- Department of English Language and Literature, School of Foreign Languages, China University of Petroleum, Beijing, China

This study aimed to evaluate an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) textbook by examining English as a Foreign Language (EFL) graduate students’ beliefs about the textbook through metaphor analysis in a Chinese University setting. This is mainly a descriptive research in nature, and a qualitative research method was employed, supplemented by a quantitative method. The participants of the study are a total of 147 first-year EFL graduate students from a public university in the city of Beijing, China. This evaluation revealed that the EAP textbook provided joy, security, grit, and curiosity for theses students, and at the same time, it was reported as old-fashioned, exam-oriented and teacher-directed. It would be more appropriate with some modifications and also with some additional materials to meet the needs of the EFL graduate students, and some possible implications for teachers and researchers were also suggested in the study.

1. Introduction

Textbooks influence academic growth and success of students at all levels of education (Azizifar et al., 2010). Most specifically in the field of language learning, textbooks become paramount as they play a major role in providing learning input, guidance and insistence for language learning. As for graduate students, in academic settings they need to acquire the ability to read papers in English and communicate in English with experts in the international community. But, the quality and efficacy of textbooks could be challenges in connection with their relevance to the curriculum standards and learning outcomes of students, and at times, students fail to get much assistance from textbooks because of certain reasons that consequently hinder students’ progress and performance in learning English as a foreign language (Lee and Wong, 2000). In a context where these learners have little or no access to English outside classrooms, English for Academic Purposes (EAP) textbooks play a significant role in giving learning input and providing help and persistence for the academic language learning. Scholars have identified problems of EAP textbooks in a Chinese university setting (e.g., Cai, 2011; Ding and Jiang, 2015). Evaluation of EAP textbooks could give further insights into the future revision and/or designing of the textbooks for learners of academic English (Sajjadi, 2011). Many previous studies (e.g., Jamshidi and Soori, 2013; Mohammadi and Abdi, 2014; Harbi, 2017; Lodhi et al., 2019) examined efficiency and appropriateness of textbooks by using scales or checklist for evaluating textbooks. Some study (e.g., Jou, 2017) reported English language learners’ reactions to a graduate-level academic writing textbook through interviews. Could checklists of interviews fully reflect underlying or subconscious beliefs of learners? The limitation of many scales or checklists is “the use of somewhat arbitrary and restricted timeframes instruction” (Boyle et al., 2015, p.190). Metaphors could provide more flexibility, adaptation, or imagination. However, few studies have done evaluations of EAP textbooks through metaphor analysis from students’ perspective in an EFL setting.

2. Metaphors and metaphor analysis

Metaphor, as a perception tool, provides us with ways for meaning transfer to discover and accounts for how people think about events, facts, and concepts through analogies (Saban et al., 2007; Zheng and Song, 2010; Han, 2011). According to McGrath (2006a) metaphoric language is particularly revealing of the subconscious beliefs and attitudes that underlie consciously held opinions. Lu and Liu (2013) stated that researchers could regard metaphor as a kind of discourse based on sentences and paragraphs beyond vocabulary, and metaphor analysis was regarded as a branch of discourse analysis and a research method. De Guerrero and Villamil (2002) defined metaphor analysis as “a method that systematically examines elicited or spontaneous metaphors in discourse as a means for uncovering underlying conceptualizations” (p.96). According to their conclusions, the process of applying metaphor analysis in a study was summarized: collecting metaphors about the topic, generalizing those metaphors, and using the results to show the implied meanings behind the metaphors. Studies applying metaphor analysis have explored EFL learners’ beliefs about English learning (e.g., Shi and Liu, 2012; Lu and Liu, 2013), EFL Learners’ beliefs about speaking English and being good speakers (Dincer, 2017), students’ perceptions about English writing (Erdogan and Erdogan, 2013), learners’ perceptions of being international students (Yayci, 2017), beliefs about the role of teachers (e.g., De Guerrero and Villamil, 2002; Saban et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2011), and teachers beliefs about information and communication technologies (Bas, 2017). A few studies explored metaphors for textbooks. For examples, McGrath (2002) focused on teachers in a book and included a task on metaphors for textbooks. McGrath (2006a) collected 200 images (metaphors and similes) from Brazilian teachers of English, examined their use of metaphoric language, and discussed teachers’ views of their English-language teaching textbooks, benefits for teachers and teacher educators of surfacing teachers’ beliefs, and varying degrees of textbook dependence. However, learners’ beliefs about textbooks, especially EAP textbooks, have not been fully examined and understood. Learners’ beliefs about EAP textbooks are significant for academic English teaching in terms of dealing with the need for a large, academically oriented vocabulary, working with difficult ideas, and combining reading and writing skills to learn and display content (Grabe and Zhang, 2013). Few studies discover underlying and subconscious conceptualization of learners by using metaphors in a EFL setting, particularly in China, academic English teaching is a hotly-debated topic and many universities offer academic English courses which are often considered not satisfactory and textbook is one of the main reasons contributing to this dissatisfaction (Ding and Jiang, 2015). Thus, it is timely and paramount to address quality and issues of EAP textbooks and examine underlying factors that affect academic English teaching from the perspective of teaching material evaluation by using metaphor analysis. The present study discusses metaphors used in relation to one EAP textbook by a sample of 147 first-year EFL graduate students from a public university in China, and it examines these students’ beliefs about the importance, quality and efficacy of the EAP textbook through metaphor analysis. Research questions are as follows:

1. What sort of metaphors do Chinese EFL graduate students generally use to describe their EAP textbook?

2. To what extent the EAP textbook is effective in meeting the needs of Chinese EFL graduate students according to learners’ viewpoint?

3. What instructional practices and research implications can we work with to provide academic English learning support?

3. Materials and methods

3.1. The context

This study was conducted at a public university of science and engineering in the city of Beijing, China. The total student enrollment of the university was approximately 16,000, with nearly 7,500 students in graduate programs and they met the standardized English language requirements for program entrance. The student participants of the study enrolled in a 16-week, two-credit academic course-- Academic English Reading and Writing. The course is a general academic English course for non-English major graduate students of the university, which is also a compulsory course for these students. According to the requirement of the curriculum and aims of syllabus, this course is designed to cultivate students’ comprehensive ability to use academic English, especially academic reading, writing and translation skills, so that students can effectively understand English in reading academic materials, use English to write academic papers and express English in future work and social interactions to adapt to social development and the need for international exchanges and cooperation. Besides, theses students have to pass College English Test Band 4 (CET-4) and College English Test Band 6 (CET-6). College English test is a competency test designed to measure students’ level of English proficiency in the skills. The test has been recognized by the society in China, and has become one of the standards for employment of college graduates by personnel departments at all levels, and has produced certain social benefits. The student participants of the study already passed the CET-4, but all of them, except 3 students, have not passed CET-6, so one of the near future goals of their English learning is to pass this test. In this EFL context, EAP textbooks are the main source of input and contact that students have with the language.

The EAP textbook evaluated in this study was Academic Encounters: Human Behavior-Reading and Writing (2017) by Bernard Seal. It was published by Cambridge University Press and Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. The textbook emphasizes reading skills by broadening vocabulary and focusing on grammatical structures that commonly occur in academic texts. Additionally there are opportunities for practice of academic writing skills including essay writing, text summaries, journal writing, and writing short answers. The book has four units broken down into two chapters, with a preview and three readings in each chapter. Each reading contains the pre- and post-reading activities. The pre-reading activities ask students to quickly find the main idea by skimming and surveying the text for headings, graphic materials, and terms that can provide content clues. After the readings, students are given various tasks including reading comprehension questions, drawing a graph, or performing a role-play. Some language tasks focus on vocabulary and the unique grammatical features of academic texts, which are critical to students’ future academic success. Students learn how to highlight a text, take notes, and practice test-taking skills as well as how to work with the organization and style expected in academic writing.

3.2. Participants

The participants of the study are a total of 147 first-year non-English major graduate students. Seventy-seven boys and 70 girls participated in the study. The participants were selected through “conventional sampling” technique so that the researcher could efficiently identify available subjects (Erdogan and Erdogan, 2013).

3.3. Data collection

A collection of student images for the EAP textbook elicited over a one-week period in early 2022 from graduate students. Students had used the book for one semester. They were supplied with a slip of paper on which the stem “the academic English textbook is … because …“was given and asked to complete this in writing with a metaphor which represented their attitudes to the textbook, and add a written explanation. Metaphors were used in collecting qualitative data to find out the textbook-related beliefs of the graduate students participating in the study. Students’ demographic information, including gender, major, and CET-4/CET-6 scores, was also collected.

3.4. Data analysis

This study follows a descriptive method to reveal students’ beliefs about the EAP textbook. A quantitative method was also used to calculate the frequency and percentage of metaphors. The textbook-related beliefs were analyzed through content analysis method. A total of 158 slips were returned, but the forms of 147 students were included to the study. Remaining 11 forms were not included due to the fact that they did not include a reason related to the metaphors (three), they included more than one metaphor (two), and they did not include any sources (two) or they were not logical (one), and some (three) simply contained statements of views (e.g., ‘The academic English textbook is important/useful/challenging to learners’) rather than images.

There are four stages in the process of analyzing and discussing metaphors: identification of metaphors, categorization of metaphors, category development, and providing validity and reliability. Reliability was established by using inter-analyst agreement. Two researchers analyzed the data, and then they came to an agreement comparing their analysis. Also, three different experts analyzed the categories of metaphors developed in this study to see whether they represent the related category or not. After that, the categorizations made by experts and categorizations made by researchers were compared. After data analysis, discussions of the findings were made accordingly.

4. Findings

Students participated in the study are found to produce a total of 147 metaphors about the beliefs of the EAP textbook. The metaphors appearing to be semantically related were grouped together.

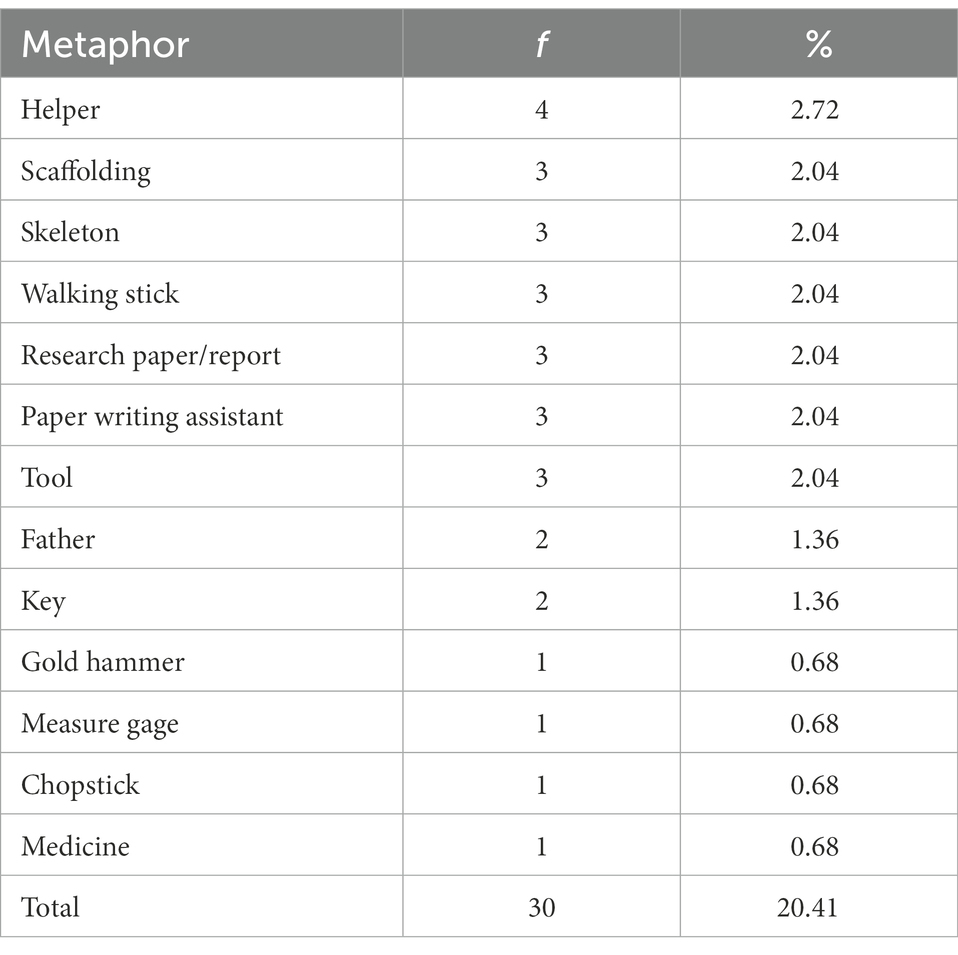

One of the conceptual categories about the textbook metaphor is “joy/enjoyment.” Images, such as “movie,” and “cake,” are included in this category. Table 1 presents the major metaphors of textbook developed under this conceptual category together with their frequency and percentage.

Table 1. Frequency and percentage of the textbook metaphor in the conceptual category of “joy/enjoyment.”

Table 1 shows that there are 40 metaphors under this conceptual category. Examples of the metaphors developed within this category and the reasons of developing these metaphors are as follows:

The textbook is a movie, because the design and the texts are interesting and I enjoy learning.

The textbook is a cake, because it is delicious and looks attractive.

The textbook is mineral water, because it is timely to quench my thirst and give me pleasures.

The textbook is a sports car, because I get excitement from it and it accelerates my learning speed.

Besides, images such as coffee, chocolate, and (beautiful) landscape were mentioned by students. We can see that these images express a predominantly positive view of the textbook, which seems to bring joys and stimulation to these students.

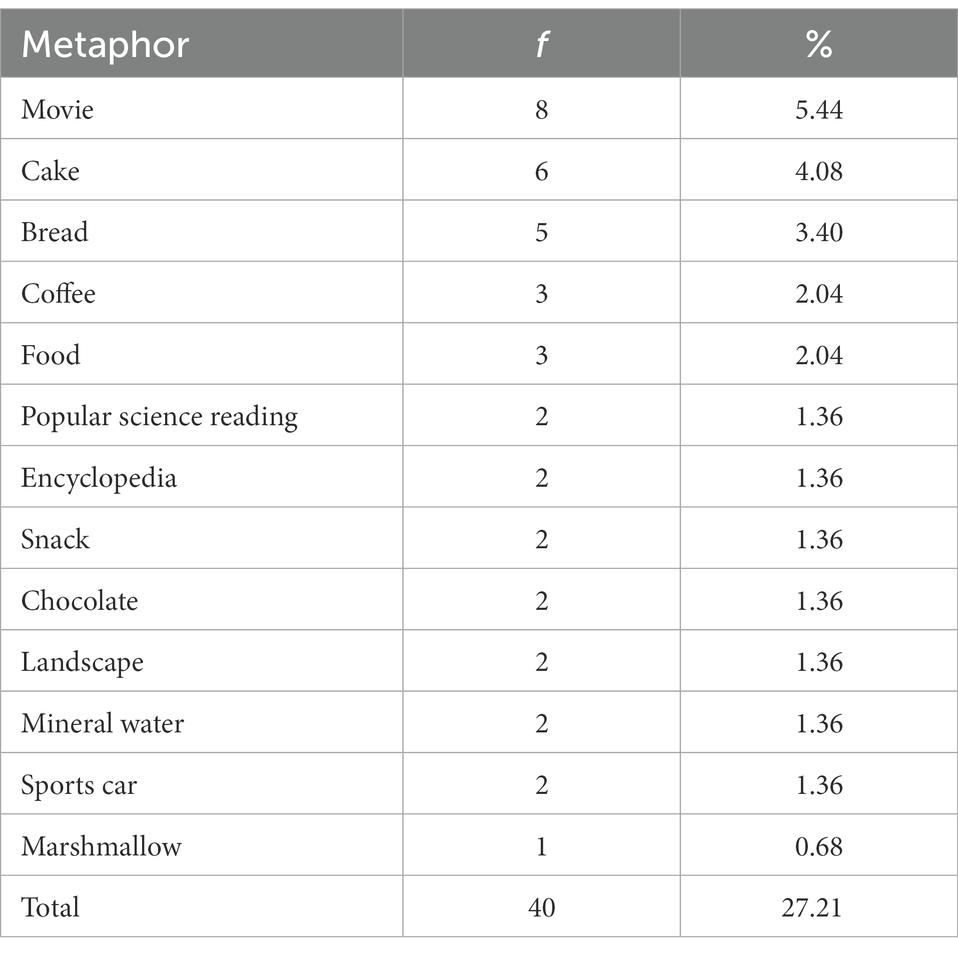

The other conceptual category related to textbook metaphor is that of “security.” Table 2 shows the major metaphors developed within this conceptual category.

Table 2. Frequency and percentage of the textbook metaphor in the conceptual category of “security.”

Findings given in the Table 2 show that there are 32 metaphors under the “security” concept. Examples of the metaphors developed related to this category and explanations for reasons of developing these metaphors are as follows:

The textbook is a lighthouse, because it is a navigational aid for me to arrive at the destination, and with its help, I know I would reach the end.

The textbook is a game instruction, because it teaches me how to play step by step, and I know what to expect. It seems that learning English is not so difficult.

The textbook is reinforcing (steel) bar, because the book gives me safety and helps to support my building of language.

The textbook is a traffic police, because I trust it, and I would make fewer detours with its help.

The textbook is martial arts secret, because from the book I get the power and I could learn the language secret to become the language master.

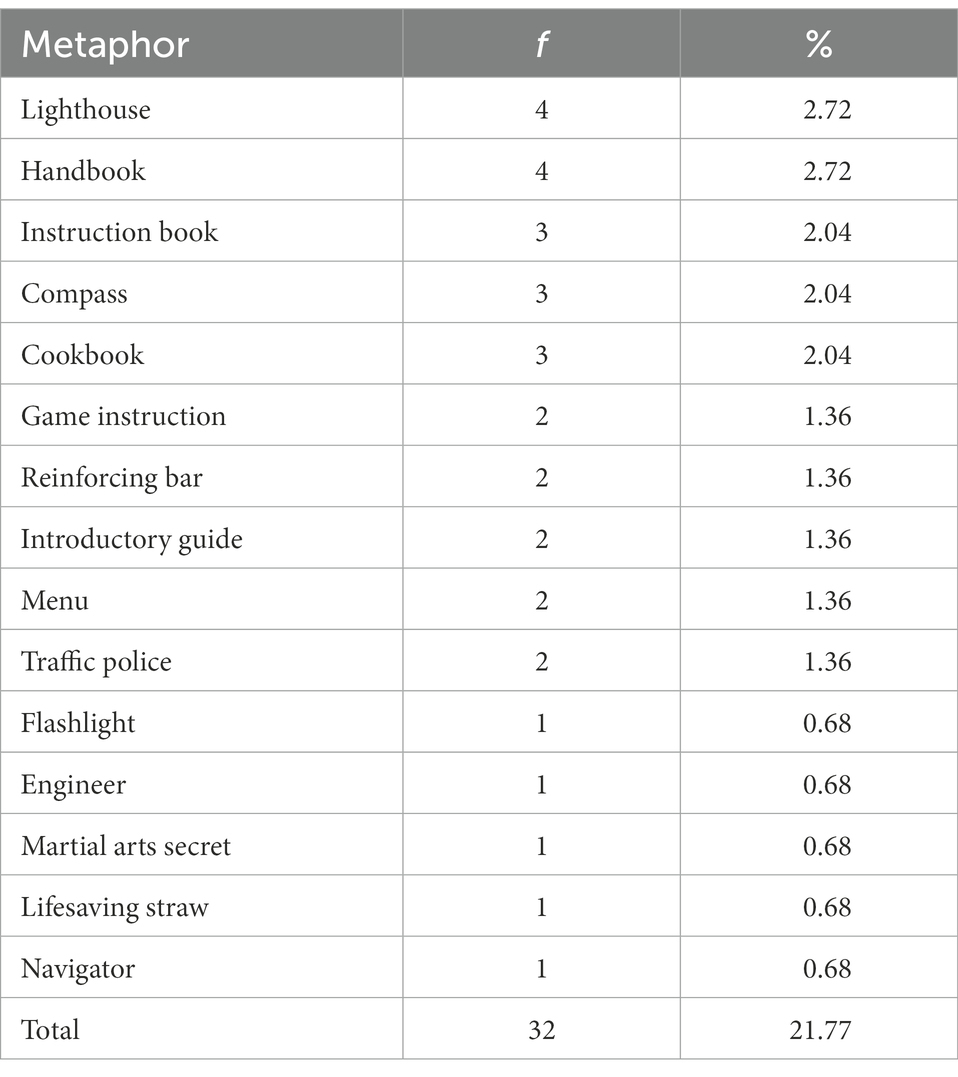

Another conceptual category in regard to the textbook metaphors developed by the participants is “grit.” Images that seem to reflect a view of the textbook as basis for persistence in academic English learning (e.g., “scaffolding” and “skeleton”) and the notion of emotional support (e.g., “father”) have been grouped together under “grit.” Table 3 gives the major metaphors of textbook developed related to this conceptual category.

As seen in Table 3, students developed a total of 30 metaphors under the conceptual category of “grit.” Examples of the metaphors in this category and the reasons of developing these metaphors are shown below.

The textbook is a skeleton, because it laid the foundation for me to grow and supported me to always make efforts.

The textbook is my father, because it supports me, gives me courage so that I can focus my attention and continue my effort.

The textbook is a walking stick, because I can continue and continue … with its help in this long way of learning even in the face of difficulties.

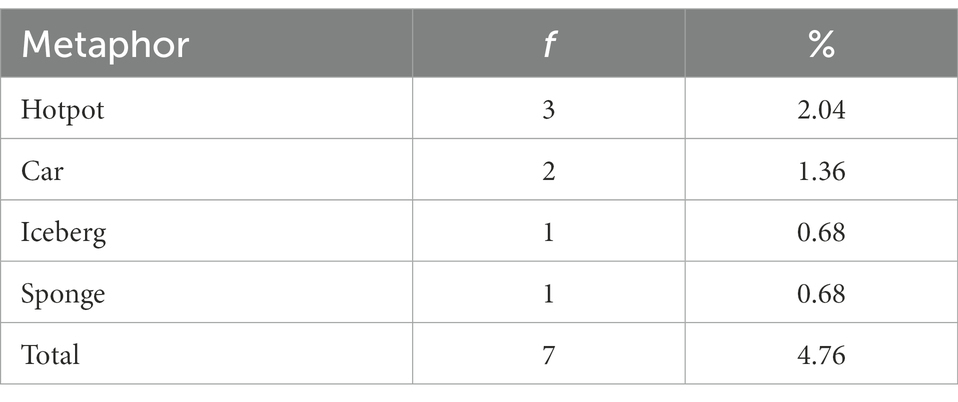

The following related conceptual category concerning the textbook metaphors is that of “curiosity.” This category indicates the students’ beliefs about their textbook as stimulating their curiosities. Table 4 shows the major metaphors developed in this category.

Table 4. Frequency and percentage of the textbook metaphor in the conceptual category of “curiosity.”

As can be seen in Table 4, students expressed a total of 7 metaphors under this conceptual category. Examples of the metaphors and the reasons of developing these metaphors are noted below.

The textbook is hotpot (Chinese popular food), because it contains many different things. It makes me always want to explore different things.

The textbook is a car, because it gives me different rides, and it meets my desire to see different sceneries and get to different destinations.

The following categories are relatively negative views of students toward the textbook. One of the conceptual categories is “old-fashioned.” Students developed 14 metaphors under this conceptual category (fossil 4, old man 4, Youth Digest 2, dictionary 2, spicy strip 1, law book 1). Examples of the metaphors and explanations for the reasons of developing these metaphors are as follows:

The textbook is fossil, because it is out of fashion and the content is not new and creative enough.

The textbook is a serious old man, because the book is old-fashioned and the texts and pictures are out of date.

The textbook is Youth Digest (a journal once popular among young people in China for entertainment and general reading), because it looks as usual, and there is no innovation.

The textbook is spicy gluten (popular snack food for under 25s in China), because it is just what I thought and does not provide any new things.

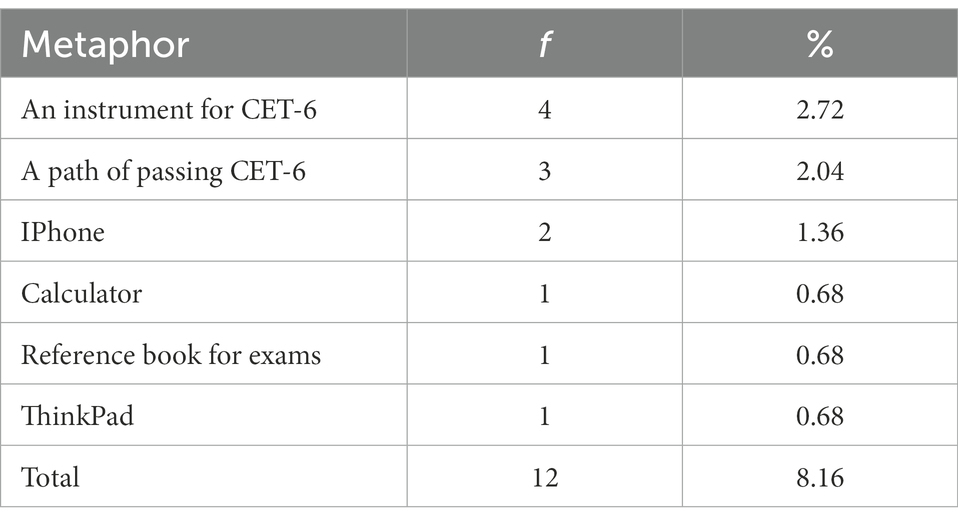

The other conceptual category developed by the participants is the category of “exam-orientated.” Students expressed a total of 12 metaphors under this conceptual category. These students mostly considered the textbook as exam-orientated rather than practice-oriented. This category indicates students’ beliefs about their textbook as being just a tool to pass exams. Table 5 shows the major metaphors of textbook developed in this category.

Table 5. Frequency and percentage of the textbook metaphor in the conceptual category of “exam-orientated.”

Examples of the metaphors and the reasons of developing these metaphors are noted below.

The textbook is an instrument for CET-6, because it is just useful for passing exams. I think it should be a masterwork.

The textbook is a calculator, because it is used for exams, and if it were not for exams, I would not use it.

The textbook is an IPhone, because I use it to search and look for vocabulary and prepare for tests.

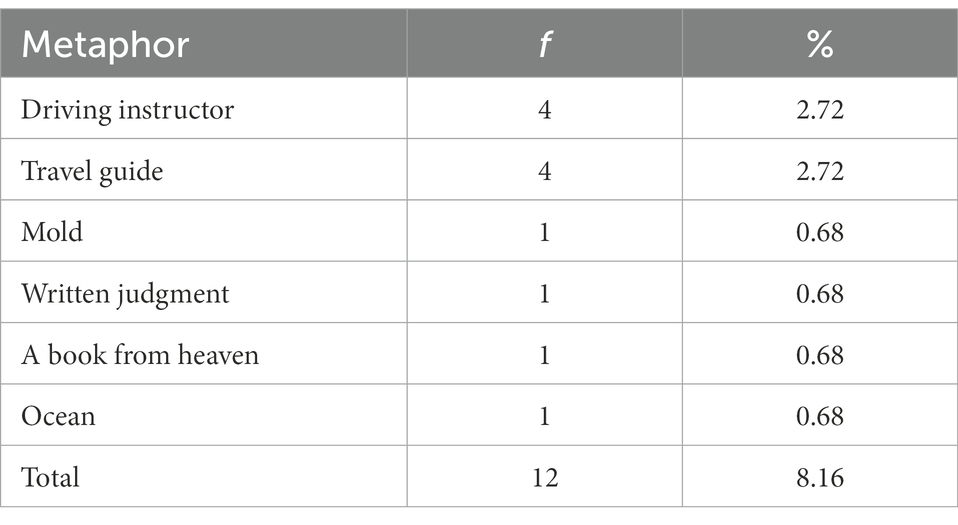

The last conceptual category concerning the textbook metaphors is that of “teacher-directed.” As can be seen in Table 6, students expressed a total of 12 metaphors under this conceptual category.

Table 6. Frequency and percentage of the textbook metaphor in the conceptual category of “teacher-directed.”

These students mostly relate the textbook with lack of self-directed learning training. Examples of the metaphors and their explanations are as follows:

The textbook is a driving instructor, because I just follow the instruction, and without it I cannot drive on my own.

The textbook is a written judgment, because the teacher has the authority, and we don’t know how to defend by ourselves.

The textbook is a book from heaven, because I cannot learn by myself and have to depend on my teacher.

The textbook is an ocean, because it looks mysterious and without teachers’ help I cannot find a way.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study has been to draw attention to the value of surfacing learners’ beliefs and attitudes to the EAP textbook, and the potential value of metaphors for this purpose. According to Mcgrath (2006a), the image collection can serve both short-term pedagogic and longer-term research purposes. Pedagogic decisions can then be based on this information. Thus, in the classroom setting, the expression of learners’ different views may prompt discussion of the source of these views and their possible effects on learning. Implications for how to appropriately design and use textbooks and desired modifications in teacher practices may then emerge.

The metaphors produced by participants are grouped under 7 subcategories. The metaphors produced by approximately 74 percent of the students were grouped in the first four categories, including joy, security, grit, and curiosity. The findings indicate that most students identified the value of the textbook and they mostly conceptualized the textbook as being interesting, helpful, instructive, stimulating/motivating and supportive for their academic English learning. Students considered the textbook as “movie,” “coffee,” “lighthouse,” “game instruction,” “father,” and “martial arts secret” to show their recognition of the good quality of the book or willing acceptance of the role played by the textbook in their academic English learning process. The EAP textbook becomes source of motivator, assistance and inspiration for students to fulfill their academic objectives. It seems that the EAP textbook is effective in meeting the needs of these students according to learners’ viewpoint. For examples, they mentioned the textbook provides “pleasures” and “excitement,” and “the design and the texts are interesting” and they “enjoy learning.” It indicates that students mostly focus on design and contents of the textbook that are interesting and attractive, and students are internally motivated. Horwitz (2010) similarly stated students’ beliefs affected attitudes, motivation and learning strategies in the foreign language class. Joy, as one of the factors of positive emotions, creates the urge to learn, and promotes creativity. According to MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012), positive emotions could broaden learners’ attention and thinking, counter the effects of negative emotions, promote resilience to stressful events, build personal resources, and lead toward greater well being. Deuri (2012) argued that a good English textbook should have an adequate subject matter where psychological needs and students’ interests could be met. The EAP textbook in the current study is effective in meeting the psychological needs of students.

Besides, as described by Graves (2000), textbooks having a kind of road map of the course could provide students a sense of security because they know what to expect and what is expected of them. For example, one student mentioned, “the textbook is a cookbook, because I know I can make a delicious meal by following it step by step.” The textbook is helpful “to arrive at the destination,” and gives students “safety” and “power.” Marginson et al. (2010) defined security as “maintenance of a stable capacity for self-determining human agency” (p. 60). Sawir et al. (2012) discussed students’ security and believed security was about the exercise of freedoms and the capacity to reach understanding so as to collaborate with others. Security encompasses capacity to act and students were envisioned as active self-determining agents, albeit subject to the external environment. As is known, academic English is associated with complex and abstract ideas, or high cognitive demands and students may meet challenges and difficulties in their learning process (Ranney, 2012). Students’ security is associated with their competence in and confidence with the use of the English language. EAP textbooks in this EFL context as major reference materials or main source of input and contact that students have with the language enable students to understand, cooperate, and exchange with peers and teachers and to meet requirements of the class. These textbooks may provide security for students to achieve their academic goals.

The textbook also supports students “to always make effort,” gives students “courage,” and helps students to continue “in this long way of learning even in the face of difficulties.” Gritty students are more likely to invest energy and make efforts over a long period of time even when encountering challenges or failures (Teimouri et al., 2020). Grit encompasses two sub-constructs, consistency of interest and perseverance of effort (Duckworth et al., 2007; Duckworth and Quinn, 2009; Robertson-Kraft and Duckworth, 2014). Grit is a trait in students with diligence and endurance to keep working for a goal in spite of various setbacks (Duckworth et al., 2007). It seems that the EAP textbook in this study does meet the needs of students, supports and provides encouragement for students to persist in face of the difficulties and challenges in academic English learning, and it is designed to let students know that if they persist and set goals, they have the capacity to reach these goals. Academic English cannot be easily acquired and requires considerable time and effort to master. In fact, the skill of academic English is one of the most difficult language skills to be acquired by the students, and it was already explained by Cummins (2000), who stated English language learners required substantially longer to acquire academic language than basic conversational fluency in English. The academic English textbook can be designed with consistent learning goals and activities to let students know what they may lack in language-learning ability could be made up for with focus, hard work, and persistence. The textbook could design creative, teacher- or student-led activities relating to the challenges students face and through these activities students could learn how to face the challenges and how to be gritty. Grits are found associated with motivation (Teimouri et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021), engagement and joy (Wei et al., 2019, 2020), so the textbook could also teach students different learning strategies to motivate students and engage students actively and joyfully in class tasks, so that students could persist in face of difficulties and challenges. As argued by Lodhi et al. (2019), students could benefit from textbooks to fix their motivational strategies.

Curiosity is defined as a need, thirst or desire for knowledge, and it is a control to motivation (Berlyne, 1998). The students with high curiosity will have great desire to question the gaps in the learning, seek exploratory information and knowledge, answer particular questions, and have good attention in learning (Dweck, 2006). Kashdan (2009) also identifies students with high curiosity toward learning are: (1) interested in new things and possessing an open and receptive attitude toward whatever is the target of attention, (2) devote more attention to an activity, remember information better and more likely to persist on tasks until goals are met, (3) have the ability to effectively cope with or make sense of the novelty, ambiguity and uncertainty being confronted during explorations. Some participants in this study indicated that they had the interest and desire to explore new knowledge. The textbook could raise students’ attention to the inconsistency between their new and previous knowledge. For examples, students mentioned that the textbook made them “always want to explore different things,” or meet their desires to “see different sceneries” and “get to different destinations.” Textbook promoting curiosity drives and motivates students to have a deeper level of understanding, fill gaps in knowledge, and solve intellectual problems. The curiosity aroused in situations when learners have no immediate linguistic access to their second language knowledge or they find that there are discrepancies between their fully known first language system and their partly known second language system (Mahmoodzadeh and Khajavy, 2019). Thus, textbook could be designed with the “i + ” concept (a concept proposed by Stephen D. Krashen in his Input Hypothesis, that is, second language learners acquire languages by understanding input that is a little beyond their current level of competence), that is, the level of the textbook could be a little beyond the current level of students. Then, students could be more actively engaged in learning process, more enthusiastic with the tasks given by teachers.

While the first four categories express a positive attitude toward the textbook, the final three categories, including old-fashioned, exam-orientated and teacher-directed, bring together a range of disaffection or negative reactions to the textbook. We have to admit students with different language proficiencies may have different beliefs and attitudes toward the textbook. Approximately 26 percent of the students conceptualize the textbook as being “out of date,” “not new and creative” or “just useful for passing exams.” Through the metaphors used by these students, they expressed their frustration with the limitations imposed by the textbook, or perhaps they felt the requirement to use a specific textbook was unsuitable. It seems that as for these students, the EAP textbook can be further modified to be effectively meet the needs of them. The inappropriateness of the textbook may raise doubts about the process used to select this textbook or the way in which the textbook is used. Here we have the fairly predictable “fossil,” and the students who supplied “old man” and “calculator” explained that the images expressed their feelings with the aridity of the textbook they used. They believed that the textbook failed to provide relevant and effective linguistic skills, the content was not practical, or connected to students’ real life, and it did not cater to learner’s educational requirements. These students articulated dissatisfaction about the effectiveness and efficiency of the EAP textbook. From images provided by these students we can learn that they had awareness that the textbook should be creative, practical and student-centered, but the currently used textbook was not designed or appropriately used in this way.

Some students in this study believe the textbook is merely useful for them to pass exams or is just a reference book to look up information tested. They had a sense of utilitarian about the EAP textbook or language learning itself from a negative perspective. Due to the examination-oriented learning context in Asia (Kwok, 2004), most learners learn the target language for concrete purposes such as passing examinations or enhancing the possibility of finding a job (Liu and Huang, 2011; Yu and Geng, 2019). In this EFL context, the textbook, as the main source of input and access that students have with the language, is considered by these students as an exam-oriented instrument since English courses and CET-4/ CET-6 are required for college students in China. It seems that some students did not learn the language in order to use it but merely to take exams, and even after students achieved CET-4/CET-6 onwards, they could not cope with the demands of reading and writing in English in the academic context. This is a matter of textbook use. Besides, according to Lee and Wong (2000), there were wash back effects of the examination on teaching, which perhaps made teachers focus only on areas that would be tested. This evaluation oriented language-learning conception should be shifted. As one student mentioned, “the textbook should be a masterwork” instead of “just useful for passing exams.” The course could be designed to develop students’ multi-competence including comprehensive language ability, humanistic quality, critical thinking and independent learning ability. The materials selected by teachers and the way textbooks are used could contribute much in the development/improvement of these different competences.

Finally, some students reported, “the teacher has the authority” and “I cannot learn by myself and have to depend on my teacher.” Students developed the awareness that the textbook was teacher-directed and it should be modified to promote their independent learning skills. As one student mentioned, “the textbook is a driving instructor, because I just follow the instruction, and without it I cannot drive on my own.” The autonomy value of a textbook needs to be recognized so that students could learn and try out the exercises in the textbook on their own, even without the instruction from their teachers (Thang et al., 2012). Independent learning skills are vital for academic language and literacy development to meet the demands inside and outside of classroom contexts (Zwiers and Crawford, 2011; Ranney, 2012). Students could develop the ability of independent learning and be trained to use self-directed strategies in their learning process by appropriate using textbooks. Both teachers and learners need the independence and autonomy to take responsibility for their own teaching and learning (Koad and Waluyo, 2021), and materials writers should modify their textbooks accordingly (Harwood, 2005).

On the whole, there are some values of the EAP textbook, which effectively meet the needs of students in this study, and at the same time it is inevitably needed to make appropriate and cogent modifications in the syllabus and materials being taught. Some instructional practices we can work with to provide academic English learning support are as follows.

Firstly, it is suggested to include learner’ self-directed learning strategies as well as instructional kits and teacher guides related to academic English textbooks to help teachers in their effective teaching and expedite students’ learning process. Although some textbooks cannot fully achieve standard, we should not abandon these textbooks, rather, we should strive to improve the quality of textbooks being produced (Harwood, 2005). The importance of textbooks is especially increased in case of language textbooks as teachers and students lack relevant and authentic material. It is strongly recommended to integrate authentic, innovative, interest grabbing and skill oriented materials in academic English textbooks. In the process of cultivating students’ academic English ability, the EAP materials need to present language that typifies which is commonly encountered by students in the academy, and materials developers need to attend to key features of that language (Wood and Appel, 2014). It is also necessary to promote students’ cross-cultural communication ability to adapt to the internationalization of higher education. Other assistance such as modern educational technology could also be combined and used in textbooks in the process of academic English teaching (Charles, 2012).

Besides, textbooks should not be treated as the only source materials for teaching and learning to avoid over-dependence on them. The over reliance on textbooks can affect not only students but also teachers in their initiative to effectively use and devise materials to suit the needs of students (Thang et al., 2012). It is suggested that teachers flexibly use the EAP textbooks, and provide opportunities for students to use academic English as it is used in professional and academic communities (Dicerbo et al., 2014). Teachers could be more creative and judicious handling the course materials, and in the selection of passages and exercises from the textbook for class use, and not follow blindly what is prescribed (Thang et al., 2012). Teachers could be trained to appropriately use textbooks, comprehensively learn about students’ language level and learning ability, and consider the differences in learners’ beliefs and satisfy students’ needs by addressing their motives behind academic English learning. Various teaching methods, dynamic teaching content, and supplementary teaching materials recommended to students could compensate for the shortcomings of the textbook (Sajjadi, 2011). For instance, scaffoldings and a supportive and comprehensible learning environment provided by teachers are very motivating for English language learners (Carrier, 2016), and various teaching materials and more adaptive teaching practices can be used so that each student can easily find their own relevance and take part in the learning process (Sajjadi, 2011). Teachers also need to break away from their conventional mode of delivering course materials, and embrace innovative approaches that will enable them to create an engaging, stimulating and enriching learning environment for their students (Thang et al., 2012). Based on the findings, it can be suggested that learners also should be aware of their own ideas and understand the origins of these ideas. Thus, both EFL learners and teachers in input-poor environments could share the responsibility for creating positive beliefs regarding EAP textbooks and academic English learning.

6. Conclusion and suggestions for future research

The importance of EAP textbooks in formal educational settings has been widely recognized. The nature and strength of many of the learner images about the EAP textbook is a striking finding. The images indicate how valuable and significant the EAP textbook is for EFL graduate students in a Chinese university setting and the strength of negative feelings that the textbook can inspire, feelings that may stem from the inherent unsuitability of the book itself or be a product of the way in which it is used by teachers. It is possible to argue that those students with this awareness have the competency of making self-evaluation or can understand that their academic English learning may be improved if they appropriately use EAP textbooks. The materials selection, usage, and evaluation should meet the needs of students and cater to students’ linguistic, affective and educational requirements. Some research implications that we can provide academic English learning support are as follows.

According to Mcgrath (2006b), if this happens to be a teacher’s first attempt to understand what their learners’ feel, to listen to learners’ unique voices, this may trigger a new phase in self-development. Eliciting metaphors for textbooks may prove to be just a beginning. This study focuses on students’ perspective, and teachers’ views on the usefulness of textbooks may differ from those of students. Future research can explore teachers’ views and it will be interesting to explore what happens in a university context where teachers do compare metaphors with their students. Besides, follow-up interviews could be carried out in future studies to complement personal analogical statements (Jin and Cortazzi, 2011) to increase the trustworthiness of the metaphor analysis, so that we can further understand whether entailments are positive or negative. Additionally, as Barcelos (2003) and Hart (2009) suggested, metaphor analysis procedures applied to beliefs about second/foreign language teaching and learning need to encompass culturally/contextually-appropriate interaction between different stakeholders such as teacher trainers, policymakers and administrators to further promote academic English teaching and learning in the future studies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by China University of Petroleum, Beijing. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Azizifar, A., Koosha, M., and Lotfi, A. R. (2010). An analytical evaluation of locally produced Iranian high school ELT textbooks from 1970 to the present. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 3, 36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.010

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2003). “Researching beliefs about SLA: a critical review,” in Beliefs About SLA: New Research Approaches. eds. P. Kalaja and A. M. F. Barcelos (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher), 7–33.

Bas, G. (2017). Perceptions of teachers about information and communication technologies (ICT): a study of metaphor analysis. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 8, 319–337. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/6203

Boyle, G. J., Helmes, E., Matthews, G., and Izard, C. E. (2015). “Measures of affect dimensions,” in Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs, Vol. 8 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 190–224.

Cai, J. (2011). College English textbooks to cope with a transition: principles and problems. Foreign Lang. Res. 5, 5–10. doi: 10.13978/j.cnki.wyyj.2011.05.017

Carrier, K. A. (2016). Key issues for teaching English language learners 1 in academic classrooms. Middle Sch. J. 37, 4–9. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2005.11461519

Charles, M. (2012). ‘Proper vocabulary and juicy collocations’: EAP students evaluate do-it-yourself corpus-building. Engl. Specif. Purp. 31, 93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2011.12.003

Chen, X., Lake, J., and Padilla, A. (2021). Grit and motivation for learning English among Japanese university students. System 96, 102411–102434. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102411

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

De Guerrero, M. C. M., and Villamil, O. S. (2002). Metaphorical conceptualizations of ESL teaching and learning. Lang. Teach. Res. 6, 95–120. doi: 10.1191/1362168802lr101oa

Deuri, C. (2012). An evaluative study of text book in English at higher secondary level. Int. J. Sci. Environ. Technol. 1, 24–28.

Dicerbo, P. A., Anstrom, K. A., Baker, L. L., and Rivera, C. (2014). A review of the literature on teaching academic English to English language learners. Rev. Educ. Res. 84, 446–482. doi: 10.3102/0034654314532695

Dincer, A. (2017). EFL learners' beliefs about speaking English and being a good speaker: a metaphor analysis. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 5, 104–112. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2017.050113

Ding, Y., and Jiang, X. (2015). Publication and development of general academic English textbooks. Sci. Technol. Publication 12, 100–103.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., and Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 1087–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., and Quinn, D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (grit-S). J. Pers. Assess. 91, 166–174. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634290

Erdogan, T., and Erdogan, O. (2013). A metaphor analysis of the fifth grade students’ perceptions about writing. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 22, 347–355. doi: 10.1007/s40299-012-0014-4

Grabe, W., and Zhang, C. (2013). Reading and writing together: a critical component of English for academic purposes teaching and learning. TESOL J. 4, 9–24. doi: 10.1002/tesj.65

Han, C. (2011). Reading Chinese online entertainment news: metaphor and language play. J. Pragmat. 43, 3473–3488. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2011.07.013

Harbi, A. A. M. A. (2017). Evaluation study for secondary stage EFL textbook: EFL teachers’ perspectives. Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 26–39. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n3p26

Hart, G. A. (2009). Composing metaphors: metaphors for writing in the composition classroom. Dissertations & Theses-Gradworks. Athens: Ohio University (Ohio University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing).

Harwood, N. (2005). What do we want EAP teaching materials for? J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 4, 149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2004.07.008

Horwitz, E. K. (2010). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Lang. Ann. 18, 333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.1985.tb01811.x

Jamshidi, T., and Soori, A. (2013). Textbook evaluation for the students of speech therapy. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 4, 159–164. doi: 10.7575/aiac.alls.v.4n.2p.159

Jin, L., and Cortazzi, M. (2011). “More than a journey: learning in the metaphors of Chinese students and teachers,” in Researching Chinese Learners: Skills, Perceptions and Intercultural Adaptations. eds. L. Jin and M. Cortazzi (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan), 67–92.

Jou, Y. (2017). Hidden challenges of tasks in an EAP writing textbook: EAL graduate students’ perceptions and textbook authors’ responses. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 30, 13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2017.10.001

Kashdan, T. (2009). Curious? Discover the missing ingredient to a fulfilling life. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Koad, P., and Waluyo, B. (2021). What makes more and less proficient EFL learners? Learner’s beliefs, learning strategies and autonomy. Asian EFL J. 25, 48–77.

Kwok, P. (2004). Examination-oriented knowledge and value transformation in east Asian cram schools. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 5, 64–75. doi: 10.1007/BF03026280

Lee, K. S., and Wong, F. F. (2000). Washback effects of a new test on teaching: a Malaysian perspective. STETS Lang. Commun. Rev. 2, 11–18.

Liu, M., and Huang, W. (2011). An exploration of foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation. Educ. Res. Int. 2011, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2011/493167

Lodhi, M. A., Farman, H., Ullah, I., Gul, A., and Saleem, S. (2019). Evaluation of English textbook of intermediate class from students’ perspectives. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 26–36. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n3p26

Lu, M., and Liu, Z. (2013). Metaphor analysis of Chinese students’ beliefs about English learning. Foreign Lang. Teach. 34, 39–42.

Macintyre, P., and Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2, 193–213. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

Mahmoodzadeh, M., and Khajavy, G. H. (2019). Towards conceptualizing language learning curiosity in SLA: an empirical study. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 48, 333–351. doi: 10.1007/s10936-018-9606-3

Marginson, S., Nyland, C., Sawir, E., and Forbes-Mewett, H. (2010). International Student Security. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McGrath, I. (2002). Materials Evaluation and Design for Language Teaching. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

McGrath, I. (2006a). Using insights from teachers’ metaphors. J. Educ. Teach. 32, 303–317. doi: 10.1080/02607470600782443

Mcgrath, I. (2006b). Teachers’ and learners’ images for coursebooks. ELT J. English Lang. Teach. J. 60, 171–180. doi: 10.1093/elt/cci104

Mohammadi, M., and Abdi, H. (2014). Textbook evaluation: a case study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 98, 1148–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.528

Ranney, S. (2012). Defining and teaching academic language: developments in K-12 ESL. Lang. Linguist. Compass 6, 560–574. doi: 10.1002/lnc3.354

Robertson-Kraft, C., and Duckworth, A. L. (2014). True grit: trait-level perseverance and passion for long-term goals predicts effectiveness and retention among novice teachers. Teach. Coll. Rec. 116, 1–27. doi: 10.1177/016146811411600306

Saban, A., Koc Beker, B. N., and Saban, A. (2006). An investigation of the concept of teacher among prospective teachers through metaphor analysis. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 6, 461–522.

Saban, A., Koçbeker, B. N., and Saban, A. (2007). Prospective teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning revealed through metaphor analysis. Learn. Instr. 17, 123–139. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.01.003

Sajjadi, M. (2011). Evaluating the SAMT English textbook for BSc students of physics. J. Appl. Linguist. 4, 175–195.

Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Forbes-Mewett, H., Nyland, C., and Ramia, G. (2012). International student security and English language proficiency. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 16, 434–454. doi: 10.1177/1028315311435418

Shi, L., and Liu, Z. (2012). Metaphor analysis of the beliefs of Chinese college students, middle school students and primary students. J. Xian Univ. Foreign Stud. 20, 67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.07.012

Teimouri, Y., Plonsky, Y., and Tabandeh, F. (2020). L2 grit: passion and perseverance for second-language learning. Lang. Teach. Res. 1, 1–48. doi: 10.1177/1362168820921895

Thang, S. M., Wong, F. F., Noor, N. M., Mustaffa, R., Mahmud, N., and Ismail, K. (2012). Using a blended approach to teach English for academic purposes: Malaysian students' perceptions of redesigned course materials. Int. J. Pedagog. Learn. 7, 142–153. doi: 10.5172/ijpl.2012.7.2.142

Wan, W., Low, G. D., and Li, M. (2011). From students’ and teachers’ perspectives: metaphor analysis of beliefs about EFL teachers’ roles. System 39, 403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.07.012

Wei, H., Gao, K., and Wang, W. (2019). Understanding the relationship between grit and foreign language performance among middle school students: the roles of foreign language enjoyment and classroom environment. Front. Psychol. 10, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01508

Wei, R., Liu, H., and Wang, S. (2020). Exploring L2 grit in the Chinese EFL context. System 93, 102295–102299. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102295

Wood, D. C., and Appel, R. (2014). Multiword constructions in first year business and engineering university textbooks and EAP textbooks. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 15, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2014.03.002

Yayci, L. (2017). University students’ perception of being an international student: a metaphor analysis study. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 3, 379–403. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1015774

Yu, J., and Geng, J. (2019). Continuity and change in Chinese English learners’ motivations across different contexts and schooling levels. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 1, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40299-019-00473-1

Zheng, H., and Song, W. (2010). Metaphor analysis in the educational discourse: a critical review. US-China Foreign Lang. 8, 42–49.

Keywords: metaphor analysis, textbook evaluation, students’ beliefs, EFL context, EAP

Citation: Shi H (2022) A metaphor analysis of EFL graduate students’ beliefs about an EAP textbook. Front. Educ. 7:972996. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.972996

Edited by:

Çelen Dimililer, Near East University, CyprusReviewed by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaBalwant Singh, Partap College of Education, India

Copyright © 2022 Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Shi, aHpzMDAzMkBhdWJ1cm4uZWR1

Hong Shi

Hong Shi