95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 20 February 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1134128

This article is part of the Research Topic Linking Past, Present and Future: the Development of Historical Thinking and Historical Competencies Across Different Levels of Education View all 5 articles

The objective of this study is to analyse how the Early Modern Age is taught in secondary school textbooks in Spain. To do so, the study is focused on the analysis of the historical contents of this period, in relation to the topics proposed by historiographical trends. In addition, the textbook activities has been analised according to their type, cognitive level and the historical skills required of secondary students. The sample consists of a total of 770 activities. A mixed methodology has been used, combining quantitative and qualitative techniques. The results obtained indicate that the textbooks have improved in the type of activities and in the cognitive level required, but continue to dominate the contents of concepts, facts and concrete data (related to political and cultural history). On the other hand, the textbooks present a discourse which does not debate or reflect in the development of many of the historiographical stereotypes of the nation, neither does it examine in depth the social problems of the Early Modern Age.

The Early Modern Age is a key period for the understanding of the social, economic, political, cultural and philosophical system of the present-day. It can be defined and characterised in Europe and the West by processes such as the expansion of commercial capital and the growing power of the bourgeoisie, European maritime expansion and the great geographical discoveries, the rise of the nation state via authoritarian and absolute monarchies, the birth of humanism, scientific advancement and empirical research, the schism within Christianity and changes taking place within an ancient demographic system leading to the foundation of the current demographic regime. The teaching of history must aim higher than the narration of historical feats of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries and establish links with the phenomena of the present day in such a way that knowledge relating to this period becomes an essential part of the development of educational competences (García-González et al., 2020).

The adaptation of educational competences to the subject of History implies a historical literacy on the part of the students which extends beyond the mere memorisation of concepts, events and dates and which seeks to interpret the predominant historical narratives found in curriculums and textbooks in an appropriate way. Thus, a different cognitive learning model which students to think historically via the method of the historian is required (Gómez et al., 2014a,b; Gómez and Miralles, 2017). The contribution of substantive contents relating to modern history towards students’ historical literacy should take into account the concept of historical relevance (Seixas and Morton, 2013). This concept should present the meaning of the past, and knowledge thereof, as a reality which is not static, but rather one which is under construction based on research questions as a response to present-day problems or to questions which are of relevance to students. Indeed, it is of great importance to present historical contents to secondary school pupils from the point of view of relevant social problems (Sáiz, 2010) as such contents can provide knowledge of historical processes from the Early Modern Age in order to form a critical understanding of society today.

The textbooks used by teachers are a fundamental analytical tool for discovering the historical contents taught in the classroom. Thus, this paper takes into consideration the following questions: Which topics are taught the most? What historiographical approach do they describe? Are these topics updated in the light of new historiographical trends? Furthermore, taking into consideration the activities contained in these textbooks, a reflection is made on their nature regarding the historical period in question: What cognitive skills do the activities aim to develop? Do they train secondary students in the skills of historical thinking and/or social analysis from a critical perspective (Sáiz, 2013; Gómez et al., 2014b; Colomer et al., 2018).

Textbooks are the most commonly used teaching materials in the classroom in Spain (Martínez et al., 2009). They constitute a teaching and learning tool which facilitates the work of the teacher and acts as an intermediary between the student and the subject (Prats, 2012). They are a cultural, academic, commercial and ideological product and, as such, their use and abuse has been analysed in a plethora of studies (Gómez and Miralles, 2017). Articles on the topic of textbooks have constituted an extremely productive line of research over the course of the last two decades (Valls, 2001, 2008; Sáiz, 2011, 2013, 2017; Martínez, 2012; Prats, 2012; DICSO Research Group, Gómez et al., 2014a; Gómez and Molina, 2017; Colomer et al., 2018; Rodríguez and Solé, 2018). As far as research relating to the analysis of textbook contents is concerned, the studies by Valls (2008), López-Facal (2010), Sáiz (2011), Inarejos (2013), and Cuenca and López (2014) are all worthy of note. In terms of research on historical time, the analysis of the activities contained in textbooks and their relationship with competences, the following studies stand out: Blanco (2008), Sáiz (2011, 2013, 2015), Gómez (2014), Colomer et al. (2018), Martínez-Hita and Gómez-Carrasco (2018), and Casanova-García (2020). All of these studies share the point of view that historical knowledge involves thinking, analytical and interpretative skills and that the historical contents selected for school curriculums and textbooks frequently correspond to concepts, events and dates which impoverish the teaching of history. It is proposed, therefore, that methodologies be implemented which develop the strategies and skills of the historian, such as searching for, selecting and handling historical sources, empathy and historical perspective and the creation of historical narratives (Gómez et al., 2019).

The role of textbooks is to transmit knowledge and a sense of the hegemonic reality in accordance with those who hold power (Gómez et al., 2014a). They have commonly been used by states to develop collective identities and to legitimate institutions and international relations (Carretero, 2008; Foster, 2012; Gómez and Chapman, 2017; Sáiz, 2017). The Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research in Braunschweig (Germany); the Emmanuelle project in France and the MANES (Manuales escolares) research centre in Spain stand out as notable research centres on textbooks. The latter are closely related with the Latin American world and messages of identity linked with school textbooks (Sáiz, 2017; Carretero, 2019; Maraña-Hidalgo, 2019). Studies along the same lines can also be found originating from other countries, as is the case of Hasani-Idrissi (2021) in Morocco and Johnson-Khokar (2021) in Pakistan.

In collaboration with other universities (Murcia, Granada and Sevilla) and with associations such as the Fundación Española de Historia Moderna (FEHM, Spanish Foundation of Early Modern History) and Herpérides, researchers from the University of Castilla-La Mancha have organised meetings of researchers, teachers and students to discuss the way in which the Early Modern Age is taught in secondary education. To date, four national and international congresses have been held (2014, 2015, 2019 and 2022) with the aim of bringing history research closer to the classroom context. This constitutes an attempt to highlight historical topics which are of relevance to society and to put forward a new model for the teaching of the Early Modern Age placing emphasis on its role in the understanding of present-day society. Many contributions and research proposals have been put forward concerning the teaching of the history of the Early Modern Age in secondary education, ranging from theoretical research proposals to teaching proposals which are of use in the everyday practice of researchers and teachers (García-González et al., 2016a,b, 2020).

As far as studies dedicated to the analysis of general contents in secondary school textbooks on the Early Modern Age are concerned, those by Henarejos-Carrillo (2016), Simón-García (2016) and Maia (2020) are worthy of note, along with the studies by Martínez-Hita (2016) and Irigoyen-Bueno (2020) on the discovery of America and other key topics of this period, such as the Empire and the War of Succession and how they are dealt with in textbooks (Casanova-García, 2020). Other relevant studies include those on social movements in the Philippines (Inarejos, 2013, 2016), the Black Legend in textbooks (Gómez and Rodríguez, 2020) and the place of ethnic and religious minorities, such as the Moriscos and Conversos, in school textbooks (Moreno-Díaz del Campo, 2020). The issue of gender is gaining presence in this line of research (Rausell-Guillot, 2017; Moreno-Díaz del Campo, 2020), along with other issues such as the analysis of images and illustrations of the Early Modern Age in textbooks (Gallego and Gómez, 2016; Rodríguez, 2020) and the role of peasants as a key group of analysis in the Early Modern Age (Jávega-Bonilla, 2016; Gómez and García, 2019). These are new proposals, topics and contents which seek to improve the teaching and learning process, to increase the motivation of secondary students and to facilitate the application of contents in order to achieve a higher level of significance and relevance of student learning (García-González et al., 2020).

The main objective of this study is to analyse how the Early Modern Age is taught in secondary school textbooks. To do so, attention is focused on the analysis of the contents of this period of history in textbooks, how it is approached in the textbooks used by teachers in the classroom and its relationship with the historiographical trends.

The specific objectives to ensure the success of this main objective are as follows:

• To analyse the historical contents of the Early Modern Age in secondary education textbooks in relation to the topics proposed by historiographical trends.

• To analyse the activities contained in the textbooks according to their type, cognitive level and the historical skills required of secondary students.

For the analysis of the historical contents of the Early Modern Age in school textbooks, three books, published by Anaya, Oxford and Vicens Vives in 2015, corresponding to the LOMCE Spanish educational law, were selected. The selected books were for use in the second year of compulsory secondary education and 770 activities relating to the contents of the Early Modern Age were analysed with the aim of observing the way in which historical skills were applied (Table 1).

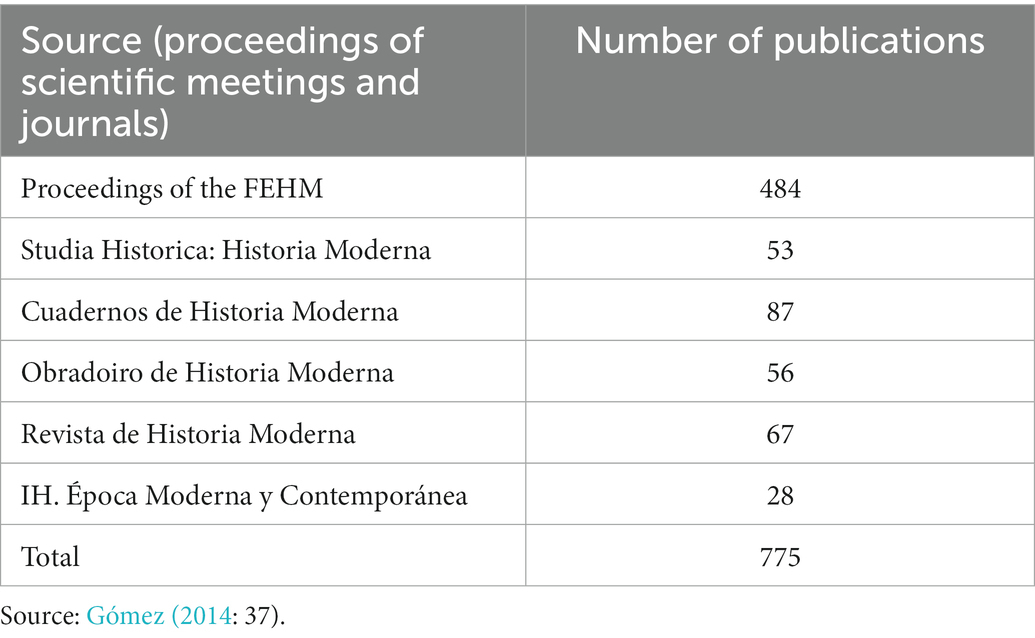

In order to carry out a comparative analysis of the historical contents of the textbooks and the topics developed by researchers of the Early Modern Age, the study by Gómez (2014) on publications in journals and scientific meetings in the field of Early Modern History was taken as a point of reference. The aforementioned study analyses 484 book chapters and 291 articles on this specific period of history (Table 2).

Table 2. Publications on the Early Modern Age analysed in the proceedings of the FEHM and in five prestigious journals.

With this study as a starting point, the analysis was broadened to include publications by the FEHM up to the present day (García-Fernández, 2016; Fortea et al., 2018; Pérez-Samper and Beltrán Moya, 2018) and certain journals, such as Studia Histórica (monographs 2016–2022) and IH, Investigaciones Históricas (articles ranging from 2016 to 2020).

The data collection instrument for the activities included in the textbooks was designed in an Excel database and was divided into four categories: historical contents; type of activity/exam question; cognitive level required; presence of first and second-order concepts. Examples of this categorisation can be found in other studies: on textbook activities, see Gómez (2014) and Gómez and Miralles (2016); on examinations, see Gómez and Miralles (2015). The categorisation can be observed in Tables 3–6. On another, more extensive, categorisation of historical contents, see Gómez and Chapman (2017) and Gómez et al. (2019).

Table 4. Meaning and examples of the cognitive level required of students in the activities contained in the textbooks.

Table 5. Meaning and examples of the first and second-order concepts present in the activities contained in the textbooks.

In order to define the cognitive level required in the activities contained in the textbooks, the studies by Sáiz (2011, 2013, 2015) have been taken as a point of reference. In this categorisation, Bloom’s Taxonomy of objectives-learning stages has been applied in one of its most recent versions adapted by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). This has made it possible to classify the learning outcomes of the activities proposed in the textbooks into cognitive levels. Bloom’s Taxonomy demonstrates that it is possible to formulate questions and activities of different levels. However, this categorisation has its limitations due to the fact that human knowledge is not so linear or accumulative (Escamilla, 2011). Therefore, the cognitive categorisation of questions and the comprehension of texts has been added to this taxonomy (Vidal-Abarca, 2010). On the one hand, there are literal questions (of a low cognitive level) which require a simple pattern of information seeking (locating-memorising), while, on the other hand, there are inferential questions (of a high cognitive level), the search pattern of which is more complex (reviewing-relating-integrating; inferring-reasoning).

This ranking can also be applied to the very procedures of the teaching and learning of history (Hernández, 2002): working with thematic historical maps; images of the different types outlined above; graphs, tables or charts; and chronological axes. Two levels can be differentiated in these procedures. First of all, there is a low level, represented by procedures which generate a high degree of automatisation, which are merely techniques as they require the learning and practice of basic rules of a descriptive or mechanical nature. Secondly, certain procedures demand the activation of wide-ranging cognitive resources as they are not merely rules, but rather principles of a more explanatory nature, which imply relating information with other sources, inferring or deducing information contained within a map, graph, chronological axis or image and the elaboration of explanations or hypotheses. Based on these criteria, a conceptual model for the analysis of activities contained in history textbooks has been proposed, consisting of three levels according to their cognitive complexity after Sáiz (2011, 2013, 2015) model, as shown in Table 4.

For the analysis of the presence of first and second-order concepts (the latter relating to historical thinking skills), the proposal set out by Seixas and Morton (2013) has been used as the foundation, whilst also taking into consideration the proposals made by Domínguez (2015). The proposal here has been adapted to the activities of the textbooks, as shown in Table 5. Furthermore, two types of first-order concepts (chronology, conceptual/factual) have also been added, as has been the case in prior studies on examinations (Gómez and Miralles, 2015) and on textbooks (Gómez, 2014).

In relation with the historiographical discourse and from a global perspective, the historical contents of the textbooks are presented from a combination of classical positivism, or the Ranke model (a sequence of data and dates from a chronological point of view), and a structural model inherited from the Annales historiographical school (Gómez and Miralles, 2017). The topics dealt with in the most widely used textbooks in Spain tend to faithfully reproduce the epigraphs of the official education laws (Sáiz, 2010), as can be observed in Table 7.

Table 7. Early Modern Age topics established in textbooks for the second year of secondary education according to the official curriculum (LOMCE).

In the textbooks analysed, the topics relating to the Early Modern Age are presented in chronological order according to the main political stages of this period. The historical contents worked on in the second year of secondary education take in the Early Modern period of the 15th–17th centuries. The 18th century is studied in the third year along with contents relating to the 19th century.

The units dealing with this period correspond to the birth of the Modern State, the Renaissance and Humanism, the geographical discoveries, the authoritarian monarchy of the Catholic Monarchs, the Habsburg Empire and the 17th century or Baroque Period. It is possible to observe the pre-eminence of political history, inherited from positivism, not only in terms of number of pages but also in how the units are organised. Political circumstances are the vehicle for structuring historical narratives. Based on this way of organising the historical contents, the discourse develops other economic, social, cultural and artistic topics according to the structuralist perspective of the Annales school, towards a vision of total history (Miralles et al., 2011).

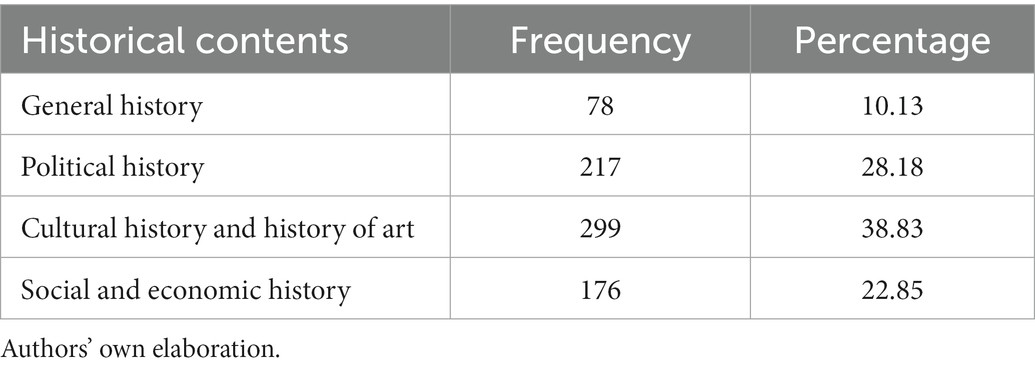

The results also show how historical contents relating to cultural history and the history of art have gained ground in secondary education textbooks, followed by those relating to political and institutional history. These two areas comprise 67% if the activities on the Early Modern Age in the textbooks analysed (Table 8). Social and economic history occupy a secondary position, with around 23% of the activities. In comparison with previous studies on textbooks (Gómez and Miralles, 2017), the activities relating to social and economic topics are somewhat more representative, although they still do not reach the levels achieved by political history and much less cultural history and the history of art.

Table 8. The type of historical contents contained in textbook activities on the Early Modern Age (2nd year of secondary education).

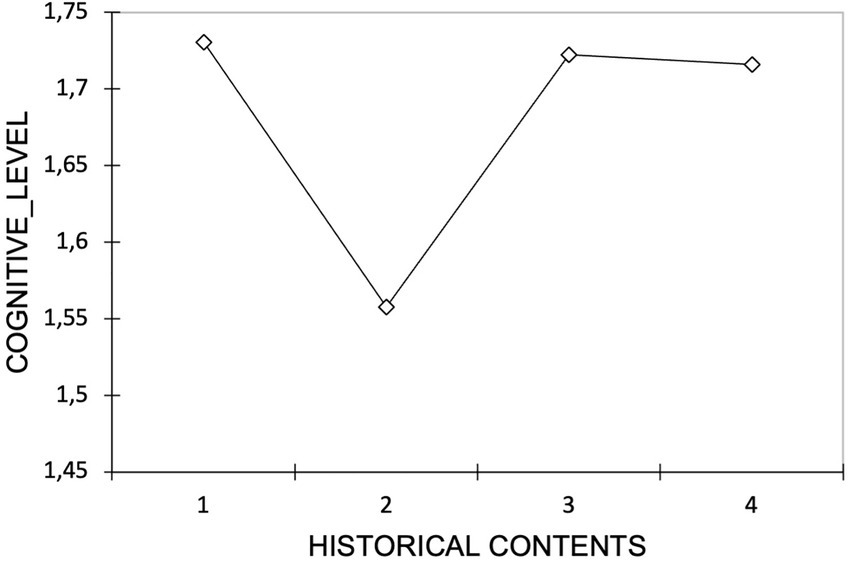

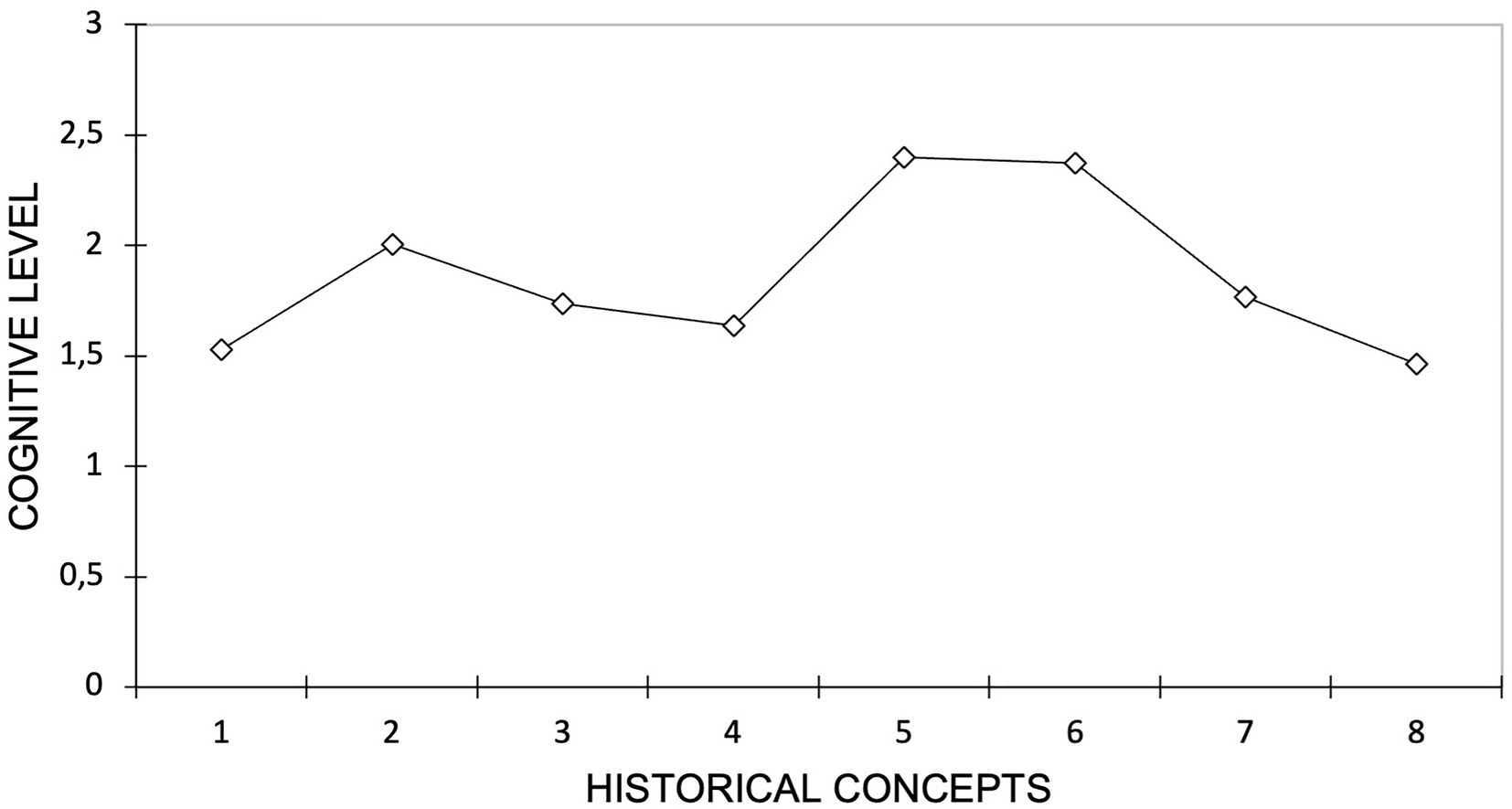

In order to know the complexity of the activities classified according to the historical contents in Table 8, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out. The results show that there are significant differences (p = 0.03) between the activities concerning political and institutional history (with a low cognitive level) and those contents relating to matters of economic, social, cultural and art history (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relationship between the type of historical contents and the cognitive level of activities relating to the Early Modern Age in textbooks (2nd year of secondary education).

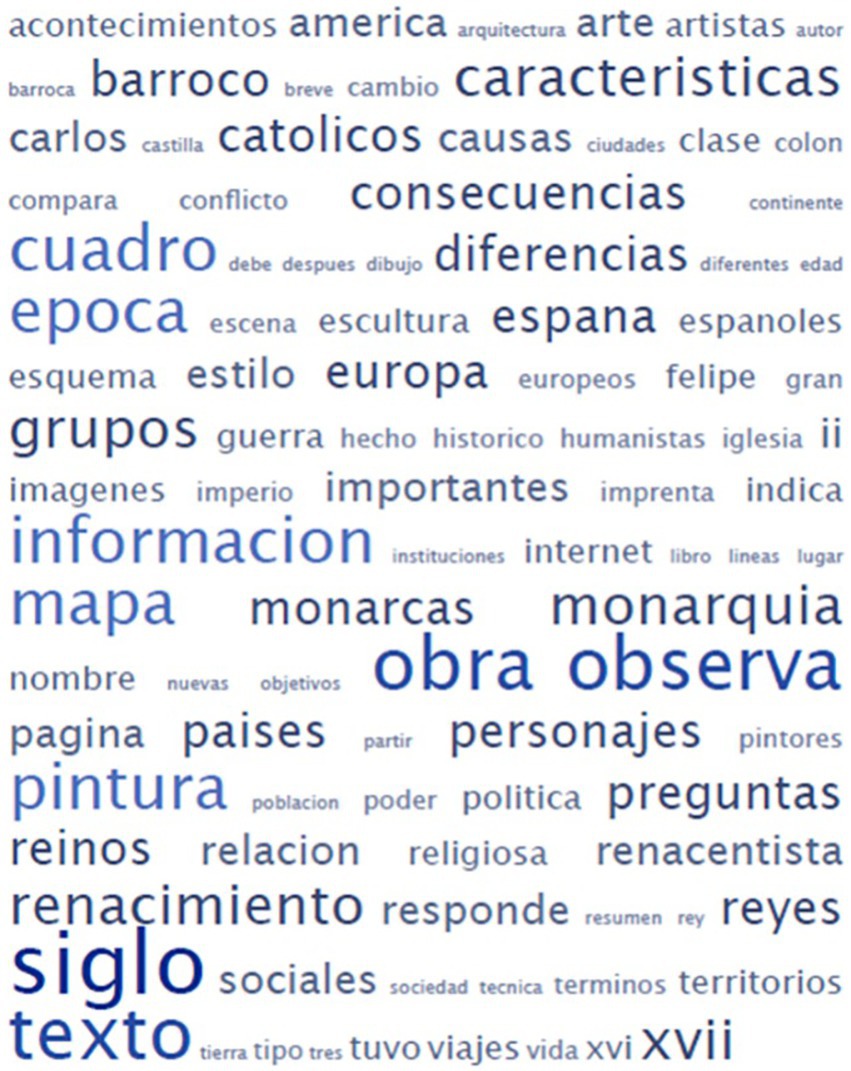

It is often the case that questions on political history, such as What were the main kingdoms of the east of Europe? and Who were the Catholic Monarchs? require skills relating to reading, description, locating, repetition, reproduction and/or memorisation, although some, such as the latter, also require understanding and even consultation of other sources. However, activities such as State the relationship between the English and Flemish textile industries and Castilian transhumant livestock rearing, Why did the Portuguese and the Spanish search for new routes to reach India? and Why did the new humanist philosophy bring about the progress of scientific knowledge? which are connected with economic, social and cultural aspects, require cognitive skills relating to comprehension, relationship, application and critical evaluation. Following a qualitative analysis to observe the most repeated terms and concepts in the activities of the selected 2nd-year textbooks, a word cloud was created (Figure 2). The size of the words represents those which are most repeated in the school textbooks analysed. The most represented concepts are closely related with cultural and artistic aspects (work of art, painting, art, Renaissance, Baroque, humanist, architecture, sculpture, authors, printing press, book, technique, religion, etc.), followed by those relating to political and institutional history (monarchy, reigns, monarchs, Catholic Monarchs, Charles I, Philip II, empire, territories, Europe, Spain, America, countries, institutions, power, Church, war, conflict, etc.) and a lower presence of those relating to economic and social issues (population, social groups, society, age, class, cities, land, life). It is also possible to observe the level of complexity required of the secondary students in the handling of historical knowledge (observe, summarise or state) and the approach proposed for the analysis of the historical knowledge (characteristics, causes, consequences, differences, questions, events, historical fact, name, types, outline, summary).

Figure 2. The most representative terms and concepts contained in the activities of the selected textbooks (2nd year of secondary education).

As far as how the contents of the textbooks are handled in terms of the proposals of recent historiography is concerned, the results demonstrate a lack of updating of the contents taught in the classroom. The topics contained within the textbooks do not encompass many of the current concerns of Spanish historians. For this reason, the study by Gómez (2014) has been taken as a reference point along with more recent publications (between 2015 and 2022) in the FEHM and in other journals such as Studia Histórica and IH. A change from history to social concerns has taken place, with an interest arising in the study of social minorities or marginalised groups (healers, washerwomen, servants), identities and stereotypes relating to gender and age, the proliferation of biographies and trajectories of families and individuals as subjects of historical reflection and moving beyond traditional geographical spaces towards others of a peripheral nature (Hernández, 2018). The main issues concerning historiography are: taxation issues (Sánchez-Durán, 2019); oligarchies and local elites (Chacón-Jiménez and Hernández-Franco, 2019); the organisation of territory; vertical and horizontal networks and relations of power between different political, religious and economic institutions (Pullido-Serrano, 2018); families and patrimony (Salas-Almeda, 2016; Carrasco-González, 2018); everyday life (Franco-Rubio, 2018); the image of power, ceremonies and festivities (Moreno-Díaz del Campo, 2020; García-Cárcel and Serrano, 2021); social inequalities, assistance and marginality (Rivasplata-Varillas, 2018; González-López, 2020; García-González, 2021); and social conflict (Torres-Arce, 2018; Mantecón-Movellán et al., 2020). These topics are far-removed from the linear, political and traditional discourse which persists in textbooks (Gómez and Miralles, 2017).

Influenced by different historiographical trends, current research on the Early Modern Age has shown changes in how political topics are approached, focusing on: local elites and the reproduction and consolidation of power (Chacón-Jiménez and Hernández-Franco, 2019); relationships of dependence; war and soldiers with elements relating to everyday life and social advancement (Herrero Fernández-Quesada, 2020); the reassessment of the study of specific kings and queens; and the image of power from a new model of political history influenced by post-modernist trends (Pérez-Samper, 2020). However, in the selected textbooks, the activities approach the contents based on the conceptualisation of power and its manifestations, the history of the Habsburg Monarchy, the actions carried out by kings and favourites and the dates of specific battles and peace treaties (Which foreign conflicts sustained the first Habsburg monarchs? List the different peace treaties which led to the loss of territories).

Researchers of social and economic history have proposed a change in the historical analysis of social structure focusing more on social relationships. Family and individual strategies and histories have become the object of analysis to provide understanding of the social fabric (García-González, 2021). Social groups such as those in power, traders and the marginalised (prostitutes, Moriscos, tramps and conversos) have been studied from this new perspective (Montanel-Marcuello, 2018; Rivasplata-Varillas, 2018; Moreno-Díaz del Campo, 2020). In comparison with the contents included in the textbook activities, they are materialised in the description of the general characteristics of the population, social stratification and its evolution, the general characteristics of the economy of Spain and Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries (growth and crisis) and some mentions of marginalised groups such as Moriscos and beggars (What factors led to the expulsion of the Moriscos? What ideological principles was the decision based upon?).

Issues relating to everyday life and material life (housing, clothing, food, etc.), the re-evaluation of the role of women and gender relationships (Rey-Castelao, 2021) and studies relating to conflict, disorder and justice on a local level (Álvarez Delgado, 2022) are of particular interest to researchers, who have studied them in great detail. However, they are barely present in the secondary education textbooks analysed (What changes took place in people’s everyday diet in the 16th and 17th centuries? Why was this so? What type of furniture and possessions can you find? Which social group do you think lived in each house?).

As far as the history of culture and art are concerned, a great number of studies focus on image, representation, propaganda, ceremonies, devotions and festivities (León-Vegas, 2015). There are also studies on private libraries, books and the printing industry (Barber Castellà, 2018). However, in the activities analysed in 2nd-year textbooks, these types of historical contents are approached via humanism and the Renaissance, the Reformation, the definition of artistic styles and by listing works of art and authors (What was the Renaissance? By which ancient civilisations was it inspired? What new artistic techniques arose in the Renaissance? In which country did the Renaissance begin? In which two stages can it be divided?).

Lastly, in relation to the topic of America as one of the key aspects of the Early Modern Age, historians focus their attention on the organisation of American territory (Díaz-Ceballos, 2018), marital strategies, family links and local oligarchies, influenced by microhistory (Levi, 2003). There is a recognition of peripheral spaces in the narrative of imperial history. The case studies, comparative history, biography and prosopography relate themes, ideas, objects and individuals with their social context (Burke, 2018). In school textbooks, the activities on this topic focus on the discovery of America and the organisation of the colonised territories (List the present-day countries which were under the control of Castile. Which empire did Hernán Cortés fight against? What was its capital?). No attention is paid to the role of the indigenous allies of Cortés and Pizarro, who are essential in understanding the formation of these complex societies (Díaz-Ceballos, 2018). Furthermore, the negative perspective of Bartolomé de las Casas is neglected and little or nothing is said of miscegenation and its effect on heritage and administration. The shame caused by certain episodes of Spain’s imperial past means that key issues for understanding historical developments are ignored. In comparison with the critical model of history (debate, an initiation in research, etc.) present in textbooks in the United Kingdom, France and Portugal (Gómez and Chapman, 2017; Rodríguez and Solé, 2018), Spanish textbooks tiptoe around controversial and complex issues of the country’s Black Legend related with America, the Inquisition and Philip II (Gómez and Rodríguez, 2020).

According to the data obtained, short questions are the most common type of activities contained in the textbooks analysed, constituting almost 50% of the activities observed (Table 9). A long way behind can be found questions relating to figures and images, which represent a little more than 17% of the activities. The remaining categories (searching for information, text commentary, creation, essay and objective test) represent less than 9% each. There is a lack of questions which lead secondary students to think for themselves regarding social events or to build their historical knowledge in a significant way. Such activities are marginal and are generally those which are worked on least in the classroom (Sáiz, 2010).

A differential analysis was carried out of the variables types of activity and level of cognitive complexity (Figure 3). As can be seen in the results of the ANOVA test (Table 10) and in the post-hoc Tukey-B test (Table 11), the differences are significant, with short questions being those which require the lowest cognitive level. In general, the short questions analysed in the textbooks require an extremely low cognitive level and can be answered with a term, concepts, dates or just a few words.

The educational potential of activities with figures and images, which, in theory, could be related with the second-order concepts of sources and historical evidence, is not adequately exploited in the selected textbooks. Students are asked to observe, summarise, state, identify or briefly explain specific information, concepts or historical events in an extremely guided way, which is, therefore, not well-connected with the historical thinking skills (Seixas and Morton, 2013).

As far as the analysis of first and second-order concepts is concerned, the results (Table 12) show an improvement with regard to prior analyses (Gómez, 2014) as there is a greater presence of second-order concepts.

In spite of this, there is still a great presence of first-order concepts, particularly those of a factual/conceptual nature (more than 50%). Furthermore, these types of activities require a low cognitive level as shown by the results obtained in the ANOVA test (Table 13) and the Tukey test (Table 14) represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Relationship of first and second-order historical concepts with the cognitive level required in the textbook activities (2nd year secondary education).

The conceptual/factual or chronological activities of the textbooks are, on the whole, answered by merely reproducing the historical discourse offered by the book itself (What route did Columbus take on his first voyage? Where did he leave from? Which Caribbean islands did he visit? In which area of the Americas did he disembark?). It is striking that the textbooks contain almost no questions relating to chronological skills, handling dates, the use and creation of chronological axes or timelines (just over 3%). The insistence of the use of short question exercises leads students towards an acritical and atemporal conception of history as has been proven in studies on primary teacher training (Sáiz and Gómez, 2016) and of examinations in secondary education (Gómez and Miralles, 2015).

The concepts of historical thinking are less present, with activities relating to sources and evidence (almost 20%) and historical relevance (almost 12%) standing out. The other categories (historical perspective, causes and consequences, change/continuity and ethical dimension) are not well represented in the textbooks analysed. Such activities, relating to second-order concepts, require a higher cognitive level, as shown in Figure 4. However, some of the activities connected to second-order concepts such as causes and consequences and change and continuity require a low cognitive level. Activities concerning historical perspective and the ethical dimension are those which require a greater degree of complexity. These types of more complex and creative activities are those which guide students towards forming their own way of thinking and building their own knowledge in a significant way, thus contributing to the historical competences (Gómez and Miralles, 2017).

Early Modern historical contents in secondary education textbooks continue to be markedly conceptual in nature. The Early Modern Age is presented in secondary textbooks as a period which is deeply rooted in the main lines of the Spanish and European master narrative. The contents of this model are organised according to political circumstances which act as vehicles for the historical narrative transmitted in the textbooks. Political and institutional history have great weight in this discourse, along with cultural and art history, which has gained relevance in the structure of the historical contents (the great stages of the Early Modern Age: Humanism and Renaissance, the Baroque and the Enlightenment). The main focus of the textbooks (and also of the curriculum) is on the nation as the historical subject and, to a large extent, the Early Modern Age has contributed to this. From the birth of the Early Modern Age and the justification of the unity of Spain with the politics of the Catholic Monarchs and the conquest of Granada (as the origin of the nation); the conquest and colonisation of the Americas, the empire of Charles V and the Hispanic monarchy of Philip II (as the age of international splendour); the decadence and crisis of the last Spanish Habsburgs; and the recovery under the centralising policies of the Bourbons (Gómez et al., 2019).

The introduction of competences into the curriculum has led to the development of a dual model of historical knowledge. Hegemonic contents of a factual/conceptual nature, based around the model of a national and European historical narrative, must be approached in the classroom from a more skills-based perspective (comprehension, reflection, synthesis, explanation, etc.). Such approaches have been reflected in textbooks where it is possible to find an improvement in terms of the complexity and variety of activities in comparison with other previous studies (Gómez, 2014). However, the most frequent types of activities contained in textbooks continue to be those of a conceptual/factual nature related to political and institutional history, which require a lower cognitive level. Such activities do not aim to develop cognitive skills regarding history (second-order concepts), but rather memorisation and the comprehension or application of factual and conceptual knowledge. They do not encourage reflection on the main landmarks of nation building which make it possible to understand historical science as a subject under construction with its own method of analysis. This leads to the production of textbooks with a great lack of activities based on second-order concepts related to historical thinking (Gómez et al., 2019).

The approach to history employed in textbooks should not be far-removed from the epistemological foundations of history as a science, taken by Carr (1987) to be a continual process of interpretation between the historian and the events, an unending dialogue between the present and the past. However, the model of history put forward by the LOMCE curriculum in Spain and by the textbooks in use presents a discourse which does not debate or reflect on the construction of many of the historiographical stereotypes of the nation or the process of the construction of Europe, neither does it examine in depth the social problems of the Early Modern Age.

An obsession for a succession of “ages” or periods reduces the past to the mummified logic of chronology. It is proposed here that critical thinking be empowered and historical contents be dealt with based on relevant problems which develop a critical perspective of the present and lead to a sense of meaningfulness and motivation among students (Sanchiz and Amores, 2016). Furthermore, there is a need to link the everyday lives of men and women of the past with the great historical processes. Without a doubt, social history has an important role to play when establishing connections between the past, the present and students’ interest in historical knowledge (Gómez and Miralles, 2017). The questions asked should respond to problems which are relevant for the students of today (Sáiz, 2010). This makes it possible, therefore, to propose key topics such as social inequalities, differences of gender and age, models of family organisation, relationship networks, social mobility processes, conflict and/or material and immaterial culture, all of which are topics dealt with by the most recent historiographical trends (Pérez-Samper and Beltrán Moya, 2018; Chacón-Jiménez and Hernández-Franco, 2019; Casanova-García, 2020; Mantecón-Movellán et al., 2020; Rey-Castelao, 2021). These proposals have already been put forward from the field of the teaching of early modern history by researchers and secondary education teachers (García-González et al., 2020). The new LOMLOE curriculum contemplates the historical contents and basic knowledge of secondary education in a transversal way with the aim of analysing processes of change. To a large extent, this approach encompasses the principles of historical thinking. Now, it is up to the education community to put this into practice in the classroom.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Álvarez Delgado, L. (2022). Justicia y Poder en el Siglo XVI. La Incidencia de Facciones Locales en el Occidente Asturiano. Madrid: Fundación Española de Historia Moderna (FEHM)

Anderson, L. W., and Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revisión of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Nueva York: Longman.

Barber Castellà, F. (2018). La biblioteca de los señores de Guadamar (siglos XVII-XVIII) En M. A. Pérez Samper and y D. L. Beltrán Moya (Eds.). Nuevas perspectivas de investigación en la Historia Moderna: Economía, Sociedad, Política y Cultural en el Mundo Hispano (pp. 990–999). Madrid: Fundación Española de Historia Moderna.

Blanco, A. (2008). La representación del tiempo histórico en los libros de texto de primero y segundo de la Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria. Enseñanzas de las Ciencias Sociales. Rev. Invest. 7, 77–88.

Burke, P. (2018). Pérdidas y ganancias. Exiliados y expatriotas en la historia del conocimiento de Europa y las Américas 1500–2000. Madrid: Akal.

Carrasco-González, M. G. (2018). Del patronazgo familiar al conflicto. Trayectoria familiar de un comerciante gaditano. Revista IH. Historia Moderna y Contemporánea 38, 287–314. doi: 10.24197/ihemc.38.2018.287-314

Carretero, M. (2008). Documentos de Identidad. La Construcción de la Memoria Histórica en un Mundo Global. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Carretero, M. (2019). Pensamiento histórico e historia global como nuevos desafíos para la enseñanza. Cuadernos de Pedagogía 495, 59–63.

Casanova-García, J. M. (2020). La enseñanza de la Historia Moderna en los manuales escolares en el tránsito de la Educación Primaria a la Secundaria a partir de hitos significativos: América, el Imperio español y la Guerra de Sucesión. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, R. Cózar, and P. Miralles (Coords.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Contenidos, Métodos y Representaciones (pp. 81–92). Cuenca: Ediciones de la UCLM.

Chacón-Jiménez, F., and Hernández-Franco, J. (Eds.) (2019). Organización Social y Familias. XXX Aniversario Seminario Familia y Élite de poder. Murcia: Edit.um.

Colomer, C., Sáiz, J., and Valls, R. (2018). Competencias históricas y actividades con recursos tecnológicos en los libros de texto: nuevos materiales y viejas rutinas. Revista Ensayos 33, 56–64.

Cuenca, J. M., and López, I. (2014). La enseñanza del patrimonio en los libros de texto de Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia para ESO. Cult. Educ. 26, 1–43. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2014.908663

Díaz-Ceballos, J. (2018). Negociación, consenso y comunidad política en la fundación de ciudades en Castilla del Oro en el temprano siglo XVI. Revista IH. Historia Moderna y Contemporánea 38, 131–160. doi: 10.24197/ihemc.38.2018.131-160

Escamilla, A. (2011). Las Competencias en la Programación de Aula (vol. II). Educación Secundaria (12–18 Años), Barcelona: Graó.

Fortea, G., Gelabert, J. E., López, R., and Postigo, E. (2018). “Monarquías en conflicto” in Linajes, Nobleza en la Articulación de la Monarquía Hispánica (Madrid: FEHM)

Foster, S. (2012). Re-thinking history textbooks in a globalized world. En M. Carretero, Y. Asensio, and M. Rodríguez-Moneo (Eds.). History Education and the Construction of National Identities (pp. 49–62). Charlotte: IAP Publishing.

Franco-Rubio, G. A. (2018). El ámbito doméstico en el Antiguo Régimen: de puertas para adentro. Madrid: Editorial Síntesis.

Gallego, S., and Gómez, C. J. (2016). Imágenes y estereotipos de género en las unidades didácticas del siglo XVIII Y XIX. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and Y R. A. Rodríguez (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de investigación (pp.127–141). Murcia: Edit.um.

García-Cárcel, R., and Serrano, E. (Eds) (2021). Historia de la Tolerancia en España. Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid.

García-Fernández, M. (Ed.) (2016). Familia, Cultura Material y Formas de Poder en la España Moderna. Madrid: FEHM.

García-González, F. (Ed.) (2021). Familias, Trayectorias y Desigualdades. Estudios de Historia Social en España y Europa (Siglos XVI-XIX). Madrid: Silex.

García-González, F., Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., Cózar-Gutiérrez, R., and Miralles-Martínez, P. (Coords.) (2020). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Contenidos, Métodos y Representaciones. eds. García-González, Gómez-Carrasco, Cózar-Jiménez y Miralles-Martínez (Cuenca: Ediciones de la UCLM).

García-González, F., Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., and Miralles, P. (Eds.) (2016a). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Propuestas y Experiencia de Innovación. Murcia: Edit.um.

García-González, F., Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., and Rodríguez-Pérez, R. A. (Eds.) (2016b). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de Investigación. Murcia: Edit.um.

Gómez, C. J. (2014). Pensamiento histórico y contenidos disciplinares en los libros de texto. Un análisis exploratorio de la Edad Moderna en 2.° de la ESO. Ensayos. Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete 29, 131–158.

Gómez, C. J., and Chapman, A. (2017). Enfoques historiográficos y representaciones sociales en los libros de texto un estudio comparativo, España-Francia-Inglaterra. Historia y Memoria de la Educación 6, 319–362. doi: 10.5944/hme.6.2017.17132

Gómez, C. J., Cózar, R., and Miralles, y P. (2014a). La enseñanza de la historia y el análisis de libros de texto. Construcción de identidades y desarrollo de competencias. Ensayos, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 29, 11–25.

Gómez, C. J., and García, P. (2019). Representaciones sociales y la construcción de los discursos en la enseñanza de la Historia. Un análisis a partir del campesinado (SS.XVI-XVIII). Revista Historia y Comunicación social 24, 127–145. doi: 10.5209/HICS.64484

Gómez, C. J., and Miralles, P. (2015). ¿Pensar históricamente o memorizar el pasado? La evaluación de los contenidos históricos en la educación obligatoria en España. Revista de Estudios Sociales 52, 52–68. doi: 10.7440/res52.2015.04

Gómez, C. J., and Miralles, P. (2016). Devéloppement et évaluation des compétences historiques dans les manuales scolaires. Une étude comparative France-Spagne. Spirale. Revue de Recherches en Éducation 68, 55–66. doi: 10.3917/spir.058.0053

Gómez, C. J., and Miralles, P. (2017). Los Espejos de Clío. Usos y Abusos de la Historia en el Ámbito Escolar. Madrid: Sílex Universidad.

Gómez, C. J., and Molina, S. (2017). Narrativas nacionales y pensamiento histórico en los libros de texto de educación secundaria de España y Francia: análisis a partir del tratamiento de los contenidos de la Edad Moderna. Vínculos de Historia 6, 206–229.

Gómez, C. J., Ortuño, J., and Molina, S. (2014b). Aprender a pensar históricamente. Retos para la historia en el siglo XXI. Tempo e Argumento 6, 1–25. doi: 10.5965/2175180306112014005

Gómez, C. J., and Rodríguez, R. A. (2020). Leyenda negra y héroes defenestrados. Análisis del discurso en los libros de texto españoles (1998-2018). En R. M. Alabrús y Otros (Eds.). Pasados y Presente. Estudios Para el Profesor Ricardo García Cárcel. (pp. 115–127). Barcelona: Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

Gómez, C. J., Vivas, V., and Miralles, P. (2019). Competencias históricas y narrativas europeas/nacionales en los libros de texto. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo 49, 210–234. doi: 10.1590/198053145406

González-López, T. (2020). Creencias, asistencia y nacimiento. Dar a luz en el interior de Galicia (siglos XVII-XIX). Revista IH. Historia Moderna y Contemporánea 4, 295–314. doi: 10.24197/ihemc.40.2020.295-314

Henarejos-Carrillo, P. (2016). Análisis de los Contenidos de la Edad Moderna en Una Editorial. Vicens Vives. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and y R. A. Rodríguez (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de investigación (pp. 36–56). Murcia: Edit.um.

Hernández, B. (2018). La conversión de la historia a lo social. Perspectivas desde la historiografía del mundo moderno. En M. A. Pérez Samper and y D. L. Beltrán Moya (Eds.). Nuevas Perspectivas de Investigación en la Historia Moderna: Economía, Sociedad, Política y Cultural en el Mundo Hispano (pp. 253–262). Madrid: Fundación Española de Historia Moderna.

Herrero Fernández-Quesada, M. D. (2020). El relato individual de la batalla. Diarios y hojas de servicio. En R. M. Alabrús, JL. Betrán, FJ. Burgos, B. Hernández, D. Moreno, and y M. Peña (Eds.). Pasados y Presente. Estudios Para el Profesor Ricardo García Cárcel. (pp. 115–127). Barcelona: Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

Inarejos, J. A. (2013). La “pérdida de Filipinas” en los manuales escolares, A vueltas con los contenidos en la enseñanza de las historias en España. Ensayos. Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete 28, 75–85.

Inarejos, J. A. (2016). Los movimientos sociales en la enseñanza de la historia moderna de Filipinas: enfoques y silencios. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and y R. A. Rodríguez (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de investigación (pp. 57–66). Murcia: Edit.um.

Irigoyen-Bueno, A. I. (2020). Imágenes del Descubrimiento de América en los libros de texto de España y México. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, R. Cózar, and P. Miralles (Coords.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Contenidos, Métodos y Representaciones (pp. 399–410). Cuenca: Ediciones de la UCLM.

Jávega-Bonilla, A. (2016). Estereotipos, reproducción y construcción de narrativas históricas: el campesinado en los libros de texto. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and y R. A. Rodríguez (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de investigación (pp. 217–228). Murcia: Edit.um.

Johnson-Khokar, A. (2021). “Nosotros” y “ellos”: análisis de los Libros de texto estudiados en las escuelas de Pakistán. Revista de Educación 392, 205–228. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2021-392-484

León-Vegas, M. (2015). Religiosidad popular y exvoto pictórico: simbiosis de arte, cultura y devoción. En J. J. Iglesias Rodríguez (Ed.). Comercio y Cultura en la Edad Moderna. Comunicaciones de la XIII Reunión Científica de la Fundación Española de Historia Moderna. (pp. 2141–2158). Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla y Fundación Española de Historia Moderna (FEHM).

Levi, G. (2003). Sobre microhistoria. En Burke (Ed.). Formas de Hacer Historia (pp. 119–144). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

López-Facal, R. (2010). Nacionalismos y europeísmos en los libros de texto: identificación e identidad nacional. Clío y Asociados: la Historia Enseñada 14, 9–33. doi: 10.14409/cya.v1i14.1673

Maia, C. (2020). A época moderna nos manuais escolares portugueses: um balanço entre história regulada, história ensinada e história desejada. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, R. Cózar, and y P. Miralles La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Contenidos, Métodos y Representaciones (pp. 23–38). Cuenca: Ediciones de la UCLM.

Mantecón-Movellán, T., Arce, MT., and García, ST. (2020). Las Dimensiones del Conflicto: Resistencia, Violencia y Policía en el Mundo Urbano. Santander: editorial Unican (Universidad de Cantabria).

Maraña-Hidalgo, J. O. (2019). Contenidos en los libros de texto de historia de Bachillerato en México. Revista Clío 45, 251–267.

Martínez, A. M. (2012). El uso de los manuales escolares de historia de España. Análisis de resultados desde la propuesta de Shulman. Iber. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 70, 48–58.

Martínez, N., Valls, R., and Pineda, F. (2009). El uso del libro de texto de Historia de España en Bachillerato: diez años de estudio, 1993-2003 y dos reformas (LGE-LOGSE). Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 23, 3–35.

Martínez-Hita, M. (2016). El Descubrimiento de América y la Edad Moderna en los libros de texto antes de la Educación Secundaria. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and R. A. Rodríguez (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de investigación (pp. 99–110). Murcia: Edit.um.

Martínez-Hita, M., and Gómez-Carrasco, C. J. (2018). Nivel cognitivo y competencias de pensamiento histórico en los libros de texto de Historia de España e Inglaterra. Un estudio comparativo. Revista de Educación 379, 145–169. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2017-379-364

Miralles, P., Ortuño, J., and Molina, S. (2011). El Papel de la Historiografía en la Enseñanza de la Historia. Granada: GEU.

Montanel-Marcuello, M. A. (2018). Marginalidad y Asistencia Social. Huérfanos en la Zaragoza Moderna. En M. A. Pérez Samper and D. L. Beltrán Moya (Eds.). Nuevas Perspectivas de Investigación en la Historia Moderna: Economía, Sociedad, Política y Cultural en el Mundo Hispano (pp. 446–456). Madrid: Fundación Española de Historia Moderna.

Moreno-Díaz del Campo, F. J. (2020). Las minorías ibéricas de la Edad Moderna. Moriscos y judeoconversos en los libros de texto de Enseñanza Secundaria (1970-2010). Una aproximación. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, R. Cózar, and y P. Miralles (Coords.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Contenidos, Métodos y Representaciones (pp. 105–114). Cuenca: Ediciones de la UCLM.

Pérez-Samper, M. A. (2020). Construir y destruir mitos. María Luisa de Parma, una Reina Elogiada y Criticada. En Alabrús, R. M., Betrán, J. L., Burgos, F. J., Hernández, B., Moreno, D., and Díaz, y M. P. (Eds.). Pasados y Presente. Estudios Para el profesor Ricardo García Cárcel. (pp. 1121–1132). Barcelona: Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

Pérez-Samper, M. A., and Beltrán Moya, D. L. (Eds.) (2018). Nuevas Perspectivas de Investigación en la Historia Moderna: Economía, Sociedad, Política y Cultural en el Mundo Hispano. Madrid: Fundación Española de Historia Moderna.

Prats, J. (2012). Criterios para la elección del libro de texto de historia. Íber. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 70, 7–13.

Pullido-Serrano, J. I. (2018). Más que Negocios. Simón Ruiz, un Banquero Español en el siglo XVI entre las Penínsulas Ibérica e Italiana. Madrid: Iberoamericana-Vervuert.

Rausell-Guillot, H. (2017). La Ilustración en 2° de Bachillerato: libros de texto, contenidos y cuestión de género. Panta Rei: Revista de Ciencia y Didáctica de la Historia 21, 109–122. doi: 10.7203/DCES.32.9777

Rey-Castelao, O. (2021). El Vuelo Corto. Mujeres y Migraciones en la Edad Moderna, Santiago de Compostela. Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela.

Rivasplata-Varillas, P. E. (2018). Las lavanderas de instituciones hospitalarias en el Antiguo Régimen. Un estudio de caso. Revista IH. Historia Moderna y Contemporánea 38, 161–186. doi: 10.24197/ihemc.38.2018.161-186

Rodríguez, R. A. (2020). Imágenes e ilustraciones de la Edad Moderna en los manuales de ESO (de la LOGSE a la LOMCE). En F. García, C. J. Gómez, R. Cózar, and P. Miralles, (Coords.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Contenidos, métodos y representaciones (pp. 71–80). Cuenca: Ediciones de la UCLM.

Rodríguez, R. A. Solé, y G. (2018). Los manuales escolares de historia en España y Portugal. Reflexiones sobre su uso en Educación Primaria y Secundaria, Árbor. Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura, 194, 1–12. doi: 10.3989/arbor.2018.788n2004

Sáiz, J. (2010). ¿Qué historia medieval enseñar y aprender en Educación Secundaria? Imago Temporis. Mediun Aevum IV, 594–607.

Sáiz, J. (2011). Actividades de libros de texto de Historia, competencias básicas y destrezas cognitivas, una difícil relación: análisis de manuales de 1° y 2° de ESO. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 25, 37–64.

Sáiz, J. (2013). Alfabetización histórica y competencias básicas en libros de texto de historia y en aprendizaje de los estudiantes. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 27, 43–66. doi: 10.7203/dces.27.2648

Sáiz, J. (2017). “Libros de texto de secundaria y narrativa española (1976-2016)” in Cambios y Continuidades en el Discurso Escolar de la Nación (Barcelona: Revista de Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales), 16, 3–14. doi: 10.1344/ECCSS2017.16.1

Sáiz, J., and Gómez, C. J. (2016). Investigar el pensamiento histórico y narrativo en la formación del profesorado: fundamentos teóricos y metodológicos. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 19, 175–190. doi: 10.6018/reifop.19.1.206701

Salas-Almeda, L. (2016). Estrategias económicas señoriales y matrimonio: el comportamiento nupcial de la casa de Medina Sidonia (1492-1658). Revista IH. Historia Moderna y Contemporánea 36, 13–39.

Sánchez-Durán, A. (2019). Cooperación entre agentes públicos y privados en la gestión de la Real Hacienda castellana: el arrendamiento de las Alcabalas y los Millones de Málaga por el Doctor Andrés de Fonseca (1645-1646). En G. Fortea, J. E. Gelabert, R. López, and y E. Postigo (Coords.) Monarquías en Conflicto. Linajes, Nobleza en la Articulación de la Monarquía Hispánica (pp. 465–476). Madrid: FEHM.

Sanchiz, S., and Amores, P. A. (2016). Revisión metodológica del desarrollo de los contenidos curriculares en Historia Moderna. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and P. Miralles (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Propuestas y Experiencia de Innovación (171–186). Murcia: Edit.um.

Simón-García, M. M. (2016). Contenidos y actividades en la enseñanza de la historia moderna de la educación secundaria para personas adultas. En F. García, C. J. Gómez, and R. A. Rodríguez (Eds.). La Edad Moderna en Educación Secundaria. Experiencias de investigación (pp. 229–244). Murcia: Edit.um.

Torres-Arce, M. (2018). Un palacio para la Inquisición de Palermo: espacio urbano, conflictividad y relaciones de poder. Revista IH. Historia Moderna y Contemporánea 38, 11–48. doi: 10.24197/ihemc.38.2018.11-48

Valls, R. (2001). Los estudios sobre manuales escolares de historia y sus perspectivas. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales 15, 23–36.

Keywords: history, early modern age, textbooks, teaching, secondary education, Spain, activities

Citation: Simón-García MM (2023) The early modern age in secondary education textbooks in Spain: An analysis of activities. Front. Educ. 8:1134128. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1134128

Received: 29 December 2022; Accepted: 19 January 2023;

Published: 20 February 2023.

Edited by:

Raquel Sanchez-Ibañez, University of Murcia, SpainReviewed by:

Raimundo Rodriguez, University of Murcia, SpainCopyright © 2023 Simón-García. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Del Mar Simón-García, ✉ bW1hci5zaW1vbkB1Y2xtLmVz

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.