- The National Research Centre of Giftedness and Creativity, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

Due to the special needs of gifted students, it is crucial that their teachers are carefully selected in order to give gifted students the greatest educational experience. The study involved 120 teachers from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates along with 300 gifted students, both males (n = 144) and females (n = 156). Teachers of gifted students involved in the study were asked to complete the Preferred Teacher Characteristics Scale (PICS); additionally, teachers filled out a background questionnaire. While gifted students responded to three open-ended questions, The findings corroborated the idea that gifted students perform better in an environment where their teachers’ personalities are evident. This finding was in line with the preferences of teachers as measured by the PCIS scale, which revealed that students tended to value teachers more for their personal characteristics than for their professional ones. Many personal characteristics were highly regarded by the gifted students, who in this study believed they contributed to a teacher’s effectiveness. Personal integrity, tolerance, tenderness, friendliness, a sense of humor, and an openness to new experiences were among these characteristics.

1. Introduction

The teacher is without a doubt the most important part of any educational program’s success. In education, teacher efficiency has been related to a variety of affecting variables such as students’ families’ backgrounds and socioeconomic status (Berliner, 2006), as well as the educational authority (Tomlinson, 1998). Teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs have a significant influence on students’ cognitive development (Lupascua et al., 2014). More than simply imparting knowledge, the teacher is also responsible for training and qualifying students to meet society’s various demands and to take part in its advancement by overcoming the problems and obstacles that impede growth and progress. As a result, every study of gifted students and their treatment has emphasized the need for the teacher to have a set of professional, social, and personal characteristics (Mahfouz, 2015). Individual teachers had the greatest impact on student progress, according to recent studies using multilevel modeling techniques (Goldstein, 2003). Berliner (1986) also pointed out that evaluating effective teachers is necessary to get a better understanding of how to effectively teach students. In a survey of twenty-one gifted education professionals, Renzulli (1968) found that the teacher was the most important factor in the success of gifted programs. Knowing what makes a really good teacher can benefit teachers both now and in the future in the classroom. Brown and McIntyre (1993) suggested that we consider the perspectives of students in the classroom and the literature on the characteristics of effective teachers when considering the craft of good teaching from an unbiased perspective that is not based on previous assumptions or models of what effective teaching requires (Brown and McIntyre, 1993; Su, 2006). In fact, in many studies, gifted students’ perceptions have been utilized to identify effective teachers (Berliner, 1986; Brown and McIntyre, 1993; Su, 2006; Kornelia and Wilhelmina, 2009). By taking into account the preferences of gifted students as part of the educational process, teachers and school administrators can boost the achievement and motivation of gifted students (Chae and Gentry, 2011). The needs of gifted students should be understood by school administrators and teachers; otherwise, these individuals may become disinterested in learning, develop poor study habits, and exhibit behavioral issues. One of the biggest factors is how teachers act, which can stop students from getting better and concentrating on their lessons (Hosgorur and Gecer, 2012). It is possible that the discrepancy between what gifted students prefer for the traits of their teachers and what teachers think their gifted students might prefer for their teachers can create a less-than-ideal learning environment, given insights that emerge from analysis of data from various studies (Su, 2006; Kornelia and Wilhelmina, 2009; Leavitt and Geake, 2009; Mahfouz, 2015; Burstow, 2018; Yasar, 2018). That posit that learning the largest occurs when students are in a learning environment where their preferred teacher behavior matches the teacher’s attributes. According to these studies, gifted students’ teachers need to have a good understanding of the needs of gifted students so that they can achieve a balance of personal and professional characteristics that is more in line with students’ preferences.

The student perspective is critical since, aside from their teachers, students are the only ones who are aware of how lessons are done regularly (Cooper and Mcintyre, 1996; Gargani and Strong, 2014; Johnsen, 2021). Students will have had exposure to a range of teachers, teaching methods, and techniques by the time they reach high school, giving them a wealth of comparison data from which to choose. While the general literature on teacher effectiveness may define effective teaching as fostering students’ affective and personal development besides curriculum mastery, the literature on gifted education may recognize the need to foster gifted students’ specific affective and personal development, with an emphasis on fostering gifted students’ particular aptitudes, possibly beyond the usual measures of curriculum mastery (The Arab Center for Educational Research for the Gulf States, 2020; Education and Training Evaluation Commission, 2022). According to studies done, more emphasis should be placed on adapting teaching and education methods to the needs of gifted students to prevent underachievement (Benbow and Stanley, 1996; Rimm, 1997; Gross, 1999).

2. Study problem

There appears to be a new drive in gifted education to investigate the impact that teachers can have on gifted students, particularly to assist them in developing and succeeding at the high levels that are expected of them. Despite the popular belief that gifted students can achieve academic success without the help of their teachers or the attention of their schools (Gross, 1999; Şahin and Çetinkaya, 2015; Burstow, 2018), many studies show how this group is affected by a lack of care, educational neglect, and disinterest (Su, 2006; Kornelia and Wilhelmina, 2009; Aboud, 2020; Alamiri, 2020). According to Gagné (2003), “giftedness” is defined as a high level of achievement or performance (within at least the upper 10% of age peers in the relevant fields). He merely asserts that, while giftedness requires attention to develop, being gifted itself does not guarantee that giftedness will develop. Environmental factors, such as the quality of gifted school education, he claims, act as accelerators for the development of giftedness. This does not eliminate the need to improve teacher efficiency. As a result, gifted education literature may better comprehend the goal of supporting gifted students’ outstanding effectiveness and personal growth (Aljughaiman, 2010; Aljughaiman et al., 2016; Worrell et al., 2019; Alamiri, 2020). The study’s critical question is: why are certain teachers more effective than others at teaching certain students, particularly gifted students? What characteristics differentiate effective teachers of gifted students from others? Teachers promote the academic and intellectual development of the students they teach. Each teacher is a unique individual with a different personality, life experiences, and worldwide perspective (Al-Anzi, 2006; Colangelo and Davis, 2008). Some argue that teachers who are highly effective with one group of students may not be as effective with other groups (Mills, 2003). By examining the agreement between gifted students’ perceptions of their gifted teachers and the teachers’ perceptions of what their students may appreciate about the effective characteristics of their teachers, the current study sought to determine whether the characteristics of teachers who work with gifted students differ significantly in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates. Additionally, the findings of the qualitative data were obtained from three open-ended questions. The gifted students were given the following questions to answer: (1) What makes a teacher effective? (2) What professional characteristics do you believe make a teacher effective? (3) What personal characteristics do you believe make a good teacher?

3. Characteristics of effective gifted teachers

Because of the unique nature of gifted students, their teachers must be chosen carefully to ensure that gifted students have the best possible educational experience. Many categories of desirable characteristics in teachers of the gifted can be found in the literature, which can be divided into personal characteristics and professional characteristics. Capabilities, behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, personal characteristics, and knowledge are often included in these aspects of teacher personalities. The perceived benefits of the two proposed categories in training and selection are one rationale for employing them. Su (2006) argues that while personal characteristics can be chosen for, they are more difficult to modify than professional competence, which can be taught and acquired more easily through training. Whitton (1997) reported in her study of New South Wales primary school teachers they lacked comprehension of gifted students and made only minor adjustments to their teaching for them, which she attributed to a lack of teacher training. As a result, it makes sense to recognize the professional qualities that should be incorporated into teacher training. Teachers’ education can impact personal characteristics, such as modifying teachers’ attitudes regarding gifted students and how to meet their needs (Hansen and Feldhusen, 1994; Mahfouz, 2015). It’s important to remember that developing certain professional skills can help you develop certain personal characteristics, and vice versa, so treating them as two distinct categories might mislead you (Su, 2006). Effective teachers of gifted students, according to Ferrell et al. (1988), have unique teaching styles and are more motivated in the classroom than successful classroom teachers. Effective teachers, according to Lupascua et al. (2014), have clarity about their educational goals, are conversant with educational and training content, have good communication skills, and continually monitor their students’ understanding. They seek to improve and support their teaching methods. Mills’ study results show that certification and formal training in gifted and talented education may not be enough to consider when selecting teachers for gifted students. Instead, selecting teachers with strong experience in the academic discipline being taught, as well as those who have a passion for the subject, may be equally crucial. This is beside their knowledge (2003).

4. Definition of key terms

4.1. Gifted student

The Saudi Arabian Ministry of Education has expanded the definition of a “gifted student,” defining it as a student who excels above the rest of their peers in one or more of the areas valued by society, particularly in the areas of mental excellence, academic achievement, creativity and innovation, and special skills and abilities, and who is chosen based on the relevant scientific bases (Aljughaiman et al., 2009).

4.2. Effective teacher

An effective teacher is able to differentiate levels for each student and engage all pupils through a range of educational delivery methods. They are qualified to assess students and possess the content expertise to teach. Through effective classroom management, effective teachers can foster learning environments. Additionally, they exhibit character traits that communicate their concern for students (Stronge et al., 2011).

5. Methods

5.1. Participants

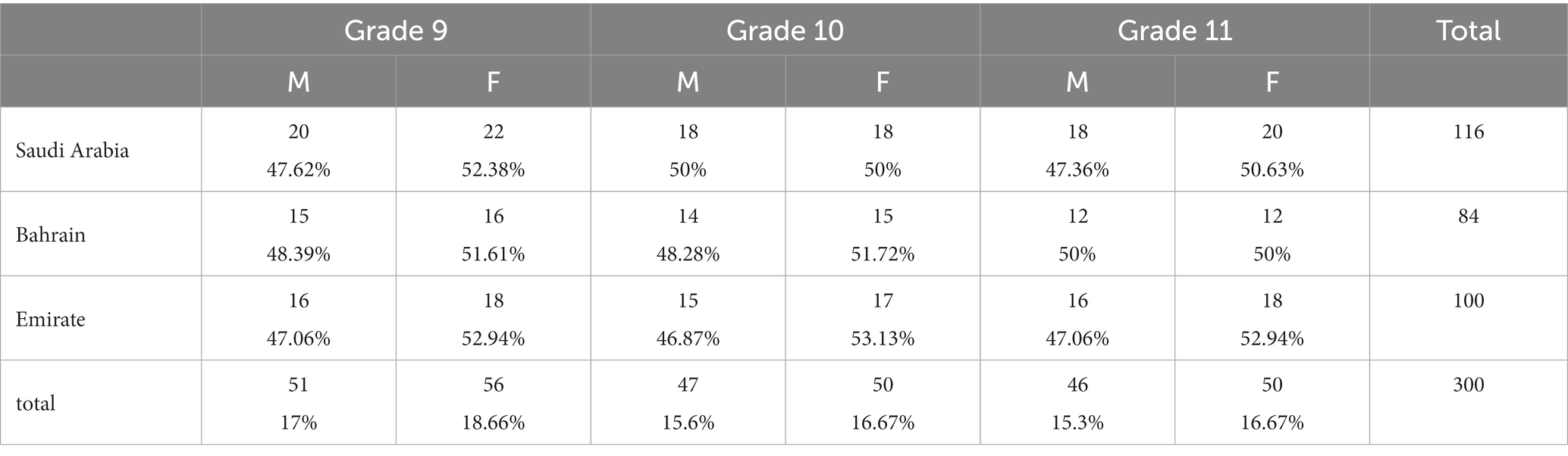

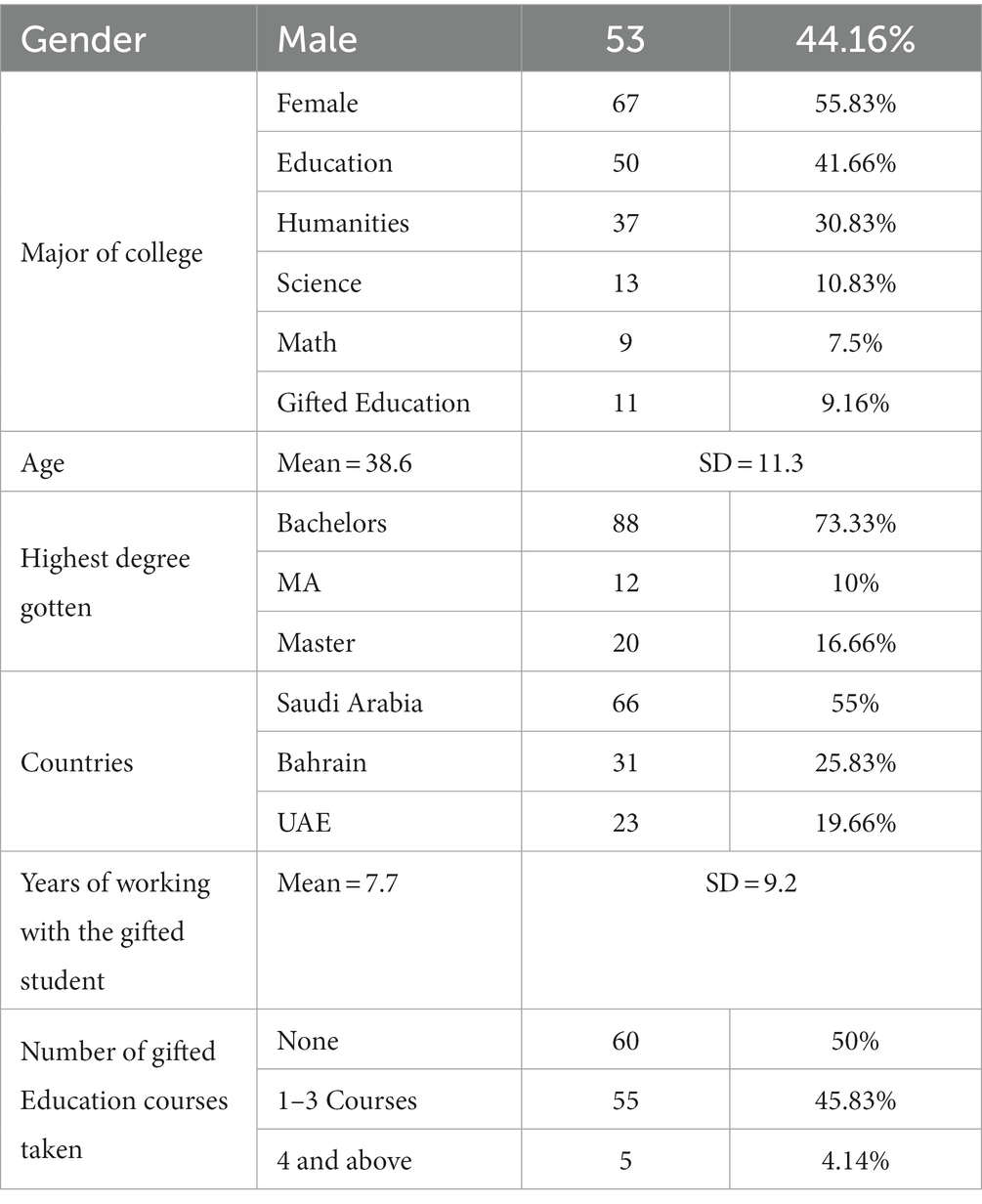

Participants were gifted students attending academically selective schools in three countries: Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the Emirate. Table 1 shows sample characteristics. This study also includes teachers who have worked in gifted schools. There was no attempt to link teachers and students in the study by design; these teachers were chosen at random from gifted students’ schools. 120 teachers were chosen at random from three countries: Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates. The average age of the teachers was 35.4 (SD = 12.0), with a range of 25–60. Male teachers accounted for roughly 44% of the teaching staff. These outstanding educators had an average of slightly over 4 years of experience teaching gifted children and over 8 years of interacting with gifted students. Half of the teachers reported having never taken a gifted education course before. Table 2 describes the demographic and background data for gifted teachers.

5.2. Instrument

Teachers of gifted students were given a questionnaire that contained some demographic and background data about themselves (gender, age, major in college, highest degree gotten, years of working with gifted students, and several gifted education courses taken). Also, teachers were asked to respond to the Preferred Teacher Characteristics Scale—Teacher Form (PICS). The amount of personal-social or cognitive-intellectual preference was assessed using the Krumboltz and Farquhar (1957) Preferred Teacher Characteristics Scale (PICS). The instrument consists of 36 items, each with two statements: one describing the personal-social behavior of the teacher and the other describing the cognitive-intellectual behavior of the teacher. The teacher form began with statements like, “I believe gifted students prefer a teacher who:” The PICS was given to the teachers who participated in this study. The teacher form’s opening line read, “I feel gifted students prefer a teacher.” Over a four-week period, the PICS authors reported a test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.88. An examination of the instrument’s internal consistency revealed a reliability coefficient of 0.90. The researcher modifies the Preferred Instructor Characteristics Scale (PICS) to Saudi in the current study. Using the KR-21 (Kuder–Richardson Formula 21) and Split-Half procedures, the study’s dependability was assessed. When there are only two possible responses to a question, the KR-21 test is applied (Hosgorur and Gecer, 2012). The investigation determined the split-half reliability coefficient, using the Spearman and Brown formula, to be 0.86 and the KR 21 value to be 0.88. The scale was first translated into Arabic by two subject matter experts with strong English skills and then separately by three English language specialists. These five academics then met to discuss any translational discrepancies and come to an agreement. In order to determine whether the items were understandable and obvious to the intended student age groups, the scale was then reviewed with 10 students (ages 14, 15, and 16). Three open-ended questions were posed to gifted students in order to gain a better understanding of their perspectives on effective teachers. The students were asked to describe in their own words the qualities that they felt made for good, effective, and ineffective teachers. The gifted students were given the following questions to answer: (1) What makes a teacher effective? (2) What professional characteristics do you believe make a teacher effective? (3) What personal characteristics do you believe make a good teacher?

5.3. Procedure

This study focused on the relationship between teachers and their students. This study looks at the personality traits, abilities, behaviors, and practices of effective teachers, namely the personal and professional characteristics that appear to be effective when applied to teaching gifted students, whether alone or in combination.

During the class time in the school’s classrooms, participants were given three open-ended questions about the characteristics of effective gifted teachers. The researcher announced the purpose of the study. The study questions took roughly 20 min to complete. Because the questions were given in class, just a few students declined to take part, resulting in a 98% response rate. Students who took part in the study were told to take as much time as they needed to complete the questions. The responses to the three questions were then gathered and scored. The questionnaire for the teachers was sent to them through email. Only 120 of the 200 teachers who were given questionnaires responded. The directors of gifted centers in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE were approached, and their permission was secured to administer the student questions and teachers’ questionnaires. In this study, teachers (n = 120) were instructed to complete the PICS, taking as much time as they believed was necessary. After that, the scales were gathered and scored. A score of zero showed a preference for the presentation of only personal-social characteristics, while a maximum score of 36 indicated a preference for the presentation of only cognitive-intellectual characteristics. The desire for demonstrated cognitive and intellectual characteristics increases with higher scores, but the preference for demonstrated personal and social characteristics increases with lower scores.

5.4. Study design

The goal of the current study was to identify the patterns of preference displayed by gifted students and their teachers in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE. To assess how gifted students rated the characteristics of their effective teachers, a second sample of gifted students from those three countries was also included. The researcher used the descriptive-analytical method to characterize the demographic information she collected from the teachers and their replies on the PICS scale, while the qualitative-analytical approach was employed to examine the open-ended questions.

5.5. Data analysis

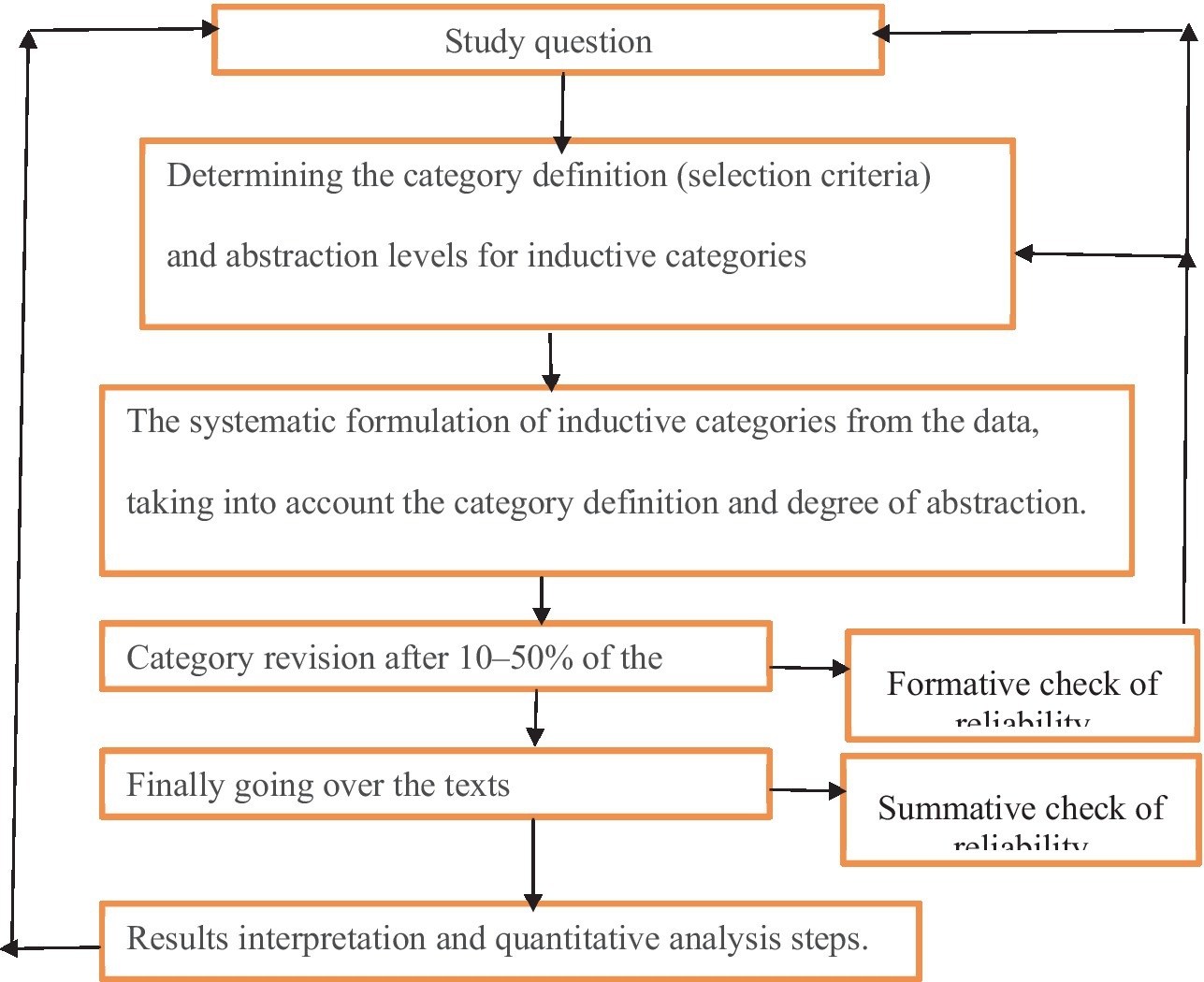

The qualitative data presented in this study paints a more nuanced picture than the quantitative data. Mayring (2000, 7th edition) inductive category construction method for systematic analysis of qualitative data was applied to the analysis of the open-ended questions. With this method, initial categories based on the study materials had to be created, and they had to be altered based on the initial interpretation of the data. The two original categories were personal and professional characteristics. The data within these broad categories was used to create inductive categories, which were then honed and reduced before being reinserted into the broad categories. The revised framework was then used to interpret the entire collection of data, as shown in Figure 1. It would be of utmost importance within the framework of qualitative methods to create the aspects of interpretation and the categories as close to the material as possible and to formulate them in terms of the material. For qualitative analyses of the three open questions, percentages of each variable were used. Using in-vivo coding to analyze the data that resulted from the open-ended questions of gifted students. In-vivo coding was used to carry out the coding process, which resulted in the creation of categories and their corresponding codes. The classical content analysis focused on content analysis and coding of certain sections of the material to analyze the collected data, followed by the compilation of similar codes into groupings. The process of coding ensured that codes were obtained in all cases, that the distinction of content between codes was carried out, and that the frequency of each code (quantitative information) was clarified. The data processing and coding process is independently worked on by two coders. The categories of responses and discrepancies were discussed in depth after completion, and after an agreement was reached, randomly selected interviews were coded by a third coder, who was generally aware of the main subject and fields of study. The degree of reliability appears to be acceptable for this study (88%).

Figure 1. Step model of inductive category development (Mayring, 1994).

The demographic information for teachers of gifted students and teachers’ responses to PICS were analyzed quantitatively. According to the variables, the numbers were counted and percentages were calculated (gender, age, major of college, highest degree gotten, years of working with gifted students, and several gifted education courses taken).

6. Results

6.1. A PICS questionnaire

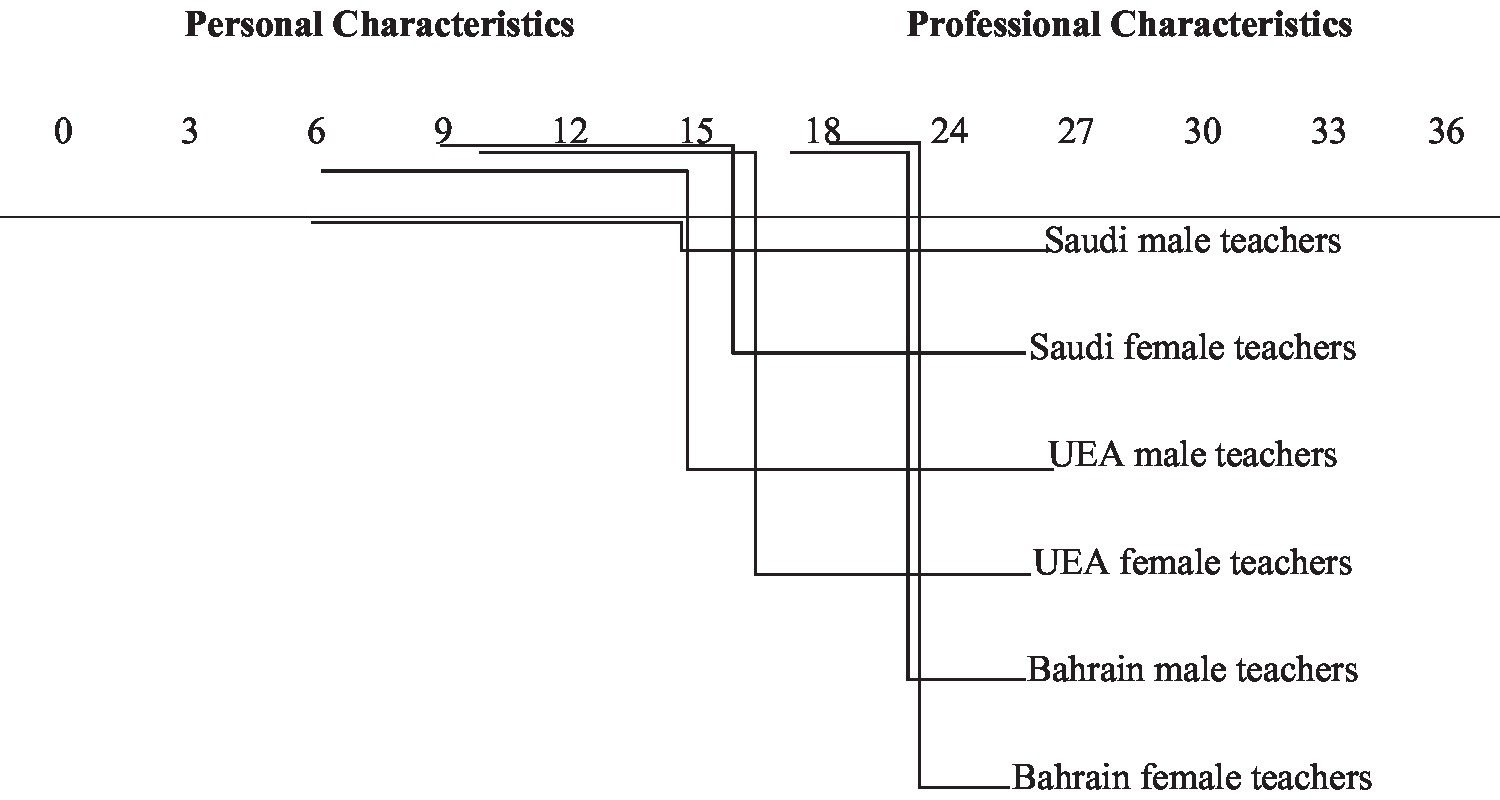

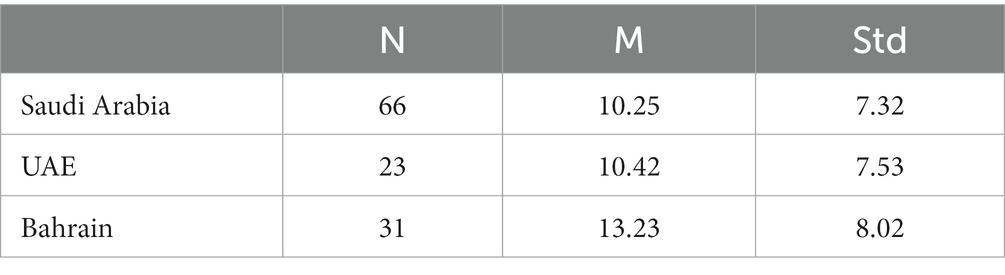

A PICS questionnaire is analyzed using a quantitative methodology. For each teacher, the 36 PICS items were totaled together, and a final score between 0 and 36 was obtained by subtracting 0 points for each personal characteristic and 1 point for each intellectual characteristic. The means and standard deviations were calculated using SPSS after the scores for each respondent were entered. As shown in Table 3, all three cohorts fall on the personal end of the continuum (Figure 2). Displayed teachers’ continuum, indicating that teachers of gifted students in these countries place a premium on personal characteristics over academic ones. The Bahrain cohort exhibited a somewhat higher mean compared to the Saudi and UAE samples, which were very similar and fell in the bottom third of the continuum.

Table 3. A comparison of means and standard deviations across three cohorts (Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain).

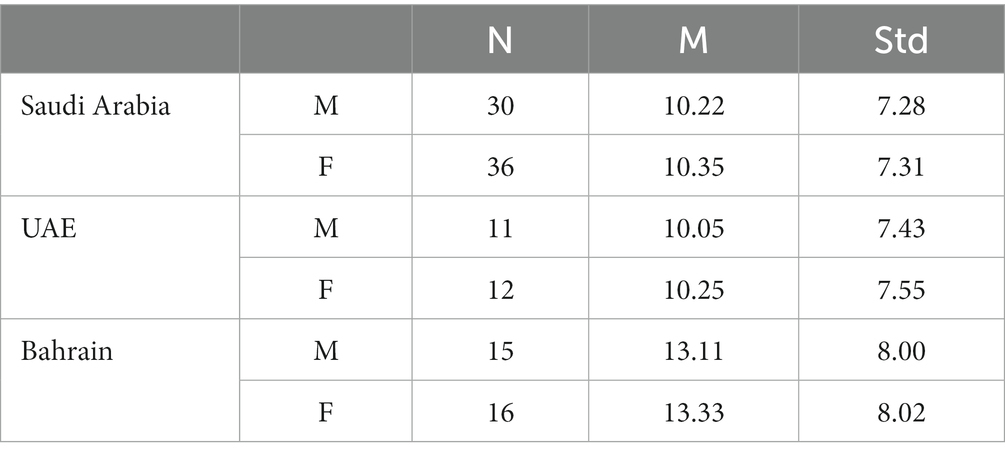

The data were subjected to an analysis of variance to see if there were gender or grade differences among the three cohorts (ANOVA). Table 4 shows that there were no gender differences in the Saudi and UAE samples, despite the fact that in both instances, female teachers had slightly higher positive attitudes regarding the personal characteristics than the male respondents. However, there was a significant difference between the genders in the Bahrain sample, with the men expressing a greater preference for personal characteristics than the women did (F = 6.336, p < 0.05).

Table 4. A comparison of means and standard deviation across three cohorts (Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain) according to teachers gender.

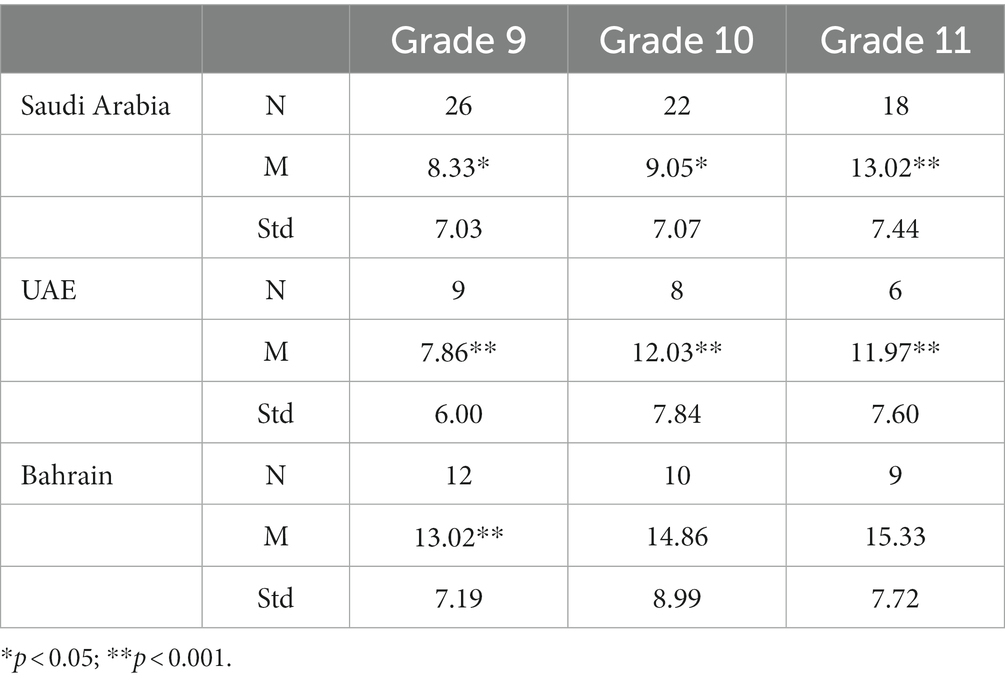

There are significant differences for each of the three cohorts in Table 5 statistics on teachers by the grade levels they teach. Despite modest variations in the patterns between the three countries, teachers who work with younger students have the propensity to value personal characteristics more than those who work with older students. Teachers of grades 9 and 10 in the Saudi Arabian sample differ considerably from one another (F = 11.013, p < 0.000). Saudi teachers who teach in grades 9 and those who teach in grades 10 and 11 differ from one another (F = 2.473, p < 0.05). Between grade 9 and grade 10 teachers, there is a significant difference in the Bahrain sample (F = 2.208, p < 0.000).

Table 5. A comparison of means and standard deviation across three cohorts (Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain) according to teachers grades.

6.1.1. What makes a teacher effective?

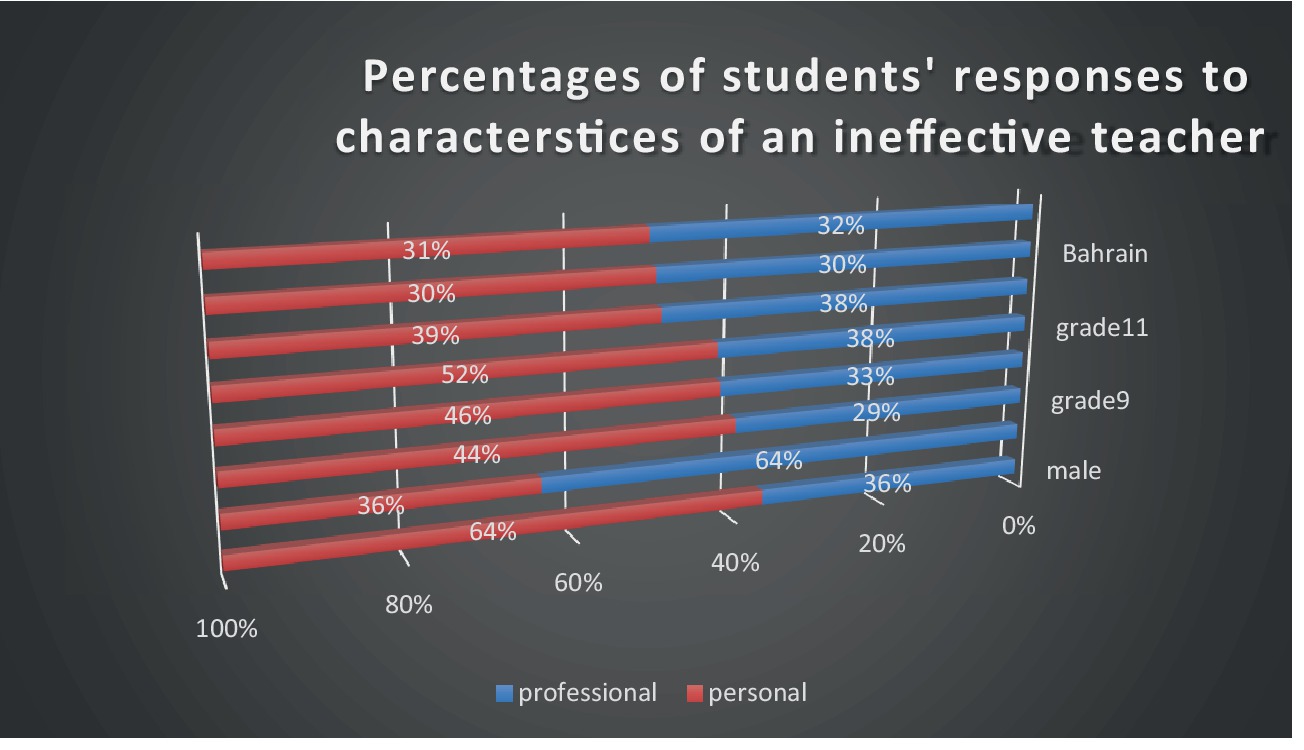

Based on the gifted students’ responses to the open-ended questions, the researcher divided the primary characteristics shown by gifted students based on the most agreeable aspects they expressed about their teachers into two categories: personal and professional. The percentages of students who responded to an effective teacher’s professional and personal characteristics are shown in Figure 3. Quick analysis of respondents’ answers to the open-ended questions to isolate the key themes It’s not unexpected that personal traits like friendliness and humor and social characteristics like listening to others and talking with them are important. However, a clear connection between the teachers’ characteristics and their subject-matter expertise is also apparent in these open-ended responses. Many of the respondents made reference to the teachers’ enthusiasm for their subjects and for teaching, and they emphasized the need for their instructors to be subject matter experts. The following comments were representative of the typical ones given by these students, who strongly preferred the personal characteristics of their teachers. As shown in Figure 3, most students’ responses regarding what characteristics they perceive their teachers should possess to be effective were personal characteristics. The percentage of responses in both the male and female groups, grade groups, as well as country groups, revealed the dominance of personal characteristics. Female-gifted students favored professional characteristics more than male-gifted students. According to the results of the question analysis, students in higher grades were more likely than their older counterparts to favor their teachers’ personal characteristics. Participants in the Saudi sample showed a slight preference for personal characteristics over those in the UAE and Bahrain, even though they had nearly equal preferences for personal and professional characteristics.

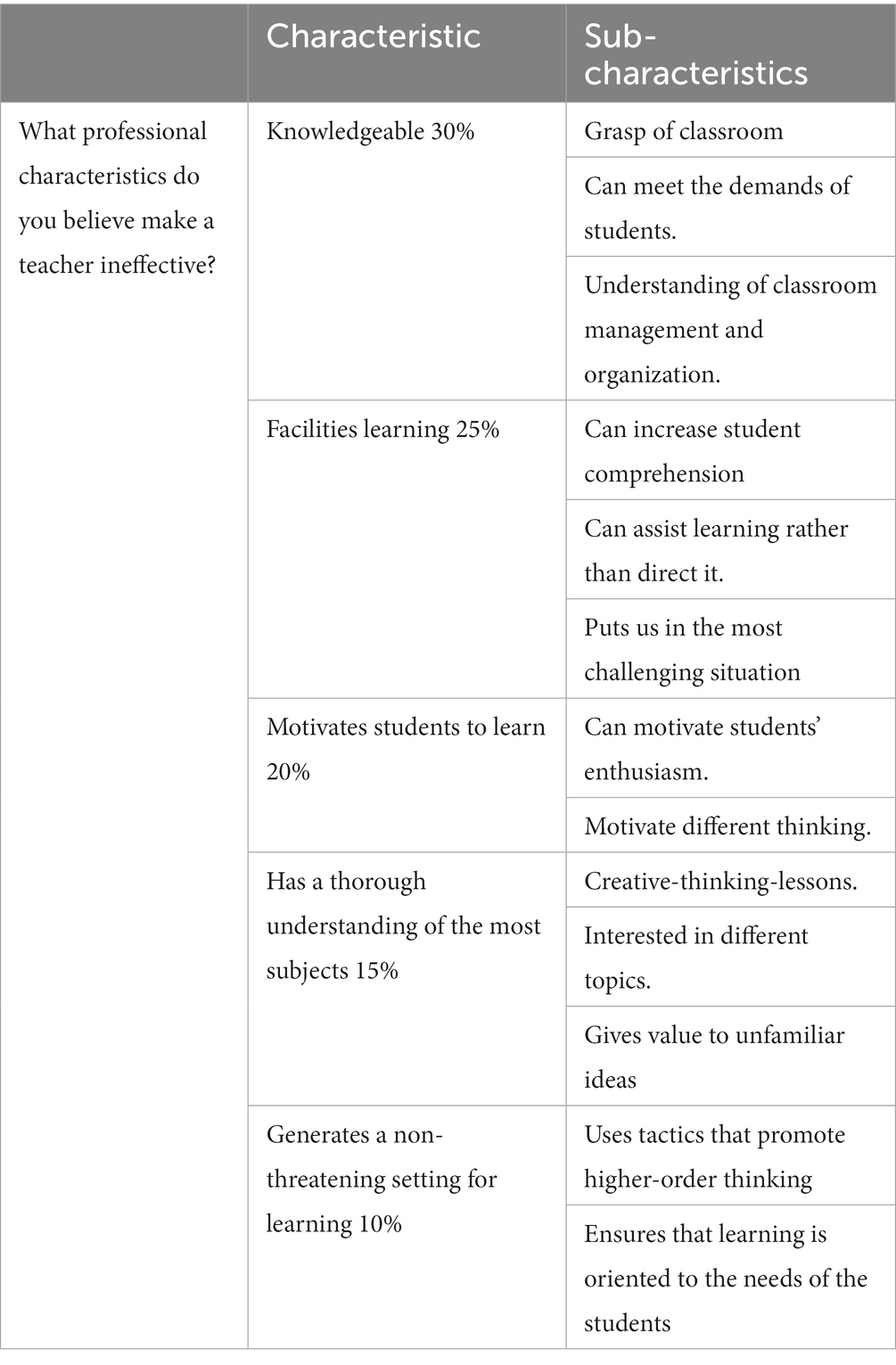

6.2. What professional characteristics do you believe make a teacher effective?

The researcher gathered the primary characteristics highlighted by gifted students as the most professional characteristics that make their teachers effective. Mayring (2000, 7th edition) inductive category construction method for systematic analysis of qualitative data was applied to the analysis of this open-ended question. The researcher next categorized the students’ answers to their teachers’ professional characteristics into particular subcategories, as shown in Table 6.

As indicated in Table 3, the perceptions of gifted students about their teachers’ effective professional characteristics were classified into five major categories. Sub-categories emerge in each category. Most of the responses regarding professional characteristics were related to the teacher’s knowledge, which included an in-depth understanding of their field and broad general knowledge, and the ability to think interdisciplinary, such as “My teacher is interested in everything.” “My teacher is a bright person.” “My teacher connects everything and makes it so simple to grasp.” “My teacher guides me through difficult things step by step.” Students’ comments about their teachers’ professional characteristics can be found in the sub-categories of knowledge, commitment to their subject, and intelligence. Most of the observations were on the teacher’s proficiency, which included an in-depth understanding of their field and broad general knowledge, and the capacity to think interdisciplinary: “My teacher was just interested in everything.” He relates everything, and he makes it so clear to understand. He teaches us the subject and then takes it a step further, making it a little easier. These remarks were frequently linked to particular remarks regarding the teacher’s dedication to their job, such as “my teacher is passionate about many topics and can make me feel the same way.” This shows why what they are teaching is vital.

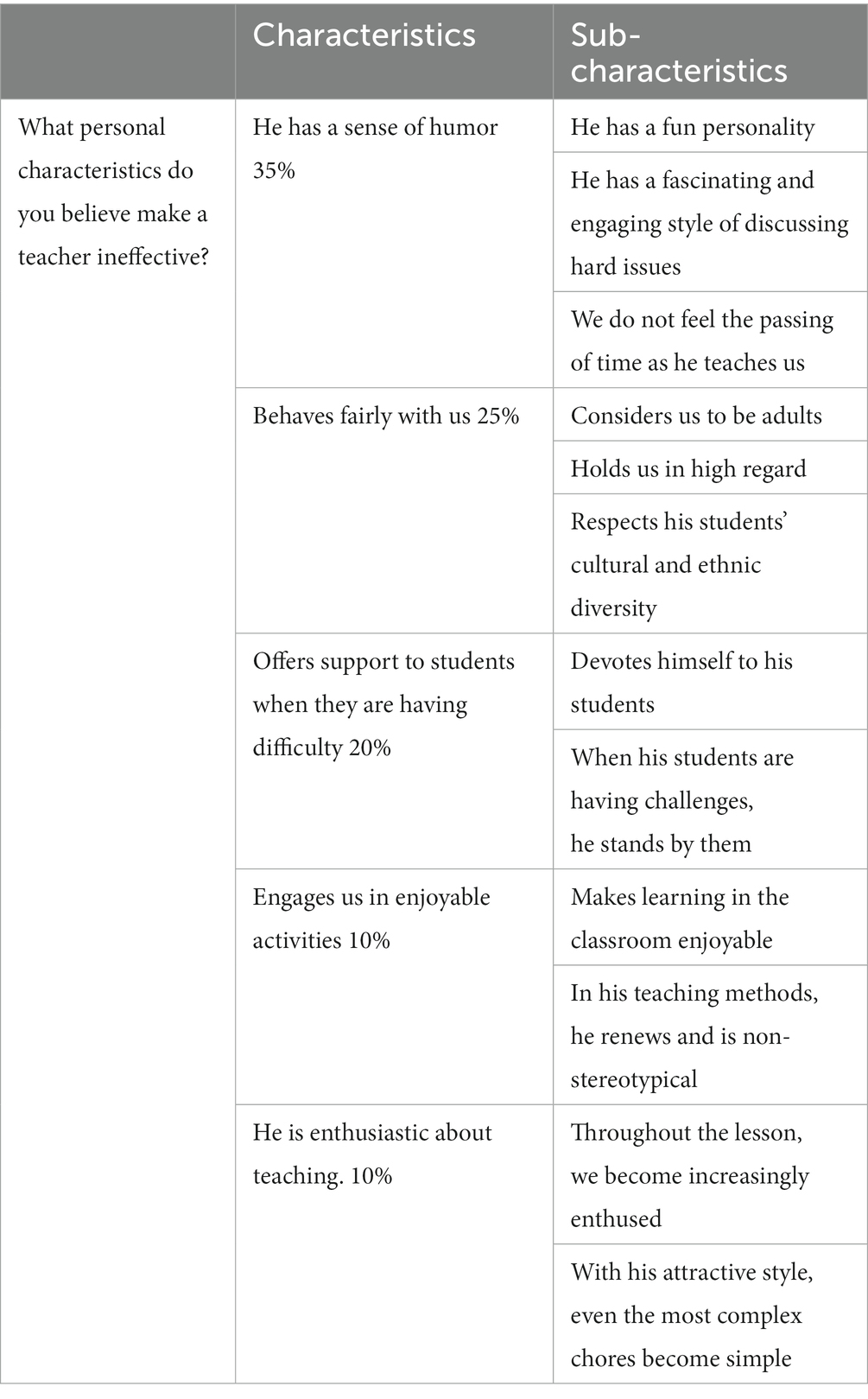

6.3. What personal characteristics do you believe make a teacher effective?

The researcher gathered the primary characteristics highlighted by gifted students as the most personal characteristics that make their teachers effective. Following that, the researcher divided the students’ responses to their teachers’ personal characteristics into subgroups, as shown in Table 7.

As shown in Table 4, there are five major categories that describe how gifted students perceive their instructors’ effective personal characteristics. Subcategories develop inside each category. Gifted students’ descriptions of the personal characteristics of effective teachers are divided into three sub-categories: interactions with students, interactions with teachers, and interpersonal skills. Most comments centered on the skills of the teachers. The findings showed that the personal characteristics of the teacher were highly regarded by the students. Among the top-notch tasks were those requiring emotional control, perseverance, compassion, politeness, humor, and social aptitude. Students’ perceptions of these characteristics of their teachers are reflected in statements like “My teacher is funny” or “My teacher is a wonderful teacher.”

Teacher-student relationships, with emphasis on the teacher’s need to understand and care about students’ needs, skills, and work; “she supports us when we face difficulties”; “he involves us in interesting activities”; “she gives energy to her students.” An effective teacher must also regard his students as mature adults, delegate authority to them, commit to their respect, treat them fairly (“he behaves us fairly”), and earn their respect. “I could learn from him”; “set an example”; “a teacher who commands respect instead of awaiting it.” Many students emphasized the importance of the teacher’s enthusiasm for their subject: “A good teacher is someone passionate about teaching their subject and assisting others to better grasp it.” Students also stressed the importance of good teachers balancing kindness and discipline without going too far in either direction. Being undesired.

7. Discussion

According to the PICS scale results (teachers’ form), gifted students in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain favored their teachers’ personal qualities over their intellectual ones. The PICS data analysis showed that teachers at different grade levels believed their students were more likely than their older counterparts to value the personal characteristics of their teachers. These findings were supported by the gifted students’ responses to the three open-ended questions that were posed to them, which revealed that they expressed a preference for the personal characteristics of their teachers. There was a significant difference because the middle school teachers’ means were different from the secondary school teachers’ means. A Scheffe test revealed that this was statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The difference between the means of the teachers of secondary school students and the teachers of middle school students caused a significant difference. This was statistically significant at the 0.01 level, according to a Scheffe test. It would seem essential that those in charge of teaching gifted students receive suitable training regarding preferred displayed teacher attributes among gifted students, given the revelations that come from an analysis of the data and the assumption that greater learning occurs when students are in a learning environment where their preferred teacher behavior is matched with the attributes of the teacher. It’s possible that the difference between what students prefer and what teachers perceive they prefer is making the learning environment in the classroom less than ideal. Notwithstanding the high level of interest among gifted students, there appears to be a substantial preference for teachers who have a personal orientation besides their professional endeavors. The information shows the need for gifted students’ teachers to be aware of this in order to achieve a balance of personal and professional traits that is more aligned with student preferences. Student preferences are used as a first step. It’s important to remember that not all gifted students share this desire. Teachers of these students should be reminded that each student will be unique and that they should try to change their conduct whenever workable to meet each student’s preferences in a situation. By recognizing and adapting to the student’s preferred learning situations, teachers should be more successful in creating the ideal learning environment for the exceptional student. The assumption of this study is that gifted students may learn more when they are instructed by a teacher who exhibits behavior that is praised by the students.

To ascertain the characteristics such teachers must have in order to remain effective, the perspectives of gifted students towards the professional and personal characteristics of their teachers were evaluated. The findings of this study can then be applied to teaching methods training and improvement for proficient teachers. What qualifies a teacher as effective, as stated by the open-ended question? When gifted students’ responses and comments to this question were analyzed, it was discovered that the majority of them focused on the teacher’s personal characteristics, which they believe contribute to his effectiveness as a teacher. From the perspectives of gifted students from different grades, genders, and regions to which they belong, professional characteristics got less emphasis. This demonstrates that gifted teenagers place greater value on the personal characteristics than the professional characteristics of their teachers. This might be the case given that teens are the age group the research is focusing on, and a study found that adolescents value people who show them trust, acceptance, respect, and understanding more highly than other age groups (Hansen and Feldhusen, 1994; Mahfouz, 2015). The results of the study showed that gifted secondary students valued their teachers’ personalities more than their intelligence and cognitive abilities. No matter the respondents’ gender or grade, this pattern persisted throughout all three cohorts—Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain. This result contrasted with Milgram (1979) results, which revealed that intellectual abilities were more highly appreciated by the gifted students. It also validated earlier studies (Vialle and Tischler, 2009).

When gifted students were asked what characteristics of a teacher they thought made them effective, the majority of their responses were arranged in frequency order. Students demonstrated a preference for teachers that engage them as active learners by utilizing a variety of pedagogical techniques. This finding is similar to Vialle and Tischler (2009) study, which found that students preferred teachers who used a range of teaching strategies to encourage them to be active learners. Many personal characteristics were highly regarded by the gifted students, who in this study believe they contribute to a teacher’s effectiveness. Personal integrity, tolerance, tenderness, friendliness, a sense of humor, and an openness to new experiences were among these characteristics. Students also indicated that effective teachers maintain a delicate balance between friendliness and strictness. This is comparable to the findings from Vialle and Tischler (2009). The study’s findings showed that females placed a higher priority on teachers’ professional characteristics than did boys. This is in line with the findings of many other studies, including (Vialle and Quigley, 2002; Su, 2006; Mahfouz, 2015). Mahfouz (2015) explains that the girls’ preference for professional characteristics is a result of their own personal traits, including motivation, self-control, and hard work. Boys’ and girls’ perceptions of effective teachers tended to place the highest value on factors related to classroom management and instructional strategies, such as those that encourage self-learning, role-play learning, unconventional or innovative teaching methods, and critical and reflective thinking.

In this study, more than 20 gifted students made statements like “My teacher is smarter than a lot of other teachers I know,” which alluded to the personality trait of “very smart,” a characteristic that indicates professional qualities. According to Vialle and Quigley (2002) study, students rate their teachers’ intellectual prowess more highly as they become more intellectually gifted.

The study’s findings indicated that boys preferred personal characteristics more than girls did. This result is comparable to Vialle and Quigley (2002). Su (2006) discovered in his research that the five most important personal characteristics of teachers for a sample of 168 Australian high school students are: competence, humor, respect, patience, and organization. These differences highlight the necessity of assessing teacher behavior and practices in the classroom for potential differences in how they may affect the learning of male and female students. A Leavitt and Geake (2009) study found a significant and favorable association between teacher personal characteristics and educational success, demonstrating that effective personal characteristics support teachers in meeting the needs of gifted students. Gifted students’ responses to an open-ended question regarding the personal traits of good teachers were analyzed qualitatively, and the results provided in-depth information about how gifted students saw teachers’ characteristics and proposed characteristics not mentioned in the earlier literature review (Su, 2006; Kornelia and Wilhelmina, 2009; Leavitt and Geake, 2009; Mahfouz, 2015; Burstow, 2018; Yasar, 2018).

The results revealed that the students’ responses to the personal characteristics of teachers lend more support to the definition of these attributes as characteristics of effective gifted teachers. Given the positive nature of most personal characteristics and the high regard with which gifted students regard their chosen teachers, there could have been a “halo” effect contributing to the gifted students’ favorable responses. To put it another way, gifted students may have attributed their characteristics to their chosen teachers because they liked them.

The study’s results also revealed that students in higher grades preferred their teachers’ personalities more often than their younger counterparts. The study’s results indicated that gifted students in all three classes preferred their teachers’ personal characteristics over those of their profession. This result is similar to that of Kornelia and Wilhelmina (2009). This result is comparable to that of Vialle and Quigley (2002) as well. An academically demanding high school in New South Wales, Australia, sent a questionnaire to students in years 7, 9, and 11, and the results revealed that the students preferred the teachers’ personal characteristics over their professional ones.

Compared to their counterparts in Bahrain and the UAE, the majority of gifted students in Saudi Arabia preferred the teachers’ personalities more. Nevertheless, most students in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE preferred the personal characteristics of their teachers over their professional ones. This may be explained by the significance of personal characteristics for students generally, as they view their teachers as role models and sources of knowledge. Many educational studies have also discussed the idea of the “hidden curriculum,” in which students are influenced by their teachers’ behavior and attempt to imitate it in most circumstances. Teachers of the gifted, in particular, have been trained to be capable of resolving the issues and challenges that their gifted students face. As a result, they possess many personal characteristics that aid in communication and interaction with their students, facilitating easier and more open learning and teaching processes. These results were consistent with many other studies, including those by Ayasra and Ismail (2013) and Al-Owaidat (2006), which found that gifted students’ personal characteristics outranked all other factors in terms of importance. According to Vialle and Quigley (2002) study, teachers’ personal and interpersonal characteristics were more beneficial to students than their intellectual or professional qualities. Additionally, the research of Vialle and Tischler (2005) revealed that all students in the countries from which the study sample was drawn (Australia, Austria, and the United States) preferred personal characteristics over intellectual characteristics in their teachers. Wilma and Vale’s study examined the most crucial qualities and desirable characteristics in teachers of gifted students.

The findings of the educational backgrounds and demographic data of the teachers showed that 89% of them have majors that are unrelated to gifted education, and 73% of them have only bachelor’s degrees. Furthermore, 50% of them did not attend any training courses. In his research, Aljughaiman et al. (2009) found that the majority of these courses concentrate on the improvement of general thinking and giftedness. The educational systems in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE fall short of international standards for preparing teachers for gifted students, despite the fact that the governments of those three countries have set aside large amounts of money for gifted education and developed a variety of approaches to enhance teachers’ professional development. For instance, Aljughaiman and Maajini (2013) found that there are insufficient methods for identifying and educating teachers of gifted students in their study about evaluating the gifted program in Saudi public education schools in light of the quality requirements of enrichment programs. Alamer (2014) also pointed out the lack of a clear policy and oversight of the selection and training of instructors. In their study on gifted education in Bahrain, Al-Mahdi et al. (2021) noticed that the majority of teachers are stressed out by their demanding schedules and inadequate salaries. Additionally, a lot of them lack experience in gifted education. In the same regard, Ismail et al. (2022) noted that although teachers of gifted students in the United Arab Emirates should possess a degree in gifted education to meet their needs, the results of this research reveal that only 9% of teachers in the sample study do. The majority of them hold degrees in humanities and general education. In the same regard, Ismail et al. (2022) noted that although teachers of gifted students in the United Arab Emirates should possess a degree in gifted education to meet their needs, the results of this research reveal that only 9% of teachers in the sample study do. The majority of them hold degrees in humanities and general education. Similar findings were reported by Aljughaiman et al. (2009) in his study, which revealed that in Saudi Arabia, half of the teachers had bachelor’s degrees in scientific disciplines unrelated to gifted education. Mills (2003) pointed out that formal training and certification in gifted and talented education may not be the only factors to consider when choosing teachers for gifted students. Selecting teachers who are passionate about the subject matter as well as those with substantial experience in the academic field being taught may be equally crucial.

8. Conclusion

Because gifted students are different from other students, it is important to carefully select their teachers to give them the best educational opportunities. A lot of studies have been conducted on how to create effective teachers. It is essential to identify the characteristics that make teachers effective in order to implement extensive training before beginning a career as a teacher and to continue to enhance their professional activities while keeping in mind that the emphasis is on ongoing teacher training. When teachers know how to engage gifted students, many school issues—including absenteeism, violence, and dropout rates—are diminished.

According to this study, gifted students value their teachers’ personal characteristics more than their professional ones. An examination of teachers’ responses to a PICS scale that reveals their preferences for the intellectual and interpersonal traits that their students appreciate in their effective teachers lends weight to this conclusion. A crucial component of teacher training for working with gifted students is understanding how effective teachers are seen by their students. The main finding of this study is that teachers can be trained to be more successful practitioners with gifted students by focusing on the development of positive attitudes and interpersonal skills. Despite several studies on the impact of teacher preferences on learning using the general student population, there has not been much research on employing gifted students. The next step for researchers should be to discover whether or not student preferences have an impact on learning among gifted students. This problem needs to be solved if educators are to better meet the requirements of gifted students.

9. Limitation

While the students’ perceptions of their teachers’ characteristics are significant, they are insufficient to support conclusions about what teachers should or are capable of doing. Hence, limitations should be set while employing study results.

Author’s note

YA is an Assist. Prof. Dr. at Damascus University (2007–2010). Then Assoc. Prof at The National Research Center for Giftedness and Creativity at King Faisal University (2010- now) she received M.A. Degree at American University of Beirut on evaluation and assessment, PhD on evaluation and assessment in Damascus University. She is consult in the National Center for Assessment and Evaluation. Her major areas of research are evaluation and assessment, gifted education, differentiated instruction, and teacher and learner development. She has published articles in international journals on these areas. She has developed many test and scales such as to Saudi environment such as: CogAt5, SAGES-2, GRS-S, and GCAT.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, for financial support under annual research grant number GRANT3,253.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aboud, Y. (2020). Obstacles to creative teaching from the perspectives of faculty members at King Faisal University in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 3, 531–562.

Alamer, S. A. (2014). Challenges facing gifted students in Saudi Arabia. Res. Humanit. Soc. 4, 142–145.

Alamiri, F. Y. (2020). Gifted education in Saudi Arabian educational context: a systematic review. J Arts Humanit 9, 78–89. doi: 10.18533/journal.v9i1.1809

Al-Anzi, A. (2006). The impact of a training program based on mind habits on the development of productive thinking skills for both the fifth elementary grade and first intermediate grade students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Psychol Educ Sci 9, 763–828.

Aljughaiman, A. (2010). The Gifted Program in Public Education Schools, General Administration for the Gifted. The King Abdul-Aziz and His Companions Foundation Pub, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Aljughaiman, A., Ayoub, A., Maajeeny, O., Abuoaf, T., Abunaser, F., and Banajah, S. (2009). Evaluating Gifted Enrichment Program in Schools in Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: Ministry of Education.

Aljughaiman, A., and Maajini, O. (2013). Evaluating the gifted program in Saudi public education schools in light of the quality standards of enrichment programs. J Educ Psychol Sci 14, 22–45.

Aljughaiman, A., Nofal, M., and Hein, S. (2016). “Gifted education in Saudi Arabia: A review,” in Gifted Education in Asia: Problems and Prospects. eds. D. Y. Dai and C. C. Kuo (Charlotte: IAP Information Age Publishing, Inc.) 191–212.

Al-Mahdi, O., Yaakub, A. B., and Abouzeid, A. (2021). Gifted education: perspectives and practices of school principals in Bahrain. Int J Eval Res Educ 10, 576–587. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v10i2.21176

Al-Owaidat, F. (2006). Building a List of Professional and Social Competencies and Personal Characteristics of Teachers of Gifted Students. Master Thesis. Amman Arab University for Graduate Studies.

Ayasra, S., and Ismail, N. (2013). Characteristics and dimensions of teachers of gifted and talented students from the point of view of students in schools for the gifted and talented in Jordan. Arab J Dev Excell 7, 93–121.

Benbow, C. P., and Stanley, J. (1996). Inequity in equity: how "equity" can lead to inequity for high-potential students. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2, 249–292. doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.2.2.249

Berliner, D. C. (1986). Learning about and learning from expert teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 35, 463–482. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00004-6

Berliner, D. C. (2006). Our impoverished view of educational research. Teach. Coll. Rec. 108, 949–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00682.x

Burstow, B. (2018). “Professional learning development from the top-down: Identifying the need,” in Effective Teacher Development: Theory and Practice in Professional Learning (London: Bloomsbury Academic), 31–46. Retrieved April 22, 2023, from http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474231893.ch-003

Chae, Y., and Gentry, M. (2011). Gifted and general high school students’ perceptions of learning and motivational constructs in Korea and the United States. High Abil. Stud. 22, 103–118. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2011.577275

Colangelo, N., and Davis, G. A. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of Gifted Education. 416–434. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Cooper, P., and McIntyre, D. (1996). Effective Teaching and Learning: Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Education and Training Evaluation Commission. (2022). Gifted Teachers’ Standards. Available at: https://www.etec.gov.sa/en/Pages/default.aspx. (Accessed October 15, 2022).

Ferrell, B., Kress, M., and Croft, J. (1988). Teachers of gifted children: characteristics of teachers in a full day gifted program. Roeper Rev. 10, 136–139. doi: 10.1080/02783198809553108

Gagné, F. (2003). “Transforming gifts into talents: the DMGT as a developmental theory” in Handbook of Gifted Education. eds. N. Colangelo and G. A. Davis 3rd ed (Boston: Allyn & Bacon), 60–74.

Gargani, J., and Strong, M. (2014). Can we identify a successful teacher better, faster, and cheaper? Evidence for innovating teacher observation systems. J. Teach. Educ. 65, 389–401. doi: 10.1177/0022487114542519

Goldstein, H. (2003). “Multilevel modeling of educational data” in Methodology and Epistemology of Multilevel Analysis. ed. D. Courgeau (London: Kluwer)

Gross, M. U. M. (1999). Inequity: the paradox of gifted education in Australia. Aust. J. Educ. 43, 87–103. doi: 10.1177/000494419904300107

Hansen, J. B., and Feldhusen, J. F. (1994). Comparison of trained and untrained teachers of a gifted student. Gifted Child Q 38, 115–121. doi: 10.1177/001698629403800304

Hosgorur, T., and Gecer, A. (2012). Gifted students’ views about teachers’ desired characteristics. Educ Process Int J 1, 39–49. doi: 10.12973/edupij.2012.112.4

Ismail, S. A. A., Alghawi, M. A., and AlSuwaidi, K. A. (2022). Gifted education in United Arab Emirates: analyses from a learning-resource perspective. Cogent Educ 9:1. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2034247

Kornelia, T., and Wilhelmina, V. J. (2009). Gifted students’ perceptions of the characteristics of effective teachers. 115–124.

Krumboltz, J., and Farquhar, W. (1957). The effect of three teaching methods on achievement and motivational outcomes in a how-to-study course. Psychol. Monogr. 71, 1–26.

Leavitt, M., and Geake, J. (2009). Giftedness perceptions and practices of teachers in Lithuania. Gifted Talented Int 24, 139–148. doi: 10.1080/15332276.2009.11673536

Lupascua, A. R., Pânisoarăa, G., and Pânisoarăa, I. (2014). Characteristics of effective teacher. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 127, 534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.305

Mahfouz, (2015). The necessary competencies for teachers of gifted students in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia from the student's point of view. Glob Inst Stud Res J 1, 1–19.

Mayring, P. H. (1994). “Qualitative Ansätze in der Krankheitsbe wältigungs forschung” in Krankheitsverarbeitung. Jahrbuch der Medizinischen Psychologie. eds. E. Heim and M. Perrez, vol. 10 (Göttingen: Hogrefe), 38–48.

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 1:20.

Mills, C. J. (2003). Effective teachers of the gifted student. Gifted Child Q 47, 272–281. doi: 10.1177/001698620304700404

Milgram, R. M. (1979). Perception of teacher behavior in gifted and non-gifted children. J. Educ. Psychol. 71, 125–128.

Renzulli, J. S. (1968). Identifying key features in programs for the gifted. Except. Child. 35, 217–221. doi: 10.1177/001440296803500303

Rimm, S. B. (1997). Underachievement Syndrome: Causes and Cures. Watertown, WI: Apple Publishing Co.

Şahin, F., and Çetinkaya, Ç. (2015). An investigation of the effectiveness and efficiency of classroom teachers in the identification of gifted students. Turk J Giftedness Educ 5, 133–146.

Stronge, J. H., Ward, T. J., and Grant, L. W. (2011). What makes good teachers good? A cross-case analysis of the connection between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. J. Teach. Educ. 62, 339–355. doi: 10.1177/0022487111404241

Su, Y. H. (2006). Exploring Gifted Primary Students' Perceptions of the Characteristics of their Effective Teachers. Master Dissertation, University of New South Wales.

The Arab Center for Educational Research for the Gulf States. (2020). Gifted Nurturing: A Survey Study of the Most Prominent Global Trends and Experiences in the Member States of the Arab Bureau of Education for the Gulf States. Kuwait: The Arab Center for Educational Research for the Gulf States.

Tomlinson, S. (1998). “Chapter 12: a tale of one school in one city: hackney downs” in School Effectiveness for Whom? eds. R. Slee and G. Weiner (London: Falmer Press), 156–169.

Vialle, W., and Quigley, S. (2002). Does the teacher of the gifted need to be gifted? Gifted Talented Int 17, 85–90. doi: 10.1080/15332276.2002.11672992

Vialle, W., and Tischler, K. (2005). Teachers of the gifted: a comparison of students’ perspectives in Australia, Austria and the United States. Gift. Educ. Int. 19, 173–181. doi: 10.1177/026142940501900210

Vialle, W., and Tischler, K. (2009). “Gifted students’ perceptions of the characteristics of effective teachers” in The Gifted Challenge: Challenging the Gifted. ed. D. Wood (Merrylands, Australia: NSWAGTC Inc), 115–124.

Whitton, D. (1997). Regular classroom practices with gifted students in grades 3 and 4 in New South Wales, Australia. Gifted Educ Int 12, 34–38. doi: 10.1177/026142949701200107

Worrell, F. C., Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., and Dixson, D. D. (2019). Gifted students. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 551–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102846

Keywords: gifted, effectiveness, professional characteristics, personal characteristics, gifted students’ teachers

Citation: Aboud YZ (2023) Evaluating gifted students’ perceptions of the characteristics of their effective teachers. Front. Educ. 8:1088674. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1088674

Edited by:

Manpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, IndiaReviewed by:

Ariel Mariah Lindorff, University of Oxford, United KingdomWahyu Hidayat, Institut Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Siliwangi, Indonesia

Copyright © 2023 Aboud. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yusra Zaki Aboud, eW96YWtpQGtmdS5lZHUuc2E=

Yusra Zaki Aboud

Yusra Zaki Aboud