94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 07 July 2023

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1081143

This article is part of the Research TopicTowards 2030: Sustainable Development Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities. An Educational PerspectiveView all 4 articles

This study explored 141 Korean immigrant parents’ use of local libraries to enhance their families’ social and cultural capital and adjust to the host country. We searched resources in Korean, and multicultural programs planned for the public and immigrants, Asian immigrants in particular, at three libraries before COVID-19 and at two libraries during COVID-19. Parents reported dissatisfaction with library services because of language barriers (38%) and the lack of Korean resources (38%) and cultural programs (25%). Except for 18 books and 24 e-resources, no library resources in Korean were published after 2008. At Branches B and C, before COVID-19, only one multicultural program was offered for children. During COVID-19, hate crimes against Asians increased by 77%. However, at Branches B and C, the number of adult programs related to Asian culture decreased to 0% from 6% and increased to 3% from 0%, respectively, during COVID-19. The respondents’ concerns about the lack of programs supporting their adjustment and fostering multicultural dialog were validated.

From an ecological perspective, the availability of books and programs at local libraries may influence parents’ decisions to regularly borrow books and participate in organized library programs to enhance their own and their children’s learning. Spaces or contexts created by the community influence parents’ construction of their roles (e.g., go to the library with their children); rules for participation (e.g., how often); utilization of tools and artifacts for participation (e.g., library books and programs); and involvement with other individuals and communities (Barton et al., 2004).

Even though local libraries are one of the most easily available and accessible community organizations for immigrant families to seek support, little is known about the ways in which immigrant parents use local libraries to enhance both their children’s learning and their own learning. According to Burke (2008), members of the Latinx community consider the library a “neutral ground” (p. 165), where even undocumented immigrants can seek assistance for themselves and their children. Results of Su and Conaway’s (1995) study showed that the most common reason for Chinese immigrant adults to use libraries is to read and borrow books and that the most common reason for Korean immigrants is to use quiet study areas.

Our failure to find more recent data on ways that immigrant communities use local libraries to enhance their social and cultural capital and to become involved in their children’s learning highlighted the need for this research, the results of which might help libraries to improve their resources and programs to support the learning of all community members, including minorities. Bourdieu (1986) defined social capital as the economic resources gained from being part of a network of social relationships, including group membership, and cultural capital as the noneconomic resources that support social mobility (i.e., knowledge, skills, and education).

Current data, along with data from the 1990s, have shown that minorities actively use resources such as books and programs that are available at their local libraries. Metoyer-Duran (1991) reported that the use of public libraries by Chinese and Korean communities in California reached 83 and 79%, respectively, in the early 1990s. In 2002, 40% of minority families used public libraries or bookmobiles; this percentage was slightly higher than the 39% of European American households (Glander and Dam, 2006). Among minorities, 34% of people from East Asia and 45% of people from South Asia used public libraries in the last month of when the survey was administered (as cited in Burke, 2008). The most recent federal statistics report on public libraries was in 2012 (American Library Association, 2015), but we could not locate data on public library use by race.

As libraries have evolved from providing facilities to offering services to keep up with social demands, they have developed programs to leverage the cultural capital of immigrants by offering English as a second language (ESL) and citizenship classes (Thomas et al., 2016). However, little is known about whether and how immigrant families take advantage of these library services to support their own as well as their children’s learning. In our study, immigrants were defined as ethnic or race minorities who crossed international borders with the intention of living in the host countries (Polese, 2017), and minorities were defined as population subgroups with ethnic or racial characteristics distinctive from those of the majority of the population (American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology, n.d.). The American Library Association Public Programs Office (2018) defined a program as “an intentional service or event in a social setting, developed proactively to meet the needs or interests of an anticipated target audience” (p. 1).

We studied Korean immigrant parents’ perceptions of the ways that local libraries satisfied their own and their children’s needs based on several perspectives. First, when parents educate themselves, self-efficacy in supporting their own and their children’s learning may be enhanced (López et al., 2001; Rah et al., 2009). Costigan and Koryzma (2011) defined efficacy as confidence, effort, and persistence in completing tasks. Pryor (2001) noted that immigrant parents show efficacy in their own learning and want to gain access to cultural and recreational opportunities, mentoring programs, programs in the parents’ native language, and support from community volunteers. Pryor also shared that immigrant parents want opportunities to tell their stories, honor their cultural traditions, and learn about and celebrate other cultures.

Second, even though immigrants continue to face a multitude of barriers, including linguistic and cultural differences, keeping their own “culture and language are topics of great interest and concern” to minority families (Gaetano, 2007, p. 160). The ways that one’s language is preferred and promoted in public domains impact the perceptions of children and their parents about the desirability of their heritage language (Reese and Goldenberg, 2006). Having library resources and programs available in languages other than English may signal the existence of a just society premised on multilingualism, not monolingualism (Reese and Goldenberg, 2006), and diversity rather than White domination (Lei and Guo, 2022).

According to the websites of the libraries where we conducted our study, all three public library systems stated that one of their responsibilities was to support resources honoring the cultures in their communities. Libraries showed their commitment to serve “as a cultural and intellectual center that enriches the community and empower all residents” (County C Public Library, n.d.); provide “equal access, customer-friendly access” (County B Library System, n.d.); and “offer a broad range of resources responsive to the diverse and changing needs of our community” (County A Public Library, n.d.).

However, in North America, suburbs were designed to segregate land use by socioeconomic status, so libraries have not been used adequately to accommodate the needs of diverse populations (Zhuang et al., 2021). This challenge has been intensified because in 2011, 61% of immigrants settled in suburban and small metropolitan areas rather than in cities, meaning that suburbanization has increased racial, ethnic, and linguistic disparities in using public community resources (Singer and Wilson, 2011). In this context, we studied the perspectives of Korean immigrant parents residing in suburbs about library resources and programs. In addition, to triangulate the participants’ perspectives, we searched local library resources in Korean and programs that were developed to support immigrants’ adjustment to the host country and foster multiculturalism in the communities. Polese (2017) defined a multicultural program as a program that “recognizes, manages and maximizes the benefits of cultural diversity” (p. 156). We focused our research specifically on race/ethnic diversity.

Public libraries often offer programs that involve “ordinary” (Audunson et al., 2018, p. 780) rather than diverse populations and make libraries highly intensive meeting places (e.g., mystery book clubs or poetry writing classes) where the hegemonic social order can be maintained (Aptekar, 2019). According to Audunson (2005), high-intensive meeting places allow people to gather according to their own beliefs and interests, whereas low-intensive meeting places allow people from different backgrounds to communicate and share various values, beliefs, and ideologies. In the world of digitization, it is somewhat easier to find high-intensive meeting places that result in fragmentation. In this context, it was important to study the nature and status of multicultural programs offered by local libraries to gauge whether the libraries were striving to become low-intensive meeting places.

The benefit of low-intensive meeting places is that through community-organized programs at libraries, immigrants have opportunities to share their languages, cultures, and multiple ways of knowing (Lei and Guo, 2022) with the dominant group, thus allowing immigrants and librarians to challenge mainstream society’s deficit perspectives about minority cultures (Garcia and Stein, 1997; Tett, 2001). When culturally responsive librarians take the time to investigate alternative resources and books, they offer critical-thinking skills and multiple cultural perspectives to citizens. Critical-thinking skills gained from learning diverse perspectives empower citizens to be culturally competent individuals and improve their self-efficacy in decision making toward establishing a more equitable society.

While we were conducting our research, the COVID-19 pandemic started in early 2020. The challenges that immigrant communities in the suburbs face, such as unequal access to public places, were exacerbated by the pandemic (Zhuang et al., 2021). Not all local libraries were ready to support their users through virtual media. In addition, the libraries had to have staff work remotely (Welsh et al., 2021). The forced shift to an online presence might have been more challenging for language-minority communities to access information and library services because of social isolation and physical separation perpetuated by racial discrimination (Wang, 2021). As a result, immigrants speaking different languages lost opportunities for social interactions, community bonding, and access to essential services (Zhuang et al., 2021).

This abrupt social change caused by COVID-19 gave us an additional opportunity to research ways that local library systems responded to the urgent need of Asian American communities to counter the problematic representations of Asian as carriers of the Chinese virus (Kimura, 2021). Therefore, we decided to study the libraries’ multicultural programs planned for the general public and immigrants, Asian immigrants in particular, again in 2021.

Even though library programs are perceived as a mechanism for generating social and cultural capital (Vårheim, 2011; Aptekar, 2019), libraries also continue to be viewed as highly intensive meeting places (Audunson, 2005; Audunson et al., 2018) where disparities and inequalities among community members exist in terms of accessing library materials and services (Singer and Wilson, 2011). Based on these reciprocal perspectives, we investigated the awareness and use of library services by Korean immigrant parents, their need for library resources and programs to enhance the parents’ own and their children’s social and cultural capital, and the provision of available library resources and multicultural programs to surrounding communities.

The study was guided by four research questions (RQs):

1. What are the ways Korean immigrant parents use libraries to support their own needs and their children’s learning?

2. If the Korean immigrant parents do not take advantage of library services and programs, what are the reasons?

3. What resources and programs did the libraries offer to support immigrants’ needs and multiculturalism in the community before and during COVID-19?

4. What future programs/services Korean immigrant parents would like to see provided by the libraries?

We investigated the experiences with and expectations of library services of a sample of Korean immigrant parents using a questionnaire. The participants were Korean immigrant parents living in a metropolitan area in a southeastern U.S. state that has the sixth largest group of Korean-born immigrants in the country (Migration Policy Institute, n.d.). We referred to the state as State A. We distributed the survey to three local Korean American churches that were operating nonprofit summer camps for students in preschool to Grade 11. The camp counselors asked the participating students to deliver the questionnaire to their parents, and they also gathered the returned questionnaires. The first page of the questionnaire solicited written consent and had a section where the respondents could ask questions related to the survey. To accommodate the various ways that the respondents asked questions, we provided our emails and telephone numbers to them. The total number of returned questionnaires was 168 (27% response rate). After excluding missing responses, 141 completed questionnaires were used in the data analysis.

In addition to gathering the parents’ responses to the questionnaire, in a way to triangulate the Korean immigrant parents’ experiences with library services, we searched library books and digital media presented in Korean in three library systems in each of three counties where the highest Korean population reside. We also collected data on the number and nature of multicultural programs to gauge ways that the libraries promoted the inclusion of minority communities by celebrating minority communities’ heritages and/or languages and responding to meet the needs of immigrant communities. Particular attention was given to ways that the libraries responded to the needs of Asian immigrant populations during COVID-19, when ethnic tensions and anti-Asian racism were evident. Because the number of times that programs are offered may denote their importance, we studied the number of multicultural programs offered and also considered their frequency.

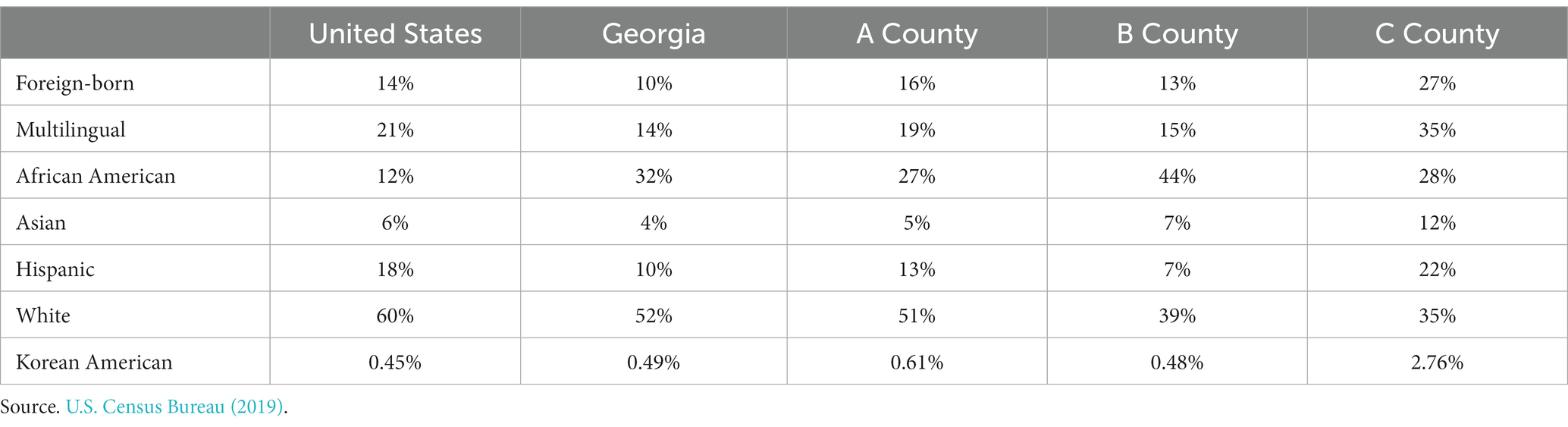

The report from the U.S. Census Bureau (2019) indicated that the demographics of the three counties that our study targeted were more diverse than the average demographics in the United States and State A in terms of foreign born (16, 13, and 27% in Counties A, B, and C, respectively, compared to 14% in the United States and 10% in State A); multilingual (19, 15, and 35% in Counties A, B, and C, respectively, compared to 21% in the United States and 14% in State A); and Korean American status (0.61, 0.48, and 2.76% in Counties A, B, and C, respectively, compared to 0.45% in the United States and 0.49% in State A; see Table 1).

Table 1. Percentages of foreign born, multilingual, and Korean American Residents in Counties A, B, and C.

Phase 1 of data collection included having the participants complete the survey and our own efforts to search the library resources and programs that were available from January to April 2018, referred to as “before COVID-19.” Phase 2 of data collection involved searching for available resources and programs at the libraries from January to April 2021, referred to as “during COVID-19.” During Phase 2, the libraries offered programs entirely online. By January 31, 2020, the libraries stopped offering face-to-face programs in response to COVID-19. By May 5, 2020, the libraries were offering nothing but virtual programs. In the case of County B, the first phase of onsite services began on May 4, 2021, with full reopening on June 1, 2021 (County B Library System, 2021). In the case of County C, the first phase of reopening began on May 1, 2021, with full reopening on August 9, 2021 (County C Public Library, 2021).

The questionnaire asked the participants about the current use of library resources and programs by themselves and their children, along with their and their children’s need for library resources and programs. We developed the survey questions based on literature reviews and our personal lived experiences of using community libraries as Korean American immigrants with our own children. The second author of the manuscript and her colleague, who worked for a community library validated the questionnaire. In addition to asking the participants for demographic information such as mothers’ working status, mothers’ level of education, marital status, income level, number of children, children’s genders, types of children’s education, years in the United States, immigration status, and their children’s grade levels, we asked six closed questions and two open-ended questions. The first open-ended question inquired about the Korean immigrant parents’ awareness of resources and programs provided by the local libraries. The second one asked them to identify resources and programs that should be provided by the local libraries to meet their needs. Followings are the closed questions that we asked.

1. How often did you spend time with your child at home/outside/library, respectively, for the last 1 year? This question was separated into three independent questions asking how often they spent time (a) at home, (b) outside, and (c) at the library. There were six response options (0 = never, 1 = 1–2 times/year, 2 = 4–5 times/year, 3 = a few times/month, 4 = a few times/week, 5 = everyday).

2. What type of library did you use the most? This question had four response options (1 = county public library, 2 = child’s school media center, 3 = college library, 4 = other).

3. Which county public libraries did you use the most? This question had five response options, with the surrounding county name coded 1 to 5.

4. Do you think the public libraries provide programs for immigrant families? This question had three response options (1 = not sure, 2 = no, 3 = yes)

5. What were the purpose(s) of using libraries? This question had five response options (1 = use of library resources for children, 2 = use of study space, 3 = computer usage, 4 = use of programs, 5 = use of library resources for myself).

6. If you were uncomfortable or unsatisfied using a library, what were those reasons? This question had five response options (1 = language barriers, 2 = difficulty using the library, 3 = unsatisfactory service by library staff, 4 = lack of Korean resources, and 5 = lack of cultural programs). For the last two questions, the participants could provide multiple answers.

We searched books and digital media materials in Korean at all branch libraries in the three counties, identified as County A, County B, and County C library systems, because books are available through interlibrary loans. However, we selected one branch library in each county located in a city where the Korean immigrant population was larger because programs had been scheduled for face-to-face formats before COVID-19, so these branches were more likely to attract Korean immigrants. We referred to these libraries as Branch A, B, and C, respectively. However, during COVID-19, from May 2020 to May 2021, the programs offered by all branch libraries under each county library system were the same because the branches shared the same virtual programs offered by their counties. In the rest of the manuscript, when we refer to programs at Branch B or Branch C during COVID-19, the wording is synonymous to ones at County B or County C.

Because Branch A had programs scheduled only for the next 4 months (i.e., January–April) in 2018, and because library programs were sensitive to celebrating national holidays and special events each month, for consistency, we searched all programs available for the same 4-month period in 2021. Even though we could secure library program data from the archives of the County B library system website and from our collaborations with a librarian in County C, we could not secure data from the County A library system because of their unavailability resulting from the county library’s web system being updated in 2021 (personal communication, November 16, 2021). Therefore, we could research library program data from only two county library systems during COVID-19.

Using the provided filters that each county library system used, we were able to apply the same search protocol to all three library systems. Books and digital media were searched by four criteria: format (book vs. digital media), language type (i.e., Korean vs. Others), age (i.e., adult vs. juvenile), and publication year (i.e., 1980–2008 vs. 2009 and beyond). The age-level filters comprised only adult and juvenile subfilters at the County A and B library systems and appeared to include children’s materials as juvenile subfilters. Following the county library systems’ classification protocols, digital media included video discs, audio discs, electronic resources, e-books, e-audiobooks, audio cassettes, sound recordings, video cassettes, visual materials, e-videos, and music.

From the Calendar tab on the home page of the target counties’ library systems, we used the filters of venue (i.e., selecting a branch library), event category (i.e., children and adults), and event dates (e.g., January 1–April 30). The Institute of Museum and Library Services (2018a) defined children as individuals 11 years of age and under and adults as individuals 19 years of age and older. Because programs for young adults (i.e., adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age) represent only 10% of all programs offered by public libraries in the United States (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2018a), as was the case for the local libraries that we searched, we studied only children’s and adults’ programs. We did not consider curbside pick-up service as a program because it did not satisfy the definition of a program, “an intentional service or event in a social setting, … not [in an] individual [setting]” (American Library Association Public Programs Office, 2018, p. 1). During COVID-19, each branch offered one curbside pick-up activity only for children and left coloring papers outside to celebrate Black History (Branch B) and Irish Heritage (Branch C).

We applied quantitative analyses to all survey questions and to count library resources. Qualitative analyses were applied in classifying the nature of the multicultural programs from all listed programs.

In addition to use descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages, for the analysis of closed questions, we conducted two inferential analyses using Chi-square test and correlation. Using the Chi-square test, we examined the association between Korean immigrant parents’ sociodemographic characteristics and their responses to four continuous variables: time spent at home, time spent outside, time spent at the library, and their awareness of programs that the library offered for immigrants. We applied Spearman’s rank order correlation to find relationships among these four variables. All quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS v.20, with a statistical significance of alpha < 0.05. For the analysis of the open-ended questions, we classified the participants’ similar answers into groups (e.g., ESL class) and used descriptive statistics.

We analyzed the library programs according to the categories of age, language type, and multicultural nature. When a program indicated that the target age groups were children and adolescents or adolescents and adults, we classified this program as being for children or adults, respectively. We paid attention to programs offered in languages other than English. To qualify as multicultural programs, program descriptions had to specifically include multicultural components. We did not consider a book club meeting as multicultural unless the program description specifically stated that the book club members were asked to read about a certain race/ethnicity. We found that the multicultural programs could be further divided into two subcategories considering target audiences: (a) programs that would benefit immigrants, and (b) programs offered to the public to learn about racial/ethnic groups.

To calculate the number of programs offered, we counted their titles. When counting the frequency of a program, we kept in mind how many times a user could have access to the program and counted the number of available sessions. For the quantitative analysis, we used descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages.

To ensure the trustworthiness of this study, the first two authors of this manuscript conducted a reliability check. The first author briefed the other member about the codebook and analysis processes. Then we independently searched to locate books and digital media in Korean. For the program analysis, we independently read the descriptions of all programs and counted the number and frequency of programs offered by age group, language type, and multicultural characteristics. For Phase 1, in total, we analyzed 33 children’s programs offered 106 times and 56 adult programs offered 187 times by B and C branches. For Phase 2, in total, we analyzed 67 children’s programs offered 432 times and 162 adult programs offered 630 times by B and C branches. We had 100% agreement for locating resources in Korean and analyzing Phase 1 library programs. We had 97% agreement for Phase 2 on library program analysis. The disagreement between us was reviewed until we reached consensus.

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 2. Because most fathers had higher levels of education than the mothers did and worked at full-time jobs, we considered only the mothers’ demographic data for statistical analysis. Of the 141 respondents, 82% of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree or higher. About half (53%) of the mothers worked either in part-time or full-time jobs. Fifty-four percent reported family income as above $50,000. About 45% of the respondents had more than two children. About 45% of the respondents had lived in the United States for 10 years or less. About 52, 33, and 13%, respectively, of the parents reported that their children were in Grade 3 or below, Grades 4 to 7, or Grades 8 to 11.

As shown in Table 3, about 32% of the respondents reported that they went to their local libraries a few times a month. Thirteen percent of the respondents reported that they frequently spent time at libraries (i.e., a few times in a week). Another 13% reported that they had not visited libraries for the last 1 year. Most respondents (79%) resided in County A (22%), County B (26%), or County C (31%), and they used their respective county libraries as a major resource to meet their own and their children’s library needs.

When multiple answers were considered, as shown in Table 4, the most prominent reasons for using library resources were for their children to read books (97%), use study space (18%), read books to meet parents’ own needs (12%), and participate in library programs (8%). Although 7% of the parents responded that their local libraries offered programs for immigrants, 65% did not think that this was the case, and another 17% did not know whether the libraries actually offered such services. When multiple responses were considered, the Korean immigrant parents who reported dissatisfaction with local library services identified language barriers (38%), lack of Korean resources (38%), and lack of organized cultural events (25%) as the reasons. About 10% of the parents stated that they did not know how to use the local libraries.

Table 5 shows correlations among the four variables (i.e., spent time at home, spent time outside, spent time at library, and whether library offered programs for immigrants). The more time that the parents spent at the libraries, the more they believed that the libraries offered programs for immigrant families, = 0.25, p < 0.01. When the parents spent time outside with their children, there was a high possibility that they would go to the local libraries, = 0.67,

p < 0.01. Parents who used the local libraries tended to spend more time with their children at home, = 0.27, p < 0.01, as well as outside, = 0.39, p < 0.01.

In the follow-up analyses, we found insignificant associations between responses to the four aforementioned variables and parents’ sociodemographic characteristics relevant to mothers’ working status, income level, mothers’ levels of education, children’s grade levels, and years in the United States. The only significant finding was that the parents tended to spend more time at home when the children were younger [ (4, N = 128) = 27.64, p < 0.01].

Of the 141 respondents, according to the data from the first closed question, 82% either did not think the libraries offered programs or did not know whether the libraries offered programs for immigrants, so only 15 responses to the open-ended question were obtained. Twenty-seven percent (n = 4) of the responses showed that parents were aware of generic library services such as borrowing books in English (n = 3, 20%) or in Korean (n = 1, 7%). Parents were aware of programs such as ESL classes (n = 8, 53%), Asian Heritage Month (n = 1, 7%), support for citizenship tests (n = 1, 7%), and help with job searches (n = 1, 7%; see Table 6).

Thirty-three responses were obtained for an open-ended question asking the parents to list services and programs that they asked the public libraries to provide to meet future needs. Among the 33 responses, 61% of the respondents asked that the libraries offer services related to meeting their learning needs by requesting ESL classes (30%), cultural events (12%), classes for adults (9%), and books in Korean (6%). Thirty three percent of parents requested libraries to offer academic support programs for their children (see Table 7).

We researched the resources at the three library systems before and during COVID-19. The results were not much different, so the results only from the Phase 1 analysis are reported here because the results were gathered in a way to triangulate responses from participants who completed the questionnaire during the same Phase 1. The results from Phase 2 are available upon request.

Books written in Korean in the County A, B, and C library systems totaled 371 (0.27%), 636 (0.27%), and one (0%), respectively, of the entire volume of approximately 137,000, 236,000, and 125,000 books in three systems, respectively. Among them, 226 (0.16%), 604 (0.26%), and 0 books were for adults, and 145 (0.11%), 32 (0.01%), and one (0%) books were for juveniles. One (0%), 16 (0%), and 0 books for adults and 0, 1, and 1 book for juveniles had been published on or after 2009, respectively (see Table 8).

The County A library system had 14 (0.01%) adult and two (0%) juvenile electronic materials in Korean. The County B library system had 85 (0.04%) adult and four (0%) juvenile electronic materials in Korean. Among them, at County A and County B, seven (0%) and 17 (0%) electronic materials in Korean for adults were published on or after 2009, respectively; for juveniles, none of them was published on or after 2009. No electronic resources in Korean were found in the County C library system (see Table 8).

At Branch B, before COVID-19, one of 22 children’s programs (5%) was multicultural, taking up 8% of program offerings (four of 50 slots). During COVID-19, multicultural programs were absent at the time the frequencies of children’s programs were increased by 4.5 times (from 50 to 225 slots; see Table 9).

At Branch C, before COVID-19, one of 11 children’s programs (9%) was multicultural, taking up 2% of program slots (one of 56 slots). During COVID-19, nine of 46 children’s programs (20%) was multicultural, taking 7% of program slots (15 of 207 slots). From before COVID-19 to during Covid-19, the number of multicultural programs increased from 9 to 20% and the frequency of offering multicultural programs increased from 2 to 7% while the total number of programs for children increased almost fourfold from 11 to 46 (i.e., 400%).

Before COVID-19, regardless of branch, the one multicultural program offered was to learn about Latinx culture and was offered in a language other than English. During COVID-19, Branch B did not offer any multicultural programs. At Branch C, during COVID-19, among the nine multicultural programs (20% of 46 programs), three programs were not organized for any specific cultural groups in mind (e.g., culture craft, 7%) and the other six programs were to learn about such cultures as African (2%), Asian (2%), Bulgarian (2%), Irish (2%), Latinx (2%), and Middle Eastern (2%), all of which, with the exception of the Latinx culture (offered three times), were offered once.

At Branch B, before COVID-19, eight of 48 adult programs (17%) were multicultural programs focused on race/ethnic diversity. Among them, three programs (6%) were for immigrants to learn English, and five programs (11%) were for the public to learn about Asian culture (three programs, 6%) and cultural non specified (two programs, 5%). During COVID-19, the number of programs for learning about Asian culture decreased to 0%. In terms of frequency of offering, these eight multicultural programs were offered 30 times (18% of 166 slots): 24 times (14%) for immigrants and six times (4%) for the public (see Table 10).

During COVID-19, at Branch B, 14 of 31 (45%) adult programs were multicultural programs. All multicultural programs during COVID-19 were related to issues surrounding the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, but none of multicultural programs offered before COVID-19 at that branch was to learn about African American culture. No programs were offered in languages other than English before and during COVID-19. From before COVID-19 to during Covid-19, the number of multicultural programs increased from 17 to 45% and the frequency of offering multicultural programs increased from 18% (30 of 166 slots) to 43% (97 of 244 slots; see Table 10).

At Branch C, before COVID-19, one of eight adult programs (13%) was a multicultural program. It was for immigrants, and no multicultural programs about race/ethnic diversity were offered for the public. During COVID-19, the number of multicultural programs increased from 13% (one of eight) to 26% (34 of 131), and the frequency of offering multicultural programs decreased by 11% from 57% (12 of 21 slots) to 46% (186 of 406 slots).

During Covid-19, at Branch C, 34 of 131 adult programs (26%) were multicultural programs. Among them, 13 programs (10%) were for immigrants, and 21 programs (16%) were for the public. Of 13 programs for immigrants, 10 (8%) were ESL programs and three (2%) were programs offering neutralization help to address immigrants’ civic needs. Two multicultural programs (2%) for the public were conducted in languages other than English.

In terms of offering frequency at Branch C during Covid-19, 34 multicultural programs were offered 186 time (46% of 406 time slots). Among them, the 10 ESL programs were offered 96 times (24% of 406 slots) and three civic programs were offered for nine times (2% of 406 slots). Except one, ESL classes for five race/ethnic groups (Cantonese, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, and Vietnamese) and four ability groups (A, B, C, and D) were offered 10 times each (2.5% slots). Multicultural programs for the public were offered 81 times (20% 406 slots) and allocated to learning about African Americans (11%), nonspecific groups (4%), Hispanic Americans (3%), and Asian Americans (2%, see Table 10).

About 79% of the Korean immigrant parents visited their respective local libraries at least once a year. When the parents spent time with their children outside, they were more likely to visit libraries. Most of them used local county libraries, and the most frequently reported number of library visits by the families (32%) was a few times per month. This visiting frequency was much higher than the average number of library yearly visits per capita in 2018, which was 2.5 (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2021) in State A, where its national ranking for state operating budget per capita was second to last in the United States in 2018 (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2018b).

RQ1: What are the ways Korean immigrant parents use libraries to support their own needs and their children’s learning? Our results showed that although 64% of the parents visited libraries for the sole purpose of providing their children with the opportunity to read books, another 36% (33% for other purposes in addition to reading children’s books, and another 3% for other sole purposes) took advantage of libraries for multiple purposes, such as using the study spaces, reading books for themselves, and participating in library programs. These results supported Luévano-Molina’s (2001) conclusion that families with children had strong reasons for using libraries.

Thomas et al. (2016) asserted that immigrants enjoyed the social space, supportive environment, and opportunities for relationship building with others through the services and programs provided by libraries. However, our results showed that only 7% of the parents knew about organized programs for immigrants offered by the libraries. In addition, 82% of 141 respondents were not sure about (17%) and did not think (65%) that the programs for immigrants were offered by branch libraries.

When the 7% (n = 10) of parents in our study who knew that the libraries offered programs for immigrants were asked to list the programs, they considered the libraries as mainly providing ESL classes and lending children’s books. This response was not surprising because before COVID-19, Branch B and Branch C, located in communities comprising 13 and 27% immigrant populations, offered only three of 48 (6%) and one of eight (13%) programs, respectively, for immigrant adults. All of these programs were ESL programs, and no programs were offered to meet economic or civic needs. Therefore, the Korean immigrants’ responses, if they ever thought about the programs for immigrants that the libraries offered, were mainly ESL classes, clearly reflecting the lack of diverse programs offered by the libraries for immigrants.

During COVID-19, Branch B did not offer any programs for adult immigrants, and at Branch C, the percentage of programs for them was reduced from 13% (1 of 8) to 10% (13 of 131 programs). During the peak of COVID-19, all branch libraries used virtual programs, so these changes might have raised the concern expressed by Zhuang et al. (2021) about “whether or how the new norm of online platforms for interactions is effective and equitable” (p. 234) for immigrants.

RQ2: If the Korean immigrant parents do not take advantage of library services, what are the reasons? Because linguistic barriers and cultural insensitivity demonstrated by library staff have been documented as reasons for immigrants’ dissatisfaction with library services (Burke, 2008), this result was not unexpected. However, the significance of our study is that we documented the lack of resources in the immigrants’ native language (38%) as well as the lack of organized cultural events (25%) as strong reasons for their dissatisfaction with library services. The respondents’ dissatisfaction with the lack of Korean resources was validated by the fact that except for 18 books and 24 e-resources, none of the more than 500,000 materials housed in three county libraries for adults and juveniles was published on or after 2009. The parents wanted the three public library systems to make books in Korean available in communities with Korean populations of 0.61, 0.48, and 2.8% in County A, County B, and County C, respectively. To meet their needs, Korean immigrants have been buying used books in Korean through a community non-profit website (State A Tech Korean Student Association, n.d.).

It is important to carry minority language resources in libraries. By observing ways that majority and minority languages function in a community, children and adults may develop feelings of shame from using lower status languages that may lead to the loss of one’s heritage language and culture (Reese and Goldenberg, 2006). Having materials in one’s native language and making programs available in languages other than English reinforce family bonds (Pryor, 2001; Reese and Goldenberg, 2006) by raising the persistence of immigrant children and adults to maintain their first language and native culture (Schecter and Sherri, 2009) and reducing the “fragility of heritage language maintenance” experienced by immigrants living in suburban areas in particular (Reese and Goldenberg, 2006, p. 58).

In this sense, it was worrisome that for children, Branch B (one of 22, 4.5%) and Branch C (one of 11, 9%) offered only one program in a language other than English before COVID-19. During COVID-19, the percentages were further decreased to 0% (0 of 21) and 2% (one of 46), respectively. For adults, no programs were offered in languages other than English at Branch B before and during COVID-19; at Branch C, the number of programs increased from zero to 2% (two of 131). The number and frequency of programs in languages other than English did not reflect the multilingual demographic composition in the two counties of at 15, and 35%, respectively.

RQ3 asked: What programs/services do the libraries offer to support immigrants’ needs and multiculturalism in the community before COVID-19 and during COVID-19? Before COVID-19, Branch B offered 10% of programs (five of 48), and Branch C did not offer any programs to the public that could promote multiculturalism in communities where minority populations were 61 and 65%, respectively. These programs for the public also could be considered ones that met immigrants’ cultural needs (Koerber, 2016). The scarcity of multicultural programs for the public might have led 25% of the participants in the current study to express dissatisfaction with library services.

When we researched the offering of programs at the libraries for 2021, hate crimes against Asian Americans were “intensively visible” (Kimura, 2021, p. 141), and increased by 77% during COVID-19 when compared to one reported in 2019 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2022). Even though the number of multicultural programs provided for adults by the library systems increased by 28% (from 17 to 45%) and 13% (from 13 to 26%) at Branch B and C, respectively, none of the programs acknowledged the increased racism toward Asian Americans, who made up 7 and 12% of the population in County B and County C, respectively. The four programs (3% of 131) about Asian culture offered to the public at Branch C during COVID-19 were customary programs such as Chinese zodiacs, Chinese New Year crafts, native Vietnamese, and traditional brewing of tea.

The lack of (re)action by the local library systems to the racist discourse toward Asian Americans delivered the message that such hate speech is “the norm or accepted” (Kimura, 2021, p. 139); Asians are insignificant members of the communities; and integration of Asians into communities can be ignored (Kimura, 2021). Even though children were not exempt from physical attacks and verbal ridicule, such as Chinese dietary habits, during COVID-19 (see Stop AAPI Hate, 2020; Kimura, 2021), the number of multicultural programs for children was reduced to 0 at Branch B and the frequency of children’s multicultural programs at Branch C was only 7% (15 of 207 slots).

The last RQ asked about future programs/services that Korean immigrant parents wanted the libraries to provide. The Korean immigrant families wanted public libraries to offer cultural events allowing people of all backgrounds to share beliefs and interests. Morgan et al. (2016) reported that immigrants wanted programs that could nurture interactions among traditionally segregated racial and ethnic groups at public libraries. Audunson (2005) argued that paradoxically, “democracy in a multicultural context is dependent on low-intensive meeting places where we can see one another” (p. 430).

It has been reported that the demand for ESL classes “far exceeds” (Morgan et al., 2016, p. 2034) the supply. There were few ESL classes prior to (three ESL program [6%] at Branch B and one program [13%] at Branch C) and during COVID-19 (0 at Branch B and 8% at Branch C) in counties where multilingual population were 15 and 35%, respectively. During COVID-19, expanding the number of users from a local branch to the entire County C library system using virtual formats might have increased the number of ESL classes being offered from one to 10. However, nine of the 10 classes were designed for five races/ethnicities and four ability groups, meaning that a Korean library user could take a maximum of two classes. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics (2018) indicated that the number of users in State A who took ESL classes decreased by 33%, from 9,757 in 2015 to 6,572 in 2018 because of library budget cuts (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020), further validating the result that 30% of respondents wanted libraries to offer more ESL classes.

The Korean immigrants’ desire to tap into library resources for their own (61%) and their children’s educational needs (33%) was robust. The families in our study expressed a clear interest in participating in programs and services offered by libraries, especially those relevant to their children’s academic achievement. The families wanted the local libraries to offer academic support to their children by providing various programs such as reading books, book club, ESL for children, homework assistance, strong summer program, more events for children, and SAT class. None of the libraries before and during COVID-19 offered programs specifically directed toward children from immigrant families. Morgan et al. (2016) also reported that immigrants with young children asked their local libraries for homework assistance.

Limitations of the study need to be addressed before we discuss the implications. Even though we compared library program data prior to and during COVID-19, the questionnaire was completed prior to COVID-19. If the questionnaire had been administered during COVID-19, the respondents’ responses might have been different. However, we doubt that possibility because the nonexistence of library programs to address racism toward Asian Americans further validated the respondents’ concerns about the lack of programs supporting their adjustment in the host country and fostering dialogues among different racial/ethnic groups.

The second limitation was that only 48 responses were obtained for the open-ended questions. Concerns about the generalizability of the results based on the open-ended questions were mitigated by the fact that a similar pattern to the open-ended questions was found in the close-ended questions answered by a large number of the respondents and that we further analyzed library programs at two of the library systems to validate the participants’ responses to the open-ended questions.

The last limitation was that because libraries schedule programs according to national holidays and celebratory events, we were not in a position to ensure that the multicultural programs offered during the data-gathering period were representative of the number of multicultural programs at the target libraries. However, during the search period, the fact that Black History month, a highly celebrated holiday in the United States, was included along with Asian Lunar New Year and Irish Heritage celebration might have meant that the number of multicultural programs planned was no fewer than usual.

The results also have several implications. First, because the majority of the U.S. population still read paper books, even though the number of e-book readers is growing each year (Pew Research Center, 2021), libraries need to have more electronic materials and books written in immigrants’ native languages, along with programs in languages other than English. By updating books and resources supporting immigrant families’ efforts to maintain their native languages and cultures, public libraries can “highlight the first language and make it a living language” (Schecter and Sherri, 2009, p. 69). “To advocate for equal access to citizens” (County B Library System, n.d.) and “empower all residents” (County C Public Library, n.d.), libraries need to find ways to provide books and resources written in immigrant families’ native languages. In that sense, because 87.1 and 86.7% librarians in the United States were White in 2014 and 2017, respectively (American Library Association Office for Research and Statistics, 2017), reform efforts need to focus on increasing staff diversity (Hall, 2020) and overcoming the culture of Whiteness (Audunson et al., 2018).

Second, public libraries need to consider supporting immigrants’ linguistic needs by offering one-to-one tutoring assistance for children and more ESL classes for adults. The respondents in our study wanted to increase their and their children’s cultural capital by learning English. Libraries might be the only public facilities where immigrants can learn English at no cost. Last, if libraries of the future want to become public spaces offering low-intensive programs that nurture democratic communities, as Audunson (2005) argued, they need to continue to develop multicultural programs for children and adults.

During COVID-19, Branch B library dedicated all of its multicultural programs (45% of all programs) in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, with the implication being that the nonexistence of programs to mitigate racism toward Asian Americans might be related to the lack of resources rather than the lack of intention to address the social issues. Because the lack of skilled librarians to offer relevant classes was the primary reason for not offering the classes (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000), it is important to hire skilled librarians who can develop inclusive programs and who can speak languages other than English.

We had difficulty finding critical investigations of library services for minority communities; more often than not, previous case studies have focused on what libraries have done for immigrant groups. More studies similar to our investigation are needed to “co-create community narratives and solutions” with immigrant groups (Zhuang et al., 2021, p. 234) to provide a broader range of library services. Welsh et al. (2021) expected that the way future libraries will be operated is going to be different from the prepandemic model. “Returning to the status quo should not, must not, be an option after Covid-19… There is no other way” (Hertel and Keil, 2020, p. 13). It is our hope that Korean immigrants’ suggestions about ways to improve library services will be integrated into policy decisions to create an “equity-based approach for public-space use” (Zhuang et al., 2021, p. 235) that can empower minorities and create a just community.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Kennesaw State University IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YK and HK contributed to the conception and design of the study, and organized the database. JK performed the statistical analysis. YK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HK and JK wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

American Library Association (2015). Public library use. Available at: https://www.ala.org/tools/libfactsheets/alalibraryfactsheet06#usagelibs

American Library Association Office for Research and Statistics (2017). 2017 ALA demographic study. Available at: https://www.ala.org/tools/sites/ala.org.tools/files/content/Draft%20of%20Member%20Demographics%20Survey%2001-11-2017.pdf

American Library Association Public Programs Office. (2018). News: NILPPA update: What is a public program, anyway? Available at: https://programminglibrarian.org/articles/nilppa-update-what-public-program-anyway

American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology (n.d.). Minority Group. Available at: https://dictionary.apa.org/minority-group

Aptekar, S. (2019). The public library as resistive space in the neoliberal city. City Community 18, 1203–1219. doi: 10.1111/cico.12417

Audunson, R. (2005). The public library as a meeting-place in a multicultural digital context: the necessity of low-intensive meeting-places. J. Doc. 61, 429–441. doi: 10.1108/00220410510598562

Audunson, R., Aabø, S., Blomgren, R., Evjen, S., Jochumsen, H., Larsen, H., et al. (2018). Public libraries as an infrastructure for a sustainable public sphere: a comprehensive review of research. J. Doc. 75, 773–790. doi: 10.1108/JD-10-2018-0157

Barton, A. C., Drake, C., Perez, J. G., Louis, K., and George, M. (2004). Ecologies of parental engagement in urban education. Educ. Res. 33, 3–12. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033004003

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. ed. J. Richardson (New York: Greenwood Press), 241–258.

Burke, S. K. (2008). Use of public libraries by immigrants. Ref. User Serv. Q. 48, 164–174. doi: 10.5860/rusq.48n2.164

Costigan, C. L., and Koryzma, C. M. (2011). Acculturation and adjustment among immigrant Chinese parents: mediating role of parenting efficacy. J. Couns. Psychol. 58, 183–196. doi: 10.1037/a0021696

County A Public Library (n.d.). History of the library. Available at: https://www.cobbcounty.org/library/about/history

County B Library System (2021). Public reopening FAQ. Available at: https://www.fulcolibrary.org/blogs/post/public-reopening-faq/

County B Library System (n.d.). About us: Our mission. Available at: https://www.fulcolibrary.org/our-mission/

County C Public Library (2021). Events. Available at: https://gwinnettpl.libnet.info/events

County C Public Library (n.d.). About County C library. Available at https://www.gwinnettpl.org/about-gcpl/

Gaetano, Y. D. (2007). The role of culture in engaging Latino parents’ involvement in school. Urban Educ. 42, 145–162. doi: 10.1177/0042085906296536

Garcia, E., and Stein, C. B. (1997). Multilingualism in U. S. Schools: treating language a resource for instruction and parent involvement. Early Child Dev. Care 127, 141–155. doi: 10.1080/0300443971270112

Glander, M., and Dam, T. (2006). Households’ Use of Public and Other Types of Libraries: 2002 (NCES 2007–327). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2007/2007327.pdf

Hall, T. D. (2020). From the executive director: ending information redlining: the role of libraries in the next wave of the civil rights movement. ALA 51:5.

Hertel, S., and Keil, R. (2020). After Isolation: Urban Planning and the Covid-19 Pandemic. North York, NY: Ontario Professional Planners Institute.

Institute of Museum and Library Services (2018a). Public libraries survey, FY 2016: Data file documentation and user’s guide. Available at: https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/fy2016_pls_data_file_documentation.pdf

Institute of Museum and Library Services (2018b). Public libraries survey, FY 2018. Table 29: State rankings on key variables. Available at: https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/fy2018_pls_tables.pdf

Institute of Museum and Library Services (2021). Public libraries survey, fiscal years 2018: Supplementary tables. Available at: https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/fy2018_pls_tables.pdf

Kimura, K. (2021). “Yellow perils,” revived: Exploring racialized Asian/American affect and materiality through hate discourse over the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hate Stud. 17, 133–145. doi: 10.33972/jhs.194

Koerber, J. (2016). Celebration & integration: service to immigrants and new Americans, an integral part of the public library mission, is being taken to the next level. Library J. 141, 48–51.

Lei, L., and Guo, S. (2022). Beyond multiculturalism: revisioning a model of pandemic anti-racism education in post-Covid-19 Canada. Int. J. Anthropol. Ethnol. 6, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s41257-021-00060-7

López, G. R., Scribner, J. D., and Mahitivanichcha, K. (2001). Redefining parental involvement: lessons from high-performing migrant-impacted schools. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 253–288. doi: 10.3102/00028312038002253

Luévano-Molina, S. (2001). “Mexican/Latino immigrants and the Santa Ana public library: an urban ethnography” in Immigrant Politics and the Public Library. ed. S. Luévano-Molina (Westport, CT: Greenwood), 43–63.

Metoyer-Duran, C. (1991). Information-seeking behavior of gatekeepers in ethnolinguistic communities: overview of a taxonomy. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 13, 319–346.

Migration Policy Institute (n.d). Largest U.S. immigrant groups over time 1960-present. Available at: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/largest-immigrant-groups-over-time?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true

Morgan, A. U., Dupuis, R., D'Alonzo, B., Johnson, A., Graves, A., Brooks, K. L., et al. (2016). Beyond books: public libraries partner for population health. Health Aff. 35, 2030–2036. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0724

National Center for Education Statistics (2000). Programs for adults in public library outlets. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/frss/publications/2003010/index.asp?sectionid=7

National Center for Education Statistics (2018). Table 507.20. Participants in state-Administered adult basic education, secondary education, and English as a second language programs, by type of program and state or jurisdiction: Selected fiscal years, 2000 through 2016. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_507.20.asp

National Center for Education Statistics (2020). Table 507.20. Participants in state-administered adult basic education, secondary education, and English as a second language programs, by type of program and state or jurisdiction: Selected fiscal years, 2000 through 2018. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_507.20.asp

Pew Research Center (2021). Three-in-ten Americans now read e-books. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/01/06/three-in-ten-americans-now-read-e-books/

Polese, V. (2017). ‘Re-scaling’ the discourse of immigrant integration: the role of definitions. Int. J. Lang. Stud. 11, 153–172.

Pryor, C. B. (2001). New immigrants and refugees in American schools: multiple voices. Child. Educ. 77, 275–283. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2001.10521650

Rah, Y., Choi, S., and Nguyên, T. S. (2009). Building bridges between refugee parents and schools. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 12, 347–365. doi: 10.1080/13603120802609867

Reese, L., and Goldenberg, C. (2006). Community contexts for literacy development of Latina/o children: contrasting case studies. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 37, 42–61. doi: 10.1525/aeq.2006.37.1.42

Schecter, S. R., and Sherri, D. L. (2009). Value added? Teachers’ investments in and orientations toward parent involvement in education. Urban Educ. 44, 59–87. doi: 10.1177/0042085908317676

Singer, A., and Wilson, J. H. (2011). Immigrants in 2010 metropolitan America: A Decade of Change. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/immigrants-in-2010-metropolitan-americaa-decade-of-change/

State A Tech Korean Student Association (n.d.). Used market [중고장터]. available at: https://gtksa.net/bbs/board.php?bo_table=used

Stop AAPI Hate (2020). They Blamed Me Because I am Asian: Findings from Reported Anti-AAPI Youth Incidents. Available at: https://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/Stop-AAPI-Hate-Youth-Campaign-Report-9.11.20.pdf

Su, S. S., and Conaway, C. W. (1995). Information and a forgotten minority: elderly Chinese immigrants. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 17, 69–86. doi: 10.1016/0740-8188(95)90006-3

Tett, L. (2001). Parents as problems or parents as people? Parental involvement programmes, schools and adult educators. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 20, 188–198. doi: 10.1080/02601370110036037

Thomas, R. L., Chiarelli-Helminiak, C. M., Ferraj, B., and Barrette, K. (2016). Building relationships and facilitating immigrant community integration: an evaluation of a cultural navigator program. Eval. Program Plann. 55, 77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.11.003

U.S. Census Bureau (2019). American community survey demographic and housing estimates [data table for 2019]. Available at: https://data.census.gov/cedsci

U.S. Department of Justice (2022). 2020 Hate crimes statistics. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/crs/highlights/2020-hate-crimes-statistics

Vårheim, A. (2011). Gracious space: library programming strategies towards immigrants as tools in the creation of social capital. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 33, 12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2010.04.005

Wang, P. (2021). Struggle with multiple pandemics: women, the elderly and Asian ethnic minorities during the OCVID-19 pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Int. Stud. 17, 14–22. doi: 10.5130/pjmis.v17i1-2.7400

Welsh, M. E., Burke, I., and Estes, J. (2021). Uncertainty and resilience: experiences at theological libraries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Theol. Librarianship 14, 1–21. doi: 10.31046/tl.v14i1.2729

Keywords: Asian immigrant, COVID-19, multicultural programs, library programs, library resources and services

Citation: Kim Y, Kim HCL and Kim J (2023) Korean immigrants’ perceptions of library services and library multicultural programs for Asian communities before and during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 8:1081143. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1081143

Received: 26 October 2022; Accepted: 07 June 2023;

Published: 07 July 2023.

Edited by:

Mohammed Saqr, University of Eastern Finland, FinlandReviewed by:

Shoba Nayar, Independent researcher, Chennai, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Kim, Kim and Kim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanghee Kim, eWtpbTQ0QGtlbm5lc2F3LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.