- 1Group 8 Education, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Yarra Valley Grammar, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Education is undergoing a period of sustained change from a focus on traditional skills and compliance to positional authority, to a focus on 21st century skills and more adaptable behaviors. In the light of this changing context, this study examined the role of school principalship and identified those attributes which teachers and students recognize as being desirable in a school leader today. Principals come in all shapes and sizes, have different leadership styles, spend time on different things, and are judged on their performance based upon what they say and do, how well their school is performing, and how happy the led are with their leader. The study looked at the various leadership styles emerging from the extensive literature. The statements used in the survey were drawn from six different principal styles, with five attribute statements for each style. Teachers and students (N = 405) across nine schools completed a two-part survey in which they were asked to rank leadership attributes in order of importance. In this way we identified specific attributes deemed desirable in a school leader. The results showed high statistical significance. The findings were quite conclusive: Teachers and students preferred the Integrated Leadership style which combines instructional and transformational leadership and agreed on the importance of principal as role model for both students and colleagues. This key element of the principal’s role was linked to two other attributes, these being that a principal should (a) foster a shared vision in the school, and (b) have a vision for the school that they help to develop with colleagues. These findings give rise to some interesting questions, one being: What does it mean to be a role model in the context of 21st century education? A second being, what is the link between shared vision and role modeling?

Introduction

There is ample evidence in the literature of the importance of the school principal in achieving desirable outcomes in their schools.

Across six rigorous studies estimating principals’ effects using panel data, principals’ contributions to student achievement were nearly as large as the average effects of teachers identified in similar studies. Principals’ effects, however, are larger in scope because they are averaged over all students in a school, rather than a classroom. (Grissom et al., 2021)

Shepherd-Jones and Salisbury-Glennon (2018) looked at the influences different leadership styles have upon teacher motivation. Their findings were that teacher motivation and, subsequently, the student experience in class were impacted by the perceptions of the principal’s competency.

The logical next questions to ask are: What is the nature of this effect? What kind of principal? What beliefs, attitudes and behaviors must the leader have to suit the role and the realities of the institutions they are to lead in a modern context? How might the principal construct their role and use their time to best effect in the 21st century? The literature is beginning to describe such an individual; how they perceive themselves and how they understand the communities they are to lead.

Education is undergoing a period of sustained change:

[T]the ways we work are changing, the ways we think are altering and the tools we use in our employment are almost unrecognizable compared to those that existed 50 years ago. We can anticipate even more of a shift in another 50 years. As global economies move to the trade in information and communications, the demands for teaching new skills will require an educational transformation of a similar dimension to that which accompanied the shift from the agrarian to the industrial era. (Griffin et al., 2012, Ch1)

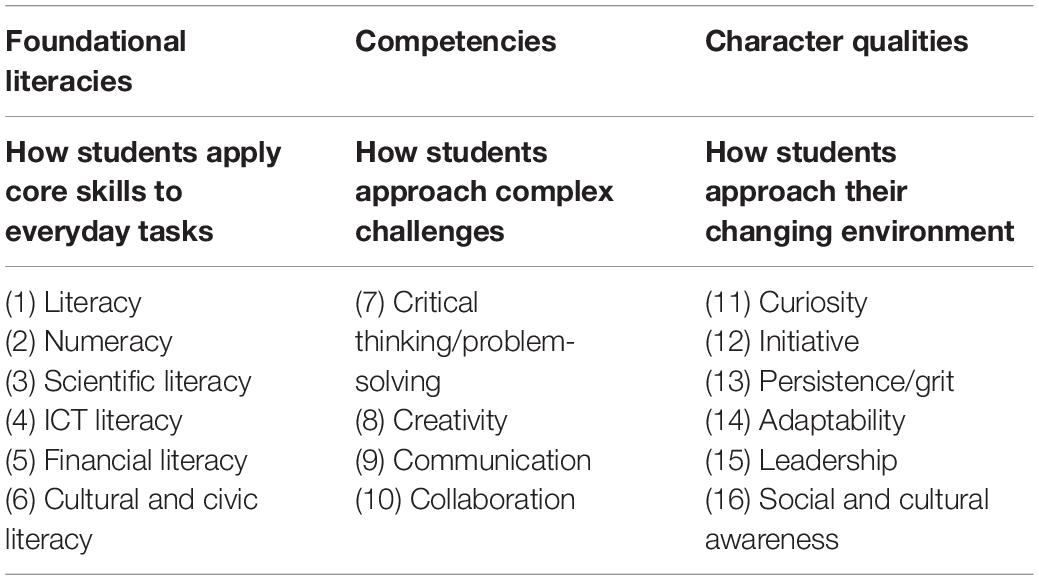

The shift is from a paradigm of traditional skills and compliance to positional authority, to a focus on so-called 21st century skills and more adaptable behaviors. Table 1 provides one formulation of 21st century skills.

Table 1. Twenty-first century skills as formulated and published by the World Economic Forum [WEF] (2015).

In addition to the traditional skills such as numeracy and literacy:

“success lies in being able to communicate, share, and use information to solve complex problems, in being able to adapt and innovate in response to new demands and changing circumstances, in being able to marshal and expand the power of technology to create new knowledge, and in expanding human capacity and productivity.” (Binkley et al., 2012, Ch2)

School principals lead schools. The skills needed to steer the complex organizations which are our schools go well beyond the ability to “look the part” and command respect. Principals in schools exhibit many different traits, employ an array of leadership behaviors and in some ways are spoiled for choice in how they plot a course for the betterment of their school communities, the students, the teachers, and their families.

Given the changing context referred to above, are there now styles of leadership that are more suited to the emerging future than others and what might those styles be, or at least what might be some of their key characteristics?

Thus, the key research question is “Have these changes in desired student outcomes led to some principal attributes among different leadership styles being more preferred than others?” If so, can we draw any conclusions about what principal behaviors are better adapted to current and future circumstances?

To begin to grapple with this question, a first step is to answer the question: do different leadership styles suit different contexts? One researcher (Cascadden, 1996) suggests different leadership styles may suit different school contexts:

Coming from private schools, where stakeholder groups tend to be more homogeneous, the researcher felt that school leaders should be directive, philosophic, visionary leaders—people who articulate a specific vision and help the organization rally around that vision. However, now, the researcher feels that public schools may not be best served by visionary leadership, but rather by democratic leadership. Public schools serve a much more heterogeneous community, and the leaders of these schools must be aware of balancing their own visions of what public education ought to be like with the visions of others. (Cascadden, 1996, p. 162)

A review of the relevant literature reveals that there are distinct and different leadership styles adopted by principals; often informed by personal preference more than anything else. The changing role of the principal and the demands upon their time and energy mean that principals may not have the opportunity to consider the purpose of their role (Botha, 2004). Indeed, there is no clear consensus about the role and the most effective methods to employ to be good at it.

For the purposes of this study, there were six clearly identified leadership styles which cover the spectrum of leadership approaches for principals identified in the literature. Other ways of covering this spectrum were also considered but were discarded in favor of the current approach. The six distinct styles are recognizable by belief, attitude, approach and ultimately outcome. Each style can be ascribed certain attributes which may be measured for their relative effectiveness. The chosen approach to answer the key research question has been to review the different leadership styles and to draw from them this series of representative attributes, which in turn, formed the basis of a survey to elicit from a range of teachers, students and school leaders, which attributes are preferred. This framework provided a coherent series of questions eliciting discerning responses from participants.

Principals’ Leadership Styles

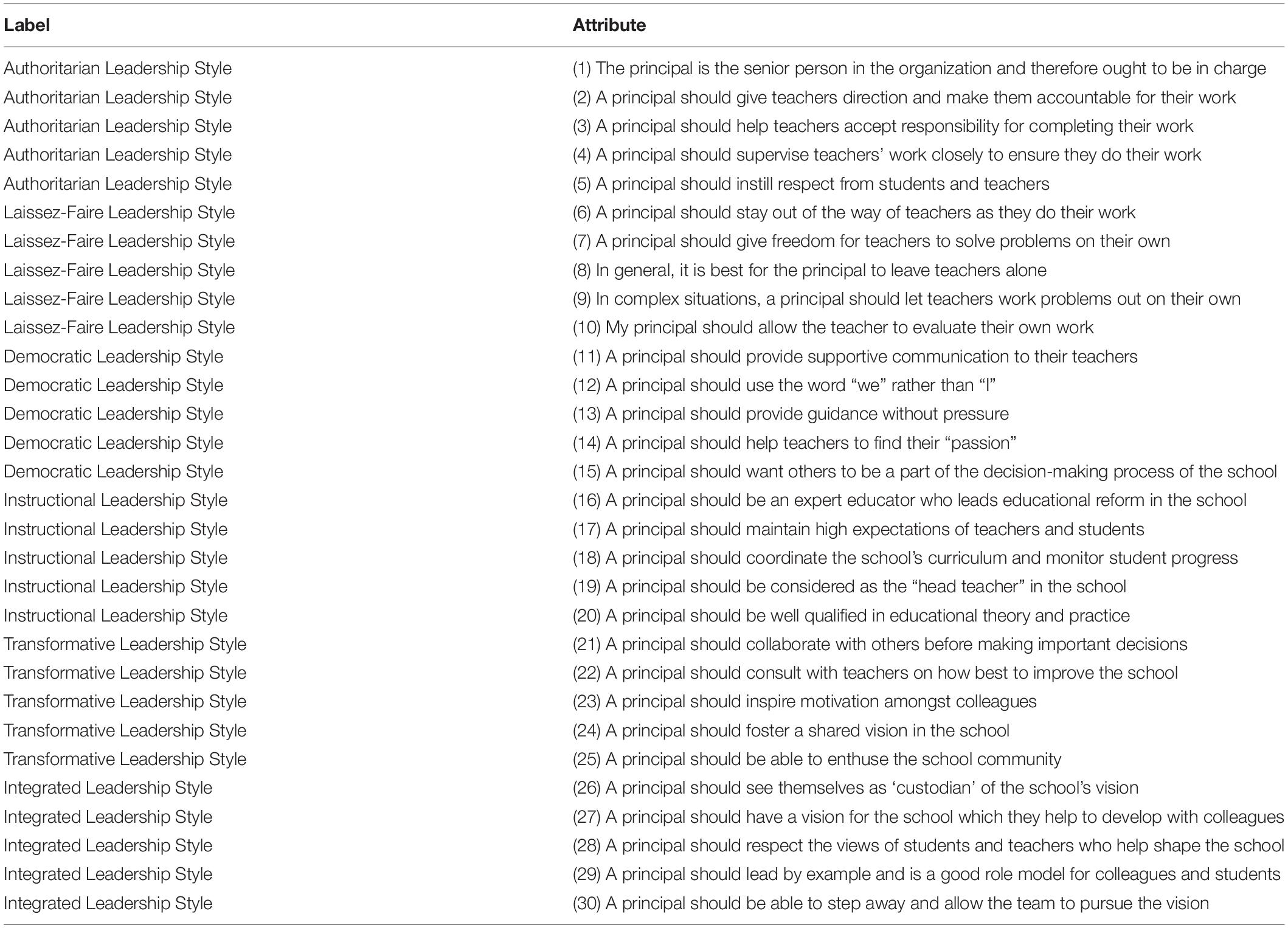

The literature revealing six different styles of leadership available to principals are summarized in the following sections. Table 2 summarizes the thirty attributes that have been drawn from these six leadership styles and subsequently used in the surveying phase of the research.

Autocratic (or Authoritarian) Leadership

Autocratic leaders hold a fundamental view that their followers need to be directed and kept under control at all times. This kind of leader assigns tasks and defines how to do them, making it quite clear where they and others sit in a hierarchical model of the organization. This is the more traditional image of the headmaster/head teacher/principal as being ultimately responsible for all elements of the operation. Whilst being discredited in most organizations in recent years, autocratic leadership does have some redeeming features. When effective, this leadership type can be perceived as decisive and inducts new teachers with clarity about their role and what is expected of them. (Ololube, 2015). This kind of directive approach from the “superior” in the organization impels followers to do their job and do it well. This style of leadership, however, fosters compliance over more desirable motivations and can lead staff to becoming dependent on the leader while not experiencing a true sense of autonomy within the organization. The unintended consequence is that co-workers may lose their creativity, and the self-motivation to improve. In a sense, the leader rather than individual teachers bears the responsibility for their work (Kars and Inandi, 2018). It seems incongruous that a well credentialled workforce is given little autonomy in this model.

Laissez Faire Leadership

Laissez faire leadership provides little or no direction and gives employees as much freedom as possible such that significant authority is given to the employees and they must determine goals, make decisions, and resolve problems on their own (Sharma and Singh, 2013). The relative merits of this style of leadership are open to dispute (Skogstad et al., 2007; Yang, 2015), but fundamentally this approach devolves authority to subordinates in the organization either formally or informally and allows decision making to be distributed. This is the antithesis of the authoritarian style.

Democratic Leadership

Democratic leadership styles suggest that leadership can include participants in the process rather than treating members of the organization as merely followers of the leader. This may be on a sliding scale from consultation with members of the organization through to power sharing and real distributed leadership (Woods, 2020). Giving agency to and empowering others are both elements of a democratic leadership model. This differs markedly from a laissez-faire model in that there is not an abdication of authority but rather an invitation for others to be involved in the decision-making process at the appropriate level and in the appropriate ways. The leadership role of the principal is something akin to the principle of primus inter pares.

Instructional or Expert Leadership

Instructional or expert leadership characterizes the principal as an important source of educational expertise in the organization. Expertise in an educational institution is often shared amongst several highly qualified individuals, but the principal certainly needs to be one of these and deemed within the institution to be an important one with a strong influence on others. The principal is not the sole instructional leader but the leader of instructional leaders (Sebastian et al., 2017). Aimed at improving the practice of teaching, the principal’s role is to maintain high expectations for teachers and students, supervise classroom practice, coordinate the school’s curriculum, and monitor student progress (French and Raven, 1959). In this case, the leader is deemed to be well qualified for the role and their experience in the role is deferred to and valued. Expert power is derived purely from personal traits and is wholly independent of a position in an organization. Expert power only lasts if an expert keeps getting good results and is not acting purely for personal gain (French and Raven, 1959).

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership provides intellectual direction from the leader and aims at innovating within the organization, while empowering and supporting teachers as partners in the decision-making process (Marks and Printy, 2003). Such leaders operate at the level of influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized relationships. This style is characterized by the ability of a leader to influence a follower because of the follower’s admiration, respect, or identification with the leader. Referent power is a form of reverence gained by a leader who has strong interpersonal relationship skills (Lovegrove and Lewis, 1991; Balson, 1992; Lewis, 1997).

Transformational leadership is the process by which a leader fosters group or organizational performance beyond expectation by virtue of the strong emotional attachment with his or her followers combined with the collective commitment to a higher moral cause. (Diaz-Saenz, 2011, p. 299)

This style becomes more important as organizational leadership becomes increasingly about collaboration and influence and less about command and control (Merry, 2009). Leaders who can earn and maintain the trust of others consistently drive productivity, enhance engagement, and retain key talent. Transformational leadership focuses on problem finding, problem solving, and collaboration with stakeholders, with the goal of improving organizational performance (Hallinger, 1992). To improve the collective capacity of the organization and its members to achieve results, transformational leadership seeks to raise participants’ levels of commitment to the organization, in this case the school. Such leadership operates at the level of motivation rather than compulsion or reward.

Integrated Leadership: A Combined Approach

A combined instructional and transformational leadership model replaces a traditional hierarchical and positional system with a model of shared instructional leadership. The principal is not the sole instructional leader but the leader of instructional leaders (Sebastian et al., 2017). “Schools prosper when principals and teacher leaders, whether formal or informal, integrate transformational and instructional leadership approaches in their interactions with others” (Printy et al., 2009). Instructional leadership and transformational leadership speak once again to the behavior or approach of the principal. Instructional leadership is linked closely with expert power and is predicated upon the professional credibility of the leader (Hallinger, 2005). Transformational leadership is based upon the development of teacher skill and broader empowerment within the organization.

Determining a Preferred Style

Clearly, there are lots of different approaches available to leaders. Principals exercise freedom to choose the most appropriate leadership style and what tactics to employ. How do principals know which ones to choose? Accepting that the conduct of the principal has a significant impact upon colleagues and students, we ought to focus on what precisely constitutes desirable and undesirable behaviors by the leader. At the same time, we should not overlook that principals operate within a context that shapes to a certain extent what choices they can make.

Costellow (2011) pondered how such behaviors might be determined. His study looked at a group of 21 leadership traits and determined that among all groups and sub-groups of participants, Communication was the most highly rated trait, followed closely by Discipline, Culture, Visibility, and Focus. Such an approach does not indicate which, if any, leadership style is to be preferred.

The approach we have taken is to develop a list of attributes associated with the six leadership styles and then to determine which of these attributes are preferred by students, teachers and school leaders and match these to an existing leadership style. Each leadership style was characterized by a range of leadership attributes or traits which emerged from the literature review. These six sets of attributes were compared to determine and separate a set of five attributes that best represented each leadership style, a total of 30 attributes being manageable in the survey design. The final set of 30 attributes was vetted for completeness to ensure that no significant leadership attribute cited in the literature was omitted. By identifying a small set of leadership attributes, we may determine how the principal can make the most positive impact in the performance of their duties. Based on our survey results, our findings show which choices principals should make in the opinion of their stakeholders; students, their teachers and school leaders.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative research study used a survey to seek the opinions of leaders, teachers, and students as to the desirable attributes of a school principal. The survey canvassed a range of principal attributes, drawn from multiple leadership styles.

As noted in the previous sections, the literature provides examples of principal attributes which fall into a range of leaderships styles (authoritarian, transformational, etc.) which have been expressed by principals over time. For example, attribute 15 – A principal should want others to be a part of the decision-making process of the school assigned to Democratic Leadership (Woods, 2020) and 23 – A principal should inspire motivation amongst colleagues assigned to Transformational Leadership (Diaz-Saenz, 2011). Currently, our education systems are in flux—the desire to develop 21st century skills competing with the culture surrounding the development of traditional skills. The question we sought to answer through this study was: “Have these changes in desired student outcomes led to some principal attributes among different leadership styles being more preferred than others?” If so, can we draw any conclusions about what principal behaviors are better adapted to current and future circumstances?

Participant Recruitment

To attract participants to the study, the researchers approached the nine schools of the Associated Grammar Schools of Victoria (AGSV) in Australia: Assumption College, Camberwell Grammar, Ivanhoe Grammar, Marcellin College, Mentone Grammar, Peninsula Grammar, Penleigh and Essendon Grammar, Trinity Grammar, and Yarra Valley Grammar. This group includes boys’ only schools and coeducational schools, both Catholic and independent.

An information email containing a link to the study was sent out to the principals of the nine AGSV schools for them to forward to their staff (teachers and leaders) and to their Year 11 students. All principals agreed to participate as described. Participation in the survey was voluntary. No attempt was made to determine whether respondents represented all nine schools invited to participate in the study.

Survey Design

To answer the primary research question, we designed a simple online survey questionnaire. The survey was conducted through an unbranded site on a commercial platform using a single URL to access the survey.

Thirty statements were drawn from the literature to represent the attributes of principals using the following styles (see Table 2 which displays the 30 statements and their categories):

• Authoritarian Leadership Style.

• Democratic Leadership Style.

• Instructional Leadership Style.

• Integrated Leadership Style.

• Laissez-Faire Leadership Style.

• Transformative Leadership Style.

The survey was divided into two parts.

In Part 1 of the survey, each respondent was asked to indicate their level of agreement with a statement incorporating each of the attributes—for example: “A principal should foster a shared vision in the school”—on a 5-point Likert scale from “I disagree completely” (score of 1) to “I agree completely” (score of 5).

In Part 2, the attributes that received a response of “I agree completely” were re-presented to the respondent with the instruction to order these attributes (using a “drag and drop” technique) from the one that would have the most influence on their evaluation of a principal down to the one with the least influence.

In the first part of the survey, the thirty attributes were presented in a random order to each respondent, this order being retained for the second part. This meant that if a respondent only partially ordered their list of attributes the unordered attributes would appear as noise rather than as a systematic bias.

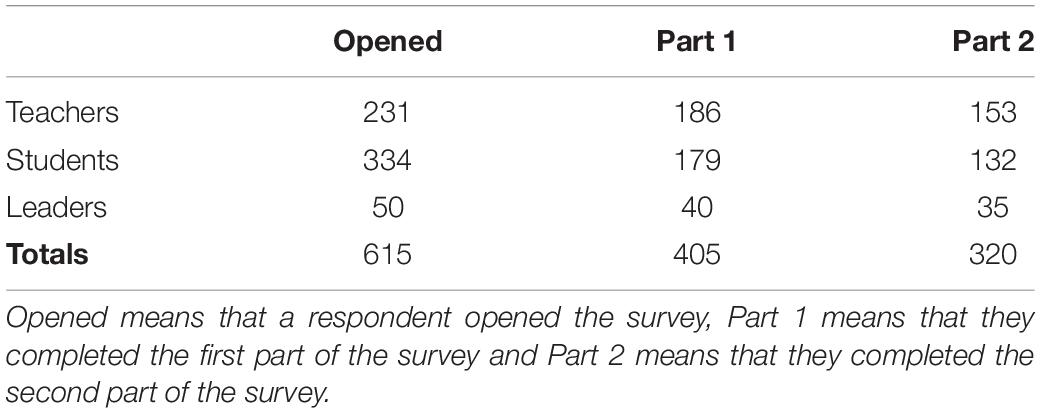

On accessing the survey, a respondent needed to select their role: school teacher, school student, or school leader. This step was obligatory for the respondent to move onto the first part of the survey. The first part of the survey was also obligatory, meaning that if it was not completed the survey would end. The second part of the survey was not obligatory so that completion was voluntary. Three hundred and twenty respondents completed both Parts 1 and 2 (see Table 3 for the numbers of respondents at each stage).

No attempt was made to ascertain any demographic information about respondents beyond the three categories nor to link respondents to their respective schools.

Results

Part 1

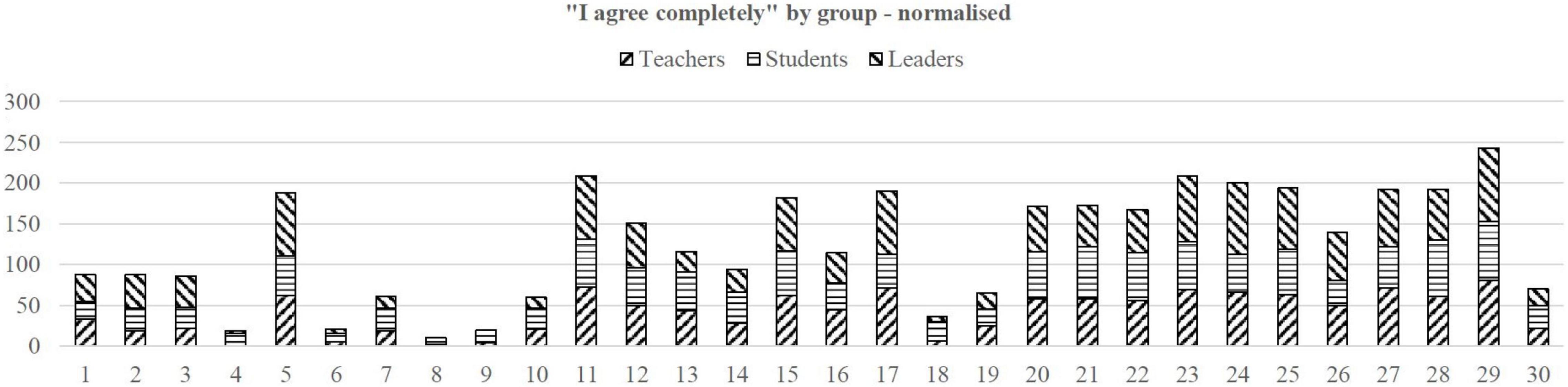

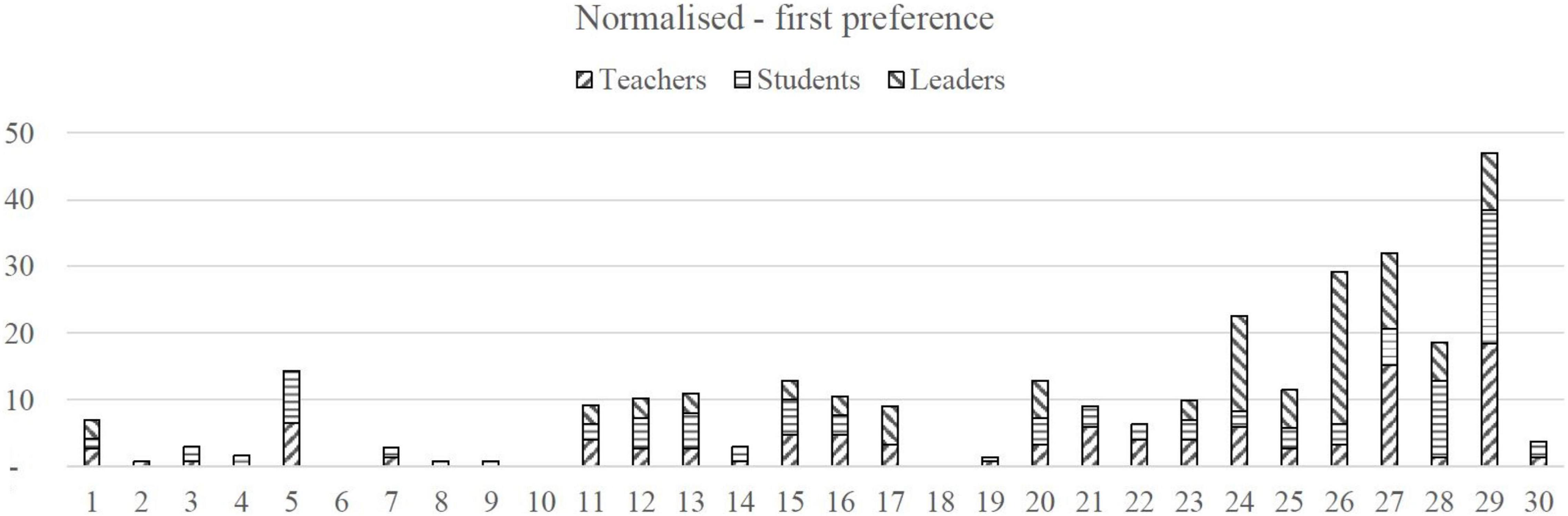

A summary of the analysis from Part 1 can be found in Figure 1 and the full text for each attribute, otherwise shown numbered from 1 to 30, are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. The “I agree completely” responses by normalized group (i.e., each group has been scaled to add up to 100 responses and then combined from Part 1 of the survey).

Figure 1 presents only the “I agree completely” responses by normalized group (i.e., each group has been scaled to add up to 100 responses) and then combined. The graph displays these data. The attribute 29 – A principal should lead by example and is a good role model for colleagues and students is statistically significant at the 5% level (i.e., p < 0.05) in the combined sample (as well as for the student sample alone).

From these combined data the attributes with the highest proportion of “I agree completely” responses, in descending order were:

• 29 – A principal should lead by example and is a good role model for colleagues and students.

• 11 – A principal should provide supportive communication to their teachers.

• 23 – A principal should inspire motivation among colleagues.

• 24 – A principal should foster a shared vision in the school.

• 25 – A principal should be able to enthuse the school community.

As noted, only the first of these was statistically significant, which is to be expected with this type of simple survey.

Part 2

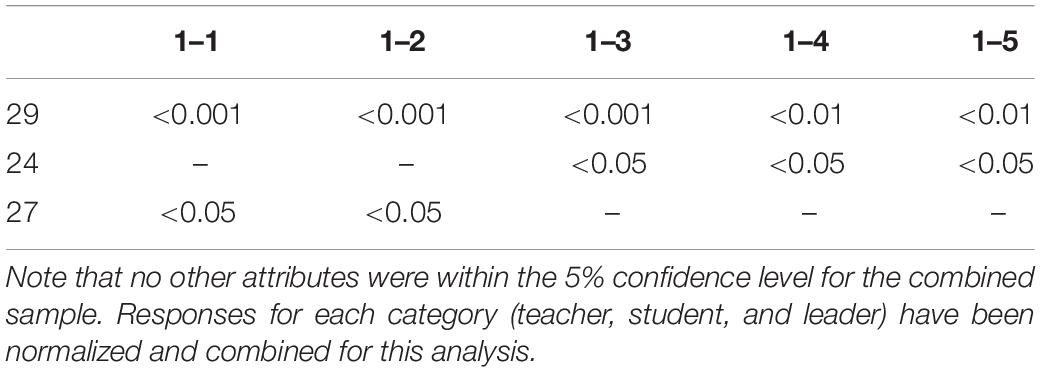

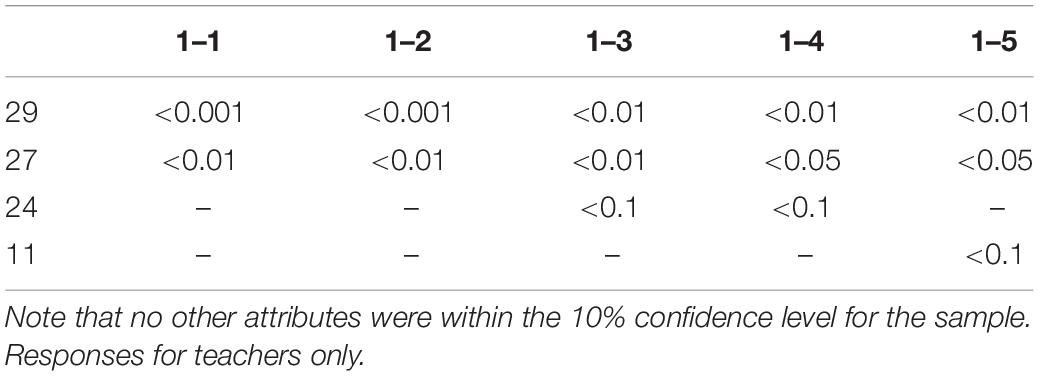

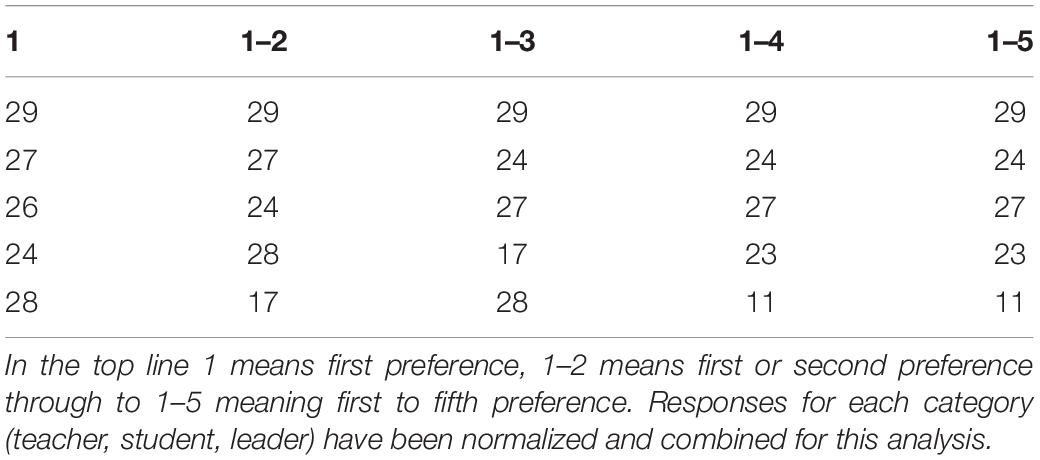

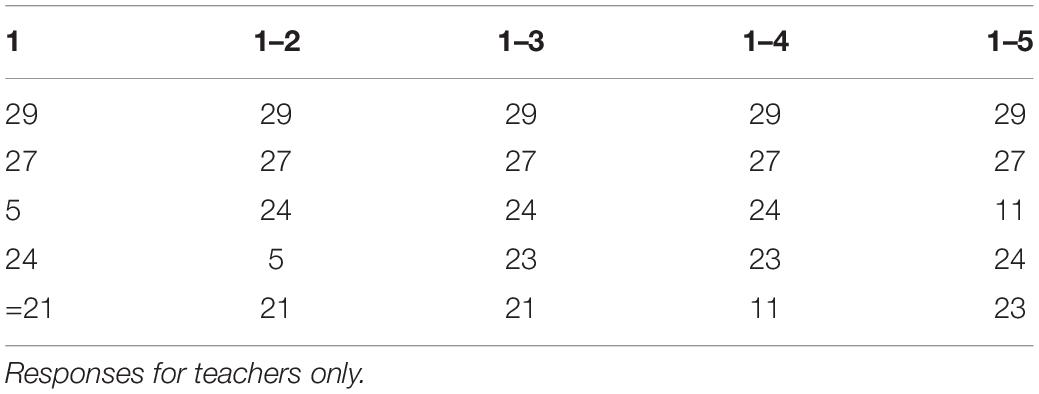

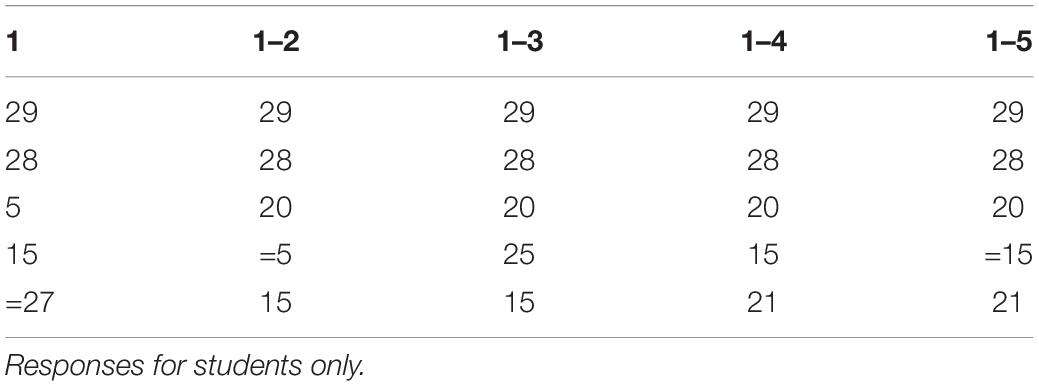

Part 2 is presented with the three categories normalized. Figure 2 shows how often each attribute was given first preference by the three categories of respondents. This analysis was then repeated to see which attributes were given first or second preference and so on up to which attributes were given first to fifth preference. The outcome of these five trials is shown in Table 4 with the top line (29 in all cases) representing the highest in each case. Table 5 shows confidence levels for the attributes which were statistically significant in this analysis. Similar analyses performed on each category are shown in Supplementary Appendix 1 and Tables 6–11 provide the corresponding outcomes.

Figure 2. Shows how often each attribute was given first preference by the three normalized categories of respondents in Part 2 of the survey.

Table 4. Preference order of attributes from Part 2 of the survey, the numbers in the body of the table refer to attributes as numbered in Table 2.

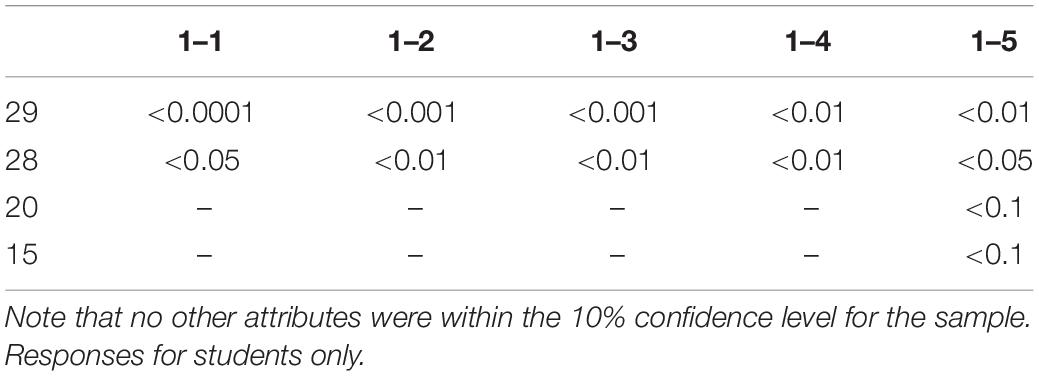

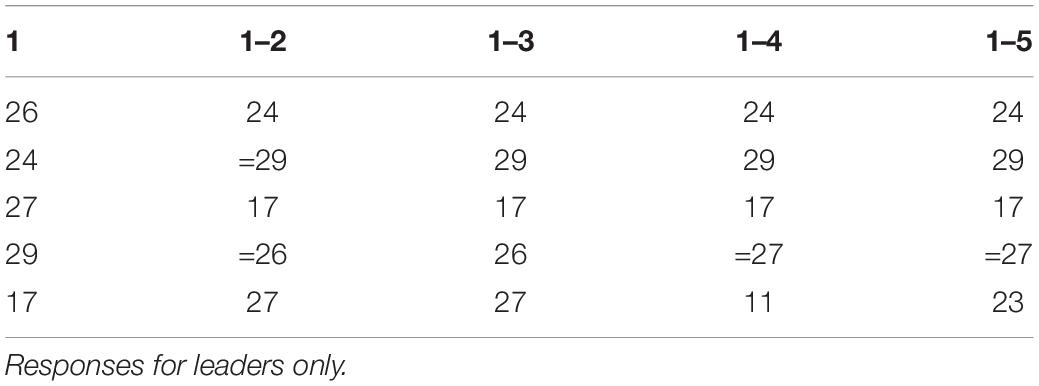

Table 6. Preference order of attributes where 1 means first preference, 1–2 means first or second preference through to 1–5 meaning first to fifth preference.

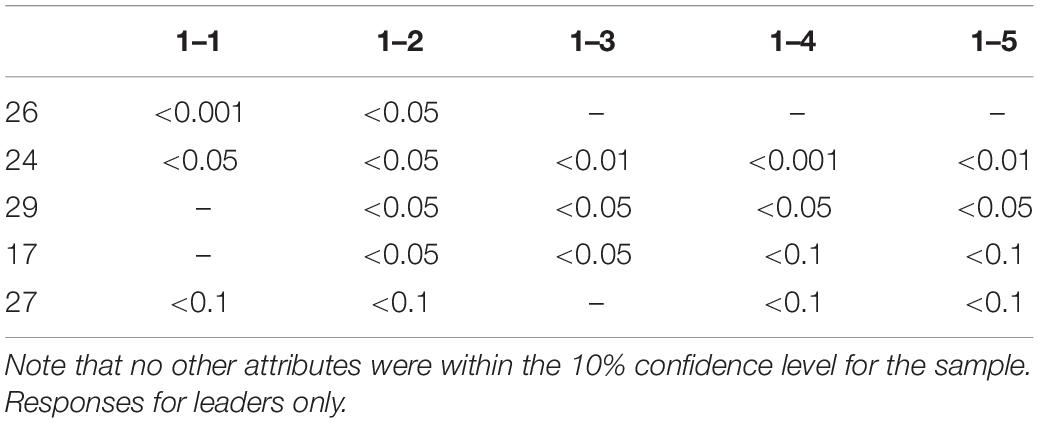

Table 8. Preference order of attributes where 1 means first preference, 1–2 means first or second preference through to 1–5 meaning first to fifth preference.

Table 10. Preference order of attributes where 1 means first preference, 1–2 means first or second preference through to 1–5 meaning first to fifth preference.

What we can deduce from Tables 4, 5 is that the top three attributes were as follows:

• 29 – A principal should lead by example and is a good role model for colleagues and students.

• 24 – A principal should foster a shared vision in the school.

• 27 – A principal should have a vision for the school which they help to develop with colleagues.

Note that 26 – A principal should see themselves as ‘custodian’ of the school’s vision was largely preferred by leaders—78% of all preferences—in the first case and can be seen as ancillary to 24 and 27, both of which were statistically significant at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively, for leaders.

Table 5 gives the confidence levels for these three attributes.

Note that no other attributes were within the 5% confidence level for the combined, normalized sample.

Subsidiary attributes were:

• 28 – A principal should respect the views of students and teachers who help shape the school (statistically significant at the 1% level for students).

• 17 – A principal should maintain high expectations of teachers and students (statistically significant at the 5% level for leaders).

• 26 – A principal should see themselves as ‘custodian’ of the school’s vision (statistically significant at the 0.1% level for leaders).

Note that none of these subsidiary attributes were statistically significant at the 5% level for the combined sample but were for subsamples (see Supplementary Appendix 1).

Note also that these attributes come from three – related – styles, Integrated Leadership being a combination of Transformational Leadership and Instructional Leadership:

• Integrated Leadership – attributes 29, 27, 28, and 26.

• Transformational Leadership – attribute 24.

• Instructional Leadership – attribute 17.

Before looking more closely at the three top attributes let us revisit Integrated Leadership.

Revisiting Integrated Leadership

The integrated approach suggests that the principal operates simultaneously using transformational and instructional methodologies. As a transformational leader, the principal seeks to engage colleagues to foster higher levels of commitment from all members of the school community and in this way develop institutional capacity for school improvement (Murphy, 1990; Ololube, 2015). As an instructional leader, the principal collaborates with teachers to accomplish organizational goals for teaching and learning. The instructional leader engages at the technical and expert level but does so in such a way that they enthuse co-workers. This is an amalgam of expertise in the technical elements of educational leadership combined with the gravitas of referent authority. Transformational and shared instructional leadership are thus singular but complementary. When they operate contemporaneously, the leadership approaches are integrated. The energies of the principal are directed toward:

• developing the school mission and goals;

• coordinating, monitoring, and evaluating curriculum, instruction, and assessment;

• promoting a climate for learning; and

• creating a supportive work environment (Murphy, 1990).

Strong transformational leadership is critical in ensuring teacher commitment and teacher expertise (Marks and Printy, 2003). Such developments can lead to better outcomes:

… transformational leadership behaviors, such as idealized influence, inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation are positively related to greater employee acceptance, better performance, and increased job satisfaction at schools. Basically, these effects are vision building, high performance expectations, developing consensus about group goals and intellectual stimulation. Therefore, transformational leadership is very substantial for schools to move forward. (Balyer, 2012)

There is clear evidence that the principal can influence student outcomes through their impact upon their teachers. Principal style does much to influence the culture in the school for better or worse. Shepherd-Jones and Salisbury-Glennon (2018) looked at the influences of authoritarian, democratic, and laissez faire leadership styles upon teacher motivation. Their findings were that teacher motivation and, subsequently, the student experience in class were impacted by the perceptions of the principal’s competency. The level of job satisfaction enjoyed by teachers and the obvious “knock-on effect” for students has been directly linked to the methods employed by the principal. Rowland (2008) and Lai et al. (2011) found that teacher morale and teacher commitment were closely aligned with motivation and directly impacted by the practices of the principal. Leaders are not just there to get the work done but to provide meaning and purpose to those around them:

Transformational Leadership extends beyond the exchange of reward for work or accomplishment. It provides opportunity for the follower or worker to reach the higher-level need of self-actualization. (Rowland, 2008, p. 66)

A study by Woestman and Wasonga (2015, p. 11) found that “destructive behaviors directed at subordinates were found to be the most common and significant predictors of workplace attitude amongst professional educators.” Legros and Ryan (2015, p. 25) concluded that:

The principal is an integral component of the creation and sustainment of a school’s climate. The existence of a positive school climate is no longer a bonus of good leadership. It is the product of conscious leadership choices. Essentially, the way in which a principal chooses to lead determines whether or not a positive school climate will ensue.

School leadership has been identified as second only to teacher quality as an influence on student learning as found by Grissom et al. (2021) in their meta-analysis. Obviously, if this is the case, then principal quality must greatly influence the ultimate effectiveness of schools. A study by Leithwood et al. (2019) identified several practices that almost all successful leaders share to be successful in schools. These practices were divided into distinct groups around vision, relationships, culture, and enabling improvement through how the organization is ordered. Importantly how these practices were applied more so than the practices themselves were deemed to be of importance:

The most successful school leaders are open-minded and ready to learn from others. They are also flexible rather than dogmatic in their thinking within a system of core values, persistent (e.g., in pursuit of high expectations of staff motivation, commitment, learning and achievement for all), resilient and optimistic. (Leithwood et al., 2019, p. 10)

These practices would fit easily into any characterization of 21st century skills.

Leadership effectiveness, according to Leithwood (2005), was brought about by the leader who creates a compelling sense of purpose in their organization, in developing a shared vision for the future, helping build consensus, and demonstrating high expectations for their colleagues. Others (e.g., Browne-Ferrigno and Barber, 2010) place great value on the powers of collaboration.

In summary, principals, as people and leaders play an important role in the success of their schools that goes beyond the management decisions that they make. The behaviors they express and model to others, really do matter.

Looking at the Key Attributes in Detail

We now review the three top attributes, the statistically significant ones, starting with 29 – A principal should lead by example and is a good role model for colleagues and students which was also the top attribute in Part 1. While reviewing the top attributes we will also look more closely at how the subsidiary attributes fit in with them.

The Most Important Attribute From Both Part 1 and Part 2

Thus, the most important attribute of a principal is to act as a role model for students and colleagues.

We can unpack this in several ways. During a period of transition in education, it is reasonable to assume that students need to know what behaviors are required of them in the new context and it is also reasonable to assume that teachers need to know what new instructional practices they need to adopt. In both cases, it is the principal who can provide definitive answers, this is Instructional Leadership. To engender these changes in behavior amongst students and teachers requires the principal to be a Transformational Leader, inspiring the adoption of new behaviors. Combining these two forms of leadership give us Integrated Leadership and this expresses, in the first instance, as the principal acting as a role model, living the behaviors that are now desired among students, teachers and other school leaders.

This most important attribute also reflects the theorem put forward by Conant and Ashby (1970) in their paper entitled “Every good regulator [leader] of a system must be a model of that system.” The theorem implies that a principal must model the system, and, in the case of a school, the main elements of the system are students and colleagues. Thus, the principal must model what it is that the system is striving to achieve – the stance of leaders, the instructional practices of teachers and the desired behavior of students.

Finally, it should also come as no surprise that principals, as products of their systems themselves, may well model many (but potentially not all) of the behaviors they expect from both students and colleagues already; such behaviors having been inculcated in them during their own schooling and subsequent teaching career. However, first, if this attribute is not prioritized, it is possible for principal behavior to drift away under the day-to-day pressures of leading a school or for some behaviors to be neglected. Second, in a period of transition, current behaviors may not fully reflect desired future behaviors and instructional practices.

Thus, attribute 29 – A principal should lead by example and is a good role model for colleagues and students would indeed seem to be of paramount importance.

In education systems that are developing a wider range of skills and more adaptable behaviors than in the past raises two questions:

• What does it mean to be a good role model for students today?

• What does it mean to be a good role model for colleagues (i.e., teachers and school leaders) today?

These questions will now be explored.

What Does It Mean to Be a Good Role Model for Students Today?

The question of what it means to be a good role model for students is best interpreted in a wholistic sense. The principal models what it means to be a successful adult in the third decade of the 21st century. In this regard we should refer to 21st century skills such as those shown in Table 1. Twenty-first century skills build on but go beyond traditional skills and, ideally, the principal will model these new capabilities to students.

What does it mean to model? This question may best be answered through the concept of “teacherly authority,” a powerful concept, unique to humans, which affords cultural transmission (Stein, 2019). The basic mechanism is asymmetric, one person (“the teacher”) has a greater capacity than the other (“the student”) which is recognized and valued by the student who thereby accepts to pay attention to what the teacher is paying attention to. In the past the student may have paid attention to something of little intrinsic value through some form of coercion, but this is much less effective today, although not uncommon. That is the basic premise. What is sometimes missed is that teacherly authority affords cultural transmission and not simply transmission of subject knowledge and procedural skills.

Students recognize in the very best teachers that there are life lessons to be learnt – 21st century skills to be acquired – by being with and around such teachers and that the actual subject may be incidental, they will present their authentic selves and willingly do their best work because they want to continue in the best possible relationship to their teacher. Clearly, such a teacher must be competent in setting work, etc. but the hurdle of student engagement has already been overcome. It is in this context that principal role modeling should be placed. The principal is a “teacherly authority” embodying and transmitting the cultural values that the school is trying to develop in its students.

If the principal is acting as a “teacherly authority” then this stance is a “system skill” that the principal will want all staff to adopt and provide to students so that students can acquire the broad range of skills that they need as they develop toward adulthood.

As Corrigan (2020) has pointed out, about 60% of teachers are disengaged from their work (consistent with disengagement levels in many other sectors and across countries) and thus their “teacherly authority” is much diminished. In these cases, students do not present their authentic selves and may only grudgingly apply themselves to set work. This reduces the level of outcomes that might be achieved. Note that many adults who are disengaged from their work are still hard working; disengagement in this context means not bringing additional skills – which boost “teacherly authority” – to bear in their work.

This need for modeling by all teachers also explains why 28 – A principal should respect the views of students and teachers who help shape the school (statistically significant at the 1% level for students) is important. If a teacher is disengaged then, by definition, they treat some or all students as objects (tasks to be completed, problems to be solved), not as subjects, with their own rich internal lives and untapped capacities. Respecting the views of students (and teachers) implies treating them as people, as subjects. For all staff to do this then principal modeling of this behavior becomes essential. Note that treating students as compliant objects was the norm in education in the past so that this shift—from student as object to student as subject—is a substantive one and unlikely to be achieved without explicit recognition, modeling, and development pathways put in place to achieve it, in other words the need for key elements of Transformational Leadership.

Further, this explains why 17 – A principal should maintain high expectations of teachers and students (statistically significant at the 5% level for leaders) is important. Unless all teachers and students are engaged, the school will run less effectively than it might and, for example, issues, rather than being resolved in the classroom, can escalate to take up the time and attention of leaders, distracting them from more important activities.

To summarize, we can now see why the principal acting as a role model was rated as the most important leadership attribute by respondents to the survey. To prepare students for the world as it is now and for the foreseeable future students need to develop 21st century skills. To do this they need to be with teachers who are engaged in their work and modeling these skills. For that to be uniformly the case across a school, the principal must prioritize role modeling to students, teachers and leaders.

Further, to achieve the state whereby all teachers are modeling these skills to students under current conditions (where many teachers are not engaged), implies the need for effective development to be in place. Such development would help disengaged teachers overcome the obstacles to their full engagement, boost their “teacherly authority” and encourage the widespread development and expression of 21st century skills. These forms of development—focusing on self-management—are rarely seen in schools and are complementary to the development of capabilities in the areas of curriculum and pedagogy.

Thus, if being a role model for students is important then taking this leadership attribute seriously can potentially have a sustained long-term impact on school success by improving the level of teacher engagement and “teacherly authority” and improving the level of take-up of 21st century skills among students. It becomes clear why this attribute is seen to be of such importance.

What Does It Mean to Be a Good Role Model for Colleagues (Teachers and School Leaders) Today?

To ensure students acquire 21st century skills and the subject knowledge and procedural skills to become effective adults, teachers need to be effective teachers of their subject areas and have appropriate levels of “teacherly authority.” Leaders need “teacherly authority” to an even greater degree.

Schools habitually focus on developing curriculum and effective pedagogies so that the modeling provided by the principal is more likely to be focused on how staff further acquire and grow their “teacherly authority.” Obviously, the principal would model that being a teacher means being fully engaged and continually learning new skills. Being passionate and committed to one’s profession is a given. Modeling to teachers and leaders also includes displaying high degrees of self-management, the ability to consider and choose a constructive response when challenged – indeed to face challenges with equanimity – and the ability to listen carefully to others so that they, in turn, feel listened to, feel heard and valued (Corrigan, 2019).

Corrigan (2020) has pointed out that there are only a small number (about 5%) of teachers [what Corrigan (2020) terms “Enlightened Teachers”] who can cause students to present their authentic selves and willingly do their best work, and that such teachers have a life-long impact on their students. Corrigan (2020) has “often asked principals: “What would your school be like if, rather than having five percent of Enlightened teachers, you had 25 per cent?” The answer has always been the same: it would transform their school for the better.”

Growing the percentage of “enlightened” teachers and leaders would substantively raise student engagement levels and student outcomes in both measurable and less tangible ways.

Thus, a principal should role model what it means to be a highly effective teacher, including the capacity to cause students to present their authentic selves and willingly do their best work. The pool of teachers who can do this without further development is small, further emphasizing the need for Integrated Leadership.

A Question of Vision: The Two Attributes Making Up the Top Three

According to Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric from 1982 to 2001, “Good business leaders create a vision, articulate the vision, passionately own the vision, and relentlessly drive it to completion” (Tichy and Charan, 1989). It is probably unsurprising, then, that the two other attributes that made up the top three both related to “vision”:

• 24 – A principal should foster a shared vision in the school.

• 27 – A principal should have a vision for the school which they help to develop with colleagues.

The attribute 26 – A principal should see themselves as “custodian” of the school’s vision (statistically significant at the 0.1% level for leaders) is also linked to these two attributes. Given that the design of this survey was based on principal styles, it is unsurprising that some attributes may be related. Thus, it would be reasonable to consider these three attributes to be facets of a single attribute. Together, these would identify “vision,” its development, fostering, and careful safeguarding of key importance.

The links between these three attributes is evident. Fostering a shared vision implies that a key role of a principal is to be clear about where the school is going, and that this vision is shared widely among the school community and beyond. Further, the vision that is being fostered is one that has been developed with school colleagues and thus has high buy-in from those who will be using it daily to shape their decisions. The custodianship attribute implies that the vision is carried forward without any loss or degradation of the key elements.

A vision is a vivid mental image of what a leader wants their school to be at some point in the future. A vision becomes a practical guide for creating plans, setting goals and objectives, making decisions, and coordinating and evaluating the work on any project, large or small. A vision helps keep the school community focused and together, especially with complex projects and in stressful times.

To foster a shared vision implies that the principal passionately owns the vision, can articulate both the vision and their passion for it to many different audiences, and ceaselessly maintains the vision as an achievable future state for the school and its community. As with the top attribute (i.e., being a role model), many current principals will have a vision for their school which may range from being a simple continuation of the school’s past through to being a fully fledged mental image of their school developing all students with 21st century skills underpinned by the specific steps to achieve this. Today, given the transition that is taking place from traditional skills to 21st century skills, the vision will need to be more toward the latter end of this range than the former.

Developing such a vision in collaboration with colleagues is an order of magnitude more difficult than a continuation of the past and may take some considerable time and effort—and potentially several iterations—as the principal and their staff increase their own understanding of what the future might be like and the necessary steps to get there. Thus, it is not surprising that developing and fostering a vision is given a high priority, a priority only exceeded by the need to be a role model for students and teachers.

In summary, most schools will have a vision statement of some kind. Not all such statements will be fully aligned with the need to develop young people with a broader range of skills and the implications for staff development which that entails.

The Top Attributes Together

Combining the top attributes—29 – A principal should lead by example and is a good role model for colleagues and students, 24 – A principal should foster a shared vision in the school, 27 – A principal should have a vision for the school which they help to develop with colleagues, and 26 – A principal should see themselves as “custodian” of the school’s vision—has important ramifications.

A first implication is that the principal is modeling to colleagues and students the behaviors and instructional practices that are contained, explicitly or implicitly, in the vision for the school, and therefore are affirmed by the colleagues who have been involved in creating the vision. Thus, the choice of behaviors expressed by the principal is not a personal one but is guided by the vision that has been adopted by the school.

Second, to ensure the adoption of new behaviors and practices requires a principal to have or to develop the capacity to inspire or otherwise engender behavioral change in both staff and students.

Effective principals orient their practice toward instructionally focused interactions with teachers, building a productive school climate, facilitating collaboration and professional learning communities, and strategic personnel and resource management processes. (Grissom et al., 2021)

It is the quality of the interactions with stakeholders and the ability to engage meaningfully which is the measure of principal impact and effectiveness.

In the case where a school’s vision is not adequate to furnish young people with the skills needed today, then the role of the principal is to set in train a broad-based process to develop an adequate vision and, if necessary, modify their own behavior to match what is needed to bring that vision into concrete existence. Without the principal’s consistent role modeling and inspiration, day-to-day behaviors will never achieve, or will drift away from, those implied in the vision.

These behaviors belong to the Integrated Leadership style of leadership.

Discussion

The behaviors that a principal is modeling to their colleagues and students have an impact on the ongoing success of a school. When these actions and behaviors are appropriate and consistent over time this impact can be very positive (Rowland, 2008; Browne-Ferrigno and Barber, 2010; Lai et al., 2011; Shepherd-Jones and Salisbury-Glennon, 2018; Leithwood et al., 2019).

What this study is showing is that the behaviors to be consistently expressed by the principal faithfully reflect the skills and behaviors that the school community have determined—through a vision, carefully fostered and promoted by the principal—that they want to see developed in their students and, with this end in mind, modeled by their teachers and school leaders.

The findings of this study indicate a departure from the past; we are no longer seeking compliant behavior but adaptable behavior. This shift from developing traditional skills and compliant behaviors to developing 21st century skills and more adaptable behaviors is not simply a question of changing the curriculum but is, in addition, a question of developing new behaviors throughout a school. This study shows that such a development must be led by the principal whose leadership is expressed by modeling the behaviors embodied in the school’s vision, a vision developed by the school community, that is fostered and passionately held by the principal.

Under traditional schooling models, teachers are obliged to manage a class and transfer the requisite knowledge and skills to their students, as determined by the curriculum. Historically, there has been no requirement to treat students as other than objects—problems to solve or tasks to complete—which is necessarily the case where compliance is being demanded and a majority of teachers still take this stance. Of course, most teachers are hardworking and committed to their role, they are simply doing what they believe the system requires of them. However, times have changed and what the new system requires has not been made sufficiently explicit to engender changes in teachers’ behavior.

A transition to 21st century skills implies the principal modeling these skills and requiring that all teachers do the same; a departure from past behaviors. Modeling these skills implies engagement, which in turn implies treating students as subjects. When we treat someone as a subject rather than an object it means we can have a two-way relationship with them.

It is this shift from disengagement to full engagement that is the most difficult. A principal can lead an inclusive process to develop a vision that sees a school developing these skills in all its students, and the same leader, or another, models 21st century skills and is passionate about the vision. The stumbling block is how to engage every teacher when that engagement means a substantive shift in behavior from historic norms vis-à-vis students, colleagues, and the nature of their work. These changes in behavior are not simply a choice: today I will not be curious or show initiative, tomorrow I will do both; today I will treat most of my students as objects, tomorrow I will treat them as subjects. These are deep-seated changes which take time and consistent effort to effect. The principal can model these behaviors and passionately extol the school’s vision but, in addition, there must be development pathways that support teachers in undergoing the hard work of self-transformation, of removing the learned behaviors that stifle the human tendency to be curious, to show initiative, and to engage with other people as people.

Implications for the School Governing Body

The outcome of this study implies that a School’s Governing Body must assure themselves that school staff and leaders are very clear about what sorts of students the school wants to develop, what sorts of instructional practices are needed to achieve that outcome, and thus what skills and behaviors they want reflected in the school’s teachers and leaders. If they can assure themselves that this vision for the school is adequate, then they must further assure themselves that the principal is modeling behaviors consistent with this vision as well as extolling its virtues. Finally, they must assure themselves that behaviors and practices amongst staff are changing over time to come more into alignment with the school’s vision, and the desired outcomes for students are being progressively achieved.

In the event that a school lacks vision; either due to the absence of a clear mission statement, uncertainty at the governing level or due to insufficient induction of key leaders, then the Governing Body has both a significant challenge and a potential opportunity for reset and renewal. If the vision of the school is not clear, then the Governing Body must task the principal to lead a broad-based process to develop a clear and adequate vision for the school and assure themselves that, once developed, the principal is willing and able to commit fully to modeling the behaviors embedded in the vision and to act as a passionate custodian for it. The challenges of a school ‘lacking charts, a course to steer and a skillful navigator’ is the potential for future study.

In the circumstance where the school community cannot collectively agree on a vision for the school then the principal must build and support the capacity required such that an agreed vision can be achieved at some point in the future. Institutional capacity building is an important aspect of the Integrated Leadership style (Ololube, 2015).

In the case where a school has already developed an adequate vision then the role modeling of the implied behaviors and the capacity to inspire behavioral change amongst staff and students should be important factors in the Governing Body’s recruitment of a new principal or the ongoing evaluation of an existing principal.

During periods of stability, the above conditions may naturally align. It is during periods of transition that care needs to be taken to assure that each individual condition is met, and a new alignment achieved.

Implications for the Aspiring Leader

In the first instance, aspiring leaders need to align themselves with the mores and values of the organizations they wish to lead to the extent that they can consistently model the associated behaviors and inspire others to adopt them as well. For some, existing behaviors are so entrenched that even with knowledge of the prevailing institutional mores, they just cannot help but default to their personal values compass, which may prove to be a mismatch and their tenure unsuccessful. A better understanding of the key attributes needed of a principal in this time of change can allow aspiring leaders to better prepare to take on the principal role. The match between leader and school needs to be authentic. The leader modeling the attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs cherished by the organization, and sharing these attributes in turn, reinforces and grows them within the institution. The aspiring leader’s responsibility is to fully understand the school they wish to lead.

In some cases, there is the potential for maximum leadership impact if the principal can model those qualities to which the school aspires but is currently falling short. In these cases, it is not just the qualities but also the ability to inspire others which are the critical factors.

Aspiring principals also need an appreciation not only of their own skills but also of their own world view. Sadly, it can be the case that aspiring leaders have an unrealistic self-awareness and, in their ignorance, fail to see that they have neither the attributes nor the skill required to lead.

The aspiring leaders most likely to succeed will be those for whom new behaviors are relatively close to their current behaviors, meaning that they already model 21st century skills, they respect all staff and students—treat them as subjects rather than objects—they have the capacity to cause students (and staff) to present their authentic selves and willingly do their best work, and expect this high standard from everyone they meet.

Developing aspiring leaders along these lines would go some way to preparing them to take on a principal’s role in the future.

Implications for Existing Principals

Most principals would likely agree on the traits of good leadership, but such agreement does not necessarily translate into principal behaviors. This study suggests that the principal ought to be spending most of their time and energy on two things. It is ensuring that the school’s vision is up to date with contemporary needs, they are aligned with it and promoting it exhaustively, and that they are modeling the skills and behaviors that their school wants to see in students, teachers and leaders, and they are inspiring behavioral change, that are paramount. Here model means literally to live by and consistently express the skills that are integral to the vision—to be creative and adaptive, to be curious, to show initiative, to be collaborative and communicative—exactly the capabilities that society wants students to have, but the principal needs to have them to a high degree.

The strength of the responses in this study suggests that the principal ought to put considerable time and energy into these specific domains. Being handy with the paperwork or prolific with emails might be admirable traits, but these are not the things which colleagues and students are using to measure the value of the principal, not the things that will have a lasting impact on the school’s outcomes. Modeling contemporary skills and behaviors and inspiring others to adopt them is where the principal can have the greatest impact, and where their efforts are best placed, not forgetting that what is being modeled must be derived from and enshrined in the school’s vision. What we want to be and how we behave need to be consistent.

Hopefully, existing principals will be interested in the results of this study and reflect on their school’s current vision and how they spend their time in and around the school.

Conclusion

It would be fair to say that the expectation of the authors of this study was to find differences in the tactical approach to being a principal, for example between being more authoritarian or less. What was surprising was the strategic nature of the attributes that have been found to be most important and that these are concentrated in the Integrated Leadership style.

To lead by example and act as a role model for colleagues and students is not a personal preference nor a matter of style but is rather a strategic choice. What is modeled comes out of a process that creates and disseminates a long-term vision of the future, a process fostered by the principal. In other words, what the principal is modeling is what the school community has collectively agreed is where they want to see the school in the future.

It is the principal who is both the enabler of this vision and the guardian of it through modeling the key “system skills” to colleagues and students and passionately advocating for this future within and beyond the school community.

This study can assist school governing bodies in what to look for during the appointments process, inform principals about where they need to be spending their time and energies, and clarify to aspiring principals what they need to develop in themselves to become suitable to lead schools.

Much research has rightly concentrated upon teacher quality as the educational landscape continues to shift from a 20th century industrial model of education to a model based upon the nurturing of 21st century skills. Where there has been less research is around how deep-seated behaviors can be shifted to match new needs. What we should not lose sight of is the work of the school leader in creating, nurturing, and promoting an environment and set of development processes for staff where the needed qualities can grow and flourish.

This study opens the possibility of the education sector placing a greater focus on the cultural aspects of the shift to 21st century learning and, hopefully, encouraging a greater research effort in this area both theoretically and in the practical aspects of engendering the changes described herein.

There are significant positives emerging from this study.

First, it is evident that students and teachers agree on what good leadership looks like. Further, they seek this leadership from their principals. Second, having a clear vision for a school is the foundation for creating better outcomes. These outcomes are best assured by the principal modeling the behaviors embedded in this vision as well as passionately extolling the vision within and beyond the school community. Third, schools can align leadership with the institution and its desired direction and outcomes. Fourth, good leadership can be quantified. Fifth, schools can grow through the appointment of a leader who has the right qualities and who can bring the community along with them.

These are powerful and clear outcomes applicable to schools in virtually any context and reflect the nature of the underlying changes in the development that we are seeking for our young people.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MM conducted the literature search and development of the list of principal attributes. JC developed and administered the survey and conducted the data analysis. Both authors contributed to the discussion and conclusions.

Funding

This study received funding from Yarra Valley Grammar, Melbourne, Australia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the principals, staff, and students of the nine schools invited to take part in the online survey: Assumption College, Camberwell Grammar, Ivanhoe Grammar, Marcellin College, Mentone Grammar, Peninsula Grammar, Penleigh and Essendon Grammar, Trinity Grammar, and Yarra Valley Grammar, all members of the Associated Grammar Schools of Victoria (AGSV) in Australia.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.897620/full#supplementary-material

References

Balson, M. (1992). Understanding Classroom Behaviour. Camberwell, Victoria: Australian Council of Educational Research (ACER).

Balyer, A. (2012). Transformational Leadership Behaviours of School Principals: a Qualitative Research Based on Teachers’ Perceptions. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 4, 581–591.

Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M., et al. (2012). “Defining Twenty-First Century Skills,” in Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills, Chap. 2, eds P. Griffin, B. McGaw, and E. Care (Dordrecht: Springer).

Botha, R. J. (2004). Excellence in Leadership: demands of the Professional School Principal. S. Afr. J. Educ. 24, 239–243. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2019.1611429

Browne-Ferrigno, T., and Barber, M. (2010). Successful Principal-Making Collaborations: From Perspective of a University Partner. Denver, CO: The American Educational Research Association.

Cascadden, D. S. T. (1996). Principals as Managers and Leaders: A Qualitative Study of the Perspectives of Selected Elementary School Principals. Ph.D. thesis. Virginia: William & Mary, doi: 10.25774/w4-dpx0-6d52

Conant, R. C., and Ashby, W. R. (1970). Every Good Regulator of a System Must be a Model of that System. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1, 89–97. doi: 10.1080/00207727008920220

Costellow, T. D. (2011). The Preferred Principal: Leadership Traits, Behaviors, and Gender Characteristics School Teachers Desire in a Building Leader. Ph.D. thesis. Bowling Green, KY: Western Kentucky University.

Diaz-Saenz, H. R. (2011). “Transformational Leadership,” in The SAGE Handbook of Leadership, eds A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, and M. Uhl-Bien (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 299–310.

French, J. R. P. Jr., and Raven, B. H. (1959). “The Bases of Social Power,” in Studies in Social Power, ed. D. Cartwright (Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research), 150–167.

Griffin, P., McGaw, B., and Care, E. (2012). “The Changing Role of Education and Schools,” in Assessment and Teaching of 21st Century Skills, Chap. 1, eds P. Griffin, B. McGaw, and E. Care (Dordrecht: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2324-5

Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., and Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research. New York: The Wallace Foundation.

Hallinger, P. (1992). The evolving role of American principals: from managerial to instructional to transformational leaders. J. Educ. Adm. 30, 35–48. doi: 10.1108/09578239210014306

Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional Leadership and the School Principal: a Passing Fancy that Refuses to Fade Away. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 4, 221–239. doi: 10.1080/15700760500244793

Kars, M., and Inandi, Y. (2018). Relationship between School Principals’ Leadership Behaviours and Teachers’ Organizational Trust. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 74, 145–164.

Lai, T. T., Luen, W. K., and Hong, N. M. (2011). “School principal leadership styles and teachers organizational commitment: a research agenda,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Economic Research (2nd ICBER 2011), 165–172.

Legros, I., and Ryan, T. G. (2015). Principal traits and school climate: is the invitational education leadership model the right choice? J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Pract. 31, 14–29. doi: 10.26522/jitp.v7i1.3841

Leithwood, K. (2005). Understanding Successful Principal Leadership: progress on a Broken Front. J. Educ. Adm. 43, 619–629. doi: 10.1108/09578230510625719

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2019). Seven Strong Claims about Successful School Leadership Revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 40, 5–22. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

Lewis, R. (1997). The discipline dilemma: control, management, influence. Camberwell, Vic: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Lovegrove, M. N., and Lewis, R. (1991). Classroom discipline. South Melbourne Australia: Longman Cheshire.

Marks, H. M., and Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal Leadership and School Performance: an Integration of Transformational and Instructional Leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 39, 370–397. doi: 10.1177/0013161X03253412

Merry, M. (2009). Building a Boy Friendly School: The educational needs of boys and the implications of school culture. Ph.D. thesis. Melbourne: Latrobe University.

Murphy, J. (1990). Instructional Leadership: focus on Curriculum Responsibilities. NASSP Bull. 74, 1–4. doi: 10.1177/019263659007452502

Ololube, N. (2015). A Review of Leadership Theories, Principles and Styles and Their Relevance to Educational Management. Management 5, 6–14. doi: 10.5923/j.mm.20150501.02

Printy, S. M., Marks, H. M., and Bowers, A. J. (2009). Integrated Leadership: how Principals and Teachers Share Transformational and Instructional Influence. J. Sch. Leadersh. 19, 504–532. doi: 10.1177/105268460901900501

Rowland, K. (2008). The Relationship of Principal Leadership and Teacher Morale, Faculty of the School of Education. Lynchburg, Virginia: Liberty University, USA.

Sebastian, J., Huang, H., and Allensworth, E. (2017). Examining Integrated Leadership Systems in High Schools: connecting Principal and Teacher Leadership to Organizational Processes and Student Outcomes. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 28, 463–488. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2017.1319392

Sharma, L., and Singh, S. (2013). Characteristics of Laissez-Faire Leadership Style. A Case Study. CLEAR Int. J. Res. Commer. Manag. 4, 29–31. doi: 10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015.41.2003

Shepherd-Jones, A., and Salisbury-Glennon, J. (2018). Perceptions Matter: the Correlation between Teacher Motivation and Principal Leadership Styles. J. Res. Educ. 28, 93–131.

Skogstad, A., Einarsen, S., Torsheim, T., Aasland, M., and Hetland, H. (2007). The Destructiveness of Laissez-Faire Leadership Behavior. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 12, 80–92. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.1.80

Stein, Z. (2019). Education in a Time Between Worlds: Essays on the Future of Schools, Technology, and Society. San Francisco Bay Area: Bright Alliance.

Tichy, N., and Charan, R. (1989). Speed, Simplicity, Self-Confidence: An Interview with Jack Welch. HBR Magazine. Boston: Harvard Business Publishing.

Woestman, D., and Wasonga, T. (2015). Destructive Leadership Behaviours and Workplace Attitudes in Schools. NASSP Bull. 99, 147–163. doi: 10.1177/0192636515581922

Woods, P. (2020). Democratic Leadership. Oxford Encyclopedia of Educational Administration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.609

World Economic Forum [WEF] (2015). New Vision for Education: Unlocking the Potential of Technology. Cologny: World Economic Forum.

Keywords: school principalship, principal attributes, leadership styles, integrated leadership, principal as role model, teacherly authority

Citation: Corrigan J and Merry M (2022) Principal Leadership in a Time of Change. Front. Educ. 7:897620. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.897620

Received: 16 March 2022; Accepted: 25 April 2022;

Published: 11 May 2022.

Edited by:

Jennie Weiner, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Mariela A. Rodriguez, University of Texas at San Antonio, United StatesDana Jackson, University of Richmond, United States

Copyright © 2022 Corrigan and Merry. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mark Merry, bWFyay5tZXJyeUB5dmcudmljLmVkdS5hdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

John Corrigan

John Corrigan Mark Merry

Mark Merry