94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 09 March 2023

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1140587

Organizational commitment is a perennial concern. Numerous studies have been conducted to figure out how to strengthen the commitment of employees to the organization. Many of them examined the moderating factors that influence the link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. However, the majority of past research has focused on the private and corporate sectors. Further, some management personnel opt to quit the firm while still being content with their existing position. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the role of moderators in the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment by applying the purposive sampling method to conduct the data survey of 402 managers in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, who work in the public education sector. By using the PLS-SEM modeling approach with the help of SmartPLS 4 software to examine the research hypotheses, the results reveal that organizational commitment is positively affected by job satisfaction and work engagement. At the same time, managers with high person-organization fit and fun at work will have higher levels of organizational commitment in situations of high satisfaction in their jobs. Conversely, high role stress will dampen the levels of organizational commitment in situations of high job satisfaction. The results offered some managerial implications to strengthen the commitment to the organization of the managers in the educational sector. This research also stressed some limitations and suggested opportunities for future investigation.

In recent decades, organizations have grown increasingly people-focused. Human viewpoint has emerged as the primary differentiating feature of the job market. Due to the increasingly competitive labor market, executives have placed a great deal of emphasis on recruiting, keeping, and developing people, which has elevated the relevance of the human resources department (Islam and Ahmed, 2018; Srikanth, 2019). Thus, acquiring scarce talent will result in the creation of a value that is unusual, unreplicable, and difficult to replace. Particularly for the managerial level. When a manager quits a firm, it is also a pain for organizational leaders since it is tough to hire the proper and capable individuals. Therefore, numerous studies have been undertaken in an effort to strengthen the commitment of employees to the organization. Many variables have been investigated to determine their effect on organizational commitment. In which job satisfaction and work engagement are the most important factors. Human resource managers are now primarily tasked with maximizing employee job satisfaction (Ramlall, 2004; McKay et al., 2007). In Asian countries where the value of a productive workforce is now recognized, employee engagement must also be given significant consideration (Gupta, 2015).

According to previous studies, job satisfaction is defined as an emotional or demonstrative reaction to the job (Hirschfeld, 2000; Buitendach and De Witte, 2005). When employees are more satisfied with their employment and work culture, they are more likely to be better representations of the industry and exhibit more organizational commitment (Agho et al., 1992). Spector (1997) defined job satisfaction as an employee’s feelings and emotions towards his or her employment, as well as his or her attitude toward the many realities of the workplace. Job satisfaction is a key factor in any profession. Because its results will affect not only the commitment to the organization, but also reduce intention to quit. Besides, work engagement is an employee’s attachment to his or her job function. It is the physical, intellectual, and emotional connection to the act (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004). It serves as a measure of employee conduct and performance results. Furthermore, work engagement entails an individual’s emotional and intellectual attachment to his/her company, supervisors, and coworkers while doing his or her job. This point was supported in previous studies by Hughes and Rog (2008).

Besides job satisfaction and work engagement, organizations nowadays also investigate many other important factors. Recently, person–organization (P–O) fit has been studied to investigate the relationship between individuals and their organizations. P–O fit has several positive outcomes, including increased productivity, greater loyalty, organizational commitment, rich productivity, and less employee turnover. Workers are believed to have a positive connection with their colleagues and fit into their job. Consequently, P–O fit is often stated as the compatibility between personnel and the organizations (Kristof, 1996). In addition, P–O fit is often defined as the compatibility of an individual’s values, personality, and ambitions with those of the organization (Kristof, 1996; Netemeyer et al., 1997). Therefore, various studies have demonstrated that individual attitudes and behavior are substantially impacted by the similarity between the person and the organization in specific aspects (Astakhova, 2016; Islam et al., 2016). Additionally, modern leaders place a strong emphasis on making their employees happy at work. Fun is one of the favorable phenomena in the workplace that includes social activities, acknowledgment of personal achievements, social events, comedy, games entertainment, an opportunity for personal growth, joy, play, and funny nicknames (Ford et al., 2003; Grant et al., 2014). Fun at work is believed to increase employee satisfaction and make employees more committed to the organization. As Owler et al. (2010) stated, everyone will want to have fun at work and it has beneficial outcomes for staff members. Being enjoyable at work has far-reaching consequences on workers and businesses. Fun favorably influences workers’ job satisfaction, creativity, productivity, energy, dedication, and negatively impacts turnover, anxiety, absenteeism, as well as emotional exhaustion, and burnout (Tews et al., 2012). In contrast, role stress is another essential consideration. Role stress can be generated by conflicting expectations, which can lead to burnout and mental burnout (Byrne, 1994). In the education sector, these structures are proven to have a positive connection to job dissatisfaction and an increased inclination to leave teaching early (Cable and Judge, 1996; Richards et al., 2017). Thus the purpose of this study is to examine the moderating effect of role stress on the link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

At the present time, the world in general and Vietnam in particular have experienced the economic crisis left by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the COVID-19 outbreak, employees as well as managers try to keep their jobs. However, after COVID-19, many of them chose to leave the old organization to look for new opportunities for themselves. A manager’s resignation is a significant loss for the organization. Recruiting is made more difficult and costly as a result of the difficulty of finding a suitable manager who fits the organization’s needs and personality. At the same time, a lack of leadership will make some corporate procedures unstable, and this will damage the performance not only of the department, but it may also harm the entire organization. Therefore, the author finds that it is necessary to study the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment again, to better understand the internal organization of the organization at the present time. Moreover, many moderators were also included to examine their effect on the commitment to the organization. The findings of this study suggest management recommendations and practices for fostering the commitment of the managers.

Organizational commitment is a component that continues to be investigated. According to Meyer et al. (1993), this is the psychological state of an employee that characterizes their connection to their present company and influences their decision to remain a member of the organization. Members of the firm may choose to quit or remain in the organization. Allen and Meyer (1990) research presents a model for organizational commitment that includes three components: emotional commitment, normative commitment, and continuity commitment. Specifically, emotional commitment is the psychological and emotional connection that workers have with the business. Normative commitment is an ethical commitment that establishes an employee’s duty to remain with the organization for a certain length of time. The final component of the promise to continue is the employee’s compensation for costs connected with leaving the organization. According to Allen and Meyer (1990), an employee’s commitment to the organization serves as an emotional tie between the employee and the organization, therefore assisting the company in retaining its personnel. Feldman (2000) argues further that this is a psychological contract. In this contract, employees commit to long-term employment with the company in exchange for advancement chances, training opportunities, and job stability. In most recent studies, they described organizational commitment as an individual’s attachment and identification with an organization, which is driven by a belief in an agreement with the organization’s goals and values (Jehanzeb, 2020; Orgambidez and Benitez, 2021; Ha and Lee, 2022). In general, dedication results in mutually advantageous outcomes: greater performance, improved work performance, fewer employee absences, and lower employee turnover rate (Suliman and Al-Junaibi, 2010). In research of Meyer and Alien (1991), they concluded that individuals with a strong commitment will demonstrate more loyalty and will be committed to helping the firm achieve its objectives.

Locke (1976) described job satisfaction as a person’s emotional well-being as a result of their job appraisal or work experience. According to Ivancevich et al. (1997), job happiness is attributed to the degree of personal-organizational fit and career perspectives. Demonstrate their approach to their task. Further, job satisfaction is also defined as an individual’s evaluation and attitude towards their work and work environment, encompassing various factors such as pay, benefits, workload, co-workers, management, work-life balance, organizational culture, and leadership behavior (Davidescu et al., 2020; Inegbedion et al., 2020; Bellmann and Hübler, 2021; Tran, 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Job satisfaction is a crucial element for every firm. This is evident since this element has been examined for a very long period (Locke, 1976; Ivancevich et al., 1997) through the present (e.g., Bellmann and Hübler, 2021; Tran, 2021; Wu et al., 2021). The majority of these researches recognize the significance of Job Satisfaction. Moreover, research by Fu and Deshpande (2014) indicates that job satisfaction is growing in significance due to its high correlation with job performance. Similar studies such as (Yucel and Bektas, 2012; Tarigan and Ariani, 2015) corroborate the relationship between job satisfaction and mental health, physical health, productivity, work motivation, and other factors. Job satisfaction is essential to employee loyalty for every firm. The firms of today are cognizant of the fact that workers with a high level of job satisfaction will dedicate themselves to their jobs and display organizational loyalty. Frequently, these firms are able to keep their staff, therefore decreasing the expenses of recruiting, selection, and training. Additionally, previous research has demonstrated the influence of diverse viewpoints on work satisfaction on organizational behavioral outcomes, such as organizational commitment (Samad and Yusuf, 2012).

Personal traits can have a substantial effect on job satisfaction (Kinicki et al., 2002). According to Clark (1997), the variables associated with job satisfaction include gender, education level, and length of employment. However, Tett and Meyer (1993) contend that organizational commitment is more solid and requires more time to develop than work satisfaction. Many previous studies have investigated the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. For instance, Fabi et al. (2015) gathered data from 730 employees at various Canadian firms and figured out there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Further, research by Jehanzeb and Mohanty (2018) conducted in the telecom industry in Pakistan also gave the same result. Hence, the following hypothesis is therefore proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Job satisfaction has a positive effect on organizational commitment.

Work engagement is defined as a “positive and satisfactory mental state related to work, expressed in three dimensions: vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Gómez-Salgado et al., 2021). García-Sierra et al. (2016) described vigor as the will to put effort into the work; commitment as the passion for participation; absorption as the concentration and immersion in one’s job. Another recent study by Orgambidez and Benitez (2021) also showed work engagement as a positive, fulfilling, and vital state of mind in relation to one’s work, characterized by high levels of energy, dedication, and involvement. Multiple factors can influence work engagement, including job characteristics, professional assets (e.g., autonomy, professional practice, role, and identity), organizational climate (e.g., structural empowerment and leadership), personal assets (e.g., psychological, or relational skills), job assets (e.g., volume of work, interpersonal and social relations, organization of work and tasks, and environment; Keyko et al., 2016). Also, according to Schaufeli and Bakker (2004), work engagement is characterized by a high degree of concentration and positive energy. Work engagement generates attitudes about work, inspires individuals to work with vigor and energy, and drives them to take on new responsibilities as part of their occupations. When workers are active in the decision-making process, they are less likely to feel threatened by organizational change (Fenton-O’Creevy, 2001). This is because participation in the decision-making process makes future events more predictable. Recent research by Garg et al. (2018) indicates a positive correlation between work engagement and job satisfaction. In addition, research by Chan (2019) demonstrates that work engagement mediates the association between leadership style and job satisfaction. The following theory is therefore proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Work engagement is positively related to job satisfaction.

One of the qualities used to assess whether workers are genuinely involved with the business is the amount of devotion to it. According to the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Schaufeli, 2017), work engagement is a good psychological state associated with employee performance, profitability, and retention in the firm (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Numerous investigations have demonstrated an association between work and organizational dedication (Poon, 2014; Albrecht et al., 2015; Farid et al., 2019). A high level of concentration and involvement promotes performance and aids in achieving goals, while also fostering pleasant feelings in the workplace. Therefore, these pleasant encounters will strengthen employees’ emotional ties to their firm (Poon, 2014; Albrecht et al., 2015; Farid et al., 2019; Orgambidez and Benitez, 2021). Therefore, we suggest:

Hypothesis 3: Work engagement has a positive impact on organizational commitment.

Personal–organizational fit (henceforth P–O fit) refers to the compatibility between an individual’s personality and organizational traits (McCulloch and Turban, 2007). P–O fit is also described as the fit between an individual’s norms and values and those of an organization (Chatman, 1989). This justification highlights the significance of employee and organizational fit based on common values. P–O fit has a positive influence on several organizational outcomes, including organizational commitment, high production quality, and reduced staff turnover (Van Vianen, 2000; Alniaçik et al., 2013). P–O fit stresses the degree of congruence between individual and organizational values; it is also often known as organizational culture (Chatman, 1989). Numerous studies have demonstrated the significance of company culture and P–O fit. Hofstede’s (1984) previous work on culture can be considered as the foundational and most representative research for this issue. Hofstede’s (1984), utilizing a global sample, concluded that organizational cultures are frequently impacted by the surrounding society. Hofstede (1997) categorized companies regarding cultural elements as process/results-oriented, employee/job-focused, grassroots/professional level, open/closed systems, loose/tight controls, and standard/pragmatic procedures. Similarly, Cameron and Quinn (1999) offered a framework for four organizational cultures: ethnic, clan, market, and hierarchical, which may be characterized broadly as adaptable. Contrasted stability and control, and external attention against interior concentration and integration.

Having personal objectives and values that correspond with company goals and values decreases the desire to switch the firm. In their study, Wheeler et al. (2007) found a substantial association between P–O fit and job satisfaction. Also, there was a negative connection between P–O and revenue intent. According to Sekiguchi (2007), retaining employee engagement in a challenging corporate environment requires P–O fit. Furthermore, Holland’s job fit hypothesis proposes that employees are more joyful and productive when they feel a match between their personality and the characteristics of the organization (Holland, 1997). Elfenbein and O'Reilly III (2007) stated in their study that firms should pay greater attention to P–O matching since it encourages employee retention and dedication. Likewise, several researches have demonstrated a relationship between P–O fit and job satisfaction (Kim et al., 2013; Jung and Takeuchi, 2014). The research by Iplik et al. (2011) is a typical study indicating that P-O fit influences organizational commitment, work motivation, and job satisfaction positively. Other studies have also demonstrated a correlation between P–O fit and organizational commitment (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Tidwell, 2005; Chang et al., 2010). Moreover, the moderation effect of P–O fit is also tested in previous studies (Boon et al., 2011; Alniaçik et al., 2013). This study thus hypothesizes that P-O fit can considerably impact the link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment:

Hypothesis 4: P-O fit has a role to moderate the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Joy at the workplace is usually described as any social engagement, interpersonal contact, or job at work of fun or amusing type that brings pleasure, delight, or happiness to an individual. Tews et al. (2014) argued that workplace happiness has three sub-dimensions: (1) enjoyable activities, (2) social connection with coworkers, and (3) leadership support for creating pleasure. Recreational activities are diverse social and group activities conducted by organizations to improve employee enjoyment (Ford et al., 2003; Karl et al., 2005). Social interactions with coworkers are defined by politeness, sociability, and cordial connections (Chiaburu and Harrison, 2008); and leaders’ support for happiness refers to the degree to which management permits and encourages people to be happy at work (Tews et al., 2014). In addition, Chan (2010) has identified four characteristics of workplace pleasure based on sound theory: (1) employee-oriented workplace happiness; (2) manager-focused workplace joy, socially oriented workplace pleasure, and strategically focused workplace pleasure. In addition, a number of recent studies have examined positive work-related outcomes resulting from workplace pleasure, including job satisfaction (Choi et al., 2013; Chan and Mak, 2016), improved performance (Choi et al., 2013; Tews et al., 2013), engagement and constitutive cohesion (Becker and Tews, 2016), cohesion (Tews et al., 2015), team performance (Han et al., 2016), trust management (Chan and Mak, 2016), and reduced turnover (Tews et al., 2013, 2014).

Workplace pleasure activities promote employee satisfaction (Karl and Peluchette, 2006b; Tews et al., 2014). The research of Karl and Peluchette (2006a) stated that happy employees are more likely to be stimulated at work. Happiness is frequently supported as a technique to facilitate various desirable outcomes, such as greater work satisfaction and organizational commitment and decreased stress and intention to resign (Yerkes, 2007; Tews et al., 2015). In addition, scholarly research has begun to demonstrate the significance of job enjoyment. Several studies have shown that happiness has a positive effect on the attitudes and mental condition of employees, including job satisfaction, organizational dedication, commitment to the company, mood, and good emotions (Karl and Peluchette, 2006a,b; Karl et al., 2008). Tews et al. (2012) have also proven that enjoyment is connected with organizational attraction in recruiting and decreased desire to leave (Karl et al., 2008). In addition, current research indicates that the more satisfied employees are with their jobs, the more likely they are to remain engaged at work (Tang et al., 2017), and the higher their job satisfaction scores (Chan and Mak, 2016). The following theory is therefore proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Fun at work moderates the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Initiated by Kahn et al. (1964), it is believed that role stress is the primary source of employees’ employment dilemmas (Jackson and Schuler, 1985) and physical/mental health issues (Ganster and Schaubroeck, 1991). Specifically, role stress is divided into two categories: role conflict and role ambiguity (Tubre, 2000). Role conflict refers to irreconcilable expectations from numerous parties, whereas role ambiguity refers to a lack of understanding of how to efficiently fulfill one’s work responsibilities (Rizzo et al., 1970). To be more explicit about these characteristics, role ambiguity refers to the degree to which an employee is unclear about his or her job in the company and the activities that he or she must do at work (Jackson and Schuler, 1985). When workers of a company are unsure about their duties, for instance, they will not know what to anticipate, what to do, how to work, or with whom to work. On the other hand, role conflict refers to the extent to which an employee sees contradictory needs, requirements, or information (Jackson and Schuler, 1985). The fulfillment of certain standards may not satisfy the demands of others. An employee, for instance, may get the same assignment from many supervisors; nonetheless, the same task from each individual has various requirements and orientations.

Role stress is a regular occurrence in organizations and one of the most extensively researched causes. It may be characterized as a set of expectations, responsibilities, and obligations imposed on employees by those who can exert influence over them (leaders, superiors) and assist define their positions (Katz and Kahn, 1978). It has a negative impact on staff performance (Kahn et al., 1964), becomes a factor that decreases employee satisfaction, and has a significant impact on the performance of the company (Örtqvist and Wincent, 2006). Multiple studies have discovered that employees with high levels of role ambiguity and role conflict have lower levels of job engagement and organizational commitment than other employees (Han et al., 2015; Min et al., 2015; Wingreen et al., 2017; Breevaart and Bakker, 2018). In addition, Pecino et al. (2019) found that role stress is adversely associated with employee satisfaction and increases burnout, negatively impacting employees. The author suggests two theories based on the reasoning and facts presented above (Figure 1):

Hypothesis 6: Role ambiguity has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 7: Role conflict has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

The measurement items in this study are all adopted from previous studies. First, we adopted six items to measure Organizational Commitment: “I would be delighted to spend the remainder of my job with my organization.” (OC1); “I feel as if the troubles of my organization are my mine.” (OC2); “I feel like a family member inside my organization.” (OC3); “I have an emotional connection to my organization.” (OC4); “My organization has a lot of personal significance for me.” (OC5); “My feeling of belonging to my company is strong.” (OC6; Potipiroon and Ford, 2017). Second, we adopted a three-item scale to measure Job Satisfaction, including “I am pretty content with my present job.” (JS1); “I am typically excited about my job.” (JS2); and “I get tremendous delight in my job “(JS3; Potipiroon and Ford, 2017). Third, we used eight items to evaluate Work Engagement, such as “I am bursting with enthusiasm at work.” (WE1); “I experience vitality and strength while doing my duties.” (WE2); “I am motivated by my work.” (WE3); “When I get up in the morning, I have the desire to go to work.” (WE4); “When I am working diligently, I am content.” (WE5); “I am pleased with the job I do.” (WE6); “I often lose track of time at work.” (WE7); “I am fully engaged in my task.” (WE8; Chan, 2019). Fourth, we adopted three items to measure P-O fit such as “I believe that my principles are relevant to the firm and its current workers.” (PO1); “My ideals correspond with those of the organization’s present personnel.” (PO2); and “This organization’s values and ‘personality’ mirror my own.” (PO3; Cable and Judge, 1996; Jehanzeb and Mohanty, 2018). Fifth, Fun at work was measured using three items, including “This is an enjoyable workplace.” (FAW1); “I smile often at work.” (FAW2); “Occasionally, I feel as if I’m playing rather than working.” (FAW3; Chan, 2019). Sixth, Role Ambiguity was assessed by using a six-item scale, such as “I am uncertain about the extent of my authority.” (RA1); “My job lacks clearly defined goals and plans.” (RA2); “I do not know if I have allocated my time well.” (RA3); “I am unsure about my responsibilities.” (RA4); “I’m uncertain of what others expect of me.” (RA5); “The tasks I must perform are not well stated.” (RA6; Rizzo et al., 1970). Finally, Role Conflict was adopted by using a five-item scale, such as “I am required to perform tasks that need to be carried out differently.” (RC1); “I work with two or more groups whose operations are notably dissimilar.” (RC2); “Two or more individuals have made irreconcilable demands.” (RC3); “I engage in issues that are likely to be acceptable by some but rejected by others.” (RC4); and “I am engaged in pointless activities.” (RC5; Rizzo et al., 1970).

The study targeted public universities, which included Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNUHCM) and its members as University of Technology (UT), University of Science (US), University of Social Sciences and Humanities (USSH), International University (IU), University of Information Technology (UIT), University of Economics and Law (UEL), and An Giang University (AGU). The data collection period was within the academic year 2021/2022, from May 2022 to September 2022. The purposive sampling approach was utilized for this study. To get the most accurate results, the authors sent out paper-based surveys directly to respondents. However, some managers were hard to reach in person. Therefore, the questionnaires were also distributed online and were sent only to those targets through email exchange.

The study employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine hypotheses. Normally, SEM is one of the best methods for evaluating the cause-and-effect relationships that involve multiple equations. Furthermore, the Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) is applied in this study. This is the method that is suitable for examining a complex model with multiple contemporaneous linkages. In several social sciences, including business research, marketing, and economic management, the PLS-SEM is undergoing substantial development. Given the intricacy of the model and the paucity of well-established literature, PLS-SEM is an appropriate choice (Peng and Lai, 2012). Furthermore, because certain social science research lacks distributional assumptions, it is evidently beneficial to use PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). As shown in Table 1, the assumption of multivariate normality is not satisfied, and the traditional covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) may not provide accurate results. Hence partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is a useful solution. Unlike CB-SEM, PLS-SEM does not rely on the assumption of multivariate normality and is more robust to non-normally distributed data. PLS-SEM has been shown to provide accurate results even when the data does not meet the assumption of multivariate normality, making it a valuable tool for data analysis in such situations (Henseler et al., 2015). In particular, PLS-SEM can be used to analyze data with skewed distributions, outliers, or variables that are not independently and identically normally distributed (Hair et al., 2010). Additionally, this study used SmartPLS 4, which is software that supports PLS-SEM method, to examine the relationships between variables. The introduction of SmartPLS 4 also contributes to making it easier to test the effect of moderator variables.

This study was carried out in the public sector, specializing in the education industry. The author tried to reach high-level employees at the Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City. Five hundred and four questionnaires were distributed. Some of the respondents were hard to reach due to their positions. By our best effort, 402 questionnaires were collected as official data and were used for analysis (79.6% response rate). 67.96 percent of the responders are male, while 32.04 percent are female. Of all the respondents, 289 managers (56.44 percent) are Deputy heads of the Department, while 223 (43.56 percent) are Heads of the Department. It is important to note that non-response bias is a potential concern in any survey research and can impact the validity of the results (Couper, 2000). To mitigate this, comparisons between the characteristics of the respondents and non-respondents were conducted, including gender, age, and position. The results showed no significant differences between the two groups, suggesting that non-response bias did not significantly impact the study results.

The authors evaluated the structural analysis with a variety of tests. First, Cronbach’s alpha is calculated for each construct; the values are all greater than 0.7, indicating the construct’s dependability. Every single composite dependability of the variables is likewise more than 0.7, indicating a high level of internal consistency (Hair et al., 2010). For convergent validity, which assesses if the latent components are well represented by their observable variables, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) must be larger than 0.50. As shown in Table 2, all AVEs surpass the threshold, confirming the convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010) and suggesting that each construct explains at least 50 % of the variance of the items comprising the construct. In addition, all variables have outer loadings greater than 0.7, matching the theoretical condition and enhancing the dependability of the scale (Henseler et al., 2012).

Cross-loadings are used to examine the statistical difference between the two constructs for discriminant validity. All components inside a structure should have outer loadings larger than cross-loadings with another structure (Hair et al., 2021). All cross-loading values satisfy this criterion’s constraints. According to the Fornell-Larcker condition, the square root of the AVE of a variable must be more than the highest correlation coefficient of the variable with other variables, or the AVE must be greater than the square of the highest correlation coefficient (Hair et al., 2010). In Table 3’s results, all measurements meet this condition.

Heterotrait–Monotrait ratios (HTMT) were used to evaluate discriminant validity, the mean score among all item correlations across components in comparison to the mean of the average correlations for items used to measure the same component. Using the HTMT as criterion, it is recommended to compare data to a 0.85 threshold (Kline, 2011). There is a loss of discriminant validity if the HTMT value exceeds this level. As shown in Table 4, all the indices are less than 0.85, hence the discriminant validity of this model is well-established.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to assess the presence of multicollinearity and common method bias. According to Kock (2015), a VIF value higher than 3.3 shows problematic multicollinearity and a potential indication of common method bias in a model. As shown in Table 5, it can be concluded that there is no significant risk of common method bias in the current research. The VIF values for all factors in the model are lower than 3.3, which is considered an acceptable threshold for multicollinearity. This suggests that the variables included in the model are not highly correlated, and there is no evidence of systematic measurement error or bias in the data. This, in turn, increases the confidence in the validity of the results and the conclusions drawn from the study.

To assess the data, normality, skewness, and kurtosis were used. The results of skewness and kurtosis indicate the distribution shape of the variables. According to Hair et al. (2010), data can be considered normal if the skewness falls within the range of −2 to +2 and the kurtosis falls within the range of −7 to +7. For the multivariate skewness and kurtosis, the skewness should fall between −1 and + 1, and the kurtosis should fall between −20 and + 20 (Mardia, 1970). As shown in Table 1, both skewness and kurtosis satisfied the criteria. However, when applying Mardia’s multivariate skewness and kurtosis, the results show that the skewness is more significant than 1 (b = 5.975564), and the kurtosis is larger than 20 (b = 57.943539). This deviation from the expected values suggests that the variables may not be independently and identically normally distributed, which is a requirement for multivariate normality. This result indicates that the data may not meet the assumption of multivariate normality. Also, this is one crucial criterion why PLS-SEM is useful in this situation, as it does not rely on this assumption (Hair et al., 2021).

Testing hypotheses assessed the importance of the relationship. All hypotheses are accepted because their value of ps are less than 0.05. Firstly, the study shows that JS has a positive effect on OC (β = 0.751, p = 0.000). Therefore, H1 is accepted. Secondly, WE also has a positive impact on JS (β = 0.484, p = 0.000). Thus, H2 is accepted. Furthermore, the result reveals that WE affects OC positively (β = 0.584, p = 0.000). Hence, H3 is supported.

To evaluate the influence of the moderators, we employ not only the coefficient and value of p, but also the Simple Slope Analysis method. Figure 2 revealed that the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment is stronger when an employee has a higher degree of P–O fit, and weaker when an employee has a lower degree of P–O fit, which confirms the findings of earlier research (Alniaçik et al., 2013; Jehanzeb and Mohanty, 2018). Further, the interaction is also significant (β = 0.153, p = 0.000). Hence, H4 is supported.

Figure 3 revealed a significant moderating role of fun at work on the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The plot illustrates a steeper and positive gradient for the high level of fun at work compared to the low level of fun at work. Consequently, this stated that the impact of job satisfaction on organizational commitment is stronger when employees perceive a higher level of fun at work as compared to others who perceive a lower level of fun at work. The interaction effect is also meaningful (β = 0.171, p = 0.000). Thus, H5 is accepted.

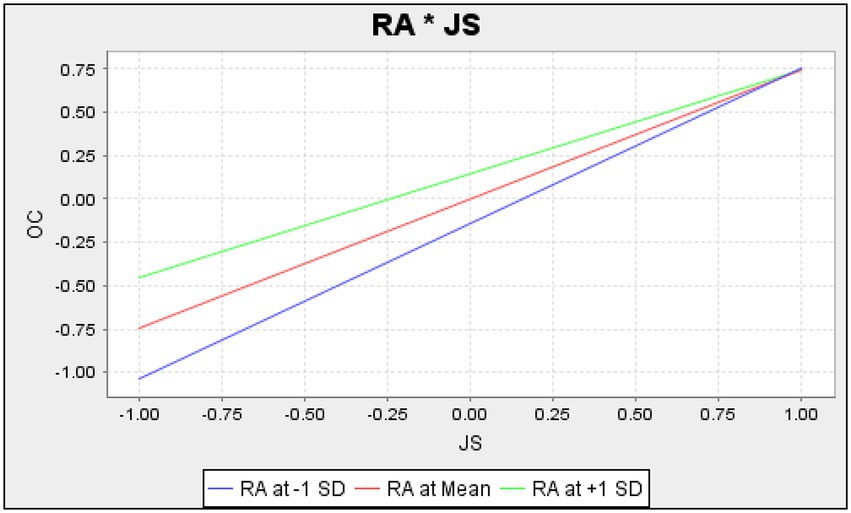

To illustrate the findings about role ambiguity, the sample is divided into low and high groups of role ambiguity, which can be seen in Figure 4. From Figure 4, it is evident that for high role ambiguity group, the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment is weaker. In contrast, this relationship is stronger for the low role ambiguity group, which has a steeper slope as compared to the high group. Besides, this interaction effect is significant (β = −0.148, p = 0.000). Therefore, we can conclude that H6 is accepted.

Figure 4. Moderation effect of role ambiguity between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

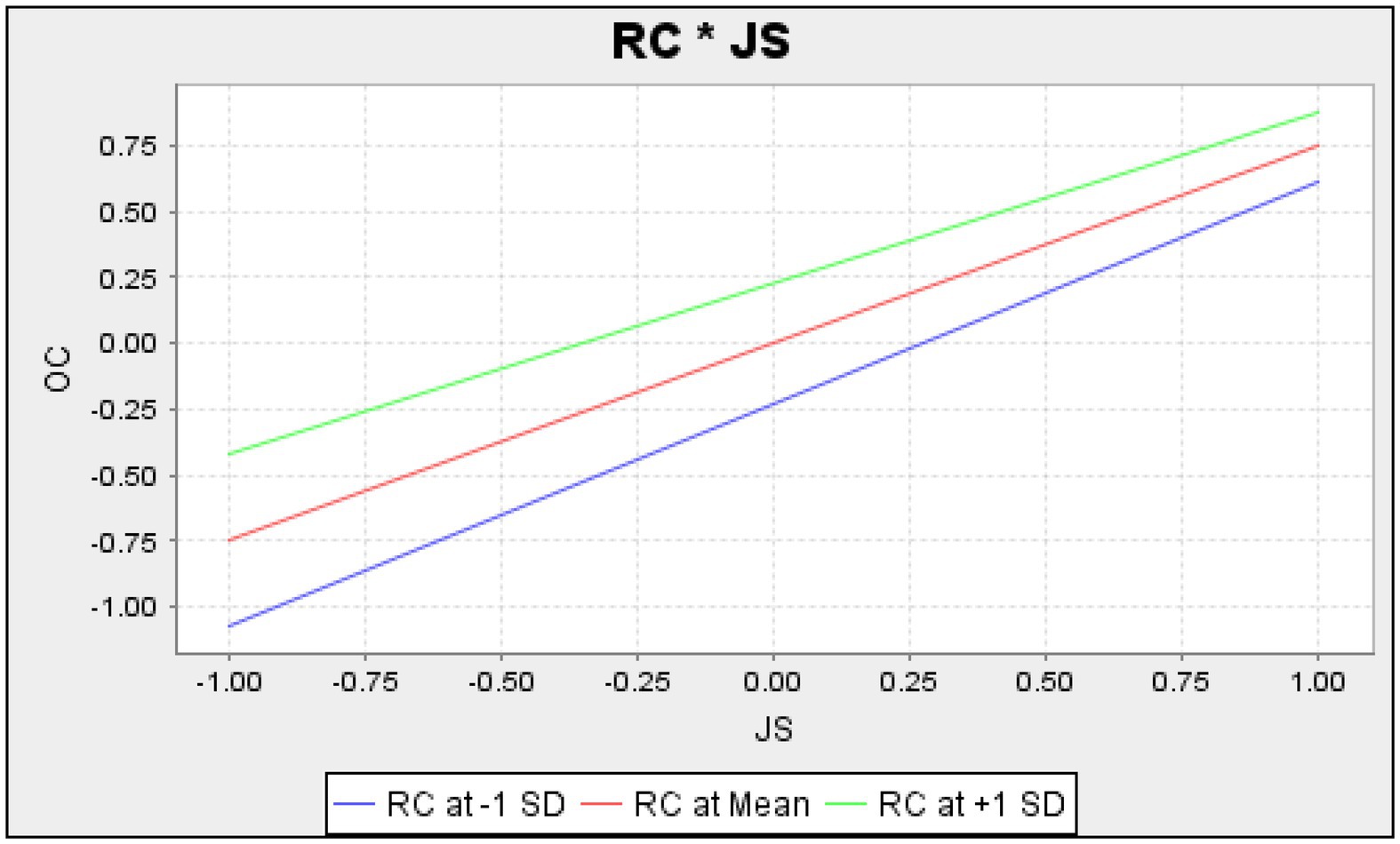

Last but not least, Figure 5 shows the impact of two groups of low and high role conflict (one SD below and one SD above the mean). As predicted, when the role conflict is high, the impact of job satisfaction on organizational commitment is weaker as compared to the lower role conflict. This can be seen from the figure below, where the low role conflict group has a steeper slope. The interaction effect is also accepted (β = −0.097, p = 0.002 < 0.05). Thus, H7 is supported (Table 6).

Figure 5. Moderation effect of role conflict between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

First of all, this study reveals that work engagement has a direct impact on job satisfaction, which is in line with previous studies (Yeh, 2013; Garg et al., 2018; Chan, 2019). This research demonstrates that workers who are actively involved in their work are more likely to experience a higher level of job satisfaction. Further, work engagement also positively impacts organizational commitment, which is consistent with previous findings (Poon, 2014; Albrecht et al., 2015; Farid et al., 2019). This indicates that when workers have good feelings and are excited and passionate about their present work, they will demonstrate job satisfaction and be more loyal to the organization. This research adds to the existing literature on the relationship between work engagement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. The findings suggest that work engagement is a critical factor influencing job satisfaction and organizational commitment, which contributes to a better understanding of the interplay between these variables. Also, for organizations, the results highlight the importance of fostering work engagement among employees to promote job satisfaction and enhance organizational commitment. By creating a work environment that promotes employee engagement, organizations can benefit from higher levels of employee satisfaction and loyalty, which can lead to reduced turnover, increased productivity, and improved organizational performance (Albrecht et al., 2015).

Moreover, job satisfaction is shown to have a positive connection with organizational commitment, consistent with other findings (Fabi et al., 2015; Jehanzeb and Mohanty, 2018). It can be said that Job satisfaction is still a very important factor for any company or organization. A satisfied employee is less likely to leave the current organization. Instead, they will choose to stay devoted to their company. Because the organization provides them with all the amenities and benefits they need. Leaving the organization now to join the new organization will become riskier. They may not enjoy the comfort and full benefits of their old organization. Therefore, this finding adds to the growing body of literature on the role of job satisfaction in shaping employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward their organizations. It further supports the importance of job satisfaction as a critical antecedent of organizational commitment, as employees who are satisfied with their jobs are more likely to be committed to the organization. From a practical perspective, organizations can develop strategies to enhance job satisfaction and improve employee retention by understanding the importance of job satisfaction in shaping employee behavior. Specifically, organizations can focus on creating a supportive work environment that provides employees with the amenities and benefits they need to feel satisfied with their jobs. This can include flexible work arrangements, opportunities for professional development, and a supportive and inclusive culture. Additionally, the results suggest that companies and organizations should prioritize developing programs and policies that support employee development and promote job satisfaction. This can include initiatives such as providing opportunities for skill-building and training, offering career advancement opportunities, and promoting work-life balance.

Besides, this study explains the substantial moderating effect of P–O Fit on the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The findings reveal that managers who believe their values align with those of present employees and the organization are more likely to have a stronger commitment to that organization, assuming job satisfaction. Simultaneously with that, the ones who enjoy having fun at work also have a stronger commitment. Therefore, we suggest that the organizations should focus on employing people that are a good match for the organization. These staff will likely be more committed to their jobs. They are hence more devoted to the company. By listening to employees’ thoughts and embracing adjustments, organizations may also consider modifying their environment and style to be more fit for their present workforce. Further, organizations should also encourage fun activities with staff, such as creating friendly activities, sports days/game days, and happy hours. This will make the staff more satisfied in the office, thus increasing their level of commitment.

In contrast, managers who experience more role stress are more likely to have a weaker commitment to the organization. These results contribute to a growing body of literature highlighting the negative impact of role stress on organizational commitment (e.g., Wingreen et al., 2017; Breevaart and Bakker, 2018). By highlighting the role of role ambiguity and conflict in exacerbating role stress and diminishing commitment, the study sheds light on how managers can be effectively managed and supported in the workplace. In reality, role conflicts can arise when managers are responsible for procedures involving many divisions. It is possible for these departments to have distinct working styles or internal disagreements. They cause processes to stagnate, so directly affecting the management and resulting in stress for the manager. In addition, the manager may get the task from a manager of a higher rank. Sometimes this task is expected to be done differently by another senior manager. This makes it difficult for the task receiver to discern the direction of the work, hence decreasing job satisfaction and perhaps leading to burnout. Moreover, Vietnam’s educational system is highly dynamic. Some schools use innovative instructional techniques and curricula. So that the faculty structure has to change, and additional instructors are required. However, the fact that recruitment is difficult. In the lack of human resources, the management is sometimes held accountable. Therefore, we suggest that, in order to limit role ambiguity as well as role conflict, internal conflicts should be resolved as soon as possible. Besides, processes and tasks should be defined and clarified from the beginning. From there, the recipients of the task will have a more accurate view of what they will do, and whom they will work with. This will make the processes and tasks more convenient; and not only help create results for the company, but also increase satisfaction, which in turn increases commitment to the organization. Additionally, organizations may benefit from investing in professional development opportunities for their managers to help them better cope with role stress and perform at their best.

In conclusion, this study enriches the knowledge of organizational commitment by examining various moderators on the linkage between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In order to retain managers, the firm must focus on carefully choosing individuals with P-O fit and fostering an environment where people can have fun while working. Organizations should also pay attention to factors that cause role stress to avoid burnout. Consequently, minimizing undesirable staff leaving. The findings give evidence in favor of the theories derived from earlier research. Consequently, the management implications and recommendations will not be confined to the educational sector but will be applicable to any public sector company.

In addition to its shortcomings, this study also suggests avenues for further research. First, because this study is based on self-reported data, respondents’ bias is unavoidable. Consequently, future research should analyze aspects based on the various viewpoints of respondents. Second, this investigation involves spatial and temporal constraints. In terms of timing, the study’s data were obtained not long after Vietnam had recently defeated the Covid-19 outbreak. After the situation in Vietnam and the globe as a whole return to normal, the outcomes might be different. The author believes that the outcomes of this study have limited short-term relevance. Future research can be undertaken over a longer period of time to get more precise results. Further, due to the fact that the data is only collected within the National University of Ho Chi Minh City, the results of the study cannot be fully representative of the education industry. Subsequent research may expand the study’s scope, and it may be preferable to examine more than one nation to get the most comprehensive conclusion. Finally, no control variables were included in the model. Nonetheless, the author predicts that control variables such as age, salary, and health will influence the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Future research should explore incorporating these variables within its study model.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

TH conceived the research topic, outlined the research design, collected the data, and wrote the initial drafts of the article. TB supervised the whole process of the preparation of the article, read and commented on the manuscript several times. PN revised the article and submitted the manuscript to the journal. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the International University, Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under Grant number SV2022-PM-01.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agho, A. O., Price, J. L., and Mueller, C. W. (1992). Discriminant validity of measures of job satisfaction, positive affectivity, and negative affectivity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 65, 185–195. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1992.tb00496.x

Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., and Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: an integrated approach. J. Organ. Eff. 2, 7–35. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042

Allen, N. J., and Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 63, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

Alniaçik, E., Alniaçik, Ü., Erat, S., and Akçin, K. (2013). Does person-organization fit moderate the effects of affective commitment and job satisfaction on turnover intentions? Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 99, 274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.495

Astakhova, M. N. (2016). Explaining the effects of perceived person-supervisor fit and person-organization fit on organizational commitment in the U.S. and Japan. J. Bus. Res. 69, 956–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.039

Becker, F. W., and Tews, M. J. (2016). Fun activities at work: do they matter to hospitality employees? J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 15, 279–296. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2016.1147938

Bellmann, L., and Hüble, O. (2021). Working from home, job satisfaction, and work–life balance–robust or heterogeneous links? Int. J. Manpower, 42, 424–441. doi: 10.1108/IJM-10-2019-0458

Boon, C., Den Hartog, D. N., Boselie, P., and Paauwe, J. (2011). The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: examining the role of person–organisation and person–job fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 22, 138–162. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.538978

Breevaart, K., and Bakker, A. B. (2018). Daily job demands and employee work engagement: the role of daily transformational leadership behavior. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 23, 338–349. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000082

Buitendach, J. H., and De Witte, H. (2005). Job insecurity, extrinsic and intrinsic job satisfaction and affective organisational commitment of maintenance workers in a parastatal. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 36, 27–38. doi: 10.4102/sajbm.v36i2.625

Byrne, B. M. (1994). Burnout: testing for the validity, replication, and invariance of causal structure across elementary, intermediate, and secondary teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 31, 645–673. doi: 10.3102/00028312031003645

Cable, D. M., and Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 67, 294–311. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1996.0081

Cameron, K. S., and Quinn, R. E. (1999). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Frame Work. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Chan, S. C. (2010). Does workplace fun matter? Developing a useable typology of workplace fun in a qualitative study. Int. J. Hospitality Manag., 29, 720–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.03.001

Chan, S. C. H. (2019). Participative leadership and job satisfaction: the mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of fun experienced at work. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 40, 319–333. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-06-2018-0215

Chan, S. C. H., and Mak, W. M. (2016). Have you experienced fun in the workplace? An empirical study of workplace fun, trust-in-management, and job satisfaction. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 7, 27–38. doi: 10.1108/JCHRM-03-2016-0002

Chang, H. T., Chi, N. W., and Chuang, A. (2010). Exploring the moderating roles of perceived person–job fit and person–organisation fit on the relationship between training investment and knowledge workers' turnover intentions. Appl. Psychol. 59, 566–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00412.x

Chatman, J. A. (1989). Improving interactional organizational research: a model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 333–349. doi: 10.2307/258171

Chiaburu, D. S., and Harrison, D. A. (2008). Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 1082–1103. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1082

Choi, Y. G., Kwon, J., and Kim, W. (2013). Effects of attitudes vs experience of workplace fun on employee behaviors: focused on generation Y in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 25, 410–427. doi: 10.1108/09596111311311044

Clark, A. E. (1997). Job satisfaction and gender: why are women so happy at work? Labour Econ. 4, 341–372. doi: 10.1016/S0927-5371(97)00010-9

Couper, M. P. (2000). Web surveys: a review of issues and approaches. Public Opin. Q. 64, 464–494. doi: 10.1086/318641

Davidescu, A. A., Apostu, S. A., Paul, A., and Casuneanu, I. (2020). Work flexibility, job satisfaction, and job performance among Romanian employees—Implications for sustainable human resource management. Sustainability, 12:6086. doi: 10.3390/su12156086

Elfenbein, H. A., and O'Reilly, C. A. III (2007). Fitting in: the effects of relational demography and person-culture fit on group process and performance. Group Org. Manag. 32, 109–142. doi: 10.1177/1059601106286882

Fabi, B., Lacoursière, R., and Raymond, L. (2015). Impact of high-performance work systems on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention to quit in Canadian organizations. Int. J. Manpow. 36, 772–790. doi: 10.1108/IJM-01-2014-0005

Farid, T., Iqbal, S., Ma, J., Castro-González, S., Khattak, A., and Khan, M. K. (2019). Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating effects of organizational justice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:1731. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101731

Feldman, D. C. (2000). The Dilbert syndrome: how employee cynicism about ineffective management is changing the nature of careers in organizations. Am. Behav. Sci. 43, 1286–1300. doi: 10.1177/00027640021955865

Fenton-O’Creevy, M. (2001). Employee involvement and the middle manager: saboteur or scapegoat? Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 11, 24–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2001.tb00030.x

Ford, R. C., McLaughlin, F. S., and Newstrom, J. W. (2003). Questions and answers about fun at work. Hum. Resour. Plan. 26, 18–33.

Fu, W., and Deshpande, S. P. (2014). The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a China’s insurance company. J. Bus. Ethics 124, 339–349. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1876-y

Ganster, D. C., and Schaubroeck, J. (1991). Work stress and employee health. J. Manag. 17, 235–271. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700202

García-Sierra, R., Fernández-Castro, J., and Martínez-Zaragoza, F. (2016). Work engagement in nursing: an integrative review of the literature. J. Nurs. Manag. 24, E101–E111. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12312

Garg, K., Dar, I. A., and Mishra, M. (2018). Job satisfaction and work engagement: a study using private sector bank managers. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 20, 58–71. doi: 10.1177/1523422317742987

Gómez-Salgado, J., Domínguez-Salas, S., Romero-Martín, M., Romero, A., Coronado-Vázquez, V., and Ruiz-Frutos, C. (2021). Work engagement and psychological distress of health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 29, 1016–1025. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13239

Grant, A. M., Berg, J. M., and Cable, D. M. (2014). Job titles as identity badges: how self-reflective titles can reduce emotional exhaustion. Acad. Manag. J. 57, 1201–1225. doi: 10.5465/amj.2012.0338

Gupta, M. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, employee–company identification, and organizational commitment: mediation by employee engagement. Curr. Psychol. 36, 101–109. doi: 10.1007/s12144-015-9389-8

Ha, J. C., and Lee, J. W. (2022). Realization of a sustainable high-performance organization through procedural justice: the dual mediating role of organizational trust and organizational commitment. Sustainability 14:1259. doi: 10.3390/su14031259

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. Y. A., Anderson, R., and Tatham, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Glob. Perspect. 14, 274–286.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2021). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Han, S. S., Han, J. W., An, Y. S., and Lim, S. H. (2015). Effects of role stress on nurses' turnover intentions: the mediating effects of organizational commitment and burnout. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 12, 287–296. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12067

Han, H., Kim, W., and Jeong, C. (2016). Workplace fun for better team performance: focus on frontline hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 28, 1391–1416. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2014-0555

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2012). “Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: basic concepts and recent issues” in Handbook of Research on International Advertising. ed. S. Okazaki (Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar), 252–276.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hirschfeld, R. R. (2000). Does revising the intrinsic and extrinsic subscales of the Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire short form make a difference? Educ. Psychol. Meas. 60, 255–270. doi: 10.1177/00131640021970493

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values. California: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. (1997). The Archimedes Effect. Working at the Interface of Cultures: 18 Lives in Social Science. London, Routledge. pp. 47–61.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments (3rd). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Hughes, J. C., and Rog, E. (2008). Talent management: a strategy for improving employee recruitment, retention and engagement within hospitality organizations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 20, 743–757. doi: 10.1108/09596110810899086

Inegbedion, H., Inegbedio, E., Pete, A., and Harry, L. (2020). Perception of workload balance and employee job satisfaction in work organisations. Heliyon, 6:e03160. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03160

Iplik, F. N., Kilic, K. C., and Yalcin, A. (2011). The simultaneous effects of person-organization and person-job fit on Turkish hotel managers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 23, 644–661. doi: 10.1108/09596111111143386

Islam, T., and Ahmed, I. (2018). Mechanism between perceived organizational support and transfer of training: explanatory role of self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Manag. Res. Rev. 41, 296–313. doi: 10.1108/MRR-02-2017-0052

Islam, T., Khan, M. M., and Bukhari, F. H. (2016). The role of organizational learning culture and psychological empowerment in reducing turnover intention and enhancing citizenship behavior. Learn. Org. 23, 156–169. doi: 10.1108/TLO-10-2015-0057

Ivancevich, J., Olelans, M., and Matterson, M. (1997). Organizational Behavior and Management. Sydney: Irwin.

Jackson, S. E., and Schuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 36, 16–78. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(85)90020-2

Jehanzeb, K. (2020). Does perceived organizational support and employee development influence organizational citizenship behavior? Person–organization fit as moderator. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 44, 637–657. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-02-2020-0032

Jehanzeb, K., and Mohanty, J. (2018). Impact of employee development on job satisfaction and organizational commitment: person–organization fit as moderator. Int. J. Train. Dev. 22, 171–191. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12127

Jung, Y., and Takeuchi, N. (2014). Relationships among leader–member exchange, person–organization fit and work attitudes in Japanese and Korean organizations: testing a cross-cultural moderating effect. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 25, 23–46. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.778163

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.2307/256287

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., and Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational Stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity. New York, NY: Wiley.

Karl, K., and Peluchette, J. (2006a). How does workplace fun impact employee perceptions of customer service quality? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 13, 2–13. doi: 10.1177/10717919070130020201

Karl, K. A., and Peluchette, J. V. (2006b). Does workplace fun buffer the impact of emotional exhaustion on job dissatisfaction? A study of health care workers. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 7, 128–142. doi: 10.21818/001c.16553

Karl, K. A., Peluchette, J. V., and Hall, L. M. (2008). Give them something to smile about: a marketing strategy for recruiting and retaining volunteers. J. Nonprofit Publ. Sect. Market. 20, 71–96. doi: 10.1080/10495140802165360

Karl, K., Peluchette, J., Hall-Indiana, L., and Harland, L. (2005). Attitudes toward workplace fun: a three sector comparison. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 12, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/107179190501200201

Keyko, K., Cummings, G. G., Yonge, O., and Wong, C. A. (2016). Work engagement in professional nursing practice: a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 61, 142–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.06.003

Kim, T. Y., Aryee, S., Loi, R., and Kim, S. P. (2013). Person–organization fit and employee outcomes: test of a social exchange model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24, 3719–3737. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.781522

Kinicki, A. J., McKee-Ryan, F. M., Schriesheim, C. A., and Carson, K. P. (2002). Assessing the construct validity of the job descriptive index: a review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 14–32. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.14

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collaboration (IJEC) 11, 1–10. doi: 10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 49, 1–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., and Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences OF INDIVIDUALS'FIT at work: a meta-analysis OF person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 58, 281–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika 57, 519–530. doi: 10.1093/biomet/57.3.519

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., and Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77, 11–37. doi: 10.1348/096317904322915892

McCulloch, M. C., and Turban, D. B. (2007). Using person–organization fit to select employees for high-turnover jobs. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 15, 63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2007.00368.x

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Tonidandel, S., Morris, M. A., Hernandez, M., and Hebl, M. R. (2007). Racial differences in employee retention: are diversity climate perceptions the key? Pers. Psychol. 60, 35–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00064.x

Meyer, J. P., and Alien, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1, 61–89. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Min, H., Kim, H. J., and Lee, S. B. (2015). Extending the challenge–hindrance stressor framework: the role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 50, 105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.006

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., McKee, D. O., and McMurrian, R. (1997). An investigation into the antecedents of organizational citizenship behaviors in a personal selling context. J. Mark. 61, 85–98. doi: 10.1177/002224299706100306

Orgambidez, A., and Benitez, M. (2021). Understanding the link between work engagement and affective organisational commitment: the moderating effect of role stress. Int. J. Psychol. 56, 791–800. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12741

Örtqvist, D., and Wincent, J. (2006). Prominent consequences of role stress: a meta-analytic review. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 13, 399–422. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.399

Owler, K., Morrison, R., and Plester, B. (2010). Does fun work? The complexity of promoting fun at work. J. Manag. Organ. 16, 338–352. doi: 10.5172/jmo.16.3.338

Pecino, V., Mañas, M. A., Díaz-Fúnez, P. A., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Padilla-Góngora, D., and López-Liria, R. (2019). Organisational climate, role stress, and public employees’ job satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1792–1804. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101792

Peng, D. X., and Lai, F. (2012). Using partial least squares in operations management research: a practical guideline and summary of past research. J. Oper. Manag. 30, 467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2012.06.002

Poon, J. M. L. (2014). Relationships among perceived career support, affective commitment, and work engagement. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 1148–1155. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2013.768768

Potipiroon, W., and Ford, M. T. (2017). Does public service motivation always Lead to organizational commitment? Examining the moderating roles of intrinsic motivation and ethical leadership. Public Pers. Manag. 46, 211–238. doi: 10.1177/0091026017717241

Ramlall, S. (2004). A review of employee motivation theories and their implications for employee retention within organizations. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 5, 52–63.

Richards, K. A. R., Washburn, N., Carson, R. L., and Hemphill, M. A. (2017). A 30-year scoping review of the physical education teacher satisfaction literature. Quest 69, 494–514. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2017.1296365

Rizzo, J. R., House, R. J., and Lirtzman, S. I. (1970). Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 15, 150–163. doi: 10.2307/2391486

Samad, S., and Yusuf, S. Y. M. (2012). The role of organizational commitment in mediating the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 30, 125–135.

Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the job demands-resources model: a ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ. Dyn. 46, 120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.008

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 25, 293–315. doi: 10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Sekiguchi, T. (2007). A contingency perspective of the importance of PJ fit and PO fit in employee selection. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 118–131. doi: 10.1108/02683940710726384

Spector, P. E. (1997). Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Srikanth, P. B. (2019). Developing human resource competencies: an empirical evidence. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 22, 343–363. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2019.1605580

Suliman, A. A., and Al-Junaibi, Y. (2010). Commitment and turnover intention in the UAE oil industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 21, 1472–1489. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2010.488451

Tang, J., Liu, M. S., and Liu, W. B. (2017). How workplace fun influences employees' performance: the role of person–organization value congruence. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 45, 1787–1801. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6240

Tarigan, V., and Ariani, D. W. (2015). Empirical study relations job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 5, 21–42.

Tett, R. P., and Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 46, 259–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x

Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., and Allen, D. G. (2014). Fun and friends: the impact of workplace fun and constituent attachment on turnover in a hospitality context. Hum. Relat. 67, 923–946. doi: 10.1177/0018726713508143

Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., and Bartlett, A. (2012). The fundamental role of workplace fun in applicant attraction. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 19, 105–114. doi: 10.1177/1548051811431828

Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., and Stafford, K. (2013). Does fun pay? The impact of workplace fun on employee turnover and performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 54, 370–382. doi: 10.1177/1938965513505355

Tews, M. J., Michel, J., Xu, S., and Drost, A. J. (2015). Workplace fun matters … but what else? Empl. Relat. 37, 248–267. doi: 10.1108/ER-10-2013-0152

Tidwell, M. V. (2005). A social identity model of prosocial behaviors within nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 15, 449–467. doi: 10.1002/nml.82

Tran, Q. H. (2021). Organisational culture, leadership behaviour and job satisfaction in the Vietnam context. Int. J. Org. Anal. 29, 136–154. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-10-2019-1919

Tubre, T. (2000). Jackson and schuler (1985) revisited: a meta-analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conflict, and job performance. J. Manag. 26, 155–169. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600104

Van Vianen, A. E. (2000). Person-organization fit: the match between newcomers' and recruiters' preferences for organizational cultures. Pers. Psychol. 53, 113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00196.x

Wheeler, A. R., Gallagher, V. C., Brouer, R. L., and Sablynski, C. J. (2007). When person-organization (mis) fit and (dis) satisfaction lead to turnover: the moderating role of perceived job mobility. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 203–219. doi: 10.1108/02683940710726447

Wingreen, S. C., LeRouge, C. M., and Nelson, A. C. (2017). Managing IT employee attitudes that lead to turnover: integrating a person-job fit perspective. IJHCITP 8, 25–41. doi: 10.4018/IJHCITP.2017010102

Wu, F., Ren, Z., Wang, Q., He, M., Xiong, W., Ma, G., et al. (2021). The relationship between job stress and job burnout: the mediating effects of perceived social support and job satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med., 26, 204–211. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1778750

Yeh, C. M. (2013). Tourism involvement, work engagement and job satisfaction among frontline hotel employees. Ann. Tour. Res. 42, 214–239. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.02.002

Yerkes, L. (2007). Fun Works: Creating Places Where People Love to Work. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Keywords: organizational commitment, job satisfaction, person-organization fit, educational manager, Vietnam

Citation: Huynh THP, Bui TQ and Nguyen PND (2023) How to foster the commitment level of managers? Exploring the role of moderators on the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A study of educational managers in Vietnam. Front. Educ. 8:1140587. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1140587

Received: 09 January 2023; Accepted: 22 February 2023;

Published: 09 March 2023.

Edited by:

Khalid Abed Dahleez, A’Sharqiyah University, OmanReviewed by:

Mohammed Aboramadan, University of Insubria, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Huynh, Bui and Nguyen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Phuong N. D. Nguyen, bm5kcGh1b25nQGhjbWl1LmVkdS52bg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.