94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ., 03 July 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1121739

Introduction: Most of the recent reviews of literature on open education practices (OEP) seem to be limited in their scope, inhibiting their capacity to arrive at a comprehensive understanding of the concept of OEP. Hence, this systematic literature review was conducted with the purpose of analysing past research on OEP in an effort to identify how OEP is theorised and defined in the existing literature.

Methods: Employing a systematic protocol, the literature search was conducted using the Dimensions database. A total of 30 publications were considered for the qualitative analysis, which engaged a thematic approach.

Results: The findings indicated that the concept of OEP can be explained with a combination of three major components: open education resources, an open teaching and learning process, and open research and scholarly practice. The findings also showed that these components should be grounded in six principles: accessibility, flexibility, shareability, affordability, innovation, and academic freedom.

Discussions: The findings imply that, in order to meaningfully execute open education practices, each of the three components must be given equal importance and that these practices be well grounded in the identified six principles.

The establishment of open universities nearly six decades ago (DeVries, 2019) demonstrates the historical significance of open education. Open universities were established to allow for greater flexibility in admission and exit procedures for learning programmes, as well as to improve access to various learning modes and resources (Li and Wong, 2018). According to literature reviews conducted on the topic of open education in the 1970s, the concept is associated with flexibility in the curriculum, learning activities, learning materials, and teaching delivery (see for example, Horwitz, 1979). As a result, the operation of open universities appears to be based on open education principles.

According to the definitions of open education, the concept was originally unrelated to information and communication technology (ICT) or the internet. Nonetheless, the growing use of open education resources (OER), particularly in the digital domain, highlights the link between open education and ICT. OER broadly refers to any publicly available teaching and learning material, such as course materials, modules, textbooks, videos, tests, software, and so on (Atkins et al., 2007). According to Wiley (2014), an educational resource must have five characteristics in order to be classified as an OER: retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute. Clearly, some of the aforementioned types of OER, as well as the aforementioned characteristics, are related to digital technologies in some way. Similarly, the introduction of massive open online courses (MOOC) and other online learning platforms are examples of OER’s increasing digital orientation.

Despite the historical legacy of open education and, later, OER, recent literature acknowledges the concepts’ diversity and expansion, particularly with the coinage of the term “open education practices” (OEP) in 2007 (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018). Prior to 2007, much of the discussion about open education focused on OER. Recent developments in the concept of open education, on the other hand, argue that it should be expanded to include open approaches to teaching and learning. This transition is commonly referred to as the transition from OER to OEP. According to some early definitions, OEPs are teaching and learning practices that emphasise students’ active and constructive participation in the educational process (Geser, 2007). Furthermore, later definitions make it more explicit by naming specific practices such as open pedagogy, open learning, open scholarship, open sharing of ideas, and use of open technologies (Beetham et al., 2012).

Scholarly efforts to define open education practices have been ongoing for more than a decade. In fact, there have been some recent efforts to elicit the concept of OEP by reviewing the literature. Paskevicius (2017), for example, examined the concept of OEP through a constructive lens and thus was unable to capture a broader perspective on the subject. Similarly, Cronin and MacLaren’s (2018) work was primarily based on some major OEP projects spread across several continents. Because of the study’s design, the conceptualisation of OEP in their review was largely limited to the definitions embraced in the referred projects. Finally, Zhang et al. (2020) contextualised their systematic review of literature by focusing on accessibility for disabled learners rather than capturing the broad concept of the term OEP. As a result, the scope of these reviews is limited, necessitating a more in-depth investigation of the concept of OEP.

As a result, the goal of this systematic literature review was to examine current research on OEP and identify how the concept is theorised and defined in the literature. Furthermore, the review sought to investigate the concepts raised in relation to OEP. We discovered the various concepts associated with OEP through this review and proposed a coherent and comprehensive framework to explain the concept of OEP.

This review is based on OEP-related papers that have been published. Okoli and Schabram’s (2010) method for conducting a systematic literature review was followed in this study. The steps involved in this procedure are described in the sections that follow.

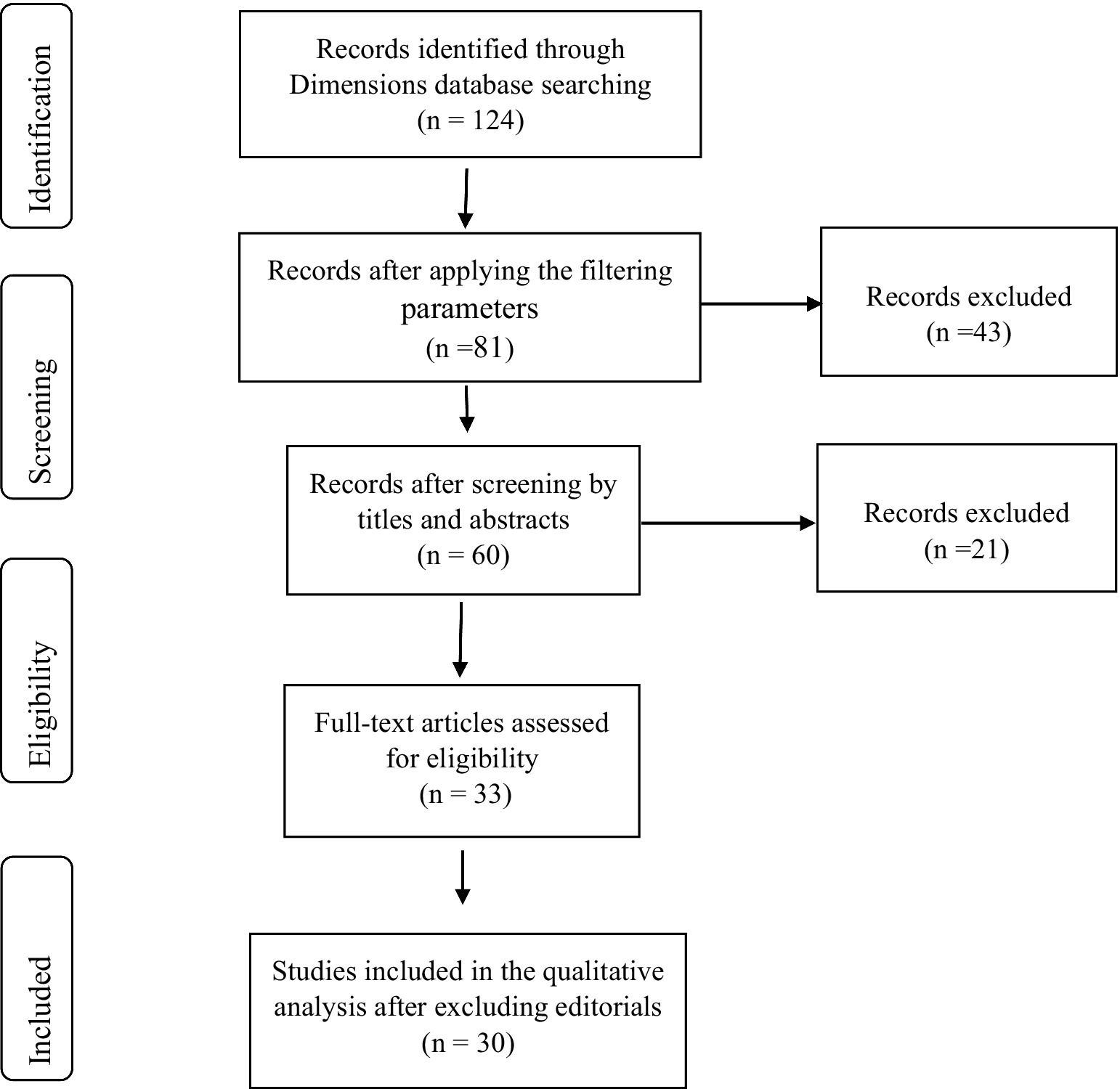

At the outset of this study, the research team devised a protocol that was strictly adhered to throughout its entirety. In this protocol, as suggested by Okoli and Schabram (2010), we determined the location to search for relevant literature, the search terms, the various article screening procedures, and the preliminary inclusion and exclusion criteria. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) methodology, Figure 1 depicts the literature search and screening procedure (Moher et al., 2009). PRISMA provides a concise summary (Siddaway et al., 2019) of the number of included and excluded studies at each stage of the selection procedure.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram showing the flow of the search in the identification and screening of sources for the systemic literature review on open education practices (OEP).

The literature search was conducted on the Dimensions database. The selection of Dimensions database is due to its wider coverage, as “Dimensions is the most comprehensive database developed by Digital Science in collaboration with over 100 leading research organisations around the world” (Patil, 2020, p. 2). The search was conducted on the date of June 30th, 2020. The keyword adopted in the search was “open educational practices”.

We restricted the search to the titles and abstracts of the studies in the database. As a result, the initial search yielded 124 hits, all of which were published in various academic journals. The results were then sifted through the parameters of language, field of research, publication type, and access type. As a result, we chose articles that were written in English. Furthermore, we selected (i) education, (ii) specialist studies in education, (iii) curriculum and pedagogy, and (iv) education systems in the field of research. Furthermore, the publication type was restricted to (i) articles and (ii) proceedings, with the latter finally limited to those published in the open access domain. Eighty one documents were identified as a result of these filters.

Because of its broad scope, the query on the database was narrowed down after the initial search results were retrieved. More informal approaches were used to determine whether the 81 papers were suitable and of sufficient quality to be included in the review synthesis. This included screening the titles and abstracts of the articles, from which we excluded 21 papers because they were inappropriate for the study. The full text of the remaining articles was later cross-checked for quality and appropriateness. Finally, 30 papers were considered for the review synthesis (The full list of these 30 papers can be found in the Appendix A).

When the articles were chosen for the review, relevant information was extracted from the papers and recoded on a pre-designed Excel sheet after extensive reading of each paper. Title, author/s, year, purpose, context, research questions, definition of OER, definition of OEP, theories used, key concepts and their definitions, research design, participants, instruments, key findings, and future research recommendations are among the data extracted from the articles. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved during this process through timely discussions within the research team, and consensus was reached as a result.

Following the extraction of data from the articles, the Excel sheet was divided into three sections: (1) definition of OER, (2) definition of OEP, (3) theories used, and (3) key concepts and their definitions. These retrieved data were qualitatively analysed using the Atals.ti7 software. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used to accomplish this. During this process, key ideas were coded, classified, and combined to generate specific themes that explain what OEP is in a logical way. Later, a framework was developed based on these specific themes to demonstrate how OEP can be explained. The following is a presentation and discussion of the themes identified during the review.

This study investigates how OEP is defined and conceptualised in the academic literature. As shown in Figure 2, OEP is investigated in relation to five broad areas: (1) perspectives and attitudes, (2) curriculum enhancement, (3) experience and practices, (4) research review, and (5) social justice. It was determined that, among these five areas, the largest number of papers (n = 17) were based on OEP experience and practices, while the smallest number (n = 2) related to OEP and curriculum enhancement. As described in the reviewed literature, the studies were conducted using seven distinct research methods: action research (n = 4), case study (n = 7), content analysis (n = 3), mixed method (n = 4), qualitative research method (n = 2), systematic literature review (n = 6), design-based research (DBR) approach (n = 1), and survey (n = 3).

Open education practices perspectives and attitudes show a broad appreciation for their potential to democratise education (Harrison and DeVries, 2019). OEP’s role in fostering agency and autonomy is recognised by instructional designers and educators, albeit with inherent challenges (Clinton-Lisell, 2021). However, there is a persistent gap in OEP implementation between intentional and operational agency (Morgan, 2019). In terms of curriculum enhancement, OEP have demonstrated their ability to diversify and improve educational materials (Bennett and Hyland, 1979; Littlejohn and Hood, 2017). A combination of open resources and pedagogies promotes intercultural learning (Nascimbeni et al., 2018), addresses learner diversity (Altinay et al., 2018), and promotes self-directed learning (Tarling and Gunness, 2021). Transitioning to OEP, on the other hand, requires educators to navigate new paradigms of curriculum development and delivery. The dynamic and context-dependent nature of OEP is reflected in its practical application. Despite geographical and institutional differences, issues of accessibility, reusability, and participation are shared (Hannon et al., 2013). Educators must deal with varying levels of digital literacy and technological access, which requires flexible approaches (Ogange and Car, 2021). The emphasis in research reviews has shifted from Open Educational Resources (OER) to broader OEP, emphasising the importance of considering the socio-cultural dynamics surrounding their use (Deimann and Farrow, 2013; Ramirez-Montoya, 2020). However, due to the multifaceted nature of OEP, assessing its effectiveness and impact remains difficult (Morgan et al., 2021). Finally, the role of the OEP in advancing social justice has been recognised. OEP provide opportunities to address economic, cultural, and political injustices, particularly for marginalised populations such as refugees (Charitonos et al., 2020). Nonetheless, social justice in OEP is more than just cost cutting; it also entails actively mobilizing resources to challenge inequalities and empower users (Seiferle-Valencia, 2020).

The analysis of relevant definitions and concepts revealed that the term “open education practices” can be defined in numerous ways. Even within the domain of open education, the phrase “open practices” continues to evolve. Similarly, conceptualisations of OEP differed significantly by expanding the focus beyond the creation and use of OER to encompass broader definitions of OEP (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018). As depicted in Figure 3, we discovered that the conceptualisation of OEP extends beyond OER to include a combination of several other concepts. OER emphasises the availability and accessibility of content and resources, whereas OEP refers to the practices of establishing the educational environment in which OER are developed and utilised (Ehlers, 2011).

The framework depicted in Figure 3 is a pedagogical model that indicates an organised collection of several key variables that illuminate the conceptualisation of OEP in prior research. As illustrated by the framework, OEP is comprised of three primary components. These are open education resources (OER), open teaching and learning processes (OTLP), and open research and scholarly practices (ORSP). In addition, OER is explained in terms of five subcomponents: (1) the use of OER, (2) the management of OER, (3) the production of OER, (4) the sharing of OER, and (5) open technology. Similarly, OTLP consists of (1) learner agency, (2) open pedagogical practices, (3) open learning avenues, and (4) open assessment. In addition to these major concepts, six specific principles that serve as cohesive agents for the components’ structure were identified. These are (1) accessibility, (2) flexibility, (3) shareability, (4) affordability, (5) innovation, and (6) academic freedom. These themes emerged from a comprehensive synthesis of the codes obtained during the analysis. The initial codes are provided in Appendix B and served as the basis for the development of these themes.

Following is a detailed explanation of each of these components of the framework.

Open education resources (OER) was identified as the review’s first major theme. As shown in Figure 3, the OER theme consists of numerous subcategories. These subcategories represent the fundamental concepts enshrined in the prevalent OER definitions. According to UNESCO (2020), OER consists of “teaching, learning, and research materials in any medium—digital or otherwise—that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open licence that permits free access, use, adaptation, and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions.” In other words, these are “resources that are freely accessible to educators and students without the necessity of paying royalties or licence fees” (Butcher, 2015, p. 5).

The use of OER encompasses the concepts of reuse, revision, re-creation, and repurposing. The more OER are reused and created, according to Ehlers (2011), the closer they are to the essence of OER. Reuse and creation of OER are associated with high levels of participation in social practices, collaboration, and resource and practices sharing. Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL), which called for a shift in emphasis from OER to OEP [Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL), 2011], echoes this sentiment. Moreover, as argued by Wiley and Green (2012), there should be an emphasis on reusing OERs and adapting (in addition to creating) their use to achieve a variety of instructional objectives.

According to Cronin (2017), the use of OER could be associated primarily with collaborative pedagogical practices that encourage interaction through networks, peer-learning, co-creation of knowledge, and learner empowerment. In the recent past, however, the emphasis has shifted from pedagogical aspects to social transformation. According to this view, the use of OER should not be restricted to innovative pedagogy and learner empowerment; rather, it should be expanded to include cost reduction and improved access to education in order to reduce social inequality (Hodgkinson-Williams and Trotter, 2018).

We therefore believe that OER should be embraced as a teaching tool within the context of OEP, and should be characterised by accessibility, affordability, and shareability. It is crucial that teachers and students have access to resources that are freely available and accessible and can be used, adapted, and shared without restrictions like the need to pay royalties or license fees. This viewpoint promotes the use of open OER not only for cutting-edge teaching strategies and learner empowerment, but also for lowering costs and enhancing access to education, thus addressing social inequality. Hence, we propose that OEP should embrace OER as a pedagogical tool that fosters collaboration, interaction, and learner empowerment while also addressing issues of cost and access in education.

The analysis identified open teaching and learning processes as the second most significant theme. Figure 3 illustrates that this theme consists of four categories: learner agency, open pedagogical practices, open learning avenues, and open assessment. All of these categories are consistent with the recent expansion of OEP. While the initial conception of OEP was largely limited to the creation and use of freely available educational resources, a more recent understanding of the concept is centred on the process as opposed to the content (Koseoglu and Bozkurt, 2018).

The expanded concept of OEP recognises that there are a variety of learning channels and platforms, as well as multiple entry points into any given learning programme (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018). This concept is depicted in Figure 3 under the category “open learning avenues.” Regarding platforms, the vast majority are based on information and communication technology (ICT) and the internet. This concept is associated with terms including online learning (DeVries, 2019), e-learning (Weller et al., 2018), distance and ICT-based learning [Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL), 2011], blended learning, m-learning (Chiappe and Adame, 2018), etc. These learning opportunities may take the form of open courseware and content, open software, and open materials for learners as well as educators [Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL), 2011]. As a means of lowering barriers to continuing education, these avenues and arrangements allow for multiple entry points (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018).

As stated elsewhere, the open education movement has witnessed a shift from OER to OEP, which is essentially a diversion of attention from open resources to the open education process (Beetham et al., 2012). This notion is reflected in the category of open pedagogical practices within the topic of open teaching and learning processes (see Figure 3). Open pedagogical practices are reliant on participatory technologies and social interaction via networks, knowledge creation, peer-learning, learner empowerment, and shared learning practices (Ehlers, 2011; Cronin, 2017). In addition, as propagated by Beetham et al. (2012), it entails the sharing and exchange of teaching experiences among educators in order to expand their expertise in teaching and learning. In general, open pedagogical practices are those that place the learner at the centre of the teaching and learning process, with the content and delivery of that content influenced by the differences between learners.

Figure 3 depicts the category labelled “learner agency” under the theme of open teaching and learning processes, which was identified following a review of the literature. This concept is related to, but distinct from, the learner-centeredness concept discussed previously. The philosophy of constructivist learning supports both of these concepts (Geser, 2007; Wiley and Hilton, 2018; Maha et al., 2020). On the other hand, they differ in that, in the learner-centeredness approach, students may still be passive in terms of shaping and creating knowledge, whereas if learners are treated as agents, they would be given more freedom in terms of shaping and co-creating knowledge for themselves (Cronin, 2017). Consequently, the concept of learner agency, in contrast to learner-centered teaching, emphasises greater academic freedom for learners.

Open assessment, as depicted in Figure 3, is the last category under the theme of open teaching and learning processes. According to the literature reviewed, the notion of openness in education is not limited to OER; rather, it should be expanded to include assessment and accreditation (The Cape Town Open Education Declaration, 2007; Paskevicius, 2017). If this is the case, then OEP should be expanded to include open content (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018) and an open or flexible curriculum (Chiappe and Adame, 2018). While this involves re-designing learning outcomes (Paskevicius, 2017), it is also accompanied by a number of inherent difficulties in designing open forms of assessment (Karunanayaka et al., 2015). Consequently, achieving openness in education would necessitate a mindful approach for addressing such obstacles.

Open education practices was enhanced by the idea of open teaching and learning process, which acknowledges that learning can take place through a variety of platforms and channels. The open process emphasises learner participation, social interaction, peer-learning, learner empowerment, and shared learning practices. It involves the exchange of teaching experiences among educators to enhance their expertise. Learner agency, on the other hand, goes beyond learner-centeredness by giving learners more freedom in shaping and co-creating knowledge for themselves. Open assessment, the last category under open teaching and learning processes, extends the notion of openness to include assessment and accreditation. This expansion of OEP includes open content and a flexible curriculum. However, designing open forms of assessment presents challenges that need to be addressed mindfully. Overall, embracing open teaching and learning processes requires considering a wide range of factors, including learner agency, pedagogical practices, learning avenues, and assessment strategies, to foster a more inclusive and participatory education system.

The theme of “open research and scholarly practice” emerges as an important aspect in the existing literature on Open Educational Practices (OEP). However, when compared to other aspects of OEP, this theme appears to be less prominent as a central concept within the broader openness movement. The open scholarship paradigm, proposed as a new approach to education and research, includes open data and research (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018). This scope has since been expanded to include open digital identity, open tools, and open publishing, as well as digital and networked technologies (Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012). Despite these significant contributions, they remain relatively sparse in comparison to the depth of exploration in other OEP themes.

Open peer review is a significant emerging concept within this theme (Paskevicius, 2017). Unlike the traditional blind peer review model, open peer review reveals the identities of authors and reviewers throughout the process. While this change may spark debate, it highlights the breadth of innovation covered by the open research and scholarly practice theme. This theme includes open research, open data, open access publication (Cronin and MacLaren, 2018), and open scholarly knowledge sharing (Harrison and DeVries, 2019). Despite their potential, these concepts require further investigation and discussion.

One such aspect is open data, which is defined as data that is freely available for anyone to use for research purposes. There are a variety of open data sources available, including those published by the government and non-profit organisations. Furthermore, open data repositories like Mendeley Data and Harvard Dataverse allow researchers to submit anonymised datasets from their research. Similarly, recent publication access models require authors to pay a fee for the public to read, distribute, and use their work for non-profit purposes (Berlin Declaration, 2003). Finally, the literature suggests that the concept of openness in education should include practices such as research and publication. Despite their importance, these practices have not been adequately discussed or integrated into the larger discourse on open education. As a result, further investigation and a more active participation in the OEP discourse are advocated.

In addition to the three themes discussed previously, there are six important principles associated with OEP concepts. These six guiding principles are (1) accessibility, (2) flexibility, (3) shareability, (4) affordability, (5) innovation, and (6) academic freedom. As identified in the selected papers, when the articulation of OEP is linked to these principles, it provides a better understanding of the concept, resulting in enhancements to the quality of educational experiences.

The aforementioned characteristics are most frequently associated with OEP and OER in numerous research publications (Ehlers and Conole, 2010; Ehlers, 2011; Paskevicius, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). The systematic literature review conducted by Zhang et al. (2020) on the topic of OEP revealed that “accessibility” is among the most frequently used keywords in all the reviewed papers. According to these researchers, despite its prominent role in promoting OEP, accessibility within OER is still in its infancy. Therefore, Zhang et al. (2020) proposed four accessibility principles: perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust, and recommended that researchers place a greater emphasis on these principles when developing OER.

In the same vein as accessibility, the principles of adaptability are essential because they are crucial to student success and social justice (Harrison and DeVries, 2019). Flexibility in learning is crucial for expanding access to higher education, particularly in an era of rising enrolments worldwide (Andrade and Alden-Rivers, 2019). Due to the importance of accessibility in OEP, the “one best resource” mentality is frequently replaced in recent literature by “flexible resources” that can be easily adapted for multiple settings and contexts (Harrison and DeVries, 2019). Also, the design of more open student learning outcomes that promote quality and innovation in teaching and learning within open learning ecologies is strongly related to the flexibility of open practices (Paskevicius, 2017). Due to these factors, one could conclude that OEP without flexibility would be a poorly received and less likely to succeed concept.

In terms of shareability, research and practices indicate that the adoption of OER necessitates a culture of sharing in addition to other qualities (Ehlers, 2011). Sharing practices is essential for enhancing knowledge, student achievement, and learning, and for developing more creative pedagogies (Harrison and DeVries, 2019). Additionally, it assists individuals in advancing their own work, teaching, and research processes (Paskevicius, 2017). According to Ehlers and Conole (2010), the knowledge created by students and instructors can be disseminated in a variety of ways using Web 2.0 tools. However, in the majority of instances, not only students but also teachers feel uneasy about sharing their resources and making the materials freely accessible (Masterman and Wild, 2011; Paskevicius, 2017). Therefore, policy-driven grassroots initiatives, such as consultation processes or incorporating OER sharing and use into the accreditation process, must be implemented (Masterman and Wild, 2011). Similarly, students can be empowered to share their work more broadly through encouragement, opportunities, and literacies (Paskevicius, 2017).

In addition, as shown in the framework, one of the principles that makes OEP possible is the affordability of resources. Wiley (2014) proposed the 5R model to describe the affordances, practices, and possibilities of working with OER. This model consists of retain, revise, remix, reuse, and redistribute. In addition to these five methods, the use of digital technologies is also regarded as a cost-effective means of promoting open practices, regardless of their opportunities and difficulties (Paskevicius, 2017). Encouraging the practical application of all types of resources requires both an understanding of the affordances of the tools and pedagogical knowledge (Paskevicius, 2017). Similarly, countries must capitalise on the opportunities by developing and implementing educational policies that incorporate and recognise OEP activities and programmes (Bossu and Stagg, 2018).

Figure 3 illustrates that innovation is another principle associated with OEP. According to the literature review, a number of researchers have associated the characteristic of innovation with the concept of OEP (see Ehlers and Conole, 2010; Masterman and Wild, 2011; Bossu and Stagg, 2018; Karunanayaka et al., 2018). Practitioners are required to engage in innovative scholarly practices of openness in their teaching and learning practices, so the relationship between innovation and OEP is significant (Karunanayaka et al., 2018). Innovative strategies for flexible learning (another key principle), such as online courses, blended courses, competency-based education, and open education resources, are essential for expanding access and meeting the diverse needs of learners (Andrade and Alden-Rivers, 2019). Due to the emphasis on innovative practices, there should be an intentional element of innovative practice in the use of OER in which educational scenarios go beyond reproducing “traditional” educational scenarios, as argued by Ehlers and Conole (2010).

According to the reviewed literature, academic freedom is the final principle inherent to the OEP concept. According to Ehlers (2011), academic freedom is essential for the practice of open education because OEP is socially embedded within the dimensions of openness in resource usage and creation and pedagogical practices. However, in most instances, lack of academic freedom and ownership are impediments to the adoption of OEP (Harrison and DeVries, 2019). Therefore, Ehlers’s (2011) matrix is a suitable instrument for measuring the diffusion of OEP in a given learning context. Ehlers (2011) conceptualised pedagogical levels of “freedom” or “openness” by proposing a matrix with three different levels (low, medium, and high) for the dimensions of OER usage and learning architecture, based on a critical analysis of prior research. As depicted by Ehlers (2011), these dimensions can assist individuals and organisations in self-assessing and positioning their respective contexts, resulting in enhanced quality and fostering innovation in education.

In order to comprehend how the concept is theorised and defined in the existing literature, we investigated the definition and concepts associated with OEP in this study. We found that the concept of OEP can be explained by three major components. These include open education resources, open teaching and learning processes, as well as open research and scholarly practices. In addition, we determined that these components and their associated ideas are founded on six principles: accessibility, flexibility, affordability, innovation, and academic freedom. Collectively, we refer to these principles as elements of social justice. On the basis of the findings, we conclude that OEP, as depicted in the current literature, is a multifaceted concept comprised of open resources and scholarly practices along with an open process of teaching and learning; the concept as a whole is bound by six principles of social justice.

The findings of this study suggest that, in order to effectively implement open education practices, each of the three major components of OEP must be adequately considered. In addition, the findings indicate that when OEP is implemented, it must be founded on the six principles of social justice. Regarding open teaching and learning practices, it is also necessary to promote learner agency and academic freedom. This implies that learners should be more involved in the creation of knowledge, as opposed to merely employing student-centered instructional strategies. In this regard, learners should have more freedom to choose what to learn, how, when, and where to learn it, as well as how to evaluate their learning.

However, we recognise the limitations of the present review. Our use of a single database, while we believe the Dimensions database is adequate for the purposes of this study, may have limited the scope of our findings. However, using the specific search term ‘open educational practices’ (OEP) enabled us to conduct a focused exploration of the relevant aspects of our investigation. The addition of more data sources and a broader term like ‘open education’ could have provided a more comprehensive analysis, but it could also have introduced unrelated concepts. We recognise that restricting our data collection to open-access publications may have limited the breadth of information presented in the paper. However, this approach was philosophically aligned with open education principles, ensuring that the literature reviewed shared the same values. This decision was made in order to foster a more meaningful and relevant dialog within the open education community. While these choices were deliberate and appropriate for the study’s objectives, it is important to recognise that they have limitations. To improve the comprehensiveness and generalisability of findings, future research can investigate the use of multiple databases, different search terms, and a broader range of publication types. Researchers can further their understanding of open educational practices in various contexts by doing so.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1121739/full#supplementary-material

Altinay, Z., Altinay, F., Ossianilsson, E., and Aydin, C. H. (2018). Open education practices for learners with disabilities. Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. (BRAIN) 9, 171–176.

Andrade, M. S., and Alden-Rivers, B. (2019). Developing a framework for sustainable growth of flexible learning opportunities. Higher Educ. Pedagog. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/23752696.2018.1564879

Atkins, D. E., Brown, J. S., and Hammond, A. L. (2007). A review of the open educational resources (OER) movement: Achievements, challenges, and new opportunities. The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Available at: https://hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/ReviewoftheOERMovement.pdfNoTitle

Beetham, H., Falconer, I., McGill, L., and Littlejohn, A. (2012). Open practices: A briefing paper. JISC. Available at: https://oersynth.pbworks.com/w/page/51668352/OpenPracticesBriefing

Bennett, N., and Hyland, T. (1979). Open plan—open education? Br. Educ. Res. J. 5, 159–166. doi: 10.1080/0141192790050202

Berlin Declaration. Berlin declaration on open access to knowledge in the sciences and humanities. (2003). Available at: https://openaccess.mpg.de/Berlin-Declaration

Bossu, C., and Stagg, A. (2018). The potential role of open educational practice policy in transforming Australian higher education. Open Praxis 10, 145–157. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.835

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Charitonos, K., Albuerne Rodriguez, C., Witthaus, G., and Bossu, C. (2020). Advancing social justice for asylum seekers and refugees in the UK: an open education approach to strengthening capacity through refugee action's frontline immigration advice project. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 1–11. doi: 10.5334/jime.563

Chiappe, A., and Adame, S. I. (2018). Open educational practices: a learning way beyond free access knowledge. Ensaio Avaliação e Políticas Públicas Em Educação 26, 213–230. doi: 10.1590/S0104-40362018002601320

Clinton-Lisell, V. (2021). Open pedagogy: a systematic review of empirical findings. J. Learn. Dev. 8, 255–268. doi: 10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.511

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dis. Learn. 18, 15–34. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Cronin, C., and MacLaren, I. (2018). Conceptualising OEP: a review of theoretical and empirical literature in open educational practices. Open Praxis 10, 127–143. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.825

Deimann, M., and Farrow, R. (2013). Rethinking OER and their use: open education as Bildung. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dis. Learn. 14, 344–360. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i3.1370

DeVries, I. (2019). Open universities and open educational practices: a content analysis of open university websites. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dis. Learn. 20, 167–178. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.4215

Ehlers, U. D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of open, flexible and distance learning. 15, 1–10.

Ehlers, U.-D., and Conole, G. (2010). Open educational practices: unleashing the power of OER. UNESCO Worshop on OER, August, 1–9.

Geser, G. (Ed.) (2007). Open educational practices and resources: The OLCOS roadmap 2012. Austria: Salzburg Research Edumedia Research Group. Available at: http://www.olcos.org/cms/upload/docs/olcos_roadmap.pdf

Hannon, J., Bisset, D., Blackall, L., Huggard, S., Jelley, R., Jones, M., et al. (2013) Accessible, reusable and participatory: Initiating open education practices. In ASCILITE-Australian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education Annual Conference. (pp. 362-372), Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education.

Harrison, M., and DeVries, I. (2019). Open educational practices advocacy: the instructional designer experience. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 45, 1–17. doi: 10.21432/cjlt27881

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. A., and Trotter, H. (2018). A social justice framework for understanding open educational resources and practices in the global south. J. Learn. Dev. 5, 204–224. doi: 10.56059/jl4d.v5i3.312

Horwitz, R. A. (1979). Psychological effects of the open classroom. Rev. Educ. Res. 49, 71–85. doi: 10.3102/00346543049001071

Karunanayaka, S. P., Naidu, S., Rajendra, J. C. N., and Ariadurai, S. A. (2018). Designing continuing professional development MOOCs to promote the adoption of OER and OEP. Open Praxis 10, 179–190. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.826

Karunanayaka, S. P., Naidu, S., Rajendra, J. C. N., and Ratnayake, H. U. W. (2015). From OER to OEP: shifting practitioner perspectives and practices with innovative learning experience design. Open Praxis 7, 339–350. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.7.4.252

Koseoglu, S., and Bozkurt, A. (2018). An exploratory literature review on open educational practices. Distance Educ. 39, 441–461. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2018.1520042

Li, K. C., and Wong, B. Y. Y. (2018). “Revisiting the definitions and implementation of flexible learning”, in Innovations in open and flexible education. eds. K. C. Li, K. S. Yuen, and B. T. M. Wong (Singapore: Springer), 3–13.

Littlejohn, A., and Hood, N. (2017). How educators build knowledge and expand their practice: the case of open education resources. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 48, 499–510. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12438

Maha, B., Catherine, C., and Jhangiani, R. S. (2020). Framing open educational practices from a social justice perspective. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 1–12. doi: 10.5334/jime.565

Masterman, L., and Wild, J. (2011). JISC Open Educational Resources programme: Phase 2 OER impact study (Research Report). United Kingdom: JISC.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Morgan, T. (2019). Instructional designers and open education practices: negotiating the gap between intentional and operational agency. Open Praxis 11, 369–380. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.11.4.1011

Morgan, T., Childs, E., Hendricks, C., Harrison, M., DeVries, I., and Jhangiani, R. (2021). How are we doing with open education practice initiatives? Applying an institutional self-assessment tool in five higher education institutions. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dis. Learn. 22, 125–140. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v22i4.5745

Nascimbeni, F., Burgos, D., Aceto, S., Wimpenny, K., Maya, I., Stefanelli, C., et al. (2018) Exploring intercultural learning through a blended course about open education practices across the Mediterranean. In 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 285–288). IEEE.

Ogange, B., and Carr, A. (2021). “Open educational resources, technology-enabled teacher learning and social justice” in Embedding Social Justice in Teacher Education and Development in Africa (Routledge), 45–62.

Okoli, C., and Schabram, K. (2010). A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research. Sprouts: working papers on. Inf. Syst. 10, 1–49. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1954824

Open Educational Quality Initiative (OPAL) (2011). Beyond OER: Shifting focus to open educational practices. Available at: https://www.oerknowledgecloud.org/archive/OPAL2011.pdf

Paskevicius, M. (2017). Conceptualizing open educational practices through the lens of constructive alignment. Open Praxis 9, 125–140. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.9.2.519

Patil, S. B. (2020). A scientometric analysis of global COVID-19 research based on dimensions database. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3631795

Ramirez-Montoya, M. S. (2020). Challenges for open education with educational innovation: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 12:7053. doi: 10.3390/su12177053

Seiferle-Valencia, M. (2020). It's not (just) about the cost: academic libraries and intentionally engaged OER for social justice. Libr. Trends 69, 469–487. doi: 10.1353/lib.2020.0042

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., and Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 747–770. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Tarling, I., and Gunness, S. (2021). Educators’ Beliefs, Perceptions and Practices Around Self-Directed Learning, Assessment and Open Education Practices. In: Radical Solutions for Education in Africa: Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. eds. D. Burgos and J. Olivier (Singapore: Springer), 187–209.

The Cape Town Open Education Declaration (2007). Available at: www.capetowndeclaration.org/read-the-declaration

UNESCO (2020). Open educational resources. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/themes/building-knowledge-societies/oer

Veletsianos, G., and Kimmons, R. (2012). Assumptions and challenges of open scholarship. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 13, 166–189. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v13i4.1313

Weller, M., Jordan, K., DeVries, I., and Rolfe, V. (2018). Mapping the open education landscape: citation network analysis of historical open and distance education research. Open Praxis 10, 109–126. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.10.2.822

Wiley, D. (2014). Defiing the “open” in open content and open educational resources. Available at: http://opencontent.org/defiition

Wiley, D., and Green, C. (2012). “Why openness in education?” in Game Changers: Education and Information Technologies. ed. D. Oblinger (Educause), 81–89.

Wiley, D., and Hilton, J. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dis. Learn. 19, 133–147. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

Keywords: conceptualisation, literature review, meta-synthesis, open education practices, open education resources

Citation: Shareefa M, Moosa V, Hammad A, Zuhudha A and Wider W (2023) Open education practices: a meta-synthesis of literature. Front. Educ. 8:1121739. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1121739

Received: 13 December 2022; Accepted: 19 June 2023;

Published: 03 July 2023.

Edited by:

Dominique Persano Adorno, University of Palermo, ItalyReviewed by:

Elena Tikhonova, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, RussiaCopyright © 2023 Shareefa, Moosa, Hammad, Zuhudha and Wider. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Visal Moosa, dmlzYWwubW9vc2FAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.