- 1Department of Behavioral Sciences, Kinneret Academic College on the Sea of Galilee, Tzemach, Israel

- 2Department of Education, The Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel, Jezreel, Israel

- 3Department of Education and Community, Kinneret Academic College on the Sea of Galilee, Tzemach, Israel

- 4Faculty of Education, Tel-Hai College, Kiryat Shmona, Israel

The need for interaction that arose given the social distancing imposed on people by governments during the COVID-19 has increased the use of social media (SM). The current study distinguishes between two different patterns of SM use: problematic and intensive, and examines the impact of each specific type of SM on social and mental aspects (i.e., social support, loneliness, and life satisfaction). The sample included 363 higher education students. Data were gathered during a second lockdown using Partial Least Squares—Structural Equation Modeling. The model indicated two different trajectories corresponding to the two types of SM users: Intensive users reported having more family support, whereas problematic users tended to feel lonely, reported having low life satisfaction, and had less support from friends. This study may allude to the possible positive role of SM use, especially during social distancing, in alleviating social and mental burdens in times of crisis.

Introduction

In December 2019, the eruption of the COVID-19 began worldwide. The response to the outbreak of the virus was, among other things, a reduction in mobility, a restriction of multi-participant meetings, and a closure imposed by governments that required people to stay at home and, therefore, carry out all actions via the internet. Thus, work, learning, leisure, and communication were done almost absolutely online. Consequently, more than half a billion new users joined social media (SM) platforms between 2020 and 2021 (Kemp, 2021). Furthermore, in a study conducted during the pandemic’s early stages, high SM usage levels were reported among the overall population (Geçer et al., 2020).

SM use in times of health crisis, as in the COVID-19 pandemic, can be highly intensive. Previous findings suggested that stressful life events were associated with problematic internet use (Zheng et al., 2022). On the other hand, the easiness of accessing information and sharing it with others and the sense of social cohesion and social support drew people to stay connected through SM (Arslan et al., 2021). Previous studies on SM use during the spread of the COVID-19 yielded mixed findings regarding the consequences of their use. Some have shown that using SM, such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and YouTube, has helped individuals find information and gain support (e.g., Saud et al., 2020), while others have associated SM use with loneliness and depression (e.g., Boursier et al., 2020; Lisitsa et al., 2020). While the previous study demonstrated the association between different content exposure through the internet to psychological outcomes (Zhang et al., 2022), the present study seeks to distinguish between two types of SM use: intensive and problematic. Therefore, we aim to identify the specific implication of each pattern of SM use for individuals’ social and mental aspects (i.e., social support, loneliness, and life satisfaction) during the closure.

Furthermore, emotional regulation may decline in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 outbreak. A previous study conducted among academic students during the pandemic indicated a decline in emotional regulation (Panayiotou et al., 2021). As a result, life satisfaction, defined as the degree to which a person positively evaluates the overall quality of his/her life as-a-whole (Veenhoven, 1996), can be severely hampered (Zhang et al., 2020; Panayiotou et al., 2021). Lathabhavan and Sudevan (2022) proved to show the association between depression, anxiety and stress on low life satisfaction during two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. In their systematic review, Gioia et al. (2021) concluded that problematic internet use, including SM addiction, might represent a coping strategy to compensate for emotional regulation deficits. However, it is essential to examine components that may be associated with high life satisfaction in times of crisis, that is, at the time of the eruption of the COVID-19 and the closures imposed. Therefore, the following study investigated whether social media use can be linked to high life satisfaction.

Moreover, whereas previous studies have underscored the associations between loneliness, social support, and life satisfaction (Kong and You, 2013), this study addresses familial supportive patterns, an underexplored construct of social support. Family support is especially significant during a health crisis. Therefore, we aim to reveal the link between this construct and SM use in times of social distancing during a health crisis. This study may help identify the positive role of SM use during a crisis and suggest ways to mitigate its negative implications.

Problematic Social Media Use vs. Intensive Social Media Use: Implications on Social and Mental Aspects

Problematic SM use is based on the DSM-5 criteria for substance dependence and pathological gambling. Specifically, it refers to the components of relapse, preoccupation, withdrawal, mood modification, tolerance, and external consequences (Petry et al., 2014). In addition, there is scientific evidence of significant associations between problematic SM use (e.g., Facebook) and a decrease in mental health aspects, such as anxiety, depression, stress, and low wellbeing, already before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Błachnio et al., 2016; Hawi and Samaha, 2017; Shakya and Christakis, 2017), and during the outbreak, among young-adults (general SM use; Geirdal et al., 2021; and specific local SM platform; Zhao and Zhou, 2020).

It is well documented in the research literature that problematic SM use can deteriorate social relationships. For example, in their longitudinal study, Marttila et al. (2021) found that the problematic use of SM increased loneliness, which lowered life satisfaction over time. In another study (Baltaci, 2019), a significant association was found between problematic SM use and loneliness, particularly among university students. Finally, a study conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak revealed that younger adults (18–35) were lonelier than older adults and showed a more significant increase in SM use (Lisitsa et al., 2020). Gómez-Galán et al. (2020) support this finding in their study, showing that college students presented a high consumption of SM during the COVID-19 outbreak, with significant incidences of addiction. Furthermore, Boursier et al. (2020) suggested in their study that participants reported greater use of social media due to their feelings of loneliness during the closures. In addition, addiction-like use of social media results in more significant anxiety.

Intensive SM use is characterized by the amount of usage time. While problematic SM use points to compulsive behavior with harmful consequences for social and mental aspects (Keles et al., 2020), intensive use of SM is not necessarily pathological. The association between intensive SM use and social and mental aspects is complex, not linear, and poses mixed implications (Przybylski and Weinstein, 2017; Boer et al., 2020; Masur, 2021). However, according to Boer et al.’s (2020) extensive study, users reported higher levels of family support and life satisfaction in countries with a higher prevalence of intense SM use. Moreover, from a social point of view, engagement in SM, not in an addictive manner, may facilitate social connectedness (Allen et al., 2014; Radovic et al., 2017). Drawing on the Stimulation Hypothesis, communication through SM leads to more face-to-face interactions because it encourages contact with close social circles (Kuntsche et al., 2009; Valkenburg and Peter, 2011). Kaya’s (2020) study also presented the positive side of SM use during the COVID-19 outbreak. Although the use of SM increased, it helped get information, update, and keep in touch and, therefore, was not associated with anxiety.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to contribute to the corpus of knowledge by presenting the potential effects of different characteristics of SM usages (problematic and intensive) on social and mental wellbeing. We intended to do so by investigating the following hypotheses: problematic SM use will be negatively linked to social support (H1) and life satisfaction (H2); and positively associated with loneliness (H3). In addition, intensive use of SM will be associated with increased levels of social support (H4), life satisfaction (H5) and decreased levels of loneliness (H6).

Materials and Methods

Sample

The sample included 363 students in various higher education institutions in Israel (Mean age 26.9, SD = 5.55; 67% females), of whom 54% resided in cities while the others reported living in small settlements (e.g., Kibbutz, village). Regarding family status: 55% reported being single, 26% declared being in relationships without children, 17.5% were married with children, and less than 2% reported being divorced. Regarding ethnicity, 20% were Arab students, and 80% were Jewish students. In addition, 69% were undergraduate students, and 31% were master’s degree students. Forty percent lost their job due to the closure, 13% reported that their number of working hours had been reduced, and others had no change. Twelve percent of respondents lived alone during the lockdown, while others lived with their families (52%) or roommates/partners (36%). Regarding COVID-19-related items, 5% were infected by COVID-19 according to their reports, and 19% confirmed that one of their family members was infected by COVID-19.

Measurements

Problematic Social Media use

Based on the Social Media Disorder Scale (van den Eijnden et al., 2016), the following measurement was used to pinpoint the respondents’ displaying signs of PSMU. The instruction for answering included a clarification for the term SM as follows: “The term social media refers to social network sites (e.g., Facebook) and instant messengers (e.g., WhatsApp).” The scale consists of nine items. On a binary response (yes/no) scale, the respondents indicated whether they experienced symptoms such as “regularly neglecting other activities” during the past six months. Six or more positive answers suggested that the respondent is a problematic user (recorded as 1); others were recorded as 0. This measure has been validated across 44 countries, including Israel, and found to be adequate (Boer et al., 2022).

Intensive Social Media Use

This questionnaire (Mascheroni et al., 2013) comprises four items that measure the frequency of students’ online contact via social media with close friends, friends from a larger friend group, friends whom they met through the internet, and other people. All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never/almost never to 5 = almost all the time throughout the day. In line with previous studies, the respondents’ answers were recoded (Boer et al., 2020, 2022): those who answered “almost all the time throughout the day” on at least one item were classified as 1 = intense user, and the rest were classified as 0 = non-intense users. The measure has been used previously in Israel after a validation process (e.g., Boniel-Nissim et al., 2022).

Life Satisfaction

This single-item measure (Cantril, 1965) assesses participants’ rate of life satisfaction on a scale ranging from 0 = worst possible life to 10 = best possible life. This measure has good reliability (Levin and Currie, 2014) and has been used in other studies in Israel after a validation process (e.g., Boer et al., 2020). Higher scores indicate higher life satisfaction.

Social Well-Being

Two four-item scales were used based on the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet et al., 1988) to assess social wellbeing. The first subscale includes friend support, in which participants were asked to rate their agreement with items such as “I can count on my friends when things go wrong” (α = 0.95). The second measured family support, for example, “I can talk about problems with my family” (α = 0.92). All items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. This measure has been used in other studies in Israel after a validation process (e.g., Boer et al., 2020).

Loneliness

This three-item scale (Russell, 1996) measured respondents’ feelings of loneliness during lockdowns. Items such as “I felt lonely” were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = never to 4 = always (α = 0.65). The measure has been used before in other Israeli studies and presents good reliability (e.g., Ginter et al., 1996; Efrati and Amichai-Hamburger, 2019).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using analyses of variance to compare variances across the means of different groups and PLS-SEM. Whereas CB-SEM is primarily used to confirm a founded theory, PLS is a prediction-oriented approach to SEM, mainly for exploratory research. Therefore, advised being employed if the primary objective of applying structural equation modeling is the prediction of target constructs (Hair et al., 2017). SmartPLS 3 software was used.

Procedure

COVID-19 spread in Israel in March 2020, leading to several restrictions and frequent total closures, thrusting the higher education system into e-learning until March 2021. The questionnaires in the present study were distributed to students from October-November 2020 when students could not attend on-campus classes. After receiving approval from the Ethics Committee, the research tools were entered into a built-in questionnaire site. The opening of the questionnaire included an explanation of the study, the researchers’ contact details and a promise to maintain anonymity and that the answer is voluntary. The link to the questionnaire was sent to five academic study institutions in the country through lecturers and department heads.

Findings

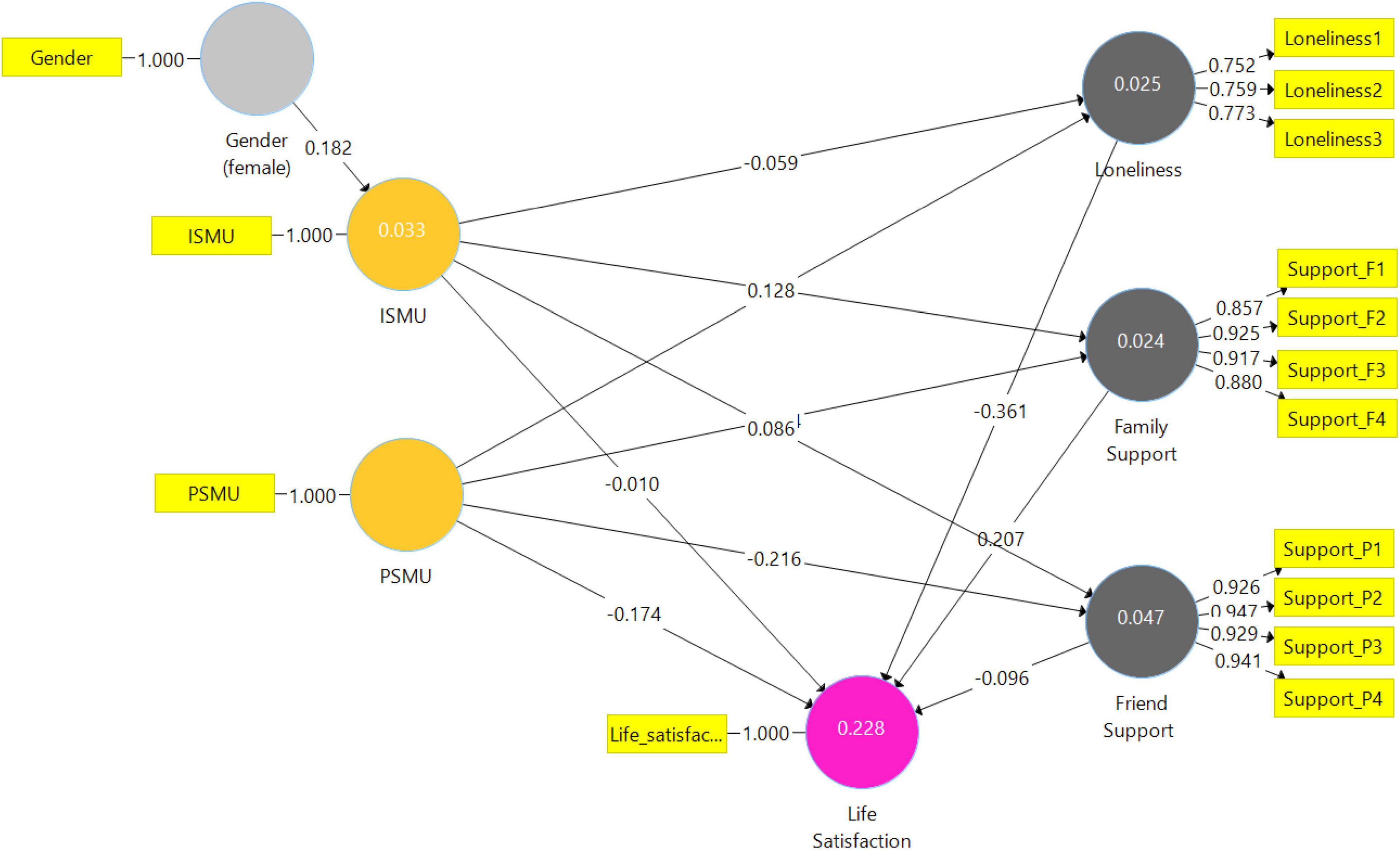

To assess H1—H6, Model 1 (Figure 1) was constructed. This path model includes seven constructs, represented in the model as cycles: Loneliness, Family Support, Friend Support, Life Satisfaction, Intensive SM use (ISMU), Problematic social media use (PSMU), and Gender (female). It should be noted that all constructs were regressed on all the background variables (detailed in the sample description(, however, only Gender was significantly related to ISMU, therefore was entered into the model. The indicators are the directly measured proxy variables, represented as rectangles. The relationships between the constructs and their assigned indicators are shown as arrows. In PLS-SEM, single-headed arrows, as shown between the constructs, are considered predictive relationships and, with solid theoretical support, can be construed as causal relationships. As shown in Figure 1, paths were specified based on the proposed hypotheses.

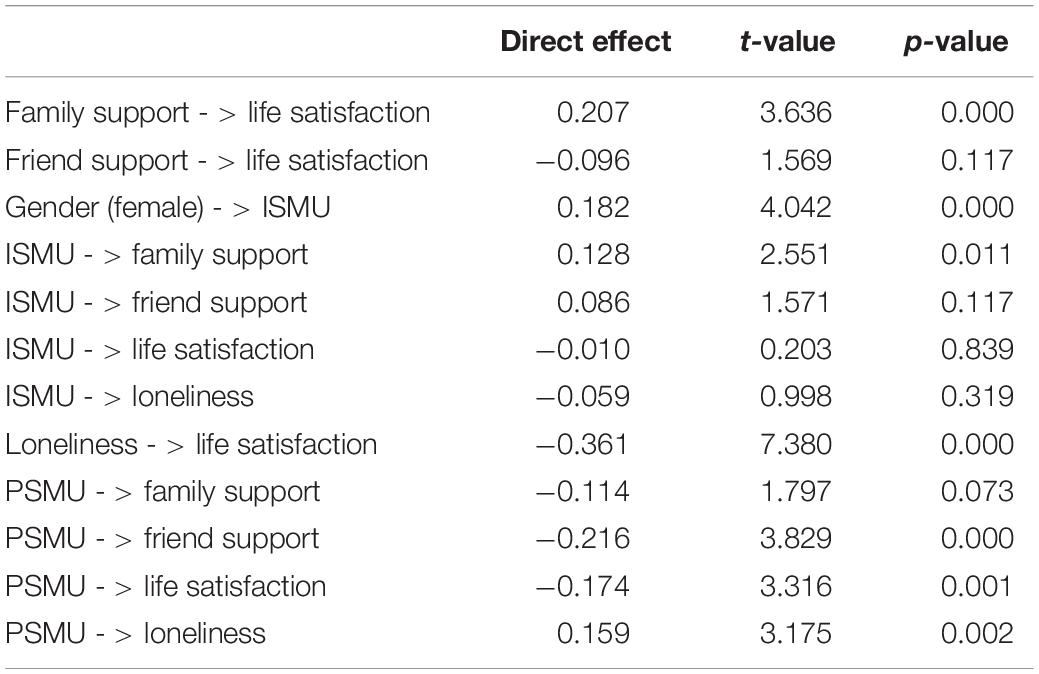

Table 1 presents the analysis results of the direct effects. As shown in the table, PSMU was negatively connected to Friend Support, whereas a non-significant result was indicated between PSMU and Family Support; hence H1 was partially corroborated. PSMU was negatively correlated to Life Satisfaction; thus, H2 was confirmed. PSMU was positively related to Loneliness; therefore, H3 was corroborated.

Regarding ISMU, this independent variable was significantly linked only to Family Support. Therefore, H4 was partially corroborated, and hypotheses H5 and H6 were not confirmed. Lastly, females reported using SM more intensively than males.

Model Evaluation

Collinearity was examined by the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values of all sets of predictor constructs in the structural model. The results showed that the VIF values of all combinations of endogenous and exogenous constructs are below the threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2017), ranging from 1.000 to 1.620. Hence, collinearity among the predictor constructs is not critical in the following structural model.

We investigated the coefficient of determination (R2) value. R2 for Family Support (0.024), Friend Support (0.047), ISMU (0.033), and Loneliness (0.025) were rather weak. However, a relatively higher result was found for Life Satisfaction (0.228). In addition, in order to measure the R2 values, the change in the R2 value when a specified exogenous construct is removed from the model was used to evaluate its impact on the endogenous constructs. This measure is referred to as the f2 effect size when values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, represent small, medium, and large effects. Low effect size results were found between ISMU and the dependent variables, ranging from 0 to 0.016. f2 results for PSMU and the dependent variables were relatively higher, ranging from 0.013 to 0.047, yet still considered weak. Finally, the path model’s predictive relevance (Q2) was assessed. Values larger than 0 suggest that the model has predictive relevance for a particular endogenous construct (Hair et al., 2017). The highest Q2-value was indicated for Life Satisfaction Q2 = 0.203, whereas somewhat lower values were suggested for Family Support (0.018), Friend Support (0.039), and Loneliness (0.014).

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak made life challenging. For higher education students, the absence from campus limited the possibility for social gatherings and decreased their sense of belonging and the opportunity to receive support from their classmates (Arslan et al., 2021). As a result, many have overused SM for social and emotional gratifications to fill this void. The present study aimed to examine how different patterns of SM use might be associated with social support and life satisfaction.

As postulated, our results indicated that intensive SM use differs significantly in its implications on social support and life satisfaction from problematic SM use. Students who were identified as intensive SM users reported receiving support from their families. In this context, it might be inferred that SM acts as a platform for communication with family members. Moreover, since the COVID-19 affected older people more severely (Raifman and Raifman, 2020), it is plausible to assume that young people (namely students in the current research) will tend to contact their families. More so when one of the family members is at risk of being infected (in the present sample, 19% confirmed that one of their family members was infected by COVID-19).

On the other hand, the speculated positive association between intensive SM use and peer support was not corroborated nor hypothesized negative association with loneliness. This can be explained by the fact that only 12% of the students in the sample reported they lived alone during the lockdown. Therefore, it is possible that many students had a source of support and togetherness, which eliminated the need to rely solely on SM. Another explanation can be stressed from the anxiety-buffer hypothesis (Greenberg et al., 1992) suggests that self-esteem is a buffer against mental health threats. Rossi et al. (2020) point out in their study, conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak, that self-esteem mediated the relationship between loneliness and depression. Therefore we suggest further investigation of protective factors.

Moreover, the positive association between intensive SM use and life satisfaction was not corroborated. Previous studies stressed the difficulty of confirming this association (Masur, 2021). Therefore, it is plausible to assume, especially in times of health crises, that there might be confounders, such as psychological distress and fear of COVID-19 (e.g., Trzebiński et al., 2020) which are needed to be considered. In addition, as stressed before, it is essential to differentiate between passive and active use to understand better the impact of SM use (Masur, 2021). Therefore, future research should investigate how the various levels of activities enabled by SM shape individuals’ life satisfaction.

Regarding problematic SM users, these students felt lonely, got significantly less support from their friends, and reported low life satisfaction. These findings are consistent with previous studies on loneliness, associating this variable with passive SM use, which may, in turn, predict lower social support (Wang et al., 2018). As stressed in previous studies (e.g., Panayiotou et al., 2021), the period of the COVID-19 outbreak was stressful arousing emotional dysregulation. Therefore, it is possible that lack of social support (from family and friends) negatively affects emotional regulation abilities, resulting in problematic use of SM (Gioia et al., 2021). This vicious cycle may be manifested in low life satisfaction.

Therefore, it might be concluded that while intensive SM use acts mainly as a tool for social communication, connecting individuals to their family members during times of health crisis, problematic SM use is associated with pathological behavior (Petry et al., 2014), and therefore was found connected to decreased levels of mental and social aspects.

Limitations

The strength of the current study lies in its rich data collection at the time of closure among a diverse academic student population. However, this study has several limitations we would like to address. First, this study used a convenience sample, and for this reason, despite its sectoral diversity, it does not fully represent the population. Second, the present study addressed the use of SM only, and no other digital applications (such as computer games) that might be perceived as communication conduits were examined. Thus, follow-up studies should explore patterns of additional internet applications usages and their relationship to mental and social wellbeing. Third, the term SM has been used in the present study, referring to SM in general (meaning not a specific platform as Twitter or Instagram). Therefore, it is essential to continue a study that will examine particular SM platforms to examine whether the type of platform has an effect.

Conclusion

A wide range of research indicates that SM use has increased following the physical distancing imposed by governments in response to COVID-19 (Bowden-Green et al., 2021). This study explored the motives for SM use under lockdown conditions and elaborated on previous work by distinguishing between two types of SM users. The first is the intensive user. Such users seek out SM to satisfy their needs for social interaction, specifically with their family, during times of social distancing. Based on the Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al., 1973), it can be assumed that intensive users are aware of their motives, which in this case can be defined as “social” (due to the social distancing) motives that created a need for intensive media use, to satisfy requirements such as belonging or keeping in close touch with family members who might have been at risk of illness. Hence, it seems plausible to assume that the intensive users actively selected SM platforms to satisfy their social interaction needs. In contrast to intensive SM users, the second type of users, defined as problematic, might have different motives for SM overuse that can be linked to pathological characteristics. Addictive-like behavior is linked to isolation from society. In this case, SM acts as an escape tool from the world and not a means for social connectedness and social support (Baltaci, 2019).

Practical Implications

It might be beneficial for clinicians to identify individuals prone to problematic SM use by probing for underlying mental health difficulties that prompt excessive SM use among individuals. Problematic SM use should be considered a priori, and prevention strategies for dealing with this addictive-like behavior should be offered more intensively during times of instability and social distancing. These efforts should include raising awareness among young people concerning mental health difficulties and disseminating information regarding available public health resource centers and networks that offer information and practical assistance. Moreover, public health practitioners should consider devising programs aimed at helping problematic SM users to learn coping strategies for dealing with emotional and social difficulties than merely heavily relying on SM.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Kinneret Academic College Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MB-N: construction of the research plan, selection of research tools, responsible for data collection, and writing the manuscript. DA: construction of the research plan, statistical analysis, and writing the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the Kinneret Academic College.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, K. A., Ryan, T., Gray, D. L., McInerney, D. M., and Waters, L. (2014). Social media use and social connectedness in adolescents: the positives and the potential pitfalls. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 31, 18–31.

Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., and Zangeneh, M. (2021). Coronavirus anxiety and psychological adjustment in college students: exploring the role of college belongingness and social media addiction. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00460-4

Baltaci, Ö. (2019). The predictive relationships between the social media addiction and social anxiety, loneliness, and happiness. Int. J. Prog. Educ. 15, 73–82.

Błachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., and Pantic, I. (2016). Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 701–705. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.026

Boer, M., van den Eijnden, R. J., Finkenauer, C., Boniel-Nissim, M., Marino, C., Inchley, J., et al. (2022). Cross-national validation of the social media disorder scale: findings from adolescents from 44 countries. Addiction 117, 784–795. doi: 10.1111/add.15709

Boer, M., van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S.-L., Inchley, J. C., Badura, P., et al. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their wellbeing in 29 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 66, S89–S99. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.014

Boniel-Nissim, M., van den Eijnden, R. J., Furstova, J., Marino, C., Lahti, H., Inchley, J., et al. (2022). International perspectives on social media use among adolescents: implications for mental and social well-being and substance use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 129:107144.

Boursier, V., Gioia, F., Musetti, A., and Schimmenti, A. (2020). Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: the role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Front. Psychiatry 11:586222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222

Bowden-Green, T., Hinds, J., and Joinson, A. (2021). Personality and motives for social media use when physically distanced: a uses and gratifications approach. Front. Psychol. 12:607948. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.607948

Efrati, Y., and Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2019). The use of online pornography as compensation for loneliness and lack of social ties among Israeli adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 122, 1865–1882. doi: 10.1177/0033294118797580

Geçer, E., Yıldırım, M., and Akgül, Ö. (2020). Sources of information in times of health crisis: evidence from Turkey during COVID-19. J. Public Health 30, 1113–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01393-x

Geirdal, A. Ø., Ruffolo, M., Leung, J., Thygesen, H., Price, D., Bonsaksen, T., et al. (2021). Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. a cross-country comparative study. J. Ment. Health 30, 148–155. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.1875413

Ginter, E. J., Lufi, D., and Dwinell, P. L. (1996). Loneliness, perceived social support, and anxiety among Israeli adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 79, 335–341. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.1.335

Gioia, F., Rega, V., and Boursier, V. (2021). Problematic internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: a literature review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 18, 41–54. doi: 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210104

Gómez-Galán, J., Martínez-López, J. Á., Lázaro-Pérez, C., and Sarasola Sánchez-Serrano, J. L. (2020). Social networks consumption and addiction in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: educational approach to responsible use. Sustainability 12:7737.

Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., Rosenblatt, A., Burling, J., Lyon, D., et al. (1992). Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 913–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.913

Hair, J. F. Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., and Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivariate Data Anal. 1, 107–123.

Hawi, N. S., and Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 35, 576–586.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., and Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin. Q. 37, 509–523.

Kaya, T. (2020). The changes in the effects of social media use of Cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 63:101380. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101380

Keles, B., McCrae, N., and Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 79–93. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Kemp, S. (2021). Digital in 2021: 60 Percent of the World’s Population is Now Online. Available online at: https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2021/04/60-percent-of-the-worlds-population-is-now-online (accessed April 26, 2021).

Kong, F., and You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Soc. Indic. Res. 110, 271–279.

Kuntsche, E., Simons-Morton, B., Ter Bogt, T., Queija, I. S., Tinoco, V. M., De Matos, M. G., et al. (2009). Electronic media communication with friends from 2002 to 2006 and links to face-to-face contacts in adolescence: an HBSC study in 31 European and North American countries and regions. Int. J. Public Health 54, 243–250. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5416-6

Lathabhavan, R., and Sudevan, S. (2022). The impacts of psychological distress on life satisfaction and wellbeing of the Indian general population during the first and second waves of COVID-19: a comparative study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00735-4

Levin, K. A., and Currie, C. (2014). Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the Cantril Ladder for use with adolescent samples. Soc. Indic. Res. 119, 1047–1063.

Lisitsa, E., Benjamin, K. S., Chun, S. K., Skalisky, J., Hammond, L. E., and Mezulis, A. H. (2020). Loneliness among young adults during covid-19 pandemic: the mediational roles of social media use and social support seeking. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 39, 708–726.

Marttila, E., Koivula, A., and Räsänen, P. (2021). Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 59:101556.

Mascheroni, G., Ólafsson, K., Cuman, A., Dinh, T., Haddon, L., Jørgensen, H., et al. (2013). Mobile Internet Access and Use Among European Children: Initial Findings of the Net Children Go Mobile project. Milan: Educatt.

Masur, P. K. (2021). “Digital communication effects on loneliness and life satisfaction,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, ed. J. Nussbaum (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052619

Panayiotou, G., Panteli, M., and Leonidou, C. (2021). Coping with the invisible enemy: the role of emotion regulation and awareness in quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 19, 17–27.

Petry, N. M., Rehbein, F., Gentile, D. A., Lemmens, J. S., Rumpf, H. J., Mößle, T., et al. (2014). An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction 109, 1399–1406. doi: 10.1111/add.12457

Przybylski, A. K., and Weinstein, N. (2017). A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: quantifying the relations between digital screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychol. Sci. 28, 204–215.

Radovic, A., Gmelin, T., Stein, B. D., and Miller, E. (2017). Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. J. Adolesc. 55, 5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.002

Raifman, M. A., and Raifman, J. R. (2020). Disparities in the population at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and income. Am. J. Prev. Med. 59, 137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.003

Rossi, A., Panzeri, A., Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, G. M., Castelnuovo, G., and Mannarini, S. (2020). The anxiety-buffer hypothesis in the time of COVID-19: When self-esteem protects from the impact of loneliness and fear on anxiety and depression. Front. Psychol. 11:2177. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02177

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 66, 20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

Saud, M., Mashud, M. I., and Ida, R. (2020). Usage of social media during the pandemic: seeking support and awareness about COVID-19 through social media platforms. J. Public Aff. 20:e2417.

Shakya, H. B., and Christakis, N. A. (2017). Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: a longitudinal study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 185, 203–211. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww189

Trzebiński, J., Cabański, M., and Czarnecka, J. Z. (2020). Reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic: the influence of meaning in life, life satisfaction, and assumptions on world orderliness and positivity. J. Loss Trauma 25, 544–557.

Valkenburg, P. M., and Peter, J. (2011). Online communication among adolescents: an integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. J. Adolesc. Health 48, 121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020

van den Eijnden, R. J., Lemmens, J. S., and Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The social media disorder scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 61, 478–487.

Veenhoven, R. (1996). “The Study of Life Satisfaction,” in A comparative study of satisfaction with life in Europe, eds W. E. Saris, R. Veenhoven, A. C. Scherpenzeel, and B. Bunting (Budapest: Eötvös University Press).

Wang, J. L., Gaskin, J., Rost, D. H., and Gentile, D. A. (2018). The reciprocal relationship between passive social networking site (SNS) usage and users’ users’ subjective well-being. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36, 511–522. doi: 10.1177/0894439317721981

Zhang, S., Liu, T., Liu, X., and Chao, M. (2022). Network analysis of media exposure and psychological outcomes during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00738-1

Zhang, S. X., Wang, Y., Rauch, A., and Wei, F. (2020). Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: health, distress, and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 288:112958. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958

Zhao, N., and Zhou, G. (2020). Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. Appl. Psychol. 12, 1019–1038. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12226

Zheng, X., Chen, J., Li, C., Shi, S., Yu, Q., Xiong, Q., et al. (2022). The influence of stressful life events on adolescents’ problematic internet use: the mediating effect of self-worth and the moderating effect of physical activity. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00758-5

Keywords: problematic social media use (PSMU), intensive social media use, COVID-19, social support, life satisfaction

Citation: Boniel-Nissim M and Alt D (2022) Problematic Social Media Use and Intensive Social Media Use Among Academic Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations With Social Support and Life Satisfaction. Front. Educ. 7:876774. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.876774

Received: 15 February 2022; Accepted: 12 May 2022;

Published: 28 June 2022.

Edited by:

Julie Prescott, The University of Law, United KingdomReviewed by:

Anna Parola, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyFrancesca Giovanna Maria Gastaldi, University of Turin, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Boniel-Nissim and Alt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meyran Boniel-Nissim, bWV5cmFuYm5AZ21haWwuY29t

Meyran Boniel-Nissim

Meyran Boniel-Nissim Dorit Alt3,4

Dorit Alt3,4