- University of Missouri – Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, United States

This article discusses the findings of a narrative inquiry case study into the school experiences of adoptive and/or foster parents with children with Reactive Attachment Disorder. The data from families of children with an attachment disorder were collected through interviews and support group observations. The major finding of this study is that the caregivers of students with this attachment disorder feel as though they have been silenced by schools. The data highlights how the social, emotional, and academic needs of children with attachment disorders might not align with the components of educational accountability that are currently in place. Considerations are also raised about how educational accountability for students with special needs might need to be re-imagined in accordance with the perspectives and experiences of parents on school landscapes.

1 Introduction

Students who do not perform well academically or those whose needs are not standardized might run the risk of becoming marginalized in school (Clandinin et al., 2006). It is thus of critical significance to attend to the situations of students with special attachment needs, who might be pushed to the educational margins. Their experiences might be imperative for understanding new paths for accountability. In particular, students with Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and their parents may experience voicelessness and/or marginalization among school communities (Taft et al., 2015).

RAD has been defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) as an attachment disorder that presents with a pattern of behaviors, moods, and relationships that are inappropriate. RAD occurs when a child does not attach to a primary caregiver. It is indicated by interrelationship behaviors that are supported by Bowlby’s attachment theory (Barth et al., 2005). RAD has been diagnosed in the context of maltreatment (abuse/neglect) (Vasquez and Stensland, 2016), and especially among those who have spent time in institutional care (Miller et al., 2009). Common responses to students with RAD include placements in groups with students with emotional and behavioral disorders or removal of students to institutions for mental wellness. Yet, children with RAD are not responsive to the strategies that are deemed to be effective for those with emotional and behavioral disorders (Cain, 2006).

Attachment disorder has traditionally been considered to be extremely rare. According to Chaffin et al. (2006), exact prevalence figures on RAD are unavailable. Skovgaard (2010) estimated the prevalence to be 0.9% in 1.5 years olds. Yet, Minnis et al. (2013) argued that prevalence beyond infancy is unknown because until recently no appropriate measures were available to determine prevalence of this population. They found in their study of 1,646 children in a deprived population that there was a prevalence estimation of 1.4% definite cases of RAD. When suspected borderline cases were included, the estimate was that 2.3% of students in a deprived population had RAD.

Minnis et al. (2013) highlighted that children with RAD will continue to have a range of disabling difficulties throughout childhood, even when they are supported by foster or adoptive families, thereby making it vital to identify them and provide services for them early on. Del Duca (2013) supported the need for enhanced diagnosis and support of students with RAD in the following statement that is based upon her practices:

Over the last few years, I have become aware of an increase in the number of referrals to assess children diagnosed with Reactive Attachment Disorder. Whether this is a coincidence or an indication of statistical increase in incidence of RAD, I cannot say. What I can tell you is how clinically interesting and extremely frustrating these cases can be Del Duca (2013), n. p.

Zeanah et al. (2004) indicated the RAD prevalence rate to be 38–40% among 94 maltreated toddlers in foster care who were less than 48 months old. Further, in an analysis of 20 sibling pairs, Zeanah et al. (2004) found a high percentage of siblings had RAD (75%). They thus concluded RAD to be of high relevance among the group of maltreated children.

Students with RAD may think in destructive ways or think in a manner termed disrupted cognition (Yell et al., 2009). These students tend to sabotage relationships, and they do not trust adults or respect authority (Thomas, 2005; Cain, 2006; Taft et al., 2016). Even when students do well and are praised, they often feel as though they are put outside their comfort zone and they may react in inappropriate manners (Cain, 2006).

There is a need for contributions to the body of research on RAD due to the ongoing development of insight into this attachment disorder. For example, Zeanah et al. (2016) highlight how before 2005, RAD was understood as one comprehensive disorder. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) now outlines two different disorders that were formerly ascribed to RAD. Namely, children may now be diagnosed with RAD related to attachment issues and Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) related to social inhibition issues (Gleason et al., 2011) and Zeanah and Boris (2000) point to the persistence of DSED.

At the same time, Zeanah et al. (2016) argue that it is potentially controversial to provide a diagnosis of either RAD or DSED in older, school-aged children, since they may have developed other interpersonal challenges over time. It is perhaps for this reason that less research exists about older children with RAD. This study focuses on the experiences of family members of older, school-aged students with RAD. The children of our parent participants were diagnosed with RAD utilizing earlier guidance from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), which pre-dated the separation of RAD from DSED. Therefore, this study accounts for research on RAD that has been published before and after the re-classification of RAD and DSED. Given that the diagnosis of RAD among the children featured in our study, we also consider the experiences outlined below as potentially indicative of RAD and/or DSED.

This study may highlight possible gaps in theory or practice between older and newer classifications of RAD/DSED among school staff and family members. It may also shed light on the value of deliberating over the relationship between the newer classification of RAD/DSED and the family experiences of multiple diagnoses and problematic behaviors among children. This work is additionally important for underscoring how school resources for students, school staff, and families may need to be informed and updated on a continuous basis to ensure that student supports are aligned with the most current information about attachment disorders and other disorders more broadly.

There is further a pronounced paucity of research investigating the schooling and educational experiences of children with RAD and/or DSED in the schools. There is even less research, qualitative or quantitative, looking into the relationships between the families of children with RAD and/or DSED and the school systems which serve their children. A search of Google Scholar, ProQuest, and Psych Info databases displayed a large amount of research on attachment issues (e.g., Kennedy and Kennedy, 2004), but these studies were not specific to RAD and/or DSED. Attachment research concentrated on treatment and interventions for maltreated children, but they were not specific to RAD (e.g., Hanson and Spratt, 2000; Buckner et al., 2008). RAD research was focused on identification and prevalence of RAD (Zeanah et al., 2004; Minnis et al., 2013), psychological and social characteristics of this population (Hall and Geher, 2003; Chaffin et al., 2006), or effects of child abuse, maltreatment, and neglect on child development (O’Connor et al., 1999; Hildyard and Wolfe, 2002).

Literature searches found only six studies that directly addressed issues related to schools and children with RAD/DSED. Schwartz and Davis (2006) discussed the impact RAD has on school readiness for children who have suffered serious abuse. Shaw and Páez (2007) highlighted considerations for school social workers when dealing with children with RAD. Davis et al. (2006) examined psychopathology in schools, and RAD is mentioned as one of the most difficult attachment disorders. Three qualitative studies (Taft et al., 2015; Schlein et al., 2016; Taft et al., 2016) explored various aspects of the relationship between families with children with RAD and the schools and the crucial need for effective collaborations between teachers, school professionals, and the families of children with RAD. This study might therefore serve as a major contribution to the literature with both theoretical and practical applications.

We highlight below a story of schooling that is based upon personal and social goals. We argue for the need to incorporate the life goals of students and their families into the formal planned and enacted curricula. Significantly, we underline how students’ and their families’ educational aspirations that are inclusive of personal and social life goals might reveal divergent curricular expectations from schools in terms of preparation for possible higher education and/or life outside of schools. We further outline how it is significant for general education teachers and school leaders to examine how the parents of students with special needs story their experiences with schooling and how they outline their expectations and goals for schooling.

Such narratives might shed light on the potential for schools to become more accountable to all students. Moreover, students with RAD and/or DSED are underrepresented and under-recognized within the group of students who are identified as having special needs, and so their experiential narratives are especially important. Since the parents of students with RAD and/or DSED are the primary advocates for their children’s education, it is illuminating to hear how they voice their concerns regarding accountability in education and how they story the experiences that their children have in school.

2 Method

This study was conducted following the narrative inquiry research tradition of Clandinin and Connelly (2000). Narrative inquiry is a qualitative research method that examines experience as the phenomenon of interest (Clandinin, 2007). This form of investigation entails the collection of “stories of experience” as data (Connelly and Clandinin, 1991), which are analyzed for common narrative themes with interpretations regarding the social, personal, contextual, and temporal components of such themes. Our research question was: What are the experiences of parents and/or caregivers of children with reactive attachment disorder in home and school environments?

Ongoing research on the experiences of families of students with RADDSED may serve to update the knowledge of teachers, educational leaders, and other school staff regarding how students are discussed and supported. There is a dearth of literature in the fields of Curriculum and Instruction available on RAD dealing with schooling experiences (Taft et al., 2016). Even less research is available about the home-school bridging experiences of parents and caregivers of children with RAD (Taft et al., 2015).

RAD often occurs among children who have experienced maltreatment or neglect. It is therefore useful to connect generally with research on behavior challenges among maltreated and neglected children. For example, Bennett et al. (2005) examine behavior problems following maltreatment among children. The authors found a relationship between physical abuse, feelings of shame, and anger. Increases in anger were further connected to enhanced instances of teachers flagging children for behavior challenges. Lyons et al. (2020) indicate emotional regulation as a solid approach in relation to children who have undergone trauma. Their recommendations include calming the brainstem, repairing the attachment cycle, and developing connections between the child and the adult while recognizing that such steps may occur in a cyclical fashion. Vasquez and Miller (2017) further discuss emotional regulation in the form of rage and aggression among children with RAD. They underscore some of the facets of rage and aggression among children who have been diagnosed with RAD to add dimension to the literature given that aggression is not associated with RAD.

This research thus contributes to the literature on children with RAD who display symptoms such as rage and aggression that may coincide with identified RAD behaviors (Hall and Geher, 2003; Vasquez and Stensland, 2016). Children with RAD may further present other challenging behaviors that are not included in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2022), such as: “lack of conscience or empathy for others, manifesting in antisocial behavior; severe aggression that (at times) may appear deliberate on the part of the child; property destruction; pathological lying; stealing; removing and hiding food from the family’s kitchen or refrigerator; inappropriate sexual behavior; and manipulative behavior (Grcevich, 2016).” The parent participants for this study all reported these behaviors among their children who had been diagnosed with RAD prior to the diagnostic revision. Shedding light on some of the problematic behaviors that might be present among children diagnosed with RAD and/or DSED may enhance understanding of treatments aimed at supporting students in navigating schooling and classroom life. The specific focus of this work on the context of education is particularly critical, given the connection between behavior (Kremer et al., 2016) and/or peer and social behaviors (DeVries et al., 2018) with success in schooling.

2.1 Participants

The participants in this study represent an opportunistic purposeful sample (Creswell, 2012). The following requirements were used for participant selection. (1) Parent’s child had to be diagnosed with RAD and (2) parent’s child had to be currently enrolled in school or be of school age.

The children whose families were approached for participation in this study were diagnosed by healthcare professionals with RAD. The diagnoses were all made prior to the re-classification of RAD within the DSM-5 (2022). Therefore, we acknowledge the possibility that the children of our parent participants may have symptoms of both RAD and DSED, particularly because it is uncommon to find RAD on its own in children and DSED tends to persist (Zeanah et al., 2016). The children of our parent participants also all had Individualized Education Plans (IEP’s) that listed them as either Emotion Disorder, Other Health Impaired, or a similar Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004) category. RAD was not recognized as a disability under IDEA. The only way to get these students support in the educational system was to label them with a disability that was defined under IDEA. This points to a possible gap in supporting students with RAD in school and highlights the overall critical nature of this study exploring aspects of students with RAD and education.

Six participants were recruited from a RAD support group. One participant was known by one of the authors and inquiry participation was requested. Another participant approached one author after a conference presentation on attachment, emotional, and behavioral disorders. When she disclosed that her child had RAD, she was invited to participate in the planned study. Two additional parents were referred for study participation.

Our participants were from four different states and from nine different school districts, which resulted in contextual diversity within the participant pool. Their children attended rural, suburban, and urban schools. All the students attended public schools except for temporary attendance at psychiatric residential treatment centers or experiential treatment farms. One child received home schooling for much of his education, although he attended a public school during the period of the investigation.

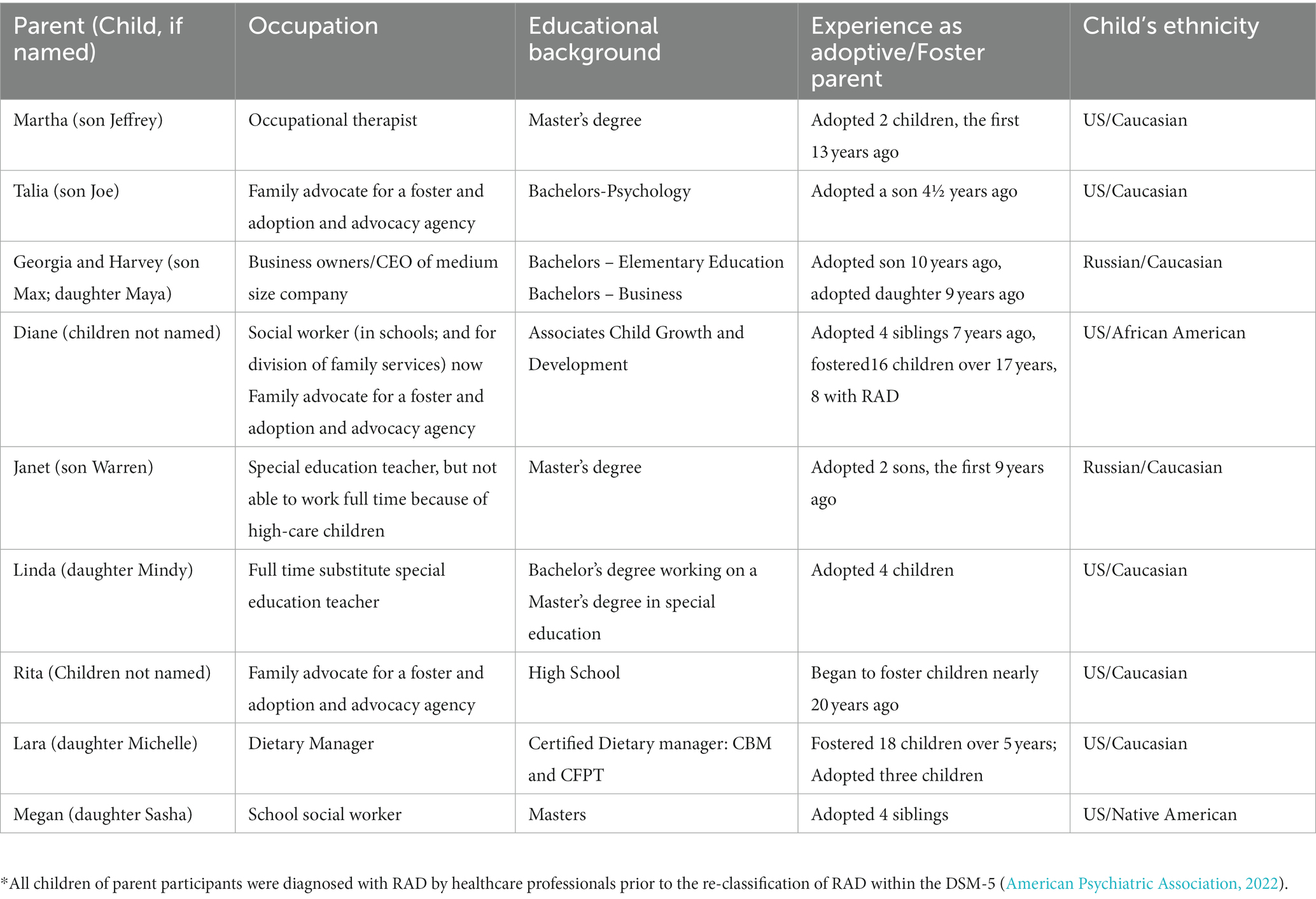

The parents who participated in the interviews were a very well-informed and well-educated group of individuals. Many of the participants worked in fields related to education or social services. The background information, such as the education, occupation, and experience with fostered or adopted children for each of the participants is reported in Table 1.

2.2 Data collection

We conducted one 90 min interview with each of our participants. The interviews comprised open-ended questions about the behaviors of their children, the academic and social experiences of their children in school, and the hopes and dreams of our parent participants for their children. The interviews were all tape-recorded and subsequently transcribed.

We also collected data through observations at a monthly support group meeting for families with children with RAD on three occasions. Field notes on our participants’ experiences were compiled. A group consent form was signed by all meeting participants for this purpose. Four participants were not members of the support group, and so they were not observed during support group meetings. The names of people and places were replaced with pseudonyms in field notes and interview transcriptions.

2.3 Data analysis

We each separately reviewed interview transcriptions and field notes to bring forward primary categories from among our narrative data. We initially conducted categorical content analysis of data on an individual basis. We shared the primary categories that we each uncovered among the data with each other and discussed how the categories may overlap or differ. We found that we did not have different categories. However, we had named the categories differently. Discussing these categories was a useful exercise to think deeply about our primary data analysis and to prepare an amalgamated list of primary thematic categories.

The next step of our data analysis included focusing on the amalgamated list of primary categories to uncover the themes that arose from the broader categories. In particular, we highlighted the data in different colors and created a key to explain the various themes that were represented by each color. Finally, we examined the highlighted data to search for common narrative themes across our participants. We made use of the three-dimensional narrative inquiry framework (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000) for data analysis. This provided us with a structure to tease apart the temporal, cultural, and interactional components within common narrative themes. This included taking into consideration when possible how the common narrative themes related to participants’ discrete life experiences.

3 Results

Children with RAD are often misdiagnosed, and their needs are complex, and sometimes misunderstood (Cain, 2006; Chaffin et al., 2006). Confusion regarding early diagnoses of RAD attributed to what is now understood as DSED is potentially problematic (Zeanah et al., 2016). Children with attachment disorders may also experience challenges with emotional regulation and exhibit behaviors such as rage (Vasquez and Miller, 2017). There is a need for more research to shed light on possible relationships between attachment and emotional regulation. Moreover, the diagnosis of RAD among older children and adolescents has been deemed to be controversial. In older children, other psychiatric disorders are often diagnosed over RAD. However, Seim et al. (2019) argue that RAD is indeed a valid diagnosis for older children and adults.

We discuss here the findings of a narrative investigation into the experiences of adoptive and/or foster families with children diagnosed with RAD prior to the diagnosis revision. We highlight through considering common themed findings how educational accountability for all students, including learners with special needs, might need to be re-imagined. We further consider how such stories might be useful for improving curricular interactions among students, their family members, and educational professionals.

3.1 Academic success and anxiety

Education in the United States has become test-centric (Musoleno and White, 2010). While some students might have heightened anxiety due to test-taking experiences, students with RAD might have an increased level of anxiety in school settings that might make all structured school activities difficult (Schwartz and Davis, 2006). One parent participant, Martha, discussed with us how her son, Jeffrey, deals with anxiety. “His level of anxiety is so high. He worries about everything. And that’s what RAD is. RAD will do that.” In Martha’s narrative, she highlighted how because of RAD, her son sees all situations as stressful and he worries about everything. Martha depicts anxiety as intrinsic to RAD. At the same time, anxiety among children with RAD may be caused by issues pertaining to RAD and also those that do not. Martha’s story about anxiety was common among our participants, and so it is useful for teachers and school staff to understand that when dealing with children with RAD, it might prove to be useful to work to figure out how best to work to reduce a student’s anxiety before teaching and learning can occur.

Additionally, all of our participants indicated to us that once their children with RAD encountered a lack of success in one learning activity, anxiety can often become generalized to all school-related situations, especially those connected with assessment. They explained how their children often perceive that a teacher is treating her or him unfairly following an occasion where the student with RAD publicly presented an incorrect answer in class. Our parent participants offered that this feeling of increased anxiety might precipitate a serious behavior event. Alternatively, we were told about how students with RAD might also feel like he or she is being made to look less intelligent in front of peers on purpose when provided answers are wrong. This was seemingly a common stressor for students with RAD in situations both inside and outside of the classroom.

For example, Georgia informed us that her son, Max, had refused to participate in tennis lessons after school since he did not think he would be very good at it. She claimed that the fear of being uncovered as someone who needs to learn things or as someone who might make mistakes is unbearable for her son. Our participants stressed to us that it is imperative for teachers to shape lessons in ways that could lessen such anxiety in students with RAD so that they may participate in their schooling.

3.2 Barriers to social success

Our findings brought to light how students with RAD (and/or DSED) may experience difficulties in developing social relations with peers. Social interaction is a significant aspect of schooling that is connected to some learning activities. Social success is also crucial for students’ emotional well-being and to their training for future societal participation. In the next narrative, Linda related some of the social barriers that her daughter Mindy faces in school.

I’ve talked to her teacher thoroughly, and yeah, she has been doing this to other students at school. She’s got one friend at school. Or she had one friend. The teachers say that they feel that the kids say she made friends when she first came here, but then when she gets a different class, because there are so many students they switch children around, she’ll make friends automatically. But Mindy’s nice to play with at first. But then sometimes Mindy’s not very nice. She wants to be first all the time and she wants to be the biggest and the best.

Linda discussed how her child, Mindy, readily befriends students, yet her behavior usually gets in the way of sustaining relationships with any of her peers. It is possible that RAD-related stressors may inhibit the formation of lasting friendships with peers. Linda highlighted how students with RAD may have excessive levels of anxiety, which can be escalated when the students are made to feel as though they are subject to potential ridicule. This same behavior might be paralleled in interactions with peers, where students with RAD may sense judgment against them if they are not the best at any social or school-related peer activity. Our participants all related to us how their children with RAD often display an attitude of being smarter than others, and they react explosively if that image is changed. For this reason, friendships might dissolve over time and peer learning activities might prove to be difficult to manage without behavior interruptions. For example, in the following, Talia explained difficulties that her son, Joe, has experienced both inside and outside of schools:

Researcher: How is he with other kids?

Talia: He’s about the same as he would be with an adult. Very young-minded when it comes to someone takes my stuff, he just automatically will hit, kick, bite, spit, versus using the verbal and asking for it. It’s just very reactive.

Talia pointed out that her son responds to peers in a manner that would be considered immature for a 12 years-old boy. Instead of discussing issues with peers, negative behaviors might immediately take over. Janet reinforced how children with RAD might not easily make friends in the following statement about her son Warren: “He wants to make friends, read better, and live at home full-time. He is in need of a group-home setting for now, which we are working on putting into place. He is likeable, but can be unpredictable with his behaviors.” Diane further highlighted in the next story some of the complicated responses that children with RAD might have with respect to interacting with others:

Compliments for them are very difficult because most of the stuff they do is disingenuous. So if you are going to compliment that, “I cannot let you say good things about me, because I’m not a good person so now I have to do something. Now you have made me do something to you to show you I’m not that kid.” So when they do a good job, and you do not specifically say, “Oh Johnny, you did such a great job,” you can say, “Man, this is really clean. Whoever did that did a great job.” And you are gone. You’re off that. It’s over with. You’ve complimented what they did without making them have to say, “She said I was a good person.” And I’m very specific about what I comment on. I’m not going to tell you, “Oh, you did a great job. Hey, that looks really good,” or “That looks really clean.”

Diane’s discussion of her son’s behaviors exhibits some of the complex levels of understanding that might be needed to engage successfully with children with RAD. Such complicated responses to behaviors might make the development of friendships, as well as all school interactions challenging.

3.3 Constructing school as a safe space

Our participants additionally disclosed that their children did not see their schools as stable and safe spaces. While all of our participants’ narratives displayed how social interactions might often be complicated in schools for students with RAD, many of our participants expressed to us how they were also not made to feel welcome within their children’s respective school communities. The following story shows how parents of children with RAD might need to look beyond school walls for ways to build their children’s skills and for the socialization of their children. “We were not involved with many things involving the school at all. There are extracurricular activities that I did not feel comfortable with him doing it. It did not feel like we were respected there. So I looked outside.” Talia related in the above how she signed her son, Joe, up for extracurricular activities outside of the school instead of taking advantage of after-school programs at the school. It would have been more convenient for Joe to attend programs at his school. This would have further enabled Joe to have additional opportunities to build friendships with his fellow peers. However, such programs did not feel like inclusive environments for them. Diane explained why she decided to send her child to an alternative school due to concerns about safety.

I think that inclusion is important. Very important for our kids. Because they have already seen a warped view of the world, so we need to get them into things that are, that look the way they are going to look when they walk out into the world. So it’s very important that they have those opportunities, but it’s also very important that everyone is safe. The two that I have in the alternative school right now are exactly where they need to be. Specifically the 7 yrs-old, because he would not be safe in a regular school setting. He is not very safe in the alternative school setting. And we are just are, work where we are until they decide to do something different with him.

Diane related how safety for her child helped her to select a school for her child. This notion of safety was repeated by all of our participants. Marcie shed light in the following about how students with RAD might themselves perceive schools to be an unsafe environment.

I do not feel like he ever felt safe at a school. That happened pretty, I want to say pretty early in the year. And he just never, he never felt safe. The things he did, you know, were showing that he never felt safe. Constantly hiding under the teacher’s desk. Under tables. And they saw that as behavioral. Not as him trying to flee from whatever it was that was worrying him.

Relatedly, some of our participants pointed out how they felt that they were blamed and shamed by the school due to the behavior of their children with RAD or that their children felt as though they were being blamed for their attachment disorder. Rather than separating RAD behaviors from the children and their character traits, parents believed that the schools seemingly judged the parents negatively for not properly instilling manners and behavioral control in their children. Janet stated that she felt the school was at fault for “communicating in ways that sounded as though parents were to blame for problems our son had.”

3.4 Learning placements and academic support

Lara explained in the following how in her experience with her daughter, she encountered a narrative that showcased a potential mismatch between her goals for her child and the learning placements made by schools, a general lack of school-based academic support, and a push for residential treatment by school staff.

Researcher: Would you like to see her possibly included in the regular general education classrooms with her peers?

Lara: Yes. Absolutely. I would love for her to be able to be a part of that. That’s what I was trying to tell her in the last month or so when she was really, when her behavior was really bad at the residential treatment center. I was thinking, “You know, you are missing out on so much. You’re missing out on the real true high school fun. Because there is fun in high school.” You know, that’s what I was thinking, because she likes to take pictures and she’s really good at it. And I said, “You have an eye for taking pictures. Not everybody has that eye, that kind of talent. You could be on the yearbook committee and taking pictures for the yearbook and something like that.”

In the narrative above, Lara conveyed her sense that repeated shifts on the school landscape, between classrooms, as well as through stints at a residential treatment center, inhibited her daughter’s ability to socialize at school. Such shifts further seemed to lessen her potential to gain a sense of joy in some of the many learning and growth opportunities that might be affiliated with school life. As well, in the previous sub-section, we related how Mindy had envisioned one of the barriers to social success as the numerous changes in environment that her child experienced in school. She discussed how her child experienced much anxiety, and she was particularly unable to maintain social relationships with her peers when she was not on a welcoming and constant landscape. Our parent participants further reinforced to us that their children with RAD usually exhibited better behaviors when they were in environments that they could control, and with which they were familiar. At the same time, Megan related in the next narrative how her daughter, Sasha, faced a different experience in terms of school placements and academic support.

They are not on IEPs and I … and part of that is because they are smart, and I cannot figure out how to help them in the academic world. I just cannot. I knew from the beginning that they needed extra support, and, like, Sasha has a huge anxiety about school and just peers in general, and I would go in and say, “Okay, we have to get something in place for her. She cannot function in a regular classroom setting.” And I just kept getting, “Well her grades look okay. Her test scores look okay. She looks fine. There really is not anything we can do.” And that’s so frustrating to me, because I’m a school social worker and I know these people, and I still could not get help. I could never get, I still do not have anything in place for any of my kids.

Although Megan’s daughter displayed difficult behaviors in the home environment, these were not as noticeable when her daughter was at school. Moreover, Sasha is able to attend to her lessons, and she performs well on tests. Megan, who is a social worker at the school, suspected that this is why she was unable to get an Independent Education Plan (IEP) in place for her daughter. Megan knew that her daughter could benefit greatly from being given additional resources, so that she could learn tools to function well in society following school graduation.

If Sasha had an IEP, the school would also be required to continue to deliver an appropriate level of instruction while she was at an alternative setting. Without an IEP, the school could not be held responsible for the cost of Megan’s residential placement. Megan told us that her daughter was eventually sent to a residential treatment center, and upon her return to her regular school, she was still denied an IEP. She further emphasized that a state counselor handled her daughter’s case, and his perspective was seemingly related to cost minimization. She was told by this counselor that “his job he told me and my husband, is to keep her out of residential because it costs the state over $1,000 a day to have her there.” Megan believed that cost to the school guided decisions regarding developing an IEP for her daughter. Previous work on RAD (Trout and Thomas, 2005) has documented avoidance of costs and regulations associated with an IEP. However, without speaking with school staff, we are unable to confirm whether Megan’s perspective on the matter was a clear depiction of the factors surrounding the lack of an IEP for Sasha.

In turn, Harvey and Georgia claimed that they faced difficulty in getting resources for both of their children with RAD. They discussed below how they believed that their attempts to put pressure on the school were needed so that they could get necessary services to their children.

Harvey: Oh no, they did not help us. We had to figure it out on our own. It was so frustrating and finally, my friend who was the administrator, out of frustration I just said, “I’m going to sue the school district. We’re going to do something.” Their friend was also a special education consultant and guided them through the process of obtaining an Other Health Impaired label for their son and daughter, both diagnosed with RAD.

Megan related the next story as the school’s response to her child:

“She looks fine, there really is not anything we can do,” and that’s so frustrating to me because I’m a school social worker and I know these people and I still could not get help. I could never get, I still do not have anything in place for any of my kids.

Similar stories were conveyed to us by all of our participants. Our participants discussed how their children’s schools were often seemingly reluctant to provide services for their children with RAD, even though many of these children often exhibited pronounced problems at school. While the children could receive services under the Other Health Impaired category or with a 504 plan, our parent participants felt as though they needed to push schools to offer services to their children. This is an important factor to consider regarding this group of participants given the fact that the children of seven of the families were temporarily placed in residential psychiatric treatment centers. Two of the children were also eventually placed in experiential “ranch” treatment placements for children with RAD.

3.5 Teacher accountability

Our parent participants informed us during interviews that they did not believe that their children’s teachers were in fact accountable to the academic, emotional, and social needs of their children. Primarily, they complained of teachers’ lack of knowledge about RAD and how to relate to children with that disorder. In the story below, Lara explained her perspective that teachers’ responses to her daughter, Michelle, might sometimes exacerbate her daughter’s behaviors.

Lara: I just think that if they understand what they are dealing with better that she’d still be able, she’d be able to do it. Because I think if the teachers are understanding, they’d have the heightened sense of what could happen, and they’d keep their eye on that. And, you know, if she’s out of control, start even just a little bit out of control, then they can nip it in the bud. You know what I mean?… I do not think they know enough about RAD.

Lara explained to us that it would be ideal if teachers understood how to interact with her daughter. She told us how when Michelle begins to misbehave, it is useful to take control of the situation immediately. Instead, Lara finds that Michelle’s teacher allows Michelle’s behaviors to escalate to the point where she needs to be removed from class. That response then causes Michelle to miss out on lessons and interactions with peers. Failure by school professionals to understand students with RAD and possible inadequate training might lead to negative outcomes for these students. Janet explored in the following her many concerns regarding teacher accountability toward her son, Warren.

I was concerned school staff would not understand my son’s issues related to a RAD diagnosis. I was concerned we would be misinterpreted as parents by school staff. Parenting a child with RAD is a difficult and complex experience not adequately understood by the general public, including school staff. I was concerned our son would make false allegations of abuse or neglect about us as parents, since this frequently happened to other families of children with RAD. I was concerned when schools would not use our son’s home behaviors as indicators of problems at school. I was concerned because our son did not exhibit many of his aggressive behaviors outside of the home when he was younger, which made it difficult to understand how to communicate with school staff about his high needs and high-risk behaviors. I was concerned our son would split school staff against us as parents, making it more difficult to advocate for his education and special needs.

I am now concerned that our son will fail to access an appropriate education because his disability is complex, and he has experienced excessive transitions to access mental health treatment. Since many treatment settings were outside his school district, he has experienced many school transitions. I am concerned that school staff do not understand as clearly as my husband and I do that our son’s trajectory looks bleak given complicated mental health conditions, which include RAD. Incarceration, homelessness, or early death are very real possibilities for our son’s future. I remain concerned that schools will talk past us as parents and not work transparently with us in trying to reduce the number of transitions our son must go through to access treatment and still receive an appropriate education.

Janet’s story underscores some of the great effects that a teacher’s knowledge, experience, and support might have for her son, Warren. She perceived that her son’s teachers had a possible lack of understanding about Warren’s condition. Janet further blamed the related transitions that he has experienced within schools and across schools and treatment centers as a rationale for his possible downward spiral, and she shared concerns with us about an ongoing negative future trajectory for her son. In turn, Janet underlined the need to develop strong bonds of trust between parents and teachers so that children with RAD will not attempt to triangulate people as a form of manipulation. Sabotage is one area that has been associated with RAD/DSED, but there are also other areas that are associated with peer problems with varied reasons. Children with RAD have been noted to triangulate adults one against the other, school professionals against each other, school professionals against parents, or even parent against parent (Thomas, 2005; Trout and Thomas, 2005; Cain, 2006; Taft et al., 2015). Peer problems are more widely seen as an issue among children with RAD/DSED, such as discussed above with Bennett et al.’s (2005) reporting regarding anger among children who had suffered physical abuse. Guyon-Harris et al. (2019) conducted a study of social functioning among children who had spent time in an institutional living setting. They indicate poor social functioning among children diagnosed with RAD/DSED who live in institutions. Socialization issues among peers were also found in a study of children in Finland who were adopted internationally (Raaska et al., 2012). The authors found that internationally adopted children with RAD experienced instances of peer victimization and the undertaking of bullying behaviors against peers.

3.6 Educational aims and future goals

Education professionals and school leaders have goals for students that might be linked with academic achievement, the successful completion of college education, and overall contributions to society. Nevertheless, parents might have different goals for their children that relate to notions of fulfillment and happiness. In the following, Georgia and Harvey relate their hope for their children with RAD.

Georgia: I want them to be happy. Happy as can be and function in this world.

Harvey: Productive adults.

Georgia: Maya with her horse. She loves horses. I can picture her, you know, working at a stable maybe. Doing whatever needs to be done.

Harvey: Helping a vet.

Georgia: Yeah, helping a vet out. Our dog goes to a play group. I can picture Maya being the one that corrals the dogs and cleans up as needed. Neither one have got the capability to go far academically.

Georgia and Harvey expressed their desire that their children with RAD lead lives as productive adults. They also see a career dealing with animals for their daughter, Maya. Next, Talia described her hopes for her son, Joe.

At this point, my goal for our son is that he do the best he can, 1 day at a time. And work together with us as his family to meet each day with courage, hope, honesty, and a good sense of humor. Our goal is to use the principles of self-determination, person-centered planning, and family-focused outcomes to keep our son in the driver’s seat of his education and life while helping him understand and support the function my husband and I fulfill as his parents. He has a difficult time acknowledging and adhering to the functions of relationships that are much needed in his life. He simply does not understand this. Our goal is that he is able to live a contributive life for himself and others as he gets older. He’s 12 now. And be able to fulfill some of his own goals as an adolescent and eventually adult. Given his disabilities, the odds are stacked against him. But we hold onto hope and do the best we can to stand alongside of him 1 day at a time.

Talia’s words might serve to remind educators that sometimes accountability might be best measured in terms of student growth rather than via formal assessment scores. Her narrative showed how not every students’ goals might be interconnected with academic careers. Despite this fact, many students can have happy and successful lives if they are equipped with the tools for realizing their goals.

Throughout this discussion of the research findings, we related the common narrative themes found among our data. As a narrative inquiry, we isolated themes that were present for all of our participants for in-depth discussion. We shed light on our participants’ experiences of interacting with their children’s schools concerning their children with RAD.

We considered how students with RAD display a heightened sense of anxiety, and that this might be of much relevance when considering testing in school or a focus on grading. We examined the ways in which our participants’ children showcased anxiety and explained how this anxiety can be related to both negative and positive comments directed toward children with RAD. For this reason, we noted how our participants’ children not only experienced limited academic encounters due to high levels of anxiety. They also faced difficulties making friends and sustaining friendships or peer work groups. Anxiety and fear of failure or fear of embarrassment seemingly strained such school and classroom-based encounters.

In addition, we related how notions of safety were considered to be highly important for our participants. They presented worries that their children with RAD might not feel safe in large public classrooms. Moreover, they indicated that negative classroom experiences regarding punishments or judgments for inappropriate behaviors might cause their children to respond to school with a sense of fear and insecurity.

We further outlined how learning resources were often limited for the children of our participants. IEPs and Other Health Impairment labels were seemingly only provided when parents learned how to advocate for their children. It might be the case that other children with RAD might not receive the assistance that they require. It is significant to note that all of our participants were well-educated and familiar with the schooling system. Many of them were trained and/or worked in educational or social service-related professions, and they had friends and other connections in their children’s schools. As such, they were in strong positions to advocate for their children. However, their experiences showcased how they were still met with obstacles. This is a pertinent finding for our study, because not every student with RAD will be able to benefit from family members who might have a sophisticated understanding of the schooling system. Teachers, educational professionals, and school administrators might become more accountable to some of their most vulnerable students by actively engaging in partnerships with parents throughout any decisions regarding student assistance and the allocation of resources.

The final theme of this study concerned the future goals of our participants for their children. Their stories testify to the multiple ways in which students might strive to be successful, which include and supersede test scores and other numerical academic accounting. This holistic vision for educational aims and accountability might be of much value for all educators to consider.

4 Discussion

Our participants’ stories of experiences highlighted above displayed how students with RAD and their families might feel as though they are silenced on school landscapes of educational accountability. Attending in a targeted fashion to such critical voices might open a multitude of possibilities for students, their families, and educators. This study underscores experiences of navigating school life for children with RAD and/or DSED and their parents. In this way, this paper fills a critical gap in the literature in the area of curriculum and instruction. The findings demonstrate how children with RAD may have complex needs, which is also supported with previous research (Vasquez and Stensland, 2016).

Our work particularly underscores that parents may have deep insights into their children that can be tapped into as a significant resource. School staff may listen to parents as a means for constructing effective bridges between home and school for students with RAD. Parents may further inform teachers and other school members of useful information that might support student learning, school-based peer engagement, and overall success in an academic setting. For example, it is common that students with RAD sabotage relationships or events on purpose. Cain (2006) stated that children with RAD may be operating from a core belief of shame, and they suffer from feelings of low self-esteem or feel they are unworthy of love. Over time, this state of shame can become normal for these children. Cognitive distortions with associated irrational beliefs may also become part of a normal behavioral pattern (Yell et al., 2009). Any disruption of the belief system will cause disequilibrium (Cain, 2006). Children with RAD will thus do whatever is necessary to sabotage an event or relationship that disputes their belief system. If they disrupt the event or relationship, they can return to what is their normal state of equilibrium. The findings in this study hint at challenges facing children with RAD with sustaining peer relationships. Further examination of peer relationships in school among children diagniosed with RAD may be important given the relevance of engagement with peers in school (DeVries et al., 2018), and more extensive research focused on relationship saboatge as it relates to curricular engagement may be informative for educators and other school staff suporting students with RAD/DSED.

The narratives that we highlighted here thus shed much light on how students with RAD and/or DSED might experience social barriers in school that might impact their interactions inside and outside of classrooms. An understanding of these barriers might be relevant so that teachers can work to aid students with RAD/DSED in successfully working together with peers and in making friends. This might improve academic activities requiring group work, and making friendships is further significant for students to sustain an identity as someone who belongs in a class or a school (Clandinin et al., 2006).

While the participants in this study depicted how they felt as though they were not heard by schools regarding the care and education of their children with RAD (and/or DSED), they also highlighted their sense that adequate learning supports were often not put into place for their children despite parent requests. Moreover, our participants also expressed their perception that school staff did not have a depth of knowledge about RAD/DSED as a disorder or detailed practical training to address the needs of their children with RAD (and/or DSED). This may point further to the value of envisioning parents as a critical component of a learning team.

5 Recommendations

This study offers rich and layered insights into the experiences of families of children with RAD in connection with schools. Deliberating over their voiced experiences brings to light several recommendations for improving equitable and accountable professional practice among students with attachment disorders, and especially among students with RAD.

Educators can improve their interactions among students with RAD by becoming cognizant of common RAD thought patterns. Our discussion of findings above highlight some of the ways in which typical classroom interactions might actually act as triggers for students with RAD and may result in serious behaviors. Regular behavior interventions do not work with students with RAD (Floyd et al., 2008). According to Cain (2006), corrective therapy for children with RAD requires a variety of strategies including those that belong to trauma therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Targeted training in RAD is needed to aid educators in designing appropriate supports and interventions for this group of students.

Effective school/family partnerships are critical for students with RAD. Families better understand their children, especially when it comes to behaviors such as proactive planning of behaviors and triangulation and manipulation of caregivers (Thomas, 2005; Cain, 2006). Such partnerships might help to ensure that IEPs are provided and adequate support is provided that streamlines procedures between the home and the school. What is needed is an early and intense systems approach to address the needs of children with challenging behaviors (Farmer et al., 2001) if support for these children is to lead to positive outcomes. School/family partnerships may also be useful to capture student behavior that might be different in public and private spaces.

One of the core characteristics of this disorder is exactly why the teachers and/or administrators “do not see it.” These children may well have quite a show-quality capacity for managing behavior in public. Indeed, some behave in a way completely unseen by the foster or adoptive parents at home. This very fact tends to isolate parents, since no one else is seeing what they see. Isolated parents begin to bog down, become vulnerable to depression, and get defensive. And the child gets worse (Trout, 2016).

We are not referring here to criteria used to diagnose RAD. Instead, we discuss public and private behavior management as an additional associated feature of RAD (Lehmann et al., 2016). Attending to parents’ experiences with their children with RAD might be important for recognizing and tracking behaviors, removing the possibility of not trusting parent observations or for potentially blaming parents for their children’s behaviors. Removing stigmas from parents regarding the behavior of their children may in turn serve to improve dialogue between the school and home as a vital step in working with the behaviors of students with RAD.

It is further critical to consider the role that school administrators may play in curricular oversight, resource allocation, and final decisions regarding student discipline. School administrators also set the tone for a school culture regarding inclusivity. This study underscores how school cultures might be developed to support attachment diversity across the school landscape. School leaders may also incorporate more professional development opportunities for faculty and other school staff that targets the attachment needs of students and their families with respect to student learning.

Schools that become more responsive to the mental health and behavior challenges of students and their families set the tone for societal growth in terms of supporting and sustaining individuals in their holistic complexity. This approach may begin within teacher education programs so that student teachers will be primed to deal with both classroom management and student support through a home-school team rather than in isolation. Including parental input to form decisions affecting students rather than after such decisions have been made could prove to be a valuable bridge between students’ home and school lives. This may be especially useful with students who have a complex attachment disorder such as RAD.

5.1 Study limitations

Each of the children of the parent participants were diagnosed with RAD prior to the re-classification of RAD with the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). It is then possible that the children of our parent participants actually have symptoms of RAD/DSED. A potential limitation of this study is that the children were not diagnosed using the information that would guide healthcare workers with new diagnoses today. However, it is important to capture the experiences of families who have children who receive diagnoses within given temporal contexts, as that is illuminating in terms of possible shifting norms for treatment and care.

A further limitation of this study is that for most of the children, multiple diagnoses were made along with RAD. These included comorbid disabilities such as Behavior Disorder and Conduct Disorder. However, the focus of interviews with parent participants was on RAD diagnoses and experiences as they related to RAD. Formal data regarding additional diagnoses were not collected and they were offered to us without supporting details in an informal manner by some of the parent participants. It is worthwhile to note that for each of the parent participants, RAD was specifically cited as the factor that was associated with challenges with school-home bridges and their children’s schooling engagement.

The participant sample is a further limitation of this study. All parent participants were educated, middle class professionals. Many of them work in education or social work related fields and have experience navigating schooling. All parent participants adopted and/or fostered their children with RAD. Many of them were also members of the same support group. A more diverse pool of participants and participants who do not regularly engage in discussion with each other such as within the support group may bring to light different experiences. In addition, one participant was known to one of the researchers. However, care was taken to follow the same interview protocol for all interviews. Including both researchers in data analysis individually and jointly also reduced the potential for researcher bias. Further research in this area with a larger and more diverse participant pool that includes both parents’ experiences and children’s experiences could add more nuanced findings to those explored here.

5.2 Educational significance of the study

The narratives that we collected from several families of children with RAD focus on their schooling experiences. The stories intermingle issues of behavior, social connections, and academic success. The qualitative focus of the study sheds light on social, academic, and familial facets of RAD among school-aged children, which may prove relevant for depicting experiences of RAD across home and school for older children. Although this study is not generalizable, such data may be informative for diagnosing RAD among older children. It is further of the utmost significance to attend to schooling experiences from the standpoint of the families of this group of students, who might not fit into the current system of accountability within schools.

Teachers and schools might be shaping their accountability efforts in terms of teaching to the test, and this perspective has been supported in schools through educational policies, such as No Child Left Behind and the Common Core State Standards Initiative. Yet, students and their families might have different notions of accountability in education that are linked to their needs and experiences within and across school and home settings (Chan and Schlein, 2015). In this article, we address this crucial tension between education policies and student and family needs.

Attending to the narratives of families and of students might further prove to be a valuable resource for shaping curricular interactions with all learners. Knowledge gained from this inquiry might be used to improve classroom encounters between general education teachers in mainstream classrooms and their students. This article might be helpful as a source of information for new teachers in teacher education classes or as educator professional development with respect to finding new ways of understanding and relating to students with special needs. Resource workers, paraprofessionals, and special education support workers might also benefit from this work via enhanced knowledge about the perspectives and mindset of students with RAD and/or DSED.

This study may also prove to be a springboard for further studies. It may be useful to attend longitudinally to students’ voices regarding their experiences with RAD/DSED and schooling. Qualitative research into the storied perspectives of educators and school administrators may also bring to light issues pertaining to practice and professional development while adding to the literature base.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Missouri-Kansas City. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge and thank participants for their time and energy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th Edn American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 5th Edn American Psychiatric Association.

Barth, R. P., Thomas, M. C., John, K., Thoburn, J., and Quinton, D. (2005). Beyond attachment theory and therapy: towards sensitive and evidence-based interventions with foster and adoptive families in distress. Child Family Soc Work 10, 257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00380.x

Bennett, D. S., Sullivan, M. W., and Lewis, M. (2005). Young children’s adjustment as a function of maltreatment, shame, and anger. Child Maltreat. 10, 311–323. doi: 10.1177/1077559505278619

Buckner, J. D., Lopez, C., Dunkel, S., and Joiner, T. E. (2008). Behavior management training for the treatment of reactive attachment disorder. Child Maltreat. 13, 289–297. doi: 10.1177/1077559508318396

Cain, C. S. (2006). Attachment disorders: treatment strategies for traumatized children. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson

Chaffin, M., Hanson, R., Saunders, B. E., Nichols, T., Barnett, D., Zeanah, C., et al. (2006). Report of the APSAC task force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreat. 11, 76–89. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283699

Chan, E., and Schlein, C. (2015). Standardized testing, literacy, and English language learners: lived multicultural stories among educational stakeholders, Handbook of research in middle level education: Research on teaching and learning with the literacies of Young adolescents, (Eds.) K. Malu and M. B. Schaefer, Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 21–48

Clandinin, D. J. , (Ed.) (2007). Handbook of narrative inquiry: mapping a methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (1995). Teachers’ professional knowledge landscapes. New York: Teachers College Press

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Murray Orr, A., Pearce, M., et al., (2006). Composing diverse identities: narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers. New York: Routledge

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (1991). Narrative inquiry: storied experience, E. Short (Ed.), Forms of curriculum inquiry, New York: State University of New York Press, 121–152

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/ Prentice Hall

Davis, A. S., Kruczek, T., and McIntosh, D. (2006). Understanding and treating psychopathology in schools: introduction to the special issue. Psychol. Sch. 43, 413–417. doi: 10.1002/pits.20155

Del Duca, M. (2013). Kid confidential: What reactive attachment disorder looks like. The ASHA Leader Blog, Available at: http://blog.asha.org/2013/07/11/kid-confidential-what-reactive-attachment-disorder-looks-like/

DeVries, J. M., Rathmann, K., and Gebhardt, M. (2018). How does social behavior relate to both grades and achievement scores? Front. Psychol. 9:857. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00857

Farmer, T. W., Quinn, M. M., Hussey, W., and Holahan, T. (2001). The development of disruptive behavioral disorders and correlated constraints: implications for intervention. Behav. Disord. 26, 117–130. doi: 10.1177/019874290102600202

Floyd, K. K., Hester, P., Griffin, H. C., and Golden, J. (2008). Reactive attachment disorder: challenges for early identification and intervention within the schools. Int. J. Special Educ. 23, 47–55.

Gleason, M. M., Fox, N. A., Drury, S., Smyke, A., Egger, H. L., et al. (2011). Validity of evidence-derived criteria for reactive attachment disorder: indiscriminately social/disinhibited and emotionally withdrawn/inhibited types. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50, 216–231.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.012

Grcevich, S. (2016). DSM-5: Rethinking reactive attachment disorder. Key Ministry, Available at: https://www.keyministry.org/church4everychild/2016/4/3/dsm-5-rethinking-reactive-attachment-disorder

Guyon-Harris, K. L., Humphreys, K. L., Fox, N. A., Nelson, C. A., and Zeanah, C. H. (2019). Signs of attachment disorders and social functioning among early adolescents with a history of institutional care. Child Abuse Negl. 88, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.005

Hall, S. E. K., and Geher, G. (2003). Behavioral and personality characteristics of children with reactive attachment disorder. J. Psychol. 137, 145–162. doi: 10.1080/00223980309600605

Hanson, R. F., and Spratt, E. G. (2000). Reactive attachment disorder: what we need to know about the disorder and implications for treatment. Child Maltreat. 5, 137–145. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005002005

Hildyard, K. L., and Wolfe, D. A. (2002). Child neglect: developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 26, 679–695. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00341-1

Kennedy, J. H., and Kennedy, C. E. (2004). Attachment theory: implications for school psychology. Psychol. Sch. 41, 247–259. doi: 10.1002/pits.10153

Kremer, K. P., Flower, A., Huang, J., and Vaughn, M. G. (2016). Behavior problems and children’s academic achievement: a test of growth-curve models with gender and racial differences. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 67, 95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.06.003

Lehmann, S., Breivik, K., Heiervang, E., Havik, T., and Havik, O. E. (2016). Reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in school-aged foster children: a confirmatory approach to dimensional measures. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 44, 445–457. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0045-4

Lyons, S., Whyte, K., Stephens, R., and Townsend, H. (2020). Developmental Trauma Close Up. Beacon House

Miller, L., Chan, W., Tirella, L., and Perrin, E. (2009). Outcomes of children adopted from Eastern Europe. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 33, 289–298. doi: 10.1177/0165025408098026

Minnis, H., Macmillan, S., Pritchett, R., Young, D., Wallace, B., et al. (2013). Prevalence of reactive attachment disorder in a deprived population. Br. J. Psychiatry 202, 342–346. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.114074

Musoleno, R. R., and White, G. P. (2010). Influences of high-stakes testing on middle school mission and practice. Research in Middle Level Education Online. 34, 1–10.

O’Connor, T. G., Bredenkamp, D., and Rutter, M. (1999). Attachment disturbances and disorders in children exposed to early severe deprivation. Infant Ment. Health J. 20, 10–29. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199921)20:1<10::AID-IMHJ2>3.0.CO;2-S

Raaska, H., Lapinleimu, H., Sinkkonen, J., Salmivalli, C., Matomäki, J., Mäkipää, S., et al. (2012). Experiences of school bullying among internationally adopted children: results from the Finnish adoption (FINADO) study. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 43, 592–611. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0286-1

Schlein, C., Taft, R. J., and Ramsay, C. M. (2016). The intersection of culture and behavior: intercultural competence, transnational adoptees, and social studies classrooms. J. Int. Soc. Stud. 6, 128–142.

Schwartz, E., and Davis, A. S. (2006). Reactive attachment disorder: implications for school readiness and school functioning. Psychol. Sch. 43, 471–479. doi: 10.1002/pits.20161

Seim, A. R., Jozefiak, T., Wichstrøm, L., and Kayed, N. S. (2019). Validity of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder in adolescence. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 29, 1465–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00787-019-01456-9

Shaw, S. R., and Páez, D. (2007). Reactive attachment disorder: recognition, action, and considerations for school social workers. Child. Sch. 29, 69–74. doi: 10.1093/cs/29.2.69

Skovgaard, A. M. (2010). Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. An epidemiological study. Dan. Med. Bull. 57:193.

Taft, R. J., Ramsay, C. M., and Schlein, C. (2015). Home and school experiences of caring for children with reactive attachment disorder. J. Ethnograp. Qualitat. Res. 9, 237–246.

Taft, R. J., Schlein, C., and Ramsay, C. M. (2016). Experiences of school and family communications and interactions among parents of children with reactive attachment disorder. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 15, 66–78.

Thomas, N. L. (2005). When love is not enough: A guide to parenting children with RAD-reactive attachment disorder. Glenwood Springs, CO: Families By Design

Trout, M., and Thomas, L. (2005). The Jonathon letters: One Family’s use of support as they took in, and fell in love with, a troubled child. Champaign, IL: The Infant-Parent Institute

Vasquez, M. L., and Miller, N. (2017). Aggression in children with reactive attachment disorder: a sign of deficits in emotional regulatory processes? J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 27, 347–366. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1322655

Vasquez, M. L., and Stensland, M. (2016). Adopted children with reactive attachment disorder: a qualitative study on family processes. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 44, 319–332. doi: 10.1007/s10615-015-0560-3

Yell, M. L., Meadows, N. B., Drasgow, E., and Shriner, J. G. (2009). Evidence–Based Practices for Educating Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Zeanah, C. H., and Boris, N. (2000). Disturbances and disorders of attachment in early childhood. C. H. Zeanah (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health, 353–368. The Guilford Press

Zeanah, C. H., Chesher, T., and Boris, N. (2016). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 990–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.08.004

Keywords: attachment disorders, parents and families, school and home connections, educational accountability, stories of experience

Citation: Schlein C and Taft RJ (2023) Attending to the voices of parents of children with Reactive Attachment Disorder. Front. Educ. 8:1146193. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1146193

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Minna Körkkö, University of Oulu, FinlandClaire Davidson, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Schlein and Taft. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Candace Schlein, c2NobGVpbmNAdW1rYy5lZHU=

Candace Schlein

Candace Schlein Raol J. Taft

Raol J. Taft