- 1Faculty of Education, College of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 2School of Education, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

- 3School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 4Multicultural Health Brokers Cooperative, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Empowering communities to respond to humanitarian crises is one of the core principles of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. In response to large numbers of refugees resettling in Canada from Syria as they fled its civil war, a community-based research partnership was initiated to examine the psychosocial needs and adaptation processes of Syrian individuals and families. In this article, we introduce Community Learning for Empowerment Groups (CLEGs) as a methodological innovation in participatory research partnerships and demonstrate how they can be used to harvest local knowledge and create critical spaces for transformative learning. We describe the process of co-creating CLEGs with seven recently resettled Syrian community leaders, examples of their implementation, and lessons learned in our community-based participatory research (CBPR). Grounded in a transformative paradigm, our CBPR project occurred over three phases of implementation. Activities undertaken by the research team in phase one aimed at empowering the leaders through a “train-the trainer” and collaborative learning approach to lead CLEGs in phase two. Focus groups were held with leaders in phase two to explore their experiences leading CLEGs. Discussions in focus groups revealed that leaders were empowered to adapt their learning from phase one according to their group dynamics and personal leadership style. Deepened insights and new facilitation approaches were evidence of leaders’ growth, as exemplified in the focus groups. Leaders were able to support their groups to generate and, in some cases, implement community-based solutions to their groups’ psychosocial challenges. Community Learning for Empowerment Groups are a promising model for supporting power sharing and knowledge co-construction in participatory research partnerships.

1. Societal context and background of the research project

When civil war erupted in Syria in 2011, its citizens experienced violence, loss of livelihood, and cultural, religious and social persecution. This caused millions to flee its borders over the next several years (Alberta Association of Immigrant Serving Agencies [AAISA], 2017). Starting in 2015, nearly 45,000 Syrians were resettled across Canada (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada [IRCC], 2021), relying on service providers, all levels of government, and the communities in which they settled to provide significant support within a short period of time (Alberta Association of Immigrant Serving Agencies [AAISA], 2017). In the province of Alberta, where the research project took place, 1025 Syrian refugee families were settled between November 2015 and August 2016 (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2017).

Empowering community workers to respond to humanitarian crises is one of the core principles of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (Ali and Ari, 2021). Previous research has demonstrated that refugee community leaders and workers can mobilize their community post-conflict and, facilitate discussions around psychosocial adaptation needs, raise awareness of services/supports, and support linking and bridging to the broader community (e.g., Kuriansky, 2019; Yohani et al., 2019). Finding culturally appropriate ways that empower new communities to address their multiple complex psychosocial needs is imperative in facilitating refugees’ resettlement, and ultimately integration, into host societies. Our research project, Psychosocial Adaptation and Integration of Syrian Refugee Communities Using Community Learning for Empowerment Groups project (CLEG project), was implemented with Syrian community members in the initial stages of their resettlement in Edmonton, Canada. This research was built on a small-scale mental health project (Yohani, 2018) that explored the feasibility of engaging Syrian community leaders and members in safe discussions of their experiences and psychosocial needs. The project was a response to mental health concerns raised at a Syrian community consultation meeting at the end of the first year of resettlement in Edmonton, Alberta. Members at the consultation shared their concerns that most Syrians would not be comfortable accessing clinical support (unless in a crisis) and many had not had a chance to reflect on their experiences. Given the raised concerns with the medical approach to addressing community-level concerns, the project also explored the relevance of a psychosocial framework (i.e., ADAPT framework in Section “1.1. Theoretical frameworks”) in relation to Syrian’s experiences.

The current CLEG project had the following objectives:

• Examine the psychosocial adaptation needs, challenges and processes of different Syrian refugee groups,

• Understand the processes involved in developing and implementing community learning empowerment groups,

• Understand how identifying and creating community-based solutions affect these groups’ integration pathways,

• Mobilize knowledge generated through the development of a resource manual to be used by Syrians and other refugee groups,

In this article, we describe the steps involved in empowering Syrian leaders in our research project to prepare them for their role in co-creating and facilitating discussion-based groups called Community Learning for Empowerment Groups (CLEGs). We introduce CLEGs as a methodological innovation in community-based participatory research partnerships and explain how they were used in our project to harvest local knowledge and create critical spaces for transformative learning. This occurred by empowering Syrian community leaders and members to identify the key psychosocial adaptation issues they were facing during the early years of resettlement and begin to map out community-based solutions.

1.1. Theoretical frameworks

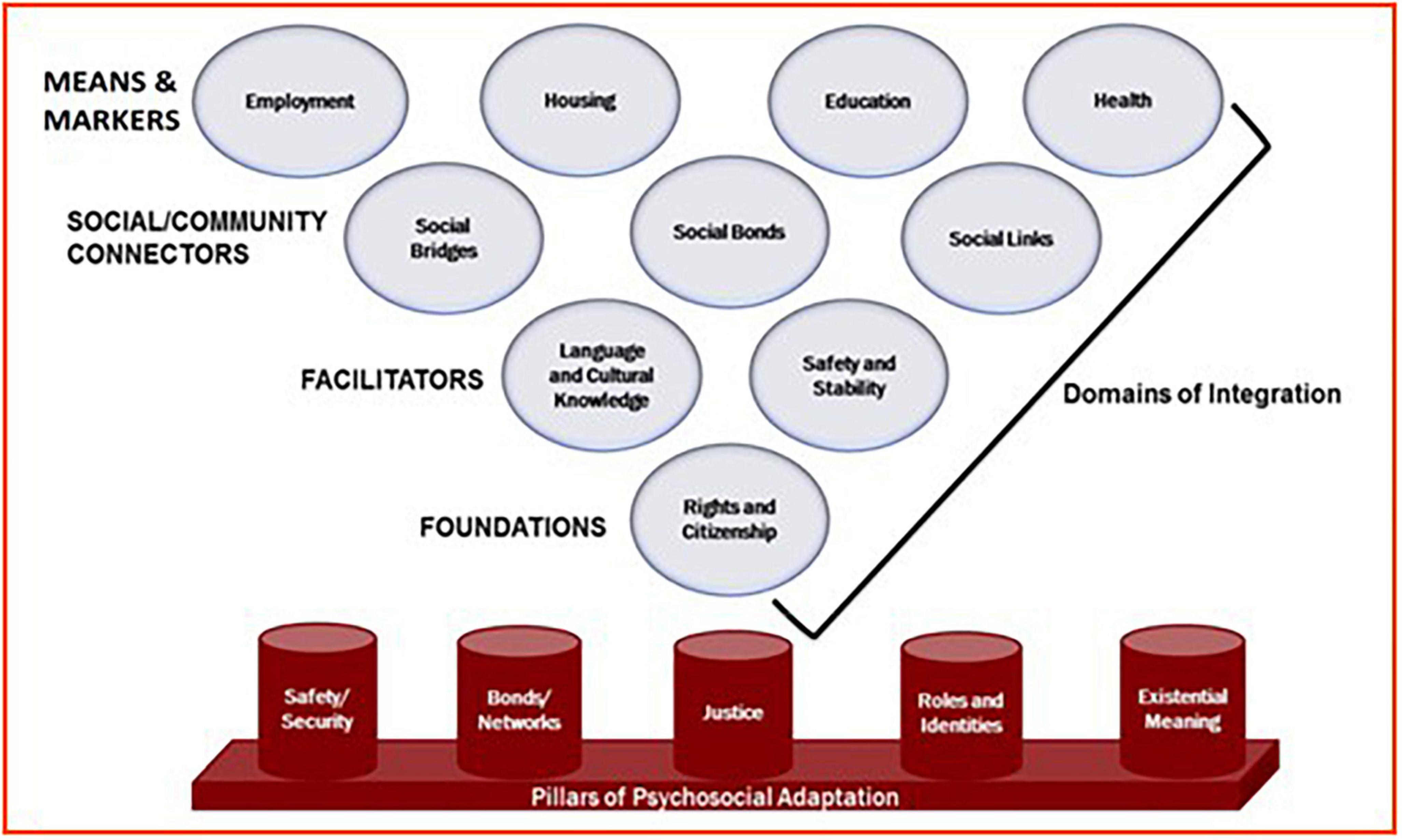

The Adaptation and Development after Persecution and Trauma (ADAPT; Silove, 2013) and the Social Integration frameworks (Ager and Strang, 2008; see Figure 1) provided a lens to view the process of resettlement and integration of Syrians into the new (i.e., Canadian) society. Combining these frameworks offered a unique approach to examining the intersection of psychosocial adaptation and overall refugee integration and formed the theoretical foundation for the CLEGs.

Figure 1. Combined social integration and ADAPT frameworks (Ager and Strang, 2008; Silove, 2013). Reproduced from Yohani et al. (2019) with permission from SNCSC.

The ADAPT conceptual framework illustrates the psychosocial challenges and resources of individuals and communities in post-conflict settings after mass violence. Five universal, yet culturally and contextually dependent psychosocial domains (safety/security, attachments/bonds, established roles/identity, a sense of justice, and existential meaning) can be the sites of traumatic experiences as well as sites for positive adaptation in situations involving mass violence and persecution (Silove, 2013). Ager and Strang’s (2008) Social Integration framework identifies critical domains for integration into a new society. Having rights and citizenship, safety, stability, cultural and language knowledge, and social connections is critical for refugee integration, including attaining critical markers such as employment, education, and health (referred to as “markers and means” in the framework).

The CLEGs in our research project were grounded on the integration of these frameworks. Using both frameworks allowed us to explore how the five domains of psychosocial adaptation identified in the ADAPT framework may affect the domains of social integration.

2. Methodology: community-based participatory research approach

Our research project was guided by a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR; Israel et al., 2008) approach and utilized ethnographic data collection methods (e.g., focus groups, prolonged engagement in the community and short feedback questionnaires). Epistemologically, CBPR is grounded in a transformative paradigm, and in this project, it meant that social change and intervention, generating knowledge with marginalized groups, and emphasizing social justice and empowerment were crucial aspects of the research process (Mertens, 2007; Israel et al., 2008). We intentionally used the ADAPT conceptual framework to explore psychosocial experiences with Syrian community leaders and members. The decision to use a psychosocial framework for group discussions stems from the previously described interest in an alternative approach to examining community-level mental health concerns and needs. The ADAPT framework and its universal psychosocial domains offered a general structure for beginning conversations and reflections at the community level and was viewed as relevant by community members engaged in the smaller exploratory project prior to implementing the current study.

As a relational approach to doing research “with” rather than “on” communities, CBPR draws on several principles to facilitate equitable partnership and co-learning (see Israel et al., 2008) and aligns with a transformative paradigm. For example, addressing power disparities between the researcher and the community, utilizing each partner’s unique strengths, and a commitment to mobilizing knowledge for action (Israel et al., 2008; Wallerstein and Duran, 2008) were instrumental in our project. These principles are critical when developing research partnerships with immigrant and refugee communities, which require ethical navigation of linguistic and cultural differences rooted in social power differentials (Georgis et al., 2018). They were also critical in a research partnership with community members who had recently experienced trauma and dislocation due to the Syrian crisis. Researchers who have used CBPR with refugee communities (e.g., Betancourt et al., 2015; Donnelly et al., 2019), have emphasized CBPR’s value for bidirectional capacity building (for researchers and communities) and “an enhanced understanding of (…) the social and cultural dynamics of the community” (Donnelly et al., 2019, p. 838). Donnelly et al. further note the importance of having “shared values” such as recognition and advocacy for refugee rights and a commitment to social change for successful CBPR partnerships with refugee communities.

2.1. CLEGs: an emerging methodology for CBPR partnerships

Community Learning for Empowerment Groups merge CBPR principles with adult transformative learning pedagogy to create spaces for healing, transformation, learning and action. The theory of transformative learning (Mezirow, 1991) considers learning a process that awakens human agency and critical consciousness. Mezirow (1997) defines transformative learning as “the process of effecting change in the frame of reference” (Mezirow, 1997, p. 5, italics in original). In this type of learning, adult learners identify and challenge the “frames of reference” (Mezirow, 1997, p. 5) about their experience (i.e., the assumptions, ideas, and feelings through which we make meaning of experience) and engage in critical evaluation and self-reflection on the experience. They also take action about the issues based on self-reflection and previous assumptions, which leads to a transformation of meaning, context, and long-standing propositions (Mukhalalati and Taylor, 2019, p. 3).

The potential contribution of adult education pedagogies such as transformative learning and experiential learning in enhancing CBPR partnerships has been explored by other researchers (e.g., Coombe et al., 2020; Kastner and Motschilnig, 2022), however, the introduction of CLEGs as a concrete model for developing and implementing community education interventions is unique to our project and contributes to critical education literature. As implied in their name, CLEGs are a methodology for empowering communities through collective learning and reflection. We outline below the key elements of a CLEG approach and how it brings together CBPR principles with transformative learning theory, and highlight its potential as an emerging methodological innovation for CBPR partnerships.

Both CBPR and transformative learning theory are critical approaches to engaging in research and learning, respectively, and both aim at enhancing agency and empowering individuals to take action in their communities. Researching experiences of trauma and marginalization requires a deep understanding of the realities of the communities and appropriate methods for engaging communities in conversations that feel safe and can lead to reflection and action, rather than simply documenting the communities’ experiences. Transformative learning theory sees reflection as a key aspect of the learning process and provides pedagogical tools for supporting learners to engage in self-reflection through dialogue. For communities that have experienced trauma, collective reflection is also needed for critical awareness and healing, in addition to individual level transformation. CLEGs are one way to achieve this collective critical awareness by drawing on CBPR principles, which frame action and learning as a community “rather than solely an individual” endeavor.

In our project, CLEGs were based on the ADAPT framework, which was used to reflect on experiences of collective trauma, migration, and psychosocial adaptation. Life circumstances for many refugees are such that the forced changes in their everyday life in the new cultural context do not always lead to a positive reintegration into the new life, and therefore would not lead to better adaptation to the host country’s environment (Taylor, 2007). In addition to the challenges caused by disruptions of their support systems, and informal and formal networks, refugees often face systemic barriers in accessing community resources in the host society, which in turn causes additional psychological distress and increases the risk of social exclusion (Ommeren et al., 2015). Moreover, organizations that offer support to refugees often fail to encourage positive and active integration processes among them, leading to disempowerment and further marginalization (Steimel, 2017). By drawing on CBPR principles of knowledge co-creation and adult transformative learning pedagogy, CLEGs provided a space for collective story-telling amongst Syrian community members, as well as the opportunity to frame their experiences of adaptation in ways that were meaningful to them and action-oriented. To achieve this, CLEG materials and processes were co-developed with community leaders to ensure they were culturally relevant and appropriate for the community and that community voice was driving the process as featured in CBPR. Moreover, CLEGs were run by community leaders, who co-acted as facilitators and adult educators around the ADAPT pillars in order to enhance community participation, agency and ownership over the research process. These are desired outcomes in CBPR partnerships and, as we will illustrate in this paper, were enhanced by the inclusion of transformative adult learning theory, which guided the training of the community leaders as well as the implementation of the CLEGs. Even though in our project CLEGs were based on the ADAPT framework, they can be used in relation to any framework or intervention as they provide a methodology for enacting CBPR principles to adapt interventions to local context and facilitate community healing and action. In what follows, we describe the co-creation of the CLEGs with community leaders and provide examples of their implementation and impact on our project.

2.2. Research team and identifying community leaders

The research team consisted of four academics experienced in community-engaged and participatory research (two psychologists, two child education specialists), four research assistants including two who were bilingual in both English and Arabic, seven Syrian community leaders, and four cultural community brokers (19 members in total).

Consistent with CBPR approach, the project conceived of community engagement as a source of knowledge and solutions to the real-life problems identified and experienced locally within the community (Peralta, 2017). Following ethics approval from the University of Alberta, we began by recruiting Syrian community leaders with the assistance of our community not-for-profit partner organization, the Multicultural Health Brokers (MCHB) cooperative. Cultural brokers from MCHB and their contacts in the Syrian community identified and invited potential leaders. These included community leaders who participated in a pilot study conducted in 2016–2017 (Yohani, 2018) and through a Syrian community association. Initially, eight leaders expressed interest in the project, but one withdrew after the first information session due to a conflict with the time commitment. Of the seven who consented to join the project, five had been part of the previously mentioned pilot study. Further, five were natural leaders, and two were formal community association leaders at the time of the project. Natural leaders refers to individuals recognized as informal leaders within the Syrian community. The Syrian community leaders represented diverse religious and ethnic groups (e.g., Kurdish, Druze, Muslim, Christian), educational and vocational backgrounds, and they had come from disparate regions in Syria such as Dara’a and Damascus. Three leaders were female and four were male. Each leader facilitated a CLEG that reflected aspects of their identity; for instance, a female, Kurdish leader facilitated a CLEG made up of other female, Kurdish members of the Syrian community. This was intended to enhance safety within each CLEG while also capturing the diversity of the Syrian community. Other studies have shown that community individuals identified as leaders can facilitate workshops on their own and support their communities in psychosocial intervention programs (e.g., Kuriansky, 2019). Cultural brokers were an integral part of the team and involved in all aspects of the project. The lead cultural broker was also the community coordinator (sixth author) and worked with the academic team members to recruit three additional cultural brokers from the MCHB to ensure representation of various cultural and language backgrounds of the Syrian leaders and community participants. As mediators of culture and language in the project, they engaged in discussions with the leaders and academic team members and co-created the CLEG guide. They supported language and cultural interpretation throughout the project and were also involved in translating documents developed, including the feedback questionnaire and draft CLEG guide.

2.3. Project activities, training, and data sources

2.3.1. Project activities

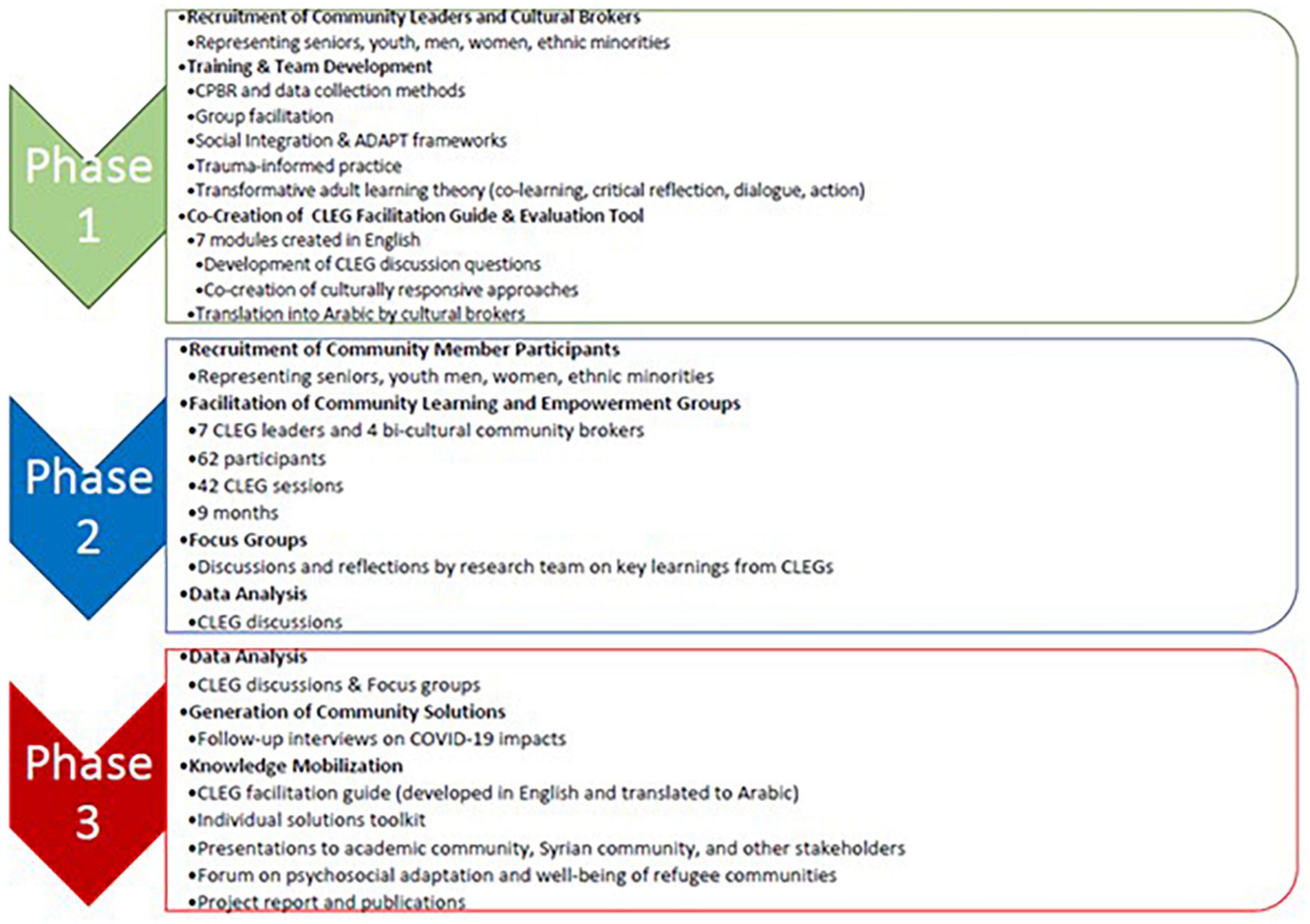

The project activities were carried out in three phases: (1) Orientation/Training and Development of CLEG Facilitation Materials; (2) Implementation of CLEGs groups, which included focus group discussions and data collection/analysis; and (3) Resources and Knowledge Mobilization. While all activities and phases are summarized in Figure 2, in this paper we discuss activities in phases one and two that focus on the empowerment of the Syrian leaders and their role in co-developing and running the CLEGs. During the first phase of the project, we incorporated aspects of a “train-the-trainers” model, “a program or a course where individuals in a specific field receive training in a given subject and instruction on how to train, monitor and supervise other individuals in the approach” (Pearce et al., 2012, p. 216) in our collaborative learning activities. This is a widely acknowledged educational model used with refugees in different contexts (e.g., Kuriansky, 2019; Fragkiadaki et al., 2020), and in our project it supported community leaders in gaining a deep understanding of the ADAPT model.

2.3.2. “Train the trainers” approach to training and learning sessions

The training and learning components of the project built on the adult learning concept of empowerment as a critical goal for refugees that enables them to make “external change to relationships, situations, power dynamics or contexts” (Brodsky and Cattaneo, 2013, p. 338). To support this, we created circumstances for learning in our research project that have the potential to empower the Syrian community members and leaders to become active agents and advocate for their resettlement needs. The train-the-trainer approach was used in the spirit of transformative learning theory and collaboration with the community leaders. Our research team provided “training” on psychological trauma in the context of the ADAPT pillars to prepare the leaders to use the ADAPT framework in their conversations with community members. Community leaders provided valuable feedback on how to frame discussions around the five pillars of the ADAPT framework in culturally relevant and accessible ways, considering the lived experiences of the community members. Similar approaches to integrating psychosocial training with community voices have been effectively used in other projects aimed at refugee empowerment (Kuriansky, 2019; Bentley et al., 2021).

2.3.3. Data sources

Data sources include: (1) field notes taken during eight research team/training meetings, (2) a short feedback questionnaire administered to community leaders during phase one, and (3) transcripts of focus group discussions during phase two. These primary sources of data were analyzed and are described in this article, along with illustrative examples that demonstrate leaders’ descriptions of empowerment.

3. Results: empowering leaders to create and facilitate CLEGs

3.1. Phase one: orientation/training and co-creation of CLEG facilitation materials

As part of the research process in phase one, we held eight research team meetings (3 h each) with time dedicated to reflecting on the integrated theoretical frameworks used in the project (meeting 1), training on CBPR research (meeting 2), group facilitation skills (meeting 3), and co-creating CLEG materials centered on the five domains of the ADAPT framework (meetings 4–8). This integrative psychosocial framework (ADAPT) served as a new “frame of reference” (Mezirow, 1997, p. 5) for reflecting on and connecting the multiple issues, stressors, and resources facing war-affected individuals and communities in the diaspora. As noted earlier, the ADAPT model uses universally understood concepts and has been used successfully with urban refugees in Syria as “a practical framework that can guide different aspects of programming without being overly rigid on prescribed content or context” (Quosh, 2013, p. 207).

In the following section, we describe the activities undertaken by the research team that aimed explicitly at empowering the community leaders through various training and collaborative learning sessions. These sessions were a component of the eight research team meetings in the first phase of the research project. We have included an example of one of the sessions (i.e., the ADAPT training module on safety) illustrating how the ADAPT safety module was co-created.

3.1.1. Introduction to theoretical frameworks and methodological approach to the study (team meetings 1 and 2)

Grounded in the participatory epistemology, the first meeting between the researchers, the leaders, and the cultural brokers focused on the theoretical frameworks underpinning the research project leading to the development of CLEGs—the ADAPT model and Ager and Strang’s (2008) Social Integration framework. Introducing the community leaders and the cultural brokers to these theoretical frameworks acknowledged that “becoming a refugee is a source of deep learning as they confront unexpected changes in their life plans and the need to reshape their lives and reconstruct their identities” (Morrice, 2012, p. 253). Refugees move across national borders and social and cultural spaces, which requires intense learning. Uprooted from their communities, culture, work, language, and ways of life, refugees are forced to adapt to their new environmental structures and to modify their expectations, the meaning they assign to everyday life events, and their sense of self concerning the new environment and the people in it. Understanding the theoretical foundations of the research project was essential for helping the community leaders and the cultural brokers to see their role in the project and how the different components of this project fit together. The academic team members also hoped this knowledge would empower the community leaders to take action and make changes in the context of the project, their own lives, and the life of their community.

During the second meeting, the fundamental principles of the CBPR approach were introduced to the brokers team. Understanding the research approach as a collaborative effort reassured team members, especially the community leaders and cultural brokers that all decisions regarding the research would be made in consultation and accordance with the CBPR principles. Throughout the project, the academic members of the research team were conscious of our position of power and leadership with the backing of an academic institution, which inherently conveys privilege (Wallerstein and Duran, 2008). We also recognized that we were the “knowledge holders” during the training components that focused on understanding trauma and potential impacts on refugees’ mental health and wellbeing within the context of the ADAPT and Social Integration frameworks. We sought to ease this imbalance by creating an environment of openness and critical reflexivity by inviting the leaders to reflect on their experiences and cultural understandings concerning the material. For example, how trauma is understood within our respective cultures compared to Eurocentric and medical understandings of trauma. We used the same approach to empower community leaders and cultural brokers to co-create the CLEG facilitation materials with us. Further, leaders and cultural brokers’ knowledge and expertise transformed academic research team members’ perceptions and understanding of topics covered and shaped the facilitation materials to be more culturally relevant and community informed for Syrians.

3.1.2. Establishing group rules (team meeting 3)

A key aspect of community leaders’ preparation for their role as CLEG facilitators was developing their ability to be influential and safe group leaders. The research team agreed that developing the skill set necessary to be a group leader is one of the core aspects of capacity building. As part of the training on group facilitation at the third team meeting, we responded to a request made by one of the leaders who stressed the importance of setting up group rules at the first CLEG meetings to set the standard for how the sessions would run throughout the group and ensure safety of community members. Clear group rules can help structure the sessions and prevent them from getting off-track, creating a reliable sense of safety and stability around the group sessions, particularly for individuals with trauma histories. This safety foundation also helps shy group members feel more willing to attend each group session (Corey et al., 2014). In addition, group rules can be strategically used to ensure that group members treat each other with respect throughout each session and allow discussion about more controversial issues (Corey et al., 2014), as was the case in our project. While our research team preferred group members to develop the rules for their group, as this creates more adherence, we agreed on some recommended standard rules to help ensure the safety and stability of the CLEGs. Some rules drew from group counseling, such as striving to arrive on time, maintaining confidentiality, and attending all sessions if possible. Group rules recommended by the leaders based on their understanding of Syrian culture and etiquette included:

• “Listen to others’ truths from your heart and your ears.”

• “Be open to hearing other people’s experiences.”

• “Treat others how you would want others to treat you.”

• “Respect each other and their points of view.”

• “Do not interrupt other people.”

• “Give everyone an opportunity to share their truth.”

• “Allow all members an opportunity to share their stories.”

In each subsequent CLEG co-creation sessions and project meeting, we modeled these rules together and referred to them as needed (e.g., “allow all members to share their truth”). We also elaborated on these rules together as the time for the leaders to begin forming their CLEGs approached.

3.1.3. Co-creation of CLEGs using the ADAPT model’s five domains (team meetings 4–8)

The final five meetings were devoted to co-creating the CLEGs by examining each core domain of the ADAPT model (safety, attachments, identity, justice and existential meaning) in more depth while experimenting with the CLEG group discussion questions and format. As such, the training sessions on the ADAPT model’s domains at this stage of the project were discussion-based and emphasized mutual knowledge co-construction, sharing and exchange. Supporting Syrian community leaders to develop knowledge and skills for group facilitation during the co-creation of ADAPT modules is also consistent with a CBPR approach, which empowers research participants to continue using these strategies without professional researchers (Fals Borda, 1988). In our project, the ADAPT framework was also used to empower the community leaders and members to continue the work after the research ended.

In preparing the community leaders for their role as facilitators of CLEGs, we, - as the researchers, the majority of whom are first-generation immigrants, - understood that experiencing sudden disruptions to inherited frames of reference opens possibilities for transformative learning. We acknowledged that community leaders have acquired a coherent body of experience–associations, concepts, values, feelings, conditioned responses–known as frames of reference that define their worldview. As Mezirow (1997) elaborates, frames of reference are the structures of assumptions through which we understand our experiences. They selectively shape and delimit expectations, perceptions, cognition, and feelings. They set our “line of action” (Mezirow, 1997, p. 5). For refugees, in particular, who flee life-threatening circumstances, the disruption of the inherent frames of reference and the accumulated biographical repertoire of knowledge and understanding is sudden, creating a disjunction between biography and experience, which as Jarvis (2006) suggests, is the beginning of all learning. He continues that the need to re-establish harmony is amongst the most important motivating factors for most individuals to learn (Jarvis, 2006, p. 77).

3.1.4. ADAPT safety module co-creation: an illustrative example

The sessions focused on co-creating the five ADAPT modules followed a similar pattern. The role of the cultural brokers was essential. Cultural brokers were responsible for accurately translating and interpreting the discussions so that culture and language-based misunderstandings did not prevent the exchange of information and ideas between the research team and the leaders.

At the beginning of each session, the research project’s principal investigator (first author) introduced the domain of focus for the given session (e.g., safety) and described its adaptive function in the context of daily life. Next, community leaders discussed how they understood the given domain based on their lived experiences of it, and their perceptions of its cultural and linguistic contexts. Leaders and cultural brokers used this process to agree on a shared Arabic term for use in the CLEGs (e.g., they agreed that they would use the term “al-salaam” to refer to “safety”). Following this, the principal investigator and two other research team members invited leaders to reflect on their individual and collective experiences with the domain in relation to their refugee experiences and settlement in Canada. Sessions included feedback on how responses to threats brought on by war can be both adaptive and maladaptive, contributing to hindering or supporting adaptation and integration. This way, the sessions on each domain offered a model for facilitating the CLEGs. As participants in the sessions, leaders observed how to introduce each domain, describe it, and lead a discussion while also being able to share their ideas, experiences, and feedback on the formulation and flow of questions. As a result, leaders could learn through experience both the ADAPT framework and group facilitation, developing further their capacity to facilitate the CLEG discussions in phase two.

During the initial exploratory part of the discussions, the leaders’ “frames of reference” (Mezirow, 1997, p. 5) about their experience were revealed and shared among all group members. Below we describe the ADAPT session on safety, to illustrate how each of the five ADAPT sessions unfolded. The training session on safety began with an exploration of the meaning of safety in Arabic and Kurdish languages as well as Syrian and Kurdish cultures. Leaders shared that the concept of safety closely relates to a sense of peace, justice, and respect, in their words:

• “If I feel (at) peace, I feel safe.”

• “When the country has justice, there is safety.”

• “Respect is the most important thing for justice and safety. It is important at both government/system and individual levels.”

• “Anywhere people have justice, they feel safe; they go together.”

Some of the leaders commented on the importance of the concept of safety in the ADAPT model. Others offered definitions and pointed out that they are different dimensions of the concept of safety:

Safety has a broad definition, but at a personal level, it means a safe environment for me and my children. (The question is), how can I exclude danger and minimize risks in my life and my children’s life?

Safety can be divided into two dimensions: Inside and outside oneself, and these are linked to psychological and physical safety. So there is safety inside and outside oneself, and these are linked to psychological and physical safety.

The most animated engagement in critical self-reflection on the experiences of safety was evident in the discussion about the differences between leaders’ sense of safety in Syria, transition countries, and Canada. The conversation revealed that safety was a concern in general in Syria, as expressed in the following quotes:

Even before the war, we did not feel safe in our homeland: the law, systems, and institutions were unpredictable and unjust.

Before the war in Syria, I was walking in the street, and I was always afraid of police (because of corruption) even though I have not done anything.

While leaders agreed that corruption was a significant and widespread issue when dealing with any state/government representative in Syria, they also pointed out that “after the war, Syria became even more unsafe–there could be bombs any time; you do not feel safe at all.” Another leader offered a personal account:

One day, my children and I were in the car, and we came to a checkpoint, and when the two groups were fighting, we saw how they shot each other. We tried to protect ourselves, but I knew my family and I were going to lose our lives. This experience continues to affect me – it is always in front of me – especially because my family members are still there.

The discussion also revealed that the sense of injustice in the transition country, such as Turkey, was related to safety even when physical safety was not threatened. Leaders shared the following thoughts:

Turkey was safe in some ways but not others – bombing was not a threat, but there was pressure to find work and make money.

When we evacuated from our homeland, like fled to Turkey, it is the same. for the Syrian people in Turkey, there is no justice from the system or from the people.

Some people in Turkey do not like someone strange to come to take their homes or to work in their factory.

The relationship between justice and safety was prominent in the discussion about Syrian leaders’ experiences in Canada. Some leaders suggested that “in Canada, there is justice, so there must be safety here” and that “there is justice more than in other countries.” Others felt that “in Canada, people respect each other, and there is respect between the government and people.”

One of the leaders elaborated:

Safety is the feeling of being comfortable in everything – in physical things and psychological things. In Canada, this is provided by equality, justice and the law – there aren’t any differences between people here. These things let people be comfortable and feel safe here.

The leaders acknowledged that “even here in a new country (Canada) where it is safe outside, it takes time to feel safe inside. You are away from your homeland, family and friends.” The physical safety felt in Canada did not mean psychological safety, as one of the leaders pointed out, “Although I feel that my family and I are now safer in Canada, a fear for the safety of my family still in Syria prevents me from feeling completely safe and at peace.” Another leader added:

When I came here, it was safe for my children and me, but every day I think about what happened to my family back home – what is on the news, what is on the phone. I am always expecting something bad will happen, so I am not feeling safe. When I compare my safety to the safety of my family, it feels unbalanced.

However, as the conversation continued, it became clearer that it was not only the anxiety about what was happening “back home” that was causing the feeling of unsafety. The leaders’ assumptions about Canada were altered as they gained life experiences in the country, causing them to feel less safe as they were confronted with a number of challenges. One leader said he initially felt safe in Canada, but that feeling is decreasing because of the pressures of living here, such as finding work and paying for housing. A female leader in the group expressed concern about children’s safety at school and the need to raise them to adapt and integrate. It became a focus of the discussion regarding leaders’ feelings of safety in Canada.

At this point of the discussion, the team member who was leading the introduction of the ADAPT module on safety introduced the types of psychological responses to the threats to safety and presented some research evidence. To make this research evidence accessible to the leaders, a summary of the research literature on each of the key domains of the ADAPT model was translated into Arabic and made available to the leaders for their background information as they lead their CLEGs. However, there was no expectation for leaders to present the content to the Syrian community members in their respective CLEGs. Some of the leaders used portions of the material in their CLEGs.

The introduction and discussion of each domain enhanced leaders’ knowledge from a scientific perspective and simultaneously developed research team members’ understanding of how the ADAPT model was viewed through the lens of Syrian culture, as well as through the lens of leaders’ lived experiences. As such, each domain’s name in Arabis and the meaning of the word was decided on through a group discussion based on personal and cultural interpretations. These co-constructed meanings served as new frames of reference through which the leaders examined their past and present experiences related to the five key domains of the ADAPT model. It is important to point out that critical evaluation and self-reflection on their experiences was only one aspect of the transformative learning process. An equally important aspect of the transformative learning process was the ability to take action about an issue based on self-reflection and previous assumptions (Mukhalalati and Taylor, 2019). The leaders’ discussion about possible actions was guided by the question: “How can we respond to these challenges in the community?”

While there was a consensus among the leaders that “the first step is they have to talk, say what is bothering them. We have to encourage them (community members),” some cautioned that “some people may be shy or hesitant to share their experiences” or that “talking may trigger the bad memories – if someone talks, the problem will develop.” The leaders then brainstormed factors to consider when supporting community members whose sense of safety had been threatened, listed here as:

• “The first piece is to help them understand themselves. They don’t have to talk about the trauma; they know that this is a result of what they have experienced, and their body is responding like they are still in that danger. This is helpful because it helps them to know that they are not going crazy.”

• “You should choose the right time to encourage them to talk.”

• “Talking about feelings and experiences is important, but sometimes the person doesn’t want to talk – you shouldn’t require them to talk.”

• “If you want someone to talk to, he has to feel safe with you and trust you.”

• “Privacy is an important factor…some people don’t want everyone to know their story.”

• “We can encourage people to accept and understand themselves and know that they are part of the community and have its support.”

The training session concluded with leaders taking turns with a final sharing opportunity called “takeaways from today’s discussion.” The sense of knowing and better understanding the ADAPT model and how it applies to their own and others’ experiences of trauma was common among the leaders:

• “Information about PTSD and trauma symptoms is clearer now.”

• “We now have more information, and it is clearer – we learned a lot today.”

• “We learn from each other; I learned about inside and outside safety concepts, PTSD and trauma symptoms.”

• “I understand my own reactions and experiences better.”

• “We learn good things from others’ experiences and opinions.”

• “It is good to share our stories and experiences.”

• “I learned how to deal with someone experiencing the effects of trauma.”

• “I learned that some people have experiences that threaten their safety.”

• “I didn’t know that people can forget but still have reactions – and now knows that people in these situations may need help. I can see this in my own experiences and understand them better.”

In terms of the critical self-evaluation of their experiences of safety in Canada, a shift could be noticed, as one of the leaders shared, “We left our country because of war and came seeking safety. If we remember that is the reason we came here, we can cope, but we have to remember that it is not heaven – there are problems here too.”

As this illustrative example demonstrates, the sessions focused on co-creating ADAPT modules involved a process of learning and exchange for both research team members and leaders. For leaders, these sessions offered knowledge of the ADAPT framework, a demonstration of group facilitation, and the experience of sharing and discussing each domain in the context of personal experiences so that they could lead their discussions and be empowered with the capacity to do so. Toward the end of the 5 module sessions, the leaders took turns facilitating in small groups to practice running their CLEGs in phase two of the project.

3.1.5. Leader feedback on preparation to facilitate CLEGs

The first phase of the project concluded with obtaining feedback on leaders’ experiences as well as their acquired knowledge and skills during the eight training sessions. Rather than a standard survey, this was a short feedback questionnaire for leaders to reflect on their acquired knowledge, skills, and confidence to run CLEGs, as well as to determine what supports they need going forward. This was developed in consultation with cultural brokers, who also translated the document from English to Arabic. We used the questionnaire as a starting point for discussion about moving forward with implementing CLEGs when all team members met to plan phase 2 activities.

The questionnaire included open-ended and Likert scale questions; the Likert scale questions ranged from 1–5, with 1 indicating “Very much no” to 5 indicating “Very much yes.” The Likert scale used word descriptors and emoticons so that leaders had written and visual means of interpreting the scale. Open-ended questions hoped to gather additional feedback on leaders’ acquired knowledge, skills, and ideas for improving the training and co-creating of CLEG facilitation materials. They also aimed to identify additional support needed during the second phase of the research project.

While the leaders’ feedback questionnaire was developed following a more traditional research process by academic and student members of the research team, we worked alongside the cultural brokers to identify and formulate the most culturally appropriate questions regarding the leaders’ experiences of the training and co-creating activities. Since the leaders were mostly fluent in English and cultural brokers were present at all meetings, it was determined that they could respond to the survey without difficulty, and the survey was implemented in English.

The responses from all leaders suggested that they felt empowered by the knowledge they gained. Nearly all leaders selected 5 for almost every Likert scale question. While one respondent selected 3 and another selected 4 for a question on self-care for leaders, leaders selected 5 for all other questions. Most open-ended questions were left blank because, as the leaders explained during the follow up meeting, they did not have anything else to add. Half of the leaders responded to the question asking about the most important learning from phase one, and a third gave feedback on additional supports they required to facilitate their groups successfully, such as using a projector. Questions about areas for further learning or suggestions to improve phase one activities were left blank by five of the six leaders who completed the survey. Leaders shared that they did not have any questions at the end of phase one, as they first needed to start their groups to gain a better sense of any gaps in their knowledge or understanding. Based on this feedback, a question was added to all focus group discussions in phase two, asking leaders to share if they had any questions, concerns, or requests to improve their facilitation or the quality of discussion within their group.

In summary, feedback from leaders on training and co-creation of CLEG facilitation materials showed that leaders felt confident facilitating community discussions around the five pillars of psychosocial adaptation. Leaders shared these details and exchanged additional facilitation ideas and guidance for future CLEG sessions with the rest of the research team.

3.2. Phase two

In phase two, the seven Syrian community leaders each led a CLEG that included members of the Syrian community. Reflecting the leaders’ identities and the diversity of the Syrian community, there were seven CLEGs in total (one women’s CLEG, one men’s CLEG, a youth CLEG, two seniors’ CLEGs, and two CLEGs with Kurdish participants). A total of 42 CLEG meetings were held by the leaders, involving 62 community participants. Each leader facilitated seven discussion sessions, one on each of the psychosocial domains of the ADAPT model and introductory and closing sessions. A focus group was held after each of these sessions, for a total of six focus groups during phase two. The purpose of the focus groups was to engage the community leaders, cultural brokers, and academic members of the research team in discussing key learnings about the needs, strengths, and challenges shared by participants in each CLEG, as well as possible solutions to their psychosocial needs and challenges. Field notes from phase one, and focus group data in phase two often contained both English and Arabic. Therefore, the Arabic excerpts of these documents were translated to English by bilingual research team members before analysis, such that all data was analyzed in English. Illustrative examples from the focus group following the CLEGs’ discussions of the ADAPT module on identity are shared below.

3.2.1. Evidence of empowerment: focus group discussions with leaders

During focus groups, each leader shared how they introduced the given domain; challenges and strengths that participants shared; solutions identified in their group; and a general evaluation of the CLEG session overall. This allowed leaders to share the strategies they used to introduce the domain and facilitate the discussion, reflect on the discussion within their group, and ask questions or share concerns or challenges. Focus groups were also an extension of the “training of trainers” from phase one; where the environment of sharing, reflecting, and exchanging ideas and experiences amongst research team members and Syrian leaders in focus groups further enhanced leaders’ capacity to lead future CLEGs and enhanced other team members’ understanding of Syrian experiences and the CLEGs. The deepened insights and new approaches to facilitating CLEGs in subsequent focus groups were evidence of leaders’ growth in terms of ability and confidence in facilitating their CLEGs.

At the focus groups, all leaders took turns sharing how they engaged participants of their CLEGs in reviewing the ADAPT model at each session and discussing the given domain in more detail. As explained by one leader, “I started by reminding the group of the rules, ADAPT model and modules. I asked if they had any questions, defined identity, and gave my personal experience.” However, the approaches and strategies leaders employed to lead these discussions differed. They also evolved as leaders continued to build their capacity to facilitate the CLEGs. For example, after the first CLEGs on the topic of safety had been completed, all leaders shared in the focus group that they had used the definition of safety that had been agreed upon during the training session on safety. One leader shared, “We gave them the key, safety is the key, and we opened the door for them.” He said that he “gave them the key” in the same way that he had learned in training during phase one, using the definition and explanation of safety that had been agreed upon at that time.

As the leaders gained more confidence in facilitating their CLEGs, they became more empowered to deviate from what was modeled to them during the early training and collaborative learning sessions in response to the needs of their particular CLEG. For example, at the fourth focus group after the CLEG discussions on the identity domain, most leaders shared that they had utilized different approaches to introducing and defining identity as this was a challenging concept to grasp. One leader, for instance, researched various definitions and understandings of identity, then combined these to create a definition that she felt included various facets of personal identity. Then, she asked participants to give their definitions based on their perception of what contributed to personal identity. At the focus group, the leader shared, “the definitions (from participants) were: identity is the land; the freedom; belonging to a place where I feel safe; language; earth; humanity; identity is everything.” Another leader used their identification card as a visual aid and asked participants to share what they felt represented something about their identity. The leader explained, “I took my identity card from my pocket, and asked them who knows the meaning of identity and what it includes.” When participants expressed confusion about the difference between identity and some of the other pillars of the ADAPT model, the leader was able to navigate this question effectively and offer clarity:

I told them yes, (attachment and relationships are) one part, but we want to go deep and know more about that topic (of identity). I tried to speak a little bit about the definitions of identity. Some are from the familial, career identity, which gives more information.

As these examples demonstrate, the leaders’ agency was in their approaches to adapting their learning about the ADAPT model from phase one to suit the dynamics of their group and their personal preferences and style. Leaders were also empowered with other aspects of leading their CLEG. For instance, some leaders chose to hold CLEG sessions in their homes or a familiar community location, and others selected the shared meal based on the personal preferences of their group members, including snack-type foods or a full meal. As leaders responded to queries and addressed questions about the ADAPT model and its pillars, they demonstrated the depth of their understanding of the model and their ability to engage the community members in conversations that utilized this knowledge in the process of deep self-reflection. The critical self-reflection also included mapping out possible actions in the areas which the community members identified as problematic. In the context of the project described here, these actions were framed as community solutions.

The leaders shared the solutions their CLEGs discussed after each focus group. For example, during the identity focus group, the leader of a female-only CLEG identified some solutions that could be implemented at the individual level. These included “teaching their children about their language, culture, and identity.” Participants of another group suggested getting involved in politics in Canada, as they felt that individual identity was associated with having political influence.

Other leaders shared several solutions their CLEGs participants offered that could be implemented at the community level. One leader shared that his group felt that:

If we can invite a person with the same experiences who has been here for 20 or 30 years with the same culture and traditions to talk about how they protect their culture and identity, maybe we would feel more comfortable if we hear from their experience.

Leaders of other groups shared similar community-level solutions to maintain their cultural identity. For instance, members of another CLEG expressed the importance of having a space where community members could come “to practice their culture, wear their clothes, and provide help learning their own language, Arabic. Like a cultural center.” Some solutions were less concrete, representing larger, overarching goals for their community. During the identity focus group, one such solution related to attaining unity and solidarity. The leader of the all-female CLEG shared that “unity is something (the participants) aim to achieve after getting education, in order to maintain language, heritage, and all of that.” Participants of this CLEG also suggested “open[ing] a business together for the Kurdish community, where individuals and the community can work and benefit (others at) the individual and community level.”

The discussion of solutions during focus groups provided the opportunity not only to share and discuss the solutions presented in the CLEGs but also to build on and expand these ideas. For example, leaders and research team members attending the identity focus group reflected on the relationship between political influence and identity and how a political voice could be manifested individually and within the Syrian community.

These discussions demonstrated participants’ and leaders’ readiness for action based on self-reflection. Their ideas and knowledge of how to act on these ideas testified to their empowerment at the individual and community levels as a result of the transformative learning they had been part of throughout the first two phases of this project.

4. Conclusion

This article has demonstrated how CLEGs, an innovative methodology grounded in CBPR principles and the application of transformative adult learning theories, could be used to empower immigrant communities who often “are positioned as simply passive ‘subjects’ of a study, objectified as heroes, framed as needy or to be pitied, or framed through deficit perspectives (e.g., lacking in knowledge, skills, and resources)” (Ngo et al., 2014, p. 2). CLEGs led by community leaders provided Syrian community members with a safe space to critically evaluate and self-reflect on their past and present experiences, frame their own narratives of trauma and exclusion, and identify solutions to support their adaptation in their new country. As a whole, our project also demonstrated how community-engaged faculty members could contribute to academic and community knowledge that can guide our collective action toward social justice and belonging in an increasingly divided society. More specifically, using a “train-the-trainer” approach to prepare community leaders to create and facilitate the implementation of CLEGs created an informal network that, because of the challenges in accessing community resources belonging to the host society (Ommeren et al., 2015), could provide support in dealing with the psychological stressors associated with early resettlement. Instead of relying solely on settlement organizations, the community leaders of the CLEGs created space for sharing common experiences, critically reflecting on them, identifying common community issues to tackle, and charting actions that could strengthen both the individuals and the community. In providing some evidence for Syrian community members’ and leaders’ agency, self-reliance, and self-determination, we are aware of the possibility that such findings can mask the persisting issues of exclusion and marginalization of refugees that occurs at individual, national, and global levels. While the structure of the CLEG discussions provided opportunities to engage in another important aspect of the transformative learning process–to take action about an issue based on self-reflection and previous assumptions (Mukhalalati and Taylor, 2019) - the discussions also revealed existing tensions rooted in existing power relationships, including systemic barriers and confronting prejudices and biases at both institutional and individual levels. We hope that the findings of this research contribute to bringing the societal discourse above the harmful constructs of refugees as helpless “victims” while at the same time raising awareness about the responsibilities the host societies have in confronting the underlying systemic conditions that perpetuate the exclusion of refugees.

Our research project demonstrated how CLEGs can be used as part of CBPR partnerships to bridge the gap between research and practice. As illustrated in this article, CLEGs can create conditions, processes, and resources that build on community strengths and, therefore, could potentially change the psychosocial adaptation of refugees and the overall outcomes of their integration into the host society. When empowerment is a crucial goal for refugees, they can make “external changes to relationships, situations, power dynamics or contexts” (Brodsky and Cattaneo, 2013, p.338) to become active agents and advocate for their resettlement needs. CLEGs are one methodological approach that can be used in other projects to achieve these goals.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because we did not obtain permission from participants or receive ethical clearance to share raw data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c29waGllLnlvaGFuaUB1YWxiZXJ0YS5jYQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (REB) 1. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for youths’ participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This project draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Study ID: Pro00081949).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J. Refugee Stud. 21, 166–191. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen016

Alberta Association of Immigrant Serving Agencies [AAISA] (2017). Alberta Syrian refugee resettlement experience study. Calgary: Alberta Association of Immigrant Serving Agencies.

Ali, H., and Ari, K. (2021). Addressing mental health and psychosocial needs in displacement: How a stateless person from Syria became a refugee and community helper in Iraq. Intervention 19, 136–140.

Bentley, J. A., Feeny, N. C., Dolezal, M. L., Klein, A., Marks, L. H., Graham, B., et al. (2021). Islamic trauma healing: Integrating faith and empirically supported principles in a community-based program. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 28, 167–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.10.005

Betancourt, T. S., Frounfelker, R., Mishra, T., Hussein, A., and Falzarano, R. (2015). Addressing health disparities in the mental health of refugee children and adolescents through community-based participatory research: A study in 2 communities. Am. J. Public Health 105, S475–S482. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302504

Brodsky, A. E., and Cattaneo, L. B. (2013). A transconceptual model of empowerment and resilience: Divergence, convergence and interactions in kindred community concepts. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 52, 333–346. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9599-x

Citizenship and Immigration Canada (2017). #Welcomerefugees: key figure. Ottawa, ON: Citizenship and Immigration Canada.

Coombe, C. M., Schulz, A. J., Brakefield-Caldwell, W., Gray, C., Guzman, J. R., Kieffer, E. C., et al. (2020). Applying experiential action learning pedagogy to an intensive course to enhance capacity to conduct community-based participatory research. Pedag. Health Prom. 6, 168–182. doi: 10.1177/2373379919885975

Corey, S., Corey, G., and Corey, C. (2014). Groups: Processes and practices. Belmont, CA: International Edition.

Donnelly, S., Raghallaigh, M. N., and Foreman, M. (2019). Reflections on the use of community based participatory research to affect social and political change: Examples from research with refugees and older people in Ireland. Eur. J. Soc. Work 22, 831–844. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2018.1540406

Fals Borda, O. (1988). Knowledge and people’s power: lessons with peasants in Nicaragua, Mexico and Colombia. New York, NY: New Horizons Press.

Fragkiadaki, E., Ghafoori, B., Triliva, S., and Sfakianaki, R. (2020). A pilot study of a trauma training for healthcare workers serving refugees in Greece: Perceptions of feasibility of task-shifting trauma informed care. J. Aggress. Maltreat 29:4. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2019.1662866

Georgis, R., Gokiert, R. J., and Kirova, A. (2018). “Researcher reflections on early childhood partnerships with immigrant and refugee communities,” in Collaborative cross-cultural research methodologies in early care and education contexts, eds S. Madrid, M. J. Akpovo Moran, and R. Brookshire (Oxford: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315460772-8

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada [IRCC] (2021). #WelcomeRefugees: key figures. Ottawa, ON: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., Becker, A. B., Allen, A. J., and Guzman, J. R. (2008). “Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles,” in Community based participatory research for health, 2nd Edn, eds M. Minkler and N. Wallerstein (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Jarvis, P. (2006). Towards a comprehensive theory of human learning. Lifelong learning and the learning society. Oxon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203964408

Kastner, M., and Motschilnig, R. (2022). Interconnectedness of adult basic education, community-based participatory research, and transformative learning. Adult Educ. Q. 72, 223–241. doi: 10.1177/07417136211044154

Kuriansky, J. (2019). A model of psychosocial support training and workshops during a medical mission for Syrian refugee children in Jordan: techniques, lessons learned and recommendations. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 18:4. doi: 10.1080/15289168.2019.1690925

Mertens, D. (2007). Transformative paradigm: mixed methods and social justice. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 212–225. doi: 10.1177/1558689807302811

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 74, 5–12. doi: 10.1002/ace.7401

Morrice, L. (2012). Learning and refugees: recognizing the darker side of transformative learning. Adult Educ. Q. 63, 251–271. doi: 10.1177/0741713612465467

Mukhalalati, B. A., and Taylor, A. (2019). Adult learning theories in context: A quick guide for healthcare professional educators. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/2382120519840332

Ngo, B., Bigelow, M., and Lee, S. J. (2014). Introduction to special issue: What does it mean to do ethical and engaged research with immigrant communities? Diaspora Indig. Minor. Educ 8, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/15595692.2013.803469

Ommeren, M., van Hanna, F., Weissbecker, I., and Ventevogel, P. (2015). Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian emergencies. East. Mediterr. Health J. 21, 498–502. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.7.498

Pearce, J., Mann, M. K., Jones, C., van Buschbach, S., Olff, M., and Bisson, J. (2012). The most effective way of delivering a train-the-trainers program: A systematic review. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 3, 215–226. doi: 10.1002/chp.21148

Peralta, K. J. (2017). Toward a deeper appreciation of participatory epistemology in community-based participatory research. PRISM 6:1.

Quosh, C. (2013). Mental health, forced displacement and recovery: integrated mental health and psychological support for urban refugees in Syria. Netherlands: War Trauma Foundation. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000012

Silove, D. (2013). The ADAPT model: A conceptual framework for the mental health and psychosocial programming in post-conflict settings. Intervention 11, 237–248. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000005

Steimel, S. (2017). Negotiating refugee empowerment(s) in resettlement organizations. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 15, 90–107. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2016.1180470

Taylor, E. W. (2007). An update of transformative learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999-2005). Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 26, 173–191. doi: 10.1080/02601370701219475

Wallerstein, N., and Duran, B. (2008). “The conceptual, historical, and practice roots of community based participatory research and related participatory traditions,” in Community Based Participatory Research for Health, 2nd Edn, eds M. Minkler and N. Wallerstein (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 25–46.

Yohani, S. (2018). Syrian mental health support and training project. Final report submitted to Catholic Social Services. Edmonton, AB: Multicultural Health Brokers Cooperative.

Keywords: empowerment, refugees, community-based participatory research, psychosocial adaptation, transformational paradigm, community engagement, mental health

Citation: Yohani S, Kirova A, Georgis R, Gokiert R, Taylor M and Tahir S (2023) Creating community learning for empowerment groups: an innovative model for participatory research partnerships with refugee communities. Front. Educ. 8:1164485. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1164485

Received: 12 February 2023; Accepted: 28 August 2023;

Published: 26 September 2023.

Edited by:

Gretchen Brion-Meisels, Harvard University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sónia Vladimira Correia, Lusofona University, PortugalKathy Bickmore, University of Toronto, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Yohani, Kirova, Georgis, Gokiert, Taylor and Tahir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sophie Yohani, c29waGllLnlvaGFuaUB1YWxiZXJ0YS5jYQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Sophie Yohani

Sophie Yohani Anna Kirova1†

Anna Kirova1† Rebecca Georgis

Rebecca Georgis Rebecca Gokiert

Rebecca Gokiert