- Department of Education and Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Acculturation has been shown to be relevant to immigrant students' school adjustment and academic achievement. However, there are methodological constraints to the literature, and only little is known about immigrant students' acculturation patterns as such and their distribution across different demographic groups in Germany. Conceptualizing acculturation as a multidimensional construct, this study aimed to empirically capture acculturation patterns of immigrant students living in Germany considering affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of acculturation. Latent profile analysis identified six distinct profiles of acculturation evocative of strong assimilation, assimilation, integration, strong separation, separation, and marginalization. Taking the two assimilationist and separationist profiles into consideration, assimilation was most prevalent (41% of the sample), followed by separation (38% of the sample), and integration and marginalization each only accounted for ~11% of the sample. Inspection of demographics showed significant differences between profiles regarding gender, generation status, and ethnic group. Findings from research indicate that careful consideration of the operationalization of acculturation is necessary to draw valid conclusions about its relevance to school-related outcomes for immigrant students. This study can serve as a starting point showing the use of latent profile approaches, which give an expanded perspective on immigrant students' acculturation experiences.

Introduction

In Germany, large migration flows in the past and present have led to the fact that linguistic and cultural diversities have become the norm in many places in Germany and that people experience intercultural encounters every day. This is particularly the case for the school context in Germany, where, on average, more than a third of students are currently classified as having an immigrant background, i.e., they themselves or at least one (grand)parent was born abroad. Strikingly, educational research consistently reveals that the group of students with an immigrant background performs below their native peers in standardized tests, receives worse grades, is less likely to attend a Gymnasium, and is more commonly prone to be disadvantaged in the job market. Numerous studies have examined various background characteristics and have typically found explanations for the poorer performance of immigrant students, for example, in the socioeconomic situation of their families or their language use. However, the factors examined can only partially explain the performance gap between students with and without an immigrant background (cf. Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2016). Another approach looks at what the acculturation orientations of young people whose families have migrated to Germany can contribute to explaining their disadvantages in the German education system.

Theoretical and empirical background on acculturation patterns and adaptation

“When groups of individuals having different cultures come into continous[sic] first-hand contact, [acculturation occurs] with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups” (Redfield et al., 1936, p. 149). Based on this definition, in 1997, John W. Berry developed a theoretical model that distinguishes four different ways of acculturation. Based on two theoretically independent dimensions, i.e., depending on the extent to which the culture of the country of origin is retained and how pronounced the orientation toward the people and culture of the receiving country is, a distinction was made between integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization. Integration describes a pattern of acculturation where the individual's orientation toward both the culture of the country of origin and the culture of the receiving country is strong. Assimilation describes a pattern of acculturation where the orientation toward the culture of the country of origin is weak, while orientation is strong toward the culture of the receiving country. Separation describes the opposite pattern where the individual's orientation toward the culture of the country of origin is strong, while it is weak toward the culture of the receiving country. Marginalization describes an acculturation pattern where the individual's orientation toward both the culture of the country of origin and the culture of the receiving country is weak.

In a comprehensive international study, involving more than 5,000 young people from diverse immigrant groups residing in 13 different countries, four distinct patterns of acculturation were demonstrated empirically (Berry et al., 2006). The theoretical model, however, was supported only partially. Conducting cluster analysis with a range of variables on the acculturation experiences of adolescents, including acculturation attitudes, cultural identities, language use and proficiency, peer social relations, and family relationship values, revealed one group of integrated adolescents, a second group of adolescents with a national profile, a third group with an ethnic profile, and a final group with a diffuse profile. The first three profiles were in line with the theory corresponding to the idea of integration, assimilation, and separation, respectively. However, there was no group of marginalized adolescents; instead, a diffuse profile, which was difficult to interpret, emerged. Across all countries, the integration profile was the most common profile among immigrants, including more than one-third of the sample (36.4%). The national profile (i.e., assimilation) showed to be less prevalent than the ethnic profile (i.e., separation; 18.7 and 22.5%, respectively), and no <22.4% of adolescents in the sample pertained to the diffuse profile. However, depending on the group of origin or the host society examined distributions varied: Adolescents with Turkish heritage (n = 714), for instance, showed a strong tendency for separation (40.3%). Among the Vietnamese sample (n = 718), strong tendencies for integration (33.1%) and assimilation (25.6%) emerged and were found to be related to whether they resided in a settler society (e.g., Australia, Canada, or the US) or a European country with rather restrictive immigration laws (Sam and Berry, 2010).

The results of the study provide empirical evidence for the assumption of four different patterns of acculturation and, at the same time, give reason to critically question the theoretical model. The emergence of a diffuse profile, for instance, not only questions the existence of marginalization (see Schwartz et al., 2010) but also possibly reflects that the reality of life for immigrant students is much more complex than can be depicted in a bidimensional approach considering two single cultures. In an increasingly diverse world, adolescents with immigrant backgrounds often find multiple ways to combine different cultural traditions, norms, and values and create flexible, multiple, and hybrid orientations, which can vary depending on the context or situation (Fuligni and Tsai, 2015). Second, the results point to the fact that generalized statements across groups and contexts are not valid. How individuals acculturate depends on societal expectations toward that acculturating and the prevailing ideologies, norms, and politics on diversity (Phalet and Baysu, 2020). Thus, acculturation is not a free choice, and the question of good adjustment is context-dependent.

Berry's (1997) basic assumption is that integration is the most adaptive, marginalization the least adaptive, and assimilation and separation fall in between. Based on this assumption, also coined integration hypothesis, much of the research has been conducted on how acculturation patterns relate to different indicators of successful adaptation to a new context and evidence increasingly challenges the basis of the hypothesis. In Sam and Berry (2010) stated that, most often, studies find integration to be the most adaptive and associated with better psychological and sociocultural adaptation. Moreover, the meta-analysis conducted by Nguyen and Benet-Martínez (2013) found a significant, strong, and positive association between biculturalism, which equals integration, and the psychological and sociocultural adjustment of minority individuals across 83 studies and 23,197 participants. In a recent reanalysis of Nguyen and Benet-Martínez (2013) data, Bierwiaczonek and Kunst (2021) showed that the cross-sectional association between integration and adaptation is much weaker than previously assumed. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of exclusively longitudinal studies (19 studies and 6,791 participants) found that time-lagged effects are inconsistent and tend to be zero for both sociocultural and psychological adaptations (Bierwiaczonek and Kunst, 2021). In addition to the fact that, in meta-studies, the results of samples from diverse ethnic groups acculturating in different contexts were collapsed, another possible explanation can be found in the different operationalization of acculturation and its outcomes.

Immigrant students' acculturation and school adaptation

Against the background of immigrant students' academic underachievement, it is of particular interest for educational research on how acculturation orientations are linked to different school-related outcomes. Following Searle and Ward's (1990) distinction between psychological and sociocultural adjustment, adaptation to the school represents a case of sociocultural adaptation for immigrant students, which entails the competence necessary for successfully coping with everyday life.

Numerous acculturation studies in educational science have specifically looked into the link between minority students' acculturation and different indicators of school adaptation. Berry et al. (2006), for instance, investigated the association between the acculturation patterns identified through cluster analysis of their comprehensive sample of immigrant youths and variables of school-related sociocultural adaptation. In line with their expectations, they found indications speaking for the superiority of integration in terms of immigrant students' school adjustment and problem behavior. Following up on the relationship between how immigrant youth adapt in relation to how they acculturate, structural equation modeling gave support to the expectation that integration, in terms of a combined involvement with the national and ethnic culture, is associated with successful sociocultural adaptation. However, the results also showed that ethnic orientation (i.e., separation) had an effect on sociocultural adaptation and that national orientation (i.e., assimilation) did not have a stronger impact than ethnic orientation on sociocultural adaption.

Using PISA data from six European countries, Schachner et al. (2017) investigated the indirect effects of immigrant adolescents' acculturation orientations on school adjustment through school belonging. Their analysis generally found positive associations between students' mainstream orientation and school-related outcomes. Students' ethnic orientation, however, was found to be beneficial only in countries supportive of multicultural policies, such as Belgium or Finland.

Compiling the body of empirical research on acculturation in the school context, with a focus on the academic achievement of students from minority backgrounds, Makarova and Birman (2015) have provided an overview of studies conducted primarily in the US context. They found that integration was predominantly the most adaptive and promising as well as the most successful school-related outcome but some studies also revealed assimilation as advantageous for students' academic achievement.

For the German context, singular studies have examined the relationship between acculturation patterns and the educational adaptation of immigrant students. Drawing on data from PISA 2009, Edele et al. (2013), for instance, revealed the relationships between the reading competence of ninth-grade immigrant students and their acculturation patterns, which were obtained by conducting median-split on two ethnic identity scales. An analysis showed positive associations between reading competence and assimilation or integration, with assimilation not being inferior to integration. Using data from a national large-scale study and the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), Schotte et al. (2018) revealed the heterogeneous associations between ninth-grade immigrant students' mainstream and ethnic identification and their achievement in German and maths with variations across different outcomes and ethnic groups. Overall, the results do not give support to the integration hypothesis in terms of academic achievement. Further examinations using the NEPS database show associations between four distinct acculturation profiles and immigrant students' reading competence development (Thürer et al., 2021, 2023) or immigrant students' educational attainment in secondary school (Lilla et al., 2021). Across studies, immigrant students who are considered assimilated, exhibit school-related outcomes that are comparable or even exceeding native students. Overall, the findings of studies conducted in Germany provide ample evidence that, in the educational context of Germany, integration is no more adaptive than assimilation. Conversely, this means that not only the strong orientation toward the culture of the host country is relevant but also that the orientation toward the culture of origin itself entails disadvantageous effects. Consequently, orientation toward the culture of origin involves discriminatory circumstances that lead to disadvantages in the educational context.

Recent approaches in acculturation studies

It is problematic to draw the general conclusion that, in the German context, assimilation is superior to integration, separation, and marginalization in terms of educational adaptation of immigrant youth, given the results of a recent study empirically investigating acculturation profiles of ethnic minority adolescents in Germany. Jugert et al. (2020) investigated the acculturation profiles of identification, i.e., how ethnic minority adolescents combine their ethnic and national identities, in immigrant students from the two largest immigrant groups using latent profile analysis. The analysis identified four profiles in Turkish-origin students and three distinct profiles emerged in resettler-origin students. The dominant profile in both groups was students who strongly identified with both their origin and Germany (56.3% of the Turkish-origin and 49.4% of resettler-origin students); in line with Berry's typology, this profile was named integrated. The second prominent profile in both groups (28.7 and 27.0%) featured those who identified strongly with their origin but only weakly with Germany, a profile named separated following Berry's typology. For Turkish-origin students, two smaller profiles emerged: 11.3% of medium-level Turkish identification and medium-to-high levels of German identification, named medium-ethnic identifiers; and a small group of 3.6% who identified only very little with their Turkish origin and were diverse in their level of German identification were named low-ethnic identifiers. For resettler-origin students, a third profile (23.6%) featured students ranging on average on both national and ethnic identification, named medium- and low-ethnic identifiers. Similarly, a study focusing on psychological aspects of acculturation in Moroccan immigrants living in the Netherlands revealed three patterns of acculturation conducting latent class analysis (Stevens et al., 2004). Taken together, the results of these studies indicate that there are not necessarily four patterns of acculturation in any ethnic group of immigrant students but they do need to be congruent with the theoretically postulated four patterns. In particular, Jugert et al.'s (2020) study neither found a singular pattern of assimilation in the classic sense of high ethnic and high national identification in two relevant ethnic groups of immigrant students in Germany nor was there any profile indicative of a pattern of marginalization.

Revealing a number other than four is a finding that is not uncommon in studies empirically examining acculturation patterns using person-centered approaches, such as latent class analysis (LCA) or latent profile analysis (LPA). LCA and LPA are techniques used to empirically identify unobservable, or latent, classes within a population without making any pre-assumptions derived from theory. Acculturation studies from the US-American context, for instance, found between two and six distinct patterns of acculturation in samples of children and adolescents of Mexican origin (e.g., Matsunaga et al., 2010; Nieri et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2021) and Hispanic background (Schwartz and Zamboanga, 2008; Lee et al., 2020). In a sample of more than 200 US college students self-identifying as Asian American, Hispanic American, or African American, Fox et al. (2013) revealed three profiles of acculturation conducting LPA based on multiple-item measures, including cultural knowledge, behavior, and attitudes: integrated (40% of the sample), assimilated (43% of the sample), and separated (17% of the sample).

Because of their probabilistic nature, LCA and LPA not only offer a way to investigate patterns of acculturation within any sample without anticipating in advance. Latent class approaches also offer the possibility of operationalizing acculturation in a multidimensional manner since they allow for the inclusion of multiple aspects of acculturation. In this way, acculturation studies applying LCA or LPA can tie in with a multidimensional conceptualization of acculturation (e.g., Arends-Tóth and Vijver, 2006; Phinney et al., 2006). Following the notion that the acculturation experience includes multiple aspects that change through ongoing intercultural contact, Schwartz et al. (2010) call for an expanded perspective on acculturation that integrates the closely related literature on cultural values, cultural practices, and cultural identifications.

Given that a study by Ward and Kus (2012) found that different outcomes emerge when acculturation is operationalized in attitudinal terms instead of behavioral terms, it seems particularly essential to include multiple dimensions of acculturation when empirically examining the existence and prevalence of distinct acculturation patterns.

The present study

Against the background of the current state of research showing inconsistencies between theory and empirical findings, the present study sets out to capture patterns of acculturation in immigrant students in Germany conducting latent profile analysis. In contrast to Jugert et al. (2020)'s study, we investigated a heterogeneous sample of immigrant students from different ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, we refrained from a multidimensional conceptualization of acculturation including affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of acculturation. Affective aspects relate to the identification and feeling of belonging to both cultures, behavioral aspects relate to the practice of culture and traditions of the culture of origin, and cognitive aspects relate to the proportionate use of German or the language of origin in social interactions with mother, father, and siblings.

Specifically, the aim of the present study was to provide empirical knowledge addressing three research questions. First, what are the acculturation profiles among immigrant students in Germany (and how many)? Second, how are the acculturation profiles distributed among immigrant students in Germany? Third, what are the associations between acculturation profiles and individual characteristics such as gender, generational status, and ethnic group?

Method

In the present study, we used data from Starting Cohort 4 of the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS, NEPS Network, 2021),1 i.e., a comprehensive dataset assessing the educational trajectories of students all over Germany from Grade 9 onwards (total N = 16,425 at the first measurement point). A detailed description of the NEPS can be found in Blossfeld and Roßbach (2019). For this study, we used information from the student questionnaire that students completed at school in the fall/winter of 2010.

Sample

For our analysis, we selected students who attended regular schools (students attending special education schools were excluded from the analyses) and who were categorized as having an immigrant background as operationalized in the NEPS (i.e., first, second, and third generation; Olczyk et al., 2014). In total, the analysis sample comprised 5,778 immigrant students (51.6% girls) in Grade 9 who were born abroad themselves (7.2%), or who were born to at least one parent (63.8%) or grandparent (29.0%) born abroad. Students' age ranged between 11 and 20 years (M = 14.73, SD = 0.72). The major immigrant groups included a background in Turkey (n = 885), the Former Soviet Union (n = 732), Poland (n = 469), Former Yugoslavia (n = 394), and from North and Western Europe (n = 278).

Measures

Guided by theory and to capture the multidimensionality of acculturation, five scales (with a total of 16 items) were selected from the extensive database of the NEPS, which depict affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of cultural orientation.

German and ethnic identification

German and ethnic identifications were assessed using two items capturing the feeling of belonging to the host society and the society of origin (“How much do you yourself identify with the people from Germany//[this country] overall?”; Phinney, 1992) on a 5-point Likert scale [labeled from “not at all” (1) to “very strongly” (5)], with higher scores indicating stronger identification.

Feeling of connectedness to the German society and the society of origin

Two four-item scales using parallel wording captured students' feeling of connectedness toward the German society (e.g., “I feel closely connected to the people in Germany”) and the society of origin (e.g., “I feel closely connected to the people from this country”; Phinney, 1992). The answer options ranged from “does not apply at all” (1) to “applies completely” (4) on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating stronger feelings of connectedness. Cronbach's alphas were α = 0.90 and α = 0.93, respectively.

Heritage cultural habits

A three-item scale asked students about their cultural habits pertaining to the culture of origin (addressing listening to music, cooking, and celebrating public holidays), with answers ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5) on a 5-point Likert scale. Cronbach's alpha for heritage cultural habits was α = 0.72. A higher score on the scale indicates that heritage cultural habits are endorsed more strongly.

Family language use

Language use within the family context was assessed with three questions asking about the language used by the mother, the father, and the siblings. Answers were provided on a semantic differential from “German only” (1) to “the other language only” (4). Cronbach's alpha for language use was α = 0.78. Higher scores indicate that students rather speak another language than German when with their family members.

Analytical strategy

Analyses began by examining the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of the selected acculturation scales before z-standardizing all acculturation scales to account for different scaling. Next, latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted using Mplus 8.2 with the full maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method of handling missing data (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017). Following the general approach, LPA models were estimated in a sequential process starting with one profile and increasing the number of profiles stepwise until the comparison of the resulting fit indices to those of the previous profile solution showed no further significant improvement in model fit (e.g., Nylund et al., 2007).

Several statistical indicators that are commonly proposed to judge model fit and determine the correct number of distinct profiles were examined for each model (Nylund et al., 2007; Nylund-Gibson and Choi, 2018; Nylund-Gibson et al., 2022):

1. Information criteria, such as the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC), where lower values indicate better model fit;

2. The Lo–Mendell–Rubin (LMR) test and the parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) to compare the models. These tests provide significance tests on the probability that a k vs. k-1 class model fits better. If p-value is significant (p < 0.05), the k model is preferable; otherwise, the k-1 model is a better fit for the data.

3. Entropy measuring the overall classification quality and accuracy of the model, which ranges from 0 to 1.

In simulation studies, it has been shown that the BIC is the best predictor of the information criterion tests but that the BLRT is the best overall indicator for the correct number of classes or profiles (Nylund et al., 2007). However, according to Nylund-Gibson et al. (2022), entropy may be of primary importance, e.g., when membership in a particular class is used for diagnostic purposes.

After identifying the best-fitting model, each individual's most likely profile membership was determined, and the proportion of the sample in each latent profile was identified. Profiles were interpreted by examining their members' average agreement on every acculturation scale. Finally, differences in individual characteristics, namely gender, generation status, and ethnic group across the latent profiles identified were examined by running chi-square statistics.

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive and bivariate correlations for all variables used in the latent profile analysis. For all acculturation scales, the means showed to be above the scale midpoint. Students' German identification (1 host society identification) and identification with the society of origin (3 society of origin identification) showed to be rather strong on average. Similarly, students' feelings of connectedness on average showed to be similarly pronounced toward both cultures (2 and 4). On average, students showed strong endorsement of heritage cultural habits (5), and language use within the family (6) on average showed to slightly tend to another language than German. Bivariate correlations indicate that correlations among different aspects of acculturation exist and are in the expected directions, that is, scales pertaining to one culture were strongly positively correlated, and scales pertaining to different cultures were rather weak and negatively associated. For example, German identification was positively associated with belonging to German society (r = 0.63, p < 0.001) and negatively associated with heritage cultural habits (r = −0.31, p < 0.001).

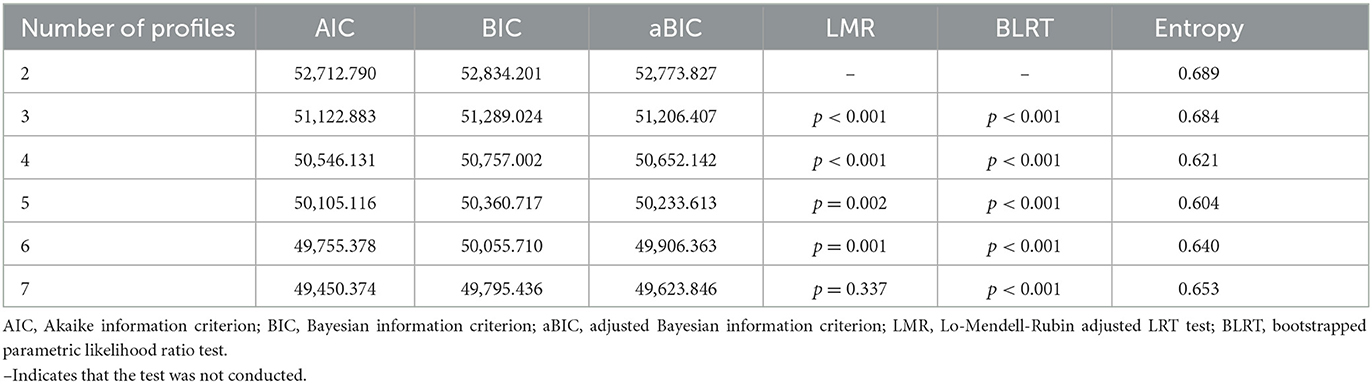

Number of latent acculturation profiles

Table 2 presents the model fit indices for the 2- to 7-profile solution. Latent profiles were estimated for 4,403 students. According to the information criteria (AIC, BIC, and aBIC), model fit increased steadily as the number of profiles increased. Following the Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (Vuong, 1989; Lo et al., 2001), the subsequent models had a better fit compared to the respective previous models, up until the seven-profile model, which did not show to be significantly superior compared to the six-profile model. Furthermore, entropy yielded to be higher for the six-profile solution, categorizing 64.0% of the sample uniquely to a specific acculturation profile (as opposed to only 60.4% in the five-profile solution). Hence, the six-profile solution was identified as the optimal model.

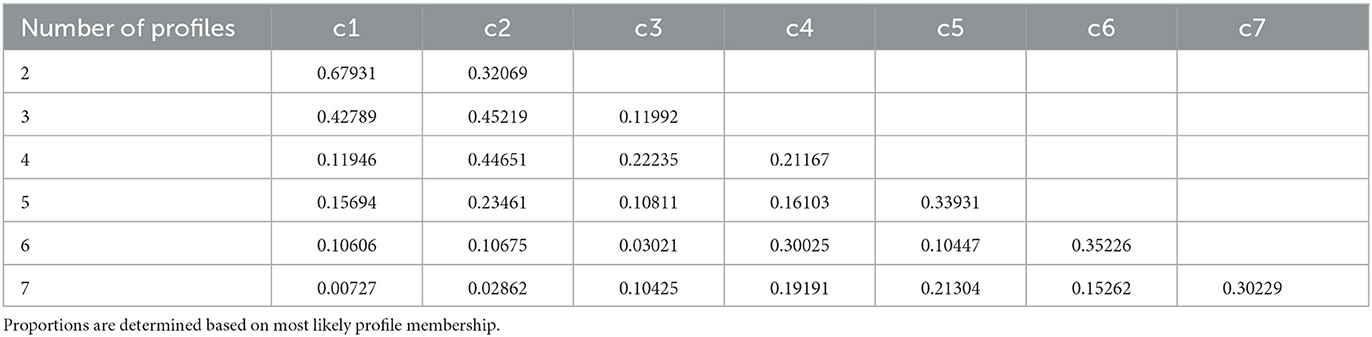

The final proportions of each profile up to the seven-profile model are displayed in Table 3. For the six-profile model, the prevalence of the two profiles was 35% (c6) and 30% (c4), three profiles comprising ~10% each (c1, c2, and c5), and one profile comprising 3% of the sample (c3).

Description of acculturation profiles

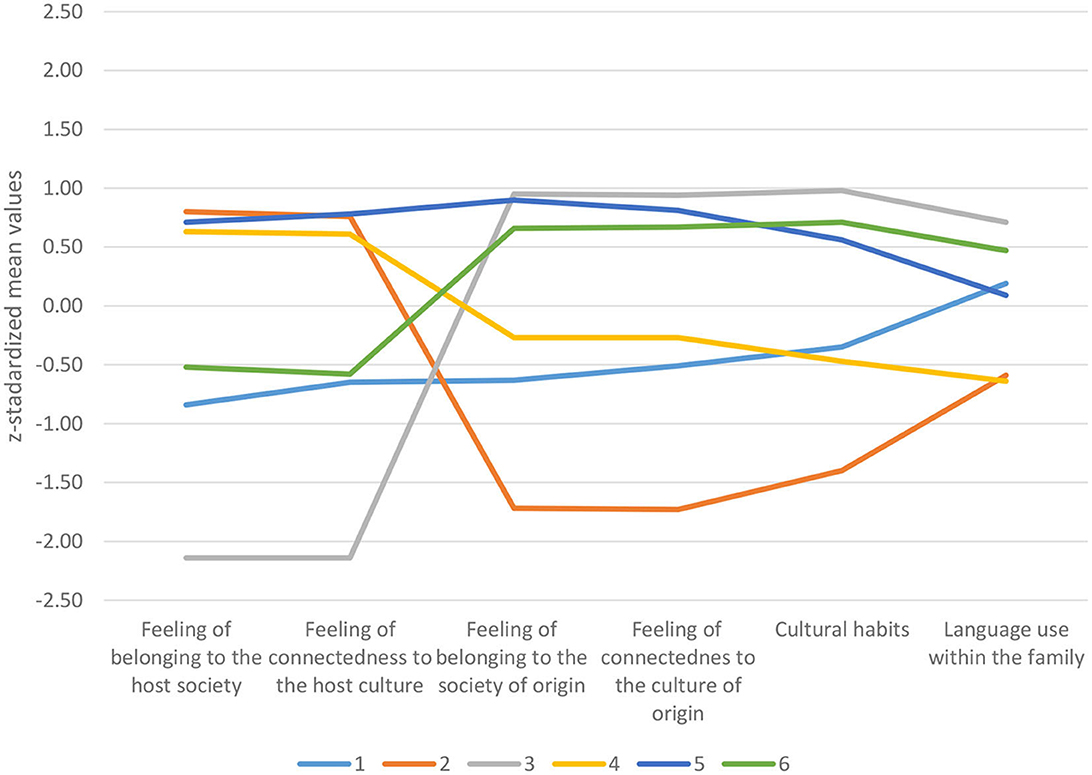

Following the statistical criteria suggesting the six-profile solution to represent the data best, this solution was inspected further. Figure 1 visually displays the average agreement on every acculturation scale by members of the identified latent profiles. Profiles are described in descending order of prevalence.

The largest profile (Profile 6, 35.2%) is characterized by slightly below-average endorsements of German identification and feeling of connectedness to the host culture, slightly above-average endorsement of ethnic identification and feeling of connectedness to the origin culture, above-average scores on heritage cultural habits, and language use other than German within the family (M = 0.47). Following Berry's typology, this profile was named separation. The second most prevalent profile (Profile 4, 30.0%) on the opposite is characterized by slightly above-average scores on German identification and feeling of connectedness to host culture, slightly below-average scores on ethnic identification and feeling of connectedness to the origin culture, below-average endorsement of heritage cultural habits, and a tendency toward German language use within the family (M = −0.64). This profile was named assimilation. Profile 2, encompassing 10.7%, is characterized by a relatively strong agreement regarding German identification and feeling of connectedness to the host culture, while, at the same time, showing an even lower level of endorsement of national identification and feeling of connectedness to the origin culture than Profile 4, the lowest mean on heritage cultural habits, and an equally low endorsement of using another language than German within the family. Accordingly, this profile was named strong assimilation. Profile 1, which entails 10.6% of the sample, is characterized by below-average endorsement of German identification and feeling of connectedness to the host culture and, simultaneously, below-average endorsement of ethnic identification and feeling of connectedness to the culture of origin, as well as below-average endorsement of heritage cultural habits. Mean language use within the family is slightly above the sample mean, which speaks to a tendency to use a language other than German within the family to a greater extent. In line with Berry's typology, this profile was named marginalization.

Profile 5, encompassing 10.4% of the sample, is characterized by high scores on German identification and feeling of connectedness to the host culture, as well as ethnic identification and feeling of connectedness to the origin culture, and shows above-average endorsement of heritage cultural habits and just above-average scores for language use within the family indicating a tendency to use languages other than German within the family. This profile was named integration. The smallest profile (Profile 3), encompassing only 3.0%, is characterized by the lowest scores regarding German identification and feeling of connectedness to the host culture, while, at the same time, showing the highest scores regarding ethnic identification and feeling of connectedness to the society of origin, the strongest endorsement of heritage cultural habits, and the highest mean values for using another language than German within the family as compared to all other profiles. Again, following Berry, this profile was named strong separation.

Individual characteristics of acculturation profiles

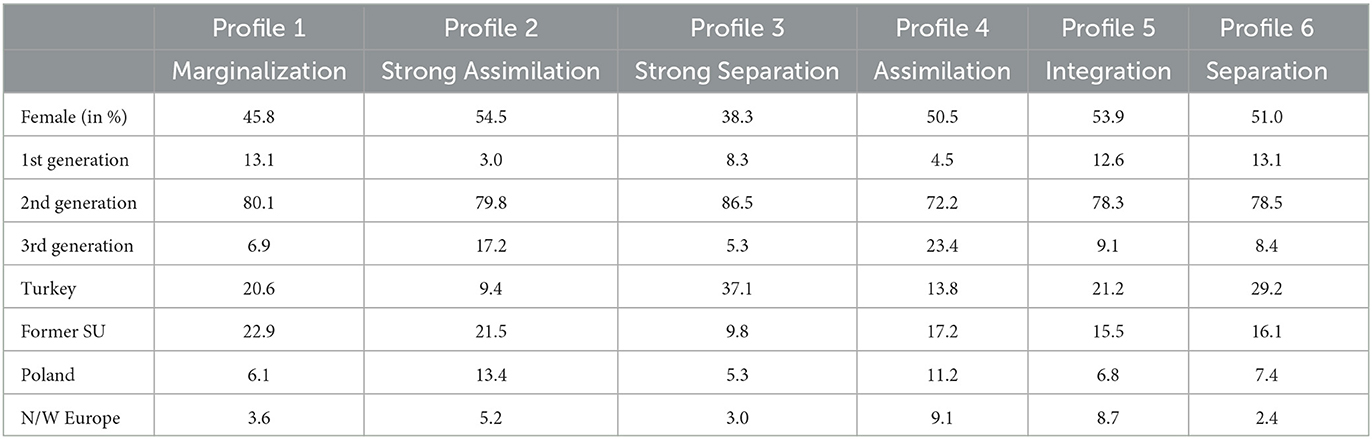

Profiles were inspected for differences in selected individual characteristics. Table 4 shows the distribution of the six acculturation profiles which emerged from latent profile analysis in relation to immigrant students' gender, generation status, and ethnic group.

The proportion of boys and girls differed significantly across profiles [ = 17.17, p < 0.01], with girls more often showing the strong assimilation profile and the integrated profile and boys the strong separation profile. Acculturation profiles were significantly related to generation status, = 255.04, p < 0.001. First-generation immigrant students, i.e., students born abroad, showed to be overrepresented in the marginalization profile and the separation profile and also in the integration profile. Second-generation immigrant students were overrepresented in the strong separation profile, while third-generation immigrant students accumulated in the strong assimilation and assimilation profiles. Regarding ethnic groups, chi-square analysis of the six profiles by the five biggest ethnic groups (Turkey, Former Soviet Union, Poland, Former Yugoslavia, and North and Western Europe) was significant, = 235.66, p < 0.001. Immigrant students whose ethnic identification group was Turkish predominated in the strong separation profile and separation profile. Descendants from the Former SU accumulated in the marginalization profile and the strong assimilation profile. Immigrant students with Polish heritage prevailed in the strong assimilation profile, and students from North and Western Europe were mainly found to belong to the assimilation or the integration profile.

Discussion

The current study examined the acculturation patterns of immigrant students in Germany by considering multiple aspects of acculturation in latent profile analysis. Furthermore, the prevalence of distinct acculturation patterns and their distribution in relation to selected demographics (gender, generation status, and ethnic group) was inspected. Following the notion of a multidimensional operationalization of acculturation (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2010), items that represent affective, behavioral, and cognitive domains of cultural orientation toward the host and origin society were selected from a comprehensive dataset of ninth-grade immigrant students of different heritage living in Germany.

Based on Berry (1997), acculturation has traditionally been classified into four patterns based on the orientation toward the culture of the country of origin and the orientation toward the people and culture of the receiving country: integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization. The results of the current study empirically revealed six distinct patterns of acculturation which were interpreted with reference to Berry's model as showing an integration profile, two assimilationist profiles, two separationist profiles, and one marginalization profile. The integration profile showed agreements on all scales above average. The assimilationist profiles included one profile of assimilation with relatively strong agreement toward Germany and below-average agreement on all other heritage culture-related scales, and a pattern of strong assimilation with comparable agreement toward German culture but rather a weak agreement to heritage culture scales. The separationist profiles included one separation profile with relatively weak agreement toward German culture and above-average agreement on all other heritage culture-related scales and a pattern of strong separation with extra weak agreement toward German culture and even slightly more pronounced agreement to heritage culture scales. The marginalization profile showed agreements below average on all scales—except for language use within the family scale. In contrast to Jugert et al. (2020) whose latent profile analyses revealed four distinct patterns of ethnic identification in Turkish-origin youths and three distinct patterns of ethnic identification in resettler-origin youths living in Germany, the current study identified six distinct profiles of acculturation in a heterogeneous sample of immigrant students living in Germany. Deviations in terms of a number of distinct acculturation profiles and multiple variants of one or more of the Berry categories have been found also in previous studies conceptualizing acculturation multidimensionally and conducting latent profile analysis (e.g., Schwartz and Zamboanga, 2008). Furthermore, the results showed that the separated profile was the most prevalent (35%), followed by ~30% of the sample with an assimilated profile. Furthermore, 11% of the sample was in the strong assimilation profile. The integrated profile and the marginalized profile each encompassed approximately 10% of the sample. Finally, only 3% of the sample built a strong separation profile. In contrast to Berry's (2006) study, which found that the majority of migrant adolescents were in either the integration or ethnic profile, our findings showed that the integrated profile comprised only 10% of immigrant students in our sample. This was also surprising since Jugert et al. (2020) found that the integrated profile of identification was the dominant profile both among Turkish-origin and resettler-origin students living in Germany.

Taking a closer look at individual characteristics revealed that, in the current sample, immigrant students with a Turkish background were overrepresented in the separation and strong separation profiles and students from the Former Soviet Union clustered in the strong assimilation and the marginalization profile. One possible explanation could be the multidimensional operationalization and the impact of behavioral aspects of acculturation. While Jugert et al. (2020) employed measures of ethnic and national identification only, the inclusion of behavioral aspects in our study possibly shows the contribution of heritage cultural habits and family language use in describing the acculturation experience more thoroughly. Further expanding the approach could also allow for the consideration of social dimensions or experiences of discrimination. Interestingly, there were some further significant associations worth highlighting: For instance, integration showed to be associated with female sex, while the male sex was overrepresented in strong separation and marginalization. Furthermore, there was a significant association between integration and first-generation status. This finding contradicts the often-formulated assumption that immigrants become increasingly (more) integrated the longer they reside in the country of residence. Our findings showed that especially third-generation immigrant students accounted for the assimilation and strong assimilation profiles, speaking for the fact that Germany is a context with strong pressure for assimilation (Zick et al., 2001).

Finally, immigrant students' ethnic backgrounds showed to be associated with acculturation profile in the inspected sample: While integration was associated with north and western European background, strong assimilation was more common among Polish descendants and Former SU descendants, but (strong) separation was mostly characterized by Turkish-origin immigrant students and students from the Former Soviet Union clustered in the strong assimilation and the marginalization profile. This unequal distribution gives a picture of different prevalences of acculturation patterns in different ethnic groups, which can be interpreted as relating to their ethnic group, and the social inequality and discrimination they experience. It is important to note that this unequal distribution is not only to be interpreted as showing different acculturation choices but also hint at the fact that different ethnic groups face different opportunities and challenges and different expectations for acculturation posed to them by the societal climate. In addition, associations and possible interdependencies with other categories not considered in this study, e.g., religion or socio-economical background, are more than likely. Future studies should include other categories to further and systematically broaden the view on acculturation. Taken together, the current study contributes to the state of acculturation research on immigrant students in Germany. By looking at the acculturation of immigrant students including multiple aspects of acculturation, the study can help to reflect on the educational experiences and achievements of immigrant students, and importantly, contributes to a more thorough understanding and consideration of the plurality of immigrant students' experiences. This study goes beyond the analyses available from the work of other authors by estimating the acculturation profiles of immigrant students with latent profile analyses, which are less limited by theoretical assumptions and have a higher statistical significance than deterministic cluster analyses. Several LPA models were estimated to empirically identify the number of profiles that best describe distinct acculturation profiles among a heterogeneous sample of immigrant students and their distribution across different demographic groups was examined.2

Interpreting the results, it must be kept in mind that all analyses have been conducted with a non-representative sample. Consequently, findings cannot be generalized and no statement can be made about the population of immigrant students. The NEPS database allowed investigation of a heterogeneous sample including immigrants pertaining to different ethnic groups. With this approach, the distribution of distinct empirically determined acculturation profiles across ethnic groups was shown. A limitation of the chosen approach, however, is that no statements about the emergence of distinct acculturation patterns within a specific ethnic group could be made. It must further be noted that the same analysis with more recent data, containing groups of newly migrated groups to Germany, might show a very different picture of acculturation. Regarding the multidimensional operationalization of acculturation, there were some restrictions to the scales. We aimed to include scales that cover affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of acculturation pertaining to German culture and heritage culture. For instance, the NEPS database did not allow for the inclusion of a behavioral scale pertaining to German cultural habits. Without these restrictions, a number of further scales could have been included to further broaden the perspective on immigrant students' acculturation.

Given this, this study provides numerous starting points for future acculturation research. Future acculturation studies using latent profile analysis could expand the acculturation experiences by, for instance, including further relational and social dimensions such as experiences with discrimination and/or social inequality indicators. In this vein, it could also be a reasonable approach to conduct separate profile analyses for homogeneous ethnic groups. To conclude, with this study, an approach that is suitable to capture the multidimensionality of acculturation before investigating their associations with school-related outcomes more thoroughly was demonstrated. The method allows for the empirical identification of distinct acculturation patterns without pre-assumptions on the number of acculturation profiles and distribution across patterns. Hence, future studies investigating the link between acculturation and school adjustment of immigrant students should consider using LPA for the identification of acculturation patterns before investigating their potential adaptivity instead of using Berry's 4-fold model as a rigid template for categorizing immigrant students into one of the four acculturation patterns. In addition, school-related experiences such as perceived discrimination by teachers or peers could be included to obtain a more comprehensive perspective on immigrant students' acculturation experiences. Last but not least, the study contributes to reflecting on the school experiences and educational achievements of immigrant students, and, most importantly, to help to understand and account for the complexity and diversity of immigrant students' experiences.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available—access to the NEPS data requires the completion of a Data Use Agreement with the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi).

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) allocated to NL as principal investigator (grant number: LI 3067-1/1) conducted within the Priority Programme 1646: Education as a Lifelong Process. Further support by the Open Access Publication Initiative of Freie Universität Berlin is acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This study uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS; see Blossfeld and Roßbach, 2019). The NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LifBi, Germany) in cooperation with a nationwide network.

2. ^Inspecting the resulting six acculturation profiles revealed two different versions of assimilation and two different versions of separation, with the strong separation profile accounting for only 3% of the sample. Following Nylund et al. (2007), the number of participants in each profile should be more than 5% of the sample size, and besides statistical criteria, the theoretical meaning of each profile should be further considered as an important criterion for selecting the best solution and determining the number of distinct profiles. Accordingly, it seems reasonable to also discuss more parsimonious profile solutions: Given that the fit indices of the five-profile solution were not convincing—especially with regard to the accuracy of the model—the four-profile solution seems next best. In previous examinations of the current database, the four-profile solution has been examined to stay more in line with Berry's (1997) four-fold acculturation model: Three profiles were interpreted in line with Berry's model, as assimilation, integration, and separation. Instead of a marginalization profile, the fourth profile showed a pattern of indifference. The four-profile solution has been described more thoroughly in previous publications, please refer to the Thürer et al. (2021).

References

Arends-Tóth, J., and Vijver, F. J. R. (2006). “Issues in the conceptualization and assessment of acculturation,” in Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships: Measurement and Development, eds M. H. Bornstein and L. R. Cote (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 33–62. doi: 10.4324/9780415963589-3

Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (2016). Bildung in Deutschland 2016: Ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zu Bildung und Migration. wbv. Bielefeld.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 46, 5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., and Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 55, 303–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x

Bierwiaczonek, K., and Kunst, J. R. (2021). Revisiting the integration hypothesis: correlational and longitudinal meta-analyses demonstrate the limited role of acculturation for cross-cultural adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 32, 1476–1493. doi: 10.1177/09567976211006432

Blossfeld, H. P., and Roßbach, H. G. (2019). Education as a Lifelong Process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), 2nd Edn. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Edele, A., Stanat, P., Radmann, S., and Segeritz, M. (2013). Kulturelle Identität und Lesekompetenz von Jugendlichen aus zugewanderten Familien, (Beiheft: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik), 59, 84–110.

Fox, R. S., Merz, E. L., Solórzano, M. T., and Roesch, S. C. (2013). Further examining berry's model: the applicability of latent profile analysis to acculturation. Measur. Eval. Counsel. Dev. 46, 270–288. doi: 10.1177/0748175613497036

Fuligni, A. J., and Tsai, K. M. (2015). Developmental flexibility in the age of globalization: autonomy and identity development among immigrant adolescents. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 66, 411–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015111

Jugert, P., Pink, S., Fleischmann, F., and Leszczensky, L. (2020). Changes in Turkish- and resettler-origin adolescents' acculturation profiles of identification: a three-year longitudinal study from Germany. J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 2476–2494. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01250-w

Lee, T. K., Meca, A., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., Gonzales-Backen, M., et al. (2020). Dynamic transition patterns in acculturation among hispanic adolescents. Child Dev. 91, 78–95. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13148

Lilla, N., Thürer, S., Nieuwenboom, W., and Schüpbach, M. (2021). Assimiliert – Abitur, separiert – Hauptschulabschluss? Zum Zusammenhang zwischen Akkulturation und angestrebtem Schulabschluss. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 24, 571–592. doi: 10.1007/s11618-021-01004-9

Lo, Y., Mendell, N., and Rubin, D. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 88, 767–778. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2673445

Makarova, E., and Birman, D. (2015). Cultural transition and academic achievement of students from ethnic minority backgrounds: a content analysis of empirical research on acculturation. Educ. Res. 57, 305–330. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2015.1058099

Matsunaga, M., Hecht, M. L., Elek, E., and Ndiaye, K. (2010). Ethnic identity development and acculturation: a longitudinal analysis of Mexican-Heritage Youth in the Southwest United States. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 41, 410–427. doi: 10.1177/0022022109359689

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus User's Guide (Eighth Edition). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

NEPS Network (2021). National Educational Panel Study, Scientific Use File of Starting Cohort Grade 9. Bamberg: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi).

Nguyen, A. M. D., and Benet-Martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 44, 122–159. doi: 10.1177/0022022111435097

Nieri, T., Lee, C., Kulis, S., and Marsiglia, F. F. (2011). Acculturation among Mexican-heritage preadolescents: a latent class analysis. Soc. Sci. Res. 40, 1236–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.02.005

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., and Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a monte carlo simulation study. Struct. Eq. Model. 14, 535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396

Nylund-Gibson, K., and Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Iss. Psychol. Sci. 4, 440–461. doi: 10.1037/tps0000176

Nylund-Gibson, K., Garber, A. C., Singh, J., Witkow, M. R., Nishina, A., and Bellmore, A. (2022). The utility of latent class analysis to understand heterogeneity in youth coping strategies: a methodological introduction. Behav. Disord. 2022, 19874292110672. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/t8ver

Olczyk, M., Will, G., and Kristen, C. (2014). Immigrants in the NEPS: Identifying Generation Status and Group of Origin (NEPS Working Paper No. 41a). Bamberg: Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, National Educational Panel Study.

Phalet, K., and Baysu, G. (2020). Fitting in: how the intergroup context shapes minority acculturation and achievement. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 31, 1–39. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1711627

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure. J. Adolesc. Res. 7, 156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003

Phinney, J. S., Berry, J. W., Vedder, P., and Liebkind, K. (2006). “The acculturation experience: attitudes, identities and behaviors of immigrant youth,” in Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition: Acculturation, Identity, and Adaptation Across National Contexts, eds J. W. Berry, J. S. Phinney, D. L. Sam, and P. Vedder (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 71–116. doi: 10.4324/9780415963619-4

Redfield, R., Linton, R., and Herskovits, M. J. (1936). Memorandum for the study of acculturation. Am. Anthropol. 38, 149–152. http://www.jstor.org/stable/662563 doi: 10.1525/aa.1936.38.1.02a00330

Sam, D. L., and Berry, J. W. (2010). Acculturation: when individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. A 5, 472–481. doi: 10.1177/1745691610373075

Schachner, M. K., He, J., Heizmann, B., and van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2017). Acculturation and school adjustment of immigrant youth in six European countries: findings from the programme for international student assessment (PISA). Front. Psychol. 8, 649. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00649

Schotte, K., Stanat, P., and Edele, A. (2018). Is integration always most adaptive? The role of cultural identity in academic achievement and in psychological adaptation of immigrant students in Germany. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 16–37. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0737-x

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., and Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am. Psychol. 65, 237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330

Schwartz, S. J., and Zamboanga, B. L. (2008). Testing Berry's model of acculturation: a confirmatory latent class approach. Cult. Div. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 14, 275–285. doi: 10.1037/a0012818

Searle, W., and Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 14, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

Stevens, G. W. J. M., Pels, T. V. M., Vollebergh, W. A. M., and Crijnen, A. A. M. (2004). Patterns of psychological acculturation in adult and adolescent moroccan immigrants living in the Netherlands. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 35, 689–704. doi: 10.1177/0022022104270111

Thürer, S., Lilla, N., Nieuwenboom, W., and Schüpbach, M. (2021). Individuelle und im Klassenkontext vorherrschende Akkulturationsorientierung und die individuelle Lesekompetenz von Schülerinnen und Schülern der 9. Klasse. J. Educ. Res. Onl. 2021, 62–83. doi: 10.31244/jero.2021.02.04

Thürer, S., Nieuwenboom, W., Schuepbach, M., and Lilla, N. (2023). Immigrant students' acculturation profile and reading competence development in secondary school and beyond. Int. J. Educ. Res. 118, 102139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102139

Vuong, Q. (1989). Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica. 57, 307–333.

Ward, C., and Kus, L. (2012). Back to and beyond Berry's basics: the conceptualization, operationalization and classification of acculturation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 36, 472–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.02.002

Yan, J., Sim, L., Schwartz, S. J., Shen, Y., Parra-Medina, D., and Kim, S. Y. (2021). Longitudinal profiles of acculturation and developmental outcomes among Mexican-origin adolescents from immigrant families. N. Direct. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 205–225. doi: 10.1002/cad.20396

Keywords: acculturation, latent profile analysis, international migration, receiving-culture orientation, heritage-culture orientation, secondary analysis

Citation: Lilla N (2023) Capturing the multidimensionality of immigrant students' acculturation patterns in Germany. Front. Educ. 8:1129407. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1129407

Received: 21 December 2022; Accepted: 20 June 2023;

Published: 03 August 2023.

Edited by:

Kerstin Göbel, University of Duisburg-Essen, GermanyReviewed by:

Pedro Daniel Ferreira, University of Porto, PortugalKaterina M. Marcoulides, University of Minnesota, United States

Copyright © 2023 Lilla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nanine Lilla, bmFuaW5lLmxpbGxhQGZ1LWJlcmxpbi5kZQ==

Nanine Lilla

Nanine Lilla