- School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

The experiences of remote teachers who work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma is under explored. Children from remote areas of Australia are vulnerable to complex childhood trauma as their communities can face the effects of colonization, higher rates of disadvantage and exposure to potentially traumatic circumstances, such as natural disasters and family and community violence. This is compounded by the tyranny of distance in accessing effective supports. In such contexts, the roles of schools and teachers in addressing the debilitating impacts of trauma are both vital and amplified. This article summarizes a qualitative study, incorporating constructivist grounded theory, that generated a new theory to explain social processes that teachers in remote schools undergo when working with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Data were collected from teachers in individual interviews (n = 23) and a focus group. Data were analyzed using constant comparative method, emergent themes were categorized, leading to the development of the grounded theory, Building Trauma Informed Teachers. This overarching theory consists of seven categories. This study contributes insights into the scope and nature of the work of teachers in remote schools and recommends ways in which cognate systems can prepare and support teachers for their professional work supporting and educating trauma-impacted children.

Introduction

Although remote communities around the world are idiosyncratic due to their location, geography, norms, and cultures, they have one thing in common: all remote communities need teachers. This paper presents Building Trauma Informed Teachers as a new theory, built on teachers’ accounts of their experiences. It sheds light on what is needed to prepare and support teachers educating children in remote communities who live with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Complex childhood trauma is understood as arising from a child’s exposure to multiple, severe, and adverse interpersonal events and circumstances in the childhood years (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2014). These conditions are known to have a pervasive effect upon children’s development and educational and life outcomes (Cummings et al., 2017; Mehta et al., 2021; Downey and Crummy, 2022).

The research reported here was conducted in Australia. Children growing up in Australia’s remote communities are more socio-economically disadvantaged, and experience higher rates of trauma than their urban counterparts (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2019a,2020; Maguire-Jack et al., 2020). They have a higher frequency of exposure to natural disasters (cyclone, floods, drought, bushfires), greater exposure to domestic and family violence, and more involvement with child protection systems (Mitchell et al., 2013; Roufeil et al., 2014; Menec et al., 2015; Goodridge and Marciniuk, 2016; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2020). Children impacted by trauma who live in remote communities have the additional challenge of having limited access to support services and teachers may be the only professionals available to assist (Evans et al., 2008; Chafouleas et al., 2016).

These conditions are complex and dynamic, and intertwined with the effects of colonization, dispossession and assimilation which led to the destruction of traditional family units in Australia’s remote communities and has resulted in intergenerational trauma (Atkinson, 2002; Menzies, 2019; Curthoys, 2020; Meyer and Stambe, 2020). Intergenerational trauma has been defined as trauma that “occurs when parent figures who experienced trauma transmit the effects of their trauma to their children via interactional patterns, genetic pathways and/or family dynamics” (Isobel et al., 2021, p. 632). It is one of the many challenges faced by First Nation peoples in countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States (Brokenleg, 2012; Atkinson, 2013; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014; Kezleman et al., 2015; Isobel et al., 2021). First Nations peoples are disproportionally represented in populations living in remote communities. For example, in Australia, people identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander make up 3.3% of the Australian population overall yet comprise up to 47% of the populations in remote communities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW], 2019b).

Children impacted by trauma in remote communities may arrive at school with elevated stress levels and associated challenges with self-regulation and attention which are known to impede the capacity to learn (Howard, 2013; Mehta et al., 2021). They may not feel safe in classrooms (Sitler, 2009; O’Neill et al., 2010; Shalka, 2015) which can result in challenging behaviors that can impact the learning of other children (Porche et al., 2011; Howard, 2013; Ban and Oh, 2016; Brunzell et al., 2016). These behaviors can be frequently misunderstood by teachers if they are not well informed about the impact of trauma and effective responses (Goodman et al., 2012; Howard, 2013; Bonk, 2016).

There is a common rhetoric that “teachers are best placed to respond in a therapeutic manner” (Collier et al., 2020, p. 2) yet in distilling the limited extant literature on supporting teachers who work in a remote community with high numbers of children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma, three key findings suggest otherwise. First, due to a lack of support services, teachers in remote schools can be categorized as “first responders” (Ko et al., 2008, p. 399), akin to police and ambulance officers and other frontline workers (Ko et al., 2008). As with all first responders, the wellbeing of teachers can be compromised if they do not have the knowledge, skills, experience, and support to adequately execute their role. Second, teachers assigned to work in remote schools are often new graduates or have been teaching for no more than five years (Richards, 2012; Luke et al., 2013; Hazel and McCallum, 2016; Willis et al., 2017; Moffa and McHenry-Sorber, 2018; Weldon, 2018; Young et al., 2018). Many of these early career practitioners have grown up in cities and towns and studied in metropolitan universities, have predominantly white, middle-class backgrounds, and have had “little interaction with people of other ethnicities and social class” (Brasche and Harrington, 2012, p. 110). Third, these teachers report being “ill prepared” (Hall, 2013, p. 188) to effectively teach and respond to behavior of children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma (White and Reid, 2008; Richards, 2012; Hall, 2013; Heffernan et al., 2016). This can be exacerbated if they hold preconceived ideas and biases around their students and their families and communities (Hobbs et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2020).

Clearly teachers working in remote communities need preparation and support to effectively educate children living with the effects of complex trauma. Initial teacher education programs face a formidable task in doing this (Stahl et al., 2020) and teachers need ongoing support and training from their employing authorities. Criticism has been directed towards teacher education programs for failure to foster the type of practical skills needed to work in schools with children affected by trauma (Koenen et al., 2021). These factors make addressing trauma in remote communities “complex and multilayered” (Kreitzer et al., 2016, p. 50) and highlight why research with teachers working in remote communities is long overdue.

This paper reports on a doctoral study that was conducted in Australia with teachers working in remote communities. The aim of the study was to capture and theorize the ways in which teachers in remote primary schools experience their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma, with a view to informing university curriculum and education governance systems for initial teacher education and continuing professional development. The study used constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) which is commonly utilized to investigate the lived experiences of participants (Karpouza and Emvalotis, 2019; Aburn et al., 2021; Causer et al., 2021; Hood and Copeland, 2021; Williams et al., 2021).

Materials and Methods

This study used constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) to examine remote primary school teachers’ experiences with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Constructivist grounded theory is suitable for research on topics where there is limited existing research, and no theoretical framework available to guide data collection and analysis (Charmaz, 2014). A constructivist approach is based on the notion that a researcher constructs rather than discovers theories (Charmaz, 2014). It focuses on understanding peoples’ realties and how they construct these realities (Keane, 2015). Importantly, an outcome of constructivist grounded theory is that the theory developed “offers an interpretive portrayal of the studied world, not an exact picture of it” (Charmaz, 2006, p. 10).

Approval to conduct the research was granted from the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: 1800000177). Approval was also obtained from the relevant state education department for permission to approach schools for participation in this study. Participants provided specific written informed consent prior to data collection.

Participants

Participation was invited from teachers in remote primary schools. Exact participant numbers for a grounded theory study are debated (Morse, 2000; Marshall et al., 2013; Charmaz, 2014; Boddy, 2016). Although Charmaz (2014) suggests the appropriate number of participants depends on the purpose of the research and the “analytical level to which the research aspires” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 106), other proponents recommend 20–30 participants to ensure a well saturated theory (Morse, 2000; Creswell, 2013; Marshall et al., 2013).

In grounded theory research, “initial sampling” (Gentles and Vilches, 2017, p. 2) establishes the criteria for and plans how data will be collected from participants (Charmaz, 2014; Gentles and Vilches, 2017). In this study, the criteria for participation were straight forward: participants were to be primary school teachers employed in remote communities who self-identified that they were working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma.

Twenty-three participants agreed to participate in the study. The majority of participants were female (87%), aged under 40 years (60%), early career teachers (52%), in their first five years of teaching in a remote school (69%). Most had received professional development about complex childhood trauma (74%) and were developing confidence in implementing trauma informed practice (83%). Four participants identified as having either an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander background. Participants were employed in schools with enrolment numbers ranging from less than 30 to more than 400 students, of whom 19–89% were Indigenous (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2018). Participants worked in schools that had lower than average levels of student socio-economic advantage (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2015).

Procedure

Data were gathered in audio recorded 50–60 min, semi-structured interviews with each participant (Charmaz, 2014) by the first author. Prior to the commencement of formal data gathering, a pilot study was conducted with two primary school teachers who were not working in the schools participating in the research, but who had experienced working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Feedback from the pilot study informed the formulation and implementation of final interview questions, interview technique, and memo writing (Weiss, 1994; Silverman, 2010). Interviews spanned June to November 2018 and were conducted face-to-face. Participants were asked to respond to questions such as, “Describe some of your work with children at school who are living with the effects of complex childhood trauma” and “How does living and working in a school in a rural and remote area influence how you work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma?” During interviews, field notes were taken and after each interview researcher’s reflections were recorded. Reflections included thoughts from the interview, and interview technique, and these formed the basis of researcher memos. In keeping with constructivist grounded theory, after each interview, interviews were transcribed line-by-line and data were de-identified.

Data Analysis

In grounded theory research, data analysis is iterative, non-linear, and messy, and demands that the researcher is emersed in the data (Charmaz, 2014).

The first cycle of coding involved initial and in vivo coding. According to Charmaz (2014), initial line-by-line coding of interview transcripts enables the researcher to see the participants’ world view with some degree of objectivity (Saldaña, 2013; Charmaz, 2014). Initial coding allowed for the early categorization of data (Charmaz, 2014) and provided preliminary directions for constant comparison and the defining of meanings (Charmaz, 2011). During line-by-line coding, “gerunds” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 120), and in vivo codes were identified (Charmaz, 2014). Gerunds are expressed as the noun form of verbs ending in “ing” (e.g., “burning out” for “burnt out” (IP1)) and are used in constructivist grounded theory to represent “a strong sense of action” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 120) and make connections between the codes implicit (Charmaz, 2014). In vivo codes are used to capture important terms used by participants and highlighted the behaviors or processes explaining how the “basic problem of the actors is resolved or processed” (Strauss, 1987, p. 33) (e.g., “even in you have students that are super academically low, you still have those high expectations for them to be providing work as well” (FGP1)).

The second cycle of coding involved assigning focus codes and developing categories. Initial coding was followed by a second cycle of coding in which focused codes and categories were developed in a process of comparing “thematic or conceptual similarities” (Saldaña, 2013, p. 209). It involved long engagement with the data which enabled the researcher to develop in-depth knowledge of the data leading to the development of categories rather than merely labelling key topics that participants had discussed (Charmaz, 1983). After categories were identified, diagrams and memos were used to identify the properties, or defining characteristics, of each category (Charmaz, 2014). Several further evolutions ensued to gradually refine theoretical codes and bring these into sharper focus. For example, in the first evolution, analysis relied solely on the guiding questions from the interview schedule to determine initial categories. In the second evolution constant comparative analysis was used and categories were named using gerunds (Charmaz, 2014). In the third evolution categories expressed as gerunds were conceptualized as strategies teachers were explaining they had used which enabled further refinement. In the fourth evolution, further memoing, diagramming of relationships between categories and constant comparison of the data (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) resulted in the further refinement of categories.

Theoretical Sampling

Theoretical sampling is a grounded theory method for “checking out hunches and raising specific questions” (Charmaz, 1983, p. 125) about developing properties, categories, and theoretical codes (i.e., identifying and encapsulating the overall theory, grounded in the data). In this study, theoretical sampling was used to test the authenticity and credibility of tentative research findings, and to expand data collection if participants identified further details not already captured in individual interviews. This was undertaken in a 90-min focus group with seven of the original 23 interview participants who agreed to attend. Thereafter, several further analytical evolutions, with constant comparison to previous evolutions, resulted in clarity. In the final analysis, a new grounded theory was proposed, and seven categories were theorized, united by a central core category, building and maintaining relationships strongly suggesting that if teachers were unable to build and maintain relationships, they were unable to do their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma.

Grounded Theory Evaluation

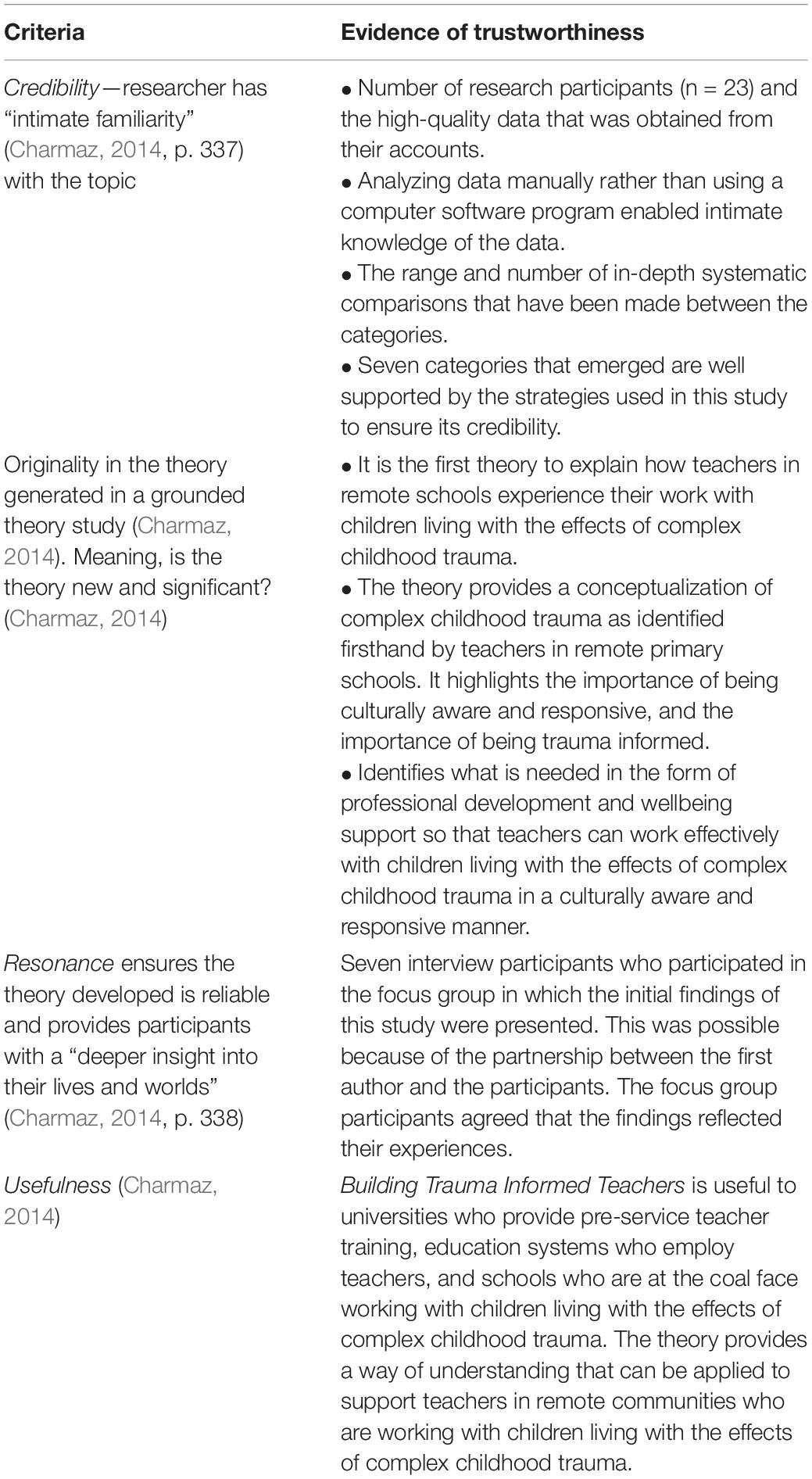

A hallmark of constructivist grounded theory is an additional data analysis method in which researchers self-assess the quality of their research against a set of established criteria pertaining to credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness (Charmaz, 2014). Although seldom presented in journal articles, in the interests of transparency and comprehensiveness, Table 1 shows an excerpt from this analysis focusing on evidence of trustworthiness against each criterion.

Findings

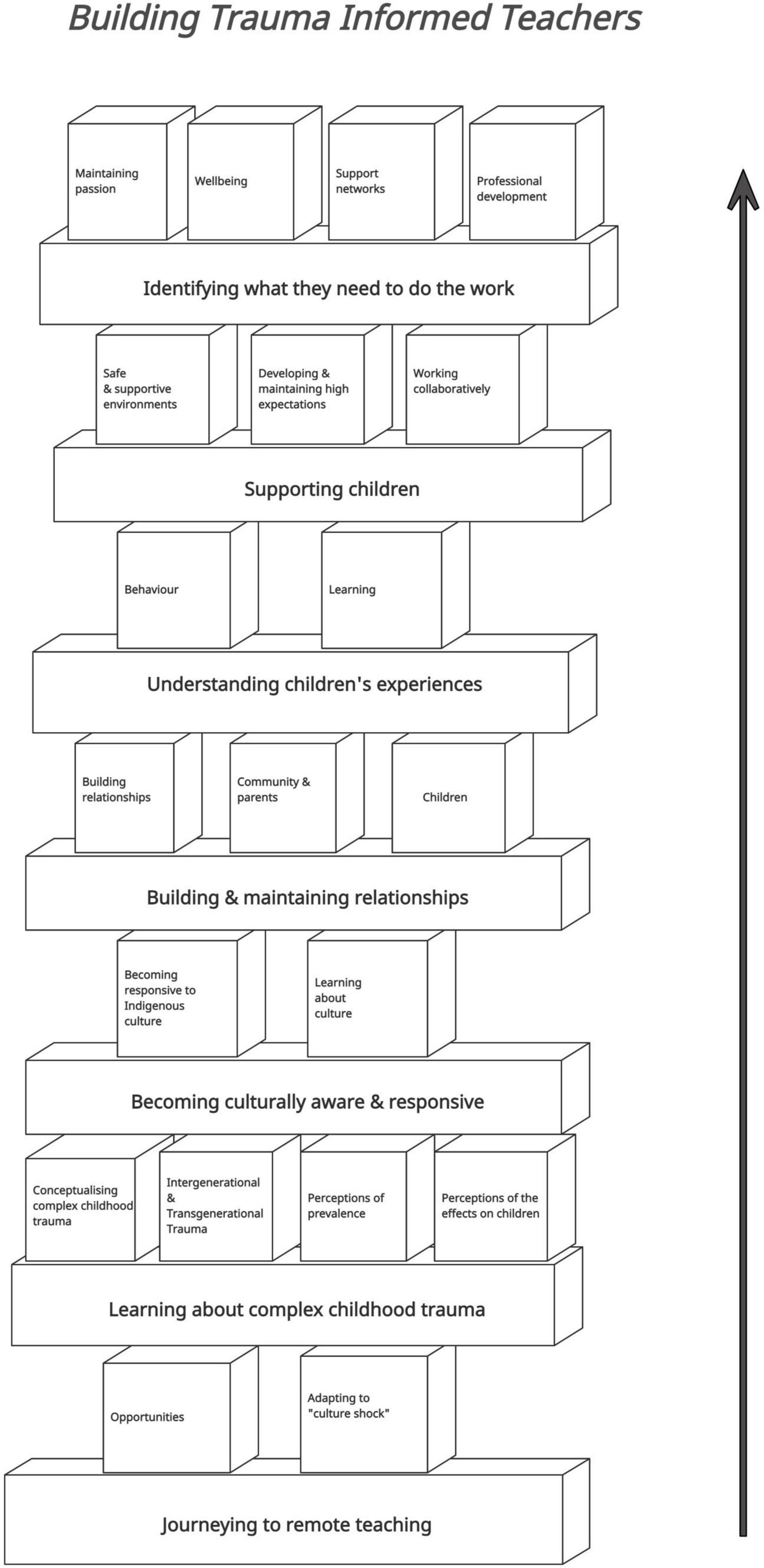

The findings reveal how remote primary school teachers experience their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. The theory—Building Trauma Informed Teachers consists of seven inter-related categories: (i) journeying to remote teaching, (ii) learning about complex childhood trauma, (iii) becoming culturally aware and responsive, (iv) building and maintaining relationships, (v) understanding children’s experiences, (vi) supporting children, and (vii) identifying what is needed to do the work.

Figure 1 depicts the structural interplay between the experiences inherent in the seven categories. This is shown through the metaphor of a “jenga tower.” Jenga is a Swahili word meaning “to build” (Muhammad, 1915, p. 393) and is the name of a game with blocks requiring problem solving skills (O’Brien, 2010).

The jenga tower visually depicts the theory developed in this study. The tower itself represents the overall theory. The horizontal blocks represent the categories within the theory. The composition of each horizontal block represents the properties of each category. Each aspect of the jenga tower is part of the overall experience. Each horizontal block and the composition of each horizontal block contributes to the overall stability or instability of the experience. The theory’s core category, building and maintaining relationships, is the central experience and is depicted in the very center of the tower.

The seven categories within the theory are interdependent and overlapping. The categories should not be considered as discrete even though these are presented below under category subheadings for the purpose of this article. The properties that make up each category highlight particular social processes that contribute to the central experience of building and maintaining relationships. The interaction of categories helps to explain the experience of teachers in remote primary schools working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. The first three categories, journeying to remote teaching, learning about complex childhood trauma, and becoming culturally aware and responsive are the initial social processes and are the cornerstones for teachers to be able to build and maintain relationships with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Once building and maintaining relationships have been established, teachers can do the important work needed to support children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. This can include work depicted in the categories, understanding children’s experiences, supporting children, and identifying what is needed to do the work. Without the central experience of building and maintaining relationships, these later categories would not be achieved. If any of the categories and their properties are removed, the system can become unstable and may collapse. In the context of this study, if one of the categories and their properties were to be removed it can have a significant impact on the teachers’ experiences. If the central experience of building and maintaining relationships is removed, the tower cannot stand. That is, the teachers will not be able to do their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma.

The following sections will explain the study’s findings by presenting, in turn, each category from the theory, Building Trauma Informed Teachers.

Category One: Journeying to Remote Teaching

The first category explores the process of journeying to remote teaching undertaken by participants. The category has two properties: teaching remotely offers professional and personal opportunities, and adapting to “culture shock.”

Participants mainly decided to journey to remote areas for professional and personal opportunities. Professional opportunities included securing their first teaching position, accessing a pathway to permanent employment, and fulfilling contractual requirements for certain periods of “country service” (White, 2019, p. 146). The challenge of remote teaching was initially attractive to them. Personal opportunities included joining partners who secured work in the community, or wanting to experience a change in life. Data analysis showed that, regardless of whether deciding to teach in a remote community was for professional or personal opportunities, once the decision to journey to remote teaching was made by participants, they were committed to “wanting to make a difference” (Interview participant (IP) 4, IP5, IP17, IP19).

When beginning their journey to remote teaching, participants described experiencing something akin to “culture shock” (IP21, Focus Group Participant (FGP)1, FGP4) in relation to environments, languages, and extreme weather events that were previously unknown to them. Participants described feeling “out of [their] comfort zone” (IP10). Once the culture shock subsided there was a period of adjustment. Despite having “fumbled through the first six months” (IP13), participants described their journey as rewarding and enjoyable expressing this with impassioned statements such as, “I fell in love with it [remote community], so never came back to the big city” (IP1).

Category Two: Learning About Complex Childhood Trauma

The theory’s second category explains the processes by which participants learnt about complex childhood trauma. This category has four properties. The first property, how teachers conceptualize complex childhood trauma, explained that it was difficult for participants to define complex childhood trauma, but they viewed it as widespread and complex. An interview participant explained this as “struggling with the demons that they [students] carry on their backs every single day” (IP7). Participants had observed that complex childhood trauma was mostly anchored in children’s experiences of domestic and family violence. The second property, understanding intergenerational and transgenerational trauma, identified participants’ awareness of the impact of historical and intergenerational harm as part of the milieu for children living in remote communities. The third property, teachers’ perceptions of prevalence of complex childhood trauma, explained participants’ perceptions that the rates of complex childhood trauma were higher in remote communities rather than in non-remote communities. The fourth property, teachers’ perceptions of the effects of complex childhood trauma on children, explained that participants viewed the impacts of complex childhood trauma as being lifelong and devastating for children.

Category Three: Becoming Culturally Aware and Responsive

The third category, becoming culturally aware and responsive explains how participants become more culturally aware and responsive to the children they are teaching. This category has two properties. The first property, becoming responsive to Indigenous culture, explains participants growing awareness of culture in their communities, “you get to see another culture and how a different culture operates and to be part of that is something very special and I would never get that in a bigger place” (IP4). The second property, learning about culture, highlighted that they recognized the importance of improving their cultural awareness and responsiveness. One participant stated that, “you need to have awareness of culture and the effects of what has happened in the past” (FGP1). Another important understanding held by all the focus group participants was that not all children in remote communities who live with complex childhood trauma are from Indigenous backgrounds.

Category Four: Building and Maintaining Relationships (Core Category)

The fourth category, building and maintaining relationships depicts the theory’s central experience and core category. This category has three properties. The first property, building relationships, emphasizes participants’ broad general understanding of the importance of networks of relationships needed to successfully work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. This knowledge existed in tension with their realization that the work of relationship building was extremely challenging and could not be rushed.

The second property, building relationships with community and parents was deemed by participants to be extremely important if they were to successfully work with children impacted by trauma. They emphasized the importance of trust in relationships and belonging: the need to feel a part of the broader school and local community. One participant offered, “if you’re not willing to form relationships, you will find it very hard. You do need to know the families. You can’t be the kind of teacher that says, ‘ok bell’s gone, see you later.’ That doesn’t work out here” (IP11). Another participant explained that once trusting relationships were established, “those parents are a little bit more forthcoming of what’s going on in their lives…. and they’re willing to talk about it” (IP5). Participants shared their realization that relationships with parents might be built over a long time in which their acceptance into the community was tested as encapsulated in this comment, “I noticed after being here a few years, the relationships changed. So, the parents were like, ‘you’re not here to do your time and leave. You’re here because you care and want to be here now.’ I did see that significant change” (IP5).

The third property, building relationships with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma, focuses on the importance of teachers getting to know the children, building attachments with children, and providing safety for children. Getting to know children required work on their part. They explained that getting to know children took significant time as it could be difficult for trauma-impacted children to trust in relationships. Getting to know children required teachers to understand children’s realities, then step up and accept responsibility as advocates for children. Participants took their responsibilities in this area very seriously with common comments like, “you’re the main person that they see every single day” (IP15). Teachers new to ‘teaching remote’ needed to become aware of this as confirmed in the focus group, “I think it’s a big wake up call, especially for young teachers when they come to town because it’s like all of a sudden, you’re a serious figure in the kid’s life, being that advocate for the child. All of a sudden you have gone from uni (sic) and you’ve all of this responsibility. Or you’ve come from a different area where you could leave work at the door whereas here, you can’t” (FGP1). Participants were also able to explain building relationships with children living with the effects of complex trauma as transformative, with comments such as, “I feel like it has changed me [for the better]!” (IP11).

Category Five: Understanding Children’s Experiences

The fifth category, understanding children’s experiences, explores the teachers’ understandings of the experiences of children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. This category has two properties. The first property, effects of complex childhood trauma on behavior, draws from participants’ explanations of the different types of behavior exhibited by children impacted by trauma and their understanding of the reasons for these behaviors. Participants described the children as displaying predominantly ‘externalizing behaviors,’ that is, behaviors that could easily be seen and/or heard and that caused disruption at school. Examples given included physical violence towards others, emotional outbursts, throwing objects, running/walking away, swearing, inappropriate touching, and yelling. They understood these behaviors as signs of something deeper for example, “how I see this behavior with most of these kids is a cry for help. It means something is not right in their mind, or in their body or how they’re feeling in a situation, so they do these negative things as a cry for help” (IP6). They described these kinds of behaviors as draining on teachers’ time with comments such as, “the staff at school to work with these kids…I suppose it takes them away from the work they are doing” (IP2). ‘Internalizing behaviors’ were perceived to be less common amongst the children with examples restricted to being withdrawn or quiet. As one participant said, “every child experiences trauma in different ways” (IP9).

The second property in this category, effects of complex childhood trauma on learning, captures teachers’ understanding of “how students’ experiences can impact them, educationally” (IP20), and the impossibility of reading educational benchmarks with statements such as, “how can I make this child [living with the effects of complex childhood trauma] engage with learning…. you just can’t. It’s about managing their behavior before you can even think about doing the learning” (IP16). Participants were very vocal about having to respond to questions from their school leadership teams about why children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma were not achieving national benchmarks in literacy and numeracy. They explained, “I feel like our admin leadership team are focused on the data and the curriculum and not understanding…not realizing that we may need to adapt things for children to be more successful” (IP11) and a focus group participant expanded, “unfortunately, they’re not going to sit down and do a standardized test that has questions [that they do not understand]” (FGP1). Strategies employed by participants to address this included: “for the first term, the curriculum sort of took the back burner” (IP23) so as to build trusting relationships and belonging. Encapsulating the interconnected nature of the theory’s categories, a participant elaborated, “I have always said that if you don’t have a positive relationship with the student, then they’re not going to learn. If they are not going to learn, they are not going to be successful. You are not going to be successful and it’s a ripple in a pond, isn’t it? So, I think it has taught me the importance of relationships with students. It has taught me the importance of knowing students as individuals not just as a class of students” (IP11).

Category Six: Supporting Children

The sixth category, supporting children represents the notion that it is very important to support children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. This category has three properties. First, providing safe and supportive environments, which was identified by participants as an essential part of supporting children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Safety was identified by participants as an important precursor to learning, “when they feel safe, the learning and everything else comes” (FGP1). Another focus group participant went as far as to suggest that when safety is established, “that’s when you get to actually be a teacher rather than a counselor or a parent” (FGP4). Strategies for achieving this level of support were detailed beginning with, “you need to be super consistent. To have clear boundaries, guidelines, expectations, consistency. Because that also plays into safety, of students feeling safe by that consistency and the predictability” (FGP1).

Second, developing and maintaining high expectations, was the key mechanism by which participants worked through curriculum demands of teaching students living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. An interview participant raised this, “I find expectations are huge. If you have really minimal expectations of the kids, that’s what they will achieve, but if you tell them, you expect more, and I know that you can do this. Then, I find that they do. They will try their hardest to get there” (IP11). Holding and managing high expectations of children was seen as a way to convey confidence in children’s capacities, “having those high expectations shows that you believe in those kids [living with the effects of complex childhood trauma] before they can believe in themselves” (FGP7). One focus group participant described the interaction between safety and expectation thus, “…. that [complex childhood trauma] gets left at the door…now you’re in safe space and you’re ok, this is what I expect” (FGP1).

Third, working collaboratively with others was necessary and essential to supporting children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. They collaborated with school guidance officers (i.e., school counselors), deputy principals, principals, and teaching colleagues, and highlighted the importance of “working as a team” (IP16) to support children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma including development of support plans.

Through the social processes of understanding children’s experiences (category 5) and supporting children (category 6) participants were then able to identify what they need to do the work.

Category Seven: Identifying What They Need to Do the Work

The seventh and final category is identifying what they need to do the work. The category has four properties. First, maintaining passion was needed to do the work, “you need to have passion, like you need to be determined and passionate enough to get involved with the kids” (FGP4). This was a spark that enabled them to grow as a teacher, “[this passion] pushed me to be a better teacher” (IP11). Second, looking after wellbeing was important because participants’ wellbeing had suffered in various ways at some stage while doing the work, “I’m wearing a mask of, I can handle this. I can take care of this” (IP7). Participants expressed feelings of self-doubt about the quality of their teaching, “one of my biggest concerns was feeling like I wasn’t being a good teacher for the other kids in the class” (IP13). Third, support networks were important for teachers being able to do the work and maintain their wellbeing. Participants described lack of formal support systems, and being away from their own family support networks. Teachers often banded together to work through their experiences of work. A focus group participant explained, “relationships you make with other teachers. There’s a closeness. I feel like at our school, it’s a family. So, I can go to any of the staff and say, ‘this is going on’ or ask for advice and it’s a safe place” (FGP1). In remote areas, “friendships made and how they become family” (FGP3). Fourth, accessing professional development as a source of support brings us full circle back to the study’s first category of “journeying.” Professional development as described by an interview participant as, “I’m on a journey and I’m learning too” (IP4). On this journey, participants traveled through multiple learning experiences working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. They became more confident in their skills, “I’m more confident than what I was before…but still learning” (IP12). On the job experiential learning may not always be supported with, “PDs [professional development] that will actually support you to work with kids that you are working with” (FGP2). They said this professional development needed to be ongoing and provide specific strategies for working with complex childhood trauma, school curriculum, working with parents, and cultural awareness.

Discussion

This grounded theory study offers a theory to understand how teachers in remote primary schools experience their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. It is a process of building and maintaining relationships. It provides valuable insights into how teachers “do the work” (Venet, 2019, p. 4), the challenges they faced, and the opportunities generated. This study is one of the first to report on teachers’ experiences of working in remote schools with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. It builds on previous work of Brunzell et al. (2018), Howard (2019), Stokes and Brunzell (2019), Berger et al. (2020) and Berger and Samuel (2020) but is the first to develop a theory that can be used by universities and education systems as a tentative conceptual foundation for preparing teachers to work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma.

The discussion focuses on key findings from each category, anchoring each of the categories back to the theory’s central category to emphasize the interconnected nature of teachers’ experiences and highlighting the centrality of building and maintaining relationships particularly in remote communities when working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. It will also discuss the implications of the findings and addresses the study’s strengths and weaknesses.

Journeying to Remote Teaching

“Culture shock” was experienced by participants once they started working in a remote community. This “culture shock” was due to their new environment—a remote community—being completely different from what they had previously experienced. Although “culture shock” is a somewhat generic term, placed in context of Australia’s remote areas which are “not demographically homogenous” (Willis and Grainger, 2020, p. 32), “culture shock” may be very subtly nuanced for teachers in each unique community. Previous research finds that these nuances can be challenging for teachers in remote communities (Sharplin, 2002; Datta-Roy and Lavery, 2017; Kelly et al., 2019; Lowe et al., 2019; Willis and Grainger, 2020). Differences in environmental and social factors lead teachers to experience new and unexpected situations which then have implications for how they build relationships within communities. Yet “culture shock” can be mediated when existing relationships, especially those established by school leaders, are strong and reliable (Chen and Phillips, 2018; DeFeo and Tran, 2019).

Universities and education systems can take heed with this finding because it points to ways in which appropriate and effective preparation, induction, and ongoing mentoring and support for new teachers builds upon existing relationships (somewhat like the adage of standing on the shoulders of giants). These insights could assist with systemic relationship building in communities and thus enable more effective transition to teaching in remote schools.

Learning About Complex Childhood Trauma

Within the context of this study, it was important to document how remote teachers conceptualized complex childhood trauma because the literature strongly suggests that implementation of trauma informed practices must be contextualized (Bessarab and Crawford, 2010; Pihama et al., 2017; Menzies and Grace, 2020). Although the participants in this study did not have a shared definition of complex childhood trauma, they did share understandings about its genesis. For example, importantly for contextualization, they conceptualized complex childhood trauma through the lens of intergenerational trauma and transgenerational trauma (Atkinson, 2013; Menzies, 2019; Sianko et al., 2019; Noble-Carr et al., 2020). They recognized the inter-relationships between domestic and family violence, and intergenerational and transgenerational trauma (Atkinson, 2013; Langton et al., 2020; Fiolet et al., 2021). The intertwining of these complex phenomena arises from the long-term effects of colonization, government policies on assimilation which led to the destruction of traditional family units in many Australia’s remote communities, resulting in dispossession and despair (Atkinson, 2002; Menzies, 2019; Curthoys, 2020; Meyer and Stambe, 2020). Teachers in this study bore witness to these injustices and the harm they have caused and continue to cause. It is no wonder they were confronted by suspicion and mistrust as impediments to relationship building (Fernando and Bennett, 2019). If teachers understand the “historical and structural oppression in the context of historical and intergenerational trauma” (Blitz et al., 2016, p. 119) this provides them with clues as to how they can build relationships with the communities, families, and children they work with. It is important, therefore, that universities and education systems provide education and training on the topic of complex childhood trauma including its definition, cause, and effects. We join with others in calling upon these institutions to play a stronger role in raising awareness and building professional capacity to understand and respond to complex childhood trauma with effective practices (Berger, 2019; Brunzell et al., 2019; Howard, 2019; Berger and Samuel, 2020). This would ideally begin in pre-service education and continue with ongoing professional development via in-service education (Howard, 2019).

Becoming Culturally Aware and Responsive

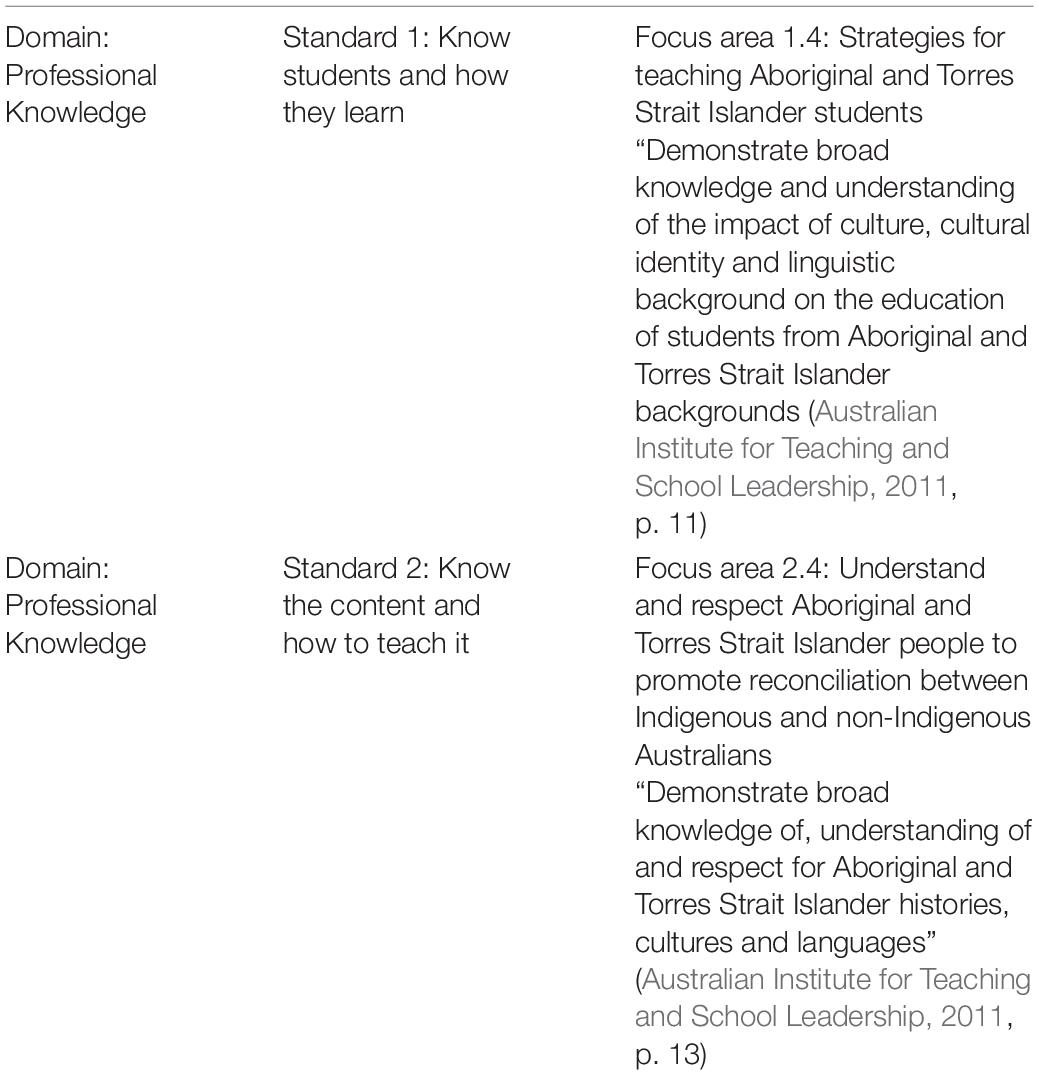

Being responsive to Indigenous cultures and learning about the local culture was an important component of building and maintaining relationships with communities (Miller and Berger, 2021; Miller and Steele, 2021; Shay et al., 2021). Participants recognized the need to be aware of cultural protocols and were conscious of their own needs for training in this area. However, none appear to have been exposed to cultural awareness training prior to or during their service in remote schools. There is limited research investigating the extent to which teachers in remote communities receive cultural awareness training and its effectiveness (Gower et al., 2020). This is despite government commitment to The Alice Springs (Mwparntwe) (Australian Government, 2019), and calls from the Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership (Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2020) for teachers to receive cultural awareness training, and the championing of Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (2011) which have focus areas where teachers need to receive cultural awareness training if they are to enact these standards as outlined in Table 2.

These findings highlight the necessity and urgency for universities, education systems, and school communities to provide cultural awareness training so that teachers can embed Indigenous perspectives in their pedagogy and school processes. This will also support building and maintaining relationships with local community members.

Building and Maintaining Relationships

Building and maintaining relationships was the central experience of participants in being able to do their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. The teachers in this study concluded that building and maintaining relationships was the very foundation for their work aligning with previous studies which also found the importance of teacher student relationships with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma (Townsend et al., 2020; Wall, 2020; Miller and Berger, 2021). Participants emphasized the importance of building and maintaining relationships within the communities in which they worked. The centrality of this experience is evidenced in the numerous studies identifying the importance of community and parental relationships, noting that these take time to build because trust is evasive, and this is partly attributable to parents’ previous experiences of abuse, violence, and trauma at school (Morton and Berardi, 2018; Miller and Berger, 2021). For teachers, overcoming this legacy of trauma at school adds additional layers to the complexity and importance of building and maintaining relationships. It demands high levels of resilience even for teachers who are early in their careers (Crosswell et al., 2018; Papatraianou et al., 2018), yet in communities in which relationships were able to be built, participants reported their work with children forged ahead. Key to this appeared to be respect and compassion; not finding blame for children’s circumstances or casting judgements but working from a position of strength and agency (Borrero et al., 2018; Sarra et al., 2018; Hajovsky et al., 2020; Miller and Berger, 2021). In this way, the findings of this study contrast with those of a case study of an Australian teacher which uncovered the high prevalence of deficit discourses and blame apportioning (Stacey, 2019). These findings emphasize the importance of education systems and school communities having strong organizational leadership, governance, and cultures to create inclusive, welcoming, and positive environments in which relationships can thrive.

Understanding Children’s Experiences

This study found that participants observed and understood that complex childhood trauma impacted upon children’s behavior and learning, congruent with previous research (Davis et al., 2018; Berger, 2019; Berger and Samuel, 2020; Collier et al., 2020; Wall, 2020). In this study, participants’ accounts of their experiences touched on how they understood complex childhood trauma as manifesting in both externalizing and internalizing behaviors (Doll, 2019; Splett et al., 2019; Olivier et al., 2020; Miller and Berger, 2021), and they identified that lower academic achievement required differentiation in teaching (Deunk et al., 2018; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019; Miller and Berger, 2021). They implemented differentiation as a key strategy to address learning difficulties, with limited support and resources. Participants in this study hinted at a cascading of effects when discussing children’s academic progress. They explained tensions between school curriculum standards and expectations and children’s individual circumstances, needs, and capabilities. They found it difficult to balance the needs of children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma against needs of other children in their classes, circumstances that have now been documented by other researchers (Berger et al., 2020; Parker and Hodgson, 2020). Teachers in this study seemed to also struggle solo with children’s learning difficulties (Ryan et al., 2018), whereas research points to the value of a whole school approach to trauma informed practices (Davis et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2018; Berger and Samuel, 2020). Fortunately for school systems and early childhood systems in Australia, guidelines of trauma-aware education have been developed, disseminated (Queensland University of Technology [QUT], and Australian Childhood Foundation, 2021) and their uptake and use can be studied in future research.

Supporting Children

Developing and maintaining high expectations was found in this study to be the bedrock for supporting children: being supportive yet challenging in a supportive manner. The participants seemed to firmly believe that despite their experiences, children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma were able to learn and achieve. Previous research has identified the importance of high expectations of children generally (Roffey, 2016; Burgess, 2019; Sarra and Shay, 2019; Sarmardin et al., 2020; Townsend et al., 2020; Shay et al., 2021). Within the context of Indigenous education in Australia specifically, Sarra et al. (2018) coined the phrase “high expectations relationships” (Sarra et al., 2018, p. 32) to describe the kinds of strong teacher student relationships built on awareness that personal beliefs and assumptions can impact on others. Breaking this down, the components of high expectations are: understanding trauma, utilizing trauma informed practices, and building relationships with families and communities (Department of Education [DoE], 2020). All were identified by participants in this study. Participants in this study identified an additional component to enabling high expectations, that of working collaboratively with others including teacher colleagues, school mental health professionals, and community agencies. Working collaboratively is often taken for granted in workplaces such as schools yet it has been identified within the literature as important work (Mellin et al., 2017; Biddle et al., 2018; Berger and Samuel, 2020; Collier et al., 2020). School mental health professionals are often viewed as “experts on trauma informed practice” (Howell et al., 2019, p. 31), and they are known to be a source of positive emotional support, providing insights into students, and finding solutions with teachers, who then put them in place (Tatar, 2009; Alisic, 2012; Kourkoutas and Giovazolias, 2015; Reinbergs and Fefer, 2018). However, there is some research to suggest that school mental health professionals may not feel fully equipped in their knowledge, confidence, and skills in relation to complex childhood trauma, specifically in understanding how it impacts on children’s learning and behavior (Gubi et al., 2018; Collier et al., 2020). This has a flow-on effect to the support teachers receive, particularly in areas where there are limited services available, and the school mental health professional is the main avenue for support for both teachers and children. There has been some research finding that interventions implemented by teachers are as effective as those delivered by mental health professionals (Stratford et al., 2020). With the limited access to mental health professionals in remote communities, this highlights for universities and education systems the importance of appropriate preparation and ongoing training and support for all school personnel working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma.

Identifying What They Need to Do the Work

This study found that even though teachers faced challenges, they find their work in remote communities with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma to be rewarding. This is in line with other research that has found that positive relationships with students enhance teachers’ wellbeing, as these relationships enable teachers to see concrete evidence that they are making a difference (Kangas-Dick and O’Shaughnessy, 2020; Miller and Berger, 2021). However, there is limited research on how working conditions in remote schools’ impact on the wellbeing of teachers (Willis and Grainger, 2020). Some extant research suggests inadequate support for teachers and administration staff in remote schools makes them vulnerable to the effects of secondary trauma, also referred to as secondary traumatic stress (Lawson et al., 2019; Collier et al., 2020) or type II trauma (Sage et al., 2018) which refers to a person’s indirect exposure to traumatic events and “subsequently identifying and empathizing with the victim” (Sage et al., 2018, p. 457). People who work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma (e.g., child protection staff, child therapists, and mental health workers) who had high levels of job satisfaction had lower levels of compassion fatigue (Sage et al., 2018). For teachers in this study, like professionals in previous studies, secondary traumatic stress manifested as disengagement and withdrawal from work, with knock-on effects to their personal life such as sleep problems (Blitz et al., 2016; Lawson et al., 2019). Remote teachers are at risk of developing these conditions if not properly trained and supported.

Teachers in this study disclosed that they did not feel prepared to work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. They are not isolated cases in not receiving formal training in trauma informed practices (Miller and Berger, 2021). Findings of this study highlight the need for ongoing professional development in trauma informed practices and on the ground support from knowledgeable others. This is consistent with previous research (Berger and Samuel, 2020; Berger et al., 2020; Blitz et al., 2020; Reierson and Becker, 2020; Willis and Grainger, 2020; Miller and Berger, 2021). Training has been linked to increased confidence in working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma (Berger et al., 2020; Loomis and Felt, 2020; Sonsteng-Person and Loomis, 2021).

Strengths and Limitations

This study offers an original theory which provides insights into how teachers in remote primary schools experience their work with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. It reveals the centrality of relationships. In doing so, this study is significant in five main ways. First, it extends and enriches understanding about the importance of building and maintaining relationships with communities, parents, and children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. Second, it provides understanding of how teachers conceptualize complex childhood trauma to be intergenerational and transgenerational trauma, and the significance of domestic and family violence as intertwined with this. This conceptualization of complex childhood trauma enables teachers to better understand the children in their classrooms and communities and respond sensitively. Third, this study highlights the importance of teachers in remote communities becoming culturally aware and responsive through contextually appropriate cultural awareness training beginning in pre-service teacher education and extending through the teaching life course. Fourth, this study contributes to understanding teacher wellbeing in remote teaching appointments. Finally, this study finds the importance of initial teacher training and ongoing professional development, without which teachers will burnout and this may lead to negativity and sub-optimal practice in their work in remote schools with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma.

There were some limitations in this study that should be discussed. One limitation was the lack of diversity of the participant sample. Recruitment was conducted via email messages to all rural and remote primary schools in the research area (n = 57). Participants who volunteered to be interviewed were from a smaller number of schools. Three quarters of the participants previously accessed some form of training regarding trauma informed practices which may have biased the results. Data were not collected on the scope and nature of the professional development (e.g., topics covered, presenter qualifications, duration) so it is not possible to know the extent to which access to professional development impacted on the findings of this study. Given a different recruitment mechanism or longer response times, there may have been other teachers who may have chosen to participate in the study. A purposeful sample with the inclusion of rural and remote teachers across the research area may have diversified the sample and resulted in different findings. Another limitation to this study comes with the benefit of hindsight. These findings of the study may have been different if the phenomena under investigation was more narrowly or widely defined to include primary school teachers from a greater or lesser range of schools or teachers from secondary schools.

Conclusion

This study provides a new theoretical framework Building Trauma Informed Teachers which highlights the importance of building and maintaining relationships when working with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma. In sum, the findings of this study also suggest that if teachers do not have access to ongoing professional development in trauma informed practices and cultural awareness, alongside strategies for managing curriculum and learning demands (Stacey, 2019), it will remain difficult for teachers in remote communities to navigate the complex landscapes they find themselves in and could grow tendencies towards blame, deficit discourses, stress, and burnout (Coetzee et al., 2017; Kim, 2019). It would also be difficult for teachers to continue to manage and support the behavior and learning needs of children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma (Loomis and Felt, 2020). It is important to acknowledge that teachers enter teaching with their own past histories and experiences, and this influences how they teach and interact with students (Loomis and Felt, 2020). Universities and education systems can empower teachers at all stages of their teaching life course from pre-service to experienced with ongoing training and support so they can work effectively with children living with the effects of complex childhood trauma by using Building Trauma Informed Teachers.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because ethical approval for this study and institutional approval to conduct the research does not extend to the use of the original/raw data in future studies. Hence data are not available in a public access data repository. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: 1800000177). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MB conceived and designed the study, collected the data, performed data analysis, interpreted data for the article, wrote the manuscript, and co-ordinated authors in responding to successive drafts. JH served as associate supervisor for MB’s doctoral study, conceived and designed the study, supervised data analysis, interpreted data for the article, and wrote the manuscript. KW served as principal supervisor for MB’s doctoral study, conceived and designed the study, supervised data analysis, interpreted data for the article, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was conducted in fulfilment of a Doctor of Philosophy study for the first author. The Australian Commonwealth Government provides annual block grants to universities to support both domestic and overseas students undertaking higher degrees by research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely acknowledge and thank the teachers who participated in this study.

References

Aburn, G. E., Hoare, K., and Gott, M. (2021). “We are all a family”. Staff experiences of working in children’s blood and cancer centers in New Zealand – A constructivist grounded theory. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 38, 295–306. doi: 10.1177/10434542211011042

Alisic, E. (2012). Teachers’ perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: a qualitative study. Sch. Psychol. Q. 27, 51–59. doi: 10.1037/a0028590

Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma Trails, Recreating Songlines. The Transgenerational Effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia. North Geelong, VIC: Spinifex.

Atkinson, J. (2013). Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children. Resource Sheet No. 21. Closing The Gap Clearinghouse. Darlinghurst, NSW: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA] (2015). What Does the ICSEA Value Mean?. Minato City: ACARA.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA] (2018). My School. Minato City: ACARA.

Australian Government (2019). The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. Education Council. Canberra: Australian Government.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (2011). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Melbourne, VIC: AITSL.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2019a). Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence. New York, NY: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2019b). Profile of Indigenous Australians. New York, NY: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] (2020). Child Protection Australia 2018-10. Child Welfare Series no. 72. Cat. No. CWS74. New York, NY: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL] (2020). Indigenous Cultural Competency in the Australian Teaching Workforce. Melbourne, VIC.

Ban, J., and Oh, I. (2016). Mediating effects of teacher and peer relationships between parental abuse/neglect and emotional/behavioural problems. Child Abuse Neglect. 61, 35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.010

Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: a systematic review. Sch. Ment. Health 11, 650–664. doi: 10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0

Berger, E., Bearsley, A., and Lever, M. (2020). Qualitative evaluation of teacher trauma knowledge and response in schools. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 30, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2020.1806976

Berger, E., and Samuel, S. (2020). A qualitative analysis of the experiences, training, and support needs of school mental health workers regarding student trauma. Aust. Psychol. 55, 498–507. doi: 10.1111/ap.12452

Bessarab, D., and Crawford, F. (2010). Aboriginal practitioners speak out: contextualising child protection interventions. Aust. Soc. Work 63, 179–193. doi: 10.1080/03124071003717663

Biddle, C., Mette, I., and Mercado, A. (2018). Partnering with schools for community development: power imbalances in rural community collaboratives addressing childhood adversity. Commun. Dev. 49, 191–210. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2018.1429001

Blitz, L. V., Anderson, E. M., and Saastamoinen, M. (2016). Assessing perceptions of culture and trauma in an elementary school: informing a model for culturally responsive trauma-informed schools. Urban Rev. 48, 520–542. doi: 10.1007/s11256-016-0366-9

Blitz, L. V., Yull, D., and Clauhs, M. (2020). Bringing sanctuary to school: assessing school climate as a foundation of culturally responsive trauma-informed approaches for urban schools. Urban Educ. 55, 95–124. doi: 10.1177/0042085916651323

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. 19, 426–432. doi: 10.1108/qmr-06-2016-0053

Bonk, I. T. (2016). Professional Development for Elementary Educators: Creating a Trauma Informed Classroom Doctoral dissertation. Virginia Beach, VA: Regent University.

Borrero, N., Ziauddin, A., and Ahn, A. (2018). Teaching for change: new teachers’ experiences with and visions for culturally relevant pedagogy. Crit. Questions Educ. 9, 22–39.

Brasche, I., and Harrington, I. (2012). Promoting teacher quality and continuity: tackling the disadvantages of remote Indigenous schools in the Northern Territory. Aust. J. Educ. 56, 110–125. doi: 10.1177/000494411205600202

Brokenleg, M. (2012). Transforming cultural trauma into resilience. Reclaiming Child. Youth 21, 9–13. doi: 10.1300/j010v39n03_04

Brown, E. C., Freedle, A., Hurless, N. L., Miller, R. D., Martin, C., and Paul, Z. A. (2020). Preparing teacher candidates for trauma-informed practices. Urban Educ. 57, 662–685. doi: 10.1177/0042085920974084

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed flexible learning: classrooms that strengthen regulatory abilities. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 7, 218–239. doi: 10.18357/ijcyfs72201615719

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2018). Why do you work with struggling students? Teacher perceptions of meaningful work in trauma-impacted classrooms. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 116–142.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2019). Shifting teacher practice in trauma affected classrooms: practice pedagogy strategies within a trauma-informed positive education model. Sch. Ment. Health 11, 600–614. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8

Burgess, C. (2019). Beyond cultural competence: transforming teacher professional learning through Aboriginal community-controlled cultural immersion. Crit. Stud. Educ. 60, 477–495. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2017.1306576

Causer, H., Bradley, E., Muse, K., and Smith, J. (2021). Bearing witness: a grounded theory of the experience of staff of two United Kingdom higher education institutions following a student death by suicide. PLoS One 16:e0251369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251369

Chafouleas, S., Johnson, A., Overstreet, S., and Santos, N. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Charmaz, K. (1983). “The grounded theory method: an explication and interpretation,” in Contemporary Field Research: A Collection of Readings, ed. R. Emmerson (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press), 109–126.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practice Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Charmaz, K. (2011). “Grounded theory methods a social justice research,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th Edn, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications), 359–380.

Chen, A., and Phillips, B. (2018). Exploring teacher factors that influence teacher-child relationships in Head Start: a grounded theory. Qual. Rep. 23, 80–97.

Coetzee, S., Ebersöhn, L., Ferreira, R., and Moen, M. (2017). Disquiet voices foretelling hope: rural teachers’ resilience experiences of past and present chronic adversity. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 52, 201–216. doi: 10.1177/0021909615570955

Collier, S., Bryce, I., Trimmer, K., and Krishnamoorthy, G. (2020). Evaluating framework for practice in mainstream primary school classrooms catering for children with developmental trauma: an analysis of the literature. Child. Aust. 45, 258–265. doi: 10.1017/cha.2020.53

Creswell, J. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Crosswell, L., Willis, J., Morrison, C., Gibson, A., and Ryan, M. (2018). “Early career teachers in rural schools: plotlines of resilience,” in Resilience in Education, eds M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, and C. F. Mansfield (Berlin: Springer), 131–146.

Cummings, K. P., Addante, S., Swindell, J., and Meadan, H. (2017). Creating supportive environments for children who had exposure to traumatic events. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 2728–2741. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0774-9

Curthoys, A. (2020). Family violence and colonisation. Aust. Histor. Stud. 51, 146–164. doi: 10.1080/1031461X.2020.1733033

Datta-Roy, S., and Lavery, S. (2017). Experiences of overseas trained teachers seeking public school positions in Western Australia and South Australia. Issues Educ. Res. 27, 720–735.

Davis, J., Ratliff, C., Parker, C., Davis, K., and Hysten-Williams, S. (2018). The impact of trauma on learning and academic success: implications for the role of educators in urban academic settings. Natl. J. Urban Educ. Pract. 11, 85–95.

DeFeo, D. J., and Tran, T. C. (2019). Recruiting, hiring, and training Alaska’s rural teachers: how superintendents practice place-conscious leadership. J. Res. Rural Educ. 35, 1–17. doi: 10.26209/jrre3502

Department of Education [DoE] (2020). Every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Student Succeeding Strategy. Washington, DC: DoE.

Deunk, M. I., Smale-Jacobse, A. E., DeBoer, H., Doolard, S., and Bosker, R. J. (2018). Effective differentiation practices: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the cognitive effects of differentiation practices in primary education. Educ. Res. Rev. 24, 31–54. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.002

Doll, B. (2019). Addressing student internalizing behavior through multi-tiered system of support. Sch. Ment. Health 11, 290–293. doi: 10.1007/s12310-019-09315-3

Downey, C., and Crummy, A. (2022). The impact of childhood trauma on children’s wellbeing and adult behavior. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 6:100237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100237

Evans, G. D., Radunovich, H. L., Cornette, M. M., Wiens, B. A., and Roy, A. (2008). Implementation and utilisation characteristics of a rural, school-linked mental health program. J. Child Fam. Stud. 17, 84–97. doi: 10.1007/s10826-007-9148-z

Fernando, T., and Bennett, B. (2019). Creating a culturally safe space when teaching Aboriginal content in social work: a scoping review. Aust. Soc. Work 72, 47–61. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2018.1518467

Fiolet, R., Tarzia, L., Hameed, M., and Hegarty, K. (2021). Indigenous peoples’ helping-seeking behaviors for family violence: a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse 22, 370–380. doi: 10.1177/1524838019852638

Gentles, S. J., and Vilches, S. L. (2017). Calling for a shared understanding of sampling terminology in qualitative research: proposed clarifications derived from critical analysis of a methods overview by McCrae and Pursell. Int. J. Qual. Methods 16, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/1609406917725678

Glaser, B., and Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Transaction. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Goodman, R. D., Miller, M. D., and West-Olatunji, C. A. (2012). Traumatic stress, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement among primary school students. Psychol. Trauma 4, 252–259. doi: 10.1037/a0024912

Goodridge, D., and Marciniuk, D. (2016). Rural and remote care: overcoming the challenges of distances. Chron. Respir. Disease 13, 192–203. doi: 10.1177/1479972316633414

Gower, G., Ferguson, C., and Forrest, S. (2020). Building effective school-community partnerships in Aboriginal school settings. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 50, 359–367. doi: 10.1017/jie.2020.11

Gubi, A. A., Strait, J., Wycoff, K., Vega, V., Brauser, B., and Osman, Y. (2018). Trauma-informed knowledge and practices in school psychology: a pilot study and review. J. Appl. Psychol. 35, 176–199. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2018.1549174

Hajovsky, D. B., Chesnut, S. R., and Jensen, K. M. (2020). The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the development of teacher-student relationships. J. Sch. Psychol. 82, 141–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.09.001

Hall, L. (2013). The ‘come and go’ syndrome of teachers in remote Indigenous schools: listening to perspectives of Indigenous teachers about what helps teachers to stay and what makes them go. Aust. J. Indigenous Educ. 41, 187–195. doi: 10.1017/jie.2012.13

Hazel, S., and McCallum, F. (2016). The experience is in the journey: an appreciative case study investigating early career teachers’ employment in rural schools. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 26, 19–33.

Heffernan, A., Fogarty, R., and Sharplin, E. (2016). G ‘aim’ing to be a rural teacher? Improving pre-service teachers’ learning experiences in an online rural and remote teacher preparation course. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 26, 49–61.

Hobbs, C., Paulsen, D., and Thomas, J. (2019). Trauma-Informed Practice for Pre-Service Teachers. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1435

Hood, T. L., and Copeland, D. (2021). Student nurses’ experiences of critical events in the clinical setting: a grounded theory. J. Profess. Nurs. 37, 885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.07.007

Howard, J. A. (2013). Distressed or Deliberately Defiant? Managing Challenging Student Behaviour due to Trauma and Disorganised Attachment. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Howard, J. A. (2019). A systematic framework for trauma-informed schooling: complex but necessary!. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 28, 545–565. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1479323

Howell, P. B., Thomas, S., Sweeney, D., and Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Moving beyond schedules, testing and other duties deemed necessary by the principal: the school counsellor’s role in trauma informed practices. Middle Sch. J. 50, 26–34. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2019.1650548

Isobel, S., McCloughen, A., Goodyear, M., and Foster, K. (2021). Intergenerational trauma and its relationship to mental health care: a qualitative inquiry. Commun. Ment. Health J. 57, 631.643. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00698-1

Kangas-Dick, K., and O’Shaughnessy, E. (2020). Interventions that promote resilience among teachers: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 8, 131–146. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1734125

Karpouza, E., and Emvalotis, A. (2019). Exploring teacher-student relationship in graduate education: a constructivist grounded theory. Teach. High. Educ. 24, 121–140. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1468319

Keane, E. (2015). Considering the practical implementation of constructivist grounded theory in a study of widening participation in Irish higher education. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 18, 415–431. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2014.923622

Kelly, M., Clarke, S., and Wildy, H. (2019). School principals’ interactions with remote, Indigenous communities: a trajectory of encounters. Lead. Manag. 25, 33–50.

Kezleman, C., Hossack, N., Stavropoulos, P., and Burley, P. (2015). The Cost OF Unresolved Childhood Trauma AND Abuse IN Adults IN Australia. Vaughan, ON: Adults Surviving Child Abuse and Pegasus Economics.

Kim, S. W. (2019). Left-behind children: teachers’ perceptions of family-school relations in rural China. Compare 49, 584–601. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2018.1438885

Ko, S. J., Ford, J. D., Kassam-Adams, N., Berkowitz, S. J., Wilson, C., Wong, M., et al. (2008). Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Profess. Psychol. 39, 396–404. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.396

Koenen, A., Borremans, L. F. N., De Vroey, A., Kelchtermans, G., and Spilt, J. L. (2021). Strengthening individual teacher-child relationships: an intervention study among student teachers in special education. Front. Educ. (Lausanne) 6:769573. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.769573

Kourkoutas, E., and Giovazolias, T. (2015). School-based counselling work with teachers: an integrative model. Eur. J. Couns. Psychol. 3, 137–158. doi: 10.5964/ejcop.v3i2.58

Kreitzer, L., McLaughlin, A. M., Elliott, G., and Nicholas, D. (2016). Qualitative examination of rural service provision to persons with concurrent developmental and mental health challenges. Eur. J. Soc. Work 19, 46–61. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2015.1022859

Langton, M., Smith, K., Eastman, T., O’Neill, L., Cheesman, E., and Rose, M. (2020). Improving Family Violence Legal and Support Services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (Research Report, 25/2020). Centennial, CO: ANROWS.

Lawson, H. A., Caringi, J. C., Gottfried, R., Bride, B. E., and Hydon, S. P. (2019). Educators’ secondary traumatic stress, children’s trauma, and the need for trauma literacy. Harv. Educ. Rev. 89, 421–447. doi: 10.17763/1943-5045-89.3.421

Loomis, A. M., and Felt, F. (2020). Knowledge, skills, and self-reflection: linking trauma content to trauma-informed attitudes and stress in preschool teachers and staff. Sch. Ment. Health 13, 101–113. doi: 10.1007/s12310-020-09394-7

Lowe, K., Bub-Connor, H., and Ball, R. (2019). Teacher professional change at the cultural interface: a critical dialogic narrative inquiry into a remote school teacher’s journey to establish a relational pedagogy. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 29, 17–29.

Luke, A., Cazden, C., Coopes, R., Klenowski, V., Ladwig, J., Lester, J., et al. (2013). A summative evaluation of the Stronger Smarter learning communities project: 2013 Report – Volume 1 and Volume 2. Brisbane City, QLD: Queensland University of Technology.

Maguire-Jack, K., Jespersen, B., Korbin, J. E., and Spilsbury, J. C. (2020). Rural child maltreatment: a scoping literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse 22, 1316–1325. doi: 10.1177/1524838020915592

Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., and Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in research. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 54, 11–22. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

Mehta, D., Kelly, A. B., Laurens, K. R., Haslam, D., Williams, K. E., Wash, K., et al. (2021). Child maltreatment and long-term physical and mental health outcomes: an exploration of biopsychosocial determinants and implications for prevention. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. doi: 10.1007/s10578-021-01258-8

Mellin, E. A., Ball, A., Iachini, A., Togno, N., and Rodriguez, A. M. (2017). Teachers’ experiences collaborating in expanded school mental health: implications for practice, policy and research. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 10, 85–98. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2016.1246194

Menec, V., Bell, S., Novek, S., Minnigaleeva, G. A., Morales, E., Ouma, T., et al. (2015). Making rural and remote communities more age-friendly: experts perspectives on issues, challenges, and priorities. J. Aging Soc. Policy 27, 173–191. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2014.995044

Menzies, K. (2019). Understanding the Australian Aboriginal experience of collective, historical and intergenerational trauma. Int. Soc. Work 62, 1522–1534. doi: 10.1177/0020872819870585

Menzies, K., and Grace, R. (2020). The efficacy of child protection training program on the historical welfare context and Aboriginal trauma. Aust. Soc. Work 75, 62–75. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2020.1745857

Meyer, S., and Stambe, R. (2020). Indigenous women’s experiences of domestic and family violence, help seeking and recovery in regional Queensland. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 56, 443–458. doi: 10.1002/ajs4.128

Miller, J., and Berger, E. (2021). Supporting First Nations students with a trauma background in schools. Sch. Ment. Health 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09485-z