- 1Facultad de Educación, Universidad Autónoma, Santiago, Chile

- 2Faculty of Education, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

This article presents an analysis of a dean’s early efforts to encourage reflective practice in the teacher education practicum, in consultation with a critical friend. The focus is on the importance of listening and the identification of assumptions underlying practices. The authors met in 2010 in a week-long seminar focused on the practicum in teacher education programs at a university in Santiago, Chile. A long conversation over dinner one evening revealed a significant interest in each other’s perspectives and experiences. Since that time, more than 20 opportunities to visit each other in Chile and in Canada have established an on-going connection for sharing insights as they emerge from experiences in each other’s country. The authors now consider themselves to be life-long critical friends. In April 2021, Rodrigo was appointed as Dean of Education at Universidad Autónoma in Santiago, with an early focus on encouraging reflective practice by all who are involved in the teacher education practicum—student teachers, mentor teachers and faculty supervisors. Tom retired in 2019 after 42 years in teacher education practice and research at Queen’s University, and he continues to explore the complex issue of how people learn to teach.

1. Introduction

Following our fortuitous meeting in 2010, our earliest collaborations involved an international conference in Chile, a seminar in The Netherlands, and Tom’s earliest visits to several universities in Santiago and La Serena. These were Tom’s opportunities to begin to understand educational contexts in Chile and to develop a sense of how he might contribute in small ways to the development of teacher education programs, always with special attention to the duration and placement of practicum periods in programs that run for four or 5 years after completing secondary school. Traditionally in Chile, the practicum experiences of student teachers develop slowly and culminate in an extended period of part- or full-time experiences in the final year.

Tom’s numerous trips to Chile between 2014 and 2019 provided opportunities to extend our friendship by discussing how various audiences were responding to his presentations. Then, over four consecutive program years (2015–2016 to 2018–2019), Rodrigo observed all of Tom’s physics methods classes (live by Skype or subsequently by videorecording) and attended two classes in person each year. In most instances, these observations and visits were followed by discussions of students’ responses to Tom’s teaching and by discussions of differences between Tom’s practices and typical teacher education practices in Chile. Thus our critical friendship (Fuentealba Jara and Russell, 2022) has been enriched by many observations of each other’s practices and many discussions of the assumptions that support them. In the following sections we summarize and illustrate efforts to promote our shared perspectives on two significant issues in teacher education—reflective practice and the practicum.

2. Perspectives on reflective practice in teacher education

During our extended critical friendship, Rodrigo has emphasized the importance of identifying one’s underlying assumptions—the lines of thought (of which we are often unaware) that are implicit in our actions as teacher educators. Argyris and Schön (1974) explored the differences between espoused theory (what we say we do) and theory-in-use (what our actions imply). The persistent challenge involves identifying the assumptions implicit in our actions and then asking if our espoused theories are consistent with our practices. We share the view that learning from experience is at the heart of reflective practice. Schön’s (1983, 1987) account of reflection-in-action involves learning in the moment of action, when a surprising, puzzling or unexpected response to one’s actions generates a new perspective on a situation. The new perspective can then be tested by evaluating the impact of actions that it suggests.

Rodrigo believes that discussions with a critical friend have enabled him to better understand what he has learned from each situation that they discuss. Our longstanding discussion of reflective practice helps him to identify assumptions underlying familiar and new practices and encourages him to take risks that change his more traditional patterns of interaction. Sharing experiences typically leads to analysis as well. Both Rodrigo and Tom have deepened their understanding of reflective practice through this critical friendship.

2.1. Promoting reflective practice with faculty and teacher education students

Rodrigo is acutely aware of typical expectations that a dean will tell others what to do or make judgements of how well others are performing their duties. He has taken a significantly different stance, elements of which are described in his own words in the following statements:

• Asking colleagues and students to tell me about events or situations that are puzzling or unexpected creates opportunities to collaboratively discover alternative practices. This is in contrast to common and expected practices whereby a dean or department head will ask only about the results achieved. Rather than promoting research or the practices of others, I prefer to analyze the practices that I am using myself in our conversations.

• In addition, I have deliberately avoided imposing my personal point of view in meetings with colleagues, a practice that tends to close off discussion. Alternatively, I listen to different points of view, with special emphasis on listening and encouraging all who are present to contribute.

• Asking colleagues how they listen to and collect evidence from their students has become an important question. I also ask how and why they are taking risks and evaluating the results by giving voice to students in response to a new practice.

All who have worked to promote reflective practice in teacher education programs will know that the task is challenging. Doing so in his first year has generated for Rodrigo both smiles and tensions, as data that follow illustrate.

3. Perspectives on the practicum in teacher education

The authors have come to see practicum experiences as the centrepiece of any teacher education program. Many teacher education programs delay until late in the program any significant opportunities to act in the role of teacher under the guidance of a mentor teacher. Students in a teacher education program have extensive experience learning from books, lectures and familiar classroom activities. These same students also have extensive experience of everyday learning, where errors are common but often corrected over time and through interaction with others. Significantly, students in a teacher education program have extensive experience learning the actions of teachers by observing them during many years of primary and secondary schooling. However, during those years, they have had no access to teachers’ reasons for acting as they do when teaching. Students also lack any preparation for learning from personal experience the professional knowledge of teaching (Munby et al., 2001). Thus we believe that those learning to teach need much more support than is typically provided by a mentor teacher or a faculty supervisor who observes and offers suggestions for change, often without exploring rationales and underlying assumptions. Support for reflective practice framed as reflection-in-action would be a significant element in such support (Russell, 1993, 2005).

3.1. Promoting reflective practice in the practicum

Promoting reflective practice is not a matter of telling others what to do. Here Rodrigo has adopted two important strategies that may seem counter intuitive. One involves listening rather than telling, and this is just as true for meetings with students and teachers as it is for meetings with faculty. A second strategy involves teaching indirectly by modeling reflective practice. Rodrigo captured some of this in the following statements:

• Students are reacting positively to meetings in which I focus on two questions: (1) What changes would you like to suggest for the supervision of your practicum experiences or for the way we are teaching your classes in the university? and (2) What changes are you trying to make in your practicum placements, why are you making them, and how are you collecting evidence about their effects?

• Personal visits to schools where students are practicing have been particularly valuable, as I meet with the student, the supervisor and the mentor teacher. This provides me with views of learning from experience and trying to assist and improve that learning by the students. It also provides an opportunity to model alternative approaches to observing students in action and discussing their practices and their impact on the students they are teaching.

The preceding data serve as an introduction to some of Rodrigo’s experiences in his first year as a Dean who is always aware that he is acting in some unexpected ways with a view to encouraging others to take risks themselves by exploring new practices. The next section introduces his new practices.

4. New practices in the first year as dean

4.1. New practices with faculty members and students

Rodrigo always inquires into issues or moments of practice that are considered unusual or puzzling. In many instances this has allowed us to discover alternative responses. In the Chilean context. it is common that the question is referred to what resulted, or how the plan was fulfilled. Another aspect that I have been able to observe in meetings or conversations with peers is the permanent listening, considering different points of view, not only imposing my point of view. Another point is related how they collected evidence with the students when they do something new in the practices, or how they give voice them, and contrast with the own view. It has also been important to emphasize with my peers the analysis of my own teaching practices more than the analysis of the practices of others.

4.1.1. A conversation with final year special education students

In a 45-min meeting with 25 special education students, Rodrigo posed questions about the quality of their professional learning in the practicum and in their classes at the university. From a cultural perspective, it would have been normal for him to give a lecture. In contrast, he opted to pose questions, asking them to discuss their responses in small groups, and then to write each group’s responses on blackboards. This strategy was in part inspired by Rodrigo’s observations of Tom’s classes by Skype and video recordings several years ago. While Tom was pleased to have Rodrigo as a critical friend for discussions of his classes, Tom realizes now that the experiences also suggested new possibilities to Rodrigo.

4.2. New practices in the practicum context

Unlike previous deans, and unusual in terms of expectations of a dean, Rodrigo has participated occasionally in supervision of the practicum, thereby having direct contact with students in their schools. He has also asked students about the aspects of supervision practices or university classes in which changes might improve the quality of their learning. At the same time he has inquired about practices that they would like to change in their own teaching. He is pleased to have had the opportunity to follow a complete cycle of supervision—meeting first with the students and the supervisor, then visiting the practicum classroom, and then participating in the conversation between the supervisor and the future teacher after the observation. He believes that modeling in these contexts can be a strong strategy for engaging others in conversations about practice.

4.2.1. A conversation with a practicum coordinator who also supervises students

Some individuals stand out from the norm that sees practicum coordinators staying in their offices. One female practicum coordinator made it clear that she was happy to also do supervision of students. She explained to Rodrigo that she had taught in schools before moving to university teaching and could make better decisions by being in contact with teacher candidates. She did not want to wait to hear problems from other supervisors. Some students have to travel long distances every day, so she made a map of their homes and assigned them to schools near a bus terminal. She also put more than one or two students in the same school, where five or more students in a school made meetings more productive; the same strategy worked with mentor teachers. She told Rodrigo that when students talk in a group, they feel more comfortable discussing classroom problems and are less concerned about being evaluated when not alone in a school. While it is common in Chile for practicum coordinators to speak only with school principals, this coordinator was eager to speak with both teacher candidates and mentor teachers. This parctice is one that Rodrigo would like to see other coordinators take up.

4.3. Conversations with a critical friend

Keeping in mind the question “What have I learned from the situation that I am sharing?,” Rodrigo’s exchanges with Tom as critical friend have encouraged and supported openness to taking some risks, changing some traditional practices and, after doing so, sharing and analyzing the responses together. Frequently, our conversations explore the differences between our two cultures to ensure that taking risks and interpreting responses are culturally sensitive and responsive.

5. Learning by listening and Progress To date

This section is presented in Rodrigo’s first-person voice.

Hagger et al. (2008) have suggested that the central question is not How do future teachers learn?, but How do future teachers learn from a specific person in a specific context? This adjustment has allowed me to make the mentor teachers in schools visible at the same time that I have looked for spaces for these practices to be shared. Thus, I have been creating opportunities for conversations among mentor teachers, interns and supervisors.

One supervisor pointed out that “by creating this space for the exchange of practices, I could not help but be amazed at the number of ideas that emerged, things that we could have said in classes at the university.” In those exchanges the students became aware of the significance of ideas. We all learned that there is more than one way to resolve a situation in practice. Of course, a teacher with experience may see a situation as simple, but those who are learning to teach do not have the experience that suggests ways to solve problems.

Generating opportunities in the university to share and explore what happened in practice has been an important development during this period. Traditional practice involves meetings with a university supervisor who is focused on addressing theoretical aspects, often decontextualized from what the students have experienced in their practicum classrooms. In that sense the meetings were more about presenting a problem and then the teacher approached it theoretically. As evidence of the shift in practice, the students in their work sessions at the university first share their practicum experiences in small groups and then the professor works from a matrix that we agreed (with the Dean’s encouragement) to use that would allow us to have evidence regarding what the future teacher is learning in the practicum. At the same time, this has generated inputs so that supervisors can be clear about how they can help the students.

We have been making progress with our students in understanding that practice is much more complex than just applying what is learned in the classrooms of the university. I have learned the value of collaborative work, which means avoiding a speech, but rather modeling from work in the university classroom, as well as exchanges between students from different locations. We are challenged to create more spaces for exchanges between the supervisors working in the same program. A supervisor from one of our three campuses pointed out that “I had not realized that listening to my colleague from that campus would allow me to solve a problem for which I had not found a solution.” His peer from his own campus responded by saying “I did not imagine that what I do frequently would serve as a model for another campus. We need more spaces to share our experiences.”

5.1. A dean’s example of the potential of listening

This section is also presented in Rodrigo’s first-person voice.

When students from fourth year of the English program asked me, “Do you have time to talk about something?,” I said “Yes.” One student continued with this explanation:

You know that we are in our fourth year and starting our professional practice, and with other friends we have the opportunity to connect with a big city where there are many schools, and we know people who work with the mayor. We wanted to share this with you, because it could be a good idea if we can teach there.

She went on to say: “We knew it was possible to talk with you, and this is a real opportunity. I do not know if you agree with us.” I responded: “Thanks for talking with me about this idea, I think that is a great opportunity to show how we are doing initiatives together.” I started to see a smile on her face and she added: “Really, it is not a problem?” “Of course not,” I said, “if you agree we can go together to talk with the head of education there.” She added: “Really, great, because you said that it is necessary to take some risks, and here we did, because never before in our program have we had the opportunity to propose something like this.”

It was a good discussion, and quite interesting to see the future teachers taking a risk when they had the opportunity, because this is uncommon. Placements are organized top-down, and students go to the school where the practice coordinators assign them. University classes often speak about a collaborative approach to teacher professional development, but we do not necessarily work that way. Here was an opportunity to collaborate with students. One of our Faculty’s challenges involves the fact that we prepare future teachers, but when we take decisions we tend to treat the future teachers as students in schools, not as persons who need to learn to think like a teacher. When I review my discussion with the students, I can see how important it is to not treat them like children or secondary school students. The further challenge is how to encourage colleagues to share our questions and issues to give a real opportunity for future teachers to think like a teacher.

5.2. Problems and challenges

In the 5 years prior to Rodrigo’s arrival at Universidad Autónoma, the Faculty of Education had two other deans. Inevitably, the arrival of a third dean provoked resistance in some of the academics who have been in the Faculty of Education for a long time. Initally, some understandably questioned whether issues that yet another new dean identified would persist over time: “Is it worth the effort to try to change if he is only here for a short time?” Thus some issues could be ignored as the personal interests of a new authority who might soon be replaced. This attitude was illustrated in comments such as: “Dean, do not worry, I can tell you how things are done here, I’ve been here longer and I’ve seen that this works.”

Comments from some of the practicum internship coordinators illustrate the challenge of moving forward with changes to practicum practices, as the following statement indicates:

Dean, your proposal is very interesting, but over the years I have been here, I have noticed that the best thing for the operation of the internships is to not lose sight of the fact that in the end we are the university supervisors who have the authority to indicate what the student should or should not do in practice. For this reason, the school teachers must allow the interns to do what we as the supervisors have asked them to do.

A statement such as this makes it difficult to explore changes to the relationship between mentor teachers and the students assigned to them. Such a statement also raises challenges about learning from our experience to make improvements. How and when do we learn from our own practices and from our mistakes? Creating more discussion spaces between the supervisors of the same program at different campuses could be helpful. Drawing from Tom’s experiences with self-study research, Rodrigo has developed a group of teacher educators who are exploring self-study of their own practices. Typically, the goal is to identify and reduce gaps between teacher educators’ good intentions and the real learning of future teachers. The challenge for Rodrigo is to promote analysis of teacher educators’ assumptions to make them explicit as they seek to improve the quality of professional learning in practicum placements.

6. Taking a risk: Requesting feedback about the first year as dean

Shortly after completing his first year as Dean, Rodrigo decided to take a risk by sending two questions to heads of departments on all three campuses and asking individuals to respond anonymously by sending their responses to his secretary. Twelve responses were received, providing an intriguing range of opinions from supportive to uncertain.

6.1. Department heads’ responses to two questions

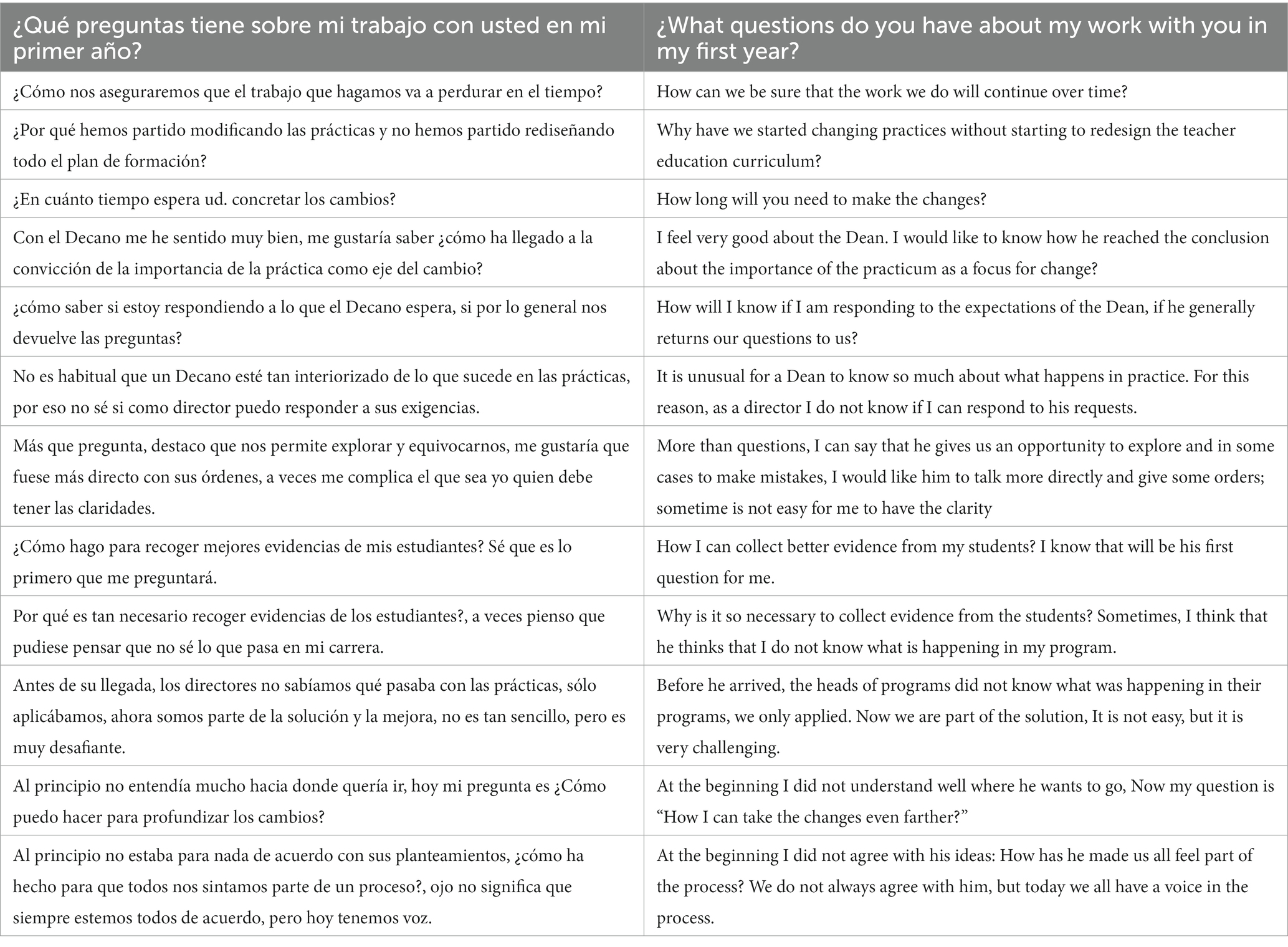

Table 1 presents responses when Department Heads were asked for questions about his work with them during his first year as Dean. The diversity in the responses is intriguing and not unexpected. When attempting a different style as a Dean, some individuals will respond in positive ways while others will cling to their previous expectations. While one individual asks how to collect evidence from students, another asks why evidence should be collected. While one is ready to make changes, others ask why they are changing and how long it will take. While one is impressed that the Dean knows a lot about the practice context, another asks why the practicum is the focus for change? Being aware of these differences is a crucial step in planning further efforts to encourage an approach involving risk-taking, analysis of practices and increased attention to the role of the practicum.

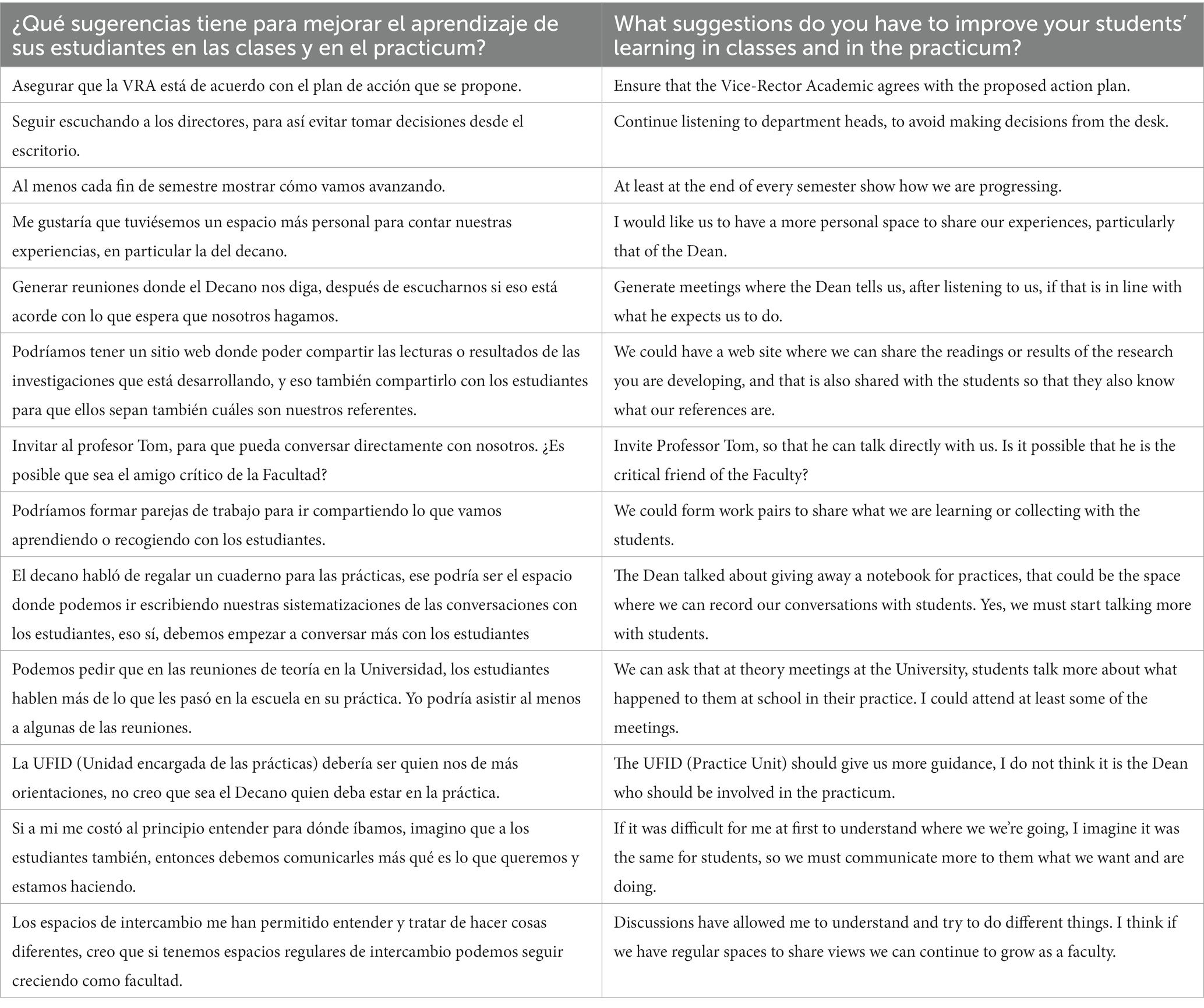

Table 2 presents the responses of the same individuals to a request for suggestions for improving students’ learning. The responses seem to speak more positively to what Rodrigo has been doing by encouraging and supporting discussions between himself and the department heads and between faculty and students. Suggestions offer ways to enhance what has been achieved so far. Not surprisingly, there is a suggestion that higher levels of administration need to be approving what their new Dean has been doing. Another suggestion that the Dean need not be involved in the role of the practicum in the various programs also confirms the power of traditional expectations within the culture of schools and universities (Sarason, 1971).

Tables 1, 2 include the original Spanish and an English translation. We expect this article to be read by Chilean academics, including those who responded anonymously. For their benefit, it is important to provide the original statements as well as the translations. From the perspective of the credibility of these responses, we find them trustworthy because the responses were anonymous, are clearly not one-sided and express a range of opinions. From an ethical perspective, we believe that those who contributed cannot be identified from these data; Rodrigo himself is in a more vulnerable position, making his early experiences as Dean open to those he is hoping to lead in productive new directions.

6.2. Rodrigo’s reactions to responses from the heads of departments?

Here again, Rodrigo speaks personally about his responses to the anonymous comments and suggestions presented in Tables 1, 2.

After reading the responses, my first reaction was one of surprise and expectation. I say surprise because in many times talking with Tom about how to ask questions without making them feel the influence of my position, they gave a more political response instead of describing how they feel in this new context. I also say surprise because when we opened spaces for sharing and listening, it seemed possible to develop a deeper relationship with members of Faculty, because when they asked me questions, they also discovered more about their own assumptions about how teachers learn. For example, in terms of the tension about how we make decisions to improve the program for future teachers, I was trying to promote some changes, such as the need to collect evidence from the future teachers, not only about how they are thinking and doing, but also about how our formative actions are helping them to solve problems or situations in ways that help them think and act like a teacher.

I was also surprised by how the heads seemed to want me to agree with them, but at the same time, I felt eager to know what they are thinking about my work as Dean. I immediately remembered that this situation was similar, in another context, to Courtin’s (2017) classroom experience because I was concerned about what the heads might be thinking in terms of their approval of my work rather than about how we could improve our practices as teacher educators. Another interesting point concerns how we develop and improve our learning from experience. Many of the heads have come to expect that every new Dean wants to do some things differently, and so the challenge is to find ways that we can live new experiences together to create the possibility to change our habits and share the challenges of doing so. This point made me think about how we could generate spaces for modeling new experiences directly more than from my desk.

6.3. Rodrigo’s sense of ways forward

Two strategies that Tom recently suggested (Russell, 2022) for encouraging reflective practice could be helpful.

“Listen frequently and carefully for instances of reframing of assumptions about teaching and learning.”

This strategy is central, because it means being clear that the challenge is not just to reframe for the future teachers, it is a process of double-loop learning (Agryris, 1991) that teacher educators themselves need to do explicitly to understand better what they are doing in their teaching practices. Sometimes reframing means assuming risks; Schön (1971, p. 31) argued that all our actions are usually oriented to maintaining stability in the educational system:

The resistance to change exhibited by social systems is much more nearly a form of ‘dynamic conservatism’ - that is to say, a tendency to fight to remain the same. So pervasive and central is this characteristic that it distinguishes social systems from other social groupings.

Rodrigo’s focus has been on finding ways to encourage others to risk making changes while trying to demonstrate doing the same himself.

“Model reflective practice in the teacher education classroom.”

It is not easy to teach something that we have not experienced ourselves. The challenge for Rodrigo, then, is how to do his own analysis of his practices explicitly and at the same time assume some risks for changes or be more explicit about why he is trying to lead in these ways. This means that he must be a leader with strong connections to teacher education practices.

6.4. The evolving nature of a critical friendship

We are grateful to reviewer 5 for raising several questions about how our critical friendship has evolved:

If the authors were to add something to the work, I would like them to discuss the progression of their collaboration over the years and any turning points they encountered …. Was there any learning that could only happen face-to-face? Did virtual conversation promote the discussion of certain topics that face-to-face conversation might not have? Also, what knowledge was uncovered through relational knowing that might not have otherwise surfaced? … The inclusion of a few sentences of this nature would be appreciated by readers wanting to nurture inter-institutional, international partnerships/collaborations over the continuum. (Reviewer 5)

There have indeed been significant moments in the 12 years (2010–2022) of our critical friendship, and the following statements extend the brief account given in the Introduction. We both realize that we seemed to trust each other from our first meeting. In the first few years, connecting with each other’s families made an important contribution. As Rodrigo facilitated Tom’s visits to various universities in Chile, he was always there to support, to explain puzzling moments, and to encourage risk-taking. A sense of humour also helped. As Rodrigo came to understand self-study methodology, he made the organizational connections to facilitate its introduction in Chile in Spanish. Sharing the personal as well as the professional has been invaluable, and today there is little that we would not share with each other; writing conference papers and articles together has also helped. Taking an interest in all aspects of each other’s work and offering constructive suggestions have also helped. Rodrigo’s watching Tom’s physics methods classes for 4 years, discussing many of them and visiting two classes each year in person, paid huge dividends for both of us—for Tom immediately, as he gained new perspectives on his students’ participation, and for Rodrigo in the longer run, as he translated his learning from observation into new actions as a Dean. When Rodrigo was considering the invitation to assume his current position, Tom was the person he could consult with in complete privacy. A critical friendship must never be taken for granted, and it is valuable at intervals to view it from a metacognitive perspective to better understand and ultimately to improve it. Numerous opportunities to visit each other in person have made more productive the virtual conversations that fill the gaps between visits.

7. Discussion and conclusion

Overall, Rodrigo sought to foster reflective practice by encouraging and modeling practices that his colleagues could adopt in their work with those learning to teach. He has generated opportunities for faculty, students and mentor teachers to listen to each other’s points of view on the practicum and its role in students’ development as beginning teachers. His focus remains on the role of the practicum in various programs, although reflective practice is an important focus throughout preservice teacher education programs. Rodrigo is mindful of the problem captured in the following quotation:

Educational research is not an end in itself but a means to the end of finding richer and more complex meanings in classroom teaching. The focus must always be on the quality of learning for each school’s students, and this focus can become central when teachers sense coherence, collaboration, and cooperation in their daily professional lives. (Russell and McPherson, 2001, p. 13, emphasis in original)

The challenge Rodrigo has taken on is to gradually develop an organizational climate characterized by the words emphasized above, a climate in which teacher educators and their students “sense coherence, collaboration and cooperation in their daily professional lives.” He seeks to develop an environment in which individuals listen to each other and offer possible solutions to improving the quality of students’ learning. He credits his reframing of his own practices as he processed his observations of Tom’s classes, in which different viewpoints were encouraged rather than criticized as incorrect or inadequate and in which seeking alternatives encouraged a professional development culture. After 1 year as Dean, this remains both a goal and a significant challenge. The feedback received thus far suggests that some progress has occurred and much more effort remains.

Listening has been a central theme in Rodrigo’s efforts in his first year. Some of the comments received illustrate the familiar expectation that a dean will tell people what they are expected to do. Rodrigo has deliberately tried to avoid this expectation by posing questions that will help him to understand individuals’ current assumptions and expectations. Modeling is a subtle but powerful way of teaching; in contrast, merely telling people that they are expected to be reflective about their practice has rarely been successful. It appears that it is also important to make a metacognitive turn to be more explicit about the assumptions underlying new and perhaps unexpected practices. Patience and persistence have been critically important. Rodrigo is working to shift a long-established culture in which deans give directions to faculty and, in turn, faculty give directions to students and mentor teachers. Those who know more or have more authority give direction to those who are assumed to know less. Reflective practice involves a unique and alternative set of assumptions and actions with different premises about how and how well individuals learn from experience. Cultures change slowly, but changes can occur as individuals take risks and see the benefits of new actions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. (1974). Theory in Practice. Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco Jossey-Bass.

Courtin, B. (2017). An Account of My Practicum Experiences. Unpublished manuscript, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON.

Fuentealba Jara, R., and Russell, T. (2022). “Collaborative learning from experience across cultures: critical friendship in self-study of teacher education practices” in Learning through Collaboration in Self-Study. eds. B. M. Butler and S. M. Bullock (Singapore: Springer)

Hagger, H., Burn, K., Mutton, T., and Brindley, S. (2008). Practice makes perfect: learning to learn as a teacher. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 34, 159–178. doi: 10.1080/03054980701614978

Munby, H., Russell, T., and Martin, A. (2001). “Teachers’ knowledge and how it develops” in Handbook of Research on Teaching. ed. V. Richardson. 4th ed (Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association), 877–904.

Russell, T. (1993). Reflection-in-action and the development of professional expertise. Teach. Educ. Q. 20, 51–62.

Russell, T. (2005). Can reflective practice be taught? Reflective Pract. 6, 199–204. doi: 10.1080/14623940500105833

Russell, T. (2022). One teacher educator’s strategies for encouraging reflective practice. Front. Educat. 7:1042693. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1042693

Russell, T., and McPherson, S. (2001). “Indicators of success in teacher education: a review and analysis of recent research” in Report prepared for the Pan-Canadian Education Research Agenda Symposium on Teacher Education/Educator Training Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2511254/Indicators_of_success_in_teacher_education

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York Basic Books.

Keywords: reflective practice, practicum, critical friend, assumptions, listening

Citation: Fuentealba Jara R and Russell T (2023) Encouraging reflective practice in the teacher education practicum: A dean’s early efforts. Front. Educ. 8:1040104. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1040104

Edited by:

Celina Lay, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mary Frances Rice, University of New Mexico, United StatesStefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United States

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Fuentealba Jara and Russell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tom Russell, dG9tLnJ1c3NlbGxAcXVlZW5zdS5jYQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Rodrigo Fuentealba Jara

Rodrigo Fuentealba Jara Tom Russell

Tom Russell