- 1Mathematics Study Program, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science, Lambung Mangkurat University, Banjarmasin, Indonesia

- 2Social Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Lambung Mangkurat University, Banjarmasin, Indonesia

Spirituality is now becoming popular because of the physical and mental advantages it brings to entrepreneurship. Regardless of its more philosophical measurement, changes owing to spirituality have been distinguished in people’s mental and standards of conduct. This investigation aims to examine the qualities related to university students, looking to explicitly comprehend the separate individual qualities or the psychological and cognitive inclinations. Tested on a sample of 300 students, Structural Equation Modeling results exhibit that those who participate in spiritual rituals tend to reinforce the mental and psychological credits connected with an entrepreneurial intention. Since entrepreneurial behavior is a priority to boost economic growth, spirituality should be coordinated as a mandatory subject in general instruction from primary school onward. The results of this exploration could be a model for the Indonesian government as they attempt to search for the best model for Entrepreneurship Education Program (EEP).

Introduction

Numerous administration activities in business have concluded that Indonesian youth are hesitant to become entrepreneurs (Wibowo et al., 2019; Kurniawati et al., 2020). Nonetheless, a new exploration (Handayati et al., 2020; Basuki, Widyanti and Rajiani, 2021) confirmed that Indonesian adolescents are extremely mindful and have an inspirational mentality toward the business venture. What is required presently is accurately identifying them. Subsequently, colleges and the public authority should investigate what kind of businesspeople they need in this country. Moreover, there is proof that we need to move attention from conventional instructing and assessment techniques toward less common ways to deal with entrepreneurial training, including appropriation practices such as spirituality (Margaça et al., 2020). Spirituality brings physical and mental advantages to its specialists (Iqbal and Ahmad, 2020). Examination of the impacts of spirituality has shown that there are clear psychological and cognitive preferences, including expanded memory limit, better focus, improved learning capacities and self-awareness, as well as lower nervousness levels (Robinson, 2020).

The impact of spirituality inside the field of entrepreneurship has been attracting insightful consideration (Smith et al., 2019; Block et al., 2020). The convergence of these constructs gives a comprehension of how an entrepreneur’s uplifted awareness and convictions can affect business exercises and vital qualities of the entrepreneurial process. These include the acknowledgment of chances and the formation of new pursuits. In a religious community or country like Indonesia, religion plays a more predominant role than social class (Anggadwita et al., 2017). Subsequently, strictness reflected in spirituality can trigger enterprising expectations (Sulung et al., 2020). The act of spirituality among Banjar people in South Kalimantan can be seen in a spirituality practice called the haul, which has consistently been held each year to commemorate KH. Zaini Abdul Ghani (Rajiani et al., 2019). This commemoration is the greatest spiritual practice in South Kalimantan, attracting countless travelers and even a large number of individuals from different districts. Strangely, all of Banjar society feel the benefit of this ritual by giving willful help to the achievement of the entire process of haul pilgrims. Something intriguing to note is the arrangement of a rest territory for visitors from different districts, significantly over one hundred kilometers from the area of the haul, beginning a few days prior and proceeding even after the haul has finished. Each rest region gives free food and beverages to the thousands of pilgrims. Additionally, numerous accessible conveniences are offered along the way, like housing, tire fixing services, medical assistance, and fuel.

This study aims to examine the individual and intellectual qualities of entrepreneurs as recognized by different scholars (for example, Turner and Gianiodis, 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Rajagopal, 2021) and the positive psychological and cognitive impacts presented by spirituality as affirmed by previous studies (Schnitker et al., 2021). Two research questions are placed: (1) does the act of spirituality contribute toward entrepreneurs’ psychological attributes? and (2) does the act of spirituality contribute to the learning of entrepreneurial cognitive processes?

These issues are significant because of the impact they could have on bringing spirituality into education, helping to advance students’ psychological and cognitive attributes that could in turn promote entrepreneurship (Rodrigues et al., 2019; Aryeh, 2020; Maritz et al., 2021). Consequently, this examination aims to investigate whether the psychological and cognitive attributes incited by the act of spirituality contribute to advancing psychological and cognitive characteristics related to potential entrepreneurs among university students.

Literature review

Entrepreneurs’ psychological and cognitive attributes

Researchers have long been focused on how and why entrepreneurs choose to seek out business ventures. Changing inspiration and conduct systems were examined, many of which have demonstrated conflicting results (Covin et al., 2020). The extra examination has distinguished specific psychological attributes that would incline individuals toward adventure creation, like responsibility, constancy, need for accomplishment, locus of control, capacity to bear uncertainty, hazard inclination, drive, and awareness of chance (Embi et al., 2019; Meyer and Meyer, 2020; Mujahid et al., 2020). Nonetheless, psychological attributes have been demonstrated to be unfit to distinguish between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs adequately because of the expected absence of agreement around such attributes. The shared complementarity between psychological attributes and cognitive factors produces a singular conduct that is the consequence of a person’s choice dependent on the people’s objective and way of thinking (Bergner, 2020). Consequently, cognitive factors offer help to investigate the qualities innate to entrepreneurship.

One of the ideas to consider while breaking down business from the viewpoint of cognitive hypothesis is alertness, as characterized by Neneh (2019), summed up as the capacity to discover without observing. The same author maintained that the understanding and mental portrayal of entrepreneurs varies from that of the rest of the populace because the previous is guided by entrepreneur alertness (EA), seen as a particular pattern of information-processing and insight and as a cognitive tool used in analyzing opportunities.

Chavoushi et al. (2021) confirmed that a few people exhibit this mental pattern and a propensity to search out and distinguish market vulnerability. They can comprehend data that does not find a place with their predominant mental outline and adjust it to incorporate the new data. In this way, EA can be considered a particular mental composition that empowers the person to be aware of new freedoms and react accordingly. The idea of EA is related to psychological and cognitive properties because these are related to veridical insight and translation. In contrast, the previous is related to how entrepreneurs see and comprehend the market. On the other hand, the last arrangements deal with the way to distinguish the main impetuses and essential variables behind market factors and moves and synergizes dynamic connections between them (Li et al., 2020).

Dheer and Lenartowicz (2020) opine that entrepreneurial cognitions are the information structures that individuals use to make appraisals, decisions, or choices, including the assessment of chances, the making of new pursuits, and the age of development. The cognitive perspective highlights the role of mental processes that bring about explicit practices, precisely the routes identified with individual decision-making in the quest for direct targets. Thus, the utilization of a cognitive approach in this setting looks to see how the entrepreneurs’ mental models assemble snippets of data that initially do not appear to have any kind of interconnection to encourage the foundation of new businesses.

Exploration directed by Middermann (2020) found that the cognitions of people with “proficient entrepreneurial cognitions” differ from those of business non-entrepreneurs. Likewise, Huber et al. (2020) contend that, besides the competencies and capacities demanded to operate businesses successfully, people must also possess a mental map that assists them in assessing the possible achievement of an undertaking before it is dispatched.

Teaching entrepreneurship: A new model

The debate on whether entrepreneurship can be taught or not is flourishing (Bhatia and Levina, 2020). However, scholars do accept that creative inspiration can be developed with tacit entrepreneurship schooling (Arsawan et al., 2020; García-Morales et al., 2020; Handayati et al., 2020). Consequently, some scientists, chipping away at the supposition that innovative mentalities are inert across the populace, concur that the related practices can be taught in formal education. There is developing acknowledgment that psychological and cognitive processes may bring about a more thorough comprehension of variables impacting entrepreneurial behavior. Margaça et al. (2021) contend that the psychological characteristics of entrepreneurs can be learned or potentially reinforced. Hägg and Kurczewska (2020) underline that the accomplishments of instructive courses in entrepreneurship rely fundamentally upon being able to teach these psychological characteristics. Although Jena (2020), among others, has avowed stimulating entrepreneurial characteristics since an early age and may support entrepreneurship as a lifelong alternative, no observational testing of their assessment has been embraced.

Much effort has been placed into supporting entrepreneurship, and this pattern has been trending worldwide, including in Indonesia. Notwithstanding, contrasted with different nations, new entrepreneurs in Indonesia are lacking. Indonesia’s accomplishment is behind its neighboring countries of Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, and Malaysia (Handayati et al., 2020). To expand the number of businesspeople, the Indonesian government has trialed a few advancements, including establishing entrepreneurship education programs in colleges (Saptono et al., 2020) with unconvincing outcomes. This is demonstrated by the high joblessness level of college graduates (Siregar, 2020). In particular, business training has not formed an entrepreneurship mentality in students. In other words, the current substance of courses has not yet reached the core component of entrepreneurship (Ingalagi et al., 2021) and, at this point, does not advance individual self-improvement (Haque et al., 2019). Undoubtedly, the cognitive perspective on entrepreneurship calls for new instructions to be conveyed to help students become entrepreneurs.

The point departure proposed by the authors of the present paper is that this new learning process should include spirituality. Febriani (2020) characterizes spirituality as one’s progress toward and experience of association with oneself, connectedness with others and nature, and connectedness with the transcendent. Some developed or developing countries have applied this concept as a learning strategy (Bettignies, 2019; Meyer and Kot, 2019; Nawaz et al., 2020; Khalid, 2021; Rahiman et al., 2021).

These empirical results allowed us to assume the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): the practice of spirituality positively strengthens students’ capacity to acquire the psychological attributes of potential entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): spirituality positively strengthens students’ capacity to acquire the cognitive attributes of potential entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): the practice of spirituality influences students’ propensity to start their own business.

Data and methodology

This study is a quantitative method aimed at testing and identifying variable dependency by analyzing the interaction of spiritual, psychological, and cognitive attributes toward the propensity to set up businesses among university students in South Kalimantan, Indonesia. The 300 respondents were made up of last year’s students. Hair et al. (2012) assure that the minimum number of samples is five times the number of indicators. Since there are 17 indicators, the minimum number of samples is 85. Thus, 300 samples is adequate for hypothesis testing. The sample selection method uses purposive sampling, which is based on the willingness of the Whatsapp social media group members to participate. This group contains final year students. Psychological factors were estimated, utilizing a 6-item test adapted from the work of Mujahid et al. (2020). The items are labeled self-confidence (x1.1), self-realization (x1.2), autonomy (x1.3), innovation (x1.4), self-control (x1.5), and tolerance of risk (x1.6). Cognitive factors were estimated with identification of new opportunities (x2.1), valuation of opportunity (x2.2), entrepreneur alertness (x2.3), effective problem solving (x2.4), lessened perception of risk (x2.5), and greater perception of success than failure (x2.6) adapted from Dheer and Lenartowicz (2020) and Chavoushi et al. (2021). To identify the practice of spirituality, students were asked, “Do you regularly attend the haul of KH. Zaini bin Abdul Ghani?” This question is to provide the foundation for comparing the propensity for entrepreneurial behavior among those who engage in spirituality and those who do not. The propensity for entrepreneurial behavior is quantified with the Measure of Entrepreneurial Tendencies and Abilities (META), developed by Ahmetoglu et al. (2015). META has four dimensions: Entrepreneurial Proactivity (y2.1), Entrepreneurial Creativity (y2.2), Entrepreneurial Opportunism (y2.3), and Entrepreneurial Vision (y2.4). Items were operated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’, and Structural Equation Modeling with the assistance of SPSS Amos was used to examine the relationship.

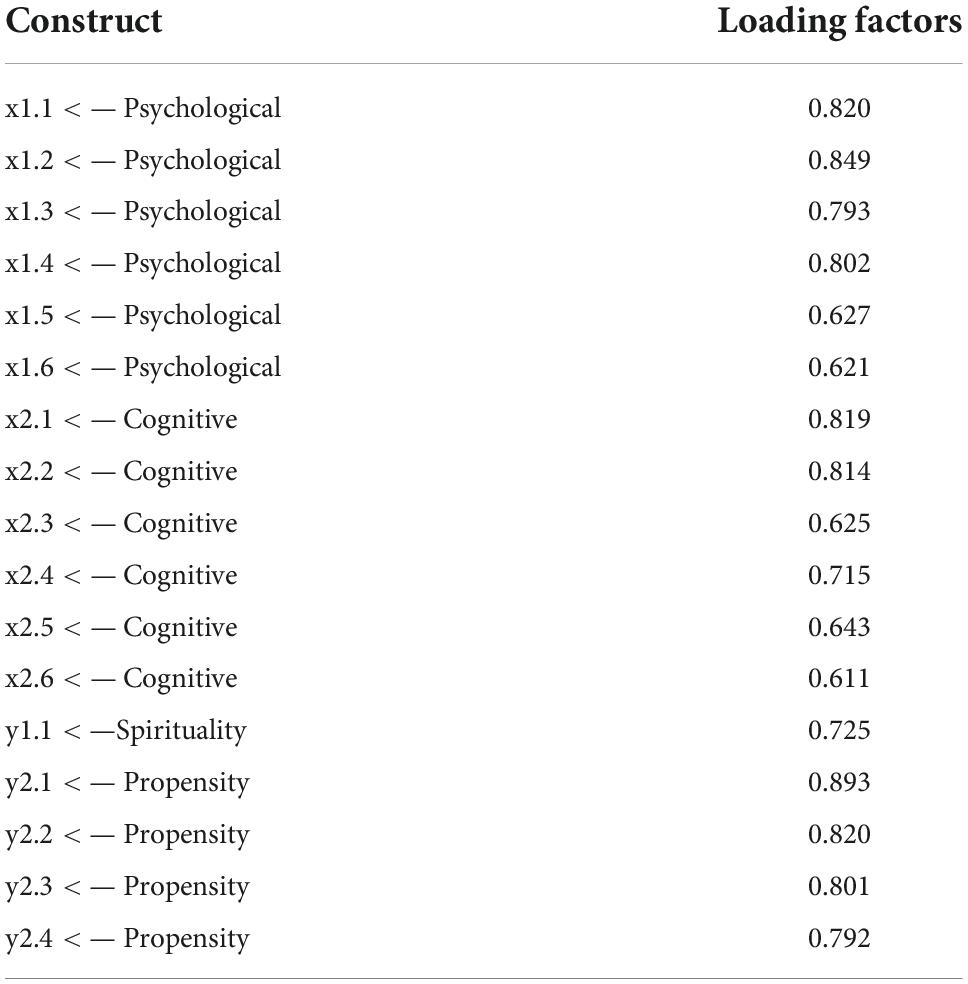

SEM includes a series of statistical procedures for assessing underlying relations between variables. Schreiber et al. (2006) confirm that the measures enabling justification were mainly: Chi-square (χ2), The Minimum Sample Discrepancy Function (χ2/df), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation). The coefficient alpha was examined to determine reliability, and those values must be 0.60 or higher (Bonett and Wright, 2015). Factors loading are estimated to ascertain discriminant validity by retaining factors loading above 0.50 in the model (Hair et al., 2012).

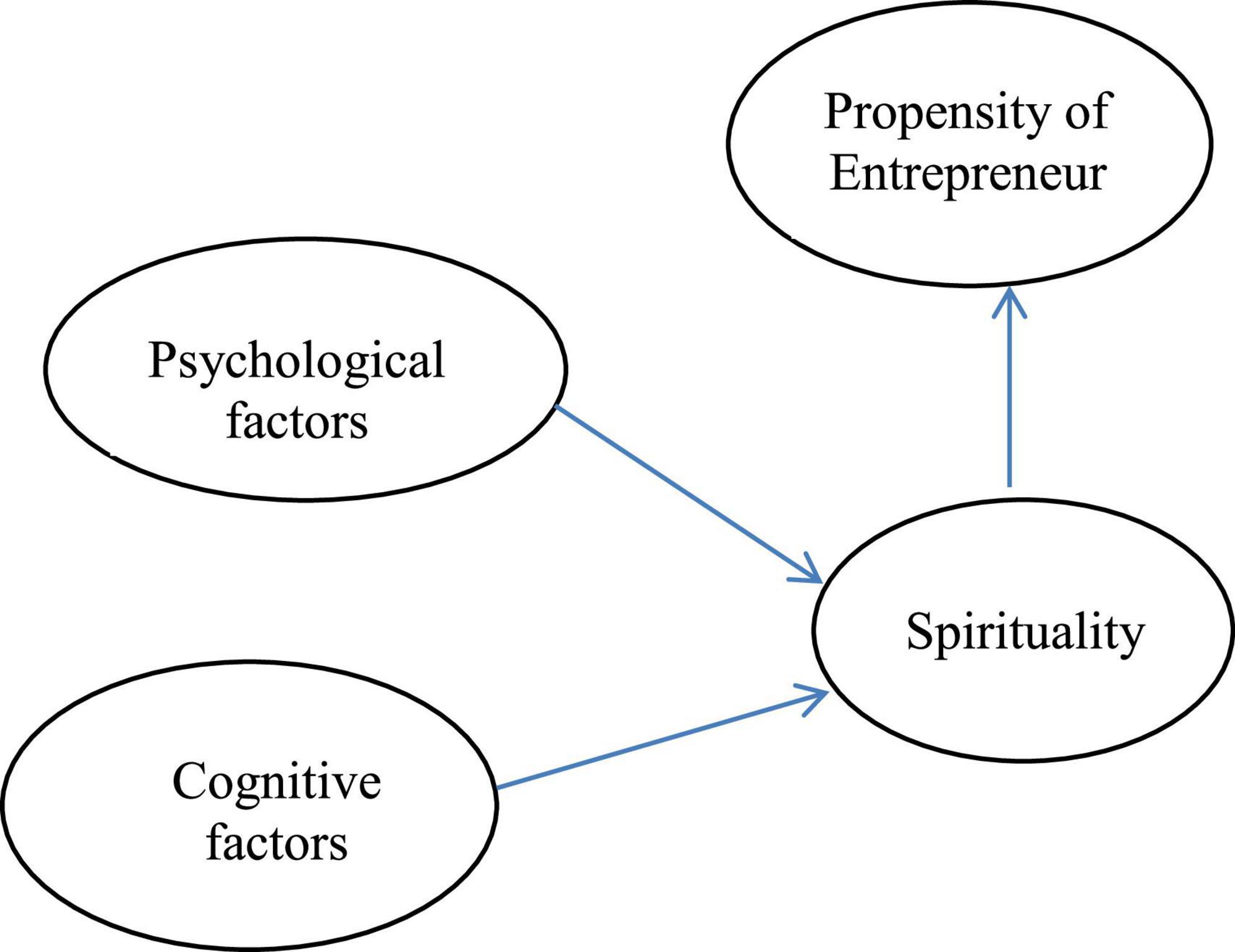

The theoretical model of the research is summed up in Figure 1.

Yet, self-reported questionnaires are prone to social desirability bias, which is the propensity of respondents to reply in a socially acceptable manner. Following Podsakoff et al. (2012), sources of method bias are observed in the Most Extreme Responses (MRS). They are items with the highest loading factor in Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Mishra, 2016). Those items are omitted, and then the model is recalculated. If the result shows no significant change in χ2, χ2/df, GFI, AGFI, CFI, and RMSEA, it is determined that there is no bias.

Results and discussions

The measurement model in Table 1 shows that all factors loading exceeded 0.50, confirming that the instrument had fulfilled satisfactory convergent validity criteria.

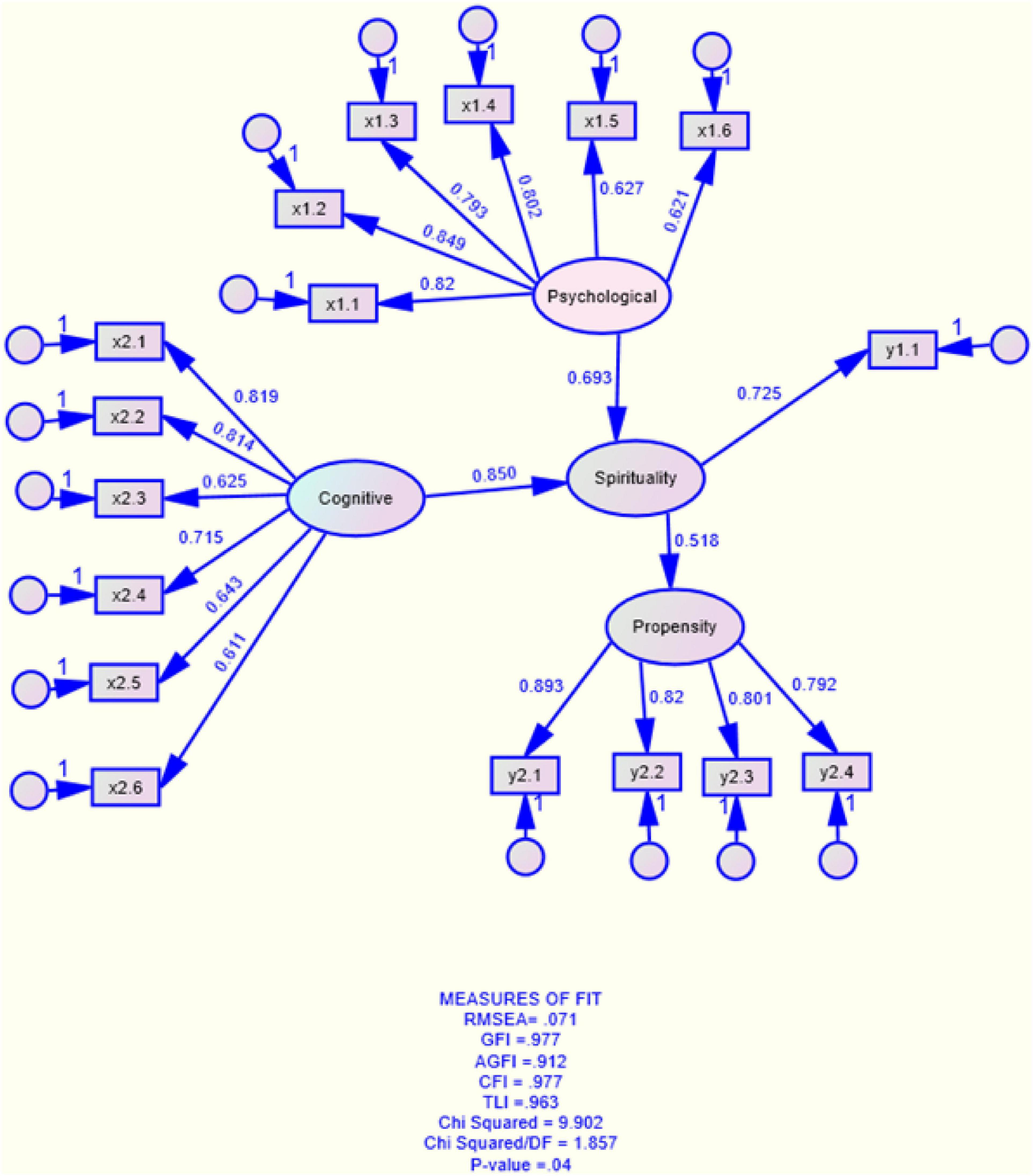

The full specified model of the research is depicted in Figure 2.

SEM needs a small value for Chi-square statistic (χ2) and probability (P) smaller than 0.05 and other alternative measurements to evaluate the model fit (Shipley and Douma, 2020). This model meets the model’s goodness-of-fit by referring to the χ2 test (χ2 = 9.902) and probability (P = 0.04). Also, when examined from other measurements, the model indicates an appropriate fitness: CMIN/DF = 1.857 (expected smaller than 2), GFI = 0.992 (higher than 0.90), AGFI = 0.912 (higher than 0.90), CFI = 0.977 (higher than 0.95), TLI = 0.963 (higher than 0.95), and RMSEA = 0.071 (higher than 0.06) (Hair et al., 2012).

Most Extreme Responses (MRS) were identified in four items: (a) In the future, I intend to participate in founding a new business venture; (b) In the end, you are convinced of the probability that the business will thrive; (c) I have recently searched for information on ways and means to find a new business model; and (d) If my research during my study has marketing potential, I would like to participate in the new business model to commercialize the research. However, after omitting those four items, the result remains the same, indicating that there is no bias of respondents answering questions in a socially acceptable manner.

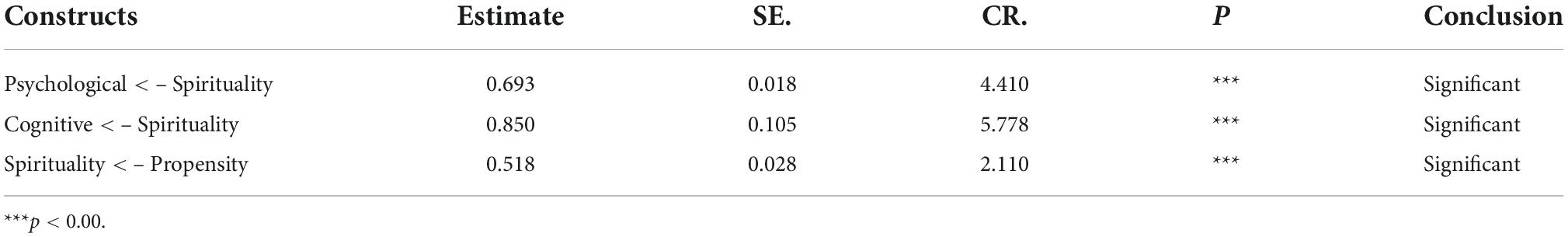

The summary result of structural equation modeling is presented in Table 2.

The table indicated that three paths are significant. The critical ratio (CR) value of psychological factors = 4.410 and significance of < 0.000 confirm the first hypothesis: the practice of spirituality positively strengthens students’ capacity to acquire the psychological attributes of potential entrepreneurs.

Similarly, the critical ratio (CR) of cognitive attributes = 5.778 and significance of < 0.000 confirm the second hypothesis: the practice of spirituality positively strengthens students’ capacity to acquire the cognitive attributes of potential entrepreneurs. Finally, the critical ratio (CR) of spirituality = 0.2110 and significance of < 0.000 confirm the third hypothesis that the practice of spirituality influences students’ propensity to start their own businesses.

The result of this research clearly indicates that spirituality affects the entrepreneurial tendency of students in South Kalimantan, Indonesia, supporting previous studies conducted in other regions of Indonesia (Sulung et al., 2020).

A positive and critical impact of spiritual practices inside entrepreneurial ideas gives an expected answer for the difficulties of understanding the entrepreneurial mindset. Up to this point, conventional entrepreneurship literature has commonly disregarded qualities like religion and spirituality when leading the investigation into entrepreneurial motivation and behavior.

A significant part of the entrepreneurship literature proposes that organizations thrive where entrepreneurial qualities like individualism, rationality, risk-taking, self-interest, autonomy, achievement, self-reliance, and long-term orientation prevail (Embi et al., 2019; Mujahid et al., 2020). Consequently two suppositions : (1) values widespread inside the entirety of entrepreneurs, and (2) values fundamentally identified with achievement in new pursuit creation, come up.

Similarly, as there is no ideal approach to seeking venture development, there appears to be no best entrepreneurship model pertinent to all circumstances and people. Examination of the improvement of entrepreneurs recommends that the craving for self-satisfaction and essential work are regularly the primary motivators for the individuals who choose to go into their own business (Smith et al., 2019; Block et al., 2020), which are the two elements related with most meanings of spirituality (Febriani, 2020). This condition is suited to Banjarese Indonesian culture, where Islam represents the central constituent in ethnic acknowledgment. All Banjarese Indonesians are Muslim, and Islam affects lifestyle. Subsequently, Islam affects fundamental aspects of everyday life (Basuki, Widyanti and Rajiani, 2021), including the thought of the prominent ulema KH. Zaini bin Abdul Ghani on entrepreneurship. Although most of Indonesians are Muslim, an ulema is hardly portrayed as an influential figure in rehearsing business.

KH. Zaini Abdul Ghani is an exception as he was successful in the concept of teaching religion as well as developing an economic base that benefited the community. He taught that entrepreneurship was a duty to communities, families, and the Almighty. This deeply engrained virtue strongly impacts people’s attitudes and motivations toward entrepreneurship in a way that is significantly different from many traditional entrepreneurs.

Millions of people mourned his passing, and his haul became the arena of spirituality, with students regularly attending the ceremony.

Though the current trends emphasize the mastery of information systems (Khalid and Kot, 2021), digital payment (Chaveesuk et al., 2022), university product commercialization (Ismail et al., 2020) and emotional intelligence (Rahiman et al., 2020), policymakers, including entrepreneurship education programs evaluating university performance, should also include spirituality. Consequently, university managers must be aware that the best way to promote entrepreneurial activity in their institutions is to create the conditions necessary to increase the spirituality of their academics. Further, entrepreneurship education programs run by Indonesian universities should focus on strengthening the spirituality of the potential entrepreneurs by conveying all the obstacles when launching a new business venture. However, it is not about committing to psychological attributes and the cognitive domain of entrepreneurial work. Instead, the three paths can be developed in parallel and complement their essential synergies in molding prospective entrepreneurs emerging as fresh university graduates.

Conclusion

A significant part of the conventional entrepreneurship literature revolves around estimating execution factors that are not difficult to assemble, as opposed to those that are significant to the religious or spiritual entrepreneur. Since entrepreneurs with a tendency toward these qualities may characterize achievement uniquely in contrast to traditional entrepreneurs, monetary measures might be of negligible significance to them. The entrepreneurship education program in Indonesian universities should utilize proportions of achievement directly relevant to spiritual and religious entrepreneurs on an individual premise instead of focusing exclusively on targeting monetary measures. In a religious society like Indonesia, numerous businesspeople feel that rewarding their networks, clients, and different firm partners or helping others achieve individual objectives is a good sign that they are prevailing in their business attempts. In that capacity, applying the Western maverick idea in surveying potential entrepreneurs might not be pertinent to yielding the expected outcome.

Despite the effort we put into the plan of the current investigation, it is not without restrictions. The examination was exploratory and cross-sectional, which makes it hard to build up causal connections between the factors of our model. In this way, we have suggested that psychological attributes, cognitive characteristics, and spirituality predict entrepreneurial propensity among students in any case. But it could be that the relationship is vice versa, i.e., that the ambition to become an entrepreneur is what determines the potential psychological attributes, cognitive factors, and spirituality. Along these lines, future research should conduct a longitudinal report that could affirm the causal connections that presented themselves.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SH and IR: conceptualization. SH and EA: methodology. EA: software, resources, data curation, investigation, visualization, and project administration. SH, EA, and IR: validation. IR: formal analysis and writing—review and editing. SH: writing—original draft preparation, supervision, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Rector of Lambung Mangkurat University for facilitating this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmetoglu, G., Harding, X., Akhtar, R., and Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2015). Predictors of creative achievement: Assessing the impact of entrepreneurial potential, perfectionism, and employee engagement. Creat. Res. J. 27, 198–205. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2015.1030293

Anggadwita, G., Ramadani, V., Alamanda, D. T., Ratten, V., and Hashani, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions from an Islamic perspective: A study of Muslim entrepreneurs in Indonesia. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 31, 165–179. doi: 10.1504/IJESB.2017.10004845

Arsawan, I., Koval, V., Rajiani, I., Rustiarini, N. W., Supartha, W. G., and Suryantini, N. P. S. (2020). Leveraging knowledge sharing and innovation culture into SMEs sustainable competitive advantage. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 71, 405–428. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-04-2020-0192

Aryeh, D. N. A. (2020). “The relationship between christianity and entrepreneurship: A curriculum for leadership training for pastors in Africa,” in Understanding the relationship between religion and entrepreneurship, eds A. B. Salem and K. Tamzini (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 25–50. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-1802-1.ch002

Basuki Widyanti, R., and Rajiani, I. (2021). Nascent entrepreneurs of millennial generations in the emerging market of Indonesia. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 9, 151–165. doi: 10.15678/EBER.2021.090210

Bergner, S. (2020). *Being smart is not enough: Personality traits and vocational interests incrementally predict intention, status and success of leaders and entrepreneurs beyond cognitive ability. Front. Psychol. 11:204. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00204

Bettignies, H. C. D. (2019). “Spirituality, caring organisations and corporate effectiveness: Are business schools developing such a path toward a better future?,” in Caring management in the new economy, eds S. Ora and Z. László (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 263–289. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14199-8_14

Bhatia, A. K., and Levina, N. (2020). Diverse rationalities of entrepreneurship education: An epistemic stance perspective. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 19, 323–344. doi: 10.5465/amle.2019.0201

Block, J., Fisch, C., and Rehan, F. (2020). Religion and entrepreneurship: A map of the field and a bibliometric analysis. Manag. Rev. Q. 70, 591–627. doi: 10.1007/s11301-019-00177-2

Bonett, D. G., and Wright, T. A. (2015). Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 3–15. doi: 10.1002/job.1960

Chaveesuk, S., Khalid, B., and Chaiyasoonthorn, W. (2022). Continuance intention to use digital payments in mitigating the spread of COVID-19 virus. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 6, 527–536. doi: 10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.12.001

Chavoushi, Z. H., Zali, M. R., Valliere, D., Faghih, N., Hejazi, R., and Dehkordi, A. M. (2021). Entrepreneurial alertness: A systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 33, 123–152. doi: 10.1080/08276331.2020.1764736

Covin, J. G., Rigtering, J. C., Hughes, M., Kraus, S., Cheng, C. F., and Bouncken, R. B. (2020). Individual and team entrepreneurial orientation: Scale development and configurations for success. J. Bus. Res. 112, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.023

Dheer, R. J., and Lenartowicz, T. (2020). Effect of generational status on immigrants’ intentions to start new ventures: The role of cognitions. J. World Bus. 55:101069. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101069

Embi, N. A. C., Jaiyeoba, H. B., and Yussof, S. A. (2019). The effects of students’ entrepreneurial characteristics on their propensity to become entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Educ. Train. 61, 1020–1037. doi: 10.1108/ET-11-2018-0229

Febriani, R. (2020). Spirituality to increase entrepreneur’s satisfaction and performance: The Islamic perspective. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 12, 64–69.

García-Morales, V. J., Martín-Rojas, R., and Garde-Sánchez, R. (2020). How to encourage social entrepreneurship action? Using Web 2.0 technologies in higher education institutions. J. Bus. Ethics 161, 329–350. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04216-6

Hägg, G., and Kurczewska, A. (2020). Guiding the student entrepreneur–considering the emergent adult within the pedagogy–andragogy continuum in entrepreneurship education. Educ. Train. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1108/ET-03-2020-0069

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., and Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 40, 414–433. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Handayati, P., Wulandari, D., Soetjipto, B. E., Wibowo, A., and Narmaditya, B. S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship education promote vocational students’ entrepreneurial mindset? Heliyon 6:e05426. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05426

Haque, U. A., Kot, S., and Imran, M. (2019). The moderating role of environmental disaster in relation to microfinance’s non-financial services and women’s micro-enterprise sustainability. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 8, 355–373. doi: 10.9770/jssi.2019.8.3(6)

Huber, L. R., Sloof, R., Van Praag, M., and Parker, S. C. (2020). Diverse cognitive skills and team performance: A field experiment based on an entrepreneurship education program. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 177, 569–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.06.030

Ingalagi, S. S., Nawaz, N., Rahiman, H. U., Hariharasudan, A., and Hundekar, V. (2021). Unveiling the crucial factors of women entrepreneurship in the 21st century. Soc. Sci. 10:153. doi: 10.3390/socsci10050153

Iqbal, Q., and Ahmad, N. H. (2020). Workplace spirituality and nepotism-favouritism in selected ASEAN countries: The role of gender as moderator. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 14, 31–49. doi: 10.1108/JABS-01-2018-0019

Ismail, N., Kot, S., Abd Aziz, A. S., and Rajiani, I. (2020). From innovation to market: Integrating university and industry perspectives towards commercialising research output. Forum Sci. Oecon. 8, 99–115.

Jena, R. K. (2020). Measuring the impact of business management student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 107:106275. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106275

Khalid, B. (2021). Entrepreneurial insight of purchase intention and co-developing behavior of organic food consumption. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 24, 142–163. doi: 10.17512/pjms.2021.24.1.09

Khalid, B., and Kot, M. (2021). *The impact of accounting information systems on performance management in the banking sector. IBIMA Bus. Rev. 2021, 1947–3788. doi: 10.5171/2021.578902

Kurniawati, E., Siddiq, A., and Huda, I. (2020). E-commerce opportunities in the 4.0 era innovative entrepreneurship management development. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 21, 199–210. doi: 10.17512/pjms.2020.21.1.15

Li, C., Murad, M., Shahzad, F., Khan, M. A. S., Ashraf, S. F., and Dogbe, C. S. K. (2020). Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 11:1611. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01611

Margaça, C., Hernández-Sánchez, B., Sánchez-García, J. C., and Cardella, G. M. (2021). The roles of psychological capital and gender in university students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Front. Psychol. 11:615910. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.615910

Margaça, C., Sánchez-García, J. C., and Sánchez, B. H. (2020). “Entrepreneurial intention: A match between spirituality and resilience,” in Understanding the relationship between religion and entrepreneurship, eds K. Tamzini and B. Salem (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 1–24. doi: 10.4018/978-1-7998-1802-1.ch001

Maritz, A., Jones, C., Foley, D., De Klerk, S., Eager, B., and Nguyen, Q. (2021). “Entrepreneurship education in Australia,” in Annals of entrepreneurship education and pedagogy–2021, eds C. H. Matthews and E. W. Liguori (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 208–226.

Meyer, N., and Kot, S. (2019). Entrepreneurial motivation: A cross country comparison between polish and South African students. Transform. Bus. Econ. 18, 155–167.

Meyer, N., and Meyer, D. F. (2020). Entrepreneurship as a predictive factor for employment and investment: The case of selected European countries. Euroeconomica 39, 165–180.

Middermann, L. H. (2020). Do immigrant entrepreneurs have natural cognitive advantages for international entrepreneurial activity? Sustainability 12, 1–13. doi: 10.3390/su12072791

Mishra, M. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) as an analytical technique to assess measurement error in survey research: A review. Paradigm 20, 97–112. doi: 10.1177/0971890716672933

Mujahid, S., Mubarik, M. S., and Naghavi, N. (2020). Developing entrepreneurial intentions: What matters? Middle East J. Manag. 7, 41–59. doi: 10.1504/MEJM.2020.105225

Nawaz, N., Durst, S., Hariharasudan, A., and Shamugia, Z. (2020). Knowledge management practices in higher education institutions-a comparative study. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 22, 291–308. doi: 10.17512/pjms.2020.22.2.20

Neneh, B. N. (2019). From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behavior: The role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 138, 273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.020

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Rahiman, H. U., Nawaz, N., Kodikal, R., and Hariharasudan, A. (2021). Effective information system and organisational efficiency. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 24, 398–413. doi: 10.17512/pjms.2021.24.2.25

Rahiman, U. R., Kodikal, R., Biswas, S., and Hariharasudan, A. (2020). A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and organizational commitment. Pol. J. Manage. Stud. 22, 418–433. doi: 10.17512/pjms.2020.22.1.27

Rajagopal, A. (2021). “Contemporary entrepreneurial practices,” in Epistemological attributions to entrepreneurial firms, ed. A. Rajagopal (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 63–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-64635-6_3

Rajiani, I., Hadi, S., and Abbas, E. W. (2019). “The value in Banjarese culture through the thought of a prominent ulema as a model of developing entrepreneurship based religion,” in Proceedings of the 33rd international business information management association conference, IBIMA 2019: Education excellence and innovation management through vision 2020, (Seville: International Business Information Management Association, IBIMA), 258–264.

Robinson, O. C. (2020). A dialectical approach to understanding the relationship between science and spirituality: The MODI model. J. Study Spiritual. 10, 15–28. doi: 10.1080/20440243.2020.1726045

Rodrigues, A. P., Jorge, F. E., Pires, C. A., and António, P. (2019). The contribution of emotional intelligence and spirituality in understanding creativity and entrepreneurial intention of higher education students. Educ. Train. 61, 870–894. doi: 10.1108/ET-01-2018-0026

Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Narmaditya, B. S., Karyaningsih, R. P. D., and Yanto, H. (2020). Does entrepreneurial education matter for Indonesian students’ entrepreneurial preparation: The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset and knowledge. Cogent Educ. 7:1836728. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2020.1836728

Schnitker, S. A., Medenwaldt, J. M., and Williams, E. G. (2021). Religiosity in adolescence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 40, 155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.09.012

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., and King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 99, 323–338. doi: 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Shipley, B., and Douma, J. C. (2020). Generalized AIC and chi-squared statistics for path models consistent with directed acyclic graphs. Ecology 101:e02960. doi: 10.1002/ecy.2960

Siregar, T. H. (2020). Impacts of minimum wages on employment and unemployment in Indonesia. J. Asian Pac. Econ. 25, 62–78. doi: 10.1080/13547860.2019.1625585

Smith, B. R., Conger, M. J., McMullen, J. S., and Neubert, M. J. (2019). Why believe? The promise of research on the role of religion in entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 11, 1–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jbvi.2019.e00119

Sulung, L. A. K., Putri, N. I. S., Robbani, M. M., and Ririh, K. R. (2020). Religion, attitude, and entrepreneurship intention in Indonesia. South East Asian J. Manag. 14, 44–62. doi: 10.21002/seam.v14i1.10898

Turner, T., and Gianiodis, P. (2018). Entrepreneurship unleashed: Understanding entrepreneurial education outside of the business school. J. Small Bus. Manag. 56, 131–149. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12365

Wang, S., Hung, K., and Huang, W. J. (2019). Motivations for entrepreneurship in the tourism and hospitality sector: A social cognitive theory perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 78, 78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.018

Keywords: spirituality, entrepreneurship, psychological, cognitive, university

Citation: Hadi S, Abbas EW and Rajiani I (2022) Should spirituality be included in entrepreneurship education program curriculum to boost students’ entrepreneurial intention? Front. Educ. 7:977089. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.977089

Received: 24 June 2022; Accepted: 08 September 2022;

Published: 12 October 2022.

Edited by:

Hariharasudan A, Kalasalingam University, IndiaReviewed by:

Bilal Khalid, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, ThailandNishad Nawaz, Kingdom University, Bahrain

Copyright © 2022 Hadi, Abbas and Rajiani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sutarto Hadi, c3V0YXJ0b0B1bG0uYWMuaWQ=

Sutarto Hadi

Sutarto Hadi Ersis Warmansyah Abbas

Ersis Warmansyah Abbas Ismi Rajiani

Ismi Rajiani