94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 24 July 2023

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1112577

This article is part of the Research Topic The Changed Life: How COVID-19 Affected People's Psychological Well-Being, Feelings, Thoughts, Behavior, Relations, Language and Communication View all 43 articles

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated rapid adjustments by teachers to ensure effective education. This shift in circumstances has created a more challenging working environment for teachers, leading to growing concerns about their occupational well-being both nationally and globally. While adapting to change and sustaining professional well-being are crucial for teachers, it is equally important to address their well-being during the pandemic. This study aims to contribute to the existing literature by employing questionnaires and semi-structured interviews to explore the occupational well-being of in-service teachers in Hanoi, Vietnam. Additionally, it seeks to examine their perceptions of school leaders’ efforts to enhance teachers’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Convenience sampling was utilized to collect questionnaire data from 103 in-service teachers and lecturers in Hanoi, Vietnam, between 2021 and 2022. Moreover, a purposive sampling approach was employed to select eight participants for semi-structured interviews. The questionnaires and interviews formed the primary methods of data collection for this study.

Results: The findings of this study indicate that, overall, the participants exhibited a moderate level of occupational well-being. It was also observed that the participants received support from school leaders in terms of professional development, flexibility, and well-being activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. These results provide valuable insights for teachers to understand their personal occupational well-being and contribute to institutional awareness.

Discussion: The outcomes of this study have significant implications for teachers and principals. They shed light on the promotion of teachers’ occupational well-being during this critical period. Furthermore, the study illustrates how education stakeholders can play a role in enhancing teachers’ well-being. The discussion delves into the importance of personal occupational well-being and institutional awareness, emphasizing the need for collaboration among various stakeholders to create a conducive environment for teachers.

The global Coronravirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has profoundly influenced individuals’ mental health and well-being (Holmes et al., 2020). Since March 2020, teachers have been confronted with increasing standards and fewer resources, so they are not immune to these effects (Kim and Asbury, 2020). Due to the current health crisis, schools, universities, institutes, and colleges around the globe have been forced to implement emergency remote teaching, which refers to a temporary adjustment in instructional delivery as a replacement for face-to-face schooling (Daniel, 2020; Fuchs, 2022). In an effort to prevent the development of COVID-19 in Vietnam, the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) issued a directive for schools to use remote learning via television or the Internet to ensure the continuation of students’ education (Nguyen, 2020). Previously predicated on traditional face-to-face education, the unanticipated restructuring of the school system resulted in significant shifts in learning and teaching practices (Trung et al., 2020). In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, instructors must adjust fast to continue and assure the quality of education delivery, and their work environment appears to be increasingly demanding. Understanding the occupational well-being of teachers is crucial, given that insufficient well-being might have severe consequences for the profession. It can, for instance, result in educators leaving the profession (Kim and Asbury, 2020), increase the financial load on the educational system (Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond, 2017), and have uncertain effects on the learning outcomes of children (Zhou and Yao, 2020). Developing conditions for recognizing and promoting teacher well-being, especially occupational well-being during the pandemic, should therefore be a major priority.

While research on mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic has largely focused on students, there has been a lack of recognition and acknowledgment of teachers’ well-being, experiences, and needs in relation to their work (Lee, 2020). Although there have been studies on teacher, few have specifically examined teachers’ mental health and welfare during unprecedented events like the COVID-19 pandemic. Ideally, supporting teacher well-being would involve ensuring adequate salaries and benefits, manageable workloads, professional development opportunities, and support from employers and the government (Wu and Lu, 2022). However, the current situation in Vietnam falls short of this ideal, with many teachers facing challenges such as low salaries, heavy workloads, and limited support, leading to high-stress levels and burnout (Hoang et al., 2020). These challenges have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given the need for further research on teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study aims to investigate the levels of occupational well-being among in-service teachers in Hanoi. Understanding these perspectives can provide valuable insights for school leaders and policymakers seeking to improve teachers’ well-being.

In this sense, this paper aims to answer two specific research questions:

• What are the occupational well-being levels of Hanoi’s in-service teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic?

• What do teachers in Hanoi believe school administrators could do to improve teachers’ occupational satisfaction?

By examining these questions, this study aims to contribute to the existing literature by providing insights into the unique experiences of teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic and identifying strategies that can support their well-being.

Occupational well-being refers to the meaning and satisfaction that individuals obtain from their jobs (Doble and Santha, 2008). Similarly, Collie and collaborators defined job-related well-being as “individuals’ positive evaluations and healthy functioning in the workplace” (Collie et al., 2015). The theoretical and practical significance of teachers’ occupational well-being cannot be overstated. It is related to teacher burnout, psychological health, physical fitness, and student motivation and achievement (Bauer et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2015; Klusmann et al., 2016). Diener et al. (1999) identify the presence of positive aspects, such as job satisfaction and work passion, and the absence of negative experiences, such as stress and emotional distress, as indicators of teachers’ occupational well-being, which refers to their optimal psychological performance and experience at work (Ryan and Deci, 2000). This study utilizes the definition of teachers’ occupational well-being as “teachers’ responses to the cognitive, emotional, health, and social situations associated with their work and profession” (Viac and Fraser, 2020). This adoption is based on the fact that Viac and Fraser (2020) take into account the established major components of teachers’ occupational well-being. In particular, their emphasis on the occupational aspect of teacher well-being shows the relationships between teacher well-being, teachers’ practice, and the impact on the education system and students.

COVID-19, a coronavirus, was officially declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 12, 2020. The global pandemic of COVID-19 and the consequent societal limitations enforced by governments around the world have had extensive social and psychological repercussions (Passos et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on school systems worldwide and numerous schools in Vietnam are transitioning from conventional face-to-face teaching to distance education (MOET, 2020; Trinh, 2021).

The quick shift to remote teaching during the COVID-19 outbreak may have altered the demands instructors faced at work (Pöysä et al., 2021). This is important to note from the perspective of teachers’ occupational well-being. Several studies on the well-being of teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a variety of stressors and work-related requirements during school closures. UNESCO, for instance, asserts that uncertainty and stress are among the harmful effects of school closures on teachers (UNESCO, 2021). This position is supported by MacIntyre et al. (2020) conclusion that teachers reported high-stress levels during school closures. According to Li et al. (2020), the incidence of anxiety among instructors during the COVID-19 pandemic is nearly three times greater than previously observed. In addition, Collie (2021) indicated that during school closures, autonomy-restrictive leadership is associated with increased emotional exhaustion in teachers, whereas autonomy-supportive leadership increases workplace buoyancy, thereby reducing teachers’ somatic burden, stress, and emotional exhaustion. In addition, social isolation and a lack of frequent social support may have negatively affected teachers’ mental health and well-being. According to Dabrowski (2020), the sudden absence of interaction generated by COVID-19 substantially affects teachers’ emotions. When teachers cannot meet their students in person, they may experience a sense of loss, culminating in grief in teachers who were underappreciated or unsupported. Teachers who work from home have extra responsibilities and must balance work and family life. The fact that teachers are “on-call” 24 h a day, 7 days a week, has a negative effect on their well-being (Dabrowski et al., 2020).

Several research papers propose analytical frameworks for evaluating the well-being of teachers. Van Horn et al. (2004) established five analytical aspects of the occupational happiness of teachers: (1) emotional well-being; (2) social well-being; (3) professional well-being; (4) cognitive well-being; and (5) psychosomatic well-being. Collie et al. (2015) suggested examining teachers’ work-related well-being across three dimensions: “(1) workload well-being, (2) organizational well-being, and (3) student interaction well-being.” In this approach, workload well-being refers to problems associated with workload and concomitant stress. Organizational well-being is correlated with teachers’ impressions of the school as an organization, including judgments of school leadership and the culture toward teachers and teaching. Student interaction wellbeing is correlated with teachers’ interactions with students (Collie et al., 2015). Despite the fact that both the Collie et al. (2015); Van Horn et al. (2004) ‘models highlight multiple dimensions, it is essential to remember that they are interdependent (Viac and Fraser, 2020).

A recent Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)'s working paper examined the research on teacher well-being, proposed a conceptual framework, and suggested instruments to be included in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA, 2021) teacher questionnaire to assess teachers’ occupational well-being (Viac and Fraser, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, this study uses and modifies the original and holistic framework to measure the occupational well-being of in-service teachers in Hanoi. Viac and Fraser (2020)’s framework focuses specifically on the topic of this study, which is teachers’ occupational well-being, as opposed to investigating teachers’ well-being in general.

According to Viac and Fraser (2020)’s approach, teachers’ occupational well-being is defined by four primary dimensions: cognitive, subjective, physical and mental, and social. Each of these dimensions has several indicators that facilitate their measurement. Self-efficacy (from cognitive well-being), work satisfaction (from subjective well-being), psychosomatic symptoms (from physical and mental well-being), and social relationships (from social well-being) were each represented by a single indicator in this study (from social well-being). Consequently, this framework allows us to address the research questions: “What are the occupational well-being levels of Hanoi’s in-service teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “What do teachers in Hanoi believe school administrators could do to improve teachers’ occupational satisfaction?” This comprehensive approach provides a robust foundation for examining teacher well-being and identifying strategies that school administrators can employ to enhance job satisfaction among teachers in the current challenging circumstances. Specifically, this research was a case study done to investigate teachers’ professional well-being amid periods of upheaval and disruption brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, despite time and space constraints. Given this, reducing the original, expansive framework is appropriate by assessing the most relevant and noticeable indication for each component of teachers’ occupational wellbeing.

Interest in teacher well-being is neither novel nor unexpected; it has been investigated across all educational age groups and is pursued globally. Cook et al. (2017) recognized an abundance of data indicating that teaching is a challenging profession and that teacher stress and burnout can hinder teacher effectiveness in the United States. They concluded that participants in the ACHIEVER Resilience Curriculum for boosting teacher well-being had superior outcomes, such as increased teaching effectiveness and decreased job-related stress and anxiety. Their findings suggest that interference in teacher preparation and continuous professional development should focus on teacher well-being. Moreover, Bricheno et al. (2009) conducted a literature analysis on intervention methods for teachers’ well-being in the United Kingdom, focusing primarily on mental health and stress. Zhu et al. (2011) investigated school cultural characteristics, teacher institutional dedication, and well-being as outcomes of school culture in China, whereas Yin et al. (2016) examined the emotional nature of teachers’ professions and the extent to which it is detrimental to teachers’ well-being. Mattern and Bauer (2014) discovered that the cognitive self-regulation of secondary mathematics teachers improved their occupational well-being or level of emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction, which directly impacted the quality of their work, job satisfaction, and overall well-being.

Since the COVID-19 began, educators have faced a variety of challenges, but their professional well-being has not gotten much consideration (Chan et al., 2021). In a report, school leaders from 17 school districts in California expressed grave concerns regarding teacher mental health and workload, as well as a growing teacher shortage in the COVID-19 context (Carver-Thomas et al., 2021). Similarly, research from other nations demonstrated that teachers’ mental health declined during the outbreak (Ali and Razali, 2019; Allen et al., 2020). In the United Kingdom, for instance, longitudinal research revealed an increase in teachers’ anxiety after school closures (Allen et al., 2020). Another study, including 1,633 Spanish teachers, found that almost one-fourth of respondents had “severe” to “extremely severe” stress and anxiety (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021). According to information received from Zhou and Yao (2020), 9.1% of teachers in China had stress symptoms in March 2020. In Vietnam, Nguyen and Le (2021) investigated the effects of COVID-19 on the psychological well-being of Vietnamese adults in their study. Research on the effects of COVID-19 on the education sector is beginning to emerge. For instance, Vu and Bosmans (2021) demonstrated that COVID-19 anxiety is highly and specifically associated with learning-related cynicism but not learning fatigue, indicating that the pandemic affects Vietnamese students’ capacity to develop via education. Similarly, Kim et al. (2022) found that teachers’ mental health and well-being declined throughout the COVID-19 by applying the Viac and Fraser (2020) model. In the literature, however, extensive data on teacher occupational well-being in the context of COVID-19 are mostly ignored. It means that considerable efforts to investigate the occupational health of Vietnamese educators during this vital and difficult period of health issues need to be implemented. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature by identifying the occupational well-being levels of Vietnamese teachers and what school leaders may do to assist them survive in the digital age pedagogy due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study employed a mixed-method design in order to achieve an objective and comprehensive perspective. The combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches is critical because it answers this study’s research questions. In particular, this study followed the explanatory sequential design (Creswell and Clark, 2017), starting with quantitative data collection and analysis and following up with the qualitative data, leading to interpretation.

Among 170 surveys distributed, 142 surveys were collected (83.5% response rate). After eliminating the incomplete surveys, the final number of included surveys was 103.

There are 103 final participants involved in the survey part, and 8 were chosen for further interviews. All the participants are Vietnamese and currently living and working in Hanoi, Vietnam. The demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Eight teachers (3 lower secondary school teachers, 3 upper secondary school teachers, and 2 university lecturers) who had previously completed the questionnaire voluntarily agreed to participate in the interview (more information about the interviewee is provided in Table 2).

Participants were requested to complete an online survey after consent to the research objective and data confidentiality procedure with three critical categories of questions: (1) individual demographics questions, including gender, age, number of years teaching, highest teaching qualification, and grade level; (2) twenty questions on a 5-point Likert scale about the state of occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic; and (3) ten open-ended questions about the factors affecting the level of occupational well-being and the teachers’ opinions on the measures taken by school leaders to enhance the well-being. Twenty questions on a 5-point Likert scale were divided into four sections (see Appendix 1 in Supplementary material). In the first half, five questions assessed various aspects of teachers’ self-efficacy; in the second section, five questions assessed teachers’ job satisfaction. The third segment contained five questions regarding teachers’ psychosomatic symptoms, while the fourth section contained five questions regarding teachers’ social relationships.

After the closed-ended questions, five open-ended questions were posed to the teachers (see Appendix 1 in Supplementary material). The purpose of the first six qualitative questions was to acquire a more profound knowledge of the factors influencing teachers’ occupational well-being. These elements include burdens and empowering experiences considered beneficial or detrimental to their professional well-being (Viac and Fraser, 2020). The remaining four questions were designed to answer study question 2, which examines the steps done by school leaders that teachers subjectively perceived as beneficial to their occupational well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak.

The second research question (i.e., what do teachers believe their school leaders could do to improve teachers’ occupational well-being?) requires qualitative data because occupational well-being is such a complex and individual topic. After the survey, further interviews were conducted. In this study, individuals were selected through the use of convenience sampling during survey collecting. Convenience sampling is a type of non-probability or non-random sampling in which members of the target population meet specific practical requirements, such as easy accessibility, geographical proximity, availability at a specific time, or willingness to participate in the research (Dörnyei, 2007). The participants who finished the survey and were willing to participate in the study, and were easily accessible, were chosen for the further semi–structured interview. In addition, due to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are specific time and communication constraints during the study process; thus, convenience sampling proved to be the most suitable method for collecting sufficient data in this study.

Through open questions in the semi-structured interview session, richer data will be gathered, as this interview instrument is ideally suited for exploring participants’ thoughts and opinions on complex and frequently sensitive matters, as well as examining additional information and clarifying questionnaire responses (Louise Barriball and While, 1994). The semi-structured interview questions were included in the interview protocol (see Appendix 2 in Supplementary material).

In this study, the researchers focused on the participants who are currently working as teachers in some high schools and universities in the Hanoi area. The authors began the data collection by distributing an online survey to high school teachers in Hanoi, Vietnam, from December 2021 to March 2022. Participants currently working as teachers in some Hanoi high schools and universities and who are willing to participate in this study are chosen. Participants who did not consent to the study were skipped.

The study was approved and followed the rules and requirements of the ethics board of the University of Language and International Studies, Vietnam National University. The participants accepted to participate by signing the consent form after the researcher introduced the study and confirmed the participants’ anonymity and confidentiality. Participants were introduced to data protection and confidentiality again before the interview. Some were conducted face-to-face at the participants’ chosen places, and others were conducted online as they lived far from the researcher’s location. All interviews were conducted in Vietnamese so participants could freely express their thoughts and experiences.

Regarding the survey, the data were acquired using a modified OECD-developed quantitative questionnaire (Viac and Fraser, 2020) and analyzed by SPSS 26 software (see Appendix 1 in Supplementary material). For the interview, the data were transcribed and analyzed by using the NVivo software. The thematic analysis was applied in this paper when we analyzed the transcript, looked for patterns in the meaning of the data, and put the data in suitable themes.

This section begins with a discussion of teachers’ cognitive health as reflected by their teaching self-efficacy. Table 3 displays the proportion of in-service teachers who responded to questions on their self-efficacy with varying degrees of agreement and disagreement. As seen in the table, the majority of participants expressed confidence in their teaching abilities in the online environment. Among the required items, item SE2 received the highest proportion of “agree” and “strongly agree” responses, with 89.5% of instructors agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement. In both SE1 and SE3 items, 82.5% of respondents selected “agree” or “strongly agree” as their response. The percentage of “agree” and “strongly agree” responses for item SE5 was 69.9%, which was 5.9% lower than for item SE4 and the lowest of the 5 items. Regarding disagreements, it appears that just a tiny percentage of respondents disagreed with the mentioned statements. Particularly, 8.7% of teachers disagreed with the statement that they can encourage pupils to participate in online learning. The percentages of instructors who disapproved of items SE4 and SE5 were 7.8 and 5.8 percent, respectively. On question SE1, 9.7% of participants selected “disagree” and “strongly disagree,” while 2.9% of teachers selected “disagree” and “strongly disagree” for item SE2. In addition, 21.4% of teachers were unsure of their capacity to motivate pupils to participate in online learning.

According to the aforementioned statistics, teachers demonstrated their proficiency in online classroom management by successfully enforcing classroom regulations. A moderate proportion of participants, however, lacked confidence in their ability to engage students in online learning, which may have been considerably impacted by the quality of the technical infrastructure throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, teachers’ responses indicate a high level of readiness, preparedness, and efficacy for technology-based pedagogy in remote learning; however, there are still barriers to incorporating digital materials and technological tools into classroom practices, which requires substantial effort from teachers and support from school leaders.

According to Table 4, the self-efficacy of in-service instructors during the COVID-19 pandemic is quite high (M = 3.83; SD = 0.47). Teachers’ self-efficacy did not differ significantly among groups. However, teachers with 1 to 3 years had significantly lower self-efficacy (mean = 3.67, SD = 0.54) than teachers with 4 to 8 years of teaching experience (mean = 3.94, SD = 0.36), 9 to 18 years of teaching experience (mean = 3.80, SD = 0.50), and more than 18 years of teaching experience (mean = 3.94, SD = 0.40). The self-efficacy of instructors with a Bachelor’s degree (mean = 3.79, SD = 0.5) was not similar to that of teachers with a Master’s degree (mean = 3.87, SD = 0.48) and a Ph.D. (mean = 3.89, SD = 0.35) in terms of teaching qualification.

Table 5 displays a variety of teachers’ perspectives on their job satisfaction. Overall, teachers reported high levels of job satisfaction, with 74.8% agreeing or strongly agreeing that online education had not diminished their interest in their work. In addition, 64.1% of participants said they were supplied with more resources to promote their professional development during the COVID-19 pandemic than prior to its occurrence. The percentages of teachers who agreed with JS2 and JS3 items were 58.2 and 56.6%, respectively. In contrast, 33% of instructors disagreed with the statement, “Amid COVID-19, I do not believe that the quality of my teaching job is lower than it was before COVID-19.” This indicates a significant lack of work satisfaction among teachers. Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the rates of teachers’ uncertainty and uncertainty regarding their autonomy and job satisfaction were relatively high, at 30.1 and 34%, respectively.

The change from face-to-face teaching to distant learning may have altered the working habits of instructors, hence influencing their opinions of their job satisfaction. Moreover, it is claimed that the challenges of increased workload and the need to grasp technology solutions for online education reduce instructors’ job happiness. On the other side, teachers’ prospects for autonomy and career advancement may enhance their job satisfaction.

The mean value of teachers’ job satisfaction was 3.52, indicating a high job satisfaction level among in-service teachers in Hanoi during the pandemic. There was no notorious difference in teachers’ job satisfaction depending on their age; however, female teachers were more satisfied with their job (M = 3.53, SD = 0.52) than male teachers (M = 3.44, SD = 0.80). As shown in Table 6, teachers having 4 to 8 years of teaching experience had a lower level of job satisfaction (mean = 3.39, SD = 0.54) than the other teachers. In addition, a considerable difference can be witnessed between the grade level of teachers. Teachers working at lower secondary schools had a much lower job satisfaction (mean = 3.43, SD = 0.56) than teachers working at teachers working at upper secondary schools (mean = 3.53, SD = 0.51) and those working at universities (mean = 3.57, SD = 0.59). Regarding teachers’ teaching qualifications, the average job satisfaction level of teachers holding a Master’s degree was 3.70, SD = 0.43, which was much higher than that of teachers with a Bachelor’s degree (mean = 3.43, SD = 0.58) and a Ph.D. (mean = 3.49, SD = 0.69).

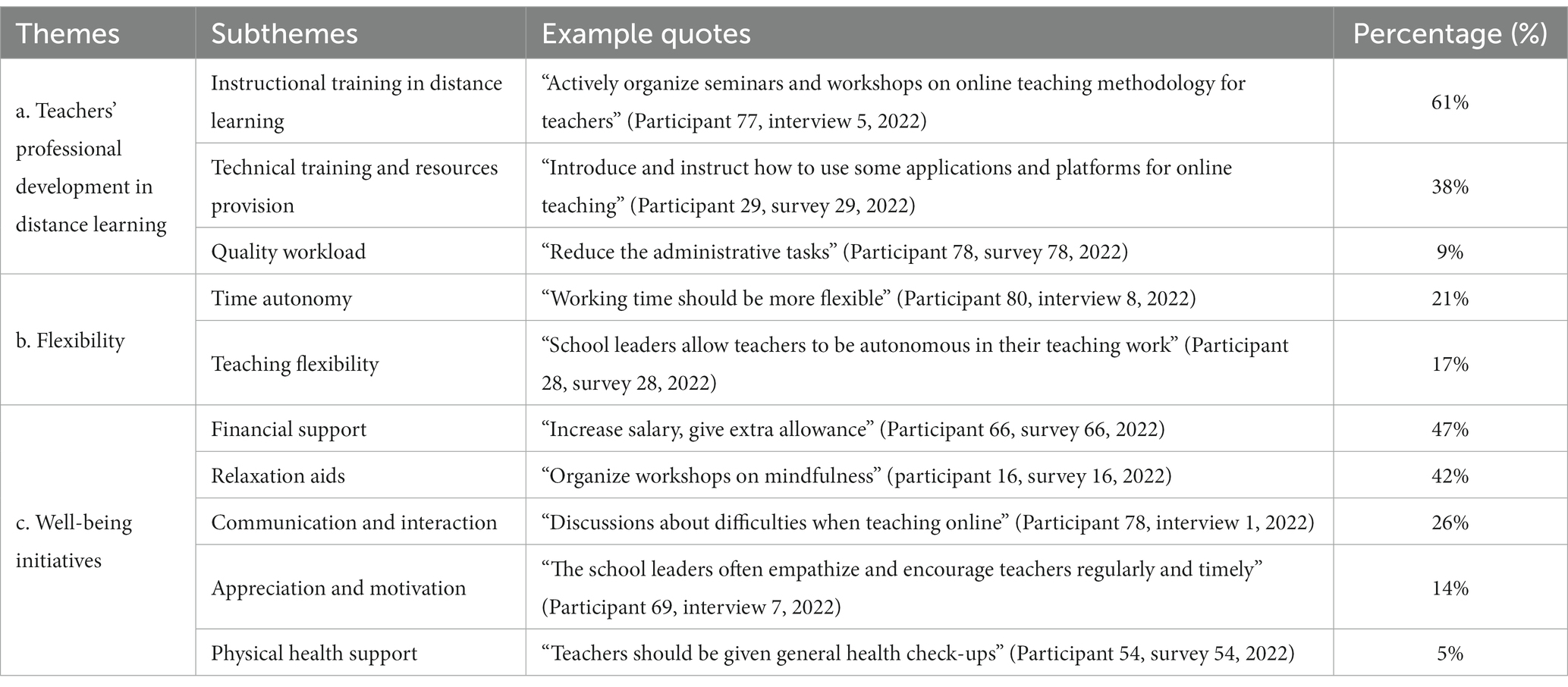

The qualitative data from the interview transcriptions and the open-ended questions in the questionnaire helped answer research question 2: “What do in-service teachers in Hanoi believe school leaders could do to improve their occupational well-being?.” The qualitative findings are summarized in Table 7. Through thematic analysis, three broad themes were detected: (1) teachers’ professional development in distance learning, (2) flexibility, and (3) well-being initiatives. The three themes are presented and discussed in further depth in the subsections below. Transcripted and anonymized excerpts from the data are presented where appropriate to highlight major themes.

Table 7. School strategies to support teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic reported by teachers.

It is critical to offer teachers educational opportunities to enhance their credentials in their teaching profession since earlier studies indicated that meaningful professional development is related to teacher morale and job satisfaction. It follows that when school leaders enable professional development that satisfies teachers’ needs for occupational progress, their occupational well-being improves. In this study, growth and the opportunities to thrive in the teaching profession encompassing instructional training in distance learning, technical training, and resource provision, and quality workload were frequently mentioned by the teachers as something leaders could positively influence teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The most frequently reported measure to support teachers’ occupational well-being was instructional training in distance learning. Findings from the open-ended questions in the survey indicate that 61% of the in-service teachers in Hanoi highlighted instructional training in distance learning as a necessary measure by school leaders. For example, Participant 43 mentioned in the survey that she believed her school should “organize a series of professional training sessions on online teaching methods to improve teachers’ competence and skills.” Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers were obliged to implement new pedagogical approaches and practices to support students’ distance learning. Therefore, they were in great need of training opportunities to enhance their pedagogical knowledge and teaching skills in the online teaching environment. In addition, there was a need to diversify how the instructional training was delivered as Hiep Nguyen put it “School leaders should build a reference framework for online teaching competencies for teachers to refer to and provide more resources of online teaching skills that teachers can self-study because sometimes the presenters in the seminars or workshops on online teaching methods delivered the content quite quickly or teachers are too busy to participate.” This excerpt not only suggests the pitfalls of organizing seminars or workshops on online teaching methods but also underscores the importance of varying the possible kinds of school leaders’ support regarding instructional training in distance learning amidst the pandemic. This inevitably entails school leaders’ concerted efforts to sensibly cater to teachers’ conceivable needs.

The provision of technical training and resources provided by 38% of the participants was another subtheme under the teachers’ professional development in distance learning. This highlights the significance of teachers’ digital competences and the training provision to aid teachers in developing their technological knowledge and technology-assisted teaching practices in the online teaching environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Huyen My expressed in the survey that her school needed to “organize training sessions on the use of information technology in teaching, testing, and assessment.” In the interview, Van Nam exemplified the specific kind of information technology provision that school leaders could offer: “online training on survey and assessment tools such as Cognito forms and Microsoft forms.” As can be inferred from these narratives, teachers are concerned about how to incorporate digital technologies effectively into their teaching and teaching-related workload. This is directly related to their aspirations for the establishment of professional learning to enhance their digital literacy and competence, which play a pivotal role in fostering their professional development during digital education.

Moreover, participants also emphasized the digital and technology-related resources that could facilitate their teaching work by mentioning that school leaders should make resource provisions for teachers. For example, in the survey, Participant 51 recommended that leaders should “equip teachers with free and unlimited Zoom accounts,” while Participant 41 stressed that her well-being would be enhanced if her school could “provide teachers with accessible digital learning platforms and resources in which teachers could further collaborate on to ease their workload.” The teachers’ responses regarding resources provision were comprehensible since, during remote learning, teachers needed to make use of digital teaching materials, video-conferencing platforms such as Zoom, and some forms of learning management systems such as Microsoft Teams to engage students in online lessons. Besides, collaborative working in the digital environment could be seen as an advantageous job resource with which school leaders could accommodate teachers. Thanks to this kind of job resource support, teachers could collectively flourish in their work and sustain coordinated performance among teachers themselves, which could possibly alleviate the stress caused by additional workload due to the shift to remote learning.

A quality workload subtheme manifested itself from the mention of 9% of the participants, underscoring the necessity to streamline teachers’ workload during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tue Chi indicated that her well-being would be improved when her school tried to “lessen administrative tasks,” which was further elaborated on by Van Nhan, who emphasized that:

“Administrative formalities still need to be streamlined continuously. If everyday teachers receive dozens of repetitive emails, messages, and notifications via multiple groups in Zalo, it clearly denotes ineffective administrative tasks because I think that effective work means with fewer texts and announcements, the work is still operating well.”

As can be inferred from the excerpts above, revised administrative procedures can aid in keeping teachers’ workload manageable, and then teachers could focus more on improving and ensuring their quality teaching, which in turn positively contributes to their occupational well-being. The excerpts also indicate that the heavy workload, especially the administrative tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic, is an impediment to improving teachers’ occupational well-being.

A number of teachers in this study reported that the flexible working environment that promotes time autonomy and teaching flexibility was a component that elevates their occupational well-being. Firstly, 21% of the participants were concerned about school leaders’ support for time autonomy in distance learning. Participant 37 expressed in the survey that “the school administrators were a bit rigid in applying the same time frame of face-to-face learning to the online one. They could possibly let teachers adjust or rearrange the teaching schedule if the interruption to distance education arose by external factors due to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Additionally, Khanh Linh mentioned that “as a lot of workloads arose during remote learning, the school meeting schedule mostly took place in the evening, encroaching on teachers’ personal rest time. So cutting down on the meeting schedules that were out of office hours would significantly do teachers a favor.” Participant 21 further shed light on this matter by explaining in the interview:

“If teachers lack personal time to rest, to calm down (due to school work), the work is ineffective. If teachers want to have the initiative to change teaching methods and write research papers, they must have time to calm down and be mindful. If teachers are not of sound mind, their bodies will be weak, and everything will not be okay (that is not counting the unnamed things teachers have to deal with at home when their children study online at home). In organizing activities outside office hours, school leaders should not only create the maximum conditions for teachers to determine whether to participate or not but also consider minimizing the required activities that may cause teachers’ psychological inhibition.”

Some insightful implications arise from these above teachers’ narratives. Firstly, the teachers’ working conditions during the pandemic should be modified in terms of the teaching timetable. The teaching schedule in a face-to-face classroom environment might not be perfectly applied to the distance learning environment, which could be affected by a variety of contextual factors such as the technology tools and infrastructure of students and teachers or the unanticipated situations when teachers are infected with COVID-19. These influential factors may cause changes to teachers’ teaching schedules, prompting them to take some control in flexibly customizing their teaching timeline to ensure teaching continuity. Secondly, school leaders should attend to teachers’ autonomy during their outside office hours as it appears to be of significant importance to teachers’ occupational well-being. Working from home has increased duties for teachers, who must manage their work and personal life in a balanced manner.

In addition, teaching flexibility was mentioned by 17% of the participants as another sub-theme that could positively influence teachers’ occupational well-being. Specifically, Minh Hang reported in the survey that she was satisfied when her school provided teachers with “more flexibility in the methods of teaching.” In the narrative of Tue Chi, she also shared positive feelings about the teaching autonomy she received in her school, which “there was not much close inspection in my school, which makes me feel more comfortable and autonomous in my teaching.” The above school leaders’ support reported by the participants, namely a higher degree of teaching methods flexibility and less strict supervision, indicate school leaders’ trust in teachers’ teaching capability and empathy for teachers in times of crisis since they had to deal with new challenges and unanticipated changes in their work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The above extracts show that during the COVID-19 pandemic, time restraints, out-of-hours work, and heavy workload may deprive teachers of adequate time to relax and to look after their well-being, causing anxiety, burnout, and occupational stress, which consequently deteriorate teachers’ occupational well-being. Conversely, it was found that having choices or control over work arrangements, work patterns, and working time and getting opportunities to exercise autonomy positively strengthen teachers’ occupational well-being. Apparently, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers indicated that they had to deal with inconvenient changes in their work, and they wanted different autonomy and flexibility over different aspects of their role. Thus, it is recommended that school leaders should get to know and understand teachers’ difficulties and needs and determine the specific kinds of autonomy support (i.e., time autonomy and/ or teaching autonomy) that would be most beneficial to teachers’ occupational well-being.

Teachers also stated some well-being initiatives that could boost their occupational well-being. Under the theme of well-being initiatives, there were six sub-themes, including financial support, relaxation aids, communication and interaction, appreciation and motivation, and physical health support.

A commonly voiced opinion among teachers was school leaders’ financial support. According to the participants’ responses, 47% of the teachers stressed the need to be given financial support when teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Khanh Linh, for example, stated in the survey that “there should be extra financial support for teachers if working overtime, provide salary increase and financial aids for research projects to increase teachers’ motivation.” Participant 47 also said that “the guarantee of monthly salary and additional income for teachers is a great practice that helps teachers feel secure in their work.” This reveals that many teachers were discontented with their salaries and welfare benefits. Guaranteeing teachers’ job quality, passion, and motivation will be difficult if the school leaders do not make efforts to improve teachers’ salaries radically. As a result, pay is a problem that demands immediate school leaders’ attention if teachers’ occupational well-being is to be enhanced.

The second sub-theme that emerged was the provision of relaxation aids, which was mentioned by 42% of the participants. Particularly, Participant 13 emphasized that school leaders can “organize many seminars and workshops on improving the mental health of teachers” while “mindfulness or meditation classes” and “online music concerts” were mentioned in an interview with Participant 80, who explained that these relaxation aids could help teachers feel less tense and increase their connectedness with their colleagues and school leaders. From teachers’ responses, it is quite apparent that the activities that promote teachers’ positive emotions and state of mind are of vital importance to teachers. This is further reinforced when taking into account the notion that school practices to support teachers’ mental health, such as mindfulness-based interventions, could do wonders for teachers’ wellbeing, performance, and resilience.

Enhanced communication and interaction was another suggestion that 26% of the teachers reported. Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers in this study disclosed that it was critical to strengthen social ties and maintain regular communication and interaction with their school leaders, colleagues, and students. Particularly teachers wanted their difficulties, challenges, and opinions to be heard. For example, Tue Chi shared in the interview that the leaders of her faculty did not consult much with the teachers before making a decision: “they inform us instead of consulting us, I feel that those decisions are sometimes not very practical, reasonable, and effective because the leaders of my Faculty do not teach much, they do not understand many difficulties of the teachers who actually teach.” She then emphasized the necessity of communication and connection between teachers and school leaders when she highlighted “it is more effective if the school leaders have more discussions with teachers to listen to opinions from many angles instead of making decisions on their own.” Participant 54 also agreed on this when stating “there should be a monthly or quarterly survey about teachers’ mental health status and their teaching conditions in order to listen to their needs and difficulties and provide timely support.” These extracts suggest that some participants in this study experienced insufficient communication and a lack of understanding from school leaders, and quality communication with school leaders could be advantageous to teachers’ well-being. Specifically, from the teachers’ perspective, in order to foster teachers’ occupational well-being, school administrators should understand the necessity of providing teachers with constant communication, a proactive investigation into challenges facing teachers, and timely measures to satisfy their needs during the pandemic. The interaction among teachers and between teachers and students seems to be another critical factor that can positively impact teachers’ occupational well-being since teachers cannot interact with their students in person during remote learning. Participant 8 expressed that “school leaders should develop interactive activities among teachers and between teachers and students; organize sharing sessions to create opportunities for students to express their feelings as well as show respect and gratitude to teachers.”

Appreciation and motivation were the fourth school leaders’ measure reported by 14% of the respondents, indicating teachers’ longing for their efforts to be recognized and stimulated. Van Anh, for example, emphasized the importance of receiving good comments and recognition. She listed that school leaders should “give teachers encouragement and credits for their endeavor to complete their work. The acclamation and motivation of school leaders are critical to teachers’ working spirit.” Teachers’ negative affections caused by a lack of appreciation or comprehension of the job done by teachers would probably promote their dissatisfaction and thus negatively affect their occupational well-being.

The last subtheme under the well-being initiatives theme was physical health support, which 5% of the participants mentioned. Teachers named several physical activities that school leaders could do to foster teachers’ occupational well-being, such as “give eye and back pain examination” and “give a general health check,” and “provide health-promoting exercise videos.” The current pandemic scenario is characterized by challenges that affect teachers physically and emotionally, which in turn may worsen teachers’ state of being well in the profession. Because of these new health conditions, school leaders ought to carry out occupational health schemes of health protection by alleviating occupational illnesses or ensuring teachers’ good health conditions.

Overall, in-service teachers in Hanoi had a moderate level of occupational well-being, which could be drawn from the findings of each component constituting teachers’ overall occupational well-being. Specifically, the mean values of teachers’ self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and social relations indicate that these three constructs contribute positively to teachers’ occupational well-being. These findings align with the existing literature, which emphasizes the importance of self-efficacy beliefs, job satisfaction, and positive social relationships in promoting teachers’ well-being (Mattern and Bauer, 2014; McCallum et al., 2017; Zhou and Yao, 2020). However, the psychosomatic symptoms dimension significantly hindered teachers’ state of being well while working during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, teachers’ gender is not a factor affecting their level of occupational well-being, which was also found with previous literature (Shen et al., 2015). There are minor differences in teachers’ levels of occupational well-being in terms of their age. Teachers having 1 to 3 years of experience and those teaching for 4 to 8 years had slightly lower occupational well-being than the average. The opposite is true for teachers with 9 to 18 years of experience and teachers working in their job for more than 18 years.

Furthermore, the occupational well-being of lower secondary school teachers was pretty lower than that of upper secondary school teachers and university lecturers. Regarding teachers’ teaching qualifications, teachers holding a Ph.D. had a similar level of occupational well-being to the average, while teachers with a Master’s degree had a higher level of occupational well-being, and the teachers with a Bachelor’s degree showed a slightly lower level of occupational well-being.

By reinforcing previous research findings, this study further contributes to the growing body of literature on teachers’ occupational well-being during challenging times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Identifying the specific dimensions contributing to or hindering teachers’ well-being provides valuable insights for policymakers, school administrators, and other stakeholders seeking to support and enhance teachers’ occupational satisfaction and overall well-being in similar contexts.

According to teachers’ perceptions, school leaders’ support in three key areas—teachers’ professional development in distance learning, flexibility, and well-being initiatives—played a crucial role in improving teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the same vein with Day and Qing (2009) and Carver-Thomas et al. (2021), teachers frequently highlighted the significance of professional growth and development opportunities in enhancing their well-being. These opportunities included instructional training in distance learning, technical training, provision of resources, and ensuring a manageable workload, all identified as factors that positively influenced teachers’ occupational well-being during the pandemic.

Furthermore, we found a new finding that teachers emphasized the importance of a flexible working environment that promotes time autonomy and teaching flexibility. The ability to adapt their teaching methods and schedules to meet the demands of remote instruction was seen as a significant component that elevated teachers’ occupational well-being.

In terms of school leaders’ well-being initiatives, six specific measures were identified by teachers. These measures included financial support, relaxation aids, effective communication and interaction, appreciation and motivation, and support for physical health. These findings are consistent with prior research emphasizing supportive measures’ role in promoting teachers’ well-being during challenging times. Financial support, resources for relaxation, opportunities for communication and interaction, recognition of teachers’ efforts, and support for physical health were all highlighted as important factors in improving teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This research’s findings have theoretical and practical implications that can inform policy and practice to support teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

From a theoretical standpoint, this study contributes to the existing literature on teachers’ occupational well-being by examining the specific context of Hanoi during the pandemic. Replicating and reaffirming previous findings reinforce the theoretical foundation of understanding teachers’ well-being. Moreover, the adoption of Viac and Fraser’s (2020) multidimensional framework underscores the complex nature of teachers’ occupational well-being, encompassing cognitive, subjective, physical and mental, and social dimensions. This theoretical understanding highlights the need for comprehensive support strategies that address the diverse factors influencing teachers’ well-being.

Practically, the findings carry important implications for policymakers and practitioners in the education sector. Policymakers play a crucial role in recognizing and prioritizing teachers’ occupational well-being during the pandemic. They must allocate appropriate resources to support teachers and their well-being needs. Financial support, resource provision, and policies that promote flexibility and autonomy in decision-making are essential measures that policymakers should consider. Additionally, school leaders are responsible for creating supportive environments that enhance teachers’ well-being. Prioritizing teachers’ professional development in distance learning, providing technical training and necessary resources, and fostering a flexible working environment are critical actions that school leaders can undertake. Well-being initiatives, such as financial support, relaxation aids, effective communication, appreciation, and support for physical health, should also be integrated into school practices.

Furthermore, drawing lessons from the United States context, collaboration and trust between teachers and policymakers emerge as key elements. Establishing policies that foster teacher autonomy and decision-making based on mutual trust while considering variations in working conditions can positively impact teachers’ well-being. Encouraging open communication channels and involving teachers in decision-making are practical steps toward creating a supportive and empowering work environment.

Like any research endeavor, this study is not without its limitations. Firstly, the research instruments employed in this study were specifically designed for use among teachers, which may present challenges in generalizing the findings to other occupational groups. Secondly, based on the OECD framework proposed by Viac and Fraser (2020), the framework utilized to investigate teachers’ occupational well-being is comprehensive and intricate. This framework encompasses four key elements: cognitive well-being, subjective well-being, physical and mental well-being, and social well-being, each consisting of multiple indicators. Due to practical considerations in terms of time and scope, this study focused on a single key indicator for each dimension, thereby warranting further exploration with a more extensive investigation involving additional indicators to capture the full range of teachers’ professional well-being constructs.

Another constraint pertains to the sample size of the quantitative data. In this research, 103 in-service teachers from various schools and universities in Hanoi, Vietnam, participated in the survey. However, it is worth noting that a larger sample size would be necessary to obtain nationally representative levels of teachers’ occupational well-being. Moreover, given the limited number of male teachers in the sample, it may not be ideal to conduct a robust assessment of teachers’ occupational well-being by gender. Thus, it is recommended that future studies aim for a larger sample size with gender parity to ensure more comprehensive and representative insights into teachers’ occupational well-being.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The author would like to thank Hiep-Hung Pham, Equest Education Group, Vietnam, for his valuable comments and feedback.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer HHP declared as past co-authorship with the author TT to the handling editor.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1112577/full#supplementary-material

Ali, A. M., and Razali, A. B. (2019). A review of studies on cognitive and metacognitive Reading strategies in teaching Reading comprehension for Esl/Efl learners. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 94–111. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n6p94

Allen, R., Jerrim, J., and Sims, S. (2020). How did the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic affect teacher wellbeing? London: UCL Centre For Education Policy And Equalising Opportunities.

Bauer, J., Stamm, A., Virnich, K., Wissing, K., Müller, U., Wirsching, M., et al. (2006). Correlation between burnout syndrome and psychological and psychosomatic symptoms among teachers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 79, 199–204. doi: 10.1007/s00420-005-0050-y

Bricheno, P., Brown, S., and Lubansky, R. (2009). Teacher wellbeing: a review of the evidence. Teacher Support Network 55

Carver-Thomas, D., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Virginia: Learning Policy Institute.

Carver-Thomas, D., Leung, M., and Burns, D. (2021). California teachers and Covid-19: How the pandemic is impacting the teacher workforce. Virginia: Learning Policy Institute.

Chan, M.-K., Sharkey, J. D., Lawrie, S. I., Arch, D. A. N., and Nylund-Gibson, K. (2021). Elementary school teacher well-being and supportive measures amid Covid-19: an exploratory study. School Psychol. 36, 533–545. doi: 10.1037/spq0000441

Collie, R. J. (2021). Covid-19 and teachers’ somatic burden, stress, and emotional exhaustion: examining the role of principal leadership and workplace buoyancy. Aera Open 7:986187. doi: 10.1177/2332858420986187

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., and Martin, A. J. (2015). Teacher well-being:exploring its components and a practice-oriented scale. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 33, 744–756. doi: 10.1177/0734282915587990

Cook, C. R., Miller, F. G., Fiat, A., Renshaw, T., Frye, M., Joseph, G., et al. (2017). Promoting secondary teachers’ well-being and intentions to implement evidence-based practices: randomized evaluation of the Achiever resilience curriculum. Psychol. Sch. 54, 13–28. doi: 10.1002/pits.21980

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research London: Sage Publications.

Dabrowski, A. (2020). Teacher wellbeing during a pandemic: surviving or thriving? Soc. Educ. Res. 2, 35–40. doi: 10.37256/ser.212021588

Dabrowski, A., Nietschke, Y., Taylor-Guy, P., and Chase, A. (2020). Mitigating the impacts of COVID-19: Lessons from Australia in remote education. Australian Council for Educational Research. doi: 10.37517/978-1-74286-618-5

Daniel, S. J. (2020). Education and the Covid-19 pandemic. Prospects 49, 91–96. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3

Day, C., and Qing, G. (2009). “Teacher emotions: well being and effectiveness” in Advances in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers’ lives. eds. P. A. Schutz and M. Zembylas (Springer US: Boston)

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., and Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: three decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Doble, S. E., and Santha, J. C. (2008). Occupational well-being: rethinking occupational therapy outcomes. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 75, 184–190. doi: 10.1177/000841740807500310

Fuchs, K. (2022). The difference between emergency remote teaching and E-learning. Front. Educ. 7:921332. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.921332

Hoang, A.-D., Ta, N.-T., Nguyen, Y.-C., Hoang, C.-K., Nguyen, T.-T., Pham, H.-H., et al. (2020). Dataset of ex-pat teachers in Southeast Asia's intention to leave due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Data Brief 31:105913. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105913

Holmes, E. A., O'connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., et al. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the Covid-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Kim, L. E., and Asbury, K. (2020). ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: the impact of Covid-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the Uk lockdown. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12381

Kim, L. E., Oxley, L., and Asbury, K. (2022). “My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open”: a longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 92:E12450. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12450

Klusmann, U., Richter, D., and Lüdtke, O. (2016). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion is negatively related to students’ achievement: evidence from a large-scale assessment study. J. Educ. Psychol. 108, 1193–1203. doi: 10.1037/edu0000125

Lee, J. (2020). Mental health effects of school closures during Covid-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4:421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7

Li, Q., Miao, Y., Zeng, X., Tarimo, C. S., Wu, C., and Wu, J. (2020). Prevalence and factors for anxiety during the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) epidemic among the teachers in China. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.017

Louise Barriball, K., and While, A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: a discussion paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 19, 328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01088.x

Macintyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 94:102352. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

Mattern, J., and Bauer, J. (2014). Does Teachers' cognitive self-regulation increase their occupational well-being? The structure and role of self-regulation in the teaching context. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.004

Mccallum, F., Price, D., Graham, A., and Morrison, A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: a review of the literature Sydney: Association of Independent Schools of NSW.

MOET (2020). The information and communications going along with education and training in the preventing Covid-19. Available at: https://moet.gov.vn/tintuc/Pages/phong-chong-nCoV.aspx?ItemID=6577

Nguyen, T. H. (2020). Strengthening teaching activities on television and online teaching [Tăng Cường Các Hoạt Động Dạy Học Trên Truyền Hình Và Dạy Học Trực Tuyến]. Hanoi: Ministry of Education and Training of Vietnam.

Nguyen, T. M., and Le, G. N. H. (2021). The influence of Covid-19 stress on psychological well-being among Vietnamese adults: the role of self-compassion and gratitude. Traumatology 27, 86–97. doi: 10.1037/trm0000295

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Berasategi Santxo, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., and Dosil Santamaría, M. (2021). The psychological state of teachers during the Covid-19 crisis: the challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching. Front. Psychol. 11:620718. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.620718

Passos, L., Prazeres, F., Teixeira, A., and Martins, C. (2020). Impact on mental health due to Covid-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study in Portugal and Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:6794. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186794

Pöysä, S., Pakarinen, E., and Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2021). Patterns of teachers’ occupational well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic: relations to experiences of exhaustion, recovery, and interactional styles of teaching. Frontiers In Education 6:6. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.699785

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Shen, B., Mccaughtry, N., Martin, J., Garn, A., Kulik, N., and Fahlman, M. (2015). The relationship between teacher burnout and student motivation. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 85, 519–532. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12089

Trinh, T. M. (2021). Covid 19-Chỉ Số Bình Thường Hóa Của Việt Nam Giảm. OSF Preprints: Center For Open Science.

Trung, T., Hoang, A.-D., Nguyen, T. T., Dinh, V.-H., Nguyen, Y.-C., and Pham, H.-H. (2020). Dataset of Vietnamese Student's learning habits during Covid-19. Data Brief 30:105682. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105682

Van Horn, J. E., Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., and Schreurs, P. J. G. (2004). The structure of occupational well-being: a study among Dutch teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77, 365–375. doi: 10.1348/0963179041752718

Viac, C., and Fraser, P. (2020). Teachers’ well-being: A framework for data collection and analysis. OECD Education Working Papers. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Vu, B. T., and Bosmans, G. (2021). Psychological impact of Covid-19 anxiety on learning burnout in Vietnamese students. Sch. Psychol. Int. 42, 486–496. doi: 10.1177/01430343211013875

Wu, W., and Lu, Y. (2022). Is Teachers' depression contagious to students? A study based on classes hierarchical models. Front. Public Health 10:804546. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.804546

Zhou, X., and Yao, B. (2020). Social support and acute stress symptoms (Asss) during the Covid-19 outbreak: deciphering the roles of psychological needs and sense of control. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 11:1779494. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1779494

Keywords: teachers’ well-being, education leadership, education policy, COVID-19, professional development

Citation: Duong AC, Nguyen HN, Tran A and Trinh TM (2023) An investigation into teachers’ occupational well-being and education leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ. 8:1112577. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1112577

Received: 06 December 2022; Accepted: 23 June 2023;

Published: 24 July 2023.

Edited by:

Jian-Hong Ye, Beijing Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Ngoc Phan, Vietnam Maritime University, VietnamCopyright © 2023 Duong, Nguyen, Tran and Trinh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thong Minh Trinh, dGhvbmd0MkBpbGxpbm9pcy5lZHU=

†ORCID: Thong Minh Trinh https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8984-5613

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.