- 1Faculty of Psychology and Education Science of the University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 2Center for Psychology at University of Porto (CPUP), Porto, Portugal

The number of PhD graduates has been increasing yearly, but the job opportunities in Academia remain the same. This pattern will intensify the pressure on PhD students to look for other possible careers. Past work experiences, due to their developmental potential, occupy a prominent place in the career development paradigm. However, more is needed to know about the professional path of PhD students before they entered the PhD. This study aimed to explore PhD students’ previous professional experience, focusing on the extent to which previous experiences determine students’ perception and development of career expectations. A quantitative research approach was followed among 377 PhD students at a Portuguese Higher Education Institution (HEI). Results show that regardless of their previous work experiences, PhD students value career options related to research, preferably within Academia. However, in terms of career development, students who have diverse work experiences reported feeling more prepared to put into practice actions to prepare their career than students with professional experience in Academia or no professional experience. This study confirms that PhD students’ previous work experiences pay off by making a difference in the feeling of preparedness for career development, whereas in terms of student’s future career expectations after the PhD, it did not allow for a definite answer, as it seems that all professional groups prefer similar research-oriented paths. Intervention must be done simultaneously on an individual and contextual level, allowing students to have experiences during the PhD and promoting the reflection on these experiences so students may feel more prepared to develop their future careers. For companies, intervention should focus on showing the PhDs’ added value and also the potential of incorporating the R&D dimensions within their jobs. Failing to do so may contribute to enhancing the employability challenges faced by the growing number of PhD holders.

1. Introduction

PhD holders have been identified as key stakeholders in promoting innovation and research to develop a knowledge-based society (Auriol et al., 2013; Afonja et al., 2021). They are a population that has made a career investment in pursuing a specialized degree. However, their career challenges rise as their numbers also rise. In OECD countries, only 1.1% of the population holds a Doctoral degree (OECD, 2019). Nevertheless, there has been a tendency for this number to increase over the years (OECD, 2019; WEF, 2019). Similarly in Portugal, the number of PhD students has been increasing remarkably, from 3.381 students in 2000 to 21.763 in 2020 (DGEEC, 2020).

According to OECD (2019, 2020, 2021) data, on average PhD students are around 29 years old at the moment of enrolment in the Doctoral Program, with 60% of students enrolling between the ages of 26 and 37. In Portugal, the scenario is slightly different, as students take longer to enter a Doctoral Program and tend not to enroll before the age of 30 (OECD, 2019). This situation suggests that these PhD students may value opportunities to gain work experience in industry or specific sectors that they can take advantage of in their research during the PhD (OECD, 2019). However, there is a scarcity of information on the PhD students’ professional experience and background on nationwide reports that can provide insights into the types of experiences, professional or not, the students may be developing before enrolling in the PhD.

Focusing on the employability of PhD holders, statistics identify that their employment rate is very high, over 90% in both OECD and Portugal (OECD, 2021). In terms of PhD holders’ careers, Higher Education Institutions (HEI) have been the traditional career destination (Eurostat, 2017; OECD, 2019; DGEEC, 2021), particularly in research-related jobs. More than half of the PhD holders in all European countries have been employed as researchers, mainly in HEI, followed by the Public Administration and then the Private Sector (Eurostat, 2017). This is also the scenario found in the Portuguese context, where HEI are the main PhD holders’ employers, with 77% of PhD holders working in an HEI, followed by Public Administration (13%), the Private Sector (8%), and the Social Solidarity Sector (2%) (DGEEC, 2021).

Given their high overall employment rate, the employability of PhD holders does not seem to imply any challenges to the career development of this highly specialized population segment. However, a thorough analysis of the characteristics of this employment reveals implicit challenges to the PhD holders’ career paths. As a sector that does not tend to expand or renew itself rapidly, Academia offers limited opportunities for stable employment to PhD holders (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; der Boon et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018; Sherman et al., 2021).

Some HEIs have been working to develop Doctoral Programs that prepare their students to occupy different job positions and contribute to the production of knowledge in various sectors. However, there is a tendency for Doctoral Programs to continue directing their curriculum to prepare students for traditional academic-related careers (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; der Boon et al., 2018; Jones, 2018; Bitušíková and Borseková, 2020). Within Doctoral Programs, supervisors also seem to have an impact on this tendency because their own experience is academic-centered (Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Sherman et al., 2021), which makes them recognize not having sufficient knowledge to keep students updated on skills and careers outside Academia (Watts et al., 2019). This context, associated with the growing number of PhD students and graduates, and the higher competitiveness for Academia positions (Sherman et al., 2021), indicates that some PhD students are led to seek an alternative career without having the support to prepare for this choice within Academia.

1.1. Career development, a paradigm designed from (one’s) past to present and future

The career development paradigm can be described as a complex process representing the everchanging dynamic of career work behavior, designed throughout the individual’s lifespan, from childhood to retirement (Savickas et al., 2009; Lent and Brown, 2021; Savickas, 2021). It is a construct that includes – and is shaped by – the individual’s wide range of formal and informal experiences, interests, values, and knowledge of the world of work. These factors are developed throughout the individual’s diverse life experiences (Lent and Brown, 2021; Savickas, 2021) in interaction with the environment, context, and others (Clot, 1999; Savickas, 2021). Career development is not a solely individual project but a social process whose construction depends on individual-context interactions (Savickas, 2021), with a particular focus on the opportunities that the latter provides to the individual’s development (Coimbra et al., 1994).

In this scope, it becomes relevant to focus on the value of previous experiences as a resource for career development preparation. Literature identifies the importance of having several different work experiences as a first step that will broaden the range of choices one can make when investing in career development (Coimbra et al., 1994). Based on the principle that one can only like and choose career paths based on what one knows and understands through previous work experiences (Ouvrier-Bonnaz and Verillon, 2002), it is fundamental to experience diverse work situations and contexts to ensure a more significant number of known possibilities for the development of a career path (Percy and Kashefpakdel, 2018; Bersin and Sanders, 2019).

Work experiences are central to career development, as it is composed of a string of choices, where work experience plays a role before, during, and after each career choice that forms one’s singular path (Lent and Brown, 2021). It is acknowledged that all individuals have a historical journey of experiences throughout their lives and that each journey in its singularity comprehends a potential for future development (Vygotski, 1997) that shapes one’s path of development (Clot, 1999). This positioning supports the lens used in this study, which centers the analysis on the value of the individuals’ previous experience for the construction of their career development.

1.2. The career development of PhD students

Although over time more attention has been given, by scholars and practitioners, to undergraduates, as a group who face graduation as their first career milestone (Ng and Feldman, 2007), typically associated with an intensified experience of labor market integration (Clarke, 2018; Felaco and Parola, 2020). PhD students, even though they represent an older segment (OECD, 2019), also face challenges posed by an intensified career transition after graduating. Students claim to need more information about the various sectors of employment and careers for their field of study and not knowing the skills required by positions outside Academia (Thiry et al., 2015). Those who follow a career outside Academia feel less prepared than those who follow an academic career (Boman et al., 2017, 2021).

The career development paradigm values the need to expand knowledge to make career choices (Coimbra et al., 1994; Bersin and Sanders, 2019; Lent and Brown, 2021; Savickas, 2021). Such assumption gains particular importance in the case of PhD holders and students, due to their highly specialized profile that can contribute to innovation and development of different sectors, where promoting their career development can be seen as directly enhancing their future contributions to society as graduates (Afonja et al., 2021).

The importance of having previous career experiences is supported by recent findings with college students which identify that developing career exploration activities and actions positively influences their career planning preparedness (Zhang et al., 2022). When focusing on PhD students and their work experience, there seems to be a scarcity of studies focused on the career expectations of PhD students that consider their professional experience prior to enrolling in the Doctoral Program. Nevertheless, the future career expectations of PhD students are a topic of research interest, with findings showing contradictory perspectives. Some studies show that students prefer research-related positions within Academia, followed by research positions in the Corporate/Industry Sector (Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Kim et al., 2018; Lauchlan, 2019; Cornell, 2020). Other findings identify a higher preference for non-academic careers (Sherman et al., 2021), with the students who consider several career paths (research and non-research careers) outnumbering those who prefer a singular traditional academic career path (Fuhrmann et al., 2011).

Conversely, studies that reflect on PhD students’ previous professional experience are focused on mature-aged students (considering only 35+ year-old students) (Templeton, 2021) and mainly explore their motives for enrolling in the PhD (Stehlik, 2011; Templeton, 2021), disregarding the analysis of the value of these students’ professional experience for their career path beyond the moment of entry in the PhD. Consequently, there is a need for an approach that focuses on the students’ experience to shape their career expectations for after the PhD.

Studies (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Kim et al., 2018; Sherman et al., 2021) focused on PhD students’ future career expectations consider the PhD as the starting point for their professional career. On the other hand, studies (Stehlik, 2011; Templeton, 2021) that consider the student’s past work experience approach the PhD as a culmination point of the student’s career. In this sense, this study also aims to address this gap, positioning the PhD as an event supported by students’ previous career development experiences and presenting an investment on the student’s behalf in their future career development.

Considering the employability challenge of PhD holders, the relevance of work experience in the development of careers (Coimbra et al., 1994; Ouvrier-Bonnaz and Vérillon, 2002; Bersin and Sanders, 2019; Lent and Brown, 2021; Savickas, 2021), and the perceived lack of studies on the role this experience plays in the career of PhD students, our research questions focus on to what extent PhD students with diverse professional experience backgrounds: (1) will present diverse career expectations for after the conclusion of the PhD? and (2) will feel more prepared to develop career development actions than the students with less diverse career backgrounds?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and data collection procedure

An exploratory quantitative study was conducted as part of an action-research project focused on the career development of PhD students at a Portuguese HEI.

Data was collected via a questionnaire developed on Qualtrics. Participating students gave their informed consent before starting to complete the questionnaire. The informed consent and questionnaire included contributions from the Data Protection Committee of the HEI to ensure that the anonymity of the PhD students was guaranteed through the data collection process.

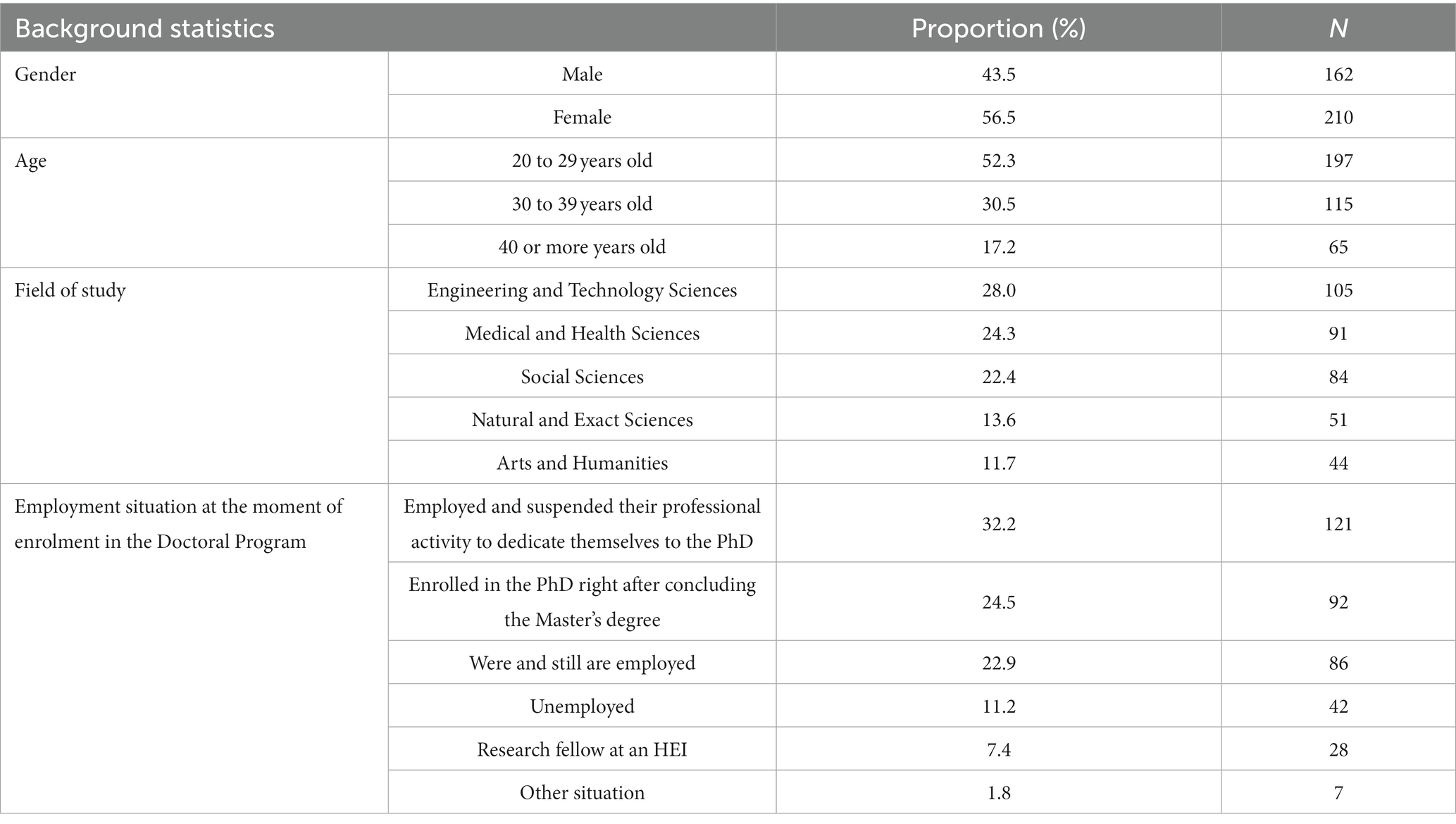

The data collection process occurred from October 20 to November 20, 2021. The questionnaire was sent via institutional e-mail through Employability Services to all students enrolled in Doctoral Programs at the HEI. A total of 388 responses were gathered. After incomplete responses were excluded, 377 complete questionnaires were used for the scope of analysis. The final number of participants represents 10.2% of the total PhD student population enrolled at the HEI. The demographic characteristics of the students’ sample are shown in Table 1. Considering the students’ professional experience, which comprehends the groups of analysis for this study, four types of professional experience were identified: “Exclusively in the Academia context” (29.2%; N = 110); “Exclusively in the Corporate context (21.0%; N = 79): “In more than one context (Academia, Corporate and/or Public Administration) (42.4%; N = 160); and “No professional experience” (7.4%, N = 28).

2.2. Measures and data analysis procedure

A questionnaire was developed specifically for this study. This decision was deliberate and supported by the difficulty to identify a scale that approached the previous work experience dimension, which confirms the differentiating scope of this study. For the student characterization items, data was collected regarding gender, age group, field of study, and professional background. The question about the student’s identification of their professional experience background was divided into four types of choices to construct the groups of analysis: exclusively in the Academia context; exclusively in the corporate context; experience in more than one context (aimed to consider mixed experiences in the contexts of Academia, Corporate and/or Public Administration); and lastly, to not having professional experience.

Career expectations after the conclusion of the PhD were assessed through a question designed to allow for multiple-selection, where students could select more than one career expectation. This design decision was based on the purpose of presenting the question in a format that would not narrow the students’ choices of perspectives, supported in the career development principles that individuals have several future career possibilities they can make (Coimbra et al., 1994; Savickas, 2021). This question included ten options (e.g., be hired as a researcher by a HEI/Research Center, as a professor at a HEI; be hired by a company in the R&D area, by a company in non-R&D area; or conduct post-doc studies) that resulted from the literature review (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Kim et al., 2018; Lauchlan, 2019; Cornell, 2020; Sherman et al., 2021) and interviews with stakeholders of the HEI. These interlocutors were involved due to their different roles performed in relation to the scope of the study. The items in this question were developed on Qualtrics to appear randomly.

The final segment of the questionnaire included a set of 13 questions aimed at assessing the students’ perceptions about their: preparedness to identify experiences and goals; constraints for integration in the labor market; ability to outline actions toward the design of their career path; and confidence to influence the career path and achieve their professional goals. All items were presented on a five-point Likert scale, where one meant “strongly disagree” and five meant “strongly agree.”

Data was analyzed through IBM SPSS Statistics 27, where descriptive, frequency, and group distribution analyses were conducted. An analysis of the frequencies of the students’ selected items was conducted to determine which future career expectations were identified the most by the PhD students according to their professional experience background. To analyze if there were significant differences on the student’s perceptions of preparedness to take career development actions according to the professional experience background, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the distribution of the groups on each item, in substitution of a One-way ANOVA, since the professional groups have different sizes and the Shapiro–Wilk test used to test the normality of the variables identified that all 13 items did not follow a normal distribution (W(376) = 0.76 to 0.91, p = <0.001).

3. Results

3.1. Career expectations after the conclusion of the PhD

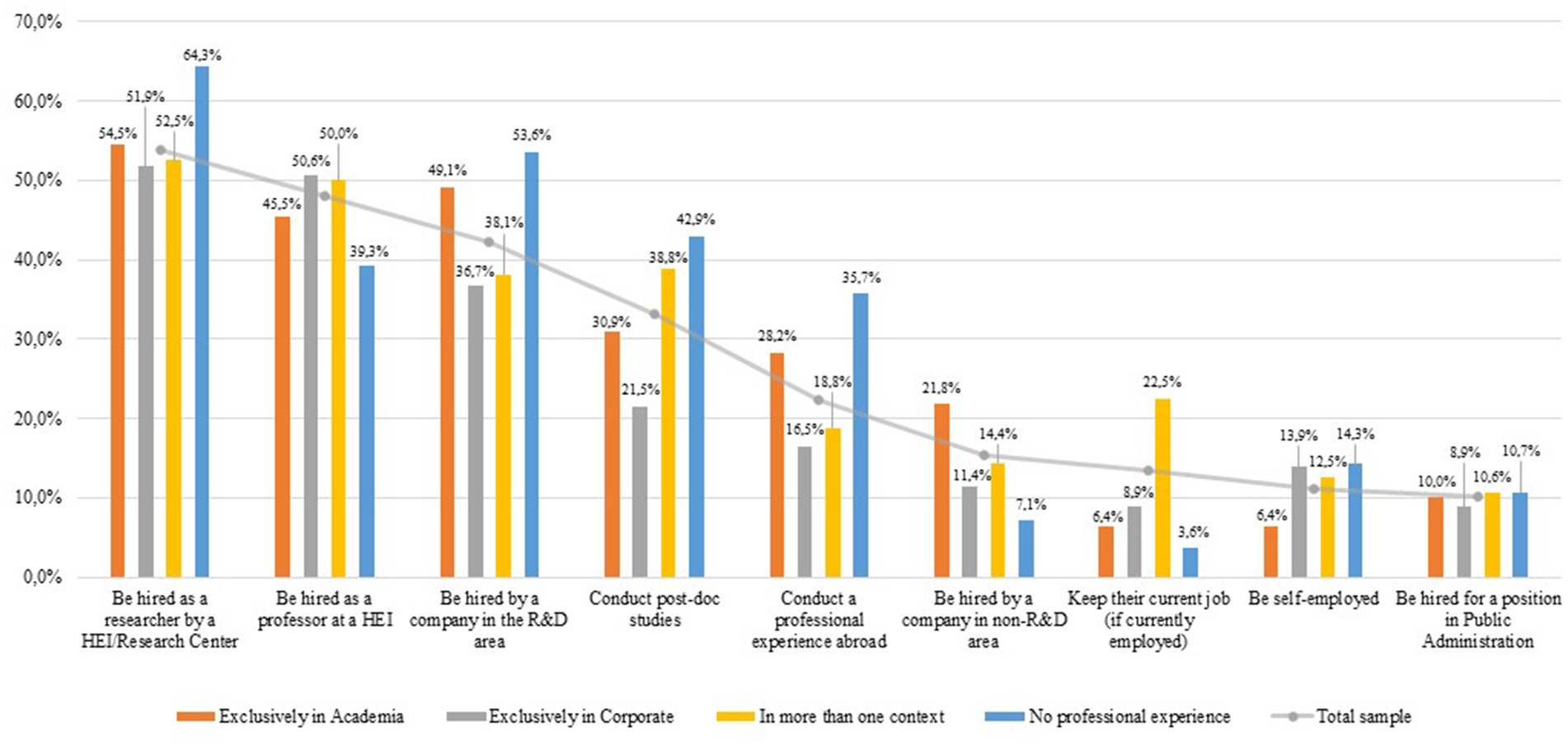

A first analysis of the career expectations selected by students (Figure 1) identifies that the expectation of being “hired as a researcher by an HEI/Research Center” was selected the most by all students independently of their professional experience. It emerged as the career path preferred by 53.8% of the total sample and preferred by the students with no professional experience (64.3%), followed by those with experience in Academia (54.5%), the students with professional experience in different contexts (52.5%) and lastly, the students coming from a corporate background (51.9%).

For the students with Corporate professional experience and the students with experience in more than one context, the expectation to follow a research career in Academia is followed by the expectation of being “hired as a professor at an HEI,” an option that was selected by 50% of the students from both groups (50.6% on corporate experience and 50% by those with more than one professional experience). In turn, the students with no professional experience and those with experience exclusively in Academia present the career expectation of being “hired by a company in the R&D area” as their second most selected career expectation (53.6 and 49.1%, respectively). However, the students with Corporate professional experience and those with experience in more than one context do not match their peers and reveal fewer expectations of being “hired by a company in the R&D area” (36.7 and 38.1%, respectively). Considering the selection of the career expectation of being “hired by a company in the non-R&D area,” this option was among the least selected, with only 15.4% of the total sample.

Figure 1 shows the detail of the frequencies of different career expectations after the conclusion of the PhD, divided by group of professional experience.

3.2. Perceptions of preparedness on career development actions

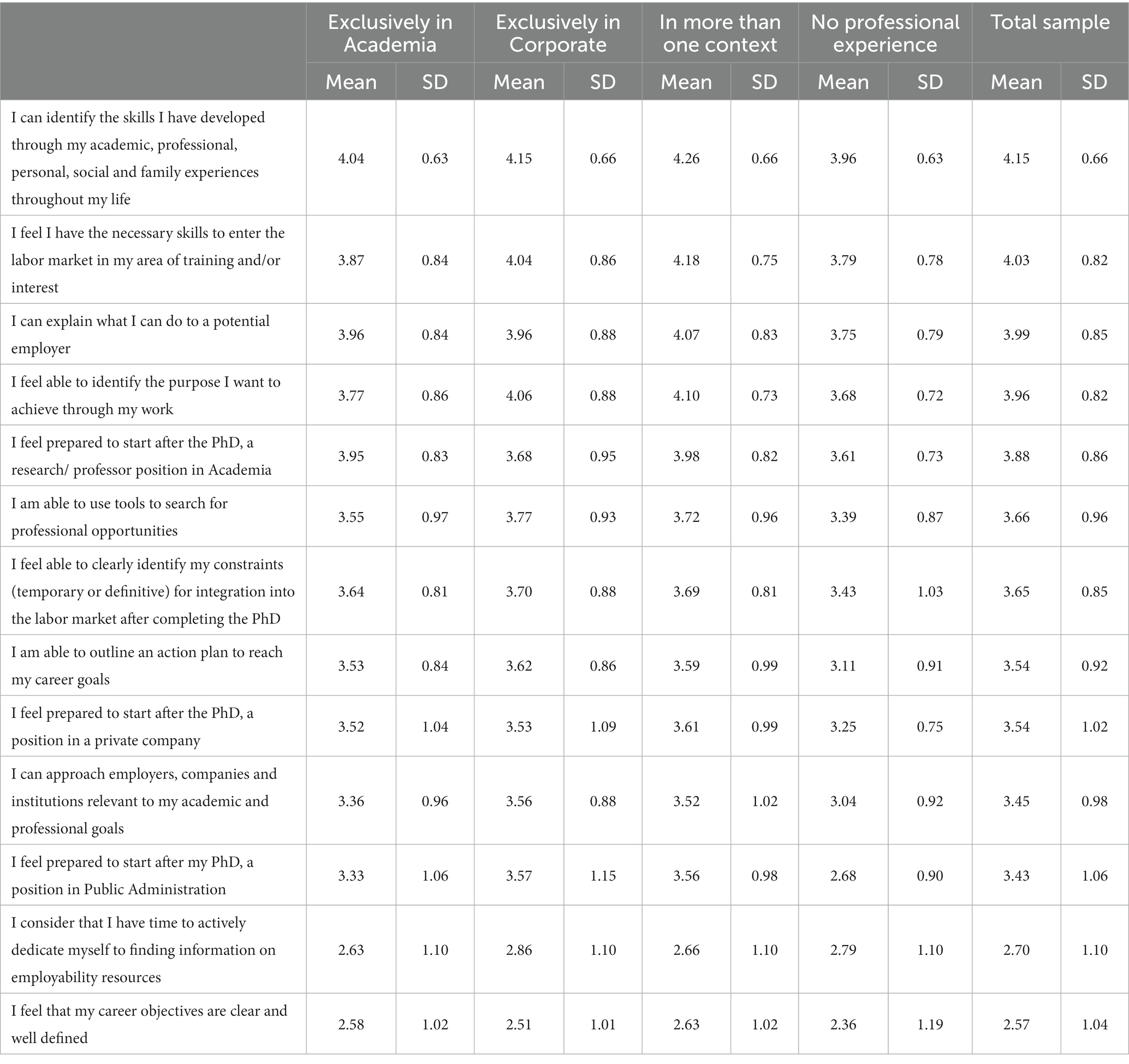

Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations that represent the position of the students from different professional experience backgrounds on the items related to their sense of preparedness and capability regarding different career development actions.

Table 2. Students’ perceptions of preparedness in terms of career development actions by group of professional experience.

The total sample of students (N = 377) feels very capable of identifying the skills which they have developed through different experiences throughout their lives (M = 4.15; SD = 0.66). Students also consider having the necessary skills to enter the labor market in their area of training and/or interest (M = 4.03; SD = 0.82), and being capable of explaining what they can do to a potential employer (M = 3.99; SD = 0.85), although rating with less certainty their capability to approach employers, companies and institutions relevant to their academic and professional goals (M = 3.45; SD = 0.98).

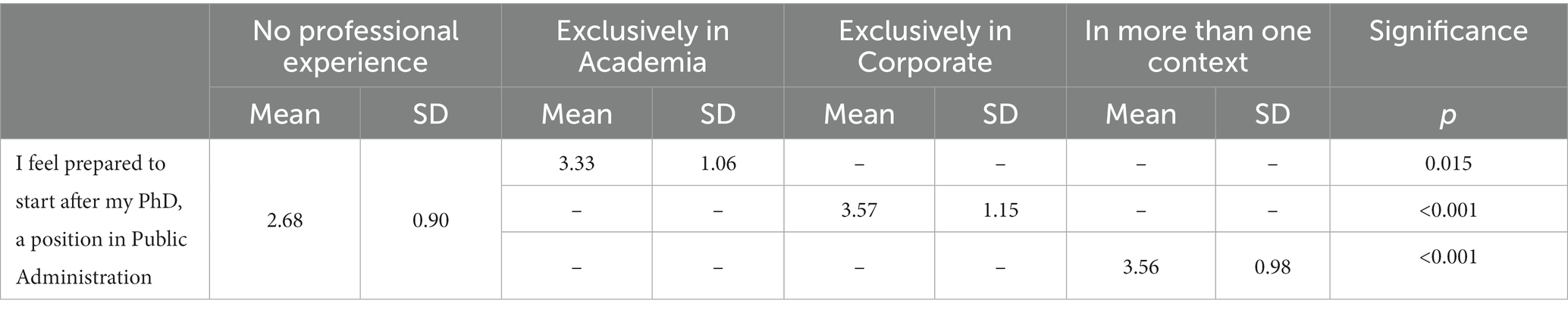

Considering their feeling of preparedness to start positions on different sectors after concluding the PhD, students feel better prepared to start a research/teaching position in Academia (M = 3.88; SD = 0.86), followed by a position in a private company (M = 3.54; SD = 1.02) and then a position on the Public Administration sector (M = 3.43; SD = 1.06). In terms of career development actions, students identify (although not strongly agree) that they are able to use tools to search for professional opportunities (M = 3.66; SD = 0.96), though reflecting not having enough time to actively dedicate themselves to finding information on employability resources (M = 2.70; SD = 1.10). On developing an action plan, students identify that they can outline an action plan to reach their career goals (M = 3.54; SD = 0.92) but consider that their career objectives could be more precise and better defined (M = 2.57; SD = 1.04).

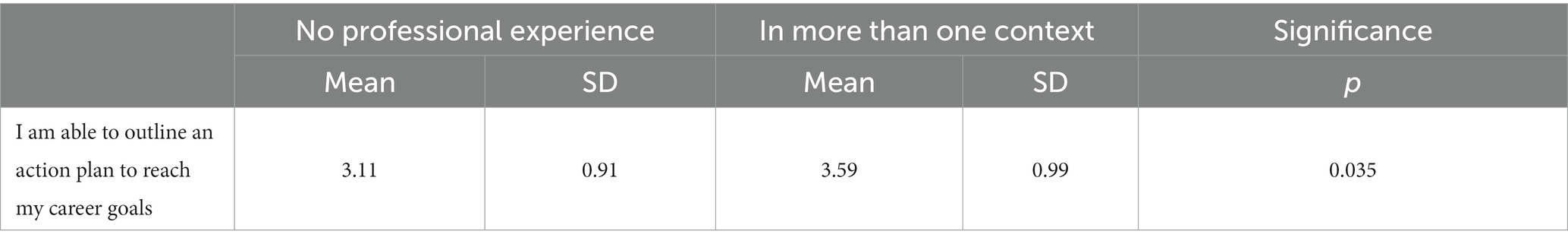

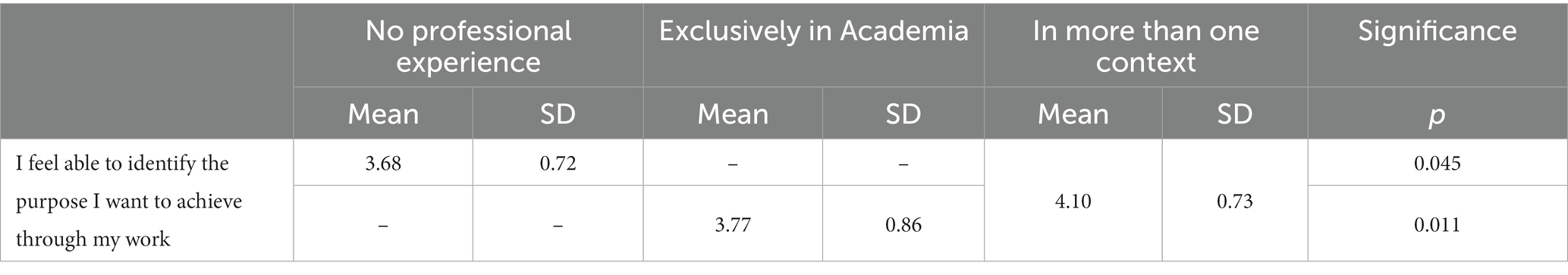

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze if there were differences among the students with different professional experience backgrounds. The test identified significant differences among the groups on six of the items: “I can identify the skills I have developed through my academic, professional, personal, social and family experiences throughout my life” (H(3) = 11.97, p = 0.007); “I feel I have the necessary skills to enter the labor market in my area of training and/or interest” (H(3) = 12.59, p = 0.006); “I feel able to identify the purpose I want to achieve through my work” (H(3) = 15.85, p = 0.001); “I feel prepared to start after the PhD, a research/ professor position in Academia” (H(3) = 10.11, p = 0.018); “I am able to outline an action plan to reach my career goals” (H(3) = 8.29, p = 0.040); “I feel prepared to start after my PhD, a position in Public Administration” (H(3) = 21.11, p = <0.001).

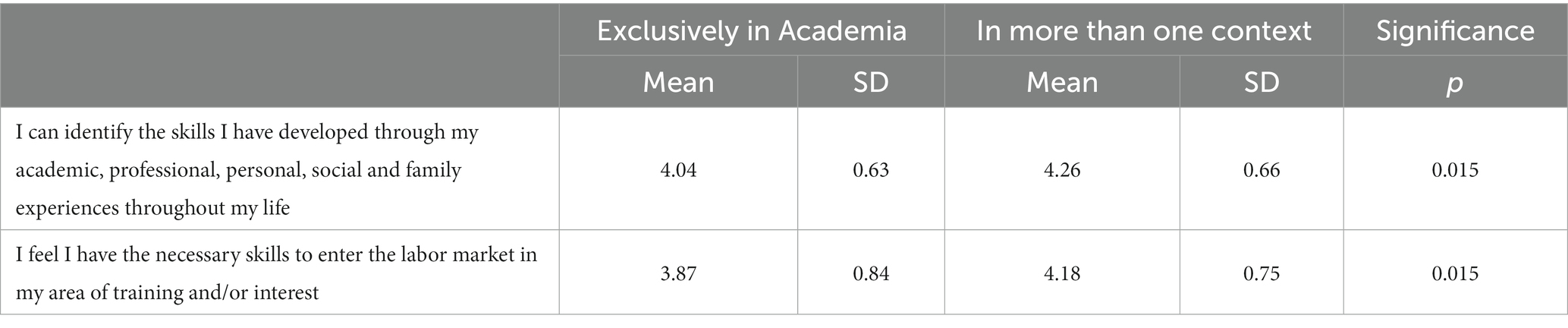

A Post-Hoc test was then used to identify the mean differences among the groups on each of the six items. Pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni test identified significant differences on five items, especially between students with experience exclusively in Academia and those with experience in more than one professional context. Moreover, while the test correction did not show significant differences in all the items regarding the group of students with no professional experience, it can be perceived a tendency for this group to present lower means than the group with more than one experience. The following differences were identified on the items analyzed:

• Between the students with professional experience in Academia and the students with experience in more than one context (Table 3).

• Between the students with no professional experience and the students with experience in more than one context (Table 4).

• Between both the students with no professional experience and professional experience on Academia with the students with experience in more than one context (Table 5).

• Between the students with no professional experience and the students from all professional experience groups (Table 6).

Table 3. Differences between students with professional experience in Academia and students with experience in more than one context.

Table 4. Differences between students with no professional experience and students with experience in more than one context.

Table 5. Differences between both the students with no professional experience and professional experience on Academia with the students with experience in more than one context.

Table 6. Between the students with no professional experience and the students from all professional experience groups.

Regarding the item “I feel prepared to start after the PhD, a research/ professor position in Academia,” although the Bonferroni test correction did not identify significant differences, the significant results without the added correction showed that there are differences between the students with no professional experience (M = 3.61; SD = 0.73) both with the students with professional experience in Academia (M = 3.95; SD = 0.83) (p = 0.028) and the students with experience in more than one context (M = 3.98; SD = 0.82) (p = 0.015). This item also presents significant differences between the students with professional experience in a corporate context (M = 3.68; SD = 0.95) and the students with experience in more than one context (M = 3.98; SD = 0.82) (p = 0.022).

4. Discussion

As PhD holders and students present a value of knowledge and innovation for society (Auriol et al., 2013; Afonja et al., 2021), in this study we had the aim of exploring the value played by PhD students’ previous work experiences (prior to their enrolment in the PhD) in the construction of their career path, considering both career expectations for after the completion of the PhD and preparedness for career development actions. The results shed light on the preference of PhD students for career options related to research, preferably within HEIs, regardless of the diversity of their previous professional experiences. When considering the student’s feeling of preparedness for developing career development actions, it was possible to identify differences between the students’ groups, where those with more diverse professional experiences, i.e., having worked in more than one professional context, stand out by reporting a better preparation to act upon their career development.

Regarding the first research question, although there is a diverse pool of students with different work experiences when joining the PhD, this diversity is not translated into the student-preferred career expectations once the degree is completed. Research-related careers were the career expectations most identified by all professional experience groups. This result is aligned with findings from studies that did not consider the student’s previous professional experience (Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Kim et al., 2018; Lauchlan, 2019; Cornell, 2020). This finding indicates that the PhD holders’ employability challenge, related to Academia being their primary employer (Eurostat, 2017; OECD, 2019; DGEEC, 2021) and the lack of permanent employment positions offered in this context (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; der Boon et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018; Sherman et al., 2021), may be even more relevant than initially thought.

Promoting research careers seems facilitated within the Academia context because it is linked to the Academia’s traditional mission of contributing to knowledge in Society (Barnett and Bengtsen, 2020). It is a professional context that can provide more recognition to the PhD qualification and to the skills the students develop related to research and innovation (Stehlik, 2011). It is less immediate to establish this connection in most company functions. Within Academia more factors can shape research-related career expectations, such as (i) the tendency of some Doctoral Programs to enhance the preparation of PhD students for traditional academic-related careers (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; der Boon et al., 2018; Jones, 2018; Bitušíková and Borseková, 2020); (ii) the proximity PhD students develop with their supervisors, as figures that present one of the most used sources of information for career development (Thiry et al., 2015; Woolston, 2017, 2020), and whose own career experience is academic-centered (Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Sherman et al., 2021), leading supervisors to recognize not having sufficient knowledge to keep students updated on skills and careers outside Academia (Watts et al., 2019).

Based on the principle that previous experiences are valuable to expand the career possibilities considered (Coimbra et al., 1994; Ouvrier-Bonnaz and Vérillon, 2002; Bersin and Sanders, 2019; Lent and Brown, 2021; Savickas, 2021), findings identify that they should be research-related, as these careers were chosen the most by all professional groups. For that reason, to intervene in the employability challenges faced by PhD students, it is essential to go beyond the focus on the individual, and also involve the work context, which is expected to promote research experiences and embed this dimension into the available positions for PhD holders. Intervention for PhD students career development should focus on the possibility of introducing them to positions enriched with the research dimension; for companies and other institutions, it should focus on showing the PhDs’ added value for innovation knowledge (Auriol et al., 2013; Barroca et al., 2015; Afonja et al., 2021) and also the potential of incorporating the R&D dimensions within their jobs.

It becomes fundamental to intervene in these contexts to increase the quality of work experiences as a way of encouraging students to consider different career paths as equally attractive and not just as a “plan B” when faced with the employability challenges of the Academia context (Boman et al., 2021). To achieve this, it is essential to reinforce the bonds between students, education institutions, and companies (Lacomblez and Teiger, 2007; Percy and Kashefpakdel, 2018).

Focusing on the findings from the second research question to what extent PhD students with diverse professional experience backgrounds would feel more prepared to develop career development actions than the students with less diverse career backgrounds - this study allowed us to understand that the more diverse the work experiences are, the more prepared students feel about working in their career development. In fact, the PhD students with experience in more than one context presented a higher sense of preparedness to build their career development proposition, reporting a greater capacity for reflection on the world of work and on themselves. The reflection produced on the world of work is translated into the perception that they have the necessary skills to enter the labor market in their area of training and/or interest and, thus, to outline an action plan for their career goal. The reflection produced about themselves is translated into the perception of a better preparation to identify the purpose they want to achieve with their work and to identify the skills they have developed throughout their lives.

These results are aligned with the literature on career development at different points in the life cycle, when the importance of exploring all gained opportunities to plan and develop career paths is highlighted (Coimbra et al., 1994; Delors et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2022), promoting a sense of preparedness to plan the involvement in new experiences (Savickas et al., 2009), thus, contributing to plan for the future (Zhang et al., 2022). Admitting that the development of each individual corresponds to the history of their development (Clot, 1999), the diversity of experiences also seems to be providing more opportunities to produce a reflection that allows self-knowledge and awareness of the alternatives, enhancing more productive and satisfactory career paths (Greenhaus et al., 2010).

Being able to reflect upon their value proposition can be crucial when employability trends are changing toward less linear and homogeneous careers (Savickas et al., 2009; Volkoff, 2011). Awareness of what can be done or needs to be done to reflect on career alternatives seems essential for students to position themselves toward future career pathways. In the scope of this finding, intervention in PhD students career development can gain from including in the PhD moments that guarantee all students this possibility. Since having previous experience is essential for career development, no one should be left behind from developing these experiences. Otherwise, the inequality remains. The design of the PhD curriculum (Fuhrmann et al., 2011; der Boon et al., 2018; Jones, 2018; Bitušíková and Borseková, 2020) or the influence of the supervisors, who themselves have most certainly made a linear career in Academia (Sauermann and Roach, 2012; Watts et al., 2019; Sherman et al., 2021) could explain the reinforcement of this linearity. It becomes of extreme importance not to perpetuate this situation by contributing to reducing the asymmetry between students with experience and those without, regarding their preparedness to work in their career development.

Considering the limitations of this study and propositions for future studies, we identify that it would be interesting to complement the information on the diversity of previous professional experience with data on the type of work content and the perceived quality associated with that experience, to deepen the understating on PhD students’ construction of their career paths. Secondly, from a methodological perspective, although the formulation of the question on the student’s future career expectations provided the opportunity to identify the options most chosen by all students, it could be interesting for future studies to opt for a hierarchical formulation that would allow students to select their future career expectations in order of preference.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, does PhD students’ previous experience pay off? With this study, we found two answers to this question. On the student’s career development actions, we confirm that having diverse previous work experiences pay off, by making a difference in the feeling of preparedness for career development. Whereas on the student’s future career expectations after the PhD, the study did not allow for a definite answer, as it seems that all professional groups prefer similar research-oriented paths, independently of their previous professional experience. However, this finding highlights an important clue for intervention, as it is clear that PhD students’ willingness to follow diverse career paths implies a work experience that must incorporate the research dimension.

In this scope, these findings support that HEIs must take effective measures to promote PhD students’ career development (Hobin et al., 2014), considering possible intervention actions that can deliberately act on the employability of PhD students and, in that sequence, mitigate the identified employment/career expectations paradox. In this sense, work must be done simultaneously on an individual and contextual intervention, based on two components: (i) allow students to have experiences during the PhD in different and diverse contexts that are related to or include research activities, and promote, simultaneously, the reflection on these experiences so students may feel more prepared to develop their future career; and (ii), involve and promote the awareness of diverse companies for the potential of integrating PhD holders or PhD students, highlighting that if they want to attract and retain this group, they will have to provide positions enriched with the research dimension. Failing to do so may hinder the career construction of PhD students and contribute to enhancing the employability challenges faced by the growing number of PhD holders.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MC: conceptualization. MC and MS: analysis, interpretation of results, and discussion drafting. MC, BA, and AIR: data analysis. MC, BA, and MS: original draft and manuscript writing. All authors discussed the results and contributed to manuscript revision and final version, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The study was developed with the support of the HEI that requested the development of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afonja, S., Salmon, D. G., Quailey, S. I., and Lambert, W. M. (2021). Postdocs’ advice on pursuing a research career in academia: a qualitative analysis of free-text survey responses. PLoS One 16:e0250662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250662

Auriol, L., Misu, M., and Freeman, R. A. (2013). Careers of PhD holders: analysis of labour market and mobility indicators: OECD science, technology and industry working papers. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Barnett, R., and Bengtsen, S. S. (2020). Knowledge and the university: Re-claiming life. New York, NY: Routledge.

Barroca, A., Meireles, G., and Neto, C. (2015). A Empregabilidade dos Doutorados nas Empresas Portuguesas. Matosinhos: Advancis Business Services.

Bersin, J., and Sanders, Z. (2019). Making learning a part of everyday work. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/02/making-learning-a-part-of-everyday-work (Accessed July 23, 2022)

Bitušíková, A., and Borseková, K. (2020). Good practice recommendations for integration of transferable skills training in PhD programmes. DocEnhance.

Boman, J., Baginskaite, J., Sturtz, T., Becker, E., Brecko, B., and Berzelak, N. (2017). 2017 career tracking survey of PhD holders. Strasbourg: European Science Foundation (ESF).

Boman, J., Beeson, H., Barrioluengo, M., and Rusitoru, M. (2021). What comes after a PhD? Findings from the DocEnhance survey of PhD holders on their employment situation, skills match, and the value of the PhD DocEnhance.

Clarke, M. (2018). Rethinking graduate employability: the role of capital, individual attributes and context. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 1923–1937. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152

Coimbra, J. L., Campos, B. P., and Imaginário, L. (1994). Career intervention from a psychological perspective: definition of the main ingredients of an ecological-developmental methodology. Paper presented at the 23rd international congress of applied psychology Madrid.

Cornell, B. (2020). PhD students and their careers. Higher education policy institute policy note 25. London: HEPI.

Delors, J., Al-Mufti, I., Amagi, I., Carneiro, R., Chung, F., Geremek, B., and Nanzhao, Z. (1996). Educação: um tesouro a descobrir. Relatório para a UNESCO da Comissão Internacional sobre Educação para o século XXI. Brasil: Cortez Editora.

der Boon, J., Kahmen, S., Maes, K., and Waaijer, C. (2018). Delivering talent: Careers of researchers inside and outside academia. Leuven: League of European Research Universities (LERU).

DGEEC. (2020). Estatísticas da Direcção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência. Available at: https://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/18/ (Accessed August 3, 2022)

DGEEC. (2021). Inquérito aos Doutorados – CDH20 – Resultados Provisórios. Lisboa: Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência (DGEEC).

Eurostat. (2017). Archive: Careers of PhD holders. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Archive:Careers_of_PhD_holders (Accessed August 3, 2022)

Felaco, C., and Parola, A. (2020). Young in university-work transition: the views of undergraduates in southern Italy. Qual. Rep. 25:8. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4192

Fuhrmann, C. N., Halme, D. G., O’Sullivan, P. S., and Lindstaedt, B. (2011). Improving graduate education to support a branching career pipeline: recommendations based on a survey of doctoral students in the basic biomedical sciences. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 10, 239–249. doi: 10.1187/cbe.11-02-0013

Greenhaus, J. H., Callanan, G. A., and Godshalk, V. M. (2010). Career management (4th Edn). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Hobin, J. A., Clifford, P. S., Dunn, B. M., Rich, S., and Justement, L. B. (2014). Putting PhDs to work: career planning for today’s scientist. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 13, 49–53. doi: 10.1187/cbe-13-04-0085

Jones, M. (2018). Contemporary trends in professional PhDs. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 814–825. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1438095

Kim, E., Benson, S., and Alhaddab, T. A. (2018). A career in academia? Determinants of academic career aspirations among PhD students in one research university in the US. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 19, 273–283. doi: 10.1007/s12564-018-9537-6

Lacomblez, M., and Teiger, C. (2007). “Ergonomia, formações e transformações” in Ergonomia, org. ed. P. Falzon (São Paulo: Blucher), 587–601.

Lent, R., and Brown, S. (2021). “Career development and counseling: an introduction” in Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. eds. R. Lent and S. Brown (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 28–62.

Ng, T. W., and Feldman, D. C. (2007). The school-to-work transition: a role identity perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 71, 114–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.004

Ouvrier-Bonnaz, R., and Verillon, P. (2002). Connaissance de soi et connaissance du travail dans la perspective d’une didatique de l’orientation scolaire: une approche par la coanalyse de l’activité des élèves. Ver. Française de Pédagogie 141, 67–75.

Percy, C., and Kashefpakdel, E. (2018). “Social advantage, access to employers and the role of schools in modern British education” in Career guidance for emancipation: Reclaiming justice for the multitude. eds. T. Hooley, R. Sultana, and R. Thomsen (New York: Routledge), 148–165.

Sauermann, H., and Roach, M. (2012). Science PhD career preferences: levels, changes, and advisor encouragement. PLoS One 7:e36307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036307

Savickas, M. L. (2021) in “Career construction theory and counseling model”, in career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. eds. R. Lent and S. Brown (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 234–276.

Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J., Duarte, M., Guichard, J., et al. (2009). Life designing: a paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 75, 239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004

Sherman, D. K., Ortosky, L., Leong, S., Kello, C., and Hegarty, M. (2021). The changing landscape of doctoral education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: PhD students, faculty advisors, and preferences for varied career options. Front. Psychol. 12:711615. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.711615

Stehlik, T. (2011). Launching a career or reflecting on life? Reasons, issues and outcomes for candidates undertaking PhD studies mid-career or after retirement compared to the traditional early career pathway. Aust. J. Adult Learn, 51, 150–169.

Templeton, R. (2021). Factors likely to sustain a mature-age student to completion of their PhD. Austral. J. Adult Learn. 61:1, 45–62.

Thiry, H., Laursen, S. L., and Loshbaugh, H. G. (2015). How do I get from here to there? an examination of Ph. D. Science students’ career preparation and decision making. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 10:1, 237–256. doi: 10.28945/2280

Volkoff, S. (2011) in “Les éléments d’une nouvelle donne sociodémographique” in Transmission des savoirs et mutualisation des pratiques en situation de travail. eds. C. Gaudart and J. Thébault (Paris: Centre D’Études De L’Emploi), 9–18.

Watts, S. W., Chatterjee, D., Rojewski, J. W., Shoshkes-Reiss, C., Baas, T., Gould, K. L., et al. (2019). Faculty perceptions and knowledge of career development of trainees in biomedical science: what do we (think we) know? PLoS One 14:e0210189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210189

WEF. (2019). Which countries have the most doctoral graduates?. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/10/doctoral-graduates-phd-tertiary-education/ (Accessed July 23, 2022).

Woolston, C. (2017). Graduate survey: A love–hurt relationship. Nature, 550, 549–552. doi: 10.1038/nj7677-549a

Woolston, C. (2020). Wheel Of Fortune: Uncertain Prospects For Postdocs. Nature, 588, 181–184. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03381-3

Keywords: PhD students, professional experience, career development, career perspectives, employability challenges

Citation: Cadilhe M, Almeida B, Rodrigues AI and Santos M (2023) Professional experience before a PhD. Does it pay off? Front. Educ. 8:1129309. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1129309

Edited by:

Anna Parola, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyReviewed by:

Gerardo Petruzziello, University of Bologna, ItalyHelen Higson, Aston University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Cadilhe, Almeida, Rodrigues and Santos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Cadilhe, bWFyaWFjYWRpbGhlQGZwY2UudXAucHQ=

Maria Cadilhe

Maria Cadilhe Beatriz Almeida

Beatriz Almeida Ana I. Rodrigues

Ana I. Rodrigues Marta Santos

Marta Santos