95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 17 May 2023

Sec. Digital Learning Innovations

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1112337

This article is part of the Research Topic English Medium Instruction in the Middle East and North Africa View all 9 articles

Mahboubeh Rakhshandehroo1*

Mahboubeh Rakhshandehroo1* Zahra Rakhshandehroo2

Zahra Rakhshandehroo2English-medium instruction (EMI) has been rapidly adopted worldwide as a strategy for internationalization, accompanied by a substantial amount of research attention. However, research on EMI has only recently been conducted in Iran. To contribute to the ongoing growing literature, this study explores the attitudes of Iranian students and instructors toward the possibility of implementing EMI in Iran through virtual exchange (VE). In order to determine whether EMI can be used through VE in Iran, a mixed method sequential explorative study was conducted. It has been identified that the linguistic readiness of students and/or instructors is the primary barrier to the success of EMI through VE in Iran because EMI is still in its infancy. In accordance with the literature, systematic support is required at the institutional level. Yet many of the students showed interest in the idea of EMI via VE, even if it was only a short one-session VE lesson, primarily to enhance their linguistic skills and global competencies. This study proposes that integrating EMI through VE at the graduate level may be more feasible. This is because there are already more EMI seminars and classes available, students are self-directed learners, and they may be better linguistically prepared. Regarding EMI access through VE, there were advantages and disadvantages. The benefit of using VE in EMI is that EMI would be accessible even to students living in less privileged locations, but the disadvantage is that the accessibility of the Internet may not be stable, considering requiring a VPN to access some websites. It is hoped that this study will serve as a useful starting point for future research in Iran and similar settings.

English-medium instruction (EMI) has been defined differently in various contexts since it was adopted as an internationalization strategy in the 1980s (Dearden, 2014; Macaro et al., 2018). This study implements a common definition of EMI as “The use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the first language of the majority of the population is not English” (Macaro et al., 2018, p. 37). While the definition in various contexts has been primarily focused on learning content (considering language acquisition might occur as a latent benefit), the distinction between content and language learning objectives can be blurred in actual practice (Rakhshandehroo and Ivanova, 2020).

English has been used as an international lingua franca in the academic arena, even before the start of globalization in the 1980s (Montgomery, 2013). Through EMI education, students in non-Anglophone countries can now study in English. In Europe, for instance, EMI is attracting international students from diverse backgrounds as a result of the Bologna process. There has been a rapid increase in EMI throughout the world, including Asia, Latin America, and Africa (Dearden, 2014), and more recently all over the world.

The rapid adoption of EMI worldwide has been accompanied by considerable research attention on the new challenges that have emerged. In countries with less experience with EMI, the quality of EMI appears to be a common challenge, especially issues related to the linguistic limitations of students and/or instructors (Barnard, 2014). In countries with a more mature EMI education history, such as in Europe where EMI was originally adopted and rose quickly, a major challenge has been identified as the role of English in reinforcing Anglo-American hegemony and English academic imperialism. It is where English education and English research outputs have been given a privilege and therefore, other languages have been deprived of the opportunity to produce research outputs (Altbach, 2007; Wilkinson, 2013; Wallitsch, 2014). Currently, there is a growing body of research examining the benefits of using first language (L1) in EMI and translanguaging (e.g., Fujimoto-Adamson and Adamson, 2018), as well as using technology in EMI for instance virtual exchange (e.g., Helm, 2020; Reynolds, 2022) to address these challenges.

In Iran, EMI has only recently been evaluated in research (Derakhshan et al., 2021). Research on EMI in Iran has mostly focused on the attitudes of students toward accepting the concept (Ghorbani and Alavi, 2014; Zare-ee and Hejazi, 2017). This study seeks to contribute to the literature by exploring the attitudes of Iranian students and instructors toward implementing EMI through virtual exchange (VE). The present study was guided by the following main exploratory question: What are the perceptions of Iranian students and instructors regarding the benefits and drawbacks of implementing EMI through VE?

VE has been used in language teaching for quite some time as both VE and language teaching pedagogies emphasize communicative approaches (CA) and task-based learning (Dooly and Vinagre, 2021). Additionally, VE has been applied within the context of content and language-integrated learning (CLIL), in which both language and content are taught and learned (e.g., O’Dowd, 2018). As far as EMI is concerned, relatively little attention has been given to the relationship between technology in education (in particular VE) and EMI up until very recently (Querol-Julián and Camiciottoli, 2019; Helm, 2020). This is surprising because the spread of English as an international language in the academic arena and technological innovations are seen as mutually exclusive. Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are two forms of VE that have been widely implemented (Helm, 2020). As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years, virtual platforms have become increasingly popular for educational purposes.

Employing VE would be particularly beneficial when there is an insufficient number of English-speaking international students and/or instructors on campus. Through VE, international students and/or instructors can be brought virtually to home campuses (De Wit, 2020). Moreover, education can potentially become more interactive and collaborative (Ward et al., 2010; Paliwoda-Pękosz and Stal, 2015; Chuang, 2017), access to education would be easier compared to face-to-face format (Ward et al., 2010), and EMI content comprehension and learning outcomes would be enhanced (Chuang, 2017).

Based on a systematic review of instructors’ and students’ attitudes toward EMI literature available in scholarly databases, Querol-Julián and Camiciottoli (2019) indicate that language issues in EMI (36.7%) and EMI policy (28.4%) were frequent research topics. A lesser amount of attention was given to the perceptions about instructors’ training (5.5%) and understanding of EMI lectures (3.7%). Querol-Julián and Camiciottoli (2019) pointed out that almost all of these studies have focused on face-to-face EMI contexts, indicating that virtual settings should be considered in EMI research. The following small number of recent studies have explored the use of VE models in EMI (Vo, 2021; Hammond and Radjai, 2022; Rakhshandehroo, 2022; Reynolds, 2022).

Reynolds (2022) conducted research in France and proposed the term “EMI-VE.” It was found that Erasmus VE (EVE) can enhance students’ critical thinking skills and linguistic repertoire by improving their transdisciplinary learning competencies. In their study of COIL in EMI in Japan, Hammond and Radjai (2022) found that COIL in EMI displays many potentials, as it does not involve physical international mobility, which is time-consuming and expensive. The preferred approach is to integrate the COIL component into existing domestic EMI courses. Rakhshandehroo’s (2022) study pointed out that even though many EMI courses are not officially registered by the university system as COILs, EMI in Japan is increasingly using COIL. The study by Vo (2021) explored how technology can be used in EMI in Vietnam. The study showed that instructors would need professional development support in order to utilize VE in EMI, including workshops and seminars in pedagogy and digital technology, as well as revisions to the curriculum to integrate virtual learning pedagogies into the curriculum.

In the higher education sector in Iran, Persian (Farsi) is the official language. As in other parts of the world’s higher education, Iranian universities are slowly incorporating EMI into their teaching and learning processes. The literature, however, does not indicate any evidence of EMI being implemented in Iranian universities up until recently (Derakhshan et al., 2021).

Ghorbani and Alavi’s (2014) study was one of the first to explore the potential of EMI in Iran’s higher education. Iranian students and instructors were surveyed regarding their attitudes towards EMI, and neither group had different perceptions. Although participants’ attitudes were generally positive, “modifications to the Iranian educational system” (Ghorbani and Alavi's, 2014, p.9) were mentioned as a necessary first step to introduce EMI in Iranian universities.

Zare-ee and Hejazi (2017) then explored Iranian students’ attitudes toward EMI. Students from both undergraduate and graduate programs participated in the study. The views of graduate students were not significantly different from those of undergraduate students. The findings indicate that EMI is mainly viewed positively. Among the benefits are reduced translation time and costs, enhanced English proficiency for academics, and the facilitation of international academic events for students and faculty. Additionally, the study found that participants believe the university should provide systematic support before introducing EMI, including teacher training.

As Derakhshan et al. (2021) found, EMI is now practiced at a few Iranian universities, notably those with a large number of English-speaking international students. The study found that English-speaking international students are the primary target of EMI. As a major concern, linguistic limitations of students and/or instructors were reported. As in Ghorbani and Alavi (2014), Zare-ee and Hejazi (2017), and Derakhshan et al.’s (2021) also mentioned that EMI teacher training would be required as well as support from university administrators.

As described, the advantages and challenges of EMI at Iranian universities have not been extensively examined. Furthermore, no research has been conducted on the use of technology such as VE in EMI in Iran. This study aims to address the gap in the literature on VE in EMI (Querol-Julián and Camiciottoli, 2019) by examining Iranian students’ and instructors’ attitudes toward VE in EMI.

Mixed methods qualitatively driven sequential explorative design was employed. The mixed-methods research approach was chosen to gain a deeper understanding of the study topic that could not have been obtained using only one method (Shannon-Baker, 2016). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed sequentially within the same study (Ivankova et al., 2006).

The first phase of this study focused on gaining access to a broader number of research participants to better understand the research phenomenon. In the second phase, the research question was examined from different angles in greater detail. The decision for giving priority to the second phase (qualitative) was to highlight the lived (individual) experiences of the study participants through a comprehensive qualitative data analysis. During the second phase, follow-up interviews were conducted with purposefully selected survey participants (students), as well as EMI instructors.

In the second phase, with this study’s qualitatively driven origin, purposeful sampling techniques were primarily used to select study institutions and individuals in accordance with the study’s objectives (Teddlie and Yu, 2007). Since VE in EMI in Iran is a new concept, purposive sampling was selected as it does not attempt to form generalizability but instead focuses on the “depth of information generated” by the narrative data. Thus, it illustrates the possibility of not focusing on generalization (Teddlie and Yu, 2007).

In the first instance, the aim was to integrate COIL into an existing EMI course at one Iranian university. The initial aim was to assess students’ attitudes towards this newly added component to their existing EMI program. From January to April 2022, the first author contacted several Iranian EMI instructors to determine whether they would be interested in integrating COIL into their classes. Unfortunately, none of them expressed an interest in participating. Their primary concern was the risk associated with applying this novel method, which was not supported by their university administrators. Another concern was the lack of access to social media apps such as Facebook and Telegram that students frequently use to interact in COIL (In Iran, a VPN is required in order to access these apps, which results in a slower internet connection).

As Ritchie et al. (2013) point out, researchers need to be flexible, open to change, and have a profound understanding of the research settings in order to gain access to case study samples. As a result, the authors have decided to provide an online English-medium interactive workshop as a shorter version of the VE experience.

The first and second authors contacted the educational board of a large province in Iran prior to the start of the study. Following an explanation of the research goals and objectives, ethical approval was obtained. The name of the educational board, the name of the province, and any identifying information were anonymized upon their request for ethical considerations.

In August 2022, the first author conducted a two-hour virtual EMI workshop on a topic approved by the Ministry of Education. It was designed for high school seniors who were about to graduate from high school and begin their college studies. It was possible to reach a large group of senior high school students through an application called Shad.1 In response to the pandemic, the Shad application was developed for on-demand and virtual education, and through this application, all students can access courses online. Some students attended the virtual workshop live via Adobe Connect (Zoom is blocked in Iran and Adobe Connect is the most reliable platform for virtual events), but the workshop was also broadcast live via the Shad app. The fact that this workshop was held online allowed many students from different parts of Iran to participate, including those from deprived areas. Although the number of students watching the workshop via Shad is not clear, the moderator of the online event reported that approximately 1,000 students watched the live stream.

There was a possibility for a smaller number of participants to join via Adobe Connect. This enabled them to respond to the questions via the chat box and/or to unmute themselves and speak. After the workshop, students completed an online quiz via Kahoot, in which they answered questions regarding their experience with this virtual workshop. Based on two pilot surveys conducted prior to the workshop, the questionnaire’s reliability and validity were determined. There was a consent form at the start of the survey questions that explained the purpose of the research and requested consent from the students. Approximately 40% of the participants (live via Adobe Connect) gave consent and completed the online questionnaire via Kahoot (#37). To ensure that participants are not hindered by a language barrier, these questions have been written in Persian (Farsi).

The first phase focused on the representativeness of quantitative data, which required a larger sample size (Wunsch, 1986). The second phase of this study focused on gathering data from a carefully selected, small number of participants (Patton, 2002; Teddlie and Yu, 2007). In accordance with Patton’s (2002) interview guide, an interview guide was developed for this study. As the second author has experience working with senior high school students, the interview guide has been refined several times based on her comments and suggestions. An in-depth individual semi-structured interview method was selected since it ensures that the primary research question is addressed and gives the researcher the opportunity to probe further for additional information during the interviews (Patton, 2002; Smith and Osborn, 2003).

The authors conducted follow-up interviews on-site in Iran. Participants were asked if they had any questions about the study and/or the interview before the interview, and all of their questions were addressed. Researchers explained the research objectives and ensured that consent forms were signed by participants. Participation in the interviews was voluntary and took place in August 2022. The interviews were conducted in Persian (Farsi), and they were between 25 min and 60 min long. The questions were asked in Persian and the respondents had a choice to answer in Persian or English. They all decided to answer in Persian as Persian is the first language of the authors/interviewers as well as the participants. The interviews were recorded and transcribed/translated into English by the authors. It was decided to limit the number of translators to the authors in order to ensure consistency in translation and for ethical reasons. After the translation was completed, the data were back translated to ensure accuracy and identify any errors or discrepancies (Choi et al., 2012).

The table below displays the type and number of study participants, and the methods used for the generation of data collection (Table 1). Overall, in phase one, 37 students (valid number) filled out the questionnaire and in phase two, 11 interviews were conducted.

The quantitative part of the survey was analyzed using descriptive statistics. Thematic analysis was used for the open-ended questions of the survey (the qualitative data). It is defined as “a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within data” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.6). Choosing a thematic analysis of the data at a “latent level” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.13) allowed the researchers to identify or examine the underlying assumptions, concepts, and ideas beyond the semantic content of the data, thereby focusing on more than word frequencies, but also gaining a deeper understanding of the meanings that participants contributed to the study.

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guide to thematic analysis was adopted. By reading the data several times and taking notes as necessary, the researchers familiarized themselves with the data. A list of initial themes was drafted at this stage. The next step was to identify and code repeated patterns. After this, possible themes and sub-themes were searched for, reviewed, refined, and a list of themes and sub-themes was compiled. As a result of the open-ended survey questions, themes were identified that contained discursive elements that were clearly related to the research question.

Direct quotes (translation) from the transcriptions of the in-depth semi-structured interviews and/or open-ended questions of the survey are presented throughout this next section. The names of the participants, details of their affiliations, and any identifying characteristics of the participants were anonymized and coded. Each quotation is accompanied by its corresponding code/number.

The following table illustrates student participants’ responses (Table 2).

Overall, the responses were very positive. The workshop was considered useful by 97% of student participants. At the end of the workshop, many wrote in the chat box that they were interested in participating in other workshops like this in the future. 86% of student participants indicated that they would be interested in EMI courses through VE at the university. The survey included an open-ended question regarding the reasons for the participants’ decisions. Following a thematic analysis of the participants’ reasons for wishing to take EMI classes via VE, the following themes emerged (Figure 1).

The majority of participants (86%) expressed a desire to study in EMI through VE. Students’ primary concern was their linguistic abilities; however, many indicated that EMI would help them improve their English skills as well as practice and learn practical English relevant to their field of study. Several participants mentioned that VE and the use of English could be useful means of connecting with the world. For instance, several participants mentioned that the anecdotes presented by the first author about Japan in the workshop were very interesting to them and they would like to learn more about Japan and other countries in English. The participants also suggested that offering EMI courses online would be ideal since they would be accessible to all. The following extracts are some examples of student quotes (P = participant):

“Because of being in touch with the world” (P6).

“To improve my English proficiency” (P2; P9; P14; P24 [All used the same wording.])

“I like the idea of EMI via VE, because this method is different from traditional methods, it requires more student activity, and it leads to strengthening our English skills” (P32).

“Because English is important for reading academic texts in the original format and it is the language of science” (P3).

There were similar negative reasons reported by those who selected options other than “yes.” The main reason given was their lack of proficiency in English and the concern that they would not be able to keep up with content classes in English. Additionally, some participants expressed concern that they were unfamiliar with EMI and VE, and they were uncertain whether they would be able to participate despite their interest. Furthermore, a few participants stated that in deprived areas, internet connections may not be adequate for taking online courses or participating in activities.

“No, because my English proficiency is low” (P5; P10 [Both used the same wording.])

“I love English but I’m not sure whether I’ll be enjoying taking content classes in English or not” (P36).

“Because internet was cutting off a lot today in [a deprived area’s name] and it might happen again when I attend online events” (P27).

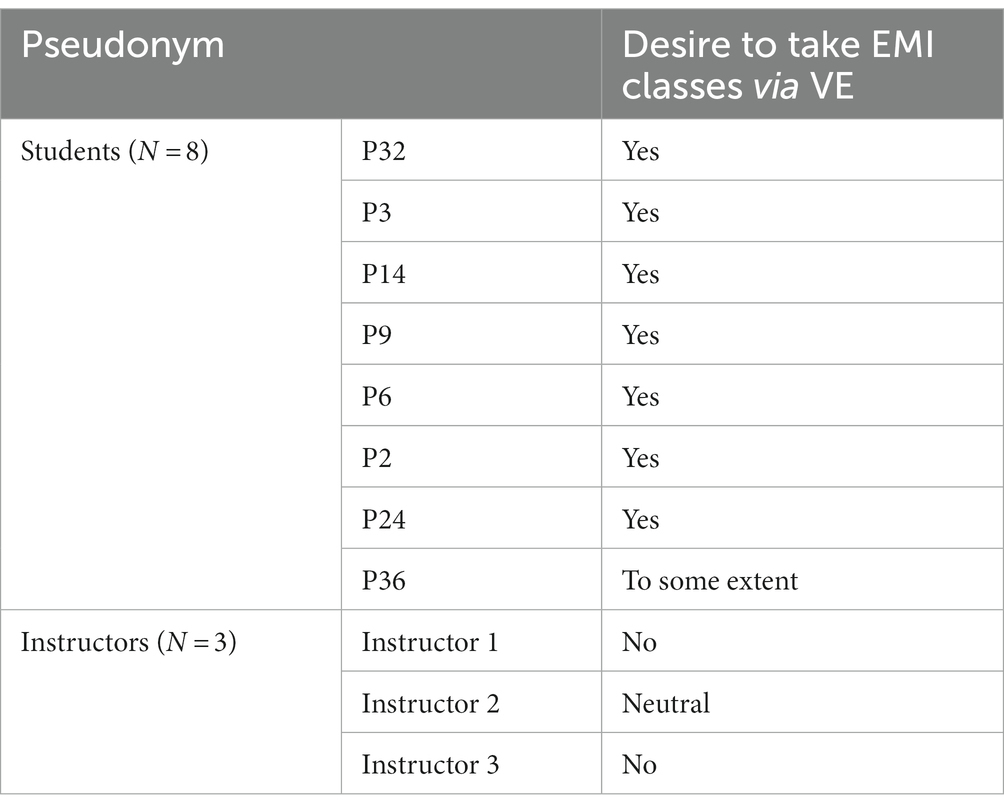

The following table presents the follow-up interview participants (see Table 3).

Table 3. Follow-up interview participants and their desire to take EMI classes via VE (Students N = 8, Instructors N = 3, phase two).

In total, 11 participants were interviewed (8 students and 3 instructors). EMI and VE were viewed positively by most students who participated in the interview. Some of the students who selected “yes” in their survey reflected only on the positive aspects of EMI via VE in their interviews (#5). Others, including the participant who selected “to some extent” in their survey, focused more on the challenges that might arise (#3). The student participants self-rated their English proficiency as near upper intermediate (#6) or advanced (#2). As in the previous phase of the study, most participants believed that EMI would improve their English skills, and that through VE they would be able to gain access to the world. In response to the question of whether employing EMI through VE would be feasible, their responses generated the following themes (Figure 2).

Many student participants believed that VE would provide an opportunity for EMI instructors from outside Iran to bring some form of EMI into Iranian classrooms virtually. In any case, it would be a valuable learning opportunity, even if it were limited to one session per semester or in the form of a workshop. Many students express that taking such classes will increase their motivation since they will be exposed to many perspectives and will be able to expand their horizons. The students perceive such classes as fun, interactive, and student-centered, in addition to giving them an opportunity to learn on their own, which they consider desirable. The following is an extract provided by participant 14:

“I believe this [EMI though VE] is not only good for improving my English, but it’d also be so fun to exchange ideas with people from diverse backgrounds and point of views. Even if it’s a small thing like the workshop you [the first author] conducted, I’m sure it’d be super beneficial” (P14).

Nevertheless, some students pointed out that this might pose challenges: The first aspect was the perceived low level of English proficiency of students (similar to phase 1). A second area of concern was the willingness of instructors to employ this method in their classes, as well as the lack of support provided by the university system. Additionally, VE may not function properly if the internet connection is not functioning in deprived areas, or if VPN is required for accessing some websites in Iran. One student, for example, stated:

“I do not think my English is that good to take classes in English…. Internet has a lot of problems in the area where I live [a deprived area’s name] … I think it’d be too much work for instructors and thus, they might not be interested…” (P36).

When instructors were asked how feasible they thought employing EMI through VE would be, their responses converged on the following themes (Figure 3).

The instructors were either senior high school teachers or undergraduate university instructors. EMI via VE was considered to be more advantageous at the graduate level, particularly in STEM subjects where English is the primary language of science. Students in these subjects are more comfortable using English in academic settings. Moreover, graduate students are more likely to study independently and have fewer course requirements. As an example, an instructor participant stated:

“I know an Iranian professor in physics department teaching all his seminar classes in English. And I’ve heard from him that it’s a common practice at [the name of an elite university]. In that case, adding EMI via VE would be a much easier transition than for us” (Instructor 2).

Overall, the instructors were not convinced that EMI through VE was employable at the senior high school level and/or at the university undergraduate level. While they discussed how this would be an excellent opportunity for students to practice academic English and use it in their future careers, they expressed concerns that students and themselves may not be adequately prepared linguistically for this transition. Alternatively, instructors mentioned that it would be dependent on the goodwill and informal efforts of individual instructors, and that there would be little or no support at their institution to facilitate this transition.

The purpose of this study was to examine Iranian students’ and instructors’ attitudes regarding the use of VE in EMI in Iran. In Iranian universities, EMI has not been extensively explored, and it is still a relatively new phenomenon (Ghorbani and Alavi, 2014; Zare-ee and Hejazi, 2017). Furthermore, very few research studies have been conducted on the use of technology such as VE in EMI (Querol-Julián and Camiciottoli, 2019). This study aimed to address this gap in the literature on VE in EMI in Iran. Derakhshan et al.’s (2021) study demonstrated that EMI serves primarily English-speaking international students in Iran. Based on the findings of this study, it may also be possible to target domestic students through VE.

Iranian student participants overwhelmingly expressed positive views. Most student participants indicated that they would be willing to participate in even a very short-term or one-session workshop or lesson and that even a one-session EMI via VE would be valuable to them. Even students living in deprived areas would be able to access EMI through VE (Ward et al., 2010). Students would be able to improve their English skills (Reynolds, 2022). A VE-based EMI is characterized by collaborative pedagogies that give learners autonomy (Ward et al., 2010; Paliwoda-Pękosz and Stal, 2015; Chuang, 2017; Reynolds, 2022). VE can also help them to expand their horizons and advance their global competencies (Hammond and Radjai, 2022; Rakhshandehroo, 2022; Reynolds, 2022).

Nevertheless, implementing EMI through VE had some drawbacks. It was noted that access to EMI via VE may not be possible at times or places in Iran due to inadequate internet connections. The use of a VPN is required for some applications and websites in Iran, which can result in a slower internet connection. There have also been concerns expressed by some students in regard to their perceived inadequacy of English proficiency (Derakhshan et al., 2021). It was noted that some students had concerns about their unfamiliarity with both EMI and VE and needed more information before taking part in such a program. Furthermore, they expressed concern about the lack of support from the university and the insufficient number of English-speaking instructors (Derakhshan et al., 2021).

In contrast to students who were generally positive, instructors were more negative toward the idea of EMI through VE, even though they believed that this would provide students with an opportunity to learn in Academic English and would be beneficial for their future careers. The main barrier identified by instructors, which was similar to students’ concerns, is the lack of linguistic readiness of students and/or instructors (Barnard, 2014; Derakhshan et al., 2021). In order to address the shortage of English-speaking instructors in EMI classrooms, the instructor participants mentioned that VE can provide English-speaking instructors virtually (De Wit, 2020). To do so, Instructors stated that their institutions must provide systematic support to them, including opportunities for professional development (Ghorbani and Alavi, 2014; Zare-ee and Hejazi, 2017; Derakhshan et al., 2021; Vo, 2021). The instructor participants pointed out that the integration of EMI through VE at the graduate level would be more feasible since more EMI courses are already available, students are more autonomous learners, and they may be better prepared linguistically. It appears that institutional support is a shared solution requested by both students and instructors to successfully employ VE in EMI.

It is the authors’ understanding that this is the first study in Iran that explores EMI through VE. There were several limitations to the study, including the fact that only participants in the Adobe Connect VE workshop were able to complete the post-workshop survey. About 40% of the participants volunteered to complete the survey and participate in the study. Further research on this topic can be conducted using a larger sample size. In addition, this study targeted senior high school students. This may be explored in future studies in university contexts, including graduate schools. According to the instructor participants, EMI is currently being practiced by domestic graduate students and this has not yet been documented in the literature. Further, this study was based on a two-hour virtual EMI workshop and follow-up interviews. It would be beneficial to explore this issue on a longer-term basis, for example through COIL projects. Despite these limitations, this study attempted to initiate discussions about how EMI might be implemented through VE in Iran. It demonstrated that EMI via VE has more advantages than disadvantages. It is hoped that this study will serve as a starting point for future research in Iran and other similar settings.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Zakariya Razi Beyza Research Center, Shiraz, Iran. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants.

MR and ZR were responsible for the design, collection, and analysis of the data. MR reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript, which was revised by ZR. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Through the individual research subsidy of MR at Kwansei Gakuin University, MR was able to visit Iran in August 2022 for data collection.

The authors would like to thank all of the study participants who volunteered to participate in the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Altbach, P. G. (2007). “Globalization and the university: Realities in an unequal world” in International handbook of higher education. ed. P. G. Altbach (Dordrecht: Springer)

Barnard, R. (2014). English medium instruction in Asian universities: some concerns and a suggested approach to dual-medium instruction. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 4, 10–22. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v4i1.597

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Choi, J., Kushner, K. E., Mill, J., and Lai, D. W. (2012). Understanding the language, the culture, and the experience: translation in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 11, 652–665. doi: 10.1177/160940691201100508

Chuang, Y.-T. (2017). MEMIS: a mobile-supported English-medium instruction system. Telematics Inform. 34, 640–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.10.007

De Wit, H. (2020). Internationalization of higher education: the need for a more ethical and qualitative approach. J. Int. Stud. 10, i–iv. doi: 10.32674/jis.v10i1.1893

Dearden, J. (2014). English as a medium of instruction–a growing global phenomenon. London: British Council.

Derakhshan, A., Rakhshanderoo, M., and Curle, S. (2021). “University students and instructors’ attitudes towards English medium instruction courses: voices from Iran” in English-medium instruction in higher education in the Middle East and North Africa: Policy, research and practice, eds. Curle S., Holi Ali H. I., Alhassan A., Saleem Scatolini S. (London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing)

Dooly, M., and Vinagre, M. (2021). Research into practice: virtual exchange in language teaching and learning. Lang. Teach. 55, 392–406. doi: 10.1017/S0261444821000069

Fujimoto-Adamson, N., and Adamson, J. (2018). “From EFL to EMI: Hydrid practices in English as a medium of instruction in Japanese tertiary contexts” in Key issues in English for specific purposes in higher education. eds. Y. Kırkgöz and K. Dikilitaş (Cham: Springer), 201–221.

Ghorbani, M. R., and Alavi, S. Z. (2014). Feasibility of adopting English-medium instruction at Iranian universities. Curr. Issues Educ. 17, 1–17.

Hammond, C. D., and Radjai, L. (2022). Internationalization of curriculum in Japanese higher education: blockers and enablers in English-medium instruction classrooms in the era of COVID-19. High. Educ. Forum 19, 87–107. doi: 10.15027/52117

Helm, F. (2020). EMI, internationalisation, and the digital. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 23, 314–325. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2019.1643823

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., and Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods 18, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05282260

Macaro, E., Curle, S., Pun, J., An, J., and Dearden, J. (2018). A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Lang. Teach. 51, 36–76. doi: 10.1017/S0261444817000350

Montgomery, S. L. (2013). Does science need a global language? English and the future of research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

O’Dowd, R. (2018). Innovations and challenges in using online communication technologies in CLIL. Theory Pract. 57, 232–240. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2018.1484039

Paliwoda-Pękosz, G., and Stal, J. (2015). ICT in supporting content and language integrated learning: experience from Poland. Inf. Technol. Dev. 21, 403–425. doi: 10.1080/02681102.2014.1003521

Querol-Julián, M., and Camiciottoli, B. C. (2019). The impact of online technologies and English medium instruction on university lectures in international learning contexts: a systematic review. ESP Today 7, 2–23. doi: 10.18485/esptoday.2019.7.1.1

Rakhshandehroo, M. (2022). Creating inclusive internationalization spaces in EMI classrooms through COIL: evidence from Japan. CIHE Perspect. 19, 32–33.

Rakhshandehroo, M., and Ivanova, P. (2020). International student satisfaction at English-medium graduate programs in Japan. High. Educ. 79, 39–54. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00395-3

Reynolds, A. (2022). EMI through virtual exchange at Bordeaux University. J. Virtual Exch. 5, 49–60. doi: 10.21827/jve.5.37479

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., and Ormston, R. Eds. (2013) Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Shannon-Baker, P. (2016). Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 10, 319–334. doi: 10.1177/1558689815575861

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2003). “Interpretative phenomenological analysis” in Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. ed. J. A. Smith (London, UK: Sage), 51–80.

Teddlie, C., and Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1, 77–100. doi: 10.1177/1558689806292430

Vo, T. (2021). The use of digital technologies in an English-medium instruction context: a case study of Vietnamese higher education teachers and students (Doctoral dissertation, open access Te Herenga waka-Victoria University of Wellington).

Wallitsch, K. N. (2014). Internationalization, English medium programs, and the international graduate student experience in Japan: a case study. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY Victoria University of Wellington (thesis).

Ward, M. E., Peters, G., and Shelley, K. (2010). Student and faculty perceptions of the quality of online learning experiences. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dis. Learn. 11, 57–77. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v11i3.867

Wilkinson, R. (2013). “English-medium instruction at a Dutch university: challenges and pitfalls” in English-medium instruction at universities: global challenges. eds. A. Doiz, D. Lasagabaster, and J. M. Sierra (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters), 3–24.

Wunsch, D. R. (1986). Survey research: determining sample size and representative response. Bus. Educ. Forum 40, 31–34.

Keywords: English-medium instruction (EMI), Iran, virtual exchange (VE), internationalization, higher education

Citation: Rakhshandehroo M and Rakhshandehroo Z (2023) The attitude of Iranian students and instructors toward implementing EMI through virtual exchange. Front. Educ. 8:1112337. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1112337

Received: 30 November 2022; Accepted: 03 May 2023;

Published: 17 May 2023.

Edited by:

Tariq Elyas, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Shizhou Yang, Payap University, ThailandCopyright © 2023 Rakhshandehroo and Rakhshandehroo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mahboubeh Rakhshandehroo, cHJha2hzaGFuZGVocm9vQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; bWFoYm91YmVoLnJAa3dhbnNlaS5hYy5qcA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.