- Multidisciplinary Institute Teacher Education, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Brussels, Belgium

Introduction: A democratic school culture has been identified in previous research as a lever for the development of deliberative competences. However, the antecedents of deliberative competence development at school level are less examined. Therefore, this study investigated the impact of student characteristics (age, gender, finality), urban school contexts (location of the school, socioeconomic and cultural characteristics of the student population) and different dimensions of the perceived democratic school culture (fair support, responsibility, co-decision, discussion, acceptance) on students’ mastery of three deliberative competences: tolerance, curiosity, and empathy.

Methods: A multilevel analysis of a survey, completed by 5,165 Dutch-speaking Belgian secondary school students was conducted.

Results: This study revealed the importance of the perceived fair support from teachers, opportunities to discuss, and acceptance by peers at school for the mastery of deliberative competences. Furthermore, urban schools were discovered to be strong negative predictors of all three competences, although fair support and discussion opportunities appear to partially compensate for this effect.

Discussion: These results highlight the importance of a democratic school culture, especially in urban schools, for developing empathy, tolerance, and curiosity. Moreover, the detailed results of this study could guide urban school teams in shaping democratic learning environments.

Introduction

In many Western countries, deliberative competences are part of the national goals for citizenship (Veugelers et al., 2017). In Flanders, for example, all secondary school students are expected to “engage in informed and reasoned dialogue” (AHOVOKS, 2021). To achieve such deliberation, students must possess the necessary (communicative) skills and values, allowing them to listen, to express and substantiate their opinions, to think critically, and to debate in a respectful and inclusive manner (Gutmann and Thompson, 2004; de Groot and Lo, 2020). Furthermore, a context in which they feel free and equal is required for reciprocity between participants to develop (Gutmann and Thompson, 2004). Schools have a key role to play in this regard: students can strengthen their deliberative competences by practicing them in the real-life settings of everyday school life (e.g., Englund, 2006). It is inferred that for schools to be genuine places of practice for deliberative competences, they must establish a democratic context and organizational structures that allow students to participate in deliberation and decision making at school (de Groot and Lo, 2020). Many researchers have examined the impact of the school environment on a variety of democratic outcomes, such as participation (e.g., Simó et al., 2016), sense of community (e.g., Vieno et al., 2005), and intentions to vote (e.g., Sampermans et al., 2018). Nonetheless, its impact on the development of deliberative competences has rarely been studied. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine whether the experience of a democratic school culture relates to the development of students’ deliberative competences by means of multilevel analyses on survey data of students in Dutch-speaking public schools in Belgium.

Theoretical perspectives

Democratic school culture

School culture at large refers to “the general atmosphere or feel of the school” (Hoy, 1990, p. 163). It is a complex concept that, on the one hand, captures the values, beliefs, and norms adopted in a school organization; on the other hand, it involves the social realities, i.e., behaviors and relationships, that determine the daily life of the school (Ostroff et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2015). There is a disagreement among scholars about the exact relationship between these two components (Prosser, 1999). Some researchers consider them complementary and integrate them. Others see them as separate constructs, school culture and school climate, respectively, (e.g., Hoy, 1990). The operationalization of school culture is often based on multiple dimensions that, rooted in a value framework, capture the social reality in a school, with dimensions such as respect for diversity, positive relationships, participation (Zullig et al., 2010; Thapa et al., 2013; Voight and Nation, 2016; Rudasill et al., 2018).

Democratic school cultures, which recently gained research interest, are defined as school cultures that draw on democratic values and norms as a “basis for nurturing and developing democratic relationships in schools” (Pažur et al., 2021, p. 1138). Deliberative democratic theorists underline the importance of school culture for the development of deliberative competences (Gutmann and Thompson, 2004; Dryzek, 2009; Elstub, 2012; de Groot and Veugelers, 2016; Griffin, 2020). Rooted in the work of Dewey (2001), they suggest that an immersive democratic school environment provides a vital lever for young people to experience and learn democracy. Accordingly, de Groot and Eidhof (2019) define democratic school culture as “a way of life that, in line with democratic values, fosters respectful relations at the interpersonal level, and between groups of citizens, and seeks a more inclusive society” (p. 364), attributing a pivotal position to the values of respect and equality. In order to operationalize democratic school environments, Sampermans (2018) related these values to three social dimensions of school climate: (1) the schools’ rules emphasize the social foundation of conventions and rulemaking at school, (2) the relationships represent respectful interactions between students and teachers and among peers, and (3) the teaching and learning practices aim, in addition to general learning activities, at citizenship development. De Groot and Lo (2020) focused on how democratic school cultures manifest themselves. They identified three axes upon which school practices could be situated: individual versus community-oriented aims of education, education versus participation activities, and basic versus critical perspectives. By combining these axes, an eight-sector framework emerged, capturing the spectrum of democratic experiences at schools. The school environments closest to deliberative democracy theory are: (1) conducting participatory activities, (2) from a critical perspective, (3) for community-oriented aims. Such democratic experiences thrive best in a school culture that encourages respectful interactions with and among students, that creates spaces for co-construction of the learning environment, and gives a voice to all students. De Groot and Lo (2020), however, warn that such democratic school culture may prove challenging, “not only because it is the most active and critical educational experience …, but also because [it] prompts students to critically address a systemic conundrum, which can seem revolutionary to some administrators and parents” (p. 8).

Even though empirical research on the impact of democratic school cultures on students’ competence development appears to be limited, four secondary school studies were relevant to the current study. All of them investigated the relationship between school culture and the development of diverse democratic competences at the student level through survey studies. Flanagan and Stout (2010) discovered a link between democratic school culture, social trust and age in a survey study with 1,535 adolescents. Young adolescents were found to have higher levels of social trust than middle and late adolescents. The researchers explained these differences by a growing emphasis on personal friendships at the expense of the overall social context and an increasing hardening of beliefs about people’s trustworthiness. Yet, regardless of age, a democratic school culture was found to exert a positive influence on students’ social trust. Accordingly, the study emphasized the role of schools in nurturing students’ democratic dispositions. Lenzi et al. (2014) found that a more democratic school climate encourages students to participate in civic activities. They concluded that this link is entirely mediated by students’ school experiences of openness and fairness. In contrast to their hypothesis and the studies mentioned, Keating and Benton (2013) found in their longitudinal study that a democratic school environment had no positive impact on those of the students’ attitudes and behaviors that are associated with community cohesion. They explained this discrepancy by contextual differences and by the need for optimization of their measuring instruments, i.e., measuring the construct of a democratic school culture multidimensionally and including the perspective of cultural and ethnic minorities. The study on students’ mastery of democratic competences in Flemish education (AHOVOKS, 2017) found that schools that encourage open dialogue between students and teachers contribute to competence development by this school culture. It also revealed that nearly all students in general education achieve the intended level of the competences measured (i.e., trust in institutions, critical thinking and equality), whereas only half of the students in vocational education do. The researchers presumed that the latter is caused by the ambiguous position of citizenship education in the curriculum. Although these four studies concluded that democratic school cultures and competence development are related, they also presumed that the underlying dimensions of democratic school culture are even stronger predictors of student-level outcomes, arguing for more research in this regard.

Urban schools

Urban schools are conceptualized by Milner and Lomotey (2017, p. 15) as schools that (1) are located in dense, large, metropolitan areas; (2) have a highly diverse student population, comprising racial, ethnic, religious, language, and socioeconomic characteristics; and (3) are endowed with limited resources, such as technology and financial structures. According to previous research, students in urban schools have more difficulty developing democratic competences than students in non-urban schools (Hart and Atkins, 2002). Hart and Atkins (2002) explained this by the disadvantaged context of urban students, characterized by low participation rates of urban adults, by the lack of educational resources, and by less involvement in voluntary and leisure activities in clubs and teams outside of school. Such a context yields fewer opportunities for democratic experiences and less access to democratic knowledge or resources, thereby affecting their citizenship conceptualization and learning (Biesta et al., 2009; Castro and Knowles, 2017).

Furthermore, research has focused on the influence of various demographic characteristics associated with urbanization—in particular socio-economic or ethno-cultural characteristics—on the development of students’ democratic competences (Castro and Knowles, 2017). In terms of socioeconomic characteristics, higher levels of deprivation in the student population have been found to negatively affect students’ civic attitudes and behavior (Keating and Benton, 2013). Regarding the ethnic cultural characteristics of students, Flanagan et al. (2007) found that students from minority groups display more cynicism, lower confidence in the authorities and less perceived potential for social mobility. Their personal experiences of discrimination were found to be a determining factor. The influence of the cultural diversity of the school population on citizenship outcomes has been studied frequently, but has not been conclusive to date. For instance, Janmaat (2010) found that ethnic majority students in Germany and Sweden had more tolerant attitudes towards minorities the more diverse their school population was, a finding that leads the authors to conclude that desegregation helps to combat racial prejudice. In contrast, Kokkonen et al. (2010) revealed that ethnic diversity has a detrimental contextual effect on students’ development of democratic knowledge. After controlling for knowledge, students’ confidence and tolerance appear to be unaffected by diversity. While urbanism influences the development of democratic competences, there remains a lack of empirical research on the exact impact of these contextual factors and the potentially remedial role that urban schools may fulfil.

Deliberative competences

According to deliberative democratic theorists, deliberative competences are the abilities that equip students to engage in deliberation, or democratic discourse towards collective decision-making (Benhabib, 1996; Gutmann and Thompson, 2004). Since it represents the “talk-centric” (Chambers, 2003) idea of democracy, the participants in deliberation need to be primarily communicative (Habermas, 1996; Young, 1996; Dryzek, 2009; Englund, 2011). Moreover, deliberative communication should be imbued with reciprocity, tolerance, and respect (Habermas, 1996; Gutmann and Thompson, 2004; Englund, 2011).

Although a multitude of studies have operationalized overall democratic competences, mostly informed by multiple conceptions of democracy (e.g., Jónsson and Garces Rodriguez, 2021), the specific focus on deliberative competences remained underexplored, except for a few studies. Murray (2013), for example, identified a cognitive and a social dimension in deliberative communication, focusing, respectively, on arguing and reflecting, and engaging and coping with multiple perspectives. In their recent work, Jónsson and Garces Rodriguez (2021) distinguished seven manageable democratic competences needed to accomplish the Deweian concept of democracy. Three of these are communicative in nature. First, the discursive competence refers to the ability and the willingness to engage in a dialogue with others. This competence necessitates the ability to express and explain one’s own ideas, as well as to listen to those of others. It encompasses both openness and a willingness to learn from one another, as well as honesty and respect to engage in a genuine dialogue. The second skill is conflict resolution, which entails formulating and defending a personal point of view based on arguments while maintaining respect for others’ dignity, culture, and rights. It necessitates the ability to combine debating and problem-solving. Finally, the critical revaluation competence refers to the ability to consider personal and cultural imperatives. It takes courage, willingness, and skill to openly question authority and power, reconsider positions, and propose alternatives.

Purpose of the study

A democratic school culture has been identified in previous research as a lever for the development of deliberative competences. It is less clear what the antecedents of deliberative competence development are, both in terms of characteristics of a democratic school culture and in terms of characteristics of an urban student population, and how these interact (Keating and Benton, 2013; Lenzi et al., 2014). It is important that research that addresses the complexity and multi-layered nature of education for learning democracy simultaneously investigates multiple influences (Castro and Knowles, 2017). This research investigates how different characteristics of urban schools, as well as students’ different experiences of school cultures, are related to three deliberative competences. This study was guided by the following research questions:

•How do characteristics of students and their experiences with the school culture affect their mastery of deliberative competences (tolerance, empathy, curiosity)?

•Are differences in the mastery of deliberative competences related to attending an urban school?

Method

Context and participants

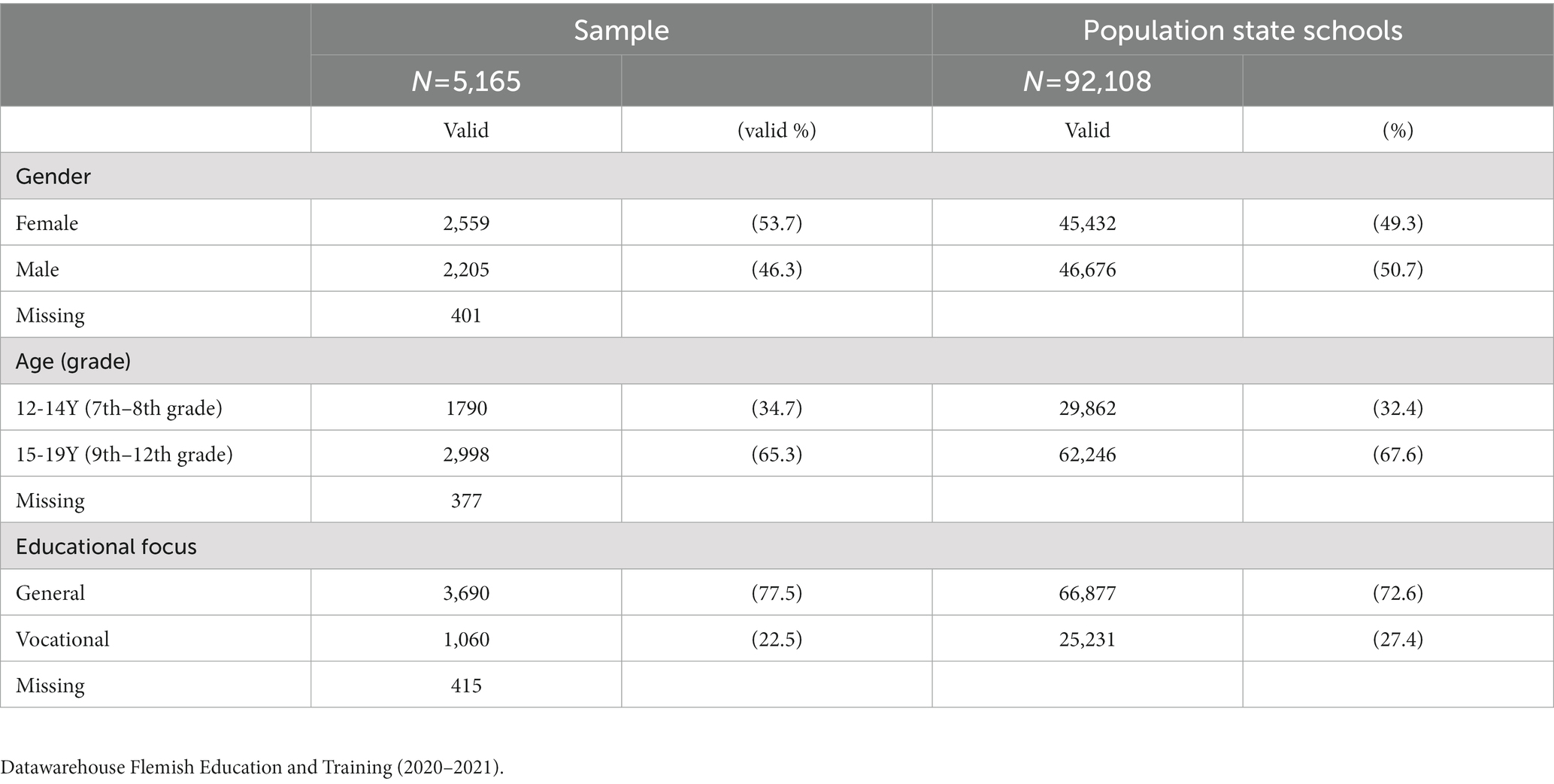

The sample included 5,165 secondary school students from 30 Dutch-speaking Belgian state schools. In the period of 2019–2021, the survey was distributed by the state school association to all its secondary schools, which subsequently decided whether to present it to (a part of) their student population. This sample represents 5.61% of the total state school student population. In terms of gender, age and educational focus, the distribution of the sample approximates that of the total population (Table 1). The mean age of the participants was 14.7 years (SD = 2.3 years, age range: 11–19 years). Approximately as many boys as girls participated (nboys = 2,205, 53.7%; ngirls = 2,559, 46.3.0%). 77.5% of the participants attended general secondary education, preparing for higher education.

Measures

Deliberative competences

The deliberative competences of students were measured by means of the Deliberative Competences (DC) instrument. This instrument was developed by the Flemish state school association to assess the mastery of civic competences among its secondary school students. The DC consists of 11 items that are rated on a five-point Likert scale according to level of agreement, from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The DC distinguishes three subscales: (1) the four-item tolerance scale, assessing how much students in a conflict are focused on actively contributing to a constructive and well-considered solution (e.g., “I think it is important to deal with conflicts in a positive way.”), (2) the three-item curiosity scale, examining the extent to which students are open to discovering new, unfamiliar situations or contexts (e.g., “I like to learn about other cultures.”), and (3) the four-item empathy scale, measuring to what extent students are able or willing to consider the perspective of others, especially in unfair situations (e.g., “I think it is important that people listen to each other, even if their opinions differ.”). A confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the three distinct constructs (RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.95) indicating a good model fit (Little, 2013). The Cronbach’s alphas indicated an acceptable to good internal consistency, respectively 0.75 for tolerance, 0.79 for curiosity and 0.81 for empathy.

Student characteristics (student-level variable)

To control for certain student characteristics, the variables age, gender, and type of qualification were measured, all of which were coded in categories: gender was coded with 0 = male and 1 = female, age was scored with 1 = <12Y, 2 = 12-14Y, 3 = 15-16Y, 4 = 17-18Y, and 5 = 19–19 + Y, and the finality was coded with 0 = vocational and 1 = general.

Immersive democratic school culture scale (student-level variable)

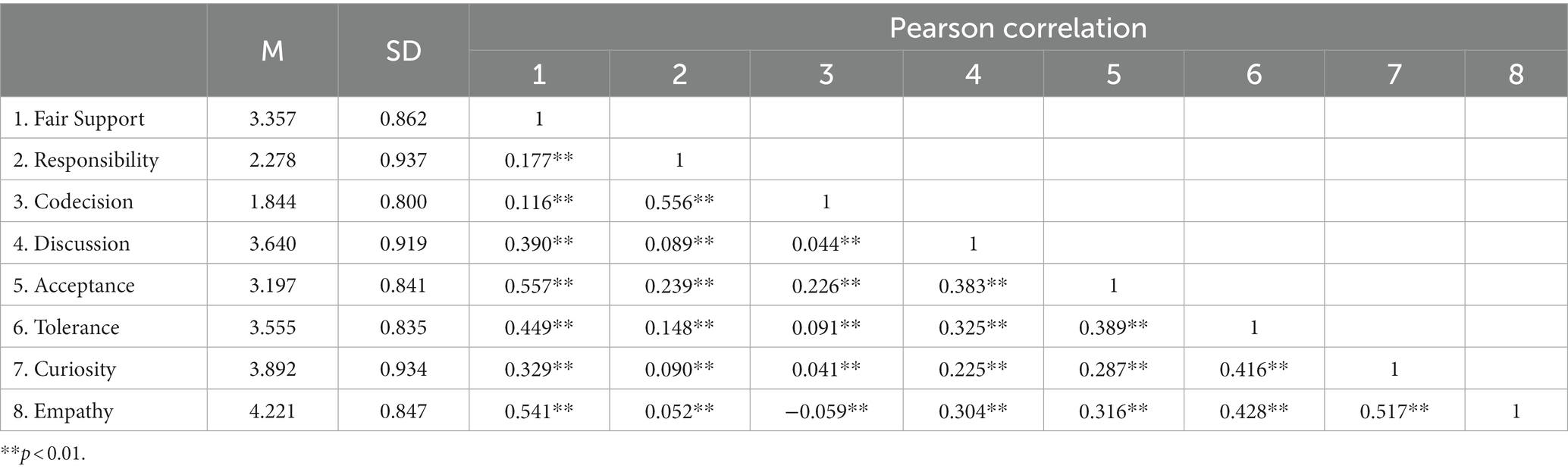

Democratic school culture was measured by the Immersive Deliberative School Culture (IDSC) instrument, rooted in theoretical and empirical understandings on predictors in classroom and school environments that promote active citizenship (e.g., Brown and Evans, 2002; Vieno et al., 2005; Appleton et al., 2008; Zullig et al., 2010; Castillo et al., 2015; Voight, 2015; Karakos et al., 2016). The IDSC consists of five scales: (1) the five-item fair support scale, indicating the students’ experiences on equal and fair treatment at school (e.g., “The teachers care about me”), (2) the ten-item responsibility scale, referring to the opportunities for students to take responsibility at school (e.g., “I am given co-responsibility for classroom activities”), (3) the nine-item co-decision scale, relating to the opportunities for students to participate in decision-making processes (e.g., “I can participate in decisions about school rules”), (4) the four-item discussion scale, indicating the opportunities for students to practice their discussion skills (e.g., “The teachers encourage me to share my opinion with others”), and (5) the three-item acceptance scale, concerning the students’ perception of being accepted by their peers (e.g., “The pupils care for me”). Together, the five scales comprise 31 items, each of which is rated on a five-point Likert scale on either recognizability of the situation, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree, for the scales fair support and acceptance, or on frequency, ranging from (1) never to (5) always, for the scales responsibility, co-decision, and discussion. Confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the five-factor structure for the IDSC, with acceptable values of fit (RMSR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.91). Moreover, the internal consistency of these five scales is high, with Cronbach’s alpha between 0.78 (acceptance) and 0.92 (responsibility). The correlation matrix (Table 2) reveals low or weak correlations between the competence and school culture scales, indicating distinct constructs.

Table 2. Correlation between Immersive Democratic School Culture (IDSC) and Deliberative Competencies (DC).

Urban schools (school-level variable)

When respondents complete the survey, it is indicated which school they attend. This information allows us to identify urban schools, operationalized as schools in a metropolitan area with a school population that is characterized by severe socioeconomic and cultural deprivation (Milner and Lomotey, 2017). To this end, first, the “Indicator of Deprivation” (ID), as provided by the Flemish government, is used. The ID is calculated by adding the percentages of four different indicators: (1) The language indicator represents the proportion of students in the school population who do not speak Dutch at home, (2) the educational degree of the mother indicator represents the proportion of students in the school population whose mother has at least a lower secondary school diploma, (3) the financial situation indicator represents the proportion of students in the school population who are eligible for a scholarship, and (4) the neighborhood indicator represents the proportion of students in the school population who live in a neighborhood where many peers have a school delay. The national ID average fluctuates marginally each year, tending to be around 1. On that basis, schools with severely above-average deprivation (ID = 2.00–4.00), and that are located in a metropolitan area, are assigned the code 1 = urban. In this study, all schools that did not meet both conditions were classified as non-urban (0 = non-urban).

Analysis

A multilevel modelling technique was chosen to respect the non-independence of observations (students within schools) and thus the hierarchical nature of the data structure. Moreover, this technique accounts for the correlated error structures of students within the same school context (Luke, 2004). A multilevel analysis was conducted using a linear mixed model procedure with a two-level design in SPSS 23.0, examining the effects of individual student characteristics (level 1), school characteristics (level 2) and characteristics of students attending urban schools (cross-level) on the outcomes of each of the three deliberative competences under scrutiny. First, null models without covariates were constructed to estimate the amount of variance in students’ deliberative outcomes for the individual and the school level. Subsequently, two models were tested by adding different explanatory variables. The within-school model (model 1) estimates the influence of the five scales of democratic school culture on each of the three deliberative competences for students in the same school, while controlling for student characteristics (gender, age, finality). The between-school model (model 2) explores whether an urban school context (level 2) and the school culture in urban schools (cross level interaction) can explain between-school differences in the three deliberative competences. Using the likelihood ratio test (LRT), the difference in deviance between the models was determined to assess whether it fitted the data significantly better than the previous models (Luke, 2004).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics (mean scores and standard deviations) and bivariate correlations are presented in Tables 2, 3. The correlation matrix (Table 2) reflects the associations between the DC and IDSC scales, revealing that students rated themselves on average high or rather high on all three DC scales (meanempathy = 4.221; meancuriosity = 3.892; meantolerance = 3.555). At school (IDSC), students overall experience ample opportunities for discussion (meandiscussion = 3.640), but only very few chances for codecision and taking responsibility (meancodecision = 1.844; meanresponsibility = 2.278). Furthermore, Table 2 indicates that the scales of both instruments correlate very weakly or weakly with one another, except for the moderate bivariate correlation that is found between fair support and the DC scales tolerance (r = 0.449, p < 0.01) and empathy (r = 0.541, p < 0.01), confirming that different constructs are captured.

Table 3 presents the differences in scores on tolerance, curiosity, and empathy, examined by means of an independent samples t-test, between (1) urban and non-urban schools, and (2) more or less democratic school cultures, combining all school-level variables. It is notable that students in urban and non-urban schools do not score significantly differently on the competences tolerance and empathy. Students in urban schools have significantly lower scores on the empathy scale compared to their peers in non-urban schools. Whether or not students experienced a democratic school culture yields no difference in scores for tolerance, but those who experienced a limited democratic school culture, score significantly lower on the deliberative competences of curiosity and empathy. To investigate whether experiences of democratic school environments or urban school contexts influence the mastery of deliberative competences, we conduct a multilevel analysis.

Null model

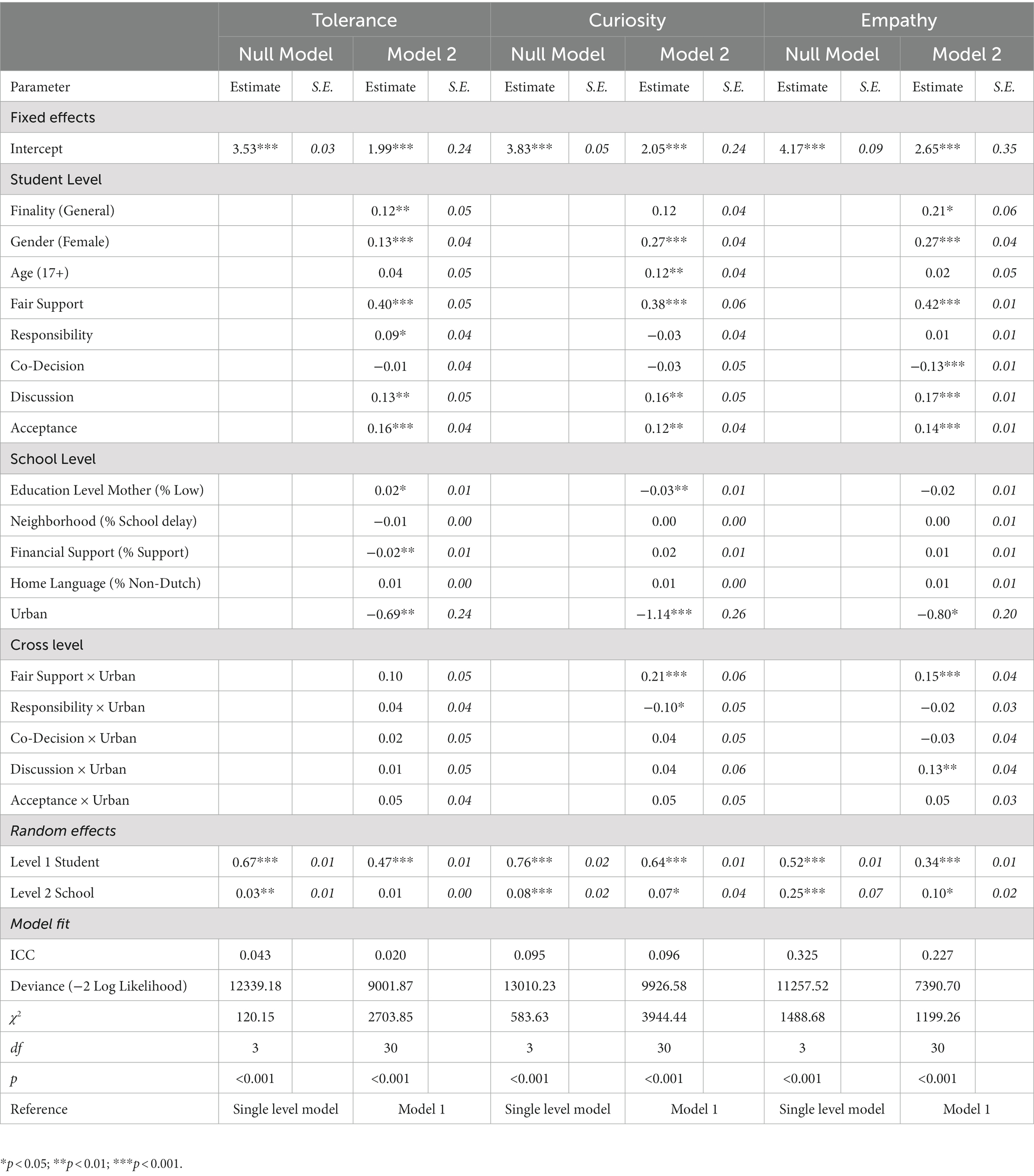

The unconditional null model allows to examine the variance in competence scores at the student level and at the school level. Table 4 indicates that for each of three competences, both the variance within the schools and the variance between the schools differs significantly from zero. Moreover, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) reveals that a significant part of the total variance in the deliberative competences, especially for the dependent variables of curiosity and empathy, is attributed to differences between schools: 4.3% for tolerance, 9.5% for curiosity and 32.5% for empathy. These ICCs confirms that a multilevel analysis, considering predictors at both student and school level, is the appropriate method for further analysis, particularly for curiosity and empathy.

Model 1

Model 1 comprises all student-level variables: the student characteristics and the five school cultural predictors. Most of these predictors show a significant effect on each of the deliberative competences. With respect to student characteristics, Model 1 predicts that at an average school, girls and students from programs that prepare for higher education score significantly higher on each of the three deliberative competences. Only on curiosity is age, at least among the oldest adolescents in the sample (+17Y), estimated to influence the score.

Regarding the school cultural predictors, fair support, discussion, and acceptance impact all three deliberative competences, with fair support showing the strongest effect (BTolerance = 0.31, p < 001; BCuriosity = 0.21, p < 001; BEmpathy = 0.31, p < 001). Co-decision appears the only school cultural predictor that affects two deliberative competences negatively (BCuriosity = −0.04, p < 05; BEmpathy = −0.10, p < 001). Overall, these results indicate that the more students perceive their school culture as democratic, the more they consider themselves competent at deliberation. The predictors at student level together explain 96.1% of the within-school variance in the mastery of tolerance, 86.7% in curiosity and 73.5% in empathy.

Model 2

Model 2 estimates the effects of the school-level variables (i.e., urban schools) and the cross-level variables (i.e., fair support x urban, responsibility x urban, co-decision x urban, discussion x urban, acceptance x urban). The chi square difference test indicated that each Model 2 differs significantly from its respective Model 1 (X2Tolerance (10) = 2703.85, p < 0.001; X2Curiosity (10) = 3051.92, p < 0.001; X2Empathy (10) = 3805.68, p < 0.001).

Examining the school context more closely, the estimates suggest that the individual deprivation characteristics of the student population contribute little, mostly negative, to one or more competences. The results further indicate that attending an urban school is estimated with the largest negative effect on the mastery of each of the deliberative competences (BTolerance = −0.69, p < 01; BCuriosity = −1.14, p < 001; BEmpathy = −0.80, p < 001). Accordingly, students in urban schools, who face metropolitan challenges associated with poverty or cultural-ethnic diversity both at home and at school, consider themselves less capable of being tolerant, curious, and empathetic.

Finally, the addition of the cross-level interactions between students in urban schools and the different dimensions of school culture yield a significant contribution to curiosity and empathy. These results indicate that students in urban schools can partially compensate for their expected lower scores on curiosity and empathy when they experience fair support (BCuriosity = 0.21, p < 001; BEmpathy = 0.15, p < 001) or opportunities for discussion (BEmpathy = 0.13, p < 01).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the school culture as perceived by students and the urban school context are predictive of mastery of the deliberative competences of tolerance, curiosity, and empathy.

Impact of students’ perceptions of the school culture

The multilevel analysis confirmed our hypothesis, revealing that the more democratic students perceived their school culture to be, the more confident they were in their own mastery of deliberative competences. These results support deliberative democratic theorists’ inferences that schools must create a democratic context for students to develop deliberative competences (Gutmann and Thompson, 2004; Dryzek, 2009; Elstub, 2012; de Groot and Veugelers, 2016; Griffin, 2020). The school culture dimensions of fair teacher support, discussion opportunities, and peer acceptance appeared to be the most influential predictors. These findings are consistent with previous empirical research. For instance, Lenzi et al. (2014) attributed better mastery of deliberative competences to experiences of openness and fairness, while AHOVOKS (2017) revealed the value of opportunities for discussion at school. Like Sampermans’s (2018) study, who identified three different, albeit related social dimensions of a democratic school culture, the present research unraveled multiple features of the school culture that simultaneously influence students’ deliberative competence development.

Somewhat surprising is that participatory activities, such as taking responsibility or codeciding at school, did not contribute or else negatively contributed to the mastery of all three competences. A possible explanation can be found in students’ experiences of participation being so limited (meanresponsibility = 1.833; meanco-decision = 2.299), compared to, for example, to discussion (mean = 3.215), that they are unlikely to be impactful. Hence, questions can be raised about the democratic quality of school cultures, in particular about the participation opportunities that schools provide. Moreover, due to the limited experiences of participation, it is not unexpected that no relationship is observed between both school cultural dimensions and the mastery of deliberative competences. Another explanation is prompted by Lundy’s (2018) work on tokenistic interpretations of participation opportunities in schools. She found that when students’ perspectives are inadequately or incorrectly heard or put into practice, this could have negative psychological effects on students (disappointment, frustration, anger) that may cause them to shun future participation. This implies that schools should not only enable participation, but also valorize it in their actions, policy, and structure.

Furthermore, the two student characteristics of finality and gender were found to influence most deliberative competences: girls tend to score higher on all three deliberative competences, and students with a curriculum that prepares for higher education rate themselves higher on tolerance and empathy. Concerning the latter, lower scores on civic competences among vocational education students in Flanders were also found in other studies (AHOVOKS, 2017; Sampermans et al., 2017), explained by less attention being paid to civic education in vocational education, in terms of curriculum, in teacher guidance, and in participation in school governance (AHOVOKS, 2017; European Commission, 2017). That age does not affect deliberative competences is echoed in other research on self-reported democratic competences, which is explained as follows: as students grow older, they acquire more knowledge and understanding of civic issues, allowing them to reflect more critically on their own roles and to rate themselves lower (Sampermans et al., 2017). In contrast, the study by Flanagan and Stout (2010) indicated that students’ social trust declines throughout adolescence, albeit a democratic school culture could counterbalance this. To argue confidently that a similar mechanism plays also for the deliberative competences under investigation, or that other explanations apply here, requires further investigation.

Impact of an urban school context

Despite the fact that the various socioeconomic indicators of deprivation have neither a univocal nor a large impact, the final multilevel model revealed that students in urban schools, in comparison to their peers in non-urban schools, scored significantly lower on tolerance, curiosity, and empathy mastery, even after controlling for student characteristics such as age, gender, and educational focus. This is in line with the findings of Hart and Atkins (2002), who discovered that urban school students are less likely than their non-urban peers to develop democratic competences, as their context holds fewer opportunities to experience democracy (Hart and Atkins, 2002; Castro and Knowles, 2017). As the definition of urban education suggests, it is a multi-faceted and complex concept (Milner and Lomotey, 2017). Students and schools in an urban region face metropolitan challenges (e.g., migration), as well as the diverse student population in the schools (e.g., socio-culturally diverse groups) and the schools’ limited resources (e.g., high teacher turnover). The findings in the present study confirmed that the interaction and occurrence of multiple factors, which reflects urban reality, amplifies the depriving effect. This may explain why, in prior research, several isolated variables, each associated with urbanism, e.g., in terms of cultural diversity, could impact differently on the mastery of democratic competences (e.g., Janmaat, 2010; Kokkonen et al., 2010). Even though the urban school context has a significant negative impact on the mastery of deliberative competences, positive student experiences with fair support from their teachers and opportunities for discussion in their urban school, as a dimension of a democratic school culture, appear to compensate. The significance of democratic school cultures in urban schools is highlighted by this finding.

Limitations and future research

Despite its strengths, some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. The primary limitation is that the sample includes only state schools of Dutch-language Belgian education. However, according to Janmaat’s (2010) research, the effects of school culture may differ across countries and regions due to different interpretations of deliberation or democratic practices. The descriptive results in this study revealed that students experienced limited participation. Therefore, the relationships between the participation variables and the mastery of deliberative competences cannot be generalized. Future research on the development of deliberative competences should take place in contexts that sufficiently and unambiguously represent democracy. A third concern relates to the data collection. On the one hand, the data collection is largely subjective in nature, as most of the surveyed scales demand self-reporting by students. On the other hand, for ethical reasons, only a limited number of individual student characteristics were asked (i.e., age, gender, finality) and specific or potentially sensitive questions were avoided. However, from previous research it is known that individual socioeconomic, ethnic, or cultural characteristics could impact the behavior or competence development of adolescents. For example, the study by Kavadias et al. (2022) revealed that Brussels adolescents of Moroccan, Turkish or Sub-Saharan African origin repeatedly experience discrimination, even within the school context. Moreover, in the same dataset, Mansoury et al. (2022) found a strong relationship between experienced discrimination and violent intentions. By only taking ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics into account at the level of the school population, we might miss relevant relationships at student level. Therefore, in future research, it is recommended to use a survey that measures competences more objectively, or which objectifies self-reported data through methodical or data triangulation, and to include more socioeconomic and ethnic data from the individual respondents.

The students in this study appeared to have little experience with the two participatory dimensions of responsibility and co-decision, even though this is recommended to achieve the democratic goals in education. It is imperative to gain more certainty about this expected relationship, which is impossible to investigate with the dataset representing no or few participatory experiences. Therefore, further research should include schools that actively encourage student participation. Using a qualitative approach to better capture the complexity of the expected relationships would be highly beneficial.

Implications for educational practice

Despite its limitations, the study provides several suggestions for improving educational practices. The present study highlights that the more students experience a democratic school climate, the easier it is for them to master deliberative goals. The school culture may even (partially) compensate for the depriving context factors of students in urban schools. A logical consequence is that urban school teams should invest as much as possible in achieving a democratic school culture, (1) consolidating fair support so that students feel respected and valued by their teachers, (2) expanding opportunities for discussion so that students in a controlled and safe environment learn to deal with agreement and disagreement, to formulate arguments and to listen to each other, and (3) exploring opportunities for student participation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are collected and administered by GO! onderwijs van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, the umbrella organization of state schools in Flanders. The researchers, through a partnership with GO!, were given access to the dataset, committing to not further distributing the data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to https://g-o.be/actief-burgerschap/.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the researchers conduct a secondary analysis on an existing and anonymized dataset, which in accordance to local legislation does not require ethical review and approval, nor informed consent.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (grant number 1900822N).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AHOVOKS [Agentschap voor Hoger Onderwijs, Volwassenenonderwijs, Kwalificaties en Studietoelagen] (2017). Peiling burgerzin en burgerschapseducatie in de derde graad secundair onderwijs. Available at: https://publicaties.vlaanderen.be/view-file/24495

AHOVOKS (2021). “Onderwijsdoelen” in Agentschap voor Hoger Onderwijs, Volwassenenonderwijs, Kwalificaties en Studietoelagen Available at: https://www.onderwijsdoelen.be

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., and Furlong, M. J. (2008). Student engagement with school: critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol. Sch. 45, 369–386. doi: 10.1002/pits.20303

Benhabib, S. (1996). Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Biesta, G., Lawy, R., and Kelly, N. (2009). Understanding young people’s citizenship learning in everyday life: the role of contexts, relationships and dispositions. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Justice 4, 5–24. doi: 10.1177/1746197908099374

Brown, R., and Evans, W. P. (2002). Extracurricular activity and ethnicity: creating greater school connection among diverse student populations. Urban Educ. 37, 41–58. doi: 10.1177/0042085902371004

Castillo, J. C., Miranda, D., Bonhomme, M., Cox, C., and Bascopé, M. (2015). Mitigating the political participation gap from the school: the roles of civic knowledge and classroom climate. J. Youth Stud. 18, 16–35. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2014.933199

Castro, A. J., and Knowles, R. T. (2017). “Democratic citizenship education: research across multiple landscapes and contexts” in The Wiley Handbook of Social Studies Research. eds. M. M. Manfra and C. M. Bolick (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc), 287–318.

Chambers, S. (2003). Deliberative democratic theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 6, 307–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085538

de Groot, I., and Eidhof, B. (2019). Mock elections as a way to cultivate democratic development and a democratic school culture. Lond. Rev. Educ. 17, 362–382. doi: 10.18546/LRE.17.3.11

de Groot, I., and Lo, J. (2020). The democratic school experiences framework: a tool for the design and self-assessment of democratic experiences in formal education. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Justice 16, 211–226. doi: 10.1177/1746197920971810

de Groot, I., and Veugelers, W. (2016). Why we need to question the democratic engagement of adolescents in Europe. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 14, 27–38. doi: 10.2390/JSSE-V14-I4-1426

Dewey, J. (2001). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Dryzek, J. S. (2009). Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comp. Pol. Stud. 42, 1379–1402. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332129

Elstub, S. (2012). Towards a Deliberative and Associational Democracy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Englund, T. (2006). Deliberative communication: A pragmatist proposal. J. Curric. Stud. 38, 503–520. doi: 10.1080/00220270600670775

Englund, T. (2011). The potential of education for creating mutual trust: schools as sites for deliberation. Educ. Philos. Theory 43, 236–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00594.x

European Commission (Red.). (2017). Citizenship education at school in Europe: 2017; Eurydice report (Text completed in October 2017). Publications Office of the European Union.

Flanagan, C. A., Cumsille, P., Gill, S., and Gallay, L. S. (2007). School and community climates and civic commitments: patterns for ethnic minority and majority students. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 421–431. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.421

Flanagan, C. A., and Stout, M. (2010). Developmental patterns of social trust between early and late adolescence: age and school climate effects: developmental patterns of social trust. J. Res. Adolesc. 20, 748–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00658.x

Griffin, M. (2020). Developing deliberative minds–Piaget, Vygotsky and the deliberative democratic citizen. J. Deliberative Democracy 7. doi: 10.16997/jdd.113

Gutmann, A., and Thompson, D.. (2004). Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Hart, D., and Atkins, R. (2002). Civic competence in urban youth. Appl. Dev. Sci. 6, 227–236. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0604_10

Hoy, W. K. (1990). Organizational climate and culture: a conceptual analysis of the school workplace. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 1, 149–168. doi: 10.1207/s1532768xjepc0102_4

Janmaat, J. G. (2010). Classroom diversity and its relation to tolerance, trust and participation in England, Sweden and Germany. UK: Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies. Available at: http://www.llakes.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/W.-Classroom-Diversity-and-its-Relation-to-Tolerance-Trust-and-Participation-in-England-Sweden-and-Germany.pdf

Johnson, B., Down, B., le Cornu, R., Peters, J., Sullivan, A., Pearce, J., et al. (2015). “Introduction” in Early Career Teachers: Stories of Resilience. Springer, Singapore: Springer Briefs in Education. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-173-2_1

Jónsson, Ó. P., and Garces Rodriguez, A. (2021). Educating democracy: competences for a democratic culture. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Justice 16, 62–77. doi: 10.1177/1746197919886873

Karakos, H. L., Voight, A., Geller, J. D., Nixon, C. T., and Nation, M. (2016). Student civic participation and school climate: associations at multiple levels of the school ecology civic participation and school ecology. J. Community Psychol. 44, 166–181. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21748

Kavadias, D., Engels, N., Van Cappel, G., and Spruyt, B. (2022). “Debest en de Zinnekes” in Zinnekes zijn debest Diversiteit aan het werk bij Brusselse jongeren van vandaag (Brussels, Belgium: VUBPress), 185–196.

Keating, A., and Benton, T. (2013). Creating cohesive citizens in England? Exploring the role of diversity, deprivation and democratic climate at school. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Justice 8, 165–184. doi: 10.1177/1746197913483682

Kokkonen, A., Esaiasson, P., and Gilljam, M. (2010). Ethnic diversity and democratic citizenship: evidence from a social laboratory. Scand. Polit. Stud. 33, 331–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2010.00253.x

Lenzi, M., Vieno, A., Sharkey, J., Mayworm, A., Scacchi, L., Pastore, M., et al. (2014). How school can teach civic engagement besides civic education: the role of democratic school climate. Am. J. Community Psychol. 54, 251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9669-8

Lundy, L. (2018). In defence of tokenism? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decision-making. Childhood 25, 340–354. doi: 10.1177/0907568218777292

Mansoury, E., Kavadias, D., and Echeverria Vicente, N. J. (2022). “Exclusie en anti-systeemattitudes,” in Zinnekes zijn debest Diversiteit aan het werk bij Brusselse jongeren van vandaag. eds. D. Kavadias, B. Spruyt, N. Engels, and G. CappelVan Brussels, Belgium: VUBPress, 41–60.

Murray, T. (2013). Toward defining, justifying, measuring, and supporting social deliberative skills. AIED 2013 self-regulated learning workshop. Available at: http://socialdeliberativeskills.org/documents/AIED2013-MetacogWorkshopMurraySubm.pdf

Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., and Muhammad, R. S. (2013). “Organizational culture and climate” in Handbook of Psychology, Vol 12: Industrial and Organizational Psychology. eds. I. B. Weiner, N. W. Schmitt, and S. Highhouse (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons), 643–676.

Pažur, M., Domović, V., and Kovač, V. (2021). Democratic school culture and democratic school leadership. Croat. J. Educ. 22, 1137–1164. doi: 10.15516/cje.v22i4.4022

Prosser, J. (1999). “The evolution of school culture research” in School Culture. ed. J. Prosser (London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd), 1–14.

Rudasill, K. M., Snyder, K. E., Levinson, H., and Adelson, J. L. (2018). Systems view of school climate: a theoretical framework for research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 35–60. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9401-y

Sampermans, D. (2018). The democratic school climate: active citizenship at school. Faculteit Sociale Wetenschappen, Centrum voor Politicologie, KU Leuven. Available at: https://kuleuven.limo.libis.be/discovery/search?query=any,contains,lirias2363338&tab=LIRIAS&search_scope=lirias_profile&vid=32KUL_KUL:Lirias&foolmefull=1

Sampermans, D., Isac, M. M., and Claes, E. (2018). Can schools engage students? Multiple perspectives, multidimensional school climate research in England and Ireland. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 17, 13–28. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/JSSE-V17-I1-1675

Sampermans, D., Maurissen, L., Louw, G., Hooghe, M., and Claes, E. (2017). ICCS 2016 Rapport Vlaanderen. Available at: https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/international-civic-and-citizenship-education-study-iccs#Resultaten_ICCS_2016

Simó, N., Parareda, A., and Domingo, L. (2016). Towards a democratic school: the experience of secondary school pupils. Improv. Sch. 19, 181–196. doi: 10.1177/1365480216631080

Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., and Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 357–385. doi: 10.3102/0034654313483907

Veugelers, W., de Groot, I., and Stolk, V. (2017). Research for CULT committee. Teaching common values in Europe. Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies.

Vieno, A., Perkins, D. D., Smith, T. M., and Santinello, M. (2005). Democratic school climate and sense of community in school: a multilevel analysis. Am. J. Community Psychol. 36, 327–341. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8629-8

Voight, A. (2015). Student voice for school-climate improvement: a case study of an urban middle school: student voice for school climate improvement. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 310–326. doi: 10.1002/casp.2216

Voight, A., and Nation, M. (2016). Practices for improving secondary school climate: a systematic review of the research literature. Am. J. Community Psychol. 58, 174–191. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12074

Young, I. M. (1996). “Communication and the other: beyond deliberative democracy” in Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political. ed. S. Benhabib (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 120–136.

Keywords: urban education, secondary education, deliberative competences, democratic school culture, multilevel analysis

Citation: Strijbos J and Engels N (2023) Students’ development of deliberative competences: The contribution of democratic experiences in urban schools. Front. Educ. 8:1142987. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1142987

Edited by:

Anabel Corral-Granados, NTNU, NorwayReviewed by:

Maude Modimothebe Dikobe, University of Botswana, BotswanaCaroll Dewar Hermann, North West University, South Africa

Copyright © 2023 Strijbos and Engels. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jetske Strijbos, SmV0c2tlLlN0cmlqYm9zQHZ1Yi5iZQ==

Jetske Strijbos

Jetske Strijbos Nadine Engels

Nadine Engels