95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ. , 18 May 2023

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1033388

This article is part of the Research Topic Teaching and Learning in a Global Cultural Context View all 5 articles

Introduction: Providing care for refugees and asylum seekers requires special knowledge and training. Refugees and asylum seekers often have unique health needs that require specialized care.

Purpose: This research focused on the need and relevance of incorporation of refugee and asylum seekers’ health in undergraduate medical curriculum teaching at King’s College London GKT Medical School.

Methods: A mixed method approach was adopted involving review of available literature on refugee health in the medical curriculum, followed by interview and e-survey on the perspectives of tutors and students, respectively.

Discussion: The research points to an overwhelming agreement on the need, learning outcomes and challenges of integrating refugee and asylum seeker health into undergraduate medical and dental education both from the perspectives of clinical teachers and medical students.

Conclusion: A collaborative approach involving students, teachers and refugee stakeholders will help in developing an effective refugee curriculum to provide equitable healthcare in the UK.

Human rights abuses, political and religious strife, climate change, pandemics, and economic downturns have all increased the frequency of human displacement in recent years. The majority of the displaced people are refugees and asylum seekers. A person who has fled their country and is unable to return due to persecution is given refugee status. In contrast, a person who has fled their country due to fear of persecution and applied for (legal and physical) protection in another country but whose application has not yet been reviewed is known as an asylum seeker (UNHCR, 2010; UNHCR, 2014). According to UNHCR figures, the UK was home to 135,912 refugees and 83,489 pending asylum cases as of mid-2021. The most common nationalities who sought refuge or asylum in the UK were from Syria, Iraq, Eritrea, Albania, Iran and Sudan (UNHCR, 2021). Refugees and asylum seekers may be at a slightly increased risk of chronic and communicable diseases, inadequate maternity and mental health due to their insufficient access to basic necessities (BMA, 2022; WHO, 2022). Examples of infectious diseases prevalent in refugee populations include tuberculosis, helicobacter pylori and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). A study in Blackburn found 11 cases of tuberculosis in a sample population of 1,085 immigrants (Ormerod, 1990). Dental hygiene may also be poor due to lack of access and compliance to dental health. A scoping review study on dental health problems in the refugee population of Europe revealed that refugees experience a limited access to oral health care services and a higher prevalence of oral diseases compared to native populations of the host countries. Some studies in the review implemented techniques to improve oral health which resulted in positive outcomes indicating that oral health of refugees can be improved with the right approach (Zinah and Al-Ibrahim, 2021).

The health status of this population might differ due to the differences in access and use of healthcare services, trauma and discrimination experienced during their journey to the UK (Burnett and Peel, 2001; Lebano et al., 2020). Additionally, previous studies have shown that there are healthcare inequities in the UK, especially for refugees and asylum seekers, which has led to subpar mental and physical healthcare (Isaacs et al., 2020; Bansal et al., 2022). Hence, to provide better health outcomes to migrant populations, it is important to train future healthcare professionals to identify refugee health needs and treat them efficiently. Some of the recognized healthcare needs for refugees and asylum seekers necessitate trauma-informed care, cultural competency, empathy, and advocacy (Suurmond et al., 2010; Willey et al., 2022). Trauma has undoubtedly affected the majority of refugees and asylum seekers. The adoption of trauma-informed care techniques which includes a framework for providing human services based on knowledge and awareness of how trauma impacts people’s lives, service requirements, and service consumption, is therefore highly desirable (Willey et al., 2022). The heterogeneity and cultural diversity of this group also necessities cultural competence. Cultural competence is the ability to understand, appreciate, and interact with people from cultures of belief systems different to one’s own (Seeleman et al., 2009). Cultural competence is a way to reduce bias and discrimination in the healthcare settings as this population experiences barriers to healthcare including language, bureaucracy, socioeconomic status and general health illiteracy among other factors (Johnson et al., 2008). This also creates a challenge for healthcare providers who need to navigate their way through these barriers to provide the care that is necessary. Alongside the cultural competence, effective communication and empathy is needed (Yankey and Biswas, 2012), together with enhanced understanding and knowledge of the epidemiology and chronic conditions that affect different population groups (Spallek et al., 2011). This is a task that has been assigned to the clinicians of today and tomorrow without really evaluating if they have the resources and experience to achieve this (Ryan et al., 2020). There is growing interest in UK-based medical schools in designing and developing an inclusive curriculum to assist in providing quality care to a diverse and growing population. The General Medical Council (GMC) and General Dental Council (GDC) have emphasized the importance of patient sensitivity, empathy, and respect among medical trainees (Godkin and Savageau, 2001; Paisi et al., 2020). The professional bodies encourage students to be inclusive and open, regardless of their patients’ status or culture.

Effective teaching not only creates professionals who are apt at treating patients from a migrant population, but it builds the foundation for advocacy, sensitivity, empathy, and cultural competence which will result in a work force that is better equipped for treating all underserved populations. A curriculum that equips medical students and healthcare providers to recognize and tackle the challenges they will face in the future as their patient demographics evolves is critical to address health inequities. The objective of the study was to gather evidences and perspectives of medical teachers and students on the importance of a curriculum focused on refugee and asylum seekers health care. We hope this evidence will be used to design learning outcomes and competencies which will contribute to creating a more inclusive medical curriculum and showing the necessity for training medical professionals in refugee and asylum seeker health. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examined the opinions and perspectives of medical educators and students on the need for and importance of refugee health care in the undergraduate medical curriculum. This bottom to top approach will provide compelling evidence to the senior management on the importance of inclusion of refugee health care in medical school curriculum. This study will thus enable the design of a curriculum aid and equip future medical professionals to respond to the health needs of refugee and asylum seekers, thereby alleviating health inequities. Even though, the work was based on research from United Kingdom, the evidences presented will help other medical schools to develop more inclusive medical curriculum especially in those countries which host refugee populations.

A mixed method multiple phase approach was used to collect and examine the perspectives and opinions of medical teachers, healthcare professionals and students in the UK medical schools on refugees and asylum seekers’ healthcare. The first phase included a scoping review to identify the existing literatures on refugee health care education in medical schools and the attitude of teachers and students toward it. This was followed by interviews with the key informants in refugee health education and by e-surveys from medical students in the UK. The key informants including medical educators and students were recruited through an advertisement. The data collection and analysis complied with the GDPR and KCL ethics guidelines. The ethical approval for this research was granted by King’s College London.

A scoping review was conducted to ascertain the extent of literature available on the subject and the existing knowledge and gaps in knowledge. The objective of this scoping review was to review the current educational content available on refugee and asylum seeker health in undergraduate medical education and to establish the key themes prevalent in the literature. This scoping review followed the methodology developed by the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018). The flow chart outlining the selection process for sources of evidence can be found in Figure 1. Peer-reviewed journals were searched from the bibliographic databases PubMed, Scopus and DOAJ. Peer reviewed journal papers were included if they were: published between the period of 2002–2022, written in English and discussed refugee and/or refugee health in the undergraduate curriculum. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies were included to broaden the inclusion criteria. The following search terms were used: refugee, asylum seeker, health care, undergraduate program, medical curriculum, dental curriculum. The search terms were combined with operators AND and OR for the search. Papers were excluded if published prior to 2002 to ensure the research is up to date. Papers were excluded if not written in English and did not discuss refugee and asylum seeker health. Data was charted manually by the authors (RP, WJ) and was abstracted and grouped according to study type, educational content, delivery methods and findings. No gray literatures were included.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for refugees and asylum seekers health in undergraduate medical and dental curriculum.

Key informant interviews were conducted during the month of July 2022 with global health faculty, medical education faculty and professionals working in the field of refugee and asylum-seeker health. Two key informants were part-time faculty members of King’s College London working in the medical education or global health department. One key informant is currently part of the health inclusion team based in Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Trust which is a major teaching hospital in the UK. The remaining key informant has had extensive experience in refugee health and continues to work in the field as part of a charity in Bangladesh.

Interviews with key informants were semi-structured to collect and analyze qualitative data. A semi-structured approach was adopted to encourage two -way communication and address key points with all informants, e.g., reasons for interest in refugee health and experience in refugee health. However, the semi-structured nature of the interview meant that informants had the liberty to discuss topics which they deemed to be relevant and important. This increased the scope of the interviews and the amount of information gained. Two interviews were conducted through Zoom communications while the other two interviews were conducted in person at the workplace of the interviewee. All interviewees were approached via email to obtain consent for their participation. All interviews were transcribed with the assistance of a virtual transcribing application (“Descript”) and reviewed manually by the authors to ensure accuracy. The authors then reviewed each interview to identify key quotes relating specifically to refugee and asylum seeker health in the undergraduate curriculum. The quotes were then grouped according to key themes as follows: experience with refugees and asylum seeker health, views on the undergraduate curriculum, barriers to healthcare and underserved populations. Themes were identified and selected manually, and an overall analysis of the interviews were developed with key quotes that pertained to refugee health or education being grouped into one of three categories: interest and experience with refugee health, structural and hidden barriers to healthcare and views on delivering refugee health/undergraduate curriculum. These three themes were discussed by all key informants extensively and hence they were selected as a basis for thematic analysis.

Student enrolled in undergraduate degrees in medicine and dentistry were sent an e-survey created using Google forms to gather their views on refugee health. The form consisted of questions relating to refugee and asylum seeker health in comparison to the health of the general population. This was done to ascertain differences between attitudes and opinions between the groups. This allowed for the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data.

Our mixed method approach established the need for incorporation of refugee and asylum seeker health in the undergraduate medical curriculum and identified values, principles and topics for refugee and asylum seeker health education.

The results of the scoping review indicated the need for integrated refugee health teaching in undergraduate studies. All 14 studies included in the review concluded that incorporating refugee health teaching into the curriculum improved health outcomes via improved knowledge and skills of the undergraduate students on refugee health. Multiple studies also highlighted that delivering refugee health teaching improved students’ communication skills, self-perception and other health skills which can be extrapolated to infer that it made them better clinicians. In a qualitative study conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 33 medical students participated in a total of 51 field visits to 4 refugee camps near Mostar, Bosnia, and Herzegovina, over a period of 2 years. The students were able to perform physical examinations and small interventions. At the end of the project, participants were surveyed to assess the benefits of the program. Fourteen students said that “the opportunity to do something, however small, for the people” was the main benefit of the project and five students thought that meeting a “real patient” who was a refugee early in their medical studies was beneficial (Ðuzel et al., 2003). Another qualitative study conducted in Australia introduced a novel course covering burden of global disease, travelers’ medicine, and immigrant health to students at the University of Adelaide. The course was received positively according to qualitative data gathered from the students and hence a module titled ‘Global health’ was integrated into the curriculum in 2011 (Laven and Newbury, 2011). A mixed method study conducted in the USA examined the educational outcomes of teaching refugee health to residents and medical students through lectures, immersive experiences and other teaching methods. The medical students and residents completed a pre- and post-curricular assessment. They found a 50% increase in the overall curricular knowledge of residents with knowledge about malaria, asylum and women’s health increasing by more than 75%. A 74% increase in overall curricular knowledge scores was demonstrated by the medical students. This illustrates how integrating and teaching refugee health can improve knowledge on multiple areas of curriculum (Levine and Serdah, 2020). This meant that it not only benefited a refugee population but that students were better equipped to treat patients from other underserved populations.

Four key informant interviews were conducted with clinicians in the medical education field or clinicians working with refugees and asylum seekers.

Key informant 1 currently works as a GP at a tertiary care center as part of a health inclusion team which covers the Southwark and Lambeth areas of London. They have had extensive experience working with refugees and asylum seekers in London. The key themes that emerged from this interview related to barriers of access that refugees face and how they are tackled. The informant raised the importance of raising awareness and advocacy to challenge these barriers and stressed the importance of taking a holistic view of the patient.

“There are key themes that are barriers to healthcare such as being excluded from health, finding it difficult to register with primary care services, maintaining continuity and access to treatment for chronic diseases and immunisations.”

Key informant 2 currently works with a refugee camp in Bangladesh and has various experience around the world, volunteering in refugee camps and centers. They raised the important point of targeting our own biases toward refugees and misconceptions that we have. In relation to the undergraduate medical and dental curriculum, the informant highlighted the importance of raising refugee and asylum seeker health as part of the curriculum. They raised the key idea that although many learning points may be lost on undergraduate students due the vast amount of teaching in the medical degree, it is important to introduce the idea that refugees are different to the host population and that tailoring of care is required. They elaborated that although not every piece of information taught is retained there are certain poignant topics, such as delivering care to underserved populations, that are remembered and will be useful when a student meets a patient from such a population in their career.

“With the undergraduate curriculum, if there even is that thought of refugees are different and I need to tailor how I speak or how I approach them…You can just imagine someone in that auditorium who in a couple of years when they are doing their F1, F2 or Core surgical training and meet a patient who is a refugee…You tend not to remember everything from the undergraduate curriculum but there are certain things that you do.”

Key informant 3 currently works as a GP in South London and is a member of the Global health faculty at King’s College London where they teach fifth year medical students. They have also had extensive experience traveling and working with refugees in areas of conflict, e.g., Syria. Their experience informed them of the needs for refugees and barriers to healthcare that they face. With regards to refugee healthcare in London, they spoke of barriers such as not being able to access primary care due to lack of documentation despite this not being a requirement. They raised the issue of lack of awareness and advocacy which worsens outcomes.

“As the years have gone on, I’ve realised that you can make a difference at home, you do not have to go to the other end of the world to do it. There is a huge need for refugee health here in London.”

Key informant 4 spoke extensively regarding the undergraduate medical curriculum as they were part of the team that partly organized the second year of the MBBS curriculum at King’s College London. They stressed the importance of the curriculum reflecting “real-life” and that educators, not only students, benefited from such teaching due to increased satisfaction and fulfillment. This satisfaction and fulfillment arose from teaching and advocating equity for underserved populations.

“There are a lot of things you can learn from books but this [refugee health] you need to be part of the care or part of the conversation.”

The following three themes emerged from the interview of the key informants: interest and experience with refugee health, structural and hidden barriers to healthcare and views on delivering refugee health/undergraduate curriculum. The complete analysis of the transcribed interview and thematic identification is provided as SEQ (Table 1).

The interviews revealed that key informants were motivated to pursue refugee health due to their personal experience as a volunteer medical student in a refugee camp, lived experience as a refugee or an interest in global health and humanitarian medicine. A majority of the key informants were interested in helping vulnerable populations during their undergraduate medical studies but did not have avenues to learn or train until their specialist training.

All the key informants agreed on the importance of incorporating refugee and asylum seeker health in the undergraduate medical curriculum. According to them, teaching on topics related to refugee health provides scope to integrate discussion on human values, improves soft skills including communication and provides discourse on current and realistic clinical scenarios.

The key informants also discussed possible learning outcomes of adding refugee health topics to the undergraduate medical curriculum so that an understanding of the health determinants of refugee communities in reference to similarities and disparities with local populations, articulate intercultural knowledge, attitudes and competencies and apply skills and insights to navigate complex clinical scenarios. They noted that the curriculum would benefit all underserved populations and not just refugees.

Finally, several key informants acknowledged the perceived challenges in implementing refugee health teaching including time constraints, mapping it across the medical curriculum rather than as a standalone module and potential to cause psychological or physiological stress in students from similar backgrounds as those in simulated cases.

An e-survey was designed to determine the confidence level, knowledge and skill gaps of London-based medical school undergraduate medical/dental students pertaining to refugee and asylum seeker health. The survey received 19 responses from medical and dental students in the UK, the majority (>90%) of whom were London-based medical school. The second- and third-year medical students accounted for 68.4 and 10.5% of the respondents, respectively. The rest were from year 1, years 4–6 and intercalated year of the medical school. The results of the survey are outlined in Table 2 and images below. The characteristics of the respondents can be found in SEQ (Figure 1).

According to e-survey responses obtained in Table 2, the undergraduate students were less confident in interacting with foreign-born patients and obtaining case histories from them. A majority of the respondents felt they are lacking in confidence to obtain sensitive clinical information, but more than half of the respondents could identify cultural influences on patient health decisions. A small majority of students were aware of traditional and alternative systems of medicine practiced globally and a similar trend was observed regarding students’ understanding of logistical hinderances for compliance and medical follow-up of treatments. However, a majority of students were not aware of the cultural and social hindrances to compliance and medical follow up of treatment. Finally, a small majority of students were informed on the mental health issues common among refugees and asylum seekers but were less certain about the medical issues common to the same group.

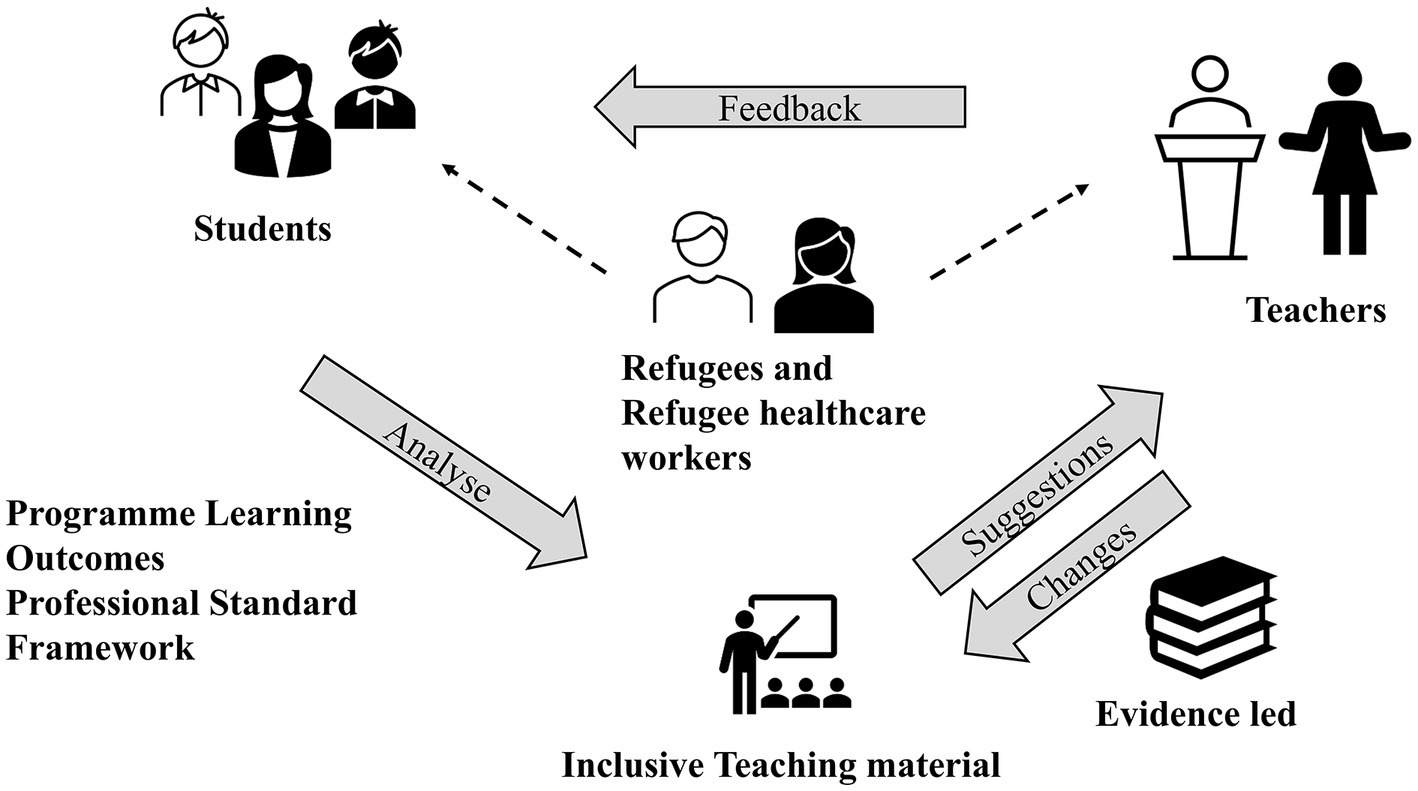

We propose a tripartite collaborative model for developing a curriculum framework and incorporating refugee and asylum seekers’ health into the medical curriculum (Figure 2). This will be student-led and supported by clinical academic and non-clinical experts on refugee and asylum seekers’ health. The proposed changes to the curriculum will be evidence based and meet the program outcomes and General Medical and Dental council guidelines. The key topics, learning objectives, educational delivery and assessment methods will be reviewed and will be approved based on consensus on stakeholders including students, educators, refugees and asylum seekers.

Figure 2. Tripartite model for the development of refugee curriculum. The student-led curriculum development will be supported by teachers and received input and feedback from stakeholders like refugees and refugee healthcare workers. The inclusive teaching material will align with program learning outcomes, professional standard framework and be evidence-led.

The UK has provided a haven for refugees and asylum seekers and in compliance with the 1951 Refugee Convention, it has provided equal access to health care on a par with the host population (NHS, 2014). This research examines the need for an appreciation of a refugee and asylum seeker health curriculum in the undergraduate medical and dental program from the perspective of teachers and undergraduate students.

The sequential mixed method approach systematically examined the evidence available in peer reviewed literature and was able to identify the need for a refugee curriculum associated teaching themes and its benefits in undergraduate teaching in medical and dental schools worldwide.

The scoping review formed the basis of the key informant interviews and medical students e-survey. The scoping review revealed a broad agreement on the need of refugee and asylum seekers’ health in the undergraduate medical curriculum (Dowell et al., 2001; Dussán et al., 2009; Bernhardt et al., 2019). The refugee and asylum seeker health content introduced medical students to concepts in global (Gruner et al., 2015) and inclusion health (Sharman et al., 2021) and the importance of cultural awareness (Griswold et al., 2007) when serving diverse and underprivileged populations. The topics also provided the students with cultural awareness and cross-cultural medical and advocacy skills (Griswold et al., 2006; Levine and Serdah, 2020; Rashid et al., 2020). The students reported improved self-esteem and confidence to treat patients and provided positive feedback on evaluation of the refugee health content (Ko et al., 2005; Laven and Newbury, 2011; Goez et al., 2020; Rashid et al., 2020).

Three major themes emerged from the analysis of the key informants’ interview transcripts. Key informants spoke about their interest in refugee health and their experience with teaching the same. All key informants received no training in refugee health education in their undergraduate curriculum and had to rely on specialist courses later in their career or draw inspiration from their volunteer work or lived experience in refugee camps (Anderson et al., 2007). All the key informants were interested in humanitarian medicine or global health during their undergraduate medical training and were highly motivated to participate in refugee and asylum seeker health teaching delivery while continuing to work on refugee health (Gjerde and Rothenberg, 2004).

All key informants highlighted the barriers to healthcare access in underserved populations including refugees and asylum seekers within the UK. Structural and hidden barriers within the healthcare system can lead to inadequate healthcare and worse outcomes to underserved populations. Lack of clear guidelines on patient registration for primary healthcare or upfront payment for secondary healthcare, and complexities of navigating the NHS healthcare system were highlighted as structural issues impeding healthcare access in UK (Stagg et al., 2012; Asif and Kienzler, 2022). Cultural and language discordance and physicians’ own perceptions, attitudes and behaviors were discussed as hidden barriers to healthcare access for refugees and asylum seekers (Altshuler et al., 2003; Hudelson et al., 2010; Samkange-Zeeb et al., 2020; Puthoopparambil et al., 2021).

According to the key informants, refugee health teaching in the curriculum can provide a platform for discussions on inclusion health and the serving of underprivileged populations (Schonholz et al., 2020). Discussion on inclusion health and health disparities are largely ignored in medical curricula which has led to under informed and unprepared medical graduates resulting in dissatisfied students and patients with poor outcomes (Strange et al., 2018). Language and cultural barriers contribute significantly to the health disparities experienced by patients with limited English proficiency which can be ameliorated through cultural competence and cross-cultural communication training. The health issues surrounding the refugee crisis will provide medical students current and realistic clinical scenarios early in their training which will better prepare them to care for marginalized populations such as refugees and asylum seekers (Merritt and Pottie, 2020; Schonholz et al., 2020).

The key informants were able to outline learning outcomes for refugee health curricula in medical school. The themes highlighted were understanding the health determinants of the refugee community including socioeconomic factors and social support, implementing intercultural knowledge, attitudes, and skills to provide people-centered and evidence-informed care and developing competencies and insights to promote the health of refugees and asylum seekers (Mawani, 2014; Chiarenza, 2019).

The perceived challenges in incorporating refugee health into the curriculum would be the following: time and resource constraints, developing outcome evaluation strategies and scheduling refugee health teaching without impacting teaching on other underprivileged populations or overcrowding the curriculum (Griswold, 2003; Gruner et al., 2022). Discussions on refugee health can be sensitive or contentious for students who are from a similar background or have a colleague from such a background hence appropriate measures such as trigger warnings or graded exposure might be adopted to minimize stress (Nolan and Roberts, 2021).

Various initiatives, such as international electives and cultural competence seminars, have been implemented in UK medical schools to reflect the culturally diverse society, but refugee health has rarely been taught as a component of medical education. Few students knew how to engage with foreign born patients such as refugees or obtain sensitive information from those who experienced trauma (Drennan and Joseph, 2005). Physicians unaware of culturally sensitive issues confronting the refugee community can have a negative impact on refugee health. According to previous research, ineffective interactions with refugees resulted in longer office visits, delays in obtaining consent, unnecessary testing, and patient non-compliance (Betancourt, 2003). Accessibility and satisfaction with healthcare facilities are important contributors of patient satisfaction and crucial for compliance (Shahin et al., 2020).

According to the GMC, students must be aware of the variety of alternative and traditional therapies used by the patients. Graduates must be aware of the existence and range of such therapies, why some patients use them, and how they may affect other types of treatment that patients are receiving from the NHS (Outcomes for graduates, 2018). Refugees and asylum seekers have unique health needs concerning mental health support. Mental health support, maternity care, chronic conditions, and untreated communicable diseases. One in every three refugees and asylum seekers suffers from depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), torture, female genital mutilation (FGM) and sexual and gender-based violence. Maternity care needs in refugees include malnutrition, late presentation, FGM complication and trauma (Harakow et al., 2021). Chronic conditions such as poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes, and epilepsy and untreated communicable diseases including tuberculosis, HIV/STI and parasitic infections are seen among refugee populations (Shahin et al., 2021).

A longitudinal refugee curriculum for medical and dental students should be a collaborative process which is student led and tutor supported with participation of the refugee community as equal stakeholders (Bernhardt et al., 2019; Sharman et al., 2021; Figure 2). The collaborative approach to curriculum design has proven to be highly effective, and the inclusion of the refugee community can add authenticity while also promoting sensitive and respectful discussion (Strange et al., 2018). This mixed-method study contributes to the growing literature that demands for refugee and asylum-seeker health to be integrated into the undergraduate medical curriculum. It is the first study to do so through the lens of students, educators and professionals in the field of refugee health. Future work in this area should incorporate views and ideas from further members of the faculty including deans of medical faculties and year leads for undergraduate students to further substantiate this cause and investigate methods by which this topic can be introduced and taught to students.

A mixed-method approach was used to understand the need for refugee and asylum seeker’s curriculum in medical and dental education in UK. The study obtained opinions from teachers and students on the importance of including refugee health topics in undergraduate curricula. However, the study focused mainly on the key informants based in Kings College London, thus restricting the views from other medical educators based in UK. In conclusion, teaching about refugee health will benefit all underserved populations, not just refugees. A collaborative model that includes students, teachers, and refugees as equal stakeholders will improve the quality and effectiveness of curricula while increasing the likelihood of developing equitable healthcare in the UK.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The study was reviewed and approved by King’s College London Research Ethics Committee (Ref no: MRSU-21/22-32613). Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from the participants.

RP contributed to the data acquisition and writing of the manuscript. WJ contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, proposal development, formal analysis, result interpretation, manuscript preparation, and finalization for submission to the journal. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Kings Undergraduate Research Fellowship (KURF).

We would like to thank all the participants who took out time and provided their valuable contributions to this project. We would also like to thank Litty Johnson, University of Salzburg for her valuable input in composing the manuscript and providing feedback.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Altshuler, L., Sussman, N. M., and Kachur, E. (2003). Assessing changes in intercultural sensitivity among physician trainees using the intercultural development inventory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 27, 387–401. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(03)00029-4

Anderson, K., Sykes, M., and Fisher, P. (2007). Medical students and refugee doctors: learning together. Med. Educ. 41, 1105–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02886.x

Asif, Z., and Kienzler, H. (2022). Structural barriers to refugee, asylum seeker and undocumented migrant healthcare access. Perceptions of Doctors of the world caseworkers in the UK. SSM Mental Health 2:100088. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2022.100088

Bansal, N., Karlsen, S., Sashidharan, S. P., Cohen, R., Chew-Graham, C. A., and Malpass, A. (2022). Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK: a meta-ethnography. PLoS Med. 19:e1004139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004139

Bernhardt, L. J., Lin, S., Swegman, C., Sellke, R., Vu, A., Solomon, B. S., et al. (2019). The refugee health partnership: a longitudinal experiential medical student curriculum in refugee/asylee health. Acad. Med. 94, 544–549. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002566

Betancourt, J. R. (2003). Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad. Med. 78, 560–569. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00004

BMA (2022). Unique health challenges for refugees and asylum seekers UK. BMA Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/ethics/refugees-overseas-visitors-and-vulnerable-migrants/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-patient-health-toolkit/unique-health-challenges-for-refugees-and-asylum-seekers.

Burnett, A., and Peel, M. (2001). Asylum seekers and refugees in Britain: health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. Br. Med. J. 322, 544–547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7285.544

Chiarenza, A. (2019). Challenges and opportunities for health professional providing care for refugees and migrants. Eur. J. Pub. Health 29:ckz185.716. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.716

Dotchin, C., Van Den Ende, C., and Walker, R. (2010). Delivering global health teaching: the development of a global health option. Clin. Teach. 7, 271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00394.x

Dowell, A., Crampton, P., and Parkin, C. (2001). The first sunrise: an experience of cultural immersion and community health needs assessment by undergraduate medical students in New Zealand. Med. Educ. 35, 242–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00772.x

Drennan, V. M., and Joseph, J. (2005). Health visiting and refugee families: issues in professional practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 49, 155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03282.x

Dussán, K. B., Galbraith, E. M., Grzybowski, M., Vautaw, B. M., Murray, L., and Eagle, K. A. (2009). Effects of a refugee elective on medical student perceptions. BMC Med. Educ. 9, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-15

Ðuzel, G., Krišto, T., Parèina, M., and Šimunoviæ, V. J. (2003). Learning through the community service. Croat. Med. J. 44, 98–101.

Ekblad, S., Mollica, R. F., Fors, U., Pantziaras, I., and Lavelle, J. (2013). Educational potential of a virtual patient system for caring for traumatized patients in primary care. BMC Med. Educ. 13, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-110

Gjerde, C. L., and Rothenberg, D. (2004). Career influence of an international health experience during medical school. Fam. Med. 36, 412–416.

Godkin, M. A., and Savageau, J. A. (2001). The effect of a global multiculturalism track on cultural competence of preclinical medical students. Fam. Med. 33, 178–186.

Goez, H., Lai, H., Rodger, J., Brett-MacLean, P., and T, H. (2020). The DISCuSS model: creating connections between community and curriculum–a new lens for curricular development in support of social accountability. Med. Teach. 42, 1058–1064. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1779919

Griswold, K., Kernan, J. B., Servoss, T. J., Saad, F. G., Wagner, C. M., and Zayas, L. E. (2006). Refugees and medical student training: results of a programme in primary care. Med. Educ. 40, 697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02514.x

Griswold, K., Zayas, L. E., Kernan, J. B., Wagner, C. M., and Health, M. (2007). Cultural awareness through medical student and refugee patient encounters. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 9, 55–60. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9016-8

Gruner, D., Feinberg, Y., Venables, M. J., Shanza Hashmi, S., Saad, A., Archibald, D., et al. (2022). An undergraduate medical education framework for refugee and migrant health: curriculum development and conceptual approaches. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03413-8

Gruner, D., Pottie, K., Archibald, D., Allison, J., Sabourin, V., Belcaid, I., et al. (2015). Introducing global health into the undergraduate medical school curriculum using an e-learning program: a mixed method pilot study. BMC Med. Educ. 15, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0421-3

Harakow, H. I., Hvidman, L., Wejse, C., and Eiset, A. H. (2021). Pregnancy complications among refugee women: a systematic review. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 100, 649–657. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14070

Hudelson, P., Junod Perron, N., and Perneger, T. V. (2010). Measuring physicians’ and medical students’ attitudes toward caring for immigrant patients. Eval. Health Prof. 33, 452–472. doi: 10.1177/0163278710370157

Isaacs, A., Burns, N., Macdonald, S., and O’Donnell, C. A. (2020). ‘I don’t think there’s anything I can do which can keep me healthy’: how the UK immigration and asylum system shapes the health and wellbeing of refugees and asylum seekers in Scotland. Crit. Public Health 32, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2020.1853058

Johnson, D. R., Burgess, T., and Ziersch, A. M. (2008). I don’t think general practice should be the front line: experiences of general practitioners working with refugees in South Australia. Aust. N. Z. Health Policy 5, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-5-20

Ko, M., Edelstein, R. A., Heslin, K. C., Rajagopalan, S., Wilkerson, L., Colburn, L., et al. (2005). Impact of the University of California, Los Angeles/Charles R. Drew University medical education program on medical students’ intentions to practice in underserved areas. Acad. Med. 80, 803–808. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00004

Kulkarni, A., Francis, E. R., Clark, T., Goodsmith, N., and Fein, O. (2014). How we developed a locally focused global health clinical preceptorship at Weill Cornell Medical College. Med. Teach. 36, 573–577. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.886764

Laven, G., and Newbury, J. W. (2011). Global health education for medical undergraduates. Rural Remote Health 11, 268–273. doi: 10.22605/RRH1705

Lebano, A., Hamed, S., Bradby, H., Gil-Salmerón, A., Durá-Ferrandis, E., Garcés-Ferrer, J., et al. (2020). Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health 20, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08749-8

Levine, S., and Serdah, M. (2020). A novel resident and medical student curriculum in refugee health. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 2237–2239. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05693-6

Mawani, F. N. (2014). “Social determinants of refugee mental health” in Refuge and resilience: promoting resilience and mental health among resettled refugees and forced migrants (New York, NY: Springer), 27–50.

Merritt, K., and Pottie, K. (2020). Caring for refugees and asylum seekers in Canada: early experiences and comprehensive global health training for medical students. Can Med Educ J. 11:e138. doi: 10.36834/cmej.69677

Mohamed-Ahmed, R., Daniels, A., Goodall, J., O'Kelly, E., and Fisher, J. (2016). ‘Disaster day’: global health simulation teaching. Clin. Teach. 13, 18–22. doi: 10.1111/tct.12349

NHS. NHS entitlements: migrant health guide UK: office for Health Improvement and Disparities. (2014). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/nhs-entitlements-migrant-health-guide.

Nolan, H. A., and Roberts, L. (2021). Medical educators’ views and experiences of trigger warnings in teaching sensitive content. Med. Educ. 55, 1273–1283. doi: 10.1111/medu.14576

Ormerod, L. P. (1990). Tuberculosis screening and prevention in new immigrants 1983–88. Respir. Med. 84, 269–271. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(08)80051-0

Outcomes for graduates (2018). Available at: https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/standards-and-outcomes/outcomes-forgraduates (Accessed April 8, 2023).

Paisi, M., Baines, R., Burns, L., Plessas, A., Radford, P., Shawe, J., et al. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to dental care access among asylum seekers and refugees in highly developed countries: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health 20, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01321-1

Pottie, K., and Hostland, S. (2007). Health advocacy for refugees: medical student primer for competence in cultural matters and global health. Can. Fam. Physician 53, 1923–1926.

Puthoopparambil, S. J., Phelan, M., and MacFarlane, A. (2021). Migrant health and language barriers: uncovering macro level influences on the implementation of trained interpreters in healthcare settings. Health Policy 125, 1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.05.018

Rashid, M., Cervantes, A. D., and Goez, H. (2020). Refugee health curriculum in undergraduate medical education (UME): a scoping review. Teach. Learn. Med. 32, 476–485. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2020.1779071

Ryan, K. T., Tsai, P.-Y., Welch, G., and Zabler, B. (2020). Online clinical learning for interprofessional collaborative primary care practice in a refugee community-centered health home. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 20:100334. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2020.100334

Samkange-Zeeb, F., Samerski, S., Doos, L., Humphris, R., Padilla, B., and Bradby, H. (2020). “It’s the first barrier”–lack of common language a major obstacle when accessing/providing healthcare services across Europe. Front. Sociol. 5:557563. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.557563

Schonholz, S. M., Edens, M. C., Epié, A. Y., Kligler, S. K., Baranowski, K. A., and Singer, E. K. (2020). Medical student involvement in a human rights program: impact on student development and career vision. Ann. Glob. Health 86:130. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2940

Seeleman, C., Suurmond, J., and Stronks, K. (2009). Cultural competence: a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Med. Educ. 43, 229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03269.x

Shahin, W., Kennedy, G. A., Cockshaw, W., and Stupans, I. (2020). The role of medication beliefs on medication adherence in middle eastern refugees and migrants diagnosed with hypertension in Australia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 14, 2163–2173. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S274323

Shahin, W., Stupans, I., and Kennedy, G. (2021). Health beliefs and chronic illnesses of refugees: a systematic review. Ethn. Health 26, 756–768. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1557118

Sharman, M., Clark, E., Gure-Klinke, H., Player, E., and Clarry, C. (2021). Medicine on the margins: learning opportunities for undergraduates within inclusion health. Educ. Prim. Care 32, 56–58. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2020.1812439

Spallek, J., Zeeb, H., and Razum, O. (2011). What do we have to know from migrants’ past exposures to understand their health status? A life course approach. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 8, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-8-6

Stagg, H. R., Jones, J., Bickler, G., and Abubakar, I. (2012). Poor uptake of primary healthcare registration among recent entrants to the UK: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2:e001453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001453

Strange, J., Shakoor, A., and Collins, S. (2018). Understanding inclusion health: a student-led curriculum innovation. Med. Educ. 52, 1195–1196. doi: 10.1111/medu.13713

Suurmond, J., Seeleman, C., Rupp, I., Goosen, S., and Stronks, K. (2010). Cultural competence among nurse practitioners working with asylum seekers. Nurse Educ. Today 30, 821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.03.006

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

UNHCR. Convention relating to the status of refugees. (2010). Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/protect/PROTECTION/3b66c2aa10.pdf.

UNHCR. Asylum seeker trends 2014. (2015). Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/551128679/asylum-levels-trends-industrialized-countries-2014.html.

UNHCR. Mid-year trends 2021: the UN refugee agency. (2021). Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/618ae4694/mid-year-trends-2021.html.

WHO. Refugee and migrant health Geneva. (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/.

Willey, S., Desmyth, K., and Truong, M. (2022). Racism, healthcare access and health equity for people seeking asylum. Nurs. Inq. 29:e12440. doi: 10.1111/nin.12440

Wros, P., and Archer, S. (2010). Comparing learning outcomes of international and local community partnerships for undergraduate nursing students. J. Community Health Nurs. 27, 216–225. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2010.515461

Yankey, T., and Biswas, U. N. (2012). Life skills training as an effective intervention strategy to reduce stress among Tibetan refugee adolescents. J. Refug. Stud. 25, 514–536. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fer056

Keywords: United Kingdom, health education, cultural competency, community health, barriers

Citation: Pittala R and Jacob W (2023) The need for inclusion of integrated teaching on refugee and asylum seeker health in undergraduate medical curriculum. Front. Educ. 8:1033388. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1033388

Received: 31 August 2022; Accepted: 02 May 2023;

Published: 18 May 2023.

Edited by:

Anette Wu, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Nicholas Freestone, Kingston University, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Pittala and Jacob. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wright Jacob, amFjb2Iud3JpZ2h0QGtjbC5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.