structured interviews.

The current study aimed to explore answers to the following research questions:

• What kind of professional development is conducted for teachers in Pakistan for managing antisocial behaviors in the classroom?

• What are the themes, content, and sources of training?

• How is the efficiency of such professional development programs measured and what are the key challenges and limitations?

In the literature review, researchers have highlighted the status of antisocial behavior issues in Pakistan and how internationally teachers are trained through professional development programs to develop their skills in improving classroom management and addressing antisocial conduct issues. In addition, some limitations associated with such training programs are also highlighted in the review.

Teacher education, often called teacher training or teacher professional development, encompasses a range of programs, policies, procedures, and resources aimed at providing teachers with the necessary knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, methodologies, and skills to carry out their duties effectively within the classroom, school, and broader community. The importance of high-quality teacher education lies in the fact that teacher education is one of the finest and most important conditions for education promotion, improvement and development. Investment in teacher education can produce high quality teachers who are committed, pedagogically sound, and interested in student learning and development (Mulenga, 2020). A variety of techniques are used by teachers to learn, including learning from their own practice, living practical experiments (Wilson et al., 1987), reflective practices (Lovett, 2002), problem solving through experiences (Fraser, 2008), observation (Bubb, 2014), by using constructive feedback (Totterdell et al., 2002), through collaborative discussion (Peterson, 1988), through peer coaching (Joyce and Showers, 1982), by using tools and technologies (Prestridge, 2010) and through self-directed instructions (Boud et al., 1997). A professional development course should provide teachers with a range of opportunities to improve their learning and skills in the classroom, considering how teachers learn and improve in the classroom. Most international teacher training programs developed for student behavior management are based on theories of social learning and social cognition and emphasize the importance of explicitly teaching social–emotional and behavioral skills in supportive relationships. Professional development programs of this nature enhance teachers’ abilities to facilitate activities that assist both children and adults in comprehending and regulating their emotions by teaching them techniques for emotional management, encouraging them to establish and attain constructive objectives, involving them in exercises to cultivate empathy, supporting them in building and maintaining positive relationships, and guiding them in making responsible decisions (Moutiaga and Papavassiliou-Alexiou, 2021). However, due to the lack of similar training in the Pakistani context, the underlying theories and practices in this South Asian region have not been explicitly explained. Therefore, this study aims to explore the sources of professional development programs and to identify their underlying theoretical frameworks.

In Pakistan, the process of educating teachers is divided into two parts: initial teacher preparation or pre-service education, and continuing teacher development or in-service education. At present, Pakistan provides three pre-service teacher education programs, which are B.Ed. (Honors) Elementary, B.Ed. Secondary, and Associate Degree. Previously, there were various teacher preparation programs available, including 1-year Certificate in Teaching (CT), 1-Year Primary Teaching Certificate (PTC), 1-Year Diploma in Education, 1-year Bachelor in Education, and Masters in Education. The restructuring of teacher education in Pakistan led to the phasing out of PTC, CT, Diploma in Education, and 1-year B.Ed, which were replaced with a 4-year B.Ed (Honors) program and a 2-year Associate Degree in Education in 2016, according to the Higher Education Commission (Qureshi and Kalsoom, 2022). Zafar and Ali (2018) have highlighted the lack of a standardized curriculum in Pakistan’s education system and teaching and training institutes. Significant variations exist in education programs, not only among various regions but also within the same city and across different universities. Within teacher education programs, courses addressing psychological issues exist under various titles across different universities, such as Human Development, Educational Psychology, or Advanced Educational Psychology. While some fundamental theories are consistent, aggression or related theories is not obligatory in these courses. Teachers personally devise their course outlines based on their preferences, which also vary due to other influencing factors such choice of students, instructions from management etc.

There are several challenges related to teachers’ professional development, especially in a country like Pakistan where low funding and poor infrastructure have hindered teachers’ performance improvement. The cost of addressing anti-social behaviors poses a significant challenge for many parents, according to Lindgren et al. (2016) study. Teacher training is also expensive and organizations are unwilling to bear the additional costs associated with it. A qualitative research report submitted to Aga Khan University by Rehmani (2006) states that teachers in Pakistan attend workshops but new learning cannot be imparted due to resource constraints, lack of time, and teacher shortages. In addition, professional development tends to be about instructional practices, assessment, role modeling, and limited understanding of classroom management issues. However, no interventions to control antisocial behaviors were observed in any of the professional development courses (Rehmani, 2006). Furthermore, Dayan et al. (2018) reported that one of the challenges in teacher education in Pakistan is the gap between the training theory and actual practice in the classroom, and that teachers are unable to manage conflictual behavior in the classroom even after participating in professional development programs. Other issues were reported by Siddiqui et al. (2021a) include that, in addition to financial constraints, teacher education institutes lack facilities such as teaching aids, buildings, libraries, furniture, teaching materials, and other supplies. Poor management and inefficient administration are also among the most frequently cited problems (Azam et al., 2014). In addition, the quality of such programs is also questionable (Jumani and Abbasi, 2015). Last but not least, teachers who are not encouraged to do their jobs effectively are likewise demotivated to participate in pre-service or in-service training, which affects their morale (Maharjan, 2012).

To authorize teacher education programs, the Government of Pakistan and Higher Education Commission established the National Accreditation Council for Teacher Education (NACTE), an independent body in 2009 (Qureshi and Kalsoom, 2022). These steps are likely to enhance the quality of teacher education and lead to visible improvements in Pakistan’s education system.

Reports of an increase in antisocial behaviors such as bullying in academic institutions in recent years are undeniable (Ferrer-Cascales et al., 2019) and have been described as a serious public health problem (Waasdorp et al., 2017), with long-term negative effects on physical and mental health (Moore et al., 2017). Similarly, aggressive behavior has been reported not only in Pakistani higher education institutions but also in secondary and elementary schools (Naveed et al., 2020; Saleem et al., 2021). Studies conducted on an international level have indicated that countries with a greater incidence of face-to-face aggressive behaviors also tend to have elevated levels of cyberbullying (Livingstone et al., 2011). Furthermore, cyberbullying is often found to occur alongside more conventional forms of antisocial conduct (Kowalski et al., 2014), and an increase in cyber aggression or cyberbullying can be seen as a clear indicator of a rise in aggression throughout society as a whole. Several studies have revealed that anti-social acts such as bullying and cyberbullying are routine in Pakistani educational institutions and affect students’ physical, emotional and mental health (Khawaja et al., 2015; Asif, 2016; Magsi et al., 2017; McFarlane et al., 2017; Musharraf and Anis-ul-Haque, 2018; Rafi, 2019; Mirza et al., 2020). The Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) of Pakistan has confirmed that cyber-related crimes are steadily increasing as the number of internet users increases (Shakeel, 2018), and statistics have shown that adolescents are engaging in more risky, antisocial behaviors online (Saleem et al., 2021; Siddiqui et al., 2021c). Similarly, despite the frequent concerns about antisocial aggressive behavior in low- and middle-income countries and the chronicity of conduct problems, emotional problems, and behavioral difficulties in Pakistan, there are few policies and interventions designed, implemented, and evaluated (Naveed et al., 2020). The review of interventions in Pakistan has confirmed that there is a great need for interventions to control antisocial problems. Most of the adapted/adopted and applied interventions focused only on one aspect of education, such as participation in physical activities (Karmaliani et al., 2017; McFarlane et al., 2017), creating a safe physical environment (Hakim and Shah, 2017) and enhancing pro-social skills and emotional management of the victims (Maryam and Ijaz, 2019). However, a full curriculum or detailed training program has not been evaluated, and research-based evidence training programs are lacking in the published literature.

Numerous international interventions have been developed to address antisocial behavior in both children and adults. One such intervention is Cognitive Reappraisal, which has been utilized in various contexts, including parental behavior modification (Preuss et al., 2021), teacher emotional regulation (Xie, 2021), and for children’s emotional regulation (Nook et al., 2020). However, a systematic review conducted by Ramzan and Amjad (2017) revealed that Cognitive Reappraisal is not commonly practiced as an emotional regulation strategy in Pakistan. In the research study of Barlett and Anderson (2011), cognitive reappraisal was explained in detail, highlighting that early reappraisal, in which the participant already has an idea that his or her emotions are being provoked, requires less mental effort than late reappraisal, which occurs after a pronounced negative emotional experience. Because provocations are often unexpected, early reappraisal usually dissipates. Justifying information has also been shown to facilitate late reappraisal, thereby reducing anger and vengeance in response to provocation. Provocative behavior is less likely to elicit a violent response if the provocateur has a valid reason.

Other common therapies are based on Cognitive Behavioral Theories (CBT). Therapies for children based on cognitive behavioral theories focus on improving anger control skills to manage anger and frustration as part of emotion regulation strategies (Sukhodolsky et al., 2016). Two main themes of the cognitive-behavioral program are to help children find ways to cope with the intensification of physiological arousal and anger they experience immediately after a provocation or frustration, and to help children retrieve from a bad memory a set of possible competent strategies they could use to resolve the frustrating problem or conflict they are experiencing (Smith et al., 2005). These treatments can be used not only with adolescents, but also with adults (McGuire, 2002, 2008; Polaschek et al., 2005) or with adolescents involved in violent crimes (Rappaport and Thomas, 2004).

A parenting intervention called the Coping Power Program proposed by Mushtaq (2015) focuses on targeted training for parents and children. This program is a combination of cognitive and behavioral therapy techniques from established parent training programs. It also includes novel techniques for children identified as having a social-cognitive risk factor for externalizing behavior problems. The successful results of the coping power program have prompted teacher educators to use and implement the content in teacher education as well, but as Mushtaq (2015) noted, empirical testing and research-based studies are needed for such programs, especially in the Pakistani context.

Self-control training (SCT) is another popular intervention in which teachers teach children how to improve their self-control by practicing self-control strategies (Denson, 2015). SCT is derived from the strength model of self-control, in which self-control is defined as a general skill that can be strengthened through practice (Burns et al., 2003; Oaten and Cheng, 2006; Baumeister et al., 2007).

Mindfulness is another effective strategy often practiced in Buddhist meditation, sometimes referred to as YOGA (Giraldi, 2019), as well as in spiritual intelligence training (Nemati et al., 2017), which aims to promote awareness and acceptance of anger and help people control anger when they have rage-driven impulses. Mindfulness is defined by Kabat-Zinn (2003) as “mindfulness is a state of nonjudgmental awareness in which one focuses on the present moment and accepts ongoing physical and mental experiences.” Mindfulness is used to promote awareness and acceptance of anger and to help people control anger when they have anger-driven impulses. Singh et al. (2003) state that mindfulness-based therapies make a person calm whose mind is focused on the present moment. This state of mindfulness allows the individual to be aware not only of external conditions but also of internal conditions, particularly physiological arousal states. It is believed that the non-reactive nature of mindfulness is an ideal strategy for reducing anger and aggression (Singh et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2009) and can be successfully implement by trained teachers to handle antisocial aggressive issues among children (Singh et al., 2017).

A full curriculum with many activities aimed at improving children’s prosocial behavior (Humphrey et al., 2016) and has achieved commendable results in the past. Incredible Years (IY) Teacher Classroom Management is one of the school-based intervention strategies that have been empirically tested and applied in different school contexts. A research study by Webster-Stratton and Reíd (2008) evaluated the outcomes of Incredible Years (IY) Teacher Classroom Management and the Children’s Social and Emotional Curriculum (Dinosaur School Curriculum), which was developed under the guidance of Incredible Years team members to improve children’s social skills and suppress behavior problems. Parents were involved through homework assignments sent home and positive reinforcement from teachers in the classrooms. Robust results were noted at the end of the year.

One of the most common problems in schools is how to deal with aggressive children (Shechtman and Ifargan, 2009). Greenberg et al. (2003) applied preventive interventions in the classroom by improving children’s relationships and social development and found this to be an effective method. Shechtman and Ifargan (2009) reported that changing social dynamics in the classroom led to better relationships, establishment of anti-aggression norms, and increased caring among students. Similarly, Corsini (2007) suggested that improved empathy and responsiveness reduce aggression. It is pointed out that in schools to control behavior problems, a common strategy is to segregate the child with the behavior problem to protect other well-behaved children from bad influences and treat them individually or in small groups (Glancy and Saini, 2005; Horne et al., 2007). However, Dodge (2006) argues that clustering children with conduct disorder together has a negative effect on them and may lead to an increase in the intensity of the conduct disorder. Shechtman and Ifargan (2009) compared the results of school-based intervention with individual counseling sessions. They found both treatments equally effective. Perhaps a combination of the two methods would yield even better results, a goal that needs further investigation. In Humphrey et al. (2016) study, the effectiveness of the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies curriculum as a means of improving children’s social–emotional competence was investigated. The children in the experimental group showed improved social–emotional competence. In addition, the teachers themselves also showed improvement in their prosocial behavior and emotional stability. Therefore, social and emotional learning is considered a school-based universal preventive intervention to solve behavior problems. In another study conducted in the Pakistani context, Hussein and Vostanis (2013) the effect of a 2-day workshop on identifying and managing difficult behaviors in children was evaluated and better results were found when the data were analyzed. One hundred and fourteen elementary school teachers were recruited for the training and effectiveness was measured by knowledge before and after the training. However, it was suggested that principals and policy makers should also be involved in such trainings.

Abundant international literature provides evidence that school-based interventions, involving teachers who have received professional training to address behavioral issues, have yielded remarkable outcomes in enhancing children’s behavior and diminishing their antisocial and aggressive tendencies. However, it is recommended that evidence-supported research studies be conducted to address the lack of training interventions in the Pakistani context. The review has already revealed that there are limited evidence-based research studies to highlight details of teacher professional development courses specifically designed to control antisocial behaviors among students in Pakistan. The study aims to fill this gap by gathering relevant information from teacher trainers associated with such trainings.

The study employed a qualitative survey approach which utilized both open-ended and structured questions to elicit written responses from participants. The questions aimed to uncover the opinions and experiences of teacher trainers. The survey was distributed to participants via email in written format, and the authors provided contextual information and key definitions to assist respondents in understanding the survey questions since they could not clarify them in real-time. Participants were asked to provide detailed written responses to illuminate their perceptions or understanding, which resulted in a range of diverse responses. Our research followed the data analysis approach outlined by Strauss and Corbin (1998), which involved categorizing the data based on recurring patterns. This process involved axial coding, followed by focused and selective coding to identify themes. Ultimately, a thematic analysis was conducted using this method. It is important to note that English is not the first language for these participants. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that in the context of Pakistan, disruptive, aggressive, and antisocial behaviors are used synonymously. The authors made efforts to improve the structural and grammatical errors in the written responses and subsequently shared the revised statements/words with the participants to ensure accuracy and consistency.

A purposive sample was used in this study. The study necessitated the inclusion of teacher trainers who possessed experience in developing teachers’ abilities to manage antisocial behavior among students. To identify suitable participants, the researchers reached out to educators within a private university’s education department. Throughout the research process, the investigators initially reached out to respondents associated with their university who were engaged in teacher training. However, due to a limited number of participant responses, additional assistance was sought from other university members and participants to identify more trainers within the city. Once the researchers obtained information about trainers from other institutions, they promptly extended invitations for their participation in the study and invited them to voluntarily participate in the study. A total of 14 teacher trainers engaged in a teacher training program aimed at improving student behavior and controlling student aggression and antisocial behavior were contacted for voluntary participation in the study. A semi-structured self-report questionnaire in English Language prepared by the researchers and validated by experts from the education department of a private university in a major Pakistani city was shared via email (Example questions, Trainings used by you and your organization are adopted/adapted from developed countries or formulated here in Pakistan to meet contextual and local needs?, Please mention the challenges faced in planning, executing and evaluating such training programs, if any, Do you think there is a need of introducing such trainings in Pakistan?). 11 participants responded and provided the information requested in the questionnaire. Study participants included nine teacher educators who had trained teachers during in-service trainings on managing challenging behavior and two teacher educators (Participants B and J) who planned to conduct workshops on challenging behavior in the classroom in the future. The participants were mostly from educational psychology and psychology backgrounds. They ranged in age from 27 to 47 years and had between 3- and 12-years’ experience in teachers’ education (refer to Table 1). Participants also provided information about the main topic of their professional training and some additional details, which are listed in Table 2.

This study aims to determine the effectiveness of professional development courses for teachers developed and implemented in Pakistan. These courses were designed to control student antisocial behavior as part of a behavior management program. Data were collected using open-ended questions and analyzed based on information provided by 11 instructors working in this field. This process involved axial coding, followed by focused and selective coding to identify themes. Ultimately, a thematic analysis was conducted using this method.

The participants in the current study were involved in teacher training and provided useful information. When asked which international trainings their content had been developed from, participants indicated a variety of international activities, most of which had been adopted from multiple trainings. There were 27 responses from 11 participants, with the majority mentioning more than one international intervention name. As a result of these responses, Table 3 was developed.

Table 3 shows that most of the content adapted by trainers was from trainings based on cognitive behavioral theory, which has been empirically tested internationally and applied in different contexts (Sukhodolsky et al., 2016), while the least used intervention was based on cognitive reappraisal, which is one of the components of cognitive behavioral theory (Denson, 2015) and involves assigning a different meaning to the stimulus and reflecting on positive aspects of the event (Gross and Thompson, 2007). According to the findings of Ramzan and Amjad (2017), the infrequent use of Cognitive Reappraisal as a technique to tackle emotional and antisocial issues in Pakistan is in line with the responses of the participants. The main focus of therapies for children based on cognitive behavioral theories is on improving anger control skills to manage anger and frustration as part of emotion regulation strategies (Sukhodolsky et al., 2016). Numerous studies have implemented interventions based on cognitive-behavioral theories in Pakistan (Mahr et al., 2015; Chiumento et al., 2017; Amin et al., 2020), and the responses from participants have been consistent, indicating that the contents of this theory are frequently utilized by teacher trainers in Pakistan. Self-Control Training (SCT) is a well-known intervention method where teachers educate children on improving their self-control through the implementation of self-control strategies (Denson, 2015). However, the lack of literature on the use of SCT in Pakistan makes it challenging to assess the outcomes of previous research. This study surprisingly found that SCT is the second most commonly adapted international intervention in teacher training programs. Nevertheless, further research based on evidence is necessary to investigate its outcomes. Similarly, importance has been given to the Coping Power Program, promotion of alternative thinking strategies, and practice of mindfulness. The successful results of the coping power program have prompted teacher educators to use and implement the content in teacher education. However, Mushtaq (2015) noted, empirical testing and research-based studies are needed for such programs, especially in the Pakistani context.

According to Tao et al.'s (2021) systematic review report, Mindfulness-based interventions have been found to be effective in managing aggressive and antisocial behavior among children. Singh et al. (2017) suggest that teachers have used these techniques to assist students in addressing their behavioral problems. Although no research evidence exists regarding how teachers in Pakistan have utilized this approach, our study’s findings indicate that mindfulness-based interventions are becoming more popular in Pakistan. Despite the scarcity of literature on this topic, this study offers new opportunities for further exploration of these interventions in Pakistan. Participants in the study identified the implementation of Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHs) in training courses, which has previously produced positive outcomes in schools across various regions (Eninger et al., 2021). Furthermore, a recent review conducted by Barlas et al. (2022) found that PATHs has started gaining acceptance in schools throughout Pakistan, which is consistent with the findings of the present study. In the current study, three participants used the Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Curriculum. However, empirical studies are needed to demonstrate its effectiveness in the Pakistani context. From the data, it appears that the sources of such training vary and the content is adopted/adapted from successfully implemented international interventions and training. It is still debatable whether these trainings have profoundly impacted the Pakistani context or not.

Similarly, different topics are covered in the courses. Details on the targeted topics and themes of the various training programs are provided in Table 4. From this study, it is clear that the various forms of training with a variety of activities are aimed at specific behavioral changes. However, the real goal of these trainings is to improve teachers’ ability to deal with students’ antisocial behavioral problems. Participants B and J are not directly involved in teacher training on behavior change, but their suggestions are also highlighted.

It is evident from the table that most of the programs (6 out of 11) are focused on addressing the emotional needs of students as suggested by Webster-Stratton and Reid (2003). However, only one participant identified that if a teacher is emotionally healthy then he/she can apply strategies in a more effective manner, thus recommending having sessions addressing the emotional needs of teachers as well. Participants B, J and K highlighted the importance of psychological content in training and suggested that introduction to child psychology and the ability to screen out problematic behavior and disorders for teachers are necessary to identify proper and effective interventions for targeted children. Aligned with Corsini (2007) suggestions, four out of 11 participants highlighted the importance of teacher-student bonding and focusing on strategies designed to create a positive relationship between mentor and pupil. Development of counseling skills among teachers, setting classroom boundaries, and identifying challenging behaviors and activities were some of the common responses received from participants as suggested by Shechtman and Ifargan (2009) in their research. Focusing on developing social responsibility and accountability in children, anger management skills, and addressing individual differences are also training components. One of the participants highlighted the importance of cognitive skills among children as an effective strategy for behavior modification as pointed out by Denson (2015) and Sukhodolsky et al. (2016).

One of the questions was to highlight some of the activities used in professional development programs. The current study concluded from the responses received that programs designed to improve teacher competencies had well-structured, active participation, and democratic training styles. Some of the common activities included role models, hands-on practice sessions, simulations, demonstrations, MODCal (interactive multimedia sessions), interactive videos, discussion on the case studies, brainstorming session and related activities, teaching with games, art therapy, storytelling, sharing personal experiences, sharing success stories and learning through reflections.

In addition, the effectiveness and evaluation of these trainings were investigated. Although the trainings were designed to teach teachers about behavior improvement and aggression control in students, there was a lack of data on classroom implementation success rate. Unlike in developed countries, where continuous classroom visits by the trainer or a third-party observer are regular practices to ensure teachers’ skills have improved (Olweus and Limber, 2010), such practices are largely absent in Pakistan (Siddiqui et al., 2023). Three participants reported that training outcomes are calculated by assessing teachers’ practices in classrooms after training is completed. According to one participant, self-reported feedback from participants is a regular practice at workshops or in-service training courses. However, this practice is not sufficient to confirm the results, as bias, memory problems, or the Hawthorne effect are among the major limitations of self-assessment. For such training to be authentic in Pakistan, empirical research with a quasi-experimental and pre-post-experimental design is needed.

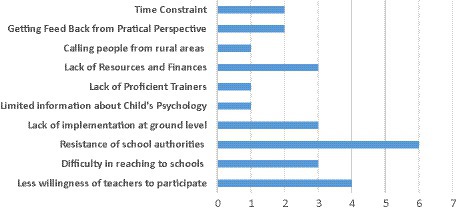

The current study aimed to identify challenges associated with the design, implementation, and execution of behavior management programs for students in Pakistan through teacher training. Figure 1 shows some of the major challenges.

Figure 1. Challenges faced by trainers in Pakistan’s context. Developed by Author. Horizontal Axis-Number of Participants. Vertical Axis-Reported Challenges.

Participants (6 out of 11) in the study pointed out that the biggest challenge related to the implementation of such training comes from school boards that are unwilling to send their teachers to such programs (refer to Figure 1). This could be due to financial constraints or the attitude that they do not understand the importance of such instruction. In addition, many teachers are unwilling to attend such workshops and seem less willing to participate in behavioral training. Lack of financial resources, as highlighted by Arshad and Zamir (2018) and Lindgren et al. (2016), and lack of implementation of what is learned in the classroom, as highlighted by Simonsen et al. (2008) and Dayan et al. (2018) are some of the other major challenges associated with such training programs. Participants also indicated that the trainings are not effective or result in wasted time, whether due to lack of professionalism or irrelevant content that does not consider the psychology of children and adolescents in relation to the practical applications of such trainings. Teachers’ lack of interest in such professional development programs is justified if the systems and outcomes are not conducive or facilitative. In addition, such training programs are usually held in urban areas, although in Pakistan the rural population is larger than the urban population (Alvi, 2018), which makes it difficult for teachers in rural areas to participate in such programs. The lack of professionals and resources, as highlighted by Arshad and Zamir (2018) is also considered a major challenge related to teaching and learning processes.

One component of this study is to find out the perceptions and opinions about such trainings from trainers associated with professional development of teachers. Lochman and Matthys (2017) reported that students have the most direct contact with teachers in the classroom environment and the influences of teaching styles and teacher relationships with students always have an impact on children’s behavior. Researchers further added that teachers have the authority to support the creation of a conducive classroom climate and help establish acceptable behavior norms. The underlying belief behind professional development programs for teachers is that they hold the key to creating a positive school environment by utilizing their skills to mitigate antisocial and aggressive behavior (Strohmeier et al., 2012). Similar ideas were endorsed by Participant I when enquiring about the importance of such trainings:

“It is always important for educators to remember that emotions trigger anger and bullying. Additionally, each child has his own unique response to anger and ways to control it. Teachers should create a classroom with clear, consistent, and flexible boundaries. This will ensure that every student is treated fairly and is subject to the consistent enforcement of a set of rules known and respected by everyone. In order to develop such classrooms, teachers need to be aware of strategies that can help them develop a conducive, holistic environment.”

Pakistan as reported by Rehmani (2006) has a very limited budget to fulfill the demands of education and this is one of the reasons that a teacher’s professional growth is neglected. Furthermore, low economic support and high student to teacher ratios in the classroom increase the chances of poor students’ outcomes and the build-up of non-compliant, antisocial behavior issues (Colder et al., 2006). When participants were asked about the status of professional development in this area all participants agreed that this is an underprivileged sector, ignored by educational authorities and needs immediate attention. Lack of training and competencies among teachers is one of the major reasons for increased aggression and antisocial culture among educational institutes. One trainer suggested that in-house professional development setups are necessary to meet high educational standards. Furthermore, another trainer highlighted the importance of psychological courses and professionals who can help teachers identify and discriminate these behaviors. These professionals can provide guidance on how and when to seek specialist or medical advice for such children. Participant C expressed the importance of such programs:

“Ethics must be part of the curriculum for all kinds of education in schools, colleges and universities and for professional training. Teachers must integrate this into the character traits of their students, should act as an example for them, and regularly reinforce it through their normal daily routine with everyone and in particular with students and their fellow friends.”

Studies have provided empirical evidence indicating that Pakistani school children display a significant rate of emotional, social, and behavioral issues (Naveed et al., 2020). Asad et al. (2017) and Karmaliani et al. (2017) have further supported this observation by highlighting poverty and socialization practices within households as contributing factors to children’s antisocial behavior in Pakistan. One participant expressed that there is a continuous rise in antisocial aggressive behaviors and stated:

“Yes, of course. There is a dire need for introducing such trainings in Pakistan. Being a part of a teacher training department in a school textbook publishing company, while working with different teachers in different schools, I hear their concerns regarding students’ aggressive behavior almost on a daily basis. I am informed every day about new incidents of misbehavior or inappropriate behavior involving students that are more serious than the previous ones.”

According to Hussein and Vostanis (2013), principals and policymakers should also be included in training that prepares teachers to deal with conduct and behavior issues. The participants also agreed that instructing only teachers is not sufficient for them to apply their learnings if school management mindsets are unfavorable and keep teachers overloaded in classrooms. Participant F endorsed the research of Colder et al. (2006), Hooftman et al. (2015), and Day and Hong (2016) and said:

“In workshops and training sessions, I teach them practical techniques and empathize with teachers as they are already under tremendous pressure at school. It is therefore necessary for school owners and administrators to be trained to empathize with teachers.”

In addition, every participant endorsed that managing behaviors can be successfully and quickly achieved through combinations of parents’ management training and through the involvement of schools and teachers because they believe that behavior change requires mutual effort and consistency from both environments. Webster-Stratton et al. (2001) reported details of one of the programs where parents’ training and teacher training were specifically combined for improvement in young children’s behaviors. This training was designed to teach effective discipline strategies, fruitful parenting skills, strategies for coping with stress, and ways to strengthen children’s social skills. This training was to improve the class’s social competence, and it had shown a positive impact on parents’ improved parenting and children’s improved behavior. Furthermore, teacher training influences social competence and the classroom environment in a positive manner. Kazdin (2018) compared the impact of parents’ management training as well as cognitive problem-solving skill training for children on suppressing the level of conduct disorder as well as oppositional defiant behavior. Results indicated that both pieces of training individually or in combination showed a significant improvement in outcome. The authors recommended that parental management trainings produce robust results when used alone or in combination with teacher or individual trainings and have been shown to improve children’s behavior. However, the high budget and the involvement of parents and communities in such trainings require a lot of effort and time from the management side, and that is why low-income and middle-income countries struggle to implement similar trainings.

The present study aims to assess the state of professional development courses for teachers in Pakistan that focus on addressing antisocial behavioral issues among students, and implementing interventions to manage these behaviors. Furthermore, the study identified limitations and challenges associated with these trainings through semi-structured research questionnaire. Persistent antisocial and aggressive behavior in early childhood is a serious problem associated with child delinquencies. Youngsters who start offending in adolescence have two to three times more chances of becoming serious criminals in the future (Burns et al., 2003). Teachers can benefit from professional development opportunities to gain necessary skills to manage challenging antisocial behaviors and behavior problems (Shinde et al., 2018). Therefore, intervention programs for young offenders are recommended.

Based on the demographic questions and written information provided by the participants, it was found that each training had a different origin. Many of the interventions were adopted, adapted, and contextualized using international training modules. Researchers also noted differences in content and topics. The focus of such trainings is on addressing specific behavior changes with different types of activities. However, the real goal of such trainings is to improve teachers’ skills in improving students’ behavior and controlling their antisocial problems. Participant data have also shown that content overlaps between the different training programs. McFarlane et al. (2017) reported that Pakistan is a particularly challenging country for evaluating international interventions because of multiple variations in terms of climate and school culture. Therefore, adopting international trainings and modules for controlling behavior issues in Pakistan is equally effective is questionable. Researchers of the current study also noted that the programs are not evaluated in detail, which does not describe the effectiveness of the programs, which is also considered to be a major weakness. Even after attending rigorous training, Dayan et al. (2018) stated that teachers do not feel skilled and do not implement their learning in the classroom. Hence, it is advisable to incorporate research-based evidence when involving educators in such trainings, which is currently lacking in the professional development courses offered in Pakistan. Teacher-led interventions have been deemed practical and effective, particularly in low- to middle-income countries, due to their cost-effectiveness compared to interventions carried out by external psychologists (Rajaraman et al., 2015). Additionally, teachers’ consistent presence in the classroom throughout the academic year offers students the opportunity to seek assistance whenever they experience or witness antisocial and aggressive behavior. Despite the cost benefits, Shamsi et al. (2019) have highlighted that more than half of the teachers in schools in Pakistan lack sufficient knowledge to address prevalent aggressive issues among students, indicating a need for further attention in this area.

In the questionnaire, questions about the limitations and challenges associated with this type of training, the limited budget of such programs were reported as a major challenge. It has already been pointed that Pakistan spends less than 2% of its GDP on education, compared to the 4 percent of GNP recommended by UNESCO for developing countries (Rehmani, 2006). Due to such circumstances, it is difficult to invest money on behavioral management courses, particularly since the main focus of Pakistan’s educational institutions is on getting better grades and admissions to public universities only (Ahmed et al., 2022). In a similar vein, participants reported that school authorities are not willing to spend their funds, and teachers are not willing to attend since they also have to allocate their finances on travel and sometimes even for their courses. Furthermore, such programs are normally held in urban areas, despite of the fact that Pakistan has a larger rural population than urban ones (Alvi, 2018), which makes it difficult for rural teachers to participate in such programs. Teachers are already overburdened, so participating in such trainings can be challenging because of time constraints too (Day and Hong, 2016; Siddiqui et al., 2022). That is one of the reasons why educators do not want to take on additional responsibilities for attending and implementing trainings in the classroom. Further, Arshad and Zamir (2018) reported that lack of professional trainers hinders educators’ engagement in such trainings, which might be one of the major causes for administrators and educators to be uninterested in such trainings.

During this research study, trainers associated with teacher professional development were also questioned about their perceptions and opinions about trainings aimed at controlling student antisocial behavior issues. The trainers considered the importance of such trainings and suggested that such trainings be integrated into curricula for pre-service and in-service teacher courses. In a country like Pakistan, the field of applied research often overlooks preventive intervention programs aimed at controlling aggression and conduct issues among children (Siddiqui et al., 2021b). Nevertheless, participant responses have strongly indicated the urgent need to rethink and redesign educational and professional development courses in order to effectively address the escalating issue of antisocial aggressive behaviors.

Participants further emphasized that well-designed and properly implemented professional development programs for teachers can effectively mitigate unwanted aggressive behaviors among students, consequently reducing the associated negative consequences on mental health. It has already been reported that in Pakistan there are limited services available to manage mental health problems among children (Hussein and Vostanis, 2013). Thus, as suggested by international studies, school teachers can be successfully trained to reduce the psychological consequences associated with antisocial behaviors (Perfect and Morris, 2011; Webster-Stratton et al., 2012). According to Lochman and Matthys (2017), students have the most direct contact with teachers and the relationship between teachers and students always impacts students’ behavior.

The discussion shows that empirical studies on teacher education need more attention, especially in the Pakistani context, to find out their impact on students’ behavioral control. From the literature review and participants’ responses, a combination of parent management training and teacher training is an urgent need in today’s society. This is to overcome the behavioral problems prevalent in educational institutions. Although some empirical studies on parent management training have been conducted in Pakistan (Mushtaq, 2015), there is still a large gap in research on training teachers alone or a combination of parents and teachers.

The findings of the present study clearly indicate the requirement for empirically tested, advanced-level professional development courses in Pakistan. However, the significant challenge of financial constraints needs to be addressed in order to ensure successful outcomes. But, to overcome financial constraints, NGOs and education promoting agencies must offer free of cost courses to encourage maximum participation from teachers and educators. Moreover, teachers traveling from rural areas to attend sessions should be provided with TA/DA (Travel allowance and Daily Allowance) to bear expenses of traveling and accommodation. As recommended by Flower et al. (2017), teachers need sufficient training in behavior management skills for students with behavior risks and antisocial aggressive behaviors. In addition, participants affirmed the importance of such training programs and suggested that such content be included in teacher education curricula (B.Ed., M.Ed., etc.). In addition, such training should be made mandatory for teachers already working in various settings and struggling with behavior problems in the classroom.

The results of the present study also underscore a significant limitation of professional development courses, which is the lack of empirically tested or research-based outcomes. It is reported that in Pakistan’s educational system most trainings are not empirically tested and authenticated (Rehmani, 2006; Siddiqui et al., 2023). Dayan et al. (2018) reported that even after receiving instructions, teachers feel lacking in expertise to manage classroom antisocial and aggressive behaviors. It shows that developmental programs are not very effective at preparing teachers. Participants also disclosed that trainings do not adequately assist overcome behavioral issues among students, so management and teachers are unwilling to participate in such professional development programs. It is recommended to introduce empirically tested training before inviting the masses to workshops.

For effective instruction, Flower et al. (2017) and Siddiqui and Schultze-Krumbholz (2023) reported that identifying major areas that need focus and implementing evidence-based professional courses can be fruitful after baseline assessments. Moreover, vigorous planning, predicting outcomes, observation of teachers and students and a range of strategies to acknowledge appropriate behaviors and reaction to inappropriate behavior is not seen in current on-going workshops, as proposed by Simonsen et al. (2008). As suggested by Denson (2015) and Dayan et al. (2018) the researchers of the present study recommend that trained teachers have ongoing observations and constant monitoring by a specialist, to ensure that their instructions are effective and result in skill improvement for teachers and improved behavior for students.

It was found that every program follows a different curriculum and not ensuring that these are meeting objectives or not. Furthermore, duration and cost variations are seen (refer to Table 1). Some of the trainings are only for a few hours compared to behavioral trainings designed for teachers in developed countries and which continue for days, weeks, and even months (Lochman et al., 1981; Singh et al., 2003; Denson, 2015; Humphrey et al., 2016). This brings insight as pointed out by Zafar and Ali (2018) that uniformity in the content of such instructions should be applied before preparing teachers for handling aggressive behaviors.

Another significant conclusion derived from the study aligned with the discussion proposed by Zafar and Ali (2018) is that there is no uniform curriculum in Pakistan’s education system nor in teaching and training institutes. Participants also highlighted the argument that every institution offers an independent curriculum at the cost of hurting national unity and harmony. It is a need of time to introduce a uniform evidence-based curriculum for teachers and educators.

Shechtman and Ifargan (2009) found that interventions aimed at multiple groups are more effective than those focused solely on parents, teachers, or children. To address the increase in antisocial behavior among children in Pakistan, it is suggested to implement training programs that involve not only teachers but also parents and the community. Empirical research should also be conducted to accurately assess the effectiveness of such interventions. In Pakistan, the national language and language of instruction in most educational institutions is Urdu; therefore, for evidence-based research, it is recommended that tools developed, adopted or adapted in the local language be used to facilitate instructors and children to provide accurate data according to Siddiqui et al. (2021b).

In spite of the fact that the current study shed some light on the nature of professional development courses for teachers in metropolises of Pakistan, it is important to acknowledge that there are some limitations to this study. The study has limited scope as the trainers provided information were Karachi based, however, some of the trainers were frequently traveling in other regions in Pakistan to deliver their courses, however this study does not truly represent other regions specifically and therefore cannot be generalized. Therefore, further studies are necessary to explore more details about such professional development courses in other regions. The study is limited by its small sample size also. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the subject, it is suggested that additional teacher trainers from other regions be contacted in the future. Additionally, the results are based solely on self-reports from trainers and do not include other occupational groups. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of such courses, it is recommended to involve multiple participants, including administrators or teachers who have attended these courses.

Despite the efforts made by the Higher Education Commission to enhance the educational system in Pakistan, there is a significant lack of attention and research dedicated to professional development courses or training programs aimed at equipping teachers with the necessary skills to handle behavioral issues, especially in the Pakistani context. Although a few private institutions do offer some training, there is no research-based evidence to prove their effectiveness, and the limited number of participants suggests that the majority of teachers and trainers are not engaged in such programs. As a researcher, we could not find many trainers responsible for conducting such training sessions, and it is worth noting that they hail from various institutions, not just one. This research is the first of its kind in Pakistan, albeit less comprehensive, aimed at evaluating the status of training programs designed to address behavioral and antisocial issues through professional development courses for teachers. This research will create new avenues for educators and researchers to design effective training programs and evaluate their outcomes.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Department, Iqra University, Karachi. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SS and AK: conceptualization. SS: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, and funding acquisition. AK: validation, supervision, and project administration. SS and MK: investigation. MK: resources and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The researchers acknowledge the support from the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of TU Berlin.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmed, B., Yousaf, F. N., Ahmad, A., Zohra, T., and Ullah, W. (2022). Bullying in educational institutions: college students’ experiences. Psychol. Health Med. 1–7. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2022.2067338

Alvi, M. H. (2018). Difference in the population size between rural and urban areas of Pakistan. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, 1–3. Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/90054

Amin, R., Iqbal, A., Naeem, F., and Irfan, M. (2020). Effectiveness of a culturally adapted cognitive behavioural therapy-based guided self-help (CACBT-GSH) intervention to reduce social anxiety and enhance self-esteem in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial from Pakistan. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 48, 503–514. doi: 10.1017/S1352465820000284

Arshad, M., and Zamir, S. (2018). Situational analysis of early childhood education in Pakistan: challenges and solutions. J Early Childhood Care Educ 2, 135–149. doi: 10.30971/jecce.v2i.505

Asad, N., Karmaliani, R., McFarlane, J., Bhamani, S. S., Somani, Y., Chirwa, E., et al. (2017). The intersection of adolescent depression and peer violence: baseline results from a randomized controlled trial of 1752 youth in Pakistan. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 22, 232–241. doi: 10.1111/camh.12249

Asif, A. (2016). Relationship between bullying and behavior problems (anxiety, depression, stress) among adolescence: Impact on academic performance. Edmond: MedCrave Group LLC.

Azam, F., Omar Fauzee, M. S., and Daud, Y. (2014). A cursory review of the importance of teacher training: A case study of Pakistan. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 21, 912–917. doi: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2014.21.06.21574

Barlas, N. S., Sidhu, J., and Li, C. (2022). Can social-emotional learning programs be adapted to schools in Pakistan? A literature review. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 10, 155–169. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1850374

Barlett, C. P., and Anderson, C. A. (2011). Reappraising the situation and its impact on aggressive behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 1564–1573. doi: 10.1177/01461672114236

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., and Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16, 351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534

Boud, D., Cohen, R., and Walker, D. (1997) Using experience for learning. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Bubb, S. (2014). Successful Induction for New Teachers: A Guide for NQTs & Induction Tutors, Coordinators and Mentors. SAGE Publications Ltd (CA).

Burns, B. J., Howell, J. C., Wiig, J. K., Augimeri, L. K., Welsh, B. C., Loeber, R., et al. (2003). “Treatment, services, and intervention programs for child delinquents,” in Child Delinquency Bulletin Series. Washington DC, USA: US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Bushman, B. J., and Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 219–229. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219

Chiumento, A., Hamdani, S. U., Khan, M. N., Dawson, K., Bryant, R. A., Sijbrandij, M., et al. (2017). Evaluating effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a group psychological intervention using cognitive behavioural strategies for women with common mental disorders in conflict-affected rural Pakistan: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 18, 190–112. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1905-8

Colder, C. R., Lengua, L. J., Fite, P. J., Mott, J. A., and Bush, N. R. (2006). Temperament in context: infant temperament moderates the relationship between perceived neighborhood quality and behavior problems. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 27, 456–467. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.06.004

Corsini, R. (2007). Corsini's individual education: A democratic model. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 11, 247–252. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.11.4.247

Day, C., and Hong, J. (2016). Influences on the capacities for emotional resilience of teachers in schools serving disadvantaged urban communities: challenges of living on the edge. Teach. Teach. Educ. 59, 115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.015

Dayan, U., Perveen, S., and Khan, M. I. (2018). Transition from pre-service training to classroom: experiences and challenges of novice teachers in Pakistan. FWU J Soc Sci 12, 48–59.

Denson, T. F. (2015). Four promising psychological interventions for reducing reactive aggression. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 3, 136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.04.003

Dodge, K. A. (2006). Professionalizing the practice of public policy in the prevention of violence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 34, 475–479. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9040-0

Eninger, L., Ferrer-Wreder, L., Eichas, K., Olsson, T. M., Hau, H. G., Allodi, M. W., et al. (2021). A cluster randomized trial of promoting alternative thinking strategies (PATHS®) with Swedish preschool children. Front. Psychol. 12:695288. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.695288

Ferrer-Cascales, R., Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Sánchez-SanSegundo, M., Portilla-Tamarit, I., Lordan, O., and Ruiz-Robledillo, N. (2019). Effectiveness of the TEI program for bullying and cyberbullying reduction and school climate improvement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:580. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040580

Flower, A., McKenna, J. W., and Haring, C. D. (2017). Behavior and classroom management: are teacher preparation programs really preparing our teachers? Prevent School Fail 61, 163–169. doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2016.1231109

Giraldi, T. (2019). “What is mindfulness?” in Psychotherapy, Mindfulness and Buddhist Meditation (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 13–35.

Glancy, G., and Saini, M. A. (2005). An evidenced-based review of psychological treatments of anger and aggression. Brief Treat Cris Intervent 5, 229–248. doi: 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi013

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., O'Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., et al. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. Am. Psychol. 58, 466–474. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.466

Gross, J. J., and Thompson, R. A. (2007). “Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations” in Handbook of Emotion Regulation. ed. J. J. Gross. Newyork City, USA: Guilford Publications, 3–24.

Hakim, F., and Shah, S. A. (2017). Investigation of bullying controlling strategies by primary school teachers at district Haripur. Peshawar J Psychol Behav Sci 3, 165–174. doi: 10.32879/pjpbs.2017.3.2.165-174

Hastings, R. P., and Bham, M. S. (2003). The relationship between student behaviour patterns and teacher burnout. Sch. Psychol. Int. 24, 115–127. doi: 10.1177/01430343030240019

Hemphill, S. A., McMorris, B. J., Toumbourou, J. W., Herrenkohl, T. I., Catalano, R. F., and Mathers, M. (2007). Rates of student-reported antisocial behavior, school suspensions, and arrests in Victoria, Australia and Washington state, United States. J. Sch. Health 77, 303–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00211.x

Hooftman, W. E., Mars, G. M. J., Janssen, B., De Vroome, E. M. M., and Van den Bossche, S. N. J. (2015). Nationale Enquête Arbeidsomstandigheden 2014. Methodologie en globale resultaten.

Horne, A. M., Stoddard, J. L., and Bell, C. D. (2007). Group approaches to reducing aggression and bullying in school. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 11, 262–271. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.11.4.262

Humphrey, N., Barlow, A., Wigelsworth, M., Lendrum, A., Pert, K., Joyce, C., et al. (2016). A cluster randomized controlled trial of the promoting alternative thinking strategies (PATHS) curriculum. J. Sch. Psychol. 58, 73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2016.07.002

Hussein, S. A., and Vostanis, P. (2013). Teacher training intervention for early identification of common child mental health problems in Pakistan. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 18, 284–296. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2013.819254

Jumani, N. B., and Abbasi, F. (2015). Teacher education for sustainability in Pakistan. J. Innov Sustain 6, 13–19. doi: 10.24212/2179-3565.2015v6i1p13-19

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 10, 144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Karmaliani, R., Mcfarlane, J., Somani, R., Khuwaja, H. M. A., Bhamani, S. S., Ali, T. S., et al. (2017). Peer violence perpetration and victimization: prevalence, associated factors and pathways among 1752 sixth grade boys and girls in schools in Pakistan. PLoS One 12:e0180833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180833

Kazdin, A. E. (2018). Implementation and evaluation of treatments for children and adolescents with conduct problems: findings, challenges, and future directions. Psychother. Res. 28, 3–17. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1208374

Khawaja, S., Khoja, A., and Motwani, K. (2015). Abuse among school going adolescents in three major cities of Pakistan: is it associated with school performances and mood disorders? J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 65, 142–147.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., and Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 140, 1073–1137. doi: 10.1037/a0035618

Lindgren, S., Wacker, D., Suess, A., Schieltz, K., Pelzel, K., Kopelman, T., et al. (2016). Telehealth and autism: treating challenging behavior at lower cost. Pediatrics 137, S167–S175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2851O

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., and Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the internet: the perspective of European children. Full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids online survey of 9-16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. EU Kids Online, Deliverable D4. EU Kids Online Network, London, UK.

Lochman, J. E., and Matthys, W. (2017). The Wiley handbook of and impulse-control disorders. NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Lochman, J. E., Nelson, W. M. III, and Sims, J. P. (1981). A cognitive behavioral program for use with aggressive children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 10, 146–148. doi: 10.1080/15374418109533036

Loeber, R. (2003). Child delinquency: Early intervention and prevention. Washington DC, USA: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Lovett, S. (2002). Teacher learning and development in primary schools: A view gained through the National Education Monitoring Project. Doctoral thesis. University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

Luiselli, J. K., Putnam, R. F., Handler, M. W., and Feinberg, A. B. (2005). Whole-school positive behaviour support: effects on student discipline problems and academic performance. Educ. Psychol. 25, 183–198. doi: 10.1080/0144341042000301265

Magsi, H., Agha, N., and Magsi, I. (2017). Understanding cyber bullying in Pakistani context: causes and effects on young female university students in Sindh Province. New Horiz. 11, 103–110.

Maharjan, S. (2012). Association between work motivation and job satisfaction of college teachers. Admin Manage Rev 24, 45–55.

Mahr, F., McLachlan, N., Friedberg, R. D., Mahr, S., and Pearl, A. M. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of a second-generation child of Pakistani descent: Ethnocultural and clinical considerations. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 20, 134–147. doi: 10.1177/1359104513499766

Maryam, U., and Ijaz, T. (2019). Efficacy of a school based intervention plan for victims of bullying e – Academia, 206–216. Malaysia: Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Terengganu.

McFarlane, J., Karmaliani, R., Khuwaja, H. M. A., Gulzar, S., Somani, R., Ali, T. S., et al. (2017). Preventing peer violence against children: methods and baseline data of a cluster randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. Glob Health 5, 115–137. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00215

McGee, T. R., Hayatbakhsh, M. R., Bor, W., Cerruto, M., Dean, A., Alati, R., et al. (2011). Antisocial behaviour across the life course: an examination of the effects of early onset desistence and early onset persistent antisocial behaviour in adulthood. Aust. J. Psychol. 63, 44–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-9536.2011.00006.x

McGuire, J. (2002). Integrating findings from research reviews. Offender rehabilitation and treatment: Effective programmes and policies to reduce re-offending. NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 3–38.

McGuire, J. (2008). A review of effective interventions for reducing aggression and violence. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 363, 2577–2597. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0035

McKenna, J. W., Muething, C., Flower, A., Bryant, D. P., and Bryant, B. (2015). Use and relationships among effective practices in co-taught inclusive high school classrooms. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 19, 53–70. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.906665

Mirza, M., Azmat, S., and Malik, S. (2020). A comparative study of cyber bullying among online and conventional students of higher education institutions in Pakistan. J Educ Sci Res 7, 87–100.

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., and Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 7, 60–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Moutiaga, S., and Papavassiliou-Alexiou, I. (2021). Developing a teacher training model in managing student behavior. J. Educ. Hum. Dev. 10, 34–47. doi: 10.15640/jehd.v10n4a4

Mulenga, I. M. (2020). Teacher education versus teacher training: epistemic practices and appropriate application of both terminologies. J Lexicograph Terminol 4, 105–126.

Musharraf, S., and Anis-ul-Haque, M. (2018). Impact of cyber aggression and cyber victimization on mental health and well-being of Pakistani young adults: the moderating role of gender. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 27, 942–958. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1422838

Mushtaq, A. (2015). Reducing aggression in children through a school-based coping power program. Doctoral dissertation. Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad.

Naveed, S., Waqas, A., Shah, Z., Ahmad, W., Wasim, M., Rasheed, J., et al. (2020). Trends in bullying and emotional and behavioral difficulties among Pakistani schoolchildren: A cross-sectional survey of seven cities. Front. Psych. 10:976. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00976

Nemati, E., Habibi, M., Ahmadian Vargahan, F., Soltan Mohamadloo, S., and Ghanbari, S. (2017). The role of mindfulness and spiritual intelligence in students' mental health. J Res Health 7, 594–602. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.jrh.7.1.594

Nook, E. C., Vidal Bustamante, C. M., Cho, H. Y., and Somerville, L. H. (2020). Use of linguistic distancing and cognitive reappraisal strategies during emotion regulation in children, adolescents, and young adults. Emotion 20, 525–540. doi: 10.1037/emo0000570

Oaten, M., and Cheng, K. (2006). Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. Br. J. Health Psychol. 11, 717–733. doi: 10.1348/135910706X96481

Olweus, D., and Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus bullying prevention program. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 80, 124–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

Perfect, M. M., and Morris, R. J. (2011). Delivering school-based mental health services by school psychologists: education, training, and ethical issues. Psychol. Sch. 48, 1049–1063. doi: 10.1002/pits.20612

Peterson, C. (1988). Explanatory style as a risk factor for illness. Cogn. Ther. Res. 12, 119–132. doi: 10.1007/BF01204926

Polaschek, D. L., Wilson, N. J., Townsend, M. R., and Daly, L. R. (2005). Cognitive-behavioral rehabilitation for high-risk violent offenders: an outcome evaluation of the violence prevention unit. J. Interpers. Violence 20, 1611–1627. doi: 10.1177/0886260505280507

Prestridge, S. (2010). ICT professional development for teachers in online forums: analysing the role of discussion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.04.004

Preuss, H., Capito, K., van Eickels, R. L., Zemp, M., and Kolar, D. R. (2021). Cognitive reappraisal and self-compassion as emotion regulation strategies for parents during COVID-19: an online randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 24:100388. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100388

Qureshi, N., and Kalsoom, Q. (2022). “Teacher education in Pakistan: structure, problems, and opportunities” in Handbook of research on teacher education. eds. M. S. Khine and Y. Liu (Singapore: Springer)

Rafi, M. S. (2019). Cyberbullying in Pakistan: positioning the aggressor, victim, and bystander. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 34, 601–620. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3827661

Rajaraman, D., Khandeparkar, P., Chatterjee, A., and Patel, V. (2015). “The SHAPE programme” in School health promotion: Case studies from India. eds. R. Divya, S. Sachin, and P. Vikram (Byword Books), 14–44.

Ramzan, N., and Amjad, N. (2017). Cross cultural variation in emotion regulation: A systematic review. Annals King Edward Med Univ 23:1512. doi: 10.21649/akemu.v23i1.1512

Rappaport, N., and Thomas, C. (2004). Recent research findings on aggressive and violent behavior in youth: implications for clinical assessment and intervention. J. Adolesc. Health 35, 260–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.009

Rehmani, A. (2006). Teacher education in Pakistan with particular reference to teachers' conceptions of teaching. Qual Educ 20, 495–524.

Saleem, S., Khan, N. F., and Zafar, S. (2021). Prevalence of cyberbullying victimization among Pakistani youth. Technol. Soc. 65:101577. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101577

Shakeel, Q. (2018). Cybercrime reports hit a record high in 2018: FIA. Available at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1440854