- 1Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

- 2School of Optometry, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, Canada

- 3Department of Chemistry, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Introduction: Academic writing is a core element of a successful graduate program, especially at the doctoral level. Graduate students are expected to write in a scholarly manner for their thesis and scholarly publications. However, in some cases, limited or no specific training on academic writing is provided to them to do this effectively. As a result, many graduate students, especially those having English as an Additional Language (EAL), face significant challenges in scholarly writing. Further, faculty supervisors often feel burdened by reviewing and editing multiple drafts and find it difficult to help and support EAL students in the process of scientific writing. In this study, we explored academic writing challenges faced by EAL doctoral students and faculty supervisors at a research intensive post-secondary university in Canada.

Methods and Analysis: We conducted a sequential explanatory mixed-method study using an online survey and subsequent focus group discussions with EAL doctoral students (n = 114) and faculty supervisors (n = 31). A cross-sectional online survey was designed and disseminated to the potential study participants using internal communications systems of the university. The survey was designed using a digital software called Qualtrics™. Following the survey, four focus group discussions (FGDs) were held, two each with two groups of our participants with an aim to achieve data saturation. The FGD guide was informed by the preliminary findings of the survey data. Quantitative data was analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) and qualitative data was managed and analyzed using NVivo.

Discussion: The study findings suggest that academic writing should be integrated into the formal training of doctoral graduate students from the beginning of the program. Both students and faculty members shared that discipline-specific training is required to ensure success in academic writing, which can be provided in the form of a formal course specifically designed for doctoral students wherein discipline-specific support is provided from faculty supervisors and editing support is provided from English language experts.

Ethics and Dissemination: The general research ethics board of the university approved the study (#6024751). The findings are disseminated with relevant stakeholders at the university and beyond using scientific presentations and publications.

Introduction

The international student population at Canadian Universities is on the rise. Statistics Canada reported that over the past 10 years, between 2008/2009 and 2018/2019, enrollments for Canadian students in formal programs grew by 10.9% whereas number of international students tripled over the same period (Statistics Canada, 2020). The same report highlighted those international students contribute an estimated 40% of all tuition fees collected by Canadian universities, accounting for almost $4 billion in their annual revenue in 2018/2019 (Statistics Canada, 2020). Not only international students contribute toward the tuition revenue of universities, but they also increase the social and cultural diversity of campuses leading to excellence in scientific achievement and innovation. The heterogeneity and diversity of graduate students contribute toward globalization of universities and enhance quality of educational experiences for all students (Campbell, 2015).

Academic writing is one of the core elements of a successful graduate program, especially at the doctoral level (Itua et al., 2014). The ability to present information and ideas in writing plays an integral role in graduate students’ academic and professional success (Caffarella and Barnett, 2000; Aitchison et al., 2012). Research has shown that writing process is related directly with the doctoral students’ identity development and is not just can be seen as a skill acquisition but a socio-cultural tool that need to be learnt. In fact, in many cases it is a socially situated process that happens in social discourses and is based on intensive interactions with the text and scientific communities. The process eventually leads to the development of an academic identity of graduate students which determines expression of a scientific arguments, epistemologies, methodologies, and theoretical approaches that they align with and adopt as they grow into scientists (Lee and Boud, 2003; Sala-Bubaré and Castelló, 2018; Inouye and McAlpine, 2019; Lonka et al., 2019). The complexity associated with scholarly writing is further compounded at the doctoral level due to the expectation of systematic understanding and comprehensive knowledge of the field of study, mastery of research methods associated with that field, and ability to communicate the complex ideas with the peers, the larger scholarly community and society in general (Inouye and McAlpine, 2019). This process can be challenging to even native speakers, meaning that non-native English speakers may face not only problems with grammar, idea expression, etc., but this may lead to low self-esteem of doctoral students, especially those with English as an additional language (EAL), and interfere with their researcher identity and authorial voice development.

Many EAL doctoral students face numerous scholarly writing challenges (Pidgeon and Andres, 2005). Previous research highlights that international students navigate a complex cultural adaptation like institutional, departmental, disciplinary, and individual culture (Ismail et al., 2013). The internationalization of higher education enhances academic writing’s intricacies, challenging international students and their supervisors to tackle differences in English language understanding and proficiency (Doyle et al., 2018). Previous research also suggests that academic writing practices are socio-culturally specific and subject to change for academic disciplines (Abdulkareem, 2013). Second language learners need more time to gain similar understanding levels than first language learners (Ipek, 2009). Individuals from a variety of disciplines and parts of the world adopt dissimilar rhetorical writing styles, with some preferring inductive forms while others prefer deductive styles. Writing styles also reflect specific cultural nuances that are not applicable or employed in different parts of the world.

Not only students, but faculty supervisors who supervise graduate students often feel burdened of reviewing and editing multiple drafts; and find it hard to help and support students in the process of scientific writing (Maher et al., 2014). Furthermore, the university centers that provide services to support students develop their writing skills face difficulties in matching services according to the supervisor’s expectations (McAlpine and Amundsen, 2011; Gopee and Deane, 2013). While extensive scholarly attention has been given to the challenges of doctoral studies, research directed toward understanding the challenges in academic writing from the perspectives of doctoral students and their graduate supervisors at Canadian institutions has been very limited (Pidgeon and Andres, 2005; Jones, 2013). The goal of this study was to understand the challenges in academic writing faced by EAL doctoral students and graduate supervisors at a research-intensive post-secondary institution. To achieve our research goal, we had two main objectives:

1. Understand academic writing challenges from the perspectives of EAL doctoral students, knowledge and use of existing services, and writing support from supervisors.

2. Explore areas for support and services needed to improve academic writing, from the perspectives of EAL doctoral students and faculty supervisors with graduate supervision responsibilities and experience.

Understanding these challenges will inform the mechanisms adopted by Canadian or other universities across the world to strengthen the existing services and development of an academic writing model that support graduate students and their supervisors toward successful academic writing.

Materials and Methods

The project was undertaken at a research-intensive post-secondary university in Canada. This university is one of the Canada’s renowned universities that has been granting graduate degrees for over 130 years, and currently offers more than 125 graduate programs to over 4,200 graduate students. Figures from the university suggest that, in 2017, international students from 80 different countries across the world comprised 26% of the total graduate student population. This project was funded by an educational research grant provided by Centre for Teaching and Learning and was a collaborative effort among key stakeholders concerning graduate students, faculty, and staff at the university. These stakeholders included members of the School of Graduate Studies, university’s International Centre, Student Academic Success Services, Centre for Teaching and Learning, and Society for Graduate and Professional Students that provided guidance at every stage of the research process.

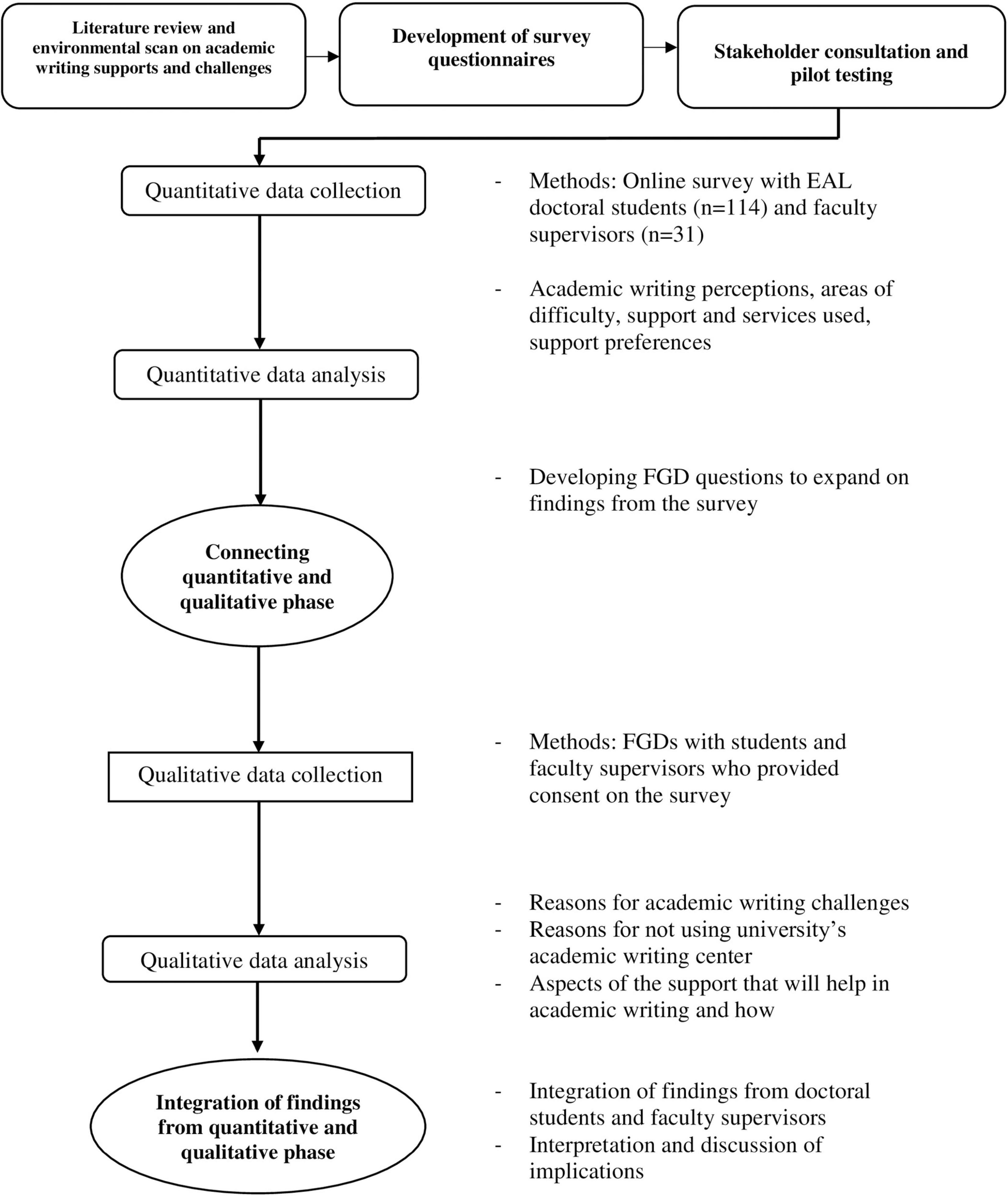

A mixed-method approach with sequential explanatory design was used, wherein quantitative data was collected first followed by qualitative data. Participants belonged to major academic disciplines at the university which included science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics.

Study Participants

The study participants included doctoral students doing PhD at the university who were non-native English language speakers and in any year of their program and faculty supervisors with experience of supervising EAL doctoral students. The non-probability sampling was used wherein participants were invited to participate in the study voluntarily. The eligibility to participate in the study was self-determined by the participants.

Doctoral Students

A total of 114 students participated in the study. The average age of doctoral students who responded the survey was 31 years, ranging between 23 and 51 years. Out of 114, 47 students identified themselves as male (41%), 63 identified as female (55%), and four (4%) chose not to declare. With regards to ethnic origin and native languages, there was a large heterogeneity within the sample. Participants belonged to ten different ethnic backgrounds, and thirty-four different languages were reported as their native spoken language. The most indicated racial/ethnic backgrounds were South Asian (22%) and Middle Eastern (18%) followed by European (16%), and Chinese (15%). Four most commonly represented native languages were Arabic (12%), Farsi (9%), Mandarin (9%), and Spanish (6%). Most of the students belonged to Arts and Science (26%), followed by Health Sciences (21%), Engineering (20%), School of Business (13%) and Education (6%). Majority of students who completed the survey were in their first year of PhD program (38%). The remainder of the respondents were almost evenly distributed amongst second year (14%), third year (15%), fourth year (17%) and upper year (16%). With regards to the stage of PhD studies; 48% of respondents were commencing PhD studies, 28% of respondents were mid-candidature, and 24% of respondents were completing PhD studies at the time of the survey.

Faculty Members

A total of 31 faculty members participated in the study. Out of 31, almost half were females. In terms of their faculty ranks, 48% identified as associate professor, 36% as professor, 16% as assistant professor. The number of years of experience of participant supervisors with graduate supervision ranged from 1 to 35; with 45% of respondents having 11–15 years of experience supervising graduate students. Majority of the respondents had supervised less than 10 doctoral students, with 2 EAL doctoral students on an average (46%).

Data Collection and Analysis

The general research ethics board of the university approved the study (#6024751). The data was collected over a period of 6 months, from January to June 2019.

Quantitative Data

Two cross-sectional online surveys were designed and disseminated to the potential study participants (EAL doctoral students and faculty supervisors) using internal communications systems of the university. The surveys were designed using a digital software called Qualtrics™ and developed based on the literature and an environmental scan of academic writing support across ten universities in Canada. The environmental scan helped us to identify the extent and nature of support and services in Canadian universities such as a dedicated academic writing center, online resources for academic writing, personal consultation services for academic writing, workshops/seminars/other events dedicated to academic writing, and resources specific to EAL graduate students and supervisors. The instruments were validated through expert consultation and pilot testing with four potential participants (Supplementary Materials 1, 2). We followed the general recommendations of anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality from ethical practice guidelines for online research (Gupta, 2017). Quantitative data was analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS). All continuous variables are presented as mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range). Dichotomous variable values are presented as proportions/percentage.

Qualitative Data

Following the survey, four FGDs were held, two each with two groups of our participants with an aim to achieve data saturation. A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the objectives of the study and the key findings obtained from the quantitative phase of the study (Supplementary Material 3). Participants for focus group discussions (FGDs) were recruited from the pool of survey respondents who agreed to participate in the qualitative phase of the study. The FGD guide was pilot tested with two participants and revised in light of their responses. The focus groups were conducted in-person. FGDs were conducted by the first author, who was a EAL PhD candidate at the time. All FGDs lasted between 40 and 60 min and were recorded using two audio-recorders and transcribed verbatim. To maintain anonymity, all personal identifiers were removed before data analysis.

Inductive thematic analysis approach was used for qualitative data which involved identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes that are important in the phenomenon of being investigated (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The coding process in inductive thematic analysis started with the preparation of raw data files after data cleaning; close reading of the text to understand the content; the identification and development of general themes and categories; the re-reading to refine the categories and reduce overlap or redundancy among the categories; and creating a framework incorporating the most important categories (Guest et al., 2014) (Supplementary Material 4). The first two authors (SG, AJ) coded the four transcripts independently to ensure inter-coder consistency and peer examination of the codes developed by the first author. The coding scheme was confirmed and corrected by the senior author (JK) for any imprecise code definitions or overlapping of meaning in the coding scheme. Eighty percent of the total codes were identified within the first two FGDs. Two more FGDs were conducted to confirm thematic saturation in data. These additional FGDs verified that saturation is based on the widest possible range of data on the emerged subcategories. This process increased the comprehensibility of analysis and provided a sound interpretation of the data. The NVivo software was used to manage the data. Research rigor was ensured through an audit trail and peer debriefing (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). For an audit trail, a logbook was maintained that contained the notes on the data collection process, the analysis process, and the final interpretations. The research team met at regular intervals to provide critical inputs on the research methods and lead researcher’s interpretation of meanings and analysis. The peer-review process involved deliberations and debriefing of the emerging codes, categories, and their relationship with the data.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative data

Using the mixed-methods sequential explanatory design, the quantitative and qualitative data was connected at the intermediate stage when results obtained from the quantitative data analysis informed data collection of the qualitative study and guided the formation of the semi-structured interview guide. The quantitative and qualitative studies were also connected while selecting the participants for the qualitative study and conduct follow-up analysis based on the quantitative results. The development of the qualitative data collection tool was grounded in the results from the quantitative study to investigate those results in more depth through collecting and analyzing the qualitative data. Finally, an overall interpretation was framed, which is presented in this paper, and implications of the integrated findings on future research, policy and practice are discussed. Figure 1 describes this process and depicts the various stages of integration, along with the specific aspects of this research that were explored in subsequent phases or informed the subsequent phase.

Results

Findings From the Online Survey and Focus Group Discussions

Doctoral Students

Academic Writing Challenges

Out of total respondents, almost 90% doctoral students felt that they need to improve their academic writing skills and 46% indicated that a university supervisor or faculty has at some point indicated that they need to work on improving their academic writing skills. The highest rated areas of difficulty were the writing process (25%), followed by developing content/ideas (24%), use of grammar (16%) and vocabulary (12%), and the organization of sentences or paragraphs (11%).

When explored further over a focus group discussion, the students provided reasons for their academic writing challenges. For example, a few students shared that because they frame their ideas in their native language, it becomes challenging for them to express those ideas in English due to the differences in structures, vocabulary, mechanics, and semantics between the two languages. These were depicted in these quotes:

“I tend too much often to use French grammatical structures and to apply it in English. Some words are not in my database of my vocabulary and I don’t think of those words. So, for me it’s two problems: it’s grammatical structures; and vocabulary.” (7th year PhD student, French speaker)

“In my… mother tongue- the syntax, or the semantics, how to organize sentences is totally different from English. in my writing… people find it quite easy to see that this kind of paper is written by a foreign people and not by a native speaker.”(1st year PhD student, Farsi speaker)

“One of the challenges that we have, that at least I have, is the difference in structures and organization… between my language, which would be Italian and English. So sometimes I tend to write sentences in the Italian structure, which is not the correct one.” (2nd year PhD student, Italian speaker)

Some students also highlighted the challenges they face while writing with their faculty supervisors such as getting timely and adequate feedback from them and making sure if they understand that feedback correctly. They further shared how this lack or delay of clear communication between them and their supervisors about their writing challenges led to loss of time and stress during their doctoral programs. This is depicted in these quotes:

“How to differentiate between a comment about concepts from a comment about writing. Like, sometimes I’m like, so is the idea correct and it’s not written well? Or are you saying the idea itself is crap? Like, can you tell me, if you know, where should I make the change. That took me many months to figure out. And yes, I think that more feedback would mean that you can actually talk to them and say I don’t understand what this comment means, but if you get less number of feedbacks and then that itself is like very confusing then you’re just stuck with four comment which you’re like… okay I think I’m terrible, I think I should just leave, this makes no sense.” (2nd year PhD student, Italian speaker)

“I’ll need to work more- just read them again and again and again and sometimes I’ll realize, oh I could use precise language… words that I was not thinking about. So it’s just more time consuming and time is against us in the PhD program.” (3rd year PhD student, French speaker)

Commonly Used Resources

The most common English language development or academic writing support sought out by doctoral students was university workshops (n = 28 students, 25%). After university workshops, the university writing center (20%) was listed as other commonly used English language support. Less common sought out supports were tutoring (9%) and writing retreats (8%). Some students also used resources outside the university such as grammar-check tools. However, around 62% doctoral students (n = 71) indicated that they had not sought out any support for their academic writing development.

When asked about the reasons for not using university’s academic writing center over the subsequent focus group discussions, participants shared that either they were not aware of those services or felt that they needed support from someone belonging to their own discipline, as depicted in the quotes below:

“I started coming to the writing center only in my fourth year, which I was not aware of before… and I’m in fifth year now, and… it’s just… I’m here because of my editing, or the lack of editing (laughs) in my first draft because I didn’t know what to edit for. these things are something I could have started looking for in my first year.” (5th year PhD student, Hindi speaker)

“I think I was kind of aware of this possibility, but I think right now the major challenge I’m facing is improving on clarity in a way that can possibly only be done be somebody who’s in a research field. So, I think I notwithstanding that I could improve on structure and grammar and so on and so on, I think a major challenge I have is on particularly on specific points.” (2nd year PhD student, German speaker)

Participants further shared although they appreciate the support provided by English language experts, lack of technical or subject knowledge by them creates a barrier to either use those services. Lack of discipline specific knowledge among English language experts made those services less relevant for doctoral students across highly specialized disciplines. This was depicted in this quote:

“When they try to suggest us re-writing the sentence in a way that I know is not correct. So, their suggestion is not right because the science is modified for a different clarity purpose.” (3rd year PhD student, Hindi speaker)

Academic Writing Supports Needed

Students were also asked what writing supports would help improve their academic writing skills. The most important written language support as indicated by 64 respondents (56%) was personal feedback on writing tasks. Doctoral thesis writing workshops and working one-on-one with language experts to check writing regularly were identified as the next most important writing supports each with 47 students (41%). Finally, students were asked what they believe is the best way for their supervisors to give them feedback about their writing. The majority of students (56%) identified that the best way for supervisors to provide written feedback to students was highlighting the errors and informing the student of the type of error.

In the subsequent FGDs, students highlighted several aspects of the support that they thought would help in academic writing. For example, participants shared that a formal training should be provided to all PhD students, right from the beginning of their PhD, though this support should be available to them throughout their PhD program.

“If in the first year itself that they had a course, or just someone or something- an online module on little things like punctuation or comma splices, and length of sentences. Um… it would have definitely helped me figure out what was going wrong with my writing earlier.” (5th year PhD student, Hindi speaker)

“If there was a two-week time that we just dedicated all the efforts and energies to correcting systematic errors that we do when writing in English, then it would be so much easier afterwards.” (3rd year PhD student, Hindi speaker)

When asked further about their preferred arrangements to receive such support, they suggested a hybrid model wherein university’s writing center provides support on English language in the form of online modules, classes or one-on-one appointments with English language experts, while their department and its faculty members provide them training in discipline specific writing via seminars or workshops. These are depicted in the several of the quotes highlighted below:

“I think the support should be more department-specific rather than the entire university. I would say it’s more beneficial because academic writing’s different for every department…. (agreement in group)” (3rd year PhD student, Farsi speaker)

“May be the professors who have 10 to 15 years’ experience writing research reports can have a one-hour seminar throughout the semester, every 2 or 3 weeks, so they can share what they basically do when they’re reviewing reports, as well as also when developing their writing styles.” (1st year PhD student, Arabic speaker)

“um… that is something for sure we could do like every year like a couple seminars on uh, semantics and punctuation- whatever topic in writing. But uh… sometimes it’s also about the structure of the… of the paper or the thesis. Um… writing my proposal of research um… research proposal? (laughs) I was uh, it was really helpful for me- both because it’s a great writing exercise and also because I learned the importance of having um, a frame when I start writing.” (3rd year PhD student, Spanish speaker)

“I think that not only if even the first year when it’s recommended for them or as we see now it’s most beneficial to them, if it’s open for later for second or third year they will still go if they think it’s useful…” (4th year PhD student, Mandarin speaker)

With respect to supervisors, students shared that they would like their supervisors to communicate expectations and give examples of good writing from the beginning of their program. They also suggested that there should be a link between supervisors and university’s writing center, so that they can be referred whenever they need support in English language, as depicted in this quote:

“I’m not aware that supervisors or profs at [university name] have been in contact with SASS at all, so I think it would be helpful to improve on this link because if supervisors find that students need sort of help that could be provided in the framework of these services, then they could say, well why don’t you ask, you know, the people here and then they will help you with the structure, the grammar and so on, and they don’t have to spend time on things that we could get help on otherwise.” (3rd year PhD student, French speaker)

Faculty Supervisors

Academic Writing Challenges

The most common areas of difficulty highlighted by faculty supervisors were grammar (n = 27, 87%), followed by logical organization (n = 20, 65%), mechanics (n = 19, 61%), vocabulary (n = 19, 61%), content/ideas generation (n = 14, 45%), writing process (n = 14, 45%) and semantics (n = 11, 35%).

In the FGDs, faculty members expanded further on the academic writing challenges that their EAL students face or have faced in the past. Using correct grammar and synthesizing and expressing ideas in a cohesive way were the two main challenges highlighted by faculty members. They also acknowledged that academic writing in general is a skill that even native English speakers find difficult. These are reflected in the quotes below:

“It’s as much as being grammatically correct as being able to express ideas in a concise and accurate succinct manner…” (Assistant Professor, Arabic speaker)

“I think I see this part of the training as not only you want them to be grammatically correct, but you want them to be able to say things to an audience – that they can say the right thing to the right audience and be persuasive in certain manner that they would be effective public speakers. But this will take time and some process we go through.” (Associate Professor, Mandarin speaker)

“Academic writing issues affect domestic students also, but especially if you have done an undergraduate degree outside Canada, then you’re going to be limping…” (Assistant Professor, French speaker)

“Sometimes I find that our domestic students have trouble writing and these are the people who went through the Canadian system in high school and undergraduate, so it’s not… I think writ- professional writing in general is… an issue and it would take some time generally for all of us…” (Professor, English speaker)

When explored further, faculty members shared the challenges they face while supervising EAL students in academic writing. For example, the quote below from a faculty member highlights how they need more time and effort to clearly understand and supervise the work of EAL students in comparison to students who are native English speakers.

“Before I can look at the idea, I have to go over and over and over the actual presentation so that I can understand the idea and argument clearly, and those additional rounds of assistance are not required for people who, who would perhaps have English as their first language. (Professor, English speaker)

Basically, we ask the student to write something and then rewrite it and rewrite it again depending on the student and how – how quickly, how quickly they’re getting it. The iteration can be anywhere between three and five times…” (Assistant Professor, French speaker)

Expanding on this further, another faculty member who was also a department head at the university shared that the extra amount of time and effort required to supervise EAL students lead to reluctance from faculty supervisors in supervising international students.

“I have had faculty members say they don’t wish to supervise international students because they have to spend so much more time editing their work. And it’s nothing to do with their brightness – they’re very competent, but to get to the same level of output requires a lot more effort on the part of the supervisor and so some prefer not to work with international students.” (Professor and Department Head, Chinese speaker)

Academic Writing Supports Provided and Awareness of Academic Writing Support on Campus

In terms of writing supports provided, 75% of faculty supervisors said they provided models of good writing such as academic papers, previous successful and/or unsuccessful theses, dissertations and journal publications. The next question asked if the supervisor has any specific processes they use when supervising EAL doctoral students. The answers were fairly evenly split between yes (45%) and no (55%). Some examples provided by respondents of specific processes included: providing writing exercises, earlier submissions compared to native English speakers, peer reviews and one-on-one writing support.

The next question asked about what writing support services the participants were aware of on campus that support student writing. This was an open-ended question that resulted in various answers; however, the most common answer was ‘The Writing Centre’ with 50% respondents indicating this as the only writing support service they were aware of on campus. However, some comments indicated that respondents felt the writing center was not intensive enough or merely supplemental for doctoral students.

“I’ve never sent any students there. I have assumed that because undergraduates at the end of the semester are waiting a month to get access to it, it’s simply not available for the kind of intensive work, the kind of on-going intensive work that is required for graduate-level students.” (Assistant Professor, Cantonese speaker)

Around 10% of faculty supervisors did not know of any writing supports. Other responses included: graduate school seminars, the University International Centre, the Centre for Teaching and Learning, and graduate school workshops. Finally, 2 respondents knew that support services exist, but did not know the name. Participants were also asked if they had referred students to these services, and 24 respondents (75%) said yes, and 7 respondents (25%) said no.

Academic Writing Supports Required

Participants were then asked in what ways they thought academic writing for EAL students could be strengthened at the university. The most frequent response (n = 18, 58%) was one-on-one group guidance from someone in a similar area of study. The second most frequent response was editing services/proofreading/grammar check tools (n = 17, 55%). The third most frequent response chosen by respondents was sitting one by one with a language expert to check writing regularly (n = 16, 52%). Also, courses on academic writing (n = 12, 39%), training on grammar, structure, and expressions in sentences (n = 11, 35%), and PhD thesis-writing workshops (n = 11, 35%) were in the top-most frequent responses.

In the subsequent FGD, we asked faculty members for suggestions for supporting EAL doctoral students. A common theme in the responses was that more resources should be allocated to EAL doctoral students with respect to writing supports; particularly one-on-one writing supports and editing services. Another suggestion that emerged in the discussions is that expectations, needs and challenges will be subjective based on the department and the student’s individual needs. Specifically, the faculty supervisors suggested for a course specifically designed for graduate students, offered by respective discipline-specific departments but designed and delivered in partnership with academic writing centre of the university.

“I think dedicated graduate supervision on graduate writing would be very valuable. But the problem I would have with that is the kind of supervision you could provide in the science is going to be very different than what you provide in the social sciences, and you provide in humanities. So, there would have to be people who really can write in the different modes.” (Assistant Professor, Italian speaker)

“I think you could have dedicated courses. This is possible, but the courses would have to be designed in conjunction with the departments that are involved.” (Assistant Professor, Cantonese speaker)

“I would say that ongoing support and continuous support through a feedback loop, which will return some gains, because if a course is just provided in the first year, by the time the student actually gets into the intensive writing phase – third year, fourth year, it might not turn out to be very effective…” (Assistant Professor, English speaker)

Finally, the discussions indicated that faculty supervisors would like to have resources external to themselves in terms of academic writing support, so that they have more time to focus on technical content of the student’s writing.

Discussion

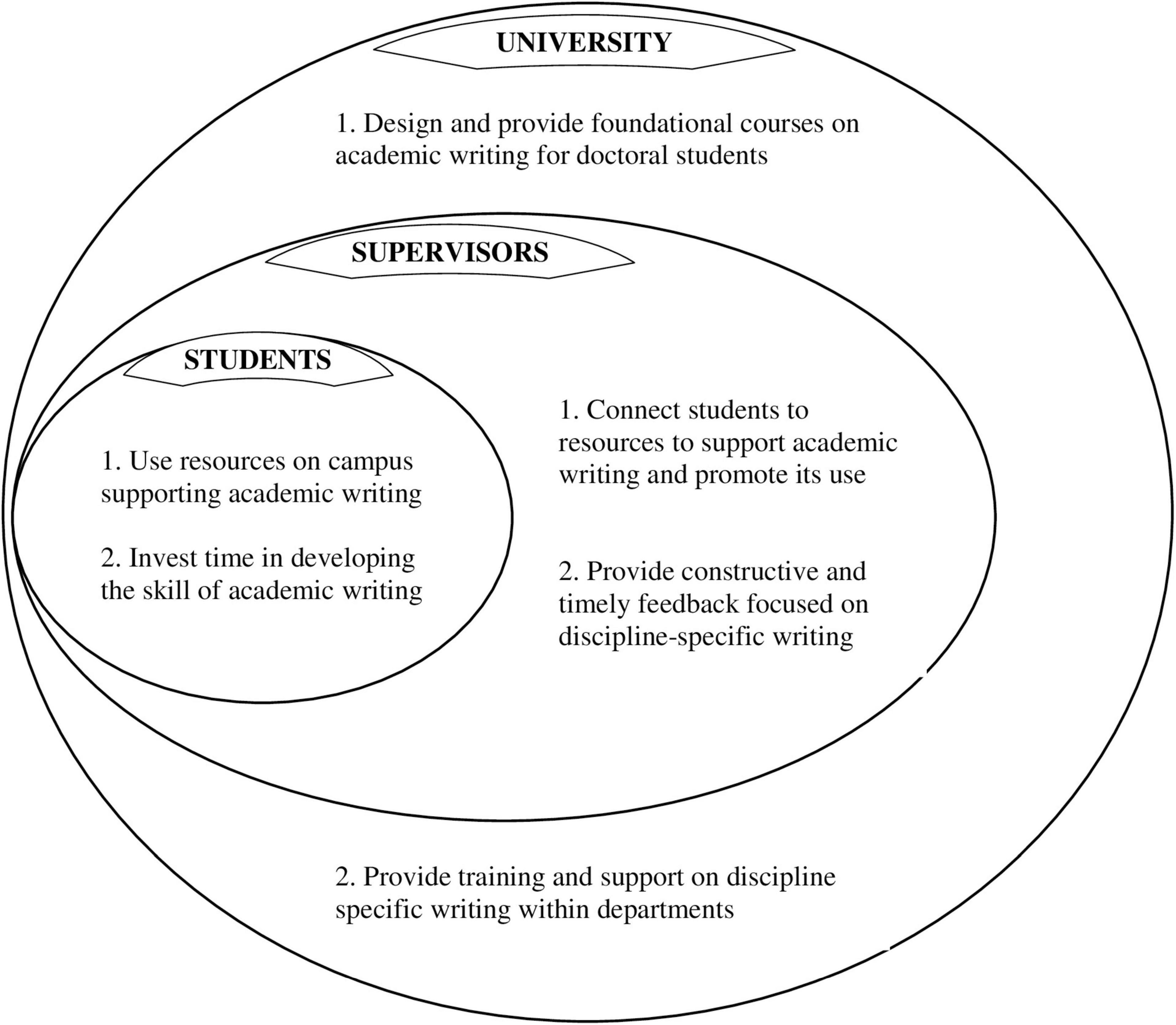

The purpose of this study was to explore academic writing challenges faced by EAL PhD graduate students and their faculty supervisors. The students chose writing process and content/ideas as their highest rated areas of difficulty whereas for faculty members, grammar and logical organization were the two most common areas where EAL students need improvement. Our study was confined to one post-secondary institution in Canada, though the findings can be applied widely to other universities in Canada and around the world where international student population is growing. We discuss three key recommendations that emerged out of this study (Figure 2) while comparing our findings with other similar studies.

Need of Specialized Writing Support Services for Doctoral Students

Writing at the doctoral level requires a highly specialized understanding of the subject area that cannot be expected to be provided by the support staff at university writing centers. This was echoed by faculty supervisors and students in our study that felt the existing writing support center needs more capacity to support the intensity of a doctoral program. This finding has important implications for the universities where there are currently no writing centers dedicated to doctoral students and that for EAL doctoral students only. A previous study examined a doctoral support group for EAL students. In this program, native English speakers volunteered to review doctorate’s academic writing at the draft stages for clarity, grammar, and spelling/punctation (Carter, 2009). Although the service was specific for doctoral EAL students, the volunteers did not receive EAL training or had to be doctorate holders (Carter, 2009). Therefore, some EAL students of the program had suggested for volunteers to be academically trained or department specific to receive more thorough assistance (Carter, 2009). On the other hand, a study in the United States examined a university that has a Doctoral Support Center (DSC) which provides technical and emotional support to doctoral students only (West et al., 2011). Technical services at the DSC included one-on-one consultations with writing class papers/dissertations, preparation support for proposal and dissertation defenses, and writing retreats/workshops (West et al., 2011). The services were offered by three writing advisors who are doctorate holders (West et al., 2011). These findings suggest that a doctoral focused writing service can be more beneficial compared to general writing centers and can provide more tailored support. More specifically, since EAL doctoral students require both English language and general dissertation support throughout their program, one-on-one support in this area can assist with student success, address common writing errors, and reduce workload of faculty having to provide continuous feedback.

Significance of Faculty Supervisors/Advisors Support for EAL Doctoral Students

Some faculty supervisors within our study reported allowing EAL students to submit their work early, provided examples of strong academic papers or previous dissertations, and/or provided individual writing support. Previous literature has identified one-on-one consultations with advisors helped EAL doctoral students receive personal feedback, improve their writing, and build confidence in themselves, (Odena and Burgess, 2017; Ma, 2019). On the other hand, our study and other studies reported some students did not receive timely, clear, or direct/specific constructive feedback from faculty, adding as a challenge to improve their writing (Sidman-taveau and Karathanos-aguilar, 2015; Abdulkhaleq, 2021). Faculty supervisors should be aware of the initial learning curve EAL students may face and ensure they have ample time and capacity to provide English language support to doctoral EAL students, in addition to general academic writing mentorship. Although in our study, faculty indicated some staff prefer not to supervise international students due to the extra time required, it is important to recognize the diversity, value, and enriching experiences that EAL students bring to teams. Based on our study findings and that of previous literature, it is evident faculty supervisors play an integral role in supporting doctoral students to become strong writers.

Furthermore, in our study, EAL students reported facing stress due to untimely feedback from supervisors. Other studies found that EAL students often feel discouraged, lack confidence, feel vulnerable, and greater pressure due to their English speaking/writing abilities (Maringe and Jenkins, 2015). One study had a participant suggest that academic writing courses should be taught by EAL staff since they will understand the technical and emotional challenges that EAL doctoral students face (Odena and Burgess, 2017). Based on these findings, it is recommended writing support centers and supervisors help build confidence in student’s writing skills by providing positive encouragement and acknowledging student’s improvement, while also understanding the additional pressure international EAL students face.

EAL Doctoral Students Use University Resources and Invest Time in Building Their Academic Writing Skills

One of the intriguing findings of this study was that while 89.5% of students felt that they do need to improve on their academic writing skills, 62% indicated that they had not sought out any support for their academic writing development. Further in the study, participant students have explained the challenges that prevent them seeking support for academic writing. However, it is important to highlight the importance of intrinsic motivation for academic and social integration of international students and role it plays to determine their success. Previous studies have found that international students’ motivation and learning attitudes are significant for their academic success and cultural adaptation in a new learning environment (Hsu, 2011; Zhou and Zhang, 2014; Eze and Inegbedion, 2015).

There are many things that EAL doctoral students can do to improve their academic writing skills, as demonstrated to be effective by research evidence. Recently, a number of published studies suggest that participation in writing retreats help graduate students in developing academic writing abilities through a community of practice formed during writing retreats and interacting with their peers afterward (Kornhaber et al., 2016; Tremblay-Wragg et al., 2021). A few studies also suggest students examine their beliefs about writing and form a writer identity to improve their style and come up with effective strategies that work for them. Authors suggest that these activities can be useful across any discipline, in which high-stakes writing is used (Boscolo et al., 2007; Fernsten and Reda, 2011). Some of the other effective strategies that could be helpful include developing a network for peer feedback, writing regularly, personal organization while keeping time aside for academic writing, and building self-motivation and resilience (Wellington, 2010; Odena and Burgess, 2017).

Limitations

Our findings were only limited to a Canadian university; hence, the findings may not be generalizable to other contexts. The participation in the study was voluntary, hence the survey respondents were not representative of all EAL doctoral students on campus. Although the sample for qualitative data (n = 31) is reasonable, it was not representative of all disciplines. The findings should be interpreted with caution with respect to discipline-specific nuances toward academic writing challenges and supports. Gathering data on students’ level of language proficiency, previous educational setting or background and personal characteristics could have provided a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomena. Moreover, this study was limited to academic writing challenges and supports for international graduate students; it will be interesting to explore this phenomenon among domestic doctoral students and their supervisors to ascertain the impact of writing culture and level of language proficiency on scientific writing. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings still provide original and meaningful insight into academic writing challenges and required supports for EAL doctoral students and have the potential to inform programs on academic writing in higher education.

Conclusion

This study explored academic writing experiences—challenges and potential solutions from the perspective of EAL PhD graduate students and their faculty supervisors at a Canadian University. With the rise in international student population across Canada, understanding the doctoral academic writing challenges is critical to strengthen the existing services and development of an academic writing model that support students and their supervisors toward successful academic writing experience and outcomes. Our study indicated that EAL doctoral students require both English language and general dissertation support throughout their program. A doctoral-focused writing service will be beneficial compared to general writing centers given they can provide more tailored support. One-on-one support in this area can assist with student success, address common writing errors, and reduce workload for faculty members. There is a need for multipronged approach at various levels to provide a conducive and enabling environment and support resources for the students to thrive in their doctoral journey, and timely complete their thesis with success.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by General Research Ethics Board of the Queen’s university. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SG and AJ contributed to the conception and design of the study. JK contributed to the design of data collection tools. SG, AJ, and AP were involved in writing the first draft of the manuscript. JK and SG edited the final manuscript for submission. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Klodiana Kolomitro, Susan Korba, Marta Straznicky, Agniezka Herra, and Colette Steer for their support to this research project. We would also like to thank the students at Queen’s University who participated in this study and shared their experiences. We would like to acknowledge the support of Centre for Teaching and Learning at Queen’s University for providing educational research grant to conduct this research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.891534/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdulkareem, M. N. (2013). an investigation study of academic writing problems faced by Arab postgraduate students at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM). Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 3, 1552–1557. doi: 10.4304/tpls.3.9.1552-1557

Abdulkhaleq, M. M. A. (2021). Postgraduate ESL student’s perceptions of supervisor’s written and oral feedback. J. Lang. Commun. 8, 45–60.

Aitchison, C., Catterall, J., Ross, P., and Burgin, S. (2012). “Tough love and tears”: learning doctoral writing in the sciences. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 31, 435–447. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2011.559195

Boscolo, P., Arfé, B., and Quarisa, M. (2007). Improving the quality of students’ academic writing: an intervention study. Stud. High. Educ. 32, 419–438. doi: 10.1080/03075070701476092

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101.

Caffarella, R. S., and Barnett, B. G. (2000). Teaching doctoral students to become scholarly writers: the importance of giving and receiving critiques. Stud. High. Educ. 25, 39–52. doi: 10.1080/030750700116000

Campbell, T. A. (2015). A phenomenological study on international doctoral students’ acculturation experiences at a U.S. university. J. Int. Stud. 5, 285–299.

Carter, S. (2009). Volunteer support of english as an additional language (EAL) for doctoral students. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 4, 013–025. doi: 10.28945/43

Doyle, S., Manathunga, C., Prinsen, G., Tallon, R., and Cornforth, S. (2018). African international doctoral students in New Zealand: englishes, doctoral writing and intercultural supervision. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2017.1339182

Eze, S. C., and Inegbedion, H. (2015). Key factors influencing academic performance of international students’ in UK universities: a preliminary investigation. Br. J. Educ. 3, 55–68. doi: 10.37745/bje.vol3.no5.p55-68.2013

Fernsten, L. A., and Reda, M. (2011). Helping students meet the challenges of academic writing. Teach. High. Educ. 16, 171–182. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2010.507306

Gopee, N., and Deane, M. (2013). Strategies for successful academic writing – institutional and non-institutional support for students. Nurse Educ. Today 33, 1624–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.02.004

Guest, G., MacQueen, K., and Namey, E. (2014). Introduction to applied thematic analysis. Appl. Themat. Anal. 3:20. doi: 10.4135/9781483384436.n1

Gupta, S. (2017). Ethical issues in designing internet-based research: recommendations for good practice. J. Res. Pract. 13, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1612-3

Hsu, C.-H. (2011). Factors Influencing International Students’ Academic and Sociocultural Transition in an Increasingly Globalized Society. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 153. Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/868529304?accountid=10673%0Ahttp://openurl.ac.uk/redirect/athens:edu/?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&genre=dissertations+%26+theses&sid=ProQ:ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+Global&at (accessed April 30, 2022).

Inouye, K., and McAlpine, L. (2019). Developing academic identity: a review of the literature on doctoral writing and feedback. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 14, 001–031. doi: 10.28945/4168

Ipek, H. (2009). Comparing and contrasting first and second language acquisition: implications for language teachers. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2, 155–163.

Ismail, H. M., Majid, F. A., and Ismail, I. S. (2013). “It’s complicated” relationship: research students’ perspective on doctoral supervision. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 90, 165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.078

Itua, I., Coffey, M., Merryweather, D., Norton, L., and Foxcroft, A. (2014). Exploring barriers and solutions to academic writing: perspectives from students, higher education and further education tutors. J. Furth. High. Educ. 38, 305–326. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2012.726966

Jones, M. (2013). Issues in doctoral studies -forty years of journal discussion: where have we been and where are we going? Int. J. Dr. Stud. 8, 83–104.

Kornhaber, R., Cross, M., Betihavas, V., and Bridgman, H. (2016). The benefits and challenges of academic writing retreats: an integrative review. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 35, 1210–1227. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1144572

Lee, A., and Boud, D. (2003). Writing groups, change and academic identity: research development as local practice. Stud. High. Educ. 28, 187–200. doi: 10.1080/0307507032000058109

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1985). Lincoln and Guba’s Evaluative Criteria. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 3684.

Lonka, K., Ketonen, E., Vekkaila, J., Cerrato Lara, M., and Pyhältö, K. (2019). Doctoral students’ writing profiles and their relations to well-being and perceptions of the academic environment. High. Educ. 77, 587–602. doi: 10.1007/s10734-018-0290-x

Ma, L. P. F. (2019). Academic writing support through individual consultations: EAL doctoral student experiences and evaluation. J. Sec. Lang. Writ. 43, 72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2017.11.006

Maher, M. A., Feldon, D. F., Timmerman, B. E., and Chao, J. (2014). Faculty perceptions of common challenges encountered by novice doctoral writers. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 33, 699–711. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2013.863850

Maringe, F., and Jenkins, J. (2015). Stigma, tensions, and apprehension: the academic writing experience of international students. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 29, 609–626. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0049

McAlpine, L., and Amundsen, C. (2011). Doctoral Education: Research-Based Strategies for Doctoral Students, Supervisors and Administrators. Quebec: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0507-4

Odena, O., and Burgess, H. (2017). How doctoral students and graduates describe facilitating experiences and strategies for their thesis writing learning process: a qualitative approach. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 572–590. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1063598

Pidgeon, M., and Andres, L. (2005). Demands, Challenges, and Rewards: The First Year Experiences of International and Domestic Students at Four Canadian Universities. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia.

Sala-Bubaré, A., and Castelló, M. (2018). Writing regulation processes in higher education: a review of two decades of empirical research. Read. Writ. 31, 757–777. doi: 10.1007/s11145-017-9808-3

Sidman-taveau, R., and Karathanos-aguilar, K. (2015). Academic writing for graduate-level english as a second language students: experiences in education. CATESOL J. 27, 27–53.

Statistics Canada (2020). International Students Accounted for all of the Growth in Postsecondary Enrolments in 2018 / 2019. The Daily. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/201125/dq201125e-eng.htm (accessed April 30, 2022).

Tremblay-Wragg, E., Mathieu Chartier, S., Labonté-Lemoyne, E., Déri, C., and Gadbois, M. E. (2021). Writing more, better, together: how writing retreats support graduate students through their journey. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45, 95–106. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1736272

Wellington, J. (2010). More than a matter of cognition: an exploration of affective writing problems of post-graduate students and their possible solutions. Teach. High. Educ. 15, 135–150. doi: 10.1080/13562511003619961

West, I. J. Y., Gokalp, G., Peña, E. V., Fischer, L., and Gupton, J. (2011). Exploring effective support practices for doctoral students’ degree completion. Coll. Stud. J. 45:310.

Keywords: international students (foreign students), academic writing and publishing, supervisors and supervision, university resources, support and services

Citation: Gupta S, Jaiswal A, Paramasivam A and Kotecha J (2022) Academic Writing Challenges and Supports: Perspectives of International Doctoral Students and Their Supervisors. Front. Educ. 7:891534. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.891534

Received: 07 March 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Barry Lee Reynolds, University of Macau, Macao SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Juan Carlos Silas-Casillas, Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education, MexicoGiedre Tamoliune, Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania

Diane Hunker, Chatham University, United States

Africa Hands, East Carolina University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Gupta, Jaiswal, Paramasivam and Kotecha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shikha Gupta, c2hpa2hhLmd1cHRhQHF1ZWVuc3UuY2E=

Shikha Gupta

Shikha Gupta Atul Jaiswal

Atul Jaiswal Abinethaa Paramasivam2

Abinethaa Paramasivam2 Jyoti Kotecha

Jyoti Kotecha