95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 13 April 2022

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.865222

This article is part of the Research Topic Teaching History in the Era of Globalization: Epistemological and Methodological Challenges View all 16 articles

This study investigates the difficulties pre-service history teachers face in understanding and implementing a history curriculum focused on historical reasoning. Based on the general hypothesis of beliefs exerting a direct influence on teachers’ actions, this phenomenographic study provides a qualitative analysis of the epistemic and learning/teaching conceptions on which pre-service teachers base their reflections and decisions when they have to produce a teaching plan for a specific situation, taking n = 72 pre-service teachers from the Master’s Degree in Teaching in Secondary Education at the University of Zaragoza (specialty Geography and History) as statistical sample. The outcome of the first phases of the analysis was a new theoretical reference framework that innovated by simultaneously analyzing epistemic and educational conceptions. On the one hand, the analysis results include a considerable number of pre-service teachers who use epistemic beliefs identifying history and the past when addressing the curriculum. On the other, none of them, not even those with advanced epistemic beliefs, think about the curriculum in terms of an inquiry-based approach to historical problems, and, therefore, they display a transmissive–reproductive conception of history instruction. Consequently, the main contribution is observation of a twofold threshold that pre-service teachers must cross to understand and accept an interpretive history curriculum: they must overcome the identification between past and history and instead immerse themselves in the necessarily interpretive nature of any history; and they must stop viewing learning as knowledge internalization and reproduction and, instead, embrace a conception of learning as inquiry and reasoning.

One of the main objectives of training pre-service secondary-school history teachers is exploring alternatives to the traditional encyclopedic curriculum based on explaining and reproducing historical data. For decades now, research has proposed another curriculum focused on developing historical literacy, in which students investigate historical problems by developing competence for historical interpretation and reasoning. However, in general and repeatedly, we observe that pre-service teachers find it extremely hard to first understand and then apply this type of interpretive curriculum. This difficulty has been related to both epistemic beliefs on the nature of history and beliefs on what learning and teaching means. Based on this general hypothesis, this study analyzes these beliefs at the start of the specific education program for history graduates, which lasts one academic year and is compulsory in Spain to become a secondary-school teacher. The study presented here is part of a more overarching project whose purpose is a longitudinal monitoring of these pre-service teachers’ beliefs throughout their entire year of training. The ultimate aim is to improve the program by having a more specific impact on these pre-service teachers’ beliefs.

On the one hand, there is a relatively consolidated line of research on the determining role of epistemic beliefs in teachers’ decisions that has been extended to the specific area of history instruction in some relevant studies. On the other, there is now classic research on teachers’ beliefs concerning the curriculum, teaching, and learning, which in the case of history has essentially been explored in studies focused on the difficulties involved in implementing inquiry-based learning—essential for developing the capacity for historical thinking—in the classroom. Some recent studies can be found in the Spanish context, such as Colomer et al. (2021), Parra-Monserrat et al. (2021), and Gómez-Carrasco et al. (2022). However, the pioneering method of this research has complicated the possibility of contrasting its results with those of previous studies. Although both types of beliefs have often generically been linked together, the complexity of this relationship has barely been analyzed in the specific case of just one discipline, particularly history. This study simultaneously analyzes both types of beliefs in an attempt to shed some light on how they mutually determine or condition each other.

An exercise of reflection and decision making on the teaching of the First World War is proposed to analyze these beliefs with the aim of bringing to the surface the pre-service teachers often implicit system of beliefs—rather than their theoretical historiographical knowledge—which they use to work effectively when thinking about the curriculum. After a first phase of exploratory analysis based on existing models, an ad hoc theoretical framework of analysis combining epistemic and educational beliefs is proposed; its application will result in a series of categories showing the belief system Spanish pre-service teachers employ to think about the history curriculum at the start of their teacher training.

The history curriculum is always subject to controversy in most contemporary societies (Berg and Christou, 2020). In these history wars, the focus of the debate is not so much—or not only—which version of the past to teach, but whether a certain account (typically a standardized national account serving as a social cohesion tool) should be taught, or whether, in contrast, students should learn to inquire and interpret as a historian does (critical analysis of evidence and discourses, exploration of change processes, analysis of the tapestry of causes of events, inquiry into the diversity of perspectives supporting decisions and human actions, and so on). This is not a debate between “knowledge” and “capacities,” or “content” and “method” as some authors have suggested (Seixas, 1999; Fordham, 2012), but the contrast between school history understood as learning the “true facts” of a single account and a curriculum rooted in the historical discipline, its essential problems, methods, and concepts, its critical questioning, and its necessary diversity of perspectives.

Dunn (2010) talks about “two world histories”: history “A,” exploring how to take “debates over evidence, interpretation” (p. 184) to the classroom; and history “B,” in which the debate, now political, focuses on which (single) history must be explained depending on “national values and purpose” (p. 185). Wansink (2017) summarizes it as the confrontation between two forms of understanding history, “factual” against “interpretive.” It is a closed conception of history that has to be learned against a problematized conception in which students come across open historical issues they must debate and construct interpretations for. In other words, knowledge of the “facts” that every resident (of this country) should know compared with what Lee (2005) defined as “historical literacy.”

In our opinion, the debate between these two forms of conceiving history instruction must be present at the core of any training of pre-service history teachers. We have found that the starting point for the majority of the pre-service teachers studying the Master’s Degree in Teaching in Secondary Education at the University of Zaragoza is their direct experience in the classroom of that “great tradition” of history instruction, that account with no visible author that descends on students as the truth of past events. Consequently, the program tries to make them critically consider other curriculum possibilities, particularly what we synthetically call in this study an interpretive history curriculum.

The issue that has led to this study is the systematic observation of how hard it is for these pre-service teachers to think about secondary-school history within this curricular approach, even though they deem it fascinating and realize it is supported by research. They often do not completely understand it, or they do not accept it as possible in practice. That is particularly paradoxical when we have found that almost 90% of them have an overly critical view of the traditional history curriculum, which they experienced when they were at school (Paricio and García-Ceballos, in press). If they think this encyclopedic curriculum accumulating data and facts is boring and does not make sense, why is it so hard for them to be open to an alternative?

Barton and Levstik (2010, p. 35) asked the question: “Why don’t more history teachers engage students in interpretation?” After decades of research, argument, and training in this “new history,” a considerable number of teachers opt to continue telling their students a single account of events that subsequently the students repeat in their work and tests, even when, as these authors point out, many of them are excellent teachers, engaged with their pupils and devoted to preparing their curricula and activities. In their case study on how brilliant pre-service teachers implemented what they had learned in their training program, Van Hover and Yeager (2004) found that, once in the classroom with their students, they seemed to forget the interpretive history they had explored on their course and, instead, concentrated on “covering” the textbook. They describe this problem as “the “disconnect” that may take place between what pre-service history teachers learn in their social studies methods courses and what they actually encounter and do in the “real world” of the history classroom” (p. 19). Along the same lines, Mayer (2006) talks about “resistance” to teaching historical reasoning and interpretation despite decades of teacher training, research, and even laws dictating its inclusion in the curriculum.

Therefore, it is not a specific problem of our pre-service teachers, but rather a difficulty observed in general. Criticism of this traditional curriculum focused on reproducing a single account is understood and even shared by the majority. As Cornbleth (2010) mentioned, no one is opposed to seeking a more significant and valuable history instruction, yet this search occurs relatively infrequently. Why? What prevents it?

Prior literature has formulated a series of hypotheses on the origin and nature of this difficulty in what is still an open research process. The first and most obvious is that a considerable number of teachers has a limited knowledge of historical inquiry and interpretation processes or an insufficient theory of history teaching and learning (Yeager and Davis, 1996; Seixas, 1998). As solving these shortfalls in historical or educational knowledge is usually found at the heart of history teacher training, we could consider it the predominant implicit or explicit theory. Barton and Levstik (2010), however, question this hypothesis given the evidence that even when teachers have a good knowledge of history as a discipline and know appropriate educational approaches and practices, they do not necessarily apply this type of curriculum in the classroom: “In study after study, what teachers know has little impact on what they do. In fact, sometimes teachers are well aware of this mismatch. Why is this? If teachers know that history is interpretive and involves multiple perspectives, and if they know how to engage students in the process, why don’t they do so?” (Barton and Levstik, 2010, p. 37–38).

These same authors suggest a second hypothesis: this type of curricular approach would endanger the two priority objectives in the classroom, namely, keeping control of the class and covering the syllabus. Van Hover and Yeager (2004) had already suggested the issue of classroom control as an objective that influences teachers’ decisions and prevents the practical application of an interpretive curriculum. In addition to control, they consider two other key factors: the importance of context (influenced by the approaches of more experienced colleagues and the school’s curricular culture) and the belief that students are unable to perform these inquiries.

The crucial aspect we observed, without belittling the importance these other factors may have, is the generalized feeling of being obliged to teach the syllabus, usually expressed as the need to “provide a grounding of fundamental knowledge.” Barton and Levstik (2010) give a perfect explanation for the North American context of what we have observed in the Spanish context:

Everything else—primary sources, multiple perspectives, student interpretation—is extra, and there is rarely time for extras. Learning how to construct historical accounts from evidence might be nice, but it will almost always take a back seat to coverage of textbook or curriculum content, because that is what many people think history teaching is all about (Barton and Levstik, 2010, p. 38).

If our pre-service history teachers actually feel that their first obligation is to teach the facts in the textbook, we want to know where this idea comes from and how deep-seated this feeling is because the truth is that “knowing the facts” is virtually endless, and everything else will always be reduced to mere desires or isolated experiences, at best.

The general objective of this research is to identify and characterize the beliefs on which pre-service history teachers base their conception of the curriculum and instruction of this subject. The focus is on their epistemic conceptions of history and their beliefs about teaching and learning history, on the now widely accepted hypothesis that it is not the knowledge but the beliefs teachers hold that influence the way they act (Pajares, 1992; Richardson, 1996; Norton et al., 2005) and that understanding these beliefs is crucial to designing effective teacher training (Kember, 1997).

The starting premise is that most of the beliefs and conceptions we employ as teachers can be implicit (Pozo, 2001, 2003). Formed through direct experience, without critical reflection of any kind, they have the force and the rootedness of what is seen as simply “the way it is.” Our pre-service teachers have experienced a certain way of understanding history and the history curriculum as students themselves and this conception has become emblazoned in their minds. For that reason, although we also ask them about their explicit ideas on history instruction, we are especially interested in the epistemic and educational beliefs they actually deploy when they tackle the specific task of designing the instruction of a particular historical subject for their future students. We understand there could be significant dissonance between what the pre-service teachers “know” declaratively (on historiography or teaching methods, for example) and the beliefs they employ to actually conceive and implement their teaching (Van Hover and Yeager, 2004).

The entire study is structured around a single question based on the abovementioned statement by Barton and Levstik (2010, p. 38), “Coverage of textbook or curriculum content. that is what many people think history teaching is all about.” Is this statement true for our pre-service teachers? What do our pre-service teachers believe should be learned in secondary-school history subjects? And, if applicable, what makes them think their first obligation is to finish that “syllabus”? What are the arguments or beliefs behind that decision? Is it really a decision or simply something that is taken for granted?

This is a relevant issue since, if a deep-seated belief exists that this set of contents defined in the “syllabus” of the textbook is compulsory, all the efforts made during the training program to introduce the development of historical thinking to guide the curriculum will collide with that glass barrier repeatedly. As Barton and Levstik pointed out, these pre-service teachers can end up thinking that historical reasoning activities are a fascinating extra, but still just an extra there is rarely any time for. Investigating this issue involves exploring the epistemic and learning beliefs behind this form of thinking about the curriculum.

Here we need to make two points. Firstly, we believe it is possible that these pre-service history teachers have parallel conceptions: a more advanced epistemic conception for the “professional” history practiced by historians, and a far more simplistic and naive conception for school history, backed by their own experience. Secondly, it is also possible that explicit conceptions arising from their study of historiography overlap with implicit conceptions rooted in their experience that come to the surface naturally when they have to make a decision about the school curriculum. The possibility of having several simultaneous conceptions surfacing in different contexts and with varying degrees of predominance has already been consistently demonstrated (Smith et al., 1994; Ohlsson, 2009; Shtulman, 2009; Nadelson et al., 2018). In this case, although the explicit conception to a direct question can be learned while studying contemporary historiography, the operational conception—the one actually used to make decisions about the curriculum—could be a naive conception produced implicitly during the school experience and activated when thinking about what should be learned at secondary school. In other words, using the general epistemic model by Baxter-Magolda (2002) as a reference, we can position ourselves irreflexively in an “absolutist knowing” conception when talking about school history and, surprisingly, think about history as “contextual knowing” when positioning ourselves in the role of historians. In the first case, the curriculum would be decided under the “assumption that knowledge is certain and people designated as authorities know the truth” (p. 93) and, in the second, it would be assumed “that knowledge is constructed in a context” (p. 96); therefore, (a) several valid interpretations can be made of the same past based on different perspectives and contexts, and (b) we need to know how to critically analyze the validity of every historical “construction.”

This twofold play between explicit and implicit beliefs and beliefs associated with professional history and school history poses interesting problems: Could they be rejecting the traditional curriculum but not be capable of thinking outside the historical canon imposed by tradition? And, if that were the case, how can this contradiction be resolved? It also poses the methodological problem of direct questions or questionnaires on epistemic or educational beliefs proving insufficient. For that reason, as we will see below, we have chosen to complement the direct questions with a practical exercise in which the participants have to reflect and make decisions that we will later analyze.

Our research falls into an interpretive paradigm and its method is set in a framework of phenomenographic studies of learning and teaching approaches, which were pioneeringly begun by the famous Gothenburg group (Marton, 1986). The qualitative research analyzes trough categorization the reflections and decisions of pre-service teachers when answering the questions and problems we posed. This study conducts an exhaustive analysis and coding of the responses of the n = 72 pre-service teachers of the Master’s Degree in Teaching in Secondary Education at the University of Zaragoza at the start of their course and in the subject Curriculum and Instructional Design, the first they take in the master’s degree within their specialty during the academic year 2021–2022. Even though a total of N = 109 pre-service teachers attend to the Master’s Degree specialty in Geography and History—having previously get a Degree in History, Art History or Geography—, only the n = 72 who have specifically studied a History Degree have been selected as statistical sample.

To explore their epistemic and curricular conceptions, in a first conceptual phase pre-service teachers were asked two direct questions on the purpose of history in secondary education and their personal experience of it. Next, in an instructional phase, they were given the specific exercise of devising a teaching unit on the First World War. The aim was to capture both their explicit general ideas on the history curriculum and the conceptions from which they actually operate when making decisions about this curriculum. They were asked to reflect on the curricular meaning that could be given to the unit and analyze both the official curricular document and one of the most usual textbooks. They were then asked to talk about whether they would include the contents of the textbook in their curriculum or whether they would opt for something completely different, and to detail what they would include. They were also given several primary sources that differed in tone and subject and they were asked if they would integrate them into the unit and how.

Their responses were analyzed qualitatively and categorized from both an epistemological and an educational perspective. The first categorization took as a reference—tentatively as open hypotheses—the general epistemic models by Kuhn (1991; Kuhn et al., 2000, Baxter-Magolda, 2002) and Kuhn and Weinstock (2002), and the specific history models by Jenkins and Munslow (2004), Maggioni et al. (2009), VanSledright and Reddy (2014), and VanSledright and Maggioni (2016). The models by Kember (1997), Trigwell and Prosser (2004), Trigwell et al. (2005), and Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne (2008) were the starting point—also tentatively—for the curricular categorization. The responses were analyzed as a whole, in an attempt to holistically clarify each student’s position, including possible incoherencies. The analysis was conducted in parallel by the authors of this paper, and any possible inconsistency was subsequently contrasted and solved (Figure 1).

The texts containing the pre-service teachers’ reflections and decisions were subject to a series of analyses until the information was saturated. A first tentative categorization was made by projecting the epistemic and curricular models described above and studying whether any of them could consistently account for the belief system from which our pre-service teachers reflected and made their decisions. To our surprise, the models could only very partially capture these beliefs and they never sufficed to describe them and establish categories among them.

The common ground between the abovementioned models on teaching conceptions by Kember (1997) and Trigwell and Prosser (2004) is that they establish two major types that function as categorización poles: teaching to transmit knowledge (focused on contents and instruction) as opposed to teaching to facilitate students’ conceptual change. In the analysis conducted, the distinction between these two categories is highly relevant but only slightly determining, to the extent that no case was found that we could categorize as focused on students and on their conceptual change.

Concerning epistemic conceptions, the model by VanSledright and Maggioni (2016) distinguishes between copier—“the past happened as it actually happened and history simply narrates it” (p. 266)—, subjectivist—“history is whatever we knowers make it to be” (p. 267)—and criticalist—“the balance between the objects of understanding and the subject… judgment is constrained and refined by the objects and the community in which they converse about the past” (p. 267). Although the vast majority of our pre-service teachers take it for granted that their task will be to offer a single version of the past in the classroom with no hesitation about what kind of truth they are offering about what happened, it is hard to categorize them as copiers since many express their willingness to provide their students with comprehensive interpretations that give meaning to the facts and extend beyond the simple chronicle of them. They are even less likely to fall into the subjectivist category, since none of our pre-service teachers thinks all opinions are valid in history. As very few of them talk about exploring with their students the process of producing historical accounts based on sources and evidence, the criticalist category would only group a small number of cases. The result is that, except for a few that could fall into the categories of copier (10%) or criticalist (7%), most of our pre-service teachers do not seem to fit into any of the three model categories (83%).

Nor does the almost generalized insistence on engaging in a sense-making interpretation of the present fit with the emphasis on factual objectivity that characterizes the category of reconstructionist proposed by Jenkins and Munslow (2004) (“narrative as simply the vehicle for the truth of the past because the image in the narrative refers (corresponds) to the reality of the past”). Their constructionist category, viewing history as a process that tries to uncover the structures and processes behind facts, seems to fit far better with the majority’s ideas: “the key constructionist idea that historians deploy concepts and arguments in order to make generalizations, but not ones that are absolute.” This emphasis on historical explanations or interpretations beyond the facts represents the main current of historiography, as Jenkins and Munslow mention, and our student teachers have undoubtedly had occasion to steep themselves in it during their university education. However, constructionism also underscores two essential issues that almost all our pre-service teachers seem to have overlooked in their curricular proposals. Firstly, none of these “constructed” explanations is considered “absolute”; the aim is to discover the meaning of the facts and construct interpretations with a certain level of truth, although the barriers to doing this are critically recognized. Secondly, and consequently, this category emphasizes historians’ efforts to be as objective as possible, surgically separating themselves from the history they attempt to recount; a critical warning about the method and evidence is the guarantee of this level of truth given to good accounts and historical explanations.

That critical fundamental component of constructionism completely disappears in almost all the texts we analyzed, which pre-service teachers talk in absolute terms about the history that must be taught. As historians, and when answering a direct question, they may have replied in a more genuinely “constructionist” manner, but when they focus their attention on the school curriculum, that view of history completely vanishes, although it is not reduced to “reconstructionism.” It is anchored in something that we could call “naive constructionism”: there is a true history that has to be taught and which indifferently includes facts and interpretations, with no epistemological reflection or critical stance of any kind. Only on a few occasions (5.5%) do pre-service teachers mention something about their students briefly examining the process professional historians follow to construct history and, when they do this, it is as added knowledge, a type of venture into historiography on the fringes of the history (seen as absolute) that students must learn.

Only one of the cases can be categorized as deconstructionist, the last of the positions in the model by Jenkins and Munslow (2004), which states that “there is no original or given meaning that history can discover. The fact that something happened does not mean that we know or can adequately describe what it means.” This epistemic position necessarily involves recognition that every meaning and interpretation stems from a certain perspective (interests, conceptions, beliefs, experiences, and so on) and not from the facts. That means placing emphasis in the analysis on the diversity of histories on the same past and the perspectives used to construct those histories. This single case among the n = 72 pre-service teachers analyzed actually plans to introduce students to the diversity of perspectives on the subject, although no deconstruction of these perspectives is proposed.

If we take as a reference the general epistemic models of Kuhn (1991) and Baxter-Magolda (2002), the result is clearer: the vast majority is in an absolutist epistemic position, to use the term both researchers mention for the first stage of their models. Baxter-Magolda perfectly describes the epistemic and curricular position we observed in most of our pre-service teachers:

…absolute knowing, characterized by the assumption that knowledge is certain, and people designated as authorities know the truth. Based on these epistemic assumptions, absolute knowers believed that: (a) teachers were responsible for communicating knowledge effectively and making sure students understood it (b), students were responsible for obtaining knowledge from teachers (c), peers could contribute to learning by sharing materials and explaining material to each other, and (d) evaluation was a means to show the teacher that students had acquired knowledge (Baxter-Magolda, 2002, p. 93).

However, this description of our pre-service teachers as absolutist is quite imprecise, even though it is highly revealing.

These results led us to conclude that we had to think of a specific epistemic model that could provide a more conclusive analysis. The lack of fit of the historical models used in this first phase of the analysis may lie in the samples giving rise to these models: VanSledright and Maggioni’s (2016) was produced on the basis of the analysis of secondary students’ responses, and Jenkins and Munslow’s (2004) is a theoretical model born of the analysis of the work by some of the best professional historians. Neither fitted our sample, mostly comprised of recent history graduates.

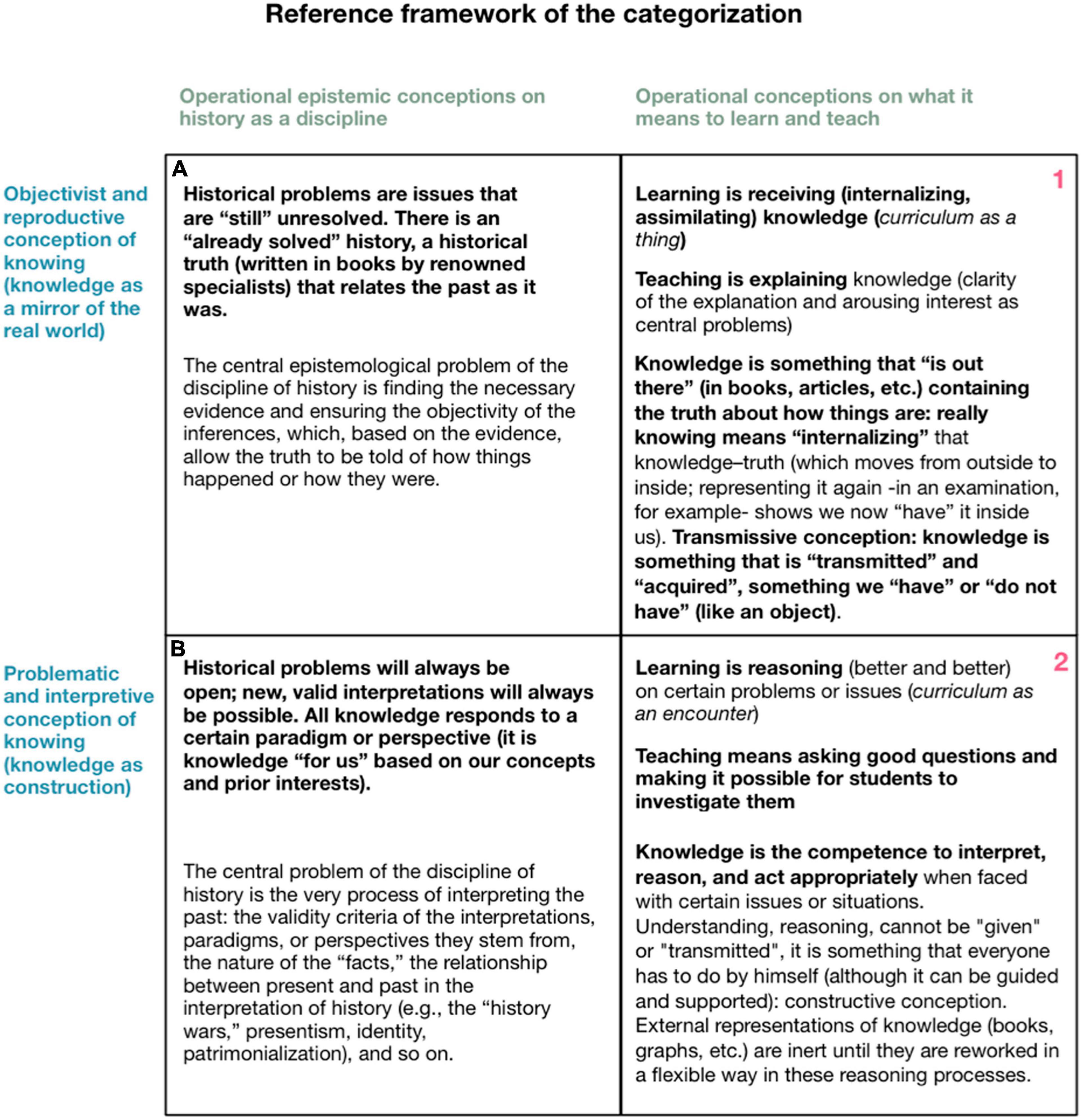

As the results of the first phase were quite inconclusive, a second round of analysis was necessary to find key aspects (emerging categorization) that discriminated and characterized the various positions. The result of this second attempt was the definition of a new conceptual framework for the categorization (Figure 2) based on two essential ideas.

Figure 2. Cross-reference framework of epistemic conceptions of history (A: “history as the past” and B: “history as an interpretation”) and conceptions of teaching and learning (1: “teaching as transmission of contents and learning as reproduction” and 2: “teaching as facilitating conceptual change and learning as understanding”).

-The first is the need to combine epistemic and educational conceptions in the analysis. We observed that our pre-service teachers’ curricular reflections and decisions could not be identified and characterized using only one of the two areas and, therefore, both types of beliefs had to be integrated for that purpose.

- The second idea stems from seeking a more precise criterion for the categorization. The most comprehensive approach to the texts made us realize there was a major dividing line between the sample in both the epistemic and educational aspects: whether (or not) the basic premise for interpreting and teaching history was problematic.

Taking an epistemologically problematic starting premise fully influenced the way a small group of our pre-service teachers talked about the teaching of the First World War and set them completely apart from the others. This division largely corresponds to the dual model proposed by Yilmaz (2008): “(a) history as the past and (b) history as an interpretation of the past” (p. 165). In parallel, opting for a curriculum focused on historical problems that students have to investigate also divided the curricular thinking between (1) teaching seen as transmitting contents compared with (2) teaching that facilitates students’ conceptual change (Kember, 1997; Trigwell and Prosser, 2004), and (1) learning as reproduction (surface-level learning) compared with (2) learning as understanding and competence (deep-level learning) (Marton and Säljö, 1976a,b; Entwistle and Ramsden, 1983; Marton et al., 2005). The result is a contingency table—a type of categorization matrix—with four boxes (Figure 2) in which epistemic and educational aspects are divided equally into an objectivist and reproductive conception and an interpretive and problematic conception. This integrated view of epistemic conceptions and conceptions of teaching and learning on the basis of a single criterion is possibly the fundamental decision in this study and the key to its relevance.

Starting (or not) with a problematic conception indicates a twofold parallel threshold—epistemological and educational—that we can summarize three ideas.

(1) Problematization: The basic premise of history (as a discipline and as a curriculum) is determining a historical problem. Compared with a “descriptive” position (history as a supposed neutral description of the past), an interpretive position starts with the idea that the basic premise of history is not the past but a certain question about that past, asked from a particular perspective. That is a historian’s first strategic decision. Consequently, the basic premise of the curriculum must be determining the historical problem that will be the most appropriate and valuable for students to investigate. When the epistemic and curricular aspects converge in this way, a crucial threshold has been crossed in history instruction.

(2) Perspective: Historical problems are always open. Compared with a closed and complete idea of knowledge, this is a dynamic and open idea in which new viewpoints are always possible and multiple perspectives evolving over time constantly intertwine. The deconstruction of perspectives (for example, interests, questions, conceptions, and emotions) giving rise to the diversity of historical interpretations, as well as the exploration of own interpretations, are consubstantial with this curricular and epistemic conception. The idea of “perspective” is thus configured as a threshold concept that has to be crossed to be positioned in this interpretive conception of history (Paricio, 2021).

(3) Inquiry: Inquiry is the central way of learning history, as it is of the historian’s work. This is not simply a methodological choice, but a true conception of what it means to teach/learn history and a “curricular principle” (Bihrer et al., 2019). Inquiry as a learning process is the inevitable consequence of historical problems as a curricular focus. As opposed to a transmissive–reproductive conception (learning as receiving and internalizing knowledge that is out there), a constructive conception understands learning as being able to reason (increasingly better) about certain types of problems and questions. In other words, rather than the curriculum as a thing (to be internalized), we have the curriculum as an encounter (with certain problems and certain methods to deal with them), to develop understanding and competence (Den Heyer, 2014). Inquiry is not only the means, but the end itself: one learns to reason by reasoning (with appropriate scaffolding) when confronted with a particular type of problem.

By placing epistemic and educational conceptions in parallel, we focus on how the discipline is transmitted in the classroom. An absolutist conception of history, understood as a single and supposedly true account, can result in nothing but a reproduction of that account in the classroom by teachers and students. Similarly, implementing an interpretive and problematic curriculum is the logical consequence of a conception of history as an inquiry into and questioning of the past, using agreed methods and diverse perspectives. However, the analysis of our pre-service teachers’ reflections shows that this correspondence is far from automatic, and that reality is substantially more complex. Some of our pre-service teachers have a perfect understanding of that interpretive nature of history, but their decisions and reflections on the curriculum correspond to a “reproductive” position. Although the epistemic conceptions seem to establish a framework—limits on possible thinking concerning the curriculum—they do not determine it at all. In fact, it seems their conception of the nature of history changes depending on whether they talk of history as a discipline or the history curriculum in secondary education. The first categorization tests confirmed that this complexity can be addressed more precisely using the new reference framework, analyzing epistemic and educational conceptions in parallel.

Based on the boxes in the new reference framework, the analysis enabled us to identify the following categories in how our pre-service teachers approach the history curriculum.

A + 1. “Chronicle”: 7/72 (9.5%)

Students must learn (= reproduce) the (objective) facts of history (interpretations are doubtful or controversial). Only 10% of pre-service teachers identify past and history (history as a true account of the past) and view teaching it as a description of the essential facts that students must learn and reproduce. The curriculum is limited to the facts, either simply due to following the textbook’s traditional direction, or due to a conscious attempt to avoid entering into interpretations that can become polemical.

A + 1. “Interpretation”: 60/72 (83.5%)

Students must learn (= reproduce) a certain interpretation of the past (understood as the history that reveals the true meaning of the facts). Out of the 72 pre-service teachers, 60 think they should present their students with a single version of the past, identified as a true history. However, they reject only “giving” the facts and they opt to offer global interpretations (causal linking, change processes, and so on) in which the facts gain some meaning and relevance. Out of these 60, 13 show signs of having an interpretive conception of history as a discipline, but they abandon that conception when thinking about the secondary curriculum.

To prevent the subject from becoming a mere list of facts, this group of pre-service teachers tries to structure them into major historical processes or connect them with the present in some way. Most (40) opt to work on the causal concatenations as way to link and give meaning to the facts.

“The most important aspect is that they understand long historical processes. In this respect, I would give priority to understanding the causes and consequences”; “above all, I would emphasize causes and consequences that would help them better understand the progression of events in the twentieth century.”

Many (28) also insist on linking historical processes or events with the present.

“Teaching the structures and contexts that appear and evolve throughout history, giving students a critical view or perspective of the past that they can use to analyze and intervene in their present reality.”

Lastly, there is also an important group (31) seeking to make sense of the facts by linking them with the democratic values of the present.

“[The First World War enables us to debate] why interaction and cooperation between countries is necessary. make [them] think about the role of nationalisms.”

A + 2. “Null”: 0/72 (0%)

It does not seem possible to devise a problematic curriculum (2) using an absolutist epistemic conception (A); therefore, the presence of zero people in A + 2 is not at all surprising.

B + 1. “Historiographical Process”: 4/72 (5.5%)

Students must learn (= reproduce) a certain version or account of the past, but they must also know the process of interpretation that has made it possible to produce that history based on certain sources. This group talks about exercising critical thinking for any interpretation of the past and how the sources are analyzed and interpreted to construct histories, and they want their students to participate in these ideas. Their conception of history as a discipline falls within category “B,” but they do not ask their students to do any active inquiry work using (and based on) these sources; neither do they propose a critical deconstruction process of the possible historical discourses. At the same time as they teach a certain interpretation of the past, they want to teach their students how a historian works.

“The purpose of history taught in secondary schools should be to show students how a historian’s work unfolds”; “I think it is very important for students to learn how historians interpret primary sources historically to construct historical accounts and what we know as history”; “working with sources can be very interesting so they discover that history is not something historians invent, but rather that they have their “laboratory” and do their “experiments” with these small fragments of the past that are documents. We also have to explain that sources are not the absolute truth and that they can contradict each other…”

In other cases, this also includes the awareness that diverse interpretations are always possible but without ever realizing that their students can become involved in an active work of inquiry.

“My main challenge would be to show my students that these historical events do not necessarily have to be as they are narrated in the textbook. In other words, I would try to convey to my students that a critical stance is required to study history. Consequently, the greatest difficulty would be changing their pre-established idea that history is simply a narration of past events. To do that, I would try to demonstrate, for example, using various sources, that the same event can be recounted and interpreted in different ways with differing objectives.”

B + 1. “State of the Historiographical Art”: 1/72 (1.5%)

Students must learn (= reproduce) the various competing historical interpretations of the same historical event or process. In this category we have included a single student whose curricular focus is on providing a range of interpretations of the First World War: “My biggest challenge is preventing the students from limiting themselves to only understanding the conflict from a single viewpoint. It is important to generate this questioning of the truth, trying to approach a phenomenon or event from different viewpoints or angles.” However, this person always talks about the students knowing different versions, never about investigating them to deconstruct the perspectives on which they are constructed.

B + 2. “Historical Reasoning”

Students must investigate certain historical problems by analyzing sources, constructing their own hypotheses, debating their interpretation proposals, and so on.

B + 2. “Critical Thinking”

Students must critically analyze a certain interpretation of the past, reinterpreting their sources and/or revising the process that has enabled it to be produced and validated.

B + 2. “Multiperspective”

Students must investigate the various histories and deconstruct them by analyzing the different perspectives that gave rise to them.

The last three categories do not appear in the analysis of our pre-service teachers’ curricular decisions and reflections. They stem from proposals and experiences often published in the literature and which would correspond with the B + 2 combination. They have been highlighted because they are objectives we want to achieve with our teacher education program.

In our opinion, three essential ideas can be gleaned from the results of the analysis phases.

1. History graduates do not necessarily have a sufficiently advanced or mature epistemic conception of their own discipline.

We have observed that the predominant conceptions are quite naive and associate history with a true account corresponding to the reality of the past. This does not necessarily imply that the same results would be obtained using instruments such as the Beliefs about Learning and Teaching History Questionnaire, BLTHQ (Maggioni et al., 2009), which asks direct questions about these beliefs. Our method investigates operational conceptions, in other words, those actually used for reasoning about a certain type of task or situation. Our results show that when pre-service teachers have to plan a secondary-school history subject and are asked to determine their curricular goals, the approach to key issues, or the use they will make of sources, an identification between past and history prevails in the majority of cases.

In most cases (all the pre-service teachers categorized as “A,” 67/72), the decisions and reflections respond to this conception of a single and objective history. They do not question the interpretation of the First World War given in the textbook in any way. In fact, they do not seem to perceive that there is any interpretation at all, but simply an account of “the facts,” that are deemed completely necessary to know (although the information on military operations is less detailed). The assurance some feel that the history subject they are going to teach represents the reality of events and a real shield against fake news is striking:

“These days there is an abundance of fake news and here they have the best tool to protect themselves against that”; “a citizen that does not know their history is far easier to manipulate and will not have the tools to discern falsehoods from real historical facts”; “[in this subject] they will have the tools to discern falsehoods from historical facts.”

For the vast majority of the pre-service teachers, the textbook seems to be a simple description of the past and they only propose to complete this information or contextualize it in more general frameworks in order to make it more understandable.

Primary sources are almost always understood as a kind of direct window onto the past that is “necessary to supplement teachers’ explanations in class” and that confirms the history they relate.

“They are a way of showing what the teacher is saying”; “I would use them to explain. in a verifying way”; “I would use them at the end, as reflection, with the purpose of making students see that imperialism was just as it was explained”; “I could use it to revise content and conclude”; “it is the best way for students to see the issues raised throughout the classes”; “they help to consolidate the theoretical information”; “they complement the theoretical classes”; “they can help to considerably improve learning”; “essential complementary materials so that students can consolidate the theory and the teacher’s explanations.”

This way of understanding sources and their role in history instruction is very revealing of the conception of the discipline that pre-service teachers actually activate to think about the curriculum, beyond historiography courses we know they have received.

It is important to clarify that the naïve realism of these pre-service teachers has little to do with the philosophical debate on history between objectivism and relativism. A critical objectivist stance asserts that an objective history can be constructed with a method ensuring appropriate distance between the historian and their history (Newall, 2009), but in this case the textbook version is assumed to be true simply due to authority or tradition. Our pre-service teachers seem to have completely forgotten the old maxim that “any history is someone’s history” (Levstik, 1997, p. 48).

In other cases (categorized as B- > A, 18%), pre-service teachers way of talking about sources or possible interpretations clearly reveals a more mature understanding of history as a discipline. This understanding, however, seems to fade away when they start to outline their curricular proposal. The course of reasoning of some of them suggests that this is not so much an intentional curricular decision, but rather an automatic change of register, the unintentional emergence of a more naïve epistemic conception of history, specifically associated with school history. However, there are also those who explicitly argue for this decoupling of school history from academic history.

“Although it is true that I think one of a historian’s tasks is to question all inherited knowledge, perhaps students doubting everything, while positive, could prove counterproductive as it would create a great deal of confusion; therefore, we must prioritize them obtaining a minimum level of safe and stable content so that later, in higher academic grades, they can explore and shape their rational and reasoned stance in this regard.”

Only in students categorized as “B” (7%) can we see how an advanced conception of sources or a certain critical analysis of historical interpretations is incorporated into the curriculum:

“They could contextualize each of the sources, explaining the moment, the figures, and the intentions of each of the authors. in other words, learn what a primary source is and different ways of processing it”; “more attention should be paid to studying the sources, as it would help students approach historical investigation and learn more about history as a discipline”; “my main challenge would be to show my pupils that these historical events do not necessarily have to be as they are narrated in the textbook”; “[where the textbook] fails is not in that approach alone, but in the lack of other equally valid interpretations.”

The epistemic shortcomings observed in the conceptions through which the vast majority of future history teachers reason about the curriculum are extraordinarily relevant for the design of teacher education. An interpretive curriculum cannot be put into practice, or even truly understood, if it is based on naive realism associating history with a description of what actually happened. Our proposals simply make no sense to them. As we have seen, the sources have a mere confirmatory or revision value of the history that has already been explained. They invariably consider that the inquiry activities based on the sources we have been proposing for years are mere “active” methods that will help their students “learn” the history. Often, to prevent the monotony of the teacher’s single discourse, they propose “debates” to end units, but these are not spaces for inquiry and reasoning about historical problems, but mere breaks for students to give their opinion about “what happened” (now that they already know).

2. A Non-problematic and non-inquiry-based conception of the curriculum

We understand inquiry-based learning (IBL) as a type of activity in which students independently tackle (but with appropriate support) problems or issues in the discipline and produce explanations based on evidence thus learning to reason with concepts and methods that are characteristic of that discipline (Pasternack, 2019). The methods can be diverse, but the essential idea is always to develop the reasoning capacity through suitable problems. Previous studies have shown that a history curriculum understood as a mere supply of information that students must then reproduce is very well-established (Samuelsson, 2019; Boadu, 2020). Our pre-service teachers have undoubtedly experienced that tradition, and, despite their criticism, they do not seem to have broken away from it.

Faced with planning a didactic unit on the First World War, none of them consider which relevant historical issues related to the Great War their pupils could work on. The First World War does not seem to be a problematic issue to take to the classroom but rather a “syllabus” or a series of contents that students must learn. Their decision as teachers seems to be limited to deciding where to place more emphasis in their explanations (social, cultural, military, and so on).

It is significant that the main difficulty the teachers highlight, mentioned by 37% of them, is that there is not much time available for the large amount of “essential” information: “the main challenge is the time we have to teach the subject, and as it is a rather important area that we have a lot of information about, this fact is even more evident.” The way they talk about the time problem perfectly illustrates this majority “informative” conception of history instruction.

“Despite the teachers, the subject must be taught quite quickly. it must cover as much as possible, but always using coherent and comprehensible discourse and exposition”; “the chief challenge is the amount of important information I will not have time to mention in enough detail, or barely touch on, for example, the progress made by the working class or votes for women…”

Some pre-service teachers recognize that rather than supplying information, it would be interesting to perform other activities in class, but they doubt it will be possible to “make time for them.” For the vast majority, further information means more learning. This quantitative conception of learning, deep-seated in most, is an enormous barrier to implementing an interpretive curriculum. Year after year, our pre-service teachers have argued that there was no time to ask their students about historical problems, however interesting they might think such activities are. The sample in this study—graduates beginning their education program as pre-service history teachers—confirm that same idea: the majority feel they would not be fulfilling their obligation if they did not explain all the information in the textbook, as learning history is, above all, knowing these historical data about First World War; everything else is non-essential add-ons.

The study by Keiser et al. (2014) concludes that, in any subject, the necessary prerequisite for adopting an inquiry-based learning strategy is sharing the ideas and principles of epistemological constructivism. In the case of history, this means conceiving the curriculum on the basis of the distinction between past and history, and accepting the interpretive nature of the discipline (Voet and De Wever, 2016). On this premise, for all of our students categorized as “A,” the idea of an inquiry-based curriculum simply does not make sense (which our data confirm). This offers a first level of explanation to the original question of why our pre-service teachers find it so hard to understand it and put it into practice despite the education they have received. Undoubtedly, adequate knowledge of inquiry-based learning is a necessary condition (Yilmaz, 2008), but it does not suffice. It makes no sense to talk about a problematic and inquiry-based curriculum without an appropriate epistemic conception.

However, none of the five pre-service teachers categorized as “B” plan for their pupils to tackle any problems or issues, even though they talk about addressing a variety of interpretations or working on sources “to approach historical investigation” in their classrooms. Knowledge and appropriate epistemic beliefs seem insufficient as well. And it is at this point that we see, in line with the work of Voet and De Wever (2016, 2018), how tacit beliefs about what it means to learn and teach also come into play, acting as filters that shape teachers’ decision-making. Focusing the curriculum on inquiry into historical problems requires embracing the idea that knowledge is not something external that is “internalized” (and reproduced later), but a skill that is developed. Really knowing something (understanding it in depth) means knowing how to think about the subject with some autonomy, which cannot be achieved without addressing issues and reasoning. The fact none of our pre-service teachers even approaches this conception of learning is a clear example of how difficult it is. An extremely long tradition and experience of explanation followed by reproduction have resulted in deeply rooted implicit conceptions on what it means to teach and learn, to the extent that even pre-service teachers with clear ideas on the constructed nature of history find it hard to conceive an inquiry-based curriculum on historical problems.

This is an important conclusion since it confirms those Barton and Levstik (2010) arrived at on historiographical epistemological education not sufficing to change teachers’ curricular approach. It also aligns with the conclusions reached by McDiarmid and Vinten-Johansen (2000) and Mayer (2003) that epistemic beliefs and teaching and learning beliefs need to be addressed in an integrated way in the education of pre-service history teachers.

3. Rejection of an encyclopedic history as a mere fragmentary accumulation of facts

If, in the main, pre-service teachers identify past and history in their curricular decisions and view history instruction as essentially “reproductive” and not inquiry-based, does this mean they consider their fundamental curricular objective to be “covering” the textbook, as Barton and Levstik point out? We observed an explicit generalized rejection (60 out of the 67 pre-service teachers categorized as A + 1) of the traditional encyclopedic conception of textbooks and the way they reduce history to an accumulation of events and figures, often presented in such an artificial and fragmentary manner that no comprehension is possible (Loewen, 1996). Most of the pre-service teachers emphatically state they want their students to “understand” the history they explain to them. As mentioned above, they plan to do this by integrating textbook details into broader narratives or explanations linking the events together to ensure they make some kind of sense. Therefore, although they do not completely reject the textbook, they somehow consign it to having a secondary role after their explanations in class. By distancing themselves from this supposedly neutral descriptive encyclopedia—their history manuals—they instead opt for major history books in which historians aim for the past to gain a certain meaning, and, probably, also a value in the present. In short, it is a particular way of making the discipline accessible to students.

However, their reflections let us glimpse a contradiction that will most likely ruin their intentions in practice: their desire to offer these grand narratives and simultaneously meet the obligation they feel to cover almost all the textbook’s content does not seem viable in the available time. That is why there is a generalized insistence on the problem of time. When they discover that a comprehensible narrative often requires mentioning details, testimonies, or specific situations embodying general interpretation, as it does in history books, and they face the dilemma of opting between the narrative or the synthetic data in the textbook, what will their choice be? Will they actually manage to rid themselves of that feeling of obligation for the textbook content and choose the narrative?

In any case, this result qualifies the findings of Barton and Levstik (2010) which are the basis for the central question of our study: “Coverage of textbook or curriculum content. that is what many people think history teaching is all about.” Most of our pre-service teachers do not think in terms of “covering” the textbook, at least not in their initial intentions. Their experience as history students themselves warns them against that encyclopedic vision of history that the manuals encompass. This leads to the following question: Does that distancing from textbooks and turning to history books interpreting the past also mean they embrace interpretive history in the classroom? Might it represent a bridge facilitating understanding of what that interpretive and inquiry-based history curriculum means? Our hypothesis, which will need further research, is that it does not necessarily. The reproductive conception of learning is deep-seated and finding a solution that can improve on encyclopedic history without challenging those fundamental beliefs on learning can actually help consolidate them.

This study is based on observing the difficulties pre-service history teachers face in understanding and accepting an interpretive history curriculum. Its aim is to better outline the nature and origin of these difficulties to tailor their education program better. The starting hypothesis is that their epistemic beliefs on history as a discipline and their beliefs on what learning and teaching means somehow block that comprehension. These beliefs were analyzed at the start of their education as part of a more overarching project whose purpose is a longitudinal monitoring of these pre-service teachers’ beliefs throughout their entire year of training. Furthermore, this project is meant to be continued over the coming years with the aim of observing potential changes in the history teaching conceptions of pre-service teachers.

The use in the analysis of existing models of epistemic progression and of beliefs on the nature of learning and education has not sufficiently clarified the system of beliefs pre-service history teachers employ to make their curricular and teaching decisions concerning a practical exercise related to teaching the First World War. For that reason, starting with an exploratory analysis of their reflections, we propose an ad hoc model interrelating epistemic and educational beliefs based on the same discrimination factor or criterion, which we could define as the presence of a problematized conception of history as a discipline and as a school curriculum.

Categorization using this integrated model has enabled us to observe the complexity of relationships between epistemic and educational beliefs; we can therefore rule out the idea that sophisticated ideas about the nature of history directly lead to acceptance of an interpretive curriculum in which students have an inquiry-based approach to historical problems. This conclusion is consistent with observations published on the results of including epistemological education in the training programs of history teachers.

We can conclude from this joint observation of epistemic and learning-teaching beliefs that there is indeed a twofold threshold that prevents pre-service teachers from understanding and implementing an interpretive history curriculum. Not only must they overcome implicit naive realism (history as a simple description of the past), which abounds when they design the secondary-school curriculum, but they must also begin to think about learning (and, consequently, teaching) using a very different conception to that kind of “absorption” of knowledge inferred in their reflections. Both thresholds are critical and form real glass walls that prevent thinking about a problematic history in the classroom.

Observing this twofold threshold, which we could term specular–reproductive, broaches the need to further explore the links between both belief dimensions by studying how they mutually integrate into a single system and mutually condition and support each other. We believe it is essential to integrate both aspects into the education of pre-service teachers. This is not just because both epistemic and educational conceptions are appropriate, but because they mutually illumine each other where they intersect. In the end, practicing interpretive history in the classroom is nothing more than actually transmitting the discipline in the curriculum, in other words, following the old proposal put forward by Bruner (1966), integrating epistemology and education.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

JP and SG-C: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and visualization. JP, SG-C, and AR-N: investigation, writing—review and editing. SG-C and AR-N: data curation. JP: writing—original draft preparation and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This article was made possible by the research group ARGOS, the didactics of social sciences, which was supported by the Government of Aragon, FEDER (EU)—European Regional Development Fund—(S50_20R) 2020–2022 and the University Institute of Research in Environmental Sciences of Aragon (IUCA) of the University of Zaragoza, and the Project PID2020-115288RB-I00 “Digital competences, learning processes and cultural heritage awareness: Quality education for sustainable cities and communities” MINECO/AEI-FEDER.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Barton, K. C., and Levstik, L. S. (2010). “Why don’t more history teachers engage students in interpretation?,” in Social Studies Today. Research and Practice, ed. W. C. Parker (Oxon: Routledge), 35–42.

Baxter-Magolda, M. B. (2002). “Epistemological reflection: the evolution of epistemological assumptions from Age 18 to 30,” in Personal Epistemology: the Psychology of Beliefs about Knowledge and Knowing, eds K. B. Pintrich and P. R. Hofer (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 89–102.

Berg, C. W., and Christou, T. M. (eds). (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of History and Social Studies Education. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bihrer, A., Bruhn, S., and Fritz, F. (2019). “Inquiry-based learning in history,” in Inquiry-Based Learning – Undergraduate Research, ed. H. A. Mieg (Cham: Springer), 291–299. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14223-0_27

Boadu, G. (2020). Hard” facts or “soft” opinion? History teachers’ reasoning about historical objectivity. J. Int. Soc. Stud. 10, 177–202.

Colomer, J. C., Sáiz, J., and Morales, A. J. (2021). “History and geographical thinking skills: between disciplinary knowledge and knowledge for teaching in teacher education,” in Handbook of Research on Teacher Education in History and Geography, eds C. J. Gómez-Carrasco, P. Miralles-Martínez, and R. López-Facal (Berlin: Peter Lang), 159–176.

Cornbleth, C. (2010). “What constrains meaningful social studies teaching?,” in Social Studies Today. Research and Practice, ed. W. C. Parker (New York, NY: Routledge), 215–223.

Den Heyer, K. (2014). “Engaging teacher education through rewriting that history we have already learned,” in Becoming a History Teacher: Sustaining Practices in Historical Thinking and Knowing, eds R. Sandwell and A. von Heyking (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 175–197. doi: 10.3138/9781442619241-012

Dunn, R. E. (2010). “The two world histories,” in Social Studies Today. Research and Practice, ed. W. C. Parker (New York, NY: Routledge), 183–195.

Fordham, M. (2012). Disciplinary history and the situation of history teachers. Educ. Sci. 2, 242–253. doi: 10.3390/educsci2040242

Gómez-Carrasco, C. J., Rodríguez-Medina, J., Chaparro-Sainz, Á, and Monteagudo-Fernández, J. (2022). Teaching approaches and profile analysis: an exploratory study with trainee history teachers. SAGE Open 11, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/21582440211059174

Jenkins, L., and Munslow, A. (2004). The Nature of History Reader. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203002186

Keiser, M. M., Burrows, B. D., and Randall, B. (2014). “Growing teachers for a new age: nurturing constructivist, inquiry-based teaching,” in Inquiry-Based Learning for the Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences: A Conceptual and Practical Resource for Educators, eds P. Blessinger and J. M. Carfora (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 303–324. doi: 10.1108/s2055-364120140000002028

Kember, D. (1997). A reconceptualisation of the research into the university academics’ conceptions of teaching. Learn. Instruct. 7, 255–275. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00028-X

Kuhn, D., Cheney, R., and Weinstock, M. (2000). The development of epistemological understanding. Cogn. Dev. 15, 309–328. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2014(00)00030-7

Kuhn, D., and Weinstock, M. (2002). “What is epistemological thinking and why does it matter?,” in Personal Epistemology: The Psychology of Beliefs about Knowledge and Knowing, eds B. K. Hofer and P. R. Pintrich (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 121–144.

Lee, P. J. (2005). “Putting principles into practice: understanding history,” in How Students Learn: History in the Classroom, eds M. S. Donovan and J. D. Bransford (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press), 31–77.

Levstik, L. S. (1997). Any history is someone’s history”. listening to multiple voices from the past. Soc. Educ. 61, 48–51.

Loewen, J. W. (1996). Lies My Teacher Told Me. Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Maggioni, L., VanSledright, B., and Alexander, P. A. (2009). Walking on the borders: a measure of epistemic cognition in history. J. Exp. Educ. 77, 187–214. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.77.3.187-214

Marton, F. (1986). Phenomenography—a research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. J. Thought 21, 28–49.

Marton, F., Hounsell, D., and Entwistle, N. (eds). (2005). The Experience of Learning: Implications for Teaching and Studying in Higher Education, 3rd Edn. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Marton, F., and Säljö, R. (1976a). On qualitative differences in learning - I. Outcome and Process. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 46, 4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1976.tb02980.x

Marton, F., and Säljö, R. (1976b). On qualitative differences in learning - II. Outcome as a function of the learner’s conception of the task. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 46, 115–127. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1976.tb02304.x

Mayer, R. H. (2003). Learning to think historically: the impact of a philosophy and methods of history course on three preservice teachers. Paper Presented at the 84th Anual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

Mayer, R. H. (2006). Learning to teach young people how to think historically: a case study of one student teacher’s experience. Soc. Stud. 97, 69–76. doi: 10.3200/TSSS.97.2.69-76

McDiarmid, G. W., and Vinten-Johansen, P. (2000). “A catwalk across the great divide: redesigning the history teaching methods course,” in Knowing, Teaching, and Learning History, eds P. N. Stearns, P. Seixas, and S. Wineburg (New York, NY: New York University Press), 156–177.

Nadelson, L. S., Heddy, B. C., Jones, S., Taasoobshirazi, G., and Johnson, M. (2018). Conceptual change in science teaching and learning: introducing the dynamic model of conceptual change. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 7, 151–195. doi: 10.17583/ijep.2018.3349

Newall, P. (2009). “Historiographic objectivity,” in A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography, ed. A. Tucker (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell), 172–180. doi: 10.1002/9781444304916.ch14

Norton, L., Richardson, J. T. E., Hartley, J., Newstead, S., and Mayes, J. (2005). Teachers beliefs and intentions concerning teaching in higher education. High. Educ. 50, 537–571. doi: 10.1007/s10734-004-6363-z

Ohlsson, S. (2009). Resubsumption: a possible mechanism for conceptual change and belief revision. Educ. Psychol. 44, 20–40. doi: 10.1080/00461520802616267

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 307–332. doi: 10.3102/00346543062003307

Paricio, J. (2021). Perspective as a threshold concept for learning history. Hist. Educ. Res. J. 18, 109–125. doi: 10.14324/HERJ.18.1.07

Paricio, J., and García-Ceballos, S. (in press). “Reproducir o razonar: >qué significa aprender historia para el profesorado del futuro?,” in International Handbook of innovation and Assessment of the Quality of Higher Education and Research, (Dykinson).

Parra-Monserrat, D., Fuertes-Muñoz, C., Asensi-Silvestre, E., and Colomer-Rubio, J. C. (2021). The impact of content knowledge on the adoption of a critical curriculum model by history teachers-in-training. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 1–11. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00738-5

Pasternack, P. (2019). “Concepts and case studies: the state of higher education research on inquiry based learning,” in Inquiry-Based Learning – Undergraduate Research. The German Multidisciplinary Experience, ed. H. A. Mieg (Cham: Springer), 19–26. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304489.65028.75

Postareff, L., and Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2008). Variation in teachers’ descriptions of teaching: broadening the understanding of teaching in higher education. Learn. Instruct. 18, 109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.01.008

Richardson, V. (1996). “The role of attitude and beliefs in learning to teach,” in Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, 2nd Edn, eds J. Sikula, T. Buttery, and E. Guyton (New York, NY: Macmillian), 102–119.

Samuelsson, J. (2019). History as performance: pupil perspectives on history in the age of ‘pressure to perform’. Education 3-13 47, 333–347. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2018.1446996

Seixas, P. (1998). Student teachers thinking historically. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 26, 310–341. doi: 10.1080/00933104.1998.10505854

Seixas, P. (1999). Beyond ‘content’ and ‘pedagogy’: in search of a way to talk about history education. J. Curric. Stud. 31, 317–337. doi: 10.1080/002202799183151

Shtulman, A. (2009). Rethinking the role of resubsumption in conceptual change. Educ. Psychol. 44, 41–47. doi: 10.1080/00461520802616275

Smith, I. I. I. J. P., Disessa, A. A., and Roschelle, J. (1994). Misconceptions reconceived: a constructivist analysis of knowledge in transition. J. Learn. Sci. 3, 115–163. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls0302_1

Trigwell, K., and Prosser, M. (2004). Development and use of the approaches to teaching inventory. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 16, 409–424. doi: 10.1007/s10648-004-0007-9

Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., and Ginns, P. (2005). Phenomenographic pedagogy and a revised approaches to teaching inventory. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 24, 349–360. doi: 10.1080/07294360500284730

Van Hover, S. D., and Yeager, E. A. (2004). Challenges facing beginning history teachers: an exploratory study. Int. J. Soc. Educ. 19, 8–21.

VanSledright, B., and Maggioni, L. (2016). “Preparing teachers to teach historical thinking? an interplay between professional development programs and school-systems’ cultures,” in Handbook of Research on Professional Development for Quality Teaching and Learning, eds T. Petty, A. Good, and S. Putman (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 252–280. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-0204-3.ch012

VanSledright, B., and Reddy, K. (2014). Changing epistemic beliefs? An exploratory study of cognition among prospective history teachers. Rev. Tempo Argumento 6, 28–68. doi: 10.5965/2175180306112014028

Voet, M., and De Wever, B. (2016). History teachers’ conceptions of inquiry-based learning, beliefs about the nature of history, and their relation to the classroom context. Teach. Teach. Educ. 55, 57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.12.008

Voet, M., and Wever, B. D. (2018). Teachers’ adoption of inquiry-based learning activities: the importance of beliefs about education, the self, and the context. J. Teach. Educ. 70, 423–440. doi: 10.1177/0022487117751399

Wansink, B. G. J. (2017). Between Fact and Interpretation. Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in Interpretational History Teaching. Dissertation. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Yeager, E., and Davis, O. L. Jr. (1996). Classroom teachers’ thinking about historical texts: an exploratory study. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 24, 146–166. doi: 10.1080/00933104.1996.10505774

Keywords: epistemic beliefs, historical thinking, pre-service teachers, teaching approaches, history instruction

Citation: Paricio J, García-Ceballos S and Rubio-Navarro A (2022) Epistemic Beliefs and Pre-service Teachers’ Conceptions of History Instruction. Front. Educ. 7:865222. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.865222

Received: 29 January 2022; Accepted: 18 March 2022;

Published: 13 April 2022.

Edited by:

Álvaro Chaparro-Sainz, University of Almería, SpainReviewed by:

Ursula Luna, University of the Basque Country, SpainCopyright © 2022 Paricio, García-Ceballos and Rubio-Navarro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Silvia García-Ceballos, c2djZWJhbGxvc0B1bml6YXIuZXM=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.