95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 19 July 2022

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.938224

This article is part of the Research Topic Pedagogic Innovation and Student Learning in Higher Education: Perceptions, Practices and Challenges View all 23 articles

Based on 34 studies and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review consisting of a meta-analysis and a meta-synthesis to illustrate the various self-reflection formats used in public health higher education. Through this review, we aimed to (1) describe the range of self-reflection formats used in public health undergraduate education, (2) compare the level of reflectivity and outcomes of self-reflection according to the common formats of self-reflection used, and (3) compare the facilitators and barriers to deep self-reflection based on the common formats of self-reflection used. Most students were not engaging in reflection at a deep level according to the Mezirow's model of reflexivity. Both meta-analysis and meta-synthesis results revealed self-reflection enhanced self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development as well as improved understanding of public health related topics in these students. Future educational programmes should consider the common facilitators to deep self-reflection, i.e., advocacy on the importance of reflection by instructors and provision of guidance to students and the common barriers, i.e., perception by instructors/students to be time consuming and the imbalance in power relationship between instructors and students. Because perceptions of learning environments varied between institutions, programs, teachers and students, efforts to evaluate the implementation feasibility of these facilitators and barriers need to take place across the different levels. As a start, peer ambassadors or champions could be appointed at the student level to change the common perception that performing deep self-reflection was time consuming. Similarly, at the teacher level, faculty learning communities could be set up for like-minded educators to advocate on the importance of reflection and to share their experience on balancing the power relationship between instructors and students.

Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO, identifier: CRD42021255714.

Higher education allows an individual to acquire knowledge and skills in a chosen field. It offers an opportunity for prospective graduates to gain insights into the potential challenges and problems they may face in their future careers. However, one concern of higher education is whether students are adequately being prepared for the workforce (Jackson et al., 2016). This arises because graduates may face intricate situations during their career which require critical thinking. The academic knowledge gained from higher education may not always be readily transferable to the workforce. To bridge this gap, higher education institutions have a crucial role to play by better preparing students for the workforce. One pedagogical approach to achieve this is self-reflection, of which one definition is “A conscious mental process relying on thinking, reasoning, and examining one's own thoughts, feelings, and ideas.” (Gläser-Zikuda, 2012). There are several definitions of self-reflection in higher education literature. These definitions vary depending on whether the focus is on practice or theory; these include philosophical articulations as in Dewey, formulations in theoretical frameworks according to the constructs developed by Schön, to the use of reflection in the experiential learning cycle by Kolb (Brownhill, 2021). Despite this, the value of self-reflection is well recognized across a wide range of contexts and countries (Brownhill, 2021). For example, reflection is generally regarded as being valuable for professional practice and lifelong learning. Moreover, it has been adopted in higher education training and accreditation standards in several countries in Europe and the United States of America, USA (Van Beveren et al., 2018). Reflection and learning are deeply intertwined with each other. Building upon a constructivist perspective on learning, engaging in self-reflection allows students to construct knowledge (Christie and de Graaff, 2017). It is during the actual process of relating specific situations and evaluations from different perspectives to more abstract conceptualizations that meaning is constructed and learning takes place (Biggs, 2012). When students reflect on experiences by analyzing their attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and emotions, it may lead to new understandings and meanings (Bubnys and Zydziunaite, 2010), which could enhance their motivation to take responsibility for their actions and decisions. In this way, reflection helps in making learning a process. Other reported benefits of self-reflection include increasing the self-efficacy of students toward deep learning leading to greater satisfaction in learning, improved life-long learning attitude, and increased employability (Young, 2018).

Like other disciplines, self-reflection is increasingly considered a crucial element in public health education (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013). Public health has seen a shift from postgraduate to undergraduate education in the early 2000 (Riegelman et al., 2015). This global interest probably first began in the USA (Kiviniemi and Mackenzie, 2017; Luu et al., 2019) due to efforts of the Institute of Medicine and the Association of School and Programs of Public Health recommending all undergraduate students to have access to public health education (Petersen and Weist, 2014). This move has since led to the refining of public health undergraduate curricula to ensure that graduates are well equipped to enter the workforce. Educators need to cultivate students into future public health practitioners and self-reflection is thus recommended as a useful pedagogical tool for undergraduate public health programs (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013). This is particularly crucial for this discipline because public health issues are becoming more complex and hence graduates need to be equipped with this competency to better handle them (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013). In addition, reflection in public health has been recommended so that practitioners could audit their own practice thereby promoting effectiveness and efficiency in the health-care system which they are serving (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013). Beginning the journey of reflection since undergraduate years would serve to remind practitioners that there is no end point to learning about their everyday practice. Unlike other disciplines, reflection in public health needs to go beyond focusing on themselves alone. This is because public health actions often take place across multi-sectoral teams, involve multi-phased interventions and are driven by policy changes (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013). This means that in public health, students and practitioners need to be familiar with reflecting not only as an individual entity, but as part of an interprofessional team and the society too. As public health students in higher education, it is thus important to reflect on both internal (e.g., attitudes, skills, experiences, and team dynamics) and external (e.g., policy, professional, and societal influences) factors beyond their own selves (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013).

Research on self-reflection has more than quadrupled as it gained traction in the past 20 years (Chan and Lee, 2021). Despite its wide implementation in higher education as well as the sizeable pool of empirical studies, there are a few gaps in literature. First, to the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic review pertaining to self-reflection in public health undergraduate education, despite it being one of the significant changes in higher education in the recent years as highlighted earlier. There is a need to review the use of self-reflection in public health undergraduate curricula which contributes increasingly to the global public health workforce (Kanchanachitra et al., 2011). Public health undergraduate education is typically offered as a minor, a major or even a degree globally, therefore students come from various disciplines (Resnick et al., 2018). These students thus have varying prior exposure to self-reflection. Moreover, most reviews on self-reflection target health professional disciplines (i.e., medical, nursing, and allied health) where students come from relatively homogenous background and receive education on direct patient care (Mann et al., 2009; Fragkos, 2016). These reviews do not relate to public health (Mann et al., 2009; Fragkos, 2016). The use of self-reflection differs between these two disciplines due to varying contexts and focuses. Reflective practice is highly context specific. For example, nursing students might be asked to “reflect” on a clinical experience involving administering intravenous antibiotics to a patient according to a predetermined set of hospital protocol of which they are expected to follow. This would contrast with public health students who might be requested to “reflect” on a community project experience involving delivering maternal and child health services to a subpopulation in a rural town where there is a range of aspects to be considered, for example, healthcare team dynamics, family dynamics, cultural norms, and societal impacts. With public health increasingly being incorporated into the curriculum of health professional disciplines (Jayatilleke and Mackie, 2013), there is a need to examine the use of self-reflection and its effectiveness in public health education.

Second, most reviews on this topic focused on the definitions and application of the models of self-reflection (Fragkos, 2016; Marshall, 2019) rather than the level of self-reflection which students engage in. There are various models and frameworks related to self-reflection. For example, Gibb's reflective cycle covers six stages of reflection where an individual initiate self-reflection by describing what happened, how they feel, assessing whether the experience was positive or negative, analyzing and making sense of the experience, drawing up a conclusion from the experience, and formulating a future action plan (Miller et al., 2020). While various models of reflection might be used, these are often based on a distinction between several levels or types of reflection, ranging from technical and practical to more critical forms of reflection (Van Beveren et al., 2018). Although there is no single “right way” to reflect, and that the value of reflection can be relative to the context in which it is taught, each of these models characterize critical reflection as an important and even necessary form of reflection (Van Beveren et al., 2018). In view of this, it is probably more important to evaluate the levels and dimensions of reflection that students could attain instead of the type of self-reflection model used. For example, Mezirow suggested that reflectivity could be categorized into seven levels and dimensions where the first four stages (reflectivity, affective reflectivity, discriminant reflectivity, and judgmental reflectivity) belonged to the consciousness level while the final three stages (conceptual reflectivity, psychic reflectivity, and theoretical reflectivity) belonged to the critical consciousness level (Mezirow et al., 2012). According to Mezirow, reflectivity (lowest level) involved a basic recollection or the start of being aware of a situation that had transpired without any further follow up. Affective reflectivity referred to reflection stopping at the emotion level, like how an individual was feeling toward a particular experience. Discriminant reflectivity involved an individual reflecting on his or her perceptions, actions, thoughts, and habits of carrying out things in a given situation. Judgmental reflectivity involved being aware of one's value judgment on one's experience. For the critical consciousness level, conceptual reflectivity involved questioning oneself if the current information provided was adequate to make a sound judgment. Psychic reflectivity level on the other hand referred to an individual being aware of his or her preconceived judgment on an experience based on given information. Lastly for theoretical reflectivity, this referred to an individual being aware that his or her preconceived judgment was based on various inadequacies following a perspective transformation (Mezirow et al., 2012). Higher levels of self-reflection foster deep learning (Young, 2018). Low reflection level implies superficial learning, presumably because learners with a limited ability to reflect let “tunnel vision” stop them from questioning their behavior in response to significant positive and negative experiences (Koole et al., 2011). There is thus a need to review the levels and dimensions of reflection students engage in public health curricula to better determine its effectiveness in achieving deep learning.

Third, there has been a recent increase in the incorporation of self-reflection into public health curriculum and programs through various reflective formats like journal, focus group discussion, photovoice, and narrative reflective practice (Sendall and Domocol, 2013; Hoffman and Silverberg, 2015; Babenko-Mould et al., 2016; Adams, 2019; Janssen Breen et al., 2019; Andina-Díaz, 2020; Haffejee, 2021). While Artioli et al. (2021) conducted qualitative meta-synthesis on the use of reflective writing on health professionals, focusing on one type of reflection format is insufficient to determine the impacts of self-reflection in public health higher education. There is a need for a review to identify the broad range of self-reflection formats available in public health education, and not to limit to only one format. Moreover, it is important to elicit the facilitators and barriers to promote deep reflection in higher education. While, Chan and Lee (2021) provided an overview of the challenges of encouraging reflection in higher education, these are not specific to deep reflection which is the desired level students should aspire to attain as highlighted earlier. In addition, facilitators are not reported in the review which could offer valuable insights for future curriculum and program improvement. Facilitators and barriers might also not be similar across the board range of reflective formats. Therefore, there is a need to examine the outcomes, facilitators, and barriers according to the broad range of self-reflection formats available in public health education. The three aims of the current systematic review are to (1) describe the range of self-reflection formats used in public health undergraduate education, (2) compare the level of reflectivity and outcomes of self-reflection according to the common formats of self-reflection used, and (3) compare the facilitators and barriers to deep self-reflection based on the common formats of self-reflection used.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (Page et al., 2021). The review protocol was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (Registration ID CRD42021255714).

A combination of computerized and manual searches was performed to identify all relevant data for the systematic review. We searched the following six electronic databases using the date ranges January 1, 2000, to April 30, 2021: Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), ProQuest Central, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and STM Source. In addition, we also manually searched the reference lists of all studies included in this review to identify additional relevant studies.

The electronic database searches were conducted using abstract and title terms. The following were entered for searches in the six electronic databases: (“self-reflection techniques” OR “reflective study” OR “reflective teaching” OR “reflexivity” OR “reflective learning” OR “introspection” OR “reflections” OR “reflective practice”) AND (“public health undergraduates” OR “public health education” OR “public health students” OR “public health pedagogy” OR “public health curriculum” OR “public health training”). No language or publication status restrictions were specified.

To be included in the review, a study had to meet the following criteria: (1) the students receiving public health education had to be undergraduates. There was no restriction on the major of these students hence students could come from any discipline. However, as a minimum, these students had to be taking a module or curriculum unit on public health; (2) used self-reflection as a pedagogical tool in public health undergraduate education. There was no restriction on the format of self-reflection used; and (3) evaluated the impact of self-reflection on students. The evaluation could be conducted using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. Studies were excluded if: (1) it was not possible to isolate the evaluation results to undergraduates alone in the event where the same type of self-learning was delivered to both undergraduates and postgraduates; and (2) there was only description of self-reflection without any evaluation results.

The first two authors screened the databases and reference lists independently. Citations were merged and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened using the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. If at least one of the authors evaluated the title or abstract to be relevant, the full text would be screened. There was a good interrater reliability of Cohen's kappa coefficient of 0.86. Data extraction focused on study design, setting, type of student, sampling/assignment technique and sample size, format of self-reflection used, outcome measurements, and evaluation results. Any discrepancies in eligibility assessment or data extraction were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus between both authors.

Methodological quality of the included studies was independently evaluated by the first two authors using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, MMAT (Hong et al., 2018). This was because the review contained qualitative and mixed methods studies. After responding to two screening questions, each included study was rated in the appropriate category of criteria as either “yes,” “no” or “can't tell”. There was a good interrater reliability of Cohen's kappa coefficient of 0.88. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach a consensus between both authors. We did not obtain an overall score for each study since this was discouraged in the latest version of the MMAT.

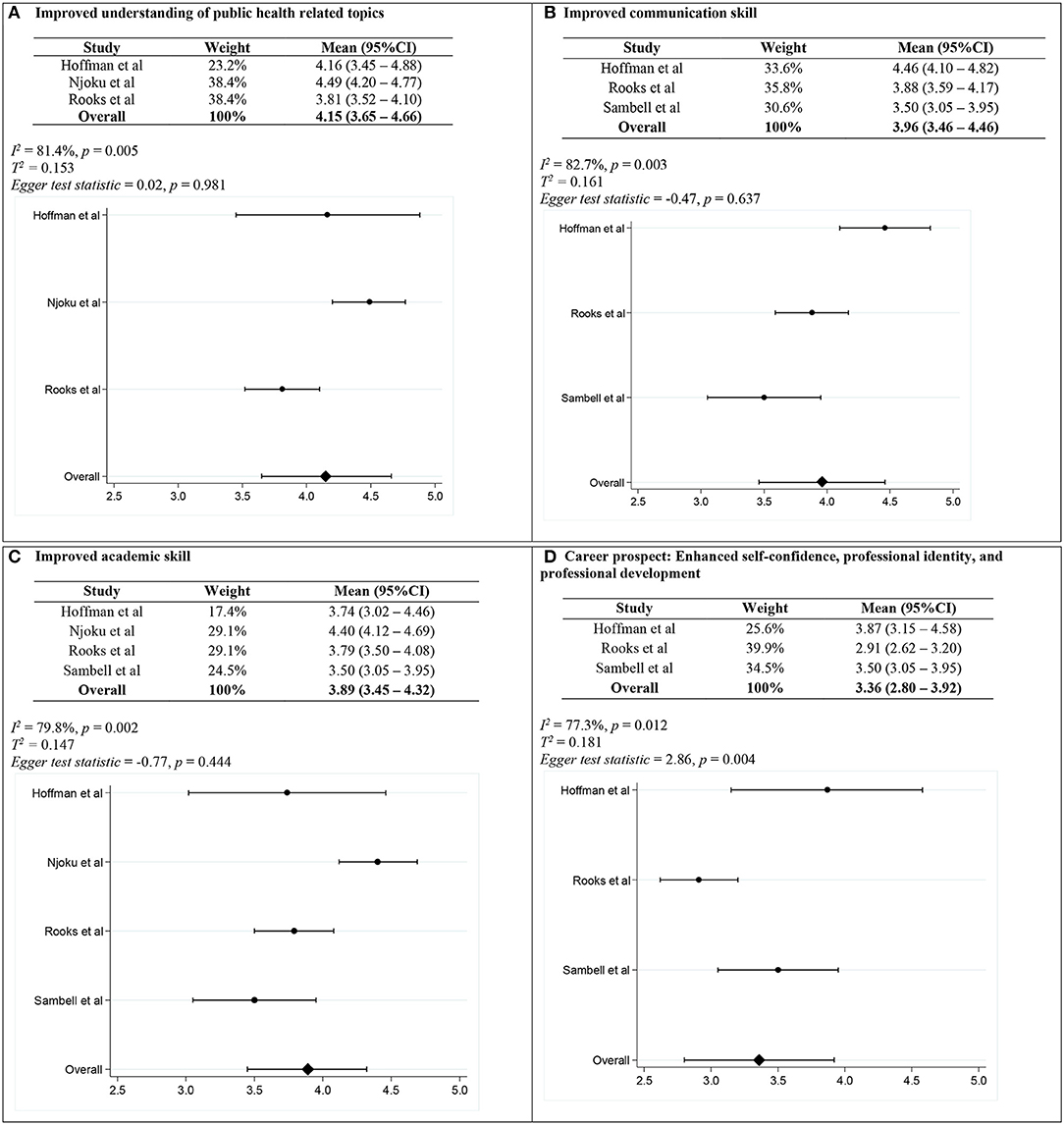

Most of the outcomes pertaining to the evaluation of self-reflection from the mixed-methods studies in this review were too heterogeneous to be combined. However, there were three to four studies that reported similar outcomes on understanding of public health related topics, career prospect (self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development), communication, and academic skill. Therefore, they were pooled for meta-analysis. Three studies were pooled for the outcome on understanding of public health related topics, three for career prospect, three for communication skill, and four for academic skill. The four outcomes were measured using a five-point Likert scale self-reported by students post-learning. The Inverse Variance method was used to pool the overall mean values of these outcomes across studies (Fleiss, 1993). For studies which published the mean values of outcome with more granular detail than required (e.g., communication skill with stratification by various aspects of communication from Hoffman and Silverberg, 2015), the overall mean value was derived using the average of the given mean values. For studies which published the median values (e.g., communication skill from Sambell et al., 2020), the overall mean value was derived using the given sample size, overall median, and range (Hozo et al., 2005). As all the studies did not publish the standard deviation (SD) of outcomes, this was imputed using sample size, interquartile range, and range, where available (Walter and Yao, 2007; Wan et al., 2014). The SDs were converted to standard errors to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) of pooled effect. Heterogeneity between the studies and sampling variance within the studies were assessed using the estimate of the absolute total observed variance T2 and proportion of the total observed variance from heterogeneity I2 (Higgins et al., 2003; Cheung, 2019). The low T2 and moderate to high I2 of the four outcomes indicated that the total observed variance was low and there was more heterogeneity than sampling error from the studies. Therefore, the random effects model with the method of moments was used for the four outcomes. The Egger test and funnel plot were used to detect publication bias. The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA SE 16 and the results were presented using forest plots.

In addition, we conducted a meta-synthesis on the levels and dimensions of reflectivity using the Mezirow's model of reflexivity, evaluation outcomes of self-reflection as well as the facilitators and barriers to deep self-reflection. Deep self-reflection was defined a priori as achieving any of the final three stages (conceptual reflectivity, psychic reflectivity, and theoretical reflectivity) of the critical consciousness level of the Mezirow's model of reflexivity (Mezirow et al., 2012). A thematic synthesis approach was used to gather information and identify all themes. We adapted the inductive analysis by Sandelowski and Barroso (Ludvigsen et al., 2016) which involved three stages: (1) extraction of findings and coding of findings for each article; (2) grouping of findings (codes) according to their topical similarity to determine whether findings confirm, extend, or refute each other; and (3) abstraction of findings (analyzing the grouped findings to identify additional patterns, overlaps, comparisons, and redundancies to form a set of concise statements that capture the content of findings). All stages were performed simultaneously as recommended (Ludvigsen et al., 2016). All data under Sections “Results,” “Discussion,” and “Conclusions” were read several times, and line by line. Relevant quotes were extracted, and these were analyzed and organized into codes and groupings. We used the process of constant comparative analysis. Emerging groupings from early codings were checked with ongoing coding and used to guide later coding (Ludvigsen et al., 2016). Final groupings were reviewed to ensure codings were similar in all groups and that no potential groupings were missed during the process (Ludvigsen et al., 2016). Prior to coding, the first two authors discussed, agreed upon, and demonstrated competency on the coding structure. After independently coding, both authors met to discuss coding inconsistencies. Cohen's kappa coefficient yielded a good agreement of 0.85. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus between both authors.

Our database and manual searches identified 1,351 citations (Figure 1). After removing 88 duplicates, 1,263 citations were reviewed using their titles and abstracts. Of these, 1,195 citations were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. After reading the remaining 68 articles, 14 were not relevant to self-reflection, 11 did not include evaluation results, five did not meet the target population criteria, and we were unable to isolate the results of undergraduate from the graduate population in four studies. The remaining 34 studies were included in our systematic review (Schaffer et al., 2005; Champagne, 2006; Brondani, 2010; Carroll and Mccarthy, 2010; Shepherd, 2010; Lee et al., 2011; Solomon and Risdon, 2011; Leipert and Anderson, 2012; Fortugno et al., 2013; Sendall and Domocol, 2013; Koh et al., 2014; Lencucha, 2014; Oakes and Sheehan, 2014; Stefaniak and Lucia, 2014; Hoffman and Silverberg, 2015; Karlsen et al., 2015; Krumwiede et al., 2015; McKay and Dunn, 2015; Babenko-Mould et al., 2016; Olson and Burns, 2016; Dundas et al., 2017; Padykula, 2017; Rooks and Holliman, 2018; Adams, 2019; Burnett and Akerson, 2019; Harver et al., 2019; Janssen Breen et al., 2019; Njoku and Ferris State University, 2019; Andina-Díaz, 2020; Chang and Chen, 2020; Harrison et al., 2020; Sambell et al., 2020; Suwanbamrung and Kaewsawat, 2020; Haffejee, 2021). Of the 34 studies, 29 reported qualitative evaluation results, and five reported mixed methods evaluation results. Four studies were used for meta-analysis (Hoffman and Silverberg, 2015; Rooks and Holliman, 2018; Njoku and Ferris State University, 2019; Sambell et al., 2020), and 34 were used for meta-synthesis.

Twenty-nine out of 34 studies (85.3%) were qualitative where qualitative descriptive design was the commonest (Table 1). The remaining five (14.7%) were mixed methods where all were of convergent design. On the type of students, more than two-fifths of the studies focused on healthcare professional students such as medical, dental, nursing, or allied health students taking public health as part of their curriculum. Nursing students was the commonest among these students. Another third of the studies targeted students in a major or a degree program in public health. The remaining one-quarter dealt with students from various disciplines such as nutrition, food technology, early childhood education, and child and youth care. There was a wide range of self-reflection formats used. Other than two studies which utilized a self-assessment tool for reflection, majority of the formats could be classified into four broad categories: (i) oral discussion, (ii) written assignment, (iii) photovoice, and (iv) portfolio. Common oral discussion formats included focus group discussions (FGDs), debrief and small group sharing, of which FGDs was the most popular. For written assignment, reflection paper was more popular than reflective journal. Studies that employed photovoice generally required students to take photographs in the community based on a public health topic so that they could reflect upon and explore the reasons, emotions and experiences that have guided their chosen images. For portfolio, the included studies generally required students to self-reflect on their service-learning project or degree program and then to collect evidence of their sample work, demonstrations, and artifacts that showcased their learning progression, competencies acquisition, and achievement. Out of the 34 studies, 24 used the format from only one category. The most common category utilized was the written assignment, followed by oral discussion, photovoice, and then portfolio.

The quality appraisal of the included studies is presented in Appendix 1. Thirty-one of the 34 studies fulfilled at least three out of five criteria outlined by the MMAT for each study design.

The meta-analysis of the common outcomes post-learning using the five-point Likert scale is shown in Figure 2. The higher the points reported the more favorable was the outcome. All four outcomes had a pooled mean of >3.0 indicating that students generally perceived an improvement for these outcomes post-learning. The pooled mean was the highest for having improved understanding of public health related topics at 4.15 (95%CI 3.65–4.66), followed by improved communication skill at 3.96 (95%CI 3.46–4.46), improved academic skill at 3.89 (95%CI 3.45–4.32), and then enhanced self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development at 3.36 (95%CI 2.80–3.92). In other words, students reported the most favorable outcome of self-reflection in increasing their understanding of public health related topics, followed by an improvement in their communication skill, then an improvement in their academic skill and finally an enhancement in their professional development at the end of learning.

Figure 2. Forest plots illustrating the pooled mean value for (A) understanding of public health related topics, (B) communication skill, (C) academic skill, and (D) career prospect.

The evaluation of the levels and dimensions of reflection using the Mezirow's model is shown in Table 2. Appendix 2 shows the illustrative quotes for the levels and dimensions of reflection. In general, students in most studies exhibited the consciousness category (reflectivity, affective reflectivity, discriminant reflectivity, and judgmental reflectivity) rather than the critical consciousness category (conceptual reflectivity, psychic reflectivity, and theoretical reflectivity). Within the consciousness category, students in almost all the studies displayed reflectivity (most superficial level). One example from Shepherd 2010 is “The emphasis that the alcoholic anonymous speakers made about the initial consumption being a choice made me reflect the most”. Other than reflectivity, these students also displayed discriminant reflectivity. One example from Sambell et al. (2020) is “The down point of the session was the introduction didn't provide a clear pathway for what the session was to entail and a couple of questions that didn't inspire responses from the participants. The challenging thing about the session was being mindful and ensuring no one was offended or uncomfortable.” Other levels in this category included affective reflectivity like Janssen Breen et al. (2019), “[I was] surprised that initially going in, thinking it was an area in need and that the parents were not going to be so involved—but they were” as well as judgmental reflectivity such as Lee et al. (2011), “I think the most important contribution that this process to my functioning as a health promoter is to look at issues on a more social rather than individualistic scale… I think that if a focus on health education and promotion was on strengthening communities, many societal problems would be decreased… If people felt fulfilled through friends and family perhaps, they would not feel the need to succumb to advertisements suggesting over-consumption”.

Within the critical consciousness category, the most common levels were conceptual and theoretical reflectivity. Students from Fortugno et al. (2013) exhibited conceptual reflectivity such as, “It almost makes me [wonder], do I want to work in a room full of [people of the same profession] now? Because we do come from the same basic perspective... Or would I almost prefer to work with a team of people who are [from different] professions, who give me all of those resources... and we get to collaborate?”. Students from seventeen studies displayed theoretical reflectivity where an example from Adams (2019) is, “We expect people to be able to make good health decisions. But if they don't have money or resources, it isn't that simple. I realize this now after this class.” The level least exhibited was psychic reflectivity involving only four studies. An example is Leipert and Anderson (2012), “The close-knit culture found within rural communities can often make it difficult for new residents to be accepted, as they may be viewed as strangers or outsiders”.

Table 3 shows the themes and subthemes on the outcomes of self-reflection across the reflection formats. Appendix 3 shows the illustrative quotes for the themes and subthemes on the outcomes of self-reflection. There were more positive than negative outcomes for each of the four formats of reflection (oral discussion, written assignment, photovoice, and portfolio) except for portfolio where positive outcomes were only reported. For all the formats of reflection, the top two positive outcomes were enhanced self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development and improved understanding on public health related topics. For the former, examples of quotes included, “I don't really say as much as I should be, but I think this has really showed me that I should [be more outspoken], especially in a professional aspect of it. I think I brought some valuable things to the table, and [I need to] express that.” (oral discussion, Fortugno et al., 2013), “I enjoyed and benefited from improving my interview skills and enhancing my professional role. I now understand the time and effort required to develop a safe, healthy community, and appreciate the efforts made by public health nurses.” (written assignment, Krumwiede et al., 2015), “I went to public places and people were looking at me whilst I was doing this. I explained to them about the campaign … I was feeling proud that I could explain to them what the campaign was about due to my knowledge and research on the campaign beforehand. Everyone gave me positive responses. I felt like a professional.” (photovoice, Dundas et al., 2017), and “These experiences improved my cultural competency, cross-cultural communication, ability to navigate ambiguous situations, and creativity regarding health communication materials. My experiences only reconfirmed for me that I want to continue working with diverse and vulnerable populations.” (portfolio, Harver et al., 2019). For the latter, examples of quotes included, “In all honesty, I think I was quite naïve as to what public health actually meant, thinking it was all posters and ad campaigns. Thankfully, this course has broadened my attitude and knowledge relating to public health, to the point where I would now want to focus my attention on preventative health rather than primary.” (written assignment, McKay and Dunn, 2015), and “I began to realise the extent to which public health issues encapsulate most aspects of my lifestyle and those around me. Whether it be my habitual hygiene practices and my knowledge of their purpose, or the unpolluted air I inhale, assured of its safety, I was swiftly made to acknowledge my own ignorance in taking such aspects for granted.” (photovoice, Dundas et al., 2017).

The next common positive outcomes included improved teamwork skills (oral discussion, written reflection, and photovoice) and improved empathy for the community (oral discussion, written reflection, and portfolio). For the former, examples of quotes included, “Being part of team teaching was helpful because you could pull from each other's strengths. Everyone brings a different experience to the team, and we learned a lot from each other. [You] need a team to teach; it is difficult for one person to teach a program.” (oral discussion, Janssen Breen et al., 2019), and “We have learnt to function well as a team, but vital to teamwork are communication, co-ordination, balanced member contributions, mutual support, effort and cohesion. Also, we learnt that the group leader needs to delegate.” (written reflection, Harrison et al., 2020). For the latter, examples of quotes included, “I found that the community itself had so much less than mine. The concerns that I have were...how can we help or improve lives here? Who do we go to—to advocate for them?... Being in the hospital we don't see what happens in the community...there is a huge difference in quality of life just 40 min away. The difference in the way the community presents itself—these children have every right to have what my kids have. How do we make this change for them?” (oral discussion, Janssen Breen et al., 2019), and “I learned that the prisoners are just real people who have gotten themselves into legal trouble. Before this experience I had always thought of prisoners as constantly being brutally mean and loud-mouthed people. Maybe some are, but it is not a constant personality trait. I felt a lot of sadness and compassion for the prisoners….” (portfolio, Schaffer et al., 2005).

For the negative outcomes, these varied across the different formats of reflection. There were still common outcomes such as lack of sufficient guidance and support from instructor (oral discussion and written assignment), and restriction by course/program requirements (oral discussion and written assignment). For the former, examples of quotes included, “The preceptors have no clue what we're doing, what we need.” (oral discussion, Schaffer et al., 2005) and “Tutorial briefing was too brief and not ‘structured' enough” (written assignment, Koh et al., 2014). For the latter, examples of quotes included, “I had to alter my writing to fit what they wanted to be more appropriate for the portfolio…I don't think it had to be so tight…to be reflective writing.” (oral discussion, Schaffer et al., 2005) and “I didn't like the models we had to follow. As a personal refection I think it should be just that, we should be able to write the way we want. However, it was probably put there for us to use for a good reason.” (written assignment, Sendall and Domocol, 2013).

Other common outcomes included unpleasant experience with teamwork (oral discussion and written assignment) and frustration with social injustice (written assignment and photovoice). For the former, examples of quotes included, “When I first came in, I was so terrified that I was going to step on anyone's toes... I was just scared that I was going to say something wrong, that I might be offensive to another profession.” (oral discussion, Fortugno et al., 2013) and “The most challenging part of working in a group was ensuring that all group members were doing an equal amount of work. For example, some people had to include more information in their part and ended up doing more work than others. In addition, it was hard to find days where everybody could meet, and not all team members were able to meet deadlines.” (written assignment, Rooks and Holliman, 2018). For the latter, examples of quotes included, “... disappointment that these women have had such an unfair experience in life and disgust that domestic violence is so prevalent within our society” (written assignment, Sambell et al., 2020) and “I still cannot understand how these people (Aboriginal Australians) have such poor health outcomes with little improvement in life expectancy when so much available [sic] to improve the social conditions. The more I read the angrier I be (sic).” (photovoice, Dundas et al., 2017).

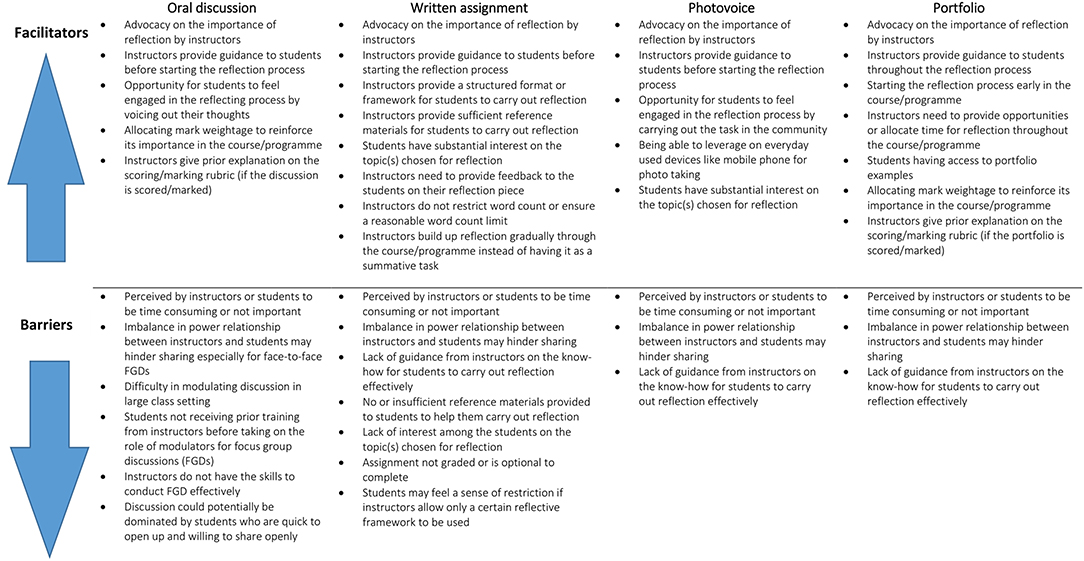

Figure 3 summaries the facilitators and barriers to performing deep self-reflection by students according to the different formats. While there were distinct facilitators and barriers for each format, there were certain similarities too. For example, there were two common facilitators, i.e., advocacy on the importance of reflection by instructors and instructors provide guidance to students before starting the reflection process. Simultaneously there were also two common barriers, i.e., perception by instructors/students to be time consuming or unimportant as well as the imbalance in power relationship between instructors and students. Another common barrier was the lack of guidance from instructors on the know-how for students to carry out reflection effectively for the formats of written assignment, photovoice and portfolio. Certain barriers were specific only to that format. For example, some barriers specific to oral discussion were difficulty in modulating discussion for large class size, instructors not having the skills to conduct FGDs effectively, and students not receiving prior training from instructors before taking on the role of modulators for FGDs.

Figure 3. Facilitators and barriers to performing deep self-reflection by students according to the different formats.

This was the first review consisting of a meta-analysis and a meta-synthesis to highlight the different formats of self-reflection used in public health education. Oral discussion and written assignment were more common reflection formats compared to photovoice and portfolio. The review also indicated that students in most studies were reflecting at the superficial rather than the deep level where the quotes pertained mainly to the dimensions of reflectivity and discriminant reflectivity of the Mezirow's model. While there was an overwhelmingly positive outcomes across the reflection formats, reported negative outcomes especially for portfolio were lacking. Both meta-analysis and meta-synthesis results revealed enhanced self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development as well as improved understanding of public health related topics. Two common facilitators to performing deep self-reflection by students included advocacy on the importance of reflection by instructors as well as instructors providing guidance to students before starting the reflection process. There were also two common barriers, i.e., perception by instructors/students to be time consuming or unimportant as well as the imbalance in power relationship between instructors and students.

Other than the conventional format of written assignment and oral discussion, other forms of self-reflection such as photovoice and portfolio are getting more popular. The nature of portfolio enables a student to not only display, but also to reflect on his or her achievements and competencies. This is relevant in health sciences and public health given the increasing emphasis of a competency-based, and reflective education (Gruppen et al., 2012; Fragkos, 2016). Even after graduation, students could still leverage on the portfolio to continue recording their professional development and hence helps in lifelong learning (Baris and Tosun, 2011). This is particularly so in public health as the graduate would often have to maintain proof of competency for further training and career advancement. The other increasingly popular self-reflection format is photovoice. This was originally created for research purposes to allow participants to capture photos for observation, discussion, and reflection (Kile, 2022). It has since then been applied in pedagogy including public health higher education (Leipert and Anderson, 2012; Andina-Díaz, 2020; Haffejee, 2021). This is not surprising given that public health has a strong emphasis on the community, and that photovoice creates a visual representation of theoretical concepts and learning experiences that might otherwise be challenging for some students to capture with words (Garner, 2013). Moreover, students might prefer this format compared to other forms because they could use the photographs to critically discuss the deep meanings and the symbolism these represent (Wilson et al., 2017).

One key finding was that students in most studies were not engaging in reflection at a deep level. This is consistent with studies from other disciplines (Richardson and Maltby, 1995; Sumsion and Fleet, 1996; Pee et al., 2002). When students first embark on their journey in higher education, they often tend to be superficial and merely descriptive in their reflections (Hatton and Smith, 1995). This is especially evident in junior undergraduate students where they would often prefer to focus on facts, principles, and procedures rather than engage in deep level reflective thinking (Veine et al., 2019). It is thus important to support students and carefully introduce reflection into their learning strategies through clear guidance and activities integrated into the course/program (Veine et al., 2019), as well as to ensure constructive alignment between reflection activities, assessment practices, and learning outcomes (Harvey et al., 2010). This is highly relevant in public health education where students usually come from diverse disciplines, and that their prior exposure to self-reflection would vary.

Despite the superficial level of reflection, several positives were also demonstrated. Students valued self-reflection in their respective public health course/program from the various positive outcomes in the meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. One such common outcome was improved understanding of public health related topics. Learning can be reinforced through reflective activities for students (e.g., Harvey et al., 2016). The ability to critically reflect is closely related to the higher order cognitive processes of self-regulation and metacognition and thus indicates the extent of the abstract level of learning attained (Paris and Winograd, 2003). Moreover, adopting a learner-centered approach to teaching allows students to take an active and reflective role in their own learning (Weimar, 2013). This approach is highly relevant in the training of public health professionals since there is usually a collective effort involving students, educators, and industry stakeholders.

Another positive common outcome was enhanced self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development. The landscape of higher education is rapidly changing. The role of universities is now not restricted to impart knowledge, but increasingly there is demand and pressure to prepare students for their future careers (Saito and Pham, 2021). Bramming (2007) further added that universities “must be concerned with transformative learning and education, which is then seen as a process where students are active participants, not consumers, users, or clients. Therefore, ample opportunities must be available for students to develop the professional, social, critical, cultural, and personal aspects of professional identity. This requires students to be actively engaged in their learning along with adequate guidance from educators. It is thus crucial to give reflection a central place in higher education to strengthen students” professional identity (Trede et al., 2012; Körkkö et al., 2016). Reflection connects new experiences with existing knowledge and skills in relation to the student's profession. This can give meaning to their experiences and lead to insights regarding their professional identity (Ayllón et al., 2019). It is thus important that students be provided with authentic experiences to reflect together with educators (Hunter et al., 2007). At the organizational, community and policy level, it will also be important to promote public health higher education programs that foster reflective professional practices (Trede et al., 2012).

Despite the overwhelmingly positive outcomes across the reflection formats, this review has demonstrated a lack of reported negative outcomes especially for portfolio. One reason could be the recent use of this reflection format in public health undergraduate education compared to other more established healthcare undergraduate disciplines like medicine or nursing. Studies from these disciplines reported that there were various negative outcomes in the use of portfolio. These included students viewing the portfolio as time consuming and do not see the importance of it (Abouzeid and Nasser, 2018; Al-Madani, 2019), insufficient feedback provided by the instructor, concerns with academic plagiarism (Al-Madani, 2019), dissatisfaction with the grading system as grading by instructors were inconsistent and guidance were not clear enough, and also students felt disengaged with the portfolio assessment (Vance et al., 2017; Fida et al., 2018; Al-Madani, 2019).

Given the review outcomes, educators, researchers in pedagogy, higher education curriculum or program developers should take note of the facilitators and barriers to performing deep self-reflection in Figure 3 when developing self-reflection activities for students in the future. One such common facilitator included advocacy on the importance of reflection by instructors and one such barrier included perception by instructors/students to be time consuming or unimportant. Therefore, for reflection to be effective in teaching, both educators and students must be convinced of its importance. Educators are directly responsible for the running of the classes and thus have an important role to play in advocacy. This means that educators need to be more active in the decisions that will shape students' lives (Roberts and Siegle, 2012). If teachers believe in the importance of reflection, they should be advocating for it by encouraging their students to reflect on, analyze, evaluate, and improve their own learning. In contrast, teachers who do not value reflection are not likely to motivate students to engage in reflection (Butani et al., 2017). Promoting reflective practice not only benefits teachers and students, but also the entire educational institution. Developing a culture of reflective practice improves the quality of education offered by institutes of higher learning. It also sends the message that reflective learning is important for both students and teachers, and that everyone is committed to supporting it.

Another common facilitator to performing deep self-reflection was that instructors need to provide guidance to students before starting the reflection process. Our review has revealed that students in most studies were reflecting at a superficial level. Therefore, educators must not assume students know how to reflect. Reflection is not easy, and for many students it is not natural. Students, particularly those in the first year of their undergraduate degree, require guidance on how to be reflective. Educators thus need to think strategically and logically about how to engage students in reflection. For junior students, a structured reflection guide could be used to aid their process in self-reflection compared to their senior counterparts who have some experience in reflection where they could engage in more “free form” reflection (Pee et al., 2002). Moreover, educators could further support students by providing sufficient relevant reference materials before the start of their reflection (Burnett and Akerson, 2019). Providing written or textual exemplars can also assist students to understand the distinctions between levels of reflection and enlighten them as to how to critically reflect (Moon, 2013). That is students should be supported via a scaffolding process where educators developed structured activities that progressively increase students' abilities to engage in deep reflection while gradually reducing teachers' guidance (Coulson and Harvey, 2013). However, there are various teaching and epistemological structures in connection to reflective practice and with this a need to recognize that not all teachers are disposed to reflect, nor are they able to effectively teach critical reflection (Kreber and Castleden, 2009). Therefore, at the organizational level, higher educational institutions could better support educators especially junior teachers through provision of training and peer support. As a start, teachers could be trained to improve their understanding toward reflection assessment, especially with regards to potential issues of consistency, appropriate assessment criteria, and fairness (Chan and Lee, 2021). In addition, pertaining to certain reflection formats such as oral discussion, our review has demonstrated that if educators choose this format for students, they will need to be trained to modulate discussion for large class size, be equipped with the skills to conduct FGDs effectively, and be comfortable to train students to be modulators for FGDs.

Another common barrier to performing deep self-reflection was the imbalance in power relationship between instructors and students which may hinder sharing. Power exists in all human relationships in diverse ways and extents. This includes teacher-student interactions. Teacher use of power in learning environments warrants continued attention because it strongly influences teacher-student relationships, students' motivation to learn, and learning outcomes (Mottet et al., 2006; Schrodt et al., 2008; Fin, 2012). Paying attention to power in learning environments is important when students are asked to self-reflect. Other than allowing students to feel less restricted when it comes to having to share their reflection with teachers, power-sharing could promote deep reflection. To facilitate this, educators could create a conductive environment by encouraging students to share their reflective thoughts freely and openly. Moreover, educators could promote the norm of sharing at an equal level in their classroom by sharing their own reflective thoughts too. The goal would be to create a critical and yet democratic classroom environment in which all members have equal opportunity to speak their mind, all members respect other members' rights to speak and feel safe to speak (Breunig, 2005).

The various facilitators and barriers identified in this review served as consideration in promoting reflective practice in public health higher education. These factors are often interconnected and remind us of the need to promote deep self-reflection across all levels from students to teachers and even educational institutions. Because perceptions of learning environments varied between institutions, programs, teachers and students, efforts to evaluate the implementation feasibility of these facilitators and barriers need to take place across the different levels. Most of these facilitators and barriers were clustered at the teacher-pedagogical and student learning levels, hence these should be targeted first before moving to the institutional and sociocultural factors which might require more time to change. As a start, peer ambassadors or champions could be appointed at the student level to change the common perception that performing deep self-reflection was time consuming. If student ambassadors or champions work collaboratively with their peers, it might be easier to forge meaningful connections and to modify their perceptions (Gartland, 2014). Similarly, at the teacher level, faculty learning communities could be set up for like-minded educators to advocate on the importance of reflection and to share their experience on balancing the power relationship between instructors and students. They could thus serve as a valuable resource of information and support for peers to learn new pedagogical skills from, and to share meaningful instructional practice in a safe space (Lapoint, 2021).

There were several strengths and limitations of our current review. One strength was the moderate to high quality of the included studies, with more than 90% of the included studies having at least half of the criteria assessed to be at low risk of bias. Another strength was the use of both meta-analysis and meta-synthesis results to achieve methodological triangulation. Nevertheless, there were also a few limitations. As there were at most four studies for each outcome in our meta-analysis, the small number has limited our ability to estimate the possible correlation among the four outcomes (understanding of public health related topics, communication skill, academic skill, and career prospect). Publication bias could not be excluded since there was a likelihood that interventions without significant or positive evaluation results were not published. Moreover, as we focused largely on electronic databases, many self-reflection activities conducted by Schools of Public Health or universities might not be reported in journals or be published. The low T2 and moderate to high I2 from the heterogeneity test of each outcome indicated that the total observed variance was low and there was more heterogeneity than sampling error from the studies. While no publication bias was detected for the outcomes on understanding of public health related topics, communication skill and academic skill, we could not rule this out for career prospect where the Egger test p-value was 0.004. The estimated standard error from some studies were indeed larger and such studies carried lower weight when they were pooled with other studies for the same outcome. Despite this, all studies reported the same direction for each of the outcomes which aligned with our pooled results. In addition, great care was taken to ensure that we included only studies that measured similar outcome and the random effects models were used. Another limitation was a general lack of reported negative outcomes especially for the format of portfolio. It is also important to note that reflection is not solely a cognitive process, but also an affective process where emotions and feelings are often expressed. While the cognitive aspects of reflection might potentially be objectively measured or quantified, the same cannot be said for the emotional aspect. Because reflection is a metacognitive process, the existing formats of outcome assessment described in this review are probably indirect rather than direct measurements of self-reflection. Despite this, our review has elicited the various facilitators and barriers to performing deep self-reflection based on the common formats of reflection used in public health. Awareness of these findings will be important to increase understanding about the reflection process, develop effective educational strategies, and to better interpret assessment results to promote deep learning in public health students.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review to illustrate the various self-reflection formats used in public health education. Using meta-analysis and meta-synthesis, we have achieved the study objectives of (1) describing the range of self-reflection formats used in public health undergraduate education, (2) comparing the level of reflectivity and outcomes of self-reflection according to the common formats of self-reflection used, and (3) comparing the facilitators and barriers to deep self-reflection based on the common formats of self-reflection used. Most students were not engaging in reflection at a deep level. While there was an overwhelmingly positive outcomes across the reflection formats, there was in general a lack of reported negative outcomes especially for the format of portfolio. Both meta-analysis and meta-synthesis results revealed enhanced self-confidence, professional identity, and professional development as well as improved understanding of public health related topics. Future educational programs should consider the common facilitators to deep self-reflection, i.e., advocacy on the importance of reflection by instructors and provision of guidance to students as well as the common barriers, i.e., perception by instructors/students to be time consuming or unimportant as well as the imbalance in power relationship between instructors and students. Because perceptions of learning environments varied between institutions, programs, teachers and students, efforts to evaluate the implementation feasibility of these facilitators and barriers need to take place across the different levels. As a start, peer ambassadors or champions could be appointed at the student level to change the common perception that performing deep self-reflection was time consuming. Similarly, at the teacher level, faculty learning communities could be set up for like-minded educators to advocate on the importance of reflection and to share their experience on balancing the power relationship between instructors and students.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors contributed significantly to the drafting and revision of the manuscript, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.938224/full#supplementary-material

CI, Confidence Interval; ERIC, Education Resources Information Center; FGDs, Focus Group Discussions; MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; USA, United States of America.

Abouzeid, E., and Nasser, A. A. (2018). Evaluation of the portfolio's implementation in clinical clerkship: students' and staff's perception in Egypt. J. Med. Educ. 17, 205–214. doi: 10.22037/jme.v17i4.23742

Adams, S. B. (2019). Inspiring empathy and policy action in undergraduate students: monopoly as a strategy. J. Nurs. Educ. 58, 298–301. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20190422-09

Al-Madani, M. (2019). Exploring undergraduate nursing students' perceptions about using portfolios in nursing education. IJNHS. 4, 081. doi: 10.29011/IJNHR-081.1000081

Andina-Díaz, E. (2020). Using photovoice to stimulate critical thinking: an exploratory study with Nursing students. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 28, e3314. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.3625.3314

Artioli, G., Deiana, L., De Vincenzo, F., Raucci, M., Amaducci, G., Bassi, M. C., et al. (2021). Health professionals and students' experiences of reflective writing in learning: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Med. Educ. 21, 394. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02831-4

Ayllón, S., Alsina, Á., and Colomer, J. (2019). Teachers' involvement and students' self-efficacy: keys to achievement in higher education. PLoS ONE. 14, e0216865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216865

Babenko-Mould, Y., Ferguson, K., and Atthill, S. (2016). Neighbourhood as community: a qualitative descriptive study of nursing students' experiences of community health nursing. Nurse Educ. Pract. 17, 223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2016.02.002

Baris, M. F., and Tosun, N. (2011). E-portfolio in lifelong learning applications. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 28, 522–525. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.100

Biggs, J. (2012). What the student does: teaching for enhanced learning. High Educ. Res. Dev. 31, 39–55. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.642839

Bramming, P. (2007). An argument for strong learning in higher education. Qual. High. Educ. 13, 45–56. doi: 10.1080/13538320701272722

Breunig, M. (2005). Turning experiential education and critical pedagogy theory into Praxis. J. Exp. Educ. 28, 106–122. doi: 10.1177/105382590502800205

Brondani, M. A. (2010). Students' reflective learning within a community service-learning dental module. J. Dent. Educ. 74, 628–636. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2010.74.6.tb04908.x

Brownhill, S. (2021). Asking key questions of self-reflection. Reflective Pract. 23, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.1976628

Bubnys, R., and Zydziunaite, V. (2010). Reflective learning models in the context of higher education: concept analysis. Prob. Educ. 21st Century 20, 58–70. Available online at: http://oaji.net/articles/2014/457-1400134170.pdf

Burnett, A. J., and Akerson, E. (2019). Preparing future health professionals via reflective pedagogy: a qualitative instrumental case study. Reflect. Pract. 20, 571–583. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2019.1651711

Butani, L., Bannister, S. L., Rubin, A., and Forbes, K. L. (2017). How educators conceptualize and teach reflective practice: a survey of north American pediatric medical educators. Acad. Pediatr. 17, 303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.008

Carroll, J., and Mccarthy, R. (2010). “Geekdom for Grrrls health: Australian undergraduate experiences developing and promoting women's health in cyberspace,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Research and Innovation (Madrid).

Champagne, N. (2006). Using the NCHEC areas of responsibility to assess service learning outcomes in undergraduate health education students. Am. J. Health Promot. 37, 137–145. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2006.10598893

Chan, C. K. Y., and Lee, K. K. W. (2021). Reflection literacy: a multilevel perspective on the challenges of using reflections in higher education through a comprehensive literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 32, 100376. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100376

Chang, Y.-Y., and Chen, M.-C. (2020). Using reflective teaching program to explore health-promoting behaviors in nursing students. J. Nurs. Res. 28, e86. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000358

Cheung, M. W.-L. (2019). A guide to conducting a meta-analysis with non-independent effect sizes. Neuropsychol. Rev. 29, 387–396. doi: 10.1007/s11065-019-09415-6

Christie, M., and de Graaff, E. (2017). The philosophical and pedagogical underpinnings of active learning in engineering education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 42, 5–16. doi: 10.1080/03043797.2016.1254160

Coulson, D., and Harvey, M. (2013). Scaffolding student reflection for experience-based learning: a framework. Teach. High Educ. 18, 401–413. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2012.752726

Dundas, K. J., Hansen, V., Outram, S., and James, E. L. (2017). A ‘light bulb moment' in understanding Public Health for undergraduate students: evaluation of the experiential ‘This is Public Health' photo essay task. Front. Public Health. 5, 116. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00116

Fida, N. M., Hassanien, M., Shamim, M. S., Alafari, R., Zaini, R., Mufti, S., et al. (2018). Students' perception of portfolio as a learning tool at King Abdulaziz University Medical School. Med. Teach. 40, S104–S113. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1466054

Fin, A. N. (2012). Teacher use of prosocial and antisocial power bases and students' perceived instructor understanding and misunderstanding in the college classroom. Commun. Educ. 1, 67–79. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2011.636450

Fleiss, J. L. (1993). The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2, 121–145. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200202

Fortugno, M., Chandra, S., Espin, S., and Gucciardi, E. (2013). Fostering successful interprofessional teamwork through an undergraduate student placement in a secondary school. J. Interprof. Care. 27, 326–332. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.759912

Fragkos, K. (2016). Reflective practice in healthcare education: an umbrella review. Educ. Sci. 6, 27. doi: 10.3390/educsci6030027

Garner, S. (2013). Picture this! Using photovoice to facilitate cultural competence in students. J. Christ. Nurs. 30, 155–157. doi: 10.1097/CNJ.0b013e31829493a0

Gartland, C. (2014). Student ambassadors: “role-models”, learning practices and identities. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 36, 1192–1211. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2014.886940

Gläser-Zikuda, M. (2012). Self-Reflecting Methods of Learning Research in Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Boston, MA: Springer US, 3011–3015.

Gruppen, L. D., Mangrulkar, R. S., and Kolars, J. C. (2012). The promise of competency-based education in the health professions for improving global health. Hum. Resour. Health. 10, 43. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-43

Haffejee, F. (2021). The use of photovoice to transform health science students into critical thinkers. BMC Med. Educ. 21, 237. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02656-1

Harrison, S. G. D., Scheepers, J., Christopher, L. D., and Naidoo, N. (2020). Social determinants of health in emergency care: an analysis of student reflections on service-learning projects. Afr. J. Health Sci. 12, 22. doi: 10.7196/AJHPE.2020.v12i1.1152

Harver, A., Zuber, P. D., and Bastian, H. (2019). The capstone ePortfolio in an undergraduate Public Health program: accreditation, assessment, and audience. Front. Public Health. 7, 125. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00125

Harvey, M., Coulson, D., and McMaugh, A. (2016). Towards a theory of the ecology of reflection: reflective practice for experiential learning in higher education. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 13, 7–27. doi: 10.53761/1.13.2.2

Harvey, M., Coulson, D., Mackaway, J., and Winchester-Seeto, T. (2010). Aligning reflection in the cooperative education curriculum. APJCE. 11, 137–152. Available online at: https://www.ijwil.org/files/APJCE_11_3_137_152.pdf

Hatton, N., and Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 11, 33–49. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., and Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 327, 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Hoffman, S. J., and Silverberg, S. L. (2015). Training the next generation of global health advocates through experiential education: a mixed-methods case study evaluation. Can. J. Public Health. 106, e442–e449. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.106.5099

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., et al. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 34, 285–291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

Hozo, S. P., Djulbegovic, B., and Hozo, I. (2005). Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 5, 13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13

Hunter, A.-B., Laursen, S. L., and Seymour, E. (2007). Becoming a scientist: the role of undergraduate research in students' cognitive, personal, and professional development. Sci. Educ. 91, 36–74. doi: 10.1002/sce.20173

Jackson, K., Lower, C. L., and Rudman, W. J. (2016). The Crossroads between workforce and education. Perspect Health Inf. Manag. 13, 1g.

Janssen Breen, L., Diamond-Caravella, M., Moore, G., Wruck, M., Guglielmo, C., Little, A., et al. (2019). When reach exceeds touch: student experiences in a cross-sector community-based academic-practice partnership. Public Health Nurs. 36, 429–438. doi: 10.1111/phn.12599

Jayatilleke, N., and Mackie, A. (2013). Reflection as part of continuous professional development for public health professionals: a literature review. J. Public Health. 35, 308–312. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds083

Kanchanachitra, C., Lindelow, M., Johnston, T., Hanvoravongchai, P., Lorenzo, F. M., Huong, N. L., et al. (2011). Human resources for health in southeast Asia: shortages, distributional challenges, and international trade in health services. Lancet. 377, 769–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62035-1

Karlsen, H., Mehli, L., Wahl, E., and Staberg, R. L. (2015). Teaching outbreak investigation to undergraduate food technologists. Br. Food J. 117, 766–778. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-02-2014-0062

Kile, M. (2022). Uncovering social issues through photovoice: a comprehensive methodology. HERD. 15, 29–35. doi: 10.1177/19375867211055101

Kiviniemi, M. T., and Mackenzie, S. L. C. (2017). Framing undergraduate public health education as liberal education: who are we training our students to be and how do we do that? Front. Public Health. 5, 9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00009

Koh, Y. H., Wong, M. L., and Lee, J. J.-M. (2014). Medical students' reflective writing about a task-based learning experience on public health communication. Med. Teach. 36, 121–129. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.849329

Koole, S., Dornan, T., Aper, L., Scherpbier, A., Valcke, M., Cohen-Schotanus, J., et al. (2011). Factors confounding the assessment of reflection: a critical review. BMC Med. Educ. 11, 104. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-104

Körkkö, M., Kyrö-Ämmälä, O., and Turunen, T. (2016). Professional development through reflection in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 55, 198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.014

Kreber, C., and Castleden, H. (2009). Reflection on teaching and epistemological structure: reflective and critically reflective processes in ‘pure/soft' and ‘pure/hard' fields. High Educ. 57, 509–531. doi: 10.1007/s10734-008-9158-9

Krumwiede, K. A., Van Gelderen, S. A., and Krumwiede, N. K. (2015). Academic-hospital partnership: conducting a community health needs assessment as a service learning project. Public Health Nurs. 32, 359–367. doi: 10.1111/phn.12159

Lapoint, P. A. (2021). Learning communities: factors influencing faculty involvement. J. Higher Educ. Theory Pract. 21, 4659. doi: 10.33423/jhetp.v21i11.4659

Lee, B. K., Yanicki, S. M., and Solowoniuk, J. (2011). Value of a health behavior change reflection assignment for health promotion learning. Educ. Health. 24, 509. Available online at: https://www.educationforhealth.net/text.asp?2011/24/2/509/101439

Leipert, B., and Anderson, E. (2012). Rural nursing education: a photovoice perspective. Rural Remote Health. 12, 2061. doi: 10.22605/RRH2061

Lencucha, R. (2014). A research-based narrative assignment for global health education. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 19, 129–142. doi: 10.1007/s10459-013-9446-8

Ludvigsen, M. S., Hall, E. O., Meyer, G., Fegran, L., Aagaard, H., and Uhrenfeldt, L. (2016). Using Sandelowski and Barroso's meta-synthesis method in advancing qualitative evidence. Qual. Health Res. 26, 320–329. doi: 10.1177/1049732315576493

Luu, X., Dundas, K., and James, E. L. (2019). Opportunities and challenges for undergraduate public health education in Australia and New Zealand. Pedag. Health Promot. 5, 199–207. doi: 10.1177/2373379919861399

Mann, K., Gordon, J., and MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 14, 595–621. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

Marshall, T. (2019). The concept of reflection: a systematic review and thematic synthesis across professional contexts. Reflect. Pract. 20, 396–415. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2019.1622520

McKay, F. H., and Dunn, M. (2015). Student reflections in a first year public health and health promotion unit. Reflect. Pract. 16, 242–253. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2015.1005588

Mezirow, J., Taylor, E. W., and Cranton, P. (2012). The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miller, J. M., Ford, S. F., and Yang, A. (2020). Elevation through reflection: closing the circle to improve librarianship. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 108, 353–363. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2020.938

Mottet, T. P., Richmond, V. P., and Mccroskey, J. C. (2006). Handbook of Instructional Communication: Rhetorical and Relational Perspectives. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Njoku, A., and Ferris State University. (2019). Learner-centered teaching to educate college students about rural health disparities. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 16, 69–85. doi: 10.53761/1.16.5.6

Oakes, C. E., and Sheehan, N. W. (2014). Students' perceptions of a community-based service-learning project related to aging in place. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 35, 285–296. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2014.907158

Olson, R., and Burns, E. (2016). Teaching sociology to public health students: consumption as a reflective learning tool. FoHPE. 17, 71. doi: 10.11157/fohpe.v17i1.123

Padykula, B. M. (2017). RN-BS students' reports of their self-care and health-promotion practices in a holistic nursing course. J. Holist. Nurs. 35, 221–246. doi: 10.1177/0898010116657226

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372, 71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Paris, S. G., and Winograd, P. (2003). The Role of Self-Regulated Learning in Contextual Teaching: Principals and Practices for Teacher Preparation, (Washington, DC).

Pee, B., Woodman, T., Fry, H., and Davenport, E. S. (2002). Appraising and assessing reflection in students' writing on a structured worksheet: appraising and assessing reflection in students' writing,” Med. Educ. 36, 575–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01227.x

Petersen, D. J., and Weist, E. M. (2014). Framing the future by mastering the new public health. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 20, 371–374. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000106

Resnick, B., Leider, J. P., and Riegelman, R. (2018). The landscape of US undergraduate public health education. Public Health Rep. 133, 619–628. doi: 10.1177/0033354918784911

Richardson, G., and Maltby, H. (1995). Reflection-on-practice: enhancing student learning. J. Adv. Nurs. 22, 235–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22020235.x

Riegelman, R. K., Albertine, S., and Wykoff, R. (2015). A history of undergraduate education for public health: from behind the scenes to center stage. Front. Public Health. 3, 70. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00070

Roberts, J. L., and Siegle, D. (2012). Teachers as advocates: if not you—who? Gift Child Today. 35, 58–61. doi: 10.1177/1076217511427432

Rooks, R. N., and Holliman, B. D. (2018). Facilitating undergraduate learning through community-engaged problem-based learning. IJ-SoTL. 12, 209. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2018.120209

Saito, E., and Pham, T. (2021). A comparative institutional analysis on strategies deployed by Australian and Japanese universities to prepare students for employment. High Educ. Res. Dev. 40, 1085–1099. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1800596

Sambell, R., Devine, A., Lo, J., and Lawlis, T. (2020). Work-integrated learning builds student identification of employability skills: utilizing a food literacy education strategy. Int. J. Work-Integr Learn. 21, 63–87. Available online at: https://www.ijwil.org/files/IJWIL_21_1_63_87.pdf

Schaffer, M. A., Nelson, P., and Litt, E. (2005). Using portfolios to evaluate achievement of population-based public health nursing competencies in baccalaureate nursing students. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 26, 104–112. Available online at: https://journals.lww.com/neponline/Abstract/2005/03000/USING_PORTFOLIOS_TO_Evaluate_Achievement_of.10.aspx

Schrodt, P., Witt, P. L., Myers, S. A., Turman, P. D., Barton, M. H., and Jernberg, K. A. (2008). Learner empowerment and teacher evaluations as functions of teacher power use in the college classroom. Commun. Educ. 57, 180–200. doi: 10.1080/03634520701840303

Sendall, M. C., and Domocol, M. L. (2013). Journalling and public health education: thinking about reflecting. Educ. Train. 55, 52–68. doi: 10.1108/00400911311294997

Shepherd, R. (2010). If these walls could talk: reflective practice in addiction studies among undergraduates in New Zealand. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 8, 583–594. doi: 10.1007/s11469-009-9235-z

Solomon, P., and Risdon, C. (2011). Promoting interprofessional learning with medical students in home care settings. Med. Teach. 33, e236–e241. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.558534

Stefaniak, J. E., and Lucia, V. C. (2014). Physician as teacher: promoting health and wellness among elementary school students. Educ. Health. 27, 183–187. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.143785

Sumsion, J., and Fleet, A. (1996). Reflection: can we assess it? Should we assess it? Assess Eval. High Educ. 21, 121–130. doi: 10.1080/0260293960210202

Suwanbamrung, C., and Kaewsawat, S. (2020). Public health students' reflection regarding the first case of Coronavirus disease 2019 in a university, southern Thailand. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 1, 182–192. doi: 10.36502/2020/hcr.6177

Trede, F., Macklin, R., and Bridges, D. (2012). Professional identity development: a review of the higher education literature. Stud. High Educ. 37, 365–384. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2010.521237