- 1School of Education, Leadership and Public Service, Northern Michigan University, Marquette, MI, United States

- 2Department of English, Millikin University, Decatur, IL, United States

This article reports on the findings from a cross-institutional study of how arts-based reflection helped teacher candidates to identify and express their thoughts, feelings, and actions regarding the process of learning to teach. Inspired by PostSecret, teacher candidates created anonymous artwork to represent their experiences as student teachers. Through their artwork, candidates highlighted moments of perceived dissonance between their teacher preparation program and K-12 school settings. Additionally, when selecting one piece of art as inspiration for a written reflection, teacher candidates gravitated toward the artwork that provided emotional windows and mirrors into their own experiences. This study holds significance for recognizing and responding meaningfully to the difficult emotional work of learning to teach.

Introduction

Student teaching is an intensive time in the teacher preparation experience. Britzman (2003) asserted, “Negotiating among what may seem to be conflicting visions, disparaging considerations, and contesting interpretations about social practice and the teacher identity is part of the hidden work of learning to teach” (p. 26). Teacher identity development suggests personal transformation and requires teachers to be able to question their own beliefs and instructional strategies in order to reinforce personal agency and self-awareness. According to McKay and Sappa (2020), it also requires creativity where teachers are able to “think outside conventional or usual boxes in order to generate novel solutions to complex dynamics associated with their work” (p. 26).

In recent years, teacher education researchers have demonstrated that visual art forms—collage, self-portraits, drawings, etc.—are particularly powerful and creative approaches to promoting self-reflection and continued teacher identity development in relationship to these complex dynamics (e.g., Beltman et al., 2015; Culshaw, 2019; McKay, 2019, 2021; Holappa et al., 2021). McKay and Barton (2018) write, “using arts-based approaches can enhance the quality and depth of reflection. When teachers engage with arts-based reflection, it has the potential to reveal valuable information about personal and contextual resources on which they can draw when elements of their work become a threat” (p. 364). Additionally, arts-based reflection allows for deeper understanding of teacher candidates’ emotions and emotional responses throughout the process of learning to teach (McKay and Sappa, 2020).

This article reports on the findings from a cross-institutional study of how arts-based reflection helped teacher candidates to identify and express their thoughts, feelings, and actions regarding the process of learning to teach. Specifically, we—two teacher educators working within not dissimilar 4-year, university-based teacher preparation programs in the American Midwest—explore how a visual arts-based approach to reflection can support teacher candidates during student teaching, a complex time in their learning trajectory. Knowing that professional identity work is part of the hidden curriculum of a teacher candidate’s student teaching experience (Britzman, 2003), we ask: How might an arts-based reflection help candidates to express their thoughts, feelings, and actions regarding this often invisible process of learning to teach?

Theoretical framework

Teacher identity is a commonly researched topic (e.g., Clandinin and Connelly, 2000; Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009; Lavina et al., 2020; McKay, 2021; Chen et al., 2022); however, scholars have varying definitions of what constitutes teacher identity. In this study, we understand teacher identity as a narratively constructed and reconstructed response to the question: “Who am I as a teacher?” (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000), where a teacher’s answer is ever-changing and (un)consciously influenced by the audience and the situation in which the story is being told (Uitto et al., 2015). Knowing that teachers live in the midst of different collective narratives about who teachers can or should be, Shapiro (2010) notes that a teacher’s professional identity is also often influenced by the shared “collective memories of educational triumphs, classroom tensions, and—perhaps, most significantly—a secret dread of what we are not doing ‘right”’ (p. 617).

The collective dread Shapiro (2010) mentions is indicative of the emotional work of forming one’s teacher identity. Teachers learn through their personal and professional experiences as students, teacher candidates, and early-career teachers that “it is more acceptable to feel and show some emotions in their work than other [emotion]s, and this notion influences their identities as teachers” (Uitto et al., 2015, p. 165). For teacher candidates in particular, student teaching can be an emotionally-taxing time because, at this stage, the process of defining one’s teacher identity is often characterized by the dissonance individuals feel between who they perceive themselves to be and who they think they need to become to be teachers (Said, 2014; Barkhuizen, 2016). For this reason, teacher candidates’ emotions and their teacher identities are inextricably connected; as Barcelos (2017) explained, “we are shaped by our emotions and beliefs, and these in turn shape the kinds of identities we construct for ourselves” (p. 148).

Teacher identity development implies personal transformation (McKay and Sappa, 2020), and experiences that offer “transformative opportunities to think beyond “well-traveled” approaches by engaging multi-sensory modes of expression widen our creative boundaries” open space for teachers and teacher candidates to explore their emerging teacher identities in a new light (Lavina et al., 2020, p. 416). Thus, in order to better understand the reflective and emotional experiences of teacher candidates in this process, we draw upon the metaphor of windows and mirrors (Style, 1988; Bishop, 1990), a popular framework developed for understanding the power and impact of children’s stories for promoting empathy and perspective-taking. This framework has also shown effectiveness in relation to pedagogy and teacher education. In the development of her culturally relevant pedagogy framework, Ladson-Billings (1995a,b) used windows and mirrors as a metaphor to encourage classroom teachers to critically reflect upon their curricular and instructional practices to ensure that all students, regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc., have opportunities to both see themselves and their identities reflected in the curriculum (mirrors) as well as to explore the experiences and practices of persons different from themselves (windows).

Many of the educational and pedagogical frameworks that have grown from Style’s and Bishop’s original conceptions of windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors (e.g., Ladson-Billings, 1995a,b: culturally relevant pedagogy; Muhammad, 2020: culturally responsive literacy; Paris and Alim, 2017: culturally sustaining pedagogy; Souto-Manning et al., 2018: culturally relevant teaching, etc.), posit that all students should have access to both windows and mirrors throughout the curriculum, which often privilege dominant identities over other ways of being. Thus, the metaphor of windows and mirrors in the classroom is directly tied to a student’s sense of identity, value, and self-worth as they experience the classroom. In this study, we extend the utility of the metaphor to examine the ways in which teacher candidates experience K-12 classrooms during their coursework and student teaching. It serves as an important lens for thinking about the ways in which teacher candidates make sense of their emergent teacher identities as part of their teacher education program, where instructional practice and theory are often privileged over discussions of identity and emotion (Chen et al., 2022).

Materials and methods

This study utilizes arts-based educational research (ABER) as a methodology for exploring teacher candidates’ emerging teacher identities. Arts-based educational research is a form of arts-based research that utilizes artwork as a means for understanding a particular phenomenon within the context of schooling (Cahnmann-Taylor and Siegesmund, 2017). In particular, arts-based research recognizes the ability of art and artmaking to be generative and meaningful with a comfort in ambiguity and interpretation. Rather than working to build any one particular conclusion, arts-based research “addresses complex and often subtle interactions and […] makes it possible for us to empathize with the experiences of others […] because they create forms that are evocative and compelling” (Barone and Eisner, 2011, p. 3). Arts-based education research as a methodology leans into the richness and complexity of the human experience rather than typical scholarly efforts to isolate and explain particular phenomena. This is not to say that one methodology is better or more important than the other, simply that arts-based education research is well-designed to engage in critical scholarly questions around the experiences, feelings, and complexity of classroom spaces.

TeachSecret project

The project, known to our students as TeachSecret, draws upon arts-based methodologies in three meaningful ways. First, TeachSecret uses the PostSecret phenomenon (Warren, 2005) as a model for generating meaningful artmaking experiences. The PostSecret project allowed artists to submit their contributions to strangers via anonymous postcards (visit www.postsecret.com for more examples). By broadly ensuring that the artmakers’ privacy would be protected, this project allowed space for artmakers to create and share experiences and feelings from their lives that they would not normally be willing to share publicly, even if it was an experience or feeling with which others would likely empathize. Additionally, PostSecret provided space for artmakers to create using the resources available to them with little external pressure to achieve a particular quality or aesthetic that may have hindered artmakers from creating in the first place. Because artwork was sent to an anonymous curator with no specific guidelines for content and quality (other than “tell me a secret”), artmakers were afforded unparalleled space to create as they saw fit, rather than feeling any particular pressure to “be an artist” or create “artwork.” Using the PostSecret project as a mentor text, we developed an open-ended artmaking prompt with non-evaluative latitude for teacher candidates to create artwork however they saw fit using whatever modes and mediums made sense to them. While submitting artwork anonymously in a classroom setting is challenging, we also worked to collect and share artwork for class reflection with anonymity in mind, so even though teacher candidates would be viewing and responding to each other’s artwork, they would not necessarily know whose artwork they were responding to unless the artist had chosen to identify themselves.

Second, TeachSecret draws upon arts-based methodologies by allowing teacher candidates to generate and respond to a complex phenomenon through a range of modes. One of the key affordances of arts-based education research is that it provides opportunity for inquiry and scholarship “to become more reflective on the magnitude of entanglement in which we operate” (Cahnmann-Taylor and Siegesmund, 2017, pp. 4,5). While teacher educators recognize that teacher candidates experience a range of emotions as they engage in coursework and field experiences toward licensure, there is typically limited opportunity within teacher education programs for teacher candidates to share and reflect upon those experiences in deep and complex ways. Additionally, teacher candidates may in fact feel wary of sharing their feelings and experiences because they may fear that it will reflect poorly upon themselves and may negatively impact their standing within the education program. By asking teacher candidates to be artmakers, and by prompting them to create artwork that is both open-ended and anonymous, the project utilizes arts-based research to both recognize the complexity of teacher candidates’ experiences as well as to provide a safe venue for teacher candidates to engage in challenging and potentially uncomfortable conversations around their experiences, while also validating those experiences as real and worthy of discussion.

Finally, TeachSecret utilizes arts-based methodologies because engaging teacher candidates as artmakers creates space for candidates to share their feelings and experiences beyond the limitations of language and prose (Barone and Eisner, 2011). Though teacher candidates are often asked to produce written text and reflections around their experiences, it is possible that such texts are time-consuming, cumbersome, and evaluative in nature because they are often produced with a specific audience and purpose in mind (e.g., evidence of growth toward a particular objective). In the case of TeachSecret, we wanted to create a space where teacher candidates could meaningfully share their feelings and experiences as teachers without the limitations and expectations of a “course project” or “assignment.” Rather, our hope was that by providing open-ended and anonymous responses through a wide range of modes and mediums, teacher candidates would feel better able to create a response that was both meaningful and free of the burdens associated with typical coursework. Just as modeled by the PostSecret project, artmaking provides many opportunities, both textually and visually, for the artmaker to create and share their thinking and feeling in a way that makes sense to them.

Utilizing arts-based methodologies supports both the creation of the TeachSecret artwork and also the utilization of the artwork for drawing meaningful interpretations about the experiences of teacher candidates as they move through their education programs. In this case, the creation of artwork provides special affordances for reflecting upon and understanding complex perspectives and experiences, such as those tied to identity, because artwork inherently offers opportunities to reflect, create, and interpret nuanced understandings that might be lost or withheld during typical discursive classroom practices (Barone and Eisner, 2011). Indeed, the artwork created for this project, and the visual arts in general, provide windows and mirrors into the experiences of others in ways that allow the creator and observer to make and interpret freely—to literally see—using a wide range of tools and means for expressing their thinking and feeling (Leavy, 2015). In the TeachSecret project, artmaking and reflection has provided meaningfully opportunities for both the artmakers themselves and the project curators to better understand the experiences of teacher candidates as they engage in their teacher preparation programs and the wide-ranging feelings and emotions associated with those experiences.

Context

This cross-institutional study explores how arts-based reflections might support teacher candidates enrolled in one of two small, 4-year, university-based teacher preparation programs in the American Midwest. For the purpose of this study, Laura and Kaitlin served in dual roles. First, we were both course instructors working directly with the teacher candidate artists. Second, drawing inspiration from methods of teacher research (Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 1993), we were also researchers of our own practice, deeply embedded in reflecting upon our own pedagogies and the effectiveness of our curriculum and instruction for supporting the growth of teacher candidates. At our cores, we believe in the power of arts-based practices that are both scholarly and pedagogical, and we believe in the importance of creating space specifically for teacher candidates to explore and reflect upon their teacher identities because we see this process as being closely tied to their success and resilience as educators. This project, in very messy and complex ways, is our attempt at bridging our scholarly, pedagogical, and teaching commitments.

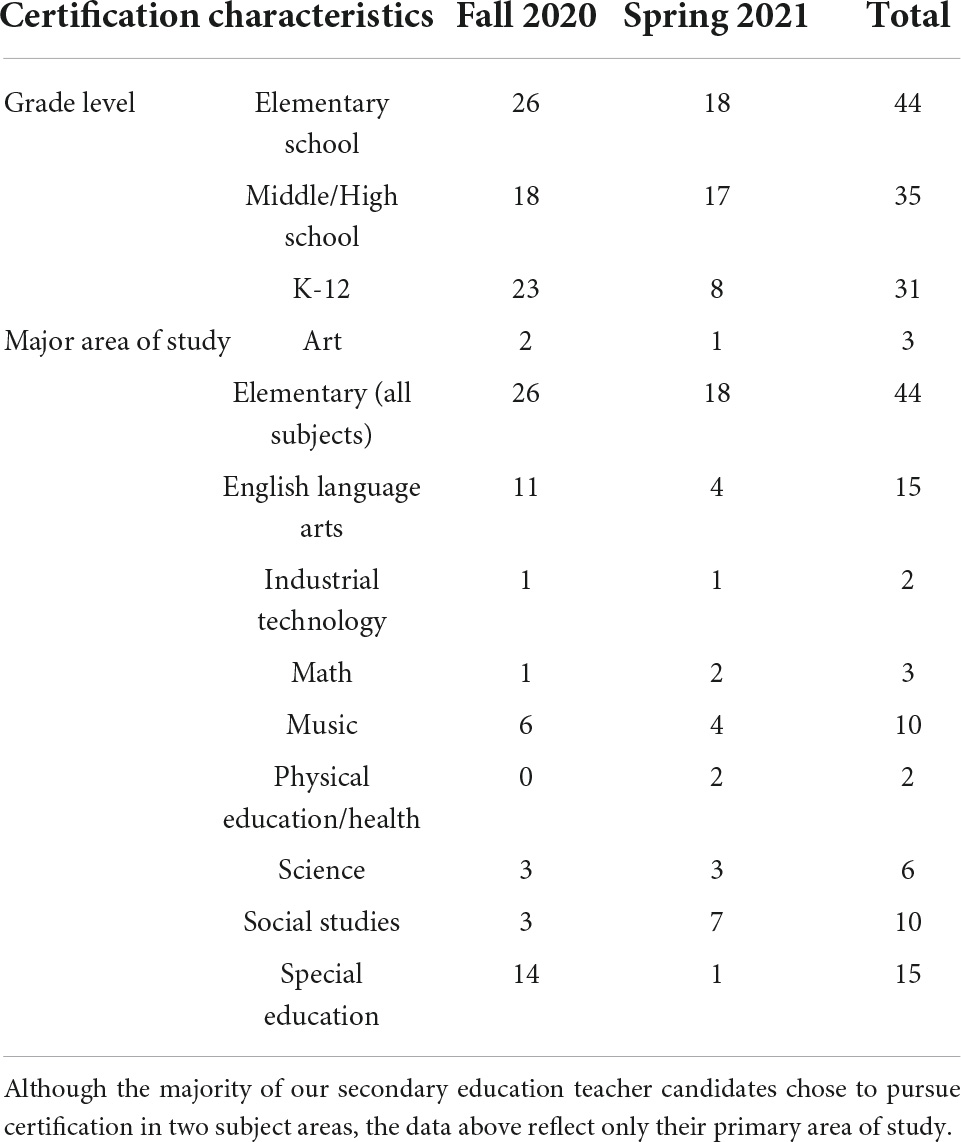

In this project, teacher candidates were the artmakers who both generated and interpreted pieces of visual art as part of their coursework in an undergraduate teacher preparation program. Over the course of the 2020–2021 academic year, 110 teacher candidates from across the two institutions participated in TeachSecret. While most were student teaching in local K-12 school districts when they created their artwork, a handful of artists were engaged in pre-student teaching coursework and corresponding field experiences. Collectively the 110 artists represented a full range of potential grade level placements (e.g., elementary, middle, and high school) and content area foci (e.g., math, physical education, English language arts, special education, music, etc.). Table 1 provides a few key demographic details regarding the teacher certifications our teacher candidates were pursuing.

Data sources

We, the researchers and instructors of record for the teacher candidate artists’ courses, felt strongly that all teacher candidates should reflect on their experiences and feelings as emerging educators, which is why the artwork and subsequent written reflections created were designed as part of the teacher education curriculum rather than being generated outside or in addition to the program. That said, both the artwork and written reflections were graded based on completion only, and teacher candidates had the option of withholding their artwork, their reflection, or both from the research study’s data set. Hence, the number of artwork and written reflections collected are not identical, nor do they match the number of teacher candidates enrolled in our courses. Overall, we collected 1151 pieces of artwork and 112 written reflections from 110 students during the 2020–2021 academic year.

Artwork

As described above, each of the teacher candidates created visual artwork based on the following prompt:

Taking inspiration from PostSecret (Warren, 2005), you will anonymously share a secret about your (emerging) teacher identity. This secret can represent a moment of vulnerability, victory, fear, laughter, regret, or desire. Reveal anything as long as it speaks to your experiences as a(n emerging) teacher. Use any artistic representation that fits onto a half sheet of paper: collage, poetry, prose, mosaic, sketch, tweet, comic, meme, etc.

We provided teacher candidates with sample artwork to model the different modes and mediums available to artists during their artmaking. These samples came primarily from the PostSecret project (Warren, 2005); however, in the spring of 2021, we also provided artists with a handful of TeachSecret examples created by Fall 2020 teacher candidates.

While the prompt was the same at both institutions, there were a few key differences in the implementation of the activity. Teacher candidates at Laura’s institution were enrolled in a fully online course during student teaching. Thus, artists had to supply their own materials, and all artmaking occurred on the candidates’ own time. For the teacher candidates at Kaitlin’s institution, classes were held in person during the 2020–2021 academic year. Kaitlin provided candidates with materials—paper, colored pencils, markers, scissors, etc.—to use, though artists were welcome to use any tools or technologies that they saw fit. Their artwork was generated through a combination of in-class and outside work time using the prompts and materials described above. In a few cases, teacher candidates created more than one piece of art during the course of the semester: one piece before engaging in a live teaching experience and one after engaging in a live teaching experience.

Reflections

After teacher candidates submitted their artwork, we anonymized each piece and uploaded the artwork into a slidedeck. Candidates then had the opportunity to view their peers’ anonymized art through this virtual art gallery, where they were asked to answer the following prompt:

Take a few minutes to review your peers’ anonymous artwork. Choose the artifact that speaks to you the most. It may be one that reaffirms your experiences; it may be one that challenges you to see your experiences in a new light. Either way, reflect on the ways in which you are drawn to this particular piece.

This written reflection had no set parameters; some teacher candidates wrote a few sentences; others submitted as many as two or three pages. Generally speaking, teacher candidates would write about one particular piece of art that stood out to them for a number of reasons: they found it visually and aesthetically appealing; they empathized with the content of the artwork; and/or the artwork raised questions for them that they wanted to explore further. These written reflections were submitted to course instructors as part of teacher candidates’ coursework.

Data analysis

While a detailed discussion of the ideational, interpersonal, and/or textual resources apparent within teacher candidates’ artwork is certainly warranted, it is beyond the scope of this particular article. We, instead, position the visual art as a catalyst for sparking reflective dialogue among the candidates, and it is the response elicited by the artwork—in the form of written reflections submitted by the artists’ peers—that we center here. That said, drawing on Kress and van Leeuwen’s (2020) descriptive framework of reading images, we considered each artist’s aesthetic choices (e.g., color versus grayscale, found photos versus hand drawn, etc.) as well as their interpretable content (e.g., the visuals, graphics, and/or text, etc.) as an important step in the first phase of a six-part analytic process.

We used thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Clarke et al., 2015) to make sense of the artifacts generated during this study; we engaged in familiarization, coding, searching, reviewing, defining, and writing about the themes addressed within the artwork and reflections. To begin, because this study was conducted across two institutions, it was critical that we spent time familiarizing ourselves with the data set. Each author reviewed the artifacts independently, noting both aesthetic choices and interpretable content within the artwork as well as key ideas within the written reflections. As we reviewed artifacts, we wrote brief memos about our noticings.

Once both authors were familiar with the data set, we met to code the data and search for, review, and name themes. Codes included, but were not limited to, anxiety, time, worry, fatigue, trust, conflict, purpose, and commitment. Using a spreadsheet to track not only which codes applied to which artifacts but also whether the teacher candidate’s artifact addressed the code in a negative, neutral, or positive way, we were able to begin to identify themes within the data set. While most codes were strictly sorted as either positive or negative in their connotation, the code of time, for example, was not so straightforward. In some instances, teacher candidates shared they felt behind without enough time or energy in the day to catch up. But other teacher candidates addressed time in a positive way; their artifacts referenced the candidates’ growth over time. When organizing codes around emerging patterns, we initially noted trends in the data regarding shared experiences (mirrors) or new perspectives (windows). However, not all data fit neatly into one of these two themes; we needed a third theme: dissonance. This third theme speaks to the perceived disconnect between teacher candidates’ university-based coursework and their field experiences in K-12 classrooms.

In the “Findings” and “Discussion” section, we offer our interpretations2 of these three themes using the artwork and subsequent written reflections to illustrate and contextualize the lived experiences of our teacher candidates.

Findings

When reviewing the artifacts (i.e., visual artwork and written reflections) generated by the teacher candidates across our two institutions, we noted that the artwork addressed a wide range of topics including references to instructional tasks associated with teaching (e.g., lesson planning, grading, facilitating online learning, etc.); the relational work of building community with students, families, and staff; the juggling of myriad responsibilities; and the emotional work of developing confidence, professionalism, and a sense of belonging.

More specifically, our analysis of candidates’ artwork and reflections revealed three key findings. First, candidates used TeachSecret as an opportunity to enter into challenging conversations around perceived moments of dissonance between their experiences in the university’s teacher preparation program and their experiences working within a K-12 school setting. Second, while the artwork addressed a wide array of themes, the written reflections were far more focused. When given the opportunity to select one piece of art as inspiration for their reflection, teacher candidates gravitated toward the artwork that provided emotional mirrors into their own experiences. Third, in some cases, candidates’ artwork served as windows for their peers to frame and/or interpret their student teaching experiences in a new light. Each of these findings will be discussed in greater detail below.

Artwork as dissonance

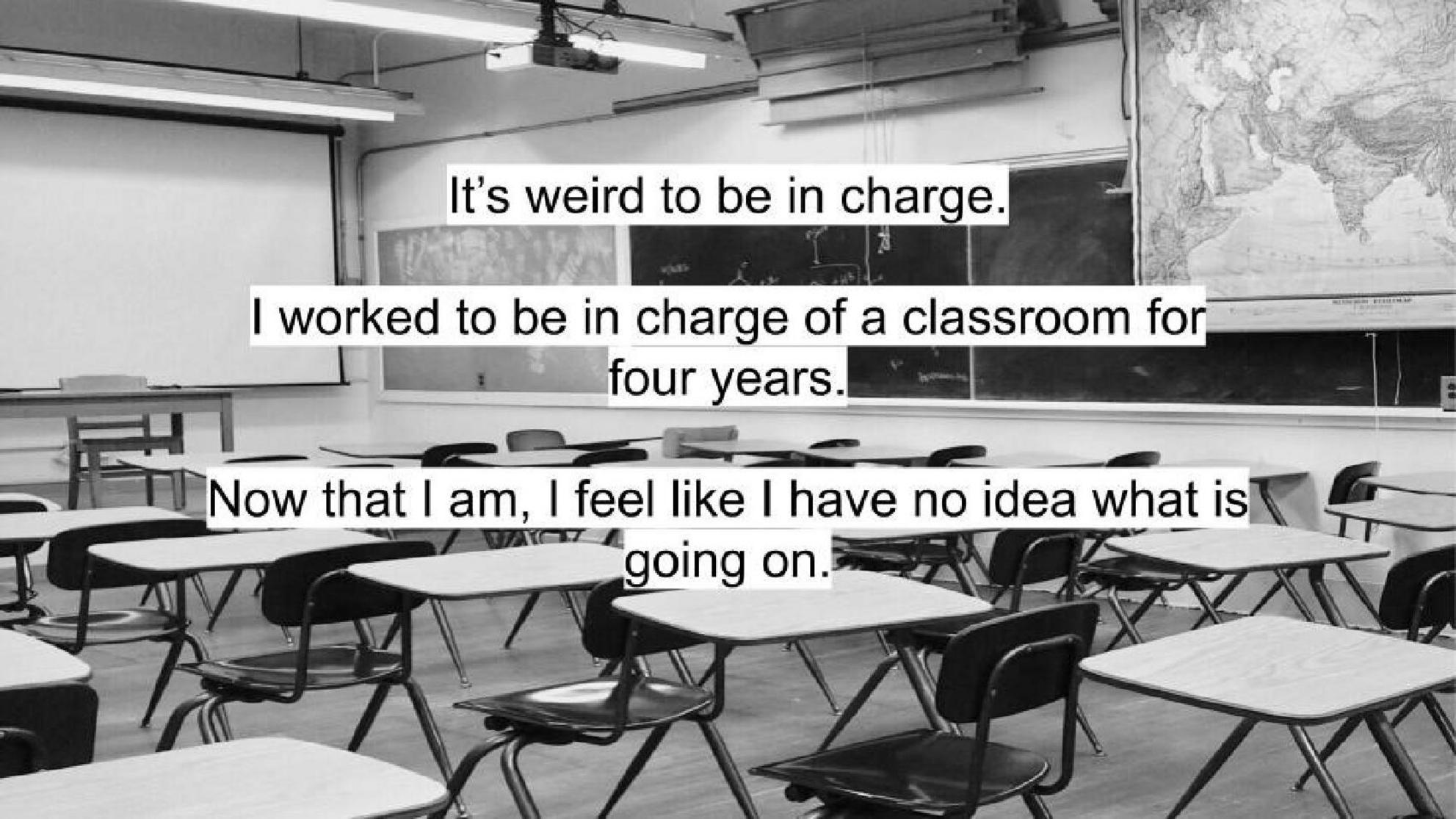

A number of pieces in the virtual art gallery spoke of noticeable shifts in identity, responsibility, and/or philosophy when moving from the university’s teacher preparation program into the K-12 classroom. Candidates used the reflective activity—both the making of visual art and the written reflection—as an opportunity to call attention to the perceived dissonance between the two spaces. For instance, Figure 1 features a grayscale image of a classroom in the background with the following sentences in the foreground: “It is weird to be in charge. I worked to be in charge of a classroom for 4 years. Now that I am, I feel like I have no idea what is going on.”

In this case, the artist used an empty, traditionally arranged photo of a classroom, which is evocative of the quiet time at the beginning of the school day, right before students enter the room and learning begins. At the same time, the artist superimposed contradictory text on top of the picture. While the picture might portray an organized room that is “ready to go,” the text itself suggests that the artist felt woefully unprepared to begin even if they present a competent external image. In this artwork, there seems to be a sharp contrast between the way the teacher is perceived on the outside versus how they are feeling on the inside.

This contrast and visual dissonance was noted in teacher candidates’ reflections. For example, a teacher candidate responded to this piece of artwork, writing:

It is weird to be the one that the students look to for all the answers. I was only a student not too long ago. […] School does not prepare you for the chance to be completely in charge of a classroom and it is a weird thing to get used to.

As shown through this reflection, the artwork, “It is weird to be in charge,” (Figure 1) resonated deeply with the lived experience of this teacher candidate, who is also challenged by the experience of taking over classroom responsibilities. In this case, the artwork allowed the teacher candidate to name their feelings (“it is a weird thing to get used to”) around the experience of “being completely in charge of a classroom.” Additionally, both the artist and the reflecting teacher candidate point to the fact that, while they have been experiencing classrooms for a long time, both as students and as teacher candidates, there has never been a time, up to this point, where they fully felt the responsibility of being the leader. This increased level of responsibility catalyzed the teacher candidate’s feelings of uncertainty and disequilibrium, as highlighted in the artwork and reflection.

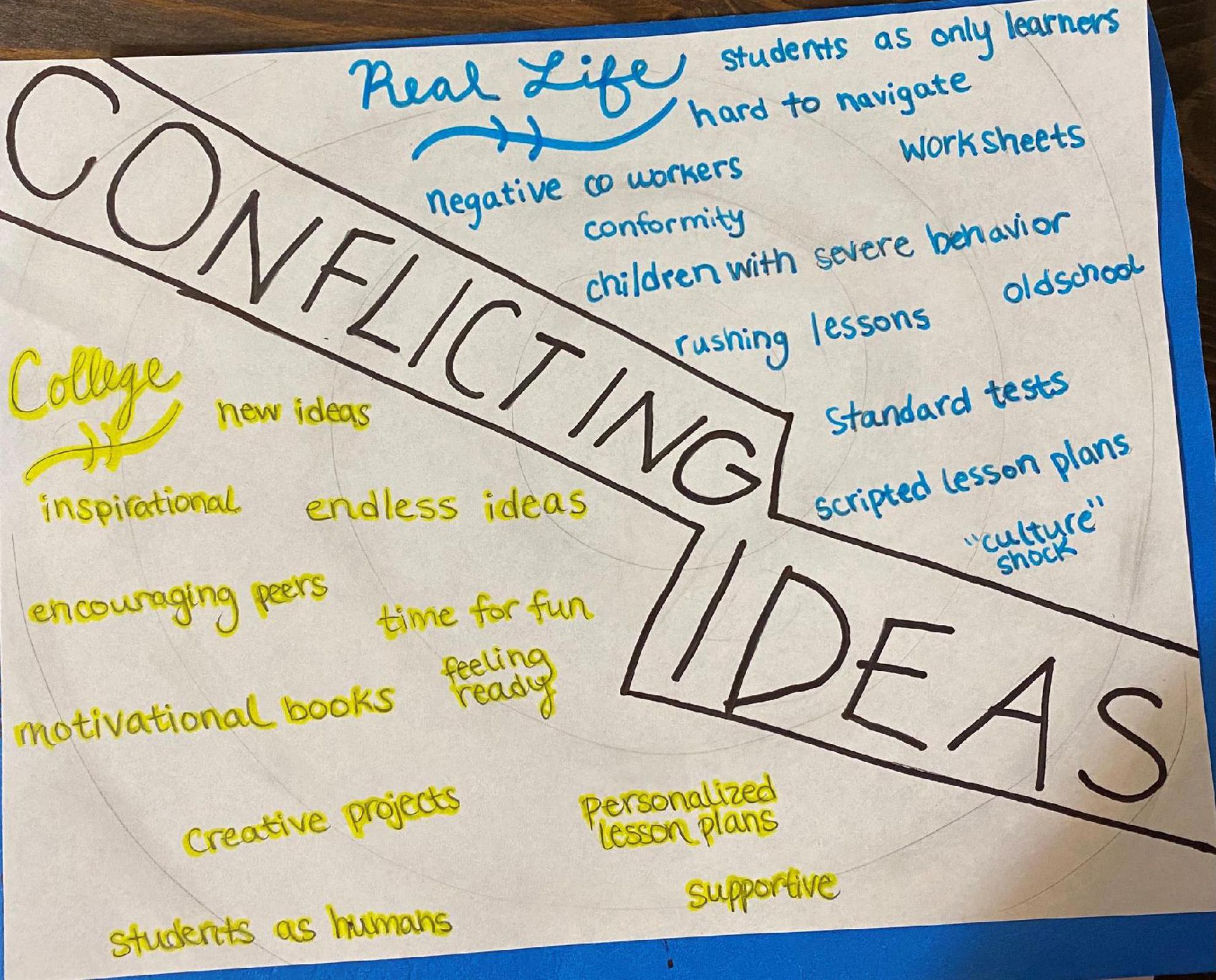

Other teacher candidate artmakers reflected upon the dissonance between their teacher preparation program and their experiences out in the field in more concrete ways. For example, in Figure 2, “Conflicting Ideas,” the artist created a piece of artwork that utilized multi-colored text to draw a stark contrast between their experiences. At the top right of the page, the artist used a blue marker to illustrate the experiences of “Real Life” (e.g., hard to navigate, negative co-workers, standard tests, and rushing lessons). At the bottom left of the page, the artist used a yellow marker to illustrate the experiences of “College” (e.g., new ideas, encouraging peers, motivational books, and personalized lesson plans). In between the two sections, in bold, capitalized text written in black marker are the words: “Conflicting Ideas.”

This artwork creates both a visually stark divide between the artist’s perceived experiences in the “real world” of a K-12 classroom versus their experiences engaging in teacher education through their college classroom. Additionally, the artist utilized language in the two sections that was in direct contrast across the “conflicting ideas” divide, including language such as: “encouraging peers” versus “negative coworkers,” “creative projects” versus “standard tests,” and “students as humans” versus “students as only learners.” In this example, the artwork draws a sharp and compelling contrast between what can be described as the rosy nature of teaching and learning in college versus the harsh reality of teaching and learning in a K-12 setting, with clear dissonance and disequilibrium between the two.

This clear contrast between the perceived realities of the college classroom versus the K-12 classroom was also the catalyst for a number of written reflections by teacher candidates. For example, one teacher candidate reflected that:

I am truly confused about why what we are taught in our college classes differs greatly from the reality of teaching and what actually happens. […] I hope to be different than [my mentor] with my teaching style and change and design my classroom in a way that allows for these concepts to come to life. I fully believe in the benefits of inquiry, multi-sensory learning, and hands-on activities. I just wish I could experience these things in my student teaching.

In this reflection, the teacher candidate is especially interested in not just recognizing the divide between their experiences in the collegiate versus K-12 classroom, but in finding ways to bridge the divide between the two. While this teacher candidate does not necessarily see this divide as an insurmountable obstacle (“I hope to be different…” and “I fully believe in the benefits…”), they are also illustrating the perceived lack of flexibility that has stood in the way of their growth through student teaching (“I just wish I could experience…”). For this teacher candidate, it is not simply that there are stark contrasts between their collegiate learning and their K-12 teaching, it is that their experiences in their student teaching have not provided direct avenues for them to speak back to or work around the negative realities witnessed in their preparation program. This theme was echoed by another teacher candidate, who also responded to Figure 2 by writing:

I found that student teaching has shown me some harsh realities. The more I teach, the more I have to try to balance blind optimism from my college courses with the harsh cynicism I hear at school.

In this reflection, the teacher candidate is also thinking through how to move through and around their dissonant experiences between their teacher preparation program and the K-12 school system. However, rather than viewing the dissonance as an either/or, this teacher candidate reflects upon their efforts to live within the realities of both (“I have to try to balance…”). In both reflections, the artwork and reflections generated by teacher candidates stimulated conversations about the deep unease felt by teacher candidates as they try to find equilibrium between two potentially contrasting realities.

Artwork as mirrors

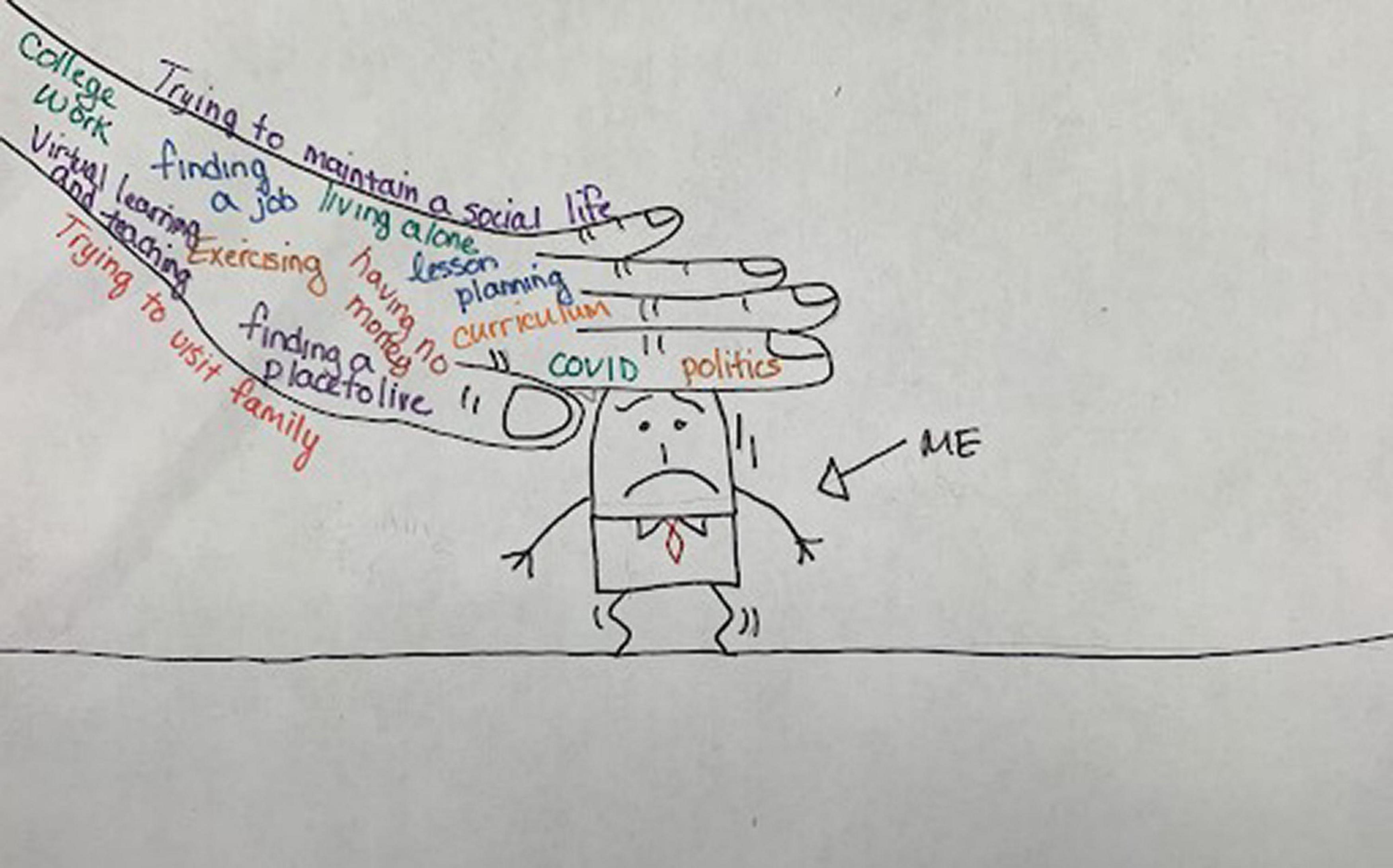

As one of our candidates explained it in their written reflection, “it is crazy to be living the life of student at [my university], teacher to my students, and student to my mentor” (emphasis added). If that was not enough to manage, add to the mix their many other possible identities, including child to an aging parent, partner in a new relationship, parent to one or more children, part-time employee with evening and weekend shifts to pay their rent, advisor for a school club, coach of a youth sports team, military reservist, etc. It is a wonder how they can juggle all of these identities without dropping the proverbial ball. Looking across the 115 pieces of artwork, we see some recurring metaphors and imagery related to the managing of multiple professional and personal identities. There were clowns tossing a half dozen or more balls in the air; tightrope walkers struggling to maintain their balance; scales with professional responsibilities far outweighing personal ones; and images of teacher candidates being crushed, overrun, or hanging precariously over a precipice.

These pieces and their messages of struggle, perseverance, and survival served as mirrors reflecting other teacher candidates’ own emotional experiences as evidenced by their written reflections. Take Figure 3 as an example; it depicts an individual feeling the weight of multiple responsibilities (e.g., lesson planning, politics, financial insecurity, COVID-19, etc.) on their head. The artist included details such as shaking knees and beads of sweat to further emphasize the gravity of the situation.

Of the 67 pieces of artwork created in the Fall of 2020, Figure 3 was the piece most often responded to in our candidates’ written reflections. As one candidate shared, “I feel a deep connection to this art because I feel [the pressure] on a daily basis.” It was a feeling that our candidates knew all too well, with some candidates wondering whether or not they could endure the pressure. As another candidate wrote:

I feel like the kid who was dropped off at school for the very first time and told “have a great time”. I am, but what is the cost and is there a safety net anywhere? […] The hand just keeps smashing down. Will it mold me into a teacher, or smash me like a bug?

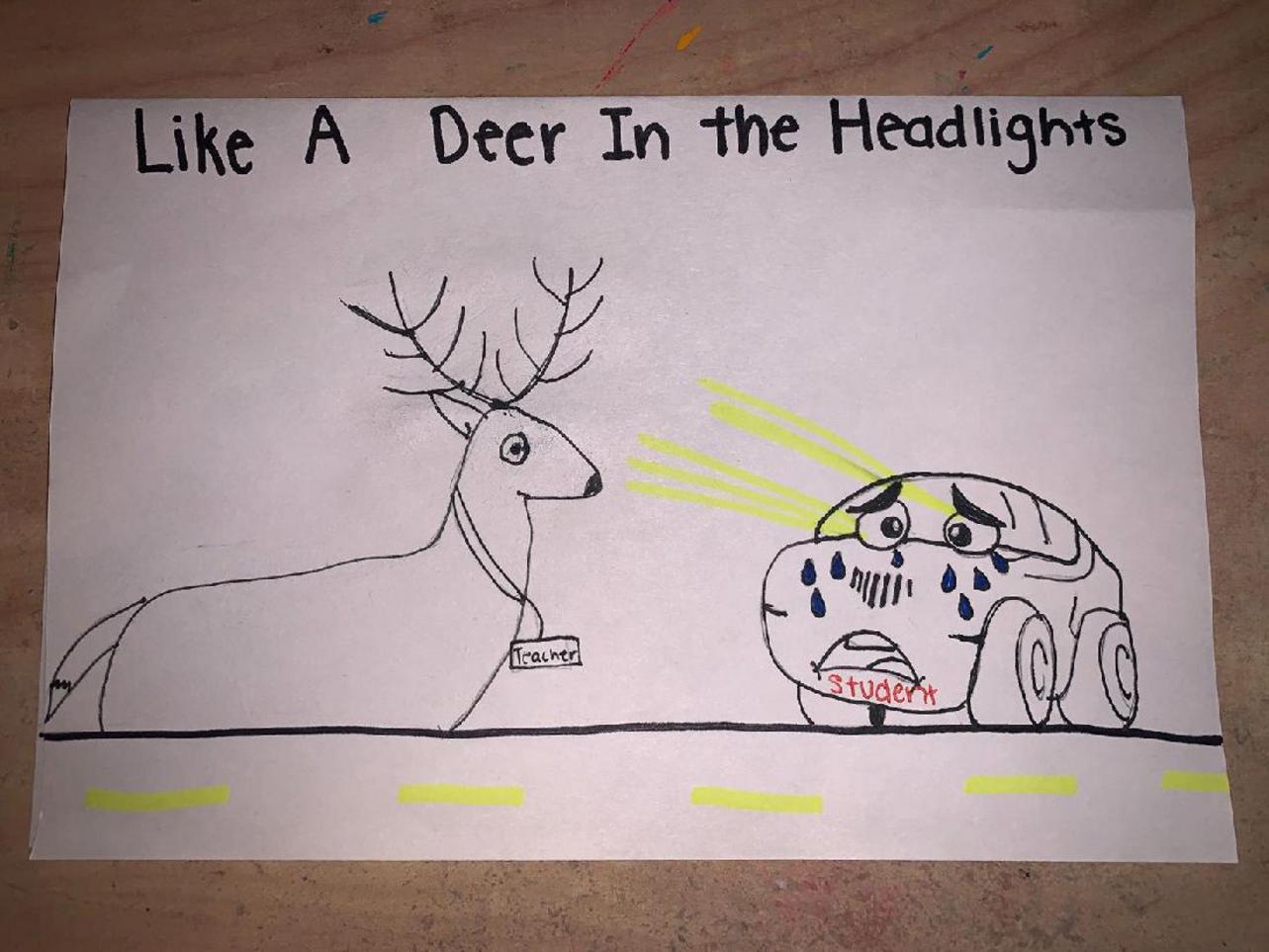

Figure 3, and many other similar pieces reflected teacher candidates’ feelings of being crushed by the weight of the global pandemic and the sudden shift to remote instruction on top of the typical student teaching experience. However, not all pieces mirroring the emotional intensity of student teaching addressed the ongoing pandemic. Take Figure 4, for example; it depicts a vehicle, labeled “student,” with its headlights on and what appears to be either tears or sweat streaming down the front of the vehicle. In the road ahead stands a deer wearing a nametag that reads “teacher.” The caption above the image reads “Like A Deer In the Headlights.”

As a mirror reflecting shared student teaching experiences, viewing this piece of art prompted one candidate to share that they experience this feeling of being a deer in the headlights on a daily basis, writing:

I know I am the deer. I feel like everything I do in my personal and professional life is just so busy that when I am paying attention to one, another one sneaks up on me. I am constantly dodging different cars on the same road. I feel like the same cars come by every single day but will not slow down for me.

While Figure 4 served as a mirror for many of our candidates, for two candidates, it was something else. As one candidate explained, “I knew the deer would be the student teacher, but I never thought the car would be the students. […] I feel like the car could have been anything, but to make it a student was not what I was expecting.” Similarly, another member of the Fall 2020 cohort observed, “the students look nervous in this image; however, I feel that this experience has been the opposite. I am the one that has been nervously sweating, hoping that I am doing what is best for my students.” For these two candidates, Figure 4 created an opportunity to imagine student teaching from a K-12 student’s point of view. Was the student teacher the only one who was nervous, or were their students feeling similarly uneasy? This brings us to the third finding of our work: artwork as windows.

Artwork as windows

Some of the pieces of artwork created for the virtual art gallery served as windows into either different experiences or alternative interpretations of similar experiences. These windows invited teacher candidates to consider their experiences from another perspective, to reframe their thinking, to reinvent their story of learning to teach. Figure 5, for example, reads “I am just a person. I learn. I grow. I fail. I try. I teach. I inspire. I struggle. I discover. So do you. Let’s do it together.” Note, the artist addresses the audience as simply “you” in this piece. In their written response to Figure 5, one teacher candidate understood this piece as “I [student teacher] talking to you [student]”, writing:

One [piece of art] that challenged my perception was the first submission when it talked about teachers and students working together to get through challenges. I never really thought about teachers and students working together to learn from each other. In the past teacher and student relationships have consisted of students learning from teachers and not necessarily the other way around.

For the author of the reflection above, the artist of Figure 5 pushed their thinking in an important way; the candidate who authored the reflection left the virtual art gallery wondering if there was more to the teacher-student relationship than they had previously understood. Could teachers learn either from or alongside their students?

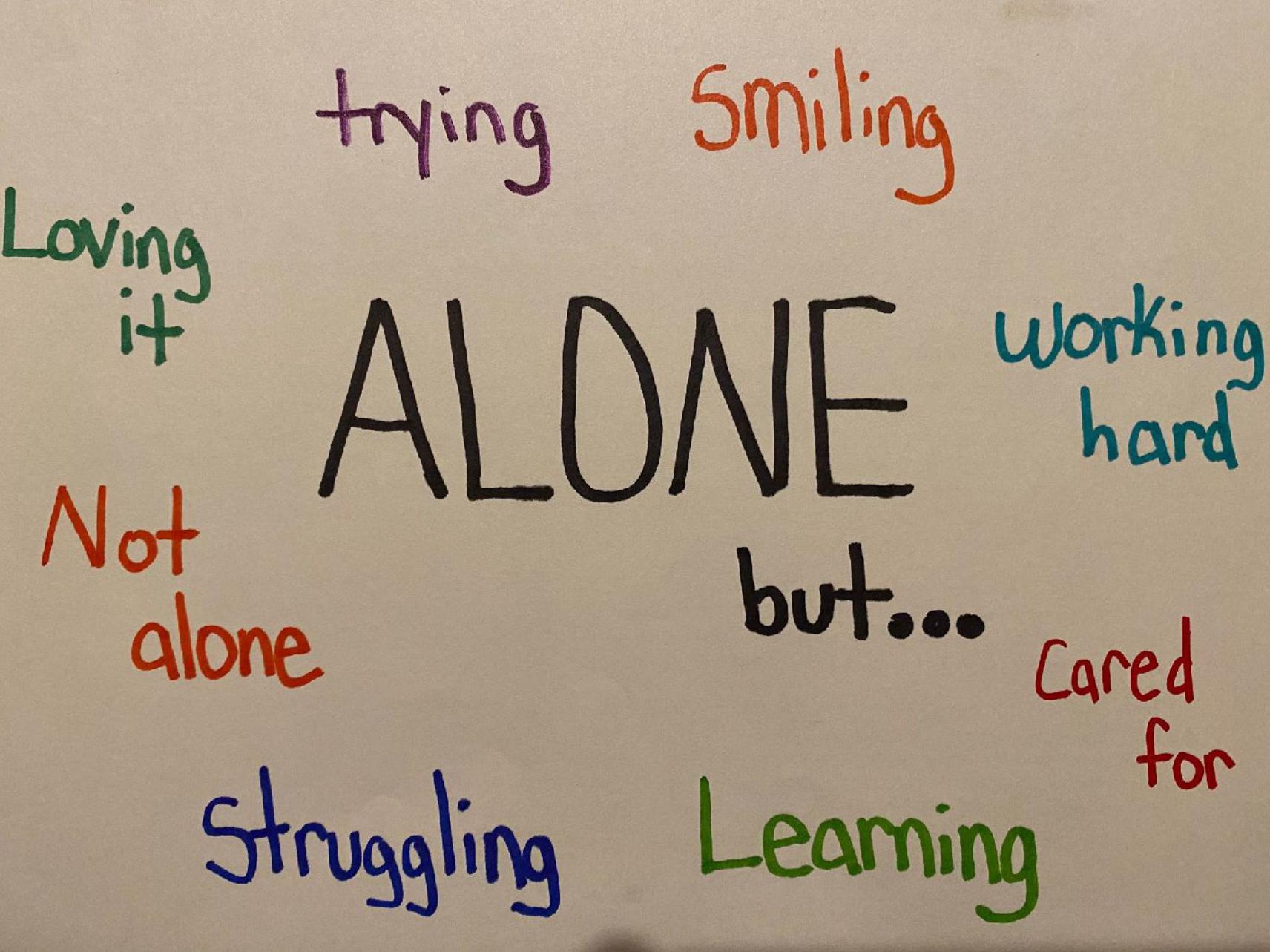

Artwork like Figure 5 challenged teacher candidates to reimagine the role of a teacher. Another collection of artwork encouraged candidates to reframe their experiences from an asset perspective, focusing on the positives rather than the negatives. For example, as you may recall, Figure 3 featured an individual’s knees shaking under the pressure of many responsibilities: remote instruction, financial insecurity, lesson planning, etc. While the artist of Figure 3 was feeling the weight of student teaching when they created their sketch, when they visited the virtual art gallery 1 week later, another artist’s work challenged them to reconsider their position. Figure 6 features the words “ALONE but…” in the center of a page with a series of words and phrases evenly spread around the border. Beginning at the top and continuing clockwise around the page, the piece reads: trying, smiling, working hard, cared for, learning, struggling, not alone, and loving it.

In response to Figure 6, the artist of Figure 3 shared that the piece resonated with them because:

It is almost the complete opposite of my own. My piece was made in regards to the many pressures and responsibilities I am facing and feeling at this moment in life. This piece, in contrast, really makes me reflect on all the positives in my life. I may feel alone in navigating the many unknowns during this time. I may feel like I am drowning, or feel that I have no idea what to do next, but I do have a loving, supportive family, supportive peers, and a welcoming environment in which I am teaching.

Figure 6, and other pieces like it, offered a lifeline to teacher candidates who were struggling in their student teaching placements. As another candidate wrote, “it is so easy to feel alone while on this path of becoming an educator,” but “as alone as I feel on this journey, I need to remind myself that […] I am trying my very best and smiling while doing it.” These messages of affirmation, seen both in the artwork and in the teacher reflections were an important window for many teacher candidates to reflect upon the positive and uplifting emotions many teacher candidates were feeling during their programs. For these teacher candidates, engaging in artmaking and reflection provided both opportunities to articulate the strain and anxiety of their work while also recognizing it as a worthwhile and uplifting endeavor.

Discussion

Inspired by scholars who have recently explored drawing, collage, self-portrait, and other visual art forms as research tools (e.g., McKay and Barton, 2018; Culshaw, 2019; Holappa et al., 2021), this study asked: Knowing that professional identity work is part of the hidden curriculum of a teacher candidate’s student teaching experience (Britzman, 2003), how might an arts-based reflection help candidates to express their thoughts, feelings, and actions regarding this often invisible process of learning to teach? In keeping with Holappa et al.’s (2021) work into student teacher vulnerability, our teacher candidates, especially candidates who had a challenging student teaching experience, benefited from the opportunity to express these challenges in a low risk environment through anonymized artwork. As one candidate shared in a written reflection about the activity:

At first, I thought it seemed like humdrum busywork that I did not really want to do. […] It turned into a great reflective and self-developing experience. […] The assignment permitted me to unleash how I genuinely feel about becoming a teacher. Seeing the artwork led me to discover that I do not have one prominent feeling about my journey toward becoming a teacher, rather I am overwhelmed by an influx of feelings. My mind is spinning at a mile a minute.

As the candidate above explained, the opportunity for teacher candidates to view and respond to each other’s artwork was an important component in this study. In some reflections, candidates framed the artwork as windows into student teaching experiences unlike their own. However, most reflections addressed the mirroring of difficult emotions. One of the Fall 2020 student teachers explained it this way, “Looking at this [artwork] made me feel a lot better about myself. I thought I was the only one who [felt] kind of lost and confused.” The virtual art gallery created space for teacher candidates to recognize that they were not alone in their emotions and experiences; their peers were feeling similarly inundated. As McKay and Barton (2018) suggested, “without this process, the teacher [candidate]s may have remained as silos, each trying to survive independently of one another” (p. 364).

Vulnerable and reflective discussions of the emotions associated with teaching often go overlooked in teacher education programs, and even with practicing teachers as well. Most teacher education curriculum focuses on building strong theoretical and practical knowledge about pedagogy and responsiveness to the needs of students. However, as shown through these artwork and reflections, teacher candidates crave, whether they initially realize it or not, the opportunity to acknowledge, reflect upon, and discuss not just their experiences, but also how those experiences make them feel about themselves and the work that they do in the classroom. These strategies for recognizing and responding to the intense emotions of learning to teach may also support teacher candidates as they enter their first years of teaching. Research has consistently shown that teacher burnout is high for beginning teachers (e.g., Perrone et al., 2019; Pressley, 2021); a teacher’s deteriorated sense of engagement with one’s work, if not addressed, can eventually lead to the teacher leaving their current school or the profession altogether. In fact, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, close to 8% of teachers were leaving the profession each year, with new teachers (<5 years) leaving at rates between 19 and 30% (Learning Policy Institute, 2018). In the midst of a nationwide teacher shortage, our experiences with the TeachSecret project have led us to the conclusion that these sorts of emotional and experiential discussions and reflections with teacher candidates must be an integral part of teacher preparation programs, both so teacher candidates recognize their feelings and see that they are not alone in their experiences, but also so that teacher candidates can develop coping strategies and tools for responding to those emotions in beneficial and empowering ways. While there are many ways to engage in these complex conversations, as teacher educators, we have found the creation and dissemination of anonymous artwork has been a meaningful way for teacher candidates to share, consider, and respond to their experiences and the experiences of others.

Additionally, the dichotomy between teacher candidate’s experiences in the field versus experiences in methods classes also raises questions about the role of teacher educators. While teacher educators want to provide the most up-to-date best practices and models for effective classroom instruction, it does lead to questions about what to do when those best practices and/or models are in conflict with what teacher candidates are experiencing in schools. The TeachSecret project affords teacher educators and mentor teachers with the opportunity to reflect upon the emotional dissonance between methods courses and field placements, so that they can play a more active and effective role in ensuring that teacher candidates have opportunities to reflect and ask questions, but also to find synergy between their courses and placements.

The TeachSecret project is one that we see serving several purposes. It has been an opportunity for us, as teacher educators, to build meaningful reflections of teacher identity into our teacher education curriculum to the benefit of our students. Additionally, it has allowed us to curate a large collection of teacher candidate artwork. We see this collection of artwork to be important for two reasons: (1) it allows teacher educators access to a wide range of artwork and reflections that they can use both as models and mentor texts in their own teacher education programs to support students in recognizing, reflecting upon, and building strategies for developing their teacher identity and strategies for coping with the intensive emotional work of teaching; and (2) it provides a collection of windows for mentor teachers and supervisors into the (often unshared) experiences and emotions of their teacher candidates. By viewing this digital gallery, teacher educators, mentor teachers, and student teacher supervisors, can notice trends, common themes, and critical questions in order to decide how to best address these critical issues with their own student teachers (e.g., struggle, burnout, anxiety, etc.). We find these to be important and critical conversations both for the development of teacher candidates and their identity as a teacher as well as for their happiness and longevity as classroom teachers.

Conclusion

The philosophy behind the PostSecret (Warren, 2005) project, which prizes anonymity, truth-telling, and close-cutting identity work, was a particularly important lens for our ABER project, which valued the opportunity for teacher candidates to reflect carefully on their experiences in the K-12 classroom with limited fear of reprisal from their peers. Sharing artwork anonymously allowed the candidates to share meaningfully from their lived experiences in order to feel heard by the broader community while also protecting their potentially vulnerable emergent teacher identities. Similarly, viewing and reflecting upon their community’s artwork provided candidates the opportunity to see their thinking taken up by others while also providing the opportunity to explore windows into the experiences of others.

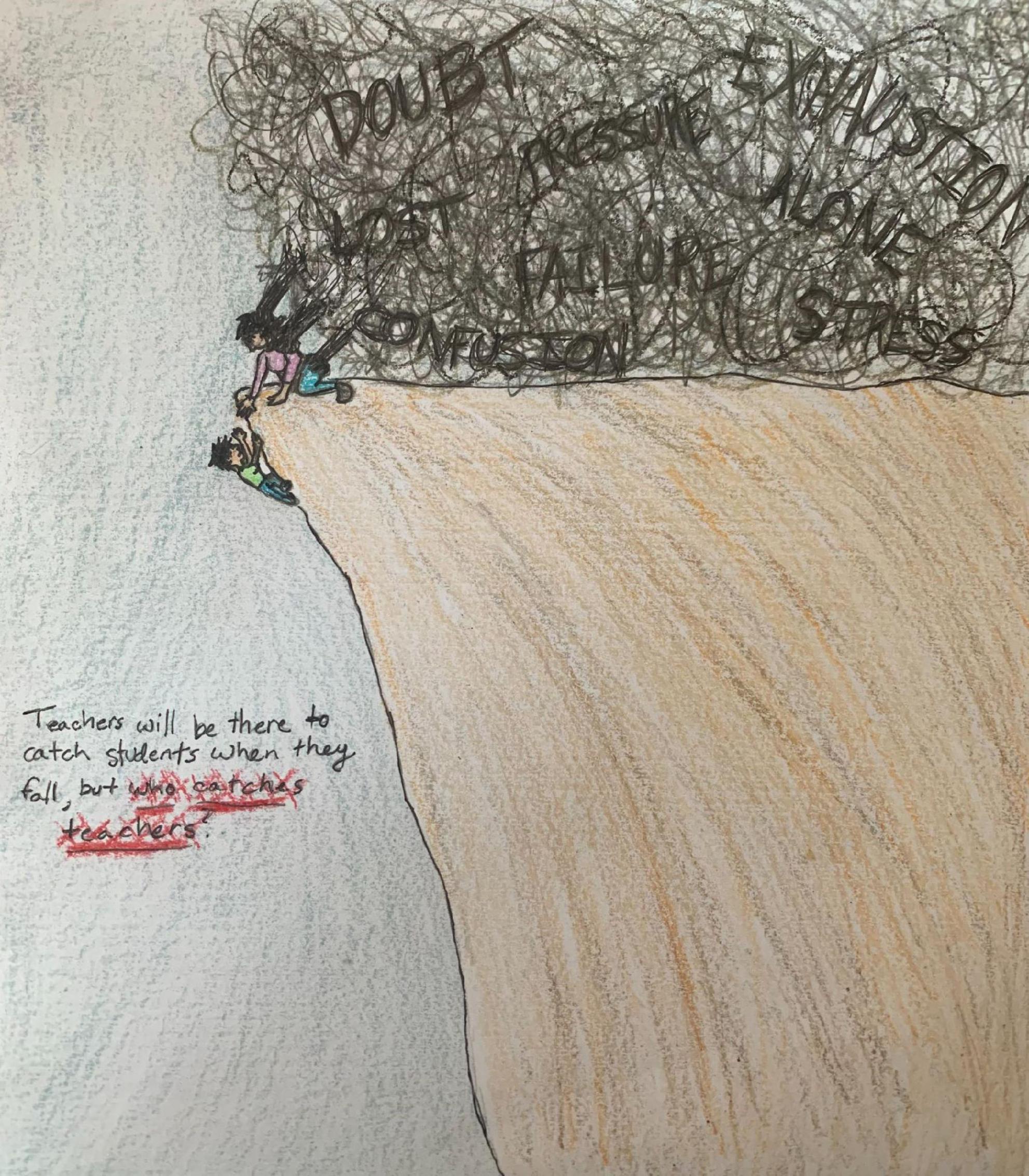

While the teacher candidates greatly benefited from examining their own experiences and those of their peers, we have chosen to close this article by noting that some of the artists posed questions that we, as a community of teacher educators and teacher candidates, could not easily answer. Figure 7, for example, depicts an individual hanging from the side of a cliff with a cloud of doubt and insecurities hovering overhead. The artist asked “Teachers will be there to catch students when they fall, but who catches teachers?” As teacher educators and teacher education researchers, we must ask ourselves not only (1) in what ways do we support teacher candidates in recognizing their emotional journey as they develop an emerging teacher identity, but also (2) how do we create opportunities for teacher candidates to voice these often-difficult emotions? This study suggests that through anonymous artistic representation and reflection, teacher candidates can identify moments of emotional windows, mirrors, and dissonance within their community of emerging teachers. The teaching profession is inherently isolating and lonely for many educators, especially during the ongoing global pandemic (Jones and Kessler, 2020; Ramakrishna and Singh, 2022). Thus it is imperative that we recognize this and respond in empowering and uplifting ways.

To that end, we continue to use TeachSecret as an arts-based reflective activity in our teaching. To date, our teacher candidates have generated nearly 250 pieces of artwork depicting their lived experiences of learning to teach. The following URL will lead you to a jamboard featuring 45 of the most reflected upon pieces created by our teacher candidate artists between Fall 2020 and Spring 2022: https://tinyurl.com/teachsecretartwork. We welcome you to draw on these pieces in order to launch conversations with your own candidates.

Data availability statement

Access to a limited dataset is available within the manuscript. Requests to access the complete dataset should be directed to LK, bGtlbm5lZHlAbm11LmVkdQ==.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Northern Michigan University and Millikin University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LK served as principal investigator (PI), conceptualized the study, secured IRB approval for one of two universities, collected and cataloged data, collaborated with her co-author on data analysis, and took the lead in the writing of the final manuscript. KG served as the co-principal investigator, applied for and received IRB approval for the second university, collected and cataloged data, took the lead during data analysis, and contributed to all sections of the final manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ During the Spring of 2021, teacher candidates in Kaitlin’s course created more than one piece of artwork reflecting on their teacher identity over the course of the semester. Therefore, some participating artists included two pieces of artwork in the TeachSecret project.

- ^ As researchers, we recognize that we viewed and responded to the artwork through the lens of our own experiences as former teacher candidates, practicing teachers, and teacher educators. Our interpretations of the artwork and any findings or conclusions that we draw from them are ultimately based on our subjective understandings, and others who view the same artwork may elicit different interpretations. We do not intend for our interpretations and findings to be the only, or the “best,” analysis. Rather, we include them here as an opportunity to start a conversation around a deeply meaningful time in teacher candidates’ lives.

References

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2017). “Identities as emotioning and believing,” in Reflections on language teacher identity research, ed. G. Barkhuizen (New York, NY: Routledge), 145–150.

Barkhuizen, G. (2016). A short story approach to analyzing teacher (imagined) identities over time. TESOL Q. 50, 655–683. doi: 10.1002/tesq.311

Barone, T., and Eisner, E. W. (2011). Arts based research. Washington, DC: Sage Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781452230627

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 175–189. doi: 10.1080/03057640902902252

Beltman, S., Glass, C., Dinham, J., Chalk, B., and Nguyen, B. (2015). Drawing identity: Beginning pre-service teachers’ professional identities. Issues Educ. Res. 25, 225–245.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Albany, NY: Suny.

Cahnmann-Taylor, M., and Siegesmund, R. (Eds.) (2017). Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315305073

Chen, Z., Sun, Y., and Jia, Z. (2022). A study of student-teachers’ emotional experiences and their development of professional identities. Front. Educ. Teach. Educ. 12:810146. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810146

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Clarke, V., Braun, V., and Hayfield, N. (2015). “Thematic analysis,” in Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods, ed. J. Smith (London: Sage Publications), 222–248.

Cochran-Smith, M., and Lytle, S. (1993). Inside/outside: Teacher research and knowledge. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Culshaw, S. (2019). The unspoken power of collage? Using an innovative arts-based research method to explore the experience of struggling as a teacher. Lond. Rev. Educ. 17, 268–283. doi: 10.18546/LRE.17.3.03

Holappa, A., Lassila, E. T., Lutovac, S., and Uitto, M. (2021). Vulnerability as an emotional dimension in student teachers’ narrative identities told with self-portraits. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 66, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2021.1939144

Jones, A. L., and Kessler, M. A. (2020). Teachers’ emotion and identity work during a pandemic. Front. Educ. Teach. Educ. 5:583775. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.583775

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2020). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003099857

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995a). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Pract. 34, 159–195. doi: 10.1080/00405849509543675

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995b). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32, 465–491. doi: 10.3102/00028312032003465

Lavina, L., Niland, A., and Fleet, A. (2020). Assembling threads of identity: Installation as a professional learning site for teachers. Teach. Dev. 24, 415–441. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2020.1768888

Learning Policy Institute (2018). Understanding teacher shortages: 2018 update. Available online at: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/understanding-teacher-shortages-interactive (accessed August 15, 2021).

McKay, L. (2019). Supporting intentional reflection through collage to explore self-care in identity work during initial teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 86, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102920

McKay, L. (2021). Using arts-based reflection to explore preservice teacher identity development and its reciprocity with resilience and well-being during the second year of university. Teach. Teach. Educ. 105, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103424

McKay, L., and Barton, G. (2018). Exploring how arts-based reflection can support teachers’ resilience and well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 75, 356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.012

McKay, L., and Sappa, V. (2020). Harnessing creativity through arts-based research to support teachers’ identity development. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 26, 25–42. doi: 10.1177/1477971419841068

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. New York, NY: Scholastic Incorporated.

Paris, D., and Alim, H. S. (eds.) (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Perrone, F., Player, D., and Youngs, P. (2019). Administrative climate, early career teacher burnout, and turnover. J. Sch. Leadersh. 29, 191–209. doi: 10.1177/1052684619836823

Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 50, 325–327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.802520

Ramakrishna, M., and Singh, P. (2022). The way we teach now: Exploring resilience and teacher identity in school teachers during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:882983. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.882983

Said, S. B. (2014). Teacher identity and narratives: An experiential perspective. Int. J. Innov. Engl. Lang. Teach. Res. Hauppauge 3, 37–50.

Shapiro, S. (2010). Revisiting the teachers’ lounge: Reflections on emotional experience and teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.009

Souto-Manning, M., Llerna, C. L., Martell, J., Maguire, A. S., and Arce-Boardman, A. (2018). No more culturally irrelevant teaching. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Uitto, M., Kaunisto, S. L., Syrjälä, L., and Estola, E. (2015). Silenced truths: Relational and emotional dimensions of a beginning teacher’s identity as part of the micropolitical context of school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 59, 162–176. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2014.904414

Keywords: teacher education, teacher candidates, teacher identity, arts-based research, emotions

Citation: Kennedy LM and Glause K (2022) “Will I be molded or crushed?” Artistic representations of student teachers’ identities and emotions. Front. Educ. 7:970406. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.970406

Received: 15 June 2022; Accepted: 28 July 2022;

Published: 22 August 2022.

Edited by:

Laura C. Haniford, University of New Mexico, United StatesReviewed by:

Julian Kitchen, Brock University, CanadaAlexis Leah Jones, Eastern Illinois University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Kennedy and Glause. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura M. Kennedy, bGtlbm5lZHlAbm11LmVkdQ==

Laura M. Kennedy

Laura M. Kennedy Kaitlin Glause

Kaitlin Glause