- Faculty of Education, Psychology and Art, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia

Generic competences have an interdisciplinary nature, which indicates their usability in different disciplines, situations, and contexts in the performance of different tasks. Generic competencies are thus considered from two perspectives, daily life and professional activity, that are equally important, implying that generic competences are necessary for individuals to successfully adapt to change and live meaningful and productive lives. Entrepreneurship competences can be observed from two perspectives: generic competencies viewed from the perspective of the individual's personal experience and professional competencies viewed from the perspective of the individual's professional experience. In this article, it will be observed from both perspectives to see its performance in diverse contexts and to clarify distinctions between these contexts. The present study aimed to shed light on how specific university study disciplines with a professional focus (educational sciences and bioeconomics) support the development of a specific generic competence (entrepreneurship competencies). The Specific Research Questions of This Article Are: (1) What Entrepreneurship Competences Emerge Among Latvian Bioeconomics and Educational Science Students? (2) How Do Entrepreneurship Competences Differ Between Bioeconomics and Educational Science Students? (3) How Are Entrepreneurship Competences Correlated With Each Other? Data for the study were gathered by using the online survey platform QuestionPro. The questionnaire was filled in by 135 students, of whom 82 were from the field of educational sciences and 53 from the field of bioeconomics. The study presents a comparison of entrepreneurship competence's self-assessments of bachelor's, master's, and doctoral students of bioeconomics and educational sciences. Despite the fact that entrepreneurship is more linked to economics, the results show that, in two out of three main areas of entrepreneurship competences, students of educational sciences self-assessed their entrepreneurship competences as higher than students of bioeconomics.

Introduction

Globalization can be defined as an economic, social, political, cultural, and territorial integration process (Arrighi, 2005), resulting in a change in the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to carry out entrepreneurial work, such as the ability to handle digital technologies, knowledge of global processes, and an open attitude toward the cultures of other nations. Differences between the requirements of education and the labor market were the main reason for the development of competences (Grant et al., 1979), contributing to the development of the competence profiles of professional associations, which included requirements applicable to candidates in a particular profession. In this study, entrepreneurial skills were researched from the perspectives of both generic and professional competences to see their performance in diverse contexts and to clarify distinctions between the contexts.

Generic competences have an interdisciplinary nature, which indicates their usability in different disciplines, situations, and contexts in the performance of different tasks (Florea, 2014; Pârvu et al., 2014; Economou, 2016). Generic competences are considered from two perspectives, daily life and professional activity, both of which are equally important (Direito et al., 2014; Larraz et al., 2017; Sá and Serpa, 2018) and indicate that generic skills are necessary for individuals to successfully adapt to change and live meaningful and productive lives (UNESCO, 2016). In the European Higher Education Area, generic competences are described as the skills, knowledge, and attitudes acquired in one situation or field that can be used in other situations, areas, or types of occupations and include communication skills, self-control skills, and problem-solving skills (Akadēmiskās Informācijas Centrs, 2017). (UNESCO, 2016) divides generic competences into six areas:

1. Critical and innovative thinking;

2. Interpersonal skills (e.g., the ability to present, communicate, organize, work in a team, etc.);

3. Intrapersonal skills (e.g., self-discipline, enthusiasm, perseverance, self-motivation, etc.);

4. Global citizenship (e.g., tolerance, openness, respect for diversity, intercultural understanding);

5. Media and information literacy (e.g., the ability to find and access information, analyse and evaluate media content, etc.); and

6. Other skills (this field was created so that researchers could include competences such as physical health or religious values that may not fall into any of the other areas).

Another way to allocate generic skills was suggested by the project “Assessment of competences of students in higher education and dynamics of their development during the study period,” where the following generic competences were listed: research, entrepreneurial skills, innovation, global competences, civic competences, and digital competences (Rubene et al., 2021). These competences emphasize critical thinking, creativity, initiative-taking, problem-solving, risk assessment, decision-making, and the constructive management of emotions (Pepper, 2011).

Professional competences are related to motivation, intelligence, professional performance, and vocational education, which are characterized as skills to interact effectively with one's (social and intellectual) environment and as a result of intensive and continuous learning, which is impossible to implement without the desire to acquire a certain level of professional skills.

It is a general, integrated, and internationalized skill to ensure sustainable, effective performance in a particular professional field, job, organizational context, or task-related situation. It must be also stressed that professional competences are a coordinated set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that can be used to address real professional situations (Mulder, 2014). Given the changing environment, professional competences are inherently unsustainable and need to be developed consistently in the context in which they should be applied (Epstein and Hundert, 2002).

Entrepreneurship competences have normally been researched from the business perspective since traditionally they come from the business area. However, since 2006, entrepreneurship competences have been highlighted as generic skills that are needed in all areas of life (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). Although research has been done on how students of educational sciences self-assess their entrepreneurial skills (Slišāne et al., 2021b), a discipline like bioeconomics that is relatively related to entrepreneurship has not received the attention it deserves. This is despite the fact that entrepreneurship competences have been recognized as an essential part of bioeconomics students' professional development as the related skills are directly used in a professional context (Kuckertz et al., 2020).

Theoretical framework

Entrepreneurship as a generic competence

In 2015, an extensive overview of entrepreneurship competences was created, identifying and comparing different theoretical approaches from both academic and non-academic backgrounds. From the study, it can be understood that although entrepreneurship competences were originally an economic phenomenon and its conceptualization was strongly dependent on the economic aspects of entrepreneurship, the concepts of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial activities have since developed beyond their original economic domain (Komarkova et al., 2015). The authors of EntreComp: The European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (Bacigalupo et al., 2016) reflect the dimensions of entrepreneurial skills that foster innovation, creativity, and self-determination. Entrepreneurship as generic competences is seen as distinct to turn research and education data into economic value and, more broadly, to create social value (Slišāne et al., 2021a) in a personal or a professional context.

Based on extensive baseline analysis (reviews and case studies), EntreComp defines entrepreneurial skills as generic competences as it covers all areas of life, from promoting personal development to active participation in society and (re-)entering the labor market as an employee or self-employed person, as well as start-ups (cultural, social, or commercial; Bacigalupo et al., 2016). Within the framework presented in EntreComp, entrepreneurial skills are described as basic generic competences applicable to individuals and groups, which include three competence areas and 15 dimensions (Bacigalupo et al., 2016).

The three competence areas presented in EntreComp are interconnected:

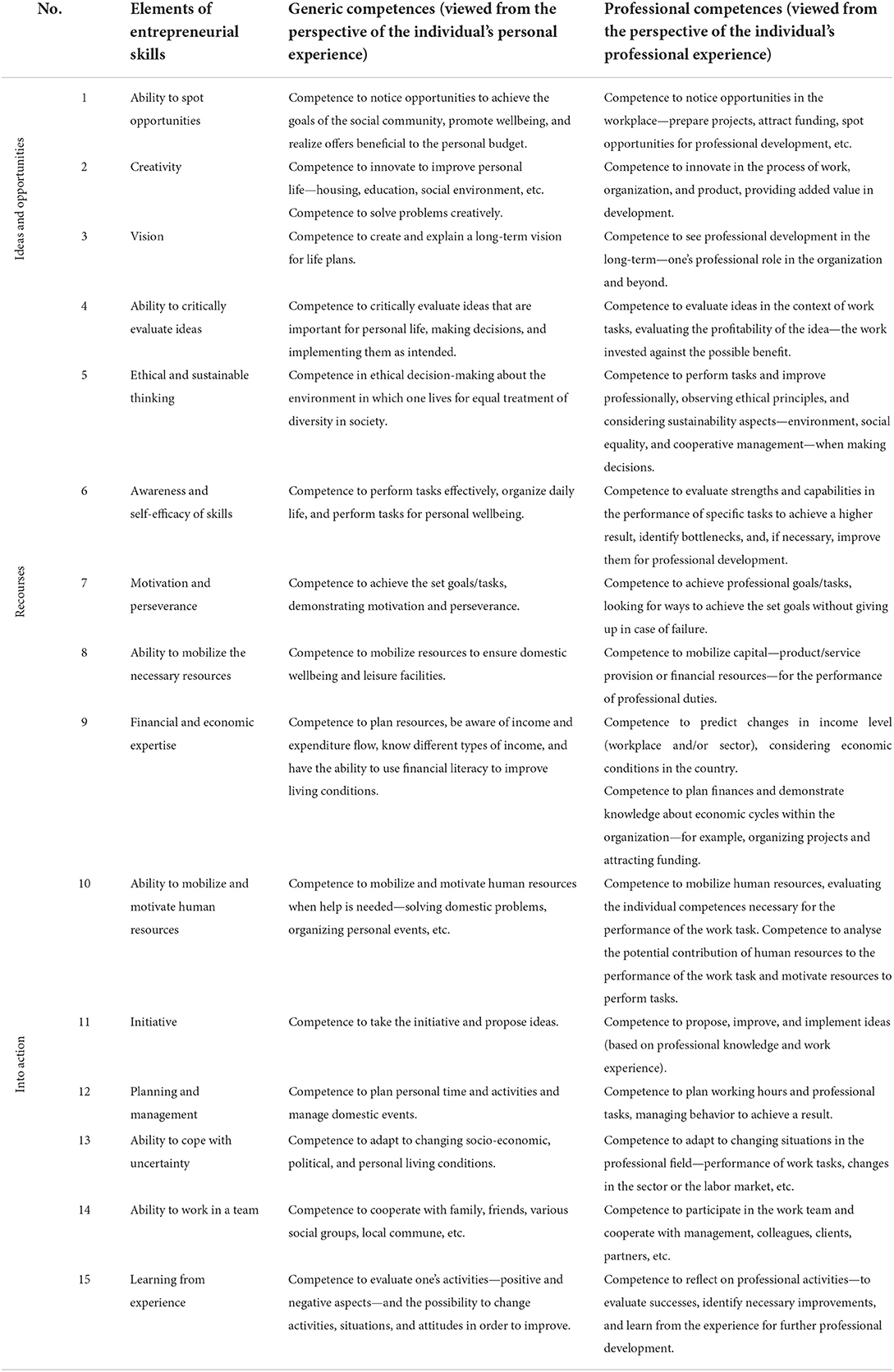

1. Ideas and opportunities: Problem-solving skills and creativity describe the ability to spot opportunities and critically assess them, find a solution that has added value to society/the market, and make strategic, ethical, long-term decisions based on a vision. This area includes five dimensions: spotting opportunities, creativity, vision, evaluation of ideas, and ethical and sustainable thinking.

2. Resources: The identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resources describe the ability to use one's strengths and opportunities to overcome failures and challenges and to mobilize financial and human resources to achieve goals and/or create value. This area includes five dimensions: the assessment of one's abilities, motivation and perseverance; mobilizing resource; financial and economic competences; communication; and human resources mobilization.

3. Into action: Initiative and action orientation describe the ability to show initiative, set goals, plan their achievement, evaluate risks, work and manage a team, evaluate results, and make improvements to achieve the highest possible result. This area includes five dimensions: initiative, planning, action in times of uncertainty, teamwork, and learning from experience.

Entrepreneurial skills are recognized as the key to the development and fulfillment of the individual, active citizenship, social inclusion, and employability in the knowledge society (European Parliament Council, 2006). The concept of the “new economy,” which emphasizes the transition from “manual work” to “knowledge work,” i.e., the need to work with information, can be defined very differently, but the role of information and communication technology (ICT) and the information field in economic processes is constantly emphasized (Neumark and Reed, 2004). Individuals should therefore develop competences to help them successfully enter the labor market, where competitiveness is determined by the ability to apply knowledge (Moretti, 2004; Abel and Gabe, 2011; Kalleberg, 2011; Rubin, 2012). These changes show a growing demand in the labor market for competent individuals who have entrepreneurial skills, as these are important for organizations/companies and are in demand in different positions in the labor market (Szafranski et al., 2017). Furthermore, the structure of entrepreneurial competences indicates skills that are useful not only in the labor market but also in other aspects of life (Komarkova et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurship as a professional competence

The European Union (European Parliament Council, 2006) defines entrepreneurial skills as an individual's ability to translate ideas into action, which includes creativity, innovation, and risk-taking, as well as planning and managing projects to achieve goals. Entrepreneurship competences promote individuals not only in their daily lives at home and in society but also at work, contributing to social or commercial activities. It involves an awareness of ethical values and that entrepreneurial skills are not only about the formation of a company but are also generic and professional competences that help an individual to be proactive, independent, and innovative in his or her personal life, as well as in the workplace (Luppi et al., 2019). Almost every classification of entrepreneurial skills features generic skills (Komarkova et al., 2015), which confirm the generic nature of these skills.

Professional competences include the knowledge and skills necessary for the performance of specific and general work in a particular profession or sector (Mulder, 2014). Professional competences also include one's attitude, which is the desire and motivation to achieve a specific result. Professional competences related to entrepreneurial skills can be classified into four groups: work-related knowledge; skills for work-related tasks; personal qualities that contribute to the achievement of work tasks; and sets of characteristics of the individual that help to achieve meta competences (sets of light skills and other individual qualities that tend to be associated with excellent performance in situations of difficulty, including flexibility, tolerance for ambiguity, ability to learn, reasoning and intuition, creativity, and analytical and problem-solving abilities) (Cheetham and Chivers, 1996, 1998).

According to the Dutch scholar Martin Mulder, and based on the research undertaken by international organizations, professional competences are formed of three complementary components: knowledge, skills, and attitude and values (Mulder, 2014). It is considered both in a narrow context of specific professional activities and in the broader context of common professional standards. Professional competences are contextual, variable, and need to be developed along with changing labor market requirements, which leads to the conclusion that different professions will require different knowledge and skills but could also have complementary competences, such as values.

Entrepreneurial skills from two perspectives—generic and professional competences

To understand the distinction between the performance of entrepreneurial skills as generic and professional competences, and after analyzing the students' self-assessments of their entrepreneurial skills and evaluating the difference between students of bioeconomics and education, the authors created Table 1, where the performance of entrepreneurial skills from the two perspectives can be seen. This was based on the EntreComp conceptual model of entrepreneurial skills, which consists of 15 fundamental elements (Bacigalupo et al., 2016).

Self-monitoring, a skill necessary for effective self-assessment, involves paying focused attention to some aspects of behavior or thinking and actual doing, often in relation to external standards. Thus, self-monitoring concerns awareness of thinking and progress as it occurs, and as such, it helps to identify parts of what students do when they self-assess (McMillan and Hearn, 2008). The second component of self-assessment, self-judgement, involves identifying progress toward targeted performance. Made in relation to established standards and criteria, these judgements give students a meaningful idea of what they know and what they still need to learn (Bruce, 2001). Students find it difficult to manage self-assessment, which leads to data from students' self-assessments not always coinciding with their actual level; however, it should be considered that students' assessment skills constantly improve in the learning process (Slišāne et al., 2021b).

Given that professional competences are a part of the generic competences and overlap with the field of work, the authors assumed that professions where concrete skills are needed more will be more advanced and students would naturally assess it higher. However, it must also be taken into account that different professional fields have higher expectations regarding the level of development, and it might be that self-assessment is higher because of lower expectations.

The specific research questions of this article are thus as follows:

1. What entrepreneurship competences emerge among Latvian bioeconomics and educational science students?

2. How do entrepreneurship competences differ between bioeconomics and educational science students?

3. How are entrepreneurship competences correlated with each other?

The study aims to shed light on how specific university study disciplines with a professional focus (educational sciences and bioeconomics) support the development of a specific generic competence (entrepreneurship competences).

Methodology

In this study, entrepreneurship competences were assessed and compared for students of educational sciences and bioeconomics. Data were gathered by using the online survey platform QuestionPro. The questionnaire was filled in by 135 students from five Latvian universities (Rezekne Academy of Technology, University of Latvia, Daugavpils University, Liepaja University, and Riga Technical University), of whom 82 were from the field of educational sciences and 53 from the field of bioeconomics. The study field of bioeconomics was chosen as a result of the fact that entrepreneurship competences should be improved as both generic and professional competences in this area, while in the field of educational sciences, entrepreneurship competences should only be regarded as generic competences.

The study participants filled out the questionnaire as part of a module in different study programmes. The questionnaire was proposed to students as an alternative to another study. The participants were selected on an accessibility basis. Of the participants, 77% were women and 23% were men, and their average age was 30 years (SD = 8.09, Mo = 24, Me = 28). Of the participants, 18% were bachelor's students, 70% were master's students, and 12% were doctoral students. Students were asked to assess their entrepreneurship competences with 47 statements (Appendix 1) on a 7-point Likert scale (where 1 = not characteristic of me at all and 7 = completely characteristic of me). Their entrepreneurship competences were evaluated through 3 sub-competences that were further divided into 15 dimensions and 47 criteria. The value of each dimension was defined as the mean value of the corresponding statements' self-assessment values and was rounded to 2 decimal places. The sub-competence value was defined as the mean value of all corresponding dimensions' self-assessments rounded to two decimal places. To determine the questionnaire's internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha values were calculated for entrepreneurship competences as well as for each sub-competence separately to make sure that the criteria set for each sub-competence also had internal consistency. Correlations between entrepreneurial dimensions were explored for each study field separately. The exploratory factor analysis was chosen to examine how the questionnaire functions among Latvian bioeconomics and educational science students and to determine the number of factors that could be identified in the data. To determine whether there were statistically significant differences between each sub-competence, an independent sample t-test was carried out on the mean values of the self-assessments of students of educational sciences and students of bioeconomics.

The study used an assessment tool for students' transversal competences developed in the ESF project 8.3.6.2: “Development and Implementation of the Education Quality Monitoring System” 8.3.6.2/17/I/001 (Miltuze et al., 2021; Dimdinš et al., 2022). One of the six transversal competences and two out of eight study fields were analyzed.

The questionnaire was available for completion from 26 November 2020 to 13 March 2021, and the data were analyzed using SPSS and Microsoft Excel. The study considered all ethical research standards in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The questionnaire was completed anonymously and participation in it was completely voluntary.

Results

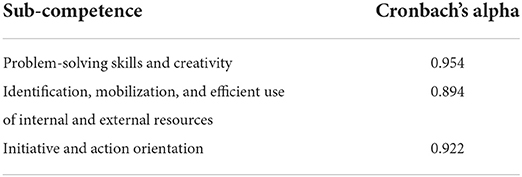

To determine the internal consistency of the Likert scale, the value of Cronbach's alpha was calculated for entrepreneurship competences (α = 0.962) and each sub-competence separately (Table 2). The value of Cronbach's alpha for entrepreneurship competences as a whole and all sub-competences is >0.89 and is therefore considered to be high. Therefore, the Likert scale is reliable.

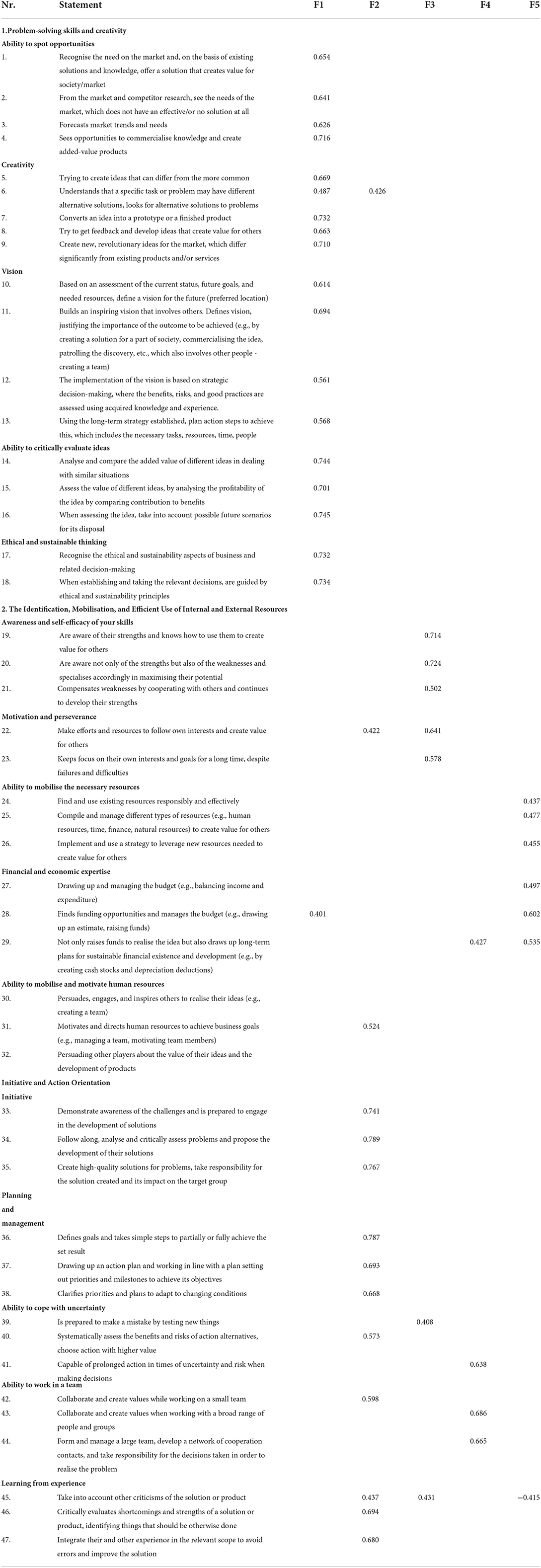

The exploratory factor analysis was chosen to examine how the questionnaire functions among Latvian bioeconomics and educational science students and to determine the number of factors that could be identified in the data. The KMO value (0.882) is >0.8; therefore, the correlation matrix is “meritorious” (Kaiser and Rice, 1974). To reduce the number of factors, the parallel analysis engine was used (Patil et al., 2017). The number of factors to retain will be the number of eigenvalues (generated from the researcher's dataset) that are larger than the corresponding random eigenvalues (Horn, 1965). Therefore, five factors were retained. For interpretation, the Kaiser–Varimax rotation matrix was used (Appendix 1). The results indicate that the statements that measure problem-solving skills and creativity sub-competences are mostly part of the first factor; statements that measure identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resources sub-competences are mostly part of the third and fifth factors; and statements that measure initiative and action orientation are mostly part of second and fourth factors.

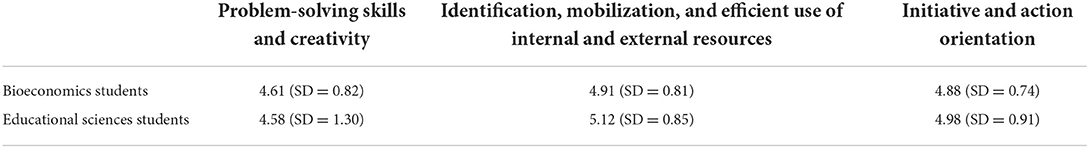

By analysing the self-assessments of entrepreneurship competences in each of its sub-competences and comparing the mean values of the students of educational sciences' and students of bioeconomics' self assessments, it can be concluded that the results are similar. In two out of three sub-competences, students of educational sciences assessed their entrepreneurship skills higher than students of bioeconomics (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean values of educational sciences and bioeconomics students' self-assessments of entrepreneurship sub-competences.

Bioeconomics students' self-assessments' mean values are higher than the self-assessments of educational sciences students in the sub-competence of problem-solving skills and creativity. However, students of educational sciences assessed their identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resource sub-competences and initiative and action orientation sub-competences to be higher than those of bioeconomics students.

When analyzing students' entrepreneurship competences from both a professional perspective and a generic perspective, the results showed that the mean value is higher for educational sciences students than for bioeconomics students according to their own self-assessment. This might not be in line with anyone's expectations considering the essential role and necessity of entrepreneurial capacity in the further professional activities of bioeconomics students. Therefore, it is important to analyse and compare the results in each dimension of the entrepreneurship competences to find answers to the possible reasons for students' self-assessments in each field of study.

Problem-solving skills and creativity

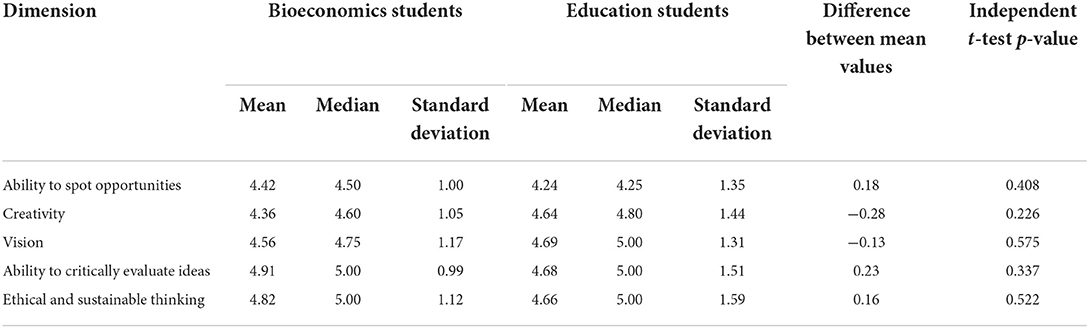

This sub-competence of problem-solving skills and creativity contains five dimensions, three of which have a higher mean value in the self-assessments of bioeconomics students (Table 4).

Table 4. Results of students' self-assessment of the problem-solving skills and creativity sub-competence.

The mean values show that bioeconomics students evaluated the sub-competences of the ability to spot opportunities, the ability to critically evaluate ideas, and ethical and sustainable thinking higher than students of educational sciences. However, the only median value that is higher for bioeconomics students is their ability to spot opportunities, while those for the ability to critically evaluate ideas and ethical and sustainable thinking are exactly the same for students from both study fields. By comparing the mean self-assessment values in the dimensions of creativity (Bioec. st. mean = 4.36, Ed. st. mean = 4.64) and vision (Bioec. st. mean = 4.56, Ed. st. mean = 4.69), it can be seen that higher mean values have been reported by students of educational sciences.

However, with a p-value >0.05 for each sub-competence, the results were not considered statistically significant. An analysis of students' self-assessments standard deviation leads to the conclusion that, in all five dimensions of the problem-solving skills and creativity sub-competence, educational students have significantly higher data dispersion. Further, while the standard deviations for bioeconomics students ranged from 0.99 to 1.17, those of students of educational sciences ranged between 1.31 and 1.59. This points to a polarization of education students' evaluations.

Although creativity and vision are essential parts of bioeconomics and students should therefore develop these competences from a professional perspective, we must keep in mind that they are also essential competences for educators. In the context of entrepreneurship competences, creativity and vision are characterized by the ability to create added value, and the use of external resources is required from a monetary perspective for bioeconomics students, while education students are associated with the ability to create added intellectual value for their pupils. The vision dimension is characterized by the development of future scenarios and the capacity for strategic decision-making, which is necessary as a professional competence both in the context of education and bioeconomics.

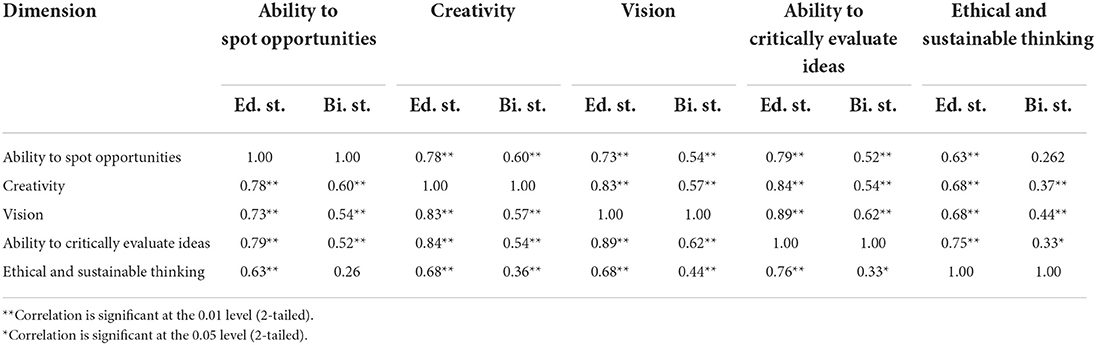

Following an analysis of the Spearman's rank correlations, we can conclude that there are significant differences in the number of dimensions between which a strong correlation (higher than or equal to 0.7) exists in each field of study (Table 5).

Table 5. Spearman's rank correlations between all dimensions of the problem-solving skills and creativity sub-competence.

Strong correlations exist between educational sciences students' ability to spot opportunities, creativity, vision, and ability to critically evaluate ideas in all possible combinations, and there are moderate correlations (between 0.4 and 0.7) between ethical and sustainable thinking and the other four dimensions. For bioeconomics students, there does not exist a strong correlation between any of the problem-solving skills and creativity sub-competences' dimensions. Although 7 out of 10 possible combinations of dimension pairings have a moderate correlation, we can conclude that the relationship between dimensions is significantly weaker in the self-assessments of bioeconomics students.

Consequently, it can be concluded that, within the dimensions of problem-solving skills and creativity, bioeconomics students in the study process most likely need to focus on the ability to spot opportunities, the ability to critically evaluate ideas, and the ability to focus on ethical and sustainable thinking as professional competences. For students of educational sciences, creativity and vision are better developed according to their self-assessments. This could be related to the specific nature of the teacher's work, where it is necessary to focus on both the creative use of different teaching methods in the learning process and the long-term planning of the process to achieve the learning objectives.

The identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resources

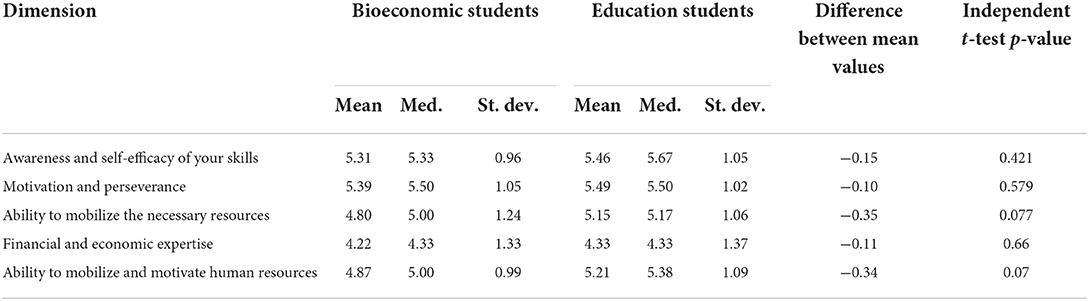

By analyzing the mean values of identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resource sub-competence, it can be concluded that education students have evaluated their competences as higher in all five dimensions (Table 6).

Table 6. Results of students' self-assessment of the identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resource sub-competence.

Awareness and self-efficacy of your skills, motivation and perseverance, and the ability to mobilize and motivate human resources are important competences for future educators, and, therefore, the results are to some degree in line with professional necessities. However, the ability to mobilize the necessary resources and financial and economic expertise are dimensions that are closely related to economics. In both dimensions, the mean value for educational sciences students is higher compared to bioeconomics students' self-assessments. This could indicate that bioeconomics students had higher expectations for the level of their development, and thus, it might be that educational sciences students' higher self-assessment relates to their lower expectations. Educational sciences students' high self-assessments in these two dimensions need to be studied in more detail in future research. However, with a p-value >0.05 for each sub-competence, the results were not considered statistically significant.

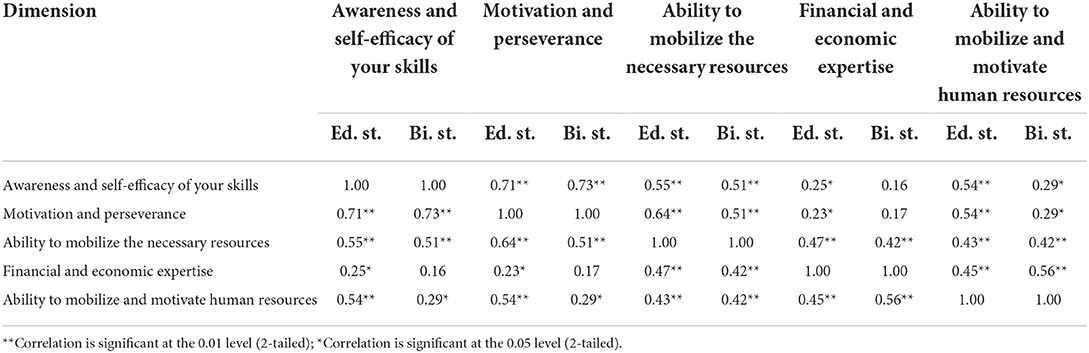

By comparing the median of students' self-assessment in educational sciences and bioeconomics, it can be seen that the median in each of the five dimensions is also higher for education students. Further, by analyzing the correlations between the different dimensions of the identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resources sub-competence, we can conclude that, in the self-assessments of educational sciences students and bioeconomics students, the dimensions between which strong or moderate correlations exist are similar (Table 7).

Table 7. Spearman's rank correlation between all dimensions of the identification, and efficient use of internal and external resources sub-competence.

The only strong correlation that exists is between awareness and self-efficacy of your skills and motivation and perseverance (Bioec. st. = 0.73, Ed. st. = 0.71) for students from both study fields. There is a moderate correlation between 5 out of 10 possible dimension pairings for both study fields, and the correlation coefficient values are similar. This could point to the fact that both sets of students have a similar understanding, and the manifestation of these competences from a professional perspective is similar. However, for dimension pairings like the ability to mobilize and motivate human resources and the ability to spot opportunities (Bioec. st. = 0.29, Ed. st. = 0.54) or mobilize and motivate human resources and motivation and perseverance (Bioec. st. = 0.29, Ed. st. = 0.54), only a moderate correlation exists for educational sciences students, while for bioeconomics students, the correlation between these dimensions is considered to be weak.

Consequently, it can be concluded that students of educational sciences have a higher opinion of their identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resources sub-competence than bioeconomics students. However, the limitations of the self-assessment should be taken into account.

Initiative and action orientation

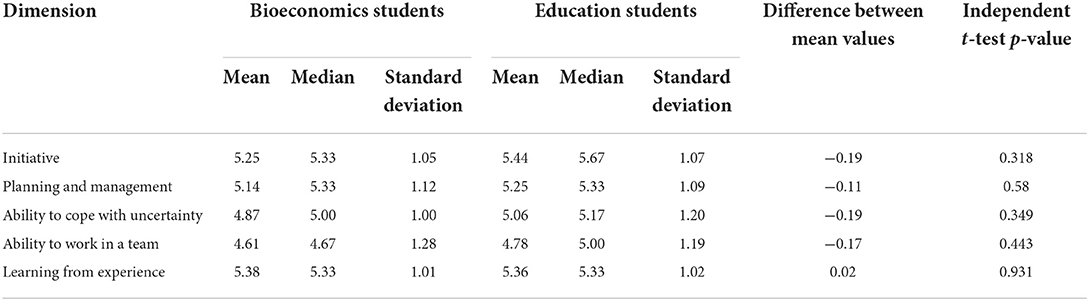

By comparing the mean values of the self-assessments in all dimensions of the initiative and action orientation sub-competence, it can be concluded that, in four out of five dimensions, the mean value is higher for educational sciences students (Table 8).

Table 8. Results of students' self-assessment of the initiative and action orientation sub-competence.

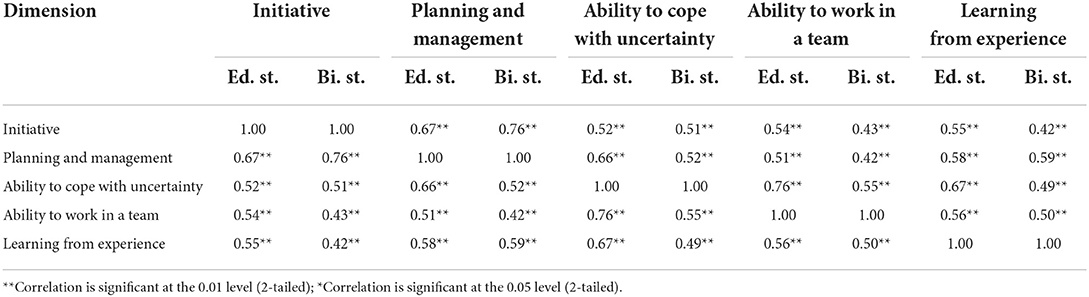

The only mean value that is not higher for educational sciences students in this sub-competence is learning from experience (Bioec. st. = 5.38, Ed. st. = 5.36). However, the content of the other dimensions should be taken into account. The initiative includes taking responsibility and demonstrating initiative when tackling problems. Planning and management include job planning, goal setting, and time management. The ability to cope with uncertainty includes risk assessment and decision-making despite uncertainty. The ability to work in a team includes cooperation with both interested and uninterested parties. All these dimensions are essential parts of the day-to-day work of the educator. Consequently, the high results presented could indicate that these dimensions are necessary for education students to fully prepare for future professional challenges. However, with a p-value >0.05 for each sub-competence, the results were not considered statistically significant. By analyzing the correlation between all dimensions of the initiative and action orientation sub-competence, it can be concluded that there is a moderate or strong correlation between all dimensions for students from both fields (Table 9).

Table 9. Spearman's rank correlation between all dimensions of the initiative and action orientation sub-competence.

Although there is only one dimension pair in each of the fields of study between which there is a strong correlation, the results point to the consistency of the interrelationship between the dimensions in both fields of study. This could point to the fact that the manifestation of the initiative and action orientation sub-competence, both from a professional and a generic individual perspective, is similar in different individual and working contexts for students from both fields of study.

Discussion/conclusion

Entrepreneurship competences consist of two perspectives: generic competences viewed from the perspective of the individual's personal experience and professional competences viewed from the perspective of the individual's professional experience. The present study compared the self-assessments of bioeconomics students' and students of educational sciences' entrepreneurship competences. Despite the fact that entrepreneurship is more linked to economics, the results showed that, in two out of the three sub-competences, students of educational sciences assessed their entrepreneurship competences higher than students of bioeconomics. In the identification, mobilization, and efficient use of internal and external resources (Bioec. st. mean = 4.91, Ed. st. mean = 5.12), and initiative and action orientation sub-competences (Bioec. st. mean = 4.88, Ed. st. mean = 4.98), students of educational sciences self-assessed themselves higher than bioeconomics students, and the mean values for the problem-solving skills and creativity sub-competence are very similar (Bioec. st. mean = 4.61, Ed. st. mean = 4.58).

There are several potential reasons that might have determined the results of the study. First, educational sciences cover a wider spectrum of generic competences needed for everyday work. It is important for the educator not only to be an expert in a specific field of science but, more importantly, to be able to teach others, which includes being able to organize, manage, set objectives, cooperate, communicate, and various other generic competences (Jamil et al., 2015; Osman, 2011), while historically, in Latvian higher education, particularly in STEM sciences, the focus is on knowledge in the learning field (Namsone et al., 2021; Dudareva et al., 2021). Therefore, generic competences are neglected. Further, one of the limitations of the study is the evaluation method used. The accuracy of the self-assessment survey, which is related to the assessment form, is lower compared to objective ability tests or behavioral observations because respondents' responses can be affected by their limited ability to remember specific examples of their behavior, distorted memories of their past behavior, and a general tendency to assess themselves, their skills, and their abilities higher than they actually are (Rubene et al., 2021; Miltuze et al., 2021; Dimdinš et al., 2022). It is possible that specific professional knowledge and understanding of the complexity of the highest levels of competences led bioeconomics students to assess their professional skills more objectively and therefore lower than educational sciences students. The assessment of the dimension of financial and economic expertise also shows this, where students of educational sciences (mean = 4.33) assessed their expertise higher than bioeconomics students (mean = 4.22). It is also important to highlight the situation in Latvia, where students of educational sciences, due to a lack of teachers, start working shortly after starting their studies (OECD, 2020; Koroleva et al., 2017). This allows students to take on a lot of responsibility and to develop the necessary generic competences even further.

However, future studies should focus more closely on the reasons for the differences in the self-assessments. It is necessary to understand whether educational sciences students' high self-assessment of their entrepreneurship competences is linked only to the limitations mentioned above or whether there are specific teaching and learning methods used in educational sciences studies that can serve as examples of good practice for the development of entrepreneurship competences in other fields of study.

Limitations

The self-assessments have a high risk of not being representative because individuals' perceptions of their level are their own valuations from their own perspectives. Data have been taken from a pilot study; thereby, the sample was not representative as there was no random sample with a certain number and the data that contain students representing different study years and study levels need to be taken into account.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AS and GL. Methodology, software, formal analysis, resources, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing: AS. Validation: AS, GL, and ZR. Investigation, data curation, and visualization: GL. Supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: ZR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the projects Strengthening the capacity of doctoral studies at the University of Latvia within the framework of the new doctoral model (Identification no. 8.2.2.0/20/I/006) and Assessment of Competences of Higher Education Students and Dynamics of Their Development in the Study Process (ESF project 8.3.6.2: Development and Implementation of the Education Quality Monitoring System) (Project agreement no. ESS2022/422).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abel, J. R., and Gabe, T. M. (2011). Human capital and economic activity in urban America. Reg. Stud. 45:8, 1079–1090. doi: 10.1080/00343401003713431

Akadēmiskās Informācijas Centrs (2017). Augstākās izglitibas kvalitātes monitoringa sistēmas koncepcija. Available online at: https://aic.lv/content/files/Augst%c4%81k%c4%81s%20izgl%c4%abt%c4%abbas%20kvalit%20%c4%81tes%20monitoringa%20sist%c4%93mas%20koncepcija.pdf accessed May 30, 1985.

Arrighi, G. (2005). “Globalization in world-systems perspective,” in Critical Globalization Studies, eds. R. Appelbaum and W. I. Robinson (New York, NY: Routledge), 33–44.

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., and Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (Luxembourg, Europe: Publication Office of the European Union).

Bruce, L. B. (2001). Student Self-Assessment: Making Standards Come Alive. Classroom Leadership 1:5, 1–6.

Cheetham, G., and Chivers, G. (1996). Towards a Holistic Model of Professional Competence. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 20:5, 20–30. doi: 10.1108/03090599610119692

Cheetham, G., and Chivers, G. (1998). The reflective (and competent) practitioner: a model of professional competence which seeks to harmonise the reflective practitioner and competence-based approaches. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 22:7, 267–276. doi: 10.1108/03090599810230678

Dimdinš, G., Miltuze, A., and Olesika, A. (2022). “Development and initial validation of an assessment tool for student transversal competences,” in Proceedings of Scientific Papers on Human, Technologies and Quality of Education (Riga, University of Latvia).

Direito, I., Duarte, A. M., and Pereira, A. (2014). The development of skills in the ICT sector: analysis of engineering students' perceptions about transversal skills. Int. J. Eng. Ed. 20, 6B. 1556–1561. https://www.it.pt/Publications/PaperJournal/9821

Dudareva, I., Namsone, D., Butkēviča, A., and Cakane, L. (2021). Teacher competence gap identification by using an online test. INTED2021 Proceedings (IATED) 9787–9791.

Economou, A. (2016). Research Report on Transversal Skills Frameworks. Available online at: http://www.ats2020.eu/images/deliverables/D1.1_TransversalSkillsFrameworks_CP.pdf Accessed July 05, 2022.

Epstein, R. M., and Hundert, E. M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 287:2, 226–235. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226

European Parliament and Council (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. Off. J. Eur. Union, (2006/962/EC).

Florea, N. (2014). Contribution to gender studies for competences achievement stipulated by national qualifications framework in higher education (NQFHE). J. Res. Gend. Stud. 4:2, 741–750. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=2974

Grant, G., Elbow, P., Ewens, T., Gamson, Z., Kohli, W., Neumann, W., et al. (1979). On Competence: A Critical Analysis of Competence-Based Reforms in Higher Education (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass).

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 30, 179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447

Jamil, F. M., Sabol, T. J., Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2015). Assessing teachers' skills in detecting and identifying effective interactions in the classroom. Elementary School J. 115, 407–432. doi: 10.1086/680353

Kaiser, H. F., and Rice, J. (1974). Little Jiffy, Mark Iv. Educ. Psychol. Measure. 34, 111–117. doi: 10.1177/001316447403400115

Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s (New York: Russell Sage Press).

Komarkova, I., Gagliardi, D., Conrads, J., and Collado, A. (2015). Entrepreneurship Competence: An Overview of Existing Concepts, Policies and Initiatives—Final Report. Joint Research Centre Technical Report.

Koroleva, I., Trapenciere, I., Aleksandrovs, A., and Kaša, R. (2017) Studentu Sociālie un Ekonomiskie Dzives Apstākli Latvijā. Available online at: https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/media/3943/download Accessed August 06, 2022.

Kuckertz, A., Berger, E. S. C., and Brändle, L. (2020). Entrepreneurship and the sustainable bioeconomy transformation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 37, 332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2020.10.003

Larraz, N., Vázquez, S., and Liesa, M. (2017). Transversal skills development through cooperative learning. Training teachers for the future. On the Horizon 25:2, 85–95. doi: 10.1108/OTH-02-2016-0004

Luppi, E., Bolzani, D., and Terzieva, L. (2019). Assessment of transversal competencies in entrepreneurial education: a literature review and a pilot study. Form@re—Open J. Per La Formazione in Rete 19:2, 251–268. doi: 10.13128/formare-25114

McMillan, J. H., and Hearn, J. (2008). Student Self-Assessment: The Key to Stronger Student Motivation and Higher Achievement. Educ. Horiz. 87:1, 40–49. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ815370

Miltuze, A., Dimdinš, G., Olesika Ābolina, A., Lāma, G., Medne, D., Rubene, Z., et al. (2021). Augstākajā izglitibā studējošo caurviju kompetenču novērtēšanas instrumenta (CKNI) lietošanas rokasgrāmata (Latvijas Universitāte, Riga).

Moretti, E. (2004). Workers' education, spillovers, and productivity: evidence from plant-level production functions. Am. Econ. Rev. 94:3, 656–690. doi: 10.1257/0002828041464623

Mulder, M. (2014). “Conceptions of professional competence,” in International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-based Learning, eds. S. Billett, C. Harteis, and H. Gruber (Dordrecht: Springer), 107–137.

Namsone, D., Cakane, L., and Erina, D. (2021). Theoretical framework for teachers self- assessment to teach 21st century skills. society. integration. education. Proc. Int. Sci. Conf. 2, 402–429. doi: 10.17770/sie2021vol2.6437

Neumark, D., and Reed, D. (2004). Employment relationships in the new economy. Labour Econ. 11:1, 1–31. doi: 10.1016/S0927-5371(03)00053-8

OECD (2020). PISA 2018 Results (Volume V): Effective Policies, Successful Schools, PISA (Paris, OECD Publishing).

Osman, K. (2011). The Inculcation of Generic Skills through Service Learning Experience among Science Student Teachers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 18, 148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.05.022

Pârvu, I., Ipate, D. M., and Mitran, P. C. (2014). Identification of employability skills—starting point for the curriculum design process. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 9:1, 237–246.

Patil, V., Surendra, H. N. S., Sanjay, M., and Donavan, D. T. (2017). Parallel Analysis Engine to Aid in Determining Number of Factors to Retain using R [Computer software]. Available from: https://analytics.gonzaga.edu/parallelengine/ Accessed July 07, 2022.

Pepper, D. (2011). Assessing key competences across the curriculum—and Europe. Eur. J. Educ. 46:3, 335–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2011.01484.x

Rubene, Z., Dimdinš, G., Miltuze, A., Baranova, S., Medne, D., Jansone-Ratinika, N., et al. (2021). Augstākajā izglitibā studējošo kompetenču novērtējums un to attistibas dinamika studiju periodā. 1. kārtas noslēguma zinojums (Riga: Latvia University).

Rubin, M. (2012). Working-class students need more friends at university: a cautionary note for australia's higher education equity initiative. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 31:3, 431–433. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.689246

Sá, M. J., and Serpa, S. (2018). Transversal competences: their importance and learning processes by higher education students. Educ. Sci. 8:3, 126. doi: 10.3390/educsci8030126

Slišāne, A., Lāma, G., and Bernande, M. (2021a). Knowledge valorisation in doctoral studies in latvia: entrepreneurship and the development of research competencies in the study process. Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia 47, 193–210. doi: 10.15388/ActPaed.2021.47.13

Slišāne, A., Lāma, G., and Rubene, Z. (2021b). Self-assessment of the entrepreneurial competence of teacher education students in the remote study process. Sustainability 13, 11. 6424. doi: 10.3390/su13116424

Szafranski, M., Golinski, M., and Simi, H. (2017). The Acceleration of Development of Transversal Competences (Kokkola: Centria University of Applied Sciences).

UNESCO. (2016). School and Teaching Practices for Twenty-first Century Challenges: Lessons from the Asia-Pacific Region. Regional Synthesis Report (Paris: UNESCO).

Appendix

Keywords: entrepreneurial skill, generic skills and competences, professional skills, education, pedagogy

Citation: Slišāne A, Lāma G and Rubene Z (2022) How is entrepreneurship as generic and professional competences diverse? Some reflections on the evaluations of university students' generic competences (students of education and bioeconomics). Front. Educ. 7:909968. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.909968

Received: 31 March 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 13 September 2022.

Edited by:

Heidi Hyytinen, University of Helsinki Centre for University Teaching and Learning, FinlandReviewed by:

Svanborg Rannveig Jónsdóttir, University of Iceland, IcelandMilla Räisänen, University of Helsinki, Finland

Copyright © 2022 Slišāne, Lāma and Rubene. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Agnese Slišāne, YWduZXNlLnNsaXNhbmVAbHUubHY=

Agnese Slišāne

Agnese Slišāne Gatis Lāma

Gatis Lāma Zanda Rubene

Zanda Rubene