- George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, United States

In the past 2.5 years, STEM faculty around the world have faced unprecedent challenges, complete upheaval of routine, and staggering loss. Managing these new realities has required significant emotional labor. This paper offers one perspective on the emotional reality of teaching collegiate chemistry at a large public research university in the United States. Considering and describing emotions such as frustration, grief, anger and hope, I share a hidden reality of being faculty during a pandemic. I also discuss how we might learn from the path traveled and more deftly navigate the road ahead.

Introduction

Teaching is an emotional practice. Emotional labor describes the emotional dimension of service jobs and the implied requirements for people in those jobs (Hochschild, 1983; Dunkel, 1988). In the context of education, multiple authors have studied and recognized a significant emotional component associated with K-12 teaching (Hargreaves, 2001; Hebson et al., 2007; Brown, 2011; Tsang, 2011; Horner et al., 2020). More recent publications have expanded application of this term to college teachers (Auger and Formentin, 2021; Waldbuesser et al., 2021; Berheide et al., 2022). Notably, the works of Berheide et al. (2022) and Auger and Formentin (2021) exposed the disparate share of emotional labor demanded of faculty who identify as women and/or BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color). Although the concept of emotional labor in teaching is not new, it is not a common topic discussed among STEM faculty. But it should be.

In March 2020, with COVID cases rising in the United States, my university pivoted to fully online classes. Suddenly, I was challenged to embrace a new teaching paradigm …or not. At the time, I had been teaching chemistry at the collegiate level for 25 years. My teaching story began as an undergraduate chemistry major teaching one General Chemistry lab each quarter, through graduate Teaching Assistantships for Inorganic and General Chemistry, and finally as a faculty member, both tenured and without tenure. My teaching had always been in person, in labs and lecture halls. While I knew of the existence of online courses, I had never been asked to teach online or virtually. The pandemic changed that.

From March 2020 through Spring 2021, I taught 4 classes and 140 students, all 100% virtually; with this experience, I can confidently affirm that teaching online is exhausting (Sander and Bauman, 2020). Relying on technology while under unprecedented strain to do my job can be (and still is) problematic (Mcmurtrie, 2016; Mansfield and Conlon, 2020). Online assessment is riddled with uncertainty and presents serious ethical and moral dilemmas (Lieberman, 2018; Protopsaltis and Baum, 2019). Teaching online and working from home even challenge faculty who enjoy solitude and identify as introverts (Neuhaus, 2020).

And then, a miracle; vaccines against COVID-19 arrived in 2021. I had never dreamed that a vaccine could be developed so quickly, but as my year of teaching online came to an end in May 2021, I was hopeful. Maybe we would be “back to normal” in the fall? Alas, the year that followed was even more difficult than the year prior, for different and more emotionally challenging reasons. As Chair of the Faculty in the College of Science, I talked with many faculty about these pandemic realities. I’ve seen my colleagues become increasingly exhausted and completely overwhelmed; more than a few have considered or elected to leave academia.

Rather than yet another paper about the mechanical logistics of teaching chemistry in the time of a pandemic, I’m writing about something often overlooked and even more rarely discussed; the emotional experience and costs associated with this job. While I’ve probably always subconsciously known this about my work as a professor, the pivot online during a global pandemic and the years since have literally changed the way I look at my work. As scholars in a physical and mathematical science, chemistry faculty are often expected to readily purge all emotion from our work and be as unemotional as a machine. But the work of faculty is full of emotions and in these years since the pandemic, this has been even more pronounced. For our own and our students’ sake, we must take an accounting of these emotional costs, so we are better prepared to pay the price in the future.

Frustration

“We’re going fully online? Next week? You’ve got to be joking.” – the author, March 17, 2020.

Like many faculty, I was happily cruising along through a spring semester when the abrupt pivot online blind-sided me. Being frustrated with this change was a natural response, but I did not want to let anger and negativity spill over into my classes. In my general chemistry class of 48 students, I focused on what (small) things I could control. Talk about the science, be clear with my examples. With careful thought, my own classes recrystallized into new shape within a couple of weeks. I shifted to a weekly schedule and started recording lectures to be viewed asynchronously. I scheduled weekly problem-solving sessions. I sent extra reminder “Announcements.” Yet, I found myself frustrated with logistics, especially when trying to be consistent across sections of the same course. Should we be using WebEx (Webex, 2022) or Blackboard Collaborate (Blackboard Inc., 2022)? What about Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, 2023)? How should we run office hours? What about exams? Should we use Respondus (Respondus, 2022) monitoring? Why or why not? What if students cheat? I invited colleagues to join meetings about teaching chemistry; open conversations to share what we were trying, how we were adapting. These meetings were generally productive, and I am grateful for those who engaged in the dialog. However, I was repeatedly frustrated by a pattern of inflexibility. In claiming an effort to preserve academic rigor, it seemed too easy to be rigid and assess our classes “the same way we have always done it.” By the end of the semester, I was frustrated and exhausted from trying to explain why this is not the best solution and that online teaching and assessment needs to be different.

I knew these conversations should continue in the future as does our continued commitment to improving our classes. I also knew these conversations would require more scheduled interactions, since informal “how is class going?” hallway chats would be unlikely until our campuses reopened. So, in the years after the pivot, I’ve convened a Chemistry Teaching Circle made up of like-minded colleagues. Our monthly meetings have been truly sustaining for me. We first met virtually through the years online, but are now meeting for conversations and often lunch in person. This circle is a place to compare ideas, ask for advice, and just vent about how hard this work is. These colleagues have become good friends and I am profoundly grateful for them.

Grief

Change and loss beget grief. The grief associated with COVID-19 has felt like a never-ending hurricane season. Just when I think I dried out from one storm, another one hits and washes over me like storm surge. Within weeks of the pivot online in March 2020, my plans for conferences in Philadelphia and Winnipeg were destroyed. Summer trips to Iceland and another chemistry conference in Oregon were canceled. I gained some relief from simply allowing myself to feel sad about these changes, but they still took me by surprise. I also found myself feeling profoundly sad after meeting my students for a WebEx class. The problem-solving session or discussion would be positive and productive, then I would “end the meeting” and feel utterly deflated. The change of only seeing my students in little boxes on my laptop screen was overwhelming. I had not realized how much I valued being in the same physical space with my class.

And my students were struggling. After the mid-March eruption of COVID-19 in the US, I responded to a call from Believe in Students (Believe in Students, 2020a) who were distributing emergency aid for students. The FAST (Faculty and Students Together) fund supports students by giving faculty funds to distribute to those with urgent need (Believe in Students, 2020b) and I was fortunate to be selected for a $5,000 grant (Believe in Students, 2020b). The following week, I opened a short application and shared it with a few classes. I received 45 applications in 36 h, nearly all asking for the maximum support level of $500. Rent, groceries, bills, these young adults were struggling with the basics of human existence. Later in the semester, I learned about one student who was sick with COVID-19 and three others who were caring for sick family members. How could I ask them to struggle with buffers and titrations when they are already struggling?

In the years after the pivot online, the weather patterns changed but there was still grief. One year I taught completely online and never meet my students in person. A group of scholarship students (who I’d mentored for 4 years) graduated without the a usual commencement ceremony. Another year, I rarely (if ever) saw my students’ faces because of masks. Campus was full of empty hallways and closed office doors. I’ve lost count of the number of emails from students who were sick with COVID and could not some to class. I was grateful to be able to host classes in a hybrid format, with simultaneous Zoom room, but those online students did not get the same experience as being in class. Everywhere I looked there were reminders that everything was different, that we were not “back to normal.”

In Spring 2022, shifts in university policy brought their own grief. The semester began with vaccine and mask mandates; faculty began teaching in person with the expectation that these mandates would continue. But one Tuesday morning mid-semester, mask and vaccine requirements were abruptly removed. And faculty received the email at the same time as the students. One colleague told me they were in class lecturing when a student yelled, “no more masks!,” because they had read the email from the university President. To say this shift was inconsiderate is an understatement; it was a complete disregard for faculty class ecosystem and faculty welfare. Fear, anxiety, worry…ultimately, none of those feelings mattered. The decision was made, and we were required to adapt.

Insecurity

My decades of teaching experience did not insulate me from insecurity when teaching online. I was noticeably insecure recording videos for my students. WebEx class sessions felt awkward. And listening to my narrated PowerPoint lectures? More than a little uncomfortable. I did not expect my confidence to be so challenged that first semester, but I am grateful it got better over time. One of the ways I gained confidence was asking for feedback from my class. They understood the videos and appreciated how our class Blackboard page was organized. They liked the pictures I shared of my garden and Lego collection. In our meetings, I acknowledged how different and uncomfortable we all may be feeling. These small steps showed I care about my students and their learning and, consequently, helped me feel more confident about teaching them online.

In summer 2020, I conquered my insecurity about teaching online by recording lectures for my classes and organizing the class material. But the insecurity returned when I logged on to my first virtual classes. Fortunately, at least some students were willing to turn on their cameras. I saw colleagues’ familiar faces and heard their voices in regular meetings. The 2020–2021 academic year felt like my first-year teaching all over again; everything was new and different. But like that first year, I did my best and hoped it would be enough.

Returning to campus in Fall 2021, with masks and vaccines, I faced new insecurities. Would I be able to learn the students’ names? Would I have to use the microphone? Would students be comfortable enough to learn? How would I manage office hours and review sessions? What do I do when students get sick? When I get sick? So many questions and fears again, many different from what I had felt just the year before. It was especially difficult to hear people talk about “returning to normal” when nothing felt like it had before March 2020! Others would say this is the “new normal,” but that was also not helpful when it was never clear what they actually meant by “normal.”

Love

I love teaching. I love my students. I love seeing them learn, but that was very difficult during the pandemic. While teaching virtually, I never required their webcams to be turned on, out of respect for my students’ privacy and sometimes limited internet connectivity. I invited them to be on video, yes, and was so grateful to see their faces when they were willing to share their space. But once we moved online, I could not see the “lightbulbs over their heads” when they understood concepts. I missed seeing their expressions and knowing when I had lost their attention. I missed their raised hands and worked problems on the whiteboard. It’s the process of learning that keeps me coming back to the classroom over and over again. And, when we moved online, this was the part I could barely see! Over the last weeks of the semester, I assigned more short answer type problems, where students would upload written work for me to review. Those problems more clearly showed their thought process and helped me feel more connected to their learning.

My heart is still heavy thinking about how difficult the pandemic was for my students. I did what I could to help; distributing the initial FAST funds and later donations quickly. And in my classes, I was consciously flexible and enabled my students to make choices. They were able to choose which extra credit assignments to complete, which class session to attend (e.g., morning or afternoon), and even the style of exam questions they wanted. To set a positive tone for our virtual sessions, I used the Icebreaker Deck from BestSelf to start classes (BestSelf Co., 2020). Using the cards, I asked students easy questions like “would you rather be hot or cold?” or “what show have you most recently binged.” Their answers, sometimes coming in the chat window instead of with their voices, were funny and light. It felt so good to laugh together. I also consciously spoke words of encouragement; I told my classes I understood these were challenging times and that I wanted to support them. In a reflection question from the end of the semester, students acknowledged these measures helped them feel better about the class:

“I appreciate your willingness to be here for us students and be so flexible in the way we do things. Not all professors are like that in their true desire to help.” (Student A)

“This semester was a challenge all around given the circumstances we were in, but I always looked forward to Chemistry during the week because of the energy you put into teaching and the help you offered us.” (Student B)

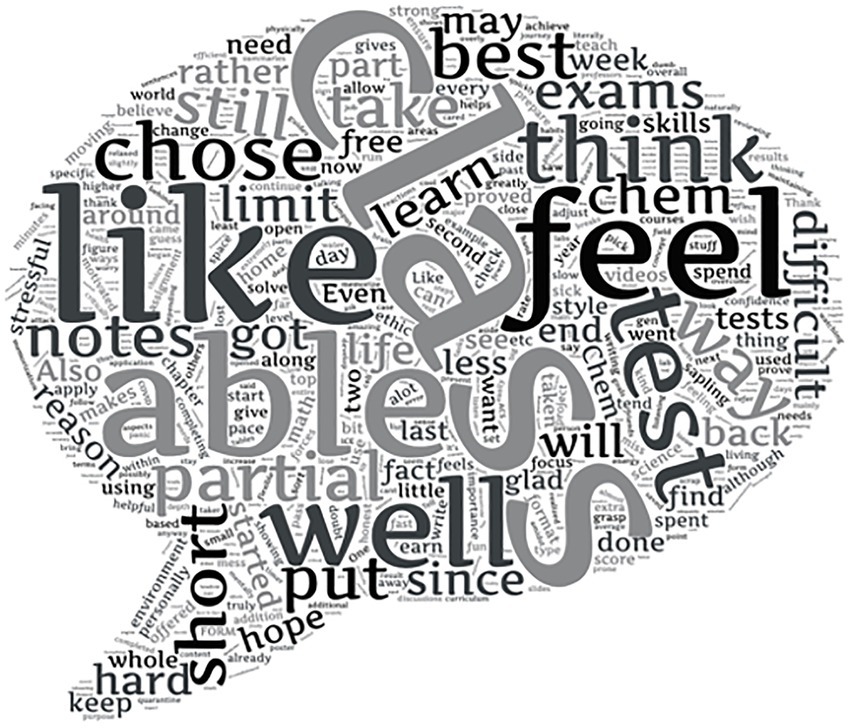

Using all the words students wrote when reflecting on that memorable semester, I generated a word cloud (Zygomatic, 2020) shown in Figure 1. The students’ voices are clear; without a doubt, emotion is a part of their experience.

Confidence

The March 2020 pivot online was akin to being thrown into the deep end of the swimming pool and told to “SWIM!.” To be honest, most faculty learned to dog-paddle their way to the end. After a year of classes online, did we actually learn to swim? Some did, but some barely survived. And even after a year, many did not feel confident about teaching online, in part because of the emotional labor required. I learned a lot during the crisis pivot of March 2020, but there were even more challenges in the years ahead. How could I teach a whole year of online classes? How do I respond to my students coming to class with different prior knowledge because of the pandemic? What needed to change? I wrestled a lot with these questions and we frequently discussed them in the teaching circle. Among some colleagues, I saw a collective leaning toward “what we have always done” rather than recognition that we need to make major changes.

Dr. Erin Whitteck wrote, “Faculty will need to be prepared both in terms of professional development, but also mentally to teach under these conditions. Many social norms of the classroom will be different, that will take up a lot of bandwidth for both students and faculty” (Whitteck, 2020). Dr. Joshua Eyler responded, “This is such an important point. The psychological impact of walking into a room full of certainly uneasy and possibly traumatized students wearing masks and looking to us for safety and guidance will be immense” (Eyler, 2020). I completely agree. And this need is profound in chemistry, where faculty are generally trained to ignore their feelings and act robotic, rather than confront this messy emotional reality.

When classes began in Fall 2022, my confidence had increased. Fall 2022 was my 5th semester teaching in a flipped class format and I was hooked. This method of engagement is different and so much more interactive. I found myself being more explicit about learning outcomes and asking students for their input on the course structure mid-semester. In being more flexible and constantly learning, I evolved as an educator and the experience increased my confidence.

Hope

We have survived life inside a dystopian novel, full of plot twists and drama. How did we manage? How did faculty adapt? Trained as scholars in our niche areas, faculty already feel woefully underprepared to address mental health realities with our land-based classes. How can we pay the emotional costs of teaching? As Glinda explained to an uncertain Dorothy, “You are capable of more than you know” (The Wizard of Oz, 1938). Our work can begin by recognizing and honoring the trauma that both students and faculty have experienced, perhaps even strategically including class time to discuss these realities. Opening a dialog with our classes and our fellow faculty about our experience is valuable.

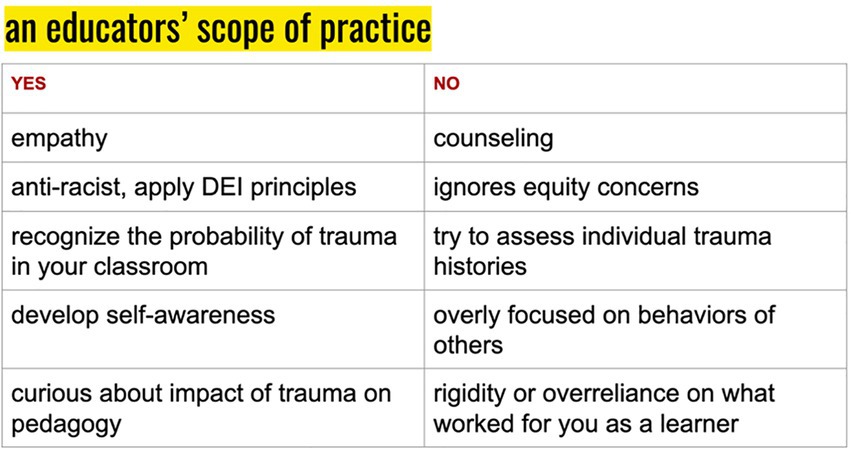

We can find a healthy path forward by also learning about trauma-informed teaching (Mcmurtrie, 2020). In April 2020, Dr. Karen Costa shared helpful and refreshingly clear guidelines (Figure 2) regarding what we can and should not do as educators (Costa, 2020).

Figure 2. An educator’s scope of practice, used with permission from Dr. Karen Costa (@a2FyZW5yYXljb3N0YUB0d2l0dGVyLmNvbQ==). DEI refers to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

While faculty are (usually) not credentialed counselors, we are all capable of empathy. We can work on our own self-awareness and understand how, in the time of a global pandemic, trauma is likely. We can also continue to dialog with our peers about this unexpected work. We are capable of being anti-racist champions for diversity, equity, and inclusion. And we can practice compassion, for both our students and ourselves.

Lessons learned

Teaching is emotional labor. During these uncertain times, the labor costs have been particularly high and resulted in imbalance and fatigue. Since March 2020, I have come to know this truth in profound ways. Rather than ignore the emotional part of my professional life, I choose to embrace it.

The pandemic required a lot of creative effort; one lesson learned is that we can benefit from sharing our teaching experiences and solutions with our peers. I have also learned how important it is to take time away from work to care for myself and my family. Working in my small backyard garden has been a salve; seeing plants grow and bloom gives me hope. And I’ve learned to establish healthy boundaries with my students. Rather than trying to be the counselor they might need, I readily refer them to student mental health resources on campus and encourage them to take care of their mental health.

Although we have returned to more comfortable days in classrooms and labs, we should not forget the lessons learned in and from the pandemic. We can honor our feelings and recognize their validity. We can choose to be flexible. We can support our fellow faculty and mentor those with less experience. In our commitment to our students, our scholarship, and our colleagues, we have a wealth of reserves from which to draw. By learning about and managing the emotional labor of teaching, we can guard against professional bankruptcy and enable fulfilling careers as educators.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Auger, G. A., and Formentin, M. J. (2021). This is depressing: the emotional labor of teaching during the pandemic spring 2020. J. Mass Commun. Educ. 76, 376–393. doi: 10.1177/10776958211012900

Believe in Students (2020a). Believe in Students. Available at: https://believeinstudents.org/ (Accessed February 15, 2023).

Believe in Students (2020b). FAST fund – Faculty and students together. FAST fund – Faculty and students together. Available at: https://www.thefastfund.org/ (Accessed February 15, 2023).

Berheide, C. W., Carpenter, M. A., and Cotter, D. A. (2022). Teaching College in the Time of COVID-19: gender and race differences in faculty emotional labor. Sex Roles 86, 441–455. doi: 10.1007/s11199-021-01271-0

BestSelf Co . (2020). Icebreaker Deck. BestSelf Co. Available at: https://bestself.co/products/icebreaker-deck (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Blackboard Inc . (2022). Blackboard Collaborate. Available at: https://www.blackboard.com/en-eu/teaching-learning/collaboration-web-conferencing/blackboard-collaborate (Accessed December 9, 2022).

Brown, E. L. (2011). Emotion Matters: Exploring the Emotional Labor of Teaching. PhD Dissertation from University of Pittsburgh. Available at: http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/7209/ (Accessed March 25, 2011).

Costa, K. (2020). Trauma-Aware Online Teaching. Available at https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/18yutlwaPSfPxH4xS9RDzQ9rnRn5PWMUT-m2-mnRwoz4/edit?usp=sharing (Accessed February 15, 2023).

Dunkel, W. (1988). Wenn Gefühle zum Arbeitsgegenstand werden: Gefühlsarbeit im Rahmen personenbezogener Dienstleistungstätigkeiten. Soziale Welt 39, 66–85.

Eyler, J. (2020). Joshua Eyler on twitter: “This is such an important point. The psychological impact of walking into a room full of certainly uneasy and possibly traumatized students wearing masks and looking to us for safety and guidance will be immense.” / twitter. Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/joshua_r_eyler/status/1258597918883405827 (Accessed February 15, 2023).

Hargreaves, A. (2001). Emotional geographies of teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 103, 1056–1080. doi: 10.1111/0161-4681.00142

Hebson, G., Earnshaw, J., and Marchington, L. (2007). Too emotional to be capable? The changing nature of emotion work in definitions of ‘capable teaching. J. Educ. Policy 22, 675–694. doi: 10.1080/02680930701625312

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Horner, C. G., Brown, E. L., Mehta, S., and Scanlon, C. L. (2020). Feeling and acting like a teacher: Reconceptualizing teachers’ emotional labor. Teach. Coll. Rec. 122, 1–36. doi: 10.1177/016146812012200502

Lieberman, M. (2018). Q&A: Strategies for better assessments in online learning. Inside Higher Ed. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2018/10/31/qa-strategies-better-assessments-online-learning (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Mansfield, E., and Conlon, S. (2020). Coronavirus pushed learning online, but half of US lacks access. USA Today. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/04/01/coronavirus-internet-speed-broadband-online-learning-school-closures/5091051002/ (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Mcmurtrie, B. (2016). To Diversify the Faculty, Start Here. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available at: http://chronicle.com/article/To-Diversify-the-Faculty/237010/ (Accessed August 25, 2016).

Mcmurtrie, B. (2020). What does trauma-informed teaching look like? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/What-Does-Trauma-Informed/248917 (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Neuhaus, J. (2020). Remote teaching while introverted. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/Remote-Teaching-While/248661 (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Protopsaltis, S., and Baum, S. (2019). Does online education live up to its promise? A look at the evidence and implications for federal policy. Available at: http://mason.gmu.edu/~sprotops/OnlineEd.pdf.

Respondus (2022). Respondus LockDown Browser. Available at: https://web.respondus.com/he/lockdownbrowser/ (Accessed December 9, 2022).

Sander, L., and Bauman, O. (2020). Zoom fatigue is real — here’s why video calls are so draining. Available at: https://ideas.ted.com/zoom-fatigue-is-real-heres-why-video-calls-are-so-draining/ (Accessed June 9, 2020).

The Wizard of Oz (1938). Available at: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0032138/fullcredits (Accessed June 10, 2020).

Waldbuesser, C., Rubinsky, V., and Titsworth, S. (2021). Teacher emotional labor: examining teacher feeling rules in the college classroom. Commun. Educ. 70, 384–401. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2021.1936097

Webex (2022). Webex Meetings. Available at: https://www.webex.com/meetings.html (Accessed December 9, 2022).

Whitteck, E. (2020). Erin Whitteck, Ph.D. on twitter: “Faculty will need to be prepared both in terms of professional development, but also mentally to teach under these conditions. Many social norms of the classroom will be different, that will take up a lot of bandwidth for both students and faculty.” / twitter. Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/EWhitteck/status/1258558004946972673 (Accessed February 15, 2023).

Zoom Video Communications (2023). Zoom. Available at: https://zoom.us/ (Accessed December 9, 2022).

Zygomatic (2020). Word cloud generator. wordclouds.com. Available at: https://www.wordclouds.com/ (Accessed June 10, 2020).

Keywords: perspective, teaching, chemistry, emotional labor, pandemic

Citation: Jones RM (2023) The unexpected emotional cost of teaching chemistry in a pandemic. Front. Educ. 8:1120385. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1120385

Edited by:

Sibel Erduran, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Keri Colabroy, Muhlenberg College, United StatesMary Konkle, Ball State University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Jones. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebecca M. Jones, cmpvbmVzMjJAZ211LmVkdQ==

Rebecca M. Jones

Rebecca M. Jones