- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

This paper reports on a content analysis of Saudi Arabian high school Family Education curriculum, examining how girls and women are represented. The textbooks were published after the launch of the Saudi Vision 2030 reform initiatives. Considering previous research on school textbooks’ contributions to youth self-image formation and confidence development, the Family Education curriculum was optimal for examining contemporary representations of Saudi girls and women. Content analysis was conducted on the Vision 2030 documents to discern specific principles of women’s empowerment. This study presents a framework highlighting significant elements that provide a better understanding of inequalities in the textbooks portrayals of women that guided the recommendations for future changes. Four themes were constructed: Awareness of Women’s Rights and Responsibilities, Exclusion, Stereotypes, and Lack of Female Role Models. Together, these themes indicate inklings of positive change, as well as enduring inequality. They suggest a gap between the 2030 Vision goal to empower Saudi women and high school textbooks which effectively underrepresented women as equal partners in the country’s development. Revision of textbooks is required in light of the country’s new vision.

1. Introduction

As questions around women’s empowerment have gathered momentum around the world over the past few decades, international institutions such as the World Bank and the United Nations (UN) have taken concrete steps towards empowering women. The World Bank has placed the empowerment of women as a key element in reducing poverty, as the UN has adopted the principle of women empowerment as integral to achieving its sustainable development goals (SDGs). The efforts of these international development agencies, and the efforts of various governments, scholars and activists have contributed to propelling the issue of women empowerment into theoretical, practical, and political awareness (Alasgah and Rizk, 2021). One example is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), which, in 2016, pledged to empower women by undertaking several reforms that have the potential to transform women’s socio-economic, political, and cultural positions in the country (Topal, 2019). These pledges were part of Vision 2030, launched in April 2017, as a reform initiative that centers on differentiating the Saudi economy and developing the education and tourism sectors. The reforms in Saudi Arabia, especially those that target empowering women, are changing Saudi women’s futures in various ways, for example, granting women civil statute such as registering children’s births, previously restricted to fathers; increasing professional and developmental opportunities; removing restrictions to participation in a variety of sectors—all of which help bridge the employment gap between genders. The education sector has received special attention through launching new programs and initiatives aimed at revising the curriculum and developing teachers. However, despite these efforts, gender inequalities continue to remain tangible in several contexts such as education.

1.1. A gap in the literature

A persistent but often inconspicuous source of gender inequity is educational curricula, within which outdated, inequitable attitudes and stereotypes not only play a role in distorting the perceptions of gender in modern society but are also a threat towards achieving gender equality and empowerment of all girls and women (Kahveci, 2010; Hussain and Jullandhry, 2020; Tam et al., 2020). Some argue for the importance of incorporating themes of non-traditional gender roles early in the education system (Ruiz-Cecilia et al., 2021), where cognitive growth in early childhood is significant in organizing and maintaining gender role behaviors and establishing gender identity in later life (Kohlberg, 1966). While the adolescent years are challenging time for many students, characterized by changes in behavior expectations, possibilities, and consequences (Green et al., 2021), high school curricula in particular may affect adolescent girls’ life choices (Ullah and Skelton, 2013), career paths, and self-esteem that implies self-worth and accepting oneself, and identity according to the gendered role models to which they are exposed (Griffith, 2010). As evidence in the literature suggests that educational curricula play a role in perpetuating gender-related stereotypes, which in turn hinders women’s empowerment in many countries around the world, this study turns analytic attention to Saudi Arabia’s high school curricula to examine representations of girls and women. While a growing body of literature exists on the impact of Vision 2030 on the economic sector (e.g., Nieva, 2015; Alkhaled and Berglund, 2018; Topal, 2019; Omair et al., 2019; Aqel, 2020; Alasgah and Rizk, 2021; Al-Qahtani et al., 2021b); as aligned with international goals (Okonofua and Omonkhua, 2021); in empowering Saudi women in tourism (Alasgah and Rizk, 2021) and higher education (Al-Qahtani et al., 2021a), few studies have examined how high school curricula aimed at girls reflect Saudi Vision 2030 goals for women’s empowerment (such as Topal, 2019; Omair et al., 2019; Al-Qahtani et al., 2021a). However, these studies focused on investigating women empowerment in the economic sector. This study contributes to the gap in the literature.

1.2. Research overview

This study set out to discern how principles of equality and empowerment currently valued in the government and society are reflected within contemporary high school curricula, and how high-level national reforms may or may not be reflected in the adolescent day-to-day. The study was guided by the following research questions:

(1) How are girls and women portrayed in the Saudi Arabian Family Education curricula?

(2) What principles of empowerment are evident in the Family and Education curricula in light of Saudi Vision 2030?

To answer the research questions effectively, considering a deficit in previous research analyzing Saudi high school curricula for principles of women’s equality and empowerment, this study involved a two-part content analysis. First, the documents comprising Saudi Vision 2030 were analyzed with a focus on the principles of women’s empowerment to provide a conceptual framework specifically relevant to Saudi women’s empowerment. The framework was then compared to the UN, Women Business and Law 2020, and other regional documents that claim to codify women’s empowerment. These documents contain indicators and principles of women empowerment, and describe measures taken by countries to minimize barriers that prevent women’s participation in vital sectors. Many of these principles are highlighted in the Saudi Vision 2030 documents. For example, Women, Business and Law identify eight indicators of women’s empowerment in economics—such as mobility, marriage, and entrepreneurship—all of which are present in Vision 2030 documents. The resulting constellation of principles formed a culturally-relevant conceptual frame (see Figure 1) which was then used to analyze the content of the three Saudi high school textbooks. More details will be provided on page 5–6.

1.3. Literature review

At the disciplinary intersection between education, curriculum and women’s studies, literature was reviewed across these three fields to provide context for studying principles of empowerment reflected in school curricula and representations of girls and women.

1.3.1. Education and empowerment

Studies conducted in various countries around the world have shown that education can contribute to women’s empowerment by increasing awareness of rights and increasing participation in the labor market (Hussain and Jullandhry, 2020; Tam et al., 2020). Academic empowerment can have a positive direct effect on the economic and social empowerment of women as it can significantly contribute to women’s capacity development (Al-Qahtani et al., 2020). For example, in a study conducted in India, Shioyama (2020) examined how work experience education (WEE) in secondary schools contributed to self-improvement and empowerment of women. The results of the study revealed that the WEE provided in schools led to women empowerment in three aspects providing access to resources, job opportunities, and acquisition of decision-making skills. In the health field, for example, sex education has been found to lead to women’s empowerment, including informing women about healthcare and reducing risky sexual behaviors (Najmabadi and Sharifi, 2019). According to the literature, education is employed as a strategic development objective, particularly in developing nations, to empower females by raising their self-awareness and boosting their self-esteem, which will help rise participation in labor market. The development of new curricula often reflects government orientation and social value (Miles, 2020). Therefore, deciding what to teach and to whom a reflection of what a government believes is often will benefit society.

1.3.2. Curriculum and gender stereotypes

Education can implicitly or explicitly promote and reinforce gender inequality through the curriculum (Smith, 1991) by positioning boys and girls unequally and describing them as gendered subjects (Durrani, 2008). A stream of research has studied how educational curricula contribute to gender discrimination and promote certain gender stereotypes (Halim and Rubl, 2009; Erlman, 2015; Ledman et al., 2018; Dalati et al., 2020; Salm et al., 2020). According to a recent study by Becker and Nilsson (2021), females comprise only 30% of images in general chemistry textbooks (2016–2020), and 3% in science, technology, engineering, math, and medicine (STEMM) textbooks. An overrepresentation of men in science textbooks may reflect and perpetuate unconscious gender bias in STEM. In Japan, Tam et al. (2020) claimed that, “Gender stereotyping is widespread in STEM industries and education reducing girls’ confidence and interest in ICT and steering them away from ICT education and careers” (p. 1). In Turkey, Kahveci (2010) explored the effectiveness of chemistry and science textbooks in terms of reflection of reform. To achieve the aims of the study, the author used themes such as gender equity, readability level, and science vocabulary to provide a conceptual framework for analyses. The results of the study revealed that Turkish textbooks included unfair gender representations and inequity.

Serra et al. (2021) investigated how young people perceived Physical Activity and Sports Science (PASS) in Spain, found that people favored masculine characterization. The authors warned that since the social representation (SR) of sports and physical activity favored masculine representation, it might increase the risk of exercising symbolic violence against women. The authors recommended bringing about a profound change in the curriculum that will modify the SR of physical activity. Added that the current contemporary state of PE not only continues to reinforce gender power relations but also holds the potential to empower young women’s sense of self. Therefore, it is important to develop the next generation of teachers who will not only challenge the status quo but also include girls’ voices, involve them as co-collaborators in curriculum design, and work with them to advocate for change. As such, the converse of perpetuating gender stereotypes is that curricular content can also serve to reduce stereotypes of all kinds, including gender. Tam et al. (2020) examined the effectiveness of STEM education in promoting student development and reducing gender stereotyping in information and communication technology (ICT) among female students in Hong Kong. The results of the study revealed that having inquiry-based models of learning, especially those that focused on students’ problem-solving skills and analytical skills greatly led to a reduction in ICT-related gender stereotypes. Ruiz-Cecilia et al. (2021) also analyzed the role that textbooks used to teach English as a Foreign Language (EFL) played in perpetuating stereotyped gender roles in Spanish high schools and found that the textbooks propagated gender stereotypes. This literature shows that unequal representation of women in the curriculum can contribute to women’s low participation in certain activities and/or the avoidance of certain disciplines as they affect the development of lower self-esteem and less confidence in their abilities.

In the few years since the release of Saudi Vision 2030, various studies have published reports and analysis of the outcomes of some of the programs and initiatives launched to achieve the Vision’s objectives. Most of these studies concentrated on measuring and evaluating the impact of Vision 2030 initiatives and programs on achieving the Vision objectives, focusing mainly on the economic sector (e.g., Nieva, 2015; Alkhaled and Berglund, 2018; Topal, 2019; Omair et al., 2019; Al-Qahtani et al., 2020, 2021a,b; Aqel, 2020; Alasgah and Rizk, 2021; Okonofua and Omonkhua, 2021). Al-Qahtani et al. (2021a) recruited 160 Saudi women working in higher educational institutions and conducted a factor analysis across various indicators of women’s personal empowerment. The results revealed that factors such as self-esteem and self-efficacy, one’s belief about their capabilities in making differences, that were the most important indicators of women’s personal empowerment. Al-Qahtani et al. (2020) also measured the impact of women’s academic and political empowerment on the socioeconomic and managerial empowerment of women in Saudi Arabia. The results of the study revealed that political empowerment characterized by policies and laws that favor women has a positive effect on the economic and managerial empowerment of women. A cross-sectional study conducted by Al-Qahtani et al. (2021b) examined women empowerment among 5,587 academic and administrative staff from 15 Saudi Universities. Measuring women empowerment across three dimensions—personal, social/relational, and environmental/workplace—within Saudi universities. The personal dimension focused on measuring women’s self-esteem and self-efficacy. The social dimension measures women access to services, freedom of mobility, freedom of making decisions, and economic empowerment. And the environment dimension measures women access to knowledge and support, access to opportunities and promotion, and participating in political life. The researchers found significant differences in total empowerment scores between academic and administrative staff, where women’s empowerment was higher among academics as compared to administrative staff. Faculty in universities have more access to resources and support more than the administrative staff. Further, usually, the administrative staff have lower education level education compared to the academic staff. This shows that education has an effect on empowering women and rai their awareness about their rights.

Alasgah and Rizk (2021) studied the empowerment of women in the tourism sector in Saudi Arabia in line with Vision 2030. Discussing various constituents as well as constraints of empowerment in the tourism sector of the country, the authors concluded that even though women are underrepresented in the tourism sector compared to men, significant improvements have been made in the level of empowerment of Saudi women in the sector. The authors concluded that age and educational level and the Kingdom’s 2030 vision played a significant role in improving women’s empowerment in the sector. Aqel (2020) shed light on the reality of empowerment of female students at Majmaah University, conducting interviews with university leadership to understand the empowerment requirements from the perspective of leadership. The author found that female students in the university were empowered only for those activities that fit their nature and identity and that there were not enough activities that take into account individual differences. The author recommended the expansion of activities that take into account the peculiarities of male and female students, and their respective needs, based on principles of equal opportunities and individual decision-making in terms of participating in the activities.

Okonofua and Omonkhua (2021) highlighted how the reforms in Saudi Arabia, especially those targeted towards empowering women, are in line with the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the United Nations (UN) which aim to promote gender equality. By highlighting various studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, the authors highlight the significant implications of the findings for the African region. In other words, the authors believe that the results of the studies conducted in Saudi Arabia can be useful when designing programs and policies to enhance women’s empowerment in other settings around the world. Omair et al. (2019) presented a composite index comprising 54 indicators that measure Saudi women’s participation in national development and measure the state of gender equality in the country. To provide a well-representative index, the authors constructed an index using techniques such as national surveys, focus groups, and pilot testing. The authors contend that the index developed is beneficial for decision-makers when allocating strategic policies to increase the participation of women in development. This literature suggests that Saudi Arabia’s reforms to support women, initiated as a part of modernizing the country’s economy, have implications for women’s empowerment, but questions remain as to what extent the reforms have been useful in actually contributing to women’s empowerment.

2. Materials and methods

This study employed a two-part content analysis to examine representations of girls and women in the three Saudi high school textbooks of the Family Education curricula in light of Vision 2030. A lack of previous research analyzing Saudi high school curricula for principles of women’s equality and empowerment motivated this double analytic approach. The first step was content analysis of recent Saudi Government vision documents to discern a framework of principles with which to contextualize the second step: content analysis of the three high school textbooks of the Family Education Curriculum. Content analysis, defined as “a strict and systematic set of procedures for rigorous analysis, examination and verification of the contents of written data” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 475). It has been effective in prior research conducted to understand social and family issues and phenomena and analyzing texts, along with images and lexical items (Ruiz-Cecilia et al., 2021), the process begins with discerning codes, then codes categories, and then broader patterns across the data set (Margolis and Zunjarwad, 2018). Content analysis was selected for this study because it enabled an in-depth understanding of the content of textbooks: both written text and images. As the purpose of this study was to extract women’s empowerment principles, gender was the unit of analysis of both analytic steps.

2.1. Step 1: discerning a conceptual framework

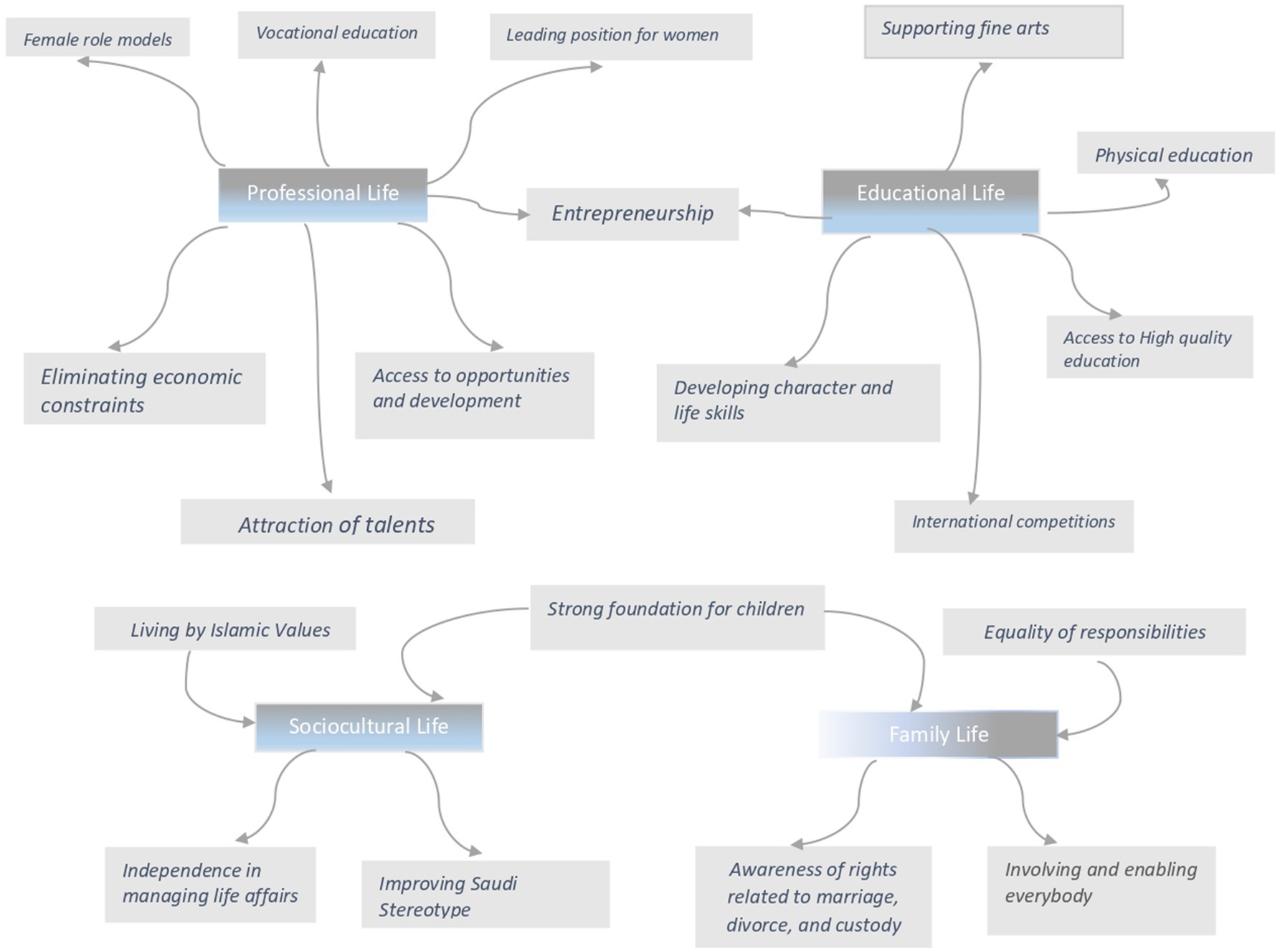

The need to understand the principles of equality and empowerment currently valued in the government and society, as embodied in Vision 2030, necessitated the first research step: content analysis of the main official Saudi Vision 2030 document. The document was coded for references to gender or equality between genders. In Saudi Vision 2030, gender is a term used to reference to men and women. Three sections of particular interest were Thriving Economy, Vibrant Society, and Ambitious Nation, each of which included particular programs, initiatives, aims, and principles. The gender-meaningful codes that were discerned can be understood as indications of women’s empowerment. They were functionally organized into code clusters around four life domains: Family Life, Sociocultural Life, Educational Life, and Professional Life (see Figure 1). Professional Life includes principles related to women’s participation in the workforce: attracting talent of both genders, increasing enrolment in vocational education, female role models, and leadership positions for women. Educational Life includes equal opportunities for high-quality education, participation in physical sports and fine arts, and participation in international competitions, including math and science. Sociocultural Life focuses on increasing the inclusive participation of women beyond their families, raising awareness of the new civil rights, identifying women as central to improving Saudi stereotypes, and raising awareness of guiding Islamic values as foundational to the Vision 2030 goals, as well as to building strong families. The principles of Family Life include equality of responsibilities and participation, and raising awareness of rights related to marriage, divorce, and custody.

The next step was to analyze other documents related to women’s empowerment specifically, Vision Realization Office (2021), Economic and Developmental Affairs Council in Saudi Arabia 2021, and Women Business and the Law 2020, which covered economic, political, education, labor, familial, or legal topics—to examine how key words, concepts, or indicators of women’s empowerment in different domains would contribute to the codes discerned in the Vision 2030 document in Figure 1. These documents echoed similar codes. For example, in the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2020), one of the economic indicators is entrepreneurship, which identifies constrains to women’s participation in businesses; similarly the Saudi Vision 2030 document emphasizes entrepreneurship and the government’s “commitment to boost small family business and SME entrepreneurship” (p. 35).

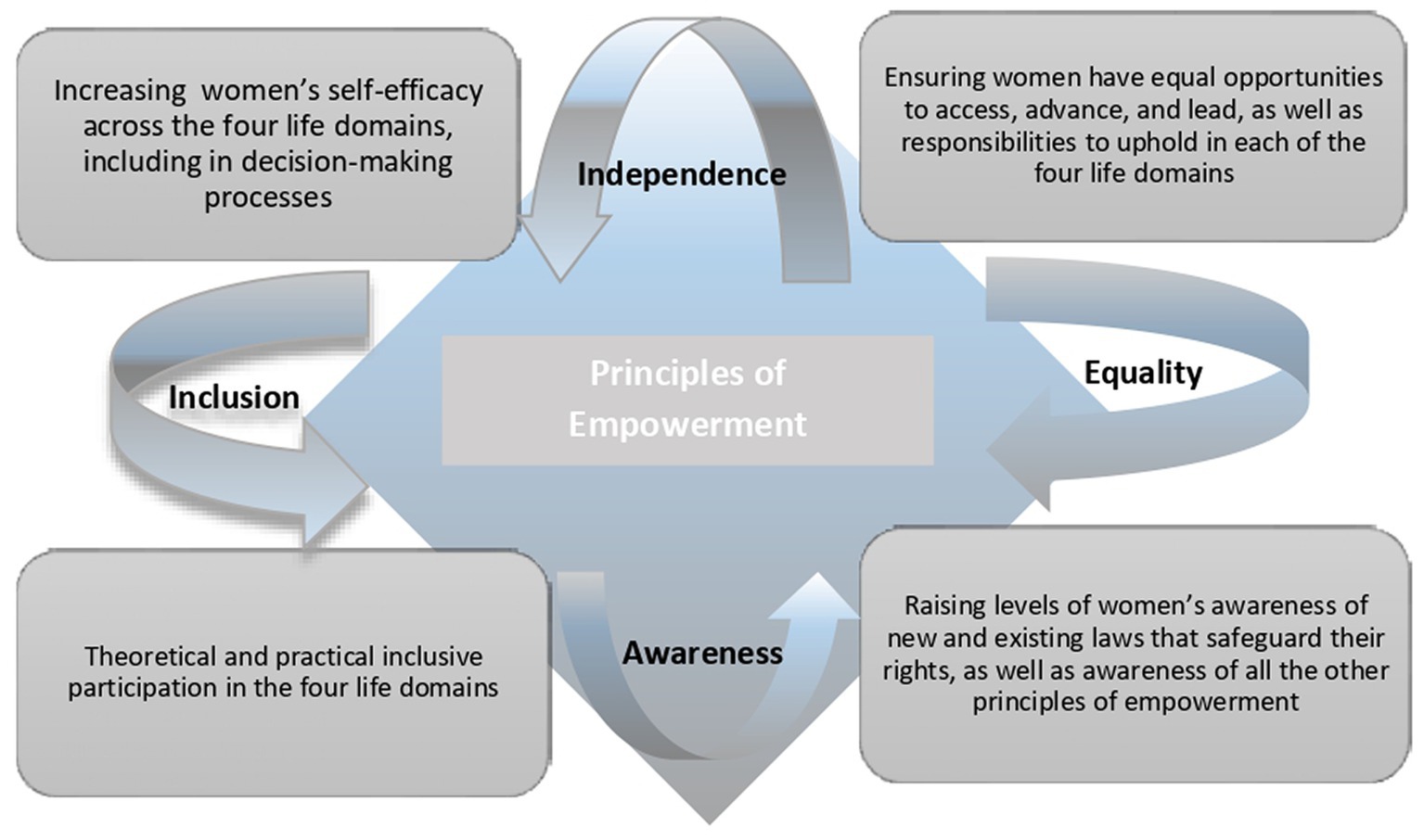

The code clusters were further developed into distinct themes of Awareness, Independence, Equality, and Inclusion, as thematic principles of women’s empowerment in Vision 2030. These primary thematic principles can be defined as follows. Awareness is defined as raising levels of women’s awareness of new and existing laws that safeguard their rights, as well as awareness of all the other principles of empowerment. Independence refers to increasing women’s self-efficacy across the four life domains, including in decision-making processes. Equality is a principle that aims to ensure women have equal opportunities to access, advance, and lead, as well as responsibilities to uphold in each of the four life domains. Inclusion refers to theoretical and practical inclusive participation in the four life domains (Figure 2).

Conceptual framework construction generally aims to serve two purposes: argumentation and explanation (Crawford, 2020). Argumentation focuses on explaining why the questions raised in the study are important (Ravitch and Riggan, 2017). This current framework provides evidence that indicators of women’s empowerment are included as direct or indirect objectives of the Vision 2030 reform plan, and they coalesce into four thematic principles, hence justifying the need to investigate the existence of these principles in the Saudi family education curriculum. As such, this argument supports the study’s research questions. In terms of explanation, the framework illustrates how these aspects of women’s empowerment are tethered to each area of life—sociocultural, professional, educational, and family (see Figure 1)—and the relationships between them because each situated aspect points to a larger theme, as a principal of women’s empowerment: Awareness, Independence, Equality, and Inclusion. This framework was an effective lens through which to analyze the textbooks and understand the research findings in relation to extant literature on women’s representation in curricula.

2.2. Step 2: identifying and analyzing the sample

The functional purpose of analyzing the Saudi Vision 2030 documents was to provide a framework of sensitizing concepts towards investigating how girls and women are depicted in recently-published high school textbooks. The crux of this research was to examine the empowerment principles of the conceptual frame as expressed in three textbooks of a Saudi high school Family Education curricula. Given that students spend the vast majority of their essential young adult years in schools, this understanding illuminates the role that the school curriculum plays in molding youthful identities and agencies towards adult roles. Once the conceptual frame had been established, the next step was identifying the curriculum to be analyzed. The sample selected included three required high school textbooks for the Family Education curricula (grades 10–12):

1. Life Skills and Family Education, Grade 10, Saudi Ministry of Education (2020).

2. Family and Health Education, Grade 11, Saudi Ministry of Education (2018).

3. Health and Female Education, Grade 12, Saudi Ministry of Education (2021).

The three textbooks were chosen for two main reasons. First, as the latest editions of official administration that were written after the release of Saudi Vision 2030. Second, all three texts focus on family and gender topics. The Life Skills and Family Education (Grade 10) is intended to prepare high school students—both boys and girls—to become citizens aware of their pivotal roles in family and social life, to help enhance the students’ self-confidence, to develop love for professional work, and to foster the abilities to think critically and creatively. The Family and Health Education (Grade 11) and Health and Female Education (Grade 12) textbooks focus on providing high school girls with general topics including health, dealing with life pressures, clothing, motherhood and children, and beauty. A specific purpose identified in the Family and Health Education (Grade 11) textbook for girls is “the Ministry of Education’s keenness to prepare a high school student as a mother who is aware of her pioneering role in life” (p. 6). Since the purpose of the research is to analyze how girls and women are portrayed in high school curricula in light of Saudi Vision 2030, the textbooks of this curriculum are particularly relevant and well positioned to help achieve the study’s objectives. It was hypothesized that women’s empowerment and equality would be evident in the Family Education curricula, consistent with the new roles of Saudi women promoted in Vision 2030.

2.3. Step 3: content analysis of the sample

Content analysis of the three textbooks began with considering the four themes identified in the conceptual framework as sensitizing concepts: Awareness, Independence, Equality, and Inclusion. With these themes in mind, and the unit of analysis being gender, the researcher considered any image, text, terminology, activity, example, or scenarios provided in the textbooks that reflected gender in any way, including identifying, labeling, or representing. After familiarization with the textbooks’ content in relation to gender, the next step was to analyze each of the three textbooks in detail to code features of the text related to gender. These labels, words, texts, images, activities, scenarios, or phrases were highlighted and examined in light of the themes highlighted in the framework. The coding process was repeated twice to check for consistency. Upon second analysis, patterns in the data were examined, including how the codes were clustering into categories. These categories were then analyzed as initial or candidate themes and given tentative names and definitions. The next step involved re-reading the textbooks with the themes in mind and examining how each code fit within a theme. The four final themes constructed from the data are defined and discussed in the sections that follow.

3. Results

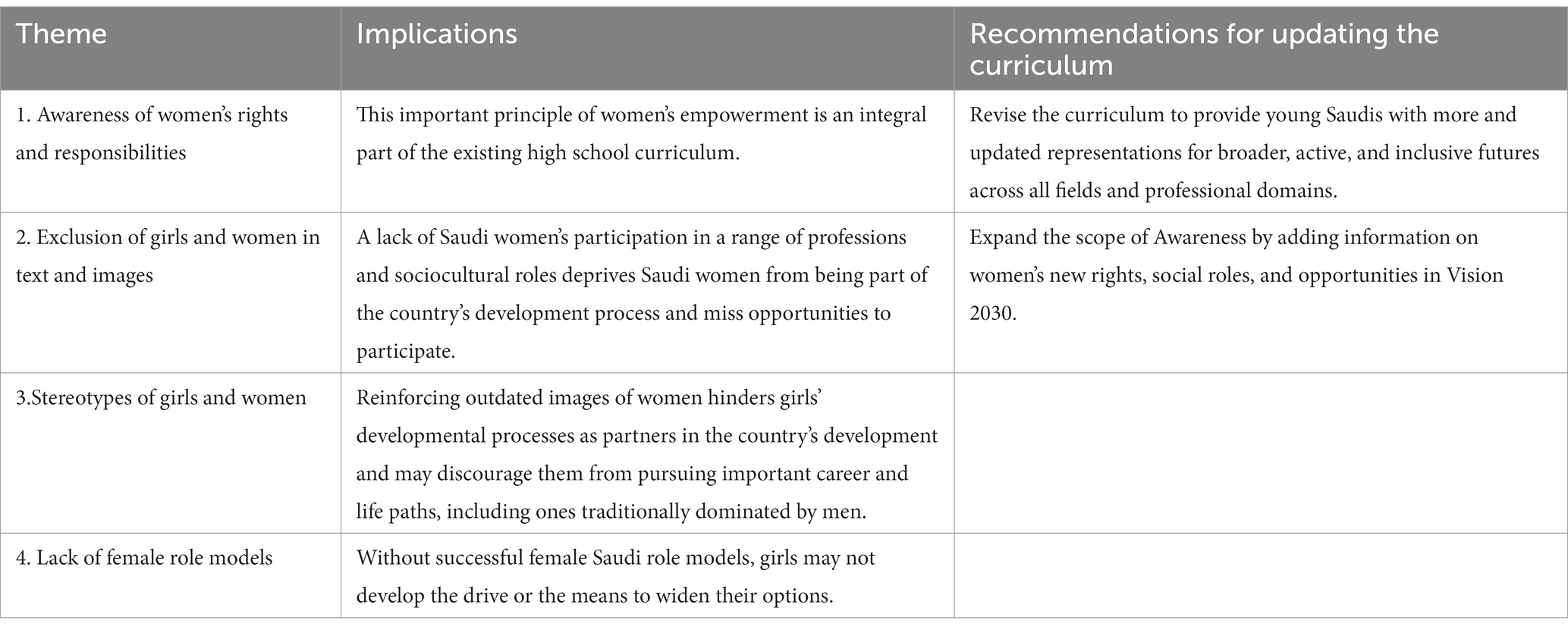

Content analysis of texts and images revealed that while there was an emphasis in the textbooks on awareness of women’s rights and responsibilities, many of the words, texts, images, activities, scenarios, and phrases showed men and boys in more active roles than women and girls, which indicated exclusion. As such, the analysis yielded four broad themes as expressions of dis/empowerment of girls and women in the high school textbooks: Awareness of Women’s Rights and Responsibilities, Exclusion, Stereotypes, Lack of Female Role Models. Together, these themes shed the light on expectations of girls growing into social roles, their potentials and restrictions of potentials, and evidence of both positive change and enduring inequality.

3.1. Theme 1. Awareness of women’s rights and responsibilities

The first theme generated from the textbooks is Awareness, specifically of women’s rights and responsibilities. The textbooks aim to provide students with the skills needed to manage family and work, along with reminders of their roles as Saudi citizens. In the textbooks, there are several examples in which awareness of new rules related to marriage, including those related to acceptable ages for marriage for both males and females, are presented. For example, the Life Skills and Family Education textbook (Grade 10) describes a Royal Decree that was issued in 2020 prohibiting marriage for anyone under the age of 18:

Like other topics of interest to the country and their citizens, the Saudi government forbids marriage to anyone under the age of 18 male or female. Further the Decree includes holding education courses for those who are about to marry to raise awareness about the psychological or social damages that early marriage may entail (Saudi Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 27). This excerpt is an example of the Awareness theme in making young people aware of the drawbacks of early marriage.

Another example is emphasis on the nuclear family, in line with traditional values. One of the main pillars of the Saudi Vision 2030 is building vibrant society in which all members feel a sense of belonging and purpose: “Members of this society live in accordance with the Islamic principles of moderation, are proud of their national identity and their ancient cultural heritage, enjoy a good life in a beautiful environment, are protected by caring families and are supported by an empowering social and health care system” (Saudi Arabia Government, p. 12). The textbooks consistently explained the roles of both parents in the family unit, emphasizing that family is a partnership between a wife and a husband (pp. 31–32). The textbooks described family rights and responsibilities in terms of both gender and religion: “Islam is distinguished by distributing rights and duties to spouses in a way that suits the role of each of them” (Life Skills and Family Education, Grade 10, Ministry of Education p. 35), thus illustrating prescribed roles for each gender.

In the Life Skills and Family Education (Grade 10), required for both boy and girl students, there is a whole unit dedicated to reviewing citizen rights and obligations. The unit content covers topics such as: systems application and maintenance, public manners, citizenship, responsible behavior, and volunteering. The unit discusses the individual’s responsibilities toward their society and provides examples of the importance of volunteering: one of the Vision 2030 goals is to reach 1 million volunteers by 2030. The unit also describes the role that Saudi Arabia played during the COVID-19 pandemic and the unity of its citizenry. Yet, the unit fails to explicitly provide texts or images related to Saudi women and their active roles as Saudi citizens.

This theme of Awareness reflects actions taken towards a major objective of Vision 2030—to include Saudi women in the development of the country through equal partnership with men socially, economically, and politically—that includes launching educational programs and initiatives, increase economic opportunities, and removing some of the legal impediments that previously hindered women’s participation in the economic. Raising citizens’ awareness is part of the country’s developmental transition that includes improvement and modification of aspects of the current system that hinder the inclusion of Saudi women. Therefore, it could be argued that one of the topics covered in the textbooks is raising young women’s awareness of their rights and responsibilities, with awareness potentially leading to empowerment.

3.2. Theme 2. Exclusion of girls and women in text and images

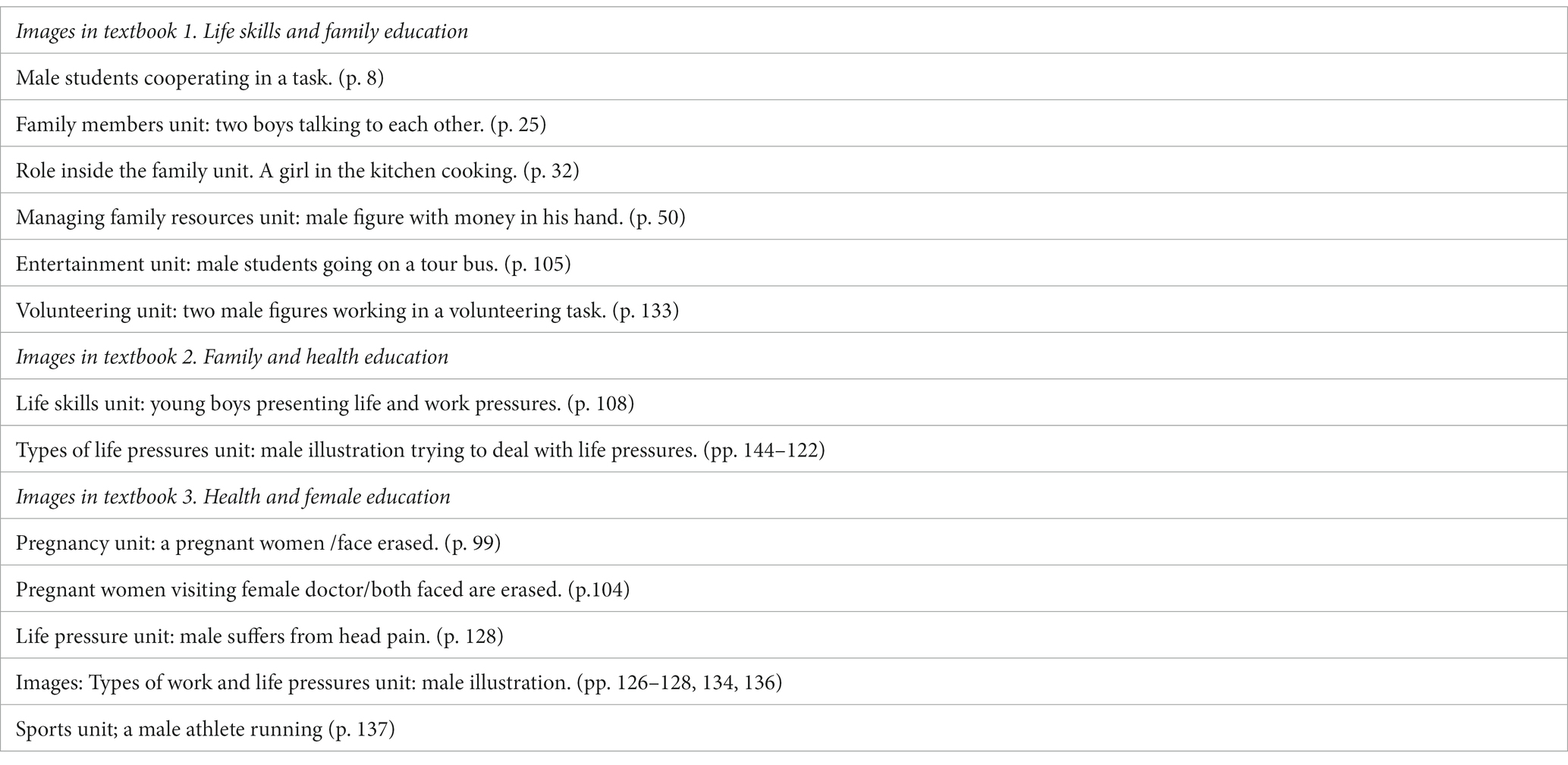

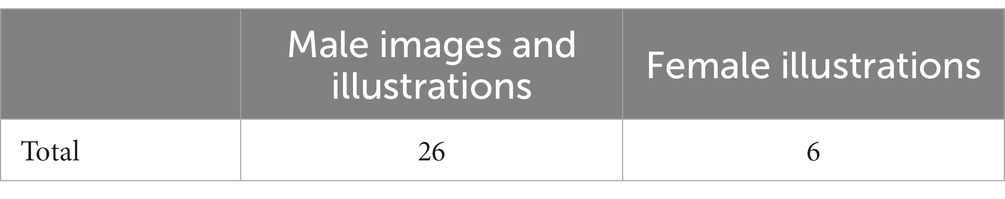

Across the three textbooks, girls and women were excluded from many examples, scenarios, and activities that represent prestigious jobs and STEM majors. Male figures were predominately referenced as examples of specific profession or life issues. In the Life Skills and Family Education textbook (Grade 10), for instance, the exercises and examples of men exceeded examples of those referencing women; images featuring girls occurred once to every six images featuring boys. All images found in the Life Skills and Family Education textbook were images or illustrations of boys or men, with one exception being an image of a female figure in the kitchen, cooking (Saudi Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 32). All the images provided in the other two textbooks, Family and Health Education (Grade 11) and Health and Female Education (Grade 12), were either illustrations of male figures or female figures with no facial features. Table 1 provides examples of images in the textbooks that exclude girls and women.

Even in the two textbooks written specifically for female students, the number of images and illustrations of males exceeded the numbers of female figures (Table 2).

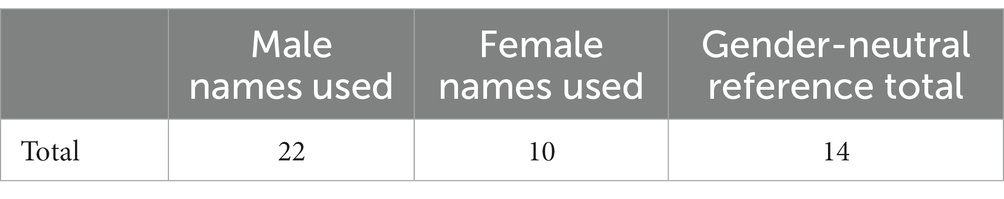

In addition, the numbers of examples where male names were used in examples exceeded the numbers of female names used (Table 3).

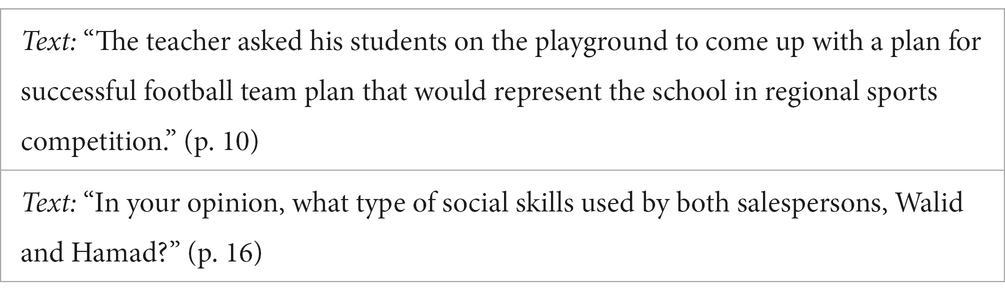

Even though that the Life Skills and Family Education textbook (Grade 10) was assigned to both genders, females were excluded from examples on topics related to sport activities, business, or entrepreneurship. Table 4 provides two examples.

The analysis of the three textbooks showed that women are excluded from almost all text, images, examples, and scenarios related to real life issues and professions in the public domain.

3.3. Theme 3. Stereotypes of girls and women

The third theme indicated that girls and women are presented within the textbooks in ways that perpetuate a stereotypical image of the role of Saudi women as a wife and mother, with limited professional specializations. For example, women were excluded from STEM majors or examples of women engaging in commercial or industrial jobs. Most often, examples of women’s roles were restricted to within family, where their rights and obligations were presented as mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters. In Life Skills and Family Education textbook (Grade 10), for example, a scenario is presented of a male student and male teacher working in science lab (Life Skills and Family Education, Grade 10, Ministry of Education, p. 9), which may serve to reinforce the stereotype that men are better suited for science. A text excerpt from that same textbook reads: “Khaled is a businessman, he works in a large corporation, and he has many tasks… And his wife bears the responsibility of the house and children.” (Saudi Ministry of Education, p. 46). Across the three textbooks, males are presented in the text, images, and activities, as businessmen, engineers, doctors, scientists, teachers, salespersons, company owners, and interior designer, and engaging in physical activities and sports (see Table 3). One exception was found in the Health and Women’s Education textbook (Grade 12), where a female doctor is depicted with her face erased (Health and Women’s Education textbook, Grade 12, Ministry of Education, p. 104). Issues related to revealing women’s faces in textbooks could be rooted in a cultural belief that women should cover their faces out of modesty. This fact might also contribute to explaining why there are fewer images of women in the three textbooks than men.

Budget and saving are among the topics covered in the Life Skills and Family Education textbook (Saudi Ministry of Education, p. 37) to teach youth about managing family budgets. In one example, a scenario is presented of working parents who have high monthly salaries but are still dealing with financial problems. While it is noteworthy that the textbook referred to the woman as having a highly paid job, it did not specify the type or title of the job and, as such, seemed like a missed opportunity to present a professional image of a working woman and specify a profession that might inspire the girl students reading the text.

In addition to placing women in specific societal roles and career pathways, there are several examples in which girls are presented as being spoiled and engaging in gossiping, which contribute to reinforcing negative stereotypes of women. One example that stands out is of two girls gossiping about a friend (Saudi Ministry of Education, p. 21). In the same lesson, a brother complains about his spoiled sister, whom he believes gets the most attention from his parents:

• Scenario 1: Group discussion: Hind is the only girl in the family, Amin always feels that his sister gets what she wants, that Hind is the spoiled daughter, and this is why they always fight.

• Scenario 2: Hanan said to her friend Rawia, ‘I have heard what you said about me and I will cut off my relationship with you forever.’ From what you have learned about skills of managing conflict, complete the story and suggest reconciliation (p. 20).

The two instances above portray Saudi women in specific frames as being spoiled and in dealing with petty friendship-related difficulties. The issue here is not so much with the stories themselves as it is with the fact that these textbooks continue to portray Saudi women as simply dealing with ordinary, trivial, issues rather than being engaged in serious, professional, and work-related issues.

Lastly, in Life skills and Family Education (Grade 10), a whole unit presents a group of skills an individual needs to manage family and work conflict and lead a successful family and professional life. These skills include critical thinking, decision making, problem solving, goal defining, and information processing (pp. 63–86). However, only two examples referred to females in the texts, examples, and scenarios. One of these portrays a girl, Nadia, debating whether or not to take weight control pills:

Nadia reads an advertisement for a commercial product in tablet form that helps control weight, so she hurries to call and ask how to obtain the product. Nadia takes the initiative to request to talk to the marketing department to determine the quality of the product and the methods of use in order to make a decision about whether to buy the product or not. (p. 82).

Within the context of critical thinking and initiative taking, this example reinforces a couple of potentially damaging stereotypes; first, that women care more than men about their weight and appearance; and second, that women should be thin, which could potentially contribute to body image problems. Analysis of the three textbooks discerned Stereotypes of Girls and Women as a prominent theme, which contributes to generating assumptions and expectations regarding Saudi women and their roles in society.

3.4. Theme 4. Lack of female role models

The second theme reported on the exclusion of Saudi women in images and text references across the data corpus; the third theme on abundant examples of men in different professions while simultaneously restricting women’s roles to domestic life. While each of these themes constitutes evidence of disempowerment, taken together they result in a fourth theme: a lack of Saudi female role models actively contributing to the community, society, and country. Excluding examples of female role models included presenting the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, and his companions, without including the women in their lives, and the significant female role models who actively contributed to the unfolding of history up to the present day. Overall, a lack of female role models also served to undermine the textbooks stated aim:

To provide students with important issues in life to achieve a degree of competence that enables them to deal with life issues and the means to face the fast-changing world. It aims to enhance students’ self-confidence, love for professional work, and be critical and creative thinkers to prepare her for academic and work life (Saudi Ministry of Education, 2020, textbook, p. 1, 4).

Despite the first theme of awareness, the subsequent three themes undermine the empowerment principles of the conceptual frame. Taken together, the three themes illustrate principles of women’s empowerment that are not expressed in the Family and Education curricula in light of Saudi Vision 2030.

4. Discussion

This study set out to examine, first, which principles of women’s empowerment can be discerned in the Vision 2030 documents as culturally important now and, second, which of those were expressed in three high school textbooks. Content analysis of the textbooks enabled the construction of four themes that served to answer the research questions. In terms of the first research question—How are girls and women are portrayed in the textbooks?—two subthemes of Exclusion and Stereotyping illustrate that women are either not portrayed at all, or they are portrayed in outdated stereotypes. Together, these two themes contribute to a third theme: lack of historical and contemporary female role models who exemplify the Vision 2030 principles of women’s empowerment. In terms of the second research question—What principles of empowerment are evident in the Family and Education curricula in light of Saudi Vision 2030?—only one was prominent: Awareness of the drawbacks of early marriage and new laws aiming to prevent against it. Together, these findings suggest that the high school curricula largely do not reflect the Vision 2030 principles highlighting partnership among all members of society towards Saudi Arabia’s progression.

Instead, women are vastly underrepresented in the three textbooks, in images and text examples, with more frequent use of male figures in hypothetical scenarios. This is consistent with several other studies that confirmed that school textbooks reference men more than women (Erlman, 2015; Duque, 2019). Women and girls were also underrepresented in topics related to sports, in all three textbooks, even though the Vision 2030 document states: “We intend to encourage widespread and regular participation in sports and athletic activities, working in partnership with the private sector to establish additional dedicated facilities and programs” (Thriving Economy, para. 11). The theme of Exclusion hinders the nation’s development even though the Saudi Vision stresses the importance quality of education for both male and female students and as an important factor that promotes women’s empowerment: “Saudi women are yet another great asset. With over 50 percent of our university graduates being female, we will continue to develop their talents, invest in their productive capabilities and enable them to strengthen their future and contribute to the development of our society and economy” (p. 36).

Most examples provided in the textbooks reinforced stereotypes of Saudi women as enjoying shopping, gossiping, fashion, beauty, cooking, and being spoiled. Gender inequality based on stereotypes has been shown to influence women’s career progression, self-confidence, and self-perception of their capabilities (Oliver and Lalik, 2001; Tabassum and Nayak, 2021). In addition, over-emphasis on girls’ appearances may also reinforce social acceptance of girls’ anxieties about their body image (Oliver and Lalik, 2001), rather than supporting girls in developing healthy perspectives of themselves at an important age of identity construction.

The fourth theme involves the lack of active, successful female role models in the textbooks. Previous research has asserted that young female students need other successful women as role models in different fields (Ruiz-Cecilia et al., 2021). Many studies have provided evidence of the influence of exposure to role models on female choice of career pathways and increasing enrollment in STEM programs (Thomas et al., 2020). For example, Pérez et al. (2020) found a positive impact of female role model sessions on students’ perceptions about STEM programs and motivations. Further, Gladstone and Cimpian (2020) argued that “providing an inspirational and relatable model, role models may counteract the effects of gender norms on students’ social identity” (p. 6). In fact, none of the three textbooks feature a single example of a woman’s achievement, or a Saudi woman’s success story, despite there being many successful Saudi women in leading positions, as businesswomen, entrepreneurs, scientists, and doctors, who could feature as role models. There was a whole unit on life and work skills with no reference to female in high paying jobs, STEM jobs, or leading challenging issues relate to family and work. Providing girls and young women with examples of women role models in politics, science and technology, civic life, art, and economics, for example, would emphasize young women’s roles as partners in national development. Instead, the textbooks’ focus on male role models may lead students to associate men with certain jobs and superior capabilities, reinforce gender stereotypes, and limit expectations of and amongst women.

The lack of historical and contemporary influential Saudi women in different fields points to an incoherent gap between what the government envisions of Saudi women’s roles and what the textbooks are promoting. It worth noting that Vision 2030 is a reality in practice: many educational initiatives and programs have already been launched that aim to increase both male and female student participation in international competitions in science and math. “The initiative aims to enhance the participant of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in international and regional scientific competitions for both male and female students in math, physics, and chemistry” (Education Programs and Initiatives of Vision 2030, 2021, Human Capability Development Program, p. 69). Yet, in not employing examples of girls and women in these fields, the textbooks seem to be lagging behind the vision.

Reflecting only one of the major principles of women’s empowerment in the Conceptual Frame (Awareness); excluding Saudi girls and women from images and descriptions of prestigious professional roles and economic and social development; reinforcing gender stereotypes; and missing chances to highlight female role models for Saudi girl students are the findings of this study described in four themes. Together, they reinforce existing limitations on Saudi girls and women.

4.1. Recommendations

Even though the textbooks of the Family Education curriculum were published between 2018 and 2021, which is after the launch of Vision 2030, they still lack meaningful reference to Saudi women’s role in public life and development of the country—regardless of the language of Vision 2030. This inconsistency between the country’s intended objectives of women’s empowerment and the content of the Family Education curriculum suggests the need to revise the curriculum to provide young Saudis with equal representation for broader, more inclusive futures across all fields and professional domains. Girls and women must take equal places next to boys and men in all three Family Education textbooks, which must provide real and relevant role models across professions and social activities. This is the first recommendation. There are others.

The textbooks’ intended objectives, as claimed by the official publisher, are to “enhance students’ self-confidence, creative and critical thinking, and prepare her for the university and the practical life” (Saudi Ministry of Education, p. 4). These objectives chime with the literature on school textbooks as having impact on young students’ development, self-perceptions, and confidence. Yet, the findings of this study suggest that most of the topics covered, the tasks, and the discussion topics do not help promote female students’ self-confidence and creative and critical thinking skills because women are either absent from the images and texts of those discussions or relegated to topics like cooking, design, and fashion. This could be corrected by weaving in examples of women in images and text descriptions throughout all three textbooks, and adding a section on women’s new rights, social roles, and opportunities in the new government vision.

An educational aspect of Vision 2030 describes a model curriculum to better equip students with the skills needed to be active members of society, stating.

[W]e will prepare a modern curriculum focused on rigorous standards in literacy, numeracy, skills and character development. We will track progress and publish a sophisticated range of education outcomes. We will build a centralized student database tracking students from early childhood through to K-12 and beyond into tertiary education (higher and vocational) in order to improve education planning, monitoring, evaluation, and outcome. (Thriving Economy, para. 7).

To successfully utilize the Saudi educational vision, public and private education must align its curricula to the Saudi Vision 2030 goals, and also review its appropriateness for the learner’s developmental stage. In addition, Vision 2030 recognizes the power and potential of a youthful population in leading change in Saudi Arabia:

One of our most significant assets is our lively and vibrant youth. We will guarantee their skills are developed and properly deployed. While many other countries are concerned with aging populations, more than half of the Saudi population is below the age of 25 years. We will take advantage of this demographic dividend by harnessing our youth’s energy and by expanding entrepreneurship and enterprise opportunities. (Thriving Economy, para. 4).

High school curricula are potentially powerful vehicles for developing youth skill and channeling youth energy in line with the country’s developmental goals. Simultaneously, school curricula are important tools in shaping students’ aspirations and values (Osnes et al., 2019; Tam et al., 2020; Ruiz-Cecilia et al., 2021) in line with the society’s values. Culture and religion, highlighted as “Islamic principles, Arab values, and our national traditions,” are central to Vision 2030 and to the country’s development. These values include: “supporting the vulnerable and needy, helping our neighbors, being hospitable to guests, respecting visitors, being courteous to expatriates, and being conscientious of human rights” (An Ambitious Nation, para. 15).

The three textbooks successfully stressed many positive Islamic principles related to women, such as women’s right to be educated, marriage rights, the importance of motherhood, rights to safety and protection, and modesty and humility for both genders. Cherished cultural values can and should be employed to enhance the present. But all four thematic principles of women’s empowerment of the Conceptual Frame, discerned from the Vision 2030 documents, along with Awareness— Independence, Equality, and Inclusion—must be reflected in high school curricula. Additionally, the textbooks need to expand upon Awareness to discuss other new laws and amendments, beyond those related to early marriage, such as labor and women rights, divorce, custody, and anti-harassment. Along with highlighting important cultural and social values for young people, high school curricula and educators must help young people in embodying those values and achieving the social visions. Decisions about revising the Family Education curricula should be guided by inputs from different 601 stakeholders along with the Ministry of Education, such as parents, teachers, and students themselves.

An additional recommendation related to awareness is that female students may not be aware of the Vision 2030 goals and the roles women must play in achieving those goals; hence, schools and teachers plays a key role in advancement of the Vision through their very students. Teachers, too, must be educated toward awareness of the dangers of a curriculum that reinforces stereotypes and the benefits of one that provides empowering stories of successful women in many fields and increases thinking, reflection, and discussion about changing gender roles. Discussions on topics related to society, the structure of the family, and current policies, regulations, and issues help students be more engaged in topics related to their lives and actively productive (Garrett, 2020, p. 2.).

A final recommendation is that further studies are needed on curricular revision in light of cultural change. Teachers’ and professional educators’ perspectives are needed. Classroom observation is essential to evaluate the how these topics are taught. More research is needed to examine this gap between the government vision, expressions of empowerment in high school textbooks, and diversities of lived realities amongst Saudi girls and women. The themes, implications, and recommendations of this study are summarized in Table 5.

5. Conclusion

This study has identified a gap between the Saudi government’s stated drives to empower female Saudi citizens and what are promoted in the high school textbooks It is interesting to note that even though the Saudi Ministry of Education has taken significant steps via many initiatives and programs launched after the release of Vision 2030 to develop and revise the curriculum to develop students’ cognitive, social-emotional, and personal skills, still women representations in the curriculum is weak. The primary issue is the curriculum's division into sections that discuss the roles of boys and girls and the life skills required for both. These textbooks ought to be omitted and the concentration should be on cognitive abilities including decision-making, critical thinking, and problem-solving for both sexes. Further revision of the curriculum is needed to reflect the strategic objectives of the education and the women’s empowerment principles of Vision 2030. This study’s findings contribute to expanding existing literature on the topic of female youth development and empowerment via curricula in a unique cultural instance. In addition, implications of this study might be useful to curriculum developers, school leaders, and policy makers in other contexts, including highlighting the power of high school curricula. Principles of women’s empowerment, inclusion of female role models, and illustrations of women’s active contribution in a variety of professional contexts and life domains, expressed in high school curricula, all contribute to revising existing stereotypes and presenting new, active, representations of girls and women as equal partners in a country’s development.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.moe.gov.sa/en/pages/default.aspx; https://ktby.net/575/.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

RA would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research for organizing the research summer Boot Camp at PNU to support PNU researchers. The researcher would like to thank Claire for her support and feedback writing the research.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alasgah, A. A. A., and Rizk, E. S. I. (2021). Empowering Saudi women in the tourism and management sectors according to the Kingdom’s 2030 vision. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 11, 1–102. doi: 10.1080/20430795.2021.1874217

Al-Qahtani, M. M. Z., Alkhateeb, T. T. Y., Mahmood, H., Abdalla, M. A. Z., and Qaralleh, T. J. O. T. (2020). The role of the academic and political empowerment of women in economic, social, and managerial empowerment: the case of Saudi Arabia. Economies 8:45. doi: 10.3390/economies8020045

Al-Qahtani, A. M., Elgzar, W. T., Ibrahim, H. A., and El Sayed, H. A. (2021a). Empowering Saudi women in higher educational institutions: development and validation of a novel women empowerment scale. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 25, 13–25. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i1s.2

Al-Qahtani, A. M., Elgzar, W. T., Ibrahim, H. A., El-Houfy, A., and El Sayed, H. A. (2021b). Women empowerment among academic and administrative staff in Saudi universities: a cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 25, 60–68. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i1s.6

Alkhaled, S., and Berglund, K. (2018). ‘And now I’m free’: Women’s empowerment and emancipation through entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia and Sweden. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 30, 877–890.

Aqel, A. A. (2020). Empowerment of female students at Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 31, 12–30. doi: 10.31901/24566322.2020/31.1-3.1138

Becker, L., and Nilsson, M. (2021). College chemistry textbooks fail on gender representation. J. Chem. Educ. 98, 1146–1151. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01037

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dalati, S., Raudeliuniene, J., and Davidaviciene, V. (2020). Innovations in the management of higher education: situation analysis of Syrian female students’ empowerment. Mark. Manag. Innov. 4, 245–254. doi: 10.21272/mmi.2020.4-20

Duque, E. (2019) Estudio Evolutivo de la Proyección de la Mujer en el Libro de Texto New Headway Intermediate. master’s thesis. [Granada], University of Granada.

Durrani, N. (2008). Schooling the ‘other’: the representation of gender and national identities in Pakistani curriculum texts. Compare J. Comp. 38, 595–610. doi: 10.1080/03057920802351374

Erlman, L. (2015) Heteronormativity in EFL textbooks. A review of the current state of research on gender-Bias and heterosexism in ELT Reading material. Ph.D. Thesis. Gothenburg: Göteborgs Universitet.

Garrett, H. J. (2020). Containing classroom discussion of current social and political issues. J. Curric. Stud. 52, 337–355. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2020.1727020

Gladstone, J., and Cimpian, A. (2020). Role Models Can Help Make the mathematics Classroom More Inclusive. Department of Psychology. New York, NY: OSF Preprints.

Green, A., Ferrate, S., Boaz, T., Kutash, K., and Wheeldon-Reece, B. (2021). Social and emotional learning during early adolescence: effectiveness of a classroom-based SEL program for middle school students. Psychol. Sch. 58, 1056–1069. doi: 10.1002/pits.22487

Griffith, A. L. (2010). Persistence of women and minorities in STEM field majors: is it the school that matters. Econ. Educ. Rev. 29, 911–922. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.010

Halim, M. L., and Ruble, D. (2009). “Gender identity and stereotyping in early and middle childhood” in Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology Vol: Gender research in general and experimental psychology. Springer Science +Business Media. (New York, NY: Springer). 495–525.

Hussain, S., and Jullandhry, S. (2020). Are urban women empowered in Pakistan? A study from a metropolitan city. Womens Stud Int Forum 82:102390. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102390

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2020) Women Business and Law. The World Bank Group, Washington, DC, 20433.

Kahveci, A. (2010). Quantitative analysis of science and chemistry textbooks for indicators of reform: a complementary perspective. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 32, 1495–1519. doi: 10.1080/09500690903127649

Kohlberg, L. (1966). “A cognitive-developmental analysis of children’s sex-role concepts and attitudes” in The Development of Sex Differences. ed. E. E. Maccoby (California: Stanford University Press)

Ledman, K., Rosvall, P., and Nylund, M. (2018). Gendered distribution ‘knowledge required for empowerment’ in Swedish vocational education curricula. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 70, 85–106. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2017.1394358

Miles, J. (2020). Curriculum reform in a culture of redress: how social and political pressures are shaping social studies curriculum in Canada. J. Curric. Stud. 53, 47–64. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2020.1822920

Margolis, E., and Zunjarwad, R. (2018). Visual research. in The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research. (eds.) N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln’s (California, CA: SAGE Publications), 600–626.

Najmabadi, K. M., and Sharifi, F. (2019). Sexual education and women empowerment in health: a review of the literature. Int. J. Women's Health Reprod. Sci. 7, 150–155. doi: 10.15296/ijwhr.2019.25

Nieva, F. (2015). Towards the empowerment of women: a social entrepreneurship approach in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Innov. Reg Dev. 7, 161–183.

Okonofua, F., and Omonkhua, A. (2021). Women empowerment: a new agenda for socio-economic development in Saudi Arabia. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 25, 9–12. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i1s.1

Oliver, K., and Lalik, R. (2001). The body as curriculum: learning with adolescent girl. J. Curric. Stud. 33, 303–333. doi: 10.1080/00220270010006046

Omair, M., Alharbi, A., Alshangiti, A., Tashkandy, Y., Alzaid, S., Almahmud, R., et al. (2019). The Saudi Women Participation in Development Index. J King Saud Univ Sci 32. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2019.10.007

Osnes, B., Hackett, C., Lewon, J. W., Baján, N., and Brennan, C. (2019). Vocal empowerment curriculum for young Maya Guatemalan women. Theatre Dance Perform. Train. 10, 313–331. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2019.1637371

Ravitch, S. M., and Riggan, M. (2017). Reasons and rigers : How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research. Sage Publications.

Ruiz-Cecilia, R., Guijarro-Ojeda, J. R., and Marin-Macias, C. (2021). Analysis of heteronormativity and gender roles in EFL textbooks. Sustainability 13:220. doi: 10.3390/su13010220

Salm, M., Mukhlid, K., and Tokhi, H. (2020). Inclusive education in a fragile context: redesigning the agricultural high school curriculum in Afghanistan with gender in mind. Gend. Educ. 32, 577–593. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2018.1496230

Saudi Ministry of Education. (2017). Saudi Arabia vision 2030, an ambitious vision for an ambitions nation. Saudi Arabia vision 2030. Available at: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa. (Accessed May 6, 2021).

Saudi Ministry of Education (2018) Family and Health Education-first Level. General Education, Quarterly System for High School Education, Girls Textbook. Ministry of Education, Riyadh.

Saudi Ministry of Education. (2020). Life skills and family education, high school education (courses system). Ministry of Education, Riyadh.

Saudi Ministry of Education. (2021). Health and Female Education, High School Education (courses system). Ministry of Education, Riyadh.

Serra, P., Rey-Cao, A., Camacho-Minano, M. J., and Soler-Prat, S. (2021). The gendered social representation of physical education and sport science higher education in Spain. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 26, 1–110. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2021.1879768

Shioyama, S. (2020). “Work experience education” in secondary schools in India: a women’s empowerment perspective. Evol. inst. econ. rev. 17, 503–519. doi: 10.1007/s40844-020-00175-0

Smith, A. D. (1991). National Identity (Ethnonationalism Comparative Perspective). Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press.

Tam, H., Chan, A. Y., and Lai, O. L. (2020). Gender stereotyping and STEM education: Girls’ empowerment through effective ICT training in Hong Kong. Childr. Youth Serv. Rev. 119:105624

Tabassum, N., and Nayak, B. (2021). Gender stereotypes and their impact on Women’s career progressions from a managerial perspective. IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag. Rev. 10, 192–208. doi: 10.1177/2277975220975513

Thomas, B., Julien, G., Marion, M., and Effenterre, C. V. (2020). Do female role models reduce the gender gap in science? Evidence from French high schools. IZA–Institute of Labor Economics: discussion paper serious. IZA DP No. 13163, 1–40.

Topal, A. (2019). Economic reforms and women’s empowerment in Saudi Arabia. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 76. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102253

Ullah, H., and Skelton, C. (2013). Gender representation in the public sector schools textbooks of Pakistan. Educ. Stud. 39, 183–194.

Vision Realization Office. (2021). Education programs and initiatives of vision 2030. Saudi Ministry of Education. Available at: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps. (Accessed May 6, 2021).

Keywords: curriculum design, women’s empowerment, adolescent development, gender identity, Saudi Vision 2030

Citation: Aldegether RA (2023) Representations of girls and women in a Saudi Arabian family education curriculum: a content analysis. Front. Educ. 8:1112591. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1112591

Edited by:

Dolana Mogadime, Brock University, CanadaReviewed by:

Clare Woolhouse, Edge Hill University, United KingdomVilma Zydziunaite, Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania

Copyright © 2023 Aldegether. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Reem A. Aldegether, cmFhbGRnZXRockBwbnUuZWR1LnNh

Reem A. Aldegether

Reem A. Aldegether