- Department of Pedagogy and Learning, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

This article presents the results and experiences on parents’ perspectives of belonging in early years education. The study aimed to investigate how the parents assess the fulfilment of the inclusion goals that apply to the Swedish pre-school activities. Another aim was to learn about the parents’ perspectives on factors and pedagogical approaches that promote diversity and belonging. The study involves the answers from 454 parents/guardians of pre-school pupils. When the parents were asked directly if their children were excluded by others in the group, 14% stated it was true. The present study tried to find factors and connections to strengthen the pre-school’s inclusive working methods. One way to have children become more included in the group is to get the parents more involved and familiar with activities and for the staff to convey the goals that apply to activities.

Introduction

An inclusive and solid pre-school where children with different backgrounds and skills meet our essential to defend a democratic society. Educating and learning together are fundamental to living and working together later in life (Karlsudd, 2017). Given values based on social justice and the equal right to participation, there is a principle that all people, regardless of their condition, interests, and performance capabilities, can contribute. This means seeing the importance of the group’s differences and individualizing within the framework of society. Differences become resources and not problems (Stukat, 1995). It is vital to work inclusively early to feel a sense of belonging. There are relatively few studies on how children’s belonging in ECE (Early Childhood Education) is embodied. Despite the growing interest in preventing children’s exclusion and enhancing their belonging, there is still a need for more profound knowledge about how belonging is realized (Johansson, 2017).

According to Swedish school law (SFS, 2010:800) and the pre-school curriculum (Skolverket, 2018), activities “must be adapted to all children in the pre-school, regardless of such traits as ethnic affiliation, religion, or disability” (p. 6). Concepts often associated with adaptation are needed, such as inclusion. “Included” as a goal stands for all children to be equally involved in the same activity regardless of differences. Inclusion as a method describes a process in which special efforts are deemed necessary to accept every individual’s differences (Karlsudd, 2017, 2021).

Another concept besides “included” describing how well a programme embraces all children is a “sense of belonging.” The meaning of the term “belonging” can be explained by a slight rephrasing of the definition formed by Emanuelsson (1996, p. 11): “When the absence from a group or of a group member feels like a minus, as something negative, then a two-way sense of belonging has developed”. A sense of belonging is essential for children in pre-school. The feeling, in essence, must be mutual between a group and an individual, and a permissive, caring atmosphere is necessary. Cohesion and safety appear in Eek-Karlsson and Emilson’s (2021) study as a collectively oriented aspect. A caring and loving approach and protecting the child’s integrity are perceived more as individual-oriented. Balancing between the collective and the individually trained beliefs is a challenge. Differentiating solutions and special groups frequently appear in compulsory school (Giota and Emanuelsson, 2011; Karlsudd, 2012), while these have been unusual in pre-schools. As the pre-school has been more strongly required to be a learning environment (Palla, 2011), collective goals have been placed in the background for the sake of more individualistically tinged arguments and objectives that accentuate the vulnerability of resource-poor children.

The pre-school staff is expected to regulate the activities to include all children. They must guide and work toward common values while at the same time striving for the children to develop specific skills. The staff’s task will thus be to homogenize while at the same time opening for heterogeneity which many researchers believe has become more difficult in the last decade (Dahlberg et al., 2014; Lindberg, 2018; Nilfyr, 2018).

The feeling of being included in a positive context, with stable peer contacts, and having good social relationships are essential for a well-functioning learning situation (Holfve-Sabel, 2006). Pre-schools should pay attention to all individuals and the group (Einarsdottir et al., 2015). Experiences of inclusion and exclusion processes make this task easier (Juutinen and Kess, 2019). Unconsciously and thoughtfully working with inclusion, parents’ opinions, knowledge, and insights about their children are a given and essential part of this work. This study is an attempt to reach parents’ views and experiences.

Role of Parents

A sense of belonging can be seen as every child’s right (Johansson and Einarsdottir, 2018). If a child repeatedly feels excluded during their upbringing, it can have long-term negative consequences (Juutinen, 2018). In times of increased individualization, migration and globalization, the risk of exclusion seems more significant than ever (Riddersporre and Persson, 2017; Karlsudd, 2021). Good contact with children’s parents, especially the parents of children assessed to have special needs, is of great importance for shaping a sense of belonging in an inclusive programme. This group of parents sees the pre-school as holistic and does not separate different quality factors from each other. Therefore, it can be extra valuable to be sensitive to these parents (Glenn-Applegate et al., 2011). Communication and information working well in both directions facilitate inclusion (Mitchell, 2008). When parents in an atmosphere of respect become involved in the pre-school’s activities, the opportunities for an inclusive activity increase (Morrone and Matsuyama, 2020). High quality in pre-school is often linked to high parental participation (Bulotsky-Shearer et al., 2012). The pre-school’s opportunity to work for social equality increases as the activity is inclusive for parents and guardians (Crosnoe et al., 2012; Abreu-Lima et al., 2013; Pinto et al., 2013). Availability and inclusion are linked to influence. If the parents’ involvement increases, it has a leveling effect in that it contributes to children gaining a sense of belonging (Jensen et al., 2012). Nordic studies indicate that inclusion and exclusion processes already occur in pre-school, in the interaction between children and the interaction between educators and children and between educators and parents (Bundgaard and Gulløv, 2008; Jensen, 2009). Good contact between the child’s parents and the pre-school generally contributes positively to a child’s short- and long-term development (Nielsen and Christoffersen, 2009). Two things are achieved by listening to parents and seeing the pre-school’s activities. Firstly, the pre-school activities are enriched by other voices being heard, and secondly, the parents’ understanding of pre-school can increase their social and cultural capital (Nielsen and Christoffersen, 2009).

Role of Pre-school Staff

Different challenges related to children’s sense of belonging in ECE practices are exposed in previous research. One challenge concerns educators’ conceptual understanding of belonging and how to convert these views into practice (Tillet and Wong, 2018). Earlier studies have shown that staff attitude is of great weight for an inclusive programme (Lindsay, 2007; Elliot, 2008). Boldermo (2020) calls for educators’ awareness to ensure inclusive practises for young children. A teacher’s empathetic attitude increases the children’s capacity to respect and understand other individuals (Dysthe, 2010; Gerrbo, 2012) and a devoted and cheerful teacher is more successful. Pre-school staff must discuss and take a position on which view of the child and knowledge will form pedagogical strengths (Karlsudd, 2012). The feeling of belonging in a context is also primary for inclusion to be working (Persson and Persson, 2012), and therefore, collaboration among colleagues should be stimulated. Everyone in the work team possesses the competence, and by reflecting together, different problems can be seen from different viewpoints. One suggestion for developing and deepening the discussions is to talk about a glimpse or moment of a sense of belonging (Emilson and Eek-Karlsson, 2021). This way, educators understand different situations and what measures should be taken, contributing to a more inclusive group of children (Boyle et al., 2011).

The teacher’s education and knowledge are essential for children’s development and learning (Hattie, 2009; Reite and Haug, 2019; Karlsudd, 2020). Skills regarding an inclusive approach come from teacher education, which is unluckily often insufficient (Vickerman, 2012). Teachers, therefore, demand more continuing education and support to work inclusively, which is noted in several studies (Avramidis and Kalyva, 2007; Sari et al., 2009; De Boer et al., 2011; Vitalaki et al., 2018). If teacher education provides teachers with the tools and self-confidence to see opportunities with inclusion, this leads to positive attitudes regarding inclusion (Feng and Johnson, 2008). Previous studies have shown that teachers are generally positive or neutral toward inclusion (Ali et al., 2006; Avramidis and Kalyva, 2007; Sari et al., 2009). However, some are negative about working inclusively in their groups and classes (Avramidis and Kalyva, 2007). Some studies report an apparent reluctance to be inclusive (Chuckle and Wilson, 2002; Singhania, 2005).

Participation and belonging are essential for self-esteem and strengthening group belonging (Asp-Onsjö, 2010). The fact that pupils are actively involved in planning is also highlighted in earlier studies (Szönyi, 2005; Brodin and Lindstrand, 2010). Previous research shows that children are seldom listened to for their thoughts about learning (Lindroth, 2018). Teachers would go farther in their teaching if pupils gained more influence and heard their unique experiences (Feng and Johnson, 2008).

Inclusive Activities

For each child to feel a sense of belonging, each teacher must adapt tasks and activities to the circumstances of individual children (Gerrbo, 2012). Juutinen et al. (2018) stress that the process of belonging deals with tensions between inclusion and exclusion. It is therefore essential to find each student’s strengths and appropriate pedagogical methods to promote these. Children’s self-esteem is strengthened through this approach. Mutual perceptions and attitudes toward other individuals can be positively influenced (Linikko, 2009). Educators who are sensitive to children’s interests can identify exciting areas of knowledge for all children (Bråten, 2011). It is a qualified task, of course, for educators to get children to participate in joint activities, as at the same time, the pupils must be challenged based on their abilities and needs (Nilholm, 2005). Hindrances to or opportunities for participation can be created depending on how the physical environment is designed (Frithiof, 2007). A study of children’s belonging to peer communities in Norwegian pre-school education shows how different conditions for belonging are created in different kinds of societies (Johansson and Rosell, 2021). In a study about Polish children’s experiences of their migration to Norway, Sadownik (2018) reported that the children’s cultural capital was devalued during the migration, and thereby their sense of belonging was limited since they lacked necessary cultural competences to participate in peer communities.

Purpose

The purpose of the survey was to investigate how the parents assess the fulfilment of the inclusion goals that apply to the Swedish pre-school activities. In addition to this, learn about the parents’ perspectives on factors and pedagogical approaches that promote diversity and belonging.

Definitions of Key Concepts for the Study

The definitions formulated for the study were as follows. “Belonging refers to processes of inclusion and exclusion among children and educators in their everyday pre-school practice. Belonging relates to diversity in a broad sense. Participation can be an expression of belonging, a place, activities, and procedures. It can vary according to the degree of involvement experienced by educators and children. The term inclusion refers to interactions within the pre-school community. Inclusion refers to forming groups and joint activities within the community at the interactional level.”

Materials and Methods

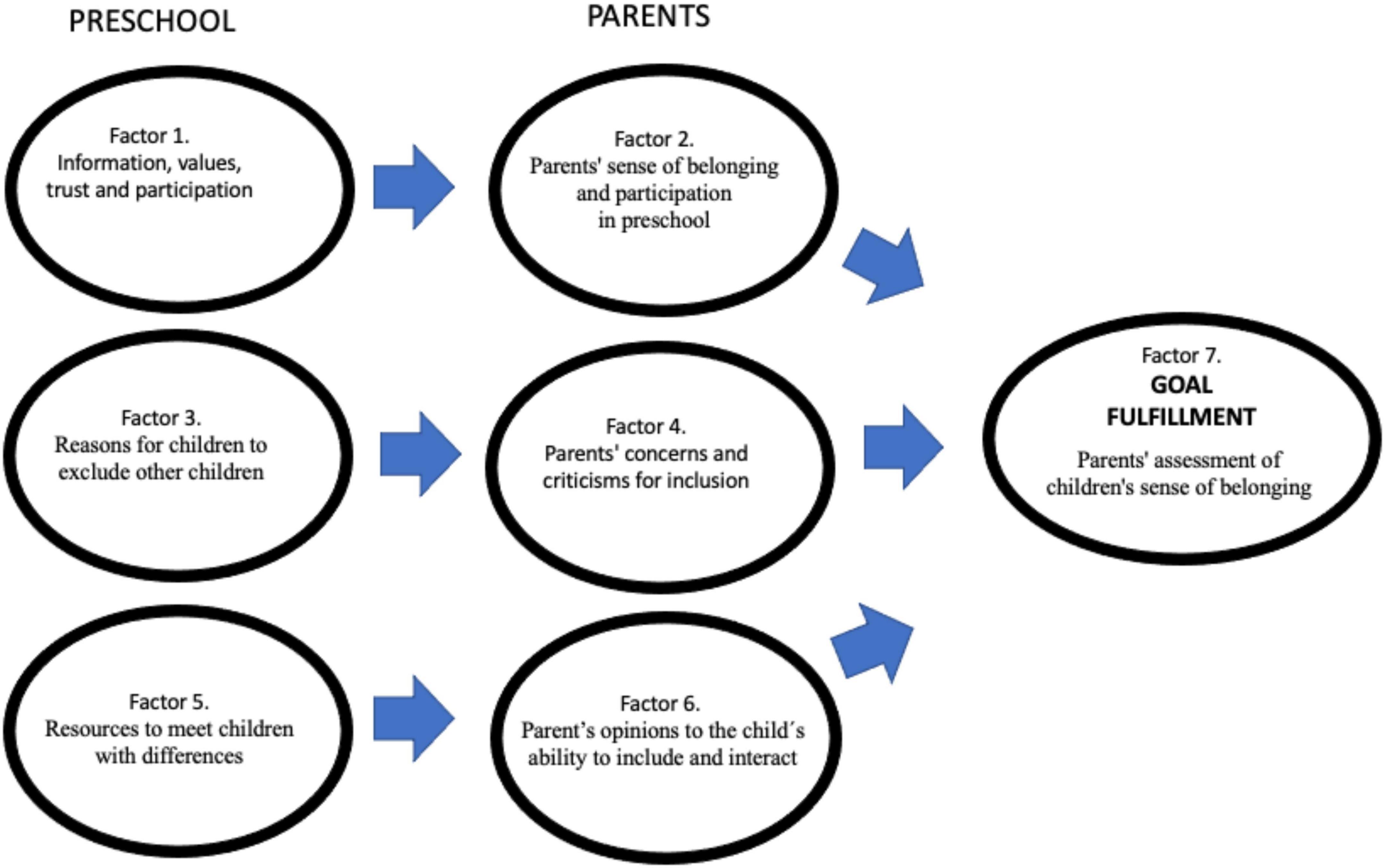

The study, carried out in the spring of 2019, is based on previous research on factors and pedagogical approaches that were judged to promote diversity and a feeling of belonging. As a first step, literature on parents’ perspectives was studied and referenced. Figure 1 presents the model that served as a starting point for question construction and the reporting of results. The questions addressed to the parents were formed into seven factors with a relatively high correlation.

Instruments

The survey questions were constructed in 2019 in collaboration with pre-school re-searchers from Finland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. The questions were based on the pre-school programmes of the different countries and, after discussions, were formulated jointly in English. The items were then translated into the languages of each participating country.

After a pilot study in each country, minor linguistic adjustments were made to suit the individual national contexts. The questionnaire was translated into English again (back-translation). This measure was taken to check that translation issues were still consistent among the countries.

The survey contained 72 questions. Of these, 46 were multiple-choice questions, 22 were ranked alternatives, and four were open-ended. The multiple-choice questions were constructed as statements where the respondent would disagree or agree. Words in the multiple-choice questions were in their construction both positive (Gerrbo, 2012) and negative (Glenn-Applegate et al., 2011) to enable a check of the study’s reliability.

After the questions were constructed, a factor analysis revealed seven question areas/factors with relatively high internal correlations. Factor analysis attempts to bring inter-correlated variables together under more general, underlying variables. More specifically, factor analysis aims to reduce the original space’s dimensionality and provide an interpretation of the new space, spanned by a reduced number of new dimensions that are supposed to underlie the old ones. Factor analysis offers the possibility of gaining a clear view of the data. Cronbach’s alpha measures internal consistency: how closely related a set of items are as a group. It is a measure of scale reliability. As the average inter-item correlation increases, Cronbach’s alpha increases as well. The general rule of thumb is that a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 and above is good. Six factors reached this threshold, while one aspect was close (Rietveld and Hout, 2005). The factors and their weights are presented in Table 1.

Context and Participants

The survey was chosen because of the desire to reach different types of pre-schools in geographically dispersed regions. It was also crucial that the pre-schools represented other socio-economic areas. When the survey was designed jointly between five countries, there was also ambitious to compare these countries. The results of that comparison will be reported in a future article. It was considered necessary that the participating countries report the national situation separately. In Sweden, no similar quantitative study has been conducted, strengthening the motive for a national report.

The data was carried out using a web survey distributed via the parents’/guardians’ e-mail addresses. The aim was to cover an area where pre-schools varied geographically and socio-demographically. The Swedish data collection was conducted in two regions with six municipalities participating. The surveys were distributed among large cities, smaller communities, and rural areas to guarantee the demographic spread.

After contacting and receiving approval from the education administrators of the participating municipalities, emails were sent to the principals who chose to offer their parents’/guardians’ participation in the investigation. The principals then forwarded information about the study and the link to the online survey to the parents’/guardians’ email addresses. In one municipality, the responsible researcher sent the study information and questionnaires directly to the parents from e-mail lists received from the central administration.

The Swedish part of the project had been approved by the national ethics review authority, with particular attention to required openness, self-determination for participants, confidential treatment of the research material and autonomy regarding the use of the research material (Hermerén, 2011). Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary, and the answers were anonymous and untraceable to any municipality or specific pre-school. The intention was to distribute 3,000 questionnaires for forwarding to parents, but only 2,006 questionnaires reached their recipients, which gives a response rate of 23%. After 2 weeks, a reminder was sent out to all prospective participants, and the opportunity to respond expired after 4 weeks.

Response Rate

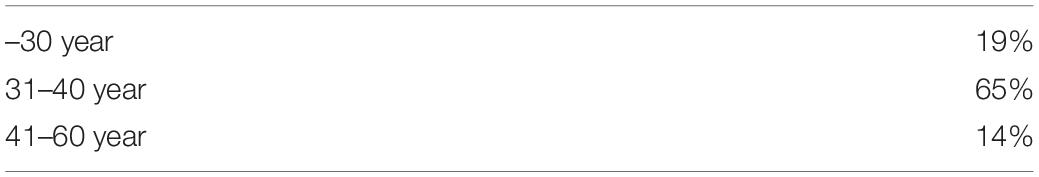

There were 454 respondents (23%). Of those who answered, 71% were women, 26% were men, and 3% did not state a gender. The majority (79%) of those who responded were between 31 and 60 years old (Table 2).

Of the respondents, 85% were born in Sweden, and 15% were born abroad, representing 32 countries. Of those born abroad, 10% stated that they had come to Sweden in the last 5 years. Of the total born abroad, 15% stated that they used a second language at home. Of all the respondents, 91% stated that they had a job, while 7% did not. The parents who worked full-time made up 76% of the respondents, with 16% working part-time. The parents’ education responses are shown in the distribution in Table 3.

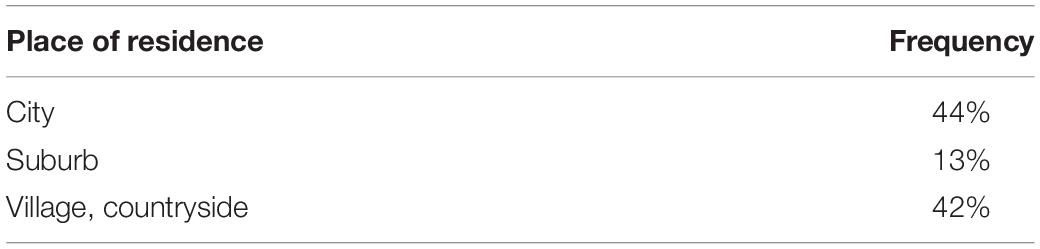

A total of 371 of the respondents stated their occupations. Of these, 47% worked in healthcare and education. The occupations with the greatest representation in the survey were teachers with 12%, followed by nurses and assistant nurses with 10%. The respondents’ places of residence are categorized in Table 4.

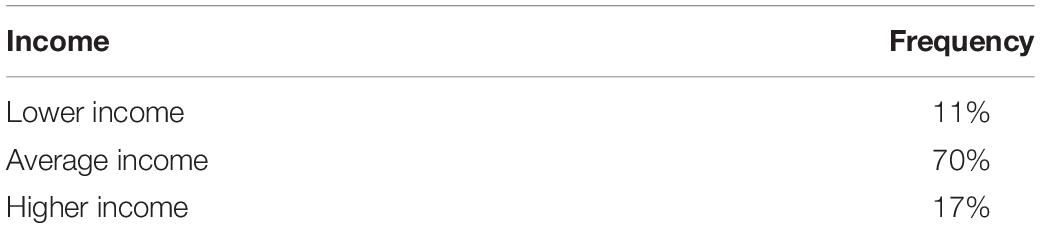

The respondents were asked to estimate their income in relation to the average income in Sweden; their answers are shown in Table 5.

Dropout

It is impossible to present an accurate dropout analysis, as non-responses to the survey cannot be tracked to individual municipalities, pre-schools, or parents. An important part of the dropout is probably the principals have not distributed the survey to the parents. Other reasons for the low response rate are the uncertainty surrounding the new data law (GDPR) recently introduced in the EU. The scope of the survey and the formulation and composition of the questions also do not support a high response rate. There is probably an over-representation of parents in the dropout group who are neutral, negative, or uninterested in inclusion issues compared to those who responded to the survey.

Each questionnaire encloses information about the respondent’s age, education, gender, employment, income, country of birth and home language. Therefore, the obtained responses should be valuable data for discussions about essential factors in creating and maintaining an inclusive environment despite the dropout. The results do not report the internal dropout, as it was shallow; no question had a greater dropout rate than a dozen individuals.

Results

Factors With Response Rates to Multiple-Choice Questions

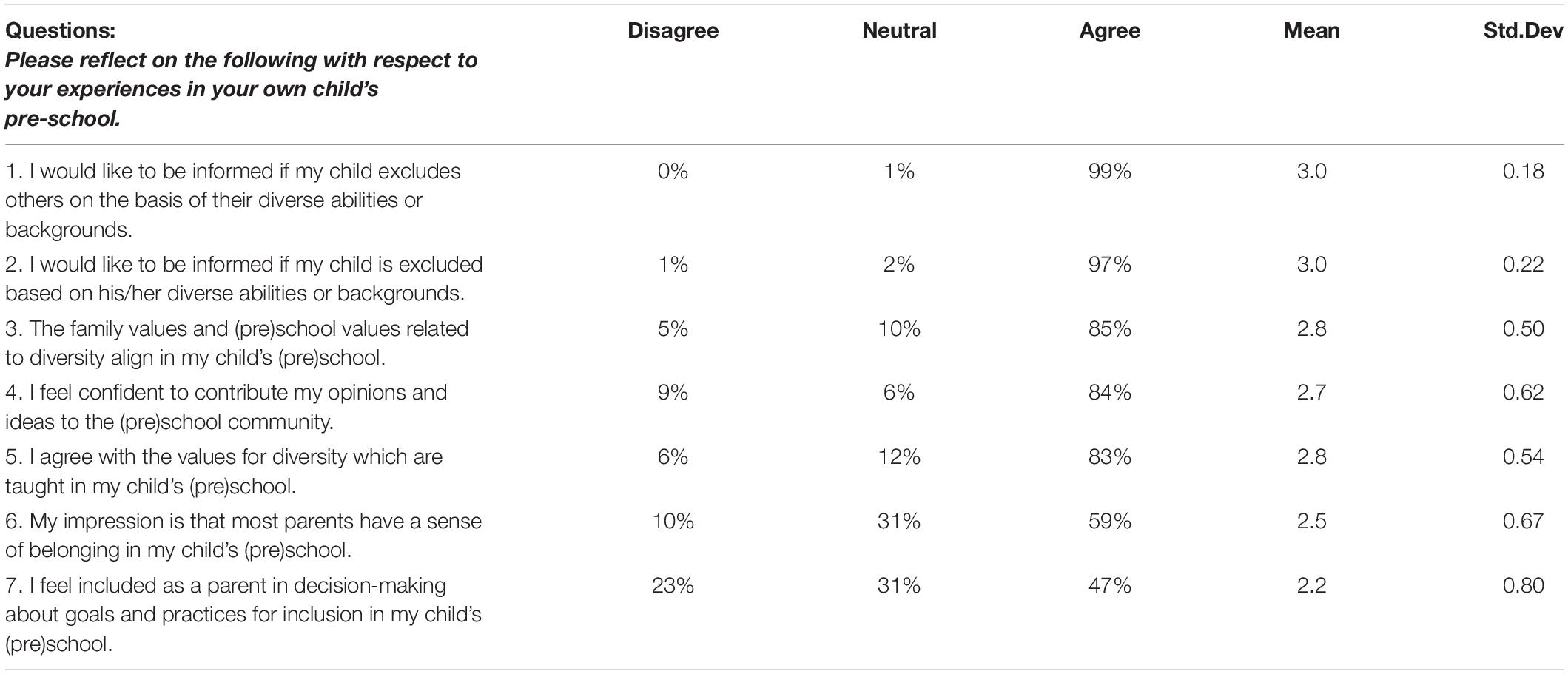

Almost all the parents wanted to be informed if the child was excluded (99%) or exposed other children (97%) to exclusionary acts. The parents felt comfortable with the values (85%), opinions and ideas (84%) that the pre-school conveyed and taught the children (83%). More than half of the respondents (59%) believed that other parents had a sense of belonging to the pre-school. Nearly half (47%) of the respondents felt involved in the decisions related to the issue of belonging (Table 6).

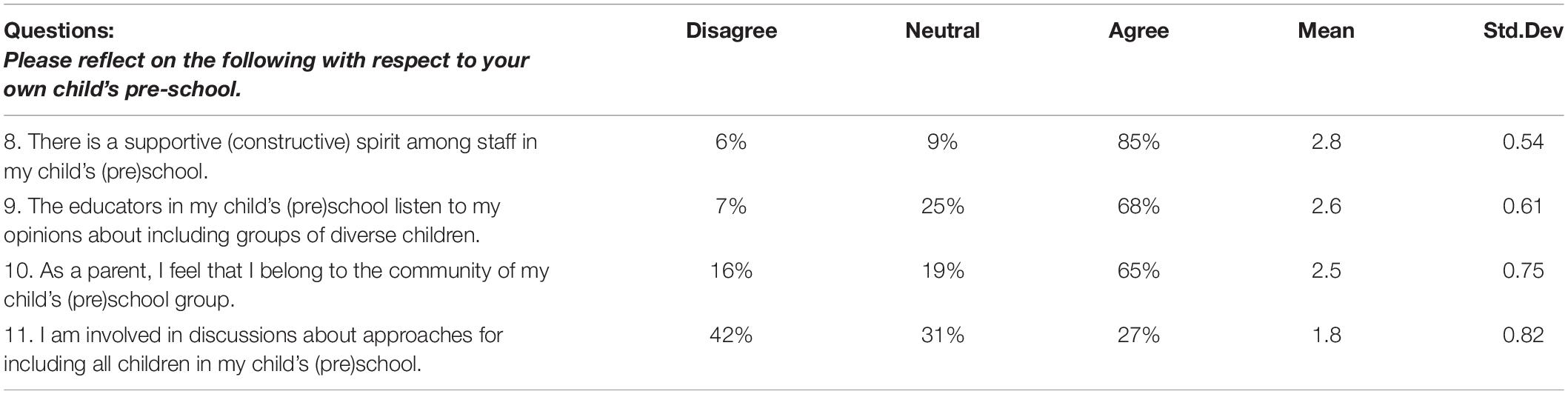

More than two thirds (85%) of the parents believed that there was a supportive attitude among the staff at the child’s pre-school. Clearly, more than half (68%) of the parents believed that the staff listened to their opinions when it came to issues of inclusion. Nearly the same number (65%) felt that they belonged to a community at their child’s pre-school. Regarding participation in discussions on inclusion issues, almost half of the respondents (42%) believed that they did not participate (Table 7).

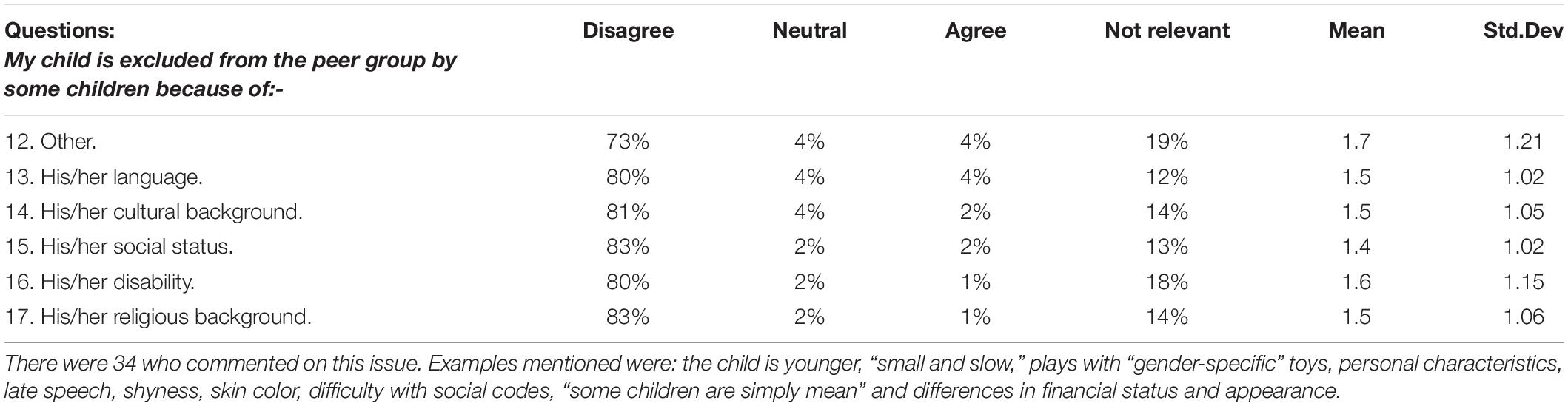

A little more than a tenth of the parents (14%) stated specific reasons why their children were excluded from the group of children. Language (4%) and other causes (4%) not listed in the question shown in the table were the most common (Table 8).

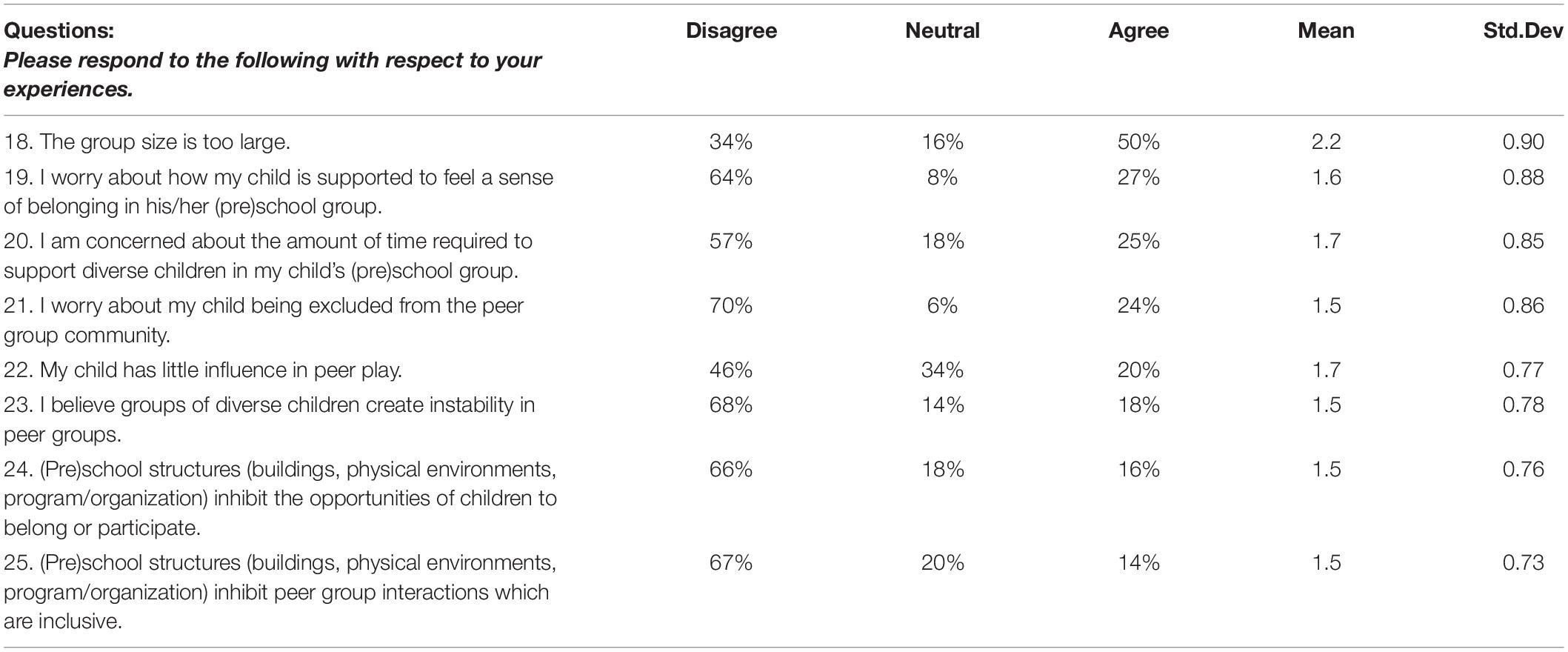

Half (50%) of the parents who responded to the survey believed that the group of children where their children were included was too large. One third (34%) of parents did not share this view. Around a quarter of the parents (27, 25, and 24%) were worried that their children would not receive the support they needed. However, many parents had clear confidence in the staff’s ability to make their children feel a sense of belonging. More than half (64 and 70%) said they did not worry about this. Just under one-fifth (18%) believed that various children created instability in peer groups. Few parents (16 and 14%) were critical of pre-school structures, such as buildings, physical environments, and programs/organizations (Table 9).

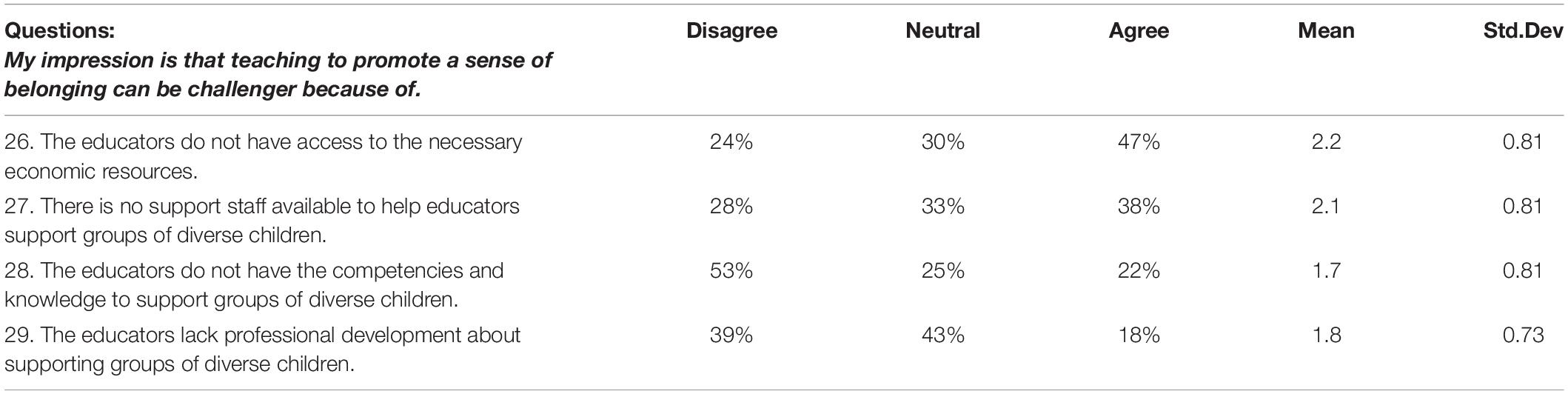

Nearly half of the parents (47%) believed that the staff did not have access to the financial resources required to support an inclusive approach. This was reflected in the lack of extra staff (38%) and, to some extent, the lack of training (22%) and further training (18%) (Table 10).

When parents assessed their children’s ability to communicate in an inclusive spirit, two-thirds answered (77%) that they were competent at this. At the same time, almost half (45%) were behind the claim that their children can help develop an environment that includes other children. However, roughly as many (47%) said that their children were too young to stand up on their own and other children’s rights to feel a sense of belonging in pre-school. At the same time, a third of parents believed that their children were too young (31%) or had difficulty understanding (30%) how this should be done, and slightly fewer parents (24%) believed that their children needed support from educators in this process (Table 11).

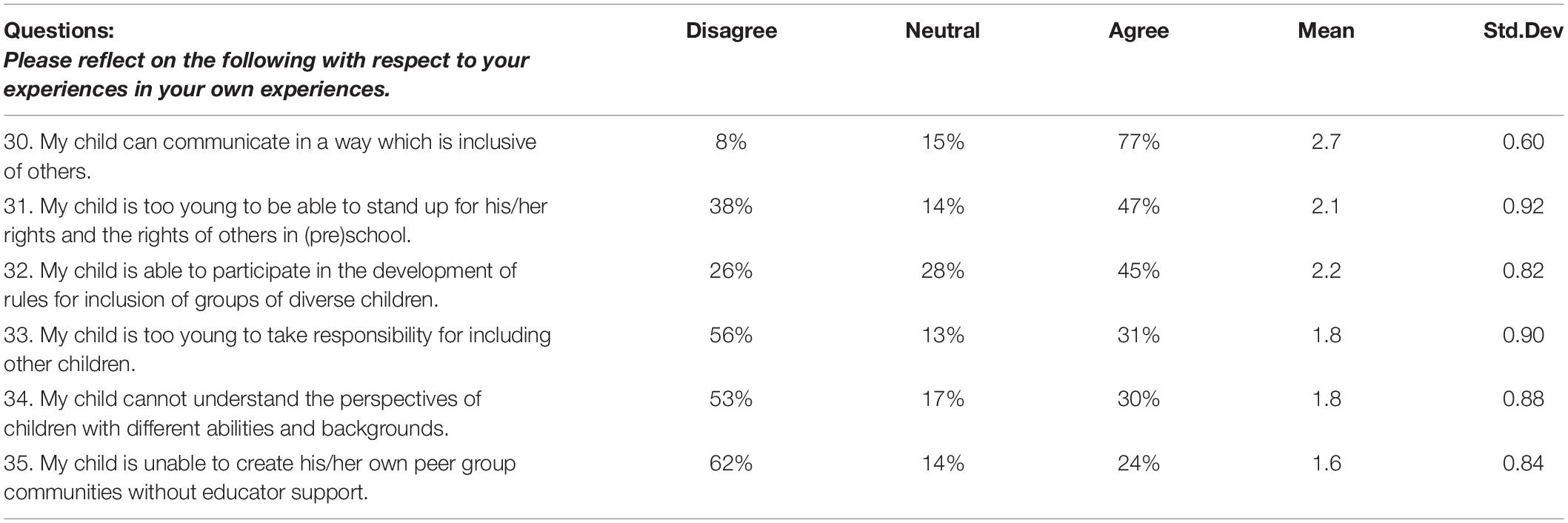

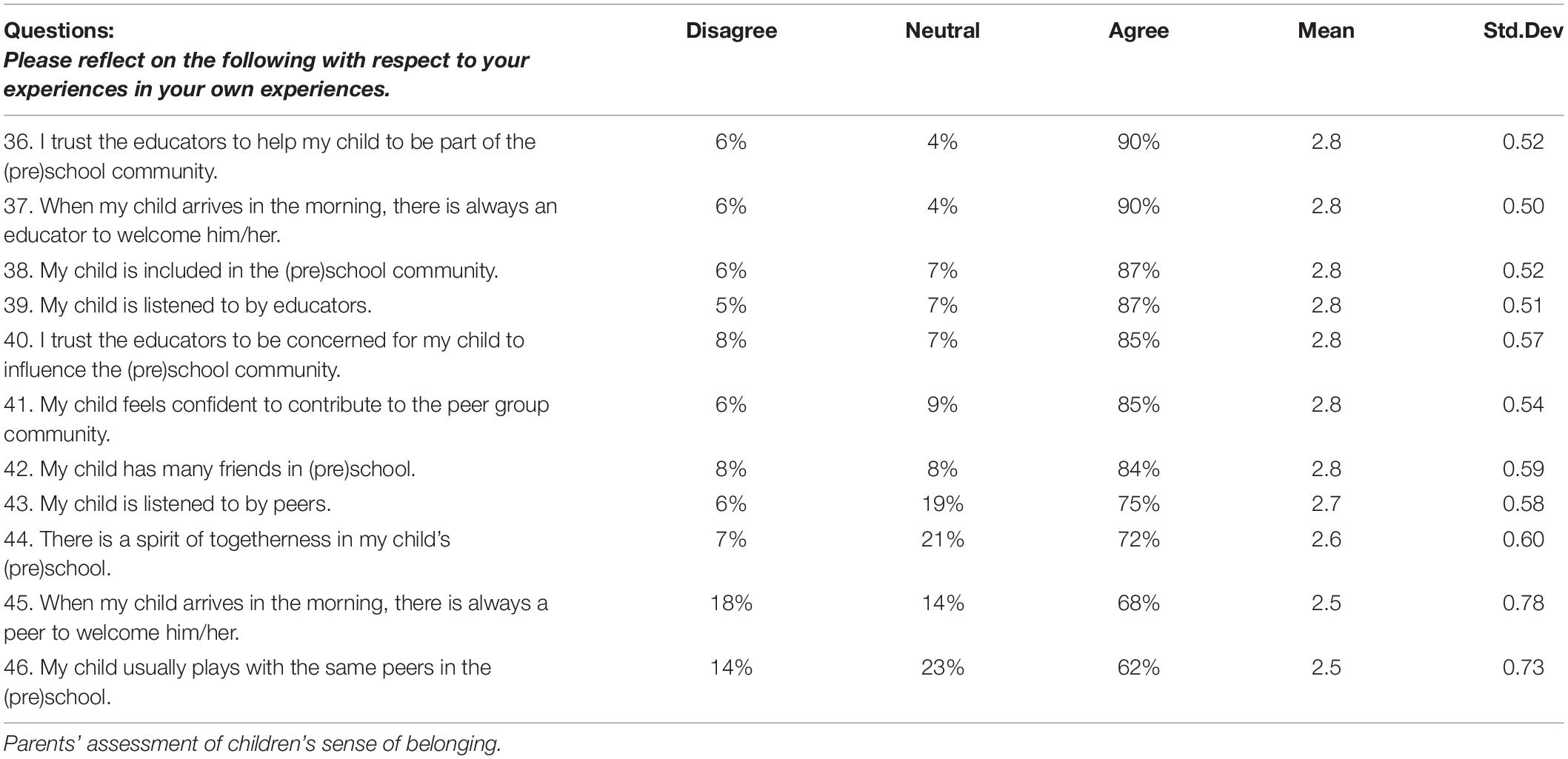

A clear majority of parents (90%) trusted the staff to help their children become part of the community. The same proportion (90%) stated that their child was always welcomed by a staff member in the morning. A clear majority of parents (87%) stated that their children were included in the pre-school group and that the staff was sensitive (87%) to what the children had to say. Roughly the same proportion trusted the staff’s ability to include the child and make them safe in the child’s group (85%). Most parents (84%) believed that their children had many friends at pre-school and that there was a sense of belonging at pre-school (72%) (Table 12).

Answers to Ranking Options

When the parents ranked the expectations for the activity, the top responses were that they wanted the children to be accepted as they were (Rank 1), that all the children would be included as part of the peer group (Rank 2) and have a mutual friendship (Rank 3) with at least one child. That children develop an understanding of differences by discussing their own and other children’s feelings were prioritized by parents (Ranks 1 and 2, respectively). Incorporating many perspectives about diversity and learning special facts it was also ranked highly by the parents (Ranks 3 and 4, respectively).

Results From the Open Questions

The answers to the two open questions were mainly short and precise. A few answers were more detailed, and most of the respondents were positive regarding inclusion. On the question “If you could make changes to promote belonging for children in (pre)school what would it be?” 146 parents responded (32%). In 55 of the responses, more resources were requested. Comments about having fewer children in the group and more teachers were common. There were 36 answers that gave concrete proposals for inclusive measures. In 15 answers, extended staff training was proposed. It was difficult to find negative statements about inclusion. The question “What else would you like to tell us about belonging in your child’s (pre)school?” received 109 answers. In 27 of the answers, the importance of belonging to the group was emphasized, that all the children needed to feel a sense of belonging in the group and the right to be themselves. In 25 responses, the importance of the staff’s competence was emphasized, and the responsibility for inclusion rested primarily on the staff’s commitment and ability. The need for more resources was reiterated in 28 comments. In other questions, it was briefly commented that there was nothing to add.

Correlations

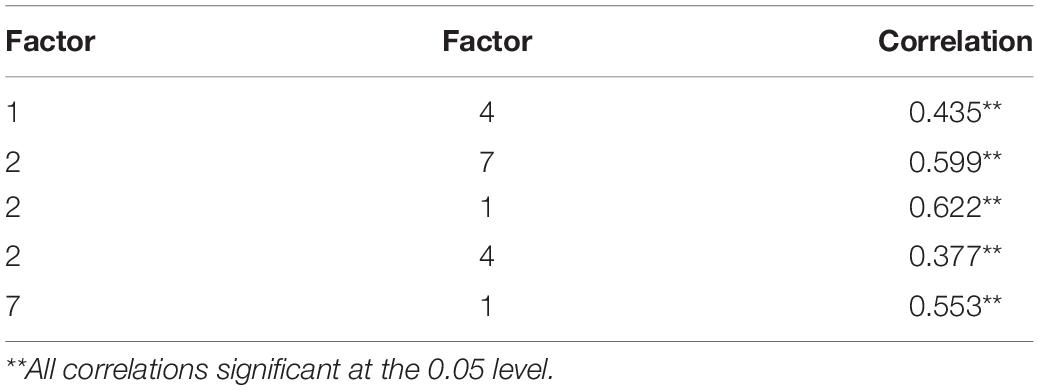

To investigate whether there were any connections between the factors, a correlation analysis was performed. Such an analysis aims to investigate whether there is a relationship between two variables where the direction and strength of the relationship varies between the values −1 and + 1. The Pearson correlation coefficient is the most widely used measure. It calculates the strength of the linear relationship between two normally distributed variables. Values such as 0.21–0.4 can be considered as a weak relationship and values between 0.41 and 0.6 as a medium strength relationship (Borg and Westerlund, 2020).

There were several positive relationships between the factors, with all correlations significant at the 0.05 level marked by “**” (Table 13).

The first correlation listed is between Factors 1 and 4. When the parents did not share the values of the pre-school and had a weak commitment to the activity (Factor 1), the criticism and concern for an inclusive attitude decreased (Factor 4).

The second correlation reported in the table above is Factor 2 positively correlating with Factor 7. This indicates that parents who experienced an open atmosphere at pre-school and when the parents were listened to and could participate in discussions about inclusion (Factor 2), they experienced a higher goal fulfilment when it came to their children’s sense of belonging (Factor 7).

The third correlation, in which Factor 2 correlated with Factor 1, had a slightly stronger connection than the first and showed that parents who experienced an open atmosphere at the pre-school and when the parents were listened to and could participate in discussions about inclusion (factor 2) had a clear positive connection with the parents sharing values with the activity and feeling that they could participate in the activity (Factor 1).

The fourth correlation, which was somewhat weak, was between Factors 2 and 4. This indicates that if the parents had a weak sense of belonging to the pre-school (Factor 2), they were also worried and critical of inclusive activity (Factor 4).

The fifth correlation was between Factors 7 and 1. The parents who experienced a higher goal fulfilment in terms of their children’s sense of belonging (Factor 7) also shared values with the activity and felt that they could participate in the activity (Factor 1).

Differences Between Background Conditions

The answers were compared based on the background variables age, education, gender, employment, housing location, income, country of birth and home language. Parents who were 36 years or older felt more belonging in the pre-school than parents in younger ages (Factor 2). At the same time, they were more critical of the resource allocation than the younger parents (Factor 5). The younger parent group indicated to a lesser extent that their children were excluded (Factor 3) and placed higher trust in their children’s ability to include and interact (Factor 6) with other children.

Parents with compulsory school or upper secondary education assessed pre-school resources more positively than university graduates (Factor 5). This group also saw fewer motives for excluding children (Factor 3) from other children. Parents who worked part-time felt a greater sense of belonging to the pre-school’s activities than full-time working parents. Parents whose children were in suburban areas assessed that their children had a sense of belonging to a greater degree than parents from villages, rural areas, and cities (Factor 7). The same group of parents assessed the pre-school’s resources as inferior when compared to parents from villages, rural areas, and cities (Factor 5), and also that the children’s ability to act inclusively was higher (Factor 6). Parents from urban and rural areas were more concerned and had more criticism toward inclusion (Factor 4) than parents living in the suburbs. Foreign-born parents assessed that their children had a sense of belonging to a lesser degree than when non-foreign-born parents made the same assessment for their children (Factor 7). Foreign-born parents rated the resource availability at pre-schools as higher than non-foreign-born parents (Factor 5). Foreign-born parents assessed that their children had a better ability to act inclusively than children whose parents were not born abroad (Factor 6). Non-foreign-born parents had more concerns and criticisms of inclusion (Factor 4) than foreign-born parents. Foreign-born parents who spoke a language other than Swedish at home felt less belonging to the pre-school (Factor 2). The same group assessed that their children felt less belonging in comparison with foreign-born parents who spoke Swedish at home (Factor 7). Foreign-born parents who spoke Swedish at home believed that the resources at pre-school were better than the group of parents who spoke their home language at home (Factor 5). Foreign-born parents who spoke Swedish at home assessed to a greater extent that their children had a better ability to act inclusively than children whose parents were born abroad and spoke another language at home (Factor 6). Foreign-born parents who spoke Swedish at home to a greater extent shared values with the pre-school’s activities and felt that they could participate in the activity to a greater extent than foreign-born parents who spoke another language at home (Factor 1). Foreign-born parents who spoke another language at home were not as worried or critical of inclusion as foreign-born parents who spoke Swedish at home (Factor 4).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study wants to contribute to more knowledge about how belonging is realized in ECE, which Johansson (2017) calls for. The study shows that the goal fulfilment for an inclusive pre-school is relatively good. The respondents share the idea of an inclusive pre-school but are not entirely certain that other parents have the same attitude. Here, discussions at parent meetings can make the consensus that prevails visible. The results of the study show that the parents have confidence in the staff at the pre-school, and a majority considered that their children felt a sense of belonging.

Despite this, it is not possible to ignore that parents believed that their children experienced exclusion. Between six and eight percent stated this in the questions that measured goal fulfilment. About the same proportion of parents was neutral in their answers. If half of these neutral answers can be interpreted as uncertainty, then about ten percent of the respondents show concern about whether their children were part of the pre-school community. When asked directly if other children in the group excluded their children, 14% stated affirmatively. This can be seen as an important warning signal to pre-school staff.

Regarding the parents’ perspectives on factors and pedagogical approaches that promote diversity and belonging language is the main reason for exclusion, but several other reasons are mentioned. This means that there is an important reason to actively work with measures to ensure that all children feel a sense of belonging in pre-school.

Informing the parents concerned whether their child excludes another child, or if any child is outside the group, is essential for parents.

More than half of the parents do not clearly indicate that they feel involved in the pre-school’s decisions regarding participation for all children. Here, parental involvement and influx must increase. One suggestion is that parents participate when the pre-school carries out their term planning. Most of the parents in the survey believed that it was important that children are accepted as they are and that all children are included in the group. Discussing differences with children based on their own experiences and thoughts is something that parents prioritize, and that can lead to higher goal fulfilment. The parents placed great trust in group activities but were also concerned that the children’s individual needs were met. This is something that agrees well with Eek-Karlsson and Emilson’s (2021) study. Deeper contact with a friend is highly valued. It can therefore be an idea to encourage stable individual contacts while being aware that no one stays out of the peer group. It is a pedagogical challenge to maintain an activity that can balance these two different orientations. A model that includes individualization (Karlsudd, 2015) and aims to support this work can be a way to deal with a challenge that is often described by staff as a dilemma.

Parents mainly have great faith in other children’s abilities to be role models and in a group upbringing where other children are important actors. At the same time, the respondents realized that the staff is of great importance in creating the conditions for the feeling of belonging (Boyle et al., 2011).

That the size of the group of children, staff density and staff training are important factors is something that the parents clearly noticed. This has been emphasized in several research reports (Avramidis and Kalyva, 2007) and there is every reason to work for improvements in these respects.

The connection between the children being judged to have a sense of belonging and the parents being well-informed, involved, and safe in activities and goals is very clear. Previous studies have also shown this (Bulotsky-Shearer et al., 2012; Morrone and Matsuyama, 2020). One way to approach having more children included in the group is to get the parents more involved and familiar with activities and for the staff to clearly convey the goals that apply to the activities. The results clearly show that the group of parents who met these criteria did not experience to the same extent that their children were outside the group of children. Children of parents who were outside the pre-school community were judged to find it easier to feel exclusion, as previous research has also shown.

It seemed easier to get into activities if the parent worked part-time. One explanation for this was certainly that there was more time, energy, and opportunities to participate in the activity at different times of the day. There were also differences based on the ages of the parents. The older parents felt more involved in the activity than the younger ones. It may therefore be appropriate to find forms of cooperation that make younger parents feel more involved, perhaps in a stronger collaboration with slightly older parents. In this type of collaboration, staff awareness of the problems is likely to increase (Boldermo, 2020).

Parents from the suburbs rated the achievement of goals higher than parents living in cities, villages, and rural areas. At the same time, the suburban parents assessed the pre-school’s total resources as weaker than the other categories but did not show the same degree of concern and criticism of inclusion as the others. This group also placed higher trust in the children’s ability to interact in an inclusive direction. The reason for this may be that the suburban environment was more heterogeneous, and parents, children and staff were used to meeting and dealing with differences and experiences of inclusion and exclusion processes which has a greater representation (Tillet and Wong, 2018; Juutinen and Kess, 2019). It is likely that suburban pre-schools can impart a lot of knowledge and experience on how to increase the understanding of diversity.

Foreign-born parents assessed that their children had worse goal fulfilment in terms of inclusion than children of parents born in Sweden. The foreign-born parents who spoke a language other than Swedish at home found it even more difficult to enter the pre-school culture which is also confirmed in previous studies (Sadownik, 2018; Johansson and Rosell, 2021). Speaking a language other than Swedish at home was not the direct cause of poorer goal fulfilment, but there was probably in this group an over-representation of new arrivals who had not had time to adapt to the new situation. To make this group feel involved and comfortable with the pre-school’s goals and culture, new and creative ways must be found (Nielsen and Christoffersen, 2009). The key to greater participation for this group is to improve their Swedish language skills. Perhaps more adapted parenting activities within the framework of pre-school work can make a difference. Hopefully, the results of this study can provide some guidance in this direction.

Method Criticism

This study’s response rate was relatively low, which probably has many causes. The ambition to answer as many questions as possible made the survey comprehensive. Even though most questions were multiple-choice (94%), many respondents felt it was too time-consuming. Another problem was that formulations and concepts well-known in the academic world could be perceived by pre-school parents as strange and difficult to interpret. This applies especially to parents who have recently come to Sweden. “RTM is a ubiquitous phenomenon in repeated data and should always be considered as a possible cause of an observed change. Its effect can be alleviated through better study design and use of suitable statistical methods” Barnett et al. (2015, p. 1). In this study design, no space was given to control the RTM effect. Therefore, it is essential to be aware of the problem and interpret and treat the mean values judiciously.

Forthcoming Study

The present study has generated interesting findings and valuable methodological experience, crucial in further research. Therefore, to move forward in a more development-oriented study where the value-based discussions reach all parents is a logical continuation. The next step is to try methods in projects that include children, staff, and parents, where all actors have been judged to be necessary for goal fulfilment. New surveys based on qualitative interviews can provide knowledge to safeguard, develop, and strengthen methods for increased participation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board Statement. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee “Regionala Etikprövningsnämnden (Regional Ethics Review Board) Linköping, Sweden” Dnr 2018/208-31 2018-05-15. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abreu-Lima, I. P., Leal, T. B., Cadima, J., and Gamelas, A. (2013). Predicting child outcomes from preschool quality in Portugal. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28, 399–420. doi: 10.1007/s10212-012-0120-y

Ali, M., Mustapha, R., and Jelas, Z. (2006). An empirical study on teachers’ perceptions towards inclusive education in Malaysia. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 21, 36–44.

Asp-Onsjö, L. (2010). “Specialpedagogik i en Skola för Alla (Special education in a school for all),” in Lärande, Skola, Bildning, eds U. Lundgren, R. Säljö, and C. C. Liberg (Stockholm: Natur and Kultur).

Avramidis, E., and Kalyva, E. (2007). The influence of teaching experience and professional development on Greek teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 22, 367–389. doi: 10.1080/08856250701649989

Barnett, A., Van Der Pols, J., and Dobson, A. (2015). Correction to: Regression to the mean: What it is and how to deal with it. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44:1748. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv161

Boldermo, S. (2020). Fleeting moments: young children’s negotiations of belonging and togetherness. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 28, 136–150. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2020.1765089

Borg, E., and Westerlund, J. (2020). Statistik för Beteendevetare: Faktabok, 4th Edn. Indianapolis, IND: Liber.

Boyle, C., Topping, K., Jindal-Snape, D., and Norwich, B. (2011). The importance of peer-support for teaching staff when including children with special educational needs. Sch. Psychol. Int. 33, 167–184. doi: 10.1177/0143034311415783

Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., Wen, X., Faria, A., Hahs-Vaughn, D. L., and Korfmacher, J. (2012). National profiles of classroom quality and family involvement: a multilevel examination of proximal influences on Head Start children’s school readiness. Early Child. Res. Q. 27, 627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.02.001

Bundgaard, H., and Gulløv, E. (2008). Forskel og faellesskab: Minoritetsbørn i daginstitution. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Chuckle, P., and Wilson, J. (2002). Social relationships and friendships among young people with Down’s syndrome in secondary schools. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 29, 66–71. doi: 10.1111/1467-8527.00242

Crosnoe, R., March, J. A., and Huston, A. C. (2012). Children’s early child care and their mothers’ later involvement with schools. Child Dev. 83, 758–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01726.x

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P., and Pence, A. (2014). Från kvalitet till Meningsskapande: Postmoderna Perspektiv - Exemplet Förskolan. Stockholm: Liber.

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 15, 331–353. doi: 10.1080/13603110903030089

Eek-Karlsson, L., and Emilson, A. (2021). Normalised diversity: educator’s beliefs about children’s belonging in Swedish early childhood education. Early Years [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2021.1951677

Einarsdottir, J., Purola, A.-M., Johansson, E., Broström, S., and Emilson, A. (2015). Democracy, caring and competence: values perspectives in ECEC Curricula in the Nordic Countries. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 23, 97–114. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2014.970521

Elliot, S. (2008). The effect of teachers’ attitude toward inclusion on the practice and success levels of children with and without disabilities in physical education. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 23, 48–55.

Emanuelsson, I. (1996). “Integrering—bevarad normal variation i olikheter,” in Boken om Integrering: Ide, Teori, Praktik, eds T. Rabe and A. Hill (Malmö: Corona).

Emilson, A., and Eek-Karlsson, L. (2021). Doing belonging in early childhood settings in Sweden. early child development and care. Early Child Dev. Care [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2021.1998021

Feng, Y., and Johnson, J. (2008). Integrated but not included: Exploring quiet disaffection in mainstream schools in China and India. Int. J. Sch. Disaffect. 6, 12–18. doi: 10.18546/IJSD.06.1.03

Frithiof, E. (2007). Mening, Makt och Utbildning: Delaktighetens Villkor för Personer Med Utvecklingsstörning. Växjö: Växjö University.

Gerrbo, I. (2012). Idén Om en Skola för Alla och Specialpedagogisk Organisering i Praktiken. Göteborg: Acta universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Giota, J., and Emanuelsson, I. (2011). Specialpedagogiskt Stöd, till vem och Hur? Rektorers Hantering av Policyfrågor kring stödet i Kommunala och Fristående Skolor. Gothenburg: Göteborgs universitet.

Glenn-Applegate, K., Pentimonti, J., and Justice, L. M. (2011). Parents’ selection factors when choosing preschool programs for their children with disabilities. Child Youth Care For. 40, 211–231. doi: 10.1007/s10566-010-9134-2

Hattie, J. A. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Milton Park: Routledge.

Holfve-Sabel, M. A. (2006). A comparison of student attitudes towards school, teachers and peers in Swedish comprehensive schools now and 35 years ago. Educ. Res. 48, 55–75. doi: 10.1080/00131880500498446

Jensen, B. A. (2009). Nordic approach to early childhood education (ECE) and socially en¬dangered children. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 17, 7–21. doi: 10.1080/13502930802688980

Jensen, N. R., Petersen, K. E., and Wind, A. K. (2012). Daginstitutionens Betydning for Udsatte børn og Deres Familier i Ghetto-Lignende Boligområder. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitet. doi: 10.7146/aul.18.16

Johansson, E. (2017). “Toddlers’ Relationships: A Matter of Sharing Worlds,” in Studying Babies and Toddlers: Relationships in Cultural Contexts, eds L. Li, G. Quinnes, and A. Ridgeway (Berlin: Springer), 13–28. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-3197-7_2

Johansson, E., and Einarsdottir, J. (2018). Values in Early Childhood Education: Citizenship for Tomorrow. Oxford: University of Oxford. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75559-5

Johansson, E., and Rosell, Y. (2021). Social sustainability through children’s expressions of belonging in peer communities. Sustainability 13:3839. doi: 10.3390/su13073839

Juutinen, J. (2018). Inside or outside? Small Stories about the Politics of Belonging in Preschools. Ph.D. thesis. Finland: University of Oulu.

Juutinen, J., and Kess, R. (2019). Educators’ narratives about belonging and diversity in northern Finland early childhood education. Educ. North 26, 37–50.

Juutinen, J., Puroila, A.-M., and Johansson, E. (2018). “There is no room for you! The politics of belonging in children’s play situations,” in Values Education in Early Childhood Settings: Concepts, Approaches and Practices, eds E. Johansson, A. Emilson, and A.-M. Puroila (Cham: Springer), 249–264. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75559-5_15

Karlsudd, P. (2012). School-age care, an ideological contradiction. Prob. Educ. 21st Cent. 48, 45–51. doi: 10.33225/pec/12.48.45

Karlsudd, P. (2017). The search for successful inclusion. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 28, 142–160. doi: 10.5463/dcid.v28i1.577

Karlsudd, P. (2020). Looking for special education in the Swedish after-school leisure program construction and testing of an analysis model. Educ. Sci. 10:359. doi: 10.3390/educsci10120359

Karlsudd, P. (2021). When differences are made into likenesses: The normative documentation and assessment culture of the preschool. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1879951

Lindberg, R. (2018). Att synliggöra det förväntade: förskolans dokumentation i en performativ kultur (Making Visible the Expected: Preschool Documentation in a Performative Culture. Växjö: Linnaeus University.

Lindroth, F. (2018). Pedagogisk Dokumentation—En Pseudoverksamhet? Lärares Arbete Med Dokumentation i Relation Till Barns Delaktighet. Växjö: Linnaeus University Press.

Lindsay, G. (2007). Educational psychology and the effectiveness of inclusive education/mainstreaming. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 77, 1–24. doi: 10.1348/000709906X156881

Linikko, J. (2009). ). Det Gäller att Hitta Nyckeln—Lärares Syn på Undervisning och Dilemma för Inkludering av Elever i Behov av Särskilt Stöd i Specialskolan. Ph.D. thesis. Sweden: Stockholms Universitet.

Mitchell, D. (2008). What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education. Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203029459

Morrone, M. H., and Matsuyama, Y. A. (2020). Hopeful and sustainable future: A model of caring and inclusion at a Swedish preschool. Child. Educ. 96, 64–68. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2020.1824516

Nielsen, A. A., and Christoffersen, M. N. (2009). Børnehavens betydning for børns udvikling. En forskningsoversigt. København: SFI Det Nationale.

Nilfyr, K. (2018). Dokumentationssyndromet: En interaktionistisk och socialkritisk studie av förskolans dokumentations-och bedömningspraktik. Växjö: Linnaeus University.

Nilholm, C. (2005). Specialpedagogik. Vilka är de grundläggande perspektiven? (Special education. What are the basic perspectives?). Pedagog. Sverige 2, 124–138.

Palla, L. (2011). Med blicken på barnet: om olikheter inom förskolan som diskursiv praktik. Malmö: Lunds universitet.

Persson, B., and Persson, E. (2012). Inkludering och Måluppfyllelse—Att Nå Framgång Med Alla Elever. Stockholm: Liber.

Pinto, A., Pessanha, M., and Aguiar, C. (2013). Effects of home environment and center-based child care quality on children’s language, communication, and literacy outcomes. Early Child. Res. Q. 28, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.07.001

Reite, G. N., and Haug, P. (2019). Conditions for academic learning for students receiving special education. Nord. Tidsskr. Pedagog. Krit. 5:281. doi: 10.23865/ntpk.v5.1640

Riddersporre, B., and Persson, S. (2017). Utbildningsvetenskap för förskolan. Stockholm: Natur and kultur.

Rietveld, T., and Hout, R. (2005). Statistics in language research: Analysis of variance. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9783110877809

Sadownik, A. (2018). Belonging and participation at stake. Polish migrant children about (mis)recognition of their needs in Norwegian ECECs. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 26, 956–971. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533711

Sari, H., Celiköz, N., and Secer, Z. (2009). An analysis of pre-school teachers’ and student-teachers’ attitudes to inclusion and their self-efficacy. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 24, 29–43.

Singhania, R. (2005). Autism spectrum disorders. Ind. J. Paediatr. 72, 343–351. doi: 10.1007/BF02724019

Stukat, K. G. (1995). Conductive education evaluated. Eur. J. Spéc. Needs Educ. 10, 154–161. doi: 10.1080/0885625950100206

Szönyi, K. (2005). Särskolans om Möjlighet Eller Begränsning-Elevperspektiv på Delaktighet och Utanförskap. Ph.D. thesis. Umeå: Umeå University Department of Education.

Tillet, V., and Wong, S. (2018). An Investigative Case Study into Early Childhood Educators’ Understanding about ‘Belonging. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 26, 37–49. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2018.1412016

Vickerman, P. (2012). Including children with special educational needs in physical education: Has entitlement and accessibility been realised? Disabil. Soc. 27, 249–262. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2011.644934

Vitalaki, E., Kourkoutas, E., and Hart, A. (2018). Building inclusion and resilience in students with and without SEN through the implementation of narrative speech, role play and creative writing in the mainstream classroom of primary education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 22, 1306–1319. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1427150

Keywords: pre-school (förskola), children, belonging, exclusion, inclusion, parents, perspective

Citation: Karlsudd P (2022) Swedish Parents’ Perspectives of Belonging in Early Years Education. Front. Educ. 7:930909. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.930909

Received: 28 April 2022; Accepted: 13 June 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Mats Granlund, Jönköping University, SwedenReviewed by:

Ole Henrik Hansen, Jönköping University, SwedenJosé Eugenio Rodríguez-Fernández, University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Karlsudd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter Karlsudd, cGV0ZXIua2FybHN1ZGRAbG51LnNl

Peter Karlsudd

Peter Karlsudd