95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 02 May 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1175123

This article is part of the Research Topic Linking Past, Present and Future: the Development of Historical Thinking and Historical Competencies Across Different Levels of Education View all 5 articles

Twenty-first century education is firmly committed to training young people in new competencies that are transferable to a variety of life situations. Historical thinking as a methodological theory is emerging in a large number of countries. In thinking historically, the skills of the historians are used, so that the sources of the past can be interpreted and the generation of effective historical narratives can be enhanced. This study aims to compare the general perception of the teaching of history between two groups of baccalaureate students, with respect to the effectiveness and transferability of learning historical thinking. Specifically, the existing perception of the implementation of historical thinking competencies is collected after the pre- and post-evaluation of a unit plan developed with 93 students. A quantitative method was used, namely a quasi-experimental design with a non-equivalent control group. The results indicate a substantial improvement in the responses observed in the experimental group, compared to those obtained in the control group. This impact is associated with the didactic methodology implemented with both groups, which showed notable changes in the perception of the theory of historical thinking, as well as in the use of other digital resources and active methods. For the future, it is imperative to transfer these first indications to controlled evaluations of academic outcomes to consolidate the academic status of competency-based teaching in secondary education levels.

The twenty-first century continues to stage the traditional difficulties of the didactics of history, whose epistemological and methodological deficits keep it from establishing its own personality as a discipline. The art of teaching is halfway between the discipline of history and the field of education, which is closer to pedagogy and psychology, whose research background is much broader (Miralles and Rodríguez, 2015), with all that this entails. It is also necessary to assess the limitations deriving from a legislative framework that -despite the din that continues to be caused by the imposition of successive and conflicting education laws, depending on the political spectrum- has continued to cultivate the history of our national past, which is why it is not easy to separate didactics from the essentialist and identity-based contents of yesteryear (Carretero, 2019).

Attempts to democratize the discipline have only been partially successful, as the curricula still have a strong magisterial, monotonous and unidirectional tendency, marked in practice by stereotypes and nationalist vices. In the task of promoting historical facts and evidence in order to facilitate the temporal connection between the past and the present, it is necessary to teach the procedures used by the historian, as well as to deepen the knowledge that science has left in this respect, which, by the way, also relies on the sources as an epistemological substratum of the first order. In order to bring this practice to the school environment, today’s history teacher must be trained in a series of competencies that link the past with the construction that has been made of it, questioning, improving and understanding it. In recent years, with the advent of technology, new initiatives have emerged in the field of innovation, with interesting projects carried out from the perspective of gamification and other active learning methods, also amplified thanks to the growth of social networks and new online dissemination platforms.

This contribution aims to bring to the table evidence related to methodological change in history classes. Starting from the reality of the classroom, different training proposals are implemented for two groups of students, in order to contrast their perceptions, according to the methods, technologies and theoretical approaches adopted. Theory and practice merge in an attempt to perpetuate another form of teaching history, based on the theory of historical thinking, setting a course for those professionals who wish to modify their didactic idiosyncrasies.

History as a school subject emerged in the 19th century in almost all Western countries as a result of the political and social interest in the historiography of the time, linked to the construction and development of the nation-states of liberal-bourgeois society, whose most relevant premise was the ideologization of the defense of the nation before society, transmitting heroic achievements, glorious deeds and patriotic feelings (Prats, 2016; Ibagón and Miralles, 2021).

There is no doubt that the recognition and glorification of the past (illustrious and oppressive), have acted as a cultural and political axis, giving rise to a traditional, disciplinary and imposing teaching of history, tending to idolize the dominant thoughts of the nation, in a tyrannical exercise of a markedly indoctrinating character. In fact, through a predetermined plot, limited to legendary events and characters, the discipline was reduced to a historicist and teleological narrative, in which the immutable values of the nation were instilled, which the students of the time had to know, appreciate and defend. A good example of this are the famous general history textbooks, so common in baccalaureate teaching since the 19th century (Parra-Monserrat et al., 2021). At that time, a restrictive and conservative teaching was then reproduced, based on a masterly lesson that promoted an alienating logic (Borries, 2018), suppressing the personality, and in which history assumed a role of national knowledge, consolidating the achievements of yesteryear; it is what Miralles and Gómez (2017) call “identity emotionality of Romanticism” (p. 10); that is, the Romantic objectives for the teaching of history, based on the construction of that cultural and national identity (Carretero, 2019), even in the European context (Berger and Conrad, 2015). In recent years, history -understood as a school subject- has been lost amidst the changing political curricula, under the prism of an educational social science which has meant nothing more than a syncretic cocktail far removed from the true structure and joint development of the social sciences (Prats-Cuevas et al., 2021). There can be no doubt that a reformulation of the concept of historical education is the great objective of the 21st century, avoiding the identity-based nuances that have held back the development of the discipline. It is necessary to opt for a readaptation of content which, without moving away from historiographical knowledge, takes more account of the functioning of social reality and the sensitivities surrounding what is common.

Several well-known authors (Sáiz and López Facal, 2016; Gómez and Miralles, 2017; Miralles and Gómez, 2017) argue that the teaching of history in recent years continues to be traditional, and is based on the inert transmission of information, the almost exclusive use of the textbook and the memorization of content, as it is not committed to a methodology that promotes civic values or fosters critical thinking. Students rely on the memorization of empty names and dates. It is a fact that learner-centered teaching methods and strategies encourage critical and reflective thinking and are better valued even by teachers (Sánchez et al., 2020). Therefore, there is a need for another didactic view on the responsibilities given to learners, an alternative methodological perspective.

Emerging methodologies offer great advantages to students. The use of active methods (case studies, project-based learning, problem-based learning or challenge-based learning, service learning, flipped classroom, gamification, empathic simulations, or didactic itineraries, among others), cooperative techniques (Aronson’s puzzle, wheel request, shared whiteboard, inside-outside circle, etc.) and even alternative dynamics, such as invisible learning, expanded learning or multiple literacies, offer enormous possibilities. But above all, they favor the implementation of new educational trends, innovative connections, practical and efficient reflections, as well as current communication tools at the service of learning (Gértrudix, 2016). It is imperative to reinforce a social sciences teaching and historical education focused on competencies, which implements strategies and approaches adapted to the most current innovations, and applies active learning methodologies (Gómez et al., 2020), understanding that these offer a real alternative to dynamize and modernize educational processes. On the other hand, the combination of technology and active methods is a necessity of the first order in the search for a more practical history that overcomes the static conception of the past. In fact, many of the tools available in the classroom today are the result of the implementation of technologies that have become commonplace because they are within everyone’s reach and accepted by society. Therefore, it is necessary to define new ways of approaching learning as a process in which technology mediates and favors the creation of synergies that go beyond the available resources (Sánchez-García and Toledo-Morales, 2017). In this sense, the involvement of school leaders with a closer presence in pedagogical activities that demand a useful use of these technological resources is elemental (Claro et al., 2017).

In order to establish historical learning, a key axis is the epistemological and methodological construction, articulating cognitive skills that allow rethinking history, questioning past events and building knowledge that facilitates the understanding of the world through complex processes of a procedural nature. An honest professional exercise with historiography is necessary, which overcomes didactic traditionalism and develops competences that provide an active role for students, creating a reciprocal link between the past and the present, in order to promote a critical and socially discussed epistemological construction (López-García, 2018), introducing students to the multiperspective and interpretative nature of history (Kolikant and Pollack, 2019). In light of this reflection, it is worth asking a starting question: is transmissive and disciplinary teaching an unbridgeable gap? The answer is obvious, and the key lies in the methodological way.

When speaking methodologically about historical thinking, it is worth remembering that this concept is not new, since it emerged with the American Historical Association at the end of the 19th century, with the intention of promoting the critical role of thinking about history in public life (Lévesque, 2011). From this point, two major research approaches need to be identified. On the one hand, the concept of historical thinking associated with the Anglo-Saxon context of the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom (Chapman, 2011; VanSledright, 2013; Wineburg et al., 2013; Monte-Sano et al., 2014; Cooper, 2017); on the other, that of historical consciousness, originating in Central Europe - especially in the German context - and extended to the Portuguese-speaking world (Duquette, 2015; Gago, 2016; Körber, 2017; Rüsen, 2004). Nor should we forget the influence of the Asian context, where World War II, occupation, colonialism, or the emergence of states integrated into the global knowledge economy, have shaped the history being taught in East and Southeast Asia, emphasizing national trauma, victimhood and humiliation, Asian “Confucian” values, and the moralizing function of didactics, concretized in the complex development of national identity (Baildon and Afandi, 2018).

This article develops the Anglo-Saxon approach which, derived from the initial work of Dickinson et al. (1984, 1995), has its greatest splendor in the theses put forward in the Historical Thinking Project, led by Peter Seixas. From this perspective, historical thinking is the creative process carried out by historians to interpret the sources of the past and generate historical narratives (Seixas and Morton, 2013). For its development, it must work with six key concepts: historical relevance, historical evidence, change and continuity, causes and consequences, historical perspective and the ethical dimension of history. Although they may seem like concepts, the reason they are so generative is that they function particularly as problems, tensions or difficulties to be solved, which require students to understand, negotiate and, ultimately, an implicit effort to construct and shape history, articulating competencies and productive ways out of the conflicts generated (Seixas, 2017). This understanding of thinking about the past has implications for learning the discipline of History. Factual or substantive concepts about the past (knowing what happened) are relevant, but they rely on the simplicity of memory. In contrast, historical thinking is based on the complexity of historical processes (understanding and interpreting how and why we know what happened), i.e., it promotes historians’ methods and ways of working (Domínguez et al., 2017). In other words, it focuses on synthesis, interpretation, the ability to make reflective judgments based on criticism, and building bridges to connect the past with the present (Ginting et al., 2020).

Another way of thinking historically closely related to this stream is that which promotes the concept of historical reasoning (Van Boxtel and Van Drie, 2018; Grever and Van Nieuwenhuyse, 2020; Gestsdóttir et al., 2021) as a task to improve the understanding of facts, situations, people and events that occurred in the past, which facilitates the deconstruction of historical representations that can be found in society or in the media, the analysis of current problems, as well as the reflection on the consequences - intended or unintended - left by human actions. This idea has also been pointed out by Lévesque (2023) from another point of view, with which to promote the construction of narratives or accounts open to deconstruction and reconstruction through innovative approaches and relevant questions. Some studies (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2019; Chaparro et al., 2020) evidence the recent rise of historical thinking, as well as the work with analytical and procedural concepts. Indeed, outstanding research has been carried out on historical relevance (Egea and Arias, 2018), historical empathy (Bartelds et al., 2020), chronology, evidence, interpretation and imagination (Puteh et al., 2010), sources (Solé and Llonch, 2016; Van Nieuwenhuyse, 2016) or historical awareness (Fronza, 2019), among others.

As for the Secondary Education and Baccalaureate stages, the recent research carried out by the University of Murcia (Rodríguez-Medina et al., 2020; Gómez et al., 2021a,b), in which the main results of a didactic intervention with 473 students are presented, should be highlighted. After implementing several units plan based on historical thinking skills in these stages, including changes in the teaching methodology, these studies yielded results with advances in terms of methodology, motivation, satisfaction and transfer of historical knowledge, highlighting very relevant issues, such as the ability to interpret historical documents and primary sources, the ability to debate current issues, or the self-perception of learning the main historical facts and characters, as well as in relation to the causality of historical events, and the changes and permanence left by the evolution of history.

In short, in order to develop historical thinking in secondary classrooms, it is essential that history teachers have solid training in what it means to think historically, to understand the past in order to teach it and make it accessible, and to look for markers of knowledge progression (Guerrero et al., 2019). This should be the strength from which young students’ learning starts. These markers should start from knowledge of the classroom context, to observe how students, as a whole, understand or value the instruction they receive. This is what is done in this work, focusing on the baccalaureate stage, whose methodology and results are presented in the following sections.

The aim of this study is to compare the general perceptions of History teaching among two groups of baccalaureate students in relation to the effectiveness and transferability of learning historical thinking. Specifically, the existing perceptions on the application of historical thinking competencies will be collected after the pre- and post-evaluation of a unit plan implemented with 93 students. This objective will be further developed into two more specific objectives.

1. To describe the initial perception of the teaching of history in relation to the processes of efficacy and transfer in baccalaureate students, globally and by gender.

2. To describe and compare the final perception of history teaching in relation to the processes of efficacy and transfer in baccalaureate students, globally, by gender and according to the research group.

In order to achieve the objectives of this research, a quantitative method was used, specifically a quasi-experimental design with a non-equivalent control group (Campbell and Stanley, 1973). During the course of the study, 93 first-year Baccalaureate students from three secondary schools in the Region of Murcia (Spain) participated, following a non-probabilistic sampling procedure (McMillan and Schumacher, 2005). Table 1 shows the exact distribution of the participants.

An adaptation of the questionnaire designed and validated by Rodríguez-Medina et al. (2020) was used to collect information. The original titles of the questionnaire are “Secondary school students’ opinions about history classes” (pretest version) and “Secondary school students’ opinions about the implementation of the history unit” (posttest version).

Since this instrument is an adaptation of another questionnaire, its psychometric properties were calculated. Regarding reliability, the pretest obtained an alpha coefficient of 0.896, while in the posttest this value was 0.918, both values considered highly reliable (McMillan and Schumacher, 2005). Regarding the construct validity of the instrument, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin adequacy index (KMO) was calculated for the pretest and posttest, with results of 0.802 and 0.885, respectively. These results allowed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to be performed. After factoring the matrix, nine components with an eigenvalue greater than one explained 69.64% of the total variance in the pretest, and seven factors explained 72.28% of the total variance in the posttest. Thus, once the psychometric properties have been analyzed, it can be affirmed that they are adequate to collect valid and reliable information with which to respond to the objectives set.

Twelve items are analyzed, which are the same in the pretest and the posttest. The difference between the two is that the first version only analyses the students’ perception of the history teaching received so far, while the second version analyses the perception of the actual implementation of the training unit applied in this study. Broadly speaking, information is collected on historical competences, as well as questions on history education, democratic citizenship and the use of technology. These are questions whose content is articulated around the effective learning of history, which can be extrapolated or transferred to real-life situations and, therefore, prepares for exercising citizenship in a responsible way.

After collecting the initial information through the pretest, two different unit plans were implemented with both groups. Both the experimental group and the control group were taught World War II as a thematic unit. However, the first group was taught a topic that combined digital resources, active methods and an epistemological approach through a methodology based on the theory of historical thinking, giving the students a leading role throughout all the sessions, so that they were an active part of the process. On the other hand, in the control group, a traditional unit was taught, based on the sole protagonism of the teacher, on note-taking and on the predominance of the textbook, developing passive learning, of a disciplinary nature.

Although the contents developed were identical, it is important to point out the previous work carried out in the design of the alternative unit plan, whose active essence implied a much more complex previous elaboration than the unit applied with the control group, in terms of creation of work materials, compilation of historical sources, preparation of activities, exercises and tasks, debates, video and image editing processes, downloading of software tools, preparation and uploading of materials, computer compatibility, etc. The procedure designed was in accordance with the ethical standards of research and was positively evaluated by the ethics committee of the University of Murcia.

The process of responding to the objectives began by performing a normality test on each of the instruments. Taking into account that this research had 93 participants, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic was applied, since the number of participants was greater than 50, with a confidence interval of 95%. Once the exploratory analysis was performed, it was found that the distribution was not normal (p < 0.05) for any item of the instrument, both in the pretest and posttest. For this reason, the null or homogeneity hypothesis was rejected and the alternative or difference hypothesis was accepted, thus justifying the use of nonparametric statistics in the development of this research.

The Cronbach’s alpha item covariation method was used to calculate reliability. For construct validity, a global factor analysis was performed with principal component analysis (PCA), with quartimax orthogonal rotation and eigenvalues (eigenvalues) greater than one. Beforehand, the adequacy of the data obtained in the instrument was checked using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy index. Finally, to determine the perception of the teaching of history in the experimental and control groups, descriptive analyses based on frequencies and percentages were carried out at the global level and according to gender and research group. To compare the variable gender and research group, the Mann–Whitney U statistic was used, since in non-parametric statistics it is the most commonly used to analyze differences between two independent groups.

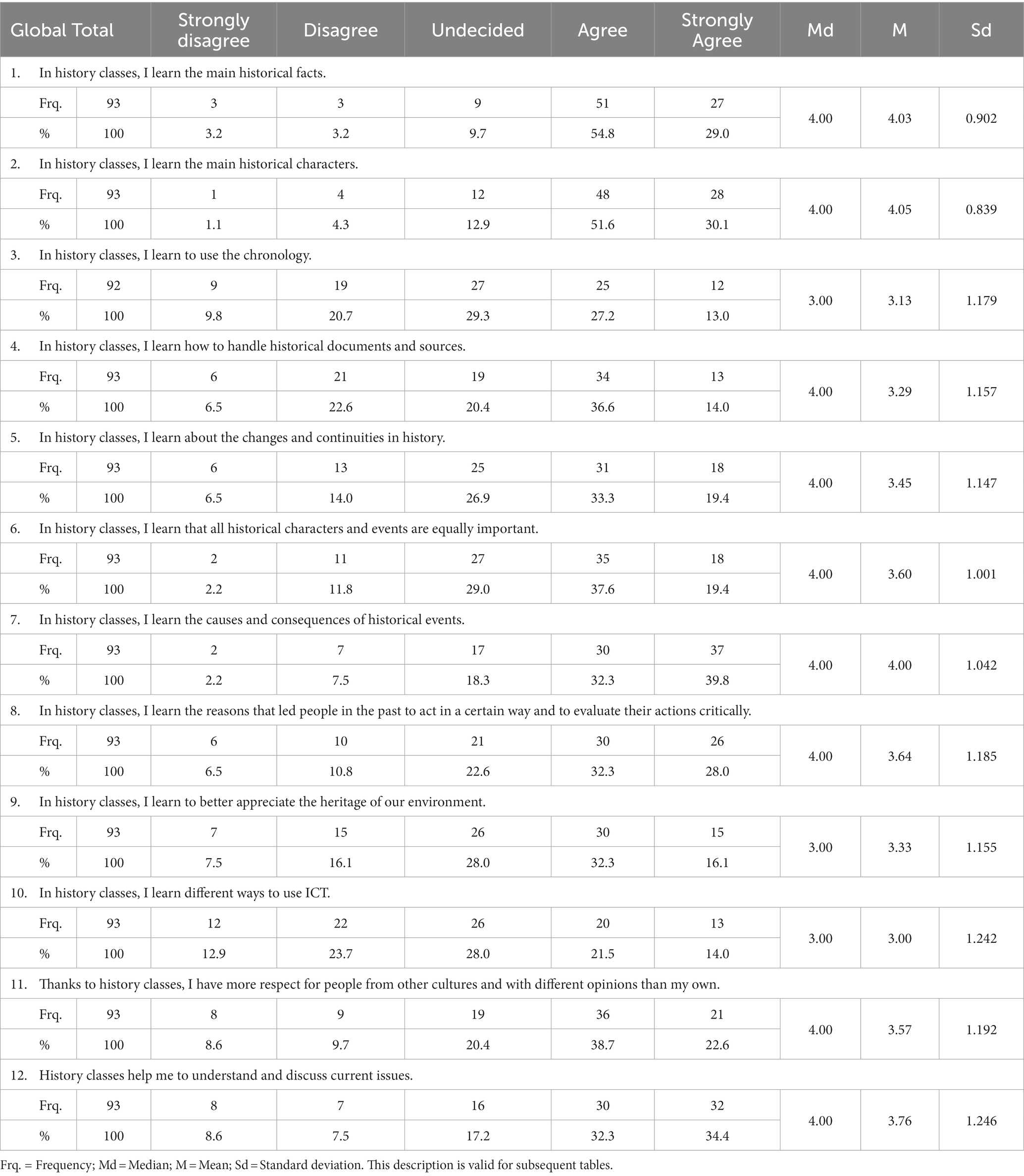

With regard to specific objective 1 (SO1), which refers to describing the initial perception of history teaching in the processes of effectiveness and transfer of learning on the part of baccalaureate students, globally and according to the gender of the participants, Table 2 presents the main results in global terms.

Table 2. Initial perceptions of teaching in terms of effectiveness and transfer of learning at the global level.

According to Table 2, the results of least acceptance of the statements were in item 3, in which 30.5% of the students disagreed or strongly disagreed that they learn to use chronology in History classes, and in item 10, in which 36.6% of cases denied that they learn different ways of using ICT in History classes. On the other hand, items in which students were undecided also stand out, such as item 3 (29.3%), item 5 (26.9%), item 6 (29%), and items 9 and 10 (28%). The statement made in item 6 stands out in particular, with 58% of adolescents who think that in history classes they learn that all historical figures and events are equally important. The highest rated items are item 1, where 83.8% agree or strongly agree with the statement that in history lessons they usually learn the main historical events, item 2, where 81.7% of the students agree that in history lessons they usually learn the main historical figures, and item 7, where 72.1% of the participants recognize that in history lessons they usually learn the causes and consequences of historical events.

These results are confirmed by the median, which is 3.00 points for items 3, 9 and 10, and 4.00 points out of 5.00 for the rest of the items, which means that in 9 out of the 12 items analyzed, more than 50% of the participants agreed or strongly agreed with the sentence stated in these items. In turn, the means show a trend ranging from item 10 (M = 3.00; Sd = 1.242), which has the lowest mean score, to item 2 (M = 4.00; Sd = 0.839), which represents the highest mean response. Apart from item 10, the items with the lowest mean values are item 3 (M = 3.13; Sd = 1.179), which refers to the use of chronology in history lessons, and item 9 (M = 3.33; Sd = 1.155), which states that history lessons serve to learn to better appreciate the heritage of our environment. The highest mean values are found in item 1 (M = 4.03; Sd = 0.902), item 2 (M = 4.05; Sd = 0.839) and item 7 (M = 4.00; Sd = 1.042), following the pattern of the percentages shown.

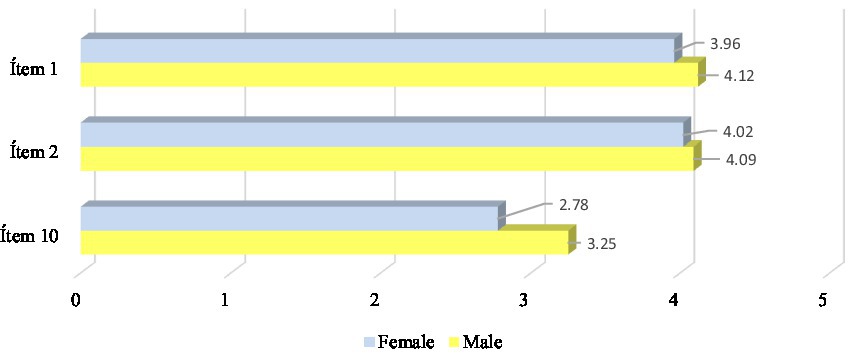

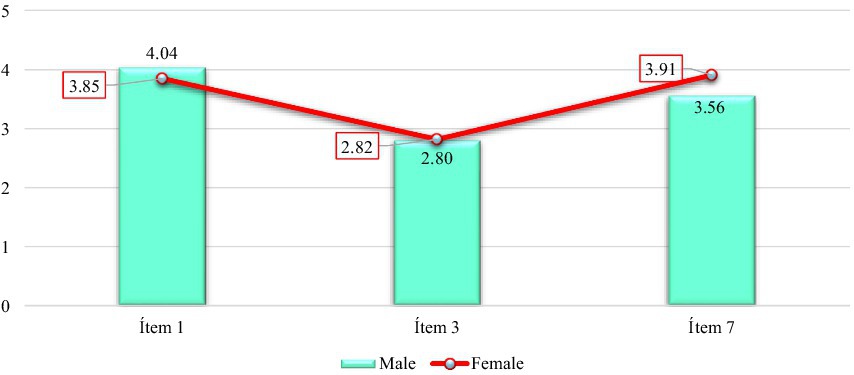

As for the analysis by gender of the participants, Figure 1 shows the highest and lowest mean scores of this group of participants, in terms of ratings.

Figure 1. Highest and lowest scoring items by gender on mean ratings of teaching effectiveness and transfer of learning.

To compare the trend in the median values, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U statistic was applied for two independent groups (after making the pertinent checks by means of the normality test). This U test confirms the starting hypothesis indicating that there are no significant differences (p > 0.05) between the assessment made by both sexes in relation to their initial perception of teaching in the effectiveness and transfer of learning.

Regarding the specific objective two (SO2), it refers to an evaluation after the implementation of a unit plan on the teaching of history on the processes of effectiveness and transfer of learning, according to the research group. The results are presented broken down, collecting the perception of the students of the experimental group and the control group.

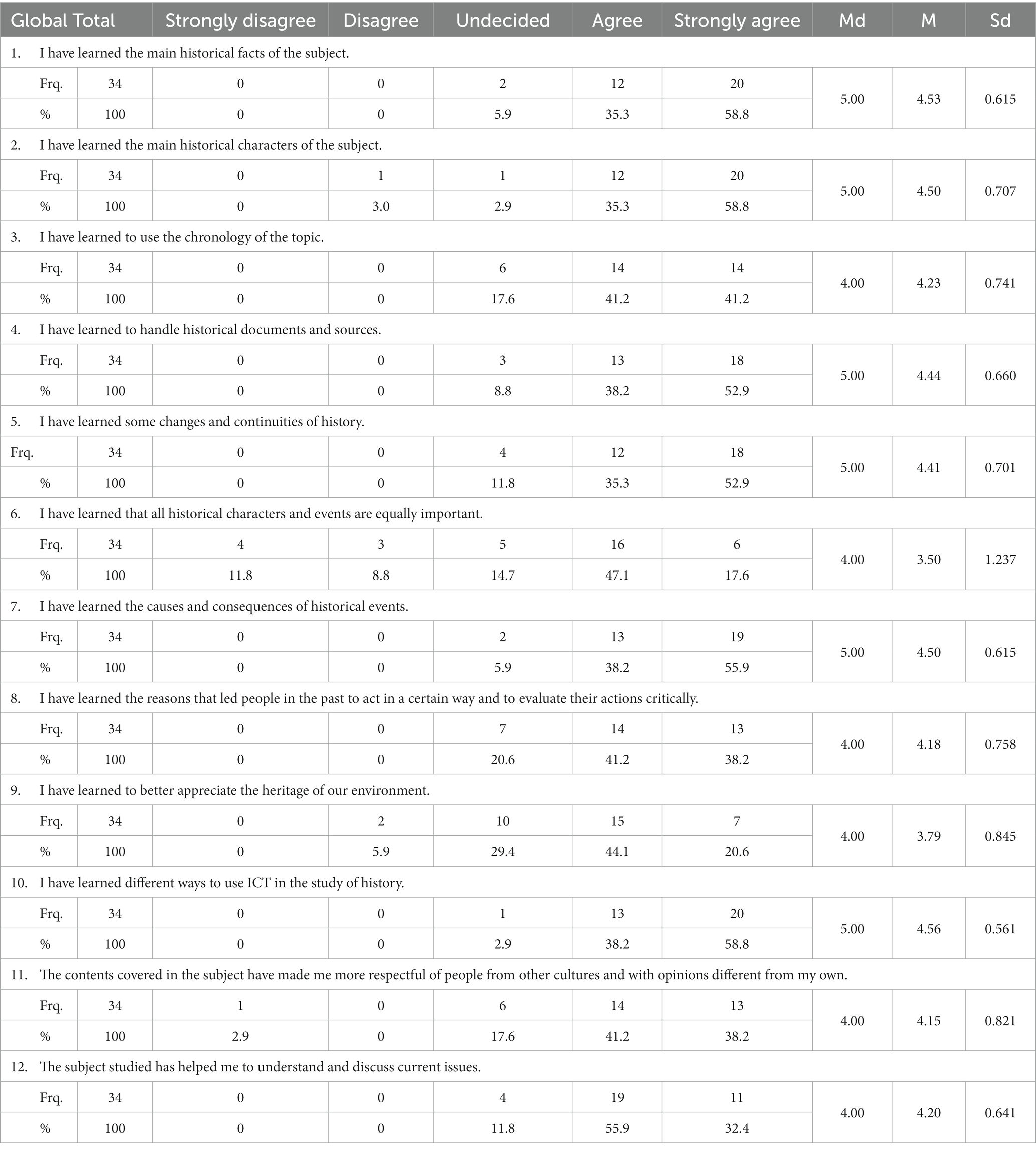

Table 3 presents the overall results of the experimental group, according to their assessment of didactic planning in the effectiveness and transfer of learning, which includes -as in the pretest- questions related to historical thinking competencies (Seixas and Morton, 2013), heritage, ICT or other citizen competences.

Table 3. Final perception of didactic planning on the effectiveness and transfer of learning, according to the experimental group.

As shown in Table 3, the results of the global evaluation carried out by the experimental group of the research show percentage values with a significant degree of agreement or acceptance in almost all the items, with five items in which the percentage of agreement with their statements exceeds 90%. These are items 1 and 2, referring to the learning of the main historical facts and characters of the subject (94.1%); item 4, on the handling of historical documents and sources (91.1%); item 7, relating to the learning of causes and consequences of historical facts (94.1%); and item 10, which describes the varied use of ICT in the study of history (97%), with students agreeing or strongly agreeing with their statements in all of them.

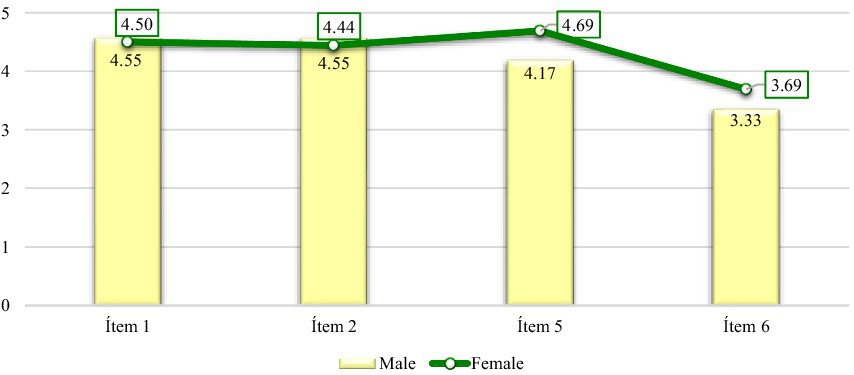

Similarly, the median is 4.00 points for items 3, 6, 8, 9, 11 and 12; and 5.00 points for items 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 and 10. This favorable median indicates that more than 50% of the participants agreed or strongly agreed with all the statements of the construct. These results are also corroborated by the mean statistic, whose values range from 3.50 (Sd = 1.237) for item 6, to 4.56 (Sd = 0.561) for item 10, the latter being the one that allowed us to verify a higher degree of agreement. Figure 2 shows the highest and lowest scores with respect to the trend of the mean of the experimental group, according to gender.

Figure 2. Highest and lowest scoring items by gender on experimental group mean ratings of didactic planning in the effectiveness and transfer of learning.

After applying the Mann–Whitney U test, the results indicate that there are no differences between sexes in this block, except in item 5 (p = 0.042), where a statistically significant variation is observed between boys and girls (p < 0.05).

Table 4 shows the results obtained by the control group in the post-test, which refers to didactic planning in the effectiveness and transfer of learning.

Table 4. Final perception of didactic planning on the effectiveness and transfer of learning, according to the control group.

Some items stand out for having a significant percentage of disagreement. This is the case of item 3, where 47.5% of students in the control group disagreed or strongly disagreed with having learned to use the chronology of the topic; of item 4, in which 35.5% did not consider having learned to handle documents and historical sources; of item 5, in which 30.5% of the cases deny having learned some changes and continuities of history; of item 9, in which 27.6% are against having learned to better value the heritage of the environment; of item 10, with which statement on the learning of ICTs to study history there was a 39% rejection; and finally, the case of item 11, in which 20.4% rejected that the contents of unit plan would have made them more respectful of other cultures and with contrary opinions.

On the other hand, the median is 3.00 points in items 3, 4, 5, 9 and 10, and 4.00 points in the rest of items, which shows that more than half of the participants of this control group were between the options of response 3 (undecided) and 4 (agree) which, together with the percentages of disapproval described in some items, leaves in evidence their doubts when it comes to showing themselves in accordance with the items presented. Finally, the trend of the mean follows a range between 2.81 (Sd = 1.196) in item 3, which denoted the most rejection, and 3.93 (Sd = 0.962) in item 1, in which the highest degree of agreement was observed.

Figure 3 presents the highest and lowest mean points of each gender, to synthesize the best-valued items of the control group students around didactic planning in the effectiveness and transfer of learning.

Figure 3. Highest and lowest scoring items by gender on control group mean ratings of didactic planning in the effectiveness and transfer of learning.

The perceptions of the male gender were compared with those of the female gender using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test to analyze the strength or impact of any differences. The results allow us to accept the initial hypothesis that there are no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the assessment according to the gender of the participants in the control group.

Finally, to compare the perceptions of the experimental group with those of the control group, Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of the means and medians for the items related to effectiveness and transfer of learning.

Table 5 shows that the experimental group obtained a group median of 4.31 points, which is higher than that of the control group (Md = 3.68 points), thus confirming that more than 50% of the students in each group scored above 4.31 and 3.68 points, respectively. For its part, the overall mean of all items analyzed as a whole is also higher in the experimental group (M = 4.25; Sd = 0.401) than in the control group (M = 3.48; Sd = 0.783).

In order to make the research more rigorous and systematic, this comparative analysis was complemented with the Pearson’s chi-square test. This statistic presents a null hypothesis based on the absence of a relationship between the variables analyzed. On this basis, two groups can be compared, and their relationship established. The results obtained (X2gl.3 = 18.99; p = 0.000) serve to reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis, thus confirming that there is a statistically significant relationship between the evaluation made by the experimental group and the control group on the effectiveness and transfer variable, in global terms.

The design proposed in this research has allowed the exercise of a methodological contrast approach that has been clarifying. This contribution has shown noticeable changes between both groups, before and after the implementation of the unit plan in history.

The prior teaching that adolescents received regarding the effectiveness and transfer of learning, including notions based on historical thinking, technology, cultural resources, or other citizenship education skills, offered an initial student perception of a neutral character, with widely distributed values, both positive and negative. The lowest perceptions are manifested in the low use made of chronology in the classroom, in the study of historical documents and sources and, especially in the low use of diverse learning with various technologies in history classes. These results confirm those found in the baseline studies (Rodríguez-Medina et al., 2020; Gómez et al., 2021a,b), where adolescents also denied learning the subject of History with different technologies, as well as learning to use documents and sources of the past. Solé (2009) points out that time is measured through the historical chronology, so the little use of this in the classroom could be because students have not yet acquired or assimilated specific historical strategies that develop structures that improve historical understanding. On the other hand, the low use of historical sources and documents only shows the persistence of the traditional teaching model (Monteagudo-Fernández et al., 2020).

In relation to the low presence of ICT and its forms of learning in the classroom, collected in the pre-test applied, Mourlam et al. (2020) have found that by implementing technology in the classroom, students have more fun, feel greater learning self-efficacy and are more motivated, an aspect with which Fragoso et al. (2020) agree, having demonstrated an improvement in the perception of learning thanks to ICT and mobile devices.

The pre-university stages must guarantee the formation of young people as active citizens, committed to their world. For this reason, a renewed didactics of history adapted to current needs must be offered; A proposal that teaches us to think about the past, value the present and take care of the future, that is, committed to evaluating the wide range of information available, and going beyond traditional routines, cultivating a set of intellectual skills and strategies, hand in hand with research, reflection and training in critical thinking. These procedures can be developed by learning to think historically. These previous findings have served as the basis for the implementation of the alternative unit plan with the experimental group, in accordance with these principles of active and critical learning, in order to establish the comparison with the control group, which followed a more traditional methodology.

After the implementation processes with both groups, the results of the post-test, in terms of effectiveness and transfer of learning, are much more prominent in the experimental group than in the control group. In the final perception of the students of this group, there is a favorable position toward the statements in almost all the items. In particular, most students acknowledge that have learned different ways of using ICT − this being the finding with the highest score−, which have learned about the most important historical characters and events on the subject, knowing how to drive historical sources and documents, identify some changes and continuities in history, or recognize the use of chronology. Likewise, they admit having learned the causes and consequences of historical events, to understand and critically evaluate the reasons for some actions in the past, and are aware of the importance of respect for other cultures and different opinions, stating that the active unit plan has helped them understand and discuss current issues, which is an added value to the leadership role that young people should have while learning, participating in the construction of knowledge.

Furthermore, Bartelds et al. (2020) argue that the use of classroom discussions at these ages can contribute to the learning of historical empathy skills, as perceived by students in their research. In fact, it has also been mentioned that working with historical empathy activities improves students’ self-perception regarding the understanding of historical facts and implies a more active participation in the activities (Doñate and Ferrete, 2019).

The results found in this study also coincide with those obtained in the work of Rodríguez-Medina et al. (2020) and Gómez et al. (2021a,b), although in these cases the position of the students was not as high as in this investigation, particularly in the existing perception of major historical events and figures, or in relation to technology-informed learning. This fact reopens the debate on the need for current teachers to have basic notions in ICT, adapting to the 21st century. Some studies (Sánchez et al., 2020; Sánchez-Ibáñez et al., 2021) have shown that teachers highly value receiving training in historical thinking skills, active learning methods and ICT resources, which seems to correspond to the perception expressed by the sample of students in this research.

Regarding the analysis by gender, the results obtained did not show the existence of statistically significant differences, except in item 5 of the posttest answered by the experimental group. The scientific literature analyzed has not allowed us to find studies that specifically analyze these variables. The existing ones do a global analysis (Gómez et al., 2021a,b). However, it is true that when a comparison was made with the study by Puteh et al. (2010), this study also found no significant differences between genders with respect to the historical thinking skills analyzed, except in the ability to rationalize, where boys showed a more positive perception that contrasts with our study, in which this item 5 confirms that girls appreciated learning about changes and permanence in history better than boys, which could be due to their greater interest in this thinking skill, or it could be the result of chance, since this data was not observed in the control group.

In today’s contemporary world, where manipulation is so easy, the characterization of highly developed global societies has consolidated frames of reference that sometimes lead to following false guidelines and generating doubts in the citizens. Transferring these circumstances to the context of Spain, it is necessary to teach the students of the 21st century −especially in the Baccalaureate Stage before university − own criteria that dignify and root a personality that allows them to fight against the domains that deprives them of such frames of reference. For this, the didactics of historical thought must be one of the main objectives of the coming years, thus consolidating its own culture that is modernized the teaching of history in our country. The visibility and interpretation of studies in which the methods and technologies are applied, as well as the offer of alternative skills, such as the use of sources, causality to explain the story, empathy as a resource to work the perspective of the historical context, the mastery of temporality to assume changes and permanence, the justification of the relevance of historical facts or the ethical dimension of knowledge of the past, offer an overview of the most successful ways of teaching history, thus ensuring a more adequate education for the coming years, whose knowledge favors the growth of more educated, reflective and democratic societies.

This research was based on a unit plan in which students had to interpret texts and images, reflect on and apply acquired historical knowledge, and answer questions through historical explanation and causal reasoning. In fact, these are two of the most important activities and exercises valued by secondary school teachers (Trigueros-Cano et al., 2022). As if this were not enough, the study revealed a very good assessment of this practice by students, which shows that young people require a learning of skills in the process of which they are given important doses of leadership.

The Anglo-Saxon current is one of the most established research approaches in the world. This model of thinking about history, in its various conceptions and forms, has allowed the teacher’s base to adopt the methods of the historian and plunge into the development of a didactics based on research and critical interrogation. However, we continue to attend, with a certain resignation, school realities in that students cannot think, reproducing closed knowledge that has little or no impact on the construction, revisionism or interpretation of history. Therefore, it is essential to extend the thinking model presented in this work and seek the development of more open and democratic mentalities so that students can successfully face social problems.

There are urgent needs in this direction, and new research should be initiated to develop a methodological change in the teaching of history to improve procedural skills and, consequently, analyze the effectiveness of adolescent competencies. For this, direct proposals are needed to evaluate this target group, linked to teaching through historical thinking and mediated by methodological alternatives and digital resources with which students acquire a more active role.

This study presents a case study that describes a specific educational reality in the Spanish context. Precisely for this reason, it is necessary to recognize that the aim is not to seek a generalization of the results. From a methodological point of view, the proposed study presents a quasi-experimental design using descriptive and inferential statistics with independent samples, according to the previous normality analysis. Specifically, it is necessary to point out that Pearson’s Chi-Square test was applied at a relational and associative level, taking into account that the comparison is presented in a descriptive manner, so that its main function was to determine the magnitude of the differences found, previously described. Despite having offered a rigorous response to the objectives set, it was necessary to point out this point for a fairer interpretation of the results obtained.

It is also necessary to emphasize that this study is limited to this group of participants, but is subject to a broader project, which includes other parameters and methodological proposals that will make the indications found more clearly visible. In any case, it is a fact that the young participants have shown a perspective that values the epistemological demands of the students, as well as the need for a change in the way of teaching them. A methodological approach is needed that offers them the possibility of accessing historical knowledge in better didactic conditions, being also transferable to new comparative contexts.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This work is the result of the research project “Teaching and learning of historical competencies in baccalaureate: a challenge to achieve a critical and democratic citizenship (PID2020-113453RB-100), funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation and State Investigation Agency of Spain (AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The author thank these government agencies for their financial contribution to this study.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baildon, M., and Afandi, S. (2018). “History education research and practice: an international perspective” in The Wiley International handbook of history teaching and learning. eds. S. A. Metzger and L. M. Harris (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell)

Bartelds, H., Savenije, G. M., and Van Boxtel, C. (2020). Students’ and teachers’ beliefs about historical empathy in secondary history education. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 48, 529–551. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2020.1808131

Berger, S., and Conrad, C. (2015). The past as history. National Identity and Historical Consciousness in Modern Europe. London: Palgrave McMillan.

Campbell, D. T., and Stanley, J. C. (1973). Diseños experimentales y cuasiexperimentales en la investigación social. (M. Kitaigorodzki, Trad.). Buenos aires: Amorrortu Editores.

Carretero, M. (2019). Pensamiento histórico e historia global como nuevos desafíos para la enseñanza. Cuadernos de pedagogía 495, 59–63.

Chaparro, A., Felices, M. D. M., and Triviño, L. (2020). La investigación en pensamiento histórico. Un estudio a través de las tesis doctorales de Ciencias Sociales (1995-2020). Panta Rei: Revista digital de Historia y Didáctica de la. Historia 14, 93–147. doi: 10.6018/pantarei.445541

Chapman, A. (2011). Taking the perspective of the other seriously? Understanding historical argument. Educar em Revista 42, 95–106. doi: 10.1590/S0104-40602011000500007

Claro, M., Nussbaum, M., López, X., and Contardo, V. (2017). Differences in views of school principals and teachers regarding technology integration. Educ. Technol. Soc. 20, 42–53. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26196118

Dickinson, A., Gordon, P., Lee, P., and Slater, J. (1995). International yearbook of history education. London: Routledge.

Domínguez, J., Arias, L., Sánchez, R., Egea, A., and García, F. J. (2017). Primeros resultados de una prueba piloto para evaluar el pensamiento histórico de los estudiantes. Clío Asociados 24, 38–50. Available at: https://www.clio.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/CLIOn24a03

Doñate, O. Y., and Ferrete, C. (2019). Vivir la Historia: Posibilidades de la empatía histórica para motivar al alumnado y lograr una comprensión efectiva de los hechos históricos. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 36, 47–60. doi: 10.7203/DCES.36.12993

Duquette, C. (2015). “Relating historical consciousness to historical thinking through assessment” in New directions in assessing historical thinking. eds. K. Ercikan and P. Seixas (London: Routledge)

Egea, A., and Arias, L. (2018). ¿Qué es relevante históricamente? Pensamiento histórico a través de las narrativas de los estudiantes universitarios. Educ. Pesqui. 44:168641. doi: 10.1590/S1678-4634201709168641

Fragoso, J., Trujillo, J. A., Molina, A. M., Olano, M., Caminero, V., and Sarduy, S. (2020). Experiencia sobre el uso del teléfono móvil como herramienta de enseñanza y aprendizaje en clases de Historia: percepción de los estudiantes. Medisur 18, 605–613. Available at: https://medisur.sld.cu/index.php/medisur/article/view/4541

Fronza, M. (2019). Los jóvenes estudiantes de escuela media y la generación del sentido histórico. Un estudio en un caso: una escuela de Várzea Grande y el narrar desde los cómics alusivos al encuentro entre indígenas y europeos durante la conquista de América. Historia y Espacio 15, 271–308. doi: 10.25100/hye.v15i53.8739

Gago, M. (2016). Consciência Histórica e narrativa no ensino da História: Lições da História…? Ideias de professores e alunos de Portugal. Revista História Hoje 5, 76–93. doi: 10.20949/rhhj.v5i9.239

Gértrudix, F. (2016). Métodos activos para la enseñanza en Educación Superior. En M. Gértrudix, N. Esteban, J. E. Hortal, and M. D. C. Gálvez (Eds.), La innovación docente con TIC como instrumento de transformación Madrid: Dykinson.

Gestsdóttir, S. M., Van Drie, J., and Van Boxtel, C. (2021). Teaching historical thinking and reasoning: teacher beliefs. Hist. Educ. Res. J. 18, 46–63. doi: 10.14324/HERJ.18.1.04

Ginting, A. S., Joebagio, H., and Dyah, C. (2020). A needs analysis of history learning model to improve constructive thinking ability through scientific approach. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. Res. 3, 13–18. Available at: https://ijessr.com/link2.php?id=261

Gómez, C. J., Chaparro, A., Felices, M. D. M., and Cózar, R. (2020). Estrategias metodológicas y uso de recursos digitales para la enseñanza de la historia. Análisis de recuerdos y opiniones del profesorado en formación inicial. Aula Abierta 49, 65–74. doi: 10.17811/rifie.49.1.2020

Gómez, C. J., and Miralles, P. (2017). Los espejos de Clío. Sílex: Usos y abusos de la Historia en el ámbito escolar.

Gómez, C. J., Rodríguez-Medina, J., Miralles, P., and Arias, B. V. (2021a). Effects of a teacher training program on the motivation and satisfaction of history secondary students. Revista de Psicodidáctica 26, 45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psicoe.2020.08.001

Gómez, C. J., Rodríguez-Medina, J., Miralles-Martínez, P., and López-Facal, R. (2021b). Motivation and perceived learning of secondary education history students. Analysis of a Programme on initial teacher training. Front. Psychol. 12:661780. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661780

Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., López-Facal, R., and Rodríguez-Medina, J. (2019). La investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales en revistas españolas de Ciencias de la Educación. Un análisis bibliométrico (2007-2017). Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 37, 67–88. doi: 10.7203/DCES.37.14440

Grever, M., and Van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2020). Popular uses of violent pasts and historical thinking (Los usos populares de los pasados violentos y el razonamiento histórico). J. Study Educ. Develop. 43, 483–502. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2020.1772542

Guerrero, C., López-García, A., and Monteagudo, J. (2019). Desarrollo del pensamiento histórico en las aulas a través de un programa formativo para Enseñanza Secundaria. REIFOP: Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 22, 81–93. doi: 10.6018/reifop.22.2.363911

Ibagón, N. J., and Miralles, P. (2021). Temas controversiales y educación histórica. En C. J. Gómez, X. M. Souto, and P. Miralles (Eds.), Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para una ciudadanía democrática. Estudios en homenaje al profesor Ramón López Facal Barcelona: Octaedro.

Kolikant, Y., and Pollack, S. (2019). Collaborative, multi-perspective historical writing: the explanatory power of a dialogical framework. Dial. Pedag. Int. 7, 89–100. doi: 10.5195/dpj.2019.245

Körber, A. (2017). Historical consciousness and the moral dimension. J. Hist. Conscious. Hist. Cultur. Hist. Educ. 4, 81–89. doi: 10.52289/hej4.100

Lévesque, S. (2011). What it means to think historically. En P. Clark (Ed.), New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada Vancouver: UBC Press.

Lévesque, S. (2023). “Narratives of the past. A tool to understand history” in Re-imagining the teaching of European history. Promoting civic education and historical consciousness. ed. C. J. Gómez Carrasco (London: Routledge)

López-García, A. (2018). El anfiteatro de Tarraco: Virtualizando la historia romana. Íber: Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Geografía e Historia 90, 80–82.

McMillan, J. H., and Schumacher, S. (2005). Investigación educativa (J. Sánchez, Trad 5ª Ed.). London: Pearson Educación.

Miralles, P., and Gómez, C. J. (2017). Enseñanza de la Historia, análisis de libros de texto y construcción de identidades colectivas. Historia y Memoria de la Educación 6, 9–28. doi: 10.5944/hme.6.2017.18745

Miralles, P. Y., and Rodríguez, R. A. (2015). Estado de la cuestión sobre la investigación en didáctica de la Historia en España. Índice Histórico Español 128, 67–95. Available at: https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/IHE/article/view/15185

Monteagudo-Fernández, J., Rodríguez-Pérez, R. A., Escribano-Miralles, A., and Rodríguez-García, A. M. (2020). Percepciones de los estudiantes de Educación Secundaria sobre la enseñanza de la historia, a través del uso de las TIC y recursos digitales. REIFOP: Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 23, 67–79. doi: 10.6018/reifop.417611

Monte-Sano, C., De la Paz, S., and Felton, M. (2014). Reading, thinking and writing about history. Teaching argument writing to diverse learners in the common core classroom, grades 6–12. New York: Teacher College Press.

Mourlam, D. J., DeCino, D. A., Newland, L. A., and Strouse, G. A. (2020). “It's fun!” using students' voices to understand the impact of school digital technology integration on their well-being. Comput. Educ. 159:104003. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104003

Parra-Monserrat, D., Sáiz-Serrano, J., and Valls-Montés, R. (2021). La enseñanza de la historia, una cuestión de identidad. En C. J. Gómez, X. M. Souto, and P. Miralles (Eds.), Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para una ciudadanía democrática. Estudios en homenaje al profesor Ramón López Facal Barcelona: Octaedro.

Prats, J. (2016). Combates por la historia en educación. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 15, 145–153. doi: 10.1344/ECCSS2016.15.13

Prats-Cuevas, J., Alabrús-Iglesias, R., Fernández-Díaz, R., and García-Cárcel, R. (2021). Enseñanza de una historia científica para una educación de calidad. En C. J. Gómez, X. M. Souto, and P. Miralles (Eds.), Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales para una ciudadanía democrática. Estudios en homenaje al profesor Ramón López Facal Barcelona: Octaedro.

Puteh, S. N., Maarof, N., and Tak, E. (2010). Students’ perception of the teaching of historical thinking skills. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Human. 18, 87–95. Available at: http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/pjssh/browse/special-issue?article=JSSH-0295-2010

Rodríguez-Medina, J., Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., Miralles-Martínez, P., and Aznar-Díaz, I. (2020). An evaluation of an intervention Programme in teacher training for geography and history: a reliability and validity analysis. Sustainability 12:3124. doi: 10.3390/su12083124

Rüsen, J. (2004). Historical consciousness: narrative structure, moral function and ontogenetic development. En P. Seixas (Ed.), Theorizing historical consciousness Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sáiz, J., and López Facal, R. (2016). Narrativas nacionales históricas de estudiantes y profesorado en formación. Revista de Educación 374, 118–141. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2016-374-328

Sánchez, R., Campillo, J. M., and Guerrero, C. (2020). Percepciones del profesorado de primaria y secundaria sobre la enseñanza de la historia. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 34, 57–76. doi: 10.47553/rifop.v34i3.83247

Sánchez-García, J. M., and Toledo-Morales, P. (2017). Tecnologías convergentes para la enseñanza: Realidad Aumentada, BYOD, Flipped Classroom. Red: Revista de Educación a Distancia 55, 1–15. doi: 10.6018/red/55/8

Sánchez-Ibáñez, R., Guerrero-Romera, C., and Miralles-Martínez, P. (2021). Primary and secondary school teachers’ perceptions of their social science training needs. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 1–11. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00705-0

Seixas, P. (2017). A model of historical thinking. Educ. Philos. Theory 49, 593–605. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363

Seixas, P., and Morton, T. (2013). The big six historical thinking concepts. Ernakulam: Nelson Education.

Solé, G. (2009). A história no 1° ciclo do Ensino Básico: a concepção do tempo e a compreensão histórica das crianças e os contextos para o seu desenvolvimento [Dissertação de Doutoramento, Universidade do Minho]. RepositoriUM: Repositório Institucional da Universidade do Minho.

Solé, G., and Llonch, N. (2016). Investigação sobre a transversalidade social, disciplinar e geográfica de um modelo de ensino-aprendizagem da história através de fontes objetuais e criação de museus de aula. Antíteses 9, 87–117. doi: 10.5433/1984-3356.2016v9n18p87

Trigueros-Cano, F. J., Molina-Saorín, J., López-García, A., and Álvarez Martínez-Iglesias, J. M. (2022). Primary and secondary school teachers’ perception of the assessment of historical knowledge and skills based on classroom activities and exercises. Front. Educ. 7:866912. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.866912

Van Boxtel, C., and Van Drie, J. (2018). “Historical reasoning: conceptualizations and educational applications” in. eds. S. A. Metzger and L. M. Harris (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell)

Van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2016). Reasoning with and/or about sources on the cold war? The use of primary sources in English and French history textbooks for upper secondary education. Int. J. Hist. Soc. Sci. Educ. 1, 19–51. Available at: https://www.pacinieditore.it/prodotto/irahsse-2016-n-1/

VanSledright, B. A. (2013). Assessing historical thinking and understanding: innovative designs for new standards. London: Routledge.

Keywords: teaching, learning, ICT, methodology, secondary, history, skills

Citation: López-García A (2023) Effectiveness of a teaching methodology based on the theory of historical thinking through active methods and digital resources in Spanish adolescents. Front. Educ. 8:1175123. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1175123

Received: 27 February 2023; Accepted: 10 April 2023;

Published: 02 May 2023.

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, University of Burgos, SpainCopyright © 2023 López-García. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alejandro López-García, YWxvZ2FAdW0uZXM=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.