- 1Grupo de Investigación Avances en Investigación Psicológica, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Lima, Peru

- 2Facultad de Derecho y Humanidades, Universidad Señor de Sipán, Chiclayo, Peru

- 3Departamento de Gestión del Aprendizaje, Universidad del Pacífico, Lima, Peru

- 4Facultad de Humanidades, Escuela Profesional de Psicología, Universidad Continental, Lima, Peru

Objective: To examine the effect of family and academic satisfaction on the self-esteem and life satisfaction among Peruvian university students.

Method: Of the 1,182 Peruvian university students who participated, 364 were male; and 818 were female; and ranged from 17 to 39 years of age (mean = 20.67, SD = 4.4). The family satisfaction scale (FSS), the Escala breve de satisfacción con los estudios (EBSE; Brief Academic Satisfaction Scale in Spanish), Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale (RSES), and the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) were used to perform the assessments.

Results: The study model showed an adequate fit (χ2 19.5, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.977, RMSEA = 0.057), confirming the association between family satisfaction and life satisfaction (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), and the correlation between academic satisfaction and self-esteem (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) and life satisfaction (β = 0.23, p < 0.001). The model accounted for 42% of life satisfaction.

Conclusion: Family satisfaction and academic satisfaction affect self-esteem and life satisfaction.

Introduction

The mental health of university students has been prioritized as a subject of research during a health crisis (Sheldon et al., 2021), especially in Peru, where people aged 15–29 years (27.2% of the total population) (Chau and Saravia, 2016) have experienced anxiety, depression and somatization because of its implications to public health and education and as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Sánchez Carlessi et al., 2021).

Considering the importance of addressing the wellbeing of students in the university context, the literature has acknowledged the existence of factors that promote mental health in this population as well as risk factors that may undermine the emotional health and, especially, their learning experience in the higher-education level. In light of this situation, studying self-esteem and satisfaction with life is crucial because these variables are considered to be the promoters of the perception of positive wellbeing and a better quality of life among university students (Ruiz-González et al., 2018).

Life satisfaction

This variable is extremely important in the university stage not only because of its direct link to academic performance but also because it is an essential component of subjective wellbeing (Diener, 1984; Diener et al., 1985). Life satisfaction is defined as an individual’s positive assessment of their life in specific areas such as family, work, studies, friends, health, leisure, and so on (Alberto et al., 2019). In the realm of higher education, it has come to refer to the assessment made by a student when comparing their aspirations to their achievements, which has implications for the student’s enjoyment of the university experience (Dominguez-Lara and Campos-Uscanga, 2017).

Based on what has been reported in scientific literature, life satisfaction among higher education students has changed during the COVID-19 health emergency due to the impact of the disease (Rogowska et al., 2021), especially given its strong relationship with quality of life and personal goals (Huang et al., 2022), which have been affected by students’ concern about contracting the disease (Hossain et al., 2021), new variants (Carranza et al., 2022), precarious health systems (Knaul et al., 2021), financial impact (Kokkinos et al., 2022), and others. Authors such as Lei et al. (2020) report that being a student in COVID-19 times is a risk factor for mental health conditions compared with other age groups. This is because several studies have reported high prevalence of stress, depression, and anxiety (Ma et al., 2020) not only because of the new demands posed by online learning but also because students are not able to personally visit their classrooms and laboratories and socialize with their classmates (Villani et al., 2021). Moreover, educational institutions’ closure has resulted in a higher likelihood of having psychological alterations (Cao et al., 2020), and as a consequence, students’ perception of life satisfaction has been seriously affected.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented, the factors affecting university students’ life satisfaction mechanisms cannot be accurately identified. However, based on what has been observed in Perú and the evidence found in scientific literature, family satisfaction, study satisfaction, and self-esteem are variables that should be considered.

Predictors of life satisfaction

En caso de la satisfacción con los estudios, esta variable representa el goce y disfrute de las experiencias vividas como estudiante, que a su vez tiene una estrecha relación con la permanencia y culminación de los estudios a nivel universitario (Merino-Soto et al., 2017). Así, estar satisfecho académicamente tiene un impacto significativo sobre el proceso de aprendizaje (Yekefallah et al., 2021), sobre todo en entornos virtuales como el vivido a causa de la pandemia COVID-19 (Yawson and Yamoah, 2020), aunque, es necesario aclarar que el nivel de satisfacción con el aprendizaje en línea depende de factores como la conectividad, calidad de las plataformas virtuales, adaptación de estrategias pedagógicas, entre otros (She et al., 2021). Por otra parte, se ha visto una influencia sobre la percepción de la calidad de servicio (Borishade et al., 2021) y el rendimiento académico (Martínez-Jiménez and Ruiz-Jiménez, 2020), por ello, es considerada como un indicador importante de la calidad de la educación superior (Rossini et al., 2021).

Regarding its association with life satisfaction, fundamental studies, such as the longitudinal research performed by Hagmaier et al. (2018), have shown that life and career satisfaction are positively correlated by a bottom-up model, wherein satisfaction with the chosen career can predict life satisfaction. In the pandemic context, there is also evidence suggesting the predictive value of study satisfaction, such as a study conducted in Jordan, which concluded that improving the online learning experience would increase students’ satisfaction (Maqableh and Alia, 2021). Likewise, a study conducted in Thailand showed that students who regarded the online learning system to be good showed higher life satisfaction scores (Kornpitack and Sawmong, 2022).

Another predicting variable is family satisfaction, which is defined as the subjective content associated with cohesion between family members, their flexibility toward change, and their communication (Villareal-Zegarra et al., 2017). Some studies highlight the importance of family support for good academic performance (Silva et al., 2021). In the health emergency context, family dynamics have probably suffered significant changes (Martin-Storey et al., 2021) because lockdown and social distancing measures have forced family members to be in direct contact for long periods of time. In this sense, evidence suggests the importance of family support for the achievement of children’s personal and educational goals (Nasir et al., 2021). This had also been reported by Diener and Diener (2009), who conducted a transcultural study in 31 countries and found that family satisfaction significantly predicted participants’ life satisfaction. Moreover, a study conducted with university students in Mozambique concluded that family affects students’ perception of progress toward academic goals (Silva et al., 2021); this is particularly observed when democratic parenting methods are applied (Wang, et al., 2020).

The mediating role of self-esteem

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s level of appreciation for himself or herself, as determined by conscious self-evaluative observations and feelings (Abdulghani et al., 2020). Thus, it plays an important role in the development of personality and motivation and in boosting mental health; however, there are also factors that influence its development, such as adverse experiences in childhood and interactions with others, both family members and strangers (Tabernero et al., 2017).

For example, Cid-Sillero et al. (2020) describe it as one of the variables that best accounts for academic performance. This is supported by Hamza et al. (2020) who surveyed students from six health faculties in Saudi Arabia and found that self-esteem indirectly improves university performance. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, a high frequency of social media use, such as Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter, has been reported as the cause of body dissatisfaction and low self-esteem because subjects compared themselves with others (Vall-Roqué et al., 2021). Moreover, research describes its functional relation with variables such as life (Wójcik et al., 2022), family (Lee et al., 2021), and study satisfaction (Pendones et al., 2021).

For these reasons, based on the evidence shown, it could be concluded that students with higher family and study satisfaction tend to show higher self-esteem, which in turn increases their life satisfaction. Moreover, the moderating role of self-esteem should be highlighted because previous studies report this role in cognitive skills and students’ performance in tasks, exams, and other academic challenges (Cid-Sillero et al., 2020), which also has a partial moderation effect that accounts for students’ life satisfaction (Kong et al., 2012; Kong and You, 2013).

Study hypotheses

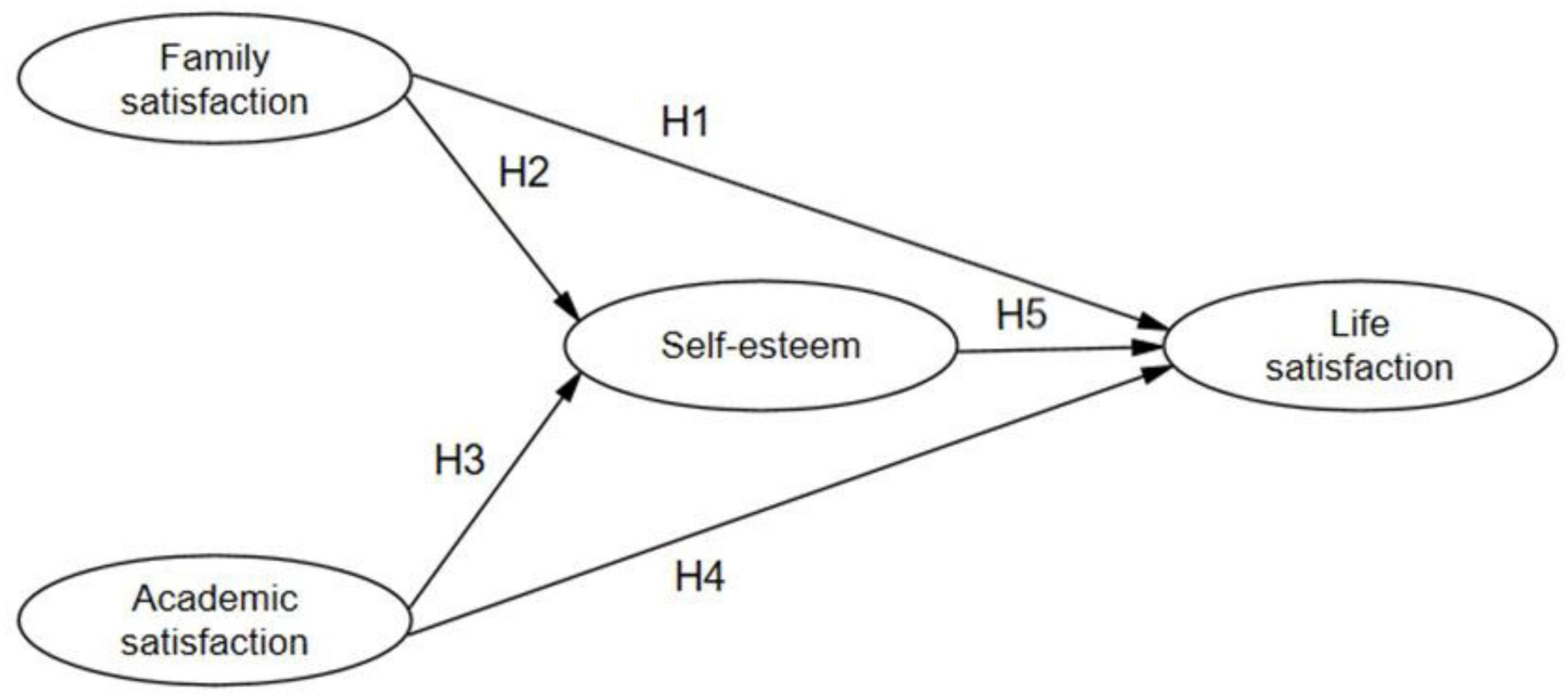

Based on the evidence presented, it is reasonable to assume that family and academic satisfaction have functional relationships with self-esteem and life satisfaction. The hypotheses proposed are shown in Figure 1:

H1: Family satisfaction has a direct and significant effect on life satisfaction among Peruvian university students.

H2: Family satisfaction has a direct and significant effect on the self-esteem of Peruvian university students.

H3: Academic satisfaction has a direct and significant effect on the self-esteem of Peruvian university students.

H4: Academic satisfaction has a direct and significant effect on life satisfaction among Peruvian university students.

H5: Self-esteem acts as a mediator between family and academic satisfaction and life satisfaction among Peruvian university students.

Study objective

Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationships between family satisfaction, academic satisfaction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction among Peruvian university students.

Materials and methods

Study design

Cross-sectional predictive study with a single variable measurement, as data were collected at a single moment and at a single time (Ato et al., 2013).

Study participants

A total of 1,182 university students from private universities in the Peruvian geographical divisions of Costa, Sierra, and Selva participated in the study: 364 were male (30.8%) and 818 were female (69.2%); their ages ranged from 17 to 39 years (mean = 20.67, SD = 4.4). The students were selected through non-probabilistic sampling.

Instruments

The family satisfaction scale (FSS; Olson et al., 2006; validated in the Peruvian context by Villareal-Zegarra et al., 2017) assesses the family members’ perceptions of their level of satisfaction with family functioning. This scale comprises 10 Likert-type items with five possible responses: 1 = extremely dissatisfied, 2 = generally dissatisfied, 3 = undecided, 4 = generally satisfied, and 5 = extremely satisfied. The FSS showed good internal consistency in this study, ω = 0.92.

The Escala breve de satisfacción con los estudios (a brief academic satisfaction scale in Spanish) (EBSE; Merino-Soto et al., 2017) evaluates student satisfaction with their study methods, academic performance, and overall satisfaction with their studies. It comprises three items with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on a five-option Likert-type scale. The scale achieved internal consistency in this study (Positive self-esteem ω = 0.92, Negative self-esteem ω = 0.92).

The Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES; Atienza et al., 2000; validated in the Peruvian context by Ventura-León et al., 2018) evaluates the individual’s general perception of self-esteem. The RSES is composed of 10 items that require a Likert-type response from one out of four alternatives: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree. The reliability of the RSES for this study was acceptable, ω = 0.83.

The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985; validated in the Peruvian context by Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2018) comprises five items, each with Likert-type response options (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The reliability of the SWLS for this study was acceptable, ω = 0.92.

Study procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Unión (Reference: 2021-CEUPeU-0022.). In view of the social isolation measures imposed by the Peruvian government to prevent the risk of COVID-19 contagion, a virtual questionnaire was designed using Google Forms, and the link was distributed via social media (Facebook and WhatsApp). An informed consent form was presented in the first section of the questionnaire, along with the study’s objectives and a declaration stating that participation was voluntary and anonymous. Moreover, all the ethical principles of human research described in the declaration of Helsinki have been followed.

Statistical analysis

The theoretical model was analyzed using structural equation modeling and the maximum likelihood method (MLM) estimator, which is suitable for numerical variables and is resistant to inferential normality deviations (Muthen and Muthen, 2017). The comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were used to assess fit. A CFI value of >0.90 (Bentler, 1990), an RMSEA value of <0.080 (MacCallum et al., 1996), and an SRMR value of <0.080 (Browne and Cudeck, 1992) were used. All analyses were carried out with the demographic characteristics of sex and age in mind to obtain a more accurate estimate of the model’s correlations. Regarding the reliability analysis, the internal consistency method with omega coefficient (ω) was used, which is a better alternative given the widely discussed limitations of the alpha coefficient (Sijtsma, 2009; Cho, 2016). For this coefficient, the formula was corrected using correlated errors (Raykov, 2004).

Data analysis was performed using the “lavaan” package (Rosseel, 2012) in the R Statistical Software version 4.0.5 (R Core Team, 2007).

Results

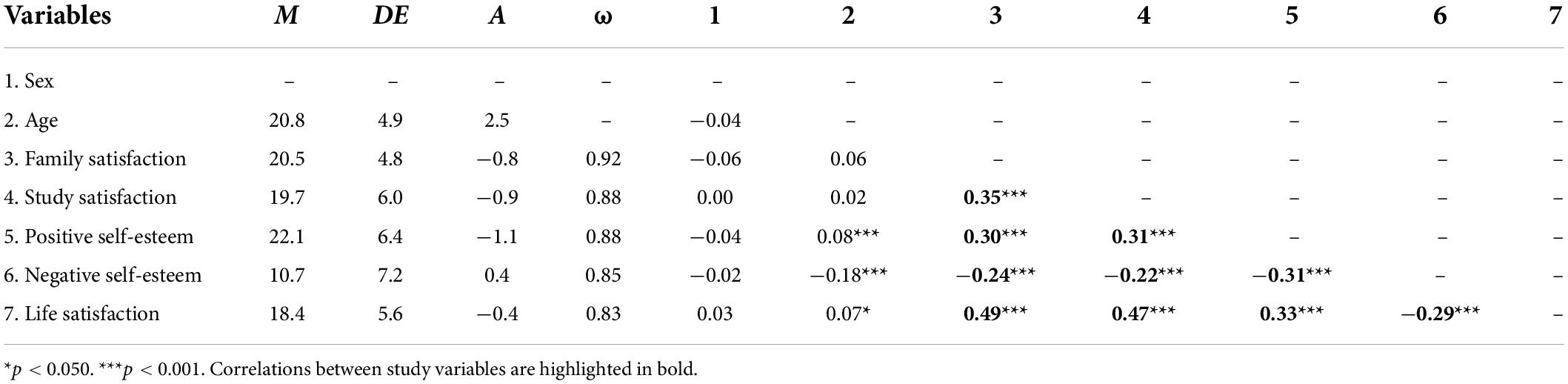

Variable scores ranged from 0 to 30 for ease of interpretation. Table 1 presents the correlation matrix; descriptive statistics of study variables with correlation results between 0.22 and 0.49 are presented as absolute values for study variables, which are written in bold. Moreover, the table also shows omega internal consistencies with correlated error correction, resulting in 0.83 and 0.92.

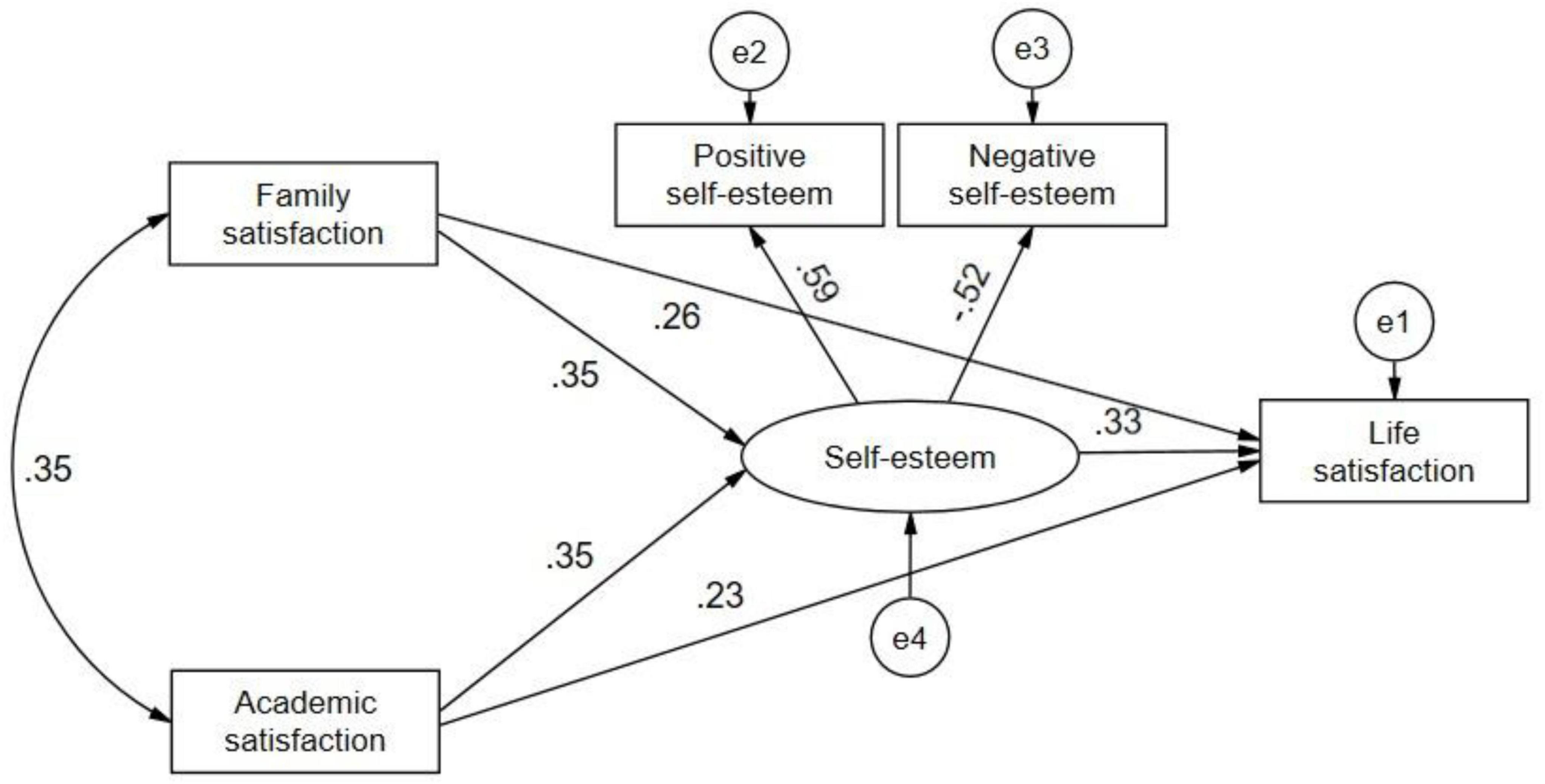

The analysis demonstrated that the theoretical model had an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (4) = 19.5, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.977, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.020. These results confirm H1 and H2, that is, family satisfaction was positively correlated with life satisfaction (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (β = 0.35, p < 0.001); as well as H3 and H4, that is, academic satisfaction was correlated with self-esteem (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) and life satisfaction (β = 0.23, p < 0.001); and H5, that is, self-esteem was correlated with life satisfaction (β = 0.33, p < 0.001). In addition, the results explained 42% of the variance in life satisfaction. The standardized solution after controlling for gender and age is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Results of the structural model explaining life satisfaction. Standardized estimated parameters after controlling for gender and age are shown.

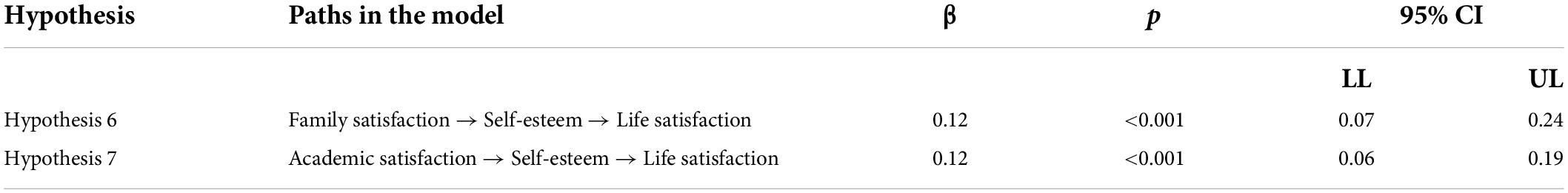

A total of 5,000 bootstrapping iterations were performed for the mediation analysis (see Table 2 for results). Self-esteem has a statistically significant mediation effect on the association between family satisfaction and life satisfaction (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), which confirms H6; similarly, self-esteem mediates the relationship between academic satisfaction and life satisfaction (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), which confirms H7. Table 2 presents these results with their confidence intervals.

Discussion

Given the importance of addressing factors that affect university students’ wellbeing, this study aimed to examine the impact of family satisfaction and academic satisfaction on the life satisfaction of Peruvian university students, with a focus on self-esteem as a moderating variable in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, our findings indicate that these variables were both directly and indirectly correlated.

Firstly, our findings showed a direct effect of family satisfaction on life satisfaction. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, these results are similar to the ones reported by a transcultural study conducted with samples from 31 countries (Diener and Diener, 2009), which found that family satisfaction significantly predicted life satisfaction. Moreover, our findings are consistent with other studies conducted with university students which, despite not including the family satisfaction variable, included variables with a similar concept and showed a positive correlation with life satisfaction. These variables are family cohesion (Koo and Park, 2005), parental style perception (Seibel and Johnson, 2001), and social family support (Kong et al., 2012; Schnettler et al., 2015; Fakunmoju et al., 2016). More recent studies also found that family satisfaction is one of the main factors associated with life satisfaction among teenagers (Moreno-Maldonado et al., 2020; Schnettler et al., 2022) and adults (Szcześniak and Tułecka, 2020). Although studies exploring the association between these variables in the COVID-19 pandemic are scarce, our findings are consistent with Ram et al. (2022), who found that family satisfaction positively predicted life satisfaction in a group of adults in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic.

Second, another interesting finding is the confirmation of the direct and significant relationship between academic satisfaction and life satisfaction. Although previous studies on academic satisfaction are limited, our findings are consistent with those of Hagmaier et al. (2018), who demonstrated that life satisfaction and satisfaction with the chosen career were positively related and that this correlation is adequately represented by a bottom-up model in which satisfaction with the chosen career predicts satisfaction with life.

Thus, life satisfaction, which is an essential element of the subjective sense of wellbeing (Diener, 1984), may be explained from a theoretical viewpoint using a bottom-up approach (Brief et al., 1993) as resulting from the inclusion of satisfaction in other well-defined areas of life. This suggests that life satisfaction depends upon a person’s satisfaction with certain other aspects of life, such as family and studies; hence, satisfaction with one aspect of life has a positive effect on the overall life satisfaction. According to this approach, judgments related to life satisfaction may vary depending on the situation; therefore, positive and negative events may affect subjects’ global life perception (Ilies et al., 2018). For this reason, our findings suggest that a positive perception of family and educational surroundings positively affects the way in which life satisfaction is perceived.

Third, our findings also indicate that family satisfaction is a strong predictor of self-esteem among Peruvian university students. This is consistent with previous reports (Phillips, 2012; Ercegovac et al., 2021), which indicated that, among all functional components of the family, family satisfaction was the greatest predictor of self-esteem. Fourth, academic satisfaction was also found to be a predictor of the participants’ self-esteem. Thus, a positive perception of one’s own academic experience contributes to increased self-esteem. These findings indicate that both the family and educational environments have a direct effect on self-evaluation and self-appreciation.

Additionally, the positive relation between self-esteem and life satisfaction was confirmed, which is consistent with prior research indicating that self-esteem is one of the strongest predictors of life satisfaction before (Kong et al., 2012; Agyar, 2013; Kong and You, 2013; Mehmood and Shaukat, 2014) and during the pandemic (Kondratowicz et al., 2021; Ozer, 2022). According to these results, self-esteem is directly correlated with life satisfaction, so the higher the self-esteem levels, the higher life satisfaction levels will be.

Because low self-esteem is associated with insecurity, fear of failure, and negativism, it probably prevents subjects from following their personal goals with optimism, which results in a negative perception of their lives (Mehmood and Shaukat, 2014). Moreover, self-esteem, as a psychological resource, may be a factor helping students deal with the challenges associated with the abrupt changes posed by the pandemic, such as online learning, limited social interaction, constant concern about contracting the disease, one’s health, and their friends and relatives’ health. Thus, students’ positive perception of themselves and their capacities positively affects their ability to overcome the obstacles emerging during the pandemic (Ozer, 2022), which results in a positive attitude toward life.

Finally, as per the study’s mediating hypotheses, the indirect effect of family and academic satisfaction on life satisfaction via self-esteem was significant in Peruvian university students. This is consistent with earlier research indicating that self-esteem has a partial mediating role in explaining life satisfaction among university students, before (Kong et al., 2012; Kong and You, 2013) and during the pandemic (Ozer, 2022). These findings suggest that individuals who report higher levels of family and academic satisfaction were more likely to value themselves positively, which in turn, leads to an increase in their satisfaction with life. In the COVID-19 scenario, self-esteem is a resilience factor with which a positive perception of educational and family surroundings results in a positive global life perception, considering that a subject with high self-esteem will apply beneficial coping strategies when facing the uncertainties associated with a worldwide health emergency (Ozer, 2022).

To provide recommendations for future research, it is necessary to consider some of this study’s shortcomings. Two significant limitations are as follows. First, as this study employed a cross-sectional design in which data were collected at a particular moment in time, no causal relationships or inferences about the evolution over time of the associations between variables can be drawn. Future researchers can validate explanatory models by employing longitudinal designs that provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena being studied. Second, study variables were assessed exclusively on the basis of self-reports, which may have led to biases in data collection, such as social desirability bias; we recommend that future studies consider the use of different analytical techniques that add to our understanding of the study variables. Third, as participants attend private universities, the findings of this study only allow us to understand the relationship between the study variables in this specific group of university students, thus requiring further research to corroborate the associations found in students from public universities. Furthermore, future studies should include socioeconomic factors to explore their influence on this model.

Thus, our study met the proposed objectives, as we were able to demonstrate the effect of family and academic satisfaction on self-esteem and life satisfaction among Peruvian university students. The practical implications of these results are linked to the importance of understanding the factors that contribute to the improvement of satisfaction with life and the self-esteem of university students in the health crisis context. Thus, based on this understanding, educational policies and psychological support programs can be implemented, aimed at promoting welfare among university students, as part of a comprehensive set of mental health strategies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Comité de ética de la Universidad Peruana Unión. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

RC and OM-B conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. SL and IC-O contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdulghani, A. H., Almelhem, M., Basmaih, G., Alhumud, A., Alotaibi, R., Wali, A., et al. (2020). Does self-esteem lead to high achievement of the science college’s students? A study from the six health science colleges. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.11.026

Agyar, E. (2013). Life satisfaction, perceived freedom in leisure and self-esteem: the case of physical education and sport students. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 93, 2186–2193. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.185

Alberto, M., Ramírez, N., Lorena, C., Flores, V., Sonora, E. C., and De, et al. (2019). Palabras clave: autoestima, satisfacción con la vida, estudiantes universitarios. Abstract 4, 14–28.

Atienza, F. L., Moreno, Y., and Balaguer, I. (2000). Análisis de la dimensionalidad de la Escala de Autoestima de Rosenberg en una muestra de adolescentes valencianos. Rev. Psicol. Univ. Tarracon. 23, 29–42.

Ato, M., López-García, J. J., and Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 29, 1038–1059.

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 21, 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005

Borishade, T. T., Ogunnaike, O. O., Salau, O., Motilewa, B. D., and Dirisu, J. I. (2021). Assessing the relationship among service quality, student satisfaction and loyalty: the NIGERIAN higher education experience. Heliyon 7:e07590. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07590

Brief, A. P., Butcher, A. H., George, J. M., and Link, K. E. (1993). Integrating bottom-up and top-down theories of subjective well-being: the case of health. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 64, 646–653. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.646

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Carranza, R., Mamani-Benito, O., Ruiz, P., and Mejia, C. (2022). Escala de preocupación por el contagio de una variante de la COVID-19 (EPCNVCov-19). Rev. Cubana Med. Militar. 51:e1714.

Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Ventura-León, J., García, C. H., Barboza-Palomino, M., Arias, W. L., Dominguez-Vergara, J., et al. (2018). Evidencia psicométrica de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en adultos mayores peruanos. Rev. Cienc. Salud 16, 488–506.

Chau, C., and Saravia, J. C. (2016). Does stress and university adjustment relate to health in peru? J. Behav. Health Soc. 8, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbhsi.2017.08.002

Cho, E. (2016). Making reliability reliable: A systematic approach to reliability coefficients. Organizat. Res. Methods 19, 651–682. doi: 10.1177/1094428116656239

Cid-Sillero, S., Pascual-Sagastizabal, E., and Martínez-de-Morentin, J.-I. (2020). Influence of self-esteem and attention on the academic performance of ESO and FPB students. Rev. Psicodidáctica 25, 59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psicoe.2019.10.001

Diener, E., and Diener, M. (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 653–63. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2352-0_4

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 49, 71–75.

Dominguez-Lara, S. A., and Campos-Uscanga, Y. (2017). Influence of study satisfaction on academic procrastination in psychology students: a preliminary study. Liberabit 23, 123–135. doi: 10.24265/liberabit.2017.v23n1.09

Ercegovac, I. R., Maglica, T., and Ljubetiæ, M. (2021). The relationship between self-esteem, self-efficacy, family and life satisfaction, loneliness and academic achievement during adolescence. Croatian J. Educat. 23, 65–83. doi: 10.15516/cje.v23i0.4049

Fakunmoju, S., Donahue, G. R., McCoy, S., and Mengel, A. S. (2016). Life satisfaction and perceived meaningfulness of learning experience among first-year traditional graduate social work students. J. Educat. Pract. 7, 49–62.

Hagmaier, T., Abele, A. E., and Goebel, K. (2018). How do career satisfaction and life satisfaction associate? J. Manag. Psychol. 33, 142–160. doi: 10.1108/JMP-09-2017-0326

Hamza, A., Almelhem, M., Basmaih, G., Alhumud, A., Alotaibi, R., Wali, A., et al. (2020). Does self-esteem lead to high achievement of the science college’s students? A study from the six health science colleges. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 636–642.

Hossain, J., Ahmmed, F., Rahma, A., Sanam, S., Bin, T., and Mitra, S. (2021). Impact of online education on fear of academic delay and psychological distress among university students following one year of COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh. Heliyon 7:e07388. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07388

Huang, Z., Zhang, L., Wang, J., Xu, L., Wang, T., Tang, Y., et al. (2022). Family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of meaning in life and depression. Heliyon 8:e09282. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09282

Ilies, R., Yao, J., Curseu, P. L., and Liang, A. X. (2018). Educated and happy: a four-year study explaining the links between education job fit, and life satisfaction. Appl. Psychol. 68, 150–176. doi: 10.1111/apps.12158

Knaul, F., Touchton, M., Atun, R., Frenk, J., Martínez Valle, A., McDonald, T., et al. (2021). Punt politics as failure of health system stewardship: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic response in brazil and mexico. Lancet Regional Health Am. 4:100086. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100086

Kokkinos, C., Tsouloupas, C., and Volgaridou, I. (2022). The effects of perceived psychological, educational, and financial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Greek university students’ satisfaction with life through mental health. J. Affect. Disor. 300, 289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.114

Kondratowicz, B., Godlewska-Werner, D., Połomski, P., and Khosla, M. (2021). Satisfaction with job and life and remote work in the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 10, 49–60. doi: 10.5114/cipp.2021.108097

Kong, F., and You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Soc. Indicat. Res. 110, 271–279. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6

Kong, F., Zhao, J., and You, X. (2012). Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: the mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Personal. Individ. Diff. 53, 1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.032

Koo, H. Y., and Park, H. S. (2005). Levels of and predictors of satisfaction with life in Korean adolescent. Child Health Nurs. Res. 11, 322–329.

Kornpitack, P., and Sawmong, S. (2022). Empirical analysis of factors influencing student satisfaction with online learning systems during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. Heliyon 8:e09183. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09183

Lee, J., Lim, H., Allen, J., and Choi, G. (2021). Multiple mediating effects of conflicts with parents and self-esteem on the relationship between economic status and depression among middle school students since COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 12:712219. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712219

Lei, L., Huang, X., Zhang, S., Yang, J., Yang, L., and Xu, M. (2020). Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit 26:e924609. doi: 10.12659/msm.924609

Ma, Z., Zhao, J., Li, Y., Chen, D., Wang, T., Zhang, Z., et al. (2020). Mental health problems and correlates among 746 217 college students during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 29:e181. doi: 10.1017/s2045796020000931

Maqableh, M., and Alia, M. (2021). Evaluation online learning of undergraduate students under lockdown amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: The online learning experience and students’ satisfaction. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 128:106160. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106160

Martínez-Jiménez, R., and Ruiz-Jiménez, M. C. (2020). Improving students’ satisfaction and learning performance using flipped classroom. Int. J. Manag. Educat. 18:100422. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100422

Martin-Storey, A., Dirks, M., Holfeld, B., Dryburgh, N., and Craig, W. (2021). Family relationship quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: The value of adolescent perceptions of change. J. Adolesc. 93, 190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.11.005

Mehmood, T., and Shaukat, M. (2014). Life satisfaction and psychological well-being among young adult female university students. Int. J. Liberal Arts Soc. Sci. 2, 143–153.

Merino-Soto, C., Dominguez-Lara, S., and Fernandez-Arata, M. (2017). Validación inicial de una escala breve de satisfacción con los estudios en estudiantes universitarios de lima. Educación Med. 18, 74–77.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., and Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling of fit involving a particular measure of model. Psychol. Methods 13, 130–149.

Moreno-Maldonado, C., Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Camacho, I., Rivera, F., Moreno, C., and Matos, M. G. (2020). Factors associated with life satisfaction of adolescents living with employed and unemployed parents in Spain and Portugal: A person focused approach. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 110:104740. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104740

Nasir, A., Harianto, S., Rahmadi, C., Indrawati, R., Rahmawati, P., and Putra, P. (2021). The outbreak of COVID-19: Resilience and its predictors among parents of schoolchildren carrying out online learning in Indonesia. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health 12:100890. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100890

Olson, D. H., Gorall, D. M., and Tiesel, J. W. (2006). FACES IV package. Minneapolis, MN: Life Innovation, Inc.

Ozer, S. (2022). Social Support, Self-efficacy, Self-esteem, and Well-being During COVID-19 Lockdown: A Two-wave Study of Danish Students. PsyArXiv [preprint] doi: 10.31234/osf.io/kg7mx

Pendones, J., Flores, Y., Espino, G., and Durán, F. (2021). Autoconcepto, autoestima, motivación y su influencia en el desempeño académico. Caso: alumnos de la carrera de Contador Público. RIDE. Revista Iberoamericana para Investigación Desarrollo Educativo 12:e015. doi: 10.23913/ride.v12i23.1008

Phillips, T. M. (2012). The influence of family structure vs. family climate on adolescent Well-Being. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 29, 103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0254-4

R Core Team (2007). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Computer Software]. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.r-project.org/

Ram, D., Al-Zahrani, S. A., and Alshehri, M. A. (2022). The levels and relationships of family and life satisfaction among saud arabian-a cross sectional study during covid 19 pandemic. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 12, 5–9. doi: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20221201.02

Raykov, T. (2004). Point and interval estimation of reliability for muliple-component measuring instruments via linear constraint covariance structure modeling. Struct. Equat. Model. 11, 342–356. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_3

Rogowska, A. M., Ochnik, D., Kuśnierz, C., Jakubiak, M., Schutz, A., Held, M., et al. (2021). Satisfaction with life among university students from nine countries: Cross-national study during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Salud Públ. 21:2262. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12288-1

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan?: An R Package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–93. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rossini, S., Bulfone, G., Vellone, E., and Alvaro, R. (2021). Nursing students’ satisfaction with the curriculum: An integrative review. J. Profess. Nurs. 37, 648–661. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.02.003

Ruiz-González, P., Medina-Mesa, Y., Zayas, A., and Gómez-Molinero, R. (2018). Relación entre la autoestima y la satisfacción con la vida en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. Int. J. Devel. Educat. Psychol. 1, 67–76. doi: 10.17060/ijodaep.2018.n1.v2.1170

Sánchez Carlessi, H. H., Yarlequé Chocas, L. A., Alva, L. J., Nuñez, LLacuachaqui, E. R., Arenas Iparraguirre, C., et al. (2021). Anxiety, depression, somatization and experiential avoidance indicators in peruvian university students in quarantine by COVID-19. Rev. Facult. Med. Hum. 21, 346–353.

Schnettler, B., Denegri, M., Miranda, H., Sepúlveda, J., Orellana, L., Paiva, G., et al. (2015). Family support and subjective well-being: an exploratory study of university students in southern Chile. Soc. Indicat. Res. 122, 833–864. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0718-3

Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Grunert, K. G., Grønhøj, A., Jiménez, P., Lobos, G., et al. (2022). Satisfaction with life, family and food in adolescents: Exploring moderating roles of family-related factors. Curr. Psychol. 41, 802–815. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00618-2

Seibel, F. L., and Johnson, W. B. (2001). Parental Control, Trait Anxiety, and Satisfaction with Life in College Students. Psychol. Rep. 88, 473–480. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.473

She, L., Ma, L., Jan, A., Sharif, H., and Rahmatpour, P. (2021). Online learning satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic among chinese university students: the serial mediation model. Front. Psychol. 23:e14039. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.743936

Sheldon, E., Simmonds-Buckley, M., Bone, C., Mascarenhas, T., Chan, N., Wincott, M., et al. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disor. 287, 282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.054

Sijtsma, K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika 74, 107–120. doi: 10.1007/S11336-008-9101-0

Silva, A., Vautero, J., and Usssene, C. (2021). The influence of family on academic performance of Mozambican university students. Int. J. Educat. Devel. 87:102476. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102476

Szcześniak, M., and Tułecka, M. (2020). Family functioning and life satisfaction: the mediatory role of emotional intelligence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 223–232. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S240898

Tabernero, C., Serrano, A., and Mérida, R. (2017). Estudio comparativo de la autoestima en escolares de diferente nivel socioeconómico. Psicol. Educat. 23, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pse.2017.02.001

Vall-Roqué, H., Andres, A., and Saldaña, C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on social network sites use, body image disturbances and self-esteem among adolescent and young women. Progr. Neuro Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psych. 110:110293. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110293

Ventura-León, J., Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Barboza, P. M., and Salas, G. (2018). Evidencias psicométricas de la Escala de Autoestima en adolescentes Limeños. Rev. Int. Psicol. 52, 44–60.

Villani, L., Pastorino, R., Molinari, E., Anelli, F., Ricciardi, W., Graffigna, G., et al. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being of students in an Italian university: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Global Health 17:39. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00680-w

Villareal-Zegarra, D., Copez-Lonzoy, A., Paz-Jesus, A., and Costa-Ball, C. (2017). Validez y confiabilidad de la Escala Satisfacción familiar en estudiantes universitarios de Lima Metropolitana, Perú. Actual. Psicol. 31, 89–98. doi: 10.15517/ap.v31i123.23573 **kanthi,

Wang, Y., Nakamura, T., and Sanefuji, W. (2020). The in fl uence of parental rearing styles on university students’ critical thinking dispositions: The mediating role of self-esteem. Thinking Skills Creat. 37:100679. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100679

Wójcik, D., Kutnik, J., Szalewski, L., and Borowics, J. (2022). Predictors of stress among dentists during the COVID-19 epidemic. Informe Científico 12:7859. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11519-8

Yawson, D. E., and Yamoah, F. A. (2020). Understanding satisfaction essentials of E-learning in higher education: A multi-generational cohort perspective. Heliyon 6:e05519. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05519

Keywords: academic satisfaction, family satisfaction, life satisfaction among, Peru, students universities

Citation: Carranza Esteban RF, Mamani-Benito O, Castillo-Blanco R, Lingan SK and Cabrera-Orosco I (2022) Influence of family and academic satisfaction on life satisfaction among Peruvian university students in the times of COVID-19: The mediating role of self-esteem. Front. Educ. 7:867997. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.867997

Received: 01 February 2022; Accepted: 06 July 2022;

Published: 15 August 2022.

Edited by:

Marta Moskal, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Leire Aperribai, University of the Basque Country, SpainDavid Molero, University of Jaén, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Carranza Esteban, Mamani-Benito, Castillo-Blanco, Lingan and Cabrera-Orosco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renzo Felipe Carranza Esteban, cmNhcnJhbnphQHVzaWwuZWR1LnBl

Renzo Felipe Carranza Esteban

Renzo Felipe Carranza Esteban Oscar Mamani-Benito

Oscar Mamani-Benito Ronald Castillo-Blanco

Ronald Castillo-Blanco Susana K. Lingan1

Susana K. Lingan1