- Department of English Language, College of Sciences and Arts in Methnab, Qassim University, Buraydah, Saudi Arabia

As English has become the preferred language for recording current innovation and technological breakthroughs, text is the essential medium through which EFL learners enhance their writing abilities. Desirable though it may be, the researcher's experience has shown that most male students have just rudimentary L2 writing skills and are unable to write coherent passages in English. This implies a chasm between learners' lexical and cohesive connections and earlier research has focused on ways and means to bridge this gap. However, the current study is ground-breaking in this field as it explores the efficacy of task-oriented training in filling this chasm. Using linguistic learning methods, the current research examines the efficacy of lexical and cohesive links in enhancing undergraduates' writing. The study sample comprises 35 learners from an intermediate EFL reading class who are exposed to an intervention lasting 15 weeks. Data analysis shows that in the post-test, the learners' grammatical and vocabulary skills are enhanced dramatically, particularly in the discourse analysis sections. Furthermore, during group work activities, (i) students are more engaged and motivated, and they acquire more knowledge about the language system, identification, cause and effect, “if” clause and the purpose and function of using the passages given; (ii) half of the students' grammar proficiency and use of lexical items was correct in the writing output. Finally, the study shows that the biggest obstacle that the students faced in their writings and which they struggle to master is the use of the “if” clause which only 13 students could finally master. In addition, the study shows that (73%) of the students could master the discursive linkers in their writings better than the lexical or grammatical elements. Ultimately, the present study offers practical consequences that EFL teachers may want to contemplate including in their future classes.

Introduction

TBLT has captured the interest of English language instructors and teachers over the last years. For the last 35 years, language trainers have obtained task-based language teaching (henceforth, TBLT) in the teaching settings. This technique considers an approach to language education that places language training at the core of curriculum and learning goals (Youn, 2018; Ho, 2020; Mishra and Natalizio, 2020). In the same vein, Sundari et al. (2018) stated that using TBLT had magnificent benefits on students' writing. In today's world, education presents students with unique opportunities for innovation and improvement in their learning experience. Research has shown that classroom learning is found engaging by learners if it is innovative and entertaining for them, especially for the learners from remote areas. The sophisticated technique of classroom instruction will provide a level playing field for active learning. Teaching assignments in the classroom place a premium on the requirements and abilities of the students in order to help them improve their language skills. English is the medium of instruction for undergraduate education, and it continues to be the language required for careers in business and other sectors. It is essential to increase practicability for students and enhance the educational experience which must be learner-centered.

Several studies reported on the importance of TBLT in developing EFL students' abilities (Ziegler, 2016; Nguyen and Walkinshaw, 2018; Al-Tamimi et al., 2020). Al-Tamimi et al. (2020) found that TBLT enhanced Yemeni EFL students' speaking and reduced their perception of classroom challenges. Similarly, Nguyen and Walkinshaw (2018), claimed that TBLT represented a process of negotiation, adaptation, rephrasing, and experimenting at the core of second language acquisition. Moreover, Tang (2019) mentioned that TBLT encouraged instructors and pupils to initiate the learning process without questioning where they will be and why they are there.

In the contemporary tech-charged learning environments, instructors must be prepared to cope successfully with changing teaching methods, therefore TESOL instruction must be structured to match their needs (Albelihi and Al-Ahdal, 2021). Every instructor at all educational levels should be required to participate in the training and skill enhancement programs. Instead of being oriented on the instructor, this orientation should be centered on the students. The speech should not be seen as a basic educational course curriculum, but rather as an efficient communicating instrument with practical usefulness in real-life circumstances. To break up the monotony and pique learners' attention, the most up-to-date techniques of leveraging technology in the classroom and gadgets to boost learning should be presented, coupled with creative classroom instruction.

Regrettably, some universities lack the required equipment for learning a language, such as audio-visual aids which facilitate the student's acquisition of the language, and they feel completely alienated from their culture. As a result, teaching at such institutions is difficult and far from achieving learning objectives. At the teachers' level, there is a dire need for platforms that allow for sharing of knowledge and experience as the ultimate beneficiaries are the students, and such combined resources will also help teachers prepare their students so that they are more valued in the job market. This endeavor may attract the attention of a large number of language instructors who are eager to accept innovative approaches and techniques in classroom teaching, leaving behind established practices.

Review of the literature

Task-based-teaching

According to Gan and Leung (2020), TBLT is an ingenious technique in which instructor's engagement and practical demonstration are required. It teaches language using a process approach and obtains the communicative approach for language teaching and instructional objectives (Youn, 2018; Ho, 2020; Mishra and Natalizio, 2020). Similarly, Teng and Zhang (2020) stated that practicing the language with a task is intentionally inclined to provide learners with an experience learning process in which they acquire the skills of language as an opportunity for practice, and this productive language process will stimulate and enhance the learners' language learning abilities.

According to the theory of TBLT, learning English is not a conceptualization and formation the language, it is a process a communication. In a similar vein, Nguyen and Walkinshaw (2018) stated that tasks are seen to represent an act of negotiation, adaptation, rephrasing, and experimenting while processing the acquision of the language. Tang (2019) explained that instructors and pupils engaged in TBLT need to forget where they will be and why they are there.

Tasks, according to TBLT, are an important component in the second language classroom because they offer settings for promoting student acquisition processes and aiding L2 learning (Al-Gahtani and Roever, 2018; Skehan and Luo, 2020). With the advent and use of technology in scope of education generally, and in language learning, a new concept i.e., “task-based technology” was introduced to EFL/ESL classrooms. The idea of successful learning is attained in case of learners who fully collaborate in the activities. Thus, communication and technology expand the number of academic tasks due to the availability of a large resources of internet (Järvi et al., 2018; Pérez-Paredes et al., 2019; Belina, 2020; Chen, 2021), improve the credibility of duties and provide encouragement for having to implement an assignment in the school environment (Lan, 2020; Masuram and Sripada, 2020), and they simplify the students' participations in the tasks (Kalmykova et al., 2018; Deng et al., 2019; Fedorenko et al., 2019; Lan, 2020; Masuram and Sripada, 2020).

Meanings and forms in task-based learning

Learners may acquire a lot of vocabulary when writing paragraphs in the learning settings. Such learning environment is accessible in active sessions in the classrooms with no presenting of frameworks or rubrics and no incentive for students to actualize themselves. It is claimed that an analytical course and linguistic structure are derived from the learners' goals (Coccetta, 2018). When there is a communication failure, the emphasis of communication shifts from meaning to form. Many abilities are utilized to achieve this purpose, such as “recasts,” in which the instructor delivers a corrective restatement of the student's faulty discourse production or comprehension (Chen and Kent, 2020).

TBLT participates in the development of language by evolving form from meaning. Taking this objective seriously, instructors must first encourage the practicing of language communication in the classroom as much as possible without paying more concern to accuracy. Furthermore, the initial stage, i.e., the phase of focusing on form allows students to look in depth at some of the grammar rules that have been employed in the classroom. Hence, before the emphasis on grammar rules occurred, the students had encountered the use of language in context which helps them to comprehend the modern language.

To help learners complete tasks and demonstrate their analytical competency of statement in classroom time and real-life circumstances, assignments must be appropriate to real-life scenarios (Byström and Kumpulainen, 2020). Furthermore, task kinds need to include variety such as image tales, riddles, and puzzles (Foster and Stagl, 2018) discussions, and debates (Foster and Stagl, 2018; Nguyen and Walkinshaw, 2018) and daily functions such as service interactions and phone calls (Nguyen and Walkinshaw, 2018). These assignments are useful learning exercises in the classroom.

Based on the preceding review of literature, the following research questions guide this study

• To what extent do TBLT enabled students use lexical items in their writing correctly?

• What are the elements of grammar that TBLT did not develop in the students?

• Which are the linguistic and discursive areas that TBLT helped students to master better in their writings?

Methodology

This study followed a content analysis methodology to analyse students' written output. The researcher divided the written texts into four sections: behavioral psychology, scientific research, and two general sections. Furthermore, the evaluation and analysis were focused on three aspects: lexicon, grammar/syntax, and discourse (direct and inferential). Synonyms, antonyms, one-word substitution, idioms, and word structure with affixes were included under the category lexis. The second portion (Grammar and Syntax) focuses on tense identification and usage, as well as structural distinctions, such as distinguishing “cause and effect,” “purpose and function,” “if clause,” and “passive” statements from passages. Deductive reasoning and message problems were provided in the third section to test students' ability to think of the consequences, anticipate, and grasp the paragraph tied to specific cues.

Participants

The participants in this research were 35 students chosen at random from a class of 54. The participants are joiner students enrolled in English writing course at College of Language and Arts, Qassim University. All participants were Saudi nationals and had duly studied English at primary and secondary school levels. Participants' consent was sought by the researcher after they were assured of the purpose of the data being collected.

Procedures

The students were asked to write two paragraphs at the start of the activity, which were then collected as data by the researcher. The investigator then read each paragraph and made a remark at the conclusion of each one. The feedback boosts self-esteem and enhances reading ability. The researcher, on the other hand, made no mention of the grammatical errors or the terminology used (aiming to help them write without interruption). The learners were given feedback on the exercise during the next class hour, and they were encouraged to continue composing paragraphs. The researcher identified the major characteristics of coherent devices and lexical elements in students' compositions in the classroom. He discussed which of their written sections he enjoyed the most and which he disliked the most along with the reasons in either case.

The lecture group discussion lasted no more than 20 min, during which students discussed the challenges they encountered throughout the work as well as the errors they could correct in the next task. The purpose of this talk was to focus on an indirect method of encouraging learners to become more engaged. Later, the group discussion was cut down to 10 min. All of the learners' written activities were gathered in the fifteenth week in order to assess the amount of output they produced and compute the remarks based on changes in writing ability, variety, and styles. The data were statistically computed into percentages, mean scores and average. The researcher also computed an average score for lexicon, morphology, and coherence.

Analysis of data and results

Lexis

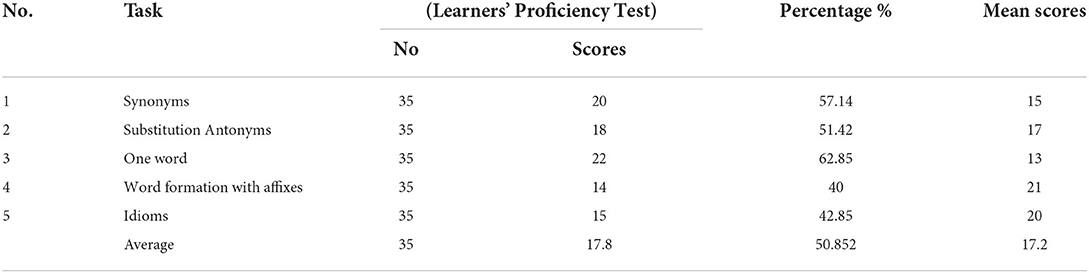

Table 1 shows learners' knowledge in lexemes. Exactly 20 students achieved success in synonyms and 22 in one-word replacement, according to the results of the sample work presented to a group of 35 students. In addition, 18 of the 35 pupils got antonyms right. Only 15 students did the idioms correctly while 14 attempted correctly the word structures with affixes. As a result, we may deduce that 20 of the 35 students who tried synonyms had a restricted vocabulary. In terms of synonyms, the word “work” may be written as “job,” while the word “tale” can be written as “story” or “narration” among other things. In the case of antonyms which are not taught as rigorously, learners' performance was poor. For example, the supplied lexicon was “annual,” “alike,” “social,” “promotion,” “literate,” for which students wrote “temporary,” “always,” “society,” “intelligent”, respectively. Data suggests that 15 out of 35 learners performed poorly in both categories due to a lack of sufficient grounding and application of communicative language expertise.

Grammar and syntax (grammatical category)

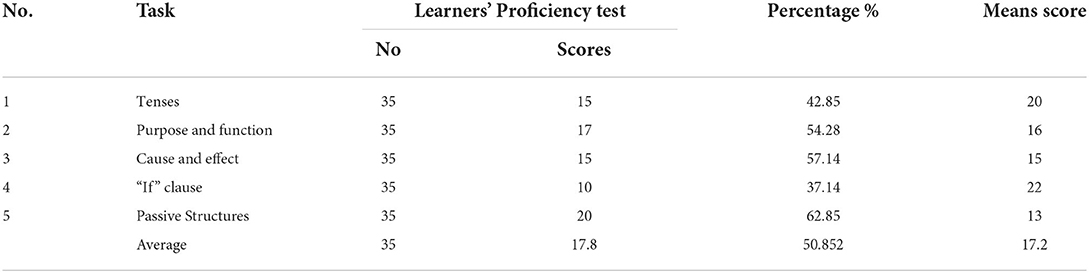

Table 2 presents students' ability in grammar and syntax. Students were assessed on “tenses,” “if” clause, “cause and effect,” “passive structures”, and “purpose and function,” in the grammatical system. According to Table 2, only 10 students fared well in the “if” clause, despite the fact that a large number of students (35) did not do well because they only had a hazy understanding of the divisions (in tense) in each category. As a result, they received a 15 on Cause and Effect and 17 on Purpose and Function. Passive Structures piqued the attendees' curiosity, and they got slightly better score of 20 points. Furthermore, they were unable to recognize and distinguish between the linkers that should be utilized for Purpose and Functions, Cause and Effect and so on. One cause for their underperformance might be the emphasis placed on solely literature throughout their education years, which left them without a take into considerations to acquiring the aforementioned notion.

Discourse

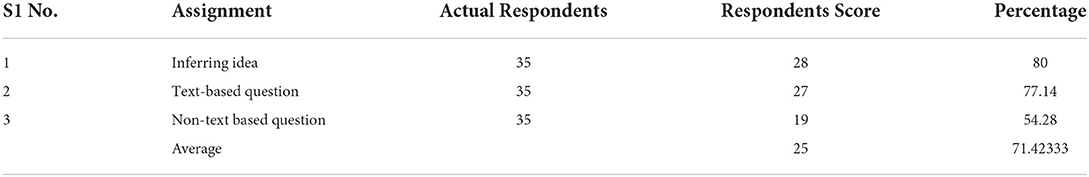

The subjects were assessed in 3 components in Table 3: 1. the inferring concept, 2. the text-based questionnaire, and 3. the non-text-based questionnaire. The respondents performed reasonably well in almost all of the activities with incentive, they scored with an average of 25 out of 35. The students in Inferring Idea scored (28) the highest, followed by got 27 in Text-based Questions, and they scored the least (19) in Non-Text-based Questions. The findings show that students answered the direct and inference questions which required them to choose words from a sentence.

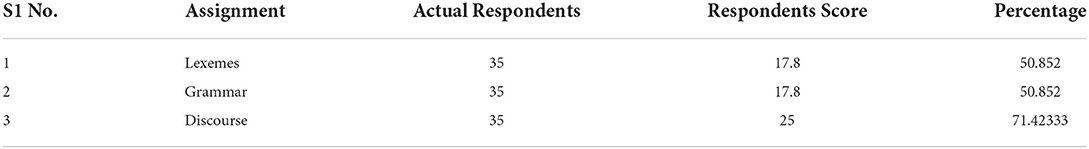

Table 4 presents the three linguistic and cohesive elements previously discussed. Table 4 shows that students scored high in the discourse elements in which 25 out of the 35 students used the cohesive connectors correctly. In other words, 71.4% of the students used the discursive linkers correctly in their writing. Furthermore, it seems that just half of the students (50.852%) of the students used the lexical items and grammar correctly in their writings.

The study analyzed the contents of students' writings according to three elements: proper use of lexicons, use of well-formed sentences and the proper use of discursive linkers. To report the first finding of the study, it is found that just half of the students use proper lexicon in their writings. This is a problem for the students. Many studies (e.g., Al-Gahtani and Roever, 2018; Skehan and Luo, 2020) showed that TBLT offered settings for promoting student acquisition processes and aiding L2 learning.

Secondly, the study also analyzed the students' proper use of grammar in their writings. To answer the second research question, the study found that half of the students faced problems in grammar in their writings, the most frequent difficulty they encountered was the proper use of “if” clause. The study found that only 13 out of 35 of the students used “if” clause correctly. This finding seemed natural because the “if” clause can be tricky for non-native speakers to master. Byström and Kumpulainen (2020) affirmed the role of associating the necessity to link the task to real-life scenarios of the students. If so, learners will complete the tasks and demonstrate their analytical competency of statement in classroom time and real-life circumstances.

Finally, the study found that students mastered the discourse linkers better than they did the grammar and lexical items. Sundari et al. (2018) reported that students who taught writing through TBLT scored higher their counterparts who traditionally taught. The development was found in, organization, content, and grammar. Furthermore, Byström and Kumpulainen (2020) pointed out that the undertaking framework is as a concept that included pre-task (subject and task introduction), task cycle (activity, preparation, and reporting), and language emphasis (practice and analysis). It enables students to concentrate on the meaning in the first two stages by employing whatever little vocabulary they have, and just in the three stages. Regular chances to employ the cohesive markers and practice the language skills needed in real life. Such abilities are provided by involving students in relevant activities. Students are motivated by tasks because they desire to complete them. Students tend to acquire the language they need. Most crucially, language concentrates on the last stage, which prohibits learners' knowledge from being fossilized and allows them to strengthen their language abilities. Based on the study findings it is difficult to report precisely to what extent the TBLT promoted students' writing ability in the three discussed areas (lexemes, grammar, and discourse) because of the study design. This will be discussed in the limitation section.

The study showed that involving learners in activities and giving them opportunities to use the language communicatively in the classroom boosts their confidence as well as removes their anxiety of making errors as they begin to examine the language.

Advanced writings are often heavier and convey more complicated material than ordinary texts. They are nevertheless believed to be intelligible with minimal ambiguity. The function of discourse structure in text is one of the key reasons for this notion. The exam highlights the fact that graduate level learners need exposure and should be provided with discourse knowledge in order to improve their analytical and logical approach.

The problem for teachers using task-based strategies in the EFL classroom is determining how to choose and carry out assignments that strike a balance across form and meaning. Overall, the researcher's intervention using self-created TBLL assignments were extremely successful. The students stayed busy and interested in the assignments. However, in order to build their interlanguage system, students must confront the difficulty of speaking in front of the entire class.

Conclusions

The current study used the task-based language learning approach to analyse lexical and cohesive ties utilization in undergraduate students' writing. Thirty-five students were chosen at random for this research and tested over the course of 15 weeks. The study found that after students learnt writing for a semester through TBLT, at least half of the students used lexicon and grammar correctly in their writings. The participants demonstrated remarkable improvement in using the discursive linkers in their writings. In grammar, the study reported that the majority of students could not use the “if” clause correctly. Hence it was concluded that the TBLT enhanced students' discourse skills, as well as the use of discourse analysis tools to expand their understanding of how to interpret any piece, though the extent of improvement could not be determined. As a result, these ideas may assist task-based innovations for EFL students in both task-based classes and in other contexts where TBLL is an innovative device for comprehending course outcomes. To improve the successful classroom atmosphere, language instructors might adopt the aforementioned tactics in EFL classrooms.

Recommendations

The students employed lexicons, cohesive markers, and group assignments to communicate the interpretation of written texts throughout the group discussion. The participants successfully demonstrated these organizational frameworks. Based on the findings, the study recommends that EFL learners' understanding be boosted via strategy training. Real comprehension teaching provided by involving students to participate in clarifying, predicting, inquiry, evaluating, and recognizing text organizations can enhance their writing in English.

Two, learners must rehearse the language with an emphasis on correctness and fluency. Giving them time to organize the composition helps them to carefully plan about their writing. This encourages learners to inquire about just the expressions they need, increasing their chances of learning it.

Finally, there is a pressing necessity to reinvent and re-shape classroom education from a conventional technique to a participatory one method (learner-centered), which forces learners to internalize and activate the language patterns learnt in the learning settings. Language courses have to be altered, rebuilt, and modified on a regular basis to reflect modifications in English language use as well as shifting needs of the market.

Limitations

The study only measured students' linguistic and discursive elements at the end of the semester, so it is not wise to say that students' writing abilities developed because we did not know how their writings level was before the treatments. Therefore, a pre and post experimental design with two groups may be more reliable to determine whether TBLT was effective in developing students' writing or not. Furthermore, classroom action research may be the best solution to bring practical solutions to students' writing problems during short times. Hence, a classroom design is required to reinvent practical solutions for enhancing EFL students' writings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The researcher would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University for funding the publication of this project.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albelihi, H. H. M., and Al-Ahdal, A. A. M. H. (2021). EFL students' writing performance: a study of the role of peer and small-group feedback. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 17, 2224–2234

Al-Gahtani, S., and Roever, C. (2018). Proficiency and preference organization in second language refusals. J. Pragmat. 129, 140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2018.01.014

Al-Tamimi, N. O. M., Abudllah, N. K. M., and Bin-Hady, W. R. A. (2020). Teaching speaking skill to EFL college students through task-based approach: problems and improvement. Br. J. Engl. Linguist. 8, 113–130. doi: 10.36655/jetal.v2i1.266

Belina, B. (2020). Political geography lecture: social forms, spatial forms, and the new right. Celebrating capital at 150 and explaining the rise of the AfD. Polit. Geogr. 81:102091. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102091

Byström, K., and Kumpulainen, S. (2020). Vertical and horizontal relationships amongst task-based information needs. Inf. Process. Manage. 57:102065. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102065

Chen, J. C., and Kent, S. (2020). Task engagement, learner motivation and avatar identities of struggling English language learners in the 3D virtual world. System 88:102168. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.102168

Chen, K. T. C. (2021). The effects of technology-mediated TBLT on enhancing the speaking abilities of university students in a collaborative EFL learning environment. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 12, 331–352. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2018-0126

Coccetta, F. (2018). Developing university students' multimodal communicative competence: field research into multimodal text studies in English. System 77, 19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.01.004

Deng, R., Benckendorff, P., and Gannaway, D. (2019). Progress and new directions for teaching and learning in MOOCs. Comput. Educ. 129, 48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.019

Fedorenko, E., Ivanova, A., Dhamala, R., and Bers, M. U. (2019). The language of programming: a cognitive perspective. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.04.010

Foster, G., and Stagl, S. (2018). Design, implementation, and evaluation of an inverted (flipped) classroom model economics for sustainable education course. J. Clean. Prod. 183, 1323–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.177

Gan, Z., and Leung, C. (2020). Illustrating formative assessment in task-based language teaching. ELT J. 74, 10–19. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccz048

Ho, Y. Y. C. (2020). Communicative language teaching and English as a foreign language undergraduates' communicative competence in Tourism English. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tourism Educ. 27:100271. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2020.100271

Järvi, K., Almpanopoulou, A., and Ritala, P. (2018). Organization of knowledge ecosystems: prefigurative and partial forms. Res. Policy 47, 1523–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.05.007

Kalmykova, Y., Sadagopan, M., and Rosado, L. (2018). Circular economy–from review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycling 135, 190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.10.034

Lan, Y. J. (2020). Immersion into virtual reality for language learning. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 72, 1–26. doi: 10.1016/bs.plm.2020.03.001

Masuram, J., and Sripada, P. N. (2020). Developing spoken fluency through task-based teaching. Procedia Comput. Sci. 172, 623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2020.05.080

Mishra, D., and Natalizio, E. (2020). A survey on cellular-connected UAVs: design challenges, enabling 5G/B5G innovations, and experimental advancements. Comput. Netw. 182:107451. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2020.107451

Nguyen, X. N. C. M., and Walkinshaw, I. (2018). Autonomy in teaching practice: insights from Vietnamese English language teachers trained in Inner-Circle countries. Teach. Teach. Educ. 69, 21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.015

Pérez-Paredes, P., Guillamón, C. O., Van de Vyver, J., Meurice, A., Jiménez, P. A., Conole, G., et al. (2019). Mobile data-driven language learning: affordances and learners' perception. System 84, 145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.06.009

Skehan, P., and Luo, S. (2020). Developing a task-based approach to assessment in an Asian context. System 90:102223. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102223

Sundari, H., Febriyanti, R. H., and Saragih, G. (2018). Using task-based materials in teaching writing for EFL classes in Indonesia. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 7, 119–124. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.3p.119

Tang, X. (2019). The effects of task modality on L2 Chinese learners' pragmatic development: computer-mediated written chat vs. face-to-face oral chat. System 80, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.10.011

Teng, L. S., and Zhang, L. J. (2020). Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: can self-regulated learning strategies-based writing instruction make a difference?. J. Second Lang. Writing 48:100701. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2019.100701

Youn, S. J. (2018). Task-based needs analysis of L2 pragmatics in an EAP context. J. Engl. Acad. Purposes 36, 86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.10.005

Keywords: EFL writing, linguistics, TBLT (task-based language teaching), undergraduate, lexical and cohesive, academic writing

Citation: Albelihi HHM (2022) Lexical and cohesive links in EFL learners' writing: Exploring the use of task based language teaching. Front. Educ. 7:996171. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.996171

Received: 17 July 2022; Accepted: 10 August 2022;

Published: 09 September 2022.

Edited by:

Hassan Ahdi, Global Institute for Research Education & Scholarship, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Tahirah Yasmin, Quaid-i-Azam University, PakistanAamir Khan Wahocho, Quaid-i-Azam University, Pakistan

Copyright © 2022 Albelihi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hani Hamad M. Albelihi, h.albelihi@qu.edu.sa

Hani Hamad M. Albelihi

Hani Hamad M. Albelihi