- Centre for Research in Education and Psychology, University of Evora, Evora, Portugal

Introduction: The inclusion of children with special needs is one of the biggest challenges faced by educational systems around the world, corresponding to the UNICEF Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all. This process is even more complex process in low-income countries, where the entire education system has significant insufficiencies and support for families with children with disabilities is limited. This present study aims to chart the challenge of implementing inclusive education in Mozambique. Its main objective is to sound the perspectives and expectations of teachers about the education for children with disabilities in their country: (a) its advantages and suitability, (b) needs, obstacles, and difficulties, and (c) resources, practices and strategies already used.

Methods: A qualitative approach was used, with 40 teachers participating in three focus group, submitted later to a content analysis.

Results: The results denote the value and importance of moving toward greater inclusion of children with disabilities in Mozambique and increased awareness among teaching staff to uphold the basic right to education, although the conception of inclusion as a distinct special education subsists.

Discussion: Teachers identify multiple needs and difficulties in terms of equipment, resources, and practices, and recognize a path that must be continued for inclusion to take place, namely with regard to inclusive public policies and the need for major investment and change in the level of teacher training, which is central to educational transformation.

1. Introduction

UNICEF’s fourth SDG refers to the need to guarantee inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Access to schooling and educational inclusion for children with disabilities is one of the greatest challenges for education systems around the world (Okyere et al., 2019). This process is doubly complex in low-income countries, where the education system still has significant shortcomings and deficiencies, and where support for these children’s families is quite limited (Phasha et al., 2017).

Mozambique, like most African countries (SADC, 2017), has committed to implementing an inclusive education system. Although there is great consensus on the need to promote access to the education system for children with disabilities, there are a great many obstacles; in Sub-Saharan Africa (Trust, 2016) about 6.4% of the population is made up of children with disabilities, many of which are not in school, limited in their rights to education, participation, protection from violence and abuse, living a full, independent and dignified life, and able to play an active role in society. Education is a fundamental right for everyone, including these children, and school enrollment protects them from abuse and harm of different types (Trust, 2016). In Africa, people with disabilities are often part of the most vulnerable groups, illiterate, poorly educated, unemployed, with the lowest incomes and the poorest living conditions (SADC, 2017).

In Mozambique, the national Constitution recognizes equal rights to all citizens, as well as the responsibility of the State to ensure the equal opportunities and access to education. This represents the core legal footing for the school inclusion of children and young people with disabilities. Mozambique had co-signed and amended international treaties that protect and promote the rights of children and people with disabilities.

From these cornerstones, the biggest challenge is to promote widespread education, enabling an inclusive education system that ensures conditions of access and persistence for all children, regardless of their characteristics.

Through the years, different authors (Cossing, 2006; Chiziane, 2009; Nhapuala, 2010, 2011, 2014; Chambal, 2011; Lopes et al., 2020; Freitas Pacho and Zimbico, 2022) have noted the need for global strategies to promote the inclusion of children with disabilities, namely legislative and normative output, above and beyond Mozambique’s general legislative and political measures to promote the rights of people with disabilities. In practice, the implementation of inclusive education lacked specific legislation or overarching strategies, existing within the framework of much broader laws that governed the educational system and the protection of people with disabilities. The aforementioned framework has proved insufficient with regard to integration and practice of inclusive education (Nhapuala, 2014, p.31); despite, it should be noted, focused attempts such as the National Disability Strategy, introduced in 2009, and later a National Plan of Action on Disability for the period from 2012 to 2019 (Moçambique, 2012).

A decade after the kickstart of inclusive educational policies (Chambal, 2011), and despite legislative and public policy measures, the desired results were still far from being achieved when it comes to inclusive educational policies, which brings us to the potential hurdle represented by the schooling system itself.

The panorama prior to the implementation of school inclusion policies was quite bleak (Chambal, 2011). Data indicated highly selective and excluding practices within the regular schooling system. This prompted various initiatives, at different moments, to reform schools and the educational system at large, culminating with the introduction of inclusive schools into Mozambique’s educational network starting in 1998. In the wake of the Salamanca Declaration (UNESCO, 1994). Mozambique had committed to an inclusive education policy, implementing a pilot-project in five provinces. Since that time and through the efforts of the Strategic Plan for Education for the 1999–2003 period, this experience was then expanded to the entire country.

According to Ussene and Simbine (2015), when implementing inclusive education proposals, Mozambique encountered a variety of new challenges in the areas of infrastructure, specialized materials, teacher training, curricular adaptation for students with special needs, and the practice of Special Education in tandem with the promotion of inclusive education practices in regular schools. While there was an improvement to access to school and an increase in the number of enrollments, there was also an increase in the difficulties on the part of teachers in dealing with the diversity of students with special needs.

Inclusive education in Mozambique represents an ideal yet to be achieved, which means that there is still a lot of work to be done to transform schools into places of inclusion, where everyone can learn according to their individual particularities (Ussene and Simbine, 2015). There is also a commitment to implement a national strategy for the inclusion of children with disabilities that takes into account the reality on the ground and its agents.

Within this cornerstone approach, teachers are key players both in the educational process of children and youths (including those with disabilities or special needs) and in the process(es) of school inclusion. They are the educational agents with the greatest importance, contact and interaction with children. Their role is fundamental in educational development and for the construction of model systems and programs. Teachers’ perceptions, beliefs, expectations, and attitudes are inevitably decisive in the implementation and success of inclusive education (Silva et al., 2013). The development of the inclusive school presupposes changes at multiple levels, demanding teachers readjust to new circumstances so that they can effectively manage and implement inclusive practices.

Effective inclusion hinges on teachers’ attitudes toward students with special needs (ADENEE, 2003; Silva et al., 2013), on their ability to improve interactions, on how to perceive differences in the classroom, and on their ability to manage those differences effectively. Teachers must implement inclusion in their daily practice, which is why they are such a critical factor. Results depend on each teacher’s training, experiences, convictions and attitude, as well as classroom conditions, the school and, evidently, external factors (Prata, 2009; Terenciano and Gerente, 2018).

Teachers’ perspectives and attitudes also play an important role in the teaching-learning process of students, crucial as they are to the success of any educational change, particularly in the development of inclusive schooling, since “nothing and no one is more key to the improvement of schools than the teacher; educational change depends on what teachers do and think” (Silva et al., 2013, p.115).

The implementation of inclusive education has frequently encountered hurdles and difficulties at the teacher’s level (Sant’ana, 2005), namely the lack of training to meet special educational needs. Moreira also mentions that there is “an uncomfortable feeling of unease” felt by regular education teachers faced with the paradigm of inclusion due to a lack of adequate training and professional qualifications to deal with students with special educational needs, which translates into feelings of insecurity and uncertainty about how to face and adapt to this new process” (Moreira, 2007, p.30).

Studies carried out on the implementation of inclusion in the regular education system in different countries (Prata, 2009) have shown that teachers are able to distinguish obstacles during the process, foremost among these seem to be the lack of preparation to work and respond to children with disabilities, the time these children need, and the quality of learning. They often mention that they prefer that the support provided to these children take place outside the classroom, seeming apprehensive and unreceptive to change.

Since the regular education teacher is the most important resource in teaching children with disabilities (Sanches and Teodoro, 2007), this implies understanding teachers’ conceptions and practices on inclusion. If teachers are who children spend most of their time with at school, then it is essential to understand their thoughts, theories, and practices, so that children with disabilities can be included in a regular education class. The opinions of primary and secondary school teachers, who know the educational reality in Mozambique firsthand, are, therefore, critical to the development of a national strategy for inclusive education (Terenciano and Gerente, 2018; Brás, 2020).

The object of the present study is to inquire the perspective of these teachers on the educational inclusion of children with disabilities, in order to better understand the value, difficulties, and expectations they attribute to it. The research intends to contribute to the definition of a national strategy for inclusive education and the development of children with disabilities in Mozambique, seeking to better understand the inclusion process through teachers from schools in different regions.

Hinging on the central question “What is the view of teachers on the inclusive education process for children with disabilities in Mozambique?” the following research objectives were formulated:

a. to ascertain the opinions and perspectives of teachers on the applied concept of educational inclusion of children with disabilities, its advantages, and suitability for the Mozambican national context;

b. to identify the needs, obstacles, and difficulties felt by teachers in the process of including children with disabilities;

c. to identify the resources, methods, practices, and strategies used in the process of including children with disabilities.

2. Materials and methods

This study follows a qualitative approach, using focus groups, which are especially useful for collecting information in order to understand phenomena from the participants’ perspective of the situation which one wants to study (Krueger and Casey, 2000). The focus group (Morgan, 1997) operates on data collection through group interaction on a topic, and what defines and distinguishes it from other types of groups is the fact that it is oriented toward collecting qualitative data from people with some type of similarity, through a focused discussion in a group situation.

2.1. Participants

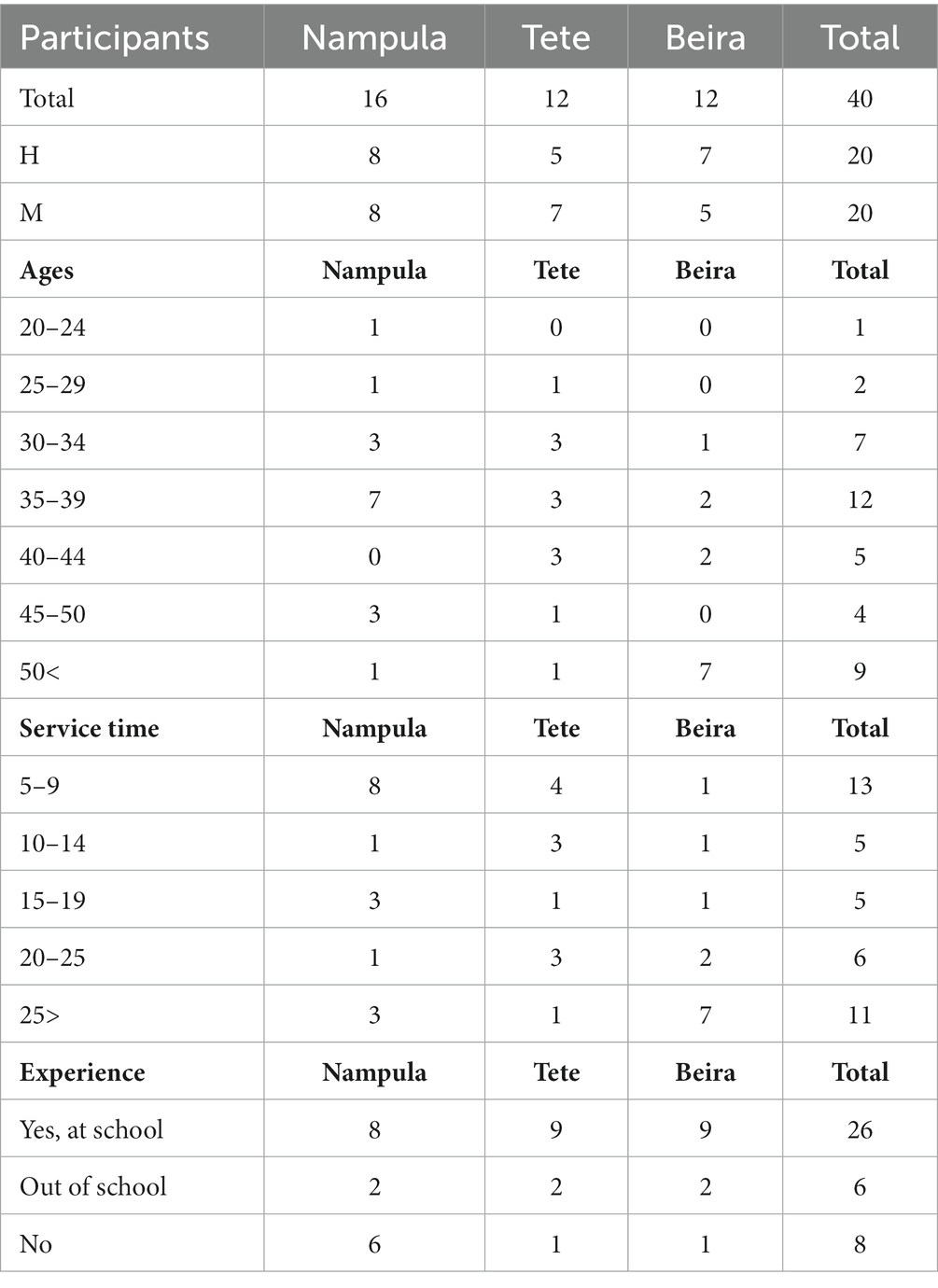

A total of 40 teachers, from regular public Primary and Secondary schools from three cities (Nampula, Tete, and Beira), in different Mozambican provinces, participated in this study, as a convenience sample. In each case a discussion/focus group was set up with 12–16 participants, with similar number of men and women (Table 1).

All participants possessed teaching experience of over 5 years, and a large group of teachers present had long careers, spanning more than 25 years. This leads to an age distribution between 20 and over 50, with a median in the 35–39 age group. Most teachers had direct experience of working with students with disabilities and only 8 had no such experience whatsoever.

2.2. Methodology

In each city, a school was chosen that provided a pre-equipped room as an adequate environment for the functioning of the focus group. The referral of participants to the focus group was carried out from a selection of local schools, and implemented by the district education authorities, so that the different establishments were represented: each school indicated 2 or 3 teachers dependent on availability on the chosen date.

Each focus group lasted between 60 and 70 min. All participants were informed of the group’s objectives, how proceedings would take place, and gave their informed consent for the recording of the sessions, so that they could be later transcribed, guaranteeing the confidentiality of their individual interventions.

2.3. Data analysis

For the analysis of the information produced by the groups, content analysis was employed (Bardin, 1977); the process includes several stages that glean meaning from the information, from the contents of the raw data.

The first stage (pre-analysis) consisted of: (a) direct contact with the material to be worked on; (b) definition of what would be analyzed; (c) formulation of hypotheses and objectives; and (d) elaboration of referencing indexes and indicators. A careful reading of all the material collected in the transcribed focus group sessions was carried out by two separate researchers.

The second, exploratory stage, consists of defining categories and coding the recording units. Qualification, classification, and categorization are elements of this stage, and so categories and subcategories were created. This process took into account the fundamental requirements of homogeneity, exhaustiveness, exclusivity, objectivity, and adequacy/relevance (Bardin, 1977). We chose to carry out a thematic analysis that functions by breaking up the text into units (Bardin, 1977), focusing on the characteristics of the message in terms of the value of the information and ideas expressed (Moraes, 1999). Thematic analysis is effective in the processing of direct speech and consists of discovering “nuclei of meaning” that make up communication and whose presence and/or frequency can mean be significant to the investigation (Bardin, 1977). Thematic analysis involves encoding open dialog between participants into closed categories that summarize and systematize information (Wilkinson, 2008). The aim of this approach is to formulate categories that map to the data collected and provide a simplified representation of the raw results (Bardin, 1977).

The final step consists of the treatment of results, inferences, interpretation, and emphasis of the data. Its purpose is to allow inferences based on an explicit logic about the messages whose characteristics were inventoried and systematized; that is, the material subject to analysis is conceived as the result of a network of productions, with the researcher having to build a model capable of producing inferences (Vala, 1986). Categorization is a process that aims to reduce the complexity of information, stabilize it, identify it, order it and/or provide meaning. Indicators were created with the aim of organizing the information extracted from the focus groups, in terms of the respective subcategories, thus imposing rigor to the classification and ensuring its internal validity. The selected recording unit, that is, a unitary element of content to be submitted for classification (Moraes, 1999), was the theme. This unit is found within the semantic record that are considered to be information units (Vala, 1986). Finally, an analysis grid was devised that includes the categories, subcategories, and the respective number of record units found, which allowed the synthesis of the information, systematizing the data and the participants’ responses as units of meaning, thus enabling the interpretation of the data.

3. Results

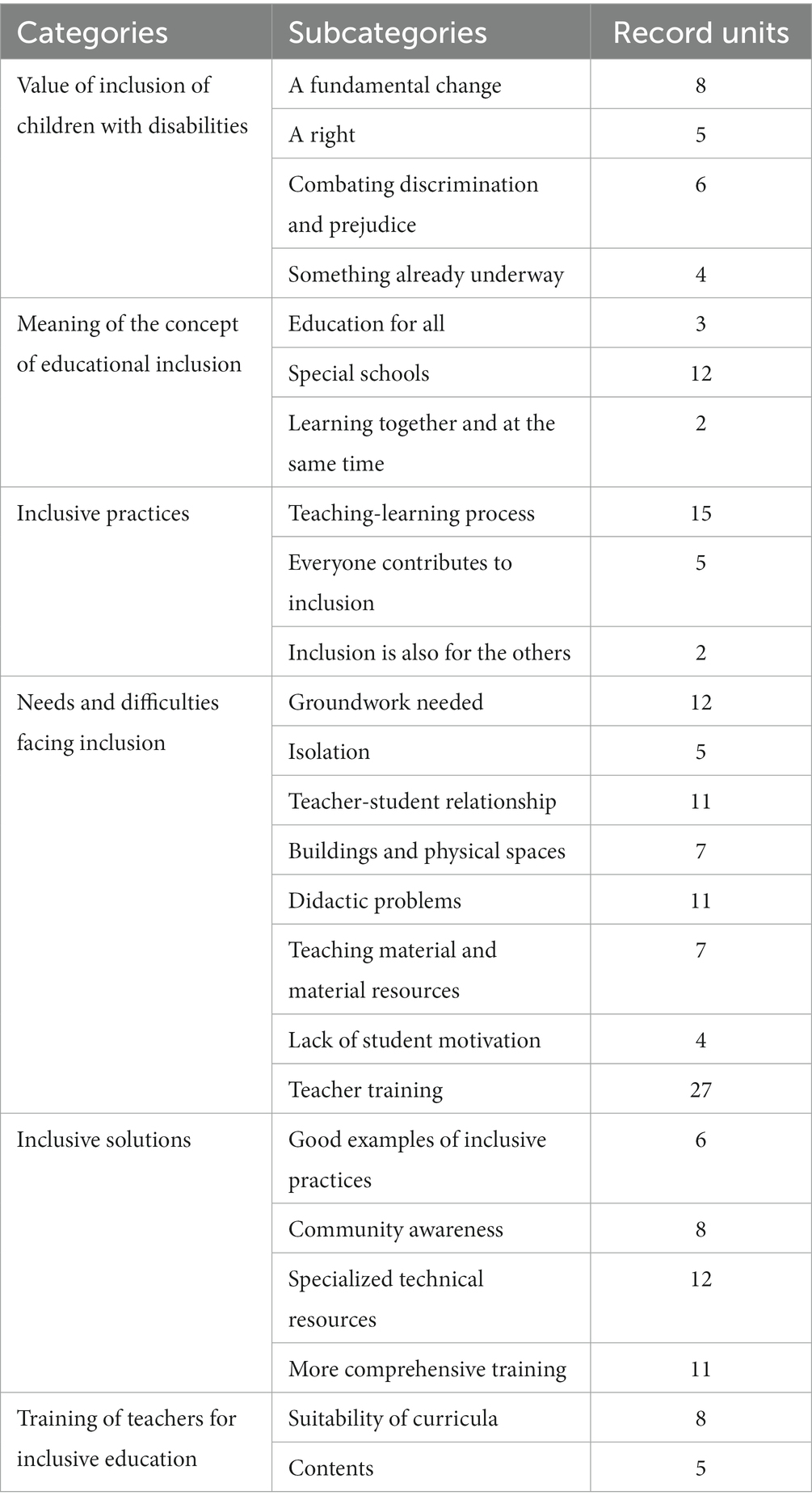

Six (6) categories and 24 (24) subcategories emerged from the thematic analysis of the teachers’ interventions in the focus groups (Table 2).

3.1. Value of inclusion of children with disabilities

Teachers are unanimously favorable to inclusion, in terms of both its value and importance. The four different subcategories represent the main justifications attributed to this value.

First, they refer to inclusion as a fundamental change. Many of the interventions suggest that inclusion means a different perspective to understanding children with disabilities. Whereas they had previously been considered useless, inclusion shifts this perception, allowing their integration into society. In the words of one teacher, “(…) inclusion itself is a blessing for Mozambique because our real child was considered useless, and inclusive education has come to change that scenario.”

Teachers also recognize educational inclusion as a right, and that children with disabilities have the right to socialize with others, to learn, to play, the right to equal education. The recording units refer to this idea: “(…) they have the human right to be with the others in the classroom.” As stated in the Salamanca Declaration “every child has the fundamental right to education and must have the opportunity to achieve and maintain an acceptable level of learning.” (UNESCO, 1994, p. viii).

From the teachers’ perspective, inclusion is also a factor in combatting discrimination and prejudice, it confronts a history of discrimination and marginalization of children with disabilities, combating prejudice and stigma. Inclusion aims to transform and combat this phenomenon (SADC, 2017) and “(…) they will learn to live with these people, to understand their side and in this manner, perhaps, we can reduce prejudice.”

Some of the participants emphasize that this process of change is something already underway, although, it appears, that in the path that is being followed “(…) there is inclusion, but it is not felt at the base.” In other words, there is still a long way to walk down this path.

3.2. Meaning of the concept of educational inclusion

Despite the unanimity regarding the value of access to school for children with disabilities, teachers express different ways of seeing inclusion, boiling down to two fundamental perspectives: one that points to the existence of special schools or separate classes and another to inclusive practices in the classroom and in regular schools.

For some, educational inclusion is based on the idea of education for all, that is, on the right of all children to have access to education, even if they have some type of disability. It also incorporates the perception that the concept of Inclusive Education combats the traditional approach of Special Education. The record units state that “if we say that education is for all, we should create conditions for all students” or “inclusion is a way of guaranteeing education for all.”

However, many teachers, despite agreeing on the importance of Inclusive Education, when speaking about the forms of implementing it, seem to point more toward the creation of Special Schools for these children. The differentiating aspects that would require these children to be taught separately are highlighted, although the examples always identify the difficulties or consequences of such a type of solution, namely in terms of isolation and segregation. “It can be a group, we go visit the room, we can teach the boys, but with a place, a class, a specific room (of their own).”

These more segregating attitudes toward children with disabilities often stem from the acknowledgment of a general lack of preparedness to deal with them, the overall quality of learning, and the difficulty in managing the diversity of said group.

A third subcategory emphasizes learning together and at the same time. This perspective of inclusion is shared by most teachers who see Inclusive Education as a reality in which all children learn together, at the same, time and in the same place (classroom), despite the demands and difficulties that this raises. If not, the children, listening to others in the next room, might feel discouraged and unmotivated, leading to abandonment and isolation: “(…) because these children need to be in an environment where they hear others shouting, running around….”

3.3. Inclusive practices

Promoting learning together raises the question of how. Most teachers recognize that effective inclusion has direct, serious and global implications for the teaching-learning process, raising challenges to teaching practices and to all aspects of student learning. “It is the teacher who has to understand the child’s problems and make the rest of the class understand these problems as well, and he has to create mechanisms to be able to work with that child amongst the other children.” This is seen as the core issue and the greatest challenge of an inclusive approach.

Another perspective from teaching staff underscores the individual and relational character of inclusion (subcategory everyone contributes to inclusion), in the sense that this has to be materialized in everyone’s individual practice. It cannot be done through rules and regulations, but by what each teacher does in the relationship with the children in his care. They exemplify, saying: “children with visual problems who cannot read sign language, so you have to turn to colleagues who master sign language.” Attitudes of cooperation and mutual help are underlined when dealing with children with disabilities in the teaching process, which, being an often-overlooked resource, should be valued for its contribution to improved learning (Booth and Ainscow, 2002).

A third idea is that inclusion is also for the others, that is to say, inclusion does not benefit children with disabilities only, but all other students as well. In terms of learning, but also in terms of promoting citizens who are better able to deal with difference: “(…) others who will start to be part of that child’s life will realize that after all we are all equal, with the same rights and duties.” Inclusive pedagogy is understood to be the best way to promote solidarity between students with special needs and their peers (UNESCO, 1994).

3.4. Needs and difficulties facing inclusion

This category encompasses the many difficulties and obstacles that teachers recognize in implementing inclusive principles and guidelines, grouped into eight subcategories.

The first subcategory (prior groundwork needed) reflects the view that preparatory work with parents, guardians, and the community is necessary, so that everyone is involved in the inclusive process. This item essentially refers to the need to raise everyone’s awareness of the rights of children with disabilities. As these children are still often seen as incapable and without a future, parents do not prioritize their education: “(…) these chiildren need support from their guardian and they do not have it; parents prefer to keep the child at home….” Many parents find it difficult to accept that they have a child with a disability and often withdraw the child from public and community life. “An individual who does not speak, with special education, can be useful to society itself, it is necessary to get this myth out of the parents’ heads.”

The second subcategory (Isolation) denounces the fact that children with disabilities are often in a situation of isolation: “There is a tendency for [guardians] to keep them at home” which constitutes an evident impediment to entering school and inclusion.

The subcategory teacher-student relationship highlights that one of the biggest problems toward inclusion has to do with the teachers’ difficulties in interacting and communicating with these children (particularly the deaf and blind). This often leads teachers to opt out of inclusive classes. The teacher-student ratio was also an important factor, as it also interferes with the relationship that can be established. It was also mentioned that when “the teacher cannot communicate with the student, it is not simply a problem for the student, but also for the teacher, who often lack the framework to explain what they want to convey to the student.”

Another obstacle refers to limitations in terms of buildings and physical spaces in schools. This reflects not only accessibility, but even in terms of the overall adequacy of spaces, referring to the existence of “undignified “spaces set aside these children, closed, poorly lit, inadequate, with fewer conditions to work with. This, in turn, leads to less productive and lower quality teaching “(…) as if such students aren’t sensitive to these situations.” This difficulty was already spot lit in the National Plan for the Area of Disability (Moçambique, 2012) which mentions constraints in terms of infrastructure for people with disabilities, lack of adequate buildings, and difficulties in physical access to public spaces.

A fifth subcategory (didactic problems) expresses the difficulty that teachers feel in adapting their educational practices to the diversity of special needs students. Some are finding solutions to teach children from certain groups (the deaf, for example) trying to take advantage of traditional teaching techniques, such as writing up the lesson on the blackboard. Participants mention that “teaching sign language has been very difficult because teachers may even know enough to use sign language, but then it is very difficult to adapt the existing materials that were designed for people without hearing impairment.”

As Sanches and Teodoro (2007) refer, for teachers to be able to teach and for students to be able to learn, “different methodologies or appropriate communication codes are needed, for instance braille for the blind, hand signing communication for the deaf or highly structured and guided lessons for those with cognitive impairment” (Sanches and Teodoro, 2007, p.113).

The scarcity of didactic material and pedagogical resources adequate to these children’s conditions, namely audiovisual materials, which allow pedagogical diversification, represents yet another difficulty. The importance of adapting resources to the needs of students is repeatedly mentioned, for example, in terms of their vocational training, with a view to becoming future productive members of society: “it would be good if the material were suitable for this type of teaching, the same applies to Braille; if books came in digital form…”

Students’ lack of motivation is also a hurdle and corresponds to their lack of incentive to attend school and often leads to drop out. The lack of life prospects and a professional future is identified as one of the most important factors. There are mentions that, from the 7th grade onward, a common question is “why study if there is no work?” Since people with disabilities are not normally seen working, the existence of these workers, even in schools, would be a motivating factor: “(…) do you think we are going to study until we find work? I’ve never seen a blind person working in this province!”

A last subcategory refers to teacher training, this being the item with the most record units and representing, for participants, the main challenge for an inclusive education. The lack of preparation in handling multiple disabilities and intellectual disability (usually less present in schools) was highlighted. As they mentioned, “we teachers should undergo training to learn how to deal with this, how to differentiate and learn to work with children with disabilities.” The need for specific teachers training and guidance in the practice(s) of inclusion is a difficulty mentioned across all focus groups. Although there seems to be commitment and effort on the part of teachers toward upholding inclusive ideas and practices, they are often encounter situations in which they simply do not have the tools and knowledge base to work with.

3.5. Inclusive solutions

The following category explores how teachers look to the future, it addresses inclusive solutions or possible means of overcoming barriers and points out paths in four subcategories.

Despite all the difficulties experienced, participants refer to the importance of having good examples of inclusive practices and being shown exemplary cases of schooling for people with disabilities. Such positive examples (Tomo and Sitoe, 2022) may be important at various levels: as an important means of motivating students and opening up horizons in the future; as a demonstration of good educational and pedagogical practices for teachers; as a reference in terms of pedagogical diversification and adaptation. The CREI (Resource Center for Inclusive Education) is referred as an example of good practices, however, it is deemed insufficient as resources go: “(…) we have the CREI, which offers an inclusive education and there are children with special educational needs, but that institution is not enough, there is a need to expand this inclusive education process in our schools….”

Specialized technical resources are also one of the paths to be developed to facilitate inclusive education, due to their impact in supporting the diagnosis and monitoring of children with different forms of developmental disorders. The creation of multidisciplinary teams, with the participation of other professionals (Franco et al., 2012) can enable an appropriate identification of the requirements and potential of students with special needs and lead to a more rigorous planification of measures and strategies to be implemented, as well as their follow up assessment: “(…) we (currently) lack someone who can provide this assessment and refer this type of child.,” “(…) it is a huge challenge to perform this assessment and figuring how to refer these children, maybe even provide guidance to the parents….”

Community awareness is also a key step for inclusive practices and the defense of the rights of children with disabilities. Awareness should be extended from educational decision-makers and principals out to the entire community, not merely to the “cement” areas, but also to the poorest rural communities. Raising awareness among families about their role is seen as fundamental; in the words of our participants, “Parents should receive a little support in this respect, the school principals should address guardians because there are children being excluded by their own families.”; “(…) raising awareness among parents or guardians in order that these children actually go to schools to have access to education.”

Another subcategory refers to the need for comprehensive training that, in addition to teachers, involves school officials and other elements of the educational system on the national, regional, and local levels. It was repeatedly mentioned that managers often “do not identify with the cause,” raising difficulties toward successful inclusion at the onset. This need for training is also something that should be ongoing: “continuous training with officials, beyond the teachers themselves, managers too, and not only school managers but also service heads who are, for instance, at the district services, in the provincial directorates, these people should be – a lot of hard work needs to be done with these people to allow them to identify with the cause.”

3.6. Training of teachers for inclusive education

The final subcategory again refers to the importance of teacher training in accomplishing inclusion. As we have above, its absence is seen as a critical obstacle, but ways toward improving the situation were also presented. Two subcategories emerge from analysis: the (in)adequacy of curricula and the introduction of special education content and materials, such as those using Braille or Sign Language.

The first item expresses the perceived need to adapt curricula in terms of teacher training and education to include inclusion practices: “(…) there is not as much a need to prepare teachers for (subjects such as) Math, Portuguese, because there are enough already, instead we could be replacing that with these subjects, with topics such as special education.”

On the other hand, participants voice the need for teacher training to integrate Special Education content, including Braille and Sign Language, is expressed: “when it comes to sign language, I try to contextualize more, explain more, but I find it difficult because I do not have training in this specific area.”

4. Discussion

The results obtained from the focus groups of teachers provide us with a panorama of the fundamental aspects of Inclusive Education for children with disabilities in Mozambique, including fundamental needs, advantages, disadvantages, obstacles, and even some clues for improvement going forward. These results, born of individual experience, point to the need for significant changes at different levels of the educational system (Freire, 2008): in the articulation between different systemic actors, in classroom organization and management, adaptation of existing curricula, and, particularly, as concerns aspects of the teaching-learning process.

The first point that should be highlighted is the overwhelming adherence of teachers to the overall principal of inclusion of children with disabilities in schools, as outlined in the Dakar Declaration (UNESCO, 2001) on education for all—a manifesto aligned with the SDG of an inclusive and quality education for all (NESCO, 2015). Inclusion is acknowledged as an important right (Massarongo-Jona, 2013), a paradigm shift, and the product of a long-running journey of awareness promotion and propagation carried out by educational authorities and numerous organizations working in the field. However, the awareness of the inherent value of Inclusive Education needs to be extended to other educational actors, policy- and decision-makers, in fact, to all those responsible for child development in general, as inclusion implies a new perspective of education, a new way of looking at others, the relationship with others and with students in particular (Rodrigues, 2003).

While there appears to be a widespread consensus on Inclusion, what form it might take tends to be divided into the two perspectives that have traditionally prevailed (Florian, 2008): on the one hand, the conception of an inclusive education in which all children work together in the same educational spaces albeit with differentiated pedagogical accompaniment; on the other hand, a special education perspective, privileging the creation of parallel responses (in terms of schools and/or classes) for these children. For the inclusive schools to become a reality, whichever country we may be speaking about, it is necessary that the various Ministries, especially Education, Health and Social Protection, cooperate and contribute toward that goal, and that all those involved in the process (parents, teachers, other professionals, policy-makers, and the community) believe that school is a place for everyone (Costa, 1998).

The “needs and difficulties facing inclusion” is clearly the most prevalent category in this study. These manifest in several forms: some more cultural and related to the way the community and families think about such children; others relate to the limitations of the physical and material resources available to a school system already hard-pressed; still others relate to teachers’ difficulties in promoting truly inclusive educational practices. Despite these difficulties, teachers are keen to point out some possible routes forward and are attentive and concerned about the process. It is also recognized that support outside the school context can be an asset in supporting children with disabilities, parents, and teachers. These services can, however, be provided by special schools, regional or national resource centers, health or protection services, or specialized teams outside school, as is the case in other countries (ADENEE, 2003).

The training and requalification of teachers is one of the most impactful aspects of the situation reported as a widely felt necessity and one of the core aspects for the educational transformation with a view to effective inclusion (Chambal, 2012; Mahalambe et al., 2019). This would encompass training toward inclusive practices at the level of the teaching-learning process, classroom communication between teachers and students with disabilities, the adequacy of educational practices with regard to diversity, and the need for awareness work to encourage acceptance and implementation of the inclusion process. This study’s results are in line with those of Mariga et al. (2014) in that they underline that the key to successful inclusive education in low-resource countries is teacher training, along with the adaptation of spaces and learning environments in schools, education of parents, community members, and professionals hand in hand with the various services involved. The importance of teacher training is also underlined by Armstrong and Rodrigues (2014), in terms of forms and models of training, educational strategies, and contents. According to a study by Trust (2016), although there are already teacher training programs with specific contents to work with children with disabilities in some African countries, they have not yet been given the projection and prominence required to ensure that enough teachers obtain the skills necessary to meet the needs of inclusive education.

There is a way yet to travel for schools to offer truly inclusive and quality education for all. There are still discrepancies between the legislation in effect and what is observed in many schools. Despite being the appropriate place for the socialization and insertion of children with disabilities, schools do not seem prepared yet to work with the diversity of students they host. It is clearly a priority to encourage and promote inclusive training, for the various actors in the educational scene, so that inclusive education in Mozambique follows the same path that is being taken worldwide (Florian, 2008).

5. Conclusion

The results obtained in this study underline that teachers are fundamental elements in the construction of inclusive education and these seem to be informed and sensitized to the access of children with disabilities to education. They consider inclusive education to be a fundamental change that is already taking its first steps. However, the right to education of children with disabilities does not always correspond to the concept of educational inclusion different from special education. Although the concept of education for all is highly valued.

With regard to our second objective (to identify the needs, obstacles, and difficulties felt by teachers in the process of including children with disabilities), they underline that, first of all, the entry of these children into school requires a broader awareness on the part of parents and the community. In addition, there are many obstacles and needs in terms of the teacher-student relationship, the physical spaces of schools, materials, and resources. Teachers point out the need of better infrastructure (buildings and equipment) to enable proper and functional access. They also highlight other difficulties, from motivating families and students, to teaching materials and educational practice in general. For this educational practice to be effectively inclusive, the teachers training is crucial and a priority in whatever strategy is employed for the progressive inclusion of children with disabilities in Mozambican schools.

As for the third objective (to identify the resources, methods, practices, and strategies used in the process of including children with disabilities), this was the one that the teachers felt the greatest difficulties with, but the importance of examples of good practices is underlined.

6. Study limits and future research

Through this study, we sought to explore teachers’ perspectives on the constrictions upon widely adopting inclusive education in Mozambique. However, we worked with a limited convenience sample, including only teachers from three urban centers, and future studies should address a larger territorial area, including listening to teachers outside cities, where teaching conditions are sometimes quite rudimentary. For a deeper and more diversified understanding of the issues involved, it would also be important to listen to other groups, such as decision-makers within the educational system, professionals working with children with disabilities, other members of the school community, and, especially, families, combining qualitative and quantitative studies. Efforts will also be needed to gather comprehensive and reliable data on the real number of children with disabilities in Mozambique, their characterization, and their living conditions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This paper is financed by national funds from FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, IP, within the scope of the project UIDB/04312/2020.

Acknowledgments

We thank UNICEF Mozambique and MINEDH-Ministry of Education and Human Development of Mozambique for allowing us to collect the data, and Adelina Branco for the cooperation in data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ADENEE (2003). Special educational needs in Europe. Brussels: European Agency for Development in Special Educational Needs.

Armstrong, F., and Rodrigues, D. (2014). A Inclusão nas Escolas. Lisboa: Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos.

Booth, T., and Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for inclusion, developing learning and participation in schools. England: CSIE Mark Vaughan.

Brás, A. P. D. S. (2020). Perceção dos professores sobre a inclusão de alunos com necessidades de saúde especiais numa escola portuguesa em Maputo, Moçambique: apoios e recursos (Unpublished master’s thesis) Instituto Politécnico de Viseu.

Chambal, L. A. (2011). As políticas de inclusão escolar em Moçambique e a escolarização dos alunos com deficiências, Uma trajetória de pesquisa (Conference session) IX Congresso Nacional de Educação. Educere, Curitiba, Brasil. https://docplayer.com.br/16563943-As-politicas-de-inclusao-escolar-em-mocambique-e-a-escolarizacao-dos-alunos-com-deficiencias-uma-trajetoria-de-pesquisa.html

Chambal, L. A. (2012). A formação inicial de professores para a inclusão escolar de alunos com deficiência em Moçambique.. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo.

Chiziane, E. L. (2009). A perceção do corpo diretivo e alunos comNecessidades Educativas Especiais sobre o papel do Psicólogo Escolar no Contexto da Educação Inclusiva: Estudo de Caso Escola Secundária Josina Machel, Trabalho de diploma. Maputo: Universidade Pedagógica

Cossing, A. O. (2006). A situação actual do diagnóstico psicopedagógico na escola especial e desafios para o futuro: Estudo de caso da Escola Especial n° 2. Trabalho de diploma. Maputo: Universidade Pedagógica.

Costa, A. M. (1998). Uma Educação Inclusiva a partir da escola que temos. In CNE. Uma Educação Inclusiva a partir da escola que temos, Conselho Nacional de Educação, 25–36.

Florian, L. (2008). Inclusion: special or inclusive education: future trends. Br. J. Special Educ. 35, 202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00402.x

Franco, V., Melo, M., and Apolónio, A. (2012). Problemas do desenvolvimento infantil e Intervenção Precoce. Educar em Revista, 43, 49–64

Freitas Pacho, L. E. S., and Zimbico, O. J. (2022). O professor face ao currículo, diversidade e inclusão em Moçambique the teacher facing curriculum, diversity and inclusion in Mozambique. Braz. J. Dev. 8, 50966–50973. doi: 10.34117/bjdv8n7-152

Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A. (2000) Focus group: a practical guide for applied research. London: Sage Publications.

Lopes, B. D., Francisco, F. E., Francisco, V. F. M., and Dinis, T. F. (2020). Educação inclusiva em Moçambique: um olhar crítico sobre as variáveis de sucesso. Revista Onis Ciência. VIII, 25:17–29.

Mahalambe, F. M., Cossa, J., and Leite, C. (2019). Estudos sobre formacao inicial de professores em Mocambique e sua Relacao com as politicas de formacao de professores (2012-2017). Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 27:149. doi: 10.14507/epaa.27.4250

Mariga, L., McConkey, R., and Myezwa, H. (2014) Inclusive education in low-income countries: a resource book for teacher educators, parent trainers and community development corkers. Cape Town: Atlas Alliance and Disability Innovations Africa.

Massarongo-Jona, O. (2013) Revista de Direitos Humanos-Volume 2, n°2. Direitos da Pessoa com Deficiência. Maputo: Faculdade de Direito Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Centro de Direitos Humanos.

Moçambique (2012). Plano Nacional da Área da Deficiência – PNAD ll 2012–2019. Maputo: República de Moçambique.

Moreira, P. C. (2007). Ensino Especial: A construção de práticas inclusivas junto a docentes da escola pública. Revista da Faculdade de Educação, 7/8, 29–52.

Nhapuala, G. A. (2010). A prática docente no contexto da educação inclusiva: estudo de caso da Escola Secundária Josina Machel (Unpublishes master’s thesis) Universidade Pedagógica.

Nhapuala, G. A. (2011). A educação especial no contexto da educação inclusiva: Desafios e Oportunidades. Revista Udziwi, 6, 26–30.

Nhapuala, G. A. (2014). Formação psicológica inicial de professores: atenção à educação inclusiva em Moçambique. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) Universidade do Minho.

Okyere, C., Aldersey, H. M., Lysaght, R., and Sulaiman, S. K. (2019). Implementation of inclusive education for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in African countries: a scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 41, 2578–2595. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1465132

Phasha, N., Mahlo, D., and Dei, G. J. (2017). Inclusive education in African contexts – a critical reader. Amesterdam: Sense Publishers.

Prata, M. (2009) Estudo das ideias e das práticas dos professores do 1ºCiclo do Ensino Básico acerca da inclusão educativa de crianças com necessidades educativas especiais. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidade do Porto.

SADC. (2017). Estratégia de Educação Inclusiva para alunos com. Deficiência na África Austral (SAIES) 2017 - 2021. SADC.

Sanches, I., and Teodoro, A. (2007). Procurando indicadores de educação inclusiva: as práticas dos professores de apoio educativo. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 20, 105–149.

Sant’ana, I. M. (2005). Educação Inclusiva: Concepções de Professores e Diretores. Psicologia em Estudo 10, 227–234. doi: 10.1590/S1413-73722005000200009

Silva, M. D., Ribeiro, C., and Carvalho, A. (2013). Atitudes e Práticas dos Professores Face à Inclusão de Alunos com Necessidades Educativas Especiais. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, 47-I, 53–73.

Terenciano, F., and Gerente, B. (2018). A percepção dos professores primários sobre a educação inclusiva na cidade de Pemba, Moçambique. Revista Educação-UNG-Ser, 13 Revista Educação-UNG-Ser, 69–83.

Tomo, C. D., and Sitoe, A. A. (2022). Response to intervention model as a tool for fostering inclusive education in unprivileged contexts: a pioneering case study in Mozambique. Am. J. Appl. Psychol. 11, 74–83. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20221102.15

Trust, E. D. (2016). Eastern and southern Africa regional study on the fulfillment of the right to education of children with disabilities. New York: UNICEF.

UNESCO (1994). Salamanca declaration and framework for action in the field of special educational needs. Salamanca: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2015). Education for all 2000–2015: Achievements and challenges; EFA Global Monitoring Report. UNESCO.

Ussene, C., and Simbine, L. S. (2015). Education for All 2000-2015: achievements and challenges; EFA Global Monitoring Report. UNESCO.

Vala, J. (1986). “A Análise de Conteúdo” in Metodologia das Ciências Sociais. eds. A. Santos Silva and J. Madureira Pinto (Porto: Edições Afrontamento), 101–128.

Keywords: inclusive education, disability, SDG, teachers, Mozambique

Citation: Franco V (2023) School inclusion of children with disabilities in Mozambique: The teachers’ perspective. Front. Educ. 8:1058380. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1058380

Edited by:

Maria Luísa Branco, University of Beira Interior, PortugalReviewed by:

Ángel Freddy Rodríguez Torres, Central University of Ecuador, EcuadorSuharsiwi-Suharsiwi, Muhammadiyah University of Jakarta, Indonesia

Copyright © 2023 Franco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vitor Franco, dmZyYW5jb0B1ZXZvcmEucHQ=

Vitor Franco

Vitor Franco