94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 01 July 2022

Sec. Digital Learning Innovations

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.901060

Reading picture books in the first language (L1) before rereading them in the second language (L2) is assumed to be beneficial for young dual language learners (DLLs). This pilot study examined how sharing digital picture books in L1 or L2 at home before reading them in L2 in kindergarten affected L2 book-specific vocabulary learning and story comprehension. Participants were 14 three- and four-year-old children who spoke Polish at home and learned Norwegian as their second language. Even when DLLs were less advanced in L2, reading first in L1 was not advantageous for L2 vocabulary learning. Characteristics of caregiver–child interactions during the reading of digital picture books in L2 may explain why home reading in L2 was more beneficial than reading in L1 for less proficient young L2 learners.

Picture book reading is a powerful means of exposing children to complex language. According to Logan et al. (2019), even minor changes in reading frequency result in substantial differences in language input. Moreover, the vocabulary in books tends to be more sophisticated than that used in everyday speech (Montag et al., 2015). Hence, picture book reading is an effective method of stimulating language and literacy development (Dickinson and Morse, 2019), and can be successfully used with young dual language learners (DLLs), that is children who learn a second language (L2) while still being in the process of first language (L1) acquisition (Fitton et al., 2018).

To succeed academically, young DLLs need to become proficient in the language of school instruction (August and Shanahan, 2006). However, many are exposed to their L2 predominantly in a kindergarten setting, while speaking only their native language at home. Although developing and maintaining L1 has multiple advantages, many of which go beyond the domain of language and literacy (Baker and Wright, 2017), in this study, we explored how children’s knowledge of L1 may be employed to support L2 learning.

We investigated whether reading picture books at home, in the child’s L1, before rereading them in L2 kindergarten is more helpful than reading in L2 at home or in kindergarten only. Presenting books in L1 before reading them in L2, a practice recommended in the early childhood teacher education literature (Høigård, 2013; Gillanders et al., 2014), is assumed to support story comprehension in DLLs at early stages of L2 acquisition and, consequently, it may facilitate L2 word learning. Yet there is little evidence to confirm the effectiveness of this approach. Focusing on three- and four-year-old Polish-speaking children learning Norwegian as their second language, we compared reading digital picture books in L1 and L2 at home, combined with reading in L2 in kindergarten. Our main aim was to test the effects of reading in Polish at home on Norwegian vocabulary learning and story comprehension, as compared to reading only in Norwegian.

Picture book stories are told through verbal narration and illustrations (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006), which in the digital format are occasionally enhanced with multimedia features, such as animations and sounds. Children construct meaning from all these information resources (Sipe, 2008; Christ et al., 2019), making use of their narrative as well as linguistic skills, particularly vocabulary knowledge (Sénéchal et al., 2006; Babayiğit, 2014). When DLLs are just starting to learn L2, they might benefit from listening to the verbal narration of the stories in their L1 beforehand. Repeatedly hearing and understanding the story in L1 may result in greater contextual support for inferring meanings of L2 words and phrases when the same book is later read in L2.

The linguistic interdependence hypothesis (Cummins, 1981a,2000) assumes that L1 and L2 acquisition is mutually dependent due to an underlying proficiency shared by both languages. Thus, the development of conceptual knowledge—the understanding of ideas and meanings attributed to words—in L1, facilitates its subsequent development in L2. This means that concepts acquired in L1 are not relearned in L2, but rather linked to new lexical labels. Therefore, presenting DLLs with words and concepts during book-reading in L1 might help them learn new words when rereading the book in L2 since the children would be connecting new lexical labels to familiar concepts. The contextual support created by understanding the story first read in L1 may also facilitate L2 vocabulary learning (Hammer et al., 2014).

According to the revised hierarchical model (Kroll and Stewart, 1994), L1-dominant bilinguals have weaker links between concepts and L2 words, which means that they rely on L1 mediation to access the concepts. However, as they become more proficient in L2, learners can retrieve conceptual information directly from the L2 lexicon. Yet this shift does not occur until learners have practiced L2 for at least two years. Cummins (1981b) also discussed the two-year mark, suggesting that it takes children approximately this long to achieve basic proficiency in L2. We expected, therefore, that children at early stages of L2 acquisition would be more likely to benefit from encountering books in L1 before reading them in their L2.

Only few published studies have evaluated the effect of reading picture books in L1 before rereading them in L2, with mixed results. Roberts (2008) examined how the language used when reading at home—L1 or L2—affected Hmong- and Spanish-speaking four-year-old children’s receptive vocabulary in English. In one experiment, home reading in L1 was more effective than reading only in English, though these findings were not replicated in a subsequent experiment.

In a more recent study from Norway, Grøver et al. (2020) conducted a shared reading intervention with a large group of four- and five-year-old DLLs speaking a variety of first languages. One component of the intervention involved sharing a few titles—mostly wordless picture books—in families’ preferred language at home, in addition to reading them in Norwegian in kindergarten. However, the effects of this procedure on L2 vocabulary were not statistically significant (p = 0.087).

This study compared reading in L1 and L2 with reading in L2 only, either exclusively in kindergarten or in combination with L2 reading at home. Well-designed digital picture books for young children are effective for enhancing children’s vocabulary and story comprehension, even outperforming print books (Furenes et al., 2021). Thanks to built-in language options of audio narration, digital picture books also allow DLLs to access stories in their L2 at home, even when parents who wish to read in that language are reluctant to do so, for example due to their own limited proficiency (Luo et al., 2020). According to Gunnerud et al. (2018), young DLLs whose families communicate predominantly in their L1 have lower comprehension skills in Norwegian than children exposed at home to Norwegian as well as another language. Thus, digital picture books may provide this group with additional, high-quality exposure to their L2 outside of kindergarten.

Over the last two decades, Norway has witnessed a large influx of Polish migrant workers, many of whom have settled there permanently with their families. Polish immigrants, who are currently the largest immigrant group in Norway (Steinkellner and Gulbrandsen, 2021), typically have strong ties with their home country, tend to speak Polish at home and own children’s books mainly in their native language (Rydland and Grøver, 2020). Thus, DLLs of Polish origin may benefit from having home access to digital picture books in Norwegian. At the same time, we anticipated that parents and children in this study might use Polish while sharing books in Norwegian, thus reducing the difference between reading in L1 and L2. Research on bilingual approaches to vocabulary instruction, such as bridging, which involves providing word definitions in L1 embedded in L2 book reading, shows that this may have positive effects on L2 word learning (Lugo-Neris et al., 2010; Leacox and Jackson, 2014; Méndez et al., 2015; Wood et al., 2018). Therefore, verbal exchanges in L1 combined with audio narration in L2 may, in fact, support L2 vocabulary learning.

Moreover, allowing DLLs to interact with a digital picture book in their L2 with an adult at home before reading it in a group setting might be more beneficial than having them read these books exclusively in kindergarten. The digital picture book format may elicit physical responses, such as pointing or tapping the touch screen, which may draw the children’s attention away from the narration and the teacher’s discussion of the story shared in a group (Hoel and Tønnessen, 2019; Hoel and Jernes, 2020). As a result, having the opportunity to read the book in L2 at home might give DLLs an advantage compared to reading the story only in kindergarten with other children.

In the current study, we tested whether (1) reading digital picture books in L1 at home and in L2 in kindergarten benefits DLLs’ story comprehension and L2 book-specific vocabulary learning, compared to reading in L2 only. However, the parent–child interaction in L1 while reading the stories in L2 might make reading in L1 and L2 at home more alike. We also tested whether (2) reading digital picture books in L2 at home benefits story comprehension and L2 book-specific vocabulary, compared to when books are only read in kindergarten.

We recruited participants from eight kindergartens (12 classrooms) with a high number of Polish-speaking children, located in an urban municipality in Western Norway. We focused on typically developing DLLs aged 33–51 months who had attended kindergarten for at least 12 months. Once the kindergarten administration and teachers agreed to participate and identified eligible children, consent forms were distributed to parents of 21 DLLs, and the parents of 18 children returned them signed.

National kindergarten closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic affected both the number of participants and the age at which they were evaluated. Three of the originally recruited children did not return to kindergarten when it reopened, while one refused to participate in testing. The age of the 14 children (6 girls, 8 boys) included in the study ranged from 42 to 54 months (M = 48.7, SD = 4.3). The participants had attended kindergarten for 16 to 40 months (M = 29, SD = 8.1), 6 to 9 h a day (M = 7.3, SD = 0.8). Background information about the participants was collected in a short, structured interview, conducted in Polish by the first author in person or, in two cases, online. Based on parental responses in the interview, all 14 children used Polish as the main language of communication with both parents at home. One participant communicated with one of the parents in English in addition to Polish. The children’s use of Norwegian at home was limited, as was their exposure to Norwegian outside of kindergarten. Most of the children were additionally exposed to Polish through contacts with family and friends in Norway and Poland, other children or staff in kindergarten, as well as Polish media. Maternal education varied, but seven mothers had completed secondary education, and four held a university degree.

In the study, we used a within-subjects experimental design. Before the intervention, we tested the children’s knowledge of book-specific vocabulary in Norwegian, which was tested again after the intervention, together with story comprehension. Each child participated in all three conditions:

(1) two readings of a digital picture book in Polish at home followed by two readings of the same book in Norwegian in kindergarten,

(2) two readings of a digital picture book in Norwegian at home followed by two readings of the same book in Norwegian in kindergarten,

(3) four readings of a digital picture book in Norwegian only in kindergarten.

The within-subject design entails a book change from one condition to the other. We combined the three conditions with three different books to ensure that condition and book were not confounded. Table 1 summarises the six possible combinations of book and condition. We randomly assigned these six combinations to the 14 participants. As we failed to make the number of participants a multiple of six, we did not use each book as often in each condition. Four combinations in Table 1 contained two children each, while two combinations involved three children. As a result of this imbalance, book A was read more often in Norwegian at home.

The Norwegian Centre for Research Data, a government-owned ethical supervisory agency in Norway, approved the study. The children’s teachers and parents received information about the study aims and their right to withdraw at any time without providing a reason. The consent forms distributed to the parents were written in Polish and Norwegian. The children also received oral information about the study and participated voluntarily.

A series of three commercially available digital picture books were used in the study: (A) Unni og Gunni reiser [Unni and Gunni travel], (B) Unni og Gunni malar [Unni and Gunni paint] and (C) Unni og Gunni gjer det fint [Unni og Gunni make it nice] (Folkestad, 2014a, b,c). In agreement with the author and publisher, the books were professionally translated from Norwegian to Polish and an audio recording of the Polish narration was added to each story. The books in Polish and Norwegian looked identical and had the same functionalities, such as 42–45 hotspots with animations and sound effects concealed in the illustrations. All three books include the same characters, have a similar length (131, 122, and 145 words, respectively, in their Norwegian versions), and share the same narrative structure. The books are therefore comparable with one another.

Furthermore, the stories are humorous, use repetition, and follow a simple storyline, which makes them suitable for children aged three to four (Christensen, 2010). The plot of the narratives is centred around a problem and its solution. For example, in Unni og Gunni gjer det fint, the two penguin-like characters realise that their house is empty and decide to furnish and decorate it. Moreover, the stories are partly told through illustrations that include elements not mentioned in the verbal text, such as scarves and eggs in Unni og Gunni gjer det fint (see Figure 1), which adds some complexity to the narratives.

Figure 1. The first and last screen in Unni og Gunni gjer det fint (2014). Reproduced with permission from Anna R. Folkestad and Det Norske Samlaget. The text reads: First screen: Unni and Gunni are looking at each other. “It is in a way a bit empty here,” Unni says. “Right,” Gunni says. Last screen: “We have such a nice home,” Gunni says. “Right,” Unni says.

The participating children’s parents received an iPad with access to two books, one in Polish and one in Norwegian. None of the families had prior experience with digital picture books. We instructed the parents to share both stories twice with their child as if they were print books but with audio narration turned on, both when the book language was Polish and Norwegian (Dore et al., 2018). The caregivers received text messages reminding them of the scheduled readings. They were also asked to record the last reading of each book using a voice recorder. Except for one parent who did not agree to record home readings, all caregivers recorded their reading sessions.

Similarly, teachers of the participating children received an iPad with all three digital picture books in Norwegian. They shared the stories with small groups, including the participant(s), according to a reading schedule. We instructed the teachers to use the audio narration and engage the group in a dialogue about the stories. Since only three out of 12 teachers had prior experience with digital picture books, all teachers were encouraged to practice with other books on the iPad, over one to two weeks preceding the scheduled readings. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, four children participated in readings carried out by other staff members, instructed by the teacher.

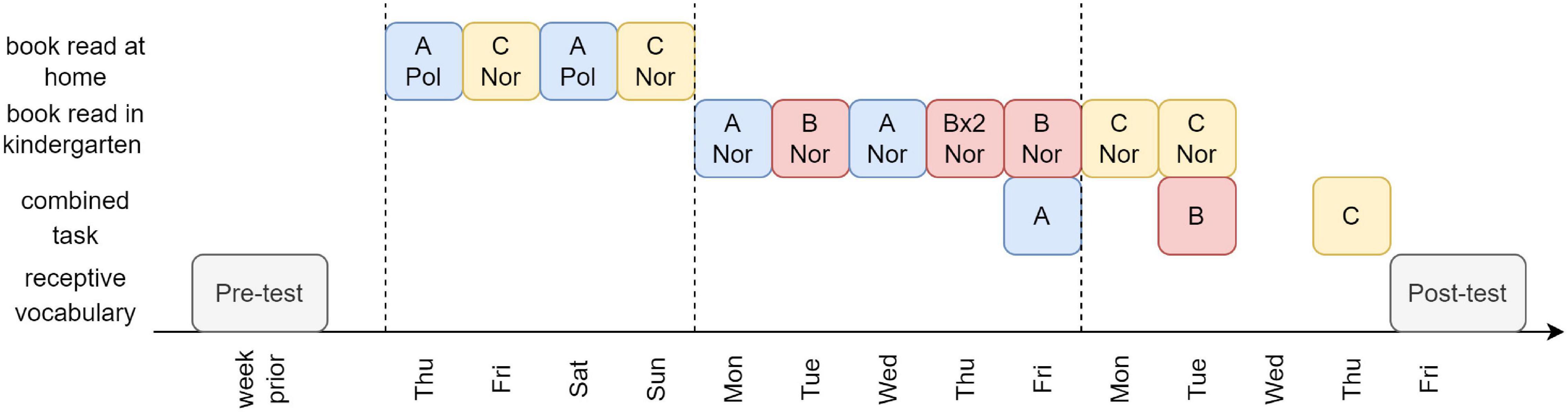

The two books shared at home were read over four days immediately preceding their reading in kindergarten, alternating between the book in Polish and Norwegian. The order of reading in kindergarten was the same for all participants, meaning that it was counterbalanced across conditions. Reading in kindergarten took place over six to seven consecutive working days, with one or two readings per day. Each book was shared four times in total. An example of a reading schedule for home and kindergarten is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of a book-reading and testing schedule. “Combined task” refers to the combined story comprehension and expressive vocabulary task.

The first author conducted all testing in a quiet part of the kindergarten area. Pre-testing took place in the week preceding the scheduled home reading. Combined post-testing of story comprehension and expressive book-specific vocabulary was conducted over three sessions, after completing the scheduled readings of each book (see Figure 2). The language of testing was Norwegian. However, since we consider story comprehension to be language-independent (Bohnacker, 2016; Rodina, 2017; Otwinowska et al., 2018), the children were allowed to express their understanding of the stories in Polish. By acknowledging the children’s bilingual competence, we wanted to avoid that they would refrain from answering due to insufficient expressive skills in Norwegian. Two of the 14 participants failed to take the receptive vocabulary post-test and one did not take the final comprehension and expressive vocabulary test.

To indicate the children’s language skills in Polish and Norwegian, parents and teachers received identical, researcher-developed questionnaires, which parents completed based on their children’s knowledge of Polish, while teachers did so based on children’s knowledge of Norwegian. The questionnaires contained nine statements about the children’s language use and comprehension (see Appendix A). The internal consistency of the 5-point Likert scale for Polish items was acceptable (α = 0.70), while that of Norwegian-language items was excellent (α = 0.92). Another—and primary—indicator of the children’s proficiency in Norwegian was the duration of their kindergarten attendance, which has been found to relate to L2 vocabulary skills in DLLs (Rydland and Grøver, 2020).

In a structured interview, parents estimated the number of children’s books they had at home and the frequency of reading with their children. Likewise, teachers reported the frequency of book reading activities in the participants’ kindergarten classrooms. Teachers also answered three questions about the participating children’s frequency of reading in kindergarten and engagement in reading activities, each of which was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (see Appendix A).

We assessed the children’s knowledge of book-specific receptive vocabulary in Norwegian using a researcher-developed, screen-based task. It included ten target words of different parts of speech and phrases unique to each book (30 in total), selected based on their subjective age of acquisition and usage frequency in Norwegian (Lind et al., 2015), which was medium for most test items included in the Norwegian Words lexical database. Medium subjective age of acquisition means that adult native speakers of Norwegian indicated having learned a given word when they were between 43 and 90 months old. Medium usage frequency indicates that a word is not among the 25% most frequent and the 25% least frequent words in the Norwegian language. Two of the 30 test words were lexical cognates sharing meaning with Polish, i.e., kompass (kompas) – compass, and lande (lądować) – to land.

Additionally, 35 preselected items were piloted with a group of 11 four- and five-year-olds speaking Norwegian as their L1. Based on the piloting results, five of the most frequently recognised items were excluded from the final version of the task. On each screen, there were four images to choose from: one representing the target word or phrase, and three foils. All the images were different from those in the books. The child was asked to point at the picture corresponding to the word or phrase read by the researcher (for example: “Can you show me the flying carpet?”, “Who is mixing something?”). The pre-test and post-test included the same targets and foils presented in different positions on the screen.

Story comprehension and book-specific expressive vocabulary were assessed using a combined task (see Appendix B), administered while going through the digital picture books with the sound turned off. Ten comprehension questions were adapted from the prompted comprehension task (Paris and Paris, 2003) and asked while the children looked at corresponding pictures in the books. Six questions were explicit, involving characters, setting, initiating event, problem, attempt to solve the problem, and outcome resolution. The remaining four were implicit comprehension questions about feelings, causal inference, dialogue, and prediction. To make the task suitable for three- and four-year-olds, we included prompts in the form of an alternative question, a yes/no question, or sentence completion. The examiner could use these to elicit an answer when the child had difficulty answering the original question. Each prompt could be used twice. The implicit question about the theme of the book, used by Paris and Paris (2003), was perceived as too demanding for children this age, and not used in this study.

The items in the expressive vocabulary task were the same as those in the receptive vocabulary task, except for two items per book which were excluded due to discrepancies between the word forms used in the book and the Norwegian dialect in the area where the children lived. Similar to prior studies of vocabulary learning from digital books (e.g., Smeets and Bus, 2012), we asked the children to complete sentences with target words. When the children produced target words in Polish, they were encouraged to say them in Norwegian. The combined task was piloted with a group of 14 three- and four-year-olds speaking Norwegian as their L1 or L2 and refined based on the piloting results.

All test sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed by the first author, and coded by two independent coders, one of whom was proficient in Polish in addition to Norwegian. As a rule, appropriate answers to the original questions in the story comprehension task were given a score of two, while a score of one was assigned where children needed additions prompts. The intraclass correlation coefficients for the story comprehension and expressive vocabulary components were 0.81 (95% CI 0.64–0.90) and 0.92 (95% CI 0.86–0.96), respectively. All differences in coding were resolved through discussion. Scores for the eight vocabulary items assessed in both the receptive and expressive vocabulary tasks were then combined for analysis. An item received two points if the child knew the word both receptively and expressively, and one point if the child only knew the word in one of these cases.

We also assessed the home readings of digital picture books with audio narration in Polish and Norwegian. The first author transcribed all the parents’ audio recordings and coded them for content-related utterances (about the illustrations, narration, animations, and sounds). For example, when reading Unni og Gunni gjer det fint in Norwegian, a mother commented in Polish on the first screen (see Figure 1): “Chyba jakiś szalik robią na drutach, widzisz?” (“I think they are knitting a scarf, you see?” – content-related utterance about illustration). The recordings were also coded for the use of individual words or phrases from the narration, in Norwegian and Polish. For example, in a reading of Unni og Gunni reiser, the narrator used the word redningsvestar (lifejackets) in Norwegian. Following that, a mother said: “Redningvester! Zobacz. Mają kamizelki ratunkowe.” (“Redningsvester! Look. They have lifejackets” –individual word from the narration used in Polish).

In line with our hypotheses, we tested two contrasts: reading in L1 vs. L2 (Polish at home vs. Norwegian at home and in kindergarten) and reading in L2 at home and in kindergarten vs. only in kindergarten (Norwegian at home vs. Norwegian in kindergarten). We intended to perform analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) with the number of months in kindergarten as a covariate. Two missing data points in the expressive vocabulary and story comprehension tasks were imputed using mean scores per book. Missing scores in the receptive vocabulary post-test were imputed by adding mean differences between the pre-test and post-test scores per book to the children’s pre-test scores. The expressive vocabulary scores by condition were not normally distributed, as assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p < 0.05), and the results approached a floor effect. We then decided to combine both vocabulary scores, expressive and receptive, and analyse them jointly. The scores on the joint test were normally distributed.

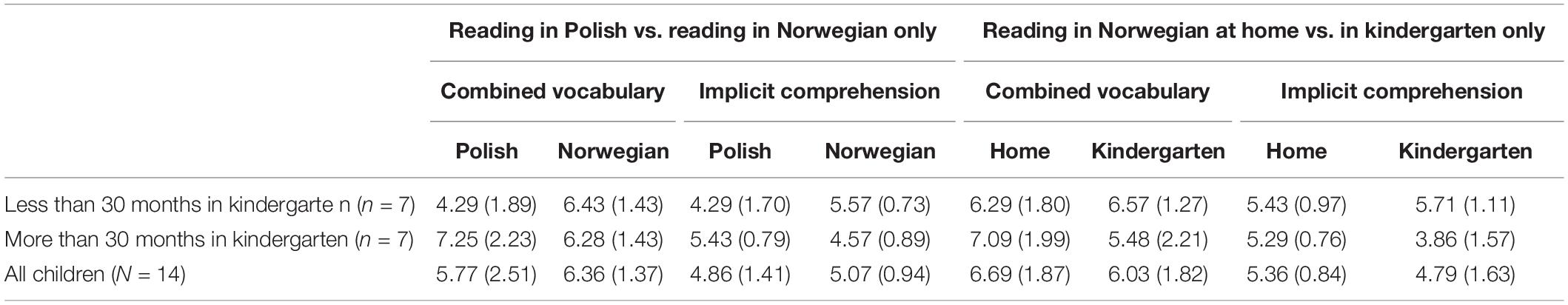

We could not perform ANCOVAs with the number of months in kindergarten as a covariate because the assumption of the homogeneity of regression slopes was not met. Instead, we conducted two repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with a median split of the number of months in kindergarten as a between-subjects factor. Seven children had attended kindergarten for less than 30 months (16–29), and seven for 30 months or longer (32–40) (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations). To obtain a more fine-grained picture of the children’s story comprehension, we separated the scores of implicit and explicit comprehension questions and ran two repeated-measures ANOVAs.

Table 2. Indicators of the participating children’s skills in Polish and Norwegian (means and standard deviations).

Table 2 presents an overview of different measures of the participants’ skills in Polish and Norwegian. Typically, parents evaluated their children’s knowledge of Polish as good, with average scores ranging from 3.6 to 5 points on a 5-point Likert scale. There was greater variation in the participants’ Norwegian skills as evaluated by their teachers, with average scores of 2.1 to 4.9 points. Still, most children (71%) received more than 3.5 points. The pre-test receptive vocabulary scores were also rather high: the participants recognised 30–63% of the selected words and phrases from the books (M = 12.9, SD = 2.8). The teachers’ evaluation correlated strongly both with the children’s pre-test scores, r = 0.72 (p = 0.003, two-tailed), and with the number of months the children had attended kindergarten, r = 0.57 (p = 0.034, two-tailed).

Parents estimated that they had 10 to 60 print children’s books at home (M = 37.9, SD = 15). Half of the caregivers reported reading with their children daily, five parents did so four to six times a week, and two did so once to three times a week. All caregivers read with their children mostly in Polish. Five out of 12 kindergarten teachers reported reading daily or almost daily in their classrooms, six did so once to three times a week, and one reported little reading. Most children participated relatively often in reading in kindergarten (M = 4.1, SD = 0.7). The teachers reported that participants enjoyed book reading (M = 4.1, SD = 0.8), but did not tend to ask questions about the books (M = 2.4, SD = 1.1).

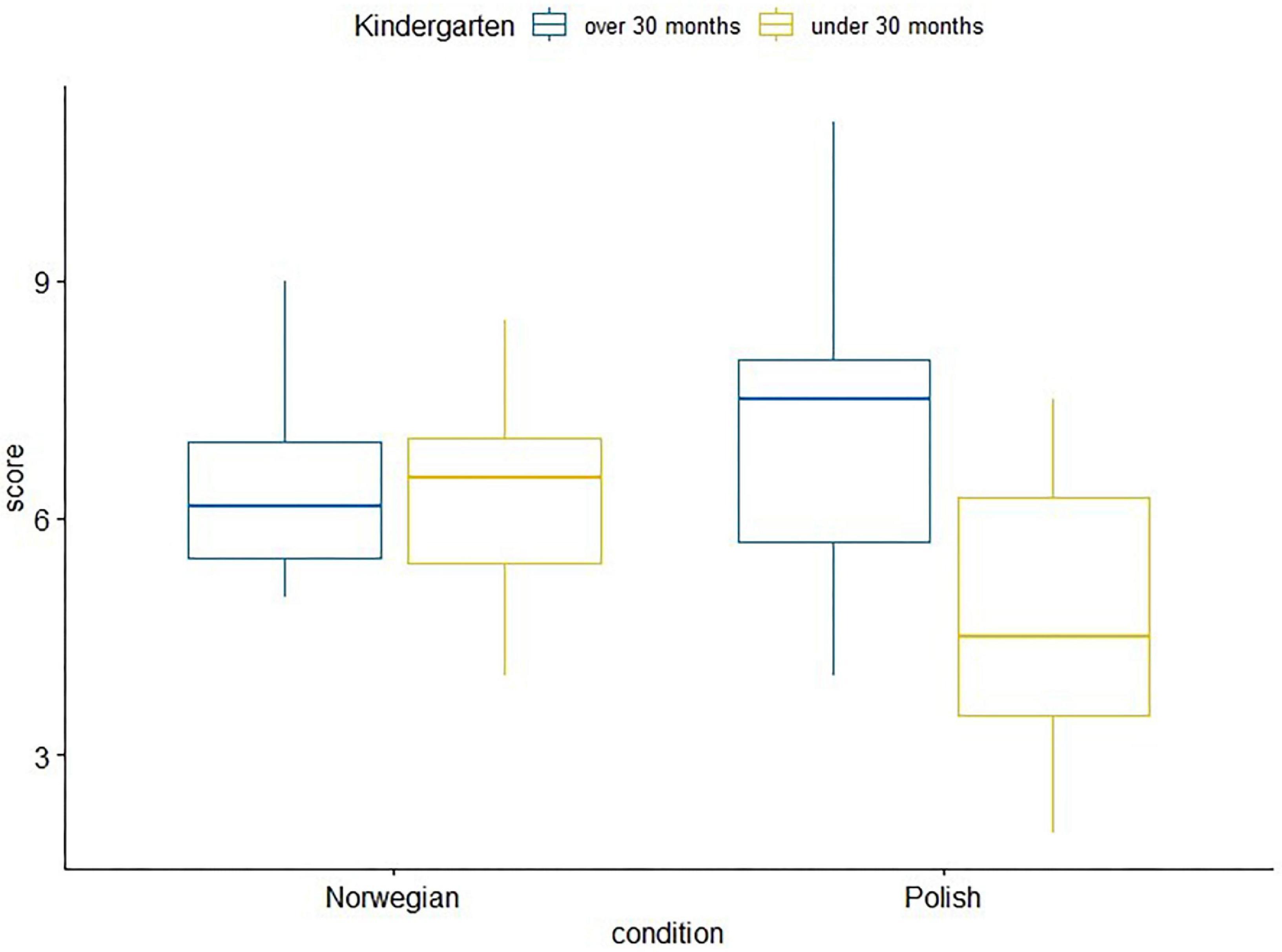

Combined scores for receptive and expressive book-specific vocabulary were normally distributed, with no outliers. The analysis revealed no main effect of reading in L1 at home or time in kindergarten. However, there was a significant interaction between the contrast between reading in L1 at home and time in kindergarten, F(1,12) = 16.86, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.584. As shown in Figure 3, in the group of children who had attended kindergarten for less than 30 months, reading in Norwegian outperformed reading in Polish (p = 0.001). There were no significant differences between the conditions in the group that had attended kindergarten for more than 30 months.

Figure 3. Box plots of the combined vocabulary scores for the story read only in Norwegian versus in Polish first, coloured by time in kindergarten. Maximum score possible = 16.

We analysed explicit and implicit comprehension questions separately. The scores for explicit comprehension were normally distributed and there were no outliers. The analysis revealed no significant differences between conditions for the six explicit comprehension questions, no difference between children attending kindergarten for more and less than 30 months, nor any interactions between conditions and time spent in kindergarten. The implicit comprehension scores per condition were normally distributed after Winsorizing one outlier in the condition where children heard the book in Norwegian at home. We found no significant effects of reading in L1 at home or time in kindergarten. However, the interaction between the contrast between reading in L1 vs. L2 and time in kindergarten was significant, F(1,12) = 8.11, p = 0.015, partial η2 = 0.403. As shown in Table 3, among children who had attended kindergarten for less than 30 months, the scores for reading only in Norwegian were higher (M = 5.6, SD = 0.7) than those obtained for reading in Polish first (M = 4.3, SD = 1.7). However, the difference only approached significance (p = 0.052).

Table 3. Mean scores (and standard deviations) for reading in Polish vs. reading only in Norwegian and for reading in Norwegian at home vs. reading in kindergarten only.

When children heard the books only in Norwegian, there was no significant difference in the combined vocabulary scores between reading in Norwegian both at home and in kindergarten versus in kindergarten only. Nor did we find an interaction between this contrast and time in kindergarten (p = 0.158). Outcomes for comprehension were similar whether we focused on explicit or implicit questions.

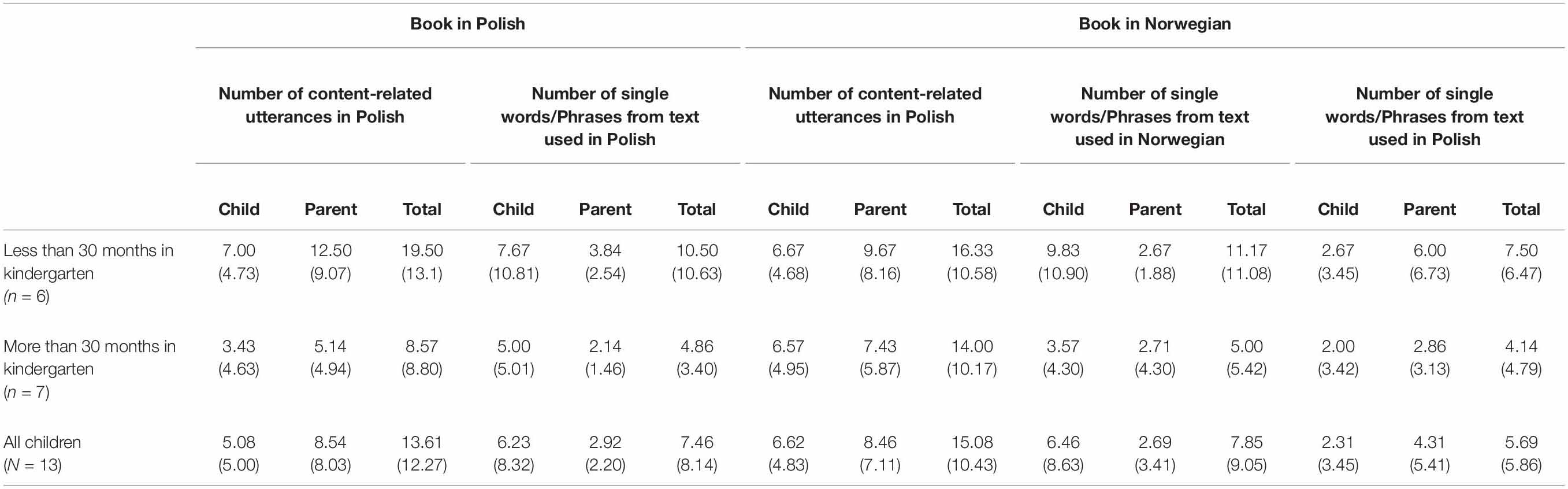

We examined the book reading sessions to see whether the expected difference between reading in L1 followed by reading in L2, and reading in L2 only, was reduced due to parents mainly commenting on the story in Polish when sharing the book with audio narration in Norwegian. An analysis of the audio recordings of home readings showed that Polish was the preferred language of communication, regardless of the book language. When sharing the books, parents and children produced a considerable number of content-related utterances in Polish, concerning illustration details and multimedia effects (see Table 4). Parents of children who had attended kindergarten for a shorter time used, on average, more single words and phrases from the Norwegian narration in Polish, either through direct translation or in spontaneous talk, than parents in the other group. Furthermore, children who had attended kindergarten for a shorter time repeated on average more single words and phrases after hearing them from the Norwegian narrator. They were also more likely to use these Norwegian words while speaking in Polish than the children who had been in kindergarten for a longer time. In this case, a similar pattern could be observed for the books read in Polish.

Table 4. Means (and standard deviations) of use of Polish and Norwegian during home readings of digital picture books in Polish and Norwegian.

We hypothesised that reading digital picture books in L1 at home before rereading them in L2 in kindergarten would be more beneficial for DLLs’ acquisition of book-specific L2 vocabulary and story comprehension, compared to reading only in L2. As suggested by Roberts (2008), we expected that reading the story in L1 before encountering it in L2 would ensure that children understand it better, which again would create more favourable conditions for learning new L2 words. However, we found that reading in L1 before rereading the same book in L2 was not helpful for DLLs who were less advanced in their L2. Conversely, these children benefited more from reading in L2. Four instead of two repetitions of the story in Norwegian may have contributed to the DLLs learning more Norwegian words. This is because multiple exposures are a known and important factor that supports vocabulary learning from book reading (Sénéchal, 1997; Horst et al., 2011).

Looking at verbal exchanges during home reading sessions, we found that parents and children provided comments and explanations in Polish, irrespective of the language of the audio narration. The verbal exchanges in Polish that accompanied the readings in Norwegian at home may also explain why the children who had attended kindergarten for a shorter time, and who we consider less proficient in L2, benefited more from hearing the story in L2 at home. Translating words and phrases into Polish, combined with listening to the audio narration in Norwegian, might have supported L2 word learning in the same way as bridging or other bilingual reading techniques (Lugo-Neris et al., 2010; Leacox and Jackson, 2014; Wood et al., 2018), possibly also increasing comprehension of the implicit information in the story. Furthermore, additional exposures to Norwegian words in form of repetitions after the narrator during the home readings may have contributed to L2 word learning (Flack et al., 2018).

Test scores of DLLs who had attended kindergarten for more than 30 months were not affected by the language of reading. These children may have been proficient enough in Norwegian to learn new words in L2 and understand the story even after hearing it only twice in Norwegian. This finding is in line with the theory that suggests a shift or a milestone occurring around two years into the L2 learning process (Cummins, 1981b; Kroll and Stewart, 1994). Moreover, the picture books were written in simple language, which is why they may have been relatively easy to understand for the participants when read in L2, particularly for children more proficient in Norwegian.

Our second hypothesis was that reading digital picture books in L2 at home before sharing them in kindergarten would be more advantageous than reading in kindergarten only. The hypothesis was not confirmed. We expected that reading digital picture books in L2 with an adult at home would allow DLLs to focus more on the story and thereby increase story comprehension and L2 vocabulary learning, compared to potentially more distracting reading with a group of kindergarten children. However, the participants obtained similar scores after sharing books in Norwegian, regardless of the reading setting. We can speculate that the characteristics of the caregiver–child talk, in combination with the children’s individual interaction with the book at home, might have provided comparable support for story comprehension and L2 word learning as the teachers’ explanations of single words or the storyline in the kindergarten setting, thus making the two reading conditions very similar.

Our study has several limitations, the first of them being the small sample size. Assuming a high effect size (f = 0.5), an alpha equal to 0.05 and a power equal to 0.80, a minimum of 18 children would be satisfactory for the current study design. Unfortunately, we lost recruited participants, mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, although the present study does not meet the criteria for a critical test of the hypotheses, it helps defining relevant conditions for further research.

Another limitation is the children’s overall rather high proficiency in L2, which may explain why they did not benefit from hearing the story in L1. It is illustrative that only a few participants were at a low level of L2 skills, as evaluated by their teachers, while all children identified at least 30% of the vocabulary items at pre-test. We need research that tests the effects in a group that is much less advanced in L2 than the current sample. Moreover, our choice of books was influenced by the assumption about the participants being at early stages of learning Norwegian, which prompted us to select simple stories with little verbal text. Children might have had more support from encountering the books in L1 if the story language and the narratives themselves had been more complex.

Furthermore, the study focused on Polish families in Norway who communicate in their native language and engage in regular reading with their children. Hence, our findings regarding language use during home reading are restricted to Polish DLLs with similar characteristics. Future research on reading in L1 and L2 should include participants from other immigrant groups to Norway or other countries, with different patterns of home language use and home literacy environments. It would also be interesting to investigate the effects of children’s independent reading of digital picture books, which we know is a relatively common practice (Dore et al., 2018).

Digital picture books offer new ways of employing reading to develop children’s second-language skills. Their built-in language options of audio narration enable DLLs to hear stories in the home language before encountering them again in L2. However, the results of the current study do not support this advantage—our findings showed unfavourable effects of reading books in L1 followed by rereading them in L2. On the contrary, children who were not yet advanced in L2 benefited from hearing stories in L2 at home, even though their caregivers normally would read with them in L1. In other words, DLLs at early stages of L2 acquisition may profit from another new possibility that digital picture books offer—having access to stories in L2 in homes where parents otherwise may be reluctant to read in that language, for example due to their own limited proficiency. In this way, digital picture books create opportunities for collaboration between kindergartens and families, which could provide DLLs speaking only L1 at home with greater exposure to rich vocabulary in their L2 (Gunnerud et al., 2018). Combining digital picture book reading in L2 with parental input in the home language might be a way of supporting children’s dual language learning.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

KT and AB contributed to the study design, development of the research instruments, analysis of the data, and writing of the manuscript. KT recruited the participants, supervised the intervention, and collected the data. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (grant number 275576 FILIORUM) and the University of Stavanger.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We express our gratitude to the participating children, their parents, teachers, kindergarten administration and other staff members involved in this project, for their engagement and positive attitude, despite the pandemic restrictions. KT would like to thank Trude Hoel for her continuous support and effort put into coding, Anna R. Folkestad and Samlaget for allowing us to create new language versions of the digital picture books, Elisabeth Brekke Stangeland for assistance in questionnaire development, as well as Oliwia Szymańska for great help with coding.

August, D. E., and Shanahan, T. E. (2006). Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Hoboken, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Babayiğit, S. (2014). The role of oral language skills in reading and listening comprehension of text: a comparison of monolingual (L1) and bilingual (L2) speakers of English language. J. Res. Read. 37, S22–S47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9817.2012.01538.x

Baker, C., and Wright, W. E. (2017). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 6th Edn. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bohnacker, U. (2016). Tell me a story in English or Swedish: narrative production and comprehension in bilingual preschoolers and first graders. Appl. Psycholing. 37, 19–48. doi: 10.1017/S0142716415000405

Christ, T., Wang, X. C., Chiu, M. M., and Cho, H. (2019). Kindergartener’s meaning making with multimodal app books: the relations amongst reader characteristics, app book characteristics, and comprehension outcomes. Early Child. Res. Quart. 47, 357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.01.003

Christensen, N. (2010). Fiktion for begyndere: narrative forløb og karakterer i nordiske billedbøger for små børn. [Fiction for Beginners: narrative Progression and Characters in Nordic Picture Books for Small Children]. Nord. J. Childlit. Aesth. 1:5627. doi: 10.3402/blft.v1i0.5627

Cummins, J. (1981a). Empirical and theoretical underpinnings of bilingual education. J. Educ. 163, 16–29.

Cummins, J. (1981b). “The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students,” in Schooling and Language Minority Students, ed. A Theoretical Framework California State Department of Education (Los Angeles, CA: California State Department of Education), 3–50.

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Dickinson, D. K., and Morse, A. B. (2019). Connecting through Talk: Nurturing Children’s Development with Language. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company.

Dore, R. A., Hassinger-Das, B., Brezack, N., Valladaresd, T. L., Pallera, A., Vu, L., et al. (2018). The parent advantage in fostering children’s e-book comprehension. Early Child. Res. Quart. 44, 24–33.

Espenakk, U., Frost, J., Færevaag, M. K., Horn, E., Løge, I. K., Solheim, R. G., et al. (2011). TRAS: Observasjon av språk i daglig samspill [TRAS: Observation of language in daily interaction]. Stavanger: Nasjonalt senter for leseopplæring og leseforskning.

Fitton, L., McIlraith, A. L., and Wood, C. L. (2018). Shared book reading interventions with english learners: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 712–751. doi: 10.3102/0034654318790909

Flack, Z. M., Field, A. P., and Horst, J. S. (2018). The effects of shared storybook reading on word learning: a meta-analysis. Dev. Psych. 54, 1334–1346. doi: 10.1037/dev0000512

Furenes, M. I., Kucirkova, N., and Bus, A. G. (2021). A comparison of children’s reading on paper versus screen: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 91, 483–517. doi: 10.3102/0034654321998074

Gillanders, C., Castro, D. C., and Franco, X. (2014). Learning words for life. Read. Teacher 68, 213–221. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1291

Grøver, V., Rydland, V., Gustafsson, J.-E., and Snow, C. E. (2020). Shared book reading in preschool supports bilingual children’s second-language learning: a cluster-randomized trial. Child Dev. 91, 2192–2210. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13348

Gunnerud, H. L., Reikerås, E., and Dahle, A. E. (2018). The influence of home language on dual language toddlers’ comprehension in Norwegian. Europ. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 26, 833–854. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533704

Hammer, C. S., Hoff, E., Uchikoshi, Y., Gillanders, C., Castro, D., Sandilos, L. E., et al. (2014). The language and literacy development of young dual language learners: a critical review. Early Child. Res. Quart. 29, 715–733.

Hoel, T., and Jernes, M. (2020). Samtalebasert lesing av bildebok-apper: barnehagelærer versus hotspoter. [Dialog-Based Reading of Picture Book Apps: Kindergarten Teacher versus Hotspots]. Norsk Ped. Tids 104, 121–133.

Hoel, T., and Tønnessen, E. S. (2019). Organizing shared digital reading in groups: optimizing the affordances of text and medium. AERA Open 5, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2332858419883822

Høigård, A. (2013). Barns språkutvikling: muntlig og skriftlig. [Children’s Language Development: Oral and Written]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Horst, J. S., Parsons, K. L., and Bryan, N. M. (2011). Get the story straight: contextual repetition promotes word learning from storybooks. Front. Psych. 2:17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00017

Kroll, J. F., and Stewart, E. (1994). Category interference in translation and picture naming: evidence for asymmetric connection between bilingual memory representations. J. Memory Lang. 33, 149–174. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1994.1008

Leacox, L., and Jackson, C. W. (2014). Spanish vocabulary-bridging technology-enhanced instruction for young English language learners’ word learning. J. Early Child. Literacy 14, 175–197. doi: 10.1177/1468798412458518

Lind, M., Simonsen, H. G., Hansen, P., Holm, E., and Mevik, B. H. (2015). Norwegian words: a lexical database for clinicians and researchers. Clin. Ling. Phon. 29, 276–290. doi: 10.3109/02699206.2014.999952

Logan, J. A., Justice, L. M., Yumus, M., and Chaparro-Moreno, L. J. (2019). When children are not read to at home: the million word gap. J. Devel. Behav. Ped. 40, 383–386. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000657

Lugo-Neris, M. J., Jackson, C. W., and Goldstein, H. (2010). Facilitating vocabulary acquisition of young English language learners. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Schools 41, 314–327. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2009/07-0082)

Luo, R., Escobar, K., and Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2020). Heterogeneity in the trajectories of US Latine mothers’ dual-language input from infancy to preschool. First Lang. 40, 275–299. doi: 10.1177/0142723720915401

Méndez, L. I., Crais, E. R., Castro, D. C., and Kainz, K. (2015). A culturally and linguistically responsive vocabulary approach for young Latino dual language learners. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 58, 93–106. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-12-0221

Montag, J. L., Jones, M. N., and Smith, L. B. (2015). The words children hear: picture books and the statistics for language learning. Psych. Sci. 26, 1489–1496. doi: 10.1177/0956797615594361

Otwinowska, A., Mieszkowska, K., Białecka-Pikul, M., Opacki, M., and Haman, W. (2018). Retelling a model story improves the narratives of Polish-English bilingual children. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 23, 1083–1107.

Paris, A. H., and Paris, S. G. (2003). Assessing narrative comprehension in young children. Read. Res. Quart. 38, 36–76.

Roberts, T. A. (2008). Home storybook reading in primary or second language with preschool children: evidence of equal effectiveness for second-language vocabulary acquisition. Read. Res. Quart. 43, 103–130.

Rodina, Y. (2017). Narrative abilities of preschool bilingual Norwegian-Russian children. Intern. J. Biling 21, 617–635. doi: 10.1177/1367006916643528

Rydland, V., and Grøver, V. (2020). Language use, home literacy environment, and demography: predicting vocabulary skills among diverse young dual language learners in Norway. J. Child Lang. 48, 717–736. doi: 10.1017/S0305000920000495

Sénéchal, M. (1997). The differential effect of storybook reading on preschoolers’ acquisition of expressive and receptive vocabulary. J. Child Lang. 24, 123–138. doi: 10.1017/S0305000996003005

Sénéchal, M., Ouellette, G., and Rodney, D. (2006). “The misunderstood giant: on the predictive role of early vocabulary to future reading,” in Handbook of Early Literacy Research, eds D. K. Dickinson and S. B. Neuman (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 173–182.

Sipe, L. R. (2008). Storytime: Young Children’s Literary Understanding in the Classroom. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Smeets, D. J. H., and Bus, A. G. (2012). Interactive electronic storybooks for kindergartners to promote vocabulary growth. J. Exp. Child Psych. 112, 36–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.12.003

Steinkellner, A., and Gulbrandsen, F. B. (2021). Immigrants and Norwegian-born to Immigrant Parents at the beginning of 2021. Available online at: https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/immigrants-and-norwegian-born-to-immigrant-parents-at-the-beginning-of-2021 (accessed March 7, 2022)

Wood, C., Fitton, L., Petscher, Y., Rodriguez, E., Sunderman, G., and Lim, T. (2018). The effect of e-book vocabulary instruction on Spanish–English speaking children. J. Speech, Lang. Hearing Res. 61, 1945–1969.

Interview-based questionnaire about the child’s language comprehension and use, and reading in kindergarten (loosely adapted from Espenakk et al., 2011).

Part A – Evaluation of L1 skills by parent/L2 skills by kindergarten teacher.

To what degree do you agree with the following statements?

totally disagree – disagree – neither agree nor disagree – agree – totally agree.

1) The child understands well what is being said when you talk to them, for example, “Put the green book on the table.”

2) The child can name objects and actions, for example, “(This is) a jumper.” “(We are) eating fruit.”

3) The child uses words to express their wishes or feelings.

4) The child uses many varied words in L1/L2.

5) The child uses L1/L2 actively in longer conversations.

6) The child uses L1/L2 actively in play with others.

7) The child uses question words, such as how or why.

8) The child can describe (with assistance) events and experiences that have taken place, for example, what you did on a trip.

9) The child can follow and understand a story when they are read to.

Part B – Evaluation of the child’s engagement in reading, by kindergarten teacher.

10) The child participates often in reading.

11) The child likes reading books with an adult.

12) The child is active during reading, as evidenced by behaviours such as asking questions.

The combined comprehension and expressive vocabulary task.

Adapted from the prompted comprehension task by Paris and Paris (2003).

Keywords: dual language learners, second language learning, picture book reading, digital picture books, bilingualism, ECEC

Citation: Tunkiel KA and Bus AG (2022) Digital Picture Books for Young Dual Language Learners: Effects of Reading in the Second Language. Front. Educ. 7:901060. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.901060

Received: 21 March 2022; Accepted: 01 June 2022;

Published: 01 July 2022.

Edited by:

Adriel John Orena, Fraser Health, CanadaReviewed by:

Klaudia Krenca, Dalhousie University, CanadaCopyright © 2022 Tunkiel and Bus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katarzyna A. Tunkiel, a2F0YXJ6eW5hLmEudHVua2llbEB1aXMubm8=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.