- 1Department of Computer and Robotics Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

- 2Department of Home Economics and Hospitality Management Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

- 3Department of Business Management, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

- 4Department of Computer Science, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria

- 5Department of Computer Education, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Nigeria

- 6Department of Business Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

- 7Department of Education Planning and Administration, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

This study investigated the underlying factors that influences pre-service Nigerian (technical vocational education and training, TVET) teachers’ decision to pursue a teaching career which aids in recruiting more teachers. Preservice TVET teachers are the teachers who are being prepared to teach in a vocation requiring technical skills. The motivation of these pre-service TVET teachers obtaining a postgraduate diploma in technical education was investigated using the quantitative research design approach to collect data via a researcher-created, self-administered questionnaire. Participants were selected from two cohorts (N = 78) of students enrolled in the various departments for the Postgraduate Diploma in Technical Education (PGDTE) program of the University of Nigeria. According to the quantitative analysis, excellent role models from previous teachers, the demanding nature of the job role, a willingness to impart relevant knowledge and skills, a willingness to assist financially disadvantaged students in gaining marketable job skills, and the country’s presumed demand for TVET teachers were the primary motivators for pre-service teachers. However, the gender aspect revealed that male and female pre-service TVET teachers showed significant differences in their altruistic and intrinsic impulses when the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were utilized to analyze extracted data on gender. The ramifications of the findings were then examined, as well as their significance in enhancing hiring measures through setting of standards for technical and vocational education programs in the universities to improve on the status of pre-service TVET teachers to attract quality graduates of technical education programs who can teach as TVET teachers before and after completing their programs.

Introduction

Recent improvements in the Nigerian educational system have highlighted the need of (technical vocational education and training, TVET) teacher preparation. TVET is a subject of interdisciplinary education research (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2018). Understanding the concept of TVET will necessitate dissecting each words from the acronym. For example, technical will mean all technical subjects like hardware and software, as well as troubleshooting techniques and engineering processes that serve as a link between inventors and their clients (Roger and Berwyn, 2020); vocational relates to an occupation or employment, and is frequently used in initiatives for reskilling or upskilling companies (Joyce, 2019; Agrawal et al., 2020); education relates to the process of facilitating learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, morals, beliefs, habits, and personal development (Ari et al., 2022); and training relates to informal education, also known as life-long learning or continuing education (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training [Cedefop], 2020). In its essence, TVET is defined by UNESCO as all forms and levels of education and training that give the necessary information and skills for occupations in many sectors of the economy and society through formal, non-formal, and informal learning methods in both school-based and work-based learning contexts. To summarize, TVET encompasses all structured educational programs, services, and activities connected to the training of persons for paid or unpaid labor, as well as extra preparation for a vocation requiring technical skills or a post-secondary or higher education advanced degree (source). TVET is more transition-oriented, with the goal of equipping students and adults with career and life skills. In other words, TVET is an important government tool for lowering unemployment and delivering workforce to both the public and private sectors.

Technical and vocational education and training can be given in a variety of ways, from publicly funded institutions (such as high schools, colleges, polytechnics, and universities) to semi-private or private institutions that serve as corporate training centers or universities (Parker et al., 2018; Dawkins et al., 2019; Maddocks et al., 2019). Institutions involved in the delivery of TVET are referred to as TVET providers. The Nigerian Universities Commission (NUC) approved University of Nigeria as TVET provider in 2016, adding six Technical-Vocational departments for students who intend to pursue a teaching profession in the technical and vocational areas after leaving school. The relevant topics here are Agricultural, Business, Computer and Robotics, Home Economics and hospitality management, Industrial Technical, and Entrepreneurial Education. This approval has a big impact on the quality and quantity of TVET teacher preparation.

Regarding the quality of TVET teacher preparations, various trainings offered to in-service TVET teachers address the quality component of this part. A significant number of trainings had already taken place, with the goal of equipping trainers and teachers to better assist students enrolled in Technical and Vocational courses as part of a new school curriculum. The question of quantity, on the other hand, has yet to be successfully addressed. This is because more TVET trainers and teachers will be needed to teach technical - vocational courses to students. However, if a reform is adopted in actuality, there would still be a need for roughly 20,000 TVET teachers for government technical colleges in Nigeria. With a projected 10,000–15,000 vacancies for TVET teachers, TVET teachers will make the highest vacancies (Arcangel, 2014).

In Nigeria, there are several options for becoming a TVET teacher. The Ladderized Education Program (LEP) system is one of them (Lauro et al., 2019). The National Board for Technical Education (NBTC) saw (LEP) as a solution to the current obligation of technology institutions to provide Nigerian students with a variety of options for becoming skilled and employable. Postgraduate Diploma students in this program thus began with TVET courses that, if desired, can be transferred to a college Master degree. A laddered Post Graduate Diploma in Technical Education (PGDTE) curriculum was then designed in the six departments of Vocational and Technical Education of the University of Nigeria for TVET graduates interested in pursuing a career in teaching. Its goal is to prepare TVET teachers who have a strong academic understanding of education and technology as well as practical industry experience (National Board for Technical Education [NBTE], 2014). In Nigeria, there are approximately 44 institutions that offer the PGDTE curriculum (Calimlim, 2011).

Today, these institutions that offer this program face a shortage of teachers in technical and vocational related programs, particularly in the fields of industrial technical education, arts and business, agriculture, and fisheries, and all these colleges must take step in the right direction to address these concerns (Valles, 2012). Therefore, there is a need for more aggressive promotion of TVET teacher training programs, which necessitates a knowledge of the motivations for becoming a TVET teacher.

Various researches has been conducted in this sector (Ibrahim, 2014; Kavanoz and Yüksel, 2017; John, 2020; Usman et al., 2021), but only a handful have concentrated entirely on pre-service TVET teachers’ motivation to teach. The goal of this study was to start a discussion about the problem and stimulate more research and involvement among TVET teacher training colleges, particularly in Nigeria, on what motivates potential TVET teachers to pursue the profession.

Literature review and theoretical framework

Occupational choice motivation

Motivation is described as the underlying causes for behavior in a wide sense (Ricarda et al., 2019; Hana et al., 2021; Matthew et al., 2022). The majority of individuals are driven to work in order to meet their fundamental necessities of food and housing (Broton and Goldrick-Rab, 2018). People, on the other hand, have different ideas about what they want to do with their lives. Several research on motivations to work have indicated that these decisions are influenced by a variety of factors, some of which are relatively diverse (Iraz, 2016).

This is also true in the field of education. As indicated by the different researches and models attempting to describe teaching job-related motivations, motivation to teach has been seen as a multidimensional construct. These studies have sought to elucidate why teachers choose to teach as a profession. In order to identify the determinants influencing the decision to become a teacher, the bulk of them were based on theories such as expectancy-value theory (Eccles, 1983), self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985), and its sub-theory such as cognitive evaluation theory and motivational theory of altruism.

The Expectancy-Value Theory was created to help readers understand what drives them to accomplish their goals. It proposes that achievement-related decisions are influenced by a mix of people’s expectations of success and subjective task value in subject areas. However, the theory believes that two components, success expectancies and subjective task values, are most strongly linked to achievement and achievement-related decisions when it comes to pre-service teachers’ motivation (Eccles, 1983). When applied to the task of selecting occupations, this approach predicts that when multiple behaviors are available, the one chosen will have the highest combination of expected success and value, implying that people will pursue options for which they believe they have the necessary abilities, for which they attach value, and for which they will not incur a significant cost.

However, according to the self-determination theory also, pre-service teachers’ motivations is motivated to maintain an ideal level of stimulation (Deci and Ryan, 1985), and people have fundamental demands for competence and personal causality. The cognitive evaluation theory on the other hand lays forth elements that explain intrinsic motivation and its complexities, as well as how extrinsic factors like the environment and social factors influence intrinsic motivations (Deci and Ryan, 1985). The theory’s most basic contrast is between intrinsic motivation, which refers to doing something because it is inherently desirable or enjoyable, and extrinsic motivation, which refers to doing anything because it leads to a specified goal (Fischer et al., 2019; Eze et al., 2021). In a variety of professional circumstances, these two distinct motivations have been commonly employed to characterize motivations in several occupational scenarios. However, because of differences in educational and business systems, motivation to teach may differ from motivation in business jobs (Annette et al., 2018). Here, intrinsic and extrinsic incentive systems may be insufficient to address the core motivations for becoming a teacher. Various studies have focused on the “altruistic motives” of pre-service teachers (Carrera et al., 2018; Wangbei et al., 2022). Altruism is described as a mere readiness to behave in consideration of the interests of others without regard for personal gain (Wang et al., 2019). In other words, Altruism is defined as acting in consideration of others’ interests, without regard for ulterior motives (Hajek and König, 2022).

Nevertheless, socialization influences, task demand, task return, self-perceptions, intrinsic value, personal utility value, and social utility value were all identified as motives for choosing teaching as a career by Manuela (2015), who developed the factors influencing teaching choice framework based on expectancy-value theory and tapping altruistic and intrinsic motivations. Meanwhile, Han and Yin (2016) and Kolleck (2019), have all used the paradigm to better understand why teachers choose to teach. In another development, the highest ranked motives for selecting teaching in a large-scale Australian study employing the above-mentioned framework were perceived teaching talents, the intrinsic worth of teaching and the desire to make a good social contribution, shape the future, and engage with children/adolescent) (Howes and Goodman-Delahunty, 2015; Amanda et al., 2019; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2019; Viac and Fraser, 2020).

Using the same approach, a research of pre-service teachers’ career motivations in Turkey found that participants valued intrinsic motives the most, despite the fact that altruistic motivations accounted for several of the top causes (Ekin et al., 2021). Similarly, intrinsic and altruistic reasons were revealed to be the most influential motives to teach in a study of in-service teachers’ motives and commitment to the teaching profession in Estonia (Saks et al., 2019). Teaching staff members were also motivated by a sense of belonging and personal development (Allen et al., 2022). A qualitative study on pre-service teachers’ motivation in relation to occupational choice was undertaken in the Ghana (Usman et al., 2021) and majority of the individuals were intrinsically driven, according to the findings. Surprisingly, the study’s findings also indicate that the respondents still consider teaching to be the finest profession. Pre-service teachers’ perceptions about the profession appear to have an impact on their career decision. It is therefore consequently vital to strengthen the image and standing of teaching in order to make it a desirable professional choice.

The current research

As previously reviewed, scholars have recognized the growing importance of motivation for pre-service teacher education, as well as the creation of theoretical frameworks related to teacher motivation. This is because, “the domain of teacher motivation is ideally positioned to become a deeper subject of investigation because of its crossover appeals,” Hiver et al. (2018:17). However, though there have been sufficient studies on the motivation of pre-service teachers in other specialty areas, there are still some research gaps to be filled. One significant shortcoming is that no comprehensive research has been conducted on the motivations of pre-service TVET teachers. Previous research on teacher motivation has focused on English language teachers and Chinese teachers’ drive to educate (Chang, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2021) which may limit the findings’ applicability to other fields of teacher education. In the meanwhile, given the growing number of pre-service TVET instructors and the paucity of TVET teachers in Nigeria, more research into pre-service TVET teachers’ desire to teach is needed. The types of teacher motivation and ratings for each form of motivation are notably ambiguous among pre-service TVET teacher groups. To overcome this gap, the current study looked into the factors that influenced the pre-service work choices of these potential TVET teachers. To be more specific, the current study expands on past research in the field of teaching on pre-service teachers’ vocational choice motivation. However, despite the fact that the sample size is insufficient to make generalizations about Nigeria’s larger population of pre-service TVET teachers, and given that the setting (VTE faculty of the University of Nigeria) is one of the country’s largest pre-service TVET teacher education providers, it still provides insight into the topic and serves as a foundation for future research.

Objective of the research

Specifically, this study sought to:

(1) Investigate the occupational decision motives behind Pre-service TVET Teaching profession as a life career.

(2) Examine the statistical differences in pre-service TVET teachers’ best preferred motives based on gender.

Materials and methods

Participants and setting

Both cohorts (N = 78) of postgraduate Diploma in Technical Education program graduates took part in the study. All are enrolled in the vocational and Technical Education Faculty, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The participants’ average age was 37.87 (SD = 4.325); 40 (51.2%) were male and 38 (51.3%) were female; 26 (33.3%) were single and 9 (11.5%) were already married; 16 (20.5%) earn less than $8,000, 17 (21.7%) earn between $8,000 and 20,000, and 14 (17.9%) earn more than 20,000; 16 (20.5%) earn less than $8,000, 17 (21.7%) earn between $8,000 and 20,000, and 13 (16.6%) earn more than 20,000.

The study’s first objective was to look into the motivations for pre-service TVET teachers enrolling in UNN’s Postgraduate Diploma in Technical and Vocational Education program to teach. The faculty originated as Vocational Teacher Education (VTE), a vocational teacher school formed in 1973 with the express purpose of advancing worker dignity. In the fall of 2016, the faculty was upgraded to Vocational and Technical Education and introduced six vocational-technical departments with 1, 2, 3, and 4-year vocational-technical Education curriculum leading to a Bachelor (B.Sc/B.Tech), Masters (M.Sc/M.Tech), and PGDTE in the respective departments in response to the need for skilled teachers in technical and vocational courses. The PGDTE became part of the ladderized education system when it was renamed Vocational Technical Education to afford graduates of technical vocational courses to pursue a teaching career.

Instrument

To acquire relevant data, the researchers created a pre-service teachers’ motivation to teach (PSTMTT) questionnaire. The questionnaire is divided into two halves. The respondents’ backgrounds are elicited in the first half (e.g., age, sex, civil status, and socio-economic status). The second half is exploratory in nature and comprises 12-item scale derived from the “teaching motivation scale” (TMS) of Vallerand et al. (1992) and motivated strategies subscale of Pintrich et al. (1993), to measure the participants’ motivations for choosing an occupation in TVET teaching as a life career. The participants were expected to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree to each of the individual elements depending on how much each assertion related to their motivation to become a teacher. A 5-point scale was used, ranging from “not all true of me” (1) to “completely true of me” (5) and respondents rated all the items.

Validation of instrument

The instrument was face validated for structure and relevance and content validated to ascertain if the items adequately reflect the process and content dimension of the objective of the instrument (Elisabet et al., 2020). This was carried out as a justification for pre-service TVET teacher’s selecting teaching as an occupation by one of the researchers’ university colleague and two doctoral students. Thereafter, a quantitative pilot study was administered to a representative sample which produced quantitative data that the researcher analyzed and used to test for internal consistency through Cronbach’s alpha. Four items were amended. However, according to the reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha), internal consistency was good, with a value of 0.82 indicating acceptable reliability (Michael, 2021).

Procedure

The questionnaire was designed based on a survey of pertinent literature and changed accordingly based on comments and recommendations from colleagues during the latter part (March) of Academic Year 2020–2021 (one colleague from the university and two doctoral students). The questionnaires were distributed with the participants’ consent and retrieved with the help of one research assistant before the start of Academic Year 2021. The survey questionnaire took about 15 mins to complete for the participants.

Data analysis

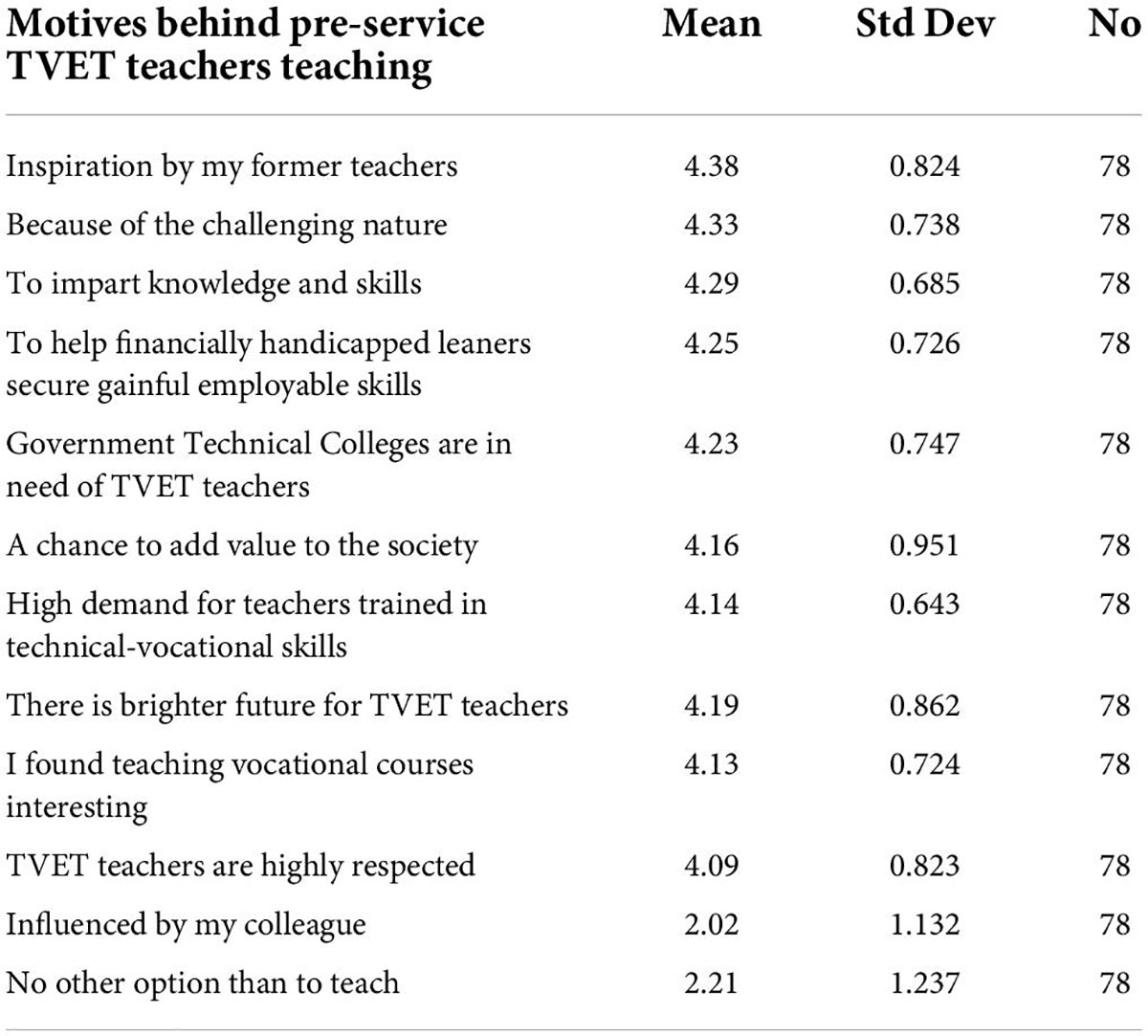

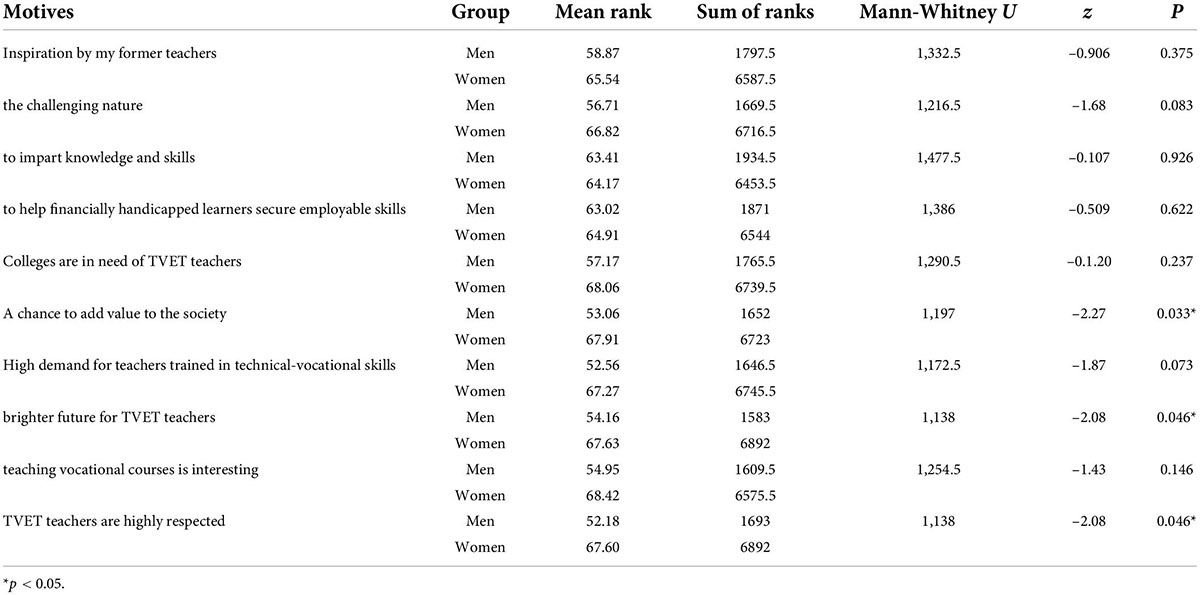

The data collected from the respondents were analyzed using the mean rating and standard deviation for the hierarchical multiple responses of pre-service TVET teachers on the 12 individual Likert-type items on motives for selecting teaching as a career. The average evaluations were then ranked. Moreover, inferential statistics of non-parametric Mann-Whitney U Tests were utilized to analyze extracted data for answering research question 2 (see Tables 1, 2).

Table 1. Result of occupational decision motives behind pre-service technical vocational education and training (TVET) teaching.

Table 2. Non-parametric results for pre-service technical vocational education and training (TVET) teachers’ best preferred motives for teaching based on gender.

Heading results

The results of data analysis are done with reference to the research questions formulated. The order of presentation is as organized below.

Preliminary report

To answer research question 1, Table 1 presents a quantitative analyses involving the reports of the data generated for the purpose of determining the motives behind pre-service TVET teachers teaching. Our analysis revealed that the most important motivator for pre-service TVET instructors was the inspiration provided by their former teachers (M = 4.38, SD = 0.824). The participants’ perceived imparting useful knowledge and skills (M = 4.29, SD = 0.685) is also one of the top motivations, as is their desire to assist economically disadvantaged students in gaining employable skills (M = 4.25, SD = 0.726), which is one of the goals of the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 that TVET was fully incorporated into the country’s education.

The data also indicate that the new education law may have an impact on pre-service TVET teachers’ motives. According to the findings, one of their primary motivations for pursuing a career in TVET teaching was the belief that the reform would necessitate a large number of TVET teachers (M = 4.23, SD = 0.747), as well as the belief that there is a high demand for Technical Vocational Education teachers in general (M = 4.14, SD = 0.643) and that TVET teachers have a bright future in the country (M = 4.19, SD = 0.862). Furthermore, there is a widespread willingness to give back to society (M = 4.16, SD = 0.951). It is really worth noting that the majority of participants considered TVET teaching to be fascinating (M = 4.13, SD = 0.724) and TVET teachers to be highly respected (M = 4.09, SD = 0.823). However, from the table, the lowest ranked motives were being affected by their colleagues (M = 2.02, SD = 1.132) and leaving no other options than to teach (M = 2.21, SD = 1.237).

To analyze whether motivating factors differ between genders of pre-service TVET teachers and their preferred motives for teaching at alpha level 0.05, Mann Whitney U Test was run. According to Table 2, the obtained significance level of all motives except for inspiration by my former teacher (0.375), to impart knowledge and skills (0.926), the challenging nature (0.083), to help financially handicapped learners (0.622), colleges are in need of TVET teachers (0.237), the high demand teachers trained in technical-vocational skills (0.073), and teaching vocational courses is interesting (0.146) are lower than p > 0.05 indicating that there is a statistically significant difference between male and female pre-service TVET teachers as against other factors of “a chance to add value to the society (0.033)”, “brighter future for TVET teachers (0.046)”, and “TVET teachers are highly respected (0.046)” which showed no significant difference. However, the mean ranks of the two groups revealed that female pre-service TVET teachers got higher mean scores than their male counterpart in all listed occupational decision motives behind Pre-service TVET teaching. This is a clear indication that female pre-service TVET teachers were more inclined toward the teaching career than males due to extrinsic-altruistic-intrinsic impulses; thus upholding research question 2 regarding gender.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to discover what drives future TVET teachers to seek careers in the field. It used a quantitative research design technique where quantitative data was collected using a researcher-created, self-administered questionnaire. However, to analyze whether motivating factors differ between genders of pre-service TVET teachers and their preferred motives for teaching at alpha level 0.05, Mann Whitney U Test was also run. According to the investigations, the common underlying factors were a mix of intrinsic, extrinsic, and altruistic impulses. This is in line with Alexander et al. (2020) that extrinsic, intrinsic and altruistic motivators are all relevant to the employment practices that erode teachers’ self-concepts. However, according to the quantitative study, pre-service TVET teachers choose to teach mostly because of the impact of their former professors, which most likely refers to their instructors from the postgraduate diploma courses they took before graduation. This is an example of extrinsic motivation, highlighting the value of mentorship (Wang and Bale, 2019) and also is in line with Masbirorotni et al. (2020) and Gul et al. (2020). Accordingly, the reports in their study to investigate which motive (altruistic, intrinsic, and extrinsic) is dominantly influenced by high school graduates, revealed that among the three motives (altruistic, intrinsic, and extrinsic), extrinsic motives played a dominant role in selecting teaching as a career while intrinsic factors drive them to stay in the long run of teaching whereas altruistic factors of motivation were found to have no effective role. In a contract view, in Western countries, altruistic motivations have been the most prevalent reasons for choosing teaching as a vocation (Yuce et al., 2013). The authors, however, do not fully support the concept that most pre-service teachers in undeveloped and developing cultures select teaching as a career primarily on extrinsic motivations.

However, while some see their former professors’ influence and the present great demand for high-esteem TVET teachers as motivations to enter the sector, it is primarily their genuine enthusiasm and resolve to make a difference in society that drives them to do so (Helen et al., 2012). For example, the report of this study revealed that the participants took into account the perceived demand for teachers and their high appreciation for the profession. This report is in line with that of Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2018) who revealed that job demands and resources more moderately predicted higher well-being and motivations of teachers to choose teaching job.

However, while previous studies ignored the role of the gender, the present study examined the differences between male and female pre-service TVET teachers with respect to their motivating factors. The non-parametric results revealed that based on mean rank, female pre-service TVET teachers were more motivated to teach than their male counterpart in relation to all motivational factors. This is in line with the findings of Muhonen’s (2004) that male students were more de-motivated than female students with respect to the “Teachers” Competence and Teaching Styles’ factor. Maliki (2013) and Sharif et al. (2014) also maintained that potential female teachers fulfill their duties with dedication, responsibility and zeal. However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of “a chance to add value to the society (0.033)”, “brighter future for TVET teachers (0.046)”, and “TVET teachers are highly respected (0.046)”.

Implications

Theoretical implications

The outcomes of this study show that pre-service TVET teachers of diverse vocational disciplines have specific motivating qualities (Han et al., 2016). Putting a strong focus on intrinsic, extrinsic and altruistic values, for example, emphasizes their distinct motivations. According to Richardson et al. (2014), this could be owing to the effect of their various academic specialties. Furthermore, differences in extrinsic value and social influence among pre-service TVET teachers imply that socio-cultural contexts and instructional contexts may influence their motivations. Pre-service TVET teachers’ motivation may be influenced by variables at multiple levels, including subject specialization at the mesosystem, teaching context at the exosystem, and social cultures at the macrosystem, according to the findings of this study and the ecological system theory (Steffensen and Kramsch, 2017; Mohammadabadi et al., 2019). That is, rather than “a result of a limited number of aspects,” pre-service TVET teachers’ motivation could be “a product of a constellation of various distal and proximal factors to the teachers’ groups” (Mohammadabadi et al., 2019, p. 765). However, this narrative is theoretical, and more evidence will be necessary in future investigations. In conclusion, the current study added to the body of evidence supporting the use of expectancy-value theory to investigate pre-service TVET teachers’ motivation to teach (Shih, 2016; Kissau et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020).

Practical implications

In terms of practical implications, the findings of this study may be useful in addressing Nigeria’s scarcity of TVET teachers by promoting TVET teacher training programs aggressively, which will demand an understanding of their reasons for becoming a TVET teacher. The solution, on the other hand, is in attracting preservice TVET teachers and keeping in-service TVET teachers, whose motivation should be considered while building tech-voc education programs and managing in-service teachers. However, when developing the tech-voc program, one noteworthy tendency in teacher education is to regard instructors as agents in knowledge-building practice and to give opportunities for teachers to participate in this practice by forming a community where they may exchange, discuss, improve, and transmit ideas (Yang, 2021). In this regard, educational policy makers can establish policies that will enhance hiring measures through setting of standards for tech-voc education programs capable of improving the status of TVET teachers to attract quality graduates of technical education programs who can teach as TVET teachers before and after completing their programs.

Recommendations

To keep pre-service TVET teachers, measures to boost motivation are recommended. In this context, motivation refers to external or internal factors that influence a person’s desire to educate (Yaghoubinejad et al., 2017). Policymakers in technology education organizations or institutions should address the influencing factors that may demotivate pre-service TVET teachers in various contexts and take the necessary steps to create an environment that will encourage them to stay in the classroom, such as improving TVET teaching welfare and stability. Due to the limited scope of the current study, the methods for retaining pre-service TVET teachers are not discussed in detail. Again, at the pre-enrollment stage, pre-service TVET teachers’ motivations should be discovered and studied, with the data gathered and collated to create a nationwide and eventually regional profile of probable TVET teachers’ motivations. While the relative dominance of intrinsic and altruistic motivation is viewed favorably, potential TVET teachers’ extrinsic motivation must also be investigated since it provides insight into their general attitude and impression of TVET teaching. To help alleviate the scarcity of TVET teachers in Nigeria, more attention should be paid to the design of tec-voc programs based on empirical studies on technology teacher education. In-service TVET teachers should act as TVET ambassadors for their pre-service TVET teachers, the majority of whom are likely to become TVET teachers themselves. That is, the intrinsic and altruistic motivations for choosing TVET teaching as a career must be adequately supported and nurtured during their time at the TVET teacher training institution, such as the faculty of vocational and technical education.

Limitations

The current study included some limitations that could be addressed in future research. The first flaw is that the study used a quantitative research design that relied solely on a questionnaire to investigate the motives of pre-service TVET teachers to teach, which makes inferences problematic. In the future, qualitative studies using in-depth interviews or narrative research could be conducted to fully understand the underlying reasons for the similarities and differences in pre-service TVET teachers’ motivation to teach, taking into account the benefits and drawbacks of quantitative research. However, the study, on the other hand, introduces scholars to some of the mechanisms that explain why pre-service TVET teachers select teaching as a career. Again, the study used self-report measures to respond to the questionnaire, which could contribute to significant bias. The study’s population was also a limitation. However, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the findings of this study beyond its original context. This is because it is recommended that a study with a larger scope and scale be done along the same lines to boost the report’s generalizability and better advise the included institutions’ hiring efforts. Again, it is widely acknowledged that motivation changes over time (Richardson et al., 2014; Han and Yin, 2016); however, the current study only looked at the motivation of preservice stage of TVET teachers. As a result, future research might look into how their motives changed as they progressed from preservice to in-service.

Conclusion

These findings of this study have advanced our knowledge of what motivates pre-service TVET teachers to select teaching as a life career by not just establishing a relationship in terms of similarities and differences in the types and ratings of the pre-service TVET teachers’ motivation but providing a new perspective in comparing the motivational uniqueness of pre-service TVET teacher to that of the general education teachers.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

NE created the topic and study theme, as well as the research framework, questionnaire design, and data analysis method, and was responsible for the finalization of the manuscript. ON was in charge of gathering information and compiling the questionnaire. AC, UO, EE, CnO, SO, CN, IoO, CdO, HA, InO, and EO handled the draft writing and drafting of the study research questions, data analysis, result discussion, literature acquisition, and data collecting and analysis. All authors contributed to the piece and gave their approval to the final edition.

Funding

This study was supported by the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) under the National Universities Commission of the Federal Government of Nigeria with PGC2020- 093891-B-C48. This study has been carried out through the funding of project entitled “Motivations to teach: A significance in enhancing hiring measures (15916/PI/20)”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agrawal, S., De Smet, A., Lacroix, S., and Reich, A. (2020). Adapting Employees’ Skills And Roles To The Post-Pandemic Ways Of Working Will Be Crucial To Building Operating-Model Resilience. Our insights. Atlanta: McKinsey & Company.

Alexander, C., Wyatt-Smith, C., and Anna, D. (2020). The role of motivations and perceptions on the retention of in-service teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 96:103186. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103186

Allen, K. A., Gray, D. L., Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (2022). The Need to Belong: A Deep Dive into the Origins, Implications, and Future of a Foundational Construct. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 1133–1156. doi: 10.1007/s10648-021-09633-6

Amanda, H., Fiona, L., David, B., and Misol, K. (2019). Perceptions of teachers and teaching in Australia. Available Online at: https://www.monash.edu/thankyour-teacher/docs/Perceptions-of-Teachers-and-Teaching-in-Australia-report-Nov-2019.pdf (accessed November 17, 2019).

Annette, R. P., Benjamin, M. T., and Doug, L. (2018). Motivational Differences Throughout Teachers’ Preparation and Career. New Waves Educ. Res. Dev 21, 26–45.

Arcangel, X. (2014). ‘DepEd to need 81k teachers for senior high school by 2016’. Gma news online. Available Online at: http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story (accessed June 30, 2014).

Ari, A., Jarmo, H., Hannu, H., and Juha, K. (2022). In search of the meaning of education: The case of Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 39, 295–309. doi: 10.1080/0031383950390402

Broton, K. M., and Goldrick-Rab, S. (2018). Going Without: An Exploration of Food and Housing Insecurity Among Undergraduates. Educ. Res. 47, 121–133. doi: 10.3102/0013189X17741303

Calimlim, C. (2011). “Plenary Paper on BSIE and BTTE vis-à-vis ICT,” in Proceedings of the 2nd National Congress on Industrial and Technology Education, (Manila).

Carrera, J. S., Brown, P., Brody, J. G., and Morello-Frosch, R. (2018). Research altruism as motivation for participation in community-centered environmental health research. Soc. Sci. Med. 196, 175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.028

Chang, L. (2020). Chinese EFL Learners’ Motivation Mediated by the Perceived Teacher Factors—Different Voices from Different Levels of Education. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 11, 920–930. doi: 10.17507/jltr.1106.07

Dawkins, P., Hurley, P., and Noonan, P. (2019). Rethinking And Revitalising Tertiary Education In Australia. Arlington: Mitchell Institute.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation And Self-Determination In Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Eccles, J. (1983). “Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors,” in Achievement And Achievement Motives: Psychological And Sociological Approaches, ed. J. T. Spence (San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman), 75–146.

Ekin, S., Yetkin, R., and Öztürk, S. Y. (2021). A Comparative study of career motivations and perceptions of student teachers. Turkish Stud. Educ. 16, 505–516. doi: 10.47423/TurkishStudies.47210

Elisabet, F., Adelina, M., Trinidad, L., Maria, A. S., Silvia, N., and Carmen, E. (2020). Content validation through Expert judgement of an instrument on the nutritional knowledge, belief and habits of pregnant women. Nutrition’s 12:1136. doi: 10.3390/nu12041136

European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training [Cedefop] (2020). Perceptions On Adult Learning And Continuing Vocational Education And Training In Europe. Second Opinion Survey – volume 1. Member states. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

Eze, N. U., Obichukwu, P. U., and Subodh, K. (2021). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use in ICT Support and Use for Teachers. IETE J. Educ. 62, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/09747338.2021.1908177

Fischer, C., Malycha, C. P., and Schafmann, E. (2019). The Influence of Intrinsic Motivation and Synergistic Extrinsic Motivators on Creativity and Innovation. Front. Psychol. 10:137. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00137

Gu, L., Wang, B., and Zhang, H. (2021). A Comparative Study of the Motivations to Teach Chinese Between Native and Non-native Pre-service CSL/CFL Teachers. Front. Psychol. 12:703987. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703987

Gul, R., Tahir, T., and UmbreenIshfaq. (2020). Teaching as A Profession, Exploring the Motivational Factors, and the Motives to Stay in the Field of Teaching. Elementary Educ. Online 19, 4560–4565. doi: 10.17051/ilkonline.2020.04.764861

Hajek, A., and König, H.-H. (2022). Level and correlates of empathy and altruism during the Covid-19 pandemic. Evidence from a representative survey in Germany. PLoS One 17:e0265544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265544

Han, J., and Yin, H. (2016). Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Educ. 3:1217819.

Han, J., Yin, H., and Boylan, M. (2016). Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Educ. 3:1. (Reviewing Editor).

Hana, V., Jane, J., Angie, M., Irem, A., and Hasan, S. (2021). A review of recent research in EFL motivation: Research trends, emerging methodologies, and diversity of researched populations. System 103:102622. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102622

Helen, M. G. W., Paul, W. R., Uta, K., and Jürgen, B. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FIT-Choice scale. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 791–805. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.03.003

Hiver, P., Kim, T.-Y., and Kim, Y. (2018). “Language teacher motivation,” in Language Teacher Psychology, eds S. Mercer and A. Kostoulas (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 18–33.

Howes, L. M., and Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2015). Teachers’ career decisions: Perspectives on choosing teaching careers, and on staying or leaving. Issues Educ. Res. 25, 18–35.

Ibrahim, B. (2014). Pre-service Elementary Teachers’ Motivations to Become a Teacher and its Relationship with Teaching Self-efficacy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 152, 653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.258

Iraz, H. K. (2016). Motivation Factors of Consumers’ Food Choice. Food Nutr. Sci. 07, 149–154. doi: 10.4236/fns.2016.73016

John, K. A. (2020). Preparing Globally Competent Teachers: A Paradigm Shift for Teacher Education in Ghana. Educ. Res. Int. 2020:8841653. doi: 10.1155/2020/8841653

Joyce, S. (2019). Strengthening Skills: Expert Review Of Australia’s Vocational Education And Training System. Canberra: Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Kavanoz, S., and Yüksel, H. G. (2017). Motivations and Concerns: Voices from Pre-service Language Teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 43–61. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2017v42n8.4

Kissau, S., Davin, K., Wang, C., Haudeck, H., Rodgers, M., and Du, L. (2019). Recruiting foreign language teachers: An international comparison of career choice influences. Res. Compar. Int. Educ. 14, 184–200. doi: 10.1177/1745499919846015

Kolleck, N. (2019). Motivational Aspects of Teacher Collaboration. Front. Educ. 4:122. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00122

Lauro, E. E., Manuel, S. L., and Lucia, P. L. (2019). “Industrial Technology Students Competency Level Under the Ladderized Education Program (LEP),” in Journal Of Physics: Conference Series. 1st Upy International Conference On Applied Science And Education 2018, (Yogyakarta), 24–26.

Liu, H., Lixiang, G., and Fan, F. (2020). Exploring and Sustaining Language Teacher Motivation for Being a Visiting Scholar in Higher Education: An Empirical Study in the Chinese Context. Sustainability 12, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/su12156040

Maddocks, S., Klomp, N., Bartlett, H., Bean, M., Kristjanson, L., and Dawkins, P. (2019). Reforming Post-Secondary Education In Australia: Perspectives From Australia’s Dual Sector Universities. Darwin: Charles Darwin University.

Maliki, A. E. (2013). Attitudes towards the teaching profession of students from the faculty of education, Niger Delta University. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 1, 11–18.

Manuela, H. (2015). Why choose teaching? An international review of empirical studies exploring student teachers’ career motivations and levels of commitment to teaching. Educ. Res. Eval. 21, 258–297. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2015.1018278

Masbirorotni, M., Mukminin, A., Muhaiminrer, N., Habibi, A., Haryanto, E., Hidayat, M., et al. (2020). Why student teachers major in english education: an analysis of motives for becoming future teachers. J. Elem. Educ. 13, 429–452. doi: 10.18690/rei.13.4.429-452.2020

Matthew, L., Caitlyn, P., Christina, M. P., and Linda, J. H. (2022). Motivational state-dependent renewal and reinstatement: Discriminative and motivational functions of food deprivation and satiation states. Learn. Motiv. 79:101820. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2022.101820

Michael, T. K. (2021). Alpha, Omega, and H internal consistency reliability estimates: Reviewing these options and when to use them. Couns. Outcome Res. Eval. 12, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118

Mohammadabadi, A. M., Ketabi, S., and Nejadansari, D. (2019). Factors influencing language teacher cognition: An ecological systems study. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 657–680. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.4.5

Muhonen, J. (2004). Second Language De-Motivation: Factors That Discourage Pupils From Learning The English Language. Ph.D. thesis, Jyväskylä: University of Jyvaskyla.

National Board for Technical Education [NBTE] (2014). Guidelines and Procedures for the establishment of Private Technical and Technological Institutions in Nigeria. Kaduna: National Board for Technical Education.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2019). Australia country note: Results from TALIS 2018 volume 1. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Parker, S., Dempster, A., and Warburton, M. (2018). Reimagining Tertiary Education: From Binary System To Ecosystem. Sydney: KPMG Australia.

Pintrich, P., Smith, D., Garcia, T., and McKeachie, W. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). Educ. Psychol. Meas. 53, 801–813. doi: 10.1177/0013164493053003024

Ricarda, S., Anne, F. W., Malte, S., and Birgit, S. (2019). The Importance of Students’ Motivation for Their Academic Achievement – Replicating and Extending Previous Findings. Front. Psychol. 10:1730. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01730

Richardson, P. W., Karabenick, S. A., and Watt, H. M. G. (eds) (2014). Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice. Milton Park: Taylor and Francis.

Roger, H., and Berwyn, C. (2020). The value of vocational education and training. Int. J. Train. Res. 18, 185–190. doi: 10.1080/14480220.2020.1860309

Saks, K., Soosaar, R., and Ilves, H. (2019). “The Students’ Perceptions and Attitudes to Teaching Profession, the Case of Estonia,” in ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, eds Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, and R. X. Thambusamy (Irvine: Future Academy), 470–481. doi: 10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.48

Sharif, T., Hossan, C. G., and McMinn, M. (2014). Motivation and Determination of Intention to Become Teacher: A Case of B.Ed. Students in UAE. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 9, 60–73.

Shih, C.-M. (2016). Why do they want to become English teachers: A case study of Taiwanese EFL teachers. Perspect. Educ. 34, 43–44. doi: 10.18820/2519593X/pie.v34i3.4

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 21, 1251–1275. doi: 10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8

Steffensen, S. V., and Kramsch, C. (2017). “The ecology of second language acquisition and socialization,” in Language Socialization, 3rd Edn, eds P. A. Duff and S. May (Cham: Springer), 17–32.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] (2018). Skills For Work And Life. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Usman, K. A., Doreen, A., and Austin, W. L. (2021). Motivation of pre-service teachers in the colleges of education in Ghana for choosing teaching as a career. Cogent Educ. 8:1870803. doi: 10.1088/2331186X.2020.1870803

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., and Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and a motivation in education. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 52, 1003–1017. doi: 10.1177/0013164492052004025

Valles, M. C. (2012). “Keynote Speech on ‘Thrusts and Directions for Bachelor of Science in Industrial Education (BSIE) and Bachelor of Technical Teacher Education (BTTE) vis-à-vis’ K to 12 Program,” in Proceedings of the 3rd National Congress on Industrial and Technology Education, (Manila).

Viac, C., and Fraser, P. (2020). “Teachers’ well-being: A framework for data collection and analysis (Issue 213),” in OECD Education Working Papers 213, (Paris: OECD Publishing), doi: 10.1787/c36fc9d3-en

Wang, W., and Bale, J. (2019). Mentoring for new secondary Chinese language teachers in the United States. System 84, 53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.05.002

Wang, Y., Jianqiao, G., Hanqi, Z., Haixia, W., and Xiaofei, X. (2019). Altruistic behaviors relieve physical pain. Psychol. Cogn. Sci. 117, 950–958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911861117

Wangbei, Y., Yingying, D., Xiaomeng, H., and Wangqiong, Y. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ teaching motivation and perceptions of teacher morality in China. Educ. Stud. 48, 2–19. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2022.2037406

Yaghoubinejad, H., Zarrinabadi, N., and Nejadansari, D. (2017). Culture-specificity of teacher demotivation: Iranian junior high school teachers caught in the newly-introduced CLT trap! Teach. Teach. 23, 127–140. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1205015

Yang, H. (2021). Epistemic agency, a double-stimulation, and video-based learning: A formative intervention study in language teacher education. System 96:102401. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102401

Yuce, K., Sahin, E. Y., Kocer, O., and Kana, F. (2013). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: A perspective of pre-service teachers from Turkish context. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 14, 295–306. doi: 10.1007/s12564-013-9258-9

Keywords: career choice, career development, motivations, pre-service TVET teachers, TVET teachers’ recruitment, teaching, TVET teacher preparation

Citation: Eze N, Nwadi C, Onodugo I, Ozioko E, Osondu S, Nwosu O, Chilaka A, Obichukwu U, Anorue H, Onyishi I, Eze E, Onyemachi C and Onyemachi C (2022) Occupational decision motives of potential TVET teachers: New standards of pre-service TVET teachers’ recruitment and career development. Front. Educ. 7:883340. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.883340

Received: 24 February 2022; Accepted: 22 July 2022;

Published: 25 August 2022.

Edited by:

Paula A. Cordeiro, University of San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Milan Kubiatko, J. E. Purkyne University, CzechiaAli Selamat, University of Technology Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Eze, Nwadi, Onodugo, Ozioko, Osondu, Nwosu, Chilaka, Obichukwu, Anorue, Onyishi, Eze, Onyemachi and Onyemachi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Calister Nwadi, Y2FsaXN0ZXIubndhZGlAdW5uLmVkdS5uZw==

Nicholas Eze

Nicholas Eze Calister Nwadi2*

Calister Nwadi2* Ifeoma Onodugo

Ifeoma Onodugo Stella Osondu

Stella Osondu Uzochukwu Obichukwu

Uzochukwu Obichukwu Honesta Anorue

Honesta Anorue Emmanuel Eze

Emmanuel Eze