94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 06 October 2022

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.994527

This article is part of the Research TopicServing Vulnerable and Marginalized Populations in Social and Educational ContextsView all 26 articles

Increasing numbers of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are pursuing postsecondary education opportunities, including college degree programs. Many receive supports and accommodations from their college accessibility service office. In this study, results of an online survey completed by 147 college accessibility services personnel summarized their perceptions of the facilitators and barriers faced by college students with ASD. Descriptive statistics and qualitative coding procedures were utilized to analyze the data. The participants indicated that the academic preparation of college students with ASD varies. Respondents believed that the most important facilitators of success were the presence of appropriate executive function, social, and self-determination/self-advocacy skills in students, and the absence of these skills was reported as a major barrier to the success of college students with ASD. Respondents also believed that the students’ ability to self-advocate, make independent decisions, self-regulate behaviors, and use appropriate coping and study strategies facilitate the success of college students with ASD. Implications of these findings and suggested directions for future research are offered.

A small body of research has emerged over the last two decades focused on the college experiences of individuals with Autism (Gelbar et al., 2014; Kuder and Accardo, 2018; Anderson et al., 2019). Students with ASD can benefit greatly from the variety of accessibility services offered at their colleges (Anderson et al., 2018) and approximately 55 of American colleges now offer programs specifically designed to support students with ASD, according to Viezel et al. (2020). College bound students with ASD, however, are often hesitant to disclose their ASD to receive services (Frost et al., 2019). It is important for educators to understand the strengths and challenges these students bring to college in order to enhance their mental health, sense of belonging, and academic success in college.

Accessibility Servicers Providers (ASPs) on college campuses play a crucial role in supporting college students with ASD. Research has demonstrated that ASPs are responsible for (and can critically influence) the perspectives of students, faculty, and other university staff toward ASD. These perspectives tend to be riddled with misconceptions and stigma on college campuses (Lombardi et al., 2013; Tipton and Blacher, 2014; Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2015; Evans et al., 2017).

Lalor et al. (2020) revealed ASPs may be able to better improve disability awareness of higher education faculty and staff through developing strategic relationships and collaborating with various faculty- and staff-run organizations across college campuses. Limited research exists, however, concerning the perceptions of ASPs about students with ASD. In 2012, Glennon (2016) surveyed members of the Association of Higher Education and Disability in the United States about their perceptions of the needs of college students with ASD. They reported that a majority(63%) of the 315 participants noted that their institutions struggled to provide viable supports to college students with ASD.

Knott and Taylor (2014) conducted focus groups with both staff and students to explore challenges, barriers, and supports to the progress of students with ASD in one university in the United Kingdom. Academic concerns emerged as a priority for students and staff, as did difficulties with social and communication skills, mental health, and disclosure of diagnosis. White et al. (2016) also led postsecondary education focus groups with college personnel, parents, and students with ASD to better understand the needs and challenges faced by these students. The college personnel focus groups included staff working at either 2- or 4-year academic institutions with experience working with students with ASD. Results suggested that college personnel considered it most important to learn more about how to interact with students with ASD and that “this was ranked higher in importance than “learning about prognosis and outlook” despite the fact that this was the lowest ranked area in terms of current knowledge” (White et al., 2016, p. 35). Additionally, college personnel noted that they would be very interested in receiving further training in how to access specific resources for students facing transition to college in order to better support students on the spectrum. The staff also identified a need for college students with ASD to increase their self-advocacy skills, which was not mentioned by parents or students in the study.

Elias et al. (2019) conducted focus groups with 10 high school and 10 postsecondary educators (i.e., administrators, instructors, and academic support staff) regarding their retrospective perceptions of the difficulties experienced by individuals with ASD during the transition from secondary to postsecondary environments. Participants reported that individuals with ASD had difficulties developing and sustaining interpersonal relationships as well as developing autonomy, independence, and competence. In a related study, Dymond et al. (2017) interviewed 10 parents and six university personnel regarding the types of services and supports that are important for academically successful college students with ASD. They reported having intentional transition plans, becoming familiar with the campus layouts, and connecting with disability service office before matriculation as important to fostering a successful transition to college for individuals with ASD.

A variety of services can and should be available to students with ASD at the postsecondary level given their functional impairments (Gelbar et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2017; Scheef et al., 2019). Barnhill (2016) surveyed staff at 30 college programs specifically designed to support college students with ASD, and reported that these programs commonly provided “support groups, counseling, supervised social activities, and summer transition programs” (p. 3). Research focusing on students’ needs is important to gain the perspectives of those who directly interact with students with ASD who are in college.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions of accessibility service providers and staff of programs designed for students with ASD regarding the facilitators of success and challenges experienced by students with ASD. Two research questions guided this study:

1. What do ASPs perceive as the most characteristics and common experiences of college students with ASD?

2. What do ASPs report as facilitators and barriers to success of college students with ASD?

In order to investigate these research questions, an online survey instrument was developed and sent to ASPs. Quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods were employed as described below.

The survey instrument was developed using an iterative process. First, previous systematic reviews (Gelbar et al., 2014; Kuder and Accardo, 2018; Anderson et al., 2019) were analyzed to determine potential questions. Second, the members of the research team, all of whom have extensive experience conducting survey research, utilized this information to create a draft survey. This survey was revised in order to make it parsimonious and align it with the study’s purpose and research questions.

A total of 21 questions were included on the survey (available upon request from the first author). Five demographic questions opened the survey. Participants were asked to indicate their role at the institution, and specifically whether they were a program director/coordinator or staff member at a program serving college students with disabilities. Respondents could also choose “other,” which lead to a second open-ended question that asked them to specify their role. A decision was made to include only responses from participants that currently or previously worked at a college serving students with disabilities.

The remaining questions were answered only by participants who indicated that they were a director/coordinator or staff member at a program serving college students with disabilities. The three remaining demographic questions asked respondents to provide information regarding the type (i.e., 2-year public, 2-year private, 4-year public, or 4-year private), and the institution at which they work. The next five Likert-style questions asked approximately how many individuals with ASD attended their institution, whether this number increased over the past 10 years, the percentage of increase, the percentage of college students with ASD that graduate from their institution, and whether additional fees are charged for services they provide to individuals with ASD that are not legally mandated under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and/or the Americans with Disabilities Amendments Act of 2008. The respondents were also asked to respond to nine Likert-style questions on a five-point agreement scale (i.e., strongly disagree to strongly agree) about statements regarding their perceptions of characteristics of college students with ASD that were developed based on the literature (e.g., college students with ASD come to college well-prepared to live independently). Finally, they were asked to respond to two open-ended items. The first item asked participants to indicate the three most important factors that facilitated the academic success of college students with ASD, and the second asked them to identify the three most important factors that hinder the academic success of college students with ASD.

The Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution indicated that this research did not qualify as human subjects research as the participants were being surveyed about their perceptions and no identifiable information was collected. Two recruitment sources were chosen to provide a wide sample of colleges/programs that provide support to individuals with ASD. The first source included professional staff working at college programs for individuals with ASD gathered from list developed by the College Autism Network.1 This was augmented by a list of college programs on the College Autism Spectrum website.2 The two lists were combined and the websites for the programs were searched for contact information for staff at these programs. A total of 96 potential participants were included on this list.

The second recruitment source was a database of past participants of an annual conference for college disability personnel, which has been conducted annually for over three decades. A total of 1,880 e-mails were included in this database. It is important to note that this list included some international participants.

The survey was entered into Qualtrics, which was set to ensure that potential participants were not required to answer all of the questions and that no identifiable information such as IP address or location were collected. Recruitment e-mails were distributed to both e-mail databases in the fall of 2019 and a reminder e-mail was sent 3 weeks later. When participants clicked on the hyperlink in the e-mail, they were taken to an information sheet that described the purpose of the study and had to proactively opt into the study. To be considered a complete response, the participant had to provide at least three responses to the two open-ended questions. In addition, three participant’s responses were considered incomplete because their answer to the question concerning their role indicated that they had not currently or formerly worked with students with disabilities at a college.

In the database of college autism programs, four e-mails were found to be invalid. Of the 92 valid e-mails, 54 began the survey and 41 completed it. For the database of the college disability conference participants, 27 e-mails were invalid and 412 individuals opened the e-mail. Of these, 157 began the survey and 106 completed the survey. In other words, a total of 147 participants completed enough of the survey to be considered a complete response.

In total, 113 participants indicated that they were administrators of or staff at a college program serving students with disabilities. The remaining 34 participants chose “Other” and, of these, 31 provided text indicating their role. Most of these participants (n = 22) specified that they were an administrator for or staff at a program that specifically provides services to individuals with ASD. These were coded as administrators or staff and combined with the data from the 113 participants. Across the entire sample, 96 individuals indicated they were administrators and 42 indicated that they were staff members that primarily work with individuals with disabilities. Six individuals indicated that they were faculty or general campus staff and three did not provide a response. The 113 participants who indicated they were administrators or staff at a college program serving students with disabilities completed additional demographic questions describing their institution (see Table 1). Approximately 73% of the sample worked at 4-year institutions and 71% worked at institutions with populations of between 1,000 and 15,000 students.

To address the research questions, descriptive statistics for the Likert scale items were calculated and data from the open-ended questions were analyzed using a basic interpretive qualitative methodology guided by the inductive analysis techniques described by Grbich (2013). Two members of the research team (the first two authors) independently read the transcripts from the open-ended questions and collaborated to develop codes. These codes were refined in consultation with the other members of the research team. For example, a response such as using effective organization and time management strategies resulted in a code entitled difficulties with self-regulation. A third member of the research team (the third author) independently coded 25% of the responses and provided suggestions for revising the codes, which were incorporated into the final coding scheme. A fourth member of the research team recoded the data using the final codes (the fourth author) and the third team member then independently coded an additional 25% of the responses. Interrater reliability for the coding of strengths/facilitators of success was 89.1 and 90.9% for coding the barriers across the first two authors who each coded 100% of the responses.

The majority of respondents (n = 104; 92.03%) indicated that the number of students with ASD has increased at their institution over the past 10 years. These participants were asked to estimate the percentage of the increase over this period and 97 provided an estimate. Of these, 34% (n = 33) indicated that the population of students with ASD has increased by up to 19%. Approximately 28% (n = 27) indicated that the increase was between 20 and 39% while approximately 18% (n = 18) indicated that the increase was between 40 and 59%. Nine percent (n = 9) indicated that the increase was between 60 and 79 and 10% (n = 10) reported an increase of greater than 80%. As summarized in Table 1, the majority of participants (n = 68; 60.18%) were not able to estimate the percentage of college students with ASD that had successfully graduated from their institution. Participants were also asked to indicate if they offered additional services for individuals with ASD beyond those that are legally mandated under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (e.g., services beyond basic accommodations and auxiliary aides) and 32 participants (28.3%) indicated their institution provided such services.

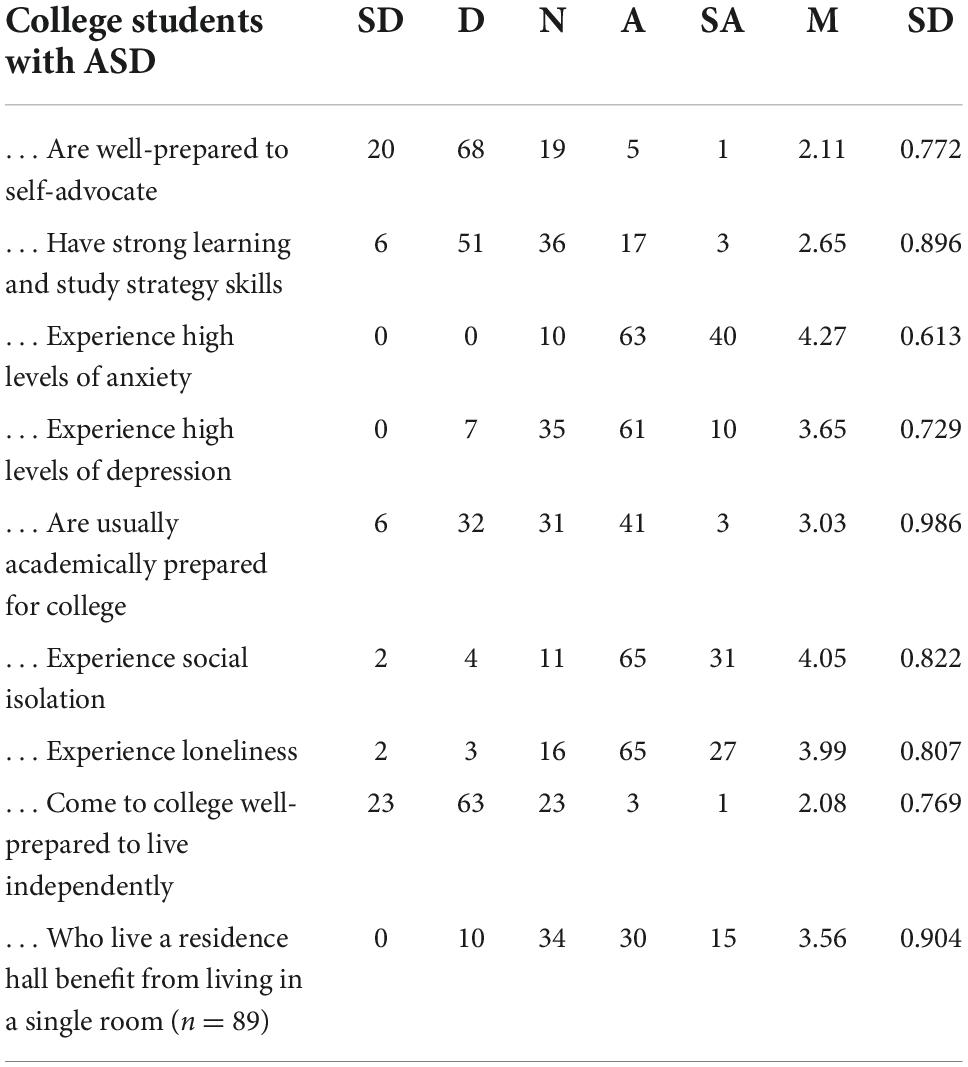

The first research question addressed respondents’ perceptions of common characteristics of college students with ASD, as summarized in Table 2. Most participants disagreed or strongly disagreed with statements that college students with ASD are well-prepared to self-advocate (77.8%), have strong learning/study strategies (50.4%), and are well-prepared to live independently (76.1%). A substantial majority of participants agreed or strongly agreed that college students with ASD experience high levels of anxiety (91.2%), social isolation (85%), loneliness (81.4%), and high levels of depression (62.8%). Responses about the academic preparation of college students with ASD varied, with approximately equal numbers agreeing (n = 44; 38.9%) and disagreeing (n = 42; 33.6%). Of the 89 participants who answered the question regarding whether college students with ASD benefit from living in a single room, half agreed or strongly agreed that this was beneficial (n = 45, 50.5%). Most of the remaining survey respondents were neutral about the perceived benefits of single rooms as an accommodation for individuals with ASD (n = 34; 38.2%).

Table 2. Distribution, mean, and standard deviation for answers to likert scale items describing the experiences of college students with ASD (n = 113).

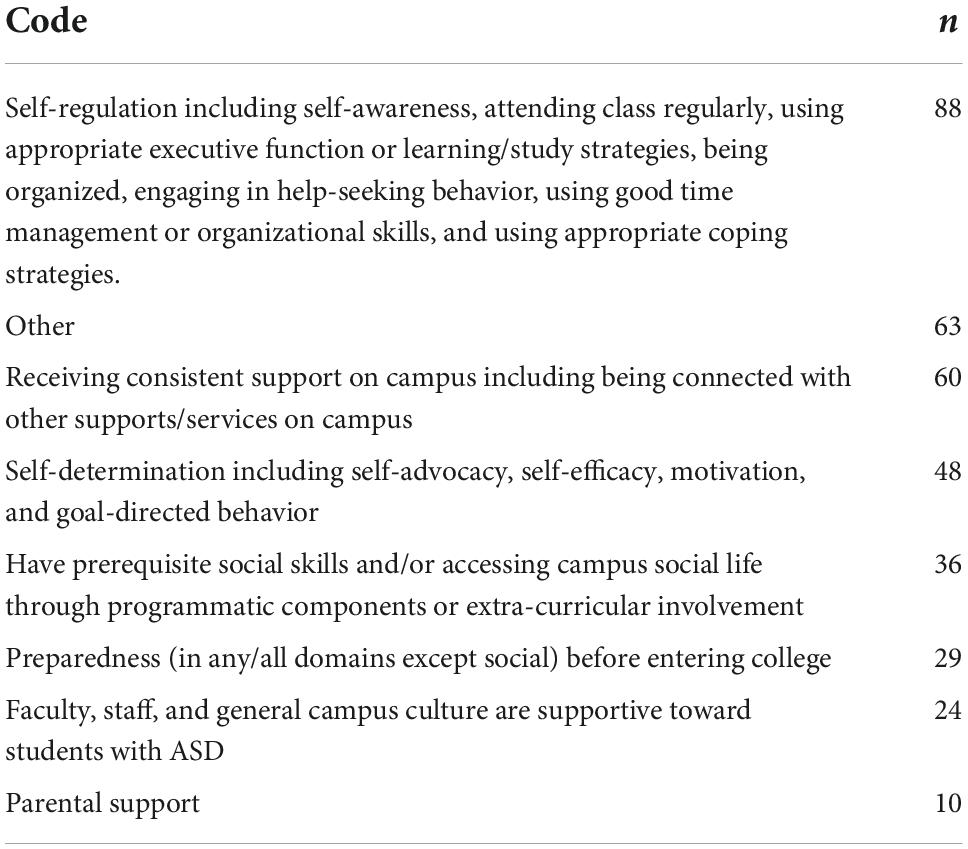

The second research question focused on the strengths/facilitators of success and barriers faced by college students with ASD. Data to address this research question were gathered from two open-ended questions that asked participants to provide up to three responses. Six responses had to be divided because two different ideas were described. At least one strength was listed by 145 participants, with a total of 436 responses. All participant responses were sorted into seven codes. Not all responses could be coded as 81 responses were vague and idiosyncratic, such as one-word responses that were very unclear, such as “access,” “sleep,” or “denial.” The data from the remaining 355 responses aligned with the coding schema. As a participant could provide multiple responses with the same code, data are reported at the participant-level, not the response-level. The most common strength code (summarized in Table 3), indicated the importance of having appropriate self-regulation skills (n = 88). This code included responses related to students’ appropriate self-awareness, executive function, and/or learning/study strategy skills. It also included responses such as regular class attendance, being organized, engaging in help-seeking behavior, utilizing appropriate coping strategies, and using effective organization and time management strategies. The next most common code was receiving consistent support on campus (n = 60). This included individuals with ASD being connected with supports on campus in addition to the disability service office, receiving mentoring from faculty, staff, or peers, receiving appropriate advising, and participating in regular “check-ins.” The third most common code (n = 48) was individuals with ASD having appropriate self-determination skills, such as the ability to self-advocate, having appropriate self-efficacy, and being motivated and/or engaging in goal directed behaviors.

Table 3. Number of participants by qualitative coding for strengths/facilitators of successful college students with ASD (n = 145).

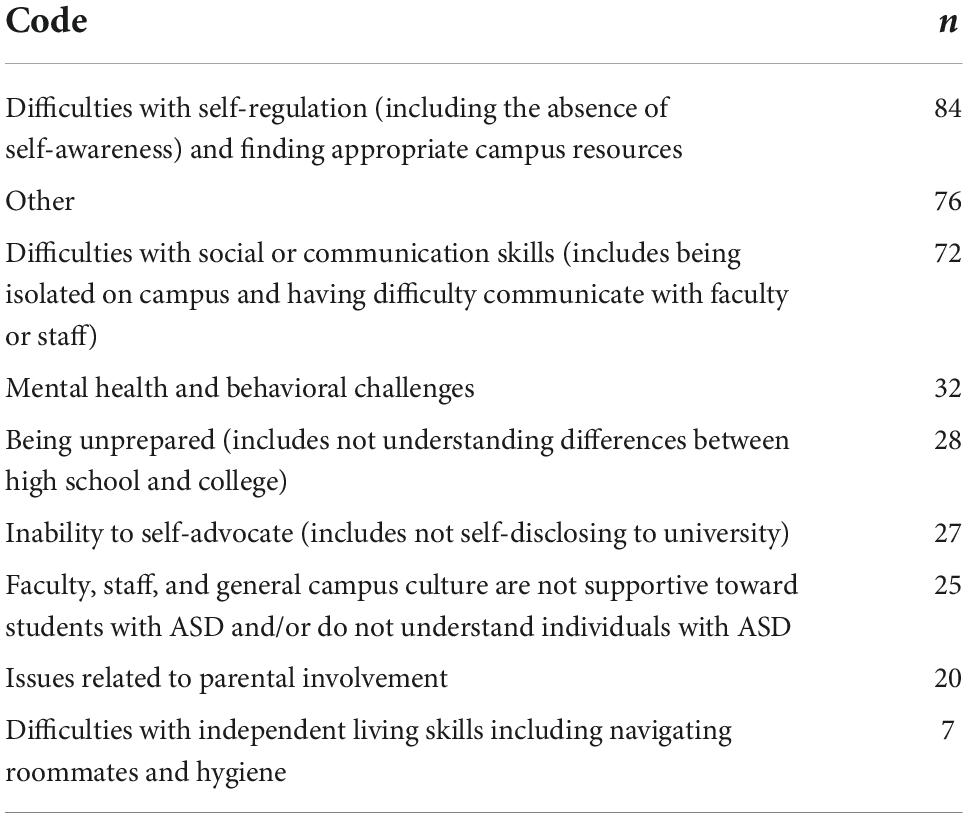

This research question also focused on the barriers to success for college students with ASD. Similar to the analysis for strengths and facilitators of success, respondents could provide up to three responses to an open-ended survey question that was utilized to answer this research question. At least one barrier was noted by 147 participants, with a total of 448 responses provided. All participant responses were classified into eight codes. It is important to note that some one word or anomalous responses (n = 99 responses from 76 participants) did not fit the coding schema, such as “constant changes,” “assumptions,” or “unfamiliar.” As described in Table 4, the most commonly perceived barrier to success for college students with ASD was difficulties with self-regulation (n = 84). This included failure to engage in appropriate time management, executive function, or learning/study strategies as well as not engaging in appropriate help seeking behavior (i.e., not seeking out campus resources). Difficulties with class attendance, cognitive flexibility, and failure to adapt to change were also reported. The next most commonly reported barrier was difficulties with social and/or communication skills (n = 72). Difficulties understanding social norms and communicating with professors were reported in addition to being lonely or socially isolated. The third most common barrier was the presence of mental health and/or behavior challenges (n = 32). Difficulties with anxiety, the inability to utilize appropriate coping mechanisms, and behavioral/emotional episodes were common responses.

Table 4. Number of participants by qualitative coding for the barriers to success for college students with ASD (n = 147).

A growing, but fairly limited, body of research about college students with ASD has developed over the past 20 years (Anderson et al., 2019). The findings of this present study align with the results of previous research in many ways. The college personnel in this study indicated variation in the academic preparation of college students with ASD varies, with equal numbers of participants indicating that college students with ASD are, and are not, academically prepared for college. This finding was also mirrored in their responses to the open-ended items concerning strengths/facilitators of success and barriers, as almost equal numbers of participants (n = 29 and n = 28, respectively) noted prior high school preparation as both a strength and the lack of preparation as a barrier. This finding may reflect that individuals with ASD vary in their academic, social, and general preparation for the college environment.

Participants reported that appropriate self-advocacy, independent living skills, and learning/study skills were important facilitators of success for college students with ASD, similar to the findings of White et al. (2016). Most of the strengths/facilitators of success noted by participants were also perceived as potential barriers (if the individual student did not have them). For example, having appropriate social skills was a common strength, but not having appropriate social skills was the second most noted barrier. Difficulties with social skills was also noted by Elias et al. (2019). Likewise, receiving/seeking appropriate support on campus was noted as a strength, but not engaging in help-seeking behavior was noted by those responding to the survey as a difficulty. Finally, having appropriate self-regulation skills was the most commonly reported strength, yet difficulties with self-regulation were also listed as the most common barrier.

As noted in previous studies conducted with heterogenous samples of students with disabilities (Gelbar et al., 2020), the respondents in this study indicated that having appropriate self-determination and self-advocacy skills was a major facilitator of success for college students with ASD. Conversely, they also believed that the absence of these skills served as a major barrier to success in college.

The respondents also indicated that many college students with ASD experience anxiety, depression, social isolation, and loneliness, which was also indicated by previous research (Gelbar et al., 2014). Only seven participants noted that independent living skills (including navigating roommates) was a barrier to the success of college students with ASD. This was an interesting finding, as previous research has suggested that this has been an important factor facilitating employment and other postsecondary success (Kanne et al., 2011).

One of the limitations of this type of research is that those who respond to the survey are reflecting on their perceptions of others’ experiences. Concerns have been raised about the validity of self-report information gathered from individuals with ASD due to their lack of insight (Schriber et al., 2014), so this study may provide an important dimension related to college readiness and completion of this group. Future research should, however, triangulate the findings from observers such as parents and disability service professional with data gathered directly from individuals with ASD. Another limitation of this research is that it required participants to generalize across a group of participants who have varied outcomes. Again, future research should address this concern by also gathering information from parents and individuals with ASD. It is also suggested that future research explore the predictive validity of the patterns reported in this data by gathering data on important predictors (e.g., self-determination, learning/study strategies, etc.) from individual students and, if possible, regressing it on important outcomes such as college retention, GPA, and graduation. Additionally, as participants in this study were unable to estimate the graduation rate for college students with ASD, efforts should be made to improve data collection and reporting on student outcomes, and eventually, longitudinal research should be conducted that specifically samples and reports on outcomes of college students with ASD. In addition, this study did not explore whether the perceptions for individuals with ASD would also apply to individuals without ASD. Without a comparison point, it is not possible to determine to what extent these trends apply to all college students vs. difference in the magnitude or presentation of these trends for individual with ASD. Future research should address this limitation by using students without ASD as a comparison (e.g., compared to all college students are college students with ASD more likely to experience high levels of depression.”

A specific set of reported facilitators of success for college students with ASD need to be developed by students before starting college if these students are going to successfully navigate and thrive in the college environment. In addition to academic preparation, students need to have the ability to self-advocate, make independent decisions, self-regulate their behaviors, use appropriate coping and study strategies. Further, the ability to communicate effectively with a variety of individuals (i.e., peers, staff, and faculty) is another essential path to success. It is important that high school (and even middle school) students with ASD be given the opportunity to develop these skills by receiving systematic instruction in these areas. Professionals who work with adolescents with ASD need to move beyond simply developing academic skills and to assist students in becoming more independent sooner to enable them to reach their potential as capable young adults with ASD.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Connecticut IRB. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

NG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and contributed to the study’s conception, design, data collection, and data analysis, read and approved the final manuscript.

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Grant Program (Grant No. S206A190023). Materials and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent the Department of Education’s position or policy.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anderson, A. H., Carter, M., and Stephenson, J. (2018). Perspectives of university students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 48, 651–665. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3257-3

Anderson, A. H., Stephenson, J., and Carter, M. (2017). A systematic literature review of the experiences and supports of students with autism spectrum disorder in post-secondary education. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 39, 33–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.04.002

Anderson, A. H., Stephenson, J., Carter, M., and Carlon, S. (2019). A systematic literature review of empirical research on postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 49, 1531–1558. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3840-2

Barnhill, G. P. (2016). Supporting students with Asperger Syndrome on college campuses: Current practices. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 31, 3–15. doi: 10.1177/1088357614523121

Dymond, S. K., Meadan, H., and Pickens, J. L. (2017). Postsecondary education and students with autism spectrum disorders: Experiences of parents and university personnel. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 29, 809–825. doi: 10.1007/s10882-017-9558-9

Elias, R., Muskett, A. E., and White, S. W. (2019). Educator perspectives on the postsecondary transition difficulties of students with autism. Autism 23, 260–264. doi: 10.1177/1362361317726246

Evans, N. J., Broido, E. M., Brown, K. R., and Wilke, A. K. (2017). Disability in higher education: A social justice approach. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Frost, K. M., Bailey, K. M., and Ingersoll, B. R. (2019). “I just want them to see me as…Me”: Identity, community, and disclosure practices among college students on the autism spectrum. Autism Adulthood 1, 268–275. doi: 10.1089/aut.2018.0057

Gelbar, N. W., Madaus, J. W., Dukes, L. L., Faggella-Luby, M., Volk, D. T., and Monahan, J. (2020). Self-determination and college students with disabilities: Research trends and construct measurement. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 57, 163–181. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2019.1631835

Gelbar, N. W., Smith, I., and Reichow, B. (2014). Systematic review of articles describing experience and supports of individuals with Autism enrolled in college and university programs. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 44, 2593–2601. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2135-5

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Brooks, P. J., Someki, F., Obeid, R., Shane-Simpson, C., Kapp, S. K., et al. (2015). Changing college students’ conceptions of autism: An online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 45, 2553–2566. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2422-9

Glennon, T. J. (2016). Survey of college personnel: Preparedness to serve students with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 70, 1–6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.017921

Grbich, C. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. London: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781529799606

Kanne, S. M., Gerber, A. J., Quirmbach, L. M., Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., and Saulnier, C. A. (2011). The role of adaptive behavior in autism spectrum disorders: Implications for functional outcome. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 41, 1007–1018. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1126-4

Knott, F., and Taylor, A. (2014). Life at university with Asperger Syndrome: A comparison of student and staff perspectives. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 18, 411–426. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.781236

Kuder, S. J., and Accardo, A. (2018). What works for college students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 48, 722–731. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3434-4

Lalor, A. R., Madaus, J. W., and Newman, L. S. (2020). Leveraging campus collaboration to better serve all students with disabilities (Practice Brief). J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 33, 249–255.

Lombardi, A., Murray, C., and Dallas, B. (2013). University faculty attitudes toward disability and inclusive instruction: Comparing two institutions. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 26, 221–232.

Scheef, A. R., McKnight, M., and Gwartney, L. (2019). Supports and resources valued by autistic students enrolled in postsecondary education. Autism Adulthood 1, 219–225. doi: 10.1089/aut.2019.0010

Schriber, R. A., Robins, R. W., and Solomon, M. (2014). Personality and self-insight in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106, 112–130. doi: 10.1037/a0034950

Tipton, L. A., and Blacher, J. (2014). Brief report: Autism awareness: Views from a campus community. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 44, 477–483. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1893-9

Viezel, K. D., Williams, E., and Dotson, W. H. (2020). College-based support programs for students with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 35, 234–245. doi: 10.1177/1088357620954369

Keywords: college students, autism, college personnel, postsecondary education, autism spectrum disorder

Citation: Gelbar N, Cascio A, Madaus J and Reis S (2022) Accessibility service providers’ perceptions of college students with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Educ. 7:994527. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.994527

Received: 14 July 2022; Accepted: 14 September 2022;

Published: 06 October 2022.

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Robert Weis, Denison University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Gelbar, Cascio, Madaus and Reis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicholas Gelbar, bmljaG9sYXMuZ2VsYmFyQHVjb25uLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.