- 1Department of College English, North China University of Technology, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Education Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

Although previous studies on teacher agency have examined its manifestations and significance from the socio-cultural perspective, university English as a foreign language (EFL)-speaking instructors’ professional agency has been underrepresented in the Chinese context. Based on a narrative inquiry approach and cross-case analysis, this qualitative multiple case study explores how four university EFL-speaking instructors exercise their professional agency and the key factors facilitating their agency enactment. The study finds that EFL-speaking instructors work as agentic practitioners to translate their career pursuits into concrete teaching duties, teacher learning, and researching. Their different professional agency enactment is closely related to their agency competence, agency disposition, and identity commitment as well as multifarious contextual factors. The findings imply that understanding the trajectories of teachers’ career development and fostering their teacher agency can assist more practitioners in getting ready for future challenges. It is suggested that frontline teachers hold onto the notion of life-long learning, build academic research profiles, and conduct active reflections to enhance their agency. University administrators should consider creating a more conducive environment to boost EFL-speaking instructors’ agency to facilitate their professional development.

Introduction

Teacher agency has been theorized and becomes a significant construct in the field of teacher education and professional learning (Etelapelto et al., 2013). It is said to influence teachers’ decisions, choices, or to bring about changes at the university as well as societal levels. Prior studies that describe teachers-as-technicians who implement assigned tasks uncritically have been challenged by the latest research, which has underscored the proactive role of teacher agency in educational reform (Kayi-Aydar, 2015; Hiver and Whitehead, 2018). Within the current Chinese university context, EFL-speaking instructors are immediate executors of curricular reforms that aim to promote students’ oral communicative competency. China’s Standards of English Language Ability, issued in June 2018, contain specifications and classifications related to “language oral production ability,” such as “oral expression, oral narration, oral description, oral exposition, oral argumentation, oral instruction, and oral interaction” (Ministry of Education, 2018, GF0018 pp. 43–50). According to these standards, speaking courses become a vital vehicle for cultivating students’ oral production ability.

As stipulated by the University English Teaching Guide (National Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board under the Ministry of Education, 2020), there are different requirements and policies concerning how EFL speaking instruction and learning are supposed to take place. Against this backdrop, EFL-speaking instructors may face enormous pressure when promoting students’ oral proficiency due to personal factors and a wider literacy-based educational context. Therefore, much research has emerged regarding how EFL teachers develop their professional identities, autonomy, beliefs, and cognition (Agheshteh and Mehrpur, 2021; Richards, 2021). However, relatively less explicit attention has been paid to EFL teachers’ agency to plan, implement, reflect, and exert control in socio-cultural contexts as agents of change (Tao and Gu, 2016). EFL teachers’ agency remains underrepresented in the Chinese tertiary context (Long and Liao, 2021). In addition, compared with other language skills, L2 speaking instruction remains an area with less scholarly focus as L2 speaking is “the most neglected skill” in second language education (Ibrahim and Hashim, 2021, p. 545).

This multiple case study aims to explore the ways in which four EFL-speaking instructors enact their agency as agentic practitioners and examines how the agency is related to their career development in the Chinese context. In this study, the construct of “professional agency” is more specific and career-related, and it is categorized under the umbrella term “teacher agency.” Exploring EFL-speaking instructors’ professional agency provides an effective approach toward problematizing educational contexts within unique situational constraints, challenges, and opportunities. This study also enables us to probe into teachers’ professional lives from a critical stance. Four EFL-speaking instructors participated in this 16-week study. Semi-structured interviews, teaching syllabuses, and classroom observations were used for data collection. To guide our study, we review pertinent literature on different conceptions and facets of teacher agency, and the links between teacher agency and its socio-cultural context in the following sections.

Conceptions and Facets of Teacher Agency

Teacher agency is a frequently researched topic in the fields of education, psychology, and teachers’ professional development. Early research has defined teacher agency as teachers’ capability to control their career or life using deliberation and selection, and is an essential guarantee for them to retain stability in the changing societal context (Giddens, 1991). Etelapelto et al. (2013, p. 61) claim that professional agency is practiced when teachers “exert influence, make choices, and take stances in ways that affect their work and/or their professional identities.” Hull and Uematsu (2020, p. 213) define teachers’ professional agency as the “feeling of being in control” during one’s career advancement. As a deliberate choice that associates actions with consequences, teacher agency is critical to teachers’ professional development in enhancing their knowledge, refining skills, and constructing teacher identity (Lipponen and Kumpulainen, 2011).

Teacher agency is of the utmost significance in teachers changing career paths. Different factors are related to teacher agency. Agency competence refers to “teachers’ capabilities of actualizing their aspirations” (Ruan, 2019, p. 62). Agency disposition concerns teachers’ personalities and attitudes, which are highly individualized, stabilized, and innate for teachers. It is defined as “the stable and comparably situation-unspecific inclination to make choices and to engage in actions based on these choices with the aim of taking control over one’s life or environment” (Goller and Harteis, 2017, p. 85). EFL teachers may demonstrate different agency competence and disposition toward adopting multiple agentic actions, such as initiating innovative changes at work, proposing facilitative suggestions for change, questioning work-related feedback, building professional networks, or monitoring career development (Sun, 2019). Teacher agency can also be reflected via teacher learning, classroom teaching, research initiatives, and participation in school administrations at various levels (Lai et al., 2016).

More recently, teacher agency has incorporated teachers’ metacognitive abilities—teachers’ beliefs, self-reflection, and self-assessment—into its scope (Ayfer, 2020). This renewed interpretation of teacher agency is conceptually derived from Bandura (2006) who delineated four core properties of teacher agency: intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness. Biesta et al. (2015) assert that the promotion of teacher agency requires implementing individual teachers’ beliefs into their practices and the collective development from all stakeholders. Paris and Lung (2008) focused on novice teachers’ professional agency in the US. Their interview findings suggest that autonomy, perceived self-efficacy, intentionality, and reflectivity are qualities associated with teacher agency in their career development. Ruan (2019) finds that teachers’ autonomy, reflection, efficacy, and emotion fall within the overarching construct of teacher agency.

From the above discussions, the focus on teachers’ cognitive aspects has enriched research on the properties and characteristics of teacher agency. Thus far, most studies investigating the role of teacher agency in professional development have been conducted in general education rather than in university-level language education. Further, how EFL-speaking instructors enact their professional agency is still underrepresented, especially in China’s university context.

Teacher Agency and Socio-Cultural Context

Teacher agency is also thought to be embedded in a social context because it is seen as a temporally constructed engagement in different situational contexts. It emphasizes the integration of time and context when teachers and scholars understand agency within an individual’s life course and within an ever-changing environment (Biesta et al., 2015). A life course is defined as “a sequence of socially defined events and roles that the individual enacts over time” (Giele and Elder, 1998, p. 22). The events and roles, for example, parenthood, marriage, disease, and entry into a career, do not always advance in a fixed sequence, but they make up the fullness of the person’s genuine experience. As such, life course reflects the interplay of social and historical features with personal life anecdotes and development. The life-course theory relies heavily on transitions and trajectories across the individuals’ life span (Mayer, 2009). Some scholars have investigated teacher agency through the lens of life course development with a focus on various stages of a teacher’s evolution in their professional development (Emirbayer and Mische, 1998; Archer, 2007). In this study, a comprehensive understanding of EFL-speaking instructors’ agency starts with the recognition that their life course is deeply affected by “macroeconomic conditions, institutional structures, social background, gender, and ethnicity, as well as acquired attributes and individual resources such as ability, motivation, and aspirations” (Evans, 2017, p. 18).

As a socio-cultural theory researcher, Johnson (2009) claimed that in language teacher education, daily teaching activities and professional development are regarded as social behaviors in essence. Language teachers’ identity construction, learning of specialized knowledge, and classroom instruction are not only influenced by teachers’ personal knowledge, but also are highly related to multiple factors in social contexts (Xu and Xia, 2020). Teacher agency is actualized within socio-cultural conditions, such as school and national curricular settings, professional and power relationships with co-workers, and dominating culture in the communities (Imants and Van der Wal, 2020). Therefore, language teachers’ agency should be understood as a dynamic process rather than an innate capacity. When EFL teachers make deliberate decisions under changing educational contexts, teacher agency is duly constructed amid the uncertainties, instabilities, and dilemmas of professional pedagogical activities. Through life course and socio-cultural perspectives, teacher agency has been perceived to be embedded across individuals’ staged development and diverse social circumstances, which in turn shape teachers’ agency, beliefs, thoughts, and actions.

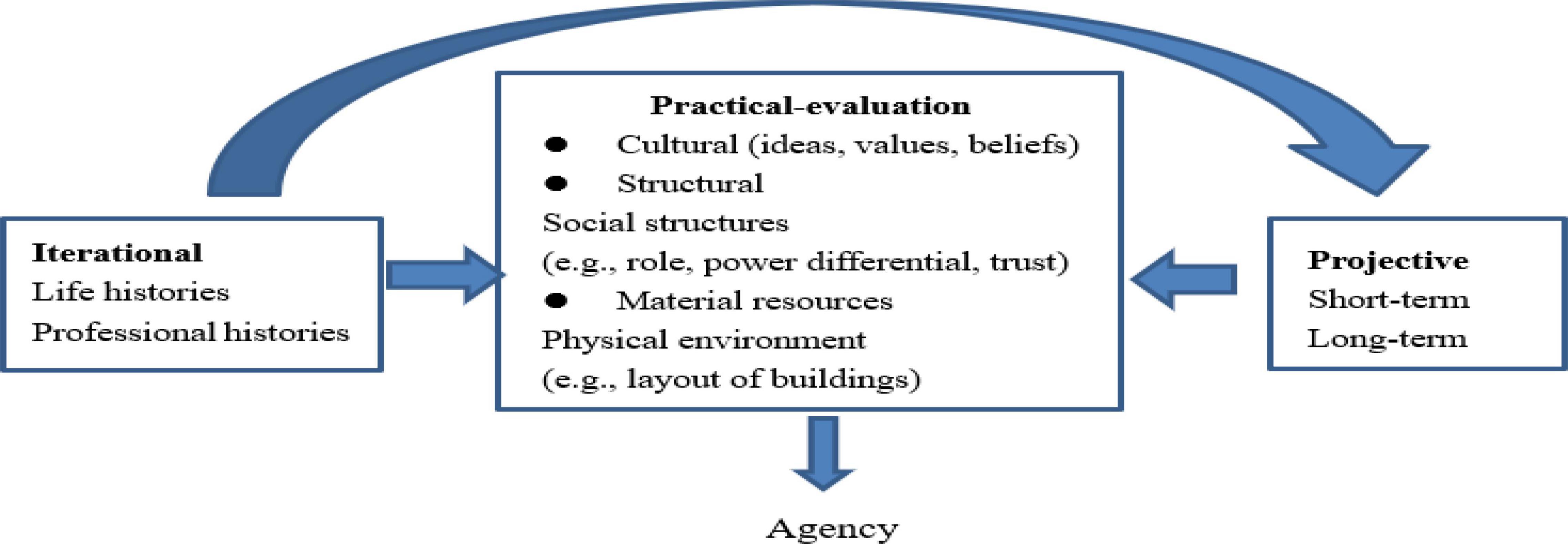

Specifically, Priestley et al. (2013) postulate that the attainment of teacher agency is always informed by teachers’ past experiences (iterational), future development plans (projective) and enacted in a concrete situation (practical evaluation on cultural and structural aspects as well as material resources). These influencing factors are illustrated in Figure 1. The integrated and dynamic individual-and-contextual relations characterize the developmental process of teacher agency.

Figure 1. Chordal triad of human agency (Priestley et al., 2013, p. 192).

English as a foreign language teachers actively position themselves and enact their agency by constructing their discourse, making choices, and reflecting upon specific situations. The exercise of teacher agency is situated within contexts rather than being a completely self-motivated pursuit. Tao and Gu (2016) adopted a narrative inquiry to explore the professional agency of four EFL teachers in China, and found that context played a critical role in their enactment of teacher agency by influencing their cognition and constraining their actions. Ruan (2019) examined female university EFL teachers’ professional agency and concluded that teacher agency was under the influence of workplace, gender, family, and community. These studies have examined how teachers’ career trajectories and life courses are affected by the interplay of various contextual factors, including institutional structures, policies, and socioeconomic conditions.

Previous studies on teacher agency have broadened its connotations and manifestations by incorporating socio-cultural perspectives and life course notions, explored teacher agency from the perspective of the interaction between teachers’ personal attributes and social contexts, and provided an effective approach to probing into teachers’ inner voices and understanding teachers’ experiences. Teachers’ cognitive factors have been analyzed from multiple dimensions such as beliefs, efficacy, agency, and emotions (Billett, 2007; Imants et al., 2013; D’warte, 2021). Among these studies, teacher agency is a critical concept within the literature on professional learning and development (Goller and Paloniemi, 2017). Comparatively speaking, teacher agency has been underexplored, especially among university-level EFL-speaking instructors in the context of mainland China, who shoulder the essential responsibilities of cultivating students’ communicative competence amid educational reforms. Therefore, how EFL-speaking instructors exercise their professional agency in the university context and the factors facilitating their professional agency enactment need to be further explored.

The Conceptual Framework of the Study

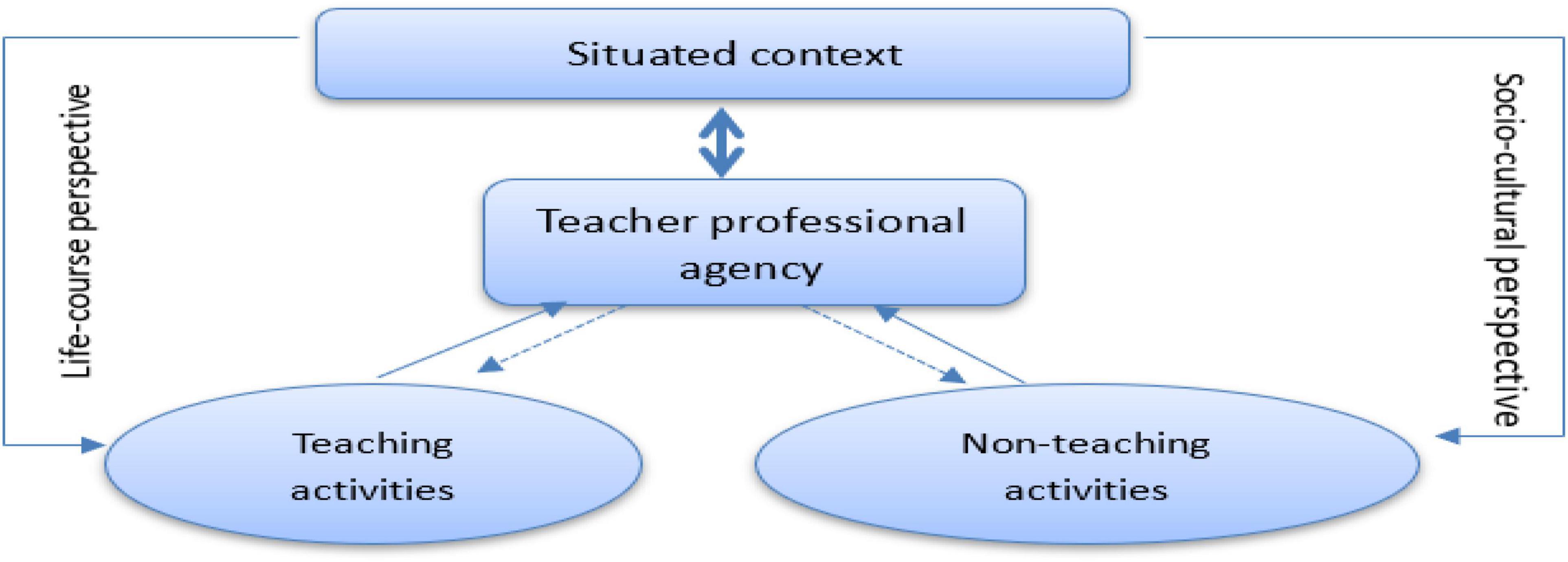

In the above literature review section, we discussed the conceptions and facets of teacher agency as well as the links between agency and context from the life course and socio-cultural perspectives. We now propose a conceptual framework (Figure 2) for this study to explore how teachers’ professional agency is manifested, and how they are situated in the socio-cultural context.

In this conceptual framework, teacher professional agency is demonstrated via multiple teaching activities and non-teaching activities either inside or outside of the classroom setting in a broader context. Teaching activities refer to activities associated with teaching and other curricular activities for students, including class preparation, lesson planning, teaching itself, assigning homework, and marking (Van Droogenbroeck et al., 2014). Non-teaching activities refer to workload of instructors not directly related to student outcomes or activities, including grant writing, paper work, networking, and other managerial, administrative work (Richards, 2018). These two parts constitute teachers’ overall job responsibilities and professional landscape. How EFL-speaking instructors exercise their teacher professional agency are constantly influenced by their interactions with social contexts and relies heavily on transitions and trajectories across their life span. Thus, we need to have a more explicit view of teacher agency enactment in a larger situated context from the life course and socio-cultural perspectives.

The solid double-headed arrows indicate that the situated context will exert influences on teacher agency, and vice versa. The dotted arrows signal that how EFL-speaking instructors enact their professional agency is not easily observable, but needs to be inquired in the study. This framework also serves as an analytical guide for this study.

Methodology

Research Questions

The following two research questions were developed to guide the current study:

1. How do EFL-speaking instructors enact their professional agency in the mainland China universities?

2. What are the contributing factors that facilitate EFL-speaking instructors’ enactment of professional agency?

Research Design

This study adopted a narrative inquiry approach to examine how EFL-speaking instructors enact professional agency and how their enactment of professional agency facilitates their career development. Semi-structured interviews, teaching syllabuses, and classroom observations were used for data collection. Four EFL-speaking instructors participated in this 16-week study.

In qualitative studies, narrative inquiry serves as an effective method of “getting at what teachers know, what they do with what they know and the socio-cultural contexts within which they teach and learn to teach” (Golombek and Johnson, 2004, p. 308). Through the process of telling and retelling the stories of their teaching and research experiences, EFL-speaking instructors’ enactment of their professional agency could be demonstrated from the active interactions between their inner world and the external contexts (Chen, 2012). Concentrating on the four EFL-speaking instructors’ narrated experiences, this study can contribute to our knowledge about their ways of agency enactment, deepening our understanding of the key factors that may influence teachers’ exercise of professional agency. Also, highlighting “teacher agency” as a critical aspect of teacher professional development, the narrative experience may elicit implications for the planning and refinement of teacher education programs. Through our exploration, we hope that more EFL-speaking instructors can enhance their awareness of teacher agency and better understand what agency enactment entails, and thus be able to better cope with challenges in their careers.

Informants

Purposeful sampling and maximum variation sampling were adopted to exhibit diverse characteristics of individual teachers and generate a comprehensive pattern of the studied phenomenon (Miles et al., 2020, p. 28). Four university EFL-speaking instructors were chosen to participate in the study. They taught in different tiers of universities in mainland China, had a range of teaching experiences, and taught various levels of students, including both English majors and non-English majors. Their names are all pseudonyms by referring to Teachers A, B, C, and D. All participants provided their informed consent before joining the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the authors’ affiliated university.

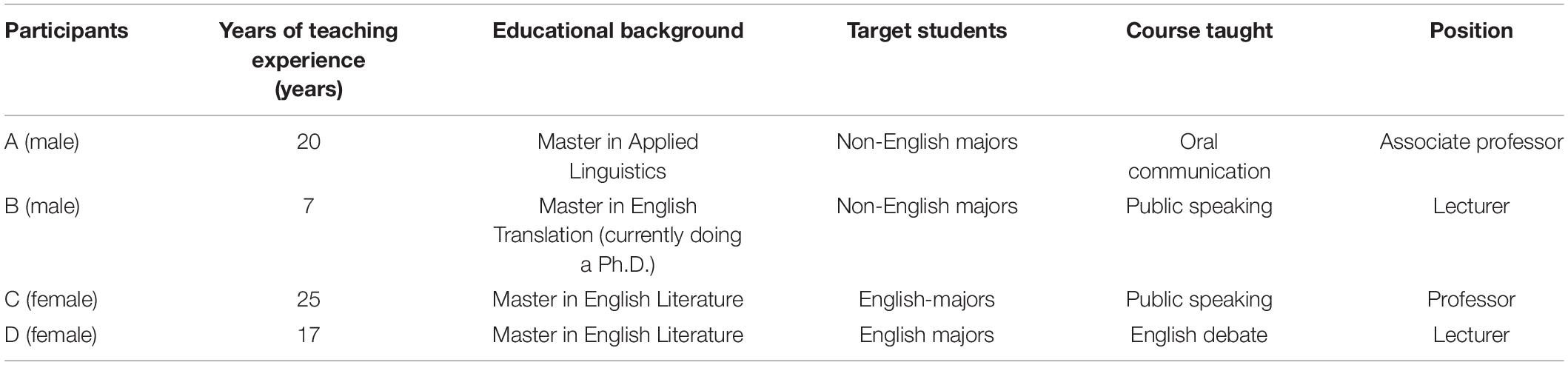

Their demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Data Collection

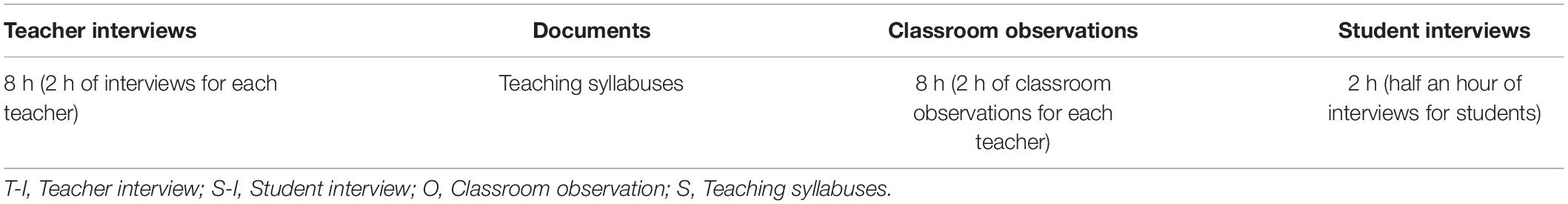

We collected three types of qualitative data, including teaching syllabuses, in-depth formal interviews, and classroom observations (Table 2). The data collection period lasted for one semester. Each participant was interviewed three to four times, with the total time spent on interviews lasting approximately 8 h. Teaching syllabuses were also collected from the four participants. Classroom observations were conducted for a total of 8 h. The purpose of the observations was to examine how EFL-speaking instructors performed their classroom activities, which is a significant component of the manifestation of teachers’ professional agency. Students were also interviewed to assess teaching effectiveness. We designed an interview protocol comprising semi-structured questions around enacting their professional agency. The protocol was used to guide the four EFL-speaking instructors to reflect on key events and influencing factors in their past careers, especially their explanations and illustrations of their behaviors. The first author validated and complemented the data from informal communications with the teachers in their daily lives to enhance the data’s richness and reliability.

Data Analysis

The initial data collected were sorted, classified, and analyzed with reference to how EFL-speaking instructors enact their professional agency in the university contexts. We sought to transcribe the data collected from the video clips lasting around 18 h. All the transcriptions were printed out and manually analyzed to narrow down the themes until the coding was saturated.

A thematic analysis of the various data was adopted in the research study, which usually consists of the procedures as coding, sorting, synthesizing, and theorizing (Merriam, 2009). We highlighted the key themes from the interview data to pave the way for further outlining the data. After identifying the data related to the two research questions, we condensed and presented the data through a coherent narrative description based on its categorizations. Then, we checked the data three times and identified the process and characteristics of how EFL-speaking instructors exercised their agency through teaching and non-teaching activities. The data were then categorized into three primary themes: “teaching duties,” “teacher learning,” and “researching.” We then made a cross-case analysis by comparing the four cases to deepen the understanding and explanation by looking for underlying similarities, associations, and differences to form more general explanations. This analyzing process was non-linear, which means the researchers usually made deletions or modifications in the process.

Concerning trustworthiness of qualitative studies, there are some techniques drawn from qualitative approaches for providing validity and reliability checks on data, namely, triangulation, member checks, rich description, and external auditor, etc. (Creswell, 2017). In this study, triangulation was also applied to ensure the validity of the data analysis and enhance the explanatory power of the results. Firstly, we collected data from different channels, such as classroom observation, teacher interviews, student interviews, and teaching syllabuses. We also attempted to seek assistance from experts and peers in designing the narrative frames and interview questions. Secondly, we returned the data to the teacher participants after transcription for member checking and sought their advice to verify the authenticity of the findings. Third, we adopted peer negotiation after manual analysis to warrant the consistency of the interpretation. After the data were manually analyzed by the first author, they were verified by the second author to ensure reliability.

Findings

Based on the analysis of the four individual cases and the cross-case analysis, we found that all four EFL-speaking instructors took actions as agentic practitioners to facilitate their professional development. They enacted their professional agency primarily through performing teaching duties, learning, and engaging in research.

Professional Agency in Teaching

The instructors planned to be dutiful language coaches, which echoed the deep-seated teacher identity as knowledge transmitters who help address students’ academic issues. They also intentionally endowed their speaking instruction with explicit teaching objectives conducive to student learning in the following ways.

Teacher A, as an instructor of an oral communication course at a Tier 1 university that teaches finance, would like to link a general speaking course with specialized knowledge in finance, and establish English for Specific Purposes (ESP) courses to facilitate students’ development in their majors related to the domains of finance and accountancy. Teacher A stated the following:

“All these years, I tried to combine speaking instruction with the knowledge of finance. My students are all finance majors, and if I can help them fluently express themselves in English, I will have a stronger sense of fulfillment” (A-I-1).

Teacher A also employed a variety of instructional strategies to enhance his teaching effectiveness and enrich his instruction, which included encouraging students to give weekly oral presentations and participate in extracurricular activities, and tutoring students for speech contests (A-S). He required his students to memorize English vocabulary related to finance, and asked them to give oral presentations concerning different aspects of finance, such as currency inflation and deflation (A-O-1). Students regarded speaking about finance knowledge as facilitating their learning in their own majors (S-I). These practices boosted his confidence, and he made the following evaluation of his own teaching:

“I have always groped my way forward. Suppose I can turn this groping into a real teaching reform? I think it is a good thing, which can trigger more of my efforts in this aspect. I think I can better manage the students now, regardless of whether they are adults or freshmen” (A-I-2).

As an instructor of a public speaking course at a Tier 2 university, Teacher B oriented the course as a skill-training class, and concentrated on “assisting students in opening their mouths to speak.” He highlighted three teaching objectives for his class:

“First, refining students’ speech and communication skills; second, improving their speech organization skills; third, enhancing writing and research skills” (B-S).

To actualize the teaching objectives, Teacher B organized the class based on speech tasks. In addition to practicing two speech tasks per semester, students were also required to memorize famous speeches (B-O-2). Nevertheless, due to his overemphasis on the language aspects rather than reaching students on an emotional level, some students noted that the class was boring, and thus they did not give him high teacher evaluations (S-I).

Teacher C, as an instructor of a public speaking course at a Tier 1 university, claimed that her teaching objective was to “help establish students’ confidence in speaking in the public and become capable citizens” (C-S).

“I hope to cultivate students to be competent citizens who are able to participate in social activities and have courage to voice their opinions in public. Confidence and humor will influence the audience” (C-I-1).

Teacher C provided sufficient opportunities for students to practice. Within 16 weeks, the students were required to accomplish five speech tasks, including impromptu speeches, pair work, recitations, and imitations of famous speeches (C-S). She also helped the students comprehend communication skills by incorporation of humor. For instance, she emphasized the humorous language used by Robin Williams in the movie Runaway Vacation. In the film, Williams experiences all kind of ordeals and accidents and finally makes his way to the meeting to deliver the speech, which Teacher C introduced in class.

“Sorry, I came down the mountain. Next time, I’ll take the road. I guess you haven’t received the memo of extreme nature. I love your wilderness so much that I decided to wear it” (C-O-2).

Teacher C then explained that compared with another version of justifying in vain, like “I’m sorry I look so messy and terrible because I had a terrible experience on the way here,” the differences of personality charm were revealed. The use of humor helps attract the attention of the audiences and bond with them. In the student interview, one student told the first author that they liked the humor section very much (S-I).

Teacher D, as an instructor of a debate course at a Tier 2 university, holds a strong aspiration to “help the students become more rational and critical when perceiving social issues, especially hotly contested international issues” (D-S).

“Some students might have mastered specific debating techniques after several semesters of learning, but they still do not possess a systematic way of thinking. Some of them are perplexed especially when persuading and refuting others. What I intend to do is help them make effective refutations” (D-I-2).

Teacher D guided the students to focus on hot social topics, such as wearing masks and human cloning. She worked out ample activities to foster students’ critical thinking, including engaging them in Socratic dialogue and distinguishing logical fallacies (D-O-1&2). Students claimed that they benefited a lot from the refutation process in class (S-I). Teacher D also worked as a transformative intellectual by partnering with local social workers and initiating English debates in the local community (D-I-3).

In summary, the four EFL-speaking instructors’ teaching objectives ranged from facilitating students’ career development, improving their speech-writing skills, boosting their confidence, and enhancing their critical thinking skills. The instructors also took diverse measures to actualize their predesignated aims by establishing ESP courses, organizing writing workshops, providing sufficient opportunities, and initiating thought-provoking topics.

Professional Agency in Teacher Learning

The four speaking instructors practiced their professional agency through constant and continuous professional learning.

Teacher A sought to increase his knowledge of finance by attending seminars organized by his university. His personal aspiration is to be an expert in both English teaching and finance because most of his students are finance majors.

“By attending various seminars, I know much more about finance. I can launch ESP courses now. Relating language learning with finance enriches my life” (A-I-1).

Teacher B aspired to improve his interpersonal competency via his speaking instruction and to become more eloquent and natural when delivering a speech in public:

“I am a little bit introverted and shy on public occasions. I experience stage fright when speaking. I hope I can improve my speaking skills by teaching speech courses. Speaking could facilitate people’s communication skills. Now, I feel more comfortable when talking with others” (B-I-1).

Teacher B regarded speaking instruction as an opportunity for him to practice his speech skills. He also worked as a speech coach, through which he enhanced his confidence and learned to communicate with others better.

As a speech teacher, teacher C would like to improve her specialized knowledge on rhetoric as well as leadership:

“I want to know more about rhetoric, which is the basic knowledge of speech. I also want to enhance my leadership skills. In my administrative work, I always need to listen to others’ viewpoints and then summarize and express my own opinions. So, I need to organize my ideas when speaking. I want to become a better speaker through speech instruction” (C-I-1).

Teacher C read specialized books on rhetoric and consciously integrated rhetoric into her classroom teaching, including using similes, metaphors, analogies, and ironies (C-O-2). She also tried to enhance her leadership skills by giving speeches in public. As a leader in her department, she changed her previous expectations from actualizing her own dream to creating a more conducive environment for her colleagues, which included sending teachers abroad as visiting scholars or helping them to apply for various research projects. She said:

“When I worked as a dean, my role endowed me with more responsibilities. I think I enjoy this process. I hope that, with my efforts, every colleague can develop himself or herself in this context” (C-I-3).

Teacher D harbors an intense motivation to increase her own critical literacy through speaking instruction:

“If teachers are not critical and rational, how can they require their students to be critical? English debate, perhaps, is the most difficult course among the various language courses because it entails critical thinking. I definitely would like to improve my own critical literacy” (D-I-1).

Teacher D attended the yearly conference on the “English debate” organized by the Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press for more than 10 years. She enhanced her own critical literacy by reading relevant literature and tutoring students for debating events at differing levels for years.

In summary, concerning professional teacher learning, the four EFL-speaking instructors strived to enhance their knowledge on ESP, interpersonal competency, leadership, and critical literacy. They exercised their agency by attending seminars, working as a speech coach, studying relevant literature and film for rhetoric, and enhancing critical literacy through speaking instruction.

Professional Agency in Research Engagement

Conducting research was another recurring theme among the four EFL-speaking instructors.

Teacher A attended online workshops to learn more about academic writing as he believed that he “had limited opportunities for receiving training on academic writing.” However, although he was interested, he was not productive because he “had too many duties to fulfill, including administrative work, teaching, and family matters” (A-I-2).

Teacher A was always struggling with his diverse roles. He once took his initiative by resigning from being an administrator. His journey of doing research was not smooth because “seldom could those articles be published and he was very confused and even frustrated” (A-I-3). He once decided to put aside conducting research temporarily by stating that:

“I think a full life is more meaningful than a successful life. I try to manage both; it is an individual choice. I won’t sacrifice my family to conduct research. Besides, the channels for publication are limited” (A-I-1).

Teacher B wanted to improve his competence in conducting research. His confidence was boosted from attending a degree program in translation while working full-time, as his “experience of doing a Ph.D. degree intensified [his] expertise although it is a fresh beginning” (B-I-2). He asserted that:

“We have different perspectives. The university puts much pressure on us, I suffered so much in the troublesome negotiation process with the administrative staff and had to go through all the bureaucracy. But we can choose different routes for development. Just like ‘live and let live.’ Being positive is critical. I think this is the attitude. Pursuing a Ph.D. degree was my way of development” (B-I-2).

Teacher B intentionally combined research with his current speech instruction. He made the following evaluation:

“I applied for a small funded project, although it is of school level, I realize that we need projects to survive under the current system. So, I made my efforts. When combining research with my teaching, I found that there are so many issues worthy of exploration” (B-I-3).

Conducting research was a natural part of Teacher C’s aspiration, as she stated, “the more one teaches, the more one wants to be devoted to doing research” (C-I-2). Besides fulfilling her role as a leader, Teacher C was very dedicated to writing and publishing. She actively applied for several national and school-level projects, worked late into the night to write research papers in the field of English literature. Although facing manuscript rejections for many times, she did not give up until some of the papers got published (C-I-2). She recalled the experience of guiding teachers applying for a high-impact research grant at the national level:

“I never did it out of the wish to earn the honor. I only did it because I wanted to undertake this project. From this opportunity, I learned so many things about my team members” (C-I-2).

This sense of satisfaction further enhanced her confidence as a well-recognized leader in her office, and she organized a community of practice among EFL teachers in her university, where the teachers could learn more about each other’s work. She commented as follows:

“If I do not move ahead, then I will step backward. I am good at dealing with pressure. We have different perspectives on pressure. From the other angle, I am doing pretty smoothly. I enjoy the whole process. My colleagues joke that I am the right person to do research. I would say I am not fit for it, but I am good at communicating with others” (C-I-1).

Teacher D did not incorporate research into her career objectives, as her focus was to “help students better express their ideas” (D-I-2). As she said,

“We need to finish a large amount of work. We need to teach 16 periods of classes 1 week, and we have family matters to deal with. How can I spare that much time on research? In addition, the debate course is a highly practical course; spending time on instruction is more useful than spending time doing research. The university pays us so little, and they are unwilling to make any change” (D-I-3).

In summary, the four EFL-speaking instructors exhibited a diverse focus on research, ranging from showing no interest at all and struggling between teaching and research to balancing both. They employed diverse measures, including attending online workshops, pursuing a Ph.D. degree, applying for research projects, and promoting a community of practice.

Discussion

In this study, the four EFL-speaking instructors participated in critical events in their careers in terms of teaching duties, teacher learning, and researching. It is evident that all four EFL-speaking instructors actively exercise their professional agency to bridge the gulf between their professional goals and career realities. Salient features of teachers’ professional agency are demonstrated in their analyzing problems, creating plans, implementing actions, as well as performing reflections, confirming the notion of “the chordal triad of human agency” proposed by Priestley et al. (2013) in Figure 1 as well as the meaning-making efforts articulated by other researchers (Baumeister and Vohs, 2007; Grant and Ashford, 2008). The process of meaning-making in EFL-speaking instructors’ professional agency is intricate and dynamic, and involves internal factors (e.g., competence, disposition, and identity) and contextual factors (e.g., work environment, school policies, and social milieu) that interact with one another. In the following section, we are going to discuss agency competence and agency disposition plus identity commitments.

Agency Competence

We observed that the EFL-speaking instructors exhibited both selection and compensation competencies. Selection competence is making the best choices and taking appropriate actions, based on teachers’ motives and interests and the requirements posed by society and institutions. Compensation competence reduces negative influences when encountering failures and setbacks in life and maintains self-efficacy and professional identity (Little et al., 2006). These two aspects complement each other, and they helped the university EFL-speaking teachers to cope with the pressures and challenges in their professional lives.

In correspondence with these two competencies, the EFL-speaking teachers attempted two approaches to practice their teacher agency. The first one was to select objectives and their corresponding tactics to seek opportunities for professional development. In this study, the four EFL-speaking instructors sought to facilitate students’ knowledge of finance, speech skills, and enhancing their confidence in speaking and critical thinking by taking various strategies. They also actively expanded their own knowledge repertoire in finance, speech skills, leadership, and critical literacy. The overlap between teaching objectives and teacher learning demonstrated that “teaching and learning complement each other.” They consciously translated their pursuits into concrete teaching duties and their learning. The second was to adjust their beliefs, objectives, and actions to alleviate the negative influences of practice. All four EFL-speaking instructors encountered some setbacks in conducting research. Nevertheless, they sought satisfaction in their teaching and maintained a normal life by protecting their motives, esteem, and self-efficacy. These two approaches coexisted and helped the EFL-speaking teachers explore life values.

EFL-speaking instructors’ action adjustments cannot be simply considered as giving up or turning around, but should be regarded as salient representations of teacher agency. Their evaluations of the rationality of their actions and the attribution of their successes and failures reduced the negative influences on their cognition, and thus protected their psychological wellbeing. The EFL-speaking instructors in this study occasionally attributed their frustrations to the context inside the university, i.e., workload and school administration, or outside the university, i.e., the national policy. Simultaneously, the adjustments of their actions promoted the possibility of actualizing preset objectives (Lai et al., 2016). Even when they met setbacks, they endeavored to take control of their lives by seeking fulfillments in their career development.

Among the four participant teachers, Teacher C demonstrated the highest level of agency competence as she balanced her work and life and combined teaching with conducting research by taking a variety of flexible measures, including setting appropriate aims in her career and making active adjustments. Her success is partly due to her rich professional experiences and her vision and competence to move ahead. Teacher A often struggles to adapt to the professional environment and balance his academic pursuits with his responsibility to look after his family. Teacher B, who has confidence in himself and is the youngest among the four participants, has started implementing new teaching strategies and initiating academic pursuits to improve his teaching effectiveness. Teacher D, who is less “career-driven” than the other three teachers, attempts to fulfill her responsibility through her step-by-step efforts.

Agency Disposition and Identity Commitments

This study also prioritizes the contribution of EFL-speaking instructors’ attitudes and emotions to their professional agency. Overall, the four instructors have exhibited self-regulation and self-reflection when they exercise their agency to teach EFL, become teacher-researcher, and engage with multiple learning activities. They demonstrated their own defining features of agency disposition and identity commitments, which serve as the mediating forces between teachers’ beliefs and practices, and are highly individualized, stabilized, and to some extent, innate in humans.

Teacher C was calm, open-minded, and flexible in her teaching approaches and building a collaborative learning environment. She demonstrated an objective understanding of the university context and was very persistent and determined in turning adverse situations into facilitative environments. Teacher A was not that flexible, and his obstinacy in sticking to the traditional way of teaching led to a teacher-centered approach. Teacher B regarded hardship as an asset, and took the initiative in learning and pursuing a higher degree. We found him to be a young, self-regulated teacher with strict self-discipline. However, this motivation was not intrinsic but extrinsic inasmuch as it was influenced by an institutional promotion requirement that applicants must possess a recognized Ph.D. degree. Teacher D demonstrated strong motivation for teaching but intentionally shied away from conducting research. Although she enjoyed a high level of teacher autonomy, her resistance to conducting research hindered her professional development.

In the process of enacting their professional agency, the four EFL-speaking instructors demonstrated multiple teacher identities, such as course developers, professional learners, researchers, and transformative intellectuals. Teacher A exhibited his identity as a professional learner and course developer. He managed to launch new courses that combined language teaching and knowledge of finance. Nevertheless, he was still struggling with his role as a researcher as he believed that he had not received sufficient training in academic writing and research methods. Teacher B demonstrated his teacher identity as a professional learner and researcher. Undertaking a Ph.D. degree strengthened Teacher B’s interest and capability in conducting research, although “it was just a fresh beginning.” His supervisor’s expectations also inspired him to make a continuous effort. By the time of data collection, he proved successful in his pursuit as a novice researcher and published several research articles on how to write speech scripts. Teacher C acted as an inspiring leader and productive researcher, and the colleagues in her department were motivated by her leadership. Caring not only for her own development, she wholeheartedly considered fellow teachers’ sustainable development. She was proud of her success in fulfilling these diverse teacher roles. Teacher D merely oriented her teaching as a course instructor and did not attach due importance to conducting research. Nevertheless, she harbored strong expectations about influencing her students by cultivating their critical literacy and fostering their independent thinking. Although she failed as a researcher, she succeeded in her new role as a transformative intellectual with her courage and actions.

Teacher C was seen as the most competent among the four participants in fulfilling different teacher roles and translating her career pursuits into concrete teaching duties, research, and teacher learning activities. Teacher B was also actively adjusting himself to the new academic environment. The other two teachers demonstrated partial agency by focusing more on their teaching or struggling with various identities as instructors, administrators, or researchers. They selected relatively unilateral career objectives and primarily relied on the adoption of compensation strategies. On many occasions, they encountered challenges and were trapped in the dilemmas of fulfilling their roles.

Contextual Factors

Teachers make unique plans for their professional development, resulting from the interplay between multiple factors, including personal attributes and context (Lasky, 2005). Teachers’ agency enactment in their identity formation is dynamic and complicated (Morgan, 2004; Lasky, 2005), involving interplays with their life experiences, interpersonal relations, and social values and conditions. The education they received before entering the profession, their language learning experience, and their academic training shape their teaching philosophy and instructional activities. Further, their agency is also reflective of their interpersonal relations. Their diverse identities influence them in their learning and their worldview, life motto, and professional virtues.

Moreover, because a positive and progressive atmosphere in the workplace is likely to mobilize teachers’ empowerment and engagement in their career development, the institutional cultures influence EFL-speaking instructors’ conceptions and practices in a critical manner. For instance, Teacher A worked at a tier 1 university, which posed new opportunities as well as challenges. She cooperated with other colleagues in the department to conduct research on speaking instruction. A bureaucratic system victimized teacher B, yet he became an initiator of a research team because his colleagues supported him. A community practice was established at Teacher C’s university with her active organization and participation. Teacher D was very lonely in her own pursuit, and low financial incentives curbed her motivation to make further pedagogical innovations. The broad social climate, as well as the university culture, influenced their teacher agency. In addition, these agency exercises corroborate the argument that agency can be actualized in both individual and collective forms (Evans, 2017).

Chinese EFL-speaking teachers place much emphasis on harmony and conformity to authority as well as to a fixed and pre-existing social order (Ho and Barton, 2020). They are involved in “the dilemma of free-thinking but are confined in action” (Gu, 2009, p. 187). However, their compliance with arrangements means that they have been deprived of the right to make independent choices, and their agency of maneuvering their own fates has also been undermined. In short, although teachers’ agency can embody their competence in controlling and changing their lives, it is also constrained by various external factors. Therefore, Chinese EFL-speaking teachers cannot completely follow their own wishes in fulfilling their professional roles.

By analyzing the data of the four EFL-speaking instructors, we observe that they enact their professional agency by exhibiting varying agency competence, agency disposition, and identity commitment in the changing and multifarious educational contexts.

Implications

This qualitative study showcased how four EFL-speaking instructors enacted their agency through teaching duties, teacher learning, and conducting research amid the curriculum reforms. Their different professional agency enactment is closely related to their agency competence, agency disposition, and identity commitment. The complexities of the nested relationship between the teachers’ agency and their environment were also highlighted. Teachers’ personal biographies served as an antecedent; their relationships with colleagues and co-workers served as the extended social network, and the institutional, educational, and social culture served as the overall landscape where their beliefs and practices were situated.

It is essential for EFL-speaking instructors to actively exercise their agency competence to bridge the gulf between their aspirations and the realities. Both selection and compensation strategies may be mobilized to direct their career development. They need to enact their agency to select appropriate aims, implement tactics, and make both cognitive and behavioral modifications. They also need to increase their knowledge about themselves, enhance their capabilities to make decisions, break down goals into sub-goals, and conceive workable plans and adjustments that aid them in attaining these sub-goals. EFL-speaking courses require knowledge in diverse domains, such as interpersonal skills, rhetoric, critical thinking, and content in ESP courses. This can be realized in multiple forms of teacher learning, including designated training, coaching, tutoring, and counseling. Observing others’ instructional practices and actively constructing a collaborative learning environment may improve EFL teachers’ sense of professional agency (Heikonen et al., 2020). Additionally, as learning to teach is a lifelong enterprise, it is advisable for EFL-speaking instructors to hold fast onto the belief of life-long learning and enact agentic learning through self-regulation, ongoing in-depth reflections, teacher education programs, and participation in various learning communities.

This study suggests that building academic research profiles for EFL instructors is conducive to their career advancement. To improve their academic competence and productivity, it is highly recommended that EFL-speaking instructors, as agents of research, reinforce the connection between research and teaching activities in practice. They need to read the latest literature, especially domestic and international high-quality journal articles, take part in academic workshops and conferences, cooperate with colleagues and peers, and apply for research programs of different levels.

Further, EFL-speaking instructors’ professional agency is attached to idiosyncratic dispositions which feature individualism. Thus, instructors need to demonstrate flexibility, perseverance, and persistence because undertaking speaking instruction requires patience, intrinsic motivation, and the will to act. It is suggested that positive attitudes and emotions help build proactive agency dispositions, while negative ones (e.g., feelings of inadequacy, dissatisfaction, and sense of frustration) can serve as a prelude for transformative actions.

Moreover, this study sheds light on the progressive forms of EFL-speaking instruction promoted by teachers-as-agents under mainland China university contexts and argues that teachers’ reflections of their instructional agency are central to improving teaching effectiveness. EFL-speaking instructors, as agentic instructors, should consider multiple perspectives in local contexts, including the needs of their students, school culture, existing syllabuses, and language policies. The improvement of the local context needs both collective agency and individual agency, and their pursuit in their agency enactment still needs the joint efforts of the family, the university, and the society.

Conclusion

This qualitative multiple case study explores how EFL-speaking instructors enacted their professional agency in the Chinese university context. By selecting diverse career objectives, implementing corresponding tactics, and making cognitive and behavioral adjustments, the EFL-speaking instructors developed their course instruction, professional learning, and research endeavors. Their differing professional agency enactment can be attributed to their varied agency competence (selection and compensation competences), agency disposition, identity commitment, and contextual factors. The significance of teacher agency not only lies in changing teachers’ professional lives or modifying their personal practices, but also includes maintaining and defending teachers’ orientation and psychological wellbeing in their professional development. EFL teachers are not passive receivers of their destinies but are creators under specific socio-cultural contexts.

Currently, many EFL-speaking instructors seek to resolve the dilemmas within the complicated professional arena. This study may bring enlightenment to them amid challenges, such as realizing the possibility of directing professional development and avoiding the loss of motivation or the sacrifice of personal goals. We also appeal to school administrators to provide a reliable support system on the policy and spiritual levels to facilitate EFL-speaking instructors’ professional development with their efforts. This study’s limitations lie in the small sample size and the possibility of not capturing all the important nodes in EFL-speaking instructors’ dynamic career trajectories within the limited data collection period. Therefore, future studies may involve more teacher informants of diverse cultural backgrounds and conduct in a longer timeframe (i.e., longitudinal studies) to mirror the dynamic and situated process of EFL-speaking instructors’ professional agency development.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the North China University of Technology. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agheshteh, H., and Mehrpur, S. (2021). Teacher autonomy and supervisor authority: power dynamics in language teacher supervision in Iran. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 9, 87–106.

Archer, M. S. (2007). Making our Way Through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511618932

Ayfer, S. B. (2020). Metacognitive awareness of prospective EFL teachers as predictors for course achievement: teaching English to young learners. Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. 7, 160–175.

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Baumeister, R. F., and Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Comp. 1, 115–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., and Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach. Teach. 21, 624–640. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

Billett, S. (2007). “Work, subjectivity and learning,” in Work, Subjectivity, and Learning: Understanding Learning Through Working Life, ed. S. Billet (Berlin: Springer), 1–20. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-5360-6_1

Chen, X. M. (2012). Qualitative Research Methods and Social Sciences Research. Troja: Educational Science Publishing House.

Creswell, J. W. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

D’warte, J. (2021). Facilitating agency and engagement: visual methodologies and pedagogical interventions for working with culturally and linguistically diverse young people. Lang. Teach. Res. 25, 12–38. doi: 10.1177/1362168820938826

Emirbayer, M., and Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? Am. J. Sociol. 103, 962–1023. doi: 10.1086/231294

Etelapelto, A., Vahasantanen, K., Hokka, P., and Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Evans, K. (2017). “Bounded agency in professional lives,” in Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds M. Goller and S. Paloniemi (Berlin: Springer), 17–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_2

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Later Modern Age. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Giele, J. Z., and Elder, G. H. (1998). “Life course research: development of a field,” in Methods of Life Course Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, eds J. Z. Giele and G. H. Elder (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 5–27. doi: 10.4135/9781483348919.n1

Goller, M., and Harteis, C. (2017). “Human agency at work: towards a clarification and operationalisation of the concept,” in Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development, eds M. Goller and S. Paloniemi (Berlin: Springer), 85–103. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_5

Goller, M., and Paloniemi, S. (2017). “Agency at work, learning and professional development: an introduction,” in Agency at Work, eds M. Goller and S. Paloniemi (Berlin: Springer), 1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_1

Golombek, P. R., and Johnson, K. E. (2004). Narrative inquiry as a mediational space: examining emotional and cognitive dissonance in second-language teachers’ development. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 10, 307–327. doi: 10.1080/1354060042000204388

Grant, A. M., and Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 28, 3–34. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.002

Gu, P. Y. (2009). Case Studies of Excellent EFL Teachers’ Professional Development. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., Soini, T., and Pyhältö, K. (2020). The development of student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom during teacher education. Learn. Res. Pract. 6, 114–136. doi: 10.1080/23735082.2020.1725603

Hiver, P., and Whitehead, G. E. K. (2018). Sites of struggle: classroom practice and the complex dynamic entanglement of language teacher agency and identity. System 79, 70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.04.015

Ho, L. C., and Barton, K. C. (2020). Critical harmony: a goal for deliberative civic education. J. Moral Educ. 51, 276–291. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2020.1847053

Hull, M. M., and Uematsu, H. (2020). “Development of preservice teachers’ sense of agency,” in Research and Innovation in Physics Education: Two Sides of the Same Coin, eds J. Guisasola and K. Zuza (Berlin: Springer), 209–223. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-51182-1_17

Ibrahim, S. K. S., and Hashim, H. (2021). Enhancing English as a second language learners’ speaking skills through authentic videoconferencing. Creat. Educ. 12, 545–556. doi: 10.4236/ce.2021.123037

Imants, J., and Van der Wal, M. M. (2020). A model of teacher agency in professional development and school reform. J. Curric. Stud. 52, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2019.1604809

Imants, J., Wubbels, T., and Vermunt, J. D. (2013). Teachers’ enactments of workplace conditions and their beliefs and attitudes toward reform. Vocat. Learn. 6, 323–346. doi: 10.1007/s12186-013-9098-0

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second Language Teacher Education: A Socio-Cultural Perspective. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203878033

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). Multiple identities, negotiations, and agency across time and space: a narrative inquiry of a foreign language teacher candidate. Crit. Inq. Lang. Stud. 12, 137–160. doi: 10.1080/15427587.2015.1032076

Lai, C., Li, Z., and Gong, Y. (2016). Teacher agency and professional learning in cross-cultural teaching contexts: accounts of Chinese teachers from international schools in Hong Kong. Teach. Teach. Educ. 54, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.007

Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 899–916. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003

Lipponen, L., and Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001

Little, T. D., Snyder, C. R., and Wehmeyer, M. (2006). “The agentic self: on the nature and origins of personal agency across the lifespan,” in Handbook of Personality Development, eds D. Mroczek and T. D. Little (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 61–79.

Long, D. Y., and Liao, Q. Y. (2021). Towards the agency of university foreign language teachers in the context of new liberal arts. Foreign Lang. Lit. 37, 139–146.

Mayer, K. U. (2009). New directions in life course research. Sociology 35, 413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134619

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation: Revised and Expanded from Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldana, J. (2020). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ministry of Education (2018). China’s Standards of English Language Ability (Report No.: GF0018-2018). Beijing: National Education Examinations Authority.

Morgan, B. (2004). Teacher identity as pedagogy: towards a field-internal conceptualization in bilingual and second language education. Biling. Educ. Bilingual. 7, 172–188. doi: 10.1080/13670050408667807

National Foreign Language Teaching Advisory Board under the Ministry of Education (2020). University English Teaching Guide. Beijing: Higher Education Press.

Paris, C., and Lung, P. (2008). Agency and child-centered practices in novice teachers: autonomy, efficacy, intentionality, and reflectivity. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 29, 253–268. doi: 10.1080/10901020802275302

Priestley, M., Biesta, G. J. J., and Robinson, S. (2013). “Teachers as agents of change: teacher agency and emerging models of curriculum,” in Reinventing the Curriculum: New Trends in Curriculum Policy and Practice, eds M. Priestley and G. Biesta (London: Bloomsbury Academic), 187–206. doi: 10.5040/9781472553195.ch-010

Richards, A. J. (2018). Perceptions of Non-Teaching Workload for Faculty in High Technology Baccalaureate Degree Programs (ProQuest No. 10976009). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. Ph.D. thesis. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri-Columbia.

Richards, J. C. (2021). Teacher, learner, and student-teacher identity in TESOL. RELC J. 1–15. doi: 10.1177/0033688221991308

Ruan, X. L. (2019). Bridging the Rhetoric and the Reality: Towards an Understanding of Female EFL Teachers’ Professional Agency at a University of SHANGHAI, P. R. China. Ph.D. thesi. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Studies University.

Sun, Y. (2019). Ten relations between English major and professional English. J. Beijing Int. Stud. Univ. 3, 17–30.

Tao, L., and Gu, P. Y. (2016). Selection and compensation: a study on university EFL teachers’ professional agency. Foreign Lang. World 172, 87–95.

Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., and Vanroelen, C. (2014). Burnout among senior teachers: investigating the role of workload and interpersonal relationships at work. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.005

Keywords: agency competence, agency disposition, EFL-speaking instructors, identity commitment, professional agency

Citation: Wang L and Lam R (2022) University Instructors’ Enactment of Professional Agency in Teaching Spoken English as a Foreign Language. Front. Educ. 7:909048. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.909048

Received: 31 March 2022; Accepted: 23 May 2022;

Published: 09 June 2022.

Edited by:

Slamet Setiawan, Universitas Negeri Surabaya, IndonesiaCopyright © 2022 Wang and Lam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lan Wang, bmFuY3l3YW5nQGxpZmUuaGtidS5lZHUuaGs=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lan Wang

Lan Wang Ricky Lam

Ricky Lam