- 1College of Public Health and Health Professions, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States

- 2Eck Institute for Global Health, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, United States

Introduction: Central to public health practice is mindfulness and intentionality toward achieving social justice and health equity. However, there is limited literature published on how educators are integrating these concepts into their curricular, pedagogical and instructional efforts. The goal of this study was to leverage the pluralistic views, social identities, and demographics within the classroom to explore the effects of introducing a Global Health Book Club (GHBC) assignment focused on identity of culture, equity, and power. We also sought to explore the use of first-account narratives illustrating the human experience as an instructional strategy to cultivate an empathic understanding of global health threats, while fostering critical consciousness toward one’s positionality within macro-level contexts. Finally, students were encouraged to reflect on their lived cultural experiences and engage in open and authentic dialogue with their peers.

Methods: We implemented a four-week GHBC assignment within an undergraduate global public health course. At the conclusion of the GHBC, students engaged in a reflective Individual Analysis Paper, which captured students’ perspectives on their cultural values and traditions, how these views shaped their understanding of their book, and evaluate whether their global perspective had changed as a result of the assignment. Thirty-one students consented to have their Individual Analysis Paper downloaded and de-identified for analysis. Student responses were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis procedures.

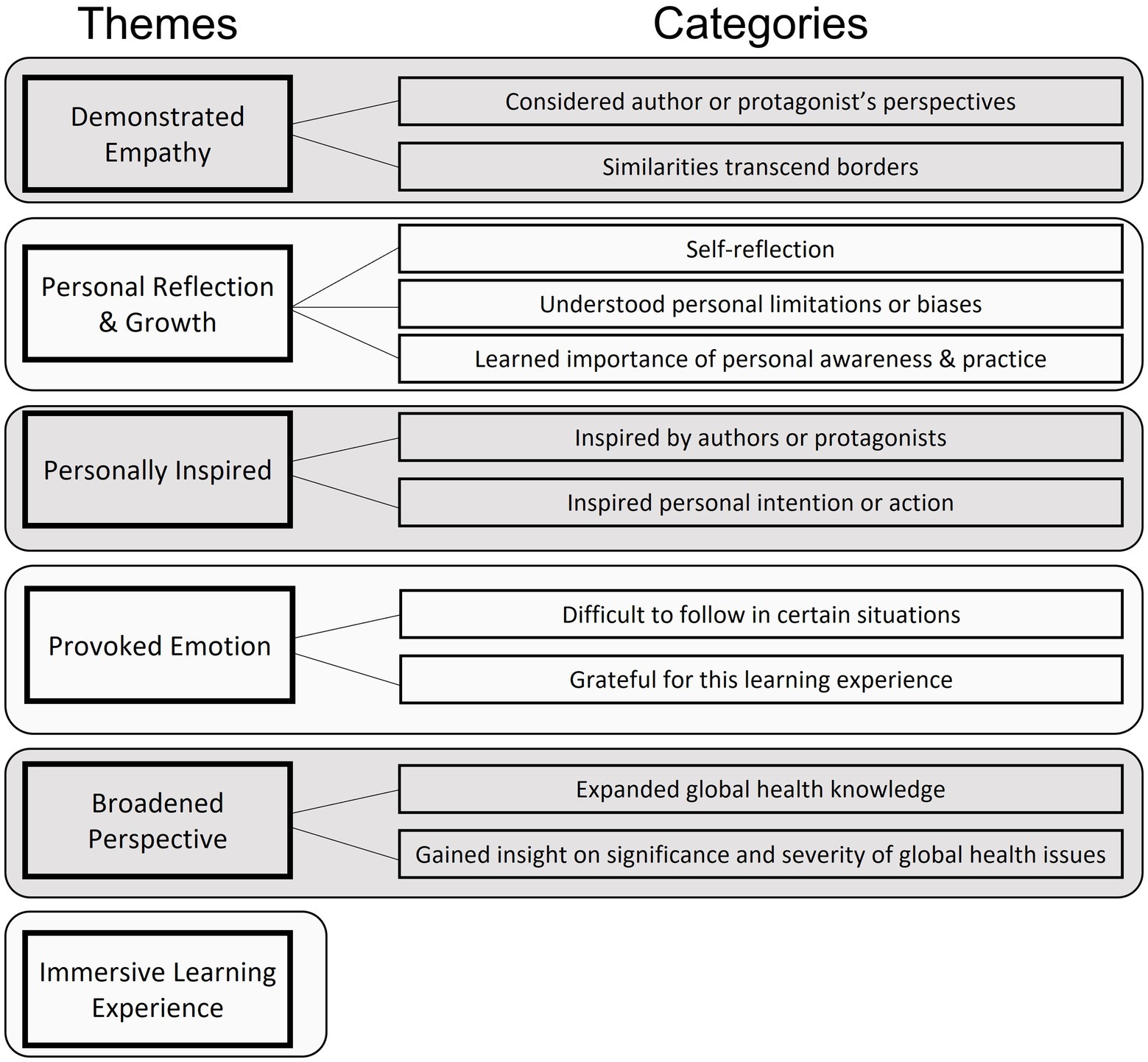

Results: Through our analysis, six themes, with several coinciding categories, were identified as salient. The themes include Demonstrated Empathy, Personal Reflection and Growth, Personally Inspired, Immersive Learning Experience, Broadened Perspective, and Provoked Emotion.

Discussion: Our findings support that a GHBC assignment is a viable and effective mechanism for engaging students in critical reflection, critical motivation and critical action. In cultivating a learning environment that promotes student-centered learning and active participation, students exemplified agency in their own learning. This work can serve as an exemplary model for other public health educators to engage students in reflective-based assignments regarding their positionality and critical consciousness. By utilizing frameworks conceived out of antiracism, diversity, equity, and inclusion, our work presents an innovative activity in engaging students in decolonization efforts within global public health practice.

Introduction

Social justice and health equity continue to become more central within public health practice (DeBruin et al., 2012; Hahn and Truman, 2015; Williams et al., 2019; Subica and Link, 2022; van Kessel et al., 2022). However, they are often omitted within current curricular and pedagogical efforts. There are several reports of social justice-based theoretical frameworks that serve as underpinnings for course development (Faloughi and Herman, 2021; Crawford et al., 2022), but limited published literature exists on individual assignments within public health coursework that engage students with concepts of health equity and social justice. Other health-related fields elucidate how including content on health equity (Braun et al., 2020; Denizard-Thompson et al., 2021; Bunting and Benjamins, 2022; Recto et al., 2022) and social justice (Hellman et al., 2018; Hughes et al., 2022; Shahzad et al., 2022) has not only improved students’ understanding of the social determinants of health but also contributed to providing impartial care for vulnerable and/or marginalized populations. Consequently, through intentionally integrating culturally responsive and culturally relevant pedagogies within public health education, we can train the future public health workforce to engage with and practice social empathy and holistic community advocacy.

One mechanism identified within other fields to initiate social change and transformative processes among adult learners is critical consciousness (Diemer et al., 2016; Jemal, 2017). Freire’s (1970) theory of critical consciousness (CC) aims to promote a learning environment in which individuals acknowledge both their own societal status as well as the status of others in order to enact actions that improve everyone’s situation. CC allows learners to reflect upon their awareness of historical, institutional, and structural oppression, perceived capacity, and their ability toward addressing these systems of oppression (Jemal, 2017). CC embodies three constructs that are simultaneously intersecting yet independent of each other: critical reflection, critical motivation, and critical action (Watts et al., 2011). This paper will focus primarily on critical reflection due to the structure of the assignments provided both as a group and individual reflection as well as the limited time to measure follow-up actions. Critical reflection is defined as the metacognitive process of finding one’s place in the world through critical analysis of self and society (Diemer et al., 2016; Jemal, 2017). CC, specifically critical reflection, is not a one-size-fits-all transformative experience wherein everyone recognizes their positionality and privilege—quite the opposite. It is through individual lived experiences that range from compounded marginalized social identities to relative privilege within current and historical sociocultural contexts (Diemer et al., 2016). While the CC framework was originally designed for marginalized populations to better understand their positions in society so as to create change, more research is emerging that incorporates those who have some aspects of privilege so that they may also critically reflect and contribute to societal transformation. While studies have demonstrated that educators in the field of public health who are familiar with critical pedagogy can effectively improve students’ ethical consciousness (Mabhala, 2013; Maker Castro et al., 2022), there is limited evidence on its translation into public health coursework. Likewise, recent attention has been placed on critical consciousness-raising as a medium to improve health literacy and related outcomes (Sykes et al., 2013), highlighting the need for future public health professionals to be educated on the principles of critical consciousness and become more globally aware of the problems impacting one’s health.

One strategy to raise critical consciousness is through the use of an intersectionality approach, in which people acknowledge how social constructs and systems of inequality create unequal power dynamics, thereby leading to disadvantaged populations (Nichols and Stahl, 2019). Born from the civil rights movement, the term intersectionality was coined by Crenshaw (1989), a legal scholar, meant to underscore the multidimensionality of marginalized populations, specifically Black women. Particularly, intersectionality seeks to examine how social constructs interact with each other so that individuals can apply their understandings to bring about social change (Bond, 2021). When introducing an intersectionality approach into the classroom, it is recommended to acknowledge the drivers of varying lived experiences to better understand an individuals’ position or stance (Cho et al., 2013). Intersectionality approaches in post-secondary education settings have aided students in their ability to think critically by considering the perspectives of others and act upon issues facing marginalized groups (Potter et al., 2016; Bi et al., 2020). Specifically, in health-related fields, there are numerous social factors such as race, income level, and sexual identity which can contribute to one’s health outcomes and further inequities (Pickett and Wilkinson, 2015; Gadson et al., 2017; Hsieh and Shuster, 2021).

To elicit conversations grounded in critical consciousness and intersectionality within a global context, educators must create environments where students feel empowered to challenge preconceived notions. Diverse learning environments encourage students to share aspects of their culture and individual lived experiences through means such as diversified curricula and learning materials (Otten, 2003; Tienda, 2013). One approach to creating an educational environment where discourse on social identity and individual perspectives can occur is through a book club. Book clubs have been demonstrated to empower students to discuss more personal matters while also creating an opportunity for them to engage in perspective-taking where the students gain a better understanding of others’ situations (Addington, 2001; Lewis, 2004; Henderson et al., 2020). As such, book clubs can act as an effective instructional tool for educators to foster critical consciousness where students consider how social factors impact the health of people on a global scale. Subsequently, a book club assignment was used for an undergraduate global public health course to encourage critical consciousness and perspective taking among a diverse group of students.

The goal of this study was to leverage the pluralistic views, social identities, and demographics within the classroom to explore the effects of introducing a global health book club focused on identity of culture, equity, and power. This study includes students from a cadre of different marginalized and privileged backgrounds wherein students must work in groups to produce communal reflections on a global health-based book as well as an individual reflection paper describing their own position from an intersectionality perspective. We seek to explore the use of first-account narratives illustrating the human experience as an instructional activity (or approach) to cultivate an empathic understanding of global health threats, while fostering critical consciousness toward one’s positionality within larger social, political, and global contexts.

Materials and methods

Global Health Book Club assignment

The Global Health Book Club (GHBC) assignment was embedded within an undergraduate, upper division (3000-level) global public health course at a large public university in the southern United States. This course permitted students of any major to enroll, however, it was composed primarily of public health and health science students. Within this course, students learned about various global health threats, strategies to promote locally-derived solutions, and described how social, economic, cultural, environmental, and institutional factors can influence key global health issues. Toward the middle of the 15 week semester, students were introduced to the GHBC assignment and were given seven books to choose from (Appendix A). Students were permitted to choose their own book and were given a deadline to provide the title, otherwise the instructor would choose for them. Once each student had chosen a book (posted within a Discussion within the course Canvas page) they were put into groups. The instructor chose books that addressed the larger ideas of the course: culture, equity, power, influence. The instructor was a qualified individual to moderate and select appropriate books due to being an experienced global health researcher and practiced educator. As such, several of the books touched on uncomfortable, and sometimes graphic, content; which made allowing the students to choose their book essential as well as promoted autonomy. Most books employed a strong narrative style, “human story” approach and addressed meso and macro perspective, while largely telling the story through the experiences of individuals. During the GHBC, it was emphasized that students should focus more on the story of the individual, appreciate their struggle, and compare and contrast their own identity with the author’s. Due to the large number of students (96 total) several groups shared the same book.

Prior to launching the GHBC, students were explained the purpose of this assignment within Appendix A. These instructions were shared to set the groundwork for potential discourse within groups as well as how to navigate these discussions with respect and thoughtful language. Students were encouraged to begin reading their book prior to the Spring Break recess; however, this was not a requirement. The GHBC was scheduled to last 4 weeks with each week having a short prompt (Appendix B) that the groups must submit as a whole, as opposed to individually. The weekly prompts were meant to incite broad discussion based on concepts presented within the book, while also tying it to global health issues. At the onset of the GHBC there was time set aside (roughly 30 min) at the end of each class to allow groups to discuss what they had read, share their interpretations, and work on the weekly prompt. The instructor intentionally did not engage with students while in their groups to encourage student-led conversations to organically occur. The culminating group assignment (Appendix B) included creating a trailer for the book each group read. These trailers allowed for creativity in sharing what the group perceived as major points within their book, while demonstrating respect for the protagonist’s story. The final individual assignment (Appendix C), and the source of data for this project, was the Individual Analysis Paper (IAP) that captured each student’s perspective on their own cultural values and traditions, how these views shaped their understanding of their book, as well as other content to demonstrate whether their global perspective had changed or not as a result of the assignment.

Data collection

Upon the completion of the course, all students were sent an email indicating if they would consent to their Individual Analysis Paper being used within a research study. Of the 96 students who were enrolled in the course, 31 consented to participate. Once consent was obtained, the IAPs were downloaded from Canvas and de-identified for analysis. Ethical approval was obtained for this study on May 23, 2022 by the University of Florida’s Institutional Review Board (IRB202201186).

Data analysis

Student responses were analyzed using an inductive thematic analysis approach (Patton, 1990; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Kiger and Varpio, 2020). The analysis process began with two researchers who each independently coded line-by-line using NVivo 12 Plus (Zamawe, 2015). Following the completion of this open-coding period, the two researchers began a negotiation period in which they compared each of the codes that they developed independently across the entirety of the data to reach a final consensus (Castleberry and Nolen, 2018). From there, the two researchers identified like-codes which were then grouped into labeled categories. Following the negotiation, themes and categories were presented to the larger research group where they were consolidated further based on characteristics of a specific phenomenon. Once the larger research group agreed upon final themes and subthemes, the two researchers operationally defined the most salient themes and categories to directly reflect the content from which they represent. Further, one outlier which was not condensed into the salient themes and subthemes included the concept of balancing personal cultural ties. The thematic analysis procedure employed provided the study with an inductive and systematic approach to considering the phenomena present in the data (Kiger and Varpio, 2020). Further, in line with thematic analysis principles, themes were not developed based upon the frequency of presentation but rather emphasized through the identification of commonalities continually present in the text.

Results

Thirty-one student papers were analyzed of the 96 students enrolled in the undergraduate Global Health course. Of the 31 students, 5 (16%) were male and 26 (84%) were female. Various races and ethnicities were represented including: 16 (52%) White, non-Hispanic; 6 (19%) White, Hispanic; 7 (23%) Asian; 1 (3%) Black and 1 (3%) not specified. A majority of students were public health or health science majors (88%), one (3%) Anthropology major, one (3%) Psychology major, and two (6%) Microbiology and Cell Science majors. Out of all of the book options listed in Appendix A, Worries of the Heart was not represented within this sample due to the small number of students who chose it as their book for this assignment.

Six themes were established including: Demonstrated Empathy, Personal Reflection and Growth, Personally Inspired, Immersive Learning Experience, Broadened Perspective, and Provoked Emotion. The two coders also established eleven categories: Considered Author or Protagonist’s Perspective, Similarities Transcend Borders, Self-Reflection, Understood Personal Limitations or Biases, Learned Importance of Personal Awareness and Practice, Inspired by Authors or Protagonists, Inspired Personal Intention or Action, Expanded Global Health Knowledge, Gained Insight on Significance and Severity of Global Health Issues, Difficult to Relate, and Grateful for this Learning Experience. A visual representation of the themes and subthemes is displayed in Figure 1.

Demonstrated empathy

This theme was characterized by student’s ability to empathize with situations outside of the context of their own life. Demonstrated empathy was further delineated into two categories: (1) considered author or protagonist’s perspective and (2) similarities transcend borders. Students reflected on the impact of war and its contribution to personal resilience. For example, in reading The Last Girl students also considered the significance of religious identity when one student states, “As someone who is not very religious this was beautiful to read about and made it all the more devastating when they were persecuted by ISIS. Additionally, I thought it was interesting, but also heartbreaking, how many of the girls were terrified they would not be accepted by their families due to the sexual abuse they had experienced because sex before marriage was prohibited in their religion.” Additionally, students reflected on being inspired by the resilience of the author or protagonist as exemplified as a student described, “I found it beautiful how Achak was living through events that I could never fathom going through, and he was still looking forward to small things in his life that bring him happiness.”

Considered author or protagonist’s perspective

In many cases, students directly sympathized with the author or protagonist’s perspective as well as learned from their vantage points, “I imagined myself as Nadia and losing my virginity to a random man who I did not know nor love and how disgusted I would feel when looking at myself in the mirror.” Further, by deeply considering these defining situations, students noted how it would have impacted themselves, “I have one older brother and one younger brother, both of which are old enough to have fallen in the category of those being executed.”

Similarities transcend borders

Notably, students elaborated on how there were significant, unexpected similarities that they shared with the people in the texts which transcended across cultures. Similar experiences concerning identity and culture were prevalent amongst student responses, “Similar to the author, I have experienced identity conflict and partial erasure as I have attempted to balance my two cultural backgrounds and experiencing judgment from both sides as a consequence.” In another regard, shared priorities were also evident, “Growing up with this family dynamic I felt a connection to Nadia’s feelings of appreciation and the importance of family.”

Students also considered ties and similarities across a wide spectrum of social identities such as religion and faith to sexuality and sexual orientation. Exemplifying the discussion of religion and faith, one student noted, “I was able to feel a connection to the main character, Valentino, as he talked about his faith throughout the book because, in many ways, it was similar to my own.” Moreover, discussion of similarities relating to queer sexuality resonated with students, “I did resonate with the aspects of the book that discussed queer identity and coming to terms with your sexuality because this is something I have experienced as someone who identifies as bisexual.”

Personal reflection and growth

This theme was characterized as realizations that the text instigated moments of reflection on personal perspectives as well as considerations of how these perspectives may develop. Personal Reflection and Growth was divided into three categories: (1) self-reflection, (2) understood personal limitations or biases, and (3) learned importance of personal awareness and practice. Students considered how publicized information is often limited and that often there is much more to learn in a global context, “I think that after reading Last Girl, I have become more cognizant of seeking out alternative perspectives on every story to become more insightful and aware of the whole picture.” Additionally, by reflecting on personal beliefs or attitudes, students understood that action may be required for tangible, personal growth, “In this position of privilege I have, there is a clear responsibility to uphold human rights and be vocal when they are abused.”

Self-reflection

Throughout the responses, students expressed personal introspection. In many cases, this form of reflection elicited recognition of one’s personal privilege, “It reminded me that while the United States is by no means a perfect country, it is still important to be appreciative for the life many Americans are able to live.” Students also expressed how considering the text allowed them to realize previous ignorance, “I realized that there are so many cultures, ethnicities, and ways people define themselves that I have no idea about.” In addition, self-reflection allowed students to recognize new responsibilities, “I enjoyed reading this novel, and I plan to hold myself responsible for learning about intersectional experiences of Latine folk throughout the rest of my career to best serve as a culturally sensitive medical provider for patients from these backgrounds.”

Understood personal limitations of biases

Students admitted in their responses that they experienced personal growth as they gained a greater cognizance of the impact of their disposition. More specifically, students noted limitations of lived experience or background, “I acknowledge that, as a white woman, I have had very different lived experiences than Anzaldúa and other women of color.” Some students also noted how their personal experiences affected their understanding and interpretation of the text, “I think that my culture of being a citizen of the United States, a member of a military family, and a Christian affected my understanding of this book.” Additionally, students discussed their limited prior global health knowledge as it pertained to the text, “I was completely ignorant to the entire war before reading this book.”

Learned importance of personal awareness and practice

Many students reported that the text taught them the greater importance of personal awareness as it pertains to cultural competence and humility, “Participating in the Global Health Book Club taught me a lot about myself, the world, and the importance of cultural humility.” In another regard, students also recognized the value of learning from people of another culture or of intersectional identities, “Throughout reading the novel, the most interesting aspects to me included learning about the author’s perspectives and intersectional identities.” The concept of intended practice was also expressed by students as they considered the importance of being a lifelong learner, “To be a lifelong learner and try to understand people’s cultures more deeply is not only important for the field of global public health, but for everyone in the world to stop discrimination, genocide, murder, and crimes against humanity to improve on the overall health and wellbeing of everyone in this world.”

Personally inspired

In many cases, students expanded on how the characteristics of the protagonists encouraged personal action from the readers. Personally Inspired was further divided into two categories: (1) inspired by authors or protagonists and (2) inspired personal intention or action.

Inspired by authors or protagonists

Characterized by students’ acknowledgement of the influential nature of the author or protagonist in the story, students described that “it was inspiring to see the author herself rebel and encourage rebellion among fellow women to maintain their voice against the multiple systems of oppression they face.” Notably, many students detailed how the resilience of either the author or protagonist inspired them, “the most inspiring part was their ability to pick themselves up and continue with their life.” Students also noted that they drew inspiration from the ability of either the author or protagonist to draw happiness from life while experiencing trauma, “Achak’s life was filled with so much trauma that it is amazing he stays so positive and motivated.” As it pertained to the writing choices that the authors made, students noted being inspired by rooting intentional literary choices in one’s own personal, cultural perspective, “Therefore, the author’s choice to stay true to her linguistic roots and Mexican heritage is intentional, and it is not meant to be tailored to the reader’s own linguistic background. I kept this in mind while reading, and this made me appreciate the effect and the author’s reasons for including this back-and-forth between languages.”

Inspired personal intention or action

Students expressed that they were inspired by the text to take personal action in global health issues, “Mountains Beyond Mountains, has only increased my learning about different topics but furthered my passion to get involved with global health issues to help aid and improve the health of individuals on a global scale.” In another regard, students considered how reading the text inspired the intention to emulate the morality of the protagonist or author when sharing, “I really admire Paul Farmer and I want to try to emulate his unending patience, kindness, intelligence, and moral motivation.” Many students also reported that the text also compelled them to learn more from a global health perspective illustrated by one comment of “I hope to carry this attitude with me in the future by seeking out the experiences of others more often so that I not only stay educated, but also empathetic and aware of injustices happening around the world.” Additionally, students often mentioned that the influential nature of the GHBC assignment inspired them to act with one student admitting that “Not only have I learned from the book, but the book inspired me to do more research about the civil war in Sudan.” Finally, students recognized that their group discussion work surrounding the text also incited intention for personal action: “Hearing about their future goals of improving the health of populations helped me realize that I can do the same as a dietitian.”

Immersive learning experience

Immersive Learning experience details students’ encounters with the author’s storytelling techniques and engagement with the dynamic nature of GHBC activities. GHBC assignments elicited student comments like, “I felt like I was fully immersed in ‘her world’ and was able to understand the implications of the attack more coherently and vividly due to her seamless storytelling.” In addition to the impact of the authors ability to engage readers throughout the story, students also explicitly noted that the GHBC was made even more immersive due to dynamic group discussion which allowed group members “to share their personal interpretations of the book and compare them with the other people in the group.”

Broadened perspective

Broadened perspectives included growth in personal global health perspective caused by a deeper understanding of situations as presented in the assigned readings. This theme was categorized into two subthemes: (1) expanded global health knowledge and (2) gained insight on significance and severity of global health issues. The broadening of students’ perspectives was made evident throughout the GHBC assignments as students mentioned a contrast between their previous worldviews before and after completing their assigned reading. This was evidenced as one student notes, “my global perspective was quite narrow for most of my life. Throughout this course and through reading this book, I have been able to broaden my understanding of the experiences of people in countries outside of the United States.”

Expanded global health knowledge

Expanding knowledge around global health issues was defined as the process of increasing insight into global health threats, systems, and history. In describing the book Mountains Beyond Mountains, she states, “I was able to grow in my knowledge about the global public health issues. I was extremely uneducated about issues such as affordable healthcare on a global scale prior to this reading, but was able to better grow and connect with these issues after completing this book. [The author] provides the reader with real-world situations that allow the reader to better connect and understand the issues being discussed within the book.” Another student elaborated on the benefits of having a group dynamic to gain knowledge from different perspectives, “[The assignment] challenged the readers to dive deep into global public health issues and apply new knowledge each week with the book club assignments. Working with others made the experience even more beneficial, as group members were able to share their personal interpretations of the book and compare them with the other people in the group.”

Gained insight on significance and severity of global health issues

Additionally, students shared the realization of the weight of global health issues through increased contextualization and awareness. One student noted that “this book helped me better understand the severity of disease other parts of the world experience.” Furthermore, students also noticed who is disproportionately impacted by severe global health issues as a student mentioned that “reading this book and discussing our thoughts and reactions with my group members has definitely broadened my perspectives on global health events and experiences of vulnerable groups of people.”

Provoked emotion

Provoked emotion consisted of experiences that solicited various reactions from GHBC participants. For example, a student described the difficulty in reading the assigned book as “it was very hard for me to read about how the girls were stripped of their agency and forced to serve men who used religion to justify their actions and the atrocities they committed.” Provoked Emotion was divided into two categories: (1) difficult to follow in certain situations and (2) grateful for this learning experience.

Difficult to follow in certain situations

Throughout the GHBC assignments students mentioned the barrier to understanding the story due to the author’s mode of developing the narrative. One student explained that “I found it quite difficult to gain the full perspective of each refugee’s story, which was condensed down to only a chapter.” When students lacked the contextual knowledge to further understand the story they described their experience as “hard for me to truly appreciate and relate to because religion was not a central part of my life when I was growing up.” Ultimately students seemed confused by their inability to draw a personal parallel to the protagonists’ situation as one student notes “while reading, at times it was hard for me to grasp and truly understand the events occurring throughout the book because I have never faced anything similar.”

Grateful for this learning experience

Students explicitly commented on their appreciation of the knowledge and insight gained by participating in the GHBC. Specifically, as a student mentions, “I am grateful to have participated in this learning experience and for the discussions I was able to have with my group.” Students also realized the value provided by the GHBC assignments as one student noted, “I’m so grateful for the opportunity to learn about these topics that I would have never took the time to learn if not for this book.”

Discussion

Social justice and health equity are central to public health’s mission and should be reflected within our educational and pedagogical practices as we train the public health workforce. Similar to how social justice response strategies have been developed within emerging and current public health work (DeBruin et al., 2012), a mindfulness and intentionality focused strategy toward employing social justice-based (Crawford et al., 2022), health equity-focused (Chandler et al., 2022), and critical pedagogically-grounded (Saunders and Wong, 2020) teachings should be at the center of public health education efforts. Unfortunately, there is limited literature available on public health curriculum and assessment that engage students with concepts of health equity and social justice. As such, this study implemented a Global Health Book Club (GHBC) assignment, grounded in theory of critical consciousness and intersectionality, to leverage the pluralistic views, social identities, and demographics within the classroom. Furthermore, this study explored the GHBC’s effects on identity relative to culture, equity, and power. Through an inductive thematic analysis qualitative inquiry, we were able to identify several salient themes and subthemes that captured the undergraduate experience of engaging with an innovative and reflective learning assignment.

Within the development of the GHBC, an attention toward the theory of critical consciousness (Freire, 1970, 1976), but more specifically the stage of critical reflection, was at the forefront. Critical reflection describes developing “an awareness of both the historical and systemic ways oppression and inequity exist” (Diemer et al., 2021, p. 13). It requires an individual to not only develop an awareness, but to also potentially grapple with any previous, personal assumptions or biases they may have. Some of these may even directly conflict with the exposure to evidence of historical systemic and institutional oppression, thus catalyzing the onset of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1962). Interestingly, the onset of cognitive dissonance is reportedly followed by a state of resolution, where the individual seeks to ease feelings of discomfort or misalignment as quickly as possible. This aligns with our findings, as students engaged in critical reflection as evidenced through several recurring themes such as Personal Reflection and Growth and Broadened Perspective, but also through themes Provoked Emotion and Demonstrated Empathy which required an intraindividual investment and vulnerability (Bardi et al., 2009). Invoking an emotional response, and potentially a value shift, demonstrates the value of critical consciousness as an effective mechanism to engage students in transformative learning and promote openness to a variety of diverse experiences and populations.

However, there were instances where students noted it was challenging to identify with the events or protagonist within their book, as shown within the Provoked Emotion category, Difficult to Relate. By not having their own personal experiences to draw upon as a form of relatability, students expressed that they had difficulty understanding the experience or conceptualizing the full depth of impact on the protagonist’s sense of being. This coincides with literature that states for learning to be significant, the content must personally affect the learner (Merriam and Clark, 1993). Without an underlying relatability, students may inadvertently struggle to connect with or fully value the experiences being shared. Consequently, a similar misalignment may be present with how our students may be able to relate and empathize with the communities they serve. The importance of developing a public health workforce that can understand, respect, and serve the problems of our communities cannot be overstated. As such, innovative teaching strategies have been employed to bridge the gap between student and community experience, alleviating some of the distress and difficulties students currently face when trying to relate to various populations (Campbell, 2016; Levin et al., 2021; Ingram et al., 2022). However, when implementing new teaching strategies and learning opportunities, we have to maintain a mindfulness to not perpetuate otherness principles between students versus community (Staszak, 2009), but highlight the mission of critical action or the “collective action to change, challenge and contest” inequities (Diemer et al., 2021, p. 13). This is particularly important as our results found students felt their similarities transcended borders, yet their differences caused ambiguity and confusion. This was most commonly expressed when students were not able to contextualize the centrality of a social indicator within one’s values, beliefs, and behaviors. This being said, opportunities to self-reflect and critically engage ultimately allowed students to express an understanding of their personal limitations due to biases and learned importance of personal awareness and practice, potentially reducing the effects of not relating to one another.

Unexpectedly, our results demonstrated students’ ability to transcend critical reflection and to also show elements of critical motivation and critical action. On more than one occasion, students expressed a moral commitment toward action induced by the inspirational onset of a protagonist’s resilience or the author’s behaviors, as depicted by the category, Inspired Personal Intention or Action. This greatly parallels critical consciousness’s critical motivation stage, which is defined as “the perceived capacity or moral commitment to address perceived inequalities” (Diemer et al., 2021, p. 13). And though students’ critical motivation was conceived out of the didactic accounts of adversity, there was also a salient reaction from many regarding the protagonists’ ability to overcome such adversity. Seeing triumph and resilience in experiences of trauma and oppression was notably a source of validation or reaffirmation of their choice to go into public health and/or related health professions. Interestingly, resilience within student responses was often conceptualized as a product of the protagonist’s experience rather than as a process of evolution and survival against adversity. Introducing resilience as a process rather than a product has shown to be intellectually and practically more productive (Joseph, 2015) and therefore should be an emphasis within framing community and personal experiences against adversity. In doing so, identifying aspects of individuals’ and communities’ strengths and successes may serve to be a powerful approach to public health intervention design, coalition building, and community capacity development (Trajkovski et al., 2013). In addition to protagonists’ experiences, students drew inspiration from the exemplary blueprints of behavior and leadership outlined by the author’s public health efforts and personal experiences, particularly within Mountains beyond Mountains by Dr. Paul Farmer. Based in social learning theory and social psychology, behavioral modeling has shown to be an effective way for framing and engaging students in ideal behaviors (Khan and Cangemi, 1979). As such, utilizing an adjusted interpretation of modeling by presenting first account narratives of exemplary models within public health and global health allows students to learn and strive to imitate these behaviors and leadership qualities. This was again evinced through the category, Inspired Personal Intention or Action, where students noted specific attributes and actions to engage in to meet their future professional and service goals.

Furthermore, through this book club we created a learning experience by encouraging students to share ideas, topics, and readings for the course, as well as their lived cultural experiences to facilitate dialogue and discussion of areas that their book club may not cover. Students noted the benefit of not only engaging with the readings but with each other through the theme, Immersive Learning Experience, specifically detailing the advantages of dynamic group discussion as an instructional strategy. In cultivating a learning environment that promotes not only student-centered learning but active and critical participation, students were allowed to be agents of their own learning (Freire, 1970; Ahn and Class, 2011). Congruent with others’ accounts of intentionally co-constructing knowledge with students, we found that students welcomed learning as a process rather than a tangible product such as assessment scores and grades (Ahn and Class, 2011). In doing so, the subjectivity of knowledge and value of lived experiences was realized among the student population. This idea fortifies other efforts within the public health field, such as Ford and Airhihenbuwa’s (2010) social construction of knowledge and voice, both of which prioritize the perspectives of marginalized persons and alternative methodologies/epistemologies as valid and influential forms of knowledge. Utilizing group discussions within a book club assignment supported the assessment objectives of focusing on identity of culture, equity, power, and influence through examples of the human experience, while also encouraging students to create and foster authentic learning communities grounded in celebrating each other’s diverse experiences.

Limitations

This study has potential limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, this analysis is based on a limited number of student responses within an undergraduate restricted access program course. The specificity of the study population may not be generalizable to broad undergraduate populations. Second, only student responses in which the student agreed to have their response analyzed were included. This may present a volunteer bias that often accompanies a convenience sample. Having only students who volunteered for consideration may lead our results to only include individuals who had a positive experience with the activity rather than encompassing the entire student population. Furthermore, among the students who did volunteer, there was an underrepresentation of Black identifying students compared to the overarching course’s composition. And lastly, by engaging in qualitative inquiry, there is the possibility of researcher bias. However, the study team utilized multiple, independent coders within the data analysis phase in an effort to reduce the risk of bias influencing the identified results.

Conclusion

This research is unique and novel since it contributes to limited scholarship around the intersection of public health practice and instructional strategies. Furthermore, this work can serve as an exemplary model for other public health educators of a theoretically grounded assignment to engage students in reflective-based discussion and writings regarding their positionality and critical consciousness toward health disparities, inequities and inequalities. Utilizing frameworks conceived out of anti-racist and diversity, equity, inclusion and antiracism, the instructional strategy outlined in our study presents one activity in engaging students in decolonization efforts within global public health practice. Prioritizing lived experiences, diverse perspectives, and authentic conversations, an effective and successful cultivation of an equitable learning environment was achieved. Furthermore, by introducing this approach within an undergraduate course, we have prefaced their future public health efforts with a mindfulness toward power, perspective, and privilege, as well as fostered a sense of agency for students to engage in collective action as future public health professionals.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data are student responses from a course assignment which may be identifiable as a whole based on semester of course, public records of enrollment, and unique experiences and identities shared within the responses. For the integrity of student confidentiality and anonymity, this data is restricted. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SLC, sarahcollins@ufl.edu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Florida Institutional Review Board. The participants agreed to participate in this study via electronic informed consent.

Author contributions

SLC and EW contributed to conception and design of the study. SLC also led data collection management efforts and wrote the discussion section of this manuscript. EW and SJC collaboratively wrote the background and introduction. EW also wrote the assignment description and data collection subsections of the Methods and Materials. SJC formatted the manuscript to comply with Frontiers in Education specifications. AR and AA conducted data analysis procedures and wrote the data analysis and results sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Addington, A. H. (2001). Talking about literature in university book club and seminar settings. Res. Teach. Engl. 36, 212–248.

Ahn, R., and Class, M. (2011). Student-centered pedagogy: co-construction of knowledge through student-generated midterm exams. Int. J. of Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 23, 269–281.

Bardi, A., Lee, J. A., Hofmann-Towfigh, N., and Soutar, G. (2009). The structure of intraindividual value change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 913–929. doi: 10.1037/a0016617

Bi, S., Vela, M. B., Nathan, A. G., Gunter, K. E., Cook, S. C., López, F. Y., et al. (2020). Teaching intersectionality of sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in a health disparities course. MedEdPORTAL 16:10970. doi: 10.15766/mep_23748265.10970

Bond, J. (2021). Global intersectionality and contemporary human rights Oxford University Press Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/39803.

Braun, R., Nevels, M., and Frey, M. C. (2020). Teaching a health equity course at a midwestern private university—a pilot study. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 40, 201–207. doi: 10.1177/0272684X19874974

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bunting, S. R., and Benjamins, M. (2022). Teaching health equity: a medical school and a community-based research center partnership. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 16, 277–291. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2022.0031

Campbell, A. T. (2016). Building a public health law and policy curriculum to promote skills and community engagement. J. Law Med. Ethics 44, 30–34. doi: 10.1177/1073110516644224

Castleberry, A., and Nolen, A. (2018). Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 10, 807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019

Chandler, C. E., Williams, C. R., Turner, M. W., and Shanahan, M. E. (2022). Training public health students in racial justice and health equity: a systematic review. Public Health Rep. 137, 375–385. doi: 10.1177/00333549211015665

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., and McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: theory, applications, and praxis. Signs 38, 785–810. doi: 10.1086/669608

Crawford, D., Jacobson, D., and McCarthy, M. (2022). Impact of a social justice course in graduate nursing education. Nurse Educ. 47, 241–245. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001152

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feministcritique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1.

DeBruin, D., Liaschenko, J., and Marshall, M. F. (2012). Social justice in pandemic preparedness. Am. J. Public Health 102, 586–591. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300483

Denizard-Thompson, N., Palakshappa, D., Vallevand, A., Kundu, D., Brooks, A., DiGiacobbe, G., et al. (2021). Association of a health equity curriculum with medical students’ knowledge of social determinants of health and confidence in working with underserved populations. JAMA Netw. 4:e210297. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0297

Diemer, M. A., Pinedo, A., Bañales, J., Mathews, C. J., Frisby, M. B., Harris, E. M., et al. (2021). Recentering action in critical consciousness. Child Dev. Perspect. 15, 12–17. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12393

Diemer, M. A., Rapa, L. J., Voight, A. M., and McWhirter, E. H. (2016). Critical consciousness: a developmental approach to addressing marginalization and oppression. Child Dev. Perspect. 10, 216–221. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12193

Faloughi, R., and Herman, K. (2021). Weekly growth of student engagement during a diversity and social justice course: implications for course design and evaluation. J. Divers. High. Educ. 14, 569–579. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000209

Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. SciAm. 207, 93–106. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1062-93

Ford, C. L., and Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2010). The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc. Sci. Med. 71, 1390–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. Ramos, Trans.). New York: Seabury Press. (Original work published 1968).

Freire, P. (1976). Education, the practice of freedom. London: Writers and Readers PublishingCooperative.

Gadson, A., Akpovi, E., and Mehta, P. K. (2017). Exploring the social determinants ofracial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome. Semin. Perinatol. 41, 308–317. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.008

Hahn, R. A., and Truman, B. I. (2015). Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int. J. Health Serv. 45, 657–678. doi: 10.1177/0020731415585986

Hellman, A. N., Cass, C., Cathey, H., Smith, S. L., and Hurley, S. (2018). Understanding poverty: Teaching social justice in undergraduate nursing education. J. Forensic Nurs. 14, 11–17. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000182

Henderson, R., Hagen, M. G., Zaidi, Z., Dunder, V., Maska, E., and Nagoshi, Y. (2020). Self-care perspective taking and empathy in a student-faculty book club in the United States. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 17:22. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.22

Hsieh, N., and Shuster, S. M. (2021). Health and health care of sexual and gender minorities. J. Health Soc. Behav. 62, 318–333. doi: 10.1177/00221465211016436

Hughes, T., Jackman, K., Dorsen, C., Arslanian-Engoren, C., Ghazal, L., Christenberry, T., et al. (2022). How can the nursing profession help reduce sexual and gender minority related health disparities. Recommendations from the National Nursing LGBTQ health summit. Nurs. Outlook 70, 513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.02.005

Ingram, C., Langhans, T., and Perrotta, C. (2022). Teaching design thinking as a tool to address complex public health challenges in public health students: a case study. BMC Med. Educ. 22:270. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03334-6

Jemal, A. (2017). Critical consciousness: a critique and critical analysis of the literature. Urban Rev. 49, 602–626. doi: 10.1007/s11256-017-0411-3

Joseph, S. (2015). Positive psychology in practice: promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, and everyday life. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Khan, K. H., and Cangemi, J. P. (1979). Social learning theory: the role of imitation and modeling in learning socially desirable behavior. Education 100, 41–46.

Kiger, M. E., and Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Levin, M. B., Bowie, J. V., Ragsdale, S. K., Gawad, A. L., Cooper, L. A., and Sharfstein, J. M. (2021). Enhancing community engagement by schools and programs of public health in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 42, 405–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102324

Lewis, M. (2004). Developing a sociological perspective on mental illness through reading narratives and active learning: a “book club” strategy. Teach. Soc. 32, 391–400. doi: 10.1177/0092055X0403200405

Mabhala, M. A. (2013). Health inequalities as a foundation for embodying knowledge within public health teaching: a qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 12:46. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-46

Maker Castro, E., Wray-Lake, L., and Cohen, A. (2022). Critical consciousness and wellbeing in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 7, 499–522. doi: 10.1007/s40894-022-00188-3

Merriam, S. B., and Clark, M. C. (1993). Learning from life experience: What makes it significant? Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 12, 129–138. doi: 10.1080/0260137930120205

Nichols, S., and Stahl, G. (2019). Intersectionality in higher education research: a systematic literature review. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38, 1255–1268. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1638348

Otten, M. (2003). Intercultural learning and diversity in higher education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 7, 12–26. doi: 10.1177/1028315302250177

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, inc.

Pickett, K. E., and Wilkinson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc. Sci. Med. 128, 316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031

Potter, L. A., Burnett-Bowie, S. M., and Potter, J. (2016). Teaching medical students how to ask patients questions about identity, intersectionality, and resilience. MedEdPORTAL 12:10422. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10422

Recto, P., Lesser, J., Farokhi, M., Lacy, J., Chapa, I., Garcia, S., et al. (2022). Addressing health inequalities through co-curricular interprofessional education: a secondary analysis scoping review. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 29:100549. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100549

Saunders, L., and Wong, M. A. (2020). Critical pedagogy: challenging bias and creating inclusive classrooms in instruction in libraries and information center. Urbana: Windsor & Downs Press.

Shahzad, S., Younas, A., and Ali, P. (2022). Social justice education in nursing: an integrative review of teaching and learning approaches and students' and educators' experiences. Nurse Educ. Today 110:105272. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105272

Staszak, J.-F. (2009). “Other/otherness” in International encyclopedia of human geography: A 12-volume set. eds. R. Kitchin and N. Thrift (Oxford: Elsevier Science) Available at: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:77582

Subica, A., and Link, B. (2022). Cultural trauma as a fundamental cause of health disparities. Soc. Sci. Med. 292:114574. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114574

Sykes, S., Wills, J., Rowlands, G., and Popple, K. (2013). Understanding critical health literacy: a concept analysis. BMC Public Health 13:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-150

Tienda, M. (2013). Diversity ≠ inclusion: promoting integration in higher education. Educ. Res. J. 42, 467–475. doi: 10.3102/0013189X13516164

Trajkovski, S., Schmied, V., Vickers, M., and Jackson, D. (2013). Using appreciative inquiry to transform health care. Contemp. Nurse 45, 95–100. doi: 10.5172/conu.2013.45.1.95

van Kessel, R., Hrzic, R., O’Nuallain, E., Weir, E., Wong, B., Anderson, M., et al. (2022). Digital health paradox: international policy perspectives to address increased health inequalities for people living with disabilities. J. Med. Internet Res. 24:e33819. doi: 10.2196/33819

Watts, R. J., Diemer, M. A., and Voight, A. M. (2011). “Critical consciousness: current status and future directions” in Youth civic development: work at the cutting edge. New directions for child and adolescent development. eds. C. A. Flanagan and B. D. Christens, vol. 2011, (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass), 43–57.

Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., and Davis, B. A. (2019). Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 40, 105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750

Keywords: global health, critical consciousness, instruction, intersectionality, decolonization, higher education, qualitative research

Citation: Collins SL, Case SJ, Rodriguez AK, Allen AC and Wood EA (2023) Cultivating critical consciousness through a Global Health Book Club. Front. Educ. 8:1173703. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1173703

Edited by:

Jessica Evert, Child Family Health International, United StatesReviewed by:

Charles Chineme Nwobu, Child Family Health International (CFHI), United StatesAmy Finnegan, University of St. Thomas, United States

José Luis Ortega-Martín, University of Granada, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Collins, Case, Rodriguez, Allen and Wood. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah L. Collins, c2FyYWhjb2xsaW5zQHVmbC5lZHU=

Sarah L. Collins

Sarah L. Collins Stuart J. Case

Stuart J. Case Alexandra K. Rodriguez

Alexandra K. Rodriguez Acquel C. Allen

Acquel C. Allen Elizabeth A. Wood

Elizabeth A. Wood