- Department of English Language and Literature, College of Arts, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Education in Saudi Arabia employs English as a foreign language. Several researchers have examined language policies governing English use. Current research suggests that official policies do not exist and self-English language policies (ELPs) are in place without any type of governance. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the nature of self-ELPs in Saudi Arabia and how the country can benefit from engendering institutional changes. An eight-item survey was conducted with an open-ended section and received responses from faculty members affiliated with English departments around the country (n = 213). Semi-structured interviews with eight chairpersons from different English departments were also organized. The findings reveal that the majority of faculty practice self-ELPs very frequently, in both official and non-official situations. It is concluded that English departments in the academia in Saudi Arabia are ready to enforce official ELPs and accept the idea of internationalizing their academic services worldwide.

Introduction

The existence of more than one language in any context stimulates communities to govern the use of these languages to serve different objectives, such as better communication, avoidance of conflict, and economic purposes (e.g., Tikly, 2004; Coleman and Capstick, 2012). Therefore, English language policies (ELPs) commonly exist in various “English as a foreign language” (EFL) contexts and play a significant role in managing language usage and achieving strategic goals of countries/institutions (e.g., Sperduti, 2017). Almost every higher education institution in Saudi Arabia has an English department that offers academic graduate and postgraduate programs and teachings of English courses to students at the institutional level (Alnasser, 2018a). The number of faculty members affiliated with such departments is relatively high and includes non-Arabic speaking members also. Therefore, language use in these departments in Saudi Arabia can become rather complicated and arbitrary.

The prominent use of English worldwide has influenced its presence in different EFL contexts. The reliance on expatriate experts in these settings to work on the development of the economy and infrastructure has been strongly impacted by the presence of Western culture in the Gulf region (Khalaf, 2002). Exposure to English became inevitable in daily life through mediums such as magazines, televisions, and smartphones. Currently, English is used as the lingua franca for communicating with expatriates working in various places such as shops and companies, and as different service providers. English has also started dominating the social landscape in universities, hospitals, and shopping malls, compelling local citizens to acquire partial language skills to receive basic services (Badry and Willoughby, 2016). Such a situation has led the young generation in the Gulf region to become somewhat ambivalent about their mother tongue and have started believing that proficiency in English precedes that of the mother tongue (Khalaf, 2002, 2005; Al-Issa and Dahan, 2011). As such, the emergence of language planning and policies (LPPs) has increased over recent decades.

The field of ELPs in Saudi Arabia has gained increasing attention in recent years (e.g., Payne and Almansour, 2014; Almoaily and Alnasser, 2019). The literature suggests that formal ELPs do not exist (Almoaily and Alnasser, 2019), while self-ELPs seem to control the balance of how much and when each language is to be used. Here, self-ELPs refer to implicit (non-written) policies practiced freely by concerned individuals and with no governance whatsoever. Such freedom may call for the standardization of ELPs in the Saudi context, which is seen as a form of institutionalization—that is to say establishing a norm by an authoritative body for serving a wider purpose (Costa et al., 2018). Establishing a norm in any context may facilitate coping with encountered challenges, such as communication, documentation as well as interaction between two entities (Peltokorpi and Vaara, 2017). To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, the existing literature has neither addressed current self-ELPs at the English department level nor suggested how these policies can be implemented for institutional improvement. Thus, this study attempts to answer the following questions:

1- How do faculty members practice self-ELPs at Saudi English departments?

2- How can policymakers implement self-ELPs for institutional development?

Background

Language Planning and Policies: An Overview

In the late 1950s, “language planning” was introduced by Einar Haugen as a term that refers to “all conscious efforts that aim at changing the linguistic behavior of a speech community” (Deumert, 2005, p. 384). Such planning may commence with processes as small as modifying or introducing new words, and as large as introducing a new language (ibid). Fishman (1974); Karam (1974), and Jernudd and Gupta (1971) share similar views that language planning is a political and administrative process meant to solve language-related issues within a society. Tauli (1974, p. 561) went further and delineated that language planning involves the “activity of regulating and improving existing languages or creating new common regional, national, or international languages.” By contrast, language policy can differ from language planning in practical terms, as it refers to “the more general linguistic, political, and social goals underlying the actual language planning process” (Deumert, 2005, p. 384). In the words of Kaplan and Baldauf (1997, p. xi), it is the “body of ideas, laws, regulations, rules, and practices intended to achieve the planned language change in a society, group, or system.” Therefore, LPPs can not only play a significant role in governing and guiding language use within a society or a certain context but also be employed to achieve certain goals (e.g., cultural and/or educational goals).

The nature of LPPs can differ from one context to another. For example, their classification can be based on their genesis (macro- and micro-level policies) as their emergence can be from higher authorities and passed down to lower entities, and vice versa. They can also be classified according to their nature or degree of formality as implicit or explicit policies (Schiffman, 1996; Johnson, 2013). Explicit policies tend to have a higher degree of formality, whereas implicit policies tend to have a lower degree of formality. Moreover, implicit policies may suggest that individuals within a context practice them without being aware of their existence, given their “implicit” nature.

English in Gulf Higher Education

Recently, the English language in the Arab world has received increasing attention. Some policymakers are inclined to promote educational policies involving English use. Badry and Willoughby (2016) explain that reforming higher education in the Gulf region is being attempted, and one of the underlying assumptions of the reform process is to adopt the English language as the medium of instruction, which they claim is the “efficient shortcut” to achieve educational reforms. Nonetheless, such reforms may occur while preserving and protecting the Arabic language in the face of the dominance of English. The stress on English in modern higher education has been argued to reflect the acceptance and beliefs held by policymakers that this language can catalyze changes in education by facilitating access to the knowledge offered by developed countries, and therefore, match up to their advancements (Tikly, 2004; Alhendi, 2019). Tickoo (2006, p. 170) describes such trend as “the hunger for English,” a phenomenon that is becoming universal (e.g., Wachter and Maiworm, 2008; Conceição, 2020), and is viewed by Coleman (2006) as an attempt to attract international students. Badry and Willoughby (2016) interviewed university academics and officials in the Gulf region about the trend of English as a medium of instruction, and the majority explained that equipping graduates with high proficiency skills in English is a priority to prepare them for the job market. According to Coleman (2010), equipping students with English language skills can further help them excel in their careers and future studies. The interviewees in Badry and Willoughby (2016) further shared the view that English is becoming the language of science, research, and technology, a view that is also shared by Alhendi (2019); Kachru (1986), and Widdowson (2000), who further explained that English is becoming the vehicle of most cultures and lifestyles. According to Tikly (2004, p. 16), this view can promote standardizing “Western measures of skill technology, innovation, and productivity in ways that are quickly recalibrating regional economic and political relationships.” These priorities can lead to negligence of the mother tongue (e.g., Gunnarsson, 2001) and learners can also find themselves in a stressful race of mastering English and learning various subjects in a foreign language (i.e., English) (Kuteeva and Airey, 2014; Badry and Willoughby, 2016). In this regard, several studies conclude that reliance on the first language in higher education can promote quality learning (e.g., Benson, 2004; Trudell, 2009).

Language in Education Policies

Multilingualism is a prominent characteristic of language in education policy. The existence of more than one language in most countries leads to the emergence of issues under various settings, for example, at the workspace. Therefore, regulating language use through language policies can help mitigate and support individuals and organizations to overcome any issues (Tickoo, 2006; Adriano et al., 2021). Alhendi (2019) argues that setting one language in a country’s education can be positive and stimulate its economy. Most non-English-speaking countries advocate a national language as a sign of unity while recognizing the need for English to facilitate communication, nationally and internationally (Liddicoat and Kirkpatrick, 2020). The use of languages in education for different purposes, such as instruction and communication, is controversial, as is the case in most South Asian countries (Tickoo, 2006; Coleman, 2010; Coleman and Capstick, 2012), Somalia (Eno et al., 2019), and the Philippines (Adriano et al., 2021). As explained earlier, the influence of Westernization has impacted educationalists’ beliefs about the superiority of the English of the West and in the formation of the educational setting (Tickoo, 2006). For example, in Sweden, English has dominated across higher education and academics have been concerned about Swedish being marginalized, which has driven the production of macro policies to govern English use in the academic setting (Ek et al., 2013; Kuteeva and Airey, 2014). Sperduti (2017) explains that universities have roles in advancing knowledge as well as preserving heritage. Nevertheless, the parallel use of English and the mother tongue is a practice that has been introduced in some countries to regulate language use in higher education, although its full implications are yet to be investigated (Airey and Linder, 2008).

Commonly, policymakers plan to globalize educational systems by adopting internationalization strategies. The policies through which this strategy can be achieved should be concerned with all levels of education, such as research, transfer, and governance as well as other levels (Conceição, 2020; Guo et al., 2021). Conceição (2020) argues that higher education institutions have to cope with the advancement in knowledge and preserve societal value. This can be accomplished by becoming more open to accepting changes concerning various facets, such as those of students, teaching, practices, ideas, and knowledge, which can promote global competition. At the same wavelength, several universities worldwide adopt policies that encourage the use of English in instruction, research, and the media, aiming for such internationalization to achieve, for instance, higher international rankings among, and to compete with, other universities nationally and internationally (Kuteeva and Airey, 2014). Liddicoat and Kirkpatrick (2020, p. 26) hold that the main driver for the growth of English has been the “increasing globalized role of English and an ideological positioning of English as the language of modernization and economic opportunity, supported by the neoliberal agenda of education for economic utility.”

Eno et al. (2019, p. 113) investigated the views of academics and policymakers working in the domain of education on adopting English as the sole language to be used for education. The majority of the obtained responses indicated a preference for using English as it can provide “opportunities for academic studies and professional advancement in the future.” Moreover, Bolton and Kuteeva (2012) interviewed 668 academics and 4,524 students in non-English-speaking countries about their attitudes toward using English across disciplines. The results suggest that English is opted to be the language of instruction in certain disciplines, rather than others.

Adopting an English-only policy in education has been argued to not only increase learning pressure on EFL/ESL students but also pose a status of inequity in the learning context (e.g., Valenzuela, 1999; García et al., 2008; Bartlett and García, 2011; Hamm-Rodriguez and Morales, 2021). For instance, learners may originate from different backgrounds, and thus, maintain different English proficiency levels. Therefore, pressurizing them to become proficient in English and simultaneously mastering the subjects being studied can prove problematic. Additionally, validity and reliability issues exist in terms of testing their knowledge in a foreign/second language they have not yet fully mastered, that is, they are likely to encounter difficulty in expressing their knowledge in their assessments (García et al., 2008; Menken, 2008; Jenkins and Wingate, 2015). Although such issues have been observed worldwide for decades, they remain unchanged (Turner, 2011) and efforts to adjust these policies to become more accommodating for the students have not been undertaken (Jenkins and Wingate, 2015). This probably explains the tendency of several EFL instructors to use L1 to communicate with their students. On some occasions, instructors use very little English because of the linguistic weaknesses of their students and to create equal learning opportunities in the learning context (Coleman, 2010).

Language Planning and Policies in the Saudi Context

Saudi Arabia is the largest country in the Arabian Peninsula and the Arabic language has been the mother tongue for centuries; therefore, it is the official language. In the past, Arabs were known to take pride in their native language because it is the language of their ancestors and that of the Holy Quran. This has led several researchers to describe it as a holy language for Muslims worldwide (e.g., Fishman, 2002; Liddicoat, 2012; Payne and Almansour, 2014). Hence, it is sacred to most Muslim countries, leading their communities to use it more frequently (Liddicoat, 2012). Although the Saudi constitution announced Arabic as the official language, in recent years, the government and the community have accorded high status to English, a trend influenced by the internationalization of education, commerce, and media.

English is the lingua franca among other non-Arabic speaking countries and nationals (McKay, 2018). The official documents and official signs on the streets around the country have words/statements written in two languages (Arabic and English) (Alhassan, 2017). Until recently, English was the only foreign language taught under the auspices of the Saudi Ministry of Education. At the beginning of 2021, the Minister of Education signed a decree stating that English will be taught as early as level 1 (students aged 6) in elementary schools, whereas earlier it was taught at level 4 (Almujaiwel, 2018). The introduction of English in the curricula over the last five decades has decreased gradually from the secondary level to all lower levels, except for the kindergarten level. At the higher education level, thousands of scholarships were offered to the youth in the country to obtain educational degrees from Western and other English-speaking countries. The rationale of such enthusiasm toward English is thought to be the status that it accords within the community. Consequently, the mastery of English for Saudi citizens became somewhat necessary, for example, to survive in terms of receiving certain services (e.g., at restaurants), finding a job, especially for excelling in a career.

English language policies in Saudi Arabia have received increasing attention in recent years (e.g., Payne and Almansour, 2014; Elyas and Badawood, 2016; Alnasser, 2018a,b), and the policies in Saudi Arabia’s higher education seem to be implicit in nature. For example, policies do not state that English should be the language of instruction for any discipline, yet it is the language of instruction for most subjects, including medicine, business administration, pharmacy, dentistry, and computer sciences. Moreover, no policies exist to govern language use within the country’s higher educational institutions (Almoaily and Alnasser, 2019). A large proportion of academic faculty in Saudi universities have obtained their degrees from countries where English is the first language, and this has influenced their use of English at the workplace and outside the classroom (Alnasser, 2018a), as they tend to use English with colleagues and students whose first language is Arabic. From the academic faculty perspective, when English should be used remains ambiguous, given that it is not based on either implicit, explicit, top-down, or bottom-up policies.

Materials and Methods

The context of the study is Saudi higher education English departments across the main five regions in the country. Both qualitative and quantitative data were gathered by employing an online survey and conducting semi-structured interviews with chairpersons from some of the departments. The survey included eight items (adopting a five-point Likert scale) and an open-ended section. It was built by the author on an online platform and revised by experts in the field. Then it was distributed across the English departments in the regions (by adopting the convenience sampling approach), targeting faculty with academic ranks ranging from teaching assistants to full professors. Specifically, the survey targeted the academic communities of these departments regardless of their demographic background (e.g., nationality, gender, age) in order to obtain a representative sample to address the study’s areas of investigation. Excluding those that were invalid, 213 responses were received. The analysis of the respondents’ backgrounds shows that 68,8% were females and 31.2% were males. Additionally, their academic ranks include: lecturers (44.2%), language instructors (32.7%), assistant professors (17.3%), as well as associate and full professors (5.8%). The diversity of the participants is reassuring and indicate, to some extent, that the obtained results are representative of a larger population. As for the interviews, two interview questions were directed to eight volunteer department chairs and vice-chairs to gain insights into the investigated phenomenon. The interviews were conducted in person and via telephone. They included two questions about the importance of ELPs and the occasions in which they use English for communication. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, how the data will be used, that no risks would be associated with their participation, and that their anonymity was assured.

Results

This section presents the results obtained from the survey and the interviews. The survey data were computed into SPSS and analyzed by generating frequencies of responses. Moreover, thematic analysis was used for the data obtained from the open-ended section (in the survey) and the interviews.

Survey Results: Items

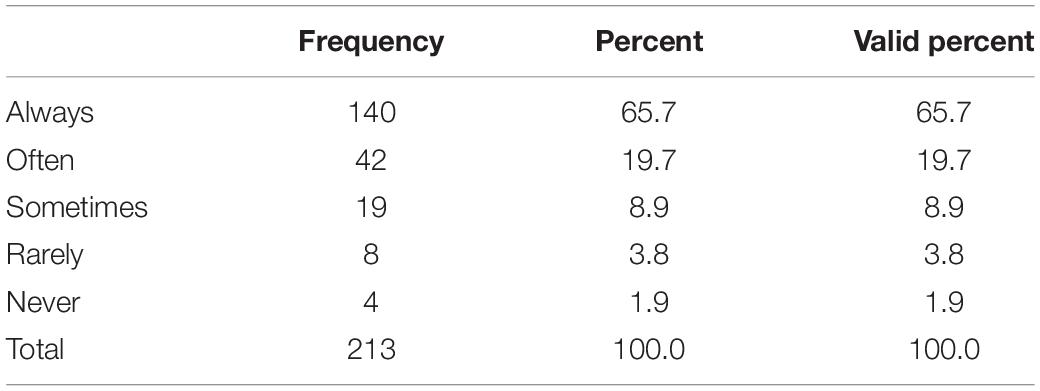

1- I use English for communication at department council meetings.

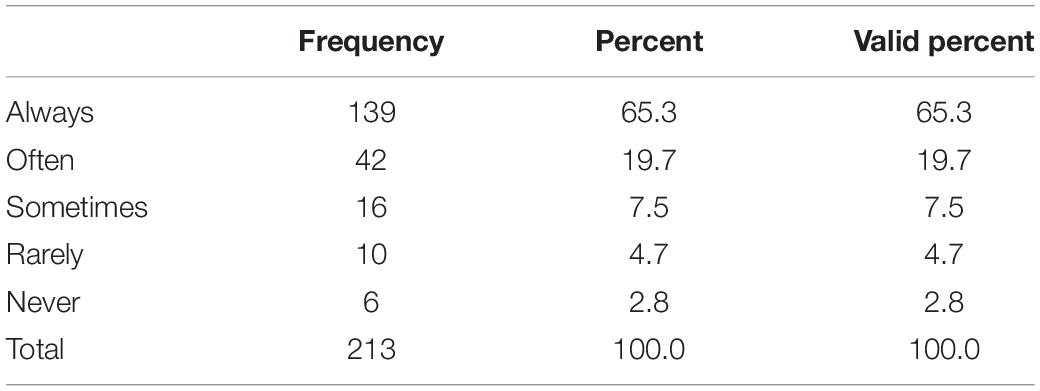

2- I use English for communication during committee meetings.

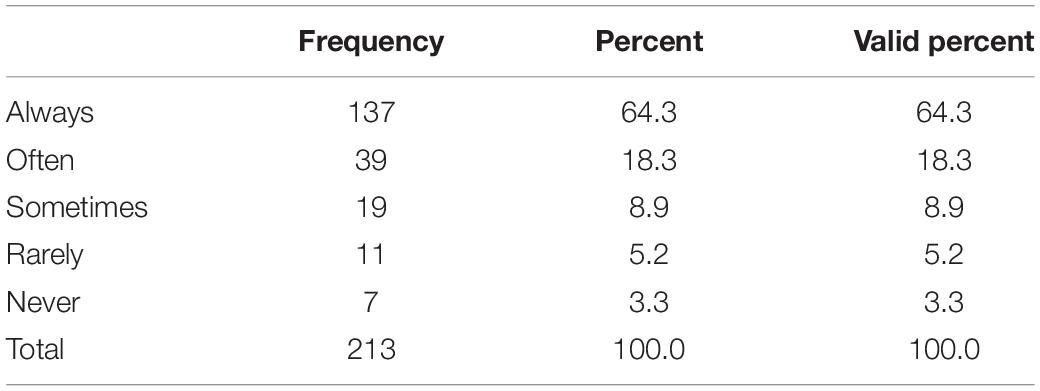

3- I deliver my verbal requests to other members in English.

Regarding the highest degree of formality at the department level, the majority of the participants (65.7%) reported that English is “always” used as the language of communication during council meetings, with another 19.7% reporting that it is “often” used in these meetings (Table 1). The two proportions (a total of 85.4%) were overwhelming when compared with small proportions of participants who reported using English “rarely,” “sometimes,” or “never” in departmental council meetings (a total of 14.6%). Similarly, Table 2 illustrates that the majority (85%) reported that English is either “always” (65.3%) or “often” (19.7%) used for communication during committee meetings, with the minority reporting that it is used “infrequently” or “never” (15%). For delivery of verbal requests, the majority (82.6%) reported that English is either “always” (64.3%) or “often” (18.3%) used, with the minority (17.4%) reporting its use as “infrequent” or “never” (Table 3). These findings clearly indicate a pattern that the majority of English departments in Saudi Arabia employ English as the medium of communication in official administrative occasions that require face-to-face encounters, and for official instruction delivery, although English is a foreign language and no official policies exist to compel its use.

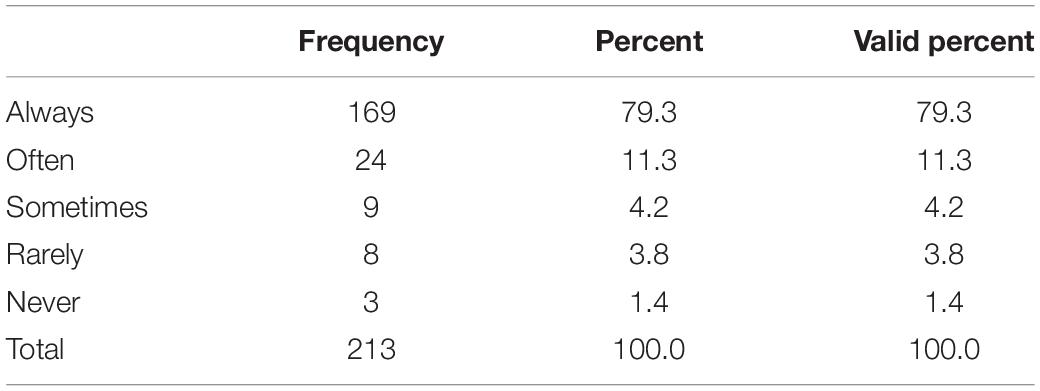

4- I use English for email correspondence with other members.

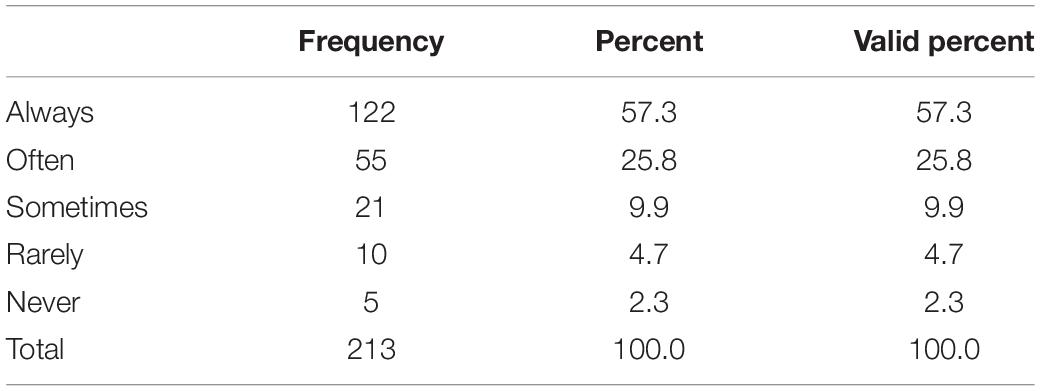

5- I use English for other types of communication (announcements, signs, posting).

In other formal situations that require no face-to-face encounters, the majority of respondents reported using English for communication. A total of 90.6% reported either “always” (79.3%) or “often” (11.3%) using English for email correspondences with other faculty, with the minority (9.4%) reporting the use of English as “infrequent” or “never” (Table 4). Similarly, the majority (83.1%) reported either “always” (57.3%) or “often” (25.8%) using English when communicating through announcements, posting instructions, news, or putting up signs, with the minority (16.9%) reporting its use “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” for such purposes (Table 5). These findings suggest that the majority of faculty members in English departments use English for communication in official, non-face-to-face situations, which is consistent with the findings discussed earlier (see Tables 1–3).

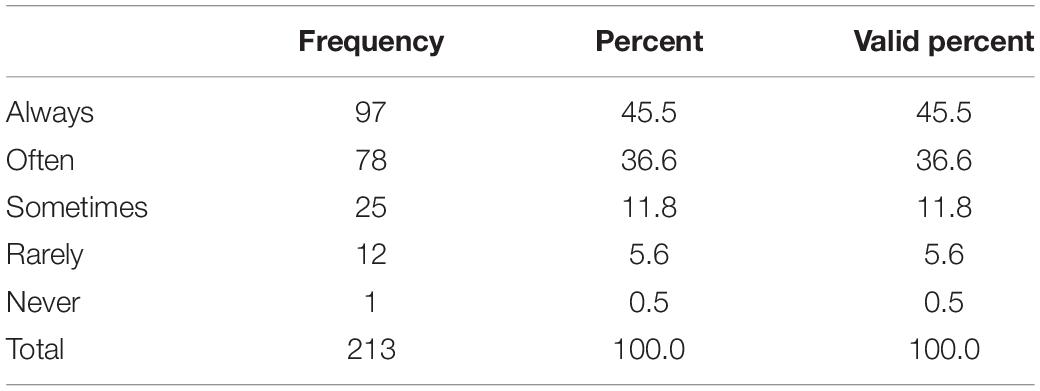

6- I use English for any type of communication during work hours.

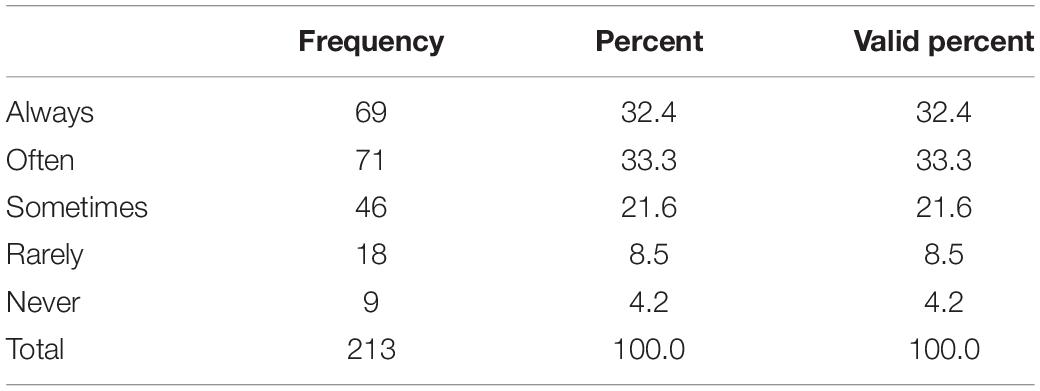

7- I use English in private (non-academic) meetings with other members.

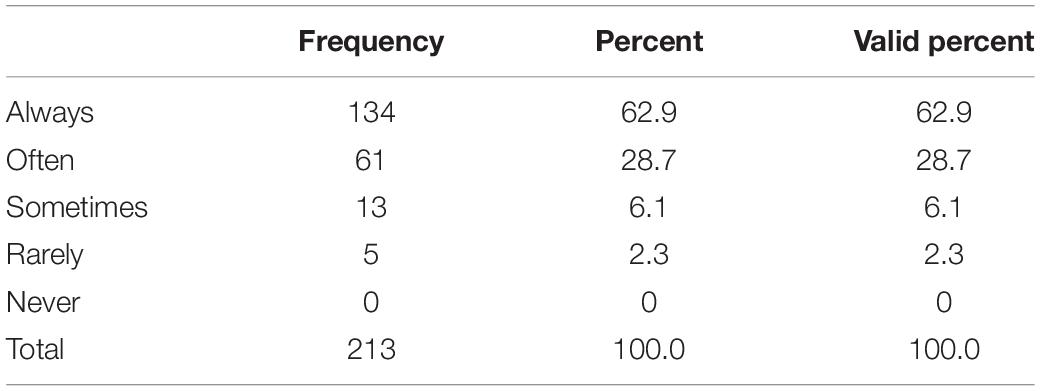

8- I use English whenever I communicate with students.

Interestingly, in less formal situations (within the domain of the department), the common use of English for communication seems to be rather frequent. In particular, the majority (82.1%) reported the use of English for other types of communication with other members during working hours as either “always” (45.5%) or “often” (36.6%), with the minority (17.9%) reporting its use as either infrequent or never in such situations (Table 6). More specifically, the majority (65.7%) reported either “always” (32.4%) or “often” (33.3%) using English in non-academic meetings with other faculty members, with a reasonable proportion (21.6%) reporting using it “sometimes,” and a smaller proportion reporting “rare” (8.5%) or “never” using it in such occasions (Table 7). Here, although the majority of the faculty members tend to use English in less formal situations, the data suggest that this tendency is used at a lower level when compared to the use of more formal situations. On a broader level, the majority (91.6%) reported that they “always” (62.9%) or “often” (28.7%) employed English as a means of communication with students outside the domain of the classroom, with the minority (8.4%) reporting its use as “infrequent” or “never” in these situations (Table 8). The responses to this item, in particular, have the highest majority and lowest minority demonstrating the skewness of responses toward the use of English in student communication at the department level, possibly suggesting their keenness to offer students opportunities to practice English.

Open-Ended Section

In this section, one question was provided to all participants with an opportunity to freely express their views, and interestingly, a considerable proportion provided insightful remarks.

- If you think English should be used at the department level, explain why.

In response to this item, 65 participants expressed their views. A considerable proportion (26 participants) reported that English should be used to improve proficiency levels. Here, more frequent use of English can not only encourage the development of learners’ language skills but also help the faculty maintain their high level of linguistic proficiency, especially in a context (i.e., the Saudi context) that offers very limited opportunities for “formal” English language practice. Another 18 participants reported that English must be used whenever a non-Arabic speaking faculty is present. In this regard, 6 of the 18 participants explained that using English at all times within the domain of the department can allow for better communication, a notion that is accepted in departments that include members who can only communicate with Saudi faculty through the English language. A total of 21 participants suggested that English should become the only language of communication within the domain of the department, simply because it is the department’s area of specialization. These findings may suggest that Saudi faculty are very likely to accept internationalizing their academic domain along with enforcing top-down ELPs (including English-only policies), as suggested by the university.

Interview Results

1- How important do you think having ELPs is?

All eight interviewees deemed having ELPs important and provided further explanations for maintaining this view. They explained enforcing ELPs in all Saudi English departments could ensure consistency regarding when to use English. For instance, one interviewee stated that “I have seen colleagues use English, Arabic and Urdu in joint meetings, and this can be quite disturbing and unprofessional. Thus, I believe we need to set rules to govern language use during official encounters.” Furthermore, the interviewees clarified that having such policies can promote more frequent use of English in a context that is dominated by Arabic (L1), create a working environment that is suitable for everyone (especially non-Arabic speakers), provide a learning opportunity that is suitable for EFL learners and offer them more opportunities for utilizing the language, and help maintain faculty’s English language proficiency. As an example, one interviewee explained that “in Saudi Arabia we lack the sufficient opportunities to practice English with other professionals. In fact, I am afraid that my linguistic proficiency is deteriorating overtime, and there is a need to adopt mechanisms to sustain our linguistic proficiency.” The findings here are in line with findings from the survey and indicate that all interviewees see view the existence of ELPs as important and can positively impact the educational setting.

2- On which occasions do you use English at the department level?

The responses of the eight interviewees were of two types. The first category comprises those who have a high tendency to use English in formal as well as informal situations, and this type forms the majority of the interviewees. Five interviewees explained that English is used in almost every meeting and every possible situation, such as in social media communications, in-department announcements, communicating with non-Arabic speaking faculty, contacting and communicating with students and other faculty members, council and committee meetings, and during office hours. These situations were not limited to official or academic encounters only; thus, these interviewees appeared to be keen on using English as often as possible. One interviewee explained that “I am an English major and have studied in the United States for years, and now I am researching and teaching English language. So English became part of my career, and I should use it in every possible situation.”

By contrast, the second category included those who reported limiting their use of English to situations that are considered “official” and “academic,” which were reported by a smaller proportion. Three interviewees stated using English in academic and official situations only, such as when conducting official departmental meetings, delivering presentations, and/or during seminars. The interview findings are again aligned with those obtained from the survey.

Discussion and Conclusion

The literature has already established that academia in Saudi institutions does not have formal ELPs (e.g., Almoaily and Alnasser, 2019). Therefore, existing policies are implicit in nature and are practiced based on personal preferences. In this paper, the term “self-ELPs” is introduced to refer to implicit ungoverned policies practiced by faculty members. The findings of the study revealed that such policies in the Saudi context seem to commonly emerge in formal and informal situations, where English is used for communication in council and committee meetings, and communicating with fellow faculty members in private non-formal discussions. This was accepted by the majority of faculty members in the Saudi English department, suggesting their desire for more exposure to and practice with English. Here, their affiliation to English departments and the field of specialty can be speculated to have led to the formation of a perception that English should become somewhat “the official language” in their academic domain.

Regarding communication with students (inside and outside the domain of the classroom), a higher frequency of English use was observed in the findings. The results suggest that this can establish further learning situations and promote active learning environments. Although such practice can be widely accepted by EFL students (Bolton and Kuteeva, 2012) and can be rewarding to most of them, few may not find it as rewarding as it was hoped for, and therefore, refrain from engagement (especially linguistically afflicted students). Several researchers have argued against adopting such policies as they can pose a status of inequity among students (e.g., Valenzuela, 1999; García et al., 2008; Bartlett and García, 2011; Hamm-Rodriguez and Morales, 2021). The need to offer students more accommodating contexts is highly stressed (Jenkins and Wingate, 2015).

The participants of the study mostly advocated more frequent English use at the department level, as it may have several positive influences on faculty as well as their students, such as creating a professional, educational environment that may stimulate productivity and further engagement. Although formal ELPs do not exist and Arabic is the official and the first language, English seems to have replaced Arabic on most occasions with no concerns being reported against such an overwhelming use. In other words, the overall findings obtained from the survey and interviews clearly indicate that the vast majority of faculty in Saudi Arabia opt for practices/policies involving more frequent use of English. This suggests that Saudi English departments not only have no concerns over the dominance of English (L2) over Arabic (L1) but also promote such dominance. Therefore, the concerns raised by Khalaf (2002, 2005), and Al-Issa and Dahan (2011) do not apply to the context of this study.

Self-ELPs reported in this study projected the passion of the faculty in Saudi English departments for the English language and their desire to push for further dominance of English. Hence, it is concluded that such faculty members are ready for the introduction of formal, written ELPs that may include English-only policies at the department level. This can create an inner circle community that resembles the ESL context. The need for language policies in the Saudi context is necessary to mitigate the complications that may arise in the future (Tickoo, 2006; Alhendi, 2019; Adriano et al., 2021). The survey results reflected small proportions of participants who do not opt for English use outside the domain of the classroom, which can lead to disagreement between them and the other proportion who opt for more frequent English use; thus, introducing official ELPs can serve as a pre-emptive solution to any disagreement that may arise in this regard.

Recently, Saudi universities have revised their strategic plans to dedicate more attention to self-funding rather than government funding. This forces these universities to invest in educational opportunities, such as the internationalizing academic program at the bachelor, master, and PhD levels. To achieve such goals, the existence of formal ELPs is necessary to create a more accommodating and attractive setting for international students (Eno et al., 2019; Liddicoat and Kirkpatrick, 2020). Their existence can also attract more prominent academics from around the world to seek jobs in Saudi universities, which can improve the quality of teaching, research, and other educational practices.

Finally, the conclusions of the study reassure policymakers in Saudi Arabia that delegating ELPs to English departments and internationalizing this context is welcomed and “awaited.” This can be the starting point for the Saudi educational system to open up to the world and invite international scholars and students on a large scale. Nonetheless, it is recommended that policymakers and researchers address the issue of avoidance of the Saudi faculty to use English at the department level, as this may slightly hinder the process of enforcing official ELPs. In terms of the limitations of the current study, mainly it was not possible to explore the views of the policymakers in the country on how self-ELPs may contribute to facilitating the internationalizing of the higher education sector. Additionally, owing to the time constraint the researcher had, it was not possible to employ focused groups with faculty members from different Saudi English departments to explore their perspectives on the mechanisms by which internationalization of the Saudi higher education can be achieved. Therefore, future research may shed light on these two points, and the findings are expected to contribute to the field of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by King Saud University Research Ethical Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer SA declared a shared affiliation with the author to the handling editor at the time of review.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adriano, M. N. I., Franco, N. T., and Estrella, E. A. (2021). Language-in-education policies and stakeholders’ perception of the current MTB-MLE policy in an ASEAN country. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 44, 84–99.

Airey, J., and Linder, C. (2008). Bilingual scientific literacy? The use of English in Swedish university science programmes. Nordic J. Engl. Stud. 7, 145–161. doi: 10.35360/njes.105

Alhassan, A. (2017). Teaching English as an international/lingua franca or mainstream standard language: unheard voices from the classroom. Arab World Engl. J. 8, 448–458. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol8no3.29

Alhendi, O. (2019). Language policy and economics: Does English language accelerate the wheel of development in the economies or not? A review. The Annals of the University of Oradea. Econ. Sci. 2, 366–379.

Al-Issa, A., and Dahan, L. (2011). Global English and Arabic: Issues of Language Culture and Identity. Oxford: Peter Lang. doi: 10.3726/978-3-0353-0120-5

Almoaily, M., and Alnasser, S. M. N. (2019). Current English language policies in Saudi Arabian higher education English departments: a study beyond the domain of the classroom. J. Arts 31, 35–47. doi: 10.33948/1300-031-002-007

Almujaiwel, S. (2018). Culture and interculture in Saudi EFL textbooks: a corpus-based analysis. J. Asia TEFL 15, 414–428. doi: 10.18823/asiatefl.2018.15.2.10.414

Alnasser, S. M. N. (2018a). Gender differences in beliefs about English language policies (ELPs): the case of Saudi higher education English departments. Int. J. Educ. Liter. Stud. 6, 111–118. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.6n.2p.111

Alnasser, S. M. N. (2018b). Investigating English language policies in Saudi higher education English departments: staff members’ beliefs. Linguist. Lit. Stud. 6, 157–168. doi: 10.13189/lls.2018.060402

Badry, F., and Willoughby, J. (2016). “Higher education revolutions: short-term success versus long-term viability?,” in Higher Education Revolutions in the Gulf, eds F. Badry and J. Willoughby (New York, NY: Routledge), 204–236. doi: 10.4324/9780203796139

Bartlett, L., and García, O. (2011). Additive Schooling in Subtractive Times: Bilingual Education and Dominican Immigration Youth in the Heights. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv16b78cp

Benson, C. (2004). The Importance of Mother Tongue-based Schooling for Educational Quality. Background Paper Prepared for the ‘Education for All’ Global Monitoring Report 2005. The Quality Imperative. Paris: UNESCO.

Bolton, K., and Kuteeva, M. (2012). English as an academic language at a Swedish university: parallel language use and the ‘threat’ of English. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 33, 429–447.

Coleman, H. (2010). Teaching and Learning in Pakistan: The Role of Language in Education. Islamabad: The British Council.

Coleman, H., and Capstick, T. (2012). Language in Education in Pakistan: Recommendations for Policy and Practice. Islamabad: British Council.

Coleman, J. A. (2006). English-medium teaching in European higher education. Lang. Teach. 39, 1–14. doi: 10.1017/S026144480600320X

Conceição, M. C. (2020). Language policies and internationalization of higher education. Eur. J. High. Educ. 10, 231–240. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2020.1778500

Costa, J., De Korne, H., and Lane, P. (2018). “Standardising minority languages: reinventing peripheral languages in the 21st century,” in Standardizing Minority Languages, eds P. Lane, J. Costa, and H. De Korne (London: Routledge), 1–23.

Deumert, A. (2005). “Language planning and policy,” in Introducing Sociolinguistics, eds R. Meshtrie, J. Swann, A. Deumert, and W. L. Leap (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 384–418.

Ek, A. C., Ideland, M., Jönsson, S., and Malmberg, C. (2013). The tension between marketisation and academisation in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 38, 1305–1318. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.619656

Elyas, T., and Badawood, O. (2016). English language educational policy in Saudi Arabia post 21st century: enacted curriculum, identity, and modernisation: a critical discourse analysis approach. FIRE 3, 70–81. doi: 10.18275/fire201603031093

Eno, M. A., Ahad, A. M., and Shafat, A. (2019). Perceptions of academic administrators and policymakers on ESL/EFL education. J. Somali Stud. 6, 93–119. doi: 10.31920/2056-5682/2019/V6n1a4

Fishman, J. A. (2002). Holy languages in the context of societal bilingualism. Contribut. Sociol. Lang. 87, 15–24. doi: 10.1515/9783110852004.15

García, O., Kleifgen, J. A., and Falchi, L. (2008). From English language learners to emergent bilinguals. Equity Matters Res. Rev. 1, 1–61.

Gunnarsson, B. L. (2001). “Swedish, English, French or German—The language situation at Swedish universities,” in The Dominance of English as a Language of Science: Effects on other Languages and Language Communities, ed. U. Ammon (Berlin, NY: Mouton de Gruyter), 229–316.

Guo, Y., Guo, S., Yochim, L., and Liu, X. (2021). Internationalization of Chinese Higher education: Is it westernalisation? J. Stud. Int. Educ. 1–18. doi: 10.1177/1028315321990745

Hamm-Rodriguez, M., and Morales, A. S. (2021). (Re)Producing insecurity for Puerto Rican students in Florida schools: a raciolinguistic perspective on English-only policies. Centro J. 33, 112–132.

Jenkins, J., and Wingate, U. (2015). Staff and student perceptions of English language policies and practices in ‘international’ universities: a UK case study. High. Educ. Rev. 47, 47–73.

Jernudd, B., and Gupta, J. (1971). “Towards a theory of language planning,” in Can Language be Planned? Sociolinguistic Theory and Practice for Developing Nations, eds J. Rubin and B. Jernudd (Hawaii: The University Press of Hawaii), 195–215.

Kachru, B. B. (1986). The Alchemy of English and the Spread, Functions and Models of Non-Native Englishes. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Kaplan, R. B., and Baldauf, R. B. (1997). Language Planning: From Practice to Theory. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Karam, F. (1974). “Toward a definition of language planning,” in Advances in Language Planning, ed. J. A. Fishman (The Hague: Mouton), 103–124. doi: 10.1515/9783111583600.103

Khalaf, S. (2002). Globalization and heritage revival in the Gulf: an anthropological look at Dubai Heritage Village. Soc. Affairs 19, 13–42.

Khalaf, S. (2005). National dress and the construction of Emirati cultural identity. J. Hum. Sci. 11, 229–267.

Kuteeva, M., and Airey, J. (2014). Disciplinary differences in the use of English in higher education: reflections on recent language policy developments. High. Educ. 67, 533–549. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9660-6

Liddicoat, A. J. (2012). Language planning as an element of religious practice. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 13, 121–144. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2012.686437

Liddicoat, A. J., and Kirkpatrick, A. (2020). Dimensions of language education policy in Asia. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 30, 7–33. doi: 10.1075/japc.00043.kir

McKay, S. L. (2018). English as an international language: What it is and what it means for pedagogy. RELC J. 49, 9–23. doi: 10.1177/0033688217738817

Menken, K. (2008). English Learners Left Behind: Standardized Testing as Language Policy. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781853599996

Payne, M., and Almansour, M. (2014). Foreign language planning in Saudi Arabia: beyond English. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 15, 327–342. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2014.915461

Peltokorpi, V., and Vaara, E. (2017). “Language policies and practices in wholly owned foreign subsidiaries: a recontextualization perspective,” in Language in International Business. JIBS Special Collections, eds M. Y. Brannen and T. Mughan (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42745-4_5

Sperduti, V. (2017). Internationalization as Westernization in higher education. Comp. Int. Educ. 9, 9–12.

Tauli, V. (1974). “The theory of language planning,” in Advances in Language Planning, ed. J. A. Fishman (The Hague: Mouton), 49–67. doi: 10.1515/9783111583600.49

Tickoo, M. L. (2006). Language in education. World Engl. 25, 167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.0083-2919.2006.00454.x

Tikly, L. (2004). Education and the new imperialism. Comp. Educ. 40, 173–198. doi: 10.1080/0305006042000231347

Trudell, B. (2009). Local-language literacy and sustainable development in Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 29, 73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.07.002

Turner, J. (2011). Language in the Academy: Cultural Reflexivity and Intercultural Dynamics. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781847693235

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive Schooling: U.S.-Mexican Youth and the Politics of Caring. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

Wachter, B., and Maiworm, F. (2008). English-Taught Programmes in European Higher Education: The Picture in 2007. ACA Papers on Cooperation in Education. Bonn: Lemmens.

Keywords: EFL, English language policies, higher education, language policy and planning, language use, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Alnasser SMN (2022) Exploring English as a Foreign Language Instructors’ Self-Derived English Language Policies at Higher Education Level: A Case Study in the Saudi Context. Front. Educ. 7:865791. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.865791

Received: 30 January 2022; Accepted: 28 March 2022;

Published: 28 April 2022.

Edited by:

Anastassia Zabrodskaja, Tallinn University, EstoniaReviewed by:

Jamal Kaid Mohammed Ali, University of Bisha, Saudi ArabiaWagdi Bin-Hady, Hadhramout University, Yemen

Hamza Alshenqeeti, Taibah University, Saudi Arabia

Sultan Almujaiwel, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2022 Alnasser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suliman M. N. Alnasser, c21hbG5hc3NlckBrc3UuZWR1LnNh

Suliman M. N. Alnasser

Suliman M. N. Alnasser