95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 28 November 2022

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.987420

This article is part of the Research Topic Jazz and Improvisation in Education: Towards Gender Diversity and Equity View all 6 articles

Nicole Canham1*

Nicole Canham1* Talisha Goh1

Talisha Goh1 Margaret S. Barrett1

Margaret S. Barrett1 Cat Hope1

Cat Hope1 Louise Devenish1

Louise Devenish1 Miranda Park1

Miranda Park1 Robert L. Burke1

Robert L. Burke1 Clare A. Hall2

Clare A. Hall2There is growing interest in examining the gendered nature of music practices worldwide. Recent investigations of access to and equity in the music industry have included studies of gender discrimination in classical music, popular music, film music, and within the structure of colonization. This article contributes to this work by reporting the findings of a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) of research that addresses the gendered nature of jazz and improvised music practices in education settings, ensembles, and professional performance environments. Our purpose was to generate an understanding of the phenomenon of gendered jazz and improvised music practices through the following research questions: (1) what is the scope and focus of existing empirical research on gender in jazz and improvised music? (2) where has this research been undertaken, by whom, and to what purpose? (3) what methodological approaches have been employed? (4) how has gender been understood in this research? Findings indicate that research on gender in the jazz and improvisation sector is largely undertaken by women researchers working individually within the Euro-Anglosphere (US, UK, Australia). The majority of studies were undertaken in the qualitative paradigm with autoethnographies, case studies, ethnography, and narrative inquiry as the dominant research approaches. A small number of studies used quantitative or mixed methods with gender as the key variable. By contrast, qualitative studies focused on gendered accounts of working in the jazz and improvisation sector providing deeply personal narratives via artistic research, as illustrations of how larger institutional and societal factors shape the experiences of the individual. Given this personal focus, explicit referencing to theoretical frameworks was de-emphasized in the papers reviewed. Our discussion focuses on the individual and institutional factors that might account for these patterns of research and knowledge production as a way of framing past and present understandings of issues relating to gender in jazz and improvised music. We argue that small-scale qualitative research needs to be supported by larger-scale intersectional investigation into systemic or institutionalized phenomena that investigates how gender marginalization is enabled through these structures. Recommendations for further research, policy and practice are provided.

There is growing interest in examining the gendered nature of music practices worldwide. Equity and access in the music industry has recently been explored via investigations of gender discrimination in classical music (Scharff, 2016), popular music (Strong and Raine, 2019), film music (Wilcox, 2021), and within the structure of colonization (Tan, 2021). This article contributes to this work by examining the range of literature that addresses the gendered nature of jazz and improvised music practices. An understanding of gender in jazz practice will assist educators, curators, and performers when they are making decisions regarding gender balance in programs and projects. A gender diverse learning environment or workforce can lead to many benefits, including increased productivity and satisfaction (Clark et al., 2021). It also enables other women to see themselves in roles within jazz, making them more likely to consider it as a career path (Bird and Rhoton, 2021).

Jazz and improvisation is a global industry that encompasses composition, improvisation, performance, recording, and education (Dibley and Gayo, 2018; Onsman and Burke, 2018). Historically, jazz and improvisation have been framed using what Tucker (2002) describes as “predictable riffs” (p. 375) that can be interpreted as commentaries on a range of issues including “progress, modernism, primitivism, individualism, American exceptionalism, [and] essentialist notions of race and gender” (ibid.). Though the historic global roots of jazz and improvisation have origins in resistance to oppression and social activism (Heble, 2000), many aspects of contemporary jazz and improvisation practices are described as socially divisive and elitist (Gill, 2002; Banks and Milestone, 2011; Miller, 2016). While we recognize that this complex mix of factors collectively shape many aspects of how jazz and improvisation can be experienced, understood and interpreted (particularly race), in this article our focus is on gender.

Historic and contemporary jazz and improvisation practices are described as perpetuating the exclusion of female-identifying and gender non-conforming (FI and GNC) artists (Heble and Siddall, 2000; Hope, 2017). Despite growing industry awareness and initiatives to support FI and GNC artists' advancement, these initiatives have made little sustainable change to the industry's gender profile. FI and GNC artists are still disadvantaged in terms of income, inclusion, and professional opportunities (Devenish et al., 2020). International research indicates that women have historical challenges in career development in jazz and improvisation as a result of these gendered perceptions and constraints (Kirschbaum, 2007). A report from the UK (Shriver, 2018) revealed that only 5% of jazz and improvisation instrumentalists (not including vocalists) were women. This indicates that the measures taken to date to address persistent barriers to equality in music have been inadequate. The concerns outlined above are echoed globally across all musics, and in 2019 an international consortium of major music festivals, foundations, broadcasters and institutions was formed to address the issue. Known as The Keychange Pledge, this project aims to “transform(s) the future of music whilst encouraging festivals and music organizations to achieve a 50:50 gender balance by 2022” (PRS Foundation, 2022).

As part of the first phase of a 3-year research project funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC), we undertook a systematic literature review (SLR) of research investigating gender and gendered experiences in jazz and improvised music. SLRs have become important tools, particularly in medicine and health care (Moher et al., 2009), as they provide a means to identify, evaluate and synthesize relevant research that has been undertaken in pursuit of a specific question. An SLR is strictly driven by a pre-determined protocol, which outlines the way in which a search of the existing literature is to be conducted (Moher et al., 2009). In addition to specific search criteria, transparency of the inclusion and exclusion process, and multiple reviewers (to limit bias), SLRs also address explicit research questions. This approach provides a framework for SLRs to offer a “cumulative” (Evans and Benefield, 2001, p. 527) picture of existing data with many applications. For these reasons, SLRs have become increasingly common in fields beyond the sciences, including engineering (Torres-Carrión et al., 2018), education (Vanassche and Kelchtermans, 2015), and the arts (e.g., Young et al., 2016; Creech et al., 2020; Barrett et al., 2021) as the need for evidence of what works, or what is already known, can be useful for “informing policy makers and practitioners” (Evans and Benefield, 2001, p. 529) and also for shaping the direction of future research (Torres-Carrión et al., 2018). Given the complex and extensive nature of the challenges outlined in the background above, we adopted the SLR methodology in order to explore the following questions:

1. What is the scope and focus of existing empirical research on gender in jazz and improvised music?

2. Where has this research been undertaken, by whom, and to what purpose?

3. What methodological approaches have been employed?

4. How has gender been understood in this research?

We drew upon the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) Statement and PRISMA Checklist as outlined by Liberati et al. (2009) in this review. As per their recommendations, we outline below the parameters of our SLR, and the results of our systematic searches including criteria for inclusion or exclusion. Our search was also guided by Cooke et al. (2012) SPIDER systematic search tool (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type). Cooke et al. (2012) developed the SPIDER tool after observing that PICO (Population/problem, Intervention/exposure, Comparison, and Outcome), the most common search tool used in SLRs, was ideal for quantitative studies but less effective for the analysis of qualitative and mixed methods research. The SPIDER tool is an adaptation of the PICO parameters developed by Cooke et al. that makes room for some of the distinguishing features of qualitative research, including smaller sample sizes, findings that are not always generalizable, and outcomes that may be “unobservable” or “subjective constructs” (Cooke et al., 2012, p. 1437).

Moher et al. (2009) observe the iterative nature of the SLR process, and as we developed our search protocol some refinement was needed. We conducted a series of preliminary searches through a university library search engine, Google Scholar, and the JSTOR, Web of Science, EbscoHost, and ProQuest databases to refine our search terms and establish an appropriate starting date. Our preliminary searches yielded thousands of results and many unrelated papers, largely due to our use of “gender” and “improv*” as search terms which returned a high volume of medical-related papers. Searches of jazz AND gender, and improvisation AND gender similarly yielded thousands of results. (Jazz OR improv*) AND (women OR gender) led to a reduction in results before we settled on the following:

(Jazz OR improvisation) AND (women OR gender)

We similarly found that the time frame also significantly influenced our results. While we initially explored a starting date of 1980 (given that the early 1980s was a turning point for research on women's participation in the Australian arts sector through the Women in the Arts project (Appleton, 1982) search results numbers were unwieldy. We also tested a starting date of 2000, for practical and scholarly reasons. Moreover, the year 2000 marks a time when academic publications were more widely available online, and given that Sherrie Tucker's seminal journal article, “Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies,” appeared in 2002 this seemed an appropriate starting point.

Our first search and screening comprised a search of databases, three of which enabled us to access collections with a strong arts and humanities focus: JSTOR, Web of Science (all databases), Ebscohost—RILM and Music Index, and ProQuest Central. Criteria for inclusion at the initial screening phase was as follows:

• Published after 1 January, 2000—February, 2022

• English language

• Full-text

• Peer reviewed

Using the criteria above, we received a total of 495 results.

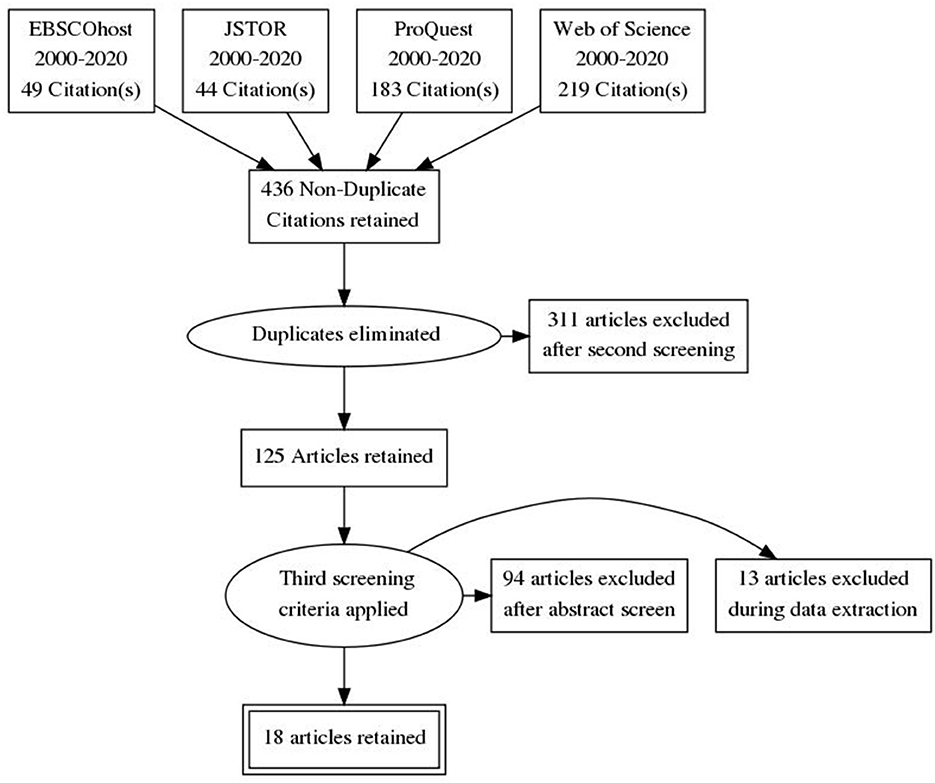

The second screening had two phases: the elimination of duplicates and screening of titles. We first (Author 1 and Author 2) imported the initial search results into Endnote and eliminated duplicates using Endnote's duplicate removal function, followed by a further check and manual removal of any remaining duplicates (59 items, leaving a total of 436 papers). Titles were then screened by the same team of two and a further 311 papers were excluded because they did not explore our areas of focus or were not primarily research-focused (for example, a number of papers related to a novel with the word jazz in the title but the focus was literary studies, not jazz and improvisation). It was at this stage that we also introduced elements of SPIDER into our search, in particular, the Phenomenon under Investigation. Criteria for inclusion at this stage:

• Paper title reflected connection to the discipline of music or work (where necessary the team viewed the abstract for clarification)

A spreadsheet with abstracts and screen 2 criteria notes for the remaining 125 papers was generated to inform the third screening.

The full list of 125 papers (titles and abstracts and screen 2 criteria notes) were reviewed individually by three researchers (Authors 1, 2, and 3) against the criteria outlined above prior to meeting for discussion. As recommended by McDonagh et al. (2013) the additional researcher who contributed to the third screening was a senior research member of our team. After considering the research type (as per SPIDER) the papers retained after the third phase met the following criteria:

• Only papers based on empirical research were retained (where necessary the team viewed the abstract for clarification)

• Only research fitting the reference period was retained (where necessary the team viewed the abstract for clarification)

• Connection to research focus: gender and involvement of jazz and improvised music

• Focus on active work in jazz and improvised music

• All researchers had to agree about inclusion or exclusion of papers at this stage.

The 18 retained papers were then analyzed by the full research team against the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type) search tool in full (Cooke et al., 2012). Each paper was assigned to two readers, who both closely read the paper and collated the information relevant to the SPIDER search parameters in a spreadsheet. The full research team then met to discuss this final search stage and to analyze the results.

In this section, we explore the results of our SLR, beginning with the PRISMA flow diagram of the screening process.

Figure 1 below is a flowchart of the screening process.

Figure 1. Screening process flowchart. Figure created with PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator by Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaboration (http://prisma.thetacollaborative.ca/).

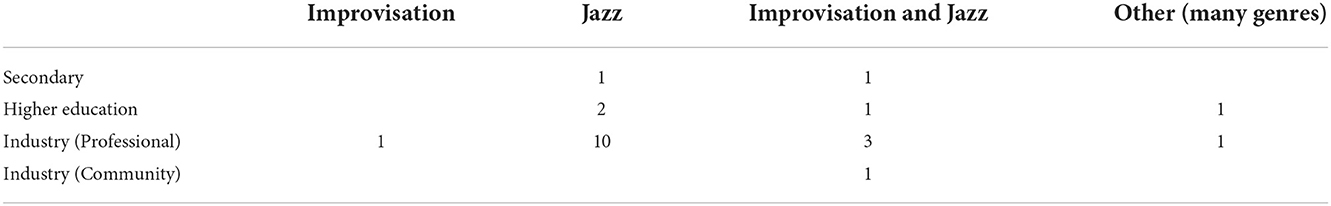

Once the screening process and SPIDER analysis was complete, we compiled a table summarizing the research setting and focus of the 18 retained papers in order to address research question (1) what is the scope and focus of existing empirical research on gender in jazz and improvised music?

Table 1 above, provides insights into the range of research settings in which the research was undertaken and the musical focus (jazz and/or improvisation). Overall, there were significantly more papers with a focus on jazz than improvisation. Thirteen papers explicitly looked at jazz, while only 2 were explicitly concerned with improvised music. Papers explored gendered experiences of involvement in jazz and improvised music in a range of settings, including secondary and tertiary education, and industry environments. A further three papers featured multiple settings, but, in the main, the research focus was on industry professionals (15 papers in total).

Table 1. Research setting and musical scope (3 papers had multiple settings have been included more than once in this table).

We then expanded our analysis to highlight further details of the publications in order to answer research question (2) “where has this research been undertaken, by whom, and to what purpose?” Tables 2, 3 above provide a summary of the key aspects of the retained papers relevant to question (2). There was a reasonable geographic spread in the papers; concomitantly it is worth noting the strong concentration of papers from the Global North and limited papers from the Global South (Asia and Latin America) which may be due to the English language only criteria for inclusion.

We also collated the gender of the authors to look for patterns, and found that there were almost twice as many female authors as male authors.

We then examined the different research designs and methods employed in the papers (Table 4), as part of addressing research question (3) “what methodological approaches have been employed?” Qualitative studies outnumbered quantitative studies, with a strong emphasis on interview and historical qualitative data analysis.

As recommended by Joanna Briggs Institute (2017), we then examined the papers for their methodological congruity as part of assessing the quality of the retained papers. Papers were checked against nine criteria in this phase, outlined in Table 5 below. Through this critical appraisal we observed inconsistencies and limitations in research design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, researcher positioning, and bias.

This analysis revealed that two-thirds of the papers provided clear links between the philosophical perspective being taken and the research design. Choice of research methodology in relation to the research question/s was clearly in alignment in half of the 18 papers analyzed, whilst in the remaining papers, there was no clear research question stated. Similarly, looking at the methods of data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, 13 papers directly addressed these aspects of their research design but in the remaining papers, these aspects were most often unclear or not applicable. There was a strong commitment overall to the participant voice coming through in the research, with 15 of the 18 papers making this a clear focus. However, we noted that despite the majority of papers being situated in the qualitative paradigm, researcher acknowledgment of the foundational concepts of researcher positionality and bias and their connection with credibility and trustworthiness (e.g., Flyvbjerg, 2011) was understated or the connections were not made. The limitations relating to the clear establishment of the credibility and trustworthiness of the papers analyzed extended beyond other issues relating to researcher transparency such as positionality and bias (e.g., Allen, 1994) into ethics, and none of the papers included a clear and detailed ethical statement. While for some papers ethical clearance was not applicable, there were many others where (given the research design adopted), an ethical statement would have been appropriate.

In further interrogation of methodological approaches, settings and researchers in relation to research question (3), we also conducted a sub-analysis by author.

In this sub-analysis we grouped papers according to author, including: author gender; research paradigm; research methods; and, participants. The sub-analysis, outlined in Table 6, revealed that of the 18 papers, 14 were sole-authored, and 12 of these had female authors. Author gender identity was determined through a cross-check of pronouns used in the author's institutional profile. Of these 12 papers, 8 employed a qualitative research design, with a preference for in-depth interviews, and a small number of participants. Three of the 8 qualitative papers were autoethnographic studies. Two sole-authored papers were written by males, one exploring female perspectives, and the other a male perspective. Of the remaining 4 co-authored papers, 3 had two authors (1 male, 1 female × 2, 2 male × 1), and one had multiple (10) authors. The co-authored papers included two mixed methods studies and two qualitative studies. Looking in finer detail at the retained papers, we noted that the research presented in just three of the papers appear to have been supported by specific funding, and at least 7 of the authors have had their papers published while they were still doctoral candidates, or were early career researchers.

Finally, to address research question (4) how has gender been understood in this research?, we compiled a table bringing together the stated theoretical frameworks authors drew upon, together with the approach to gender in each paper. Table 7 below lists the understandings of gender and disciplinary or theoretical position underpinning the 18 retained papers.

Analyzing Table 7, it is evident that a multitude of theoretical ideas has informed the research undertaken. Gender was similarly framed in multiple ways, with authors referring to performative, experiential, and identity-based views of gender, in addition to research that explored gender as a variable.

Areas of risk and bias in this SLR included study selection and researcher bias. To mitigate the risk of bias, we took the following steps as recommended by McDonagh et al. (2013) by clearly stating the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were rigorously applied at all stages. McDonagh et al. (2013) also recommend the process of dual review, that is “having two reviewers independently assess citations for inclusion” (p. 16) as a further step in reducing the risk of bias. In our case, all stages of the SLR process were undertaken by multiple members of the research team, with the final selection stage involving three members of the research team, one of whom is a senior researcher. Analysis of papers was undertaken by the full team of eight researchers.

In the discussion which follows, we return to our four central research questions as we explore the implications of our findings.

(1) what is the scope and focus of existing empirical research on gender in jazz and improvised music? (2) where has this research been undertaken, by whom, and to what purpose? (3) what methodological approaches have been employed? (4) How has gender been understood in this research?

The scope of the research was reflected in the choice of research settings. Observation of participants in natural settings (Clancey, 2006) is an appropriate choice for qualitative research design, but the wide range of theoretical and analytical approaches taken with the data gives the impression of many possibilities and problems. Similarly, the lack of clarity around researcher positionality and bias identified in our analysis tended to limit the degree to which alternative angles of the situation came across (Allen, 1994; Flyvbjerg, 2011). In the case of the autoethnographic studies (4 papers) this is perhaps understandable, but in the remaining papers it is unclear why well-established qualitative research methods relating to transparency were not fully followed.

The musical focus in the retained papers reflected a more concentrated focus on jazz (13 papers), with only 2 papers focused on improvised music. The remaining papers had a combined jazz/improvisation focus.

There was a clear geographical focus to the research reviewed, with papers largely coming from North America and Europe, reflecting a strong Northern hemisphere focus, followed by a small number of papers from Australia and sole papers from South Africa and the Global South. This finding reflects the dominance of US/European scholarship in this area, as much as it also reflects the limitations of the language parameters of our search, and highlights a northern/southern hemisphere divide. Perspectives of issues around gender in jazz and improvised music reflected here offer a developed western world view of the problem.

Twelve of the 14 sole-authored papers were written by women and there was a predominance of qualitative, in-depth interviews among these papers. In terms of co-authored papers, women authors were involved in 3 of the 4 co-authored papers, and in 2 of these papers, the woman was the lead author. Of the 11 authors who were men, 9 worked on co-authored papers, with 2 as lead authors, and 2 as sole authors.

Looking across the breakdown of authorship and the distribution of funding, much of the work being done in this area appears to be by researchers who are women, lacking in institutional support for research in this area. Of the three papers where funding was clearly acknowledged, all were co-authored, and two of the papers were led by women. It is possible, therefore, that a lack of research funding in this area is shaping efforts, especially the research methods, and consequently what is being published. Examining papers with significant funding, only 1 paper fits into this category (Welch et al., 2008), and it featured a team of 10 authors, led by a man.

The scope and scale of the retained papers was therefore greatly varied, which has implications for how gendered experiences in jazz and improvised music have been investigated, as well as how they are currently understood. Similarly, analysis of the people undertaking this research reveals strong contributions from practitioners, not just academics, and practitioner/early career academics. Examining the career stages of the authors at the time of publication (where it was declared) it becomes clear that six of the papers arose from authors' doctoral dissertations or work as early career researchers. The bulk of the responsibility for investigating and articulating what is a widespread and intractable workplace occurrence (problem) therefore seems to be largely taken up by lone women practitioner/researcher-pioneers with limited resources.

The conditions outlined above may have influenced the overwhelming preference for qualitative research methods (13 papers), and the framing of research in narrative and storytelling terms (9 papers). These papers used methods of ethnography or autoethnography (Williams, 2005; MacDonald and Wilson, 2006; Suzuki, 2013; Istvandity, 2016; Jovicevic, 2021), and interview or case studies (Metzelaar, 2004; Welch et al., 2008; Suzuki, 2013; Hannaford, 2017). Additionally, a number of papers were based on analysis of secondary interview or archival data (Willis, 2008; Caudwell, 2012; Denson, 2014; Wahl and Ellingson, 2018). While these methods limit the generalizability of findings, this bank of qualitative accounts can serve as templates for how others might interpret their own experiences.

Three main approaches toward gender guided the papers found in this review: gender as experience, gender as performance, and gender as a variable. Some papers were coded in more than one category as they approached gender in multiple ways.

The 13 papers coded within this category focused upon gendered experiences, adopting theoretical frameworks from multiple disciplines such as leisure or expertise studies (Welch et al., 2008; Caudwell, 2012), theories of identity and hegemony (MacDonald and Wilson, 2006; Denson, 2014; Istvandity, 2016; Hannaford, 2017; Wahl and Ellingson, 2018), organizational studies (Metzelaar, 2004), and intersectionality (Williams, 2005; Vargas, 2008; Willis, 2008; Suzuki, 2013; Jovicevic, 2021). Sociological and phenomenological understandings underpinned the theoretical frameworks used in these papers, positioning gender as an identity or experience within a wider socio-cultural framework. All but one were focussed upon women as subjects, with a single paper addressing experiences and expressions of male blackness through jazz (Vargas, 2008). Using these qualitative interdisciplinary approaches, this literature supported the notions that marginalized experiences and identities are perpetuated throughout hegemonic structures within the musical discourse, industry, and organizational structures, and reinforced throughout broader societies and cultures. Focussing upon the exclusion or discrimination of gender diverse or minority participants, these papers highlighted how participants have navigated and negotiated such structures in the past and present. Acknowledging intersecting factors of race, class, religion, age, and nationality, this literature emphasizes “testimonies as a subjective point of view” (Jovicevic, 2021, p. 149) for the mechanisms of discrimination that can be observed throughout jazz and improvisation.

Seven papers focussed on gender through a performance lens (Butler, 2006). Due to the nature of gender performativity, which draws upon and is reinforced by identity and experience, most of these also covered aspects of gendered experience and identity discussed above (Metzelaar, 2004; Williams, 2005; Willis, 2008; Caudwell, 2012; Istvandity, 2016; Hannaford, 2017; Jovicevic, 2021). Only one paper was concerned with gender performance without a similar emphasis on gendered experience, instead discussing culturally gendered dialogues in a collaboration between music and Brazilian dance (Browning, 2007). These papers tended to explore the physical, temporal, or artistic space occupied by women in music; with authors discussing how gendered experiences and cultural notions tend to manifest through medium of expression (such as genre or instrument choice) (Metzelaar, 2004; Williams, 2005; Willis, 2008; Istvandity, 2016; Jovicevic, 2021), or the musical performance itself (Williams, 2005; Browning, 2007; Willis, 2008; Caudwell, 2012; Istvandity, 2016; Hannaford, 2017). Many of these papers could thus be considered examples of feminist aesthetics, employing poststructural or postmodern lenses to analyse interviews (Metzelaar, 2004; Browning, 2007; Caudwell, 2012; Hannaford, 2017), autoethnographic accounts (Williams, 2005; Istvandity, 2016; Jovicevic, 2021), or secondary data (Willis, 2008). Like the research discussed above which focussed upon gendered experiences, the individual responses presented in these accounts were offered as examples of individual negotiation between oppressed groups and larger structural forces.

A smaller number of papers (6) framed gender as a variable or means of comparison between study participants. These tended to be larger-scale or quantitative analyses, with a greater proportion of papers in this category having multiple authors (McKeage, 2004; Wehr-Flowers, 2006; Welch et al., 2008; Picaud, 2016; Wahl and Ellingson, 2018; McAndrew and Widdop, 2021). Frameworks employed came from cultural studies (Welch et al., 2008; Picaud, 2016; Wahl and Ellingson, 2018; McAndrew and Widdop, 2021), education (McKeage, 2004; Wehr-Flowers, 2006; Welch et al., 2008), and psychology (Wehr-Flowers, 2006). Although these studies were able to address gendered phenomena on a larger scale, analyses were less nuanced than those framing gender as an experience, identity, or performance. Only one of these papers examined intersectional factors in any depth (Picaud, 2016), with the rest instead focussing on instrument played, musical genre, or musical activity (such as playing in a high school ensemble or industry setting) (McKeage, 2004; Wehr-Flowers, 2006; Welch et al., 2008; Wahl and Ellingson, 2018; McAndrew and Widdop, 2021).

While there was no consensus about how best to approach research into gendered experiences of jazz and improvised music in the 18 papers we reviewed, there were some clear themes that emerged through their findings. Women in jazz and improvised music face differing obstacles to success than men, as they must navigate both a historically male-dominated meritocratic approach to inclusion, together with their own exclusion and marginalization due to their gender (Suzuki, 2013). These challenges were framed and described as both systemic and individual issues in the papers reviewed (e.g., Willis, 2008).

Findings highlighted ways in which the “meritocratic” belief system of jazz is often used to justify or obscure gender hierarchies and discrimination (MacDonald and Wilson, 2006). From the point of view of navigating jazz and improvised music teaching, learning and work environments, discrimination is experienced in a wide range of ways not only in relation to gender, but also to instrument (Istvandity, 2016). Gender makes a difference to what a person brings to an ensemble (Browning, 2007), and gendered experiences are often reinforced by binaries relating to a person's instrument (Istvandity, 2016; Wahl and Ellingson, 2018), which are in turn applied as ways of assessing a musician's legitimacy (McAndrew and Widdop, 2021).

Gender has been found to have a significant effect on participation and attrition in jazz in the transitions from high school, to college and then into the profession (McKeage, 2004; Welch et al., 2008). Lived experiences of discrimination influence individual improvisational practices (Hannaford, 2017), musician identity (MacDonald and Wilson, 2006; Wehr-Flowers, 2006) and contribute to experiences of marginalization (Williams, 2005). Low representation of women artists (10%) was also observed in Picaud's (2016) analysis of programming in the Parisian jazz scene which is reflective of broader tendencies toward a focus on genre, nationality and race as reflections of diversity in jazz, rather than gender (see also Suzuki, 2013).

Gender and concepts of masculinity in particular have shaped jazz and improvised music-making environments that can be off-putting or excluding for women (Wehr-Flowers, 2006; Caudwell, 2012; Denson, 2014) reinforcing the view that jazz and improvised music is both male-defined and male-dominated (Jovicevic, 2021). McAndrew and Widdop (2021) draw attention to the combined impact of these factors in contributing to women's low engagement with jazz, significantly lower recording outputs and consistent disadvantage due to their gender. Different approaches to socializing, barriers to acquiring formal education, limited access to networks and gatekeeping, gendering of instruments, canonization of male musicians and caregiving responsibilities all highlight the intersectional nature of the challenges identified, which result in sustained perceptions of women artists' lack of legitimacy and promulgate an “internally elitist” community (McAndrew and Widdop, 2021, p. 691). They concluded that further research into the function of gender inequalities within genres is required to “debias jazz in the interests of musicians, audiences and the music itself” (McAndrew and Widdop, 2021, p. 712). Navigating this environment requires double negotiation for women, who must not only master their instrument and the form, but also negotiate the experience of marginalization within a male-dominated community (Suzuki, 2013) that is driven by an idea of legitimacy that is dependent upon being male.

A limited range of solutions to these challenges were proposed, the most common solutions being those led by, initiated by, or designed for women only (Metzelaar, 2004; Denson, 2014). Acquiescence to existing hierarchies was presented as one possible solution. For example, Wahl and Ellingson (2018) found that successful women in the jazz scene have conformed to and capitalized on gender-exclusive and inclusive (e.g., vocalists) cultures. For others, the role of gender was down-played in participant accounts of work-related experiences (Suzuki, 2013) in favor of nationality or race. Recommendations were also made regarding changes at the education level (Metzelaar, 2004; Welch et al., 2008) and to leadership in the form of more female role models.

In sum, the findings highlight the multifaceted nature of gendered experiences of involvement in jazz and improvised music, which have personal, professional and educational consequences. Endemic notions of merit and diversity appear to be blind to gender in preference to genre, race, and nationality, inadvertently perpetuating the idea that jazz and improvised music environments are more equitable and open to all than they actually are. Issues around the relationship between the idea of legitimacy and gender raised by McAndrew and Widdop (2021), however, drawn attention to the differences between “the inherent nature of improvisation” (p. 691) and gendered approaches to “improvisational practice” (ibid.). The ideals of jazz and of improvisation would appear to be more progressive on paper than they are in practice.

While the research findings clearly indicate that depending on one's gender, the experience of involvement in jazz and improvised music is likely to be markedly different, what is missing is consensus on the nature of the challenge. The literature reviewed here reinforces the idea that there is a problem, but does not yet explore the ways in which the problem might be called out, addressed, or rectified on a level of scale beyond the individual, festival or organization. This may be because the “workplace” in jazz and improvised music is constantly shifting or hard to define, or that many music environments are unregulated and informal workspaces (McSharry et al., 2015). However, in order for initiatives such as the Keychange Pledge to be effective, greater understanding of how to negotiate attitudinal and behavioral shifts in unregulated workspaces will be key. While some of the research gives a strong grass-roots, on-the-ground picture of the experiences of those working in jazz and improvised music, the predominantly individual accounts that emerge through this SLR when viewed on their own may perhaps fail to reflect what is evident when the findings are viewed collectively. Gendered experiences of disadvantage in jazz and improvisation highlight endemic problems of gender discrimination at all of the various levels examined, and these appear to have been systemically sidestepped, ignored and/or perpetuated through ideals of meritocracy and legitimacy with deeply masculine foundations. Rather than viewing the problem one researcher at a time, the collective findings from this SLR highlight the need to take an ecological view of the problem if it is to be meaningfully addressed.

What is needed now are stronger connections to existing research conversations and the work of others in the field. This SLR highlights existing research findings relating to a range of challenges, possibilities, and problems, through each of the papers, but also reveals a lack of connection between authors, experiences and findings when viewed as a body of knowledge. Taking the aerial view offered by the SLR, we find that the research might explore how people live with the problem or have managed it on their own, but this is not the same as overcoming it at an institutional or sector-wide level.

While the research reviewed offered insights into gendered experiences of jazz and improvised music, findings that might enable challenges to be addressed on a larger scale were somewhat limited. We note that a “systematic review is essentially an analysis of the available literature (that is, evidence) and a judgment of the effectiveness or otherwise of a practice, involving a series of complex steps” (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017, p. 2). In our case, the search terms adopted for this SLR yielded research limited in quantity, varied in its quality, and, while the literature reviewed provides some nuanced individual experiences of gender in jazz and improvised music settings, there remain significant gaps in our understanding. Looking at the findings of the 18 retained papers, overall we note there are no solutions here—rather what our SLR revealed is that we still appear to be mapping the territory: one researcher at a time.

One observation looking across the different papers is that while gender appears to be understood and framed in different ways the overall picture of learning and work experiences appears to be one of wide-ranging discrimination. The nuanced experiences reported, highlight how multifaceted, and commonplace discrimination is (extending beyond gender to choice of instrument, for example), just as the beliefs and values described illustrate the many ways discriminatory practices are sustained.

A way to approach the expanded research agenda we recommend is to look sideways, and beyond the present jazz and improvised music discourses in order to develop more structured, cohesive, and better-supported research. Looking to inroads being made in science (for example, the Athena SWAN program), the visual arts (e.g., the Know my Name initiative of the National Gallery of Australia), and theater, film and television (Screen Australia's Gender Matters Taskforce) may provide alternative ideas for research design, sector initiatives and possible outcomes.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of the subject, which spans studies of both music and gender, and extends to such broad areas as ethnomusicology, cultural histories, music analysis, and educational psychology, there were varied understandings of gender across all papers. However, although the research addressed how gender contributes to marginalization in jazz and improvisation, less explicit attention was paid to what precisely these understandings of gender are, what they mean, and how they impact the research. Conceptions of gender were largely implied throughout the papers, and overwhelmingly presented as a binary, potentially overlooking a key area of discussion in the quest to highlight discrimination. Explicating and problematizing the complexity of gender understandings, as well as its implications in the context of jazz and improvisation, may be a fruitful area of future exploration in this area. In this vein, looking to intersectional frameworks such as feminist studies, queer studies and phenomenologies, and explorations of race and power, will add further depth to the conversation (Collins, 2002; Ahmed, 2006; Butler, 2006; Tucker, 2008).

Similarly expanding the scope beyond the experiences of the individual in jazz and improvised music, as valuable as this is, is also needed. We noted that on the whole, the research reviewed was largely unfunded work, undertaken by pioneering early career women researchers working alone, who may have formed a research agenda upon their own experiences of gender marginalization. This may help explain the limitations to the discussions of gender complexity noted above. Attempting to understand and address what appears to be a widely experienced issue one artist or researcher at a time is unlikely to bring about the breadth or depth of change required. To that end, further problematization of the workplace, and indeed greater attempts to understand and define the many and varied spaces that constitute the workplace for practicing arts in jazz and improvised music, are urgently needed. Understanding gendered experiences as workplace, not just personal narratives, opens up much-needed new directions in the research discourse around the impact of widespread and systemic workplace discrimination in jazz and improvised music. While awareness of racial discrimination has been a feature in the jazz discourse for some time (Borgo, 2002; Lewis, 2016), attempting to bring a united gender-based agenda into research and/or practice in this area raises questions as to how gender is understood, and which theoretical frameworks most effectively illuminate the challenges, which in turn reflect what we understand the challenges to be. Gender and workplace discrimination, for example, are legislated areas where policy, research, and practice are well-documented. It may be that expanding the research scope and focus into the area of workplace discrimination may help define a new research agenda that contributes to fostering more inclusive and diverse jazz and improvised music scenes.

As a review system designed for quantitative research, we acknowledge that the SLR format is not necessarily well-suited to the arts and humanities. However, SLRs have been successfully adapted to qualitative research to provide an overview of themes and trends in the field (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017). Evans and Benefield (2001) suggest that social research design is not always evaluative in the same way that medical research might be: “Thus, the questions addressed [are] not so much “What works?” but “How does it feel?” (p. 528), and this certainly appears to accord with the scope of our findings in this SLR. While understanding individual experience is both valuable and important, we are perhaps missing a thread in the discourse that is dedicated to “what works” (Evans and Benefield, 2001) in areas that would lead to lasting change.

What is evident through this SLR, is that this slice of the discourse, while illuminating, does not appear to focus on research that might lead to greater inclusivity nor offer solutions and pathways to greater inclusivity at levels of scale that might make the sector more genuinely equitable. Broader concepts such as intersectionality might perhaps be employed to great effect for better understanding gendered experiences of jazz and improvised music, particularly in quantitative or mixed-methods research. Crenshaw (2015) observes that “Intersectionality is an analytic sensibility,” “but a term can do no more than those who use it have the power to command” (Crenshaw, 2015). In this SLR, we encountered mostly in-depth, individual accounts of involvement in jazz and improvised music across a range of settings and circumstances. This dispersed view of the problem does not adequately capture how widespread these experiences (anecdotally) seem to be, nor how they might be mitigated. For these reasons, we find that this SLR raises many more questions than it answers: What is the true scope of gendered experiences of jazz and improvised music? Are the challenges and inequities described musical problems? Identity problems? Gender problems? Or, problems of workplace discrimination? Suzuki's (2013) description of “the instrumental jazz scene [as] a site where both gender and race merge in complex dialogues that involve authenticity, belonging, and career advancement” (p. 207) suggests that there are no easy answers.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

NC and TG contributed to develop the search, undertook the search, analysis and results, and contributed to editing the paper. NC wrote significant portions of the paper. TG wrote sections of the paper. MB advised on the SLR process and methods, senior reviewer in 3rd screening, contributed to analysis and results, and contributed to writing and editing of the paper. CHo and LD contributed to analysis and contributed to writing and editing of the paper. MP and RB contributed to analysis and contributed to editing of the paper. CHa contributed to analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council (ARC) Special Research Initiative for Australian Society, History and Culture, project number SR200200311 - Diversifying Music in Australia: Gender Equity in Jazz and Improvisation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmed, S. (2006). Orientations: toward a queer phenomenology. GLQ J. Lesbian Gay Stud. 12, 543–574. doi: 10.1215/10642684-2006-002

Allen, J. A. (1994). The constructivist paradigm: values and ethics. J. Teach. Soc. Work 8, 31–54. doi: 10.1300/J067v08n01_03

Appleton, G. (1982). Women in the Arts: A Study by the Research Advisory Group of Women in the Arts Project. Sydney, NSW: Policy and Planning, Australia Council.

Banks, M., and Milestone, K. (2011). Individualization, gender and cultural work. Gender Work Org. 18, 73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00535.x

Barrett, M. S., Creech, A., and Zhukov, K. (2021). Creative collaboration and collaborative creativity: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 12, 1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713445

Bird, S. R., and Rhoton, L. A. (2021). Seeing isn't always believing: gender, academic STEM, and women scientists' perceptions of career opportunities. Gender Soc. 35, 422–448. doi: 10.1177/08912432211008814

Borgo, D. (2002). Negotiating freedom: values and practices in contemporary improvised music. Black Music Res. J. 22, 165–188. doi: 10.2307/1519955

Browning, B. (2007). “Something's only “technical” when you don't know it”: conversations with Rosângela Silvestre and Steve Coleman. Women Perform. J. Feminist Theory 17, 171–184. doi: 10.1080/07407700701396458

Butler, J. (2006). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Caudwell, J. (2012). Jazzwomen: music, sound, gender, and sexuality. Ann. Leis. Res. 15, 389–403. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2012.744275

Clancey, W. J. (2006). “Observation of work practices in natural settings,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, Eds K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, and R. R. Hoffman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 127–146.

Clark, A. E., D'ambrosio, C., and Zhu, R. (2021). Job quality and workplace gender diversity in Europe. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 183, 420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.01.012

Collins, P. H. (2002). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cooke, A., Smith, D., and Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 22, 1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938

Creech, A., Larouche, K., Generale, M., and Fortier, D. (2020). Creativity, music, and quality of later life: a systematic review. Psychol. Music doi: 10.1177/0305735620948114

Crenshaw, K. (2015, September 24). Why intersectionality can't wait. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2015/09/24/why-intersectionality-cant-wait/ (accessed June 30, 2022).

Denson, L. (2014). Perspectives on the Melbourne International Women's Jazz festival. Jazz Res. J. 8, 163–181. doi: 10.1558/jazz.v8i1-2.26774

Devenish, L., Sun, C., Hope, C., and Tomlinson, V. (2020). Teaching tertiary music in the #metoo era. Tempo 74, 30–37. doi: 10.1017/S0040298219001153

Dibley, B., and Gayo, M. (2018). Favourite sounds: the Australian music field. Media Int. Aust. 167, 146–161. doi: 10.1177/1329878X18768059

Evans, J., and Benefield, P. (2001). Systematic reviews of educational research: does the medical model fit? Br. Educ. Res. J. 27, 527–541. doi: 10.1080/01411920120095717

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). “Case study,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 301–316.

Gill, R. (2002). Cool, creative and egalitarian? Exploring gender in project-based new media work in Euro. Inform. Commun. Soc. 5, 70–89. doi: 10.1080/13691180110117668

Hannaford, M. (2017). Subjective (re)positioning in musical improvisation: analyzing the work of five female improvisers. Music Theory Online 23, 1–26. doi: 10.30535/mto.23.2.7

Heble, A. (2000). Landing on the Wrong Note: Jazz, Dissonance, and Critical Practice, 1st Edn. London: Taylor and Francis Group.

Heble, A., and Siddall, G. (2000). “Nice work if you can get it: women in jazz,” in Landing on the Wrong Note: Jazz, Dissonance, and Critical Practice, Ed A. Heble (London: Taylor and Francis Group), 141–165.

Hope, C. (2017). Why is there so little space for women in jazz music?. The Conversation. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/why-is-there-so-little-space-for-women-in-jazz-music-79181 (accessed June 26, 2022).

Istvandity, L. (2016). Sophisticated lady: female vocalists and gendered identity in the Brisbane jazz scene. J. World Popul. Music 3, 75–89. doi: 10.1558/jwpm.v3i1.31197

Joanna Briggs Institute (2017). The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews: Checklist for Qualitative Research. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available online at: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017_0.pdf (accessed June 30, 2022).

Jovicevic, J. (2021). Gender perspectives of instrumental jazz performers in Southeastern Europe. Muzikologija 30, 149–164. doi: 10.2298/MUZ2130149J

Kirschbaum, C. (2007). Careers in the right beat: US jazz musicians' typical and non-typical trajectories. Career Dev. Int. 12, 187–201. doi: 10.1108/13620430710733659

Lewis, G. E. (2016). “Foreword: who is jazz?,” in Jazz Worlds/World Jazz, Eds P. V. Bohlman and G. Plastino (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press), ix–xxiv.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 6, e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

MacDonald, R. A. R., and Wilson, G. B. (2006). Constructions of jazz: how jazz musicians present their collaborative musical practice. Musicae Scientiae 10, 59–83. doi: 10.1177/102986490601000104

McAndrew, S., and Widdop, P. (2021). 'The man that got away': gender inequalities in the consumption and production of jazz. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 24, 690–716. doi: 10.1177/13675494211006091

McDonagh, M., Peterson, K., Raina, P., Chang, S., and Shekelle, P. (2013). “Avoiding bias in selecting studies,” in Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US)), 163–179.

McKeage, K. M. (2004). Gender and participation in high school and college instrumental jazz ensembles. J. Res. Music Educ. 52, 343–356. doi: 10.1177/002242940405200406

McSharry, J., Doherty, L., and Wilson, I. M. (2015). Psychosocial risks in a unique workplace environment: Safe Trad and traditional Irish musicians. Eur. Health Psychol. 17, 174–178. Available online at: https://ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/view/791

Metzelaar, H. (2004). Women and 'Kraakgeluiden': the participation of women improvisers in the Dutch electronic music scene. Organ. Sound 9, 199–206. doi: 10.1017/S1355771804000287

Miller, D. L. (2016). Gender and the artist archetype: understanding gender inequality in artistic careers. Sociol. Compass 10, 119–131. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12350

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Onsman, A., and Burke, R. (2018). Experimentation in Improvised Jazz: Chasing Ideas. New York, NY: Routledge.

Picaud, M. (2016). 'We try to have the best': how nationality, race and gender structure artists' circulations in the Paris jazz scene. Jazz Res. J. 10, 126–152. doi: 10.1558/jazz.v10i1-2.28344

PRS Foundation. (2022). Keychange. PRS Foundation. Available online at: https://prsfoundation.com/partnerships/international-partnerships/keychange/

Shriver, L. (2018, November 24). Jazz is dominated by men. So what? The Spectator. Available online at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/jazz-is-dominated-by-men-so-what- (accessed June 30, 2022).

Strong, C., and Raine, S. (2019). Towards Gender Equality in the Music Industry: Education, Practice and Strategies for Change. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Suzuki, Y. (2013). Two strikes and the double negative: the intersections of gender and race in the cases of female jazz saxophonists. Black Music Res. J. 33, 207–226. doi: 10.5406/blacmusiresej.33.2.0207

Tan, S. E. (2021). Special issue: decolonising music and music studies. Ethnomusicol. Forum 30, 4–8. doi: 10.1080/17411912.2021.1938445

Torres-Carrión, P. V., González-González, C. S., Aciar, S., and Rodríguez-Morales, G. (2018). “Methodology for systematic literature review applied to engineering and education,” in 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (Santa Cruz de Tenerife: IEEE), 1364–1373.

Tucker, S. (2002). Big ears: listening for gender in jazz studies. Curr. Musicol. 71–73, 375–408. doi: 10.7916/cm.v0i71-73.4831

Tucker, S. (2008). When did jazz go straight?: A queer question for jazz studies. Crit. Stud. Improv. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.21083/csieci.v4i2.850

Vanassche, E., and Kelchtermans, G. (2015). The state of the art in self-study of teacher education practices: a systematic literature review. J. Curr. Stud. 47, 508–528. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2014.995712

Vargas, J. H. C. (2008). Jazz and male blackness: the politics of sociability in South Central Los Angeles. Popul. Music Soc. 31, 37–56. doi: 10.1080/03007760601062983

Wahl, C., and Ellingson, S. (2018). Almost like a real band: navigating a gendered jazz art world. Qual. Sociol. 41, 445–471. doi: 10.1007/s11133-018-9388-9

Wehr-Flowers, E. (2006). Differences between male and female students' confidence, anxiety, and attitude toward learning jazz improvisation. J. Res. Music Educ. 54, 337–349. doi: 10.1177/002242940605400406

Welch, G., Papageorgi, I., Haddon, L., Creech, A., Morton, F., de Bezenac, C., et al. (2008). Musical genre and gender as factors in higher education learning in music. Res. Papers Educ. 23, 203–217. doi: 10.1080/02671520802048752

Wilcox, F. (Ed.). (2021). Women's Music for the Screen: Diverse Narratives in Sound. New York, NY: Routledge.

Williams, L. F. (2005). Reflexive ethnography: an ethnomusicologist's experience as a jazz musician in Zimbabwe. Black Music Res. J. 25, 155–165. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30039289

Willis, V. (2008). Be-in-tween the Spa[]ces: the location of women and subversion in jazz. J. Am. Cult. 31, 293–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-734X.2008.00677.x

Keywords: systematic (literature) review, gender, jazz, improvisation (music), PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis), intersectionality

Citation: Canham N, Goh T, Barrett MS, Hope C, Devenish L, Park M, Burke RL and Hall CA (2022) Gender as performance, experience, identity and, variable: A systematic review of gender research in jazz and improvisation. Front. Educ. 7:987420. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.987420

Received: 27 July 2022; Accepted: 07 November 2022;

Published: 28 November 2022.

Edited by:

Manpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, IndiaReviewed by:

Leon R. de Bruin, University of Melbourne, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Canham, Goh, Barrett, Hope, Devenish, Park, Burke and Hall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole Canham, bmljb2xlLmNhbmhhbUBtb25hc2guZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.