- 1ATHENA Research and Innovation Center, Athens, Greece

- 2Department of Informatics and Telecommunications, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Social interaction has been recognized as positively affecting learning, with dialogue–as a common form of social interaction–comprising an integral part of collaborative learning. Interactive storytelling is defined as a branching narrative in which users can experience different story lines with alternative endings, depending on the choices they make at various decision points of the story plot. In this research, we aim to harness the power of dialogic practices by incorporating dialogic activities in the decision points of interactive digital storytelling experiences set in a history education context. Our objective is to explore interactive storytelling as a collaborative learning experience for remote learners, as well as its effect on promoting historical empathy. As a preliminary validation of this concept, we recorded the perspective of 14 educators, who supported the value of the specific conceptual design. Then, we recruited 15 adolescents who participated in our main study in 6 groups. They were called to experience collaboratively an interactive storytelling experience set in the Athens Ancient Agora (Market) wherein we used the story decision/branching points as incentives for dialogue. Our results suggest that this experience design can indeed support small groups of remote users, in-line with special circumstances like those of the COVID-19 pandemic, and confirm the efficacy of the approach to establish engagement and promote affect and reflection on historical content. Our contribution thus lies in proposing and validating the application of interactive digital storytelling as a dialogue-based collaborative learning experience for the education of history.

1. Introduction

Social interaction and social processes have been recognized as an important factor affecting learning, in general, and collaborative learning in particular (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 1991; Webb and Palincsar, 1996; van der Linden et al., 2000). Cobb and Yackel (1996) adopt a sociocultural perspective on learning that emphasizes the importance of interactions among participants: “learning takes place in and through social interactions, as participants negotiate meanings and interpretations in search of consensual or compatible forms of understanding,” assigning a key role to social interaction for the learning process. Dialogue as a tool for sociality has also been established as an end in itself (Burbules, 1993), with dialogic practices becoming an integral part of collaborative learning.

Building upon the aforementioned principles, previous work using a digital conversational agent (Petousi et al., 2021) was designed with the objective to “engage the students in constructive dialogue with each other,” promoting perspective-taking and collective reflection about the past in a history education context. A rule-based bot acted as a dialogue facilitator guiding a small group of students through conversations about a variety of topics related to Ancient Athens. It followed the “bot of conviction” approach adopted by ChatÇat (Roussou et al., 2019), a “provocative” bot created for the UNESCO Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey, and, later, applied to a collaborative learning context in the facilitated dialogue bot experience “A Discussion with Bo the Chatbot (McKinney, 2018; McKinney et al., 2020).

The ultimate aim of these experiences was to employ a more empathic attitude to history by applying the historical empathy model (Endacott and Brooks, 2013) to their design. The model aims to facilitate critical reflection and affective engagement with the past, beyond basic memorization of facts. It foresees three aspects, starting from historical contextualization as the basic learning of historical facts, moving to perspective-taking, as the understanding of the views of past people, and culminating in affective connection, i.e., prompting users to understand past people as individuals with their own emotions, values and worldview (McKinney, 2018).

In this paper, we continue along the same line of digital products applying historical reasoning (van Drie and van Boxtel, 2008) and historical thinking (Seixas, 2017) frameworks in formal and informal education; only this time we design and evaluate a web-based interactive digital storytelling application as a collaborative learning activity. Interactive storytelling is a specialization of the wider concept of digital storytelling. It is defined as a branching narrative where the user can directly influence the story plot and the characters' decisions and, in this way, create different story lines and alternative endings. To our knowledge, the potential of interactive storytelling as an incentive for dialogue has not yet been thoroughly explored and there is a concrete need to assess its validity and to identify best practices. An additional challenge that we attempt to address is to design for remote users, as the still on-going restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the need for versatile approaches to experience design.

Specifically, the objective of this work is to examine how interactive storytelling could function as a collaborative learning experience for remote users. Focusing on the story plot decision points, we seek to evaluate their effectiveness as an incentive for conversation when students are asked to experience the story together. We assess this collaborative interactive storytelling experience as a tool for the education of history, focusing on different aspects, including historical empathy, engagement, and overall user experience and the function of decision points to promote meaningful conversation. We first validate the concept through a preliminary study with history educators and then focus on assessment with students. We use a mixed methods approach, which combines qualitative and quantitative feedback obtained through observation, interviews, and questionnaires administered to the students. The study results confirm the potential of collaborative interactive storytelling combined with decision-making, revealing useful insights on its function to promote historical empathy and engagement.

In Section 2, we frame our approach with relevant work that supports our motivation. In Section 3, we present the interactive storytelling experience used in the context of this study. The study is presented in Section 4, followed by the results in Section 5. The last sections discuss our findings and conclude the paper.

2. Background

Our research draws from the areas of digital storytelling and its combination with social interaction in cultural heritage, as well as collaborative learning for the education of history.

2.1. Digital storytelling and sociality for engagement with history

Digital storytelling has long been recognized as an effective method for the communication and interpretation of the past in a cultural heritage context (Bedford, 2001), supported by several studies (Lombardo and Damiano, 2012; Pau, 2017; Poole, 2018; Roussou and Katifori, 2018) and considered a high priority for cultural institutions (Birchall and Faherty, 2016; Coerver, 2016). Applications of digital storytelling as a single-user experience for cultural heritage confirm the “strength of this approach to promote engagement, learning and deeper reflection, even for visitors with no particular interest in the specific period and themes.” Narrative has shown to function as "an incentive to delve deeper into history” (Katifori et al., 2020b), while narrative elements such as “humor, links to everyday contemporary life, an informal tone, the perhaps surprising use of unconventional characters” have been deemed as important in supporting the learning objectives of informal education institutions (Roussou and Katifori, 2018). Approaches range from pre-defined narratives with varying degrees of interactivity, and balance between fiction and facts (Pau, 2017; Poole, 2018), to more dynamic and interactive experiences (Lombardo and Damiano, 2012; Katifori et al., 2019; Vrettakis et al., 2021). Coerver (2016) discuss the importance of shifting from facts to stories that cultural heritage consumers may relate with, promoting emotions and curiosity and claim that, “what most visitors really need is a story–a memorable, emotionally resonant way to connect with a fundamentally foreign object.”

Pujol et al. (2013) provide a thorough account of the importance of storytelling for cultural heritage and its effectiveness to provoke curiosity, foster engagement and promote learning. Storytelling “contributes to re-experiencing one's own heritage” (Abrahamson, 1998), while “transmitting cultural values and sanctioning what beliefs and behaviors are allowed or not” (Bruner, 1990). Bruner (1990) also describes storytelling as “the first, most essential form of human learning,” promoting meaning-making through the “imaginative state” it establishes. Following the constructivist theories of learning, “stories are more easily remembered than raw facts because they contain an underlying structure and can be linked with prior experiences” (Pujol et al., 2013).

Storytelling can be characterized as “interactive” when there is at least a basic amount of user agency in relation to how the narrative unfolds. The user can directly influence the story plot and the characters' decisions through choices and, in this way, create different story lines and alternative endings. The choices, or decision points, are placed in specific and meaningful moments of the narrative, based on the premise that “story richness depends on the functional significance of each choice and the perceived completeness of choices offered” (Crawford, 2013). The term “interactive storytelling” has been used to characterize a wide spectrum of narrative types (Chrysanthi et al., 2021). Koenitz (2015) provides a thorough presentation of this diverse field, including a wide spectrum of applications: from the first text-based Interactive Fiction to such forms as Hypertext Fiction, Interactive Cinema, Interactive Installations, Interactive Drama, and Video Game Narrative. However, due to the specific challenges of the genre, very few interactive storytelling experiences have been applied to the heritage domain (Katifori et al., 2018). This research in digital interactive storytelling as a narrative type in cultural heritage has motivated us to explore its application in an educational context.

Three main types of digital storytelling have been recognized in an educational context (Robin, 2008): personal narratives, stories that inform or instruct, and stories that examine historical events. Personal narratives are stories revolving around significant life events and are usually emotionally charged and personally meaningful. Stories that inform or instruct are specific types of stories used primarily to convey instructional material in many different content areas. Stories that examine historical events recount past events from history. The Center for Digital Storytelling (University of Houston, 2022) is known for developing and disseminating a guide that describes the seven main elements of digital storytelling. These include, among others, dramatic questions that provoke curiosity, emotional content, which connects the story to the audience, and the use of multimedia, sound and music to support the story line and convey emotion. Although ours is a fictional story, its setting is historical. One of its objectives is to convey historical events and provide information about the specific setting, thus combining fiction with facts, informed by the aforementioned guide.

Robin (2008) argues that educators should use digital storytelling to support each student's unique learning capabilities and needs by encouraging them to organize and express their individual ideas and knowledge in a meaningful way. He suggests that “teacher-created digital stories may be used to enhance current lessons within a larger unit, as a way to facilitate discussion about the topics presented in a story and as a way to make abstract or conceptual content more understandable.” Consequently, digital storytelling can help with the understanding of difficult or controversial historical events and topics, which is integral for reflection and understanding about human nature and society. Listening or watching a story can have a great impact as students make connections to their own lives as well as relate empathically with others after the storytelling experience. This indicates that just participating simply as a listener of stories is still an important act of negotiation and diplomacy (Mello, 2001). Gallagher (2011) justifies the use of storytelling and interpretation as critical practice for education by pointing out that during a storytelling experience we enter another's standpoint through the story, as well as the circumstances that give rise to it. Nonetheless, a theoretical model/framework for such approaches is yet to be established.

Visual Novels (VNs) are a sub-genre of interactive narratives, which offer interactive experiences where users can impact a storyline through certain actions. Cavallaro (2010), attributes the following elements in VNs. They are (1) narratively driven experiences consisting of mainly text, backgrounds, and dialogue boxes with character sprites; (2) illustrations/graphics presented to the player at central stages in the game narratives; and (3) a branching narrative with multiple endings, based on the player's choices. VNs have the potential to be used for educational purposes due to the accessibility this genre provides, with a low demand on player actions, focusing on storytelling, and role-playing / role-identification elements. According to Øygardslia et al. (2020), a key concept related to the educational properties of visual novel games is identity, as players may project their own ideas and values into the character. This means that players can identify with the character and learn from the outcomes of their choices, which are central to reflection and self-awareness. VNs can also be used to exemplify topics and promote reflection through ‘defamiliarizing' the familiar. Thus VNs drawing upon historical topics and those set in contemporary or fantasy settings can create narratives that illustrate specific subjects and make them come to life, or portray current topics promoting discussion and reflection (Øygardslia et al., 2020). There are five key dimensions for educational design and teaching strategies within Visual Novels: 1) Teaching Through Choice, 2) Teaching Through Scripted Sequences, 3) Teaching Through Mini-games, 4) Teaching Through Exploration, and 5) Non-interactive Teaching (Camingue et al., 2020). Although VNs have been used in education, so far there is no application in dialogue-based learning.

Social theories of learning (Vygotsky, 1987) emphasize the importance of social interaction, also in a storytelling context. Several projects have been developed combining sociality with digital storytelling and encouraging system-mediated conversation (Kuflik et al., 2007, 2011; Katifori et al., 2020a). The Sotto Voce project (Aoki et al., 2002), for example, as well as SFMOMA's mobile application (Pau, 2017), build upon the eavesdropping metaphor to implement sharing through a social listening experience. Other approaches combine in the same experience individual reflection parts with shared conversation or other types of social interaction (Callaway et al., 2014; Huws et al., 2018; Katifori et al., 2020a; Vayanou et al., 2021). In some cases, these approaches shift the focus from the museum expert's perspective to that of the visitors, creating a space for shared reflection and meaning-making where the expert assumes a facilitating role (Gargett, 2018; Vayanou et al., 2021). Building upon this line of research, we combine interactive storytelling with interaction points that encourage group dialogue and joint reflection. Such digital heritage experiences promoting informal learning are in line with the principles of collaborative learning, as they have been extensively discussed in literature from a more formal education perspective.

2.2. Collaborative learning and the history education

Collaborative learning is a general term, covering a range of techniques that shift the initiative and responsibility from the educator to the students. It involves students working together on activities or learning tasks in a group small enough to ensure that everyone participates. The activity can take different forms, including peer critiques, small writing groups, joint writing projects, peer tutoring, etc. Whatever the specific technique used, collaborative learning occurs when students assume more responsibility in the learning process and the material used, becoming active participants in their own education (EEF, 2021).

Scholarship differentiates between “collaborative” and “cooperative” learning. Both cooperative and collaborative learning have roots in social constructivism, and the cognitive developmental theories of Vygotsky and other scholars. Cooperative and collaborative learning are both active learning methods, in contrast to the more traditional models of education focusing on transmission of knowledge. While both approaches share a great deal in common, there are important and discernible differences (Sawyer and Obeid, 2017). Cooperative learning generally focuses on working in an interdependent fashion, where each member of the group is often responsible for a “piece” of the final product. In cooperative learning, instructors may also play a greater role in scaffolding activities by creating intentional groupings of students, or randomly assigning students to groups. Collaborative learning however, tends to feature more fluid, shifting roles, with group members crossing boundaries between different areas of work, or co-deciding the best ways to collaborate on their joint project. Goals and tasks may be more open-ended, and collaborative groups are generally more “self-managed” in terms of setting goals and establishing styles of interaction (Sawyer and Obeid, 2017). Our approach is a mixed method between cooperative and collaborative learning. We applied this mixed method approach as we considered it more suitable for following independent and interactive learning strategies based on the activity the storytelling experience provided and in this paper we use the term “collaborative” throughout.

Collaborative learning approaches have been widely used in various educational settings. Johnson and Johnson (2008) draw on their extensive experience in both the research and practical aspects of cooperative learning to draw out the factors that lead to success in academic tasks. In order for students to be involved in the learning process, five elements are necessary (Johnson and Johnson, 2008): Positive interdependence, individual and group accountability, interpersonal and small group skills, face-to-face promotive interaction, and group processing. King (2008) argues that a major challenge in implementing collaborative learning approaches is to stimulate higher thinking and learning, which requires students to go beyond mere retrieval and/or reviewing of information, to engage in analytical thinking of that information and relate it to what they already know.

Leinhardt et al. (1994) studying historical reasoning from the perspective of instructional explanations given to students, described it as “the process by which central facts (about events and structures) and concepts (themes) are arranged to build an interpretative historical case.” Historical reasoning is conceptualized as an integrative and socially situated activity. Reasoning about processes of change, causes, consequences, similarities, and differences in historical phenomena and periods helps students to give meaning to the past (van Drie and van Boxtel, 2008).

The Public History Initiative of the University of California (UCLA)1, has developed standards that include benchmarks for history and historical thinking skills, which define historical thinking in five parts: (1) Chronological Thinking, (2) Historical Comprehension. (3) Historical Analysis and Interpretation, (4) Historical Research Capabilities and (5) Historical Issues-Analysis and Decision-Making. By engaging in the analysis of historical issues and relevant decision-making, the students are able to identify the interests, values, perspectives, and points of view of those involved in past events. They are also able to evaluate alternative courses of action offered to those past people, keeping in mind the information available at the time, in terms of ethical considerations, the interests of those affected by the decision, and the long- and short-term consequences of each.

Collaborative learning has been implemented on a number of occasions in history education. Steffens (1989) has put collaborative learning into action in the form of cooperative research, writing and peer review in a history seminar. Steffens has noted that student involvement and learning has increased since incorporating collaborative learning techniques into the course format. van Drie et al. (2005) have focused on how a computer supported collaborative learning (CSCL) environment elicits and supports collaborative learning, in a historical inquiry task and an argumentative essay. Another study about two cases (“StoryBase” and “Parole in Jeans”) (Trentin, 2004) showed that a CSCL process can improve learning in many respects, even when collaboration takes place on-line.

The evaluation of the “Hermias, the Bot” collaborative learning experience (Petousi et al., 2021) that we developed prior to the work reported in this article confirmed that it was indeed successful in promoting a deeper, more affective, connection with history, and reflection on the past in relation to the present. The bot was designed to facilitate guided conversation between the participants on specific topics. It combined information offered by the bot with questions toward the student group interacting with it, and concluded with open, philosophical questions. Perspective-taking (PT) was by far the most prominent aspect of historical empathy evident in its evaluation sessions. The structure and content of the bot promoted open conversation on different aspects of life in ancient Athens, including social, political and religious institutions as well as everyday life practices and customs. The children exchanged opinions and ideas, taking into account the perspective of the ancient Athenians, and often compared life in the past with today.

The bot avoided offering strong personal opinions and comments, adopting a more neutral stance, to encourage students to voice their own thoughts and ideas. In this sense, the nature of the dialogue privileged perspective-taking, resulting from a more philosophical and conceptual dialogic process, rather than an affective connection that could result from a closer look at the life, emotions and thoughts of specific individuals of the past.

Inspired by collaborative learning approaches in general and dialogue-based bot experiences in particular, as well as their assessed effectiveness for promoting historical empathy for the education of history, we aim to explore alternative ways to engage students in dialogue. Our objective is to examine an approach where the participants experience and then reflect on the past through the eyes of the past people. We seek to complement the more detached and high level dialogue promoted by the bot with more affective conversation. To this end, we turn to an interactive digital storytelling design applied as a group experience and ultimately as an incentive for dialogue.

3. The interactive storytelling experience concept

For the purposes of this study we adapted an interactive storytelling experience created for an on-site visit to the archaeological site of the ancient Agora (market) of Athens (Katifori et al., 2019) using a mobile device as a guide. Additional content and instructions have been added to the story to make it suitable for off-site (online) viewing, and support its collaborative aspects.

The historical context in which this interactive storytelling experience is situated is that of Ancient Athens during the classical period (480–323 BC), a difficult period in the history of the city. Athens has been defeated in the recent Peloponnesian War and the life of many Athenians faces a deep crisis due to the aftermath of the war. Wealthy citizens of Athens have faced financial ruin. Thus, the story becomes an incentive for deeper reflection on issues very much relevant also to today: the financial crisis and its implications, ethical, political and social issues of distribution of wealth, and more personal issues of coping in times of crisis.

The main character of the story is Hermias, a slave. Slavery in ancient Athens is a controversial institution for a city known as the “cradle of Democracy.” The divide between free citizens and slaves seems to be a simplistic view of this society and there are gaps in our knowledge. Hence, this theme offers an opportunity for interesting historical fiction. Hermias experiences concerns and feelings that are valid and current also today, including financial insecurity, personal fear for the future of the individual and their family and loved ones, feelings of trust, or lack of, toward others, etc.

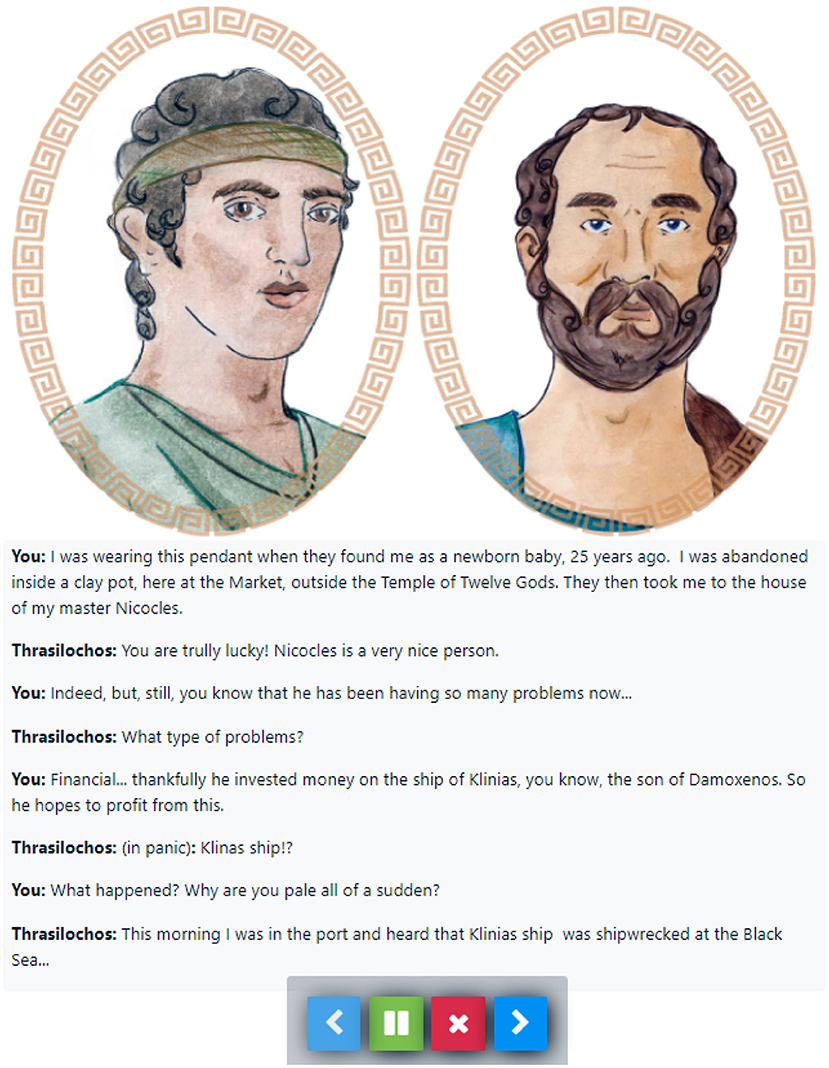

The story unfolds in a sequence of scenes with conversation between its characters, combined with brief narration segments situating the conversation in time and space. Decision points are available at the end of each scene, allowing the user to control how the story continues. The user experiences the story from the perspective of the main character, instructed to make choices in his stead (Figure 1).

The interactive storytelling experience features 7 decision points at each story path and 15 alternative endings defined by combinations of these decision points. To address the issue of “functional significance” (Crawford, 2013) of the choices, some of the decision points are decisive about how the story unfolds later on. For example, already at the start of the experience, the user is asked to decide whether the main character should wear or not his protective amulet, which has been with him since he was a child. Another example of a decision point is the following:

Soon a beautiful woman accompanied by her slave approaches. Her eyes meet yours. She stops and addresses you…

– You are distressed. You need to talk to someone. And this woman seems very nice…

– You don't want to speak with anybody. Even more with this stranger approaching with a smile...

Other decision points are of a more ethical or emotional nature and are designed to provoke reflection rather than having any functional significance (Figure 2).

At three points in the story, especially after segments where specific, possibly unknown, historical concepts and terms are used, there is informational content available in the form of questions and answers. Examples include: “What is Tholos? What is the Peloponnesian War? What is the exposure of infants?” In the end, there is the possibility to find out what happened to the main characters after the conclusion of the story.

The endings present different outcomes for the main character, some more favorable than others, depending on the users' choices. One of the endings leads to an “anticlimax” as, sometimes, that can also occur in real life.

The interactive experience has been implemented as a web-based multimedia application using the authoring tool for digital interactive storytelling presented in Vrettakis et al. (2019, 2020). The users follow the story as a series of simple web pages. Each dialogue scene is presented with an image and audio of the dialogue. The dialogue text is also available on screen. The choices available to the user are presented as list type menus. By clicking on an option, the corresponding page opens. The users have the possibility to go back and revisit already viewed scenes or change their choices. The web application is optimized for ease of use and simplicity, minimizing any cognitive load resulting from having to learn a more complex application. Being a branching narrative, with choices available at the plot level but also access to informational content, the experience does not have a fixed time duration. A minimum duration for a single user, where spending time with peers on conversation about choices is not required, is estimated at 17–18 min; a maximum duration, if all choices are viewed, can go up to about 21–22 min.

4. Study

In this section we present the study objectives and articulate our research questions. We attempt a first validation of these questions from the perspective of the educators by collecting feedback through an on-line questionnaire. This pre-study confirms the potential of this research direction, as perceived by the educators. We then present the details of a study design where teenagers are called to experience the interactive storytelling as a collaborative activity and provide their feedback. We report on the evaluation methods, participants, process, and data analysis.

4.1. Study objectives and research questions

The main objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of interactive storytelling, and its combination with dialogue between participants, as a collaborative learning tool to promote historical empathy. To this end, we focus on the following research questions:

• RQ1 - Does interactive storytelling as a collaborative dialogic activity provoke curiosity and engagement with the specific historical context?

• RQ2 - How is the joint decision-making process at the story plot decision points perceived by the students?

• RQ3 - Is the dialogue activity at the storytelling decision points effective in promoting historical empathy in general and affective connection in particular?

• RQ4 - Can the collaborative experience function effectively when the participants are not collocated?

In the next section, we briefly present the results of the preliminary validation of our concept with 14 educators. We then move on to the description of the main study design with 15 teenage participants.

4.2. Pre-study validation of the research objectives with educators

Before moving forward in organizing the main study to assess the efficacy of our approach with adolescents, we distributed a questionnaire addressed to educators, to record their insights and perspective. Through an open call that was distributed to adult researchers, faculty members, and personal acquaintances, we sought secondary education educators with experience in the teaching of history. The individuals who agreed to participate were sent the relevant consent form, the link to the interactive storytelling experience, and an online questionnaire to fill in anonymously after the experience.

Fourteen middle and high school educators participated in the preliminary study, 12 women and 2 men, 28–65 years old. They were all experienced in the teaching of history in different classes in secondary education. They were sent instructions on how to view the experience as well as a description on how the story's decision points could be used as an impetus for conversation and joint decision-making between the adolescents.

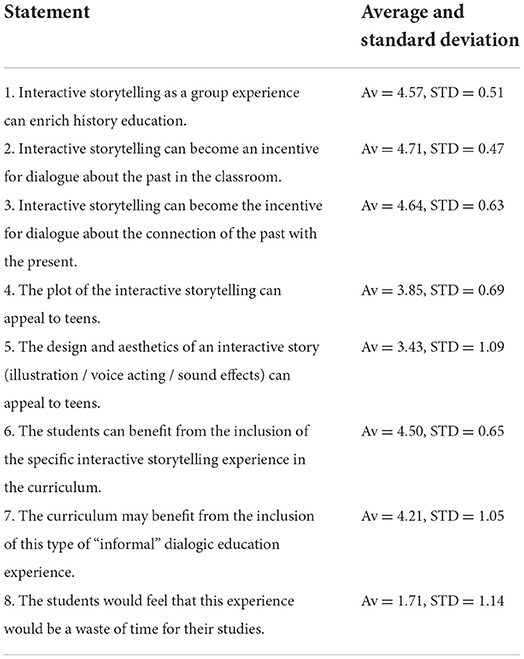

The questionnaire (see Supplementary material: Questionnaire for educators) includes 11 questions and an additional field for open comments. Questions 1–8 consists of statements that the participants score on a 1–5 Likert scale, from Completely disagree to Completely agree. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Pre-study with educators: questionnaire results for statements 1-8 (score in Completely disagree (1) to Completely agree (5) on the Likert scale).

As indicated by the results, the educators were very positive about the concept of interactive storytelling as a dialogic experience. In their comments some noted that the experience could be combined with a session of dialogue in class, engaging the whole class together and further elaborating on the topics relevant to the experience. When asked what in their opinion would be the most effective use of the experience, the majority (ten participants) responded “As a group activity of 2–3 students,” two selected “As an activity for the whole class together,” one “As an individual experience” and one “As a group experience with the group size defined by the available equipment, with two being the optimum number.” Four of the participants noted that this type of guided dialogic process may be particularly beneficial in helping participants to develop soft skills such as engaging in dialogue, exchanging opinions, and joint decision-making.

In relation to the topics that they would like an interactive story to highlight in this context, “Everyday life in antiquity” was the most prominent one, with 10 responses. As three of the participants noted in their comments, this aspect is “less pronounced and highlighted” in the textbooks and such an approach “would promote a closer perspective to the life of the people of the past”. Topics such as social inequality, slavery, and the position of women in the past and in comparison with today were also mentioned by several of the participants as important to include in the story concept.

Having confirmed that our concept for a collaborative interactive storytelling experience was meaningful to the participating history educators, we proceeded with our study design with students.

4.3. Study design and instruments

To explore the study research questions, we organized a user study with teenage participants. They were invited to experience in small groups, remotely, the interactive digital storytelling described in Section 3. We collected their feedback using a mixed methods approach, adapted from Petousi et al. (2021) to collect data. The data we collected combined:

(a) Observation of the participants during the experience. For each group we recorded the duration of the dialogue segments as well as the dialogue content itself, combined with possible non-verbal cues conveying emotions, such as laughter.

(b) A post-experience individual questionnaire (see Supplementary material: Questionnaire for students). This questionnaire has been adapted from studies attempting to record user engagement and historical empathy in digital storytelling experiences (Katifori et al., 2020a; Petousi et al., 2021). It is composed of two main parts, aimed to record (a) the participant profile (6 questions) and (b) the student's perspective for the experience (25 questions).

(c) A focus group discussion with each of the participant groups, guided by a list of 7 questions (see Supplementary material: Interview questions guide).

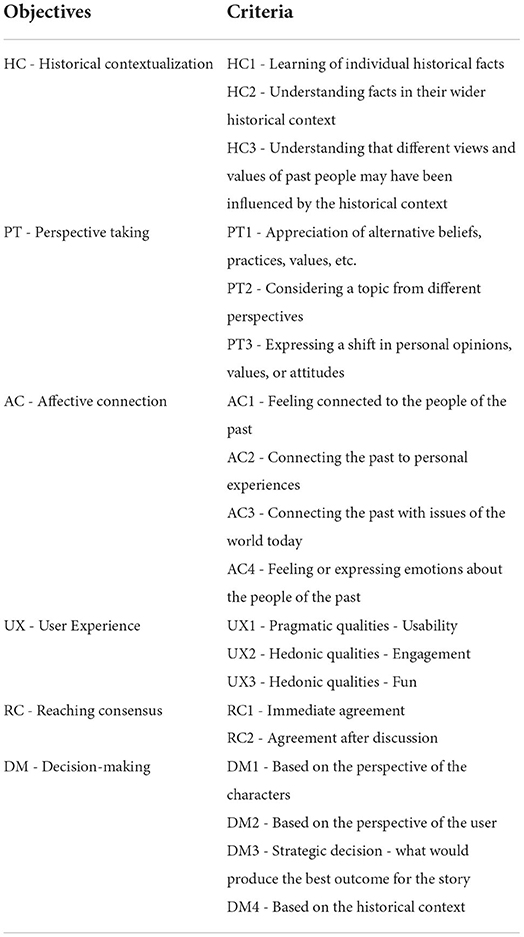

The aforementioned questionnaire, interview, and observation data were designed to support our research questions by recording three main categories of findings:

1. Those related to User Experience, denoted with the prefix UX in the results section. For general participant engagement with the digital storytelling application we took into account UX aspects, measuring its pragmatic qualities (“ease of use”) and hedonic qualities (“joy of use”) (Merčun and Žumer, 2017);

2. Those related to interactivity, denoted with IN. In this context "interactivity" refers to the function of the digital storytelling as an interactive, branching narrative, providing to the users the possibility to choose the direction the story unfolds at key decision points;

3. Those related to historical empathy, noted with the relevant prefix for each of its three aspects, namely historical contextualization (HC), perspective-taking (PT), and affective connection (AC); and

4. Those related to decision-making (DM) and consensus (RC). Specifically, which perspective is considered during decision-making (the character's, the user's, the historical context, etc.) and how easily the group reached consensus during decision-making.

These are presented in detail in Table 2.

As the specific historical period is included in the Greek education curriculum, we expected that the participants would have basic pre-existing knowledge. Before the start of the experience and to establish a baseline, the participants were asked a few questions in relation to the topics, including “What do you know about the status of slaves in ancient Athens?”. Also, indirect questions like “did you learn something new today?” were included in the post-experience interview. Although in this study we focus more on affective connection and perspective-taking, through these questions, we attempt to consolidate the participant's self-perceived learning outcomes to assess the effect of the experience on historical contextualization.

4.4. Participants and procedure

Originally this study had been designed for collocated users, i.e. a group of students positioned in front of the same screen. However, the on-going safety measures imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for effective educational activities to support remote teaching. So instead of having the teenagers co-located, we adapted the experience and process to conduct the evaluation sessions remotely, using a teleconference platform with screen sharing functionality. One of the group members was designated to use the storytelling application and would also screen share for others to watch the story as well.

Participants in this study included 15 junior high and high school students, 10 girls and 5 boys between the ages of 13 and 17. Members in each group knew each other, either as classmates or friends. The groups had the following composition (participant names have been substituted with pseudonyms):

• G1: Alan (boy aged 15), Nathan (boy aged 15)

• G2: Damien (boy aged 13), Gina (girl aged 13), Rebecca (girl aged 13)

• G3: Erica (girl aged 15), Marissa (girl aged 15), Naya (girl aged 16)

• G4: Michael (boy aged 14), Nigel (boy aged 14)

• G5: Anne (girl aged 16), Diana (girl aged 17), Mona (girl aged 17), Mayra (girl aged 16), Nellie (girl aged 17).

All participants in this study were volunteers and were recruited via an open call through email to participate in the study, disseminated by the authors to parents and educators. The purpose of the study was stated in the invitation. We invited volunteers to participate in small groups of 2–5 teenagers who were familiar with each other, so conversations could be more informal and rich since the children would feel more comfortable to talk. An information sheet and a consent form were given to the children's guardians containing information about procedures, voluntary participation and contact information of the researchers. The participants were not rewarded or incentivized in any way. The guardians were asked to sign the consent form a few days before each evaluation session. The evaluators then set up the evaluation session at an arranged date and time. Before the start of each session, the evaluators briefly introduced the process and then asked participants to assign the member of the group who would control the storytelling application. Then the evaluators retreated with their cameras in off mode and their microphones muted to observe discreetly and respond if any issue or query arose. The sessions were recorded, with the participants' and their guardians' permission, while the evaluators kept notes throughout each session. At the end of the session, participants were engaged together in a brief focus group discussion about the experience (see Supplementary material: Interview questions guide) and were asked to fill in the questionnaire individually (see Supplementary material: Questionnaire for students).

This study has been approved by the National Kapodistrian University of Athens' ethics committee.

4.5. Data analysis

The questionnaire results were collected and for each statement we calculated the average score and relevant standard deviation.

Two researchers segmented and analyzed independently the dialogue transcripts for each group. The analysis was based on the codes as defined in Table 2. After working separately for each transcript, reaching an 82% inter-reliability score, they met to identify the points where there were differences between their coding and jointly discussed those points to reach a common decision.

The duration of each dialogue segment for each group has also been calculated, including average duration and standard deviation per segment.

The interview responses were analyzed in conjunction with the questionnaire results in order to provide a deeper understanding of the participants' perspective.

5. Results

In this section we present the combined results of the analysis of the study questionnaire, interviews and participant observation, focusing on the four research questions, as presented in Section 4.

5.1. RQ1-Engagement

Our first research question explored the effect of social interactive storytelling on engagement: “RQ1 - Does interactive storytelling as a collaborative dialogic activity provoke curiosity and engagement with the specific historical context?”

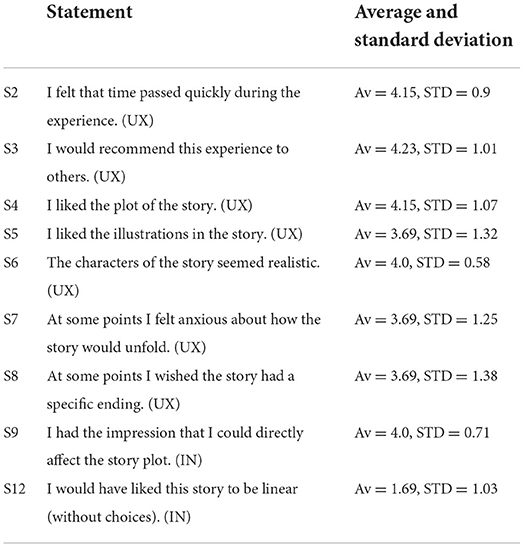

The study results reveal that the overall experience has indeed been engaging and effective in its UX hedonic aspects. The relevant questionnaire responses scored an average of close to or greater than 4, as shown in Table 3. The children consistently found the experience “interesting” (77%), “pleasant” (77%) and “original” (62%) and, in some cases, “realistic” (31%) and humorous (31%) (Statement 1–S1). They particularly liked the story plot and characters (S4 and S6) and their perceived sense that the story duration was short (S2) is indicative of general engagement and confirmed by the observed elements of fun, laughter, and captivation in all sessions.

Table 3. Questionnaire results for statements related to engagement (score in Completely disagree (1) to Completely agree (5) on the Likert scale).

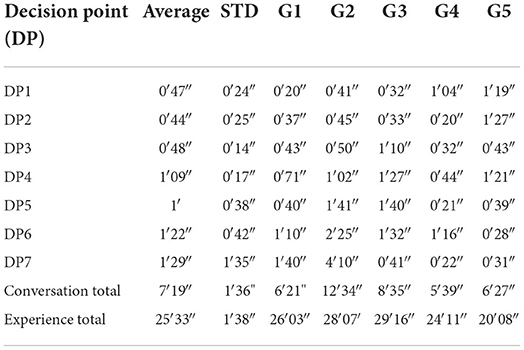

The actual average experience duration, as shown in Table 4, lasted more than 25 min, with the average conversation duration being approximately 7 min long. This indicates that the experience was successful in captivating the children's attention and promoting conversation.

When asked during the interview about what they generally liked or disliked, most teenagers commented that they “really liked” the experience and that “there was nothing bad or negative. Rebecca (G2) added: “I like everything about it, the whole combination of things.” and Nathan (G1) commented: “It is extremely innovative and can contribute to the entertainment of the user.” The fact that the story scenes were presented through dialogue seemed to be particularly appreciated. “I really liked the dialogue,” Michael (G4) commented, and Naya (G3) noted: “The dialogues added some kind of depth to the experience. I am not sure how to explain it. We heard the characters talking in a natural, everyday way. It was not like reading a textbook about the past.”

The fact that the experience was a branching narrative was discussed spontaneously by 3 out of 5 groups during the interview as one of its strongest points. Marissa (G3) mentioned “I liked that we were able to choose.” And, as Nathan (G1) commented, also confirming the need for functional significance of the choices: “I liked that our choices could lead to a different ending. They were valid ones, you knew your choice matters.” Some participants, like Alan (G1), even thought that it would be nice to be offered even more choices.

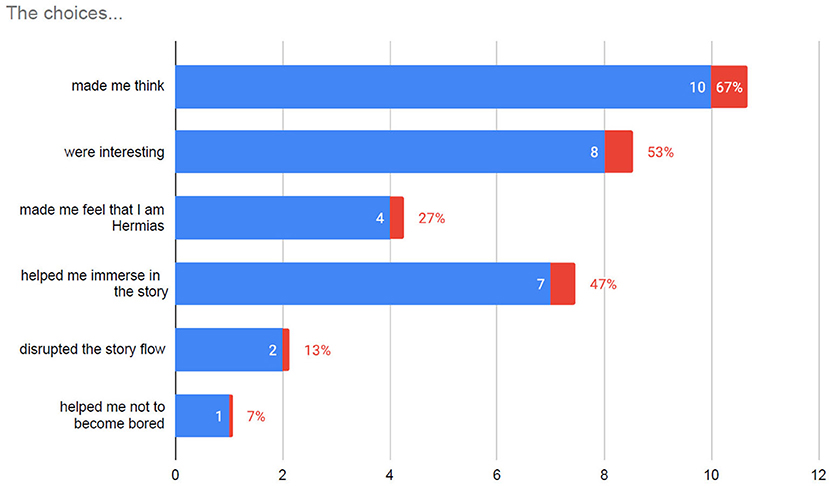

The interview results are confirmed by the relevant questionnaire statements (Table 3), showing that the participants felt that to a certain extent they could control the story plot and would not have liked the story to be linear. Figure 3 summarizes their responses as to how they would characterize the existence of choices in the narrative. “They made me think” was the most prominent choice, followed by “they helped immerse me in the story” and “they were interesting.”

Figure 3. Participants' perception of the effect of choices on the experience: The number and percentage of participants is indicated. Participants could select more than one option.

5.2. RQ2-Decision-making

In this section we present the results of our second research question: “RQ2 - How is the joint decision-making process at the story plot decision points perceived by the students?”

The collaborative nature of the experience was welcomed by the children, as the average score of questionnaire statement S21 “I would have liked to experience this story by myself” implies (Av = 2.08, STD = 1.26). Only one of the participants, Michael (G4), felt that he would prefer to view it alone. He was in G4 with only one other participant. Their interactions were brief, reaching consensus quickly. In the interview Michael clarified: “I would prefer to do it alone, or otherwise, with more people, 3 to 4, not just one. In this case it would be useful to be able to have some type of voting system when we need to choose.” Voting was also suggested by Anne (G5).

All participants felt that they did make joint decisions after discussing the available choices, based on the relevant questionnaire statements (100% “Yes” in S22 “We made joint decisions for the story within my group.” and 100% “Yes” in S23 “We discussed it within the group before making a choice.”) Table 4 confirms that at each decision point there was indeed a conversation between users, ranging from 20 s to more than 4 min.

The way decisions were made was characterized as “effective” (77%), “collaborative” (62%) and “pleasant” (46%) in the relevant questionnaire statement (S24). Similarly, their perceived sense of participation in the dialogue (S25 “I felt that I participated in the decision-making process.”) was particularly high (Av = 4.54, STD = 0.52).

The questionnaire results are supported by the relevant interview questions, with the participants providing more in-depth views about the dialogic process. Two were the main arguments in favor of collaborative decision making. Firstly, some participants felt that discussing and deciding together helped them to examine the choice from different perspectives, to consider all aspects, and to make an informed decision leading to the best outcome. Nathan (G1) commented: “Most probably, to our understanding, the ending was positive. Maybe if we had made different choices it would not be. And the group decision led to the best choices, exactly because you can listen to the opinions and views of different people, it leads to an objective choice. In the end you don't rely only on what you would do but on what would be the best choice at that moment.” Naya (G3) added a different perspective mentioning that “If I had been alone it would never end, I would not know what to decide. I think doing this together helped me organize my thoughts, focus on the story and somehow it did not break the story flow.” A similar thought was voiced by Nellie (G5).

Alan (G1) and Erica (G3) were also among those who explicitly classify the value of discussing the choices as “very positive” and as a “way to see different perspectives, ultimately leading to your own perspective possibly changing.” And, as Damien (G2) argued, “if we had been alone it would not have been as interactive and fun.”

All groups felt that they made the optimum decisions according to the circumstances. Some of them attempted to trace back on how the choices affected the positive outcome. Naya (G3) wondered: “I understood that our decision to wear the amulet in the beginning did play a significant role. I wonder what would happen if we had decided not to. The same with talking to Galatea. How would this have affected the ending? I am convinced we made the right choices but I would like to see what would be the alternative outcomes.”

Observed behavior within the groups revealed that indeed in the majority of the cases there was discussion between the participants before reaching consensus for the choice. An average of 4.4 incidents per group (STD = 1.14) reached consensus directly (RC1) vs. 2.6 (STD = 1.14) who reached consensus after discussion (RC2). Independently of agreeing or not, the teenagers still conversed and commented before making the choice (see selected transcripts in Supplementary material: Dialogue transcripts). Some decision points seemed to provoke conversation more than others, as shown in Table 4, and there were also differences noted between the groups. An example is the last decision point (DP7), ranging in conversation duration from 21 s to 4 min and 10 s. At DP1 all the groups chose to wear the amulet, although some considered reasons why not to. As a result, up to DP5, where the main character, Hermias, decides whether to talk to Galatea or not, the story plot is similar in all groups, except for G2 who decide not to talk to her. In all cases the group self-facilitated the dialogue, with the group member handling the application implicitly also assuming this role and making sure all members had expressed their opinion.

In terms of the decision-making perspective, the most prominent one was DM1 with an average of 4.4 per group (STD = 2.19). Although the participants attempted to make choices keeping the perspective of the main character in mind, it was inevitable that they were also influenced by their own perspective (DM2: Av = 2.4, STD = 3.05) and their understanding of the historical context (DM4: Av = 0.4 STD = 0.55), as well as the attempt to optimize the story outcome (DM3: Av = 1, STD = 1). As an example, in DP6 the students had to decide whether Hermias should react or not when being sold by his Master. In this case they felt that they should take into account who he is and his circumstances, and felt that it would not be realistic to react. As Naya (G3) discusses “We preferred realism when making decisions, trying to stay close to how things would happen at that period.” There were cases where these perspectives were mixed, switching for example from DM2 to DM1. As Damien (G2) mentioned while discussing whether to wear the pendant or not, “I would wear it. Since he believes it can protect him it might be helpful later on.”

5.3. RQ3-Historical empathy

The main objective of the collaborative storytelling experience was to give participants the necessary material and the appropriate motivation to develop historical empathy. Our third research question revolved around this concept: “RQ3 - Is the dialogue activity at the storytelling decision points effective in promoting historical empathy in general and affective connection in particular?” As the previous sections also reveal, the combination of storytelling with interactivity and dialogue seemed indeed to promote a more affective stance on the past. A closer examination of the combined results of the study provides insight as to how the experience has affected each of the different aspects of historical empathy, namely historical contextualization, perspective taking and affective connection.

Historical contextualization in our case refers to the degree of learning historical facts and understanding them in their wider context. Our focus in this study has been on the affective connection aspects of historical empathy; to this end we did not attempt to measure learning in a strictly quantitative way, by examining the participant's knowledge in depth before and after the experience.

An observed behavior at the three factual information branching points available, was that, although the users could choose to read more about specific topics, like the Peloponnesian War, they rarely chose more than one topic. They briefly scanned them and discussed what they already knew and what not, and selected one of the unknown ones to view, before moving on with the story. As some of the groups mentioned, and we also observed during the experience, there was a concern that focusing too much on the information would “break the story flow” (Rebecca - G2). In this sense, the children did not engage much with the offered factual information.

However, the participants' perceived sense of learning as indicated by the questionnaire results (Table 5) was high. The students felt that they learned something new (S13), their opinion about ancient Athens changed (S14), and they also felt inspired to learn more about it (S15). The interview analysis confirms that the students during the experience deepened their understanding of specific concepts and institutions that they already knew about, like the division of classes in ancient Athens, the institution of slavery, religion, etc. This was evident during the conversation between the children and also from their responses during the interview, especially on the question of “How would you describe the life of a slave in ancient Athens?” Most of the groups felt that the issue of slaves was more complex than they had expected. An interesting perspective was offered by G1. According to Nathan: “There are many factors to consider, but I believe now that the most important one is who your master is. If it is a person who means well, they will not treat you as a slave, an object, but as something more. We saw this contrast in the behavior of Nicocles and Eukrates. Eukrates saw Hermias as an object, not as a human being, he was cruel. Nicocles, on the other hand, had raised him as his own son.” And Alan adds: “Don't forget also the period and regime. At the golden age of Athens and the democracy, the life of slaves must have been better, not so hard. But at this period, after the big war and with the economic crisis… for sure their life must have been affected. Nicocles had to sell Hermias because he went bankrupt.”

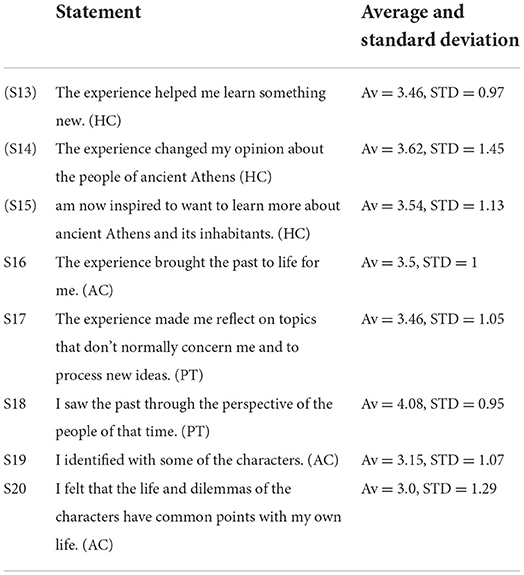

Table 5. Questionnaire results for statements related to historical empathy (score in Completely disagree (1) to Completely agree (5) on the Likert scale).

The ability of the experience to promote perspective-taking through dialogue has indeed been appreciated by the participants as a strong point. Evidence of examining a topic from different perspectives and considering new ideas is consistently observed in all groups (PT2: Av = 1.8, STD = 1.1) and confirmed by the questionnaire results (S17). Similarly, the students felt that they were able to see the past through the eyes of its people (S18).

The teenagers during the interview reported that they enjoyed watching the story unfold through a first person perspective, “through the eyes of a slave and not the master: we saw the past from the perspective of the lowest class” (Erica - G3). The sense of realism resulting from listening to everyday dialogues also seemed to support a more closer and personal perspective. This direct view through the eyes of the main characters, in combination with the conversation at the decision points, seemed to actually induce various degrees of affective connection in all groups. “Feeling or expressing emotions about the people of the past” (AC4), was consistently recorded in all groups (Av = 3.2, STD = 1.3), followed by “Connecting the past with issues of the world today” (AC3: Av = 1.8, STD = 1.8). As the dialogue analysis revealed, they seemed to understand that the past people's knowledge, beliefs and values may have differed from ours, and that people's intentions and goals may be personal or complex. They seemed to recognize that past actions can be perceived as actions that have hidden motives and relate to things not in an obvious and direct way.

As discussed in Section 5.2, during the decision-making process, the adolescents attempted to reconcile their own personal and emotional perspective on how they or the main character should react, with the historical context dictating what the most realistic reaction would be. As Naya (G3) explained, about the decision on how Hermias should react when his new master is verbally abusive: “From our perspective, if someone did this to us, we would certainly talk back to them. However, we needed to consider that in that period and for his social class, the consequences would be grave for him if he did so. The division of classes then was very different than today. We had to take this into account.”

The affective aspect of the experience is indicated also by the way the children describe Hermias and the other characters during the interview: “I liked Hermias. He was not a toxic and sarcastic person. He was nice, and you could see that immediately.” Gina (G2) comments. And Damien adds “Yes, and also communicative and social, he was not shy.”

To conclude, the collaborative decision-making task in the interactive storytelling context was indeed successful in promoting historical empathy with a strong affective element, with the first person perspective being particularly enjoyable. As Nathan (G1) comments, “I would like to see more stories with the perspective of different social classes: a common citizen, an aristocrat, a politician, or even a soldier. It would also be very interesting to see the life of younger people, children of different social classes, through mini-stories in different time periods and places.”

5.4. RQ4-Effectiveness as a remote teaching activity

In terms of our fourth research question, “RQ4 - Can the collaborative experience function effectively when the participants are not collocated?”, the outcomes of the study are positive. Section 5.1 discusses the overall student engagement, as it has been observed and also reported by the students. Taking into account that the children are already accustomed with teleconferencing platforms and remote teaching due to the pandemic, they were familiar with the medium and adapted quickly to the process. The experience flowed naturally between the narrative segments and the dialogue activities, and the children enjoyed their participation in the dialogue and the collaborative decision making, as discussed in Section 5.2.

An additional feature in favor of the remote setting in comparison to the collocated one is the possibility for the educator to have a more discreet supervising presence during the experience. In the teleconferencing system the educator may switch off the microphone and camera and remain “invisible,” allowing the students to feel more comfortable and engage in the conversation more freely. During the evaluation sessions, as the experience progressed and the teenagers became captivated by the story and dialogue, they seemed to quickly forget the presence of the evaluators. They seemed immersed in the group experience, relaxed and engaged often in humorous remarks. Although a targeted study is needed to examine the effect of the physical presence of the educator in a collocated study, the results are by themselves very positive for the remote setting.

On the whole, taking into account the positive outcomes of the study in response to our research questions, we can conclude that this experience design has great potential to be effective as a remote teaching tool.

6. Discussion and limitations

In this paper we focus on assessing the potential of interactive digital storytelling as a means for collaborative learning in history education. The story decision points become the incentive for reflection and dialogue between small groups of students, enhancing the engagement already established with the use of storytelling as a medium. We apply this approach in a remote teaching context, proposing, however, a design that could easily be adapted to a collocated one. This approach allows for flexibility that has been shown to be necessary during the trying times of the pandemic. Our study sample is not large, however the results already confirm that the collaborative experience can indeed engage the participants in meaningful dialogue. Even though it was their first encounter with such an activity, all groups were engaged in a dialogic process that was smooth and respectful.

This research falls within the theoretical approaches highlighting the notion of dialogue as an education practice. Dialogue takes place to support the collaborative decision-making process during the decision points in the interactive storytelling. We argue that this enactment of collaborative decision-making may be successfully operationalised through the connection between the interactive digital storytelling (motivating listening skills) and the implementation of dialogue (motivating social skills) and collaborative decision making (motivating cooperation skills) (Kirbaş, 2017). The experience employs dialogue, argumentation, and cooperation as means to achieve perspective-taking and historical empathy.

Fisher (2013) also developed practical ways to enhance the dialogic learning practice in the classroom. His approach revolves around six consecutive stages of dialogic assessment: listening, responding, engagement, participation, dialogic skills, and understanding, combined with a list of success criteria with a description of evidence of different levels of engagement (Fisher, 2013). Fisher's framework highlights the necessity of the aforementioned dialogic approach for advancing children's learning through discussion. It is an approach that explores strategies that can be used to help learners talk in pairs and groups, solve problems with others and talk together in practice. Fisher argues that by talking together in groups, children can learn how to think widely and deeply, learn collaboratively as part of a group, develop dialogic skills, and practice social and cooperative skills. This can increase learners' self-awareness and autonomy. Although we didn't apply Fisher's framework in our analysis, we observed that participants reached different stages, particularly the first 3 (listening, responding, and engagement) during the storytelling part, and the 4th stage (participation) during the decision points. In the future we plan to integrate Fisher's framework in our evaluation approach further to investigate the potential of collaborative decision-making through storytelling and the level of engagement in the dialogue it can trigger.

Since dialogue can function as a non-content-exclusive, non-context-specific versatile approach, it can be used across many subjects in a curriculum, i.e., dialogic approaches can be implemented in the learning of a second language. Long and Porter (1985) provide a psycholinguistic rationale for group work and dialogue that supports second language acquisition. They have identified the following aspects in group-work interlanguage talk that increases second language acquisition: quantity and variety of practice, correction, negotiation and clear two-way tasks. The research findings on interlanguage talk and group work support the claims for increases in the variety of language practice. Provided careful attention is paid to the structure of tasks students work on together, the negotiation work possible in group activity makes it an attractive alternative to the teacher-led, “lockstep” mode and a viable classroom substitute for individual conversations with native speakers. However, an important factor is the recipient, since Long and Porter (1985) highlight the importance of recognizing the difference in processes around acquisition for children and adults.

The effectiveness of the use of interactive storytelling as an incentive for decision-making dialogue hints at its potential beyond the development of historical empathy and reasoning. The participants engaged in a positive dialogic experience and had the chance to exercise their argumentation skills in a controlled and safe setting. This activity of exchanging opinions and reaching the best possible outcome created a positive sense of accomplishment. The potential of assuming another's perspective has already been widely discussed in the context of educational role playing games (Petousi et al., 2022). According to Daniau (2016), assuming the perspective of another gives the participants the chance to remember this character's experiences more vividly, as if they have happened to them, in a form of personal storytelling (Bowman, 2017). This activity promotes understanding of others' unique points of view, and allows users to practice social-emotional learning (SEL) (Hammer et al., 2018), including creativity, collaboration, and team building (Daniau, 2016) and better understand their reality (Bowman, 2010; Zalka, 2012).

Taking into account the study results and the insight of the educators participating in the preliminary study, we believe that collaborative interactive storytelling can similarly be employed for the development of soft skills, including engagement in dialogue, reasoning, perspective-taking and decision-making. Further studies, targeted to this specific objective, are needed.

An important aspect to be considered when organizing such activities is that discreet supervision of the children is necessary at all times, even though it may affect engagement with the experience and the ease that the students feel while conversing. The supervisor should ensure that the dialogue remains respectful and that no biases or false assumptions are introduced. Even though the educators may not intervene directly at that time, they need to be able to detect any misconception or bias so as to plan afterwards to address it with an additional activity in class. The proposed design, having the students and educators participating remotely, supports this discreet supervision, as the educators have the possibility to observe almost unseen in the teleconferencing system, if they keep their camera and microphone off.

When designing such a collaborative learning activity, balancing the narrative with the appropriate amount of decision points is key for a cohesive and engaging storytelling. Narration and giving historical information can help students understand the context of the historical event; however, without decision points that help shape the narrative, the story won't be very engaging or immersive. Striking the right balance between following a narration and the decision points which can be used as a motivation for discussion and perspective taking, is what makes for an impactful story. However, it is hard to define this balance of how many decision points are too many or too little. The ratio between narration and decision points can be solely defined by a combination of different factors, such as the type of the story, the length, its setting, its message, its educational aim, the number of participants etc. These interaction points should definitely serve concrete educational objectives.

Furthermore, the right balance between storytelling and historical information can make the story both credible and compelling. In our case extra historical information was provided in between the major plot points of the story, in the forms of questions. Although we noticed participants did not choose any questions about historical facts, they seemed to be eager to learn at a later time. Their main reason was not to break the immersion on the plot of the story. However, it could be interesting to investigate their behavior regarding this part, if the information was presented to them as helpful in order to advance the plot.

Group size is a factor that has not been thoroughly explored in this study. Our groups ranged from two to five participants, and conversation ensued in all cases. However, our insight from this small sample is that a group size of 3–4 people is optimum for this type of activity: with two participants sometimes there is no disagreement to push forward the conversation and with more than four, some participants may not get the chance to express their opinion fully. As future work, it would be interesting to repeat the study in a wider sample, adequately comparing between different group sizes.

This further research, along with exploring the effect of group dynamics, is needed to produce relevant guidelines. As an example, a relevant research question is whether this experience would be as effective for groups of children who are not already familiar with each other, to support informal education contexts such as the design of museum activities, where different families wish to enroll their children during the visit.

As the study results reveal, the children were able to empathize with the characters and reason about choices and opportunities of the hero from the past. In this sense, the experience has indeed been successful to a degree, in promoting emotional and cognitive empathy and helping the children reflect on the conditions of others and people of the past. All participants seemed to have fun with the whole process, learning through the perspective of people of the past. The majority of the students who participated gave reasonable and valid arguments for their preferred choices and, in addition to opinions, also expressed emotions about the characters. However, an important aspect that requires further research, not included in this work, are the long term effects of the experience. A more longitudinal approach would be interesting to reveal these aspects: the long-term gain of soft skills, effects of memory, satisfaction, and enjoyment. Some longitudinal studies of the long-term impact of museum exhibits have been conducted by Falk (2006), who sent a questionnaire to visitors a few weeks after their visit in a science center. Falk (2006) have found that cognitive and affective changes can be sustained after a period of the visit, if the museum experience is reinforcing personal relevance to the visitor. The understanding of the long-term impact of storytelling and collaborative experiences enables a better understanding of how to design and enrich the content of such applications. Although we did not specifically record the participants prior experience with similar types of interactive storytelling, from the general commentary of the participants during the interview it becomes evident that they are not familiar with the use of such an approach to promote dialogue. To this end, it would be important to examine the same research questions once the novelty factor is no longer in effect, after the adolescents become more accustomed to this type of educational activity. It would be interesting to investigate the various aspects (narrative, collaboration, content or media such as images, sound effects, etc.) that play a strong role in attracting and engaging users and making the experience more meaningful, memorable, inspiring, and personally satisfying for them.

7. Conclusion

In this work we present the findings of a user study on the effectiveness of a collaborative interactive digital storytelling experience as an activity for the remote teaching of history. Prompted by the need to provide alternatives to collocated activities during the difficult and on-going period of the COVID-19 pandemic, we decided to experiment with an approach that fosters social interaction and meaningful communication through dialogue, both significantly impeded due to the need for social distancing. The design is meant to be versatile, and can applied as needed in both contexts, collocated and remote.

In a nutshell, our findings suggest that:

• The overall experience has indeed been engaging, with the branching narrative and dialogue points commented positively by the adolescents as important contributing features.

• The collaborative nature of the experience was welcomed by the children, focusing on the effectiveness of joint decision making to reach the optimum outcome. The children combined different perspectives to reach consensus during the decision-making process.

• The combination of storytelling with interactivity and dialogue seemed indeed to promote a more affective stance toward the past, with its various features supporting all three aspects of historical empathy—historical contextualization, perspective taking and affective connection.

• The experience ran smoothly as a remote experience, with the added bonus that the educator's supervision is less conspicuous in this setting, possibly contributing to the children feeling more at ease to express their opinions in the dialogue.

Our concept of using interactive storytelling with meaningful decision points as an incentive for conversation was welcomed by educators as an in-class activity, either for collocated or for remote teaching. The students participating in the study also confirmed the potential of the approach, as our results reveal. We thus conclude that the combination of interactive storytelling and collaborative decision-making merits further research to understand its full potential and function for historical empathy and beyond. We aim to continue our research in this domain with more targeted studies, exploring how factors such as group size and group dynamics may affect the overall experience. Our aim is to compile useful guidelines for the design of storytelling-based collaborative learning experiences that can be effective in both collocated and remote contexts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the Department of Informatics and Telecommunications and the Research Ethics Committee (E.H.D.E.) of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

DP in collaboration with AK focused on the conceptual and experimental design for this research, and conducted the studies with educators and students. DP conducted the bibliographical study and AK performed the statistical analysis. KS authored the branching narrative and contributed to the questionnaire and study design in general. MR supervised the experimental process and materials, contributed to the narrative production, and to the recruitment of participants. YI supervised the overall research. DP, AK, and MR paper authoring was divided amongst. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the studies for their time.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.942834/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^National Center for History in the Schools-UCLA, https://phi.history.ucla.edu/nchs/history-standards/ (accessed May 9, 2022).

References

Abrahamson, C. E. (1998). Storytelling as a pedagogical tool in higher education. Education 118, 440–451.

Aoki, P. M., Grinter, R. E., Hurst, A., Szymanski, M. H., Thornton, J. D., and Woodruff, A. (2002). “Sotto voce: exploring the interplay of conversation and mobile audio spaces,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Changing our World, Changing Ourselves-CHI '02 (New York, NY: ACM Press), 431–438.

Bedford, L. (2001). Storytelling: the real work of museums. Curator 44, 27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2151-6952.2001.tb00027.x

Birchall, D., and Faherty, A. (2016). “Big and slow: adventures in digital storytelling,” in MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016 (Los Angeles, CA).

Bowman, S. L. (2010). The Functions of Role-Playing Games: How Participants Create Community, Solve Problems and Explore Identity, 1st Edn. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Bowman, S. L. (2017). Active Imagination, Individuation, and Roleplaying Narratives. Tríade: Revista de Comunicação, Cultura E Midia 5, 158–173. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/39536022/Active_Imagination_Individuation_and_Role_playing_Narratives

Burbules, N. C. (1993). Dialogue in Teaching: Theory and Practice (Advances in Contemporary Educational Thought Series). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Callaway, C., Stock, O., and Dekoven, E. (2014). Experiments with mobile drama in an instrumented museum for inducing conversation in small groups. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. 4, 1–39. doi: 10.1145/2584250

Camingue, J., Melcer, E. F., and Carstensdottir, E. (2020). “A (visual) novel route to learning: A taxonomy of teaching strategies in visual novels,” in International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (Bugibba: FDG '20), 1–13. doi: 10.1145/3402942.3403004

Cavallaro, D. (2010). Anime and the Visual Novel: Narrative Structure, Design and Play at the Crossroads of Animation and Computer Games. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company.

Chrysanthi, A., Katifori, A., Vayanou, M., and Antoniou, A. (2021). “Place-based digital storytelling. the interplay between narrative forms and the cultural heritage space,” in Emerging Technologies and the Digital Transformation of Museums and Heritage Sites, First International Conference, RISE IMET 2021 (Nicosia: Springer), 127–138.

Cobb, P., and Yackel, E. (1996). Constructivist, emergent, and sociocultural perspectives in the context of developmental research. Educ. Psychol. 31, 175–190. doi: 10.1080/00461520.1996.9653265

Coerver, C. (2016). On (Digital) Content Strategy. Available online at: https://www.sfmoma.org/read/on-digital-content-strategy/ (accessed July 19, 2022).

Crawford, C. (2013). “Interactive storytelling,” in The Video Game Theory Reader, 2nd Edn, eds M. J. Wolf and B. Perron (Milton Park: Routledge), 259–273.

Daniau, S. (2016). The transformative potential of role-playing games–: from play skills to human skills. Simulat. Gaming 47, 423–444. doi: 10.1177/1046878116650765

EEF (2021). Collaborative learning approaches: High impact for very low cost based on limited evidence. Technical report, The Education Endowment Foundation.