- Department of Business and Economics Education, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

In recent decades, the acquisition of information has evolved substantially and fundamentally affects students’ use of information, so that the Internet has become one of the most important sources of information for learning. However, learning with freely accessible online resources also poses challenges, such as vast amounts of partially unstructured, untrustworthy, or biased information. To successfully learn by using the Internet, students therefore require specific skills for selecting, processing, and evaluating the online information, e.g., to distinguish trustworthy from distorted or biased information and for judging its relevance with regard to the topic and task at hand. Despite the central importance of these skills, their assessment in higher education is still an emerging field. In this paper, we present the newly defined theoretical-conceptual framework Critical Online Reasoning (COR). Based on this framework, a corresponding performance assessment, Critical Online Reasoning Assessment (CORA), was newly developed and underwent first steps of validation in accordance with the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. We first provide an overview of the previous validation results and then expand them by including further analyses of the validity aspects “internal test structure” and “relations with other variables”. To investigate the internal test structure, we conducted variance component analyses based on the generalizability theory with a sample of 125 students and investigated the relations with other variables by means of correlation analyses. The results show correlations with external criteria as expected and confirm that the CORA scores reflect the different test performances of the participants and are not significantly biased by modalities of the assessment. With these new analyses, this study substantially contributes to previous research by providing comprehensive evidence for the validity of this new performance assessment that validly assesses the complex multifaceted construct of critical online reasoning among university students and graduates. CORA results provide unique insights into the interplay between features of online information acquisition and processing, learning environments, and the cognitive and metacognitive requirements for critically reasoning from online information in university students and young professionals.

Introduction

The digital age has transformed learning in higher education as well as the learning materials accessible to students (Ali, 2020; Banerjee et al., 2020). The acquisition and use of information has evolved substantially in recent decades and also fundamentally affects students’ learning (Boh Podgornik et al., 2016; Brooks, 2016; Maurer et al., 2020). University students nowadays prefer the Internet to traditional textbooks for information acquisition; moreover, in the recently increasingly prevalent digital teaching and learning contexts, students use not professionally produced learning resources, found by eclectically browsing the web, more often and ubiquitously than the recommended OER. The Internet has therefore become one of the most important sources of information for learning; not only for the preparation of papers or presentations but also when studying for exams (Brooks, 2016; Newman and Beetham, 2017; Maurer et al., 2020). The World Wide Web provides a flexible learning resource while also accelerating the dissemination and processing of information and knowledge (Braasch et al., 2018; Weber et al., 2019; Maurer et al., 2020). However, learning with freely accessible online resources also presents challenges (Qiu et al., 2017; Ciampaglia, 2018). Since content can be freely distributed on the Internet, vast amounts of unstructured, untrustworthy, inaccurate, or biased information are just as readily available to learners as credible, verified information (Walton et al., 2020). Dealing with the vast amount of information available online, on a platform characterized by low publication barriers and deficiently established quality standards, requires students to be critically evaluative (Liu et al., 2014; Tribukait et al., 2017). Thus, the ever-changing information and learning environment has profound consequences for the imparting of knowledge in higher education (Harrison and Luckett, 2019; Weber et al., 2019; Maurer et al., 2020). To competently use and successfully learn from the information and resources openly accessible on the Internet, students must be able to critically search, select, review, and evaluate online information and sources based on relevant quality criteria (Sendurur, 2018; Molerov et al., 2020; Nagel et al., 2020). In the context of increasingly digital and self-directed teaching and learning processes in higher education, the successful use of digital media and competent, critical use of online information constitutes one of the most important student skills for successful study (Harrison and Luckett, 2019; Molerov et al., 2020), as has also been emphasized by the most recent research review (Osborne et al., 2022). This classifies it as a so-termed generic skill, which college graduates are expected to develop to operate successfully as professionals and responsible citizens of democratic societies (Binkley et al., 2012; National Research Council, 2012; Shavelson et al., 2018; Virtanen and Tynjälä, 2018; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021a). In addition to professional knowledge, such skills include quantitative reasoning, critical literacy and thinking, ethical and moral reasoning, and written and oral communication that college graduates can draw upon to address life’s everyday judgments, decisions, and challenges. As a current literature review indicates, nowadays, searching, evaluating, selecting, and using high-quality online information have additionally become generic skills important for successfully studying in higher education (Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021b).

So far, the related subskills have been assessed based on various theoretical constructs, such as “multiple-source use” (MSU; Braasch et al., 2018; Hahnel et al., 2019), “information trust” (Johnson et al., 2016; Leeder, 2019), and “web credibility” (Flanagin and Metzger, 2017; Herrero-Diz et al., 2019). While providing important insights into the individual subskills, these approaches have not yet systematically focused on the interplay between features of online information acquisition and learning environments and the (cognitive) requirements for critical reasoning from online information (Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018). Another relevant research strand focusses on the aspect of communicating the selected and critically evaluated information to answer an initial question, as such communication skills are particularly needed in later (professional) life (Chan et al., 2017; Braun, 2021). Lawyers or physicians, for example, not only have to compile various, reliable pieces of information on individual cases and draw conclusions from them, but also regularly exchange information with clients and patients in this process (e.g., Korn, 2004; Aspegren, and LØnberg-Madsen, P., 2005).

A recent review consolidating information problem-solving and multiple source use approaches highlights existing desiderata in examining how evaluated information is used in more advanced analytical reasoning processes and what role the characteristics of information play in reasoning (Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018). For instance, while students may differ in their judgment of the credibility of a source, drawing invalid inferences is generally wrong epistemically and indicates poor (online) reasoning skills. In addition, most of the tests used so far to measure these subskills have a close-ended format, thus covering only limited aspects of dealing with online information use and, in particular, failing to measure the actual reasoning process, and underlying procedural skills (Ku, 2009; Desai and Reimers, 2019). In addition, these procedures no longer do justice to the current efforts of higher education institutions regarding the measurement of students’ competencies, which increasingly focus on a holistic representation of students’ capabilities to act (Shavelson et al., 2019).

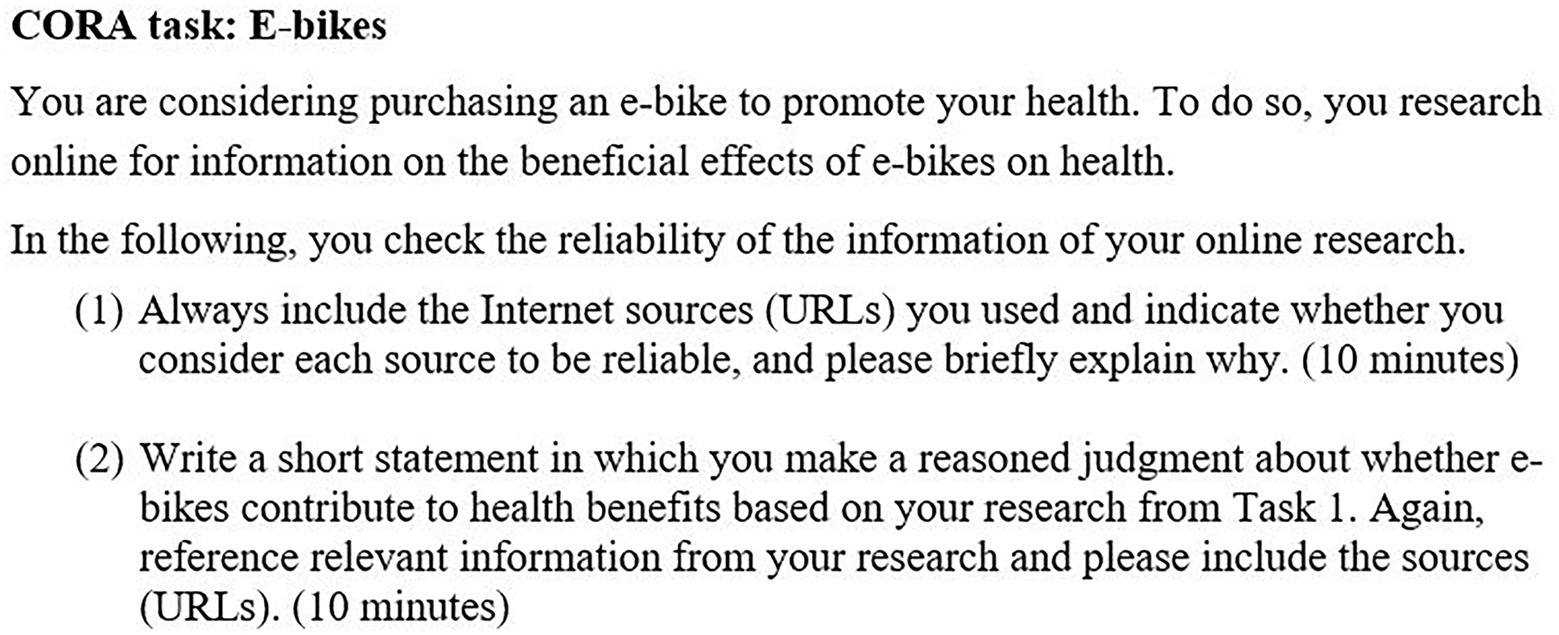

To make these crucial student skills pertaining to the online information environment empirically measurable and to be able to specifically promote them, a new theoretical-conceptual framework of Critical Online Reasoning (COR) was developed (see section “Conceptual background”; for details, see Molerov et al., 2020). COR describes the abilities of searching, selecting, accessing, processing, and critically reasoning from online information, e.g., to solve a particular generic or domain-specific problem or task (for details, see Molerov et al., 2020). This involves critically distinguishing trustworthy from untrustworthy information and making argumentative and coherent judgments based on credible and relevant information from the online environment. Based on this conceptual framework, a COR performance Assessment (CORA) was newly developed and underwent initial validation (Molerov et al., 2020; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021a). Based on the COR construct definition, CORA includes various authentic situational tasks in the online media environment, i.e., the real Internet, to objectively and validly assess students’ COR skills in a realistic performance assessment. This holistic assessment measures all required skill (sub-)dimensions and their interplay instead of only individual facets as would be the case, for example, with closed-ended tests (Davey et al., 2015; for a CORA task example, see Figure 1).

When measuring students’ COR skills through CORA, validity is one of the key quality criteria for the reliable interpretation of students’ test results. The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (hereafter referred to as “AERA Standards”) provide criteria for the reliable validation of educational tests (AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014). According to the AERA Standards, five aspects should be analyzed during validation and various sources of information should be used as evidence. The aspects to be analyzed are “test content,” “task-and test-response processes,” “internal structure of a test,” “interrelationships with other variables,” and “consequences of testing” (for details, see AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014). Therefore, the focus and central contribution of this paper is to present the comprehensive, multi-perspective and in-depth validation of the CORA as a novel performance-based test of generic student skills in higher education.

To validate the CORA tasks and interpret the test scores, initial validation steps have already been carried out:

1. Validity evidence regarding the CORA content was obtained through expert interviews and expert ratings of the CORA tasks (for details, see Molerov et al., 2020).

2. Validity evidence regarding the task response processes of the test takers was analyzed by Schmidt et al. (2020) on the basis of log files and eye-tracking data including gaze duration and fixations.

3. Initial validity evidence on the correlations with other variables was obtained by Nagel et al. (2020) through analyzing the extent to which participants’ web search behavior—specifically, the number and type of web pages accessed as well as the quality of the content on the web pages—is related to better task performance and thus to a more critically-reflective use of online information.

In this paper, further validation of the CORA tasks focusing on the two criteria ‘internal structure of the test’ and ‘correlations with other variables’ is presented and critically discussed. In this way, further validity aspects not yet considered are systematically and thoroughly investigated according to the AERA standards to obtain a comprehensive overview of the validity of the CORA. The results of the analyses are combined with the validity evidence outlined above to provide a comprehensive validity assessment of the new COR Assessment.

In Chapter 2, the definition of the COR construct, which serves as a basis for an appropriate interpretation of the CORA test results (Molerov et al., 2020), is explained in more detail. In addition, the COR Assessment framework is presented, including a sample task. Chapter 3 explains the validation approach of CORA, which is based on the model of argumentation-based validation of test score interpretations. According to the argumentation-based validation process (Mislevy et al., 2012), we briefly summarize the results of the previous validation studies on the content validity (section Content validity) and validity of task response processes (section Validity of task reponse processes) of CORA, before the newly obtained validity evidence is presented (sections Internal test structure and Relations with other variables) and integrated with the previous validation work for CORA. Chapter 4 provides a critical discussion of the results including the limitations of the work and an outlook on the further research.

Conceptual background

The COR construct definition

To harness the potential of the Internet for learning, students require a variety of information acquisition and processing skills, which have been previously summarized as such a broad literacy construct as digital literacy (Reddy et al., 2020; Park et al., 2021), which is also related to media literacy (Koltay, 2011), information literacy (Limberg et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2015; Walton et al., 2020), and computer literacies [e.g., information and communication technology (ICT) literacy, computer and information literacy (CIL); Siddiq et al., 2016; Makhmudov et al., 2020; see also, e.g., studies on multimedia learning, Mayer, 2009]. Particularly for students of higher education, current research presumes basic computer knowledge (Rammstedt, 2013; Schlebusch, 2018) as well as multimedia (Naumann et al., 2001; Goldhammer et al., 2013) and general Internet skills, which are required for self-directed online learning, a given (Rammstedt, 2013). However, numerous studies outline substantial deficits in students’ Internet-based learning in higher education that can hinder their study success. Based on prior research, we are going beyond such broad literacy and general ability concepts, and focus more specifically on modeling and validly assessing actual online information acquisition and processing skills, and in particular critical reasoning based on this online information. When modeling COR, we particularly draw on extended information problem-solving (IPS-I) models (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2019; Whitelock-Wainwright et al., 2020) to distinguish and describe the main processes involved in self-directed online learning. Thereby, we further expand these models by focusing on processes of argumentation as well as communication, which are not only important for students’ academic success but also key requirements that higher education graduates encounter on the labor market (Braun and Brachem, 2018). These skills can be summarized under the REAS-facet: Reasoning based on Evidence, Argumentation and Synthesis. Therefore, the COR model describes students’ key generic skills not only for searching, evaluating, and selecting—as in IPS-I models–but also additional processes including analyzing, synthesizing, and reasoning from (high-quality) online information, while self-directedly engaging with (more or less domain-specific) content or working toward course-related learning goals, e.g., outside of classrooms (e.g., preparing an essay at home). We differentiate between two main requirement areas for COR processes: generic and domain-specific, e.g., within particular study domains like Medicine or Law (for details, see Molerov et al., 2020). The focus of the analyses presented here is particularly on the generic COR skills required for researching more general topics that are not specifically related to a particular domain (for a differentiation between generic and domain-specific requirement areas for COR in higher education, see Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021a).

In our prior research, we theoretically analyzed the links and overlaps between the existing concepts and models for assessing students’ skills related to COR (for more details on these specific concepts, underlying constructs, and particularly overlaps and distinctions, see our differentiated descriptions in Molerov et al., 2020). Going beyond established abovementioned “literacy” concepts and constructs like digital literacy and multiple source use, we especially draw on the triad model of critical alertness, reflection, and analysis (Oser and Biedermann, 2020). Thereby, we particularly focus on how students analytically reason from as well as justify and critically reflect on online information they used for their higher education studies and infer from and weight arguments and (covert) perspectives of (partly conflicting) sources and information pieces. Based on this theoretical rationale, we specify a set of skills assumed crucial for the acquisition and use of high-quality online information for learning in higher education, which we term Critical Online Reasoning (for details, see Molerov et al., 2020). Thereby, in addition to the abovementioned models and concepts, we also particularly draw on the U.S.-established concept of civic online reasoning. This concept describes the ability to successfully deal with online information and distinguish, for instance, reliable and trustworthy sources of information from biased and manipulative ones (Wineburg et al., 2016). While this concept focuses especially on the handling of online information on political and social topics in particular, our approach of COR has been expanded to encompass all cross-domain topics relevant for students’ learning in higher education and beyond. In addition, we further substantially expanded the concept of civic online reasoning as well as the information problem-solving models by Brand-Gruwel et al. (2009), to cover the whole process of searching, evaluating, selecting, analyzing, synthesizing, and reasoning from online information. In doing so, we also specifically incorporated a new reasoning facet, described as Reasoning based on Evidence, Argumentation, and Synthesis (for details, see Molerov et al., 2020).

To sum up, the COR concept leans closely on previous process and phase models of (online) information search, selection, and evaluation, in particular the information problem-solving models (Brand-Gruwel et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2019; Whitelock-Wainwright et al., 2020). Thereby, we also consider insights from related “web credibility” research, especially on multiple-source use and multiple-source comprehension (Braasch et al., 2018; Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018; Hahnel et al., 2019). We expand the modeling of students’ information use in self-directed learning by adding a new critical reasoning component, i.e., Reasoning based on Evaluation, Argumentation, and Synthesis (REAS). In addition, we also integrate a metacognitive regulative component, i.e., Metacognitive Activation (MCA) skills, that helps students decide when to employ COR skills (e.g., to initiate a critical evaluation; for more details, see Molerov et al., 2020).

Based on this conceptual work, to model and measure COR according to international testing standards by AERA, APA, and NCME (2014) in an evidence-centered design (Zieky, 2014; Mislevy, 2017), we specified its construct definition with three overarching and overlapping cognitive facets:

1. online information acquisition skills (OIA), e.g., selecting search engines or databases, specifying search queries;

2. critical information evaluation (CIE) skills, e.g., evaluating website credibility based on cues; and

3. reasoning skills, e.g., using evidence to generate and justify a valid argument based on a synthesis of accessed information (REAS), including accounting for common errors and biases as well as considering (contradictory) arguments and (covert) perspectives from (possibly conflicting) sources and information.

In addition, metacognitive (MCA) skills regulate the state-specific and situation-specific activation, continuation, and conclusion of COR process within the encompassing information acquisition context, e.g., recognizing the need to use COR in learning-related contexts.

Based on this definition, we established COR as an operationalizable, multifaceted construct of students’ (meta)cognitive skills for goal-oriented and competent use of online information focusing on study-related contexts in higher education (for details, see Molerov et al., 2020).

The COR assessment framework

Methodologically, recent assessment research shows that tests with a closed-ended format are limited when it comes to validly measuring (meta)cognitive higher-order skills such as COR (e.g., Braun et al., 2020). In addition, they no longer do justice to the more recent efforts at universities to ensure the validity of testing procedures, which increasingly aim to holistically measure students’ capabilities to act (Shavelson et al., 2019). Closed-ended tests generally have a limited ecological validity as they fail to measure the procedural skills underlying the processing of (online) information used for learning, and, evidentially, students struggle to transfer the measured skills to more authentic, real-life situations (Ku, 2009; Davey et al., 2015; Desai and Reimers, 2019). It is thus evident that such complex, higher-order skill construct as COR can be more validly measured through performance assessments (Shavelson et al., 2019) that simulate the online information environment and adequately reflect the formal and informal learning contexts and conditions students of higher education experience in real life. The focus on the online information environment is therefore, following the tradition of measuring higher-order cognitive skills by means of performance assessments (Braun and Brachem, 2018; Shavelson et al., 2019; Braun et al., 2020), reflected in task scenarios that employ real websites and Internet searches, including sources, platforms, and services that are typical for current online media.

Since designing and developing new performance assessment tasks is particularly resource-intensive and time-consuming, we first looked for existing assessments, which could be possibly adapted and used to validly measure COR skills. In the past, therefore, we tried to measure COR using an adaptation of an Internet-based assessment developed and validated in the United States by the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) to assess the abovementioned recently established concept of “civic online reasoning” at the middle school, high school, and college level (Wineburg et al., 2018). It is an innovative holistic assessment of how students evaluate online information and sources, containing short evaluation prompts, real websites, and an open Internet search (Wineburg et al., 2016; Wineburg and McGrew, 2016). The Stanford History Education Group asked students, for example, to evaluate the credibility of information on political and social issues of mostly U.S.-centric civic interest and to justify their judgment, also citing web sources as evidence (Wineburg and McGrew, 2019).

Based on preliminary validation, however, we further developed and expanded the COR assessment framework. Since an adaptation of this US assessment for the German university context was not feasible due to fundamental differences between the systems of higher education in the two countries, the conceptual-theoretical framework was modified and expanded, resulting in the new construct definition of Critical Online Reasoning described above (Section “The COR construct definition”; for more details, see Molerov et al., 2020; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021a). In this process, a corresponding test definition was developed that provided the basis for the design of new CORA tasks with new scenarios as well as corresponding scoring rubrics to rate students’ responses to the new tasks (for the description of the assessment and the ratings, see Section “Method and design”).

Our newly developed COR performance assessment allows for validly measuring all theoretically defined COR facets (see the section “The COR construct definition”) as we seek to demonstrate with the comprehensive validation presented in this paper.

Validity results

When developing the new COR assessment, the evidence-centered design (ECD) approach of Mislevy (2017) and the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing of AERA, APA, and NCME (2014) were followed to ensure the development of a valid assessment from the very beginning (see section “Conceptual background”). Consequently, as part of the CORA development, we also developed a student model (based on the construct definition), as well as a task model and an interpretive model (based on the test definition), as—according to the evidence-centered design approach—the alignment of these models is necessary for designing valid assessments (Mislevy, 2017). We also followed the standards according to AERA, APA, and NCME (2014) with regard to test development, scoring, and test quality assurance, in particular by conducting initial validity tests during the development of CORA (Molerov et al., 2019, 2020). These were systematically complemented by analyses of the different types of validity outlined in the following.

Content validity

Molerov et al. (2020) conducted a qualitative evaluation of CORA according to the standards of AERA, APA, and NCME (2014), with focus on the task content, i.e., analyzing the coverage of the theoretically derived COR construct facets by the tasks and the suitability of the requirements and content of the newly developed assessment and corresponding scoring approach for higher education in Germany. For this purpose, they conducted an analysis of the task content by means of 12 semistructured interviews with experts in the fields of computer-based performance assessments in higher education, media studies (focusing on online source evaluation or media literacy), linguistics, and cultural studies, which were then analyzed by means of content analyses.

The experts (1) confirmed that the CORA tasks measure the generic COR ability, (2) supported the assumption that CORA measures test participants’ personal construct-relevant abilities in terms of the defined construct definition, and (3) concurred that no specific domain knowledge is required to complete the tasks. The experts also recommended to expand the scope of the assessment, as it was observed that the tasks might be too difficult for first-year students. In addition, some experts referred to the problem that participants’ prior knowledge, interest, beliefs, or (political) attitudes in terms of the task topic could influence their CORA performance.

The additional content analysis confirmed that the assessment and corresponding scoring scheme included two different types of CORA tasks, each prioritizing a different COR facet (online information acquisition and critical information evaluation; Molerov et al., 2020, p. 20). To implement the indications of these analyses, a task format focusing more explicitly on the reasoning skills facet should be included for future assessments (Molerov et al., 2020, p. 20). Consequently, the tasks were expanded by two subtasks each, with a processing time of 10 min per subtask (see section Conceptual background).

Validity of task response processes

In a second validation approach focusing on the validity of task response processes, Schmidt et al. (2020) investigated how test participants’ cognitive processes during task-solving can be described and to what extent certain empirically distinct patterns exist in the participants’ task-and test-solving processes in relation to COR abilities. Therefore, their test-taking process data were collected through verbalizations, eye movements, response times, and computer clicks during the processing of the CORA tasks. Subsequently, Schmidt et al. operationalized the COR construct in two dimensions: At the level of COR ability, which is represented by the score in the CORA tasks (task performance), and at the level of process performance, which is indicated by gaze fixations and response times in the log files (online information processing).

The results showed that better process performance is associated with significantly higher scores, indicating a relationship between participants’ process performance and task performance. Through an analysis of test-taking processes, the two distinct patterns of avoidance strategy and strategic information processing were identified during CORA task-solving. Participants using the avoidance strategy exhibited both poorer process performance and poorer task performance, i.e., they spent most of their time on only one web page, resulting in many fixations that were all focused on one specific process step. In contrast, participants using strategic information processing showed better performance and more intensive processing of online information through a larger number of (total) process steps, which was in line with the theoretical assumption for CORA (for details, see Schmidt et al., 2020).

Internal test structure

Theoretical background

According to the argumentative validation process following AERA, APA, and NCME (2014), evidence for the validity of the CORA scores and their interpretation could already be shown regarding the CORA content and the test takers’ task response processes; initial evidence could also be obtained for correlations with other variables. The assessment’s internal structure is also an important validity aspect, since analyses thereof can “indicate the degree to which the relationships among test tasks and test components conform to the construct on which the proposed test score interpretations are based” (AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014, p. 13). A performance assessment such as CORA, which includes a free Internet search and open-ended written answers that are evaluated by raters, differs fundamentally from classical test procedures with regard to its structure. Therefore, analysis methods according to classical test theory such as task analyses (e.g., test–retest reliability or internal consistency coefficients) are not suitable for this assessment format as they do not comprehensively take into account the complexity of various possible influencing factors that are incorporated in performance assessments in contrast to conventional closed-ended assessments (Cronbach et al., 1972); for more details, see also Shavelson and Webb (1981) and Shavelson et al. (1989). Following Shavelson and Webb (1981), within the framework of Generalizability Theory, it is possible to sufficiently take into account the specifics of performance assessments. Generalizability Theory distinguishes between different components of the assessment, so-called facets, which can exert an influence on the test scores both individually and in interaction (Cronbach et al., 1963). In CORA, such facets are, in addition to test takers’ varying COR abilities and other individual characteristics, certain characteristics of the tasks used (e.g., task topic, format, formulation, or time limits) and effects by the raters, which can also exert a systematic influence and thus affect the test results (Goldman and Brand-Gruwel, 2018; Solano-Flores, 2020).

While certain influences on the test scores are desirable, in particular those of participants’ differing COR abilities or intentional variation of task difficulty, (uncontrolled) influences, for example those of rater effects, should be minimized. In the context of validating the CORA tasks, it should therefore be determined which influences the individual facets of the assessment exert on the scores and how they may interact with each other. The variance decomposition method used in this study allows for the analysis of the influencing factors across different CORA tasks (Jiang, 2018).

Method and design

The process described in the section “Conceptual background” resulted in the new COR assessment framework, which is a computer-based holistic performance assessment that measures students’ and young professionals’ real-world information-processing, decision-making, and judgment skills. It contains criterion-sampled realistic situations that students may encounter in their public and private lives or when studying and working in professional domains (Davey et al., 2015; Shavelson et al., 2018, 2019). Each task consists of a short context description, an objective, and a request to conduct a free Internet search (for a task example, see Figure 1). The participants are prompted to evaluate the online information they found during their search and to write a short open-ended response based on the information found. As the tasks are characterized by an open-ended information environment, with test takers having unrestricted access to the Internet for COR task processing to holistically capture the process of Internet research, those taking the test have to perform a live, open web search, find relevant and credible information, identify and exclude untrustworthy information, and write a short, coherent statement to answer the task prompt. While a processing time of 10 min per task was originally specified, the format was further adapted after the initial validation and extended to 20 min to capture the three COR facets (see section “Conceptual background”) more validly.

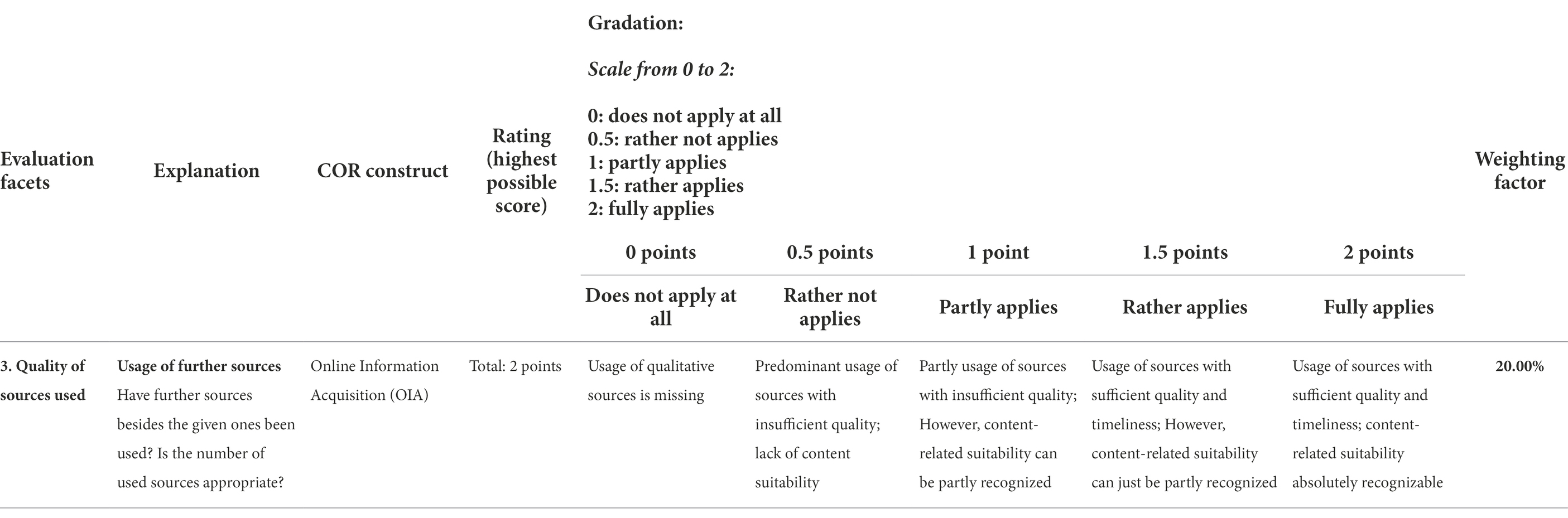

The rating scheme for the scoring of the answers was also accordingly extended and adapted to the new CORA task format, with a greater differentiation and weighting of the individual COR facets aligned with the construct definition. The resulting rating scheme thus distinguishes between six aspects: (1) formulating a clear answer regarding the question, (2) comprehending the task, (3) quality of sources used (for researching general topics as may be encountered in public and private life), (4) accurately evaluating sources, (5) correctly considering arguments of different quality, and (6) giving a reasoned explanation. Depending on the degree of fulfillment, 0–2 points per aspect can be awarded in increments of 0.5, with the respective degree of fulfillment for the point categories described in more detail by behavioral anchors. The different aspects are then included in the overall score with different percentage weightings, depending on their importance to the overall COR construct (for an excerpt of the scoring scheme, see Table 1). While the first part of the task specifically addresses the facets of Online Information Acquisition and Critical Information Evaluation, the second part requires the ability of Reasoning based on Evidence, Argumentation, and Synthesis (see Figure 1).

In addition to the written responses, participants’ browsing histories are recorded during their web search for further analysis (Nagel et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020). Subsequently, the participants’ responses are evaluated by trained raters using the newly developed and validated rating scheme, which takes into account the quality of the sources they used, the correctness of their evaluation of the information found, and the quality of their statements. The collected log data are analyzed, for example, in terms of the number of online sources used and the quality and type of web pages accessed. For this analysis, a new media categorization scheme was developed based on established research approaches (Nagel et al., 2020).

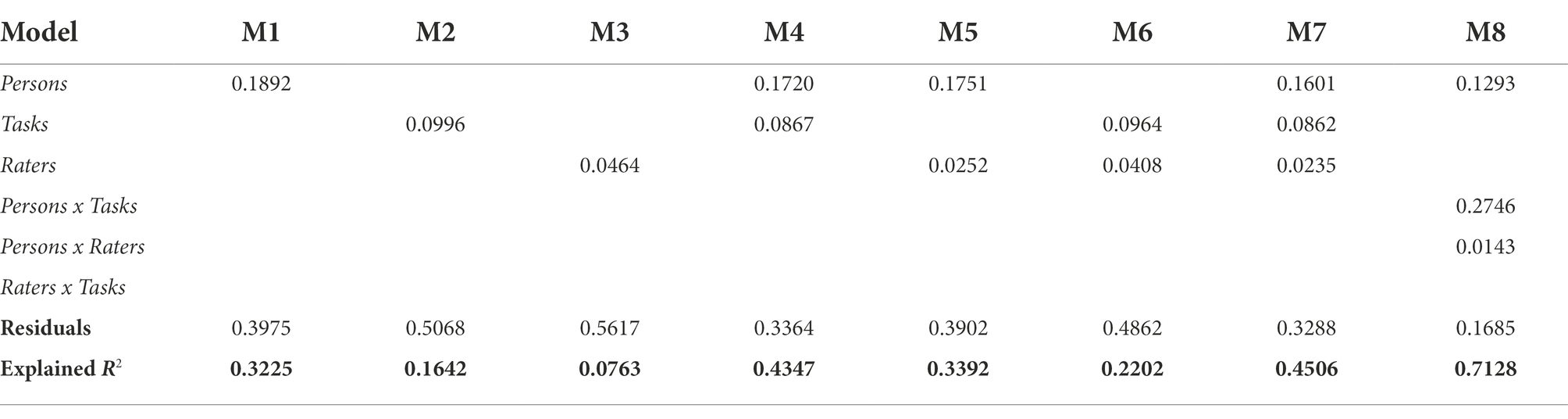

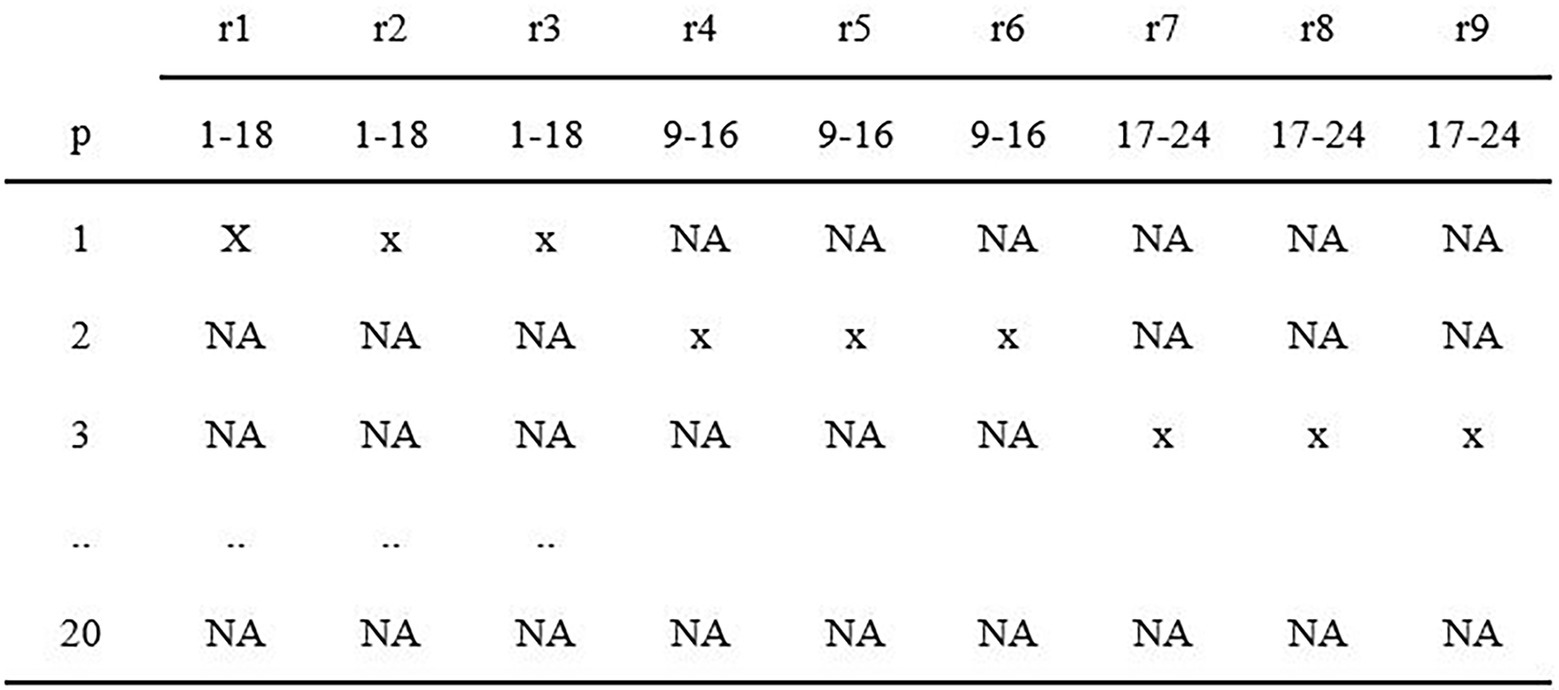

To examine the extent to which different test facets contribute to the variance of the test scores, we analyzed their individual contributions to the total variance of the test scores with the method of variance component analysis (Jiang, 2018). To this end, we computed linear mixed-effect models using R (lme4-package; Bates et al., 2015), in which we differentiated the assessment facets person, i.e., influences specific to the individual participants, rater, i.e., influences of rater effects or the scoring method, and task, i.e., influences of task characteristics, as independent variables (Shavelson and Webb, 1981). The test score was used as the dependent variable. The data set was converted for the analyses so that there was an entry in the dataset for every possible combination of characteristics (see Figure 2; Jiang, 2018). Subsequently, we calculated the linear mixed-effect models by gradually adding the person, rater, and task facets as well as the respective interactions, and compared them on the basis of the residuals and the variance explained in each case.

Figure 2. Exemplary representation of the dataset format for calculating the variance component decomposition (adapted from Jiang, 2018).

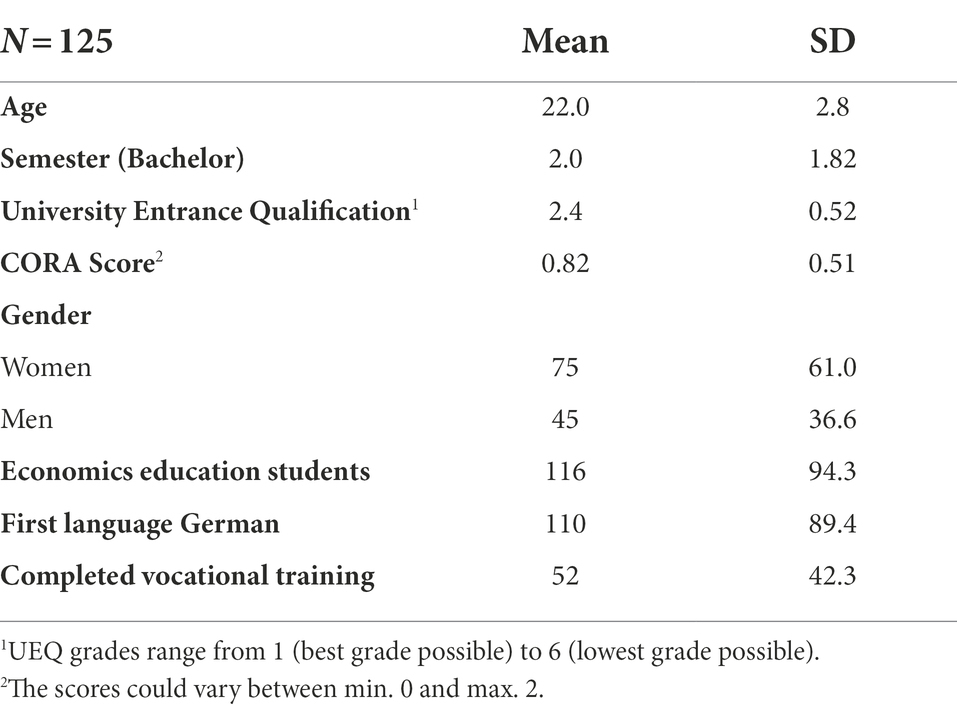

The analyses were conducted with the data of 125 students of economics and economics education at a German university, who participated in the CORA study in 2019–2020. Participants were 61% female, reported a mean age of 22 years (SD = 2.8), and were on average in their second semester of study (SD = 1.82; see Table 2). Participation in the CORA study was voluntary and requested in obligatory introductory lectures. To ensure higher test motivation for their participation in the study, the students received credits for a study module.

The study was conducted via an online assessment platform, which the participants could access individually using access data sent to them in advance. Prior to the survey, the students were informed that their web history would be recorded and that their participation in the experiment was voluntary; all participants signed a declaration of consent to the use of their data for research purposes. Subsequently, the participants were given a standardized questionnaire (approx. 10 min) collecting sociodemographic data such as gender, age, and study semester and their general (self-reported) media use behavior using the validated scale by Maurer et al. (2020). They were also asked to rate the reliability of various media types on a scale of 1 (not at all trustworthy) to 6 (very trustworthy). Due to limited test time, we used a booklet test design. Thereby, students were then given randomly assigned 2–3 CORA tasks to answer (out of a total of six available tasks), which all shared the same structure as well as task description and only differed in topic (for more details on the tasks, see section “Conceptual background”). Participants were asked to enter their written responses to the open-ended questions in the assessment platform, from which they could subsequently log out by themselves. After the assessment, the answers were scored by two trained human raters each, using the newly developed rating scheme (for more details on the scoring process, see section “Conceptual background”), and the scores of all raters for each participant and for each task were averaged to obtain the CORA score1. Participants’ scores between tasks varied (task 1: m = 0.71, SD = 0.64; task 2: m = 1.3, SD = 0.59; task 3: m = 0.53, SD = 0.66; task 4: m = 0.63, SD = 0.54; task 5: m = 0.77, SD = 0.61) with an average overall score of m = 0.84 (SD = 0.51).

Results

Table 3 shows the results of the model calculations of the linear mixed-effect models (Jiang, 2018). First, separate models were computed for the direct effects of the considered facets person, task, and rater and compared to each other, showing already that in comparison, most variance is explained by the person facet (R2 = 0.397), followed by the task facet (R2 = 0.164). In contrast, an influence on the part of the raters was hardly observable (R2 = 0.076). Even when combining the facets in pairs (M4–M6), the model including person and task explains most of the variance (R2 = 0.435). Adding the facet rater in M7 leads only to a slight increase in the explained variance (R2 = 0.451). If, in addition to the direct effects, the interaction effects between the facets were also taken into account, the greatest variance explanation was seen in M8, in which the interactions person x task and person x rater were included in addition to the person facet (R2 = 0.713). In this model, especially the person x task interaction stands out, which can be interpreted in the sense that there are not only general differences between the performances of the individual participants (direct effect of the person facet), but also that the demonstrated performances of the individual test takers differ depending on the task in question (person × task).

In summary, the comparison of the individual facets and their interactions shows that the largest effect on the CORA score is that of the individual test takers’ personal characteristics or their interaction with the different tasks, with the effects of tasks and raters being present but much less pronounced.

Interpretation

The examination of the internal structure of the CORA tasks by means of variance decomposition confirms that, overall, by far the largest part of the score variances is explained by the test takers, as intended in the assessment. Here, it is also important to distinguish between the direct person effects and interaction effects of the participants with the tasks, both of which have an important influence: While the direct effect suggests that interindividual differences (in COR ability) among participants lead to different CORA performance, the interaction effects indicate that participants also perform differently intraindividually depending on the task they are working on. This can possibly be explained by the fact that certain task characteristics (e.g., formulation or the topic of the task) interact with differently developed personal characteristics of the test takers (e.g., different levels of ability in the individual COR facets, certain sociodemographic characteristics, or other personality traits) during task processing. For instance, although the tasks cover general (to the extent that this is possible) social topics, it can be assumed that the participants have a different degree of prior knowledge in certain subject areas due to individual interests, which influences them in their task performance. Which correlations between personal characteristics and CORA performance actually exist, and how these possibly interact with certain task characteristics, must be analyzed in detail in further investigations and falls within the validity criterion of “relationship with other variables” (AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014; section “Relations with other variables”).

While the largest effects can be explained by the test takers, the direct effects of the raters and the tasks turn out to be much smaller, which suggests that, in terms of assessment, there are rather small systematic influences caused by the task properties (e.g., different difficulty) or the rater effects. Nevertheless, it is also necessary to analyze these in further studies, for example, with regard to the task difficulty of individual topics, to ensure the comparability of the respective results. In addition, to be able to draw comparable conclusions about the performance, the tasks should not be used alone, but, as intended in the assessment, rather in combination if possible.

Overall, the analyses confirm that the CORA scores indeed reflect differences in the performance of the participants and are only marginally influenced by rater effects and task properties, which also speaks in favor of maintaining the methodological approach used (rating scheme, rater training, and standardized structure of the tasks).

Nevertheless, it is important for the further development and interpretation of CORA to investigate the causes for the found rater effects more closely and, if necessary, to make adjustments with regard to the rating scheme, the training, and the selection of the raters. Even if the content validity of the tasks and the developed rating scheme has already been demonstrated by the findings of Molerov et al. (2020), it should also be ensured in further analyses and, if necessary, expert interviews that these actually cover only the COR skills and do not, for example, systematically disadvantage individual groups of people due to the task topics (e.g., men/women might have different preferences on health-or sport-related topics).

Relations with other variables

Theoretical background

The previous explanations have shown that (1) the content of the assessment covers the targeted COR skills as expected (section “Content validity”), (2) the difference in test scores results from the participants’ performance in the tasks and not from other aspects of the assessment (section “Internal test structure”), and (3) the tasks trigger different task-solving processes in the participants as expected (section “Validity of task response processes”). Subsequently, it is necessary for the further interpretation and use of the test scores to consider them in the context of further variables with which, according to the underlying COR construct, there should theoretically be (no) correlations. The testing of these relationships is referred to as convergent and discriminant validity, respectively (see also Campbell and Fiske, 1959). According to AERA, APA, and NCME (2014), this type of validity evidence belongs to the category “Evidence based on Relations to other Variables” and provides information on the extent to which the relationships of the test scores with other variables are consistent with the underlying construct and the proposed test score interpretation.

Previous studies, in which the construct related to COR, Civic Online Reasoning, was examined for middle school, high school, and college students in the United States, showed a positive correlation between COR-related skills and study progress (McGrew et al., 2018), in that college students performed better than high school students and high school students performed better than middle school students. Recent studies also concluded that these skills improved with increasing expertise and higher grade level (e.g., Nygren and Guath, 2020; Breakstone et al., 2021; Guath and Nygren, 2022). Also related to the COR construct, which, according to the definition, can be enhanced by corresponding training, students’ COR ability should improve due to increasing experience with online research and the writing of scientifically argumentative texts over the course of studies (Molerov et al., 2020). Thus, in terms of convergent validity, students who are further along in their studies should perform better in CORA than students at the beginning of their studies.

No differences in COR-related abilities were found in previous studies with respect to gender (Breakstone et al., 2021). Moreover, according to the construct definition of COR, gender effects are not expected to occur in research on general social topics. Thus, in terms of discriminant validity, there should be no correlations between the participants’ gender and their CORA scores.

A central aspect of the COR construct is the critical selection, weighting, and use of suitable reliable sources for task-based research (Molerov et al., 2020). In this regard, studies showed that the selection and use of online sources depends to a large extent on their trustworthiness as perceived by users, so that sources perceived as trustworthy are preferred when searching for information (Wathen and Burkell, 2001; Harrison McKnight and Kacmar, 2007; Rowley et al., 2015). Accordingly, a correct assessment of the trustworthiness of (online) sources should also lead to an appropriate differentiation and use of trustworthy versus untrustworthy sources, and thus to better performance in terms of the COR construct (Molerov et al., 2020). Social media in particular, which include video platforms and online encyclopedias, are to be regarded critically in terms of their trustworthiness as they are considered less reliable in terms of their information content (Ciampaglia, 2018; Maurer et al., 2018). Consequently, using such sources may correlate with poorer CORA performance. The use of the Google search engine as an information platform should also be evaluated critically. Search engines such as Google are often the starting point for an Internet-based search and also constitute an important tool for professional fact-checkers when researching information (Speicher et al., 2015; McGrew et al., 2017). However, they display results from media with varying degrees of reliability (which is the reason they lend themselves to the abovementioned practices), and the first search results in particular are often sponsored (Wineburg et al., 2016). Thus, a reasonably low level of confidence in these websites as sources of information should lead to reduced use of these websites and thus higher research quality and a better performance in CORA.

Method and design

The examination of the assumed correlations took place within the same study framework and sample described in the section “Method and design.” Relationship analyses of the CORA score with participants’ age and gender and their media reliability ratings were conducted using correlation analyses (age and media reliability) and a two-sided t-test (gender) in Stata 17 (StataCorp, 2021).

Results

As expected, students in higher semesters achieved better CORA scores than those in lower semesters (r = 0.25, p = 0.006); gender did not play a significant role [t(116) = −2.00, p = 0.05]. Regarding trust in different types of online media, the analyses revealed significant associations between CORA score and reported trust in video platforms (r = −0.239, p = 0.009), online encyclopedias (r = −0.187, p = 0.04), and Google as an information platform (r = −0.19, p = 0.038) for Internet research. These relationships are also reflected in the actual use of online media, where less frequent use of online encyclopedias (r = −0.245, p = 0.037) and Google as an information platform (r = −0.234, p = 0.047) are associated with a better CORA score. Lower trust in video platforms, online encyclopedias, and Google as an information platform as well as less usage of video platforms and online encyclopedias is thus associated with better CORA scores, and greater trust or more use with poorer CORA performance, respectively.

Interpretation

Viewing these results in the context of the external variables we controlled for in our study provides initial evidence that expected correlations exist with respect to both convergent (semester of study, media use) and discriminant (gender) validity. In line with the construct definition, no correlations of CORA performance with gender were found. In contrast, participants who were more advanced in their studies (and thus had already had more learning opportunities in terms of researching information on the Internet as well as writing argumentative texts) showed better CORA performance than students at the beginning of their studies. In addition to institutional learning opportunities, the correlation between general trust in specific types of media for obtaining information and CORA performance, which was expected according to the construct definition, also became evident. These analyses thus confirm that the theoretically formulated basic assumptions regarding the construct, namely the development of COR ability over the course of academic studies and the general importance of media types used, were reflected in the empirically observable correlations with the CORA scores.

Based on the analyses presented here, however, the basic assumptions of the construct cannot yet be considered comprehensively confirmed, since this would first require examining further correlations with other theoretically relevant external variables. With regard to learning opportunities, for example, it would have to be investigated more concretely to what extent COR-developing aspects are actually anchored in the curriculum of the study participants. Furthermore, to gain a better understanding of the (possible) development of COR skills within higher education and beyond, and to what extent these skills can be effectively fostered over the course of academic studies, the actual development of COR skills should also be investigated, for instance in the context of a specific targeted training with comparison groups and pre-post testing, provided that the COR tasks have been proven to be sufficiently valid (Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021a).

Similarly, in terms of media use, the analyses described above cover trust in some media types. While these are highly relevant, especially since, e.g., online encyclopedias are an important source of information for students (Selwyn and Gorard, 2016), the analyses are not exhaustive as they do not (yet) consider other types of higher quality information sources, such as online academic catalogues, professional magazines, or established news sites. Further investigation of the relationship between the CORA score and additional external variables, as well as analyses including participant cohorts other than students, are thus required to provide more comprehensive validation.

Discussion, limitations, and outlook on further research

Today, the Internet has become one of the most important sources of information for learning for university students and young professionals (Brooks, 2016; Newman and Beetham, 2017). However, relying on online resources for information acquisition also presents challenges, as content can be freely distributed on the Internet and vast amounts of unstructured, untrustworthy, inaccurate, or biased information are just as readily available to learners as credible, verified information (Qiu et al., 2017; Ciampaglia, 2018; Maurer et al., 2018). To competently use the information on the Internet, students must be able to critically search, select, review, and evaluate online information and sources based on relevant quality criteria (Molerov et al., 2020; Nagel et al., 2020). To make these skills empirically measurable and to be able to specifically promote them, we developed the new theoretical-conceptual framework of Critical Online Reasoning (Molerov et al., 2020) and a corresponding COR Assessment (CORA) in accordance with the evidence-centered design approach of Mislevy (2017) and the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing of AERA, APA, and NCME (2014).

To ensure that the newly developed assessment actually measures COR abilities as defined by the construct, we followed the argumentative validation process described by AERA, APA, and NCME (2014), according to which the five aspects “test content,” “task-and test-response processes,” “internal structure of a test,” “interrelationships with other variables,” and “consequences of testing” should be analyzed during validation and various sources of information should be used as evidence. In the course of this, evidence for the validity of the CORA scores and their interpretation could already be shown regarding the CORA content (through expert interviews and expert rating of the CORA tasks; Molerov et al., 2020), the task response processes of the test takers (on the basis of log files and eye-tracking data; Schmidt et al., 2020) and, initially, correlations with other variables (regarding number and type of web pages accessed as well as the quality of the content on the web pages; Nagel et al., 2020).

Building on this previous research, the analyses presented here focus on the two criteria “internal structure of the test,” carried out via variance component analysis based on Generalizability Theory, and “correlations with other variables.” The analyses were conducted with the data of 125 students of economics and economics education. The results of the analysis regarding the internal structure of the CORA confirmed that the largest effect on the CORA score is that of the individual test takers’ personal characteristics or their interaction with the different tasks as intended in the assessment, with the effects of tasks and raters being present but much less pronounced. Also, the analyses covering the validity facet “relationship with other variables” confirm that the theoretically formulated basic assumptions regarding the construct exist with respect to both convergent (semester of study, media use) and discriminant (gender) validity. The results of the separate validity analyses are also consistent when viewed as a whole in the sense of a holistic validation argumentation: The presented correlations once again support the expert opinions in Molerov et al. (2020) that the tasks validly measure the COR construct. In addition, they complement the findings of Schmidt et al. (2020) and Nagel et al. (2020) by showing that “good” COR is not only characterized by an appropriate research strategy (i.e., strategic information processing with the use of a larger number of different sources and a larger number of process steps), but that the quality and appropriate evaluation of the sources used also play an important role. At the same time, it can be assumed that individual differences in web search behavior and media use are some of the factors that exert an influence on the CORA score in the context of the direct and interaction effects of the person facet.

For the purpose of further test validation and also a deeper understanding of the COR construct, it is necessary to examine more closely which of the interindividual differences could be identified via the direct effect and thus have an influence independent of the task, and which differences are sensitive to (which) CORA task characteristics as showed in the interaction effects. This concerns both the personal characteristics that were already examined and other characteristics that should be considered additionally, as was also recommended by experts interviewed by Molerov et al. (2020), such as personality traits, prior knowledge, and their relations to the different manifestations of the individual COR facets. While it can be assumed, for example, that personality traits should have a task-overarching effect, the effects of prior knowledge, interests, beliefs, and (political) attitudes may vary depending on the task, and the different characteristics of the individual COR facets could become noticeable via both types of effect. One way to investigate the role of individual influencing factors such as prior knowledge or beliefs during task processing would be by means of cognitive labs with think-aloud commentary (Leighton, 2017), the results of which would also complement the initial eye-tracking studies of Schmidt et al. (2020). These findings would be essential both for the development of specific training tools as well as for ensuring test fairness and in the sense of the validity facet “consequences of testing,” which is the only one that has not yet been investigated in detail. In addition, the effects of the raters and tasks found should be examined more closely for their causes, even though they turned out to be rather small, to minimize possible systematic influences by, for example, rater effects, rating scheme or the format or topics of the tasks. This could be done, for instance, by a systematic comparative analysis of the individual ratings and tasks, or, if necessary, expert interviews to also make sure that the assessment does not systematically disadvantage individual groups of people, e.g., due to rater effects or the task topics. These results can also serve as first analyses in terms of validating the CORA regarding its consequences of testing.

In general, analyses including participant cohorts with students from other study subjects and participants other than students are needed to validate the use of the assessment for a broader population. Since the present analyses were conducted with a comparatively small sample, this would also be helpful in confirming the obtained results and expanding their scope. Although the sample size is sufficient for the analyses carried out, the correlations found could become even more significant with a larger sample, particularly with regard to the analyses carried out. In addition, it is necessary for the validation process to take into account the dynamics prevailing on the Internet, which make it difficult to compare results between participants due to the constantly changing information and media landscape and can also lead to a fast outdating of individual CORA tasks. As a result, it may become necessary to continuously develop new task topics, which also have to be examined for their validity.

The first steps toward implementing the above measures have already been taken in the BRIDGE project (Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2021a). There, by using CORA for students in different study phases, the scope of the assessment was once again checked with regard to the suitability of the task difficulty and above that extended to young professionals. In addition, a comprehensive (sociodemographic) accompanying questionnaire was developed, which covers a variety of personal characteristics, e.g., previous knowledge and personal attitudes on a topic, and thus allows more detailed analyses of influencing factors.

In summary, comprehensive validity evidence is available for the CORA for four of the five criteria for valid tests and test score interpretations recommended by AERA, APA, and NCME (2014), with the “consequences of testing” criterion requiring further investigation. Although further analyses are reasonable regarding all validity criteria and necessary in the sense of the argumentative validity approach according to AERA, APA, and NCME (2014), it can nevertheless be concluded that with the CORA, for the first time, a performance assessment is available for Germany, which can be used in a valid manner to assess the interplay between features of online information acquisition and learning environments and the (cognitive) requirements for critical reasoning from online information in students and young professionals.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

M-TN co-developed and carried out the assessments, conducted the analyses, and co-wrote the article. OZ-T co-developed the assessment, supervised the development and validation process as well as the analyses, and co-wrote the article. JF contributed to the article with a co-workup of the literature relevant to the topic and with co-developing new assessment tasks and a scoring scheme. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study is part of the PLATO project, which is funded by the German federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two reviewers and the editor who provided constructive feedback and helpful guidance in the revision of this manuscript. We would also like to thank all students from the Faculty of Law and Economics at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz who participated in this study as well as the raters who evaluated the written responses. We would also like to thank Katharina Frank, who contributed to the workup of the literature relevant to the topic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For the overall CORA score, a sufficient interrater reliability of Cohens kappa =0.80 (p = 0.000) was determined.

References

AERA, APA, and NCME (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington DC: American Educational Research Association.

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: a necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 10, 16–25. doi: 10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

Aspegren, K., and LØnberg-Madsen, P. (2005). Which basic communication skills in medicine are learnt spontaneously and which need to be taught and trained? Med. Teach. 27, 539–543. doi: 10.1080/01421590500136501

Banerjee, M., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., and Roeper, J. (2020). Narratives and their impact on students’ information seeking and critical online reasoning in higher education economics and medicine. Front. Educ. 5:570625. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.570625

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M., et al. (2012). “Defining twenty-first century skills,” in Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills. eds. P. Griffin, B. McGraw, and E. Care (New York: Springer), 17–66.

Boh Podgornik, B., Dolničar, D., Šorgo, A., and Bartol, T. (2016). Development, testing, and validation of an information literacy test (ILT) for higher education. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 67, 2420–2436. doi: 10.1002/asi.23586

Braasch, J. L. G., Bråten, I., and McCrudden, M. T. (2018). Handbook of Multiple Source Use. New York: Routledge.

Brand-Gruwel, S., Wopereis, I., and Walraven, A. (2009). A descriptive model of information problem solving while using internet. Comput. Educ. 53, 1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.004

Braun, E. (2021). Performance-based assessment of students’ communication skills. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 10:221258682110062. doi: 10.1177/22125868211006202

Braun, E., and Brachem, J. (2018). Erfassung praxisbezogener Anforderungen und Tätigkeiten von Hochschulabsolvent(inn)en (PAnTHoa). Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung 209–232.

Braun, H. I., Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., and Borowiec, K. (2020). Performance assessment of critical thinking: conceptualization, design, and implementation. Front. Educ. 5:156. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00156

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., et al. (2021). Students’ civic online reasoning: a National Portrait. Educ. Res. 50, 505–515. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211017495

Brooks, D. C. (2016). ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology, 2016. EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research. Available at: https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2016/10/ers1605.pdf

Campbell, D. T., and Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 56, 81–105. doi: 10.1037/h0046016

Chan, C. K. Y., Fong, E. T. Y., Luk, L. Y. Y., and Ho, R. (2017). A review of literature on challenges in the development and implementation of generic competencies in higher education curriculum. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 57, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.08.010

Ciampaglia, L. G. (2018). “The digital misinformation pipeline–proposal for a research agenda,” in Positive Learning in the Age of Information. A Blessing or a Curse? eds. O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, G. Wittum, and A. Dengel (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 413–421.

Cronbach, L. J., Gleser, G. C., Nanda, H., and Rajaratnam, N. (1972). The Dependability of Behavioral Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles. New York: John Wiley.

Cronbach, L. J., Nageswari, R., and Gleser, G. C. (1963). Theory of generalizability: a liberation of reliability theory. Br. J. Statis. Psychol. 16, 137–163. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1963.tb00206.x

Davey, T., Ferrara, S., Holland, P. W., Shavelson, R., Webb, N. M., and Wise, L. L. (2015). Psychometric considerations for the next generation of performance assessment: report of the center for K-12 assessment and performance management at ETS [white paper]. Educational Testing Service. Available at: https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/psychometric_considerations_white_paper.pdf

Desai, S., and Reimers, S. (2019). Comparing the use of open and closed questions for web-based measures of the continued-influence effect. Behav. Res. Methods 51, 1426–1440. doi: 10.3758/s13428-018-1066-z

Flanagin, A., and Metzger, M. J. (2017). Digital Media and Perceptions of Source Credibility in Political Communication. The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, vol. 417. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.013.65

Goldhammer, F., Naumann, J., and Keßel, Y. (2013). Assessing individual differences in basic computer skills. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 29, 263–275. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000153

Goldman, S. R., and Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). “Learning from multiple sources in a digital society,” in International Handbook of the Learning Sciences. eds. F. Fischer, C. E. Hmelo-Silver, S. R. Goldman, and P. Reimann (New York: Routledge), 86–95.

Guath, M., and Nygren, T. (2022). Civic online reasoning among adults: an empirical evaluation of a prescriptive theory and its correlates. Front. Educ. 7:721731. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.721731

Hahnel, C., Schoor, C., Kroehne, U., Goldhammer, F., Mahlow, N., and Artelt, C. (2019). The role of cognitive load in university students’ comprehension of multiple documents. Zeitschrift für pädagogische Psychologie 33, 105–118. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000238

Harrison, N., and Luckett, K. (2019). Experts, knowledge and criticality in the age of ‘alternative facts’: reexamining the contribution of higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 24, 259–271. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2019.1578577

Harrison McKnight, D., and Kacmar, C. J. (2007). “Factors and effects of information credibility,” in ICEC’07: Proceedings of the ninth international conference on Electronic commerce. eds. D. Sarppo, M. Gini, R. J. Kauffman, C. Dellarocas and F. Dignum; Association for Computing Machinery, 423–432.

Herrero-Diz, P., Conde-Jiménez, J., Tapia-Frade, A., and Varona-Aramburu, D. (2019). The credibility of online news: an evaluation of the information by university students. Cult. Educ. 31, 407–435. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2019.1601937

Huang, K., Law, V., Ge, X., Hu, L., and Chen, Y. (2019). Exploring patterns in undergraduate students’ information problem solving: a cross-case comparison study. Knowledge Manag. E-Learn. 11, 428–448. doi: 10.34105/j.kmel.2019.11.023

Jiang, Z. (2018). Using the linear mixed-effect model framework to estimate generalizability variance components in R. Methodology 14, 133–142. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000149

Johnson, F., Sbaffi, L., and Rowley, J. (2016). Students’ approaches to the evaluation of digital information: insights from their trust judgments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 47, 1243–1258. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12306

Koltay, T. (2011). The media and the literacies: media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media Cult. Soc. 33, 211–221. doi: 10.1177/0163443710393382

Korn, J. (2004). Teaching talking: Oral communication skills in a Law course. J. Leg. Educ. 54, 588–596.

Ku, K. Y. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: urging for measurements using multi-response format. Think. Skills Creat. 4, 70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2009.02.001

Leeder, C. (2019). How college students evaluate and share “fake news” stories. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 41:100967. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2019.100967

Leighton, J. P. (2017). Using Think-Aloud Interviews and Cognitive Labs in Educational Research. New York: Oxford University Press

Limberg, L., Sundin, O., and Talja, S. (2012). Three theoretical perspectives on information literacy. Hum. IT 11, 93–130.

Liu, O. L., Frankel, L., and Crotts Roohs, K. (2014). Assessing critical thinking in higher education: current state and directions for next-generation assessment. ETS Res. Rep. Ser. 2014, 1–23. doi: 10.1002/ets2.12009

Makhmudov, K., Shorakhmetov, S., and Murodkosimov, A. (2020). Computer literacy is a tool to the system of innovative cluster of pedagogical education. Eur. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. Sci. 8, 71–74. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12310661

Maurer, M., Quiring, O., and Schemer, C. (2018). “Media effects on positive and negative learning,” in Positive Learning in the Age of Information. A Blessing or a Curse? eds. O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, G. Wittum, and A. Dengel (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 197–208.

Maurer, M., Schemer, C., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., and Jitomirski, J. (2020). “Positive and negative media effects on university students’ learning: Preliminary findings and a research program,” in Frontiers and Advances in Positive Learning in the Age of Information (PLATO). ed. O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia (Wiesbaden: Springer), 109–119.

McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith, M., and Wineburg, S. (2018). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theor. Res. Soc. Educ. 46, 165–193. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

McGrew, S., Ortega, T., Breakstone, J., and Wineburg, S. (2017). The challenge that’s bigger than fake news. Civic reasoning in a social media environment. Am. Educ. 41, 4–9.

Mislevy, R. J., Behrens, J. T., Dicerbo, K. E., and Levy, R. (2012). Design and discovery in educational assessment: Evidence-centered design, psychometrics, and educational data mining. Journal of Educational Data Mining 4, 11–48.

Molerov, D., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Nagel, M.-T., Brückner, S., Schmidt, S., and Shavelson, R. J. (2020). Assessing university students’ critical online reasoning ability: a conceptual and assessment framework with preliminary evidence. Front. Educ. 5:577843. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.577843

Molerov, D., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., and Schmidt, S. (2019). “Adapting the civic online reasoning assessment cross-nationally using an explicit functional equivalence approach [paper presentation].” in Annual meeting of the American educational research association, Toronto, Canada.

Nagel, M.-T., Schäfer, S., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Schemer, C., Maurer, M., Molerov, D., et al. (2020). How do University students’ web search behavior, website characteristics, and the interaction of Both influence students’ critical online reasoning? Front. Educ. 5:565062. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.565062

National Research Council (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press

Naumann, J., Richter, T., and Groeben, N. (2001). Validierung des INCOBI anhand eines Vergleichs von Anwendungsexperten und Anwendungsnovizen. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie 15, 219–232. doi: 10.1024//1010-0652.15.34.219

Newman, T., and Beetham, H. (2017). Student digital experience tracker 2017: the voice of 22,000 UK learners. Jisc. Available at: https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6662/1/Jiscdigitalstudenttracker2017.pdf

Nygren, T., and Guath, M. (2020). Students evaluating and corroborating digital news. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 66, 549–565. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2021.1897876

Osborne, J., Pimentel, D., Alberts, B., Allchin, D., Barzilai, S., Bergstrom, C., et al. (2022). Science Education in an Age of Misinformation. Report. Stanford. Available at: https://sciedandmisinfo.stanford.edu/

Oser, F. K., and Biedermann, H. (2020). “A three-level model for critical thinking: Critical alertness, critical reflection, and critical analysis,” in Frontiers and Advances in Positive Learning in the Age of InformaTiOn (PLATO). ed. O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia. (Wiesbaden: Springer), 89–106.

Park, H., Kim, H. S., and Park, H. W. (2021). A Scientometric study of digital literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy, and media literacy. J. Data Info. Sci. 6, 116–138. doi: 10.2478/jdis-2021-0001

Qiu, X., Oliveira, D. F. M., Shirazi, A. S., Flammini, A., and Menczer, F. (2017). Limited individual attention and online virality of low-quality information. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 1–22. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0132

Rammstedt, B. (Ed.) (2013). Grundlegende Kompetenzen Erwachsener im internationalen Vergleich: Ergebnisse von PIAAC 2012. Münster: Waxmann.

Reddy, P., Sharma, B., and Chaudhary, K. (2020). Digital literacy: a review of literature. Int. J. Technoethics 11, 65–94. doi: 10.4018/IJT.20200701.oa1

Rowley, J., Johnson, F., and Sbaffi, L. (2015). Students’ trust judgements in online health information seeking. Health Informatics J. 21, 316–327. doi: 10.1177/1460458214546772

Sanders, L., Kurbanoğlu, S., Boustany, J., Dogan, G., and Becker, P. (2015). Information behaviors and information literacy skills of LIS students: an international perspective. J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 56, 80–99. doi: 10.12783/issn.2328-2967/56/S1/9

Schlebusch, C. L. (2018). Computer anxiety, computer self-efficacy and attitudes toward the internet of first year students at a south African University of Technology. Africa Educ. Rev. 15, 72–90. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2017.1341291

Schmidt, S., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Roeper, J., Klose, V., Weber, M., Bültmann, A.-K., et al. (2020). Undergraduate students’ critical online reasoning: process mining analysis. Front. Psychol. 11:576273. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576273

Selwyn, N., and Gorard, S. (2016). Students’ use of Wikipedia as an academic resource—patterns of use and perceptions of usefulness. Internet High. Educ. 28, 28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.08.004

Sendurur, E. (2018). Students as information consumers: a focus on online decision making process. Educ. Inf. Technol. 23, 3007–3027. doi: 10.1007/s10639-018-9756-9

Shavelson, R. J., and Webb, N. M. (1981). Generalizability theory: 1973–1980. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 34, 133–166. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1981.tb00625.x

Shavelson, R. J., Webb, N. M., and Rowley, G. L. (1989). Generalizability theory. American Psychologist 44, 922–932. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.6.922

Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Beck, K., Schmidt, S., and Mariño, J. P. (2019). Assessment of university students’ critical thinking: next generation performance assessment. Int. J. Test. 19, 337–362. doi: 10.1080/15305058.2018.1543309

Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., and Marino, J. P. (2018). International Performance Assessment of Learning in Higher Education (iPAL): Research and Development. Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Higher Education: Cross-National Comparisons and Perspectives, 193–214. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_10