- 1Endicott College, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

- 2The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Life-long learning is one of the educational topics in countries and regions in the East Asia region. Currently, many senior citizens decide to gain their English language proficiencies and skills after their retirement in Hong Kong SAR. Although Chinese and English are the official languages in Hong Kong SAR, many senior citizens cannot handle both languages due to their previous education and background. The purpose of this study is to understand the learning motivations and experiences of a group of senior citizens in Hong Kong, particularly with regard to using the blended learning mode as the means for instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic. With the coordination of adult learning centre, 40 participants who were taking a blended English-as-an-Additional Language course were joined the study. The online-based semi-structured interview and focus group activities were employed. In line with the social cognitive career and motivation theory and self-efficacy theory, the results indicated that: (1) achieve my personal goals, (2) I want to speak English as my additional language, and (3) life-long learning as my development, were the main themes. The results of this study provided some suggestions to programme managers, course leaders, school heads, and human resources planners for the directions in life-long learning and foreign language or additional language learning to senior citizens in the metropolitan regions.

Introduction

Traditionally, learning a foreign language or additional language is not uncommon for K-12 students, university students, and working professionals who want to upgrade their communication skills for career development. English is a popular foreign language or additional language in East Asian, and a number of learners choose to study it (Maican and Cocoradă, 2021). Also, to comply with governmental policies in the East Asian region, traditional-age students and university students need to complete a series of English language courses in order to graduate. Over the past few decades, different types of English language courses have been developed to meet the needs of learners seeking career development and organisations wanting to have skilled professionals and managers (Cho, 2012; Kim et al., 2014; DeWaelsche, 2015). A series of English for special purposes (ESP) courses have been created, such as English for business learners and the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) (Tayan, 2017). These ESP courses have filled the gaps in learners’ professional development, particularly their foreign language or additional language development.

However, learning should not be limited to traditional-age students and working professionals. Senior citizens and retirees also have the right to learn foreign languages or additional language and take professional development courses after their retirement (Taşçı and Titrek, 2019). Over the past few decades, the idea of life-long learning has become more widely adopted in private academies, university extension departments, and even secondary school environments. Many government departments and non-profit organisations sponsor senior citizens to enrol in different types of life-long learning courses and programmes. According to the Elder Academy in Hong Kong, in early 2007, the Hong Kong Labour and Welfare Bureau and the Elderly Commission established primary and secondary school-based programmes for senior citizens who want to gain qualifications. More importantly, after graduating from secondary school, some senior citizens want to continue their education at university level. Consequently, nearly 190 educational facilities in Hong Kong offer primary, secondary, and post-secondary courses and programmes (About Elder Academy, 2022).

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many lessons and programmes had to switch from the on-campus mode to online and blended learning styles in order to meet the recommendations of social distancing regulations and lockdown policies, regardless of the age, site, subject matter, and level of the learners (Iqbal and Sohail, 2021; Bai, 2022). In other words, some life-long learning courses and programmes had to be delivered online to meet government policies. However, many life-long learners and senior citizens may not have experience of online and blended learning. More importantly, some senior citizens do not have a computer or cellphone application (Shen and Liu, 2022). Therefore, the challenges and difficulties of online and blended learning for senior citizens are obvious.

Purpose of the study

The needs of life-long learners and senior citizens are usually neglected. Although these groups of learners only represent a small portion of the learner population, positive experiences and learning outcomes should be delivered as everyone should enjoy the same rights and the same level of quality education. The purpose of this study is to understand the learning motivations and experiences of a group of senior citizens in Hong Kong, particularly with regard to using the blended learning mode as the means for instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the theoretical frameworks, two research questions guided this study,

1) Why would senior citizens in Hong Kong decide to learn English as an additional language (EAL) after their retirement? What are their motivations?

2) How would senior citizens describe their learning experiences and sense-making processes in relation to a blended learning EAL course, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Significance of the study

Many of the current studies of online and blended learning courses focus on K-12 and university students and the relevant environments. However, there are research and practice gaps in the area of life-long learning and learning for senior citizens (Taşçı and Titrek, 2019). As life-long learning and senior citizens are important parts of educational communities, it is important to fill the gaps and answer their needs. The findings may provide some insights and references for leaders and curriculum developers in this area.

Theoretical frameworks and relevant literature

Social cognitive career and motivation theory

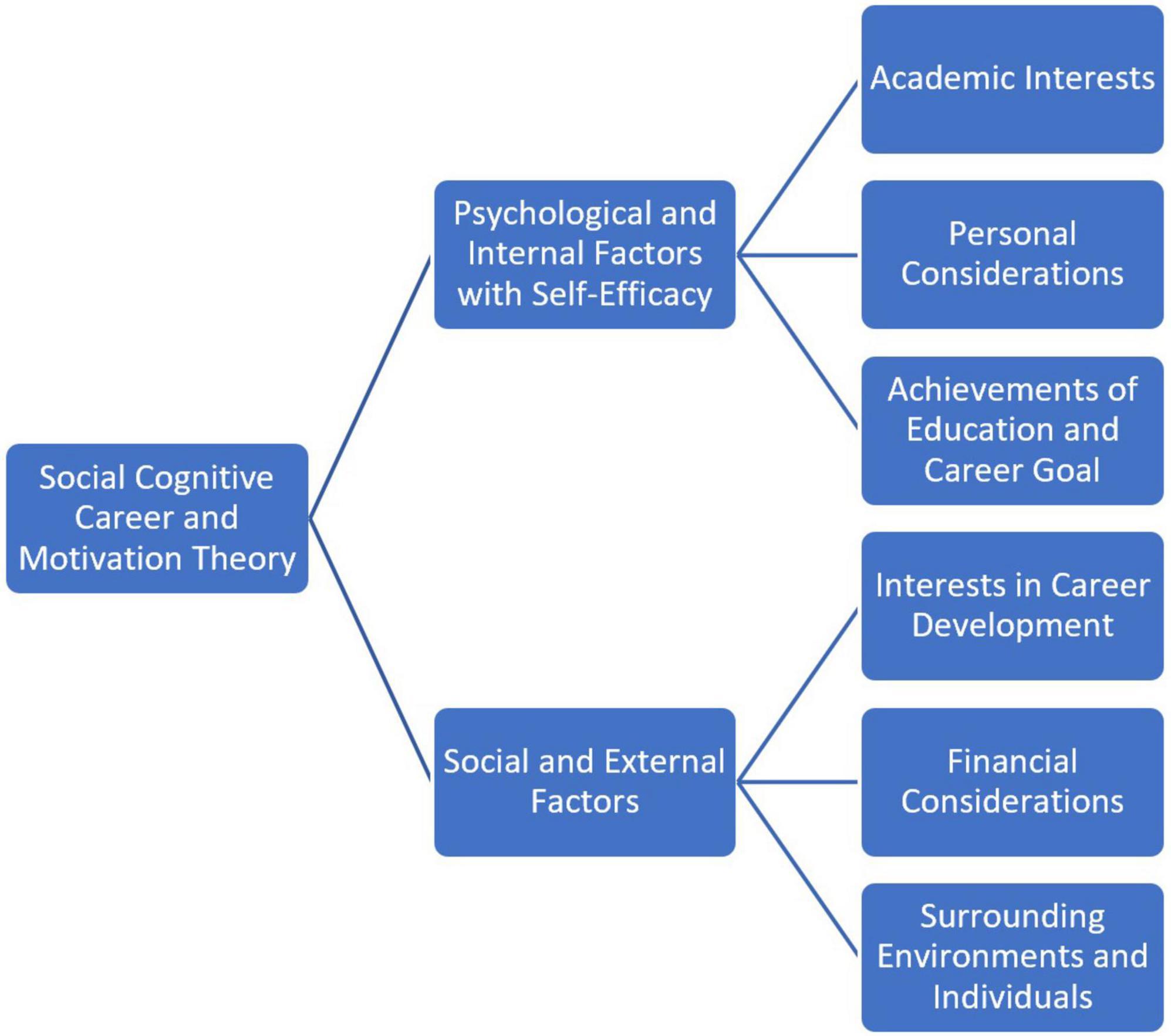

Social cognitive career and motivation theory (Dos Santos, 2021a) was developed from social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994; Lent and Brown, 1996) and self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1989, 1997). It argues that individuals’ and groups’ motivations can be influenced by internal and external factors. Two directions and six sub-directions are categorised in the framework of the theory.

The two directions are “psychological and internal factors with self-efficacy” and social and external factors. Psychological and internal factors with self-efficacy, including individuals’ academic interests, personal considerations, and achievement of education and career goals, have a significant influence over learners’ motivations and decision-making processes, and social and external factors, which include interest in career development, financial considerations, and surrounding environments and individuals, play a significant role in impacting motivations and decision-making processes from the social perspective (Dos Santos, 2021a). As for the theory, refer to Figure 1.

Over the past decade, some studies have been conducted in the fields of education and learning on the basis of the relevant theories. One study (Zacher et al., 2019) indicated that academic and career developments play a significant role in influencing an individual’s learning motivation; some of the participants in this study indicated that their gender, mentoring processes, intervention, and medicine could impact their learning motivation and decision-making processes (Kwee, 2021b).

Another recent study (Oga-Baldwin, 2019) indicated that individuals’ motivations and reasons for learning could be influenced by their engagement in acting, thinking, feeling, making, and collaborating in their language classroom environments. From the psychological perspective, scholars (Mercer, 2018) have argued that both teachers and students should have a sense of psychology and psychological teaching and learning preparation in order to provide and gain the expected outcomes and achievements in language classroom environments.

Some other scholars (Mandasari and Oktaviani, 2018) have argued that effective classroom management could significantly increase the motivation, learning outcomes, and experiences of students in English language classroom environments. As studies have focused on foreign language or additional language teaching and learning, the research gaps in relation to the application of social cognitive career and motivation theory to examine life-long learning and senior citizens have yet to be filled (Illeris, 2018). There is a demand for research and practical measures in this area.

Self-efficacy theory

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s self-determination and personal belief in their capacity and ability to execute the behaviours necessary to achieve their goals and performance targets (Bandura, 1989, 1997). It reflects an individual’s confidence in their ability to exert control over their own motivations, behaviours, and social contexts. In other words, if the individual has a strong belief in their ability to complete a job, the more likely it is that they will finish the job, and vice versa. In language teaching and learning, if a learner has a strong belief in their ability to complete their work and course, they are more likely to achieve their goals, regardless of the difficulties (Dos Santos, 2021b).

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many lessons, particularly language courses, have had to be taught online to meet social distancing recommendations from government departments (Meşe and Sevilen, 2021). Unlike traditional on-campus and classroom-based language courses, online and blended classroom environments, particularly in language classrooms, are unfamiliar to many teachers and learners (Gilboy et al., 2015).

Some students have expressed their confusion with regard to the completion of their online courses and programmes as they did not understand how to manage and balance their coursework and learning via online platforms (Brown et al., 2015). A recent study (Iqbal and Sohail, 2021) also indicated that students experienced challenges in regard to their clinical and face-to-face instruction due to the challenges of online learning and the limitations of online learning platforms. Such negative experiences and confusion have significantly impacted the self-efficacy and learning outcomes of learners internationally.

A recent study (Kim et al., 2021) argued that writing diaries in English and writing blogs on the internet could overcome some challenges and thus might increase the self-efficacy of English language learners. However, further studies should be conducted in order to understand the long-term impacts and the relationship between learners’ motivations and self-efficacy (Ma et al., 2021), particularly for life-long learners and senior citizens.

Materials and methods

Case study

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many private academies, schools, and universities in Hong Kong switched their on-campus and in-person courses and programmes to online-only or blended learning modes. Although some courses returned to the on-campus mode when the government cancelled the lockdown policies, some providers continued to offer online-only and blended learning courses to learners wanting to continue their learning via online platforms (Yin, 2012). Thus, purposive sampling (Merriam, 2009) was used to invite a group of senior citizens. All had decided to study EAL via a blended learning course offered by one of the private academies in Hong Kong.

Participants and recruitment

The researcher contacted the administrator of a private adult learning centre in Hong Kong for the study. The private adult learning centre administrator agreed and supported this study as life-long learning is one of the important topics in Hong Kong. The researcher forwarded the invitation letter, research protocol, and unsigned agreements to the administrators. The administrators forwarded the materials to the learners who joined the blended EAL course(s) during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the data collection duration, two EAL courses were available. As a result, 40 participants were willing to join the study and share their experiences. The participants should meet all the following points:

• Currently enrolled at a blended EAL course at a private adult learning centre in Hong Kong

• Senior citizens in Hong Kong

• Never completed online-only and blended learning courses before the current EAL course(s)

• Non-vulnerable person

• Willing to share their learning experiences.

Data collection

According to Seidman (2013), interview is a useful qualitative data collection tool. Interview is not uncommon for many qualitative researchers to collect in-depth data and stories from the participants, particularly the backgrounds, experiences, behaviours, ideas, and stories from the participants based on their first-hand information. As the researcher usually talks to the participants based on different interview questions, the researchers can also ask some follow-up questions based on the situations and additional backgrounds. In this case, the researcher used the semi-structured interview session (Creswell, 2012; Atmojo and Nugroho, 2020; Kwee, 2021a) to collect participants’ sharing and experiences of their blended course.

Also, the focus group activity (Morgan, 1998) was used to collect sharing. Focus group activity is useful in qualitative data collection because it can gather and capture the group stories. Also, the participants can share their stories to each other and encourage other peers to share some similar stories and experiences under the same umbrella (Dos Santos, 2020b; Love et al., 2020). As there are 40 participants in this study, four focus group activities were formed (i.e., 10 participants per focus group activity). As a result, 40 interview sessions and four focus group activities were conducted.

Due to the social distancing recommendation, the interview sessions and focus group activities were conducted online. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, many participants did not have any experience about online teaching and learning and online interview techniques. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the government policies, many have met and chatted online via different types of platforms and cell phone applications. Therefore, all participants are positive about the online data collection procedure (Bai, 2022). During the sessions, the researcher used a digital recorder to record the voiced message. All participants agreed with the arrangement.

Data analysis

Two-step data analysis procedure was used (Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Merriam, 2009; Seidman, 2013). The researcher used the open-coding and axial-coding techniques to analyse the qualitative data. First, the researcher used the open-coding step to study the sharing and stories from the interview sessions and focus group activities. Afterward, the researcher further used the axial-coding step to narrow down the data. As a result, three themes and three subthemes were yielded.

Human subject protection

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was supported by the Woosong University Academic Research Funding Department. All the human subjects were informed their rights and consents before the data collection procedure. The current study was supported by the Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2022.

Results and discussion

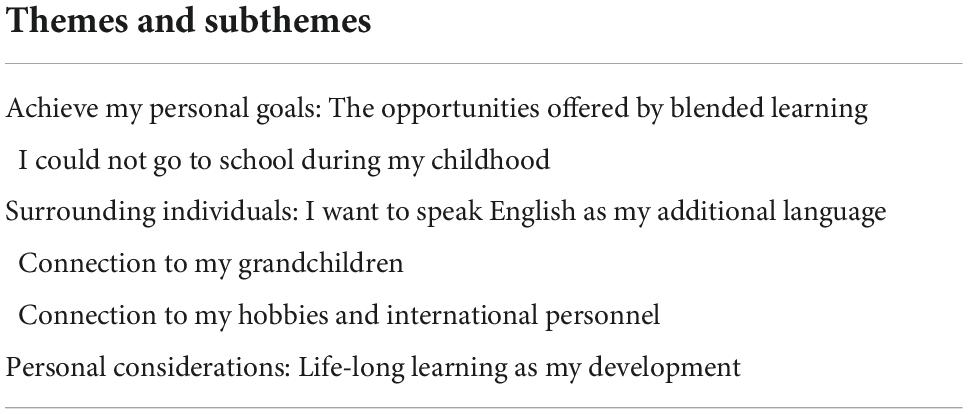

From the participants’ sharing in the data collection steps, the researcher categorised some meaningful stories. Although many of the participants came from different industries and backgrounds before their retirement, they shared some similar and interesting stories from their lives and previous experiences in Hong Kong and mainland China. Table 1 outlines the findings and themes. Please note that the researcher combined the findings and discussion chapters into a single chapter to compare the current findings and the previous literature.

Based on the social cognitive career and motivation theory (Dos Santos, 2021a), the participants categorised three themes and three subthemes. The researcher indicated that personal considerations and surrounding environments and individuals played significant roles in the decisions and decision-making processes of the participants. The following parts explains the relationships between the theoretical framework and stories from the participants.

Achieve my personal goals: The opportunities offered by blended learning

…I want to study…this is something that I want to do for my whole life…I have different goals in my life…become a good child…become a good spouse…become parents…buy my own apartment…support my children to university…retire…but I want to go back to school once I finish all these life commitments… (Participant #8, Interview).

All of the participants mentioned different types of life commitments and responsibilities which had limited their selections and personal choices during the first part of their life. Although many wanted to go to school to achieve their personal goals and interests, many could not do so as they could not abandon their families and other responsibilities. Some also argued that their retirement life was as busy as their previous working schedule. Therefore, the blended learning mode offered them learning opportunities beyond the traditional on-campus and in-person courses,

…I am a retired working professional…but I am a grandparent too…I have to take care of my sons’ family and my grandchildren…although my sons did not request me to do so…I want to do something…to help my children and their family… (Participant #18, Focus Group).

…I don’t want to stop working…I want to continue my busy life…if I stay at home forever, I could not stand…so, I want to take care of my children’s family…cook for them…but I want to take some courses…to keep myself…busy…not just family tasks only…the blended learning course is excellent…because I can study…after I finished my home responsibilities… (Participant #16, Interview).

Traditionally, many elderly Chinese continued to live with their children even after their children got married. The elderly, as grandparents, continue to provide help to their children and grandchildren as a part of their family commitments (Tang et al., 2021). In this study, many of the participants felt that they wanted to continue to provide help to their children’s families and give their energies to their grandchildren. Although life after retirement could have been easier for many of the participants, many had decided to create a balance between their family responsibilities and their learning goals. The blended learning mode offered them the opportunity to take care of their family and learn EAL at the same time (Olesen-Tracey, 2010; Iqbal and Sohail, 2021). All of the participants in this study commented on their positive experiences of the blended learning mode and the positive learning outcomes of blended learning courses (Rafiola et al., 2020).

I could not go to school during my childhood

Many of the participants indicated that they had been unable to go to school during their childhood and teenage years due to poverty, political unrest, and limited opportunities in the East Asian region (Cheng, 1999). During the 1950s and 1960s, the East Asian region experienced political conflicts, which significantly impacted children’s rights. As non-profit organisations and welfare departments could not cover the needs of all children, many of the participants had been unable to go to school and complete their essential education, whereas members of the current generation have the opportunity to go to university with a scholarship and selection. Furthermore, many senior citizens experienced war and political unrest during their lives. Therefore, after their retirement, many decided to achieve their dream via a relaxing timetable. The researcher captured two stories,

…we had eight children in our [the participant’s own] family…only my youngest brother can go to further education institution…all other seven needed to work after primary school education…I worked in a factory for 20 years and other three factories for the rest of my life…we did not have any selections…life is hard, and we have to contribute resources to our family…even if I am married, I still need to pay money to my parents… (Participant #31, Interview).

…before I get married, I worked in a restaurant…I saved a lot of money…but I still need to send money back to my parents…I only received a primary education certificate…after my marriage, spouse and I needed to save money for our apartment…after we had children…we needed to save money for the children…my children could go to university…but we had to give up a lot for them… (Participant #3, Focus Group).

In regard to the blended learning mode, many indicated that the blended EAL course allowed them to enjoy the coursework and instruction using the latest technology. Many indicated that they learnt English language and online learning technology at the same time, which increased their self-efficacy and self-confidence in learning new insights and knowledge at their school,

…I could not learn computer…during my mid-adulthood…but I am using a computer for my English course…we enjoyed both computer and language learning…I felt so great…as a useful person with multiple knowledge…I could not enjoy school in my teenage…we could not change…but we could select something that I want to learn now… (Participant #37, Focus Group).

Due to the limitations resulting from the participants’ own family situations, social environments, and limited opportunities in the city, all of them had been unable to go to school and achieve qualifications during their teenage years and early adulthood. Although many had sought to develop their career during their mid-adulthood, they needed to spend financial resources on their children and family members. In line with the social cognitive career and motivation theory (Dos Santos, 2021a), personal considerations, namely the desire for educational achievement, played a significant role in the motivations and sense-making processes of the participants (Chik and Ho, 2017). Many believed that their stable retirement plan and family situation allowed them to make up for missed opportunities during their childhood, teenage years, and early adulthood. Internal desire drove their learning motivations and behaviours (Dos Santos, 2020c). Although English “is not as easy as what I thought…and the blended learning mode…takes some time to understand…it will not stop my desire and motivation to learn…” (Participant # 35, Interview).

In line with the self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1989, 1997), a strong motivation and desire to learn lay behind the participants’ positive opinions and feedback on their blended learning English course. Although not all of them had been able to handle the online learning platform and computer application appropriately for the first few weeks, they all believed that the dual-learning opportunities (i.e., English and computer skills) had positively upgraded their knowledge and improved their sense-making processes (Wright, 2017).

Surrounding individuals: I want to speak English as my additional language

As mentioned above, due to the political unrest during the 1950s and 1960s, many of the participants had been unable to go to school and receive their qualifications during their teenage years and early adulthood (Cheng, 1999). Although the economic and financial situation has changed in Hong Kong since the 1970s, many of the participants still decided to save their money and resources for their children. Many spoke no other language apart from their mother tongue (Chinese or Cantonese), and therefore they had a desire to become proficient in another language after their retirement. The participants in this study decided to gain foreign language or additional language skills as a hobby. As one participant said,

…my brothers learnt calligraphy…my sisters learnt dancing…and I want to learn English…different people want to learn different skills and new ideas…I believe English is very useful…I want to go to travel…if I can speak English, it can be easier…because we do not need to join the tour…we can go to anywhere with good language proficiency… (Participant #1, Focus Group).

With regard to the blended learning mode, all of the participants indicated that this mode of learning is appropriate and applicable for foreign languages or additional languages and for busy retirees who cannot go to school for on-campus and in-person courses:

…unlike culinary arts, calligraphy, photography…English language courses can be taught online…we watched the videos and listened to the speaking audios with our classmates…we could go back to school for the discussion on Friday…why not?…we could discuss the same materials…but we learnt the first class online…the live lessons…are just the same with the same teacher and classmates…no differences… (Participant #2, Interview).

Connection to my grandchildren

Due to the traditional family practice of East Asian people, three generations often live together in the same apartment (Martin, 1990). Also, due to their geographic proximity, many parents in Hong Kong visit their children’s apartments to do housework. All of the participants in this study were grandparents with children and grandchildren. Many believed that they should establish a good connection with their grandchildren as “well-prepared” grandparents. However, the current generation and traditional-age students may have higher language skills and proficiency in English than in their mother tongue (i.e., Chinese Mandarin or Chinese Cantonese) due to their educational background. Consequently, some participants stated that they experienced difficulties when chatting with their grandchildren. Two interesting stories were captured,

…my grandchildren speak good English language…if I can speak English, I can talk to my grandchildren in English too…why not learn some common hobbies between the two generations…English is very useful too…I wish I could learn English during my childhood…but I can learn English during my late-adulthood…it is very interesting… (Participant #14, Focus Group).

…my grandchildren go to international school…they could not speak Chinese and Cantonese…their parents [participants’ own children] speak English to them…I don’t blame my children and grandchildren…but I have to upgrade my brain and chat with my loved ones…life is too short…if I don’t do something…it can be too late…(Participant #32, Interview).

Connection to my hobbies and international personnel

Many of the participants wanted to upgrade their computer and cellphone skills (Chen and Bryer, 2012). However, they did not want to take basic computer courses as they wanted to learn the applicable skills that could be applied to other courses and real-life practices. Therefore, the blended learning mode offered them the appropriate opportunities. From the perspective of personal hobbies, the researcher captured the following story,

…I want to have good English skills…so I can go to other countries…for tourism…my family…needed to join the tour…because we cannot speak English…but if we can speak English…at the intermediate level…perhaps it is a good start for a self-tour…in other countries, such as Singapore and Malaysia… (Participant #10, Interview).

The blended learning mode also offered the participants opportunities to talk to native speakers across the world without borders (Dhawan, 2020). In fact, due to the COVID-19 travel restrictions, many native English teachers could not come to Hong Kong unless they completed the self-funded quarantine requirements. Therefore, the live sessions during the online lessons allowed the learners to chat with native English teachers,

…we could talk to our British teacher online…we could practice speaking and listen with a real teacher online…then we could come back to our on-campus classroom for the discussion…sometimes, all students could talk to our British teacher via an online platform in the on-campus classroom…it is unique…I love the technology… (Participant #38, Focus Group).

In line with the social cognitive career and motivation theory (Dos Santos, 2021a), personal considerations and surrounding environments and individuals played significant roles in the participants’ motivations and sense-making processes. In fact, many participants spoke about their hobbies in relation to learning, particularly English language learning (Gardner, 2001; You and Dörnyei, 2016). Although none of them had been able to study English language courses and gain educational qualifications during their teenage years and early adulthood, their desire for learning continued to motivate their desire to learn in their retirement.

Under the category of surrounding environments and individuals, the important factors and considerations for the participants were their children and grandchildren. Due to the educational background in Hong Kong, the participants needed to learn English in order to have effective communication and conversations with their grandchildren. As their desire to connect with their family members was strong, their motivation was increased (Evans and Morrison, 2011).

In line with the self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1989, 1997), the data indicated that the participants’ motivation and desire to learn significantly drove their self-efficacy and potential learning outcomes and achievements. Although the computer-aided and blended learning modes were new to many of them, their motivation, self-confidence, and desire to learn allowed them to overcome the challenges and achieve their goals successfully (Dos Santos, 2020a).

Personal considerations: Life-long learning as my development

Hong Kong is one of the well-known business hubs and financial centres in the East Asian region. Working professionals need to gain and renew their registrations and licences in order to continue in their positions. In addition, many positions require continual professional development (CPD) hours for career purposes (Choi and Tang, 2009; Lam, 2012). Therefore, the concept of life-long learning is not new to residents in Hong Kong. From the perspective of learning motivation, the researcher captured two interesting stories,

…learning is my hobby for sure…I love learning…but I received several vocational certificates for my job before my retirement…I was a professional technician…but my job was very busy…and my wife also needed to work for two of our children…we both did not have any time to learn some leisure courses, such as English…now, both of us are retired…we are taking the same English courses together…I am glad that we are partner and we are classmates too… (Participant #5, Interview).

…the government always promotes the ideas of life-long learning…I want to learn some new skills too…I gained several certificates for my works…such as a plumber…I am retired now…I don’t want to waste my time…because I want to learn something…I selected English because it sounds interesting…if I can speak English to my grandchildren…it seems like it is an achievement… (Participant #15, Focus Group).

From the perspective of the blended learning mode, many of the participants believed that they should learn multiple types of knowledge and skills to compete in today’s rapidly changing world (Choi and Tang, 2009; Dhawan, 2020). Although all of the participants were retirees, their desire to learn did not end because of their change in status. Many of them believed the combination of computer-aided language learning and English courses worked perfectly,

…why don’t we gain some new skills as our development…from computer to online English courses…human should continue to learn…we should not stop learning…I want to learn dancing, cooking, and English…online…on Monday and Wednesday, I learn English online…on Tuesday online and Thursday on-campus, I learn cooking…and during the weekend, I dance with my friends…I don’t want to stop… (Participant #25, Focus Group).

In line with the social cognitive career and motivation theory (Dos Santos, 2021a), achievement of education goals, personal considerations, and desire for learning played significant roles in the participants’ decision-making processes. Although all of the participants were senior citizens and retirees, many continued to upgrade their skills and proficiencies. In their case, they had selected English language courses for their professional development.

In line with the self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1989, 1997), the participants expressed their positive experiences of the blended EAL course and its computer-aided teaching and learning strategy. Many believed that the current blended learning arrangement had significantly increased their motivation to learn and their expectations of computer learning. Although the participants were all retirees, their desire to learn had not ended due to their age and occupational backgrounds. The self-efficacy of this group of participants was high enough to overcome some potential challenges and difficulties.

Limitations and further developments

First, the current study only collected data from an adult learning centre in Hong Kong. As many countries and regions may face similar backgrounds and issues, data from other regions may be useful. Therefore, future research studies may expand the location and site to other countries in order to create a comprehensive solution in the current field.

Second, this study collected data from the EAL classroom environment. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the online learning trends in education, other subject matters may face the same issues. Therefore, future research studies may expand the subject matters, such as clinical courses, vocational-based courses etc., in order to cover other student populations.

Third, blended learning is an important educational trend. However, online-only courses may face other issues during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, future research studies should collect data from online-only courses and students who completed their courses online for a comprehensive understanding.

Conclusion

Online and blended learning became an educational trend during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Some studies have been conducted to answer the problems for K-12 and university students. The current study captured the experiences and understanding of a group of senior citizens who enjoyed the blended learning modes for the EAP courses in Hong Kong. The findings will fill the research and practical gaps in the online and blended learning area. Furthermore, the study provides a reference to educational leaders and curriculum developers to re-visit their in-person and face-to-face courses to online and blended learning modes in order to meet the needs of their students after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2022. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study received support from Woosong University Academic Research Funding 2022.

Acknowledgments

This study is completed with the coordination of H. F. Lo.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

About Elder Academy (2022). About elder academy. Available online at: https://www.elderacademy.org.hk/en/aboutea/index.html (accessed March 9, 2022)

Atmojo, A. E. P., and Nugroho, A. (2020). EFL classes must go online! Teaching activities and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Regist. J. 13, 49–76. doi: 10.18326/rgt.v13i1.49-76

Bai, X. (2022). Preservice teachers’ evolving view of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on online learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 17, 212–224. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v17i04.25923

Bandura, A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Dev. Psychol. 25, 729–735. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.729

Brown, M., Hughes, H., Keppell, M., Hard, N., and Smith, L. (2015). Stories from students in their first semester of distance learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 16, 1–17. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v16i4.1647

Chen, B., and Bryer, T. (2012). Investigating instructional strategies for using social media in formal and informal learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 13:87. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v13i1.1027

Chik, A., and Ho, J. (2017). Learn a language for free: Recreational learning among adults. System 69, 162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.07.017

Cho, D. W. (2012). English-medium instruction in the university context of Korea: Tradeoff between teaching outcomes and media-initiated university ranking. J. Asia TEFL 9, 153–163.

Choi, P. L., and Tang, S. Y. F. (2009). Teacher commitment trends: Cases of Hong Kong teachers from 1997 to 2007. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 767–777. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.005

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson.

DeWaelsche, S. A. (2015). Critical thinking, questioning and student engagement in Korean university English courses. Linguist. Educ. 32, 131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2015.10.003

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020a). Exploring international school teachers and school professional staff’s social cognitive career perspective of life-long career development: A Hong Kong study. J. Educ. Elearn. Res. 7, 116–121. doi: 10.20448/journal.509.2020.72.116.121

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020b). I want to become a registered nurse as a non-traditional, returning, evening, and adult student in a community college: A study of career-changing nursing students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:5652. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165652

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020c). Male nursing practitioners and nursing educators: The relationship between childhood experience, social stigma, and social bias. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:4959. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144959

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021a). Motivations and career decisions in occupational therapy course: A qualitative inquiry of Asia-Pacific international students in Australia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 12, 825–834. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S288885

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021b). Self-efficacy and career decision of pre-service secondary school teachers: A phenomenological analysis. Int. J. Instr. 14, 521–536. doi: 10.29333/iji.2021.14131a

Evans, S., and Morrison, B. (2011). Meeting the challenges of English-medium higher education: The first-year experience in Hong Kong. Engl. Specif. Purp. 30, 198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2011.01.001

Gardner, R. C. (2001). Language learning motivation: The student, the teacher, and the researcher. Texas Pap. Foreign Lang. Educ. 6, 1–18.

Gilboy, M., Heinerichs, S., and Pazzaglia, G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 47, 109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.008

Illeris, K. (2018). An overview of the history of learning theory. Eur. J. Educ. 53, 86–101. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12265

Iqbal, S., and Sohail, S. (2021). Challenges of learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Gandhara Med. Dent. Sci. 8:1. doi: 10.37762/jgmds.8-2.215

Kim, D., Wang, C., and Truong, T. N. N. (2021). Psychometric properties of a self-efficacy scale for English language learners in Vietnam. Lang. Teach. Res. 136216882110278. doi: 10.1177/13621688211027852

Kim, J., Tatar, B., and Choi, J. (2014). Emerging culture of English-medium instruction in Korea: Experiences of Korean and international students. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 14, 441–459. doi: 10.1080/14708477.2014.946038

Kwee, C. (2021a). I want to teach sustainable development in my English classroom: A case study of incorporating sustainable development goals in English teaching. Sustainability 13:4195. doi: 10.3390/su13084195

Kwee, C. (2021b). “Will i continue online teaching? Language teachers’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in Proceedings of the 13th international conference on computer supported education (CSEDU 2021), Vol. 2, (Setúbal: Science and Technology Publications), 23–34. doi: 10.5220/0010396600230034

Lam, B. R. (2012). Why do they want to become teachers? A study on prospective teachers’ motivation to teach in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 21, 307–314.

Lent, R., and Brown, S. (1996). Social cognitive approach to career development: An overview. Career Dev. Q. 44, 310–321. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00448.x

Lent, R., Brown, S., and Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 45, 79–122. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Love, B., Vetere, A., and Davis, P. (2020). Should interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) be used with focus groups? Navigating the bumpy road of “iterative loops,” idiographic journeys, and “phenomenological bridges”. Int. J. Qual. Methods 19, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/1609406920921600

Ma, K., Chutiyami, M., Zhang, Y., and Nicoll, S. (2021). Online teaching self-efficacy during COVID-19: Changes, its associated factors and moderators. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 6675–6697. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10486-3

Maican, M.-A., and Cocoradă, E. (2021). Online foreign language learning in higher education and its correlates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13:781. doi: 10.3390/su13020781

Mandasari, B., and Oktaviani, L. (2018). English language learning strategies: An exploratory study of management and engineering students. Premise J. Engl. Educ. 7:61. doi: 10.24127/pj.v7i2.1581

Martin, L. (1990). Changing intergenerational family relations in East Asia. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 510, 102–114. doi: 10.1177/0002716290510001008

Mercer, S. (2018). Psychology for language learning: Spare a thought for the teacher. Lang. Teach. 51, 504–525. doi: 10.1017/S0261444817000258

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Meşe, E., and Sevilen, Ç (2021). Factors influencing EFL students’ motivation in online learning: A qualitative case study. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 4, 11–22. doi: 10.31681/jetol.817680

Morgan, D. (1998). The focus group guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781483328164

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q. (2019). Acting, thinking, feeling, making, collaborating: The engagement process in foreign language learning. System 86:102128. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.102128

Olesen-Tracey, K. (2010). Leading online learning initiatives in adult education. J. Adult Educ. 39, 36–39.

Rafiola, R. H., Setyosari, P., Radjah, C. L., and Ramli, M. (2020). The effect of learning motivation, self-efficacy, and blended learning on students’ achievement in the industrial revolution 4.0. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 15:71. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i08.12525

Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Shen, X., and Liu, J. (2022). Analysis of factors affecting user willingness to use virtual online education platforms. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 17, 74–89. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v17i01.28713

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Tang, F., Li, K., Jang, H., and Rauktis, M. B. (2021). Depressive symptoms in the context of Chinese grandparents caring for grandchildren. Aging Ment. Health 26, 1120–1126. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1910788

Taşçı, G., and Titrek, O. (2019). Evaluation of lifelong learning centers in higher education: A sustainable leadership perspective. Sustainability 12:22. doi: 10.3390/su12010022

Tayan, B. (2017). Students and teachers’ perceptions into the viability of mobile technology implementation to support language learning for first year business students in a Middle Eastern university. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 5:74. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.74

Wright, B. M. (2017). Blended learning: Student perception of face-to-face and online EFL lessons. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 7:64. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v7i1.6859

Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

You, C., and Dörnyei, Z. (2016). Language learning motivation in China: Results of a large-scale stratified survey. Appl. Linguist. 37, 495–519. doi: 10.1093/applin/amu046

Keywords: additional language learning, blended learning, English language learning, foreign language learning, learning motivation, life-long learning, online learning, social cognitive career and motivation theory

Citation: Dos Santos LM and Kwee CTT (2022) “I want to learn English after retirement”: The blended learning experiences of senior citizens. Front. Educ. 7:899848. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.899848

Received: 19 March 2022; Accepted: 31 October 2022;

Published: 21 November 2022.

Edited by:

Yvette Renee Harris, Miami University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kristine Sudbeck, Nebraska Indian Community College (NICC), United StatesMohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Hassan Ahdi, Global Institute for Research Education & Scholarship, Netherlands

Copyright © 2022 Dos Santos and Kwee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luis M. Dos Santos, bHVpc21pZ3VlbGRvc3NhbnRvc0B5YWhvby5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Luis M. Dos Santos

Luis M. Dos Santos Ching Ting Tany Kwee

Ching Ting Tany Kwee