- 1Department of Teacher Education, Faculty of Education, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

- 2Faculty of Education and Psychology, Teachers, Teaching and Educational Communities (TTEC), University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

- 3Faculty of Education, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland

Play and playfulness are understood as basic and vital elements of early childhood education (ECE), and together with playful pedagogies, they perform a central role in Finnish ECE. In multidisciplinary research, children’s learning is generally understood through the inquiring process of play. However, playfulness, as opposed to play, has received relatively little scholarly attention, and educators’ use of playfulness has received even less. Playfulness is a vital part of life for both adults and children. At the same time, teachers’ behavior can influence the playfulness of a child; moreover, teachers’ own playfulness is critical for establishing warm and secure relationships with children. As such, the aim of this research was to explore pre-service teachers’ (PsTs’) understanding of agentic playfulness, particularly in the ECE context. Study participants included 159 PsTs; study data were gathered from PsTs’ written reflections regarding the use of playfulness in their future work. The results of qualitative analyses showed that the PsTs’ agentic playfulness mirrored a relational and tensious space consisting of three domains: teacher-initiated agentic playfulness, child-centered agentic playfulness, and community-shared agentic playfulness. Each domain revealed dimensions of the nature of PsTs’ orientation of their agentic playfulness. The results are discussed in relation to pedagogization of play, relational pedagogy community of learners, and teacher education supporting and developing future ECE teachers’ agentic playfulness.

Introduction

Play, playfulness, and playful pedagogy are key components in Finnish early childhood education (ECE). By play we refer to various mind-on, hands-on and body-on activities that children experience engaging. Children make a distinction between boring and meaningful activity defines play: therefore, play is not any certain activity, which adults may refer as play (Glenn et al., 2012). We consider teachers’ playfulness through the qualities of activities, personal traits, approaches, state of mind and attitudes and motivational factors. We build playfulness in interaction with other people, environments, situations and animals (Bateson and Martin, 2013). Playful teachers can frame and reframe everyday situations in a way that teachers and children experience them entertaining, intellectually stimulating and personally interesting. They can transform any environment or situation playful, even troubles and problems as adapted from Proyer et al. (2015, 2019). Playful pedagogy integrates play, playfulness and learning in practices. However, it also integrates theoretical understanding of play and learning and is rooted in teachers’ pedagogical thinking. Playful pedagogy challenges teachers to reflect their role, where and how they position themselves, when interacting with children. In addition, playful pedagogy requires to rely on children and draw on children’s creativity and ideas, not to forget fun and enjoyment (Hyvönen, 2011). Playful teachers are both pedagogically and emotionally engaged in playful learning processes (Kangas et al., 2017). Teachers’ playfulness is important not only to implementing playful pedagogy (Kangas et al., 2018; Baker and Ryan, 2021) but also to establishing social relationships with children in contexts in which playing (e.g., Hyvönen, 2011; Johnson et al., 2019) and playfulness are resources for shared joy and creativity (Singer, 2013). Playful pedagogy can lead to or enhance playful learning. These conceptual elements can together contribute to teachers’ playful agency which refers teachers’ capacity to act intentionally and make things happen within a space of possibilities and constraints on action (Bandura, 2006).

The importance of play is emphasized also in the 2022 national curriculum for ECE (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2022; Kangas et al., 2022; Melasalmi et al., 2022). Curricula in Finnish universities in ECE teacher education programmes should be in line with the national curriculum for ECE: how they emphasize play, playfulness and playful pedagogy during the educational path. Since each university in Finland has its autonomy, the programmes also in ECE teacher education vary regarding the emphasis and implementation of the content. Generally, play is viewed vital in promoting children’s physical, cognitive and psychological growth, and development (Singer et al., 2006; Singer, 2013). Play as supportive learning context needs to be implemented thoughtfully by competent teachers. Since teachers’ dispositions and orientation towards play depend largely on the education, they receive (e.g., van der Aalsvoort Prakke et al., 2015), pre-service teachers’ playful pedagogical skills should be addressed and enhanced during their teacher education. The successful implementation of playful pedagogy for children in a group setting requires that ECE teachers (1) understand the importance of play to a child’s development (Blake, 2019), (2) become aware of one’s playfulness (Hurme et al., 2022), (3) can implement appropriate pedagogical methods (Hyvönen, 2011; Melasalmi and Husu, 2019), and can behave playfully in everyday situations (Siklander et al., 2020).

Children have rights for play and these rights have clearly been declared on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989). However, children’s playing overall has declined (Kravtsov and Kravtsova, 2010; Russ and Dillon, 2011) and it has also changed. For instance, physically active play outdoors and in the nature has declined or it is denied by adults (Evans, 2000; Egler et al., 2013; Siklander et al., 2020). Besides, declined playing, the literature has also highlighted various discourses affecting how teachers position themselves towards play, and thus, pedagogically implement ECE teaching practices (e.g., Dahlberg et al., 1999; Hatch, 2002; Cannella and Viruru, 2004; Cummins, 2007). The reasons are many, however, we focus on research-based evidence on problems dealing with playful pedagogy.

First, balancing play and learning and integrating play and learning requires teachers’ pedagogical competence and playful agency, however many factors prevent playful pedagogy. ECE teachers feel pressured when balancing play and playfulness with children’s academic achievement, which can jeopardize play and playfulness (Lynch, 2015). Although play and learning can coincide in pedagogical practices (Pramling et al., 2019), academic skill instruction too often overrules play and playful learning environments in ECE (Armstrong, 2006; Sahlberg and Doyle, 2019; see also Claxton and Carr, 2004). Some ECE personnel have difficulties in defining what play means (e.g., Wood and Bennett, 1997; Thomas et al., 2011), which obviously prevents their pursue to playful pedagogy. Play stays on the margins of the broader professional discourse (e.g., Singer, 2013; Gordon, 2014), as policies and goals of the curricula limit teachers from implementing play and playfulness (Hyvönen, 2011; Bubikova-Moan et al., 2019) and leave them uncertain about how and when to incorporate playful learning activities (Bubikova-Moan et al., 2019). Canaslan-Akyar and Sevimli-Celik (2022) uncovered a link between ECE teachers’ education and feeling pressured: specifically, they found that ECE teachers with higher levels of education felt more academic pressure and responsibility than educators with lower levels of education; therefore, the better educated ECE teachers had less room for playfulness in their work.

Second, positioning ECE teachers themselves toward play and children is a concern, since there is a wide variation of teachers’ willingness to be involved and participate in playful situations, competences to nurture children’s play skills (e.g., Hakkarainen et al., 2013; Bubikova-Moan et al., 2019), as well as in their perspectives on play (Hyvönen, 2011; Canaslan-Akyar and Sevimli-Celik, 2022). According to Hyvönen (2011), teachers can take on the role of leader, allower, or afforder. Leaders define the play, connect it to the learning goals, and ask children to follow teachers’ examples. Allowers see play as important for social interactions and friendships. Afforders can integrate play and learning in a way that allows play to still be play and enjoyable and inspiring for children. The children are more satisfied with the playful learning environment when the teacher is emotionally engaged with playful pedagogy compared with the classrooms where the teachers are less engaged with playful pedagogy (Kangas et al., 2017). Teachers’ skills and agency for positioning oneself as child-centered or child-initiated point is important for a child’s play skills, since children learn play in interaction with adults and peers (Singer, 2015). Teachers, who do not position themselves within child-centered play worlds, they usually prefer focusing on the pedagogical contents (e.g., Fleer, 2015), which may diminish the role of play and playfulness.

Balancing between play and learning and positioning oneself in pedagogical play contexts in the ECE are two scientific, educational, and practical dilemmas. They are based on different views, attitudes, perspectives, and values underlying playful pedagogical practices. Designing and implementing playful pedagogies requires ECE teachers and teacher educators to demonstrate proficiency in playfulness and pedagogy. Overall agency (Kangas et al., 2017; Pinchover, 2017; Pramling et al., 2019) is the key to resist pressures from outside, break existing practices and create new for playful pedagogy and for positioning oneself with children, colleagues, and caregivers as playful pedagogy. Thus, the aim of this research is to give voice to ECE pre-service teachers and their perspectives on playful agency.

Theoretical framework

The concept of agency

Agency is a contested yet widely used, multidimensional, theoretically complex construct that is connected to theories of practice, culture, and structure (Giddens, 1984; Archer, 2010). In this study, the understanding of agency is located within the sociocultural approach, conceptualized as a temporally and locally situated and socioculturally mediated capacity to act (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Ahearn, 2001; Campbell-Wilcox and Lawson, 2018). Hence, agency is viewed not only as a characteristic exhibited by an individual but also as a relational and cultural process that is mediated by conceptual and practical tools and signs (Holland et al., 1998).

Based on earlier theoretical understandings, having a sense of agency is generally associated with possessing certain characteristics (e.g., Pantic, 2017; Melasalmi and Husu, 2019; Schlosser, 2019). First, among these characteristics is the conception that an individual has the capacity to act intentionally and make things happen within a space of possibilities and constraints on action (Bandura, 2006). Second, agentic and purposeful actions imply will, autonomy, freedom, and choice (Bandura, 1989; Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Holland et al., 1998; Edwards and D’arcy, 2004; Greeno, 2006; Biesta and Tedder, 2007). Third, agency also refers to causal actions that occur when individuals interact with others and with their environments. Fourth, agency can also be described as a sense of being an author of or being in control of one’s actions (Haggard and Tsakiris, 2009). This degree of self-awareness is the basis for experiencing a sense of responsibility (Caspar et al., 2016). Both individuals and organizations, such as institutions of higher education, benefit from adopting an agentic outlook in their work and from implementing strategies that enhance the degree of control held by the individual (Owler and Morison, 2022).

Certain relational and contextual factors have been found to support, shape, or constrain teacher agency within one’s context (e.g., Biesta and Tedder, 2007). Practices that empower teacher agency and maintain professional autonomy and creativity can facilitate teachers’ development of agency by providing opportunities for teachers to feel ownership and control of their choices (Campbell-Wilcox and Lawson, 2018). Moreover, trust and emotional safety in both work and collegial settings are identified as being important for teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2015; Melasalmi and Husu, 2019). Therefore, pre-service teachers’ developing agency is affected by their education environment, which can lead to contradictory positioning of their agency as more relational or more oppositional (Kayi-Aydar, 2015).

Teacher agency

Teacher agency is defined as something that teachers have, that they do, and that they achieve (Biesta and Tedder, 2007).

…agency highlights that actors always act by means of their environment

rather than simply in their environment [so that] the achievement of agency will always result from the interplay of individual efforts, available resources and contextual and structural factors as they come together in particular and, in a sense, always unique situations (Biesta and Tedder, 2007, p. 137).

Agentic teachers have the capacity to act intentionally, to support students’ autonomy and agency, and to make things happen within a space of possibilities and constraints on action (Caudle et al., 2014; Kangas et al., 2018). They can make intentional choices and action plans, design appropriate directions for children, and further motivate and regulate the execution of those plans and actions (Bandura, 2006; Melasalmi and Husu, 2019). Agentic teachers purposefully imply their will, autonomy, freedom, and choice in their actions (Bandura, 1989; Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Holland et al., 1998; Edwards and D’Arcy, 2004; Greeno, 2006; Biesta and Tedder, 2007).

Agentic teacher also refers to reciprocal causal actions and relationships that emerge when they interact with children, with other adults, and with their environments (Kangas et al., 2018). Reciprocal interactions encompass physical, cognitive, socio-emotional, and motivational aspects (Engle and Conant, 2002; Edwards and D’Arcy, 2004). Interactionality can lead to joint agency as a collaborative phenomenon among teachers. Moreover, agentic teachers have a sense of agency, which can be analyzed from different perspectives, such as sense of control, sense of competence, and sense of success (Zapparoli et al., 2022). They have a feeling of voluntarily controlling their own actions and their effects, which can be an indicator of the possession of or having agency (e.g., Pantic, 2017; Melasalmi and Husu, 2019; Schlosser, 2019). Agency also encompasses teachers’ strength of resistance, which pre-service teachers can convey through proactive behaviors as they demonstrate efficacious agency (Hoy, 2016).

Agentic playfulness and teacher education

While playfulness has been described in multiple ways, researchers commonly define the concept in an adult context as an individual trait characterized by the way a person frames or reframes situations experienced as personally interesting, and/or entertaining, and/or stimulating (Barnett, 2007; Proyer, 2017; Proyer et al., 2018; Proyer and Tandler, 2020). Youell (2008) referred to playfulness as “a state of mind in which an individual can think flexibly, take risks with ideas (or interactions) and allow creative thoughts to emerge” (p. 122). Her description resembles Dewey’s (1939) view of playfulness as an attitude of the mind. Hence, playfulness as a state of mind interconnects with an individual’s agentic way of being and thinking and closely relates to the individual’s beliefs about the capacity to grow and develop abilities. In this research, we employed the concept of agentic playfulness that conceives it as the teacher’s orientation (see for example Barnett, 2007), and approach to interacting with children and other adults in pedagogical and work situations.

Teacher education programs must educate future skilled, agentic teachers willing to support and strengthen children’s well-being and, thus, their capabilities for lifelong learning (Edwards and D’Arcy, 2004). People who perceive themselves as agents capable of acting intentionally, implementing decisions, and critically reflecting on the consequences of their actions are willing and motivated to implement, develop, and transform their own actions and expertise (Sachs, 2000). Playfulness stimulates creativity and flexibility and helps to predict ways to overcom challenging situations (Bateson and Martin, 2013; Siviy, 2016) and can, therefore, promote teachers’ expertise development. Pre-service teachers’ developing sense of professional agency is a relational, socially constructed ability; therefore, the quality of the environment is a significant predictor of PsTs’ professional agency development, especially considering its social and emotional dimensions (Jääskelä et al., 2017). In other words, agency is of vital importance when considering the professional and continuing development of teachers (Biesta and Tedder, 2007; Edwards, 2017). PsTs’ agency has been emphasized as an important mediator when pursuing social and/or personal change in local educational contexts (Kumpulainen et al., 2018).

Therefore, development and support of agency is important to consider in the ECE pre-service teacher education programs for at least three reasons. First, a high level of agency supports teachers’ efforts to examine and improve their daily practices (Melasalmi and Husu, 2019). Second, agency is an emergent phenomenon, both temporal and relational. The achievement of agency is understood as an alignment of experiences and influences from the past, an orientation toward the future, and engagement with the present (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Biesta and Tedder, 2007; Mische, 2014; Priestley et al., 2015). Hence, PsTs should be able to reflect on their own learned experiences and consider them critically in order to change their way of working in a relational context. Moreover, agency should be considered in ECE pre-service teacher education programs because students’ agency should be developed throughout the span of their education, while practice, recognition, and reflection of agency should be oriented toward the future (working life) in some combination of short[er] term and long[er] term objectives. Agency is always enacted in a concrete situation with children, peers, caregivers, and personnel. Finally, practicum periods during their education afford possibilities for pre-service teachers to build their agency.

Aim and research question

The aim of this research was to explore pre-service teachers’ approaches to agentic playfulness as reflected in their working lives. The research question is the following: What kind of agentic playfulness do the pre-service teachers exhibit through their future-oriented written reflections?

Materials and methods

In Finland, ECE teacher education is research-based education given only in universities. The participants of this study were ECE PsTs (N = 208) from one university, studying their first (n = 103) or third (n = 105) academic year of the three-year early childhood teacher education program. The third-year and first-year ECE PsTs completed an online (Webropol) questionnaire as a course assignment during a class lesson conducted via Zoom (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) in the fall 2020 and spring 2021 semesters, respectively. The pre-service teachers were given 15 min to fill in the questionnaire and respond to the request at the end of the survey for their consent to our use of their answers anonymously as data. We used only the qualitative part of the data, that is, the written answers to the open-ended question How can ECE pre-service teachers use their playfulness in their future work with children? The quantitative part of the questionary, which we have not used in this study, consisted of Likert scale of Proyer’s (2012) five items (SMAP), Staempfli’s (2007) Adolescent Playfulness (APF20) scale, Glynn and Webster’s (1992) Adult Playfulness scale, and elected items of Hurt et al. (1977) innovativeness scale. The data for this study consisted of the answers (n = 159) to this only open-ended question from the survey. The average length of one answer consisted of two to three sentences, although some writings were brief showcasing PsT’s orientation, for example an answer “Playfulness increases children’s learning and reduces task-avoidant behavior.” These written answers to the open-ended question were analyzed to reveal participants’ approaches to agency.

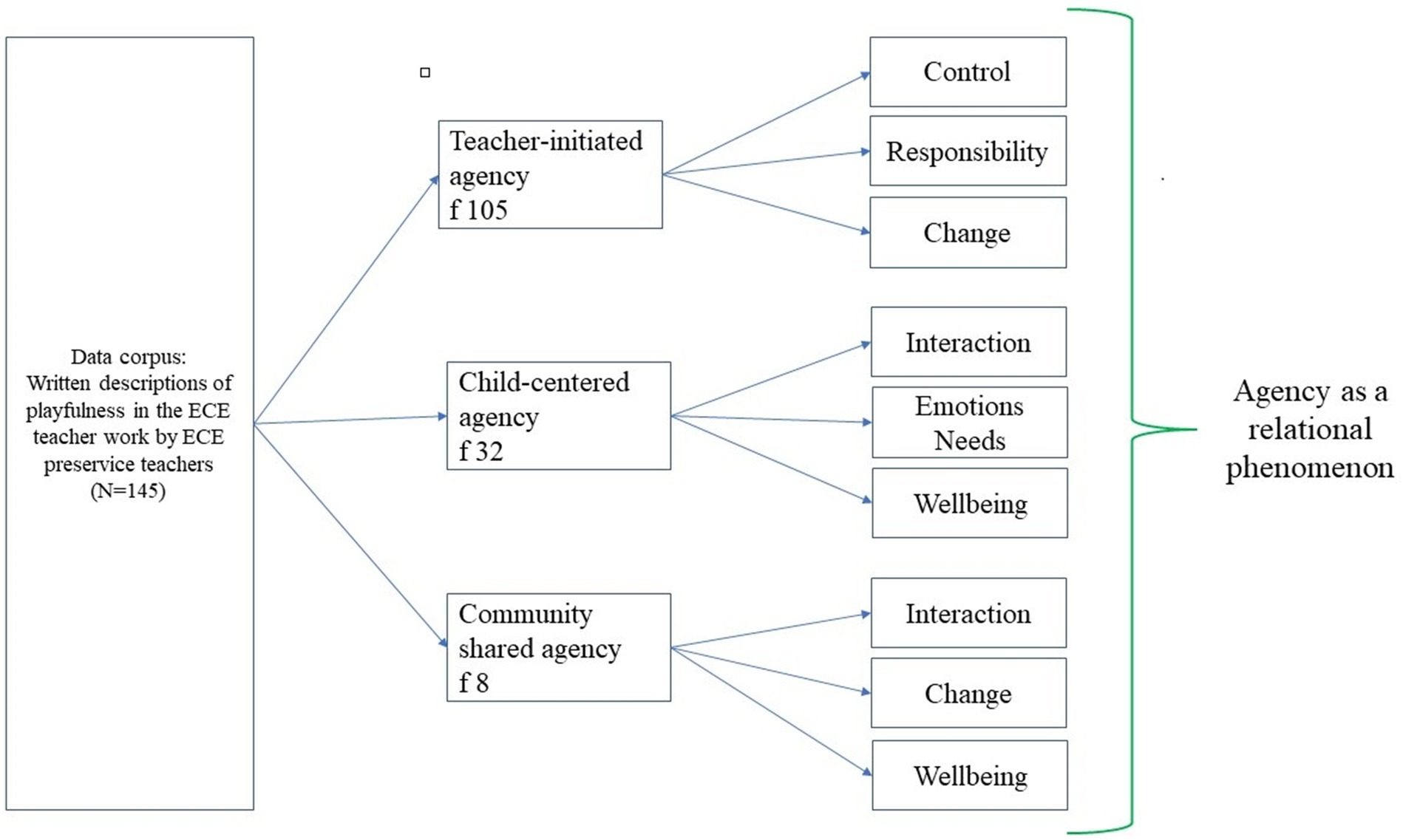

In this study conventional, data-driven content analysis was chosen as a research design (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Krippendorff, 2019). The meaning unit in the coding process was the whole sentence or sentences of one answer (e.g., Krippendorff, 2019). Research triangulation was incorporated during the methodological process. Thus, the first author coded the sentences into the three main categories: playfulness as adult centered agency, playfulness as childcentered agency, and playfulness as community shared agency. The second author verified by reading the data and conducting meaning negotiations with the first author. After negotiations the sub-categories were sorted in order to be able to give a more nuanced interpretation of the main categories. Figure 1 presents the coding process. For the reliability of the analysis a quarter of the data cases were randomly selected. The first author and fourth author independently analysed the selected part of the data and achieved 87.5% agreement. The value of Cohen’s Kappa was 0.754, indicating substantial agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977).

In the results section the main categories (Figure 1) are presented as domains, and each domain comprised subcategories which we call dimensions. Each domains’ dimensions differed, mirroring the emphasis of the PsTs’ answers.

Results

What kind of agentic playfulness do pre-service teachers exhibit through their future-oriented written reflections?

The results are presented through three broad domains that showcase how PsTs reflected and revealed their agency: teacher-initiated agency, child-centered agency, and community-shared agency. Next, we report the results according to these domains. Each domain contains dimensions that more closely reveal the nature of PsTs’ orientation of their agentic playfulness. Direct quotations that reflect the exact expressions of the participants translated into English are cited to illustrate each dimension. Lastly, in this section we interpret the results through a broader frame.

The domain of teacher-initiated agentic playfulness

Teacher-initiated agency refers to pedagogical actions that teachers direct to the children. The purpose is to reach child-centred approach that considers the children’s world; however, emphasis is placed on what teachers do and how. In this domain, teacher-initiated agency falls into three dimensions: control, responsibility, and change.

The Dimension of Control, or the feeling of having control, is part of realizing daily activities among children when PsTs feel that control is important. When emphasizing control, pre-service PsTs’ answers reflected teacher-initiated ways of being and teaching, getting the children to do what adults expected from them. Their answers related to reciprocal interactions mirrored, for the most part, cognitive and motivational aspects with more calculated perspectives. While highlighting control, PsTs focused on their pedagogical competence as teachers and being able to consider the children and their world when designing daily teaching activities and teaching. The agentic sense of purpose, therefore, was displayed through the profession. The typical focus of the agentic actions conveyed through the participants’ reflections when considering time frame was present, and in this sense, it related to understanding one’s own agentic capacity to act reactively, here and now. The following quotations highlight teacher-initiated agentic playfulness with an emphasis on control and power.

“Situations become more meaningful for children when the teacher acts funny, playfully. For example, in a dress-up situation” (participant 20). “The teacher’s ability to be playful helps in working with children, because play is a natural way for the child to act and deal with things” (participant 20). “The way children learn is through play. I think teachers benefit a lot from it if they play along with the kids and get funny” (participant 45).

The Dimension of Responsibility reflects how the ECE pre-service teachers considered children’s development and future. They recognized that responsibilities also bring power they can wield to positively impact children’s lives. When emphasizing responsibility, they described pedagogical aims as outlining teachers’ responsibility for children’s academic learning and development. Academic curriculum targets were not specifically framed, but PsTs’ answers highlighted compliance to afford opportunities for more developmental learning that will be boosted by using playfulness as a motivational component. In this view, the agentic sense of purpose also was framed through professionalism and accountability. The typical focus of the participants’ agentic actions conveyed through their reflections on time frames was on the future; thus, their understanding of their agentic capacity to act was more proactive. The following quotations represent the teacher-initiated agentic playfulness of PsTs who focused on academic outcomes while using play as a pedagogical tool for teaching purposes.

“Through playfulness and imagination, an adult can make learning and teaching much more meaningful and memorable” (participant 11). “Play allows children to be excited about something that needs to be learned, and when adult throws oneself into play so children can also become excited about it in a new way” (participant 14). “Teaching difficult things through play and fun” (participant 55). “Children learn best through play and are interested when adults throw themselves into the situation. Therefore, I feel that playfulness is one of the main pedagogical means of teaching children” (participant 57). “It [playfulness] helps to get kids excited about new things, and being playful in teaching helps [you to] motivate children to learn better and easier. Many children find learning fun, and new or tricky things are more natural and easier to approach through playfulness” (participant 61).

The Dimension of Change refers to PsTs’ thoughts on creating new practices, developing environments, innovating with new ideas, and inspiring children. They make changes to adjust to current situations and challenge themselves to move away from their usual comfort zone. Related to teacher-initiated agentic playfulness, participants also referred to professional creativity as innovating new practices and ideas to inspire children, although they recalled being inspired by children’s ideas as well. Participants’ answers, while following a creativity theme, also connected new ideas to providing an inspiring environment that supports the process of learning. In this dimension, the agentic sense of purpose was also displayed through the teaching profession and holding a teaching position, as well as by holding the power to make professional decisions in planning the teaching and learning program for the children. The following quotations signify the teacher-initiated agentic playfulness of pre-service teachers with an emphasis on creativity aiming to transform their own teaching.

“Discovering creative ways to work in early childhood education… As a teacher, children’s ideas should be considered and grasped through play and creative activities” (participant 60). “Throwing yourself into songs and daring to try new things, even if they don’t immediately succeed. Attract children to new things by being enthusiastic about the issue yourself” (participant 82). “By coming up with new ideas for the games, throwing yourself in…” (participant 114). “For example, by creating different play situations and play environments, creating educational situations within play, and being a good example for children through playfulness” (participant 177).

The domain of child-centered agentic playfulness

Child-centered agentic playfulness moves the pedagogical spotlight from the teacher to the children, who are not merely the objects for the teacher’s actions, as in the teacher-initiated approach. In a child-centered environment, teachers do not concentrate on themselves but rather use empathy-based methods and put themselves in the child’s position to see the world from the child’s perspective. The typical focus of the participants’ agentic actions as conveyed through their reflections when considering time frame was future oriented, and a central characteristic of agency in this domain was pre-service teachers’ awareness of their causal and intentional actions.

The Dimension of Interaction refers to the willingness and need to ensure successful interactions among children themselves and between adults and children. Interactions stem from children and their emotions, needs, and initiatives. Successful interactions are a basis for everyday pedagogical aims. The participants clearly highlighted the child-centered approach in which they focused on supporting successful adult–child interactions. They viewed being responsive to children’s perspectives as supporting teachers in being thoughtful in their relations with children. The following quotations represent PsTs’ interactional agency dimension with an emphasis on aiming to understand, to connect, and to listen sensitively to children.

“In the work of an ECE teacher, playfulness helps with child-centered activities – it is easier to join children’s ideas if you are a playful person. In addition, children sense the enthusiasm, receptivity, and playfulness of an adult and become excited” (participant 53). “Understanding children’s world of thoughts and perspectives becomes easier. Playfulness also brings creativity” (participant 171). “The teacher can try new ideas and participate in children’s games; she can see things from the children’s point of view” (participant 204).

The Dimension of Emotions and Needs centers on the various ways teachers focus on building positive and trusting relationships with a goal of supporting the development of a secure attachment between children and their caregivers or teachers. In their answers, the PsTs reflected on the importance of teachers’ sensitivity to children’s emotions, initiatives, and needs. Through warm interactions, time, and adult effort, a two-way relationship with the child and with peers can be established and supported. Participants stressed that successful interaction is a basis upon which other pedagogical aims were gradually set. The following quotations reflect the dimension of emotions and needs as a part of constructing child-centered agentic playfulness.

“When you get involved in children’s play, you will be able to establish a completely new kind of connection with children within play. Doing together deepens interaction with the child, and trust and familiarity on both sides increases. Genuine caring and commitment between the child and the early educator emerges. Pedagogical love, in my opinion, is more possible” (participant 70). “Children’s own opinions get better during play; by playing with children, one perceives better children’s play and starts to consider things from another point of view” (participant 103).

The Dimension of Well-Being refers to reciprocal interactions between children themselves and between children and the teacher, aiming at and/or pursuing happiness, positive affect, and good feelings. As one of the quotation reveals, the focus is on the child and the child’s self-initiated actions rather than on forcing that child to act according to a pre-determined or teacher-led purpose. One facet of this dimension was clearly viewing teacher’s playfulness as a tool for engaging with children and encouraging them to participate.

“The playful approach allows an ECE teacher to be more open to children’s initiatives, which are very often playful in nature. Playfulness also helps approach the action with more open patterns of activity, rather than forcing children to act in just one pre-determined way” (participant 65). “By getting children to feel relaxed and free to be themselves” (participant 194). “By engaging them to participate” (participants 142 and 181). “A playful attitude creates a good group spirit comprehensively” (participant 159).

The domain of community-shared agentic playfulness

Community-shared agentic playfulness is a socially constructed and shared agency, which PsTs considered to be an important part of adults’ work.

The Dimension of Interaction refers to intersubjectivity as an ability to enhance and share meaning negotiations to support and develop the quality of relationships and shared practices of the community. In addition to the focus on the adult community, the PsTs paralleled the team comprising adults and children.

“By affecting the atmosphere, motivation, and interest of work in adults and children alike” (participant 92). “You gotta get funny with the children. Humor and throwing [yourself] are important when working with children and in the team with other adults” (participant 48).

The Dimension of Change refers to teachers’ willingness to trust one another and to learn collaboratively while being responsive to a problem that requires innovative outcomes.

“Using humor and laughing at blunders are part of the playfulness of early childhood education and make the work more humane, that things are not taken too seriously, and everyone has the right to fail and try new things. Playfulness is also a strong part of spontaneous activities in early childhood education” (participant 47). “Creativity coming from children’s play, inventing and implementing new activities, inventing and implementing new ways of doing” (participant 23).

The Dimension of Well-Being refers to the well-being of the community. The participants’ answers emphasized, apart from warm interactional relations between teachers and children, also collaboration with caregivers.

“When planning and carrying out activities for children and with children. By entering relationships with children, team, and parents of children” (participant 10).

As stated before, PsTs considered community-shared agentic playfulness as important part of adults’ work. However, despite the importance of community, only eight participants’ answers highlighted teacher agency as an agency shared in the community comprising children, parents, and staff members.

Discussion

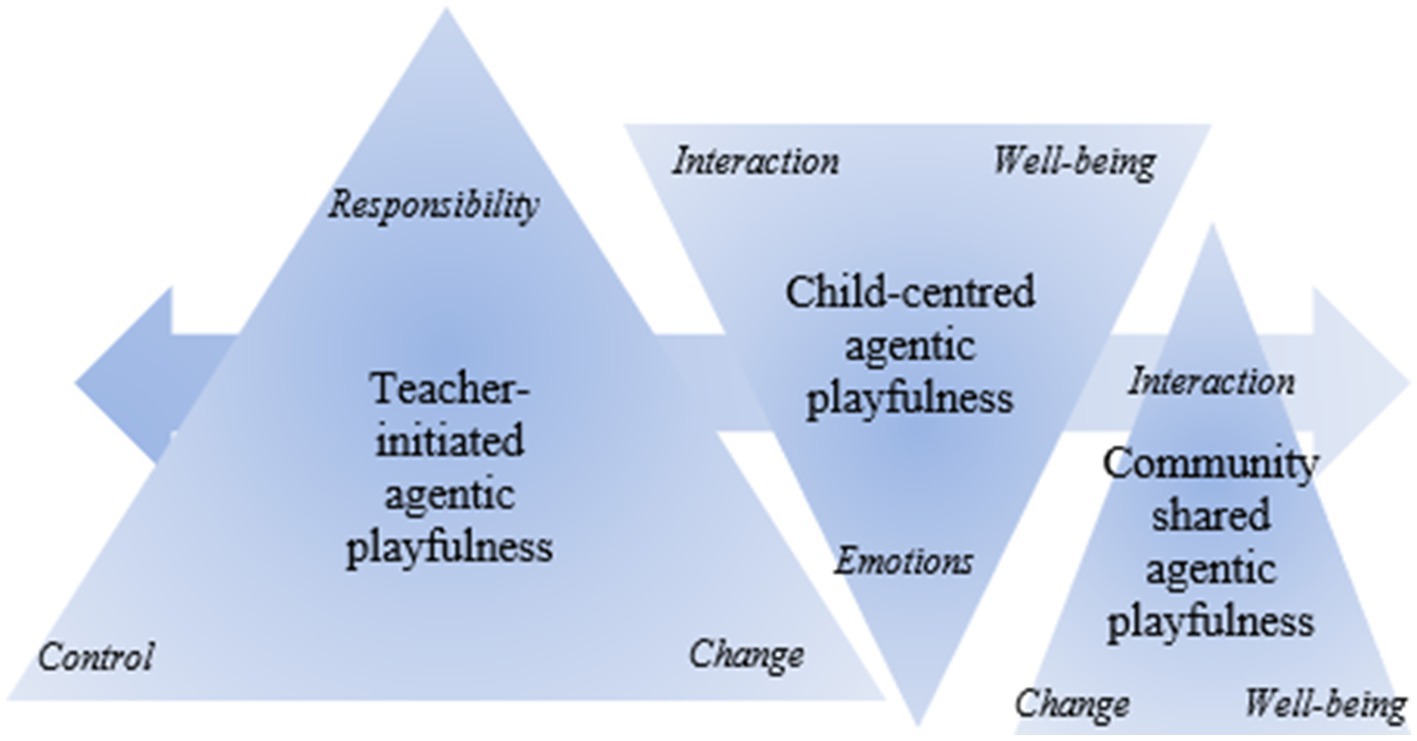

The aim of this research was to explore PsTs’ approaches to agentic playfulness in the ECE context. The results showed that the pre-service ECE teachers’ orientation regarding their own future reaching agentic playfulness constituted a continuum of relational space from restricted to shared. Through the results, a broader frame of PsTs’ agentic playfulness can be conceptualized since future ECE teachers were balancing the relational space with tensions about how to use or implement playfulness. On the other end of this relational space, perceived as a continuum, were understandings of agentic playfulness as strictly teacher-initiated and using playfulness for the purposes of teaching and learning. In the middle of this relational space, pre-service teachers conceived their agentic use of playfulness in a broader sense, focusing on building personal relationships with children to support their needs and well-being. On the other end of this continued relational space were only a few future teachers with their understanding regarding the use of playfulness as comprising the community, their team, children, and parents. Figure 2 captures this relational space of tensious understandings of agentic playfulness.

Figure 2. The relational and tensious space of future ECE teachers’ understandings of one’s own agentic playfulness.

As the relation between play and learning is challenging – for many reasons – within in-service teachers (Fleer, 2015; Ferholt et al., 2018), it is more abstract and challenging within pre-service teachers, who are novices in the field. We have also stated that the PsTs’ understanding of their agentic playfulness is developing in a tensious space. By using the word tensious, the results of three agentic playfulness domains resonate with the literature showcasing early childhood education being pressed by performed -based accountability (Hatch, 2002), structured learning (Cummins, 2007), school readiness (Cannella and Viruru, 2004), and quality measures evaluating ECE settings (Dahlberg et al., 1999; see also Biesta, 2014). Particularly the domain Teacher-initiated agentic playfulness can be viewed as being influenced by the emphasis of academic skills (see Fleer, 2015). Next, we examine the results from the four central characteristics of agency; we also discuss the importance of these results to higher education teacher education programs.

Pedagogization of play

First, the PsTs underlined their capacity to act intentionally (Bandura, 2006). However, related to teacher-initiated playful agency, the PsTs focused on teaching and learning, using playfulness as a tool to motivate children to engage in learning and fulfill their prescribed learning goals, set in advance. This domain with the detailed dimensions contained more than half of the PsTs’ answers. Thus, the results of this study do link to those of earlier studies reporting that teacher’s focus on developing children’s academic learning in ECE too often overrules play (e.g., Armstrong, 2006; Rogers, 2011; Lynch, 2015; see also Claxton and Carr, 2004; Chudacoff, 2007; Panksepp, 2007). The results also raise the question as to how willingly and agentically these future teachers who highlighted teacher-initiated playfulness are to advocate play and children’s right to play, since research has shown that ECE teachers feel pressures from other teachers, principals, and school policies to focus on academic goals and that this forces them to limit play (e.g., Armstrong, 2006; Bodrova, 2008; Hakkarainen and Bredikyte, 2014; Fleer, 2015; Lynch, 2015). However, as Pramling et al. (2019) emphasized, the dialectical relations between play and learning always emerge through the pedagogy of the teacher and the activities of the children. In this study, the domain of teacher-initiated agentic playfulness with its dimensions control, responsibility and change were clearly the biggest domain. As such, the answers of PsTs’ resemble the previous research of pre-service teachers’ conceptions of strong management skills as being vital characteristic of an effective teacher (e.g., Lin et al., 2001; Skamp and Mueller, 2001). Therefore, the relational aspects of teachers’ playfulness in their work, such as caring (Isenbarger and Zembylas, 2006), and maintaining child-centered environment (Noddings, 1984), may be perceived challenging or complex. Following Shulman (1986) PsTs are at the beginning of the process of formulating the wisdom of practice.

Relational pedagogy

Second, relational pedagogy, according to Papatheodorou (2009), is responsive to the needs, passions, and interests of learners. As acknowledged previously, agentic and purposeful actions imply will, autonomy, freedom, and choice (Bandura, 1989; Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Holland et al., 1998; Edwards and D’arcy, 2004; Greeno, 2006; Biesta and Tedder, 2007). Hence, in this study the PsTs who echoed the child-centered agentic orientation through its dimensions were genially attending to children’s well-being, participation, and emotions; therefore, the learning environment for children using relational pedagogy and child-centered agentic playfulness orientation resembles Claxton and Carr’s (2004) notion of inviting educational environments for children and adults. In this child-centered domain relational interactions, emotions and needs of children were highlighted, and thus, more complex part of playfulness shared space were highlighted. The dimensions of child-centered agentic playfulness reflect more nuanced understanding about responsive and dialogic relations between teachers and children, a skill which is seen as foundational for enhancing children’s social and emotional well-being (Bergin, and Bergin, d., 2009). As noted before, there is research literature about teachers not positioning themselves as co-players and co-meaning makers (Fleer, 2015; Hakkarainen and Bredikyte, 2019). Knowing also that relational pedagogy and child-centered agentic playfulness develop in an environment fostering trust and communication – which has often been difficult for some teachers (Ferholt et al., 2018) – and therefore, we need to pay more attention and support to play and PsTs’ awareness of their orientation towards one’s playfulness during the early childhood education.

Community-of-learners perspective

In the domain of community shared playfulness, the orientation of PsTs was future reaching, and broadly relational. That kind of environment can be viewed as potentiating “those that not only invite the expression of certain dispositions, but actively ‘stretch’ them, and thus develop them” (Claxton and Carr, 2004, pp. 91–92). Moreover, as stated previously, agency refers also to causal actions when individuals interact with others and with their environment. Agency is also a sense of being an author or of being in control of one’s actions (Haggard and Tsakiris, 2009). Since the domain of community-shared agentic playfulness held the teacher’s orientation embracing development, community, and families, it shows agentic playfulness having potential to enhance the functionality and quality of ECE (see for example Cumming et al., 2020; Ranta and Uusautti, 2022).

Teacher education supporting and developing future ECE teachers’ agentic playfulness

The results of the study prompted us to consider ways to promote pre-service teachers’ agentic playfulness in teacher education programs. Interest in the use of playful learning activities in higher education has increased in recent years (Siklander and Harmoinen, 2021; Holflod, 2022), and it should also be considered in teacher education in the future. Agentic playfulness in teachers, especially child-centered agentic playfulness, is critical for creating positive interactions and establishing warm and close relationships with children (Pinchover, 2017; Canaslan-Akyar and Sevimli-Celik, 2022). Agentic teachers have a capacity to act intentionally, to support children’ autonomy and agency, and to make things happen within a space of possibilities and constraints on action (Kangas et al., 2018). Future teachers, however, need to become aware of their playfulness (Hurme et al., 2022), internalize the importance of playfulness, and acknowledge their own playfulness potential so they can use it in their future work.

Evidence has indicated that teacher education is mainly focused on knowledge—namely, content knowledge—passing with little attention to the shared work in community (e.g., Campbell-Evans et al., 2014). For Dewey (1989), what mattered most was educating children, not merely instructing them so that they might learn. In such cases, if content knowledge is privileged, experiences are reduced to teaching and learning activities, and the role of the teacher is to “plant” the content using strategies such as direct instruction, explanations, or facilitation (Hattie and Yates, 2014). Hence, to enhance the agentic playfulness of future teachers already in teacher education, we teacher educators should pay more attention to PsTs’ developing agency, particularly focusing on collaborative, multiprofessional work supporting their teacher leadership skills during their practicums and to develop their reflective abilities (past, present, and future perspectives).

The limitations of the study and future suggestions

All research has limitations, including the present one. One limitation in this study was that the sample represented one university in Finland; therefore, the results have transferable value to similar contexts, but generalizing the results to different cultures should be done with caution. Future research would benefit if the research comprised more ECE teachers and universities. Also noteworthy is that the pre-service students were asked to consider their working life and suggest how ECE teachers can use their playfulness. We did not ask them to illustrate their agency because, obviously, agency as a relative and socioculturally mediated attribute (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Ahearn, 2001), was not familiar to them. Instead, we looked for agency reflections that were embedded in the use of playfulness in their future work with children. Therefore, we analyzed agency based on the replies regarding playfulness. Other formulations of the open-ended question may have resulted in different outcomes. Moreover, there is still room for future research related to pre-service teachers’ awareness of their playfulness. By using different methodological approaches more complex and illustrative understanding could be achieved.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data has been gathered anonymously but the participants are not requested to give permission to use the data outside the research group. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YW5pdHRhLm1lbGFzYWxtaUB1dHUuZmk=.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the reviewers for the constructive comments for improving the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 30, 109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

Archer, M. (2010). Routine, reflexivity, and realism. Soc. Theory 28, 272–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01375.x

Armstrong, T. (2006). The best schools: How human development research should inform educational practice. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Baker, M., and Ryan, J. (2021). Playful provocations and playful mindsets: teacher learning and identity shifts through playful participatory research. Int. J. Play 10, 6–24. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2021.1878770

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 44, 1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of playfulness in young adults. Personal. Individ. Differ. 43, 949–958. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.018

Bateson, P., and Martin, P. (2013). Play, playfulness, creativity and innovation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bergin, C., and Bergin, d. (2009). Attachment in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 21, 141–170. doi: 10.1007/s10648-009-9104-0

Biesta, G. (2014). Measuring what we value or valuing what we measure. PEL 51, 46–57. doi: 10.7764/PEL.51.1.2014.5

Biesta, G., and Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: towards an ecological perspective. Stud. Educ. Adults 39, 132–149. doi: 10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545

Blake, P. (2019). “Being a playful teacher” in The importance of play in early childhood education: Psycholanalytic, attachment, and developmental perspectives. eds. M. Charles and J. Bellinson (Milton: Routledge), 77–90.

Bodrova, E. (2008). Make-believe play versus academic skills: a Vygotskian approach to today’s dilemma of early childhood education. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 16, 357–369. doi: 10.1080/13502930802291777

Bubikova-Moan, J., Hjetland, H. N., and Wollscheid, S. (2019). ECE teachers’ views on play-based learning: a systematic review. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 27, 776–800. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2019.1678717

Campbell-Evans, G., Stamapoulos, E., and Maloney, C. (2014). Building leadership capacity in early childhood pre-service teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 42–49. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n5.3

Campbell-Wilcox, K., and Lawson, H. (2018). Teachers’ agency, efficacy, engagement, and emotional resilience during policy innovation implementation. J. Educ. Chang. 19, 181–204. doi: 10.1007/s10833-017-9313-0

Canaslan-Akyar, B., and Sevimli-Celik, S. (2022). Playfulness of early childhood teachers and their views in supporting playfulness. Education 3-13 50, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2021.1921824

Cannella, G. S., and Viruru, R. (2004). Childhood and postcolonization: Power, education and contemporary practice. New York: Routledge Falmer.

Caspar, E. A., Christensen, J. F., Cleeremans, A., and Haggard, P. (2016). Coersion changes the sense of agency in the human brain. Curr. Biol. 26, 585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.067

Caudle, L. A., Moran, M. J., and Hobbs, M. K. (2014). The potential of communities of practice as contexts for the development of agentic teacher leaders: a three year narrative of one early childhood teacher's journey. Act. Teach. Educ. 36, 45–60. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2013.850124

Chudacoff, H. P. (2007). Children at play: An American history. New York: New York University Press.

Claxton, G., and Carr, M. (2004). A framework for teaching learning: the dynamics of disposition. Early Years 24, 87–97. doi: 10.1080/0957514032000179089

Cumming, T., Logan, H., and Wong, S. (2020). A critique of the discursive landscape: challenging the invisibility of early childhood educators’ well-being. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 21, 96–110. doi: 10.1177/1463949120928430

Cummins, J. (2007). Pedagogies for the poor? Realigning reading instruction for low-income students with scientifically based reading research. Educ. Res. 36, 564–572. doi: 10.3102/0013189X07313156

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P., and Pence, A. R. (1999). Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: Postmodern perspectives. London: Falmer Press.

Dewey, J. (1939). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Heath.

Dewey, J. (1989). “How we think” in John Dewey the later works. vol. 8. ed. J. A. Boydston, (Carbondale, III: Southern Illinois University Press).

Edwards, A. (2017). “The dialectic of person and practice: how cultural-historical accounts of agency can inform teacher education” in The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education. eds. J. Clandinin and J. Husu (London: SAGE), 269–285.

Edwards, A., and D’arcy, C. (2004). Relational agency and disposition in sociocultural accounts of learning to teach. Educ. Rev. 56, 147–155. doi: 10.1080/0031910410001693236

Egler, C. R., Kearns, R. A., and Witten, K. (2013). Seasonal and locational variations in children’s play: implications for wellbeing. Soc. Sci. Med. 91, 178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.034

Emirbayer, M., and Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? Am. J. Sociol. 103, 962–1023. doi: 10.1086/231294

Engle, R. A., and Conant, F. R. (2002). Guiding principles for fostering productive disciplinary engagement: explaining an emergent argument in a community of learners classroom. Cogn. Instr. 20, 399–483. doi: 10.1207/S1532690XCI2004_1

Evans, J. (2000). Where do the children play? Child. Aust. 25, 35–40. doi: 10.1017/S1035077200009706

Ferholt, B., Lecusay, R., and Nilsson, M. (2018). “Adult and child learning in playworlds” in The Cambridge handbook of play: Developmental and disciplinary perspectives. eds. P. Smith and J. Roopnarine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 511–527.

Finnish National Agency for Education (2022). National core curriculum for early childhood education and care. Regulations and guidelines, vol. 2022, 2a.

Fleer, M. (2015). Pedagogical positioning in play – teachers being inside and outside of children's imaginary play. Early Child Dev. Care 185, 1801–1814. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2015.1028393

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society?: Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity.

Glenn, N. M., Knight, C. J., Holt, N. L., and Spence, J. C. (2012). Meanings of play among children. Childhood 20, 185–199. doi: 10.1177/0907568212454751

Glynn, M. A., and Webster, J. (1992). The adult playfulness scale: an initial assessment. Psychol. Rep. 71, 83–103. doi: 10.2466/PR0.71.5.83-103

Greeno, J. G. (2006). Authoritative, accountable positioning and connected, general knowing: progressive themes in understanding transfer. J. Learn. Sci. 15, 537–547. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls1504_4

Haggard, P., and Tsakiris, M. (2009). The experience of agency: feelings, judgements, and responsibility. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18, 242–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01644.x

Hakkarainen, P., and Bredikyte, M. (2014). “Understanding narrative as key aspect of play” in The Sage handbook of play and learning in early childhood. eds. L. Brooker, M. Blaise, and S. Edwards (SAGE), 240–251.

Hakkarainen, P., and Bredikyte, M. (2019). “The adult as a mediator of development in children’s play” in The Cambridge handbook of play: Developmental and disciplinary perspective. eds. K. Smith and J. L. Roopnarine (Cambridge university Press), 457–474.

Hakkarainen, P., Bredikyte, M., Jakkula, K., and Munter, H. (2013). Adult play guidance and children’s play development in a narrative play-world. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 21, 213–225. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2013.789189

Hatch, J. A. (2002). A special section on personalized instruction accountability shovedown: resisting the standards movement in early childhood education. Phi Delta Kappan 83, 457–462. doi: 10.1177/003172170208300

Hattie, J., and Yates, G. (2014). Visible learning and the science of how we learn. Abingdon: Routledge.

Holflod, K. (2022). Playful learning and boundary-crossing collaboration in higher education: a narrative and synthesising review. J. Furth. High. Educ. 47, 465–480. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2022.2142101

Holland, D. C., Lachicotte, W., Skinner, D., and Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hsieh, H.-F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Hurme, T-R., Siklander, S.P., and Kangas, M., and Melasalmi, A. (2022). Pre-service early childhood teachers’ perceptions of their playfulness and inquisitiveness. Manuscript submitted.

Hurt, H. Y., Joseph, K., and Cook, C. D. (1977). Scales for the measurement of innovativeness. Hum. Commun. Res. 4, 58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00597.x

Hyvönen, P. (2011). Play in the school context? The perspectives of Finnish teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 65–83. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2011v36n8.5

Isenbarger, L., and Zembylas, M. (2006). Teach. Teach. Educ. 22, 120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.002

Jääskelä, P., Poikkeus, A.-M., Vasalampi, K., Valleala, U. M., and Rasku-Puttonen, H. (2017). Assessing agency of university students: validation of the AUS scale. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 2061–2079. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1130693

Johnson, J. E., Sevimli-Celik, S., Al-Mansour, M. A., Tunçdemir, T. B. A., and Dong, P. I. (2019). “Play in early childhood education” in Handbook of research on the education of young children. 4th edn. ed. O. N. Saracho (New York, NY: Routledge), 165–175.

Kangas, J., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Brotherus, A., Gearon, L. F., and Kuusisto, A. (2022). Outlining play and playful learning in Finland and Brazil: a content analysis of early childhood education policy documents. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 23, 153–165. doi: 10.1177/1463949120966104

Kangas, M., Siklander, P., Randolph, J., and Ruokamo, H. (2017). Teachers' engagement and students' satisfaction with a playful learning environment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 63, 274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.018

Kangas, M., Vuojärvi, H., and Siklander, P. (2018). Hiking in the wilderness: interplay between teachers’ and students’ agencies in outdoor learning. Educ. North 25, 7–31. doi: 10.26203/6cjt-cj31

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). Teacher agency, positioning, and English language leaners: voices of pre-service classroom teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 45, 94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.09.009

Kravtsov, G. G., and Kravtsova, E. E. (2010). Play in L.S. Vygotsky’s nonclassical psychology. J. Russ. East Eur. Psychol. 48, 25–41. doi: 10.2753/RPO1061-0405480403

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 4th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Kumpulainen, K., Kajamaa, A., and Rajala, A. (2018). Understanding educational change: agency-structure dynamics in a novel design and making environment. Digit. Educ. Rev. 33, 26–38. doi: 10.1344/der.2018.33.26-38

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Lin, H.-L., Hazareesingh, N., Taylor, J., Gorrell, J., and Carlson, H. L. (2001). Early childhood and elementary preservice teachers’ beliefs. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 22, 135–150. doi: 10.1080/1090102010220302

Lynch, M. (2015). More play, please: the perspective of kindergarten teachers on play in the classroom. Am. J. Play 7, 347–369.

Melasalmi, A., Hurme, T.-R., and Ruokonen, I. (2022). Purposeful and ethical early childhood teacher: the underlying values guiding Finnish early childhood education. ECNU Rev. Educ. 5, 601–623. doi: 10.1177/20965311221103886

Melasalmi, A., and Husu, J. (2019). Shared professional agency in early childhood education: an in-depth study of three teams. Teach. Teach. Educ. 84, 83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.05.002

Mische, A. (2014). “Relational sociology, culture and agency” in The SAGE handbook of social network analysis. eds. J. Scott and P. J. Carrington doi: 10.4135/9781446294413.n7

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics & moral education. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Owler, K., and Morison, R. L. (2022). ‘I always have fun at work’: how ‘remarkable workers’ employ agency and control in order to enjoy themselves. J. Manag. Organ. 26, 135–151. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2019.90

Panksepp, J. (2007). Can play diminish ADHD and facilitate the construction of the social brain? J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 16, 57–66.

Pantic, N. (2017). An exploratory study of teacher agency for social justice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 66, 219–230. doi: 10.10616/j.tate.2017.04.008

Papatheodorou, T. (2009). “Exploring relational pedagogy” in Learning together in the early years: Exploring relational pedagogy. eds. T. Papatheodorou and J. Moyles (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge), 3–17.

Pinchover, S. (2017). The relation between teachers’ and children’s playfulness: a pilot study. Front. Psychol. 8:2214. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02214

Pramling, N., Wallerstedt, C., Lagerlöf, P., Björklund, C., Kultti, A., Palmér, H., et al. (2019). Play-responsive teaching in early childhood education. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Proyer, R. T. (2012). Development and initial assessment of a short measure for adult playfulness, the SMAP. Personal. Individ. Differ. 53, 989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.018

Proyer, R. T. (2017). A new structural model for the study of adult playfulness: assessment an exploration of an understudied individual differences variable. Personal. Individ. Differ. 108, 113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.011

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Bertenshaw, E., and Brauer, K. (2018). The positive relationships of playfulness with indicators of health, activity, and physical fitness. Front. Psychol. 9:1440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01440

Proyer, T. R., and Tandler, N. (2020). An update on the study of playfulness in adolescents: its relationship with academic performance, well-being, anxiety, and roles in bullying-type-situations. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 73–99. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09526-1

Proyer, R. T., Tandler, N., and Brauer, K. (2019). “Playfulness and creativity: a selective review” in Creativity and humor. eds. S. R. Luria, J. C. Kaufman, and J. Baer (London: Academic Press), 43–60.

Proyer, R. T., Wellenzohn, S., Gander, F., and Ruch, W. (2015). Toward a better understanding of what makes positive psychology interventions work: predicting happiness and depression from the person x intervention fit in a follow-up after 3.5 years. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 7, 108–128. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12039

Ranta, S., and Uusautti, S. (2022). “Functional teamwork as the foundation of positive outcomes in early childhood education and care settings” in Positive education and work: Less struggling, more flourishing. eds. S. Hyvärinen, T. Äärelä, and S. Uusiautti (Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 195–221.

Rogers, S. (2011). Rethinking play and pedagogy in early childhood education: Concepts, contexts and cultures. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Russ, S. W., and Dillon, J. A. (2011). Changes in children’s pretend play over two decades. Creat. Res. J. 23, 330–338. doi: 10.1081/0400419.2011.621824

Sahlberg, P., and Doyle, W. (2019). Let the children play: For the learning, well-being, and life success of every child. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schlosser, M. (2019). Agency. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2019). Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/agency/

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 15, 4–14. doi: 10.2307/1175860

Siklander, P., Ernst, J., and Storli, R. (2020). Young children’s perspectives regarding rough and tumble play: a systematic review. J. Early Child. Educ. Res. 9, 551–572.

Siklander, P., and Harmoinen, S. (2021). Ice age is approaching: triggering university students’ interest and engagement in gamified outdoor playful learning activities. Science and Drama: Contemporary and creative approaches to teaching and learning, chapter 8. eds. P. White, J. Raphael, and K. van Cuylenburg (Cham: Springer), 125–143.

Singer, E. (2013). Play and playfulness, basic features of early childhood education. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 21, 172–184. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2013.789198

Singer, E. (2015). Play and playfulness in early childhood education and care. Psychol. Russ.: State Art 8, 27–35. doi: 10.11621/pir.2015.0203

Singer, D., Golinkoff, R. N., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2006). Play=learning: How play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Siviy, S. M. (2016). Brain motivated to play: insights into the neurobiology of playfulness. Behaviour 153, 819–844. doi: 10.1163/1568539X-00003349

Skamp, K., and Mueller, A. (2001). Student teachers’ conceptions about effective primary science teaching: a longitudinal study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 23, 331–351. doi: 10.1080/09500690119248

Staempfli, M. B. (2007). Adolescent playfulness, stress perception, coping and well being. J. Leis. Res. 39, 393–412. doi: 10.1080/00222216.2007.11950114

Thomas, L., Warren, E., and deVries, E. (2011). Play-based learning and intentional teaching in early childhood contexts. Australas. J. Early Childhood 36, 69–75. doi: 10.1177/183693911103600410

van der Aalsvoort Prakke, B., Howard, J., König, A., and Parkkinen, T. (2015). Trainee teachers’ perspectives on play characteristics and their role in children’s play: an international comparative study amongst trainees in the Netherlands, Wales, Germany and Finland. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 23, 277–292. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1016807

Wood, E., and Bennett, N. (1997). The rhetoric and reality of play: teachers’ thinking and classroom practice. Early Years 17, 22–27. doi: 10.1080/0957514970170205

Youell, B. (2008). The importance of play and playfulness. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 10, 121–129. doi: 10.1080/13642530802076193

Keywords: playful teacher, agency, pre-service teacher, pedagogy, early childhood teacher education, teacher education

Citation: Melasalmi A, Siklander S, Kangas M and Hurme T-R (2023) Agentic playful pre-service teachers: positionings from teacher-initiated playful teacher to community-shared playful teacher. Front. Educ. 8:1102901. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1102901

Edited by:

Alexander Röhm, Technical University Dortmund, GermanyReviewed by:

Jenni Salminen, University of Jyväskylä, FinlandDavid Sobel, Antioch University New England, United States

Copyright © 2023 Melasalmi, Siklander, Kangas and Hurme. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anitta Melasalmi, YW5pdHRhLm1lbGFzYWxtaUB1dHUuZmk=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share third authorship

Anitta Melasalmi

Anitta Melasalmi Signe Siklander

Signe Siklander Marjaana Kangas

Marjaana Kangas Tarja-Riitta Hurme1‡

Tarja-Riitta Hurme1‡