- Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Education, Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia

Conceptions of assessment are critical to implementing new assessment policies since they influence how teachers understand, interpret, and implement new policies. This small-scale qualitative study investigated 12 secondary school English language teachers’ views about the current secondary school assessment policy and their conceptions of assessment. The data were collected through in-depth interviews in Maputo, Mozambique. The findings suggest that most participants are unfamiliar with the current assessment policy. The participants conceive of assessment as extrinsically motivating students, improving teaching and learning, holding students accountable, reporting, compliance, and irrelevant. Some participants reported pure conceptions of assessment (either improvement or student accountability), while others reported mixed conceptions (either mixed school and student accountability and improvement and mixed student accountability and irrelevant). The emerging profiles of teachers’ conceptions of assessment are expected to provide a starting point for a discussion about designing effective professional development programs in assessment literacy in Mozambique.

Introduction

Mozambique has undergone several school reforms since it became independent from Portugal in 1975. The first comprehensive school reform occurred in 1983 when the government laid out the national school system, intended to replace the colonial education system deemed inappropriate to the newly independent Mozambique (INDE/MINED, 2003). In 1995, the government adopted the national education policy, which complemented and operationalized the national school system.

The post-independence curriculum was irrelevant, prescriptive, and rigid, leaving little room for adjustments necessary to meet the needs of local communities (INDE/MINED, 2003). Therefore, the country underwent a second comprehensive school reform in 2004 and 2008, targeting elementary and secondary education, respectively. In the realm of teaching English as a foreign language, the school reforms brought several innovations to public schools, such as the introduction of the English language in elementary education, the adoption of the communicative language teaching approach, and the adoption of an assessment policy that emphasizes formative assessment rather than summative assessment (INDE/MINED, 2003; INDE/MINED, 2007).

The focus on formative assessment represented a significant shift in educational assessment in Mozambique since assessments tended to fulfill mostly summative functions. Although the policy emphasizes formative assessment, the use of internal and external summative assessments has been maintained (MINEDH, 2019), suggesting that teachers have to play a dual role—that of “facilitator and monitor of language development and that of assessor and judge of language performance as achievement” (Rea-Dickins, 2004, p. 253). Research in other contexts shows that teachers struggle to establish a synergy between summative and formative assessment assessments, especially in contexts where the two forms of assessments are disintegrated (Bonner, 2016). Brown and Remesal (2017) emphasized the need to reduce the dominance of high-stakes assessments so that formative assessment initiatives can come to fruition.

Besides reducing the dominance of tests, the successful integration of formative assessment into the existing summative assessment framework may require helping teachers develop new skills and knowledge about assessment (Muianga, 2022) and positive conceptions of assessment. Positive conceptions of assessment (e.g., assessment improves instruction) are associated with beneficial assessment practices, while negative conceptions (e.g., assessment is bad for students) are linked to teachers’ resistance to new assessment policies (Deneen and Boud, 2014; Deneen and Brown, 2016). Conceptions of assessment mediate how teachers understand, interpret, and implement assessment knowledge (Fives and Buehl, 2012; Barnes et al., 2015, 2017). Thus, the effectiveness of professional development programs and the successful implementation of innovative assessment policies rely on teachers’ conceptions of assessment (Brown, 2008). Following the assessment policy change in Mozambique more than a decade ago, it becomes critical to explore teachers’ conceptions of assessment.

There is extensive literature on teachers’ conceptions of assessment. However, the Mozambican assessment context remains under-researched. Additionally, few of the studies on conceptions of assessment were conducted in the field of foreign or second language teaching. This small-scale qualitative study aims to supplement the existing body of research and expand knowledge in the field by exploring the conceptions of assessment held by secondary school teachers of English in Mozambique. The emerging profiles of teachers’ conceptions of assessment are expected to provide a starting point for a discussion about designing effective professional development programs in assessment literacy in Mozambique.

Literature review

Teachers’ conceptions of assessment

Research suggests that teachers’ conceptions of assessment vary depending on the assessment context (Barnes et al., 2015; Bonner, 2016). Brown et al. (2019) divided assessment contexts into low-stakes (e.g., New Zealand, Queensland, Cyprus, and Catalonia) and high-stakes (e.g., Hong Kong, China, Iran, Egypt, India, and Ecuador). Low-stakes assessment contexts require students to take fewer national examinations, and all assessment decisions are usually made locally. On the other hand, high-stakes assessment contexts use national examinations to make decisions about students (e.g., progression). Teachers in low-stakes assessment contexts are inclined to view assessment as serving improvement and school accountability. On the other hand, teachers in high-stakes assessment contexts are more likely to conceive of assessment as serving student and school accountability and associate student accountability with improvement (Brown et al., 2011a; Gebril and Brown, 2014).

Low-stakes assessment contexts

Brown (2004) examined secondary school teachers’ conceptions of assessment in New Zealand. He found that teachers believed that assessment improves teaching and learning. The participants also accepted the notion that assessment is used to hold schools accountable. However, they rejected the idea that assessment is used to hold students accountable and that assessment is irrelevant. These findings were expected since, in New Zealand, schools have the autonomy to make assessment decisions, and teachers use assessment to track students’ progress toward the standards.

These findings are remarkably similar to Brown et al. (2011b) in Australia. The authors explored primary and secondary school teachers’ conceptions of assessment in Queensland. The participants agreed to the view that assessment improves learning and teaching. Nevertheless, primary school teachers were more inclined to believe that assessment improves instruction than secondary school teachers. The participants who believed that assessment improves teaching and learning were more likely to agree that assessment holds schools accountable. The difference between primary and secondary school teachers was partially attributed to policy differences between the two educational levels. When the study was conducted, secondary school students were expected to take externally monitored school-based assessments.

Segers and Tillema (2011) explored Dutch teachers’ conceptions of assessment. They found that teachers believe that assessment is used to (1) inform student performance and learning; (2) hold school accountable; (3) is inaccurate and unreliable and contains measurement error; and (4) is the basis for making instructional decisions and it measures high order thinking skills. These findings partially echo Brown’s (2004) findings in New Zealand. However, the teachers in Segers and Tillema’s (2011) research did not distinguish between formative and summative assessment functions. The first conception of assessment (inform student performance and learning) includes improvement and student accountability conceptions. This was attributed to the fact that Dutch secondary school teachers’ assessment practices include both formative and summative assessments. Therefore, they do not view the two forms of assessment as separate.

Unlike the studies reviewed above, Yates and Johnston’s (2018) research involving high school teachers in New Zealand found that the participants’ conceptions of assessment were similar to those of teachers in high-stakes assessment contexts and different from Brown’s (2004) findings. Yates and Johnston (2018) found a correlation between student accountability and improvement conception. This was expected since the primary and high school assessment policies differed significantly. The high school assessment policy required teachers to engage in school-based assessment for qualifications. These findings substantiate the claim that teachers’ beliefs about assessment tend to align with the assessment policy and practices endorsed in their work context (Brown and Michaelides, 2011; Fulmer et al., 2015).

High-stakes assessment contexts

Brown et al. (2011a) explored teachers’ conceptions of assessment in mainland China and Hong Kong. The participants agreed to three conceptions of assessment: improvement, accountability, and irrelevant. The authors found that improvement positively correlated with accountability conception. These findings were consistent with Brown et al. (2009) previous study in Hong Kong. Akin to Chinese teachers, Egyptian and Ecuadorian teachers also associated student accountability with improvement despite the governments’ attempts to strike a balance between large-scale testing and formative assessment (Gebril and Brown, 2014; Brown and Remesal, 2017; Gebril, 2017).

Research into conceptions of assessment is also characterized by tensions and conflicts between external high-stakes assessments and formative assessments. Bonner (2016) noted that teachers struggle to synergize externally mandated high-stakes assessments with their positive conceptions of formative assessment, particularly in contexts where the two forms of assessment are disintegrated. The lack of synergy between summative and formative assessments often results in the former assessment overriding the latter due to the need to satisfy accountability demands (Buhagiar, 2007). Brown and Remesal (2017) rightly pointed out that the success of the new formative assessment initiatives relies on reducing the dominance of high-stakes assessments. For the authors, it is not simply a question of adding a new “soft” policy of formative assessment into the existing “hard” policy of high-stakes assessments.

Overall, teachers’ conceptions of assessment are overly complex. Conceptions tend to vary depending on the assessment policy espoused in an educational context and the educational level teachers teach. Primary school teachers are more likely to endorse the improvement conception of assessment, while secondary school teachers are more inclined to view assessment as making students accountable. The call for teachers to use assessment to improve instruction in the classroom while maintaining the dominance of external high-stakes assessments has created tensions between summative and formative assessments, which teachers might have to learn to balance.

Theoretical framework

Conceptions of assessment

The terms beliefs, conceptions, and views are often used interchangeably in the educational assessment literature (Pajares, 1992). Thompson (1992, p. 30) defines conceptions as “a more general mental structure, encompassing beliefs, meanings, concepts, propositions, rules, mental images, preferences, and the like.” The term conception was used for this study because it encompasses knowledge and beliefs (Opre, 2015). This enables researchers to view knowledge and beliefs as a single construct, which provides an essential conceptual framework for analyzing teachers’ “overall perception and awareness of assessment” (Barnes et al., 2015, p. 285).

Brown (2004, 2008) proposed a conceptual framework of conceptions of assessment. His framework comprises three major purposes of assessment and a counter-purpose: improvement, school accountability, student accountability, and irrelevant. The first conception is grounded in the premise that assessment should be used to improve classroom instruction (Black and Wiliam, 1998; Black et al., 2003). This conception of assessment is associated with formative and diagnostic assessments (Barnes et al., 2015). School accountability conception centers on the idea that assessment should be used to determine how effective a school is or how well teachers are doing their job (Butterfield et al., 1999) and how well schools use their resources (Brown, 2004). Teachers and schools can either be rewarded or penalized depending on whether they succeed or fail to meet the standards defined by the government (Opre, 2015; Nichols and Harris, 2016). The fundamental tenet of the school accountability conception of assessment is that schools and teachers have to demonstrate to the public in general that they are delivering high-quality instruction to students and that they are enhancing the quality of instruction in the classroom (Brown et al., 2011b, p. 211).

The third conception of assessment, student accountability, rests on the notion that assessment should be used to hold students responsible for their learning by assigning grades to their work, comparing their achievement to predefined performance standards, reporting their grades to parents, future employers and other teachers, and granting certificates according to their achievement (Harris and Brown, 2009; Segers and Tillema, 2011). While some teachers believe high-stakes assessments are necessary to motivate students to learn, some believe that tests have a negative impact on students (Brown et al., 2011b).

The last conception of assessment, assessment as irrelevant, is based on the belief that external summative assessments are irrelevant to the learning and teaching process (Brown, 2004). Assessment is also deemed irrelevant “if it is seen as diverting time and attention away from teaching and learning, if it is viewed as unfair or negative for students, or if it is viewed as invalid or unreliable” (Harris et al., 2008, p. 3). Assessment can also be considered irrelevant if conducted but not used, or if teachers conduct it just to conform with the government legislation or assessment policy (Harris and Brown, 2009).

Another model of conceptions of assessment has been proposed by Remesal (2011). She put forward a continuum model of teachers’ conceptions of assessment based on the role of assessment in teaching, learning, teacher accountability, and student accreditation. Remesal placed the pedagogical conception (improvement conception) at one end and the societal conception (teachers’ accountability and certification of teaching) at the other end. Between the two ends, the author placed some mixed conceptions of assessment.

Although conceptions of assessment were discussed individually, teachers hold multiple conceptions of assessment simultaneously, sometimes complementary or contradictory (Fives and Buehl, 2012; Barnes et al., 2017). Brown et al. (2011b) argue that this is because educational assessment is used for multiple purposes concurrently. This small-scale qualitative study explored the conceptions of assessment held by secondary school teachers of English in Mozambique. The study sought to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the teachers’ views about the current assessment policy adopted by the government of Mozambique?

RQ2: What conceptions of assessment are held by secondary school teachers of English in Mozambique?

Study context: Assessment in Mozambique

Primary education is compulsory and free in Mozambique: every student must complete all the first 7 years of compulsory schooling (from grade one to grade seven). After completing primary education, students may enroll in secondary education, which encompasses 5 years of optional schooling. To enter university, students need to pass an entrance examination, which is highly competitive.

The government of Mozambique adopted the current secondary school policy in 2008. The policy prescribes various informal and three formal assessments to be conducted each term: two planned formative assessments and one summative assessment (MINEDH, 2019). The classroom teacher usually administers the formative assessments, which involve grading, suggesting that the assessment information is used for both summative and formative purposes. This is in accord with the view that separating summative and formative assessment is unproductive (Taras, 2005, 2009). The teachers’ written assessments have comparatively the same weight on the student grade average as the final tests. The summative assessments are either internal or external and are done at the end of each term. According to guideline documents, the purpose of summative assessments is to monitor students’ mastery of the curriculum, diagnose their difficulties, and provide them with timely pedagogical interventions, suggesting that teachers have to use all forms of assessment to improve learning and teaching. Although the policy emphasizes formative assessment, Mozambique is relatively dominated by examinations. Therefore, Mozambique could be classified as what Brown et al. (2019) called a high-stakes assessment context.

Materials and methods

Research design

An explanatory sequential mixed-methods design was adopted. This design consists of collecting quantitative data first, analyzing the data, and then using the results to plan the qualitative phase of the study (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). The quantitative phase of the study explored teachers’ perceived language assessment literacy (Muianga, 2022). The findings suggest that the participants attained the recommended language assessment literacy level in scores and decision-making and theories and principles. However, their perceived language assessment literacy remains below the recommended in technical skills and language pedagogy, emphasizing the need for a professional development program in assessment.

The qualitative phase of the study focused on two distinct aspects: teachers’ conceptions of assessment and formative use of summative assessment practices. The findings on teachers’ formative use of summative assessments will be reported elsewhere (Muianga, in review). Thus, this paper concentrated exclusively on teachers’ conceptions of assessment. The two papers are closely related since the participants of the studies are the same and the data were collected concurrently. However, the two studies differ greatly. While the current paper concentrated on conceptions of assessment, the other focused on use of summative assessment formatively.

Given that the conceptions of assessment remain unexplored in the Mozambican context, the interview guide approach was used to collect the data (Johnson and Christensen, 2016). This approach enabled the researcher to obtain elaborate descriptions of the teachers’ conceptions of assessment.

Participants

The target population was secondary school teachers of English as a foreign language in Mozambique. The study was conducted in Maputo, involving 12 teachers from different schools in Maputo City and Maputo Province. All the teachers participated in the first phase of the study: they responded to a survey on English language teachers’ assessment literacy. The extreme-case sampling technique was employed to select teachers for interviews. This technique involves identifying and selecting outstanding cases and notable failures for further examination (Johnson and Christensen, 2016). Before selecting the participants for interviews, the mean of their responses to the survey was computed using IBM SPSS 28.0 Software. Then, the selection process was based on their perceived assessment literacy: teachers who reported the highest and the lowest perceived assessment literacy were selected for the interviews. It is presumed that the two groups might differ in how they conceive of assessment, enabling the researcher to capture different conceptions.

Initially, 20 teachers were invited for the interviews. However, only 15 showed interest in participating. Unfortunately, three potential participants withdrew from the interview at the last minute. Twelve separate interviews were scheduled with teachers; each teacher received the interview protocol a day before the interview. The interviews revolved around teachers’ views about the current secondary school assessment policy and their conceptions of assessment. The participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study without giving explanations. All the participants’ identities were kept confidential. The information about the respondents is provided in Table 1.

Then, the participants were divided into two groups based on their perceived assessment literacy. The first group comprises six participants who reported high perceived assessment literacy. The second group comprises six respondents who reported the lowest perceived assessment literacy. An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the two groups. The high perceived assessment literacy group produced a higher mean score (M = 3.70, SD = 0.24) than the low perceived assessment literacy group (M = 0.94, SD = 0.24). The difference between the two groups was highly statically significant t(10) = 19.68, p ≤ 0.001, two-tailed. The difference between the means was large (difference = 2.75; 95% CI: 2.44 to 3.06; Cohen’s d = 11.46). The two groups were examined for variations in teachers’ conceptions.

Data collection

The data were collected through in-depth interviews. Fontana and Frey (2000) consider interviews “one of the most common and powerful ways in which we try to understand our fellow human beings” (p. 645). The duration of the interviews varied between 40 and 70 min, and all the interviews were recorded with the permission of the interviewees.

The interview protocol (see Appendix) consists of several open-ended questions intended to elicit participants’ views about the new assessment policy and their conceptions of assessment. Open-ended questions allow interviewees to share their personal experiences with the interviewer however they want (Creswell, 2012; Johnson and Christensen, 2016).

The interview protocol was based on the review of the literature on teachers’ conceptions of assessment and secondary school assessment policy documents (Brown, 2008; Azis, 2015; MINEDH, 2019). The questions were divided into three sets. The first set of questions aimed to elicit teachers’ general understanding of assessment, summative assessment, and formative assessment. The questions were also intended to capture teachers’ views about the relationship between summative and formative assessment. The second set of questions concentrated on the assessment process, the use of assessments teachers conduct in the classroom, how assessment information is used, and their conceptions of assessment. The last questions were intended to elicit teachers’ understanding of the current assessment policy and how it influences their daily assessment practices. To ensure reliability, the same interview protocol was used consistently with all the interviewees (Cohen et al., 2002).

Data analysis

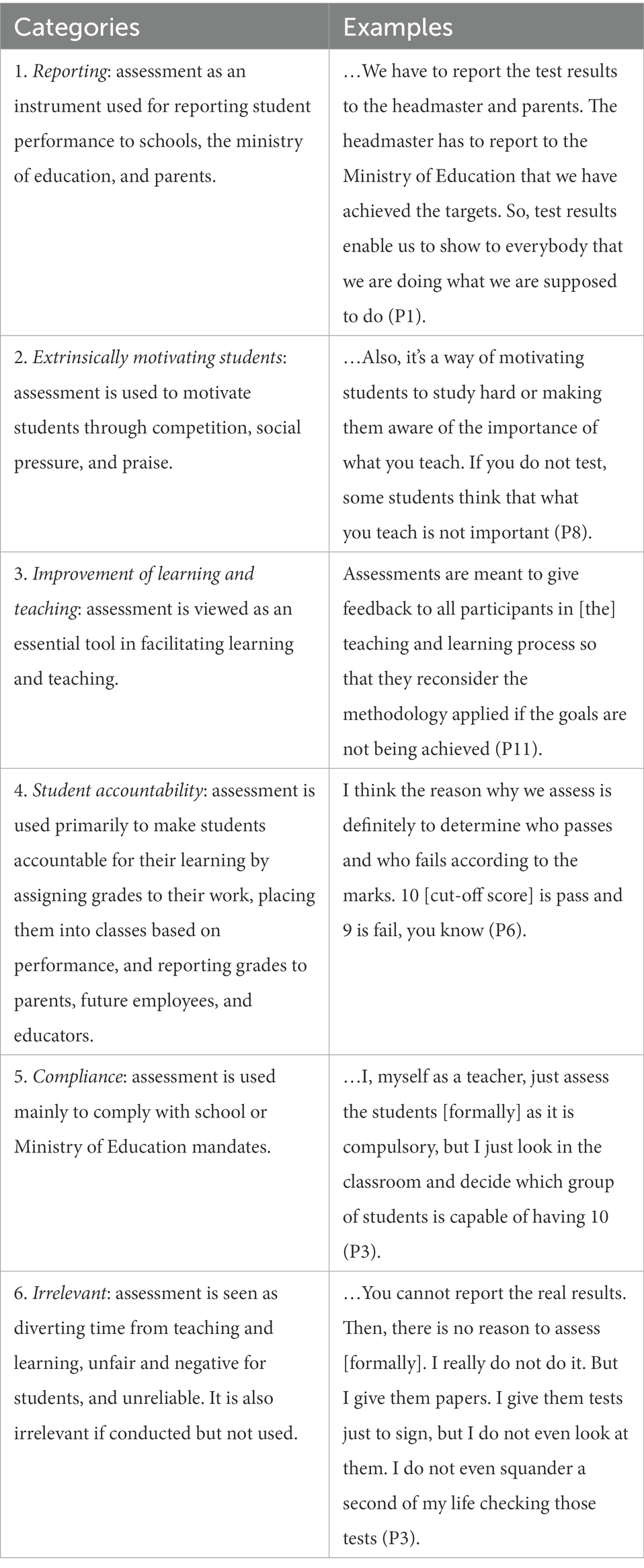

The deductive thematic analysis approach was used to analyze the data about teachers’ conceptions of assessment and teachers’ views about the assessment policy (Creswell and Clark, 2017). The research study followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006, p. 87) guidelines for thematic analysis. The data were transcribed verbatim and re-read entirely multiple times. Subsequently, the researcher started generating the initial codes (e.g., reporting, extrinsically motivating students, and student accountability). The initial coding was done by highlighting and writing notes on the data extracts.

After the coding process, the codes were arranged according to the major themes (e.g., improvement and school accountability). The study used categories of conceptions of assessment described in Harris and Brown (2009) and Brown (2004, 2008). The following example illustrates the coding process. While reading the transcripts, the researcher noted that some teachers kept stating that assessment provides data for reporting to school administrators, who also report to the Ministry of Education. The code “reporting” was assigned to the corresponding extracts. Subsequently, the code “reporting” was placed under the main theme of school accountability. Then, the researcher reviewed how well the coded extracts fit the themes. Lastly, excerpts were selected to illustrate the points the researcher tried to demonstrate.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the coding and the arrangement of the codes under the preconceived themes, the researcher sought the assistance of an external coder, a Ph.D. student. The minor discrepancies in coding were resolved through a discussion. In addition, the researcher sought to obtain feedback from the participants. However, the researcher could get hold of only nine out of twelve participants, with whom he shared and discussed his interpretations and tentative conclusions.

Results

Teachers’ views about the new assessment policy

The teachers were cognizant of the concepts of summative assessment and formative assessment. For example, P4 defined the two forms of assessment in the following terms:

Summative assessment is designed to measure students’ knowledge and decide whether the student passes or fails. This type of assessment is done at the end of a unit or term. On the other hand, formative assessment aims to check students’ progress in the classroom. This kind of assessment may be done in each lesson and provides teachers with diagnostic information about student learning (P4).

The teacher distinguished between summative and formative assessments based on their functions, consistent with the distinction made in educational assessment literature.

The participants were asked about their opinions about the current assessment policy. Most of them (11/12) were not familiar with it. For instance, the P2 commented, “is there a new assessment policy? Where is it? I’m not aware of a new assessment policy. I have never seen or heard of it since I started teaching more than 10 years ago.” Similarly, the P4 said, “what policy are you talking about? Is there a new secondary school assessment policy? I‘m not aware of it if it really exists in schools.”

The teachers’ lack of familiarity with the assessment policy that is supposed to guide their assessment practices is concerning. The only participant aware of it, P8, seems to have a positive outlook on it. However, he laments the lack of its implementation in schools.

The issue of evaluation here in Mozambique is not very clear. We do not have diagnostic evaluation at all. We just assess students after they have started studying, after a month, or a unit. I think the new assessment policy is good because it encourages the use of various types of assessment, including diagnostic assessment. Unfortunately, it is not being implemented in schools. We focus on formal evaluation because we have to report the development of students at the end of the term. That is all that is required from us.

The teacher speculates that some teachers remain unaware of the assessment policy because the normative documents are in electronic form. This could constitute a barrier to many teachers since most secondary schools in Mozambique do not have access to information and communication technologies. The teacher has become familiar with the policy recently on his own initiative.

I've seen the new assessment policy basically now that we are in this situation of the pandemic [between 2020 and 2021]. I have read it. Assessment is not being implemented the way it should be in the schools. Some teachers do not know that an assessment policy exists in the schools. The normative documents are there, and teachers should have access to them, but they're not physical. This is why some of us do not know if it exists or not. But there is an assessment policy that we should follow in order to do things in the right way, but that’s not what happens.

Overall, most participants are unaware of the school assessment policy that should guide their assessment practices. The single participant who is familiar with it seems to have a positive attitude toward it.

Teachers’ conceptions of assessment

The participants were divided into two groups based on their perceived assessment literacy: high and low perceived assessment literacy groups. The teaching experience of the participants varies between 3 and 25 years. The data were analyzed based on the categories described in Brown’ (2004, 2008) and Harris and Brown (2009). Six categories of conceptions of assessment were identified in the data: reporting, extrinsically motivating students, improvement of teaching and learning, student accountability, compliance, and irrelevant (see Table 2 for more details).

Structure of teachers’ conceptions of assessment

Initially, Brown’s (2004, 2008) model of conceptions of assessment was used to examine the structure of teachers’ conceptions; however, it did not fit the data well. Therefore, Remesal’s (2011) framework, which seems to be a good fit, was used while maintaining the main categories described in Brown (2004, 2008). Before putting teachers into categories, with the help of the second coder, the researcher identified individual teacher’s overall conceptions of assessment and, subsequently, located them in the four categories described in Brown (2004, 2008): improvement, student accountability, school accountability, and irrelevant. Teachers whose overall beliefs of assessment fell under a single category were put into that category and classified as holding a pure conception of assessment. Teachers whose beliefs fall under multiple categories were categorized as holding a mixture of those conceptions (i.e., they were categorized as holding mixed conceptions). While some participants reported pure conceptions (either improvement or student accountability), others reported mixed conceptions (mixed school and student accountability and improvement and student accountability and irrelevant).

Improvement conception

Two out of twelve (2/12) teachers reported a pure improvement conception of assessment. They both value the power of assessment in improving learning and teaching.

…Assessment serves to assess students’ level of progress, development, and identify their needs. So, assessment is a diagnostic tool through which the teacher can know where students are and how to take them where they are supposed to be. In a few words, I can say that the role of assessment is check students’ understanding of the content in the classroom. Without assessment, you would not know how effective your teaching is (P10).

This view is corroborated by the second teacher, P11, who also conceives of assessment as an instrument that provides feedback on the effectiveness of instruction to teachers and students.

Assessments are meant to give feedback to all participants in [the] teaching and learning process so that they reconsider the methodology applied if the goals are not being achieved. However, assessments are being used as an instrument to decide who passes and who fails. So, assessment seems to have lost its purpose in Mozambican schools (P11).

The teacher strongly believes the assessment improves the quality of instruction and laments the use of assessment just to make high-stakes decisions about students. There seems to be a discrepancy between the teachers’ values and beliefs about assessment and the assessment practices espoused in his institution.

The first teacher (P10) views summative assessment as another critical dimension of assessment which can provide feedback on the quality of learning and teaching.

…Well, I think that summative assessment is also important for the teachers and students, you see. It is used to select who passes and who fails, but it can provide some type of feedback about how students learned during the course or program, and how the teacher taught. So, this assessment provides feedback too. This feedback can also be used by the teacher and students to promote good teaching and learning (P10).

The teacher’s conceptions of assessment seem to align with the current secondary school assessment policy, which urges teachers to use both summative and formative assessments to promote learning and teaching.

Mixed accountability and improvement conception

Of 12 teachers, five seem to conceive of assessment as making students and schools accountable and improving teaching and learning, meaning they hold mixed conceptions of assessment. Although they seem to hold multiple conceptions of assessment, their conceptions are not evenly distributed. Three teachers prioritize accountability functions, while the other two stress the formative functions. Due to space limitations, one example was provided for each case for illustration purposes.

The first instance corresponds to a 38-year-old teacher with 13 years of teaching experience. His beliefs about assessment seem to lean more toward school and student accountability than improvement. He emphasizes reporting and making high-stakes decisions about students.

Tests are used for reporting and determining who passes and who fails. When students get 9, that is fail and when they get 10 that is a pass. You also have to test students to know how much they have learned. This is the only way we can find out how much students have learned and who passes and who fails (P1).

The teacher also attaches significant importance to improving students’ test performance. This can be seen in his concern with ensuring that his students obtain high grades to demonstrate his effectiveness to parents and the headmaster.

…Well, at the end of each term, we, we have to report the test results to the headmaster and parents. The headmaster has to report to the Ministry of Education that we have achieved the targets. So, tests results enable us to show to everybody that we are doing what we are supposed to do. As teachers, we are responsible for students’ learning. So, I would say that we are expected to meet the goals and present good results. Students’ grades may also have an impact on how the headmaster rates your performance at the end of the year, you know (P1).

In addition, he engages in informal and continuous assessment in the classroom. This assessment enables him to obtain diagnostic information about the effectiveness of ongoing instruction. However, he views formative assessment as an opportunity to prepare students for the written assessment.

I usually assess students in the classroom through questions, exercises, and homework. This allows me to find out if students have understood the lesson being taught or not. If they still have not understood the materials, I may give them more exercises to practice, you know. The exercises and questions is like preparation for the written test. We sometimes practice grammar that is usually evaluated. As I mentioned before, it comes to a point when we have a written assessment, and it’s when we would assess everything that we’ve done probably in a fortnight. We have to ensure that students do well on the written test (P1).

The second case corresponds to a 39-year-old teacher with 10 years of experience. Unlike the previous teacher, he emphasizes the improvement function of assessment. He believes that the key role of assessment is to track students’ learning toward the learning targets and guide teaching.

Evaluation allows the teacher to assess information being taught to students. If they have not understood the content, I might change the approach that I might have used. Probably, the approach I used is not the best one for them. So, evaluation helps determine if I should move forward or I should teach the topic again. For example, you teach the present simple in the classroom and give students notes, examples, and exercises about the present simple. Those exercises allow you to know what students have understood about the present simple and what they haven’t. I think that’s the main role of assessment. Without evaluation, you wouldn’t know what to do next. It’s like a guide, you (see P5).

The teacher views assessment as the activities carried out daily to enhance the quality of instruction. He also acknowledges the importance of examinations to different assessment stakeholders. Nevertheless, he does not seem to endorse them. Examinations compel him to rush through the lessons to cover the exam’s curriculum, depriving students of opportunities to engage in deep and meaningful learning. The emphasis on examinations and examination-related activities contradicts the teacher’s views of learning and assessment.

I also evaluate my students at the end of the unit, or chapter, or semester. We are supposed to. These tests are used to decide who should pass and who shouldn’t. Of course, these tests are important for the school, parents, teachers, and students because they can give feedback about the quality of school and teachers. But, sometimes, they force teachers to rush things in the classroom because we have to complete all the book by the end of the year for the exam. You never know what will be evaluated in the exam. Do you understand what I mean? No time to assess, not time for feedback, no time to make sure that students understand the content. No time at all. So, it feels like we care about completing the books and not if students understand something or not. This is the reason why we have students in grade 12 who cannot speak any English. We do not focus on learning English. We focus on completing the book for the exam (P5).

Mixed student accountability and irrelevant conception

Three out of twelve (3/12) teachers seem to conceive of assessment as simultaneously holding students accountable and irrelevant. All three participants’ conceptions lean more toward student accountability than irrelevant. Two detailed accounts were provided for illustration purposes. The first case pertains to a 34-year-old teacher with 9 years of experience. He believes that assessment is an instrument that categorizes students based on performance. Nevertheless, he feels that it no longer fulfils any purpose since school administrators pressure him to alter the test results when he fails to achieve the pass rate set by the Ministry of Education.

Assessment is used to classify students, but this classification is conditioned by the school superiors… In public schools, in a class of 50 students, teachers have to ensure that more than 90% of students obtain a passing grade so that our superiors may demonstrate work to their superiors. So, assessments become somehow paradoxical or useless view that if students get low marks in some schools, teachers have to rearrange the marks, or they will be seen as non-effective workers…When I started teaching, I remember presenting test results that were below what the headmaster wanted, so he told me to arrange them. At first, I denied it, but then I had a meeting with the headmaster, where I was asked if I wanted to keep my job or not. I had to arrange the students’ grades to keep my job…So, now we assess because we have to, not because they have any purpose (P7).

The failure to improve students’ test scores results in him being instructed to modify students’ grades by the school administrators, which makes him question the role of assessment in education. He conducts assessments just to comply with the school or Ministry of Education mandates, contradicting his beliefs about assessment. Although he seems not to condone it, little can he do due to fear of repercussions. Altering students’ grades enable the schools to obtain illusionary results that meet the authorities’ expectations, allowing them to keep their jobs.

The second instance corresponds to a 42-year-old teacher with 18 years of teaching experience. Akin to the previous example, this teacher believes that assessment is used to make high-stakes decisions about students. However, confronted with the need to attain a high pass rate set by the education authorities, which seems unattainable to him, he started conducting formal assessments to fulfil the school or the Ministry of Education mandates.

Assessment determines who can pass and who does not pass, but in our school, I know that these students are not capable of communicating in English. In a classroom of 50 students, Perhaps, 20 students are capable of obtaining good results. This means that less than 50% of the student have good marks. Even those teachers who are dealing with Primary schools, they are supposed to show results that the headmaster wants, and the headmaster is following instructions from the Ministry of Education. If you showed these results to the headmaster, you would face a problem. You cannot report the real results. Then, there is no reason to assess. I really don’t do it. But I give them papers. I give them tests just to sign, but I don’t even look at them. I don't even squander a second of my life checking those tests. If I took the real results and showed them to the headmaster, I would be crucified. So, you have to produce results. You don’t have to produce tests. I, myself as a teacher, just assess the student as it is compulsory, but I just look in the classroom and decide which group of students is capable of having 10. If a student shows me that he can perform accordingly, this one deserves a passing mark. There’s a group of students, let’s say, quiet. They are likely to have a failing mark because they do not show me how good they are (P3).

The teacher’s belief about his students’ academic abilities seems to shape his assessment and grading practices. Assessing his students formally against the standards would result in many failures, which would have repercussions on him. Therefore, he conducts formal assessments in the classroom just to comply with the school assessment policy, but they do not serve any purpose. The grades attributed to students are based on informal assessment and reflect a myriad of qualities, including participation and effort. This strategy might enable most students to succeed in the classroom, allowing the teacher to achieve the predefined pass rate.

Student accountability

Two out of twelve (2/12) participants reported a pure student accountability conception of assessment. They conceive of assessment as an instrument used to make high-stakes decisions about students, particularly student progression and accreditation.

Assessment measures students’ learning. When I focus on reading, for example, I have to check how well the student performs in reading. When it comes to grammar, I also have to check how they perform in grammar at a certain level. I think the reason why we assess is definitely to determine who passes and who fails according to the marks. 10 is pass and 9 is fail, you know (P6).

The teacher’s beliefs about assessment seem to have been shaped by his previous experience as a student and teacher. Based on his age, 37, it is safe to conjecture that when the new assessment policy was introduced in k-12 education, he had already graduated from high school. Before then, assessments fulfilled mostly summative functions, which might have influenced his beliefs about assessment.

The teachers also believe that assessment is used to select and place students in a class or educational level suitable for their academic abilities.

…I used to teach grade 3. Some students had abilities above the others, so I may use it to determine if the student should go to the next class or not. Assessment determines how they can fit in other classes because he’s got abilities that the other students do not have. They cannot go with him. Keeping him would not be good. It’s like holding him back. Assessment helped to do that (P6).

In Mozambique, there is an apparent lack of specialized programs for gifted and talented students. In elementary education, students with higher academic abilities than their peers take a high-stakes assessment, and if they pass it, they are usually promoted to the upper classes, where it is believed their educational needs will be met.

In addition, the teachers conceive of assessment as an extrinsic motivation device, which encourages students to study hard. They use the power of assessment to influence the content students should focus on.

…Also, it’s a way of motivating students to study hard or making them aware of the importance of what you teach. If you do not test, some students think that what you teach is not important. Some content may be ignored by students if it is not assessed because it is not important. That’s one of the reasons for testing students (P8).

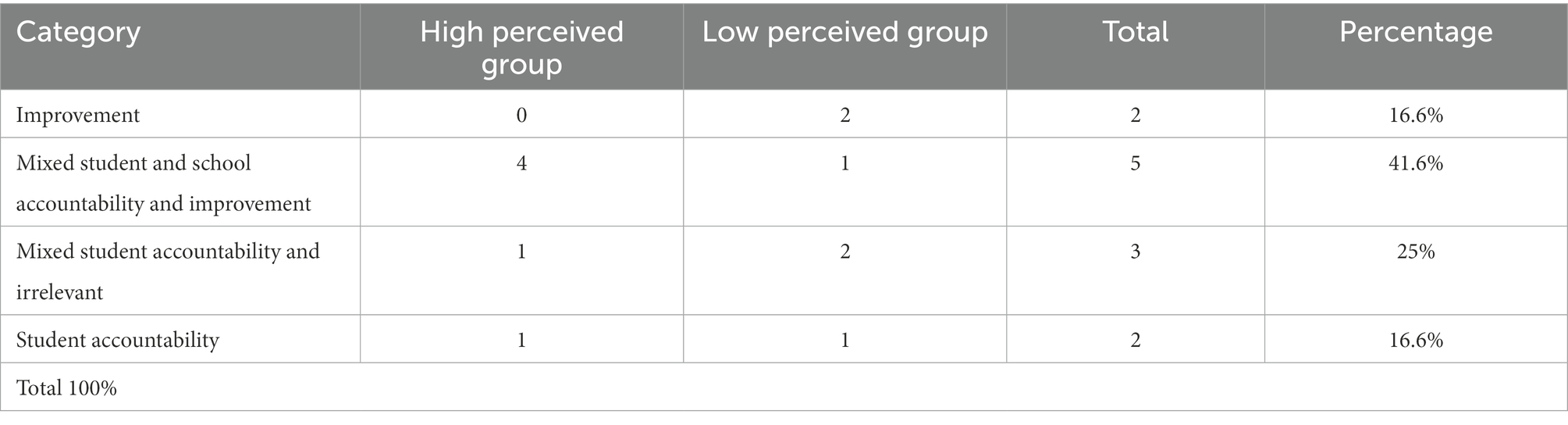

Conceptions of assessment and teachers’ perceived assessment literacy

Table 3 shows the distribution of conceptions between the first group (high perceived assessment literacy group) and the second group (low perceived assessment literacy group). In the first group, the participants’ age and years of experience vary between 32–43 years and 10–18 years, respectively. In the second group, the participants’ ages vary between 31 and 49 years, while years of experience vary between 3 and 25 years.

The teachers in the two groups hold slightly different conceptions. In the first group, more than half of teachers (4/6) reported mixed school and student accountability and improvement conception compared to only (1/6) in the second group. This may suggest that participants in the first group were more likely to have mixed school and student accountability and improvement conception than in the second group. In addition, in the first group, (1/6) indicated mixed student accountability and irrelevant conception compared to (2/6) in the second group, indicating a slight difference between the two groups. The last difference between the two groups is that, in the first group, nobody holds a pure improvement conception compared to (2/6) in the second group. The only similarity that the two groups have is that, in each group, one out of six teachers (1/6) hold a pure student accountability conception.

Overall, it is impossible to draw solid conclusions about the relationship between teachers’ conceptions and their perceived assessment literacy due to the sample size. However, the teachers in the first group were more inclined to hold mixed school and student accountability and improvement conception than teachers in the second group. On the other hand, teachers in the second group were bound to hold a pure improvement conception and mixed student accountability and irrelevant conception of assessment.

Discussion and conclusion

This small-scale study investigated English language teachers’ views about the current secondary school assessment policy and their conceptions of assessment. Regarding the first research question, the findings suggest that most participants are still unfamiliar with the policy. The teachers’ unfamiliarity with the policy could be partially attributed to the fact that it was introduced before most of them became teachers. Concerning the second research question, participants reported different conceptions of assessment: reporting, extrinsically motivating students, improvement of teaching and learning, student accountability, compliance, and irrelevant. There were some variations in teachers’ conceptions of assessment. While some teachers self-reported pure conceptions of assessment (either pure student accountability or improvement), others indicated mixed conceptions (mixed school and student accountability and improvement and mixed student accountability and irrelevant). In addition, the teachers’ conceptions are not evenly distributed, echoing Remesal (2011), who found that teachers’ conceptions of assessment tend to incline either toward the pedagogical or accreditation function and are often mixed.

About half of the participants reported the student accountability conception, or their mixed conceptions tended to incline more toward the student accountability conception, corroborating the claim that secondary school teachers tend to endorse the student accountability conception of assessment (Yates and Johnston, 2018). This finding could be partially explained by the fact that secondary school teachers engage in various certification-related assessment activities, which have significant consequences on students (e.g., retention or progression) depending on their performance (MINEDH, 2019). Teachers’ formal assessments involve grading, and such grades have relatively the same weight on students’ grades average as external summative assessments. In addition, the findings show that few participants hold mixed conceptions that incline toward school and student accountability. One of the possible explanations for this finding is that despite the recent shift from summative to formative assessment, Mozambique continues to be dominated by tests, which may affect teachers’ views about assessment. According to Fulmer et al. (2015), teachers’ conceptions of assessment tend to align with the assessment practices espoused in their teaching context.

The results also illustrate that about another half of participants indicated pure improvement conceptions or mixed conceptions that inclined toward the improvement conception. These findings are encouraging since previous research demonstrated that teachers’ conceptions of assessment influence their assessment practices (Xu and Brown, 2016; Barnes et al., 2017), and they are in line with the current secondary school assessment guidelines, which urge teachers to emphasize formative assessment rather than summative assessment (INDE/MINED, 2007). This finding is relatively similar to those reported in Remesal (2011).

The findings reveal teachers’ struggle to reconcile summative assessment with formative assessment activities. Bonner (2016) already reported teachers’ struggle to balance summative and formative assessments, particularly in contexts where they are not integrated. Although the assessment guidelines encourage the integration of summative and formative assessments by using the same assessment information for both accountability and improvement purposes (MINEDH, 2019), a few participants who hold positive conceptions of assessment lamented that some stakeholders (e.g., school administrators and parents) endorse the former function of assessment rather than the latter. So, teachers feel compelled to focus on improving students’ performance on tests by maximizing the coverage of the curriculum before they focus on helping students master the curriculum contents (Barnes et al., 2015). Previous research reported that cultural norm or societal perception of assessment poses a serious obstacle to implementing formative assessment (Yan et al., 2021).

In addition, the assessment policy itself exacerbates the tensions between summative and formative assessments. Adopting formative assessment initiatives can push teachers to implement formative assessment (Kim, 2019). However, as Brown and Remesal (2017) pointed out, its successful implementation in high-stakes assessment contexts depends on reducing the dominance of high-stakes assessments. It is not simply a question of adding a new “soft” policy of formative assessment into the existing “hard” policy of high-stakes assessments. The current assessment policy emphasizes formative assessment; however, schools and teachers are still evaluated based on students’ performance on summative assessments. In these circumstances, teachers tend to prioritize summative assessment more than formative assessment (Brown and Gao, 2015).

The findings also reveal the ineffectiveness of using test results to evaluate the effectiveness of teachers and schools. The fear of repercussions for failure to improve students’ achievement compels some school administrators to instruct teachers to inflate student test scores, a practice that may lead to misleading information about teachers’ quality and the students’ achievement (Rose, 2015; Morgan, 2016). Another strategy that undermines the use of tests for school accountability is not following the recommendations for assessment and grading practices. Some participants rely entirely on informal assessment and academic enabling behavior (e.g., participation and effort) rather than academic performance. This strategy enables the teachers to obtain a higher success rate than they would if they used formal assessment and assessed students’ achievement against the standards. However, it also provides misleading information about students’ achievement. Previous literature reported that teachers often consider a myriad of factors in their assessment and grading practices, but they include academic performance— it tends to be the most critical factor (McMillan, 2001; McMillan et al., 2002).

Some participants in the study did not report positive conceptions of assessment, calling for professional development programs in assessment. Training in assessment has been found to help teachers develop positive conceptions of assessment (Levy-Vered and Alhija, 2018). The professional development program should focus on helping different assessment stakeholders (e.g., school administrators and teachers) develop skills and solid knowledge about assessment. Parents will also need training in assessment based on their participation in the assessment process (Taylor, 2013; Kremmel and Harding, 2020). However, training stakeholders while maintaining the use of tests for school accountability might not lead to substantial changes to the assessment system.

Appropriate assessment development program should include disciplinary knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge; knowledge of assessment purposes, content, and methods; knowledge of grading; knowledge of feedback; knowledge of assessment interpretation and communication; knowledge of student involvement in assessment; and knowledge of assessment ethics (Xu and Brown, 2016, p. 156). Besides knowledge and skills, the professional development program should consider assessment conceptions (Deneen and Brown, 2016; Xu and Brown, 2016). Conceptions of assessment influence teachers’ understanding, interpretation, and implementation of new assessment knowledge (Opre, 2015; Barnes et al., 2017). The course should help teachers raise awareness of their conceptions of assessment, reflect on them, and subsequently reshape them.

It is also highly recommended that the professional development program incorporates six features deemed critical to its effectiveness (Dunst et al., 2015; Maandag et al., 2017). First, it should be long-term rather than short-term (Cordingley et al., 2015). A long-term professional development program would enable the participants to master and revisit the new assessment knowledge. Second, it should involve a community of practice (Dunst et al., 2015). Communities of practice would allow the participants to work collaboratively, providing an opportunity to challenge one another and dispel misunderstandings. Third, professional development should be voluntary rather than mandatory. In cases where it is mandatory, teachers need to understand the rationale and the benefits of participating in the program (Timperley et al., 2007). Forth, it should involve teachers’ training in the subject matter (Garet et al., 2001; Xu and Brown, 2016), which means that assessment knowledge and subject knowledge would be delivered to the participants concurrently. Fifth, it should involve outside rather than inside school expertise (Walter and Briggs, 2012). This would enable the participants to be exposed to innovative ideas about assessment. Sixth, it should be practice-based rather than exclusively theoretical (Dunst et al., 2015). Combining theory and practice would allow the participants to put the new assessment knowledge into practice.

This small-scale qualitative study is not devoid of limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small, which reduces the power of the study. Secondly, the study was conducted only in Maputo, Mozambique. Consequently, these findings cannot be generalized to other regions. There is a need for large-scale quantitative research on the issue. Such studies should involve language teachers at different educational levels (primary, secondary, and tertiary education) in different regions of Mozambique. Thirdly, our data were collected through interviews, which “rely on self-report, which is more susceptible to distortion and error” (Gall et al., 2013, p. 106). Lastly, there is a complete lack of previous research on the issue in the Mozambican context, upon which this study would build.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ministry of Education of Mozambique. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The author did not receive funding for this research project. However, the author is beneficiary of a PhD scholarship provided by the Masaryk University during the period of 1/2022–12/2022.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Azis, A. (2015). Conceptions and practices of assessment: a CASE of teachers representing improvement conception. TEFLIN 26, 129–154. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v26i2/129-154

Barnes, N., Fives, H., and Dacey, C. M. (2015). “Teachers’ beliefs about assessment” in International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs eds. Helenrose Fives and Michele Gregoire Gill (London, Routledge), 284–300.

Barnes, N., Fives, H., and Dacey, C. M. (2017). U.S. teachers’ conceptions of the purposes of assessment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 65, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.017

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., and Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting It into Practice, 1st Ed. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Bonner, S. M. (2016). “Teachers’ perceptions about assessment: competing narratives” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment. eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 21–39.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: implications for policy and professional development. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 11, 301–318. doi: 10.1080/0969594042000304609

Brown, G. (2008). Conceptions of Assessment: Understanding What Assessment Means to Teachers and Students. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers

Brown, G. T. L., and Gao, L. (2015). Chinese teachers’ conceptions of assessment for and of learning: six competing and complementary purposes. Cogent Educ. 2:993836. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2014.993836

Brown, G. T. L., Gebril, A., and Michaelides, M. P. (2019). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: a global phenomenon or a global localism. Front. Educ. 4:16. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00016

Brown, G. T. L., Hui, S. K. F., Yu, F. W. M., and Kennedy, K. J. (2011a). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment in Chinese contexts: a tripartite model of accountability, improvement, and irrelevance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 50, 307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2011.10.003

Brown, G. T. L., Kennedy, K. J., Fok, P. K., Chan, J. K. S., and Yu, W. M. (2009). Assessment for student improvement: understanding Hong Kong teachers’ conceptions and practices of assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 16, 347–363. doi: 10.1080/09695940903319737

Brown, G. T. L., Lake, R., and Matters, G. (2011b). Queensland teachers’ conceptions of assessment: the impact of policy priorities on teacher attitudes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.003

Brown, G. T. L., and Michaelides, M. P. (2011). Ecological rationality in teachers’ conceptions of assessment across samples from Cyprus and New Zealand. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 26, 319–337. doi: 10.1007/s10212-010-0052-3

Brown, G. T. L., and Remesal, A. (2017). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: comparing two inventories with Ecuadorian teachers. Stud. Educ. Eval. 55, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.07.003

Buhagiar, M. A. (2007). Classroom assessment within the alternative assessment paradigm: revisiting the territory. Curric. J. 18, 39–56. doi: 10.1080/09585170701292174

Butterfield, S., Williams, A., and Marr, A. (1999). Talking about assessment: Mentor-student dialogues about pupil assessment in initial teacher training. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 6, 225–246. doi: 10.1080/09695949992883

Cordingley, P., Higgins, S., Greany, T., Buckler, N., Coles-Jordan, D., Crisp, B., et al. (2015). Developing Great Teaching: Lessons from the International Reviews into Effective Professional Development. Teacher Development Trust. Available at: https://tdtrust.org/about/dgt (Accessed August 27, 2022).

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Boston, USA: Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Deneen, C., and Boud, D. (2014). Patterns of resistance in managing assessment change. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 577–591. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.859654

Deneen, C. C., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). The impact of conceptions of assessment on assessment literacy in a teacher education program. Cogent. Education 3, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1225380

Dunst, C. J., Bruder, M. B., and Hamby, D. W. (2015). Metasynthesis of in-service professional development research: features associated with positive educator and student outcomes. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 1731–1744. doi: 10.3102/0013189X07308739

Fives, H., and Buehl, M. M. (2012). “Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: what are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us?” in APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol. 2: Individual Differences and Cultural and contextual factors. eds. K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, and M. Zeidner (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 471–499.

Fontana, A., and Frey, J. H. (2000). The interview: from structured questions to negotiated text. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage 2, 645–672.

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C. H., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers’ assessment practices: an integrative review of research. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy and Pract. 22, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Gall, J. P., Gall, M. D., and Borg, W. R. (2013). “Applying educational research” in Pearson New International Edition PDF eBook: How to Read, Do, and Use Research to Solve Problems of Practice (London: Pearson Education)

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., and Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 915–945. doi: 10.3102/00028312038004915

Gebril, A. (2017). Language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: an Egyptian perspective. Teach. Dev. 21, 81–100. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2016.1218364

Gebril, A., and Brown, G. T. L. (2014). The effect of high-stakes examination systems on teacher beliefs: Egyptian teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 21, 16–33. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.831030

Harris, L. R., and Brown, G. T. L. (2009). The complexity of teachers’ conceptions of assessment: tensions between the needs of schools and students. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 16, 365–381. doi: 10.1080/09695940903319745

Harris, L., Irving, S. E., and Peterson, E. (2008). Secondary teachers’ conceptions of the purpose of assessment and feedback. Annual conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Brisbane, Australia, 22.

INDE/MINED. (2007). Ministério da Educação e Cultura Instituto Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (INDE) iPLANO CURRICULAR DO ENSINO SECUNDÁRIO GERAL (PCESG). Imprensa Universitária, UEM. Available at: https://docplayer.com.br/30666189-Plano-curricular-do-ensino-secundario-geral-pcesg-documento-orientador-ficha-tecnica.html (Accessed September 18, 2022).

Johnson, R. B., and Christensen, L. (2016). Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Kim, H. (2019). Teacher learning opportunities provided by implementing formative assessment lessons: becoming responsive to student mathematical thinking. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 17, 341–363. doi: 10.1007/s10763-017-9866-7

Kremmel, B., and Harding, L. (2020). Towards a comprehensive, empirical model of language assessment literacy across stakeholder groups: developing the language assessment literacy survey. Lang. Assess. Q. 17, 100–120. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2019.1674855

Levy-Vered, A., and Alhija, F. N.-A. (2018). The power of a basic assessment course in changing preservice teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Stud. Educ. Eval. 59, 84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.04.003

Maandag, D., Helms-Lorenz, M., Lugthart, E., Verkade, A., and van Veen, K. (2017). Features of Effective Professional Development Interventions in Different Stages of Teacher’s Careers: NRO Report, Netherlands:Teacher Education Department of the University of Groningen.

McMillan, J. H. (2001). Secondary teachers’ classroom assessment and grading practices. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 20, 20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2001.tb00055.x

McMillan, J. H., Myran, S., and Workman, D. (2002). Elementary teachers’ classroom assessment and grading practices. J. Educ. Res. 95, 203–213. doi: 10.1080/00220670209596593

MINEDH. (2019). Diploma Ministerial n.o 7/2019. IMPRENSA NACIONAL DE MOÇAMBIQUE, E. P. Available at: https://gazettes.africa/archive/mz/2019/mz-government-gazette-series-i-dated-2019-01-10-no-7.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2022).

Morgan, H. (2016). Relying on high-stakes standardized tests to evaluate schools and teachers: a bad idea. Clearing House J. Educ. Strateg. Issues and Ideas 89, 67–72. doi: 10.1080/00098655.2016.1156628

Muianga, F. (2022). Language assessment literacy: investigating English language teachers’ assessment literacy in Mozambique. Pavel Jozef Šafárik University in Košice 5:17. doi: 10.33542/EDU2022-1-0

Nichols, S. L., and Harris, L. R. (2016). “Accountability assessment’s effects on teachers and schools” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment. eds. G. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York, NY: Routledge), 40–56.

Opre, D. (2015). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 209, 229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.222

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 307–332. doi: 10.3102/00346543062003307

Rea-Dickins, P. (2004). Understanding teachers as agents of assessment. Lang. Test. 21, 249–258. doi: 10.1191/0265532204lt283ed

Remesal, A. (2011). Primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions of assessment: a qualitative study. Teach. Teach. Educ. Int. J. Res. Stud. 27, 472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.09.017

Segers, M., and Tillema, H. (2011). How do Dutch secondary teachers and students conceive the purpose of assessment? Stud. Educ. Eval. 37, 49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.008

Taras, M. (2005). Assessment–summative and formative–some theoretical reflections. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 53, 466–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2005.00307.x

Taras, M. (2009). Summative assessment: the missing link for formative assessment. J. Furth. High. Educ. 33, 57–69. doi: 10.1080/03098770802638671

Taylor, L. (2013). Communicating the theory, practice and principles of language testing to test stakeholders: some reflections. Lang. Test. 30, 403–412. doi: 10.1177/0265532213480338

Thompson, A. G. (1992). “Teachers’ beliefs and conceptions: a synthesis of the research” in Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning: A Project of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. ed. D. A. Grouws (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co, Inc), 127–146.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration (BES). Wellington: Ministry of Education

Walter, C., and Briggs, J. (2012). What professional development makes the most difference to teachers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Xu, Y., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy in practice: a reconceptualisation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 58, 149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.010

Yan, Z., Li, Z., Panadero, E., Yang, M., Yang, L., and Lao, H. (2021). A systematic review on factors influencing teachers’ intentions and implementations regarding formative assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 28, 228–260. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2021.1884042

Yates, A., and Johnston, M. (2018). The impact of school-based assessment for qualifications on teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 25, 638–654. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2017.1295020

Appendix

Interview Protocols

1. What is assessment, and what is your view on assessment?

1.1. What is your understanding of summative and formative assessment?

1.2. How important are these two forms of assessment in your classroom?

1.3. What is the relationship between summative and formative assessment?

2. What is the use of language assessments that you conduct in your classroom?

2.1. In your opinion, what is the use of language assessment?

2.2. How do you usually test/assess your students’ performance in the classroom?

2.3. Do you provide students with feedback based on their performance on tests/assessments? If yes, how do you do it? How is

3. The government of Mozambique introduced a new assessment policy in 2003 and 2008, targeting elementary and secondary education, respectively.

3.1. What is your view on the new assessment policy introduced in secondary education in 2008?

3.2. To what extent the new assessment policy guides your assessment activities?

Keywords: language teacher, teacher assessment, assessment policy, conceptions of assessment, Mozambique

Citation: Muianga F (2023) English language teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Front. Educ. 7:972005. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.972005

Edited by:

Guillermo Solano-Flores, Stanford University, United StatesReviewed by:

Ana Remesal, University of Barcelona, SpainGustaf Bernhard Uno Skar, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

Gavin T. L. Brown, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright © 2023 Muianga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felizardo Muianga, ✉ NDUyODg4QG1haWwubXVuaS5jeg==

Felizardo Muianga

Felizardo Muianga