94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 17 May 2023

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1154356

This article is part of the Research TopicGender-Specific Inequalities in the Education System and the Labor MarketView all 11 articles

In this article, we examine how the rising proportion of academic families across cohorts affects sons’ and daughters’ tertiary educational attainment in the process of educational expansion. Using data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), we focus on West Germany and examine whether the upgrading of the educational composition of families across cohorts has particularly contributed to daughters catching up with and even overtaking sons in tertiary educational attainment over time, or whether daughters and sons have benefited equally. In particular, we ask whether the rise of academic families, who are assumed to have stronger gender-egalitarian attitudes toward their children, has contributed to daughters faster increase in tertiary education compared to sons. Our empirical analysis shows that the long-term upgrading of families’ education across cohorts has in a similar manner increased tertiary educational attainment of both sons and daughters. Thus, women’s educational catch-up process cannot be explained by the greater gender-egalitarian focus of academic parents. Rather all origin families, independent of their educational level, are following the same secular trend toward more gender egalitarianism. We also examine to which extent highly qualified mothers serve as role models for their daughters. We find that academic mothers do not serve as particular role models for their daughters. Rather mother’s education is equally important for both sons’ and daughters’ success in higher education. Finally, we show that the rising proportion of academic families across cohorts is connected to a rising proportion of downward mobility for both sons and daughters. However, the share of upward mobile daughters from non-academic families is converging with that of sons.

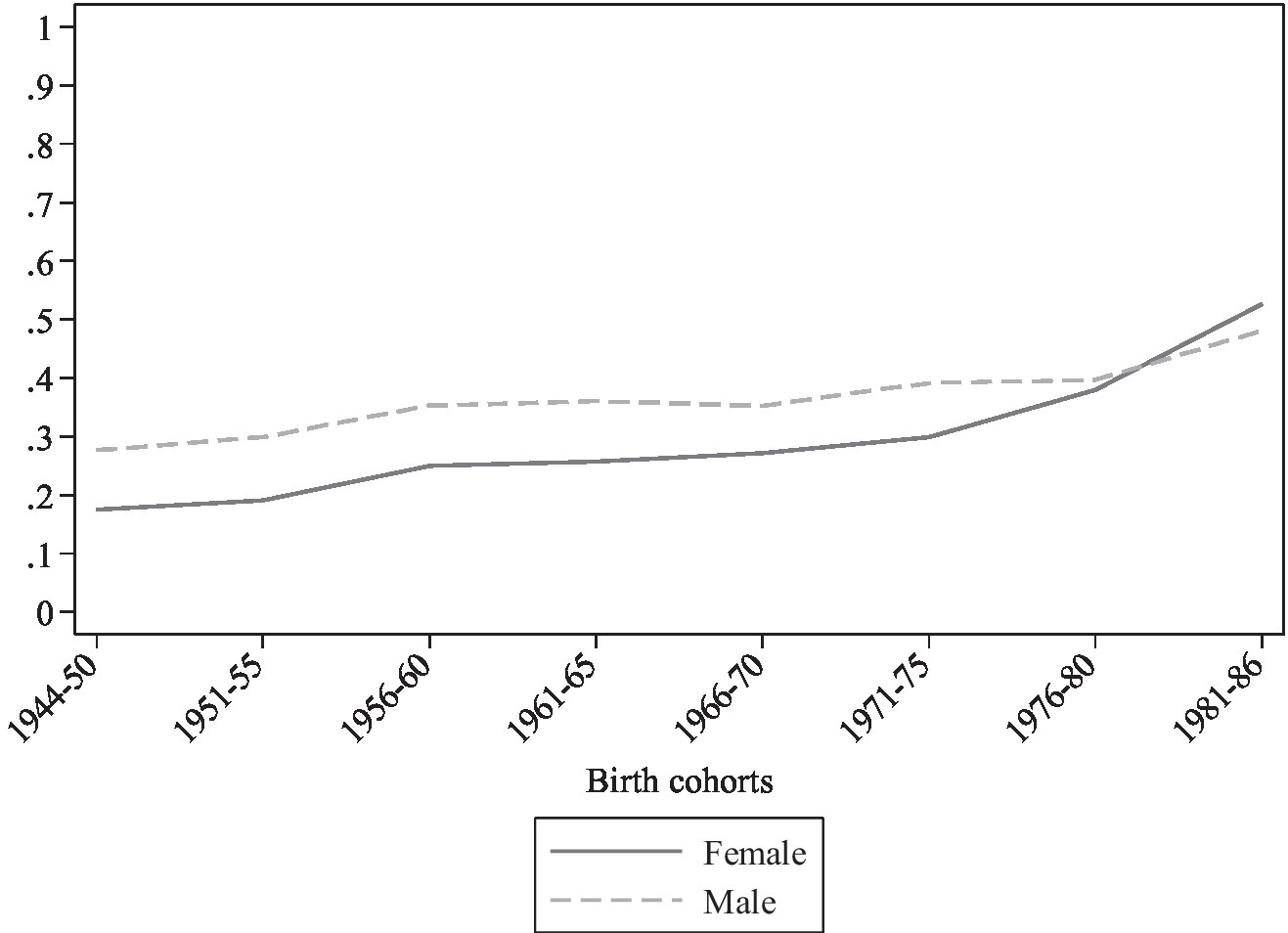

An important goal of policymakers in the process of educational expansion in West Germany was to reduce gender inequalities in education (Hadjar, 2019). About 28% of men and only 17% of women in the “1944–1950” birth cohort acquired a tertiary degree [Figure 1, percentages are based on data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS)]. From the “1944–1950” birth cohort to the “1981–1986” birth cohort, tertiary educational attainment increased markedly for both men and women in West Germany. In the “1981–1986” birth cohort, these proportions increased to 53% for women and to 48% for men. Thus, during the observation period, women’s tertiary educational attainment increased by 36% points and men’s by only 20% points. Therefore, the gender gap in tertiary education has steadily narrowed, and in the youngest birth cohort, women have even slightly surpassed men in terms of tertiary education. This development is also confirmed by other studies on Germany, which show that women have caught up with men in terms of educational attainment and have even overtaken them in tertiary educational degrees (Becker and Müller, 2011; Helbig, 2013).

Figure 1. Changes in males’ and females’ tertiary education across birth cohorts in West Germany. Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

For Germany, many studies have examined this gender gap reversal by focusing on gender-specific changes in cost–benefit evaluations at the micro level (Becker and Müller, 2011; Helbig, 2012; Becker, 2014). However, these models provide an incomplete picture of the full process of educational growth and do not consider how the upgrading of the intercohort composition of parents’ education may have affected changes in educational attainment of men and women across cohorts (Winsborough and Sweet, 1976; Mare, 1979; Blossfeld, 2020, 2022). In this paper we consider both the macro-level upgrading of parental education across cohorts and the micro-level changes in educational opportunities of sons and daughters. We use parental education as a measure of intercohort compositional changes of social origin because we want to examine the overall effect of parental education and other parental characteristics such as social class and income temporally lag behind parental education (Pfeffer, 2008). We rely on parental education because we are interested in examining the long-run momentum of educational expansion, which means that we want to examine how an increase in academic parents across cohorts due to an expansion of educational places in upper secondary and tertiary education in the parental generation leads to a further increase in the educational attainment of their daughters and sons. What further supports the purposefulness of our approach is that it is a well-established empirical finding that parental education, relative to other parental resources, has the strongest impact on children’s educational outcomes (Marks, 2008; Pfeffer, 2008; Bukodi and Goldthorpe, 2013; Blossfeld, 2019).

From a theoretical perspective, this macro–micro analysis is important because it allows to explore alternative explanations for why women have caught up with men in higher education. In particular, the increasing share of academic families at the macro level, which are thought to have more gender egalitarian attitudes, and the increase of mothers with a tertiary degree at the macro level, who can act as role models for their daughters, may be important for gender-specific changes in educational attainment. However, our analysis also allows us to study whether men and women are similarly affected by changes in the composition of social origin. In addition, we empirically explore whether changes in the share of educationally downward mobile sons and daughters from highly educated families develop similarly for both genders in Germany when the at-risk population for downward mobility (the share of children from academic families) rises across cohorts. Conversely, we ask whether the upward mobility of sons and daughters from non-academic families changed as the educational distributions of families changed across cohorts.

Past research has examined the consequences of changes in the social origin structure on children’s growth in educational attainment, without further distinguishing between males and females in Germany (Diekmann, 1982; Köhler, 1992; Blossfeld, 2020, 2022; Helbig and Sendzik, 2022). One seminal study by Ziefle (2017) focused only on women and showed that improvements in the educational structure of parents have increased daughters’ higher education entrance certificates in the youngest birth cohorts in Germany. What is still missing in the literature is a study that provides a direct comparison between genders. We still do not know whether changes in educational background composition across cohorts may have contributed to women catching up with men across cohorts, or whether men and women have benefited in similar ways in their growth in educational attainment (McDaniel, 2012, 592). Using retrospective data from the Adult Cohort (SC6) of the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) this article aims to close this gap in the literature.

In our analysis we concentrate on West Germany as from an international comparative perspective, it experienced a strong educational expansion in upper secondary and tertiary education since the 1960s (Blossfeld et al., 2017). Thus, the educational distributions of children and their parents have changed considerably since the 1960s (Köhler, 1992; Ziefle, 2017; Blossfeld, 2020; Pollak and Müller, 2020). In particular, the educational composition of mothers has dramatically improved (Blossfeld, 1993). West Germany is also known for its marked link between social origin and children’s educational attainment (Pfeffer, 2008). In this paper, tertiary education includes degrees from both universities of applied sciences and traditional universities. We focus on higher education because it is the fastest growing educational attainment level in West Germany nowadays. Tertiary certificates also typically provide access to top occupational positions with high earnings, strong career opportunities, and more job security in the West German labor market (Mayer et al., 2007). West Germany is also an interesting case study because returns to higher education in the labor market have remained fairly stable or even increased across cohorts (Becker and Blossfeld, 2017; Bukodi et al., 2020).

The article is structured as follows: We begin with an outline of the theoretical model that attempts to integrate macro- and micro-level changes in sons’ and daughter’s tertiary educational attainment. After describing the data, variables and methods, we present the empirical findings and demonstrate how the various macro- and micro-level interactions lead to new gender-specific outcomes of higher education. Ultimately, we summarize our findings and draw some more general conclusions.

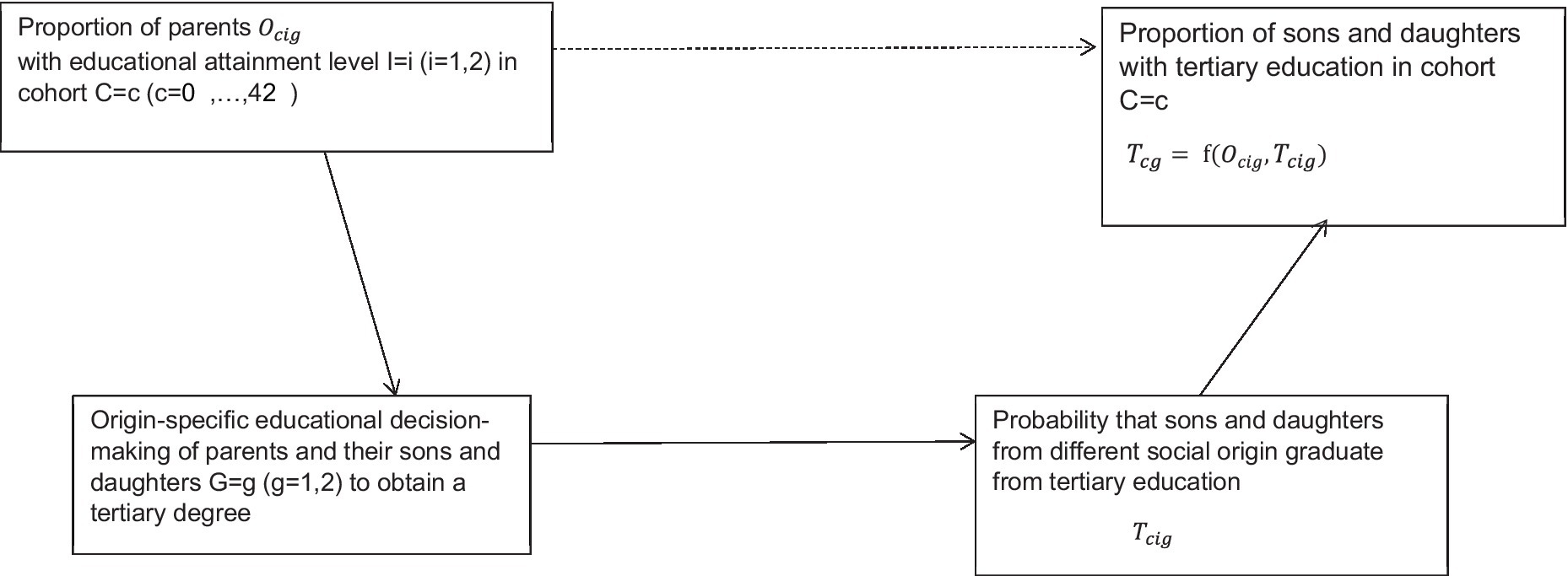

During the last few decades, not only men’s and women’s educational attainments have markedly increased across birth cohorts, but—as a consequence—the educational composition of parents has improved across cohorts in the process of educational expansion. This paper examines the extent to which this changing composition of parental education across cohorts has contributed to daughters catching up to and overtaking sons in terms of tertiary education, or the extent to which both genders have benefited similarly. The relevance of the macro-level change in educational background composition across cohorts on sons and daughters changes in the distributions of tertiary education cannot only be studied at the macro level (see Figure 2), since this macro-level analysis would be exposed to an ecological fallacy. The relevance of the macro-level change in educational background composition has to be traced via the micro-level educational opportunities of various social groups. In other words, the relevance of the upgrading of parental education across cohorts is dependent on the educational opportunities of sons and daughters and their changes across cohorts at the individual level (see Figure 2). The following three micro-level conditions are important for our analysis and are set into the context of a changing composition of parental education at the macro level:

Figure 2. Macro–micro–macro model showing how changes in the distribution of parents across cohorts and changes in educational decision-making, are related to changes in tertiary educational attainment of sons and daughters across cohorts. Author’s own presentation.

It is well known that higher educated parents typically provide better learning conditions for their children at home (Bukodi and Goldthorpe, 2013; Jackson, 2013). Highly educated parents possess academic qualifications that enable them to better support their children’s cognitive development throughout their educational careers, which promotes their sons’ and daughters’ opportunities for higher educational attainment (Bukodi and Goldthorpe, 2013; Jackson, 2013). This effect is commonly referred to as the primary effect of social origin (Boudon, 1974). Moreover, academic families are more likely to send their children to upper secondary schools and institutions of tertiary education, even if their children have comparable educational achievements as children from non-academic parents (secondary effect; Boudon, 1974). According to the status maintenance principle and prospect theory privileged families strive to pass on their advantageous positions to their children, as intergenerational downward mobility would be more painful for them (Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997; Kahneman, 2011). Cultural reproduction theorists assume that children from all educational family backgrounds take advantage of educational expansion, but that relative differences between the educational origin groups remain (Bourdieu, 1973; Shavit and Blossfeld, 1993). In our empirical analysis, we therefore expect that children from all educational origins may have benefited from educational expansion, but that children from academic families are generally more likely to attain a tertiary degree than children from less educated families. If we put this micro level theory into a context of an increasing proportion of academic families across cohorts at the macro level, we expect that the share of children with tertiary education from this origin group is increasing, even if relative differences in the educational decisions of families from different social origin groups remain (see Figure 2, Hypothesis 1).

However, several theories suggest that educational decision-making within different social origin groups may have changed over time. According to modernization theory (Lenski, 1966; Treiman, 1970), meritocratic principles gained importance in the education system in modern societies. This means that especially gifted children from disadvantaged social origins should increasingly earn a tertiary education degree across cohorts and that inequality of educational opportunities should decrease. In addition, the costs of education have decreased (e.g., school fees have been abolished, compulsory schooling has been extended, and the expansion of Gymnasiums and higher education institutions has shortened the geographical distances of children to higher education institutions) in most modern societies (Breen et al., 2009). Thus, children from non-academic families should have benefited in particular from these structural developments. If we again set this micro level theory into a context of a changing social origin structure, where fewer families have a non-academic family background, we assume that their share among the tertiary graduates will not change much or even decline across cohorts (Hypothesis 2).

In contrast, cultural reproduction theory (Bourdieu, 1973) predicts also that children from academic families are the major beneficiaries of educational expansion because they take advantage of the increasing supply of places in secondary schools and higher education institutions much more effectively than children from non-academic families. Putting this micro level theory into a context of a social structure with a rising share of academic families, we expect that a particularly high share of children among the tertiary graduates comes from an academic family background across cohorts (Hypothesis 3).

The educational upgrading of the social origin structure could also have consequences for gender-specific changes in tertiary education. First, according to the gender-egalitarian perspective, academic families have more egalitarian attitudes toward their children’s educational attainment, so that their daughters have relatively better educational opportunities than daughters from non-academic families (Buchmann and DiPrete, 2006; Helbig, 2012). In our empirical analysis, we therefore expect that the compositional shift toward more academic families across cohorts could lead to a more rapid catch-up of women in tertiary education relative to men (Hypothesis 4).

Second, the declining gender inequality between sons and daughters could also be reinforced by mothers’ own growing higher educational attainment. According to the gender role model perspective, mothers serve as examples for their daughters, which is assumed to affect their educational aspirations (Rosen and Aneshensel, 1978; Korupp et al., 2002; Buchmann et al., 2008). If mothers increasingly hold tertiary degrees across cohorts, this should in particular improve their daughters’ opportunities of obtaining a tertiary degree (Ziefle, 2017, 53). In our empirical analysis, we therefore expect that the rise in academic mothers will promote in particular female higher education (Hypothesis 5).

However, there are four general trends of increasing benefits of higher education for women, which should affect women from all social origin groups to a similar extent (Becker and Müller, 2011). First, there is a shift in the occupational structure from relatively unskilled male production jobs to skilled and highly skilled female administrative and service positions (Busch, 2013; Becker, 2014; Witte, 2020). Second, there is a secular liberalization of gender role perceptions in the whole society (DiPrete and Buchmann, 2013; Knight and Brinton, 2017; Gallie, 2019). Both developments should have led to increasing investment in education by women, rising female labor force participation, and a shift in the family division of work from the traditional male-breadwinner model to a secondary earner, dual career or even female breadwinner model (Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997; Blossfeld and Drobnic, 2001; DiPrete and Buchmann, 2013; Klesment and Van Bavel, 2017). As a result, across cohorts, women’s educational attainment and earnings have become increasingly pivotal to overall family income (Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997; Blossfeld and Drobnic, 2001; Haupt, 2019). Third, women in the older birth cohorts often married up in educational terms, but as education has expanded, women who invest more in their education have a higher likelihood to find a similarly highly educated partner within their networks in school and in the labor market than women with less education today (Blossfeld and Timm, 2003; Mare, 2016). Fourth, high divorce rates and the rising separation rate of consensual unions, as well as the growing proportion of single mothers increase the incentives of women to achieve greater economic independence through higher educational attainment (DiPrete and Buchmann, 2013; Zagel and Breen, 2019). In sum, based on these reasons, we expect women, to increasingly invest in higher education across cohorts, regardless of their social background (Hypothesis 6).

Finally, within the framework of our analytical macro–micro–macro model, we can analyze the extent to which the rising proportion of academic families at the macro level (whose children are at risk for downward mobility) and the changes in inequality of educational opportunities at the micro level affect the shares of educationally downward mobile sons and daughters differently (Goldthorpe, 2016). Conversely, we are able to examine how the declining proportion of non-academic families at the macro level and their change in educational opportunities at the micro level to attain an academic degree are related to sons’ and daughters’ upward mobility.

In our study, we use data from the Adult Cohort (SC6) of the NEPS1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011). This longitudinal survey employs a two-stage sample selection design with municipalities as primary and individuals as secondary sampling units (Blossfeld and Roßbach, 2019). The Adult Cohort of the NEPS provides annually updated retrospective information on the detailed educational histories of men and women born in Germany between 1944 and 1986. It is therefore a particularly suitable data source for the analysis of long-term changes in gender-specific educational inequalities in West Germany. We include 10 waves of the NEPS in the empirical analysis, where the latest was collected in 2017 and 2018. Since we are interested in tertiary degrees, we only include individuals aged 30 and older. This selection of cases has yielded an analysis sample of 8,828 respondents, including 4,421 (50.08%) sons and 4,407 (49.92%) daughters.

To describe the change in the distribution of parental education across cohorts at the macro level and to analyze changes in tertiary educational attainment by social origin at the micro level, we distinguish between academic and non-academic parents. We use the dominance approach (Erikson, 1984) to define the educational level of the family of origin. This means that the highest reported educational attainment of either the father or the mother is used to determine the educational position of the whole family. In addition, we use the individual educational levels of mothers and fathers in some analyses. We distinguish the following two parental educational levels coded as dummy variables:

1. Non-academic parents without a tertiary educational degree are coded as (1). Parents with are tertiary degree are assigned the value (0) in the empirical analysis.

2. Academic parents who have graduated from a traditional university or a university of applied sciences receive the value (1). Parents with less education are coded with the value (0).

An important variable for examining long-term changes in the social origin structure and changes in the opportunities of sons and daughters to earn a tertiary degree at the micro level is birth cohort. We tested several ways to model the cohort trends including birth cohort dummy variables and found that changes in tertiary education are best represented by a linear trend across cohorts. This cohort trend variable has a range between 0 for the “1944 birth cohort” and 42 for the “1986 birth cohort.”

To examine gender differences in tertiary educational attainment, we include the dummy variable female in our analyses [females are coded as (1)].

As shown in Figure 2, we use the bathtub model made famous by Coleman (1990) as a simple heuristic tool to show how changes in sons’ and daughters’ growth in tertiary education might be generated by two distinct mechanisms of social change: (1) the upgrading of the parental educational structure at the macro level and (2) the changes in gender-specific educational opportunities of sons and daughters from different educational families at the micro level. Figure 2 reveals how the macro-level upgrading of resources of parents from non-academic to academic education I = i (i = 1,2) across cohorts having daughters and sons G = g (g = 1, 2), together with micro-level changes in gender-specific inequality of educational opportunities produce changes in the proportion of tertiary education of sons and daughters across cohorts C = c (c = 0,…,42) as a matter of simple aggregation. Mathematically, the gender-specific proportions of daughters and sons with tertiary degrees across cohorts can therefore be expressed as the weighted sum of the changes in the educational composition of families across cohorts at the macro level and the changes in gender-specific inequality of educational opportunities at the micro level across cohorts (see for a similar approach Diekmann, 1982; Mare and Maralani, 2006).

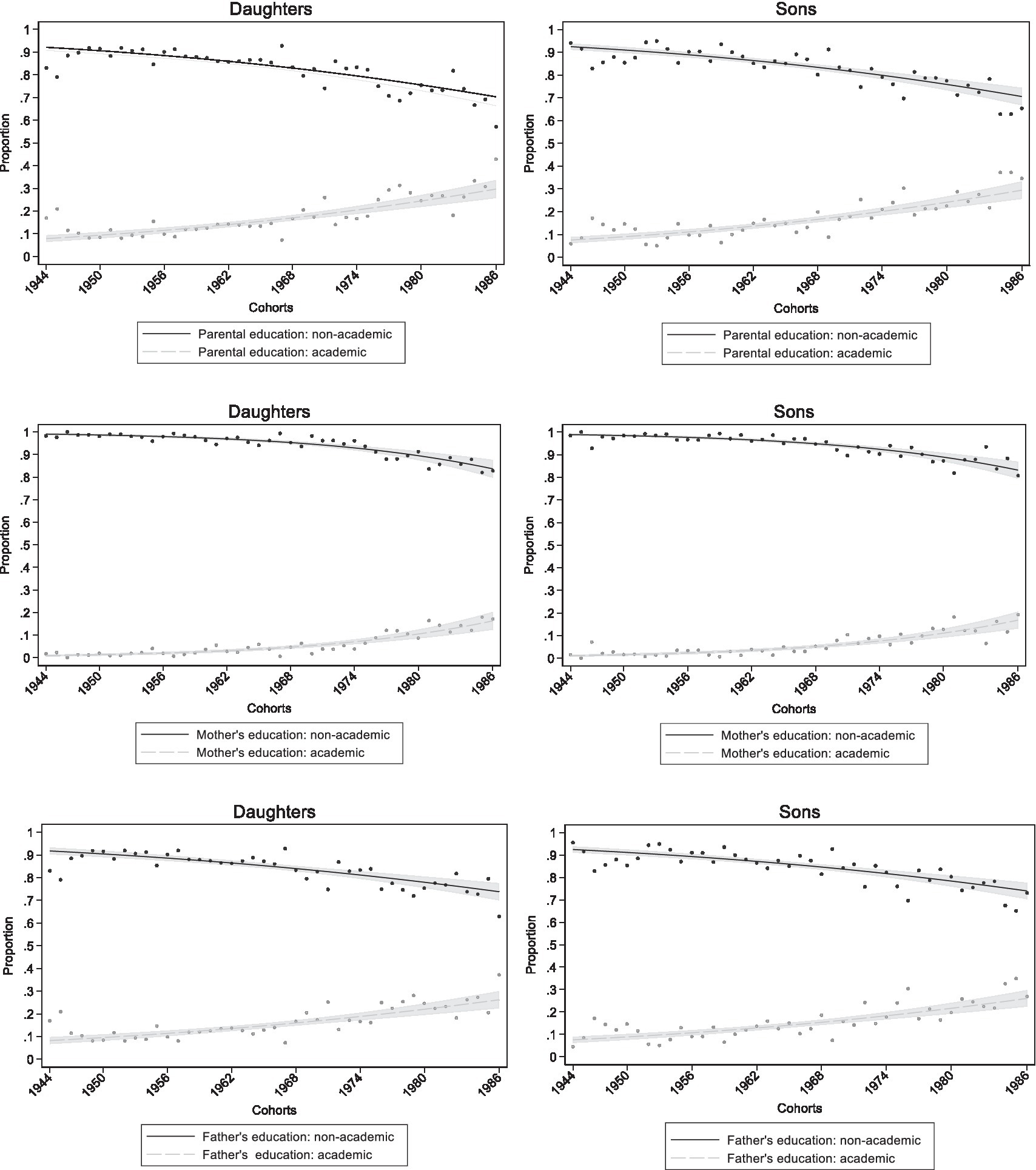

The gender-specific proportions of families with non-academic or academic education in each cohort at the macro level are estimated by a binary logistic regression model for sons and daughters that includes only the cohort trend as the independent variable. The cohort trend reflects changes across the single cohorts very well (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Change in the proportions of fathers, mothers and families with academic and non-academic education (parental education according to the dominance approach in 1st row, mother’s education 2nd row, father’s education 3rd row) for daughters (left panel) and sons (right panel) with observed and smoothed estimated probabilities using a logistic regression model. Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

At the micro level, the social origin-specific probabilities of sons and daughters to complete tertiary education are estimated by a binary logistic regression model with a covariate row vector (including social origin, cohort trend, being female and several interaction terms) and a parameter column vector [see Equation (2)]:

with c = 0,…,42; i = 1,2 and g = 1,2.

is 1 if sons or daughters have a tertiary education as their highest educational attainment and 0 if sons or daughters do not have a tertiary education as their highest educational attainment.

To investigate how tertiary degrees of sons and daughters (G = g) are determined by the two social origin groups (I = i) across cohorts (C = c), we calculate the two proportions, which combine the macro and micro developments across cohorts:

Considering tertiary educational attainment, only sons and daughters of academic parents can be downwardly mobile. Therefore, we additionally calculate the proportion of sons and daughters who were downwardly mobile in each cohort as the product of the proportion of academic families and the probability to be downwardly mobile in each cohort.

Conversely, only sons and daughters from non-academic families can be educationally upwardly mobile in terms of tertiary education. The estimated proportion of sons and daughters who were upwardly mobile in each cohort is the product of the proportion of non-academic families and their probability to be upwardly mobile in each cohort.

We begin with a description of the intercohort change in the educational composition of families during a period of massive educational growth in West Germany. Figure 3 shows the changes in the observed and predicted probabilities (with confidence bands) of parents with non-academic and academic education for sons and daughters. We plot the observed probabilities as dots and the estimated probabilities as lines. In the upper part of Figure 3, we show the probabilities based on Erikson’s (1984) dominance principle, where the highest educational position of both parents defines the educational position of the family. The middle and bottom parts of Figure 3 reveal the changes in probabilities based on mother’s and father’s education, respectively. The predicted probabilities and their confidence bands (shadow areas) are based on binary logistic regression models. As the plots in Figure 3 show, the estimated probabilities based on a linear cohort trend represent the observed probabilities very well.

The upper panel in Figure 3 shows that the evolution of the educational composition of families (based on the dominance approach) is quite similar for both sons and daughters. Across cohorts, there is a clear decline in families with non-academic education (from 92% in the “1944 birth cohort” to 71% in the “1986 birth cohort” for sons and for the same birth cohorts from 92% to 70% for daughters). The share of academic families has increased dramatically across cohorts (from 8% to 29% for sons and from 8% to 30% for daughters).

The middle panel of Figure 3 presents the changes in the composition of mothers with non-academic and academic education across cohorts. We see for both sons and daughters that the proportion of children born to mothers with non-academic education has declined across birth cohorts (from 99% to 83% for sons and from 99% to 84% for daughters). Conversely, the proportions of sons and daughters who have an academic mother have increased sharply across cohorts (from 1% to 17% for sons and from 1% to 16% for daughters). Overall, the picture of change in the educational composition of mothers across cohorts looks quite different from the upper panel of Figure 3, where families’ education is measured using the dominance approach. Mothers have caught up in their educational attainment relative to fathers across cohorts. However, the basic development of the educational composition of mothers is quite similar for sons and daughters.

The bottom panel of Figure 3 shows the change in the educational composition of fathers for sons and daughters across cohorts. The graphs look the same for sons and daughters and are very similar to the graphs in the upper panel based on the dominance approach. This means that the dominance approach partially hides the catch-up process of mothers, as fathers are still more likely to have the higher educational attainment within families. We also see that the proportion of non-academic fathers has decreased (from 92% to 74% for sons and daughters) and that the proportion of academic fathers has increased across cohorts (from 8% to 26% for sons and daughters).

Based on these changes, we conclude that educational growth has led to a dramatic upgrading of the educational composition of parents across cohorts. Sons and daughters in the youngest birth cohorts are much more likely to stem from academic family backgrounds than earlier birth cohorts. Our analysis below will show to which extent the micro-level mechanisms have changed as well. However, even if the micro-level mechanisms of origin-specific decision-making persisted across cohorts, these intercohort compositional changes alone should lead to a higher average educational attainment for children and more gender equalization in tertiary education. According to status maintenance and prospect theory, the growth in the composition of families toward higher-educated ones should lead to an increase in tertiary educational demands for sons and daughters. And the gender-egalitarian perspective expects increasing educational attainment for daughters from academic families as the share of families with tertiary degrees increases across cohorts. In addition, the mothers as role model argument suggests that more academic mothers serve as examples for their daughters in terms of higher education. Thus, if the proportion of academic mothers increases, their daughters should also increase their tertiary educational attainment across cohorts. We will examine these micro-level claims in more detail in the next section, paying particular attention to daughter’s catch-up in tertiary education.

We first focus on the dominance approach of social origin and estimate several logistic regression models. In a stepwise approach, the models include the cohort trend, a dummy variable for origin families (non-academic versus academic education), a dummy variable for females, and all theoretically relevant interaction terms.

Model 1 in Table 1 shows, as expected, that there is a statistically significant and positive cohort trend. This means that in the process of educational expansion, the opportunities to obtain a tertiary degree increase for all children at the micro level, regardless of gender and family origin. There are also marked differences by parental education. For example, sons and daughters from academic families have a much higher probability of attaining a tertiary degree at the micro level. We also included an interaction effect of “social origin and cohort trend” in Model 4 of Table 1, which is not statistically significant. Thus, inequality of educational opportunity did not change much across cohorts. This empirical finding does not support Hypothesis 2, which expects a decline in educational inequality across cohorts, nor Hypothesis 3, which partly expects an increase in educational inequality across cohorts. Model 2 in Table 1 shows that the dummy variable “female” has a statistically significant coefficient of −0.857. Thus, in our sample, women are on average significantly less likely than men to earn a tertiary degree. However, Model 2 of Table 1 also reveals a statistically significant coefficient of 0.02 for the interaction term of “cohort trend and female.” This means that the advantage of men in tertiary educational attainment declines across birth cohorts (−0.857 + 0.02*0 = −0.857) and even disappears for the youngest birth cohort (−0.857 + 0.02*42 = −0,017). In addition, Model 4 of Table 1 shows that the first-level interaction term “female and academic parents” and the second-level interaction term “cohort trend, female and academic parents” are not statistically significant. Thus, there seem to be no differences in educational opportunities between sons and daughters from differently educated families. This finding is not consistent with Hypothesis 4, which predicts that daughters from academic families have an advantage in obtaining a tertiary degree over daughters from non-academic families. Overall, these empirical findings are in line with Hypothesis 6 and corroborate previous empirical research which suggest that the catching-up process of females in education is the result of increasing benefits of tertiary education for all women (Legewie and DiPrete, 2009; Becker, 2014). The liberalization of gender role norms, the increasing labor market participation of women, the rising importance of women’s contribution to total family income, the trend toward educational homogamy, and the rising divorce and separation rates all appear to have increased women’s benefits from investing in tertiary education across cohorts, regardless of their social origin (Legewie and DiPrete, 2009; Becker, 2014).

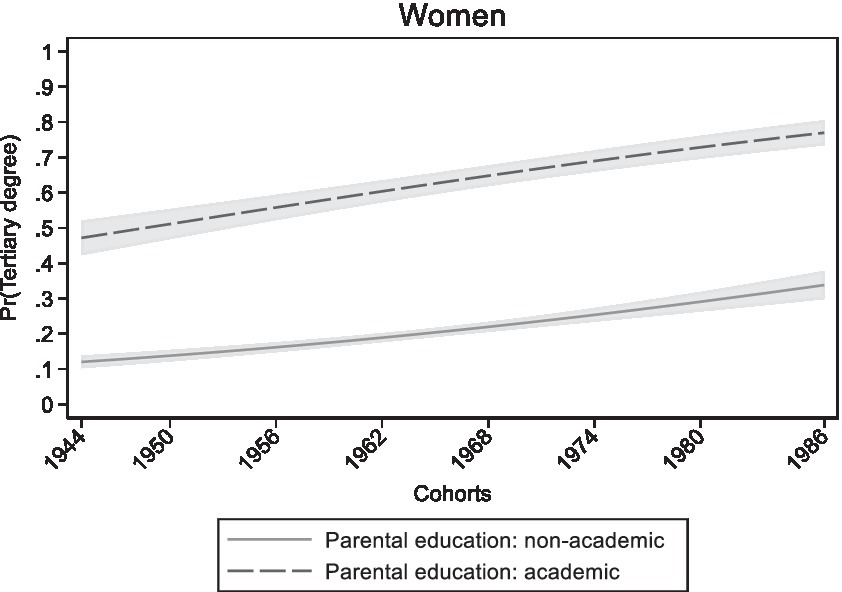

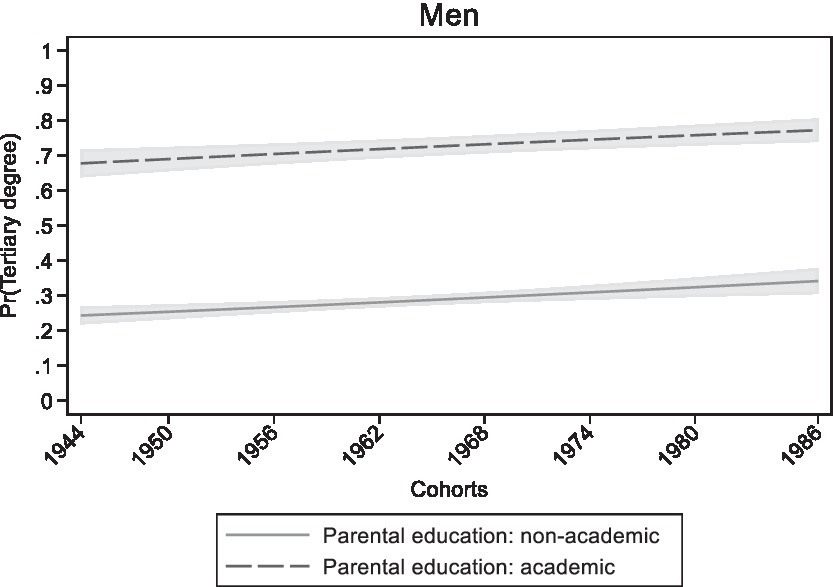

Because the interaction terms with the cohort trend in Models 3 and 4 of Table 1 are not significant, we use Model 2 to describe the nonlinear relationships between the independent and dependent variables in the logistic regression model. Figures 4, 5 show the estimated probabilities of attaining a tertiary degree (and their confidence bands) for sons and daughters of the two social origin groups across cohorts. Figure 4 shows an impressive increase in the estimated probabilities of attaining a tertiary degree for women of the two social origin groups over the observation period (birth cohorts “1944” to “1986”). Women from academic families not only have the highest probability of obtaining a tertiary degree, but they also experience the largest gains in tertiary education across cohorts. Their probability to obtain a tertiary degree has risen from 47% in the “1944 birth cohort” to 77% in the “1986 birth cohort.” Comparing this probability with the probability of sons from academic families in Figure 5, we find that daughters among the oldest birth cohorts have lower probabilities to complete a tertiary degree. This finding is not in line with Hypothesis 4, which claims that the probabilities of obtaining a tertiary degree should be quite similar for sons and daughters from academic families even for older birth cohorts. For daughters from parents with non-academic education, the probability has also increased, from 12% in the “1944 birth cohort” to 34% in the “1986 birth cohort.” Thus, the higher the parental education of daughters, the higher the increases in tertiary educational attainment. However, these increases have nothing to do with differences in gender-specific behavior of better educated origin families (the gender-egalitarian perspective). Rather, they are a consequence of different social origin mechanisms that also apply to sons.

Figure 4. Estimated probabilities of daughters with confidence bands to obtain a tertiary degree for the two social origin groups (estimation is based on binary logistic regressions). Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

Figure 5. Estimated probabilities of sons with confidence bands to obtain a tertiary degree for the two social origin groups (estimation is based on binary logistic regressions). Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

Figure 5 presents the changes in the probabilities of obtaining a tertiary degree for sons coming from non-academic or academic families across cohorts (“birth cohort 1944” to “birth cohort 1986”). Compared to daughters, these probabilities increased only slightly for the two social origins. For sons from academic parents, the probabilities increased from 68% in the “1944 birth cohort” to 77% in the “1986 birth cohort.” For sons from non-academic families, they increased from 24% in the “1944 birth cohort” to 34% in the “1986 birth cohort.” Thus, in contrast to women, men were not able to increase their tertiary educational attainment as much during this period of massive educational expansion. This suggests that daughters in particular, regardless of their educational family background, have benefited greatly across cohorts from changing gender roles in modern societies, which is in line with Hypothesis 6.

Finally, in Appendix A1, we briefly examine whether mother’s education is significantly more important for daughters than for sons. We include mother’s and father’s education separately into the binary logistic regression model in Appendix A1. In addition, we also introduce interaction terms for “mother’s education and female” and “father’s education and female,” but these turn out to be not statistically significant. We see that both mother’s and father’s educational resources are statistically significant for both daughters’ and sons’ tertiary educational attainment. This finding does not support Hypothesis 5, which expects that mother’s serve as role models for their daughters and their educational resources are therefore particularly important for daughters. Moreover, this analysis reassures us that it is appropriate to operationalize social origin using the dominance approach for the enormous catching-up process of mothers in education that we saw in the middle panel of Figure 3.

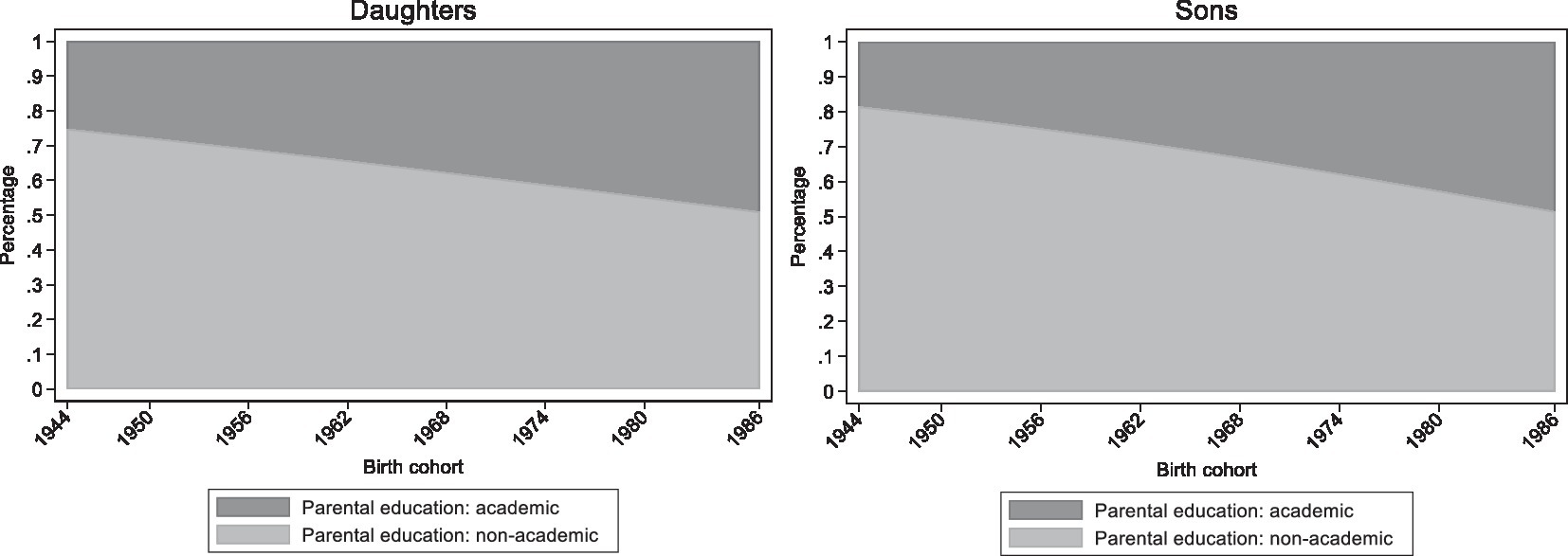

In Figure 6, we turn to the inflow distributions of sons and daughters to tertiary education by social origin. We focus on tertiary degrees and show how they have changed in terms of educational family background across cohorts. These distributions reflect the interplay of changes in the structure of family origins at the macro level with changes in the origin-specific opportunities to obtain a tertiary degree at the micro level (see Equation 1). In Figure 6, we describe the cumulative conditional probabilities for sons and daughters to earn a tertiary degree by educational origin across cohorts.

Figure 6. Change in the inflow distributions of sons and daughters to tertiary education by social origin across cohorts. Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

In general, the developments for daughters (left panel of Figure 6) and sons (right panel of Figure 6) are very similar. However, the trend is more pronounced for daughters. It can be seen that the proportions of sons and daughters who stem from non-academic families decrease dramatically across cohorts. This is surprising, as the probability of a tertiary degree at the micro level has increased both for sons and daughters from this social origin group across cohorts (see Figures 4, 5). Yet this social origin group declines more strongly across cohorts, leading to an overall decline in its proportion of tertiary degree holders. In turn, the proportions of sons and daughters from academic families who complete tertiary degrees have risen dramatically across cohorts. In the most recent birth cohorts, about 50% of tertiary degree holders are sons and daughters from academic families. This increase is due both the upgrading in the social origin structure of sons and daughters and to the increasing likelihood of children from academic families to acquire a tertiary degree across cohorts. Thus, our empirical findings are in line with Hypothesis 1.

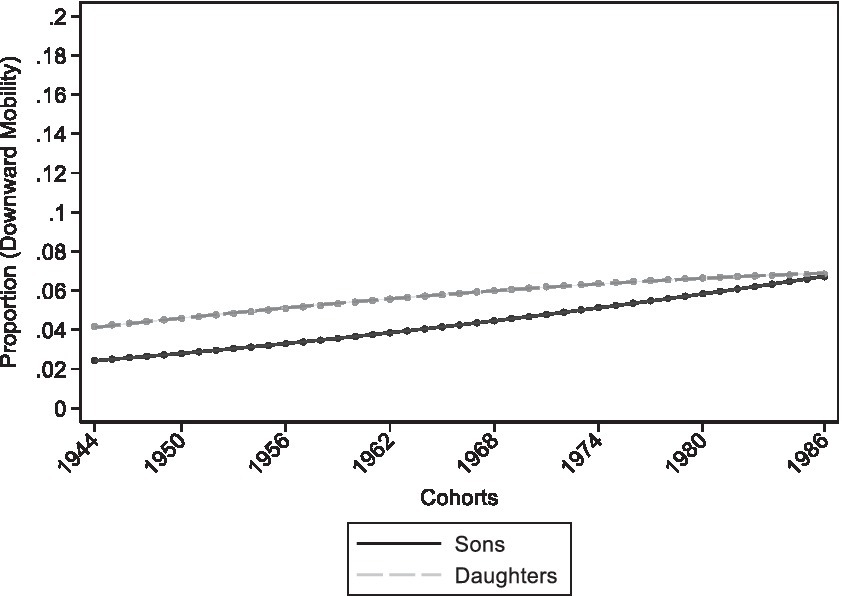

We now examine whether the proportions of downwardly mobile sons and daughters from academic families have changed differently across cohorts. The proportion of downwardly mobile sons and daughters is the product of the probability of stemming from an academic family and the probability of not earning a tertiary degree in each cohort (see Equation 5). Figure 7 shows a steady increase in the proportion of downwardly mobile sons and daughters from academic parents across cohorts. It has increased from 4% to 7% for daughters and from 2% to 7% for sons from the “1944 birth cohort” to the “1986 birth cohort.” In other words, the proportion of downwardly mobile daughters was already larger than for sons among the oldest birth cohorts. However, the change in the proportion of downwardly mobile sons over the observation period has been larger than for daughters, so that in the youngest birth cohorts the proportions of downwardly mobile daughters and sons have converged. Even though daughters and sons from academic families are less likely to be downwardly mobile at the micro level across cohorts (from 53% to 23% for daughters and from 32% to 23% for sons), the proportion of academic families has increased sharply at the macro level (from about 8% to about 30% for daughters and sons). The combination of both developments has led to an increasing share of daughters and sons from academic families being educationally downwardly mobile.

Figure 7. Change in the probability of daughters and sons from academic families to move educationally downwards. Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

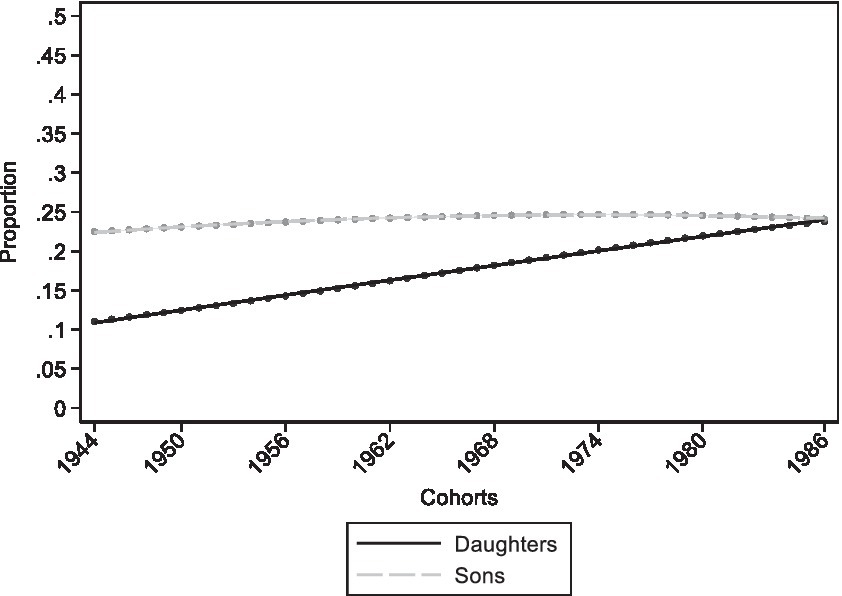

Finally, we investigate to which extent there are differences in the proportion of educationally upwardly mobile daughters and sons from non-academic families across cohorts. The proportions of upwardly mobile sons and daughters results from the product of the probability of stemming from a non-academic family and the probability of sons and daughters from non-academic families to earn a tertiary degree in each cohort (see Equation 6). Figure 8 shows that the proportion of upwardly mobile daughters from non-academic parents has increased from 11% to 24% across cohorts. Although this social origin group has declined across cohorts (from 92% to 70%) at the macro level, the opportunities of obtaining a tertiary degree have increased much more for daughters from this social origin group (from 12% to 34%) at the micro level, leading to an overall increase in the proportion of these upwardly mobile daughters.

Figure 8. Change in the probability of daughters and sons from non-academic parents to move educationally upwards. Data: SUF10.0.1 (Blossfeld et al., 2011; doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC6:10.0.1); author’s calculations.

Figure 8 also shows the proportions of upwardly mobile sons of non-academic parents. These proportions are quite stable across cohorts for sons (about 23%). The proportion of non-academic parents has declined at the macro level (from 92% to 71%). At the same time, however, the opportunities of sons from non-academic families to obtain a tertiary degree have increased slightly at the micro level. They have risen from 24% to 34%. These two opposing developments result in a persistent overall proportion of upwardly mobile sons.

In summary, we conclude that daughters from non-academic parents were able to catch up with sons in their upward mobility proportions. The faster change in the proportion of upwardly mobile daughters is the result of their increasing educational opportunities at the micro level.

The objective of this article has been to provide a systematic empirical assessment of how the rise of academic families across cohorts influences sons’ and daughters’ tertiary education in West Germany? So far there exists only one study by Ziefle (2017), which examines the consequences of these macro changes for women’s rising completion of higher education entrance certificates. In order to evaluate how the macro level upgrading of origin families across cohorts and the micro level developments of educational opportunities interact and lead to women’s catching-up process in tertiary educational attainment to men, we must examine the changing educational attainment process of both sons and daughters.

There are two macro- and micro-level developments in the educational expansion process that have influenced the rise in sons and daughters’ tertiary education attainment. First, there has been a dramatic improvement in the composition of the educational structure of families that has led to an overall increase in tertiary education attainment. However, this development has not been gender-specific. Both sons and daughters are much more likely to stem from academic families in the most recent birth cohorts. Second, educational opportunities for sons and daughters from all origin families have remained quite stable at the micro level during the period of massive expansion of tertiary education. Our findings suggest that academic families continue to preserve their advantageous educational positions for their progeny. Nevertheless, the demand for tertiary education has increased for sons and daughters from the two social origin groups, but it has increased particularly strongly for daughters. In sum, both sons and daughters alike have benefited from the general upgrading of family education across cohorts, but women have benefited even more from the expansion of the tertiary education system. With our empirical findings, we can thus confirm the earlier finding of Ziefle (2017) that the improvement in the social origin structure contributed to the increase in the educational attainment of daughters. However, at least for tertiary education, we do not find empirical evidence supporting her claim that daughters in particular could benefit from this compositional shift in parental resources (Ziefle, 2017).

Proponents of the gender-egalitarian perspective claim that women from academic families can increase their tertiary educational attainment across cohorts because these families have stronger gender-egalitarian attitudes. In addition, advocates of the mother role model perspective suggest that mothers are role models for their daughters. Thus, if mothers are more likely to obtain tertiary degrees across cohorts, their daughters should be more likely to obtain tertiary degrees as well. Similar to Buchmann and DiPrete (2006) for the United States, we find no evidence for these two claims in the German context. Neither of these two hypotheses can explain the massive increase of tertiary degrees earned by daughters relative to sons in Germany. First, the micro-level examination of origin-specific changes in the attainment of tertiary education shows that daughters from academic families already had lower probabilities to obtain a tertiary degree compared to sons among the oldest birth cohorts. This contrasts with the gender-egalitarian perspective. Second, if mothers serve as role models for their daughters, we would expect a significant interaction term between mother’s educational resources and being female. However, our micro-level model shows no such effect, so we must reject this hypothesis as well. Instead, we find support for micro-level theories that assert increasing benefits of tertiary education for all women, regardless of their social origin. In our micro-level model, daughters from all social origin groups increased their educational attainment at the same rate and caught up with their male counterparts. This is in line with previous research by Legewie and DiPrete (2009) and Becker (2014). A key contribution of this article, therefore, is that our more detailed model of educational growth allows us to better evaluate various macro- and micro level- hypotheses about women’s catch-up with men in tertiary education.

We showed that tertiary degree holders are very likely to stem from academic family backgrounds which have also increased across cohorts, so that today about half of the tertiary degree holders have an academic family background. Our empirical findings suggest that these patterns are quite similar for sons and daughters. A general conclusion of our findings is that a major driver of this compositional shift of tertiary degree holders is the changing composition of social origin across birth cohorts.

Furthermore, this article is one of the first studies that shows that changes in the distribution of social origin were crucial for changes in the proportion of educationally downwardly mobile sons and daughters from academic families. It could be demonstrated that the proportion of downwardly mobile sons and daughters has risen across cohorts as the pool of sons and daughters from academic families is rising. However, there are important gender differences in this development. Daughters had already a higher share of downward mobility than sons among the oldest birth cohorts. However, the change in the downward mobility proportion has been steeper for sons in our observation window, so that the proportions of downwardly mobile sons and daughters converged in the youngest birth cohorts.

We also examined gender-specific changes in the upward mobility proportions from non-academic families. We found that the proportions of upwardly mobile sons from non-academic families have been quite stable across birth cohorts. This stability is the result of countervailing trends: (1) The declines in non-academic families at the macro level and (2) the rising probabilities of earning a tertiary degree of these children at the micro level. One important finding was that the proportion of educationally upwardly mobile daughters from non-academic parents increased across cohorts, bringing their upward mobility shares closer to those of sons in the youngest birth cohorts.

In our analysis, we examined the long-term consequences of educational expansion by comparing the education of parents with the education of their sons and daughters. One limitation of this approach might be that we do not capture the process of educational expansion in its entirety. For example, at the macro level educational expansion is closely related to occupational structural change. As parents have improved their class position in a process of occupational upgrading across cohorts and skill requirements for jobs have increased across cohorts, they might demand higher education for their children to maintain their class position (Becker, 2007). Thus, one driver for increasing demand for education of families is occupational change. It would be good in future studies to operationalize educational expansion mechanisms using parental class position as well. However, since parental class comes biographically after parental education (Pfeffer, 2008) and, especially in the German labor market, qualifications are important to gain access to certain occupations, we should be able to capture this aspect of educational expansion with our measure of parental education as well. Finally, this descriptive study relies on a long-term cohort analysis over two generations that examined the two components of changes in educational growth, namely, changes in the macro composition of families that differ in their educational demands and changes in the educational opportunities of sons and daughters at the micro-level (Firebaugh, 1992). Further multigenerational research is needed in the future to better understand the mechanisms driving educational expansion, particularly how intergenerational upward mobility between two generations does or does not lead to improved educational opportunities for subsequent generations (e.g., Becker, 2007; Fuchs and Sixt, 2007a,b). Few studies to date have examined whether or not educational upward mobility from grandparents (G1) to parents (G2) leads to better educational opportunities for grandchildren (G 3). Some of the existing studies come to contradictory conclusions (e.g., Becker, 2007; Fuchs and Sixt, 2007a,b).

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.neps-data.de/Datenzentrum/Daten-und-Dokumentation/Datenangebot-NEPS.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This research has received publication funding support from the University of Innsbruck.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1154356/full#supplementary-material

1. ^This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort Adults, http://dx.doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC6:11.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data was collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network.

Becker, R. (2007). “Wie nachhaltig sind die Bildungsaufstiege wirklich? Eine Reanalyse der Studie von Fuchs und Sixt (2007) über die soziale Vererbung von Bildungserfolgen in der Generationenfolge”. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 59, 512–523. doi: 10.1007/s11577-007-0059-1

Becker, R. (2014). Reversal of gender differences in educational attainment: an historical analysis of the West German case. Educ. Res. 56, 184–201. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2014.898914

Becker, R., and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2017). Entry of men into the labor market in West Germany and their career mobility (1945–2008). J Labor Market Res 50, 113–130. doi: 10.1007/s11577-007-0059-1

Becker, R., and Müller, W. (2011). “Bildungsungleichheiten nach Geschlecht und Herkunft im Wandel” in Geschlechtsspezifische Bildungsungleichheiten, ed. A. Hadjar (Wiesbaden: Vs Verlag Für Sozialwissenschaften), 55–75.

Blossfeld, H.-P. (1993). “Changes in educational opportunities in the Federal Republic of Germany. A longitudinal study of cohorts born between 1916 and 1965” in Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries, eds. Y. Shavit and H.-P. Blossfeld (Boulder: Westview Press), 51–74.

Blossfeld, P. N. (2019). A multidimensional measure of social origin: theoretical perspectives, operationalization and empirical application in the field of educational inequality research. Qual. Quant. 53, 1347–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11135-018-0818-2

Blossfeld, P. N. (2020). The role of the changing social background composition for changes in inequality of educational opportunity: an analysis of the process of educational expansion in Germany 1950–2010. Adv. Life Course Res. 44:100338. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100338

Blossfeld, P. N. (2022). How do macro- and micro-level changes interact in the emergence of educational outcomes? Sociol. Compass 7:E13042. doi: 10.1111/soc4.13042

Blossfeld, P. N., Blossfeld, G. J., and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2017). “The speed of educational expansion and changes in inequality of educational opportunity.” In Bildungsgerechtigkeit, eds. T. Eckert and B. Gniewosz (Wiesbaden: Springer), 77–92.

Blossfeld, H.-P., and Drobnic, S. (2001). Careers of couples in contemporary society: From male breadwinner to dual-earner families. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blossfeld, H.-P., and Roßbach, H.-G. (2019). Education as a lifelong process. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Blossfeld, H.-P., Roßbach, H.-G., and Von Maurice, J. (2011). “The German National Educational Panel Study (Neps)” in Education as a lifelong process. The German National Educational Panel Study. eds. H.-P. Blossfeld, H.-G. Roßbach, and J. van Maurice Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Blossfeld, H.-P., and Timm, A. (2003). Who marries whom? Educational systems as marriage markets in modern societies. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity, and social inequality: Changing prospects in Western society. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). “Kulturelle Reproduktion und soziale Reproduktion” in Grundlagen einer Theorie der symbolischen Gewalt, ed. P. Bourdieu (Frankfurt A. M: Suhrkamp), 88–137.

Breen, R., and Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: towards a formal rational action theory. Ration. Soc. 9, 275–305. doi: 10.1177/104346397009003002

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Müller, W., and Pollak, R. (2009). Non-persistent inequality in educational attainment: evidence from eight European countries. Am. J. Sociol. 114, 1475–1521. doi: 10.1086/595951

Buchmann, C., and DiPrete, T. A. (2006). The growing female advantage in college completion: the role of family background and academic achievement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 71, 515–541. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100401

Buchmann, C., Diprete, T. A., and McDaniel, A. (2008). Gender inequalities in education. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 34:319–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134719

Bukodi, E., and Goldthorpe, J. H. (2013). Decomposing ‘social origins’: the effects of parents class, status, and education on the educational attainment of their children. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 29, 1024–1039. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcs079

Bukodi, E., Paskov, M., and Nolan, B. (2020). Intergenerational class mobility in Europe: a new account. Soc. Forces 98:941–972. doi: 10.1093/sf/soz026

Busch, A. (2013). Die berufliche Geschlechtersegregation in Deutschland: Ursachen, Reproduktion, Folgen. Wiesbaden: Springer Verlag.

Diekmann, A. (1982). Komponenten der Bildungsexpansion: Strukturelle Effekte, Bildungsbeteiligung und Jahrgangseffekte. Angewandte Sozialforschung Anc Aias Informationen Wien 10, 361–372.

DiPrete, T., and Buchmann, C. (2013). The rise of women: The growing gender gap in education and what it means for American schools. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Erikson, R. (1984). Social class of men, women and families. Sociology 18, 500–514. doi: 10.1177/0038038584018004003

Firebaugh, G. (1992). Where does social change come from? Estimating the relative contributions of individual change and population turnover. Popul Res Policy Res 11, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00136392

Fuchs, M., and Sixt, M. (2007a). Zur Nachhaltigkeit von Bildungsaufstiegen. Soziale Vererbung von Bildungserfolgen über mehrere Generationen. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 59, 1–29. doi: 10.1007/s11577-007-0001-6

Fuchs, M., and Sixt, M. (2007b). Replik auf den Diskussionsbeitrag von Rolf Becker. Bildungsmobilität über drei Generationen. Was genau bewirken Bildungsaufstiege für die Kinder der Aufsteiger. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 59, 524–535. doi: 10.1007/s11577-007-0060-8

Gallie, D. (2019). Research on work values in a changing economic and social context. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 682, 26–42. doi: 10.1177/0002716219826038

Goldthorpe, J. H. (2016). Social class mobility in modern Britain: changing structure, constant process. J Br Acad 4, 89–111. doi: 10.5871/jba/004.089

Hadjar, A. (2019). “Educational expansion and inequalities: how did inequalities by social origin and gender decrease in modern industrial societies?” in Research handbook on the sociology of education, ed. R. Becker (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 173–192.

Haupt, A. (2019). The long road to economic independence of German women, 1973 to 2011. Socius 5:2378023118818740. doi: 10.1177/2378023118818740

Helbig, M. (2012). Warum bekommen Jungen schlechter Schulnoten als Mädchen? Ein Sozialpsychologischer Erklärungsansatz. Z. Bild. 2, 41–54. doi: 10.1007/s35834-012-0026-4

Helbig, M. (2013). Geschlechtsspezifischer Bildungserfolg im Wandel. Eine Studie zum Schulverlauf von Mädchen und Jungen an allgemeinbildenden Schulen für die Geburtsjahrgänge 1944-1986 in Deutschland. J. Educ. Res. Online 5, 141–183. doi: 10.25656/01:8023

Helbig, M., and Sendzik, N. (2022). What drives regional disparities in educational expansion: school reform, modernization, or social structure? Educ. Sci. 12:175. doi: 10.3390/educsci12030175

Jackson, M. (2013). Determined to succeed? Performance versus choice in educational attainment. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Klesment, M., and Van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversal of the gender gap in education, motherhood, and women as main earners in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 44, 465–481. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcw063

Knight, C. R., and Brinton, M. C. (2017). One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. Am. J. Sociol. 122:1485–1532. doi: 10.1086/689814

Köhler, H. (1992). Bildungsbeteiligung und Sozialstruktur in der Bundesrepublik: Zu Stabilität und Wandel der Ungleichheit von Bildungschancen. Max-Planck-Institute für Bildungsforschung.

Korupp, S. E., Ganzeboom, H. B., and Van Der Lippe, T. (2002). Do mothers matter? A comparison of models of the influence of mothers' and fathers' educational and occupational status on children's educational attainment. Qual. Quant. 36:17–42. doi: 10.1023/A:1014393223522

Legewie, J., and Diprete, T. A. (2009). Family determinants of the changing gender gap in educational attainment: a comparison of the US and Germany. Schmollers Jahr. 129, 169–180. doi: 10.3790/schm.129.2.169

Lenski, G. E. (1966). Power and privilege: A theory of social stratification. New York: University Of Carolina Press.

Mare, R. D. (1979). Social background composition and educational growth. Demography 16, 55–71. doi: 10.2307/2061079

Mare, R. D. (2016). Educational homogamy in two gilded ages: evidence from inter-generational social mobility data. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 663, 117–139. doi: 10.1177/0002716215596967

Mare, R. D., and Maralani, V. (2006). The intergenerational effects of changes in women's educational attainments. Am. Sociol. Rev. 71:542–564. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100402

Marks, G. N. (2008). Are father’s or mother’s socioeconomic characteristics more important influences on student performance? Recent international evidence. Soc. Indic. Res. 85, 293–309. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9132-4

Mayer, K. U., Müller, W., and Pollak, R. (2007). “Germany: institutional change and inequalities of access in higher education” in Stratification in higher education: A comparative study, eds. Y. Shavit, R. Arum, A. Gamoran, and G. Menahem (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press Stanford), 241–265.

McDaniel, A. (2012). Women’s advantage in higher education: towards understanding a global phenomenon. Sociol. Compass 6, 581–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2012.00477.x

Pfeffer, F. T. (2008). Persistent inequality in educational attainment and its institutional context. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 24, 543–565. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcn026

Pollak, R., and Müller, W. (2020). “Education as an equalizing force: how declining educational inequality and educational expansion have contributed to more social fluidity in Germany?” in Education and intergenerational social mobility in Europe and the United States, eds. R. Breen and W. Mueller, (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press), 122–149.

Rosen, B. C., and Aneshensel, C. S. (1978). Sex differences in the educational-occupational expectation process. Soc. Forces 57:164–186. doi: 10.2307/2577632

Treiman, D. J. (1970). Industrialization and social stratification. Sociol. Inq. 40, 207–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1970.tb01009.x

Winsborough, H. H., and Sweet, J. A. (1976). Life cycles, educational attainment, and labor markets Eric.

Witte, N. (2020). Have changes in gender segregation and occupational closure contributed to increasing wage inequality in Germany, 1992–2012? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 36, 236–249. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcz055

Zagel, H., and Breen, R. (2019). Family demography and income inequality in West Germany and the United States. Acta Sociologica 62, 174–192. doi: 10.1177/0001699318759404

Keywords: NEPS, intercohort compositional change of social origin, gender inequalities, West Germany, educational inequality

Citation: Blossfeld PN (2023) How the rise of academic families across cohorts influences sons’ and daughters’ tertiary education in West Germany? Front. Educ. 8:1154356. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1154356

Received: 30 January 2023; Accepted: 20 March 2023;

Published: 17 May 2023.

Edited by:

Ehsan Elahi, Shandong University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Rolf Becker, University of Bern, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2023 Blossfeld. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pia Nicoletta Blossfeld, cGlhLmJsb3NzZmVsZEB1aWJrLmFjLmF0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.