- 1School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

This scoping review is the first of three publications that are part of a research project funded by the Queensland Department of Education through their 2021 Horizon Grant funding scheme. This scoping review provides an analysis of contemporary literature that identifies approaches currently being used by educators to successfully engage with culturally and linguistically diverse and Indigenous students, families, and their communities to increase their cultural capabilities. A systemic selection process delivered 21 articles that were included in this Scoping Review. The first four Stages of the study identify and discuss four common areas in which educators can improve cultural capabilities: (i) eldership; (ii) connections; (iii) relationships; (iv) practice. In Stage 5 aspects of these four areas are analyzed in a series of case studies along with an in-depth summary of the literature presented in the scoping review. The literature from this scoping review will inform an engagement strategy that will help improve upon the cultural capabilities of educators working with students in Australian South Sea Islander Communities.

Introduction

Australian South Sea Islanders are people of Pacific Islander ancestry and are descendants of South Sea Islanders brought to Australia in the late 19th Century, primarily as laborers to work in the sugar cane industry. They came from Melanesian countries of Vanuatu, New Caledonia, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. The Australian South Sea Islander community has a unique cultural heritage that is influenced by their islands of origins and their lives in Australia. They have faced discrimination and marginalization since their arrival, despite sustained efforts to recognize and address their historical and ongoing experiences of injustice (Bobongie-Harris and Fatnowna, 2023).

The overarching study is grounded in Critical Race Theory (CRT) and how CRT relates to improving cultural capabilities of teachers. Critical Race Theory is a framework that examines the ways in which race and racism intersect with social, cultural, and economic power structures (Applebaum, 2010; Gillborn and Ladson-Billings, 2010). The emphasis of CRT in education is important to recognizing and challenging systemic racism in educational institutions. Teachers need to be culturally competent and aware of their own biases and assumptions. “Culturally relevant teachers utilize students' culture as a vehicle for learning” (Ladson-Billings, 1995, p. 162). Cultural capabilities of teachers refer to the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for teachers to effectively engage with students from diverse cultural backgrounds (Gay, 2018). Teachers with strong cultural capabilities can recognize and address ways in which racism manifests in educational systems and use this knowledge to create more equitable learning environments.

Critical Race Theory in education highlights the importance of valuing and affirming the cultural identities of students from diverse backgrounds. Teachers with cultural capabilities can

a. recognize and appreciate the diversity of their students and create inclusive learning environments that reflect and celebrate cultural backgrounds and; b. are better able to incorporate diverse perspectives and experiences into their curriculum (Menash, 2021), creating a learning environment the promotes critical thinking, dialogue and understanding across cultural differences (Brown, 2007).

Many educators across the world struggle to build and maintain their cultural capabilities to successfully engage with and teach students from culturally and linguistically diverse and Indigenous backgrounds. Research on Australian South Sea Islanders in the education space is limited. The purpose of this scoping review is to synthesize contemporary worldwide literature that focuses on current approaches used by educators who engage with marginalized groups in their communities to improve cultural responsiveness and capabilities. The review methodology is designed to “scope” the literature to identify common elements in approaches with culturally and linguistically diverse and Indigenous groups across the world. In doing so, it draws strength from the similarities shared by many of these groups internationally. The review will describe approaches to increase cultural capabilities currently being used by educators to successfully engage with marginalized groups in their communities.

Methods

Scoping reviews are designed to clarify key concepts, identify characteristics, and analyse knowledge gaps evident in literature (Munn et al., 2018). This scoping review adopted a scoping review guideline first proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005, p. 22) which includes the following five stages: Stage 1: identify the research question; Stage 2: identify relevant studies; Stage 3: study selection; Stage 4: charting the data; and Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. In this review we advance on Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) Stage 5 to contextualize the review results by developing a concise and coherent set of approaches that can be used to produce an engagement strategy and inform a practice guide, that aims to improve upon the cultural capabilities of teachers engaging with Australian South Sea Islander students, families, and communities. That engagement strategy and practice guides are separate documents.

Below we describe in detail the five stages of the methodology followed for this scoping review.

Stage 1: Research Questions:

Research questions are designed to refine the parameters and provide direction for the research (Khoo, 2005) Considerations for questions that related specifically to the Australian South Sea Islander education contexts included defining what is important when improving upon educators' cultural capabilities, and what is similar and different for various minority groups around the world. The following key research questions informed the systematic search strategy for the review:

1. What approaches have been used and proven to be effective in improving the cultural capabilities of educators?

2. What similarities and differences are evident across the approaches identified?

3. To what extent do any of the identified approaches:

- employ teacher engagement and/or connection to Country (place) and community (people) and/or,

- embed cultural content as part of the teaching and learning programs, and how?

Stage 2: Identify Relevant Studies

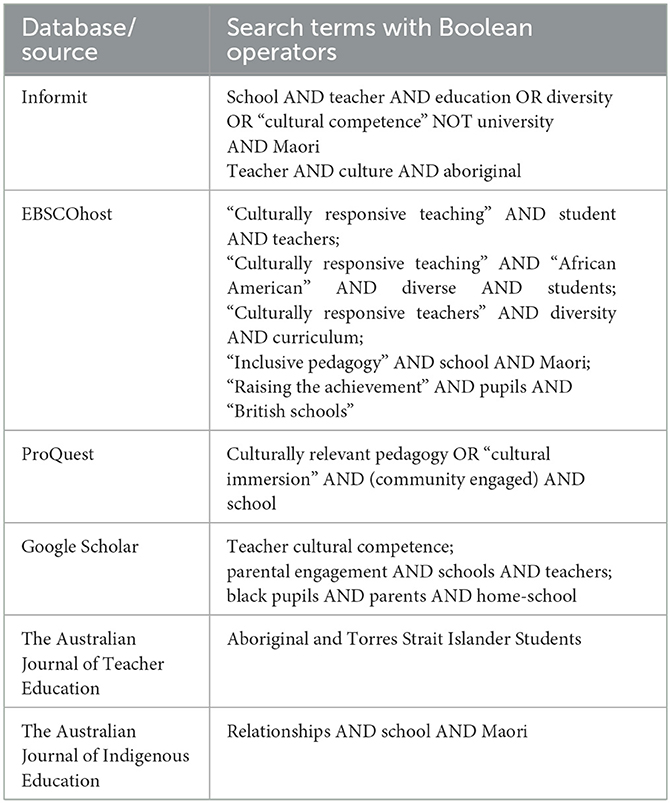

A systematic search strategy was used to identify the relevant studies. This was conducted through systematic searches of the three most relevant scholarly database platforms: Informit, EBSCOhost, and ProQuest. Google Scholar was also searched to identify gray literature such as relevant government departmental strategy documents. Furthermore, two key education journals were hand-searched to identify papers that may have been missed in database and reference list searches, these were: The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, and the Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. The latter journals were specifically included to ensure a comprehensive capture of possible literature pertaining to the Australian context. The search strategy by database is shown in Table 1.

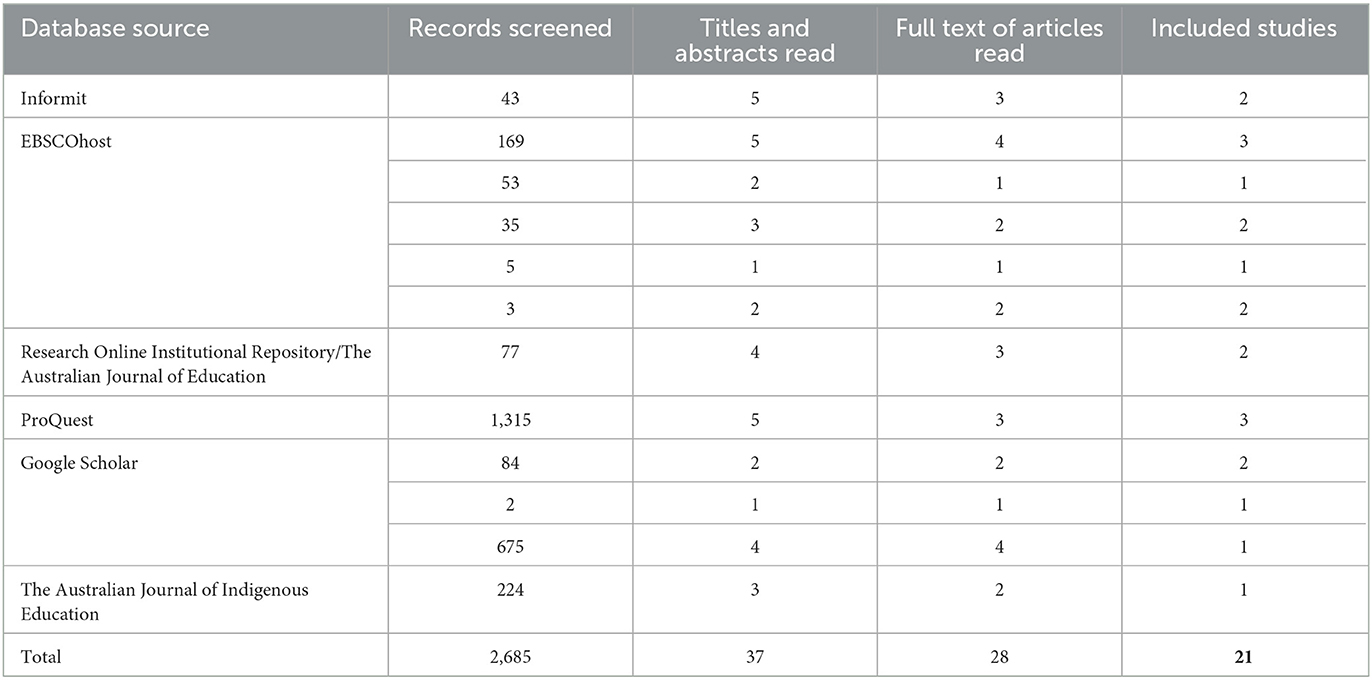

Database filters were applied to ensure papers were full text accessible, peer-reviewed, written in the English language, and published between the years 2000 and 2020. Search strings for each database were refined in several iterations to ensure these were picking up on the most relevant studies. Searches were further refined to capture terminology used in different countries. In becoming familiar with the countries' use of different terminology to describe teachers, students, minority groups, and engagement strategies, the search was further refined particularly by using the specific name of the minority group. A comprehensive set of keywords from Table 1 was applied in the different databases. Table 2 shows the databases searched, number of records screened, number of titles and abstracts read, the full text read, and included studies. Stage 3 describes the inclusion and exclusion categories for the screened records.

Stage 3: Study Selection

The search for studies centered around the cultural capabilities of educators engaging with families and communities. As noted above, studies eligible for inclusion were:

1. Written in the English language,

2. Published between the years 2000 and 2020,

3. Full text accessible,

4. Peer reviewed, and

5. Focused on cultural capabilities of educators (using the search terms listed above).

Studies not eligible for inclusion were:

1. Non-empirical studies, revisions, letters to the editor and editorials,

2. Content of the study not related to school education, and

3. The population not being school age and/or a minority group.

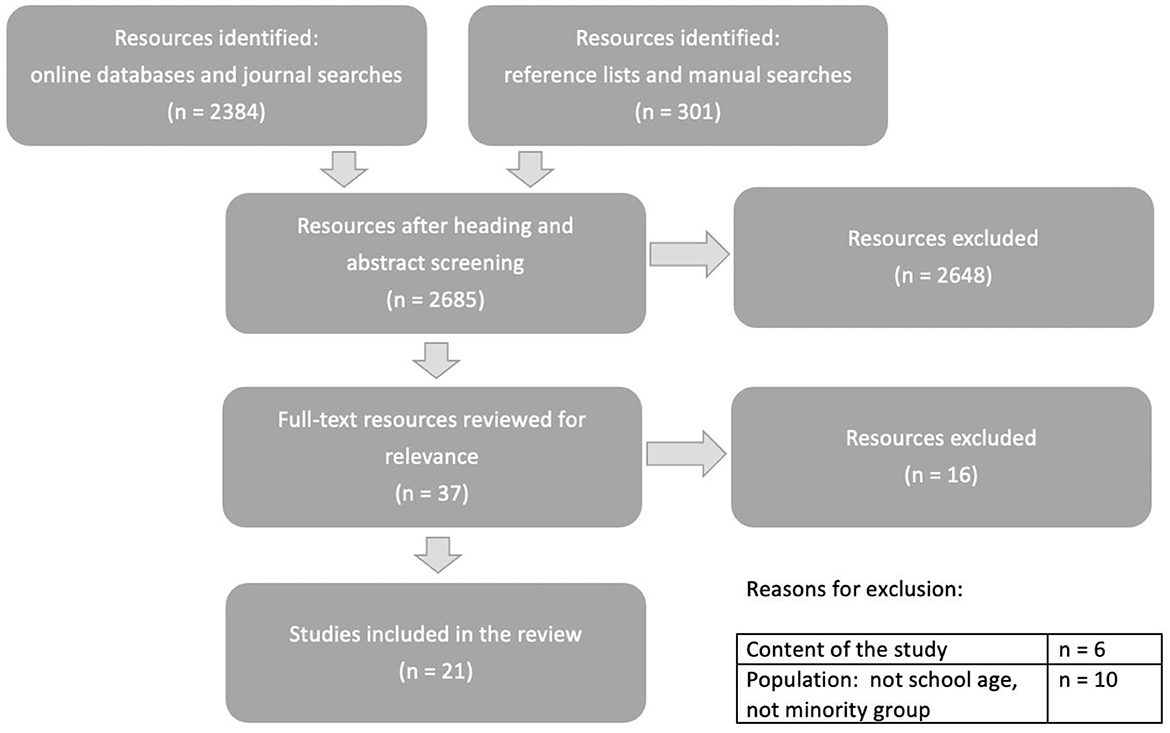

Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram, presenting the result of the search strategy, applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria from beginning to end. The screening was completed by a project research assistant (RA) who discussed study selection throughout the course of the project with the chief investigator (CI). The full texts of studies were read by both the RA and the CI, with uncertainties resolved through discussion until agreement was reached with the CI having the final say. The relevant information was extracted from the papers and analyzed by the CI to inform the review.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram. Adapted from Arksey and O'Malley (2005).

There were 2,685 papers identified from: (i) online database and journal searches (n = 2,384) and (ii) reference lists and manual hand-searches (n = 301). In total, 2,648 papers were excluded after the abstracts were screened because they were non-empirical (for example, revisions, letters to the editor, or editorials). From the titles and abstracts of the remaining papers (n = 37), 16 were excluded because the content of the study was not education related, or the study population did not include school aged students or minority groups. This left a total of 21 studies to be used in the scoping review. The final studies (n = 21) thus all met the inclusion criteria.

Results

Charting the data

There are three core research questions directing this study. The first question: “What approaches have been used and proven to be effective in improving the cultural capabilities of educators?” was the overarching question. The corpus of articles for this review comprised studies where teachers took culturally responsive approaches to engage with communities. Of the 21 studies, four had been conducted in Australia with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. One case study was about a program that was being implemented in New South Wales Schools, two were research-based case studies and one was a literature review.

There were no studies that specifically focused on Australian South Sea Islander students or engaging with their families and communities as studies in this area do not yet exist. The data charting process involved reading and re-reading each of the papers, and manually extracting excerpts of relevant texts, coding the texts and tabulating results. The initial scoping analysis revealed a potential suite of six educator engagement strategies. These included:

1. culturally responsive teaching (CRT),

2. connecting to the community and country (or place),

3. understanding culture and histories of minority groups,

4. a vision of teaching and learning in a diverse society,

5. building relationships,

6. Elder demonstrations and sharing of knowledge in schools.

The second question, “what similarities and differences are evident across the approaches identified?”

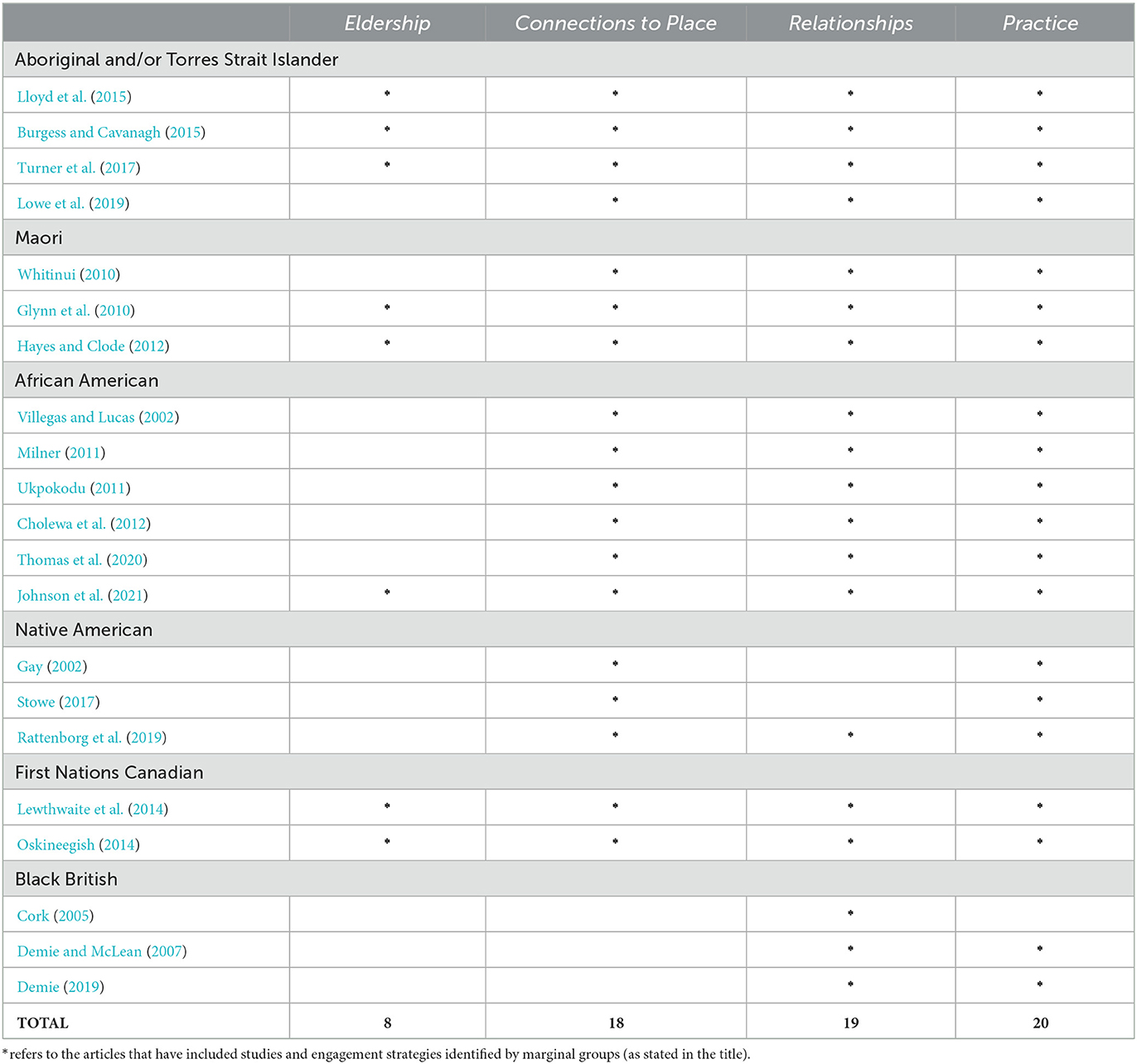

Upon further analysis, and mindful of overlaps between the categories, these six strategies were condensed to four as some of the strategies aligned themselves closely with others. Culturally responsive teaching, understanding the culture and histories of marginalized groups and a vision of teaching and learning in a diverse society were three original strategies that became one strategy based on the concept of culturally responsive practice. The four final strategies include: (i) eldership, (ii) connection to place, (iii) relationships, and (iv) practice. Table 3 lists all 21 included studies and identifies the engagement strategies evident in the studies.

Discussion

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The following discussion summarizes, reports, and interprets the results of the scoping study. It highlights approaches to increasing educators' cultural capabilities that have been successful in communities where minority and marginalized groups exist. The data extracted from each paper is included in the summary of each strategy.

Eldership

Community expertise is delivered in multiple contexts and includes community Elders (Thomas et al., 2020). Inviting Elders and community members into the classroom creates a time not only for children to learn, but also for educators and their own learning (Oskineegish, 2014). Relationships forged between educators and community members are important. Turner et al. (2017) describe how Gumbaynggirr Elders were brought together with teachers in a collaborative effort to create a Bush Tucker Garden. This “Pathway of Knowledge” created a space where teacher knowledge and understanding were strengthened and provided an enriched learning experience for students.

In New Zealand, Tuakana-teina is a system where Elders support and mentor younger people (Hayes and Clode, 2012). These relationships enable educators to learn who is available and willing to come into the schools, as well as the proper protocol for inviting Elders and guests into the school and classroom (Oskineegish, 2014). Where possible, educators should introduce content through a narrative presented by a community elder (Lewthwaite et al., 2014). “Elders are rich sources of knowledge for language and cultural transmission” (Neganegijig and Breunig, 2007, p. 310) and have influence over younger generations. The way in which they communicate with younger people takes on traditional forms and is “lived out in contemporary society” (Oskineegish, 2014, p. 515). Localized experiences, where educators visit significant cultural sites and are given talks by Elders, are a crucial element for building relationships with Elders (Lloyd et al., 2015).

In Canada, much First Nations knowledge, culture and language instruction is often undervalued with more time being spent on Western content. This lack of regard sends the harmful message that the latter is more important. First Nations knowledge is part of the whole student and their relationships with community (Oskineegish, 2014). The participation of Elders and families in teaching culture at school is encouraged (Lloyd et al., 2015). Glynn et al. (2010) speaks about the positive experiences in New Zealand of sharing the teaching role with (Maori) Elders and their extended families or whanau.

Connections

Knowledge holders embody the traditional culture and understandings that involve spiritual, social, environmental, and educational connections to “place”. Australian Aboriginal people have a strong connection to Country which is intrinsic to their being (Turner et al., 2017). There are many lessons to be learnt from Indigenous people across the world and their connection to Country, land, or place. Land-based education allows non-Indigenous educators to incorporate what they know about the values and practices of a community into the learning process (Oskineegish, 2014). Educators must be willing to take students out onto the land (Oskineegish, 2014). Lowe et al. (2019) speak about being an effective educator and establishing a multi-layered connection to kin and Country or place. Context-specific learning is influential when specific to place (Lewthwaite et al., 2014). For example, in New Zealand different iwi (tribes) might have different stories about their connections to Land, to the mountains or harbors depending on their tribal area (Glynn et al., 2010).

Oskineegish (2014), a First Nations educator in Canada, stated: “whenever we try to bring cultural activities into the school it doesn't really work, we have to take the students out into the land and the teacher has to be willing to go to these activities too” (p. 516). Partnerships with community bring a different perspective and cultural knowledge into the school and in turn create a new knowledge set for all (Turner et al., 2017). Similarly, speaking of embedding Lakota history and culture and highlighting Native voices, Stowe (2017) strongly suggests the importance of being mindful of the larger picture of history which includes many perspectives and stories, and not just a western-dominated view.

In many cultures there is a strong emphasis on family and kin (Cholewa et al., 2012). For educators to understand community context, it may require an interdisciplinary approach to engage in rich history and culture (Stowe, 2017; Johnson et al., 2021). Connecting with community may involve home visits, consultations with communities where students reside (Villegas and Lucas, 2002) and participating in community events (Thomas et al., 2020). For students to see their culture reflected in the curriculum helps them better understand their identity and important ways in which their culture has contributed to the curriculum (Milner, 2011). Furthermore, it is important for educators to know other cultures to be able to interact more effectively with their students, families, and communities (Ukpokodu, 2011, p. 450).

In Turner et al.'s (2017) study, content endorsed by Aboriginal Elders provides non-Aboriginal teachers with an understanding and appreciation of local Aboriginal knowledge that flows through to the students in the classroom. A similar effect is felt with the presence of community people in the greater school-wide context in New Zealand via cultural performances and the recognition of Maori language, signage, and community information (Hayes and Clode, 2012). However, Whitinui (2010) warns that there is still a lack of understanding about how teacher discernment of cultural connections improves overall students' wellbeing. Teachers can include localized and contextualized content through modeling and developing culturally and socially rich learning experiences within the classroom (Burgess and Cavanagh, 2015). Connecting to land and place contributes to a deeper understanding of a larger connection to identity, and identity provides a sense of pride and ultimately with a motivation to learn (Oskineegish, 2014).

Relationships

It is important to understand the importance of building and sustaining relationships between educators and students (Milner, 2011; Ukpokodu, 2011). Positive relationships between teachers and students can be formed through both verbal and non-verbal actions. Open communication with students helps teachers gain trust and build close relationships (Johnson et al., 2021). Building relationships involves just being another human being. Students need to be listened to respectfully when they communicate their feelings (Lowe et al., 2019).

Community mentors may serve as cultural ambassadors and provide insight into the values of families within the community (Thomas et al., 2020). Children are more likely to experience racism, stereotyping and low expectations if a school lacks cultural diversity in its representation of staff and curriculum (Demie, 2019). A welcoming environment is synonymous with nurturing qualities that characterize a teacher's relationships with their students (Rattenborg et al., 2019). Celebrating cultural diversity and increasing cultural immersion has a positive impact on building relationships and cross-cultural understanding between students and staff and furthermore enhances relationships with the broader community. A genuine collaboration with community improves achievement (Lloyd et al., 2015). Principals and leaders are important in connecting schools with communities and progressing the development and maintaining of authentic relationships (Burgess and Cavanagh, 2015).

Students from non-dominant groups should be encouraged to build on individual and cultural resources they bring to the school. Respect for students provides a basis for meaningful relationships between educators and students which produces favorable academic results (Villegas and Lucas, 2002).

A simple approach for acknowledging student voices is a strategic goal to success (Hayes and Clode, 2012) which may include the building of trusting and respectful relationships between educators and students (Glynn et al., 2010). This emotional connectedness fosters a sense of attachment and emotional bonding between educators and students (Cholewa et al., 2012), which can lead to improvements in educators' professional practice.

Practice

Culturally responsive teaching should reflect and validate educational experiences that promote student culture and language. This should be reflected and encouraged from leadership and the management and operation of the school but also in the curriculum and the pedagogies used (Lewthwaite et al., 2014). Culturally responsive pedagogy uses cultural knowledge to facilitate the teaching and learning process (Ukpokodu, 2011). There is not one method of developing culturally responsive lessons. There is importance in the engagement and the experiences built through relationships with people and place (Oskineegish, 2014). Cholewa et al. (2012) also recognizes the importance of communication styles and cultural identities of students. Successful schools provide purposeful leadership and high expectations for students and educators. An inclusive curriculum has strong links to the community, the involvement of parents, extensive use of mentors and role models, and a strong commitment to equal opportunities. The engagement of parents and the community is a key strategy to student achievement (Demie and McLean, 2007; Demie, 2019).

Lloyd et al. (2015) encourages a syllabus that is flexible; a curriculum negotiated at the local level for teachers to address their students' knowledge, culture, and interests. Content should provide practical hands-on activities, engagement, and opportunities for student reflection (Lowe et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2020). For example, the literature reviewed shows that there are several benefits and advantages when integrating different aspects of students' culture into various subjects and across the curriculum. Including Maori knowledge as part of the curriculum can support the learning needs of Maori students (Whitinui, 2010), while Cholewa et al. (2012) describe the importance of utilizing the common aspects of communication styles of African American communities, that include oral storytelling and narratives.

Students should have the opportunities to understand multiple cultural perspectives and not be restricted to a Eurocentric history (Stowe, 2017). Culturally Responsive Teaching promotes discussions that are regularly excluded from the classroom. It allows students to build on their personal cultural strengths and examines the curriculum from multiple perspectives, further building on students' cultural strengths, making the classroom inclusive (Gay, 2002; Villegas and Lucas, 2002). Best cultural practices include the development of resource materials that respond to student and family cultural backgrounds (Lewthwaite et al., 2014; Oskineegish, 2014; Burgess and Cavanagh, 2015).

Teachers who are engaged with their communities have the potential to develop as culturally responsive educators (Thomas et al., 2020). Teachers should reflect on their own view of culture and its role in teaching (Ukpokodu, 2011). Culturally responsive pedagogy presents challenges to mainstream teachers whose teaching practices represent the dominant culture (Glynn et al., 2010). Culturally responsive pedagogy addresses the negative effects that students can experience from not seeing one's history and culture represented in the curriculum. Teachers who see culture as an asset to student success use culturally responsive pedagogy to empower and include their students (Milner, 2011).

Conclusion

Through contemporary research, this scoping review has highlighted empirically supported approaches that are currently being used by educators across the globe to increase their cultural capabilities and successfully engage with culturally and linguistically diverse and Indigenous groups in their communities. The four elements that emerged from the literature; eldership, connections, relationships, and practice, have implications for educators working in the Australian South Sea Islander context. Twenty years ago, the Mackay and District Australian South Sea Islander Association (MADASSIA) received funding to put together a protocols document. The limitations of this document are that it is specific to one community, and not specific to the education context. The literature from the scoping review, supports the information in this document and not only contextualizes it for the Australian South Sea Islander community but for educators as well.

The second part of this Horizon Grant project is to use this scoping review for the development of a separate engagement strategy focusing on potential strategies for educators working in communities with high populations of Australia South Sea Islander students and families. More broadly, the results from this research could potentially be used to assist other culturally and linguistically diverse and Indigenous groups with their engagement strategies between school and home.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: The data for this project will be found at the Queensland Education Research Inventory https://research.qed.qld.gov.au/#/.

Author contributions

FB-H did research design and methodology, identified and analyzed themes, and wrote results into paper. ZY applied the research design and methodology to begin the systemic review. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Education Horizon Research Grant Scheme, Queensland, Department of Education, 2020-2021 Funding Round.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Applebaum, B. (2010). Race, critical race theory and whiteness. Int. Encyclop. Educ. 6, 36–43. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00541-8

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Bobongie-Harris, F., and Fatnowna, C. (2023). Australia's Shame: Blackbirding and Its Connection to the Trafficking of Human Remains. Available online at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/239714/

Brown, M. R. (2007). Educating all students: creating culturally responsive teachers, classrooms, and schools. Intervent. School Clin. 43, 57–62. doi: 10.1177/10534512070430010801

Burgess, C., and Cavanagh, P. (2015). Cultural immersion: developing a community of practice of teachers and aboriginal community members. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 45, 48–55. doi: 10.1017/jie.2015.33

Cholewa, B., Amatea, E., West-Olatunji, C. A., and Wright, A. (2012). Examining the relational processes of a highly successful teacher of African American Children. Urban Educ. 47, 250–279. doi: 10.1177/0042085911429581

Cork, L. (2005). Supporting Black Parents and Students: Understanding Home-School Relations. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Demie, F. (2019). Raising achievement of black Caribbean pupils: good practice for developing leadership capacity and workforce diversity in schools. School Leadersh. Manag. 39, 5–25. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2018.1442324

Demie, F., and McLean, C. (2007). Raising the achievement of African heritage pupils: a case study of good practice in British schools. Educ. Studi. 33, 415–434. doi: 10.1080/03055690701423606

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 53, 106–116. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053002003

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gillborn, D., and Ladson-Billings, G. (2010). Critical race theory. Int. Encyclop. Educ. 6, 341–347. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01530-X

Glynn, T., Cowie, B., Otrel-Cass, K., and Macfarlane, A. (2010). Culturally responsive pedagogy: connecting New Zealand Teachers of Science with their Māori students. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 39, 118–127. doi: 10.1375/S1326011100000971

Hayes, J., and Clode, A. (2012). Ko te reo o nga akonga: creative leadership of Māori student partnerships. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 27, 56–63.

Johnson, C. S., Sdunzik, J., Bynum, C., Kong, N., and Qin, X. (2021). Learning about culture together: enhancing educators cultural competence through collaborative teacher study groups. Prof. Dev. Educ. 47, 177–190. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1696873

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that's just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Pract. 34, 159–165. doi: 10.1080/00405849509543675

Lewthwaite, B., Owen, T., Doiron, A., Renaud, R., and McMillan, B. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching in Yukon First Nation Settings: what does it look like and what is its influence? Can. J. Educ. Administ. Policy 115, 1–34.

Lloyd, N. J., Lewthwaite, B. E., Osborne, B., and Boon, H. J. (2015). Effective teaching practices for aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students: a review of the literature. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 1–22. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2015v40n11.1

Lowe, K., Bub-Connor, H., and Ball, R. (2019). Teacher professional change at the cultural interface: a critical dialogic narrative inquiry into a remote school teacher's journey to establish a relational pedagogy. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 29, 17–29.

Menash, F. (2021). Culturally relevant and culturally responsive: Two theories of practice for science teaching. Sci. Children. 58, 10–13.

Milner, H. R. IV. (2011). Culturally relevant pedagogy in a diverse urban classroom. Urban Rev. 43, 66–89. doi: 10.1007/s11256-009-0143-0

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., and Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Neganegijig, T., and Breunig, M. (2007). Native Language Education: an inquiry into what is and what could be. Can. J. Nat. Educ. 30, 305–322.

Oskineegish, M. (2014). Developing culturally responsive teaching practices in first nations communities: learning anishnaabemowin and land- based teachings. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 60, 508–521.

Rattenborg, K., MacPhee, D., Kleisner Walker, A., and Miller-Heyl, J. (2019). Pathways to parental engagement: contributions of parents, teachers, and schools in cultural context. Early Educ. Dev. 30, 315–336. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2018.1526577

Stowe, R. (2017). Culturally responsive teaching in an Oglala Lakota Classroom Rebeka Stowe. Soc. Stud. 108, 242–248. doi: 10.1080/00377996.2017.1360241

Thomas, C. L., Tancock, S. M., Zygmunt, E. M., and Sutter, N. (2020). Effects of a community-engaged teacher preparation program on the culturally relevant teaching self-efficacy of preservice teachers. J. Negro Educ. 89, 122–135. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.89.2.0122

Turner, A., Wilson, K., and Wilks, J. L. (2017). Aboriginal community engagement in primary schooling: promoting learning through a cross-cultural lens. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 96–116. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2017v42n11.7

Ukpokodu, O. (2011). Developing teachers' cultural competence: one teacher educator's practice of unpacking student culturelessness. Act. Teac. Educ. 33, 432–454. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2011.627033

Villegas, A. M., and Lucas, T. (2002). Preparing culturally repsonsive teachers: rethinking the curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 53, 20–32. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053001003

Keywords: scoping review, culturally and linguistically diverse, Australian South Sea Islanders, engagement strategies, education, Critical Race Theory (CRT)

Citation: Bobongie-Harris F and Youse Z (2023) Approaches to improve the cultural capabilities of teachers engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse students and their families: a scoping review. Front. Educ. 8:1038880. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1038880

Received: 12 September 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2023;

Published: 26 May 2023.

Edited by:

Elsie L. Olan, University of Central Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

I. Ji Yeong, Iowa State University, United StatesNatalie Nussli, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, Switzerland

Copyright © 2023 Bobongie-Harris and Youse. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francis Bobongie-Harris, ZnJhbmNpcy5ib2JvbmdpZUBxdXQuZWR1LmF1

Francis Bobongie-Harris

Francis Bobongie-Harris Zia Youse

Zia Youse